Abstract

Bacillus subtilis produces a 30-kDa peptidoglycan hydrolase, CwlH, during the late sporulation phase. Disruption of yqeE led to a complete loss of CwlH formation, indicating the identity of yqeE with cwlH. Northern blot analysis of cwlH revealed a 0.8-kb transcript after 6 to 7.5 h for the wild-type strain but not for the ςF, ςE, ςG, and ςK mutants. Expression of the ςK-dependent cwlH gene depended on gerE. Primer extension analysis also suggested that cwlH is transcribed by EςK RNA polymerase. CwlH produced in Escherichia coli harboring a cwlH plasmid is an N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine amidase (EC 3.5.1.28) and exhibited an optimum pH of 7.0 and high-level binding to the B. subtilis cell wall. A cwlC cwlH double mutation led to a lack of mother cell lysis even after 7 days of incubation in DSM medium, but the single mutations led to mother cell lysis after 24 h.

Bacillus subtilis produces a complement set of enzymes capable of hydrolyzing the shape-maintaining and stress-bearing peptidoglycan layer of its own cell wall (6, 37, 45). Some of these peptidoglycan hydrolases can trigger cell lysis and therefore can be called autolysins or suicide enzymes (37). Autolysins have been implicated in several important cellular processes, such as cell wall turnover, cell separation, competence, and flagellation (motility), in addition to cell lysis, and they act as pacemaker and space maker enzymes for cell wall growth (2, 7, 8, 33, 37). Therefore, fine-tuning of autolysin activity through efficient and strict regulation is a must for bacterial survival (13).

Two major vegetative-phase autolysins, (i) a 50-kDa N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine amidase (amidase), CwlB (LytC), and (ii) a 90-kDa endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase (glucosaminidase), CwlG (LytD), were initially purified from B. subtilis and characterized (12, 18, 22, 25, 35, 38). A study on the physiological functions of CwlB and CwlG revealed that CwlB is responsible for cell lysis in the stationary phase (18) and after cold shock treatment (49) and that both proteins, but only in concert, are required for the motility function (34). Several other amidase genes and their homologs have been cloned from B. subtilis. Four prophage-encoded amidase genes (cwlA, xlyA, xlyB, and blyA) (5, 9, 17, 24, 36), a sporulation-specific amidase gene (cwlC) (10, 16), a cortex maturation-specific and deduced amidase gene (cwlD) (41), and germination-specific and deduced amidase genes (sleB and cwlJ) (30, 15) have been cloned and studied, in addition to cwlB (18). Recently, endopeptidase homologs (CwlF [LytE] and CwlE [LytF]) playing roles in cell separation during vegetative growth were found (14, 26, 27, 32). Regarding the sporulation phase-specific expression of autolysin genes, Smith et al. found minor autolysins (A3, A6, and A7) during the sporulation phase (46). They also reported that a cwlB cwlC double mutant was found to be resistant to mother cell lysis during the late stage of sporulation (47).

The B. subtilis genome contains many cell wall hydrolase gene homologs (43, 20). To determine the cellular functions of these homologs, it is necessary to determine the expression phases for the genes and to construct disruptants. Moreover, the amino acid sequence similarity of these homologs is a clue for determination of their cellular functions. For instance, amidases in B. subtilis can be divided into three classes, I (CwlA, XlyA, XlyB, and BlyA), II (CwlB, CwlC, and CwlD), and III (SleB and CwlJ) (15). Class I seems to be associated with phage lysins, but classes II and III play roles in various cellular functions and germination, respectively. The yqeE gene belongs to class I (28), but there is no information on its gene expression or cellular function.

In this study, we identified yqeE as a new cell wall hydrolase gene, cwlH, during the sporulation phase of B. subtilis, characterized its expression, and determined the cellular function of the gene product, which is unique in class I.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The strains of B. subtilis and Escherichia coli and the plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. B. subtilis was grown on Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (39) or DSM (Schaeffer) medium (40). If necessary, tetracycline, chloramphenicol, and erythromycin were added to the medium to final concentrations of 10, 5, and 0.3 μg/ml, respectively. E. coli was grown in LB medium or 2×YT medium (39). If necessary, ampicillin was added to a final concentration of 50 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| B. subtilis | ||

| 168 | trpC2 | 47 |

| AC327 | purB his-1 smo-1 | 41 |

| CWLHd | trpC2 cwlH::pMUTIN2 | This study |

| ANC1 | purB his-1 smo-1 cwlC::cat | 16 |

| ANB1 | purB his-1 smo-1 cwlB::tet | This study |

| ABC | purB his-1 smo-1 cwlB::tet cwlC::cat | This study |

| ABH | purB his-1 smo-1 cwlB::tet cwlH::pMUTIN2 | This study |

| ACH | purB his-1 smo-1 cwlC::cat cwlH::pMUTIN2 | This study |

| ABCH | purB his-1 smo-1 cwlB::tet cwlC::cat cwlH::pMUTIN2 | This study |

| 1G12 | gerE36 leu-2 | BGSCa |

| 1G1ΔcwlH | gerE36 leu-2 cwlH::pMUTIN2 | This study |

| 1S38 | trpC2 spoIIIC94 | BGSC |

| 1S60 | leuB8 tal-1 spoIIG41 | BGSC |

| 1S86 | trpC2 spoIIA1 | BGSC |

| SpoIIIGΔ1 | trpC2 spoIIIGΔ1 | P. Setlow |

| ADD1 | purB his-1 smo-1 cwlD::cat | 40 |

| EDD1 | trpC2 cwlD::cat | B. subtilis 168 transformed with ADD1 DNA |

| E. coli | ||

| JM109 | recA1 supE44 endA1 hsdR17 gyrA96 relA1 thi-1 | Takara |

| C600 | supE44 hsdR thi-1 leuB6 lacY1 tonA21 | Laboratory stock |

| M15 | F− Strr ΔlacZ | QIAGEN |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC118 | Apr | Takara |

| pQE-31 | Apr | QIAGEN |

| pMUTIN2 | EmrlacI lacZ | 47 |

| pGEM3zf+ | Apr | Promega |

| pCLTC | AprcwlB::tet | 33 |

| pMCWLH | EmrcwlH-lacZ lacI | This study |

| pGCWLH | Apr | This study |

| pUCH2 | AprcwlH | This study |

| pQCH2 | AprcwlH | This study |

BGSC, Bacillus Genetic Stock Center, Ohio State University.

Plasmid and mutant construction.

The entire cwlH gene was amplified by PCR using two primers, forward primer ECHF (5′-CGCCCCGGGA1TGGTAACCATAAAAAAGG20; the cwlH sequence is italicized, numbering is with respect to the first A of the translational start codon of cwlH, and the SmaI site is underlined) and reverse primer ECHR (5′-CGCGTCGACT773TATCCGTTAAATCCTGC756; the sequence complementary to the downstream region from cwlH is italicized, and the SalI site is underlined), with B. subtilis 168 DNA as a template. The PCR fragment was digested with SmaI and SalI, followed by ligation into the corresponding sites of pUC118. The DNA solution was used for the transformation of E. coli JM109 cells; then the resulting plasmid, pUCH2, was digested with SacI and SalI, followed by agarose gel electrophoresis. A 0.8-kb DNA fragment extracted from the gel was ligated to the SacI and SalI sites of a histidine-tagged plasmid, pQE-31, and then used for the transformation of E. coli M15(pREP4). The resultant plasmid, pQCH2, contained a histidine-tagged sequence (MRGSHHHHHHTDPHASSVPG) at its N terminus fused with the structural gene cwlH. Therefore, the histidine-tagged cwlH (h-cwlH) gene encodes a 270- amino-acid (aa) polypeptide with an Mr of 29,741.

To construct the B. subtilis cwlH-lacZ strain, an internal fragment of the cwlH gene was amplified by PCR using two primers, forward primer CWLHF (5′-GCCGAAGCTTG94CGAATACAGCCAAAGGC111; the internal sequence of the cwlH region is italicized, numbering is with respect to the first A of the translational start codon of cwlH, and the HindIII site is underlined) and reverse primer CWLHR (5′-CGCGGATCCA353TCAGCTTTCTGATCAGCC335; the sequence complementary to the internal region of cwlH is italicized, and the BamHI site is underlined), with B. subtilis 168S DNA as a template. The PCR fragment was digested with HindIII and BamHI. pMUTIN2 was digested with HindIII and BamHI and then ligated to the digested PCR fragment, followed by transformation of E. coli JM109. The resulting plasmid, pMCWLH, was used for the transformation of E. coli C600 to produce concatemeric DNAs (4). pGEM-3zf(+) was digested with HindIII and BamHI and then ligated to the digested PCR fragment, followed by transformation of E. coli JM109. The resulting plasmid, pGCWLH, was used to synthesize an RNA probe. To construct B. subtilis ANB1 (cwlB), pCLTC, containing the cwlB::lacZ fusion, was digested with EcoRI and then used for transformation of B. subtilis AC327. B. subtilis ABC (cwlB cwlC) was constructed by transformation of B. subtilis ANB1 with B. subtilis ANC1 (cwlC) DNA. B. subtilis 1G1ΔcwlH (gerE cwlH) was constructed by transformation of B. subtilis 1G12 (gerE) with B. subtilis CWLHd DNA. Competent cells of B. subtilis ANB1, ANC1, and ABC were transformed with B. subtilis CWLHd DNA. The resultant mutants, ABH, ACH, and ABCH, respectively, were used for zymographic analysis of cell wall hydrolase activity and also for morphological analysis. The cwlH disruption of the mutants was confirmed by long-range PCR using a Gene Amp XL PCR kit (Perkin-Elmer).

Transformation of E. coli and B. subtilis.

E. coli transformation was performed as described by Sambrook et al. (39), and B. subtilis transformation was performed by the competent cell method (1).

Purification of the CwlH protein.

E. coli M15(pREP4, pQCH2) was cultured in LB medium containing ampicillin (200 ml) to a cell density (optical density at 600 nm [OD600]) of approximately 0.8 at 37°C. Then 2 mM (final concentration) isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside was added to the culture, followed by further incubation for 3 h. The culture was centrifuged, and the pellet was suspended in 50 ml of 10 mM imidazole NPB solution (10 mM imidazole and 1 M NaCl in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer [pH 7.4]). After ultrasonication, the suspension was centrifuged, and the supernatant (25 ml) was filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size membrane filter (Nalgene), followed by application onto a HiTrap chelating column (1 ml; Pharmacia). The column was washed with 10 mM imidazole NPB solution (20 ml), and then the h-CwlH protein was eluted with the NPB solution containing a stepwise gradient of imidazole from 30 to 60 mM.

Preparation of cell walls.

Cell walls of B. subtilis 168S and Micrococcus luteus ATCC 4698, unless otherwise noted, were prepared essentially as described previously (8, 17).

SDS-PAGE and zymography.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) of proteins was performed in 10 or 12% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gels as described by Laemmli (21). Zymography was performed essentially as described by Leclerc and Asselin (23), using SDS-polyacrylamide gels containing 0.1% (wt/vol) B. subtilis cell wall, M. luteus cell wall, or B. subtilis cortex as a substrate.

Cell wall hydrolase assay.

B. subtilis cell wall was suspended in 0.1 M TMB buffer (0.1 M Tris, 0.1 M maleic acid, 0.1 M bovic acid; adjusted to pH 7.0) to yield a final absorbance of 0.3 at 540 nm. The purified t-CwlH was added to the solution, followed by incubation at 37°C. One unit of cell wall hydrolase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme necessary to reduce the absorbance at 540 nm by 0.001 per min.

Measurement of the optimal pH.

B. subtilis cell wall was added to various buffer solutions to yield a final absorbance at 540 nm of 0.3. Purified h-CwlH was added to the buffers, followed by incubation at 37°C for 10 min. The buffers used for pHs 3 to 5 and 5 to 10 were 0.1 M citrate buffer and 0.1 M TMB buffer, respectively.

Cell wall binding ability.

The cell wall binding ability of the enzyme was examined in distilled water containing 5.5 μg of the purified protein and 10 mg of B. subtilis cell wall. After 30-min incubation at 0°C, the reaction mixture was centrifuged, and then protein in the supernatant was applied to a gel. After SDS-PAGE, the amount of protein in the supernatant was measured by densitometric analysis.

Identification of the specific substrate bond cleaved by the cell wall hydrolase.

The amino groups released during enzyme digestion of B. subtilis cell wall were labeled with 1-fluoro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (18). Dinitrophenyl (DNP) derivatives were separated by ODS column (Wakosil-II5C18) chromatography, and d and l isomers of DNP-alanine were separated by Sumichiral OA-2500S column chromatography (18).

β-Galactosidase assay.

The β-galactosidase assay was performed basically as described by Shimotsu and Henner (44). One unit of β-galactosidase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme necessary to release nmol of 2-nitrophenol from 2-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside in 1 min.

Northern blot and primer extension analyses.

B. subtilis cells (15 OD600 units) cultured in DSM medium were harvested and then suspended in 1 ml of chilled killing buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5] containing 5 mM MgCl2 and 20 mM Na2N3 (14). After centrifugation at 11,000 × g for 2 min, the pellet was suspended in 1 ml of SET buffer containing lysozyme (final concentration 6 mg/ml) (14). After incubation at 10 min at 0°C, the suspension was centrifuged at 11,000 × g for 2 min. The pellet was used for RNA preparation with Isogen (Nippon Gene) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Agarose-formaldehyde gel electrophoresis was performed as described by Sambrook et al. (39). The transfer of RNAs onto a nylon membrane (Magnagraph; Micron Separations) was performed with a vacuum blotter (model BE-600; BIOCRAFT). The DNA fragment used for preparing an RNA probe was amplified by PCR with M13(−21) and M13RV as primers and pGCWLH DNA, containing the internal region of cwlH, as a template. The amplified fragment was digested with HindIII; the resulting fragments were purified by phenol and chloroform treatments and precipitated with ethanol. The RNA probe was prepared with a DIG (digoxigenin) RNA labeling kit (Boehringer Mannheim), and Northern (RNA) hybridization was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Primer extension analysis was performed as described previously (41), using primer PEH1 (5′-CCATCGCATAGCCAGGACGA; the 5′ and 3′ ends corresponding to the complementary nucleotides at positions 64 and 45 with respect to the 5′ end of the cwlH gene).

Microscopic observation and cell density determination.

Cells were shake-cultured in a test tube (17-mm diameter) containing 5 ml of DSM medium at 37°C. After 1 and 7 days, 5-μl samples were mixed with 5 μl of 2% agarose on slide glasses, and then the cell morphology was observed by phase-contrast microscopy. The OD600 was measured after strong vortexing of samples. In the case of filamentous mutant cells, a small amount of lysozyme was added to the samples just before vortexing.

RESULTS

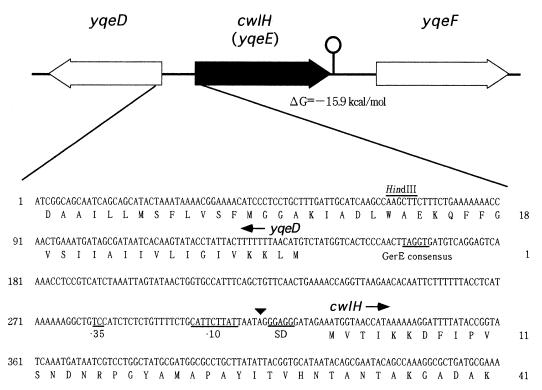

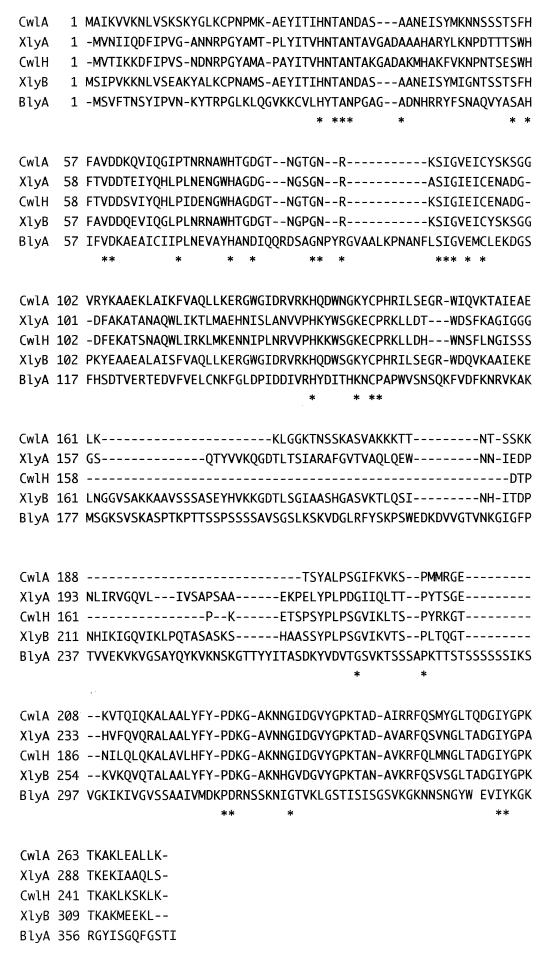

Paralog analysis of many cell wall hydrolase genes in B. subtilis revealed that the yqeE gene is located at 226° on the B. subtilis chromosome. This gene encodes a 250-aa polypeptide with an Mr of 27,571 (20). Figure 1 shows the gene organization of the yqeE gene and its flanking regions and the nucleotide sequence of the upstream region of yqeE. The amino acid sequence of YqeE (designated CwlH) exhibits 59.6, 44.7, 42.8, and 27.1% identity with those of B. subtilis XlyA (297 aa), B. subtilis CwlA (272 aa), B. subtilis XlyB (317 aa), and B. subtilis BlyA (367 aa), respectively (5, 9, 17, 24, 36).

FIG. 1.

Gene organization of yqeE (designated cwlH) and its flanking regions, and nucleotide sequence of the upstream region of cwlH. The peptides are numbered with respect to the translational start codon (+1) of each protein. −35 and −10 represent the −35 and −10 regions of a ςK promoter, and SD represents a Shine-Dalgarno sequence. The arrowhead indicates the transcriptional start point of cwlH. The GerE consensus sequence and restriction sites are shown by underlining and overlining, respectively, of the nucleotide sequence.

Expression of h-CwlH in E. coli.

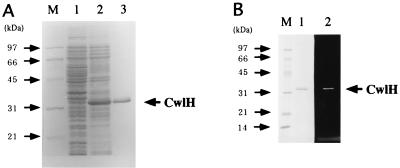

pQCH2 containing a histidine-tagged sequence followed by the cwlH gene was introduced into E. coli cells as described in Materials and Methods, and the h-CwlH protein (270 aa) was expressed by IPTG induction. Figure 2A shows the results of SDS-PAGE analysis of the expression of h-CwlH. A large amount of h-CwlH was accumulated in E. coli cells (lane 2), and the Mr of 31,000 was in good agreement with that calculated from the sequence (29,741). The h-CwlH protein was purified by nickel affinity chromatography, and the purified protein was run in lane 3.

FIG. 2.

SDS-polyacrylamide (12%) gel electrophoretic analysis of expression of the CwlH protein in E. coli(pREP4, pUCH2) (A) and zymography of CwlH with B. subtilis 168 cell wall (B). (A) E. coli M15(pREP4, pUCH2) cells were cultured in 100 ml of LB medium at 37°C. When the cell density reached 0.8 at OD600, 2 mM (final concentration) IPTG was added to the culture, followed by further incubation for 3 h. The cells were washed and sonicated, and then the broken-cell suspension was centrifuged. Proteins in the supernatant (equivalent to the 0.1 OD600 cells) were loaded onto lane 2. Lane 1 is a sample without IPTG induction. Lane 3 is the purified CwlH protein (7.5 μg) after nickel affinity column chromatography. M, marker proteins (Bio-Rad broad-range markers [1.5 μg of each]; from top to bottom, 97.4, 66.2, 45.0, 31.0, and 21.5 kDa). (B) The purified CwlH (1 μg) was loaded onto lanes 1 and 2. Lanes M (marker proteins) and 1, SDS-PAGE; lane 2, zymography with strain 168 cell wall. Zymographic patterns toward the M. luteus cell wall, 168 spore cortex, and muramic acid lactam-deficient EDD1 cortex were very similar to that toward the 168 cell wall (B, lane 2; reference 31).

Characterization of the h-CwlH protein.

The substrate specificity of the purified h-CwlH protein was determined by zymography with B. subtilis and M. luteus cell walls and the wild-type and modified (muramic acid lactam-deficient) cortex. The h-CwlH protein gave a clear hydrolyzing band with all of the above substrates on zymography (Fig. 2B) (31). The optimal pH was 7.0 (relative activities of 5.1% at pH 5.0, 47.5% at pH 6.0, 100% at pH 7.0, 94.9% at pH 8.0, 55.9% at pH 9.0, and 47.5% at pH 10.0). The specific activity of h-CwlH under the optimal conditions was 1.6 × 104 U per mg of protein. The h-CwlH protein was completely bound to B. subtilis cell wall in distilled water.

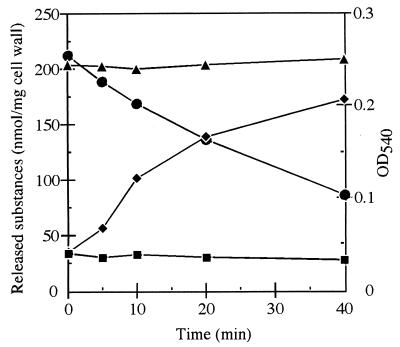

The purified h-CwlH protein was added to the B. subtilis cell wall, and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for various time periods. The products resulting from the enzyme reaction were investigated by labeling of free amino groups with 1-fluoro-2,4-dinitrobenzene, followed by chromatography as described in Materials and Methods. Only DNP-l-alanine increased during the enzyme reaction (Fig. 3). Therefore, this protein is an N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine amidase.

FIG. 3.

Digestion of B. subtilis cell wall with the purified CwlH protein. B. subtilis cell wall (2.0 mg) and the purified CwlH (9.6 μg) were mixed in 6 ml of a 1% potassium borate solution (pH 9.0) and then incubated at 37°C. Aliquots (500 μl of each) was removed at various intervals for determination of turbidity at 540 nm (●), DNP-diaminopimelic acid (▴), DNP-l-alanine (⧫), and DNP-d-alanine (■).

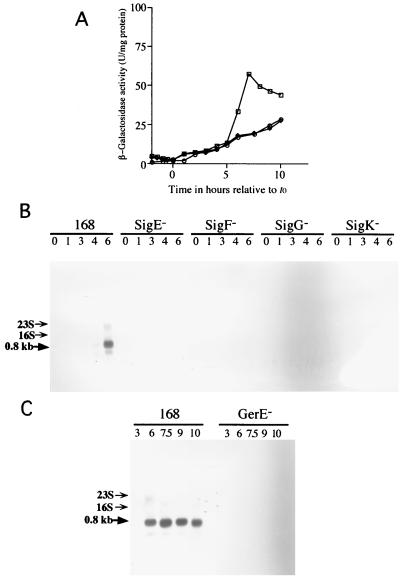

Regulation of the cwlH gene.

A transcriptional fusion between cwlH and lacZ was constructed with a 8.9-kb plasmid, pMCWLH, containing the internal region of CwlH in the B. subtilis chromosome. The cwlH lacZ strain, CWLHd, expressed significant lacZ activity during the late sporulation stage (Fig. 4A). Northern hybridization analysis of the cwlH gene with a specific RNA probe consisting of the internal region (HindIII-BamHI region) of cwlH revealed a single 0.8-kb signal band at t6 (6 h after onset of sporulation) for the wild-type 168 strain, but no hybridizing band was observed for the sigE, sigF, sigG, and sigK-deficient strains (Fig. 4B). Since some of the SigK-dependent genes are also regulated by the gerE gene, the GerE dependence of the cwlH gene was determined with the gerE-deficient strain, 1G12. No 0.8-kb transcript was observed for the 1G12 strain (Fig. 4C). These results shows that the cwlH gene is transcribed by EςK RNA polymerase and regulated by the GerE protein.

FIG. 4.

(A) β-Galactosidase activities of the cwlH-lacZ transcriptional fusion strains constructed in the B. subtilis chromosome. The strains were grown in DSM medium at 37°C. Squares, strain CWLHd; circles, strain 1G1ΔcwlH, diamonds, strain 168. (B and C) Northern hybridization analysis of cwlH with a specific RNA probe. B. subtilis total RNAs from cultured cells were purified with Isogen (numbers indicate the times [hours] after onset of sporulation), and 10 μg of each RNA was separated on a 1% formaldehyde agarose gel. Signals were detected with the digoxigenin-labeled RNA probe. The cwlH mRNA signal is indicated by a thick arrow; positions of 23S and 16S RNAs are indicated by thin arrows. 168, B. subtilis 168; SigE−, 1S60 (spoIIG); SigF−, 1S86 (spoIIA); SigG−, spoIIIGΔ1 (spoIIIG); SigK−, 1S38 (spoIIIC); GerE−, 1G12 (gerE).

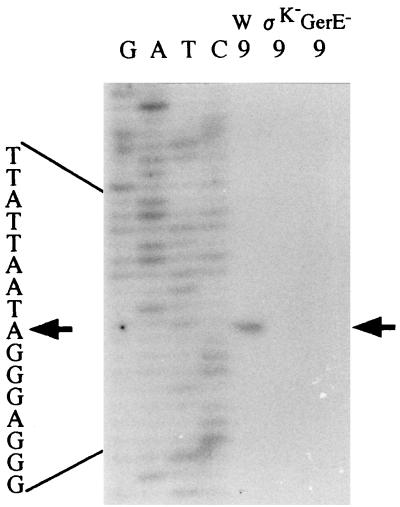

Primer extension analysis of the cwlH gene with the primer, PEH1, corresponding to the 5′ end of cwlH, revealed one transcriptional start point, A, at position −14 with respect to the translational start point of cwlH (t7.5 sample for the 168 strain in Fig. 5). RNAs of the 168 strain at t3 and the ςK-deficient strain at t7.5 did not show the transcriptional start point (Fig. 5). A significant ρ-independent terminator exists in the downstream region of the cwlH gene (ΔG = −15.9 kcal/mol). The 0.8-kb transcript shows good correspondence in size from the transcriptional start point to the terminator region of cwlH (about 814 bp), thus indicating monocistronic transcription. TC and CATTCTTAT sequences, which are very similar to the consensus sequences of −35 and −10 sequences (AC and CATANNNTA) (11, 29), were observed at −32 to −31 bp and at −13 to −5 bp, respectively, relative to the transcriptional start point of cwlH (Fig. 1). The GerE consensus sequence (TPuGGPy [Pu, purine; Py, pyrimidine]) was also observed in the region from −152 to −148 bp (TAGGT in Fig. 1). These results confirmed that the cwlH gene is transcribed by EςK RNA polymerase and regulated by GerE.

FIG. 5.

Determination of transcriptional start sites by primer extension analysis. Total RNAs (50 μg) at t9 from B. subtilis 168 (W), 1S38 (ςK−), and 1G12 (GerE−) were used as RNA samples. Signals were detected with 32P-labeled primer PEH1. Dideoxy DNA sequencing reaction mixtures with the same primer were electrophoresed in parallel (lanes G, A, T, and C). The arrows indicate the nucleotide at the transcriptional start site. The nucleotide sequence of the transcribed strand is given beside the sequence ladder.

Production of the CwlH protein during the late sporulation phase.

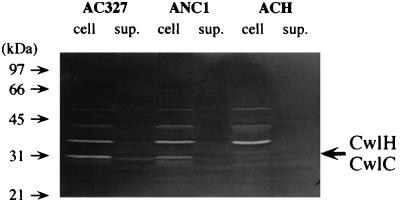

Since the cwlH gene is expressed during the late sporulation phase, surface proteins were extracted in that phase from strains AC327, ANC1 (cwlC), and ACH (cwlC cwlH) and analyzed by zymography (Fig. 6). The wild-type strain gave a cell wall hydrolyzing band corresponding to a molecular size of 28 kDa. Since CwlC is a 28-kDa polypeptide, the size being very similar to that of CwlH, the cwlC gene was disrupted and then analyzed by zymography. A 28-kDa band was still observed, but to a much lesser extent. For the cwlC cwlH mutant, however, no 28-kDa band was detected. Therefore, the 28-kDa band corresponded to CwlH.

FIG. 6.

Zymographic analysis of cell extracts and culture supernatants of B. subtilis AC327 (wild type), ANC1 (cwlC), and ACH (cwlC cwlH) cells. Cultures at t10 were centrifuged, and then the supernatants (sup.) of the cultures (2 ml of each) and SDS extracts of the pellets were applied on a 12% polyacrylamide gel containing 0.1% B. subtilis cell wall. The cell wall lytic bands of CwlH and CwlC overlapped, as indicated by an arrow. Standard size markers are shown on the left.

Role of CwlH in cell morphology.

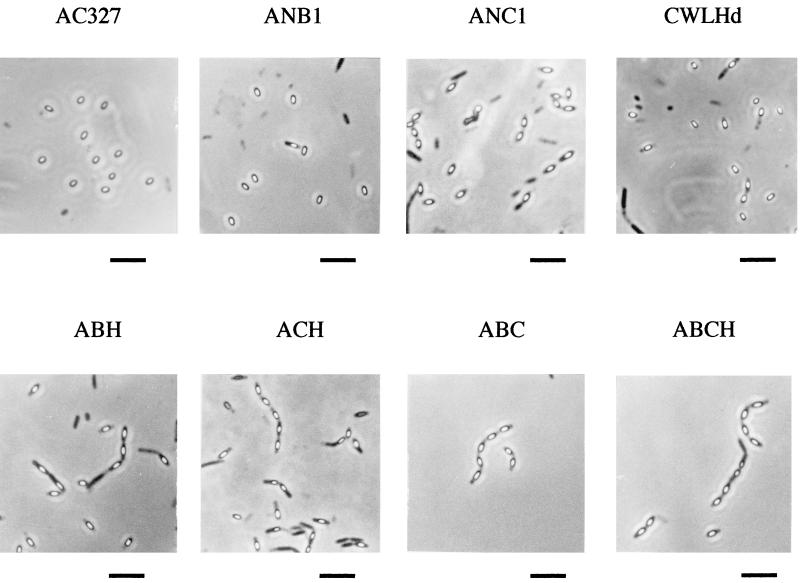

Cell wall hydrolases play various roles in cell morphology, but the role of CwlH has not been determined. CwlH disruption affected neither vegetative cell growth, sporulation frequency, nor germination frequency (31). Since the cwlH gene is expressed during the late stage of sporulation, we investigated the sporulation and germination more precisely with multiple combinations of mutations of cell wall hydrolase genes. Mother cell lysis was blocked strongly by the cwlH cwlC double mutation but weakly by the cwlH cwlB double mutation (Fig. 7). The single cwlH, cwlC, and cwlB mutations did not affect mother cell lysis. The combined effect of CwlH and CwlC is very similar to that of CwlB and CwlC (Fig. 7) reported by Smith and Foster (47).

FIG. 7.

Phase-contrast micrographs of B. subtilis AC327 (wild type), ANB1 (cwlB), ANC1 (cwlC), CWLHd (cwlH), ABH (cwlB cwlH), ACH (cwlC cwlH), ABC (cwlB cwlC) and ABCH (cwlB cwlC cwlH) cells after 24 h incubation in DSM medium at 37°C. Bars, 10 μm.

DISCUSSION

The CwlH protein exhibited extensive amino acid sequence similarity with class I (CwlA type) N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine amidases (Fig. 8). XlyA, XlyB, and BlyA are autolysins of phages PBS1 and SPβ (24, 36, 5). CwlA is assumed to be a phage lysin, because the cwlA gene is located in the skin element (17, 28). In contrast to these phage lysins, CwlH plays a role in mother cell lysis in concert with CwlC, and this is exceptional in class I, because CwlH is produced during the life cycle and has a specific function in cells (Fig. 7). The catalytic domains of class I amidases are located in the N-terminal region, and the amino acid sequences of the C-terminal domains are also very similar to each other except that of BlyA (Fig. 8). Recently, Regamy and Karamata reported that BlyA bound to cell wall very strongly and that it was difficult to release the enzyme from the cell wall with a 5 M LiCl solution (36). This property probably depends on the large difference in the C-terminal amino acid sequence between BlyA and other class I amidases. CwlH exhibits a broad substrate specificity, including hydrolyzing activity for spore cortex (31), which was also found for CwlA and CwlC (9, 16). It is interesting that CwlH is able to hydrolyze immature cortex without muramic acid lactam (31).

FIG. 8.

Alignment of amino acid sequences of class I N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine amidases. CwlA is a deduced phage lysin (17, 27), XlyA and XlyB are phage lysins from PBS1 (24, 5), and BlyA is a phage lysin from SPβ (36). Asterisks indicate identical amino acids among the five amidases in class I. Dashes indicate the introduction of gaps in the alignment, and numbers on the left are with respect to the N-terminal amino acid of each amidase.

The cwlH gene is transcribed by EςK RNA polymerase and affected by GerE (Fig. 4). The cwlC gene is also transcribed by EςK RNA polymerase and affected by GerE (43), and the gene product also plays a role in mother cell lysis in concert with CwlH or CwlB (Fig. 7). The major autolysin (CwlB [LytC]) is produced actively at the end of the exponential growth phase (19, 22) and remains until the late stationary phase (18) and also until the late sporulation phase (Fig. 6 and reference 10). In the late sporulation phase, CwlC is the major hydrolytic enzyme, as judged by zymography, CwlB and CwlH being minor ones (Fig. 6 and reference 10). The results correspond well with the effects of these proteins on mother cell lysis. The total activity of these three peptidoglycan hydrolases may be most important. However, we are unable to eliminate the possibility that the enzymatic property of CwlC in concert with CwlB or CwlH is most important for mother cell lysis.

Combined effects of cell wall and cortex hydrolases are often found for cellular functions. Cell separation is greatly affected by a combination of two endopeptidases (14, 26, 32). Vegetative cell lysis is affected by the major autolysin, CwlB (3, 18, 46), and greatly by four autolysins, including minor ones (CwlF [LytE] and CwlE [LytF]) (26). Motility and cell wall turnover were also affected by combinations of cell wall hydrolases (27, 34, 46), and recently germination was found to be completely blocked with the lack of two deduced class II amidases (15). The combined effect on mother cell lysis observed in this study further supports the idea that peptidoglycan and cortex hydrolases play essential roles in cellular functions in concert.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Tatsuya Fukushima for determination of the substrate bond specificity of the enzyme.

This research was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas (no. 296) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture and by grant JSPS-RFTF96L00105 from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anagnostopoulos C, Spizizen J. Requirement for transformation in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1961;81:741–746. doi: 10.1128/jb.81.5.741-746.1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ayusawa D, Yoneda Y, Yamane K, Maruo B. Pleiotropic phenomena in autolytic enzyme(s) content, flagellation, and simultaneous hyperproduction of extracellular α-amylase and protease in a Bacillus subtilis mutant. J Bacteriol. 1975;124:459–469. doi: 10.1128/jb.124.1.459-469.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackman S, Smith T J, Foster S J. The role of autolysins during vegetative growth of Bacillus subtilis 168. Microbiology. 1998;144:73–82. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-1-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canosi U, Morelli G, Trautner T A. The relationship between molecular structure and transformation efficiency of some Streptococcus aureus plasmids isolated from Bacillus subtilis. Mol Gen Genet. 1978;166:259–267. doi: 10.1007/BF00267617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.da Silva E, Longchamp P F, Karamata D. Abstracts of the 9th International Conference on Bacilli. Lausanne, Switzerland: Universite de Lausanne; 1997. Identification of XlyB, the second lytic enzyme of the defective prophage PBSX, abstr. B25. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doyle R J, Koch A L. The functions of autolysins in the growth and division of Bacillus subtilis. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1987;15:169–222. doi: 10.3109/10408418709104457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fein J E. Possible involvement of bacterial autolysin enzymes in flagellar morphogenesis. J Bacteriol. 1979;137:933–946. doi: 10.1128/jb.137.2.933-946.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fein J E, Rogers H J. Autolytic enzyme-deficient mutants of Bacillus subtilis 168. J Bacteriol. 1976;127:1427–1442. doi: 10.1128/jb.127.3.1427-1442.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foster S J. Cloning, expression, sequence analysis and biochemical characterization of an autolytic amidase of Bacillus subtilis 168 trpC2. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:1987–1998. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-8-1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foster S J. Analysis of the autolysins of Bacillus subtilis 168 during vegetative growth and differentiation by using renaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:464–470. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.2.464-470.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haldenwang W G. The sigma factors of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:1–30. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.1-30.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herbold D R, Glaser L. Bacillus subtilis N-acetylmuramic acid l-alanine amidase. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:1676–1682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Höltje J-V, Tuomanen E I. The murein hydrolases of Escherichia coli: properties, functions and impact on the course of infections in vivo. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:441–454. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-3-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishikawa S, Hara Y, Ohnishi R, Sekiguchi J. Regulation of a new cell wall hydrolase gene, cwlF, which affects cell separation in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2549–2555. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.9.2549-2555.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishikawa S, Yamane K, Sekiguchi J. Regulation and characterization of a newly deduced cell wall hydrolase gene (cwlJ) which affects germination of Bacillus subtilis spores. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1375–1380. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.6.1375-1380.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuroda A, Asami Y, Sekiguchi J. Molecular cloning of a sporulation-specific cell wall hydrolase gene of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6260–6268. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.19.6260-6268.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuroda A, Sekiguchi J. Cloning, sequencing and genetic mapping of a Bacillus subtilis cell wall hydrolase gene. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:2209–2216. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-11-2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuroda A, Sekiguchi J. Molecular cloning and sequencing of a major Bacillus subtilis autolysin gene. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:7304–7312. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.22.7304-7312.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuroda A, Sekiguchi J. High-level transcription of the major Bacillus subtilis autolysin operon depends on expression of the sigma D gene and is affected by a sin (flaD) mutation. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:795–801. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.3.795-801.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kunst F, et al. The complete genome sequence of the Gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature. 1997;390:249–256. doi: 10.1038/36786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lazarevic V, Margot P, Soldo B, Karamata D. Sequencing and analysis of the Bacillus subtilis lytRABC divergon: a regulatory unit encompassing the structural genes of the N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine amidase and its modifier. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:1949–1961. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-9-1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leclerc D, Asselin A. Detection of bacterial cell wall hydrolases after denaturating polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Can J Microbiol. 1989;35:749–753. doi: 10.1139/m89-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Longchamp P F, Mauël C, Karamata D. Lytic enzymes associated with defective prophages of Bacillus subtilis: sequencing and characterization of the region comprising the N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine amidase gene of prophage PBSX. Microbiology. 1994;140:1855–1867. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-8-1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Margot P, Mauël C, Karamata D. The gene of the N-acetylglucosaminidase, a Bacillus subtilis cell wall hydrolase not involved in vegetative cell autolysis. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:535–545. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Margot P, Pagni M, Karamata D. Bacillus subtilis 168 gene lytF encodes a γ-d-glutamate-meso-diaminopimelate muropeptidase expressed by the alternative vegetative sigma factor, ςD. Microbiology. 1999;145:57–65. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-1-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Margot P, Wahlen M, Gholamhuseinian A, Piggot P, Karamata D. The lytE gene of Bacillus subtilis 168 encodes a cell wall hydrolase. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:749–752. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.3.749-752.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mizuno M, Masuda S, Takemaru K, Hosono S, Sato T, Takeuchi M, Kobayashi Y. Systematic sequencing of the 283 kb 210°–232° region of the Bacillus subtilis genome containing the skin element and many sporulation genes. Microbiology. 1996;142:3103–3111. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-11-3103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moran C P., Jr . RNA polymerase and transcription factors. In: Sonenshein A L, Hoch J A, Losick R, editors. Bacillus subtilis and other gram-positive bacteria. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 653–667. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moriyama R, Hattori A, Miyata S, Kudoh S, Makino S. A gene (sleB) encoding a spore cortex-lytic enzyme from Bacillus subtilis and response of the enzyme to l-alanine-mediated germination. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6059–6063. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.20.6059-6063.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nugroho, F. A., H. Yamamoto, and J. Sekiguchi. Unpublished data.

- 32.Ohnishi R, Ishikawa S, Sekiguchi J. Peptidoglycan hydrolase LytF plays a role in cell separation with CwlF during vegetative growth of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3178–3184. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.10.3178-3184.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pooley H M, Karamata D. Genetic analysis of autolysin-deficient and flagellaless mutants of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1984;160:1123–1129. doi: 10.1128/jb.160.3.1123-1129.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rashid M H, Kuroda A, Sekiguchi J. Bacillus subtilis mutant deficient in the major autolytic amidase and glucosaminidase is impaired in motility. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1993;112:135–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb06438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rashid M H, Mori M, Sekiguchi J. Glucosaminidase of Bacillus subtilis: cloning, regulation, primary structure and biochemical characterization. Microbiology. 1995;141:2391–2404. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-10-2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Regamey A, Karamata D. The N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine amidase encoded by the Bacillus subtilis 168 prophage SPβ. Microbiology. 1998;144:885–893. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-4-885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rogers H J, Perkins H R, Ward J B. Microbial cell walls and membranes. London, England: Chapman and Hall; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rogers H J, Taylor C, Rayter S, Ward J B. Purification and properties of autolytic endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase and the N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine amidase from Bacillus subtilis strain 168. J Gen Microbiol. 1984;130:2395–2402. doi: 10.1099/00221287-130-9-2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schaeffer P, Millet J, Aubert J P. Catabolite repression of bacterial sporulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1965;54:704–711. doi: 10.1073/pnas.54.3.704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sekiguchi J, Akeo K, Yamamoto H, Khasanov F K, Alonso J C, Kuroda A. Nucleotide sequence and regulation of a new putative cell wall hydrolase gene, cwlD, which affects germination in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5582–5589. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.19.5582-5589.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sekiguchi J, Ezaki B, Kodama K, Akamatsu T. Molecular cloning of a gene affecting the autolysin level and flagellation in Bacillus subtilis. J Gen Microbiol. 1988;134:1611–1621. doi: 10.1099/00221287-134-6-1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sekiguchi, J., S. Ishikawa, and H. Yamamoto. Unpublished data.

- 44.Shimotsu H, Henner D J. Modulation in Bacillus subtilis levansucrase gene expression by sucrose, and regulation of the steady-state mRNA level by sacU and sacQ genes. J Bacteriol. 1986;168:380–388. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.1.380-388.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stockman G D, Höltje J-V. Microbial peptidoglycan (murein) hydrolases. In: Ghuysen J-M, Hakenbeck R, editors. Bacterial cell wall. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1994. pp. 131–166. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith T J, Blackman S A, Foster S J. Peptidoglycan hydrolases of Bacillus subtilis 168. Microb Drug Resist. 1996;2:113–118. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1996.2.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith T J, Foster S J. Characterization of the involvement of two compensatory autolysins in mother cell lysis during sporulation of Bacillus subtilis 168. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3855–3862. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.13.3855-3862.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vagner V, Dervyn E, Ehrlich S D. A vector for systematic gene inactivation in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology. 1998;144:3097–3104. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-11-3097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yamanaka K, Araki J, Takano M, Sekiguchi J. Characterization of Bacillus subtilis mutants resistant to cold shock-induced autolysis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1977;150:267–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]