Abstract

Progression of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) entails deterioration or aberrant function of multiple brain cell types, eventually leading to neurodegeneration and cognitive decline. Defining how complex cell-cell interactions become dysregulated in AD requires novel human cell-based in vitro platforms that could recapitulate the intricate cytoarchitecture and cell diversity of the human brain. Brain organoids (BOs) are three-dimensional self-organizing tissues that partially resemble the human brain architecture and can recapitulate AD-relevant pathology. In this Review, we highlight the versatile applications of different types of BOs to model AD pathogenesis, including amyloid-β and tau aggregation, neuroinflammation, myelin breakdown, vascular dysfunction, and other phenotypes, as well as to accelerate therapeutic development for AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, brain organoids, induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), ApoE4, drug discovery, myelin organoids

Brain organoids recapitulate cellular diversity of the human brain

A groundbreaking development of the induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology has enabled disease modeling in vitro using patient-derived cellular models [1–3]. Human iPSC-based disease models overcome the difficulty of obtaining primary human tissues, such as brain tissue, as well as the issue of species divergence when using animal models [4, 5]. Although two-dimensional (2D) cell culture models have dominated in vitro research, more complex cellular assemblies are required to faithfully recapitulate multifaceted pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The emergence of human organoid technology bridges the gap between 2D models and the complex three-dimensional (3D) environment in vivo. Brain organoids (BOs) are 3D stem cell-derived tissues that mimic the cellular composition and structure of the human brain [6–9]. BOs can be engineered to contain the diversity of human brain cell types, including neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, microglia, pericytes, and epithelial cells (see Box 1). BOs also exhibit complex cytoarchitecture and electrophysiological properties, facilitating the study of neurodegeneration and cognitive decline (see Box 2).

Box 1: Techniques for brain organoid differentiation.

Numerous BO differentiation protocols to derive neural structures of the desired brain region and incorporate different cellular components have been developed [9, 103–105]. Generally, pluripotent stem cells are first aggregated into embryoid bodies and induced towards the neuroectoderm lineage [39]. Signaling molecules can be added to promote guided differentiation, patterning the BO towards a specified regional identity; alternatively, unguided differentiation yields neural organoids that contain patches of tissue of various brain regional identities [39, 105].

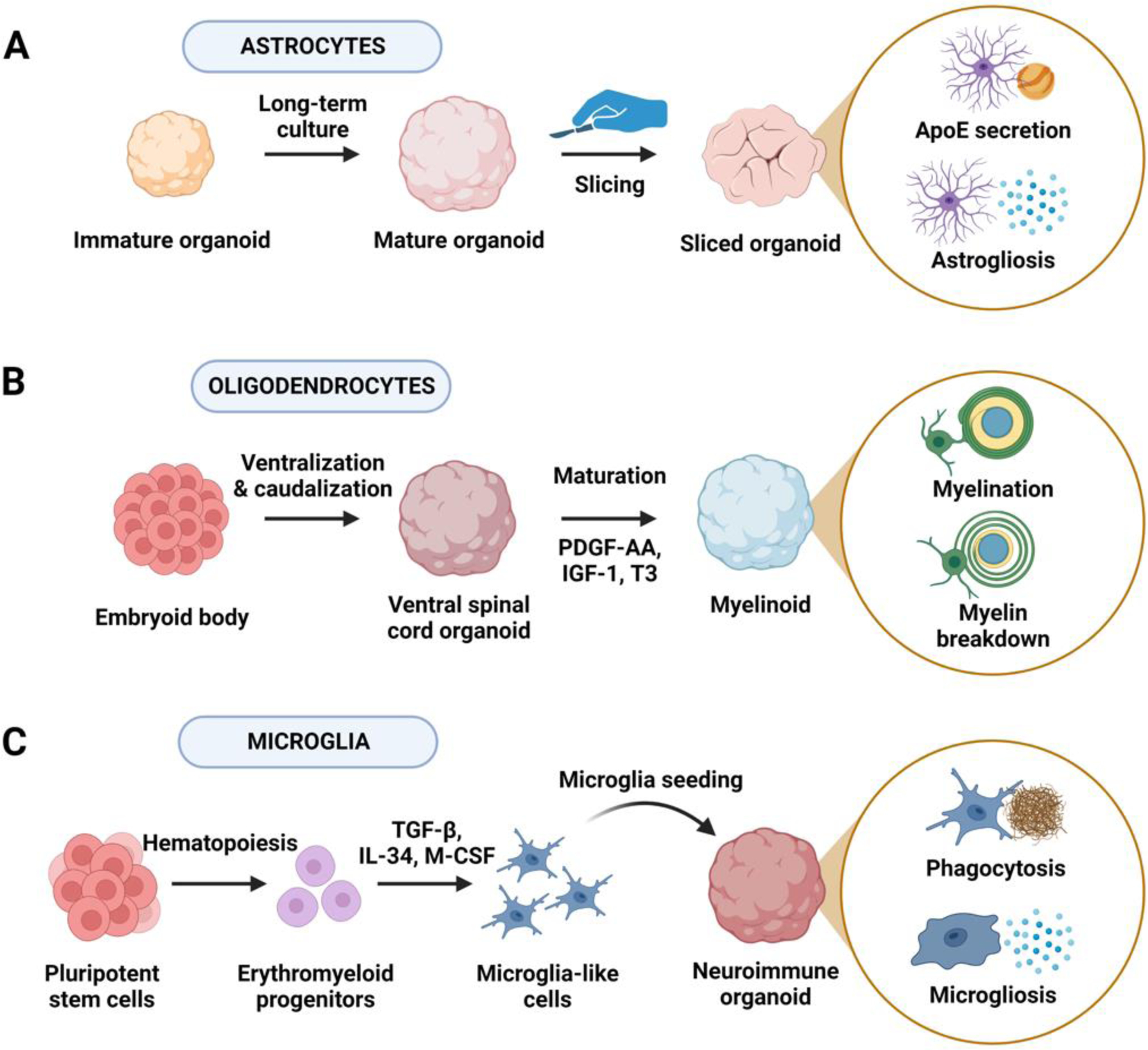

Enrichment of BOs with glial cells necessitates cell type-specific strategies, given the variable developmental timing and ontogeny of glial cells [104]. Astrocytes arise only after the neurogenic-to-gliogenic transition of radial glia in the developing human brain [104]. Similarly, astrocytes spontaneously arise following long-term culture of BOs [62, 106]. Given the protracted nature of human brain myelination, additional signaling cues are required to induce oligodendrocyte progenitor cell (OPC) and oligodendrocyte development in BOs [23]. Supplementation of signaling molecules required for oligodendrogenesis, including platelet-derived growth factor AA (PDGF-AA), insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), and thyroid hormone (T3), promotes OPC and oligodendrocyte differentiation as well as neuron myelination in specialized BOs termed myelinoids [66–68]. Alternatively, ectopic expression of the oligodendrocyte transcription factor 2 (OLIG2) promotes directed differentiation of OPCs and oligodendrocytes in the myelinoid [65]. Myelination can further be improved by patterning the myelinoid identity towards the ventral spinal cord, where oligodendrogenesis begins during brain development [68]. Microglia and brain vasculature arise from the mesoderm, whereas mesoderm specification is generally suppressed during guided BO differentiation. Therefore, iPSC-derived microglia can be seeded onto differentiated BOs to allow infiltration [70]. Microglia-containing neuroimmune organoids can also be derived by ectopic expression of the microglial fate-determining transcription factor PU.1 during BO differentiation [71]. Alternatively, iPSC-derived microglia progenitors can be mixed with neural progenitors before BO differentiation [73]. Microglia may also develop innately during unguided BO differentiation; however, the reproducibility of this approach remains to be clarified [107]. Vascularized BOs can be obtained by ectopic expression of the Ets variant transcription factor 2 (ETV2) during BO differentiation [78]. Alternatively, integration of pericytes into differentiating BOs yields pericyte-containing BOs [81]. Self-organized iBBB can be obtained by mixing astrocytes, pericytes, and endothelial cells in a 3D hydrogel or assembling these cells into a spheroid [30, 79]. Finally, a combination of WNT and BMP signaling pathway activation has been applied to generate choroid plexus organoids (ChPOs) [83, 84].

Box 2: Modeling electrophysiology of Alzheimer’s disease using brain organoids.

Human brain electrical activity reflects neuronal network connectivity and cognitive functions. Although electrophysiological recordings are cost-effective and non-invasive, identification of electrophysiological markers as a diagnostic tool for AD remains a challenge [108]. Nevertheless, novel insights into electrophysiological activity of AD-afflicted neuronal networks may be obtained by recording electrical activity of 3D human BOs that form relatively complex neuronal networks as compared to 2D neuronal cultures. Electrical activity of cortical BOs increases over the course of differentiation and exhibits alternating periods of synchronized events and quiescence, reminiscent of early brain development in vivo [109]. Other modifications, such as BO vascularization or microglia infiltration, also facilitate BO electrical maturation [71, 72, 78, 110, 111]. For example, neuroimmune organoids exhibit increased frequency of oscillatory bursts and synchronization as compared to microglia-lacking BOs [71, 72, 110].

Emerging evidence indicates that BOs derived from AD patients also recapitulate neuronal network dysfunction characteristic of AD patients. For example, neuronal hyperexcitability and increased prevalence of epileptiform activity are evident in AD patients [112]. Indeed, neuronal hyperexcitability has also been document in fAD, sAD, and ApoE4 BOs [50, 113, 114]. Furthermore, cortical and ganglionic eminence assembloids integrate excitatory and inhibitory neurons, enabling the emergence of more complex electrophysiology [115]. Such assembloids exhibit epileptiform-like activity in a disease setting, whereas aberrant neuronal activity can be modulated pharmacologically [115]. Deterioration of BO electrical activity may also be used as a readout for cognitive decline; therefore, it will be important to characterize how various AD-relevant insults affect BO electrical activity over the course of disease progression. Notably, serum exposure and HSV-1 infection both result in impaired electrical activity of BOs [62, 89].

2D microelectrode arrays (MEAs) are often used to record neuronal activity in whole or sliced BOs [62, 109, 116]. However, engineered solutions to record BO electrical activity across the BO surface area and without the need for slicing would facilitate spatiotemporal recording during BO differentiation and beyond. Novel self-folding MEA caps overcome the constraints of 2D MEAs and can wrap around the organoids of different sizes in 3D space [117]. Moreover, cyborg organoids integrate stretchable mesh nanoelectronics arrays across the organoid to further increase the interface area between neurons and electrodes [118]. Such 3D electrode interfaces will enable investigators to assess how various AD-relevant genetic and environmental insults drive the deterioration of neuronal networks over time.

In this Review, we begin by considering the immense complexity of cell-cell interactions that deteriorate during AD progression; we also discuss the importance and advantages of using human cell-based models for studying AD. Subsequently, we draw on the recent advances in developing various BO models, including neural organoids, myelinoids, neuroimmune organoids (NIOs), blood-brain barrier (BBB) organoids, and choroid plexus organoids (ChPOs), to highlight their potential for modeling AD pathogenesis and developing novel therapeutics for AD.

Cell-cell interactions in Alzheimer’s disease

AD is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that presents with cognitive decline and is the most common cause of dementia [10]. Most AD cases are sporadic (sAD), whereas autosomal dominant familial AD (fAD) comprises about 1% of all AD cases and is caused by mutations in presenilin 1 (PSEN1), presenilin 2 (PSEN2), and amyloid precursor protein (APP) genes [11]. The neuron-centric Amyloid Hypothesis has been the leading theory for how AD develops and progresses, postulating that amyloid-β (Aβ) accumulation and toxicity initiate a cascade of events culminating in neurodegeneration and cognitive decline [11]. Extensive efforts to target Aβ pathology have resulted in recent accelerated approvals for monoclonal antibodies aducanumab and lecanemab by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [12–14]. Hyperphosphorylation and aggregation of the microtubule-associated protein tau is another hallmark of AD [10]. In recent years, tau has become a major focus in AD research, given the emerging evidence that tau pathology can develop and progress independently of Aβ [15]. Moreover, spatial and temporal correlation between tau pathology and neurodegeneration is much stronger than that between Aβ pathology and neurodegeneration, highlighting the importance of tau in disease progression [15]. In addition to neuronal Aβ and tau pathology, genome-wide association studies (GWAS, see Glossary), high-throughput profiling of gene expression, and functional experiments have revealed remarkable complexity of genetic risk factors, aging, cellular states, and cell-cell interactions that together drive AD pathogenesis [16–22]. Novel hypotheses for AD progression, including the Cellular Phase, ApoE Cascade, Myelin Breakdown and Neuroinflammation hypotheses have emerged [17, 18, 23, 24]. As the strongest genetic risk factor for AD, the E4 variant of the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene has been linked to dysfunctional lipid metabolism, impaired myelination, heightened neuroinflammation, and vascular breakdown, among other phenotypes, exemplifying the immense complexity of cellular interactions that go awry in AD [18, 21, 25]. As the primary source of the secreted ApoE protein, astrocytes orchestrate brain lipid metabolism that is essential for neuronal physiology, injury repair, and myelin remodeling [17]. Astrocytes also maintain systemic homeostasis of the neuronal circuitry, remodel synapses, and form the glia limitans membrane at the BBB. In AD, astrocytes undergo reactive astrogliosis, leading to deterioration of their supportive functions, increased pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion, and neurotoxicity [17, 26]. Oligodendrocytes provide metabolic support to neurons and produce the myelin sheath for neuron electrical insulation [17]. The Myelin Breakdown Hypothesis postulates the central importance of myelin integrity to brain homeostasis, whereas myelin breakdown drives neurodegeneration and cognitive decline in AD [23, 27]. Moreover, excessive myelin debris may activate microglia, initiating neuroinflammation [27]. As the brain resident macrophages, microglia survey the brain environment, prune synapses, phagocytose debris, and mount an immune response to a pathogenic stimulus [17]. Microglial ability to remove toxic Aβ debris indicates a protective role in AD; however, at later stages of the disease, microglia drive neuroinflammation and may even propagate Aβ into unaffected brain regions [28]. Finally, brain vasculature coordinates energy metabolism and forms the BBB that protects the privileged brain environment from peripheral neurotoxic factors [17]. Moreover, the choroid plexus (ChP) forms the blood-cerebrospinal fluid (B-CSF) barrier and secretes CSF that facilitates metabolite exchange across the brain and serves a protective function [29]. Yet, deterioration of the brain vasculature in AD manifests as vascular loss, cortical hypoperfusion, BBB breakdown, and cerebral amyloid angiopathy, among other phenotypes [22, 30, 31]. Oligomeric Aβ drives capillary constriction and pericyte dysfunction, whereas profiling of the CSF proteome reveals dozens of dysregulated proteins in AD patients [32, 33]. All these cellular phenotypes converge to drive neuronal network degeneration, neuron cell death, and ultimately, cognitive decline. Therefore, defining how diverse cell-cell interactions deteriorate in AD and contribute to synaptic loss and neuronal cell death is a pivotal goal for future therapeutic development.

Species divergence necessitates human iPSC-based models of Alzheimer’s disease

Species differences between human and mouse brains have been a significant hurdle in translating rodent-based findings into viable AD therapies in the clinic [16]. High-throughput profiling studies have revealed considerable divergence in transcriptional programs of the brain cell types, differences in cortical cell organization, and notably increased cell-cell contacts in the human cortex [34, 35]. The divergence in gene expression profiles is particularly apparent in non-neuronal cells; for example, human but not mouse microglia are enriched for expression of AD risk genes [36]. Transcriptional divergence also implies phenotypic differences. Indeed, human and mouse astrocytes exhibit contrasting programs of energy metabolism, response to inflammatory stimulation, and susceptibility to oxidative stress [37]. Divergent oligodendrocyte gene expression profiles manifest in notable differences in myelin proteomes [38]. Species differences are also evident in the brain vasculature. Brain endothelial cells (BECs) and pericytes exhibit among the most divergent transcriptional profiles between human and mouse brain cell types [22]. These differences are amplified in a disease setting; for example, there is little overlap of differentially expressed genes between BECs isolated from AD patients and an AD mouse model when compared to healthy controls [22]. Consequently, considerable species divergence has hindered the elucidation of human-specific disease mechanisms and, by extension, therapeutic development for AD. BO technology enables modeling of AD in all-human cellular systems, so that human-relevant molecular mechanisms of AD pathogenesis can be uncovered.

Brain organoid models of Alzheimer’s disease

Unravelling the complexity of AD pathogenesis requires diverse BO models that resemble distinct structures of the human brain and incorporate specialized cell types. In this section, we highlight the applications of different BO models to study various aspects of AD pathogenesis.

Neural organoids

Neural or cerebral organoids are the most widely used 3D pluripotent stem cell-derived models of the human brain tissue to study brain diseases, including AD [6, 39]. Neural organoids derived from iPSCs of fAD patients robustly develop AD-relevant pathology, including Aβ aggregation and tau hyperphosphorylation (reviewed in [40]). These neural organoids also exhibit synaptic loss, impaired neuronal activity (Box 2), and neuronal cell death, in addition to other phenotypes, such as endosomal dysfunction [40]. Tau pathology is also evident in neural organoids that express mutant tau variants associated with frontotemporal dementia but relevant in a broader context of tauopathies, including AD [41]. For example, mutant tau-V337M neural organoids accumulate phosphorylated tau (p-tau) and exhibit impaired proteostasis, neuroinflammation, dysregulated lipid metabolism, and selective loss of glutamatergic neurons [42, 43]. Moreover, Aβ and tau pathology can be induced in a controllable manner, such as by treating neural organoids with an amyloidogenesis activator Aftin-5 or by injecting adeno-associated virus (AAV) carrying a mutant tau expression cassette [44, 45]. In this way, both independent and synergistic effects of Aβ and tau pathology on AD progression may be investigated using neural organoids [46, 47]. An important consideration is whether the conformation of tau aggregates in neural organoids resembles that of in vivo inclusions. Indeed, iPSC-derived neurons lack tau isoform diversity of the human brain, which may affect tau oligomerization and fibrillization properties in neural organoids [48]. AAV-mediated expression of a mutant tau-P301L that is more prone to aggregation than wild-type tau may overcome this limitation, leading to formation of tau oligomers and fibrils reminiscent of late tau pathology in AD [45]. Finally, self-propagation of aggregated tau can be modeled using astrocyte-neuron spheroids, where p-tau pathology is readily propagated from neurons pre-treated with tau to untreated neurons [49].

Although AD-relevant pathology can be induced by overt dysfunction or manipulation of the amyloid and tau cascades, neural organoids can also reveal subtle contributions of genetic and environmental risk factors for sAD. Neural organoids derived from iPSCs of sAD patients secrete more Aβ40, Aβ42, and p-tau than do neural organoids derived from healthy controls, indicating neuronal dysfunction [50]. Interestingly, the secreted amounts of Aβ40, Aβ42 and p-tau correlate with the Aβ burden detected by positron emission tomography in corresponding sAD patients, indicating the sensitivity of the BO technology for modeling sAD [50]. Neural organoids carrying genetic risk variants, such as APOE4, and their isogenic corrected controls can also be engineered by CRISPR/Cas9 editing (see Figure 1). Isogenic disease models eliminate the confounding effects of patient-to-patient variation and reveal genetic risk factor-specific phenotypes; this technique is often applied to generate isogenic iPSC lines carrying different APOE variants [51]. To study the impact of ApoE isoforms on AD progression using neural organoids, robust astrocyte differentiation is required (see Figure 2A, Key Figure); indeed, immature neural organoids express little APOE because they lack astrocytes [51]. As the organoids mature, radial glia and astrocytes secrete ApoE that is diffusively distributed throughout the 3D space of the organoid [51, 52]. APOE4 neural organoids accumulate more Aβ and p-tau than do APOE3 neural organoids although this phenotype may depend on neural organoid maturation [51, 53]. Neural organoids may thus be used to investigate how ApoE4 interacts with tau to drive AD-relevant pathology, given the recent observation that removal of neuronal ApoE4 suppresses tau pathology in vivo [25]. Neural organoids are also amenable to pharmacological manipulation, indicating their utility for testing novel therapeutic candidates [42, 49, 54]. Therefore, tau-targeting therapies, such as the recently developed tau-degrading intrabodies, as well as ApoE-targeting antibodies or antisense nucleotides could be tested in neural organoids [55–58]. However, it is important to note that different neural organoid differentiation protocols and variable organoid-to-organoid reproducibility (see Box 3) may affect the experimental findings obtained from neural organoid studies. For example, Hernández et al. found that ApoE, Aβ42, and p-tau levels were highly variable within the groups of ApoE3 and ApoE4 neural organoids; as a result, there was no statistically significant difference between ApoE, Aβ42, and p-tau levels of isogenic ApoE3 and ApoE4 neural organoids [59]. This discrepancy may also be attributed to the relatively mild ApoE isoform-dependent phenotypes as compared to those stemming from causal disease mutations.

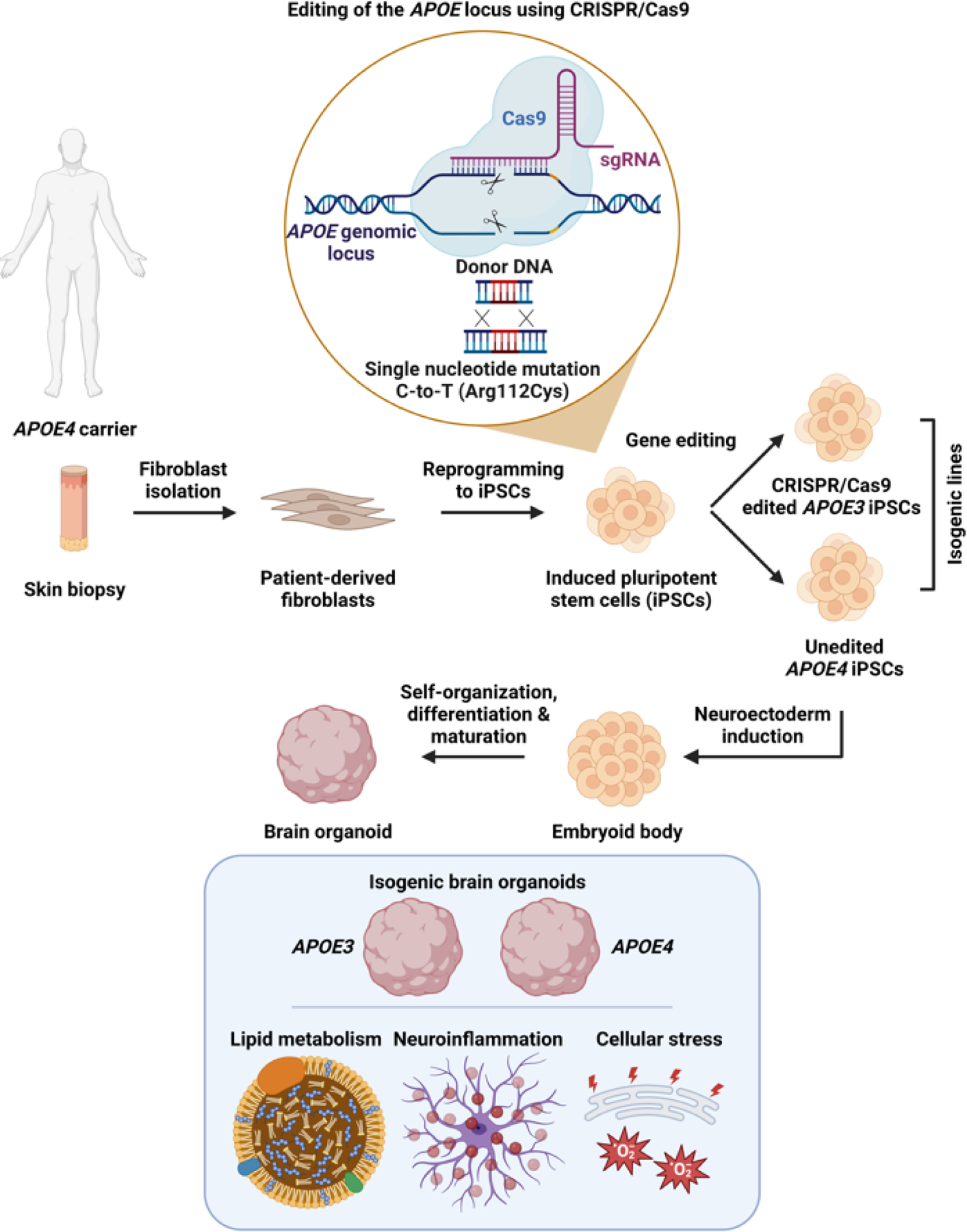

Figure 1: Generation and applications of isogenic APOE3 and APOE4 brain organoids.

Patient-derived fibroblasts are first obtained from a skin biopsy of a carrier of APOE4. Fibroblasts are then reprogrammed into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), and a single nucleotide point mutation (cytosine-to-thymine) is introduced using CRISPR/Cas9-based genetic editing, resulting in a missense mutation and exchange of arginine (Arg) for cysteine (Cys), generating the APOE3 variant. Subsequently, unedited APOE4 iPSCs and isogenic edited APOE3 iPSCs are differentiated into brain organoids (BOs) following well-established protocols. The resulting BOs share the same genetic background except for the APOE variant, enabling mechanistic studies of the roles of ApoE isoforms in lipid metabolism, neuroinflammation, cellular stress, and other processes, without the confounding effects of patient-to-patient variation.

Figure 2 (Key Figure): Strategies for obtaining glial cell-enriched brain organoids.

(A) Long-term culture of neural organoids promotes astrocyte differentiation as radial glia progenitors undergo the neurogenic-to-gliogenic transition. Long-term maintenance of neural organoids can be further improved by slicing spherical organoids and maintaining sliced organoids to allow efficient nutrient and oxygen exchange. Astrocyte-enriched neural organoids can be used to study astrocyte lipid metabolism and astrogliosis in AD, among other roles. (B) Supplying key signaling molecules required for oligodendrocyte progenitor cell (OPC) and oligodendrocyte differentiation, including platelet-derived growth factor AA (PDGF-AA), insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), and thyroid hormone (T3), promotes OPC and oligodendrocyte differentiation in myelinoids. Patterning myelinoids towards ventral spinal cord identity can further improve myelination. Oligodendrocyte-enriched myelinoids can be used to study the effects of myelination and myelin breakdown in AD. (C) Given that microglia arise from a different germ layer (mesoderm) than do neural tissues (ectoderm), generation of microglia-containing neuroimmune organoids (NIOs) can be achieved by seeding induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived microglia into differentiated BOs. To obtain microglia, iPSCs are differentiated into an erythromyeloid progenitor-like intermediate followed by microglia differentiation and maturation in the presence of transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), interleukin 34 (IL-34), and macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF). Microglia-enriched NIOs can be used to study phagocytosis of toxic debris and microgliosis in AD.

Box 3: Rigor and reproducibility of brain organoid technology.

To reach the full potential of modeling AD using BO technology, it is critical to ensure rigorous differentiation of organoids that faithfully and reproducibly recapitulate key features of the human brain. However, self-organization in vitro, especially when relying on unguided BO differentiation, exhibits substantial organoid-to-organoid variation [59, 119, 120]. BOs derived by unguided differentiation not only contain an assortment of cells from various brain regions, but also develop non-ectodermal cell types, including microglia [39, 107]. Thus, while unguided differentiation may increase the cell type diversity, it also affects reproducibility across individual BOs and may confound experimental findings. On the contrary, guided BO differentiation yields highly reproducible BOs. Single-cell sequencing of forebrain organoids reveals remarkable reproducibility of cell types with variation comparable to that of human brain development [119–121]. Therefore, unguided BO differentiation may be more suitable for exploratory experiments, whereas guided BO differentiation should be used for single-cell high-throughput profiling studies and drug screening applications, among others.

Rigor of the experiments using BO models also depends on how well BOs recapitulate the in vivo environment and whether BOs exhibit any phenotypes that could confound the experimental readout in the context of AD. Notably, BOs exhibit elevated expression of genes that regulate the pathways of endoplasmic reticulum stress and glycolysis [92]. Moreover, the lack of organoid vascularization is associated with internal hypoxia and increased hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF1A) expression as compared to vascularized organoids [78]. These phenotypes have also been implicated in AD progression and thus may confound experimental findings. For example, HIF-1α signaling orchestrates microglia metabolic reprogramming from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis upon encounter of Aβ, whereas AD patient-derived neurons undergo Warburg effect-like glycolytic reprogramming that may be dependent on HIF-1α [122, 123]. Internal BO necrosis may also activate inflammatory responses of microglia and astrocytes upon debris encounter. Therefore, investigators should be aware of these intrinsic BO limitations as well as the ways to overcome them. For example, improved nutrient and oxygen exchange using a microfluidics device leads to increased glucose consumption, lactate secretion, cell proliferation, and electrical activity as well as reduced necrosis and HIF-1α+ area in BOs [93]. Moreover, BO slicing reduces necrosis and enables long-term organoid maintenance [94, 95].

Neural organoids may also be used to define the effects of non-genetic risk factors on AD pathogenesis. For example, BBB leakage is a well-recognized AD risk factor that may be driven by aging [60, 61]. Exposure of neural organoids to human serum induces accumulation of insoluble Aβ aggregates and p-tau, among other phenotypes, indicating that BBB leakage may precipitate AD-relevant pathology [62]. Because AD is an age-related neurodegenerative disorder, the study of BBB leakage that occurs in aged brains offers a way to incorporate age-relevant events when modeling AD in vitro [60–62]. Moreover, given that serum exposure results in widespread AD-relevant pathology, it will be important to determine what specific peripheral factors induce neuronal toxicity upon BBB breakdown [62]. For example, liver-derived ApoE4 has recently been shown to trigger BBB breakdown, induce astrogliosis, and impair memory in vivo [63]. Emerging reports also indicate a role for peripheral immune cells in AD progression [31, 64]. We anticipate that complex organoid models that integrate peripheral effectors will reveal novel mediators of neurotoxicity originating from outside the brain.

Myelinoids

Although neural organoids robustly develop neurons and astrocytes, additional strategies to introduce other AD-relevant cell types are required (Box 1). Cortical myelinoids contain oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs) and oligodendrocytes as well as exhibit a degree of myelination [65–67]. Ventral spinal cord myelinoids (Figure 2B) further develop lamellae of compact myelin wrapped around neurons with comparable myelin thickness to that in vivo as well as nodes of Ranvier and paranodal junctions [68]. Yet, whether myelinoids with improved myelination but patterned towards the spinal cord identity are applicable to AD research remains to be shown. Given the accumulating evidence for the importance of myelin breakdown in AD, we anticipate that myelinoids will become an effective platform for examining disease-associated phenotypes, underlying molecular mechanisms, and therapeutic strategies targeting myelination programs [23, 27]. For example, APOE4 expression is associated with impaired myelination, whereas 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin, a compound that promotes cholesterol efflux, has recently been shown to improve myelination in APOE4-targeted replacement mice in vivo [69]. Whether such a beneficial effect can be demonstrated in human cell-derived 3D myelinoids that exhibit complex myelination patterns remains to be determined.

Neuroimmune organoids

Neuroimmune organoids (NIOs) (Figure 2C, Box 1) contain microglia that survey their environment, prune synapses, phagocytose debris, and respond to injury [70–73]. NIOs can be used to model clearance of AD-relevant debris as well as inflammatory responses of microglia that contribute to neuroinflammation in the brain. Upon oligomeric Aβ42 treatment, microglia become activated and phagocytose Aβ42 in NIOs, whereas gene expression profiling reveals enrichment for lysosome and phagocytosis-related pathways [71]. Given that several genetic risk factors for sAD, such as variants of the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2), are microglia-specific, manipulation of their expression in NIOs may reveal novel disease phenotypes [74]. Cakir et al. developed a CRISPR interference (CRISPRi)-based strategy to suppress expression of various sAD risk genes in microglia in a high-throughput manner [71]. The authors found that suppression of TREM2 or the sortilin-related receptor 1 (SORL1) was associated with increased organoid injury upon oligomeric Aβ42 treatment, indicating protective roles of TREM2 and SORL1 against amyloid-related toxicity [71]. Engineered microfluidic devices could further improve characterization of microglia behavior in response to AD-relevant pathology. Tubular NIOs with a hollow core can be constantly perfused to improve nutrient and oxygen exchange as well as deliver toxic substances to the organoid [75]. Moreover, NIOs may be used to clarify how microglia propagate tau pathology, whereas exposure of NIOs to primary or iPSC-derived peripheral immune cells may reveal microglia-immune cell interactions that contribute to AD progression [76, 77].

Blood-brain barrier organoids

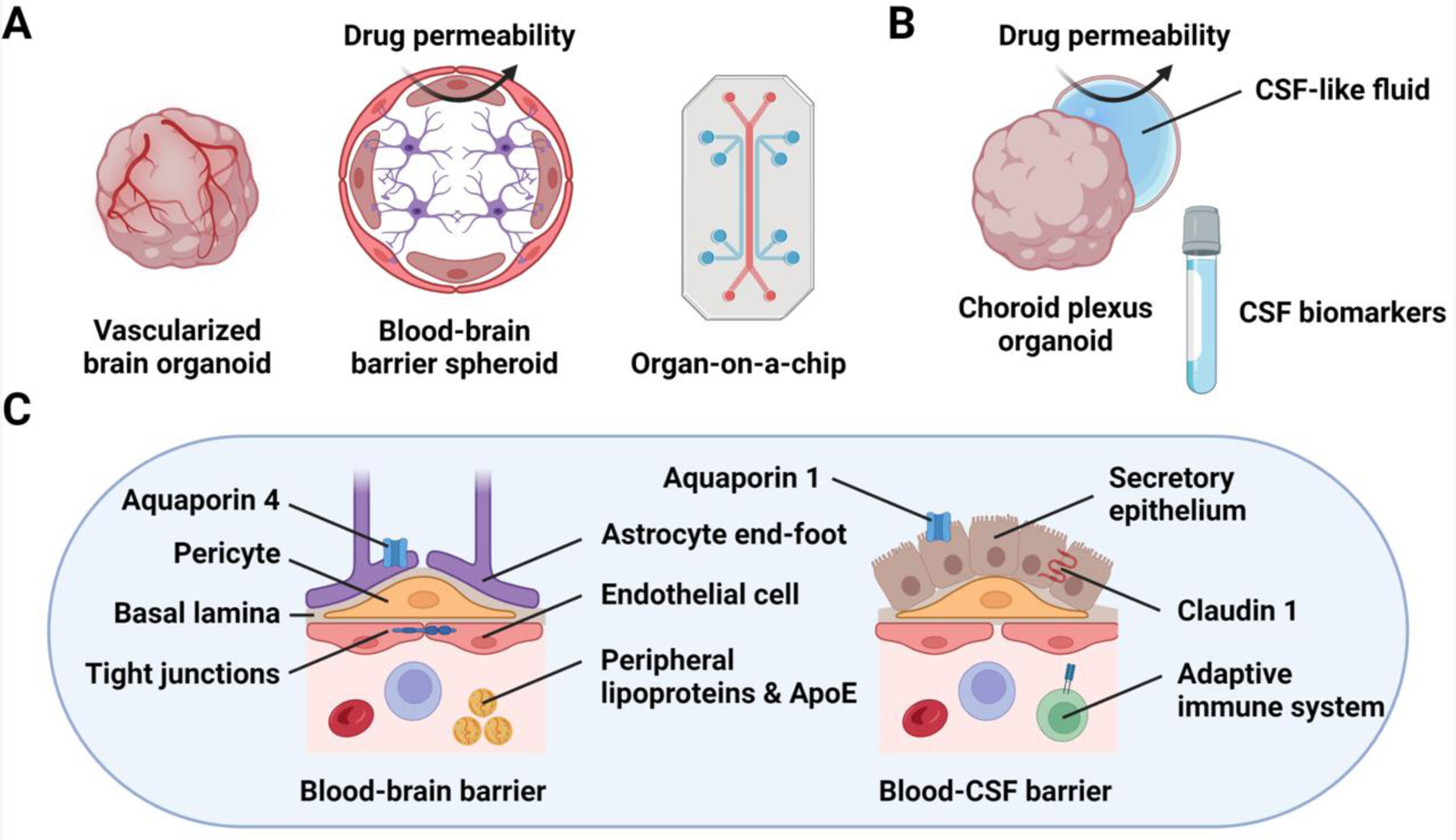

3D models of the brain vasculature include vascularized BOs, pericyte-containing BOs, in vitro BBB (iBBB), and organs-on-a-chip (see Figure 3A & 3C and Box 1) [30, 78–81]. Vascularized BOs develop perfusable CD31+ endothelial tubes while maintaining normal cortical organization, contain tight junction proteins and have higher trans-endothelial resistance than control BOs [78]. Similarly, iBBB exhibits restricted paracellular permeability and active export of small-molecule compounds [30, 79]. Therefore, BBB organoid models can be used to evaluate drug permeability across the BBB as well as determine the effects of a particular drug on the BBB integrity [30, 79]. BBB organoid models also develop AD-relevant pathology: exposure of vascularized BOs and the iBBB to Aβ disrupts tight junctions and results in amyloid accumulation reminiscent of cerebral amyloid angiopathy, respectively [30, 78]. Moreover, APOE4 iBBB accumulates more amyloid deposits than APOE3 or ApoE-depleted controls [30]. A BBB organ-on-a-chip enables further functional compartmentalization of cell types that form the neurovascular unit, whereas uncoupled perfusion of vascular and brain compartments facilitates modeling of nutrient exchange characteristic of the BBB [80, 82]. Overall, in vitro BBB models may be used to study the molecular mechanisms driving pericyte and endothelial cell dysfunction, breakdown of the selective barrier, impaired glucose metabolism, and other phenotypes relevant to AD.

Figure 3: Human organoid technology for modeling brain vascular systems.

(A) Vascularized BOs can be engineered by transcription factor-driven directed endothelial cell differentiation during BO generation. Alternatively, spheroids containing astrocytes, pericytes, and endothelial cells self-organize into distinct layers that form a blood-brain barrier (BBB)-like structure. Finally, organ-on-a-chip devices combine microfluidics with in vitro cell culture, enabling the desired layering of different BBB cell types to be achieved. (B) Differentiation of choroid plexus organoids (ChPOs) enables modeling of the blood-cerebrospinal fluid (B-CSF) barrier and the production of CSF-like fluid. Furthermore, ChPOs may be used to study the changes in CSF composition during AD progression as well as to uncover AD-relevant CSF biomarkers. (C) Organoid models of brain vascular systems recapitulate key elements of the BBB and the B-CSF barrier. For example, BBB models contain endothelial cells, pericytes, and astrocytic end-feet as well as express genes encoding tight junction and channel proteins, such as aquaporin 4 (AQP4). ChPOs contain secretory epithelium producing CSF-like fluid as well as express genes encoding tight junction proteins, such as claudin 1 (CLDN1), and proteins required for CSF secretion, such as aquaporin 1 (AQP1). Therefore, the BBB and B-CSF barrier models can be used to study various aspects of vascular dysfunction associated with AD, and explore novel directions for AD research, such as the roles of peripheral lipoproteins and ApoE as well as the adaptive immune system in AD progression.

Choroid plexus organoids

Recently developed ChPOs form a B-CSF barrier-like structure lined with secretory cuboidal epithelium that produces CSF-like fluid into enclosed cysts [83] (Figure 3B & 3C and Box 1). ChPOs express various genes encoding transporter, signaling, and junction proteins as well as proteins required for CSF secretion, such as the water transporter aquaporin 1 (AQP1) [83, 84]. Remarkably, permeability of the ChPO barrier to various drugs correlates with that of the B-CSF barrier in vivo, highlighting the potential of using ChPOs for testing drug permeability and toxic drug accumulation before proceeding to clinical trials [83]. Moreover, the CSF-like fluid produced by ChPOs contains AD-relevant factors, such as ApoE [83]. Therefore, ChPOs may be used to study how various AD risk factors affect the integrity of the B-CSF barrier as well as the composition of the CSF-like fluid. Given that peripheral ApoE4 has been shown to trigger BBB breakdown, it will be important to define the impact of peripheral ApoE4 on the B-CSF barrier as well [63]. Moreover, co-culturing ChPOs with T cells will facilitate modeling of T cell activity and dysfunction in the CSF of AD patients [64]. ChPOs may also aid identification of novel CSF biomarkers, which could both inform research directions and facilitate more accurate stratification of patients that have different types of dementia but share symptomatology and pathology similarities [10, 16, 33]. However, biomarker discovery based on the CSF-like fluid produced by ChPOs should be rigorously validated using CSF isolated from AD patients, given the limitations of in vitro CSF-like fluid production.

Organoid models of virus infection

Environmental risk factors may precipitate AD onset or accelerate its progression. BOs have been used extensively to study virus infection, including SARS-CoV-2 most recently [81, 84–86]. Viruses may preferentially infect different cell types of the brain, illustrating the need for diverse BO models to evaluate viral and other environmental risk factors for AD [84, 86]. For example, SARS-CoV-2 selectively infects ChPOs and astrocyte-enriched BOs as well as infects ApoE4 neurons and astrocytes more efficiently than their ApoE3 counterparts [84, 86]. However, it remains to be determined if there is a definitive link between SARS-CoV-2 and AD although reports supporting the idea are emerging [87]. Conversely, viruses of the Herpesviridae family have long been implicated in AD pathogenesis [88]. Infection of a neural progenitor cell-derived 3D brain tissue model with herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) induces formation of Aβ deposits, promotes astrocyte activation, and drives neuroinflammation [89]. Similarly, infection with Zika virus accelerates Aβ aggregation and tau phosphorylation in fAD BOs as well as leads to microglia and astrocyte activation in NIOs [73, 90]. These findings indicate that virus infection evokes AD-relevant pathology and warrant further investigation into the relationships between pathogenic insults, known risk factors for AD, and other effectors that may trigger AD onset or worsen its progression.

High-throughput drug screening using brain organoids

In addition to drug development applications discussed throughout this Review, BOs may also be applied for high-throughput drug screening, if BO scaling and reproducibility are optimized (Box 3). For example, engineered micropillar arrays may serve as scaffolds for efficient and highly reproducible generation of a large number of BOs suitable for drug screening [91]. Moreover, tissue clearing techniques enable high-content screening of organoid pathology by automated imaging acquisition and analysis [50]. Park et al. developed a scalable platform to evaluate accumulation of Aβ and p-tau in BOs using automated imaging in 96-well plates [50]. The authors performed a proof-of-principle screening of a panel of drugs targeting AD-relevant cellular pathways and robustly detected reduction in the Aβ and p-tau burden under most treatment conditions [50]. We anticipate that advancing automated imaging techniques will also be applied to assess AD-relevant pathology in various other organoids discussed throughout this Review, such as myelinoids to evaluate changes in the myelin volume [68].

Limitations of brain organoids for the study of Alzheimer’s disease

Although the exponential growth of the BO field has led to substantial improvements in BO differentiation and characterization protocols in recent years, important limitations relevant to disease modeling remain. BOs are primarily a neurodevelopmental model that recapitulates early human brain development rather than the aging brain when AD manifests. Therefore, the extent to which BOs can be used to model age-related neurodegeneration is not self-evident and requires rigorous validation of the observed phenotypes using alternative approaches. These include immunohistochemical and transcriptomic analysis of primary human brain tissue as well as experiments in vivo. Moreover, development of various techniques to model age-relevant events, such as BBB leakage by serum exposure as discussed earlier, is likely to exacerbate neurodegenerative phenotypes and strengthen the relevance of using BOs for the study of AD [62]. BOs are also a reductionist model, resembling only certain aspects of the brain cytoarchitecture and function; for example, neural organoids largely lack microglia, myelination, and the BBB. Although it remains challenging to introduce these critical components into a single BO model, specialized BOs discussed throughout this Review—myelinoids, NIOs, BBB organoids, and ChPOs—offer a versatile platform for modeling distinct AD-relevant phenotypes. Furthermore, the lack of vascularization in BOs contributes to internal hypoxia and cellular stress that lead to necrosis and impaired cell subtype specification [92]. Oxygen and nutrient exchange may be improved by using spinning bioreactors, engineering organoids-on-a-chip, introducing vascular cells, or simply slicing BOs (Box 3) [8, 78, 93–95]. Finally, organoid-to-organoid and batch-to-batch variation is a major issue that affects reproducibility of BO studies and is a barrier to high-throughput applications, such as drug screening. Variation can be mitigated by selecting guided BO differentiation approaches over those of unguided differentiation (Box 3), generating BOs from a defined number of iPSCs using microscaffolds, and including a quality control step to ensure correct neuroectoderm organization during differentiation [39, 91]. Similarly, careful assessment and reporting of the BO differentiation stage are also required to obtain reproducible results. For example, studying ApoE-related phenotypes requires sufficient BO maturation to establish a prominent astrocyte compartment, given that astrocytes are the primary source of secreted ApoE [21, 52]. Likewise, optimization of NIO differentiation protocols is required to ensure consistent microglia density across different batches of NIOs [73].

Concluding remarks and future directions

Rapidly advancing human BO technology enables modeling of complex cell-cell interactions of the human brain using easily obtainable and genetically modifiable in vitro models. BOs can be engineered to contain the desired combinations of genetic risk variants and cell types, so that scientific hypotheses could be addressed in the most direct manner (see Outstanding Questions). Unique advantages of BO models discussed throughout this Review could be integrated to derive organoids that recapitulate distinct cellular phenotypes associated with AD. For example, integration of microglia into myelinoids would enable modeling of microglia-mediated recycling of myelin debris upon myelin breakdown as well as how re-myelination could be invigorated by therapeutic intervention in AD patients. Novel approaches to promote BO maturation and specification will also facilitate the development of more complex BO models. For example, slicing BOs resolves diffusion constraints and allows formation of an expanded cortical plate and even nerve tracts, whereas integration of a Sonic hedgehog signaling center promotes topographical BO specification [94–96]. The ability to assemble heterotypic regionally-patterned BOs into assembloids will enable modeling of the interactions between distal brain regions during AD progression; for example, cortical-hippocampal assembloids could be used to study tau propagation, mimicking the in vivo pattern of tau spreading from the hippocampus to the neocortex, as well as clarify the roles of ApoE4 and microglia in tau propagation [10, 15, 25, 76]. Development of neural-vascular assembloids could further advance BO vascularization efforts and facilitate the study of the neurovascular unit [97]. Chimeric brain organoids, where only a specific cell type expresses a disease risk variant (reminiscent of conditional transgenic mouse models), may be used to define the cell type specificity in mediating the effects of genetic risk variants for AD [30, 98]. Advances in bioengineering of biomimetic scaffolds and organs-on-chip may enable BO perfusion as well as assembly of multi-organ chips to uncover the effectors originating from distal organs, such as gut microbiota-derived metabolites, that contribute to AD progression [99, 100]. Finally, BO transplantation in vivo will accelerate the efforts to promote BO maturation and functionalization, including circuit integration, vascularization, and microglia infiltration [101, 102]. We envision that BO transplantation models will serve as drug development platforms that combine the advantages of complex in vivo environment with the advantages of using human cell-derived BO models that have the potential to reveal human-specific molecular mechanisms governing AD progression, thus accelerating therapeutic development for AD.

Outstanding Questions.

How does the interplay between neurons and glial cells drive neuroinflammation in brain organoid (BO) models of Alzheimer’s disease (AD)?

What are the key events that promote microglial activation leading to neuroinflammation in AD BOs?

How does a multitude of genetic and environmental risk factors for AD interact to drive disease progression in BOs?

How do common and rare APOE variants affect myelin health and integrity in myelinoids?

How do various genetic and environmental risk factors for AD affect the blood-brain barrier integrity in brain vasculature-containing organoids?

How do APOE variants affect the integrity of the choroid plexus as well as the composition of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)-like fluid in choroid plexus organoids?

Can choroid plexus organoids producing CSF-like fluid be used for biomarker discovery?

How can aging-associated phenotypes be induced in BOs to study the impact of aging on AD pathogenesis?

What are the roles of the adaptive immune system in AD pathogenesis, and how can these roles be evaluated experimentally using the organoid technology?

Highlights.

Induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology has enabled modeling of human diseases using patient-derived cells with relevant genetic background

iPSC-derived 3D brain organoids self-organize and resemble the cytoarchitecture of in vivo brain tissue, making them attractive tools for modeling Alzheimer’s disease (AD)

Brain organoids contain multiple human brain cell types, enabling the study of cell-cell interactions that drive AD progression

Human iPSC-derived brain organoids may reveal human-specific disease phenotypes and molecular mechanisms that are not recapitulated in animal models

Clinician’s Corner.

The etiology of sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is poorly understood, whereas genome-wide association studies and high-throughput profiling of the human brain have revealed immense complexity of AD pathogenesis that involves multiple cell types and extensive cell-cell interactions.

Human organoid technology provides sophisticated self-organizing human brain-like tissues for modeling these cell-cell interactions in the context of AD. Moreover, the organoid technology overcomes the limitations associated with using rodent models that exhibit substantial species divergence in their cellular programs compared to those of humans.

Brain organoid technology can be scaled to develop high-content screening assays for drug discovery using engineered microarrays and automated imaging platforms to evaluate disease pathology and response to therapeutic intervention.

Modeling viral infection using brain organoids may rapidly inform research and medical community of how novel viruses, including SARS-CoV-2, infect human brain cell types and precipitate secondary pathology, including neurodegeneration.

Organoids and organs-on-a-chip engineered to contain brain vascular systems can be used to quantitatively evaluate drug permeability and toxic drug accumulation in brain tissues before initiating clinical trials. Substantial species divergence between mouse and human brain vasculature necessitates complementary evaluation of drug pharmacokinetics in human iPSC-based cellular models.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Louise and Herbert Horvitz for their generosity and forethought. This work was supported by the National Institute of Aging of the National Institutes of Health R01 AG056305, RF1 AG061794, R01 AG072291, and RF1 AG079307, the Briskin Research Innovation Award, the Christopher Family Endowed Innovation Fund, and the Sidell Kagan Foundation to Y.S. J.C. is a predoctoral scholar in the Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine Research Training Program of the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM). Figures 1, 2, and 3 were created with BioRender.com

Glossary

- Astrogliosis

astrocyte activation and proliferation in response to a damaging insult or brain injury.

- Cerebral amyloid angiopathy

a medical condition characterized by amyloid accumulation on the walls of the brain vasculature.

- Choroid plexus

a brain tissue comprised of a network of blood vessels and secretory epithelium that produces cerebrospinal fluid.

- CRISPR interference

a molecular biology technique to suppress gene expression using the CRISPR/Cas9 platform (generally performed in a high-throughput manner).

- Genome-wide association studies

a genetics methodology to identify genetic alterations that are linked to disease phenotypes.

- Glutamatergic neurons

excitatory neurons that use glutamate as a neurotransmitter.

- High-content screening

a methodology to identify cellular and sub-cellular phenotypes in a high-throughput manner.

- Hyperexcitability

increased probability of neuronal activation upon stimulation.

- Microgliosis

inflammatory activation of microglia in response to a damaging insult or brain injury.

- Neuroectoderm

a type of tissue in a developing embryo that gives rises to the central nervous system.

- Neuroinflammation

chronic activation of the innate immune system of the brain.

- Nodes of Ranvier

intermittent areas of a myelinated axon that lack myelin and promote saltatory conduction of action potentials.

- Organ-on-a-chip

a microfluidics device mimicking in vivo tissue architecture.

- Oscillatory bursts

rhythmic electrical activity of neuronal networks.

- Positron emission tomography

a non-invasive imaging methodology to detect tissue metabolic activity.

- Radial glia

progenitor cells of the developing nervous system that give rise to neurons and macroglia.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Competing Interests

G.B. is an employee of SciNeuro Pharmaceuticals.

References

- 1.Shi Y et al. (2017) Induced pluripotent stem cell technology: a decade of progress. Nat Rev Drug Discov 16 (2), 115–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takahashi K et al. (2007) Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell 131 (5), 861–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu J et al. (2007) Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science 318 (5858), 1917–1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li L et al. (2018) Modeling neurological diseases using iPSC-derived neural cells: iPSC modeling of neurological diseases. Cell Tissue Res 371 (1), 143–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vadodaria KC et al. (2020) Modeling Brain Disorders Using Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 12 (6), a035659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lancaster MA et al. (2013) Cerebral organoids model human brain development and microcephaly. Nature 501 (7467), 373–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pasca AM et al. (2015) Functional cortical neurons and astrocytes from human pluripotent stem cells in 3D culture. Nat Methods 12 (7), 671–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qian X et al. (2016) Brain-Region-Specific Organoids Using Mini-bioreactors for Modeling ZIKV Exposure. Cell 165 (5), 1238–1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qian X et al. (2019) Brain organoids: advances, applications and challenges. Development 146 (8), dev166074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knopman DS et al. (2021) Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers 7 (1), 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Selkoe DJ and Hardy J (2016) The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol Med 8 (6), 595–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunn B et al. (2021) Approval of Aducanumab for Alzheimer Disease-The FDA’s Perspective. JAMA Intern Med 181 (10), 1276–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Dyck CH et al. (2023) Lecanemab in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med 388 (1), 9–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Larkin HD (2023) Lecanemab Gains FDA Approval for Early Alzheimer Disease. JAMA 329 (5), 363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Kant R et al. (2020) Amyloid-beta-independent regulators of tau pathology in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 21 (1), 21–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Long JM and Holtzman DM (2019) Alzheimer Disease: An Update on Pathobiology and Treatment Strategies. Cell 179 (2), 312–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Strooper B and Karran E (2016) The Cellular Phase of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell 164 (4), 603–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martens YA et al. (2022) ApoE Cascade Hypothesis in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Neuron 110 (8), 1304–1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murdock MH and Tsai LH (2023) Insights into Alzheimer’s disease from single-cell genomic approaches. Nat Neurosci 26, 181–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wightman DP et al. (2021) A genome-wide association study with 1,126,563 individuals identifies new risk loci for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet 53 (9), 1276–1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamazaki Y et al. (2019) Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: pathobiology and targeting strategies. Nat Rev Neurol 15 (9), 501–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang AC et al. (2022) A human brain vascular atlas reveals diverse mediators of Alzheimer’s risk. Nature 603 (7903), 885–892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bartzokis G (2011) Alzheimer’s disease as homeostatic responses to age-related myelin breakdown. Neurobiol Aging 32 (8), 1341–1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kinney JW et al. (2018) Inflammation as a central mechanism in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dementia: Translational Research Clinical Interventions 4, 575–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koutsodendris N et al. (2023) Neuronal APOE4 removal protects against tau-mediated gliosis, neurodegeneration and myelin deficits. Nature Aging, 1–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Habib N et al. (2020) Disease-associated astrocytes in Alzheimer’s disease and aging. Nat Neurosci 23 (6), 701–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Depp C et al. (2021) Ageing-associated myelin dysfunction drives amyloid deposition in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Preprint at BioRxiv

- 28.d’Errico P et al. (2022) Microglia contribute to the propagation of Abeta into unaffected brain tissue. Nat Neurosci 25 (1), 20–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fame RM and Lehtinen MK (2020) Emergence and Developmental Roles of the Cerebrospinal Fluid System. Dev Cell 52 (3), 261–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blanchard JW et al. (2020) Reconstruction of the human blood-brain barrier in vitro reveals a pathogenic mechanism of APOE4 in pericytes. Nat Med 26 (6), 952–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cruz Hernandez JC et al. (2019) Neutrophil adhesion in brain capillaries reduces cortical blood flow and impairs memory function in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Nat Neurosci 22 (3), 413–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nortley R et al. (2019) Amyloid beta oligomers constrict human capillaries in Alzheimer’s disease via signaling to pericytes. Science 365 (6450), eaav9518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.del Campo M et al. (2022) CSF proteome profiling across the Alzheimer’s disease spectrum reflects the multifactorial nature of the disease and identifies specific biomarker panels. Nature Aging 2, 1040–1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fang R et al. (2022) Conservation and divergence of cortical cell organization in human and mouse revealed by MERFISH. Science 377 (6601), 56–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hodge RD et al. (2019) Conserved cell types with divergent features in human versus mouse cortex. Nature 573 (7772), 61–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Geirsdottir L et al. (2019) Cross-Species Single-Cell Analysis Reveals Divergence of the Primate Microglia Program. Cell 179 (7), 1609–1622 e16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li J et al. (2021) Conservation and divergence of vulnerability and responses to stressors between human and mouse astrocytes. Nat Commun 12 (1), 3958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gargareta VI et al. (2022) Conservation and divergence of myelin proteome and oligodendrocyte transcriptome profiles between humans and mice. Elife 11, e77019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lancaster MA and Knoblich JA (2014) Generation of cerebral organoids from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Protoc 9 (10), 2329–2340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bubnys A and Tsai LH (2022) Harnessing cerebral organoids for Alzheimer’s disease research. Curr Opin Neurobiol 72, 120–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Orr ME et al. (2017) A Brief Overview of Tauopathy: Causes, Consequences, and Therapeutic Strategies. Trends Pharmacol Sci 38 (7), 637–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bowles KR et al. (2021) ELAVL4, splicing, and glutamatergic dysfunction precede neuron loss in MAPT mutation cerebral organoids. Cell 184 (17), 4547–4563 e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glasauer SMK et al. (2022) Human tau mutations in cerebral organoids induce a progressive dyshomeostasis of cholesterol. Stem Cell Reports 17 (9), 2127–2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pavoni S et al. (2018) Small-molecule induction of Abeta-42 peptide production in human cerebral organoids to model Alzheimer’s disease associated phenotypes. PLoS One 13 (12), e0209150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shimada H et al. (2022) A next-generation iPSC-derived forebrain organoid model of tauopathy with tau fibrils by AAV-mediated gene transfer. Cell Rep Methods 2 (9), 100289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Busche MA et al. (2019) Tau impairs neural circuits, dominating amyloid-beta effects, in Alzheimer models in vivo. Nat Neurosci 22 (1), 57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Busche MA and Hyman BT (2020) Synergy between amyloid-beta and tau in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Neurosci 23 (10), 1183–1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Capano LS et al. (2022) Recapitulation of endogenous 4R tau expression and formation of insoluble tau in directly reprogrammed human neurons. Cell Stem Cell 29 (6), 918–932 e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rickner HD et al. (2022) Single cell transcriptomic profiling of a neuron-astrocyte assembloid tauopathy model. Nat Commun 13 (1), 6275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park JC et al. (2021) A logical network-based drug-screening platform for Alzheimer’s disease representing pathological features of human brain organoids. Nat Commun 12 (1), 280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lin YT et al. (2018) APOE4 Causes Widespread Molecular and Cellular Alterations Associated with Alzheimer’s Disease Phenotypes in Human iPSC-Derived Brain Cell Types. Neuron 98 (6), 1141–1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao J et al. (2022) APOE deficiency impacts neural differentiation and cholesterol biosynthesis in human iPSC-derived cerebral organoids. Preprint at BioRxiv [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Zhao J et al. (2020) APOE4 exacerbates synapse loss and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease patient iPSC-derived cerebral organoids. Nat Commun 11 (1), 5540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Choi H et al. (2020) Acetylation changes tau interactome to degrade tau in Alzheimer’s disease animal and organoid models. Aging Cell 19 (1), e13081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Congdon EE and Sigurdsson EM (2018) Tau-targeting therapies for Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol 14 (7), 399–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gallardo G et al. (2019) Targeting tauopathy with engineered tau-degrading intrabodies. Mol Neurodegener 14 (1), 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huynh TV et al. (2017) Age-Dependent Effects of apoE Reduction Using Antisense Oligonucleotides in a Model of beta-amyloidosis. Neuron 96 (5), 1013–1023 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xiong M et al. (2021) APOE immunotherapy reduces cerebral amyloid angiopathy and amyloid plaques while improving cerebrovascular function. Sci Transl Med 13 (581), eabd7522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hernandez D et al. (2022) Culture Variabilities of Human iPSC-Derived Cerebral Organoids Are a Major Issue for the Modelling of Phenotypes Observed in Alzheimer’s Disease. Stem Cell Rev Rep 18 (2), 718–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Montagne A et al. (2015) Blood-brain barrier breakdown in the aging human hippocampus. Neuron 85 (2), 296–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sweeney MD et al. (2018) Blood-brain barrier breakdown in Alzheimer disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Nat Rev Neurol 14 (3), 133–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen X et al. (2021) Modeling Sporadic Alzheimer’s Disease in Human Brain Organoids under Serum Exposure. Adv Sci (Weinh) 8 (18), e2101462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu CC et al. (2022) Peripheral apoE4 enhances Alzheimer’s pathology and impairs cognition by compromising cerebrovascular function. Nat Neurosci 25 (8), 1020–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gate D et al. (2020) Clonally expanded CD8 T cells patrol the cerebrospinal fluid in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 577 (7790), 399–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kim H et al. (2019) Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Cerebral Organoids Reveal Human Oligodendrogenesis with Dorsal and Ventral Origins. Stem Cell Reports 12 (5), 890–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Madhavan M et al. (2018) Induction of myelinating oligodendrocytes in human cortical spheroids. Nat Methods 15 (9), 700–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Marton RM et al. (2019) Differentiation and maturation of oligodendrocytes in human three-dimensional neural cultures. Nat Neurosci 22 (3), 484–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.James OG et al. (2021) iPSC-derived myelinoids to study myelin biology of humans. Dev Cell 56 (9), 1346–1358 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Blanchard JW et al. (2022) APOE4 impairs myelination via cholesterol dysregulation in oligodendrocytes. Nature 611 (7937), 769–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Abud EM et al. (2017) iPSC-Derived Human Microglia-like Cells to Study Neurological Diseases. Neuron 94 (2), 278–293 e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cakir B et al. (2022) Expression of the transcription factor PU.1 induces the generation of microglia-like cells in human cortical organoids. Nat Commun 13 (1), 430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Popova G et al. (2021) Human microglia states are conserved across experimental models and regulate neural stem cell responses in chimeric organoids. Cell Stem Cell 28 (12), 2153–2166 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Xu R et al. (2021) Developing human pluripotent stem cell-based cerebral organoids with a controllable microglia ratio for modeling brain development and pathology. Stem Cell Reports 16 (8), 1923–1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ulrich JD et al. (2017) Elucidating the Role of TREM2 in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuron 94 (2), 237–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ao Z et al. (2021) Tubular human brain organoids to model microglia-mediated neuroinflammation. Lab Chip 21 (14), 2751–2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Asai H et al. (2015) Depletion of microglia and inhibition of exosome synthesis halt tau propagation. Nat Neurosci 18 (11), 1584–1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chen X et al. (2023) Microglia-mediated T cell infiltration drives neurodegeneration in tauopathy. Nature 615 (7953), 668–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cakir B et al. (2019) Engineering of human brain organoids with a functional vascular-like system. Nat Methods 16 (11), 1169–1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cho CF et al. (2017) Blood-brain-barrier spheroids as an in vitro screening platform for brain-penetrating agents. Nat Commun 8 (1), 15623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Maoz BM et al. (2018) A linked organ-on-chip model of the human neurovascular unit reveals the metabolic coupling of endothelial and neuronal cells. Nat Biotechnol 36 (9), 865–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang L et al. (2021) A human three-dimensional neural-perivascular ‘assembloid’ promotes astrocytic development and enables modeling of SARS-CoV-2 neuropathology. Nat Med 27 (9), 1600–1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Oddo A et al. (2019) Advances in Microfluidic Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) Models. Trends Biotechnol 37 (12), 1295–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pellegrini L et al. (2020) Human CNS barrier-forming organoids with cerebrospinal fluid production. Science 369 (6500), eaaz5626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jacob F et al. (2020) Human Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Neural Cells and Brain Organoids Reveal SARS-CoV-2 Neurotropism Predominates in Choroid Plexus Epithelium. Cell Stem Cell 27 (6), 937–950 e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sun G et al. (2020) Modeling Human Cytomegalovirus-Induced Microcephaly in Human iPSC-Derived Brain Organoids. Cell Rep Med 1 (1), 100002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wang C et al. (2021) ApoE-Isoform-Dependent SARS-CoV-2 Neurotropism and Cellular Response. Cell Stem Cell 28 (2), 331–342 e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Shen W-B et al. (2022) SARS-CoV-2 invades cognitive centers of the brain and induces Alzheimer’s-like neuropathology. Preprint at BioRxiv

- 88.Readhead B et al. (2018) Multiscale Analysis of Independent Alzheimer’s Cohorts Finds Disruption of Molecular, Genetic, and Clinical Networks by Human Herpesvirus. Neuron 99 (1), 64–82 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cairns DM et al. (2020) A 3D human brain-like tissue model of herpes-induced Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Adv 6 (19), eaay8828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lee SE et al. (2022) Zika virus infection accelerates Alzheimer’s disease phenotypes in brain organoids. Cell Death Discov 8 (1), 153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhu Y et al. (2017) In situ generation of human brain organoids on a micropillar array. Lab Chip 17 (17), 2941–2950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bhaduri A et al. (2020) Cell stress in cortical organoids impairs molecular subtype specification. Nature 578 (7793), 142–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cho AN et al. (2021) Microfluidic device with brain extracellular matrix promotes structural and functional maturation of human brain organoids. Nat Commun 12 (1), 4730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Giandomenico SL et al. (2019) Cerebral organoids at the air-liquid interface generate diverse nerve tracts with functional output. Nat Neurosci 22 (4), 669–679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Qian X et al. (2020) Sliced Human Cortical Organoids for Modeling Distinct Cortical Layer Formation. Cell Stem Cell 26 (5), 766–781 e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cederquist GY et al. (2019) Specification of positional identity in forebrain organoids. Nat Biotechnol 37 (4), 436–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sun XY et al. (2022) Generation of vascularized brain organoids to study neurovascular interactions. Elife 11, e76707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Huang S et al. (2022) Chimeric cerebral organoids reveal the essentials of neuronal and astrocytic APOE4 for Alzheimer’s tau pathology. Signal Transduct Target Ther 7 (1), 176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Seo DO et al. (2023) ApoE isoform- and microbiota-dependent progression of neurodegeneration in a mouse model of tauopathy. Science 379 (6628), eadd1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ronaldson-Bouchard K et al. (2022) A multi-organ chip with matured tissue niches linked by vascular flow. Nat Biomed Eng 6 (4), 351–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Revah O et al. (2022) Maturation and circuit integration of transplanted human cortical organoids. Nature 610 (7931), 319–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mansour AA et al. (2018) An in vivo model of functional and vascularized human brain organoids. Nat Biotechnol 36 (5), 432–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Chiaradia I and Lancaster MA (2020) Brain organoids for the study of human neurobiology at the interface of in vitro and in vivo. Nat Neurosci 23 (12), 1496–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Marton RM and Pasca SP (2020) Organoid and Assembloid Technologies for Investigating Cellular Crosstalk in Human Brain Development and Disease. Trends Cell Biol 30 (2), 133–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Di Lullo E and Kriegstein AR (2017) The use of brain organoids to investigate neural development and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 18 (10), 573–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sloan SA et al. (2017) Human Astrocyte Maturation Captured in 3D Cerebral Cortical Spheroids Derived from Pluripotent Stem Cells. Neuron 95 (4), 779–790 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ormel PR et al. (2018) Microglia innately develop within cerebral organoids. Nat Commun 9 (1), 4167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Babiloni C et al. (2020) What electrophysiology tells us about Alzheimer’s disease: a window into the synchronization and connectivity of brain neurons. Neurobiol Aging 85, 58–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Trujillo CA et al. (2019) Complex Oscillatory Waves Emerging from Cortical Organoids Model Early Human Brain Network Development. Cell Stem Cell 25 (4), 558–569 e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Fagerlund I et al. (2021) Microglia-like Cells Promote Neuronal Functions in Cerebral Organoids. Cells 11 (1), 124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sabate-Soler S et al. (2022) Microglia integration into human midbrain organoids leads to increased neuronal maturation and functionality. Glia 70 (7), 1267–1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Vossel KA et al. (2017) Epileptic activity in Alzheimer’s disease: causes and clinical relevance. Lancet Neurol 16 (4), 311–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ghatak S et al. (2019) Mechanisms of hyperexcitability in Alzheimer’s disease hiPSC-derived neurons and cerebral organoids vs isogenic controls. Elife 8, e50333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yin J and VanDongen AM (2021) Enhanced Neuronal Activity and Asynchronous Calcium Transients Revealed in a 3D Organoid Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 7 (1), 254–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Samarasinghe RA et al. (2021) Identification of neural oscillations and epileptiform changes in human brain organoids. Nat Neurosci 24 (10), 1488–1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sharf T et al. (2022) Functional neuronal circuitry and oscillatory dynamics in human brain organoids. Nat Commun 13 (1), 4403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Huang Q et al. (2022) Shell microelectrode arrays (MEAs) for brain organoids. Sci Adv 8 (33), eabq5031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Le Floch P et al. (2022) Stretchable Mesh Nanoelectronics for 3D Single-Cell Chronic Electrophysiology from Developing Brain Organoids. Adv Mater 34 (11), e2106829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Rosebrock D et al. (2022) Enhanced cortical neural stem cell identity through short SMAD and WNT inhibition in human cerebral organoids facilitates emergence of outer radial glial cells. Nat Cell Biol 24 (6), 981–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Velasco S et al. (2019) Individual brain organoids reproducibly form cell diversity of the human cerebral cortex. Nature 570 (7762), 523–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Yoon SJ et al. (2019) Reliability of human cortical organoid generation. Nat Methods 16 (1), 75–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Baik SH et al. (2019) A Breakdown in Metabolic Reprogramming Causes Microglia Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell Metab 30 (3), 493–507 e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Traxler L et al. (2022) Warburg-like metabolic transformation underlies neuronal degeneration in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Metab 34 (9), 1248–1263 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]