Highlights

-

•

There is ongoing debate regarding addiction criteria of problematic sex use.

-

•

Impaired control and craving are highly prevalent among problematic sex users.

-

•

Impaired control and intensity of craving are predictive to problematic sex use.

-

•

Craving for sex is associated to unregulated use, frequency and quantity of use.

-

•

Anti-craving interventions could be effective in improving clinical outcomes.

Keywords: Problematic pornography use, Cybersex, Craving, Loss of control, DSM-5 criteria, Systematic review

Introduction

Despite similarities between compulsive sexual disorder and substance use disorder, the issue whether problematic sexual behavior should be viewed within an addiction framework continues to be a subject of debate with no consensus regarding its conceptualization and diagnosis criteria. Examining the presence of addiction criteria among clinical and no clinical samples in the existing literature could permit to ascertain clinical validity of sex addiction diagnosis and support its overlapping feature with other addictive disorders. The aim of this systematic review was to examine this issue by assessing DSM-5 criteria of substance use disorder among individuals engaged in problematic sexual activity. Methods: Using PRISMA criteria, three databases were comprehensively searched up to April 2022, in order to identify all candidate studies based on broad key words. Resulting studies were then selected if they examined problematic sexual behavior within the framework of DSM-5 addiction criteria. Results: Twenty articles matched the selection criteria and were included in this review. DSM-5 criteria of addictive disorders were found to be highly prevalent among problematic sex users, particularly craving, loss of control over sex use, and negative consequences related to sexual behavior. Exposition to sexual cues was also shown to trigger craving, with an association to problematic use and symptom severity. Conclusions: More studies should been done to assess homogeneously according to the DSM-5 criteria the addiction-like features of problematic sexual behaviors in clinical and no-clinical populations. Furthermore, this work argues for the need of further research to examine the extent to which anti-craving interventions could be effective in improving clinical outcomes.

1. Introduction

Problematic sexual behavior, also known as hypersexual disorder (Kafka, 2010) or compulsive sexual behavior in the International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11), is characterized by repetitive and intense preoccupations with sexual fantasies, urges, and behaviors that are distressing to the individual and/or result in psychosocial impairment. Existing prevalence rates range from 3% to 6% (Lewczuk et al., 2022; Bőthe et al., 2020, Briken et al., 2022), including various types of problematic behaviors, while recent data in the United States found higher overall prevalence of compulsive sexual behavior at 8.6% (Dickenson et al., 2018). This prevalence has been found to be 3 to 5 times more common in men than women (Karila et al., 2014), higher in late adolescence and entering adulthood (Benhaiem, 2009), as well as in specific populations such as sexual minorities (Gleason et al., 2021, Borgogna, 2022), sexual abuse victims and offenders (Marshall & Marshall, 2006), people living with HIV (Karila et al., 2014). Furthermore, the development of internet support considerably increased the availability and accessibility of sexual rewards leading to a large variety of activities and content available with the associated risk of increasing the development of dysregulated sexual behaviors (Wéry & Billieux, 2017).

Many approaches have been debated regarding the classification of problematic sexual behaviors that have been described in terms of sexual compulsivity, sexual impulsivity and sexual addiction. Conceptualized within the framework of problematic hypersexuality, compulsive sexual behavior disorder (CSBD) was recently included in the ICD-11 as an impulse control disorder and refers to persistent, repetitive engagement in sexual behaviors that results in impairment in one's life in addition to failed attempts to reduce or stop such behaviors. Hypersexual Disorder (HD) criteria, proposed by Kafka in 2010 under the Sexual Disorders section for DSM-5 consideration, were close to those of CSBD, except for the emotion/stress-regulation-related features. On the other hand, a wide array of evidence showed overlapping features between these disorders and substance and/or behavioral addictions, leading some authors to consider CSBD as an addiction similar to gambling disorder, which was included as a behavioral addiction in DSM-5 and ICD-11. Examples of clinical similarities include sexual compulsivity, feelings of loss of control, engaging in sexual behaviors despite negative consequences, craving for sex and distress caused by the sexual behavior (Carnes et al., 2014, Starcke et al., 2018). Besides clinical considerations, several studies have also suggested similarities between substance and behavioral addictions including neurological, biological and genetic vulnerabilities (Frascella et al., 2010, Kraus et al., 2016). In line with these considerations, the issue whether CSBD should be viewed as an impulse control disorder, as a compulsive disorder or within an addiction framework continues to be a subject of debate (Grant et al., 2010, Kor et al., 2013, Reid, 2016) with no consensus regarding its conceptualization and diagnosis criteria. The addiction model of CSBD postulates that sexual behavior may generate gratification and reward, leading to craving and persistent engagement in behavior despite adverse consequences, experience of reduced inhibition with the concomitant development of withdrawal and tolerance symptoms that tend to increase quantity and frequency of use. In order to support this model and further investigate the prevalence and applicability of specific addiction diagnostic criteria within the CSBD population, various diagnosis criteria have been proposed (Wéry and Billieux, 2017, Wéry et al., 2016): continuation of a sexual behavior despite problems or adverse consequences, a recurrent pattern of preoccupation or engagement in sexual urges, impulses or behaviors, loss of control, excessive time dedicated to sexual behavior. Considering DSM criteria of Substance Use Disorders, some authors also included two items related to physiological dependence (tolerance, withdrawal) and craving as common clinical features of problematic sexual behaviors. Craving, that has been added in the DSM-5 as a diagnostic criterion for substance use disorders, has been recently identified as a central feature of addictions with a key role in predicting relapse and clinical outcomes (Hormes, 2017). It can be defined as a transient but intense urge to engage in a behavior that fluctuates overtime and may be elicited by behavioral-related cue-exposure (Starcke et al., 2018). In accordance to this model, high prevalence rate of items related to loss of control, tolerance and withdrawal were found in clinical sample (Carnes et al., 2014), while other studies considered cue-reactivity and craving (Laier et al., 2014, Weinstein et al., 2015). Among young adult men, craving for pornography correlated positively with psychological/psychiatric symptoms, sexual compulsivity, and severity of cybersex addiction (Laier et al., 2014, Weinstein et al., 2015), and thereby could be relevant for the assessment of CSBD. Examining the presence of these criteria among clinical and no clinical samples in the existing literature could permit to ascertain clinical validity of sex addiction diagnosis and support its overlapping feature with other addictive disorders. The aim of this systematic review was to provide an overview of the clinical relevance of applying addiction criteria to problematic sexual behavior, considering DSM-5 criteria for substance use disorder. Our research focused on the main core features of addiction according to DSM-5 that are shared by substance-related and behavioral addictions which are: loss of control (continuation of a sexual behavior despite adverse consequences, excessive time dedicated to sexual behavior, unsuccessful efforts to reduce or stop the behavior), craving to perform the behavior and the development of physiological dependence (withdrawal and tolerance).

2 Methods

The study involved a systematic review of the literature based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., 2021).

2.1. Search strategy

This review was based on the following databases: MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Embase. The search was performed for all years up to April 2022.

The following search terms were used: (“hypersexual disorder” OR “sex addict” OR “sexual addiction” OR “sexual compulsion” OR “compulsive sexual behavior disorder” OR “sexual impulsivity” OR “paraphilia related disorder” OR “excessive sexual disorder” OR “pornography” OR “internet pornography addiction” OR “cybersex” OR “problematic pornography use”) AND (“assessment” OR “craving” OR “increased time spent” OR “unsuccessful efforts to reduce or stop use” OR “tolerance” OR “withdrawal” OR “negative consequences” OR “addiction diagnostic criteria” OR “out of control” OR “addiction” OR “loss of control” OR “diagnostic criteria”) NOT (“case report” OR “case study”).

Studies published in English-language peer-reviewed journals concerning participants with problematic sexual behavior, seeking or not-seeking treatment, were selected. Studies were excluded if they were based on animal models, or if they were case report studies or limited to conference abstracts, dissertations, book chapters or incomplete articles.

2.2. Study selection

Two authors independently examined all titles and abstracts. Relevant articles were obtained in full-text and assessed for inclusion criteria separately by the two reviewers based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria previously mentioned. Disagreements were resolved via discussion of each article for which conformity to inclusion and exclusion criteria were uncertain and a consensus was reached. Studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. The reference lists of major papers were also manually screened in order to ensure comprehensiveness of the review. All selected studies were read in full to confirm inclusion criteria, study type and study population.

2.3. Risk of bias assessment

Two reviewers (NP and MF) assessed the quality of data in the included studies using the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies (S2C) from National Institutes of Health. This tool is comprised of 14 questions with responses to each being “yes”, “no”, or “other” (not applicable, NA or nor reported, NR). We rated the overall quality of each included study as “good”, “fair” or “poor”.

2.4. Collecting data

Sample characteristics (including socio-demographic data, type of sexual practices, in treatment or not), study design and methods of assessment of sexual addiction and addiction diagnostic criteria were extracted. Table 1 presents data items extracted from the selected studies.

Table 1.

Data items extracted from the selected studies.

| Evaluation criteria | Variables collected |

|---|---|

| Study characteristics | Retrospective, prospective or cross-sectional observational studies.(Or) experimental studies: context of withdrawal and exposure to stimuli related to problematic behavior.(Or) systematic review or meta-analysis |

| Sample characteristics | General or student population or having a use of pornography or in research or receiving care for problematic use of sex. Socio-demographic characteristics (age, sex), type of sexual practices |

| Evaluation methods | DSM criteria for addictive-related disorders and/or evaluation scales for the different variables of interest such as problematic sexual practice (cybersex/pornography), addictive behavior, craving and reactivity to stimuli. |

| Results | According to the diagnostic criteria studied (craving, loss of control, damages, withdrawal, tolerance) |

3. Results

3.1. Study selection

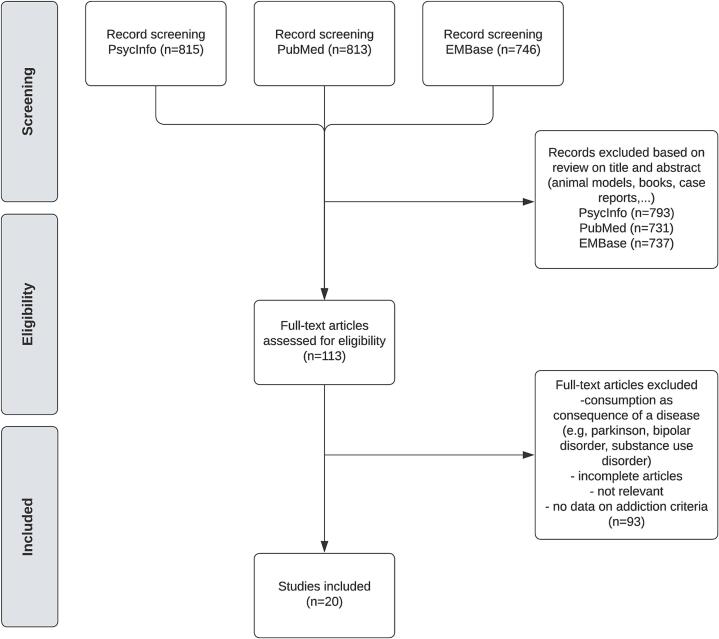

Articles were identified through the search of the databases: PsycINFO (n = 815), MEDLINE (n = 813) and Embase (n = 746). After review of titles and abstracts, 113 articles were selected for further examination. After reading the full text, 20 met inclusion criteria for this review. This process is described in the PRISMA flowchart (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA Flowchart of selected abstracts and articles.

3.2 Quality assessment

A summary of risk of bias is presented in Table 2. Seven studies were considered to be of “good” quality, 5 were “fair” quality and 8 of “poor” quality.

Table 2.

Overall quality rating of the included studies using the The National Institutes of Health quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies.

|

Q Study |

Q1 | Q2 | Q3 |

Q4 | Q5 |

Q6 |

Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 |

Q12 | Q13 | Q14 | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reid et al. 2012 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NA | NA | NA | N | Y | N | N | NA | N | Poor |

| Laier et al 2013 | Y | Y | NR | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Good |

| Kraus et al. 2014 | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | NA | Y | Y | Y | N | NR | Y | Fair |

| Kor et al. 2014 | Y | Y | NR | Y | N | N | NA | NA | N | NA | Y | N | NA | N | Poor |

| Laier et al.2014 | Y | N | NR | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Good |

| Carnes et al. 2014 | Y | N | NR | NR | N | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | N | Poor |

| Weinstein et al.2015 | Y | Y | NR | Y | N | NA | NA | NA | Y | N | Y | N | NA | Y | Poor |

| Snagowski et al.2015 | Y | Y | NR | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NR | Y | Good |

| Snagowski et al.2016 | Y | Y | NR | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NR | Y | Good |

| Wéry et al. 2016 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NA | NA | NA | Y | N | Y | NR | Y | N | Fair |

| Antons et al.2018 | Y | N | NR | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NR | Y | Good |

| Pékal et al. 2018 | Y | N | NR | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NR | Y | Good |

| Chen et al. 2018 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NA | NA | NA | Y | N | Y | NA | NA | Y | Fair |

| Antons et al.2019 | Y | Y | NR | N | Y | NA | NA | NA | Y | N | Y | N | NA | N | Poor |

| Antons et al. 2019 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NA | NA | NA | Y | N | Y | NA | NA | Y | Fair |

| Chen et al.2020 | Y | N | NR | Y | N | NA | NA | NA | Y | N | Y | N | NA | N | Poor |

| Mennig et al.2020 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NA | NA | NA | Y | NA | Y | NA | NA | N | Poor |

| Böthe et al. 2020 | Y | Y | N | Y | N | NA | NA | N | Y | N | Y | N | NA | N | Poor |

| Chen et al. 2021 | Y | Y | NR | Y | N | NA | Y | NA | Y | Y | Y | NA | N | Y | Good |

| Shirk et al. 2021 | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NA | NA | N | Y | N | Y | N | NA | Y | Fair |

Y = Yes; N = No; NR = Not Reported; NA = Not Applicable.

Q1: Was the research question or objective in this paper clearly stated?; Q2: Was the study population clearly specified and defined?; Q3: Was the participation rate of eligible persons at least 50%?; Q4: Were all the subjects selected or recruited from the same or similar populations (including the same time period)? Were inclusion and exclusion criteria for being in the study prespecified and applied uniformly to all participants?; Q5: Was a sample size justification, power description, or variance and effect estimates provided?; Q6: For the analyses in this paper, were the exposure(s) of interest measured prior to the outcome(s) being measured?; Q7: Was the timeframe sufficient so that one could reasonably expect to see an association between exposure and outcome if it existed?; Q8: For exposures that can vary in amount or level, did the study examine different levels of the exposure as related to the outcome (e.g., categories of exposure, or exposure measured as continuous variable)?; Q9: Were the exposure measures (independent variables) clearly defined, valid, reliable, and implemented consistently across all study participants?; Q10: Was the exposure(s) assessed more than once over time?; Q11: Were the outcome measures (dependent variables) clearly defined, valid, reliable, and implemented consistently across all study participants?; Q12: Were the outcome assessors blinded to the exposure status of participants?; Q13:Was loss to follow-up after baseline 20% or less?; Q14: Were key potential confounding variables measured and adjusted statistically for their impact on the relationship between exposure(s) and outcome(s).

3.3 Study characteristics

A detailed description of all studies included, and their main results can be found in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 3.

Details of experimental studies included in the review (N = 7).

| Study | Sample | Method | Assessment | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Laier et al., 2013 (Journal of Behavioral Addictions) |

171 German heterosexual men who used cybersex at least once recruited by advertisements in public or on campus of the University. Mean Age = 24.56 years. (Study 1)50 heterosexual males who perceived problems regarding controlling their cybersex use with 25 Problematic Cybersex Users (PCU) (sIATsex score > 30, Mean age = 23.96 y.) and 25 Health Cybersex Users (HCU) (Mean age = 22.88 y.). They were recruited by advertisements in local newspapers and by announcements in the public and on campus of University (Study 2) No data on cultural context. |

100 pornographic cues were presented to participants. Indicators of sexual arousal and need to masturbate were evaluated. The severity of cybersex addiction was assessed with a short version of the Internet Addiction Test (sIAT) modified for cybersex. Prior to (t1) and directly after (t2) the experimental paradigm, participants indicated their sexual arousal from 0 to 100 as well as their need to masturbate from 0 to 100. As indicators of craving, the sexual arousal and the need to masturbate at t1 were subtracted from the same collected data at t2. | sIATsex (Short Internet Addiction Test-Sex) Score Sexual arousal, need to masturbate, viewing time, craving from sexual arousal and the need to masturbate before and after exposure |

Sexual arousal and craving data of pornographic cues on the Internet were positively correlated with the sIATsex score and therefore with the presence and severity of sexual addiction. (Study 1)Significant difference in the intensity of craving and sexual arousal between the two groups with a higher intensity found in problem users. (Study 2) . The problematic cybersex users group showed higher subjective sexual arousal and a greater need to masturbate when being confronted with pornographic pictures. |

|

Kraus et al., 2014 (Archives of Sexual Behavior) |

221 American male students pornography users were recruited. Mean age = 21.8 y.; Sexual orientation: heterosexual = 81% (n = 179), gay/bisexual = 16% (n = 35,36), uncertain = 2% (n = 4,42) Ethnic data: 87% white/European, 4% black/African American, 9% other (Asian, latino, bi-racial) (Study 2) 67 male psychology students and pornography users were recruited by email. Mean age = 20.2 y. Sexual orientation: Heterosexual = 84% (n = 56), gay/bisexual = 11% (n = 7), uncertain = 2%. Ethnic data: 91% white/European, 5% black/African American, 2% other (Asian, latino, bi-racial) (Study 3) |

Exposure to pornography and to neutral images. Before exposure to sexual cues, participants were asked to imagine himself sitting in front of his computer, alone in his room, while experiencing a strong urge to watch his favorite type of pornography. Association of craving scores with weekly pornography use level, signal exposure, and sexual compulsivity (SCS) were assessed (Study 2).Test-retest reliability assessment at one week (Study 3) . |

Post-cue exposure reports of craving with PCQ (Pornography Craving Questionnaire)Sexual compulsivity by the SCS (Sexual Compulsivity Scale) . |

There was a main effect of typical weekly pornography use on total PCQ scores. Specifically, participants who used pornography 6 times a week reported higher craving than did individuals who used pornography 3-to-5 times per week who in turn reported higher craving than those who used pornography only 0-to-2 times per week. PCQ scores were significantly positively correlated with sexual compulsivity (SCS score). Weekly pornography use and PCQ scores were significant predictors of pornography use in the following week |

|

Laier et al., 2014 (Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and social networking) |

102 German adult heterosexual female participants (Mean age = 21.83 y.) were recruited by advertisements in public and at the University of Duisburg-Essen (Germany) in 2012Sample was separated into 2 groups: females watching pornography (hardcore pictures or videos) on the Internet on a regular basis (IPU) (n = 51) and females not watching hardcore pornography on the Internet (NIPU) (n = 51). No data on cultural context. |

Comparison of females IPU and NIPU on the severity of cybersex addiction (sIATsex), as well as propensity for sexual excitation, general problematic sexual behavior (HBI), and severity of psychological symptoms (in the last 7 days: BSI with Global severity index (GSI)). Additionally, an experimental paradigm, including a subjective arousal rating of 100 pornographic pictures, as well as indicators of craving, was conducted. | sIATsex (Short Internet Addiction Test-Sex), HBI (Hypersexual Behavior Inventory), BSI (GSI) overall scoreMeasurement before (t1) and after (t2) exposure: -Sexual arousal -Need to masturbate -Viewing time Calculation of craving from sexual arousal and the need to masturbate by subtracting t2 from t1. |

Average sexual arousal scores at pornographic images were higher for the IPU versus NIPU group with more intense craving for the IPU group.In the IPU group, overall sIATsex score correlated with sexual arousal and craving, |

|

Snagowski et al., 2015 (Addictive Behaviors) |

A total of 128 German heterosexual males (Mean age = 23.88 years), regular users, participated in the study. Individuals were recruited through local advertisements at the University of Duisburg-Essen (Germany) and online platforms. Participants reported that their age of first cybersex use was 15.51 years. No data about cultural context. | Participants completed a modified Implicit Association Test (IAT) with pornographic images. Viewing pornographic images made it possible to measure several data including craving. To assess tendencies towards cybersex addiction, sIAT-sex was used. Additionally, to assess sensitivity towards sexual excitation, a short form of the Sexual Excitation Scale was used (SES) and general problematic sexual behavior was measured by the Hypersexual Behavioral Inventory (HBI). | Sexual arousal and need to masturbate were assessed before (t1) and after (t2) sexual cue exposure on a scale ranging from 0 to 100.By subtracting t1 from t2 measurement, Δ-scores of sexual arousals and need to masturbate were computed and operationalized as subjective measures of craving, Tendencies towards cybersex addiction was assessed with the sIAT-sex Problematic Sexual Behavior was assessed with the Hypersexual Behavioral Inventory (HBI) Sensitivity to sexual arousal was assessed with the Sexual Excitation Scale (SES) |

Higher subjective craving was associated with tendencies towards cybersex addiction The craving Δ sexual arousal explained 19.1 % variance of the sIAT-sex craving/social problems. |

|

Snagowski et al., 2016 (Sexual addiction & compulsivity) |

86 German heterosexual men (Mean age = 23.70 years), regular cybersex users were recruited through local advertisements at University Duisburg-Essen and online platforms. The mean age of first cybersex use was 15.73 years. No data on cultural context. | The current subjective sexual arousal and need to masturbate were assessed before and after exposure to 50 pornographic images. Then, participants completed the S-PIT modified with pornographic pictures (S-PITsex). S-PIT is based on Pavlovian packaging related or not to substances. | Assessment of sexual arousal and the need to masturbate before (t1) and after (t2) exposure to pornographic images. Craving to pornography was measured by subtracting t1 from t2.The S-PIT adapted to pornographic images assesses whether sexual arousal (as a rewarding result) could be conditioned to neutral stimuli and whether these conditioned stimuli could induce craving Tendencies towards cybersex addiction were measured with sIATsex questionnaire. |

Cybersex addiction was associated with conditioning processes regarding pornographic images.Participants who reported both strong craving to pornography as well as high conditioning effects were at higher risk of being addicted to cybersex (sIATsex score) . |

|

Antons et al., 2018 (Addictive Behaviors) |

50 German heterosexual male students (Mean age = 23.30) who use heterosexual pornography were recruited through local advertisements at the University and online advertisement in the university's internal networks. No data on cultural context. | Each participant was exposed to neutral and pornographic images during a stop-signal task. Craving was assessed with a scale ranging from 0 to 100 at 3 points in time: before exposure, after neutral image and after pornographic image. | Craving was assessed with a scale ranging from 0 to 100Severity of problematic cybersex was assessed with the sIATsex (Short Internet Addiction Test-Sex) overall score. |

Positive association was found between sIATsex severity score and craving. Low craving level after exposure to a pornographic image, was associated with low severity of symptoms, while high craving and impulsivity scores were associated with higher sIATsex severity scores. |

|

Pekal et al., 2018 (Journal of Behavioral Addictions) |

174 German participants (n = 87 females, mean age = 23.59, range: 18–52 years) recruited trough offline and online advertisements at the University Duisburg-Essen. No data on cultural context. |

Sexual arousal and craving were induced by exposure to 100 pornographic pictures.Before (t1) and after (t2) the picture presentation, the participants had to indicate their current sexual arousal and their need to masturbate on a scale ranging from 1 to 100. The increase of sexual arousal(arousal Δ) and of the need to masturbate(craving masturbation Δ) were assumed as the indicators for cue-reactivity and craving responses and were calculatedby subtracting t2 from t1. Furthermore, the role of attentional bias in the development of internet sexual addiction was investigated. |

Sexual arousal and need to masturbate were assessed with a scale ranging from 1 to 100.Trends in problematic IP use were measured using the sIATsex (Short Internet Addiction Test-Sex) test. Attentional bias was assessed with the Visual Probe Task. |

Individuals with a high attentional bias towards sexual stimuli reported greater symptoms of problematic internet pornography use (craving). Significant positive correlations were found between: - the overall sIATsex score, the sIATsex-Loss of Control and sIATsex-craving subscales, as well as the increased need to masturbate, and sexual arousal. - the responsiveness to stimuli/craving and symptoms of problematic use of pornography on the Internet. |

Table 4.

Details of observational studies included in the review (N = 13).

| Study | Sample | Method | Assessment | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Reid et al., 2012 (Journal of Sexual Medicine) |

207 American patients were recruited (n = 29 females, n = 178 males) in various outpatient clinics that provided treatment for individuals with hypersexual disorder symptoms (n = 152, Mean age = 41.1 y.), psychiatric conditions (n = 35, Mean age = 38.1 y.), and substance-related disorders (n = 20, Mean age = 32.2 y.) Sexual orientation: homosexual: n = 17; bisexual: n = 10; heterosexual: n = 180 Ethnic representation among the group interviewers/raters: Asian (N = 2), East Indian (N = 1), and the remainder Caucasian (N = 10). Participants: Each participant was required to be at least 18 years of age, read and write English. Asian/pacific islander: 3,5%; Black/African American: 3,5%; Hispanic/latino: 3%; White/Caucasian: 90% |

Observational, cross-sectional study. Patients were assessed for psychopathology and hypersexual disorder (HD) by blinded raters to determine inter-rater reliability of the HD criteria and following a 2-week interval by a third rater to evaluate the stability of the HD criteria over time (n = 32). Patients also completed a number of self-report measures to assess the validity of the HD criteria. Several types of sexual practices were evaluated. |

HD-DCI (interview integrating the diagnostic criteria of hypersexual disorder proposed for DSM-5)HDQ (Hypersexual Disorder Questionnaire) : diagnostic criteria for hypersexual disorder in 10 itemsHDCQ (complement with frequency/intensity)HBI (Hypersexual Behavior Inventory) : Evaluating the use of sex to regulate stress or negative emotions, as well as loss of control, craving, and damage.SCS (Sexual Compulsivity Scale) : sexual compulsivityHBCS (Hypersexual Behavior Consequences Scale) : negative consequences related to sexual behavior |

Positive correlations between HD Interview items and other scales (HBI, HDQ, SCS): - excessive time, - response to negative emotions and stressful life events - loss of control, - physical/emotional damage, - psychological distress.HBCS score in subjects with a diagnosis of hypersexual disorder (n = 127): − 93.7% having a mental illness − 87.7% having had interpersonal damage with relatives − 77.9% having an impairment in their healthy sex − 52.7% having had financial losses − 39.3% having a love breakup − 27.5% having contracted an STI − 17.3% having had a job loss − 17.3% having had legal problemsThe majority of patients seeking treatment for hypersexual disorder (82%) reported a gradual progression of symptoms over a period of several months or years. The assessment at 2 weeks was stable. |

|

Kor et al., 2014 (Addictive Behaviors) |

A representative sample of the general population of Hebrew- speaking Israelis was recruited by a major Israeli website designed to collect panel data for surveys in social science. The samples of the three studies were independent. In study 3, 1720 subjects were included (834 men, 886 women) ranging in age from 18 to 70 years (Mean age = 39.52 y.) No data on cultural context. | Observational, cross-sectional study.This paper reports the findings of three studies aimed at developing and validating a new scale measuring problematic pornography use.In study 3: associations between PPUS scores and measures such as mental health and functioning problems, diminished self-esteem, insecure close relationships, a tendency for behavioral addictions, and a history of traumatic experiences, were examined. Participants completed the PPUS with a battery of other self-assessment scales. The order of scales was randomized between participants. |

PPUS global score, derived from HDQ (Hypersexual Disorder Questionnaire), sIATsex (Short Internet Addiction Test-Sex), Cyberpornography Use Inventory-9 (CPUI-9) Assessment of internet pornography use according to the DSM-5 addiction criteria.HBCS (Hypersexual Behavior Consequences Scale) score for consequences of sexual behavior |

Almost a third of the participants in the high PPUS median split (30.1%) reported that their sexual behavior caused problems in their life, compared to only 4.9% in the low PPUS median split. The former group completed the HBCS (n = 118), and the total PPUS score was significantly associated with more psychological distress with anxious, depressive symptoms, insecurities, and consequences on sexual behavior and self-esteem, resulting from sexual behavior. (Study 3) |

|

Carnes et al., 2014 (Journal of Addiction Medicine) |

4492 American subjects (men: n = 3951, 88%), presenting for inpatient (n = 345, 7.7%) or outpatient (n = 4147, 92.3%) treatment for sexual addiction. Sexual orientation: heterosexual: n = 3990, homosexual: n = 182, bisexual: n = 192 not reporting sexual orientation: n = 129 The sample consisted of 4016 (89.4%) individuals identifying as white, 135 (3.0%) identifying as black, 152 (3.4%) identifying as Hispanic, 56 (1.2%) identifying as Asian, and 133 (3.0%) identifying as “other.” |

Observational, cross-sectional study. The study examined the clinical relevance of diagnostic criteria for sex addiction in a clinical sample seeking treatment in terms of: - Endorsement rate - Severity of sex addiction according to DSM-5 guidelines for severity of substance use disorders |

Ten indicators of sexual addiction based on substance addiction criteria were used: 1/ Inability to resist urges to perform sexual behavior 2/ Use more than expected 3/ Unsuccessful efforts to reduce or stop use 4/ Excessive time spent preparing, making use and recovering from use 5/ Pursuit Despite Negative Consequences 6/ Obsessions/Craving 7/ Abandonment of activities 8/ Default of bonds 9/ Tolerance 10/ Withdrawal |

Endorsement rate above 60% for 7 of the 10 diagnostic criteria, regardless of genderLower endorsement rate for 3 criteria: Obsessions with preparing for sex, tolerance and given up activities because of sex (between 41.27% and 49.29%) .Participants with a high score on the SAST-R scale reported frequently items related to loss of control: “repeated failures to resist sexual impulses” (84.02% for men and 71.87% for women), “engaged more or longer than intended “(80.02% for men and 68.07% for women), “failure to quit despite desire or attempts” (79.65% for men and 64.91% for women), “excessive time obtaining/ recovering from sex” (68.11% for men and 66.24% for women) .Concerning addiction severity, more than half of the sample was of severe level (53.1%) , 15.4% was moderate, and 13.2% was mild. |

|

Weinstein et al., 2015 (Frontiers in Psychiatry) |

267 Israeli participants recruited from internet forums dedicated to pornography and cybersex in order to satisfy sexual curiosity and arousal. Inclusion criteria for compulsive sexual behavior were males and females who use the Internet for sex purpose. The sample included 192 men (72%) and 75 women (28%) with mean age for males 28.16 years and for females 25.5 years. Education attainments were 6.7% with university Master’s degree, 40.4% with university Bachelor degree, 27.7% high school education, 23.6% further education after high school, 1.5% with elementary school education. Employment status of the participants included 40.4% full-time employment, 35.6% part-time employment, and 24% unemployed. Marital status was 14.2% married, 57.7% bachelors, 23.6% in relationship but not married, 4% separated, 4.1% divorced. Most of the participants lived in the city (83.5%) and 16.5% lived in rural areas. Most of the participants were Jewish (91%), 2.2% Muslims, 4% Christians, and 2.8% others. |

Observational, cross-sectional study. Men and women were approached on the websites. They were asked to fill in questionnaires and send them by mail to the investigators. Questionnaires were anonymous. Participants were divided in 3 groups according to the frequency of cybersex use.Regression analysis, analysis of variance (ANOVA) , Pearson's correlational analysis between the frequency of cybersex use, the PCQ score and difficulties in intimate relationships, were carried out. |

Cybersex addiction test: frequency that you neglect your duties in order to spend more time in cybersex, the frequency that you prefer cybersex on intimacy with your partner, the frequency that you spend time in chat rooms and private conversations in order to find partners for cybersex, the frequency that people complain about the time that you spend onlinePCQ (Pornography Craving Questionnaire) Questionnaire on difficulties in intimacy. |

Craving for pornography, gender, and frequency of cybersex use, significantly predicted difficulties in intimacy and it accounted for 66.1% of the variance of rating on the intimacy questionnaire. Craving for pornography, gender, and difficulties in forming intimate relationships significantly predicted frequency of cybersex use and it accounted for 83.7% of the variance in ratings of cybersex use. Men had higher scores of frequency of using cybersex than women and higher scores of craving for pornography than women. |

|

Wéry et al., 2016 (Journal of Behavioral Addictions) |

From April 2011 to December 2014, 72 French subjects were recruited (n = 68, 94.4% males) at the Department of Addictology and Psychiatry of the Nantes University Hospital (France). Sample characteristics: Involved in a stable relationship (63.9%), highly educated (55.6% held a university degree), and active workers (73.6%). Inclusion criteria for this study: (a) a treatment-seeking person, (b) a native or fluent French speaker, (c) 16 years or older, (d) had to reach a defined threshold in the Sex Addiction Screening Test (SAST) and/or to endorse the diagnostic criteria of a modified version of Kafka’s criteria. The mean age was 40.33 years (SD: 10.93; range: 20–76). No data on cultural context, ethnic/race. | Observational, cross-sectional study. The objective was to describe the characteristics of a cohort of patients self-identified as “sex addicts” enrolled in an outpatient behavioral addiction program. Data was collected through a combination of structured interviews and self-assessment measures. Interview were by psychologists, targeting sexual behaviors and the consequences of sexual addiction. |

Overall SAST (Sexual Addiction Screening Test) scores Modified Kafka criteria Goodman criteria Consequences/harm of sex addiction Factors that promote addictive sexual behavior. |

The prevalence of sexual addiction diagnosis ranged from 56.9% to 95.8% depending on the criteria used (95.8% by SAST, 52.8% with modified Kafka criteria, 56.9% with Goodman criteria). The main negative consequences reported were:- Family life disruption (93.1%) with loss of confidence between partners (40.6%), decreased of commitment (25%) and sexual relations, divorce/separation (12.5%) .- Health disruption (81.9%) with depressive and anxious symptoms (42.1%), irritability (19.3%), shame (14%) and risky sexual behaviors (5.3%), sleep disruption (14%)- Social life disruption (69.4%)- Work disruption (68.1%) with having sexual behaviors and thoughts at work (85.5%) , losing job- Financial disruption (30.6%)The main reasons promoting addictive sexual behaviors were: looking for fun and excitement (45.8%), avoidance of real life (27.8%), loss of control (22.2%) , |

|

Chen et al., 2018 (Sexual addiction & compulsivity) |

A sample of Chinese college students was recruited by a major Chinese website designed to collect panel data for surveys in social science. Email invitations were sent to 1,100 college students (632 men, 478 women). 1,070 valid answers were received from 622 males and 448 females. The mean age was 20.19 ± 1.18 years. No data on cultural context, ethnic/race. |

A theoretical path model was proposed and tested to explain the role of quantity and quality of problematic Online sexual activities (OSAs) in mediating relationships between pornography craving and problematic use of OSAs. Path A indicates a simple correlation of the amount of pornography craving and problematic OSAs use. Path B describes the scenario in which pornography craving can lead to more frequent OSAs and pornography usage time, then problematic use of OSAs. Path C models indicates how problematic use of OSAs may lead to negative academic emotions.The first class represents non-problematic pornography users (470 individuals, 43.9%), the second class represents low-risk pornography users (375 individuals, 35.0%), and the third class represents at-risk problematic users (225 individuals, 21.1%) . The three groups were compared with respect to sIAT-sex items |

Pornography Craving Questionnaire (PCQ)sIAT-sex (Short Internet Addiction Test-Sex)Online Sexual Activities questionnaire, which measured participants’ use of the Internet for: (1) viewing sexually explicit material (SEM); (2) seeking sexual partners; (3) cybersex; and, (4) flirting and relationship maintenance |

The at-risk problematic use group scored higher on both sIAT-sex components and on other measures of sexual behaviors. Men had higher scores on the sIAT-sex and engaged in OSAs more frequently as compared to women. In the at-risk/problematic group, women sIAT-sex scores were similar to men. 20.63 % of students were in an at-risk/problematic-OSA-use group. This group demonstrated higher scores on all measures of severity including problematic OSAs use, quantity and frequency of use of OSAs, pornography craving.Compared to the non-problematic use group, the intermediate-risk group (35%) also demonstrated higher scores on measures of pornography craving, but scored comparably on OSAs use time. |

|

Antons et al., 2019 (Journal of Behavioral Addictions) |

1498 German heterosexual men who use internet pornography (IP) were recruited online via email invitations, social networking sites as well as offline via local advertisements at the university and nation-wide newspaper articles. Mean age M = 31.74, SD = 11.36, range: 18–83. No data on cultural context, ethnic/race. |

Observational, cross-sectional study.Impulsive tendencies (trait impulsivity, delay discounting, and cognitive style) ,Craving toward IP, attitude regarding IP, and coping styles were assessed in individuals with recreational–occasional (n = 333, Mean age = 30.44), recreational–frequent (n = 394, Mean age = 32.76), andunregulated (n = 225, Mean age = 31.96) IP use. |

sIATporn (Short Internet Addiction Test-Sex) overall severity score Frequency of internet pornography use: How many times do you use IP in a week? How long do you usually use PI within one session?CASBAporn (Craving Assessment Scale for Behavioral Addiction) for craving assessment integrating items related to reward, relief and obsessive craving (using a five-point Likert scale Attitude towards internet pornography Brief COPE for coping styles |

Craving and attitudes towards IP differed between groups. Attitude towards internet pornography was more negative among uncontrolled users versus frequent simple users.Individuals with unregulated use showed the highest scores for craving, and had more dysfunctional coping, Individuals with frequent but recreational (unproblematic) IP use also had a lower level of craving compared to those with unregulated IP use, indicating that extreme high craving is specific for unregulated IP use, but not for high-frequent use per se. |

|

Antons et al., 2019 (Personality and Individual Differences) |

1498 German heterosexual men who use internet pornography (IP) were recruited online via email invitations, social networking sites as well as offline via local advertisements at the university and through nation-wide newspaper articles. Mean age M = 31.74, SD = 11.36, range: 18–83. No data on cultural context, ethnic/race. |

Observational, cross-sectional study. Questionnaires of the online survey were answered in the following order: demographic variables, CASBAporn, Brief COPE, and sIATporn. Participants indicated theiramount of IP use, symptom severity of unregulated IP use, functional coping styles, and their craving towards IP The online-survey aimed to investigate the role of craving and impulsivity in the context of unregulated IP use. |

sIATporn overall severity score Internet pornography use CASBAporn for craving assessment integrating items related to reward, relief and obsessive craving (using a five-point Likert scale Brief COPE for coping styles |

sIATporn correlated significantly with CASBAporn with high effect size. Participants with higher sIATporn score exhibited higher craving. There was a positive association between symptom severity of unregulated IP use and IP use that was partially mediated by craving. Higher symptom severity of unregulated IP use was associated with higher craving responses which increased the likelihood of a higher amount of IP use. However, the effect of craving on the amount of IP use was moderated by functional coping styles. |

|

Chen et al., 2020 (International Journal of Environmental Research And Public Health) |

The sample consisted in 22 Chinese (20 men; mean age = 27.2) problematic internet pornography use service volunteers (who provide online services on health/well-being website) and 11 therapists (who have worked with individuals with problematic internet pornography use and had more than 3 years of clinical experience). No data on cultural context, ethnic/race. |

Observational, cross-sectional study. The main objective of this study was to compare different screening tools for problematic use of Internet pornography (IP) and to identify the most accurate measure. For this, 2 sub-studies (quantitative and qualitative) have been carried out. In the qualitative sub-study, interviews were conducted by 2 graduate students in psychology to assess the understanding of the Problematic Pornography Consumption Scale. The interviewees were required to rate theimportance of the dimensions on a scale that ranged from 1 (not at all important) to 7 (very important). |

The Problematic Pornography Consumption Scale (PPCS) with 6 dimensions: - salience, - mood modification, - conflict, - tolerance, - relapse, - withdrawal |

1/Salience (35%): 22% mentions for preoccupation, 7% for excessive use, 6% for pornography craving, 2/Mood modification (33%): 21% for avoid negative emotions, 3/Conflict (49%): 22% for interpersonal conflict, 11% for intrapsychic conflict and 16% for conflicts related to occupational or academic functioning. 4/Tolerance (33%): 18% for a longer duration of use and 15% for a more extreme content, 5/Relapse (58%): 16% for difficulties in control, 7% for sensitivity to pornographic cues, 13% for motivated by craving, 6/Withdrawal (45%) |

|

Mennig et al., 2020 (BMC Psychiatry) |

Data were collected via an online survey (October 2017 – January 2018) in Germany. The link to the questionnaire was posted to general and application-specific Internet forums, and mailing lists. At the outset, the participants specified whether they mainly used social networking sites or online pornography and were redirected to the corresponding questionnaire (SNS/OP). In Online pornography group, a random sample of 700 participants was analyzed (n = 537 males, n = 156 females, n = 7 preferred not to specify their sex). Mean age = 32.9. No data on cultural context, ethnic/race. | Observational, cross-sectional study.The aim of this study was to examine to which extent the conceptualization of the Internet Gaming Disorder can be adapted to the problematic use online pornography, from an already existing questionnaire, reflecting the DSM-5 criteria for Internet Gaming Disorder (Internet Gaming Disorder Questionnaire: IGDQ) . Analogously to the IGDQ, users with a score of ≥ 5 points were categorized as problematic users and all other users as non-problematic. Welch’s tests were computed to compare the groups regarding age, time spent using the Internet, time spent using their preferred application, sIAT and BSI scores. |

The Online Pornography Disorder Questionnaire (OPDQ) adapted from the Internet Gaming Disorder Questionnaire (IGDQ)Modified sIAT (Short Internet Addiction Test-Sex online pornography)Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) for psychological distress |

The item “Lying to watch OP” had the highest endorsement rate (n = 286) following by “Tolerance” (n = 161), “Unsuccessful efforts to reduce behavior” (n = 150), “Pursuit despite the negative consequences” (n = 152), “Regulate stress and negative emotions” (n = 139), “Time spent planning, realizing behavior” (n = 74) and “giving up activities” (n = 50)The item “Having interpersonal/professional problems” had the lowest endorsement rate (n = 24).The OPDQ scores correlated highly with the sIAT scores. Problem users, covering 7.1% of the sample (n = 50), had higher sIAT-porn scores, used the apps longer, and experienced more psychological distress compared to non-problem users |

|

Böthe et al., 2020 (The Journal of Sexual Medicine) |

Data collection occurred on a popular Hungarian news portal via an online survey from May to July in 2019. Of 12,026 individuals who accepted to participate in the study, 4,253 men (Mage = 38.33 years, SD = 12.40) were included to explore the structure of PPU symptoms in 2 distinct groups: considered treatment group (n = 509) and not-considered treatment group (n = 3,684). Sexual orientation: heterosexual (n = 3808, 89.6%), bisexual (n = 102, 2.39%), homosexual (n = 245, 5;76%), asexual (n = 9, 0.2%), unsure (n = 18, 0.4%), other (n = 11, 0.25%). 2,036 lived in the capital (47.9%), 1,750 in a town (41.2%), and 467 in a village (11.0%). As for the level of education, 66 had a primary level of education or less (1.6%), 207 had a vocational degree (4.9%), 1,328 had a high school degree (31.2%), and 2,652 had a college or university degree (62.4%). Regarding relationship status, 1,202 were single (28.3%), 3,022 were in any kind of romantic relationship (i.e., being in a relationship, engaged, or married) (71.1%), and 32 indicated the “other” option (0.8%). No mention on cultural context, ethnic/race. |

Observational study, retrospective. Aim: To explore the network structure of PPU symptoms, identify the topological location of pornography use frequency in this network, and examine whether the structure of this network of symptoms differs between participants who considered and those who did not consider treatment. Participants completed a self-report questionnaire about their past-year pornography use frequency. |

The PPCS-6 (Problematic Pornography Consumption Scale): 6 items with one item per each component: salience, tolerance, mood modification, relapse, withdrawal, and conflict. The pornography use frequency: past year frequency of online pornography. Symptoms of PPU were analyzed using a network analytic approach to identify clusters of central and peripheral symptoms. |

Two clusters of symptoms were identified in both groups, with the first cluster including salience, mood modification, and pornography use frequency and the second cluster including conflict, withdrawal, relapse, and tolerance. In the networks of both groups, salience, tolerance, withdrawal, and conflict appeared as central symptoms, whereas pornography use frequency was the most peripheral symptom. |

|

Chen et al., 2021 (American Psychological Association) |

8845 Chinese men (Mean age = 25.82 years, SD = 7.83, age- range = 18–65 years) who sought help for their pornography use on a self-help website, were invited to participate in the study A total of 972 (Mean age = 25.54 years, SD = 4.70, age-range = 18–47 years) of these help-seeking men participated in the 6-month follow-up survey. Sexual orientation: heterosexual: 91.1% (n = 8057), homosexual: 4.9% (n = 433), bisexual: 4.0% (n = 353). No data on cultural context, ethnic/race | Participants were new registered users of a nonprofit website focusing on helping individuals who reported Pornography problematic user in China. Participants voluntarily chose to complete the survey. Six months after the first time of responding to the survey, red dots appeared on the top of the questionnaire to remind users that they can complete the survey again. | The Brief Pornography Screen (BPS) (lack of control) Problematic Pornography Consumption Scale (PPCS) (Salience, mood modification, conflict, tolerance, relapse, and withdrawal) Pornography Craving Questionnaire (PCQ) Sexual Compulsivity Scale (SCS) |

A majority of the participants (91.4%) used online pornography and reported significantly higher scores on almost all pornography use-related variables. The Pornography problematic group reported the highest levels of sexual compulsivity, pornography cravings, time spent with pornography use, and online sexual activities. Impaired control moderately and positively predicted PPU over a period of 6 months, but it might not be a sufficient indicator of PPU in itself. |

|

Shirk et al., 2021 (Addictive Behaviors) |

The study was conducted in the USA with data from the Survey of the Experiences of Returning Veterans (SERV) study project. Of 283 veterans, 172 endorsed being male, ever watching pornography, and completed in full the PPUS and, therefore, were included in the study. The mean age was 33.9 (SD = 8.53) years. The sample consisted in 72.9% non Hispanic white/Caucasian, 6.5% non-Hispanic black/African American, and 20.6% identified as Other. A little over half were married or living with someone (55.8%). Education was dichotomized into high-school graduate/some college (62.8%) and college graduate (37.2%), and almost half the sample was employed full-time (49.4%) |

Observational, cross-sectional study. Subjects completed in full the Problematic Pornography Use Scale (PPUS) to be included in the study. Participants completed self- report questionnaires, including demographic information, psychiatric co-morbidities, impulsivity, as measured by the UPPS-P, pornography-related behaviors, and pornography craving as measured by Pornography Craving Questionnaire (PCQ). Descriptive statistics and hierarchical multivariable regressions were used. | Problematic Pornography Use Scale (PPUS) The Pornography Craving Questionnaire (PCQ) |

Higher frequency of pornography use and greater pornography craving were positively associated with PPUS scores. For the multivariable hierarchical regression, when the frequency of use and pornography craving scores were added for the final model, they were positively associated with PPUS scores. |

Among the 20 included studies, 7 were experimental studies and 13 observational studies. Half of the studies (n = 9) included populations of both sexes, while 10 studies focused exclusively on men and one study on women. Regarding the types of practices evaluated, 12 studies assessed internet pornography or cybersex, and 5 studies evaluated pornography in general. For 3 of the studies, the evaluation concerned a variety of sexual behaviors with or without internet support.

In total, 24.378 subjects were enrolled. Participants were more often males (n = 21.913; 89.8 %), with a mean age of 28.98 years. Most of the participants were heterosexual subjects (n = 18.355; 75.3%) or did not specify their sexual orientation (n = 4370) and 1576 subjects were homosexual or bisexual (6.46%). Participants were mostly recruited in care facilities (n = 14197, 58.23%), including outpatients (n = 4 354) and inpatients (n = 345), 8530 were enrolled from the general population, 1408 were students and 172 were veterans. Participants were often cybersex users (n = 12402, 51%). A summary of criteria studied and assessment tools is presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Criteria studied and assessment tools.

| Tools | Number of studies | Characteristics | Criteria studied | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sIAT-sex (Short Internet Addiction Test-Sex) | 11 studies | 12 items Severity score Self-questionnaire |

Use of behavior more than expected, Unsuccessful efforts to decrease or stop behavior Craving, |

Giving up important activities, Professional problems related to use Withdrawal |

| PCQ (Pornography Craving Questionnaire) | 4 studies | 12 items Self-questionnaire |

Craving to pornography (behavioral, emotional, and cognitive aspects) | |

| SCS (Sexual Compulsivity Scale) | 4 studies | 10 items Self-questionnaire |

More than expected use of behavior Craving Loss of control |

Existence of interpersonal and social problems related to use Failure in obligations |

| HBI (Hypersexual Behavior Inventory) | 3 studies | 19 items Self-questionnaire |

Unsuccessful efforts to reduce or stop problematic behavior Craving Continuation despite the consequences Giving up important activities |

Failure in obligations Use in dangerous situations Use of sex to regulate stress or negative emotions |

| PPCS (Problematic Pornography Consumption Scale) | 3 studies | Self-questionnaire | Unsuccessful efforts to reduce use Giving up important activities |

Tolerance Withdrawal |

| CASBA (Craving Assessment Scale for Behavioral Addiction) | 2 studies | Self-questionnaire | Items related to reward, relief and obsessive craving Five-point Likert scale |

|

| HBCS (Hypersexual Behavior Consequences Scale) | 2 studies | 23 items Self-questionnaire |

Consequences and damages (interpersonal, social, financial, professional environment) | Failure in obligations |

| HDQ (Hypersexual Disorder Questionnaire) | 2 studies | 10 items Self-questionnaire |

Craving Unsuccessful efforts to reduce or stop use, Increasing time related to use Use more than expected and in dangerous situations Continuation despite the consequences |

Giving up activities Failure in relation to obligations Interpersonal and social problems Withdrawal Tolerance |

| PPUS (The Problematic Pornography Use Scale) | 2 studies | 12 items 6-point Likert scale Self-questionnaire |

Craving Increased time related to use Use more than expected Unsuccessful efforts to reduce the consumption |

Interpersonal and social problems Failure in obligations Giving up important activities Use in dangerous situations |

| BPS (Brief Pornography Screener) | 1 study | Self-questionnaire | Loss of self-control Overuse of problematic pornography use |

|

| CPUI-9 (Cyberpornography Use Inventory-9) | 1 study | 9 items Self-questionnaire |

Craving Giving up important activities |

Failure in obligations Unsuccessful efforts to stop use |

| Cybersex addiction test | 1 study | Self-questionnaire | Failure of obligations Interpersonal problems Increasing time related to use |

|

|

Kafka’s criteria Goodman’s criteria |

1 study | Unsuccessful efforts to reduce or stop use Continued use despite the negative consequences Craving Increased time spent |

Use longer than expected Tolerance Failure in obligations Giving up important activities |

|

| OPDQ (Online Pornography Disorder Questionnaire) | 1 study | self-questionnaire |

Craving Unsuccessful efforts to reduce consumption Giving up important activities Continued use despite the negative consequences |

Interpersonal and social problems Withdrawal Tolerance |

| SAST-R (Sexual Addiction Screening Test-R) | 1 study | Self-questionnaire | Craving Unsuccessful efforts to reduce or stop |

Interpersonal social legal problems Giving up important activities |

3.4 Endorsement rate of addiction criteria among problematic sex users

3.4.1 Craving

The prevalence of craving among problematic sexual users seeking treatment was assessed in the study of Carnes et al. (Carnes et al., 2014). Results showed that “obsessions centered on sexual activities” were reported in this sample by 41.27% of men and 45.84% of women. In another study (Chen & Jiang, 2020), 22 problematic internet pornography users providing online services and 11 therapists were interviewed with the Problematic Pornography Consumption Scale. For the salience dimension, the preoccupation was reported by 22% of the participants, and craving for pornography by 6% of the participants. Craving (13%) and sensitivity to pornographic cues (7%) were considered as important motivations for relapse.

Salience defined as “preoccupation with pornography” appeared also as a core symptom of problematic pornographic use (PPU) in the study of Bothe et al. aimed to explore the network structure of PPU symptoms in a large-scale online sample (Bőthe et al., 2020).

3.4.2. Loss of control

The study by Carnes et al. (Carnes et al., 2014) found a clinically elevated mean score on the loss of control criteria among subjects with a high score on the Sexual Addiction Screening Test-R scale. Participants with a high score on this scale reported frequently: “repeated failures to resist sexual impulses”, “engaged more or longer than intended “, “failure to quit despite desire or attempts”, “excessive time obtaining/ recovering from sex”. In another study (Wéry et al., 2016), loss of control was reported by 22% of outpatients as a main reason to promote problematic sexual behavior. In the study by Chen et al. (Chen & Jiang, 2020), both therapists and volunteers emphasized relapse as “important feature in the problematic use” (58%), which was motivated by “difficulties in control” (16%). Finally, in an online survey of internet pornography use in a non-clinical sample (Mennig et al., 2020), the criterion “unsuccessful attempts to reduce or stop use” was endorsed by more than 20% of the respondents.

3.4.3. Negative consequences

Six observational studies investigated the prevalence of negative consequences related to problematic sexual behavior in clinical samples or in general population. In the study by Carnes et al. (Carnes et al., 2014), the prevalence of continuing sexual behavior despite problems ranged from 79.30% for men to 77.02% for women. The study by Reid et al. (Reid et al., 2012) showed that patients assessed for hypersexual disorder reported a vast array of negative consequences that were greater than those diagnosed with other psychiatric disorder or substance related disorder, affecting several areas of life. Similar results were found in another study (Kor et al., 2014) with an association between high PPUS scores and more life problems related to sexual behavior. The study of Wéry et al. involving individuals seeking treatment for problematic use of sex (Wéry et al., 2016) reported family life disruption as the more prevalent negative outcome, following by health disruption, social life, work, and financial disruption. Finally, high endorsement rate of given up or limited activities (46.97% for men and 47.74% for women) and of failure to fulfill major role obligations (64.59 % for men and 61.95 % for women) was found in the study by Carnes et al. (Carnes et al., 2014).

3.4.4 Withdrawal

In the study by Carnes (Carnes et al., 2014), prevalence of withdrawal symptoms, defined with “become upset, anxious, restless, or irritable if unable to engage in sexual behavior”, was 61.87% among men and 66.07% among women. Withdrawal was also reported by 45% of volunteer participants and therapists as important clinical feature of internet problematic sexual behavior (Chen & Jiang, 2020), without being specifically described. Böthe et al. considered withdrawal, defined as “psychological or physiological symptoms that appear in the absence of pornography use, such as the experience of mental distress”, to be a central symptom of PPU (Bőthe et al., 2020).

3.4.5. Tolerance

Tolerance was addressed in two studies by “requiring that an individual experience either a decreased response to the same sexual behavior, or need an increased amount or intensification of sexual behavior to obtain the same level of prior satisfaction” (Bőthe et al., 2020, Carnes et al., 2014). This item was endorsed by 45.12% of men and 49.29% of women treated for sexual addiction (Carnes et al., 2014) and was considered as a core symptom of PPU in the study by Böthe et al. (Bőthe et al., 2020). Both therapists and volunteers identified tolerance as a symptom of problematic pornography use, related to longer durations of use (18%) and more extreme content (15%) (Chen & Jiang, 2020). Tolerance was also endorsed by 22% of internet pornography users (Mennig et al., 2020), although this criterion was not clearly defined in the online survey.

3.5 Correlations between cue-induced craving, unregulated use and symptom severity

3.5.1. Experimental studies

Seven experimental studies were based on cue-reactivity paradigms to assess craving, involving students or participants recruited from the general population. Results were similar across studies, showing an association between sexual compulsivity, severity of addiction symptoms, frequency of use and intensity of craving after cue-exposure.

Kraus's study (Kraus & Rosenberg, 2014), involving a sample of students who regularly used pornography, showed a positive association between Pornography Craving Questionnaire (PCQ) score, the frequency of weekly pornography use and sexual compulsivity. PCQ scores after cue-exposure were significant predictors of pornography use in the following week. In another study (Antons & Brand, 2018), high intensity of craving after viewing a pornographic image combined with a high impulsivity score, was also associated with higher Short Internet Addiction Test-Sex severity scores.

The study of Laier et al. consisted in 171 heterosexual men recruited from the general population as well as heterosexual men who perceived problems regarding controlling their cybersex use (Laier et al., 2013). Tendencies towards cybersex addiction correlated with and were predicted by indicators of sexual arousal and craving to pornographic cues. Similar results were reported in another study of Laier published in 2014 (Laier et al., 2014), among heterosexual female Internet and non–Internet pornography users, with a correlation between the severity of addiction symptoms and the intensity of craving. In the study by Snagowski et al. (Snagowski et al., 2015), involving 128 heterosexual cybersex users, implicit associations interacted with high subjective craving and led thereby to stronger tendencies of cybersex addiction with an increased level of sexual arousal, the need to masturbate and craving. In a further study of Snagowski et al. (Snagowski et al., 2016), participants reporting both high craving to pornography as well as conditioning effects were at higher risk of being addicted to cybersex.

3.5.2. Observational studies

Craving was evaluated in 7 observational studies involving participants seeking treatment, or recruited from the general population, or students or veterans. The main finding was that craving level was associated with unregulated pornography use, frequency of use and symptom severity.

In the online study of Weinstein et al. (Weinstein et al., 2015), craving for pornography significantly predicted difficulties in intimacy and frequency of cybersex use, accounting for 58.8% of the variance in ratings of cybersex use. Similar results were found in the study by Chen et al. (Chen et al., 2018) showing a positive correlation between problematic Online Sexual Activities (OSA), pornography craving, frequency of OSA, and usage time. The online survey of Antons (Antons et al., 2019) involved 1.498 heterosexual males Internet pornography (IP) users and showed that individuals with unregulated use exhibited higher craving scores compared to recreational–occasional and recreational–frequent users. Further analysis (Antons, Trotzke, Wegmann, & Brand, 2019) demonstrated a positive association between symptom severity of unregulated IP use and IP use that was partially mediated by craving. Finally, among male US military veterans, the severity of craving and the frequency of engagement in the behavior, were strong predictors of problematic pornography use (Shirk et al., 2021).

3.6 Correlation between loss of control, cue-reactivity and problematic sex use

3.6.1 Experimental studies

Kraus et al.'s experimental study (Kraus & Rosenberg, 2014) showed that frequency of pornography use and craving intensity after cue-exposure were significant predictors of pornography use in the following week, suggesting a propensity to break off an engagement. In the study by Pekal et al. (Pekal et al., 2018), loss of control was significantly correlated with increased need to masturbate and sexual arousal after cue-exposure.

3.6.2 Observational studies

One study (Reid et al., 2012) evaluated the loss-of-control dimension in a sample of 207 adult individuals seeking treatment for hypersexual disorder, substance use disorder, or psychiatric disorder. Participants were assessed using the criteria proposed for hypersexual disorder in the DSM-5, including excessive time spent thinking, planning, or engaging in sexual behavior, as well as unsuccessful efforts to reduce or control excessive behavior. Results showed a positive correlation between the items mentioned, problematic sex use, and sexual compulsivity. Finally, Chen’s study (Chen et al., 2021) suggested that the lack of control may be a crucial criterion in the diagnosis process of PPU, useful to differentiate between individuals with self-perceived PPU and dysregulated pornography use (e.g. failed attempts to quit pornography use, continued use despite adverse consequences). Moreover, based on longitudinal results, they demonstrated that impaired control moderately and positively predicted PPU over a period of 6 months, but it might not be a sufficient indicator of PPU in itself.

4. Discussion

The objective of our work was to assess, based on a systematic review of the literature, the diagnostic similarities between problematic sexual behaviors and other addictions, according to DSM-5 criteria. Twenty studies fulfilled criteria for inclusion in this review of which 7 were experimental and 13 were observational. The majority of studies involved mixed samples, while 10 studies involved only men and only one study involved women. Our results showed a high prevalence of DSM-5 addiction diagnostic criteria among subjects with CSBD, particularly for craving, loss of control over sex use, and negative consequences related to sexual behavior. Cybersex was most often assessed, followed by pornography in general, and a variety of sexual behaviors with or without internet support. According to Wéry and Billieux (Wéry & Billieux, 2017), the predominant role of cybersex could be explained by the specific structural characteristics of the Internet that would contribute to the attractiveness of cybersex, illustrated by the “Triple A” model emphasizing access, affordability and anonymity.

So far, to conceptualize CSBD as an addictive disorder, a crucial part of the three sets of criteria proposed by Carnes, Goodman and Kafka include fundamental concepts of loss of control, excessive time spent on sexual behavior, and negative consequences for oneself and others. In line with this conceptualization, cross-sectional studies among problematic sex users showed significant endorsement rate of these criteria. While loss of control over behavior appears to be a central element of addictive behavior, the data in our review also highlighted the high prevalence of loss of control in clinical samples (Carnes et al., 2014, Chen and Jiang, 2020, Wéry et al., 2016) varying from 22% to 84%. Thus, according to Wéry et al. (Wéry et al., 2016), 22% of subjects considered the notion of loss of control as a factor favoring addictive sexual behaviors, 58% of subjects mentioned the phenomenon of relapse. In addition, the items “repeated failures to resist sexual impulses”, “engaged more or longer than intended”, “failure to quit despite desire or attempts”, “excessive time obtaining/recovering from sex” were also highly prevalent and appeared thereby as a key feature of problematic sexual behavior. Impaired control (Chen et al., 2021) and severity of craving (Shirk, 2021) were also found to be strongly predictive of problematic sexual behavior. These symptoms may thereby constitute a core symptom for CSBD screening as suggested by Böthe et al. (Bőthe et al., 2020), helping to determine whether pornography use is a problem, and to differential problematic to non-problematic users.

In line with these results, this review argues for a strong association between craving for sex/pornography and problematic sex use. Defined by an intense and irrepressible urge to engage in a specific rewarding behavior, craving has been recently identified as a core symptom of addictive behaviors in substance use disorders and behavioral addiction, and as a key factor in substance use and relapse (Fatseas et al., 2015, Hormes, 2017, Serre et al., 2015). Similar to substance addiction, craving was conceptualized as preoccupation and transient urge triggered by pornographic cues and was found in this review to be correlated to symptom severity of unregulated pornography use and frequency and/or quantity of use. Moreover, the studies of Anton et al. (Antons et al., 2019, Antons et al., 2019) also showed a salient association between craving and unregulated use, and points specifically to the mediation role of craving between symptom severity and use. This result support the hypothesis that higher craving responses associated with symptom severity increases the likelihood of a higher among of pornography use, and thereby leading to negative consequences and emotional distress. The direct association between craving and pornography use/sexual behavior, which is also found in substance use disorders, highlights its potential value as a target for intervention. On this issue, some findings suggested (Antons, Trotzke, Wegmann, & Brand, 2019) the importance of improving craving regulation through functional coping styles to have an effect on pornography use. In this way, findings from Anton et al. demonstrated the interaction between coping strategies, craving and reduction on pornography use. Anticraving medications indicated for substance use disorders such as opioid-receptor antagonists could also be advantageous for individuals with CSBD to reduce intensity of sexual urges as suggested by previous works (Kraus, Meshberg-Cohen, Martino, Quinones, & Potenza, 2015). In addition, results of the present review highlight the relevance of clinical markers of addiction (e.g. repeated attempts to quit, craving, cue reactivity) rather than frequency of sexual behaviors that should contribute to improve diagnosis consistency and treatment availability and to reduce associated social and psychological harms.

Besides clinical considerations, neuroimaging studies emphasize parallels between CSBD and other behavioral addictions and substance-related disorders ( Gola et al., 2017, Voon et al., 2014, Brand et al., 2016), showing activity in the ventral striatum, known to participate in reward anticipation and craving, after cue-exposure. In the study of Gola et al. (Gola & Draps, 2018), this brain activation in subjects with CSBD was accompanied by measures suggesting increased behavioral motivation to view erotic images and was significantly related to severity of problematic sexual behavior, amount of pornography use per week, and frequency of masturbation. That way, beyond validation of diagnostic criteria, theoretical approaches such as the I-PACE model for describing psychological and neurobiological processes of CSBD should also be investigated to achieve a better understanding of the underlying nature of the problematic behavior (Brand et al., 2019). Finally, the potential efficacy of psychedelic-assisted therapy in the treatment of CSBD viewed as an addictive disorder has been suggested regarding therapeutic and neural processes (Wizła, Kraus, & Lewczuk, 2022).

Several limitations in this systematic review should be considered. A first concern is the heterogeneity of the selected studies in terms of populations, sexual practices, tools for assessing addiction criteria, and difficulty in validating diagnostic thresholds of sexual addiction. Most studies included could be qualified as being fair or poor of quality. This may be partly explained by the fact that most of the studies were observational, using a large variety of self-report questionnaires to assess sexual behavior with differences in assessing the addictive dimension of sexual behavior, and confounding factors. Particularly, few studies included women and sex differences in the analysis, while some data indicate gender effects in the context of unregulated pornography use (Pekal et al., 2018), which limit the generalization of the data. Results should be replicated in females and non-heterosexual samples. Furthermore, few studies have examined the sociocultural context of CSBD with the exception of sexual orientation. Further assessment and treatment approaches should be developed to take into account the influence of minorities, different ethnic groups, gender and sociocultural contexts and norms. Finally, Kafka and Goodman proposed to include items on pleasure seeking or the relief of negative affect, but these criteria were not specifically assessed in this review. However, the negative and positive reinforcement value of sexual behaviors were found as relevant factors promoting sexual behaviors in the study of Wéry et al.. In another study, to cope with negative affect was correlated with overall scores of addiction criteria and sexual compulsivity among problematic sex users (Wéry et al., 2016). The predictive value of positive and negative reinforcement of sexual behavior for addiction criteria should be more investigated to add the clinical utility of these items.

To conclude, our work highlights the prevalence and relevance of core behavioral markers of addictive disorders among subjects seeking help for their sexual behaviors. Particularly, results challenge the screening of CSBD pointing out the relevance of considering loss of control and craving criteria. More studies should be done to assess homogeneously according to the DSM-5 criteria the addiction-like features of problematic sexual behaviors in clinical and non-clinical populations. Furthermore, this work argues for the need of further research to examine the extent to which anti-craving interventions could be effective in improving clinical outcomes.

interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Role of Funding Sources.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Natasha Pistre: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft. Benoît Schreck: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Marie Grall-Bronnec: Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Melina Fatseas: Conceptualization, Supervision, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest