Abstract

Objective:

The University of California Los Angeles Scleroderma Clinical Trials Consortium gastrointestinal tract 2.0 (UCLA GIT 2.0) questionnaire is a self-reported tool measuring gastrointestinal (GI) quality of life in systemic sclerosis (SSc) patients. Scarce data are available on the correlation between patient reported GI symptoms and motility dysfunction as assessed by esophageal transit scintigraphy.

Methods:

We evaluated the UCLA GIT 2.0 reflux scale in SSc patients admitted to our clinic and undergoing esophageal transit scintigraphy, and correlated their findings.

Results:

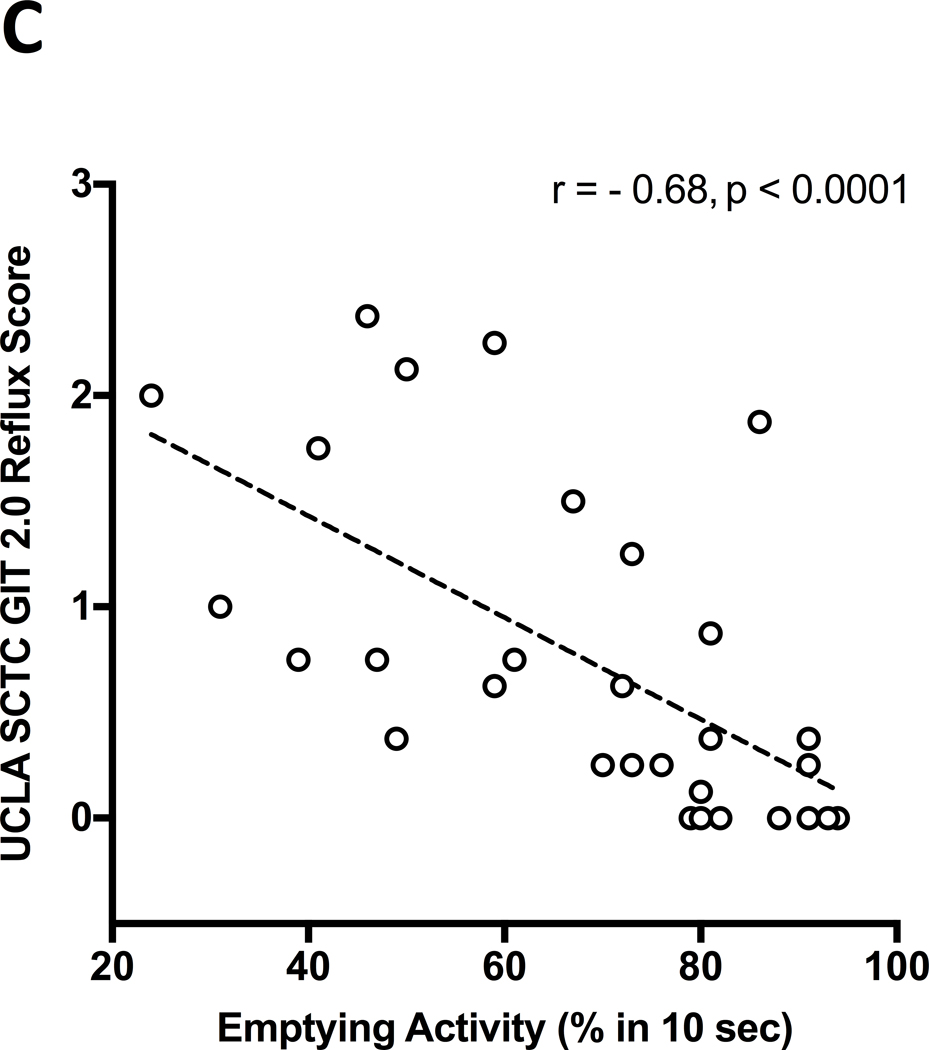

Thirty-one SSc patients undergoing esophageal transit scintigraphy were included. Twenty-seven were female, 8 with diffuse cutaneous subset; 26/31 (84%) patients had a delayed transit and an abnormal esophageal emptying activity. Mean (SD) emptying activity percentage was higher in patients with none-to-mild GIT 2.0 reflux score [81.1 (11.5)] than in those with the moderate [55.7 (17.8), p = 0.003] and severe-to-very-severe scores [55.8 (19.7), p = 0.002]. The 26 (84%) SSc patients with delayed esophageal transit had a higher GIT 2.0 reflux score (p=0.04). Percentage of esophageal emptying activity negatively correlated with the GIT 2.0 reflux score (r = − 0.68, p < 0.0001) while it did not correlate with the other scales and the total GIT 2.0 score.

Conclusion:

SSc patients with impaired esophageal scintigraphy findings have a higher GIT 2.0 reflux score. The UCLA SCTC GIT 2.0 is a complementary tool for objective measurement of esophageal involvement which can be easily administered in day-to-day clinical assessment.

Keywords: gastroesophageal reflux disease, gastrointestinal tract, outcome assessment, scleroderma, scintigraphy, systemic sclerosis

Introduction

Systemic Sclerosis (SSc) is a complex disease characterized by early microvascular abnormalities, immune dysregulation and chronic inflammation, and subsequent fibrosis of the skin and internal organs (1). The esophago-gastro-intestinal tract is the most frequently involved internal organ in SSc, affecting up to 90% of the patients. The esophagus is the most commonly affected tract (2). Esophageal dysfunction involves the lower two-thirds of the organ and is characterised by a hypotensive lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure and a weak or absent distal esophageal peristalsis with subsequent gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) (3).

Several standardised techniques may be used to assess the esophageal involvement in SSc including pH monitoring, manometry, barium swallow, upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy, esophageal transit scintigraphy (ETS). The latter is an old and reliable methodology (4), with the ability to assess the motor function of the esophagus and its emptying activity (EA) (3).

Although providing objective information on measuring reflux, esophageal motility or morphology, all the mentioned techniques are invasive or use radiation, thus they are not applicable for monitoring the esophageal involvement and symptoms at each follow-up visit. Therefore, patient-reported outcomes have been developed for guiding patient care for GERD management (5). They have the potential to be more practical and cost-effective outcome measures also for randomized, placebo-controlled clinical studies (5). Within this group, the University of California Los Angeles Scleroderma Clinical Trials Consortium gastrointestinal tract 2.0 (GIT-2.0) questionnaire is a self-reported tool, including a 7-multi-item scales measuring GI quality of life (6).

With regards to the reflux scale, GIT-2.0 has been shown to be sensitive to change following therapeutic intervention in a recent multicenter study (5). Association of GIT-2.0 reflux scale with objective tests such as manometry, barium swallow and upper GI endoscopy has been investigated in previous studies showing its complementary value as a tool for objective measurement of esophageal involvement (7,8) while no data are available with ETS.

Aim of this study was to evaluate patient reported GI symptoms by GIT-2.0 in SSc patients undergoing ETS and correlate their findings.

Materials and methods

Patients

Subjects admitted for the first time to the in-patient rheumatology clinic of San Carlo Hospital (Potenza, Italy) from 1st Sept 2017 to 31st December 2019 for suspected or confirmed diagnosis of SSc and undergoing ETS within the diagnostic work-up for the assessment of internal organ involvement, were offered to participate to this study. All patients fulfilled the 2013 ACR/EULAR classification criteria for SSc (9). The study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Basilicata (n. 705/2017). Informed consent was obtained from all patients. Clinical data were collected during admission and included a wide set of variables, as previously described (10).

Questionnaires

All participants were invited to fill the Italian version of GIT-2.0 (11) and Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) (12) with the five SSc-related visual analogue scales (VAS) (13).

The GIT-2.0 includes 34 items with 7 multi-item scales (reflux, distention/bloating, fecal soilage, diarrhea, social functioning, emotional well-being and constipation) (6). All scales are scored 0.00–3.00 except the diarrhea and constipation (0.00–2.00 and 0.00–2.50, respectively). The total GIT-2.0 score averages 6 of 7 scales (excluding constipation) and is scored from 0 (no GI problems) to 2.83 (most severe) (14). The GIT-2.0 was found to have acceptable validity in different observational studies (5,7,14–18).

The HAQ is a self-reported questionnaire, scored 0.00–3.00 (15), extended to form the scleroderma HAQ (SHAQ) that incorporates the pain VAS and five scleroderma-related 0–100 VAS (intestinal problems, breathing, Raynaud’s phenomenon, finger ulcers, and overall disease severity from the patients’ perspective) (13).

Esophageal transit scintigraphy

Patient undergoing ETS were requested to fast for at least 4 hours. The test consisted of swallowing a small amount of radiotracer (technetium-99m labeled liquid) followed by immediate image acquisition by a gamma camera. ETS was performed in upright position. Data were analysed using standard nuclear medicine software for generating time/activity curves from dynamic studies. Regions of interest were drawn for the upper, middle, and lower thirds of the esophagus. Time/activity curves derived from the middle and distal thirds were evaluated and interpreted by a nuclear medicine physician. Qualitatively the esophageal transit was classified as normal or delayed. Quantitatively, the EA was considered abnormal, if <90% of bolus was cleared in 10 seconds and the percentage number of the EA (0–100%) was calculated.

Statistics

Continuous variables were expressed as mean(SD) (if normally distributed) and as median(IQR) (if not normally distributed); and categorical data as number and percentage. Unpaired t test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) test or two-tailed Mann–Whitney and Kruskall–Wallis tests were used for comparison between two or more groups, respectively. Bonferroni and Dunn’s tests were used for multiple comparisons. Parametric and non-parametric correlations were calculated using Pearson’s and Spearman’s rank correlation tests, respectively. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software 7.0 (San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

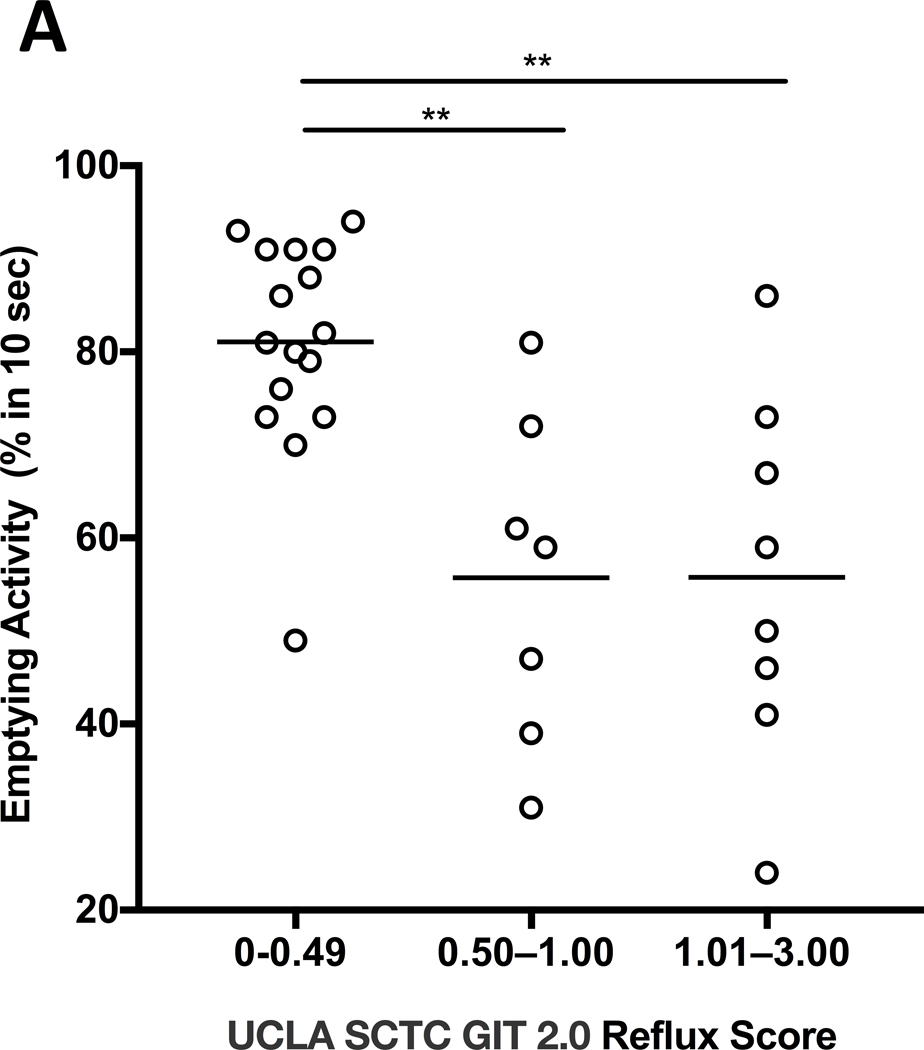

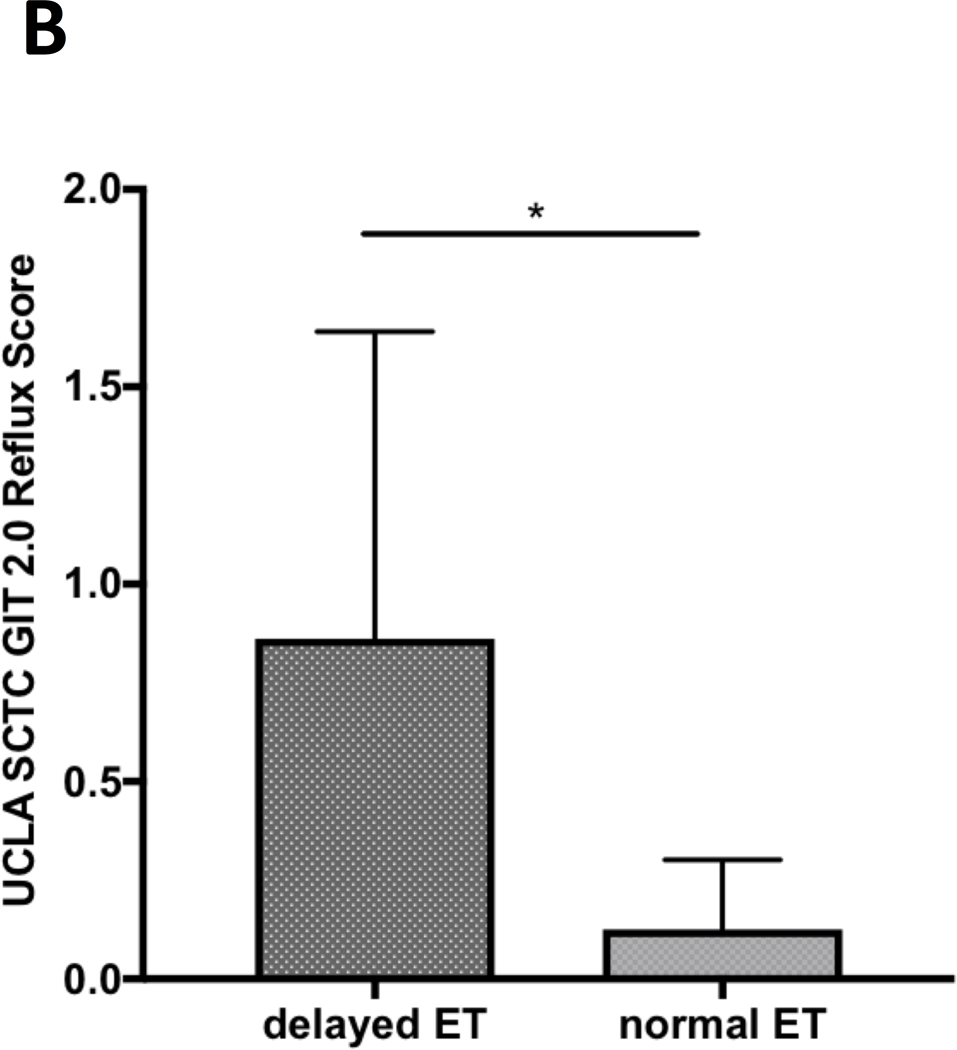

Of all the SSc patients admitted to our in-patient clinic from 1st Sept 2017 to 31st December 2019, thirty-one underwent ETS. Clinical features, reported symptoms and GIT-2.0 scores are shown in Table 1. Twenty-seven patients were female, 3 with sine scleroderma, 19 with limited cutaneous and 9 with diffuse cutaneous subsets. At the time of admission, 24 (77.4%) patients were on proton pump inhibitors and 6 (19.4%) on prokinetic therapy. Twenty-six/31 (84%) patients had a delayed transit and an abnormal esophageal EA. Overall, EA of the 31 patients ranged from 24% to 94% with a mean (SD) of 68.6%(19.5). Sixteen (51.6%) patients had none-to-mild (0.00–0.49), 6 (19.4%) moderate (0.50–1.00), and 9 (29%) severe-to-very-severe (1.01–3.00) GIT-2.0 reflux scores (7). The mean EA was significantly different across those three groups of reflux score (p=0.0004). Multiple comparison test showed that the significance was due to difference in none-to-mild vs. other groups; specifically mean (SD) EA was higher in patients with none-to-mild [81.1(11.5)] than in those with moderate [55.7(17.8), p=0.003] and severe-to-very-severe [55.8(19.7), p=0.002] reflux scores (Figure 1.A). The 26 (84%) SSc patients with delayed esophageal transit had higher mean (SD) GIT-2.0 reflux score than the remaining 5 (16%) patients [0.9(0.8) vs 0.1(0.2), p=0.04] (Figure 1.B).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the systemic sclerosis patients

| Gender, M/F | 4/27 |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 53.5 (13.6) |

| White ethnicity, n (%) | 31 (100) |

| Clinical Subset (sine scl/L/D), n | 3/19/9 |

| Disease duration, years, mean (SD) | 7.7 (7) |

| ANA, n (%) | 31 (100) |

| Anticentromere, n (%) | 10 (32.3) |

| Anti-topoisomerase I, n (%) | 12 (38.7) |

| Anti-Th/To, n (%) | 2 (6.5) |

| Anti Pm/Scl, n (%) | 1 (3.2) |

| Anti U1-RNP, n (%) | 1 (3.2) |

| mRss, median (IQR) | 3 (0–9) |

| Reported symptoms, n (%): | |

| ■ esophageal (reflux, dysfagia) | 20 (64.5) |

| ■ gastric (early satiety, vomiting) | 7 (22.6) |

| ■ intestinal (bloating, diarrea, constipation) | 15 (48.4) |

| ■ dyspnea | 10 (32.3) |

| GIT-2 questionnaire scales, mean (SD): | |

| ■ reflux | 0.74 (0.76) |

| ■ distention/bloating | 0.77 (0.65) |

| ■ fecal soiling | 0.45 (0.85) |

| ■ diarrhea | 0.49 (0.59) |

| ■ social functioning | 0.39 (0.53) |

| ■ emotional well-being | 0.45 (0.71) |

| ■ constipation | 0.48 (0.57) |

| ■ total score | 0.55 (0.5) |

| Forced Vital Capacity % predicted, mean (SD) | 89.5 (17.7) |

| Diffusion Lung Capacity for CO % predicted, mean (SD) | 74.1 (14.3) |

| Chest High Resolution CT scan: | |

| ■ Normal, n (%) | 13 (41.9) |

| ■ Ground glass opacity, n (%) | 10 (32.3) |

| ■ Fibrosis, n (%) | 10 (32.3) |

| PPIs, n (%) | 24 (77.4) |

| Prokinetics, n (%) | 6 (19.4) |

| Immunosuppressive therapy, n (%) | 11 (35.5) |

ANA, antinuclear antibody; CO, carbon monoxide; CT, computed tomography; D, diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis; L, limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis; mRss, modified Rodnan skin score; PPIs, proton pump inhibitors; Sine scl, sine scleroderma.

Figure 1 (A-C).

A. Comparison of the esophageal emptying activity across the three groups of patients classified based on “none-to-mild” (0.00–0.49), “moderate” (0.50–1.00) and “severe-to-very-severe” (1.01–3.00) GIT 2.0 reflux score. The esophageal emptying activity is expressed as percentage (%) after 10 seconds from swallowing a small amount of radiotracer; ** p<0.01. B. Comparison of UCLA SCTC GIT 2.0 reflux score between SSc patients with delayed esophageal transit (ET) and those with normal transit as assessed by esophageal scintigraphy; * p<0.05. C. Negative significant correlation between percentage (%) of esophageal emptying activity and UCLA SCTC GIT 2.0 reflux score.

EA negatively correlated with the GIT-2.0 reflux score (r=− 0.68, p<0.0001) (Figure 1.C) while it did not correlate with the other scales and the total GIT-2.0 score. Sub-analysis showed that total GIT-2.0 score significantly correlated with HAQ (r=0.44, p=0.0135) and VAS-GI (r=0.47, p=0.0071) while GIT-2.0 reflux score correlated with HAQ (r=0.51, p=0.0043) but it did not correlate with VAS-GI. Both GIT-2.0 total and reflux score did not correlate with the VAS dyspnea.

Discussion

GI involvement is one the main causes of morbidity in SSc and GIT-2.0 is a validated instrument to capture symptoms and impact on social and mental well-being in SSc. Our current analysis shows that GIT-2.0 reflux scale is valid in those with impaired ETS.

The prevalence of esophageal transit abnormalities was 84% in our SSc patients, in line with results of previous studies ranging from 77 to 100%, despite methodological differences in the scintigraphy results evaluation (19,20).

Previous studies assessed the associations between esophageal symptom i.e. reflux and other objective upper GI tools. In fifty-five SSc patients enrolled at 2 centres, Bae S. et al compared the GIT-2.0 reflux scale with upper GI endoscopy (n=36), esophageal manometry (n=30) and barium swallow (n=22) (7). The reflux scale had moderate correlations with GI endoscopy (r=0.46, p=0.01) and esophageal manometry evaluations (r=0.51 and 0.48 for decreased peristalsis and LES pressure respectively, p=0.01 for both). No correlation was found with barium swallow however patients with reflux scale abnormalities assessed by this technique had higher mean (SD) reflux score than those with a normal barium swallow [0.93(0.69) vs. 0.77(0.46), p=ns] (7).

Another study explored the association between high resolution manometry findings and GIT-2.0 in 40 Egyptian SSc patients (8). Distal esophageal amplitude and LES resting pressure negatively correlated with reflux score (r=−0.64; p=0.001 and r=−0.46; p=0.019, respectively), and total GIT score (r=−0.54; p=0.007 and r=−0.42; p=0.03, respectively). LES resting pressure had negative correlations with diarrhea score (r=−0.062; p=0.002) (8).

In this study, the lack of correlation with GIT-2.0 total score may be related to the composite nature of the score capturing overall GI disease aspects. Thus, the results of our study on ETS were a priori expected to correlate mostly with reflux scale of GIT-2.0.

Limitations of this study include the low number of patients analysed. This was related to the nature of the study as conducted in clinical care where ETS is not routinely done in all SSc patients admitted to the inpatient clinic. Furthermore, there was a high prevalence of anti-topoisomerase I positive patients, related to the fact that in-patient clinic admission is planned based on physician judgment of known or suspected organ involvements. Also some patients were receiving symptomatic treatment which may have influenced the reported symptoms. Furthermore, for the same clinical nature, our study did not have a control group thus we are unable to comment on the screening ability for esophageal dysmotility in SSc patients.

In conclusion the results of our study confirm the association, previously found with other upper GI tools, of GIT-2.0 reflux scale with ETS.

The GIT-2.0 reflux scale is a complementary tool for objective measurement of esophageal involvement and can be easily administered in day-to-day clinical assessment.

Source(s) of support in the form of grants or industrial support:

D Khanna: NIH Funded AR063120: Outcomes Research in Rheumatic Diseases (K24)

F Del Galdo declares the following conflict of interests:

Research grants and honoraria not relevant to the topic of the article from GSK, AstraZeneca, Capella Biosciences, Kymab, Chemomab, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Actelion, Boehringer-Ingelheim;

D Khanna declares the following conflict of interests:

Grant support: NIH, Immune Tolerance Network, Bayer, BMS, Horizon, Pfizer; Consultant: Acceleron, Actelion, Abbvie, Amgen, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, CSL Behring, Corbus, Galapagos, Genentech/Roche, GSK, Horizon Merck, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Sanofi-Aventis, and United Therapeutics; CME programs: Impact PH; Stocks: Eicos Sciences, Inc (less than 5%); Leadership/Equity position – Chief Medical Officer, CiviBioPharma/Eicos Sciences, Inc.

Footnotes

Conflict of interests:

The other authors declare no conflicts of interests.

Initials, surnames, appointments, and highest academic degrees of all authors:

G Abignano, Clinical Researcher and Honorary Consultant Rheumatologist, MD PhD

GA Mennillo, Consultant Rheumatologist, MD

G Lettieri MD, Consultant Radiologist, MD

D Temiz Karadag, Consultant Rheumatologist, MD

A Carriero, PhD Fellow, MD

AA Padula, Consultant Rheumatologist, MD

F Del Galdo, Associate Professor, MD PhD

D Khanna, Professor, MD MS

S D’Angelo, Consultant Rheumatologist, MD PhD

References:

- 1.Varga J, Trojanowska M, Kuwana M. Pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis: recent insights of molecular and cellular mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. J Scleroderma Relat Disord 2017;2:137–52. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sjogren RW. Gastrointestinal motility disorders in scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum 1994;37:1265–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vischio J, Saeed F, Karimeddini M, Mubashir A, Feinn R, Caldito G, et al. Progression of Esophageal Dysmotility in Systemic Sclerosis. J Rheumatol 2012;39:986–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ziessman HA. Gastrointestinal Transit Assessment: Role of Scintigraphy: Where Are We Now? Where Are We Going? Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 2016;14:452–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McMahan ZH, Frech T, Berrocal V, Lim D, Bruni C, Matucci-Cerinic M, et al. Longitudinal Assessment of Patient-reported Outcome Measures in Systemic Sclerosis Patients with Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease - Scleroderma Clinical Trials Consortium. J Rheumatol 2019;46:78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khanna D, Hays RD, Maranian P, Seibold JR, Impens A, Mayes MD, et al. Reliability and validity of the University of California, Los Angeles Scleroderma Clinical Trial Consortium Gastrointestinal Tract Instrument. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:1257–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bae S, Allanore Y, Furst DE, Bodukam V, Coustet B, Morgaceva O, et al. Associations between a scleroderma-specific gastrointestinal instrument and objective tests of upper gastrointestinal involvements in systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2013;31:57–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abozaid HSM, Imam HMK, Abdelaziz MM, El-Hammady DH, Fathi NA, Furst DE. High-resolution manometry compared with the University of California, Los Angeles Scleroderma Clinical Trials Consortium GIT 2.0 in Systemic Sclerosis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2017;47:403–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, Johnson SR, Baron M, Tyndall A, et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American college of rheumatology/European league against rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1747–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abignano G, Cuomo G, Buch MH, Rosenberg WM, Valentini G, Emery P, et al. The enhanced liver fibrosis test: a clinical grade, validated serum test, biomarker of overall fibrosis in systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:420–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gualtierotti R, Ingegnoli F, Two R, Meroni PL, Khanna D, Adorni G, et al. ; VERITAS study group. Reliability and validity of the Italian version of the UCLA Scleroderma Clinical Trial Consortium Gastrointestinal Tract Instrument in patients with systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2015;33:S55–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.La Montagna G, Cuomo G, Chiarolanza I, Ruocco L, Valentini G. HAQ-DI Italian version in systemic sclerosis. Reumatismo 2006;58:112–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steen VD, Medsger TA. The value of the Health Assessment Questionnaire and special patient-generated scales to demonstrate change in systemic sclerosis patients over time. Arthritis Rheum 1997;40:1984–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khanna D, Nagaraja V, Gladue H, Chey W, Pimentel M, Frech T. Measuring response in the gastrointestinal tract in systemic sclerosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2013;25:700–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pope J Measures of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma): Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) and Scleroderma HAQ (SHAQ), physician- and patient-rated global assessments, Symptom Burden Index (SBI), University of California, Los Angeles, Scleroderma Clinical Trials Consortium Gastrointestinal Scale (UCLA SCTC GIT) 2.0, Baseline Dyspnea Index (BDI) and Transition Dyspnea Index (TDI) (Mahler’s Index), Cambridge Pulmonary Hypertension Outcome Review (CAMPHOR), and Raynaud’s Condition Score (RCS). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63:S98–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khanna D, Furst DE, Maranian P, Seibold JR, Impens A, Mayes MD, et al. Minimally important differences of the UCLA Scleroderma Clinical Trial Consortium Gastrointestinal Tract Instrument. J Rheum 2011;38:1920–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bae S, Allanore Y, Coustet B, Maranian P, Khanna D. Development and validation of French version of the UCLA Scleroderma Clinical Trial Consortium Gastrointestinal Tract Instrument. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2011;29:S15–21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baron M, Hudson M, Steele R, Lo E. Canadian Scleroderma Research G. Validation of the UCLA Scleroderma Clinica Trial Gastrointestinal Tract Instrument version 2.0 for systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol 2011;38:1925–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pitrez EH, Bredemeier M, Xavier RM, Capobianco KG, Restelli VG, Vieira MV, et al. Oesophageal dysmotility in systemic sclerosis: comparison of HRCT and scintigraphy. Br J Radiol 2006;79:719–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaye SA, Siraj QH, Agnew J, Hilson A, Black CM. Detection of early asymptomatic esophageal dysfunction in systemic sclerosis using a new scintigraphic grading method. J Rheumatol 1996;23:297–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]