Abstract

Fibrillar protein aggregates are characteristic of neurodegenerative diseases but represent difficult targets for ligand design, because limited structural information about the binding sites is available. Ligand-based virtual screening has been used to develop a computational method for the selection of new ligands for Aβ(1–42) fibrils, and five new ligands have been experimentally confirmed as nanomolar affinity binders. A database of ligands for Aβ(1–42) fibrils was assembled from the literature and used to train models for the prediction of dissociation constants based on chemical structure. The virtual screening pipeline consists of three steps: a molecular property filter based on charge, molecular weight, and logP; a machine learning model based on simple chemical descriptors; and machine learning models that use field points as a 3D description of shape and surface properties in the Forge software. The three-step pipeline was used to virtually screen 698 million compounds from the ZINC15 database. From the top 100 compounds with the highest predicted affinities, 46 compounds were experimentally investigated by using a thioflavin T fluorescence displacement assay. Five new Aβ(1–42) ligands with dissociation constants in the range 20–600 nM and novel structures were identified, demonstrating the power of this ligand-based approach for discovering new structurally unique, high-affinity amyloid ligands. The experimental hit rate using this virtual screening approach was 10.9%.

Introduction

Amyloidogenic proteins are a class of biomolecules that self-assemble into fibrillar structures with a cross-β sheet structure. The formation of insoluble protein aggregates from amyloidogenic proteins is a hallmark of many diseases, most prominently neurodegenerative diseases.1−3 The most common neurodegenerative disease, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), is characterized by the deposition of amyloid plaques comprised of misfolded amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) comprised of misfolded tau protein.4,5 While the 40-residue Aβ peptide, Aβ(1–40), is the most abundant isoform in the brain, the 42-residue Aβ peptide, Aβ(1–42), is the primary component of amyloid plaques found in AD.6 These peptides are generated by cleavage of the integral membrane protein amyloid precursor protein (APP).7 However, the precise physiological role of APP and Aβ peptides, and their role in disease onset and progression, is poorly understood.8,9

The only current method to definitively diagnose AD is through the post-mortem histopathological identification of Aβ plaques.10 Due to the limited accessibility of living brains, AD is diagnosed in the clinic using cognitive tests alongside a panel of imaging or biofluid tests.11 However, these diagnostic methods do not reliably diagnose AD until extensive neuronal damage has already occurred.10 Accurate and early diagnosis is essential to ensure that patients receive appropriate disease management and to accurately recruit clinical trial populations when developing disease therapeutics.12 One promising diagnostic strategy is the detection of amyloid plaques in vivo using positron emission tomography.13−17 Several radiolabeled PET probes have been reported in the literature for imaging amyloid plaques.18−21 Some PET probes have been approved for clinical use, but show insufficient sensitivity and specificity to definitively diagnose AD by themselves.17,22,23 Amyloid ligands are also useful for ex vivo applications including for imaging and characterizing amyloid deposits and for monitoring protein aggregation.24,25 For these applications, amyloid ligands that bind selectively to target fibrils with a high affinity are needed.

To date, amyloid ligands have primarily been discovered from high-throughput screening efforts combined with structure–activity relationship (SAR) studies. These approaches have identified new structural classes of amyloid ligands and have generated high-affinity binders, yet are resource and time intensive. Virtual screening (VS) is one method that can improve the efficiency of discovering active ligands.26−28 VS is a computational technique that aims to identify active molecules by using knowledge about either the target (structure-based VS) or known active molecules (ligand-based VS).29,30 Structure-based VS typically requires high-resolution structures of the target binding site. Structural information has only recently become available for amyloid fibrils with advancements in cryo-EM technology.31,32 However, the binding of amyloid ligands to fibrils is not a straightforward process: multiple binding sites exist, and direct interactions between multiple ligands can occur.33−39 Previous efforts have discovered amyloid-binding ligands from blind docking studies,40 although results from this approach do not always reflect experimental results.41,42 Structural knowledge of ligand binding sites is therefore required for accurate structure-based VS, and this remains an unsolved problem for amyloid fibrils.

Ligand-based VS requires no knowledge of the target’s structure or binding sites.43−46 Instead, structure–activity data of known actives (and inactives) are used to predict binding. Previous studies have developed ligand-based pharmacophores to model the binding of stilbene and flavone analogues to amyloid fibrils.47,48 Because of the large quantity of reported binding data for amyloid ligands, a ligand-based VS method for finding novel high-affinity ligands is appealing. Here we describe a three-step pipeline using ligand-based VS methods to identify novel high-affinity amyloid ligands. The approach has successfully identified five new ligands exhibiting nanomolar binding affinities for Aβ(1–42) fibrils.

Approach

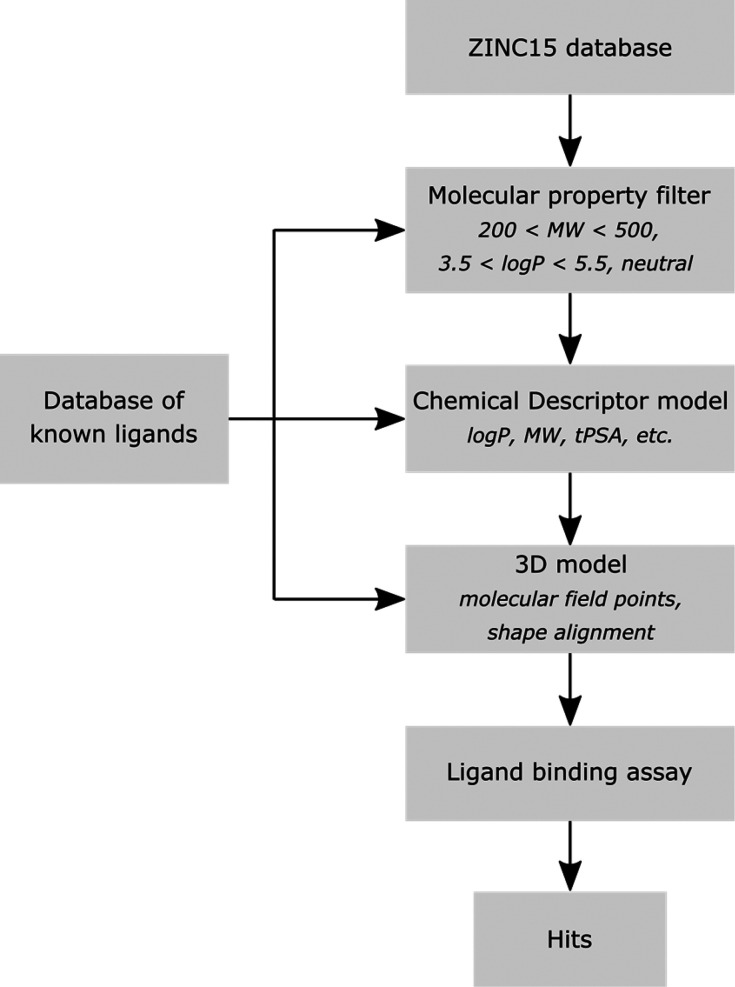

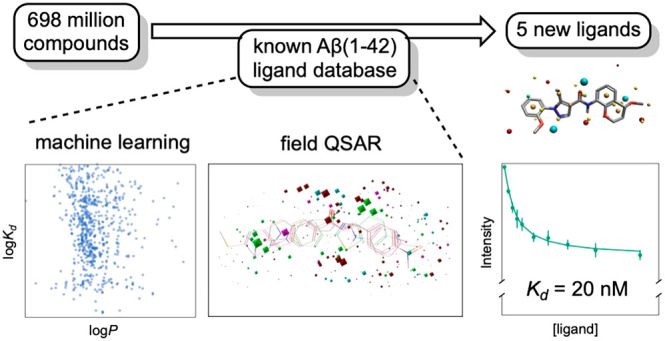

The steps of the pipeline for the discovery of new amyloid ligands using ligand-based VS are illustrated in Figure 1. First, a database of potential ligands is filtered based on logP (the partition coefficient between octan-1-ol and water), molecular weight, and charge. Then machine learning is used to develop a model that describes the dissociation constants of known ligands using multiple chemical descriptors. Finally, a more complicated model that incorporates information about the 3D molecular fields of ligands is trained to predict the dissociation constants of known ligands. In this paper, we describe the development of VS models based on a data set of known Aβ(1–42) ligands and the application of these models to screen 698 million compounds from the ZINC15 database.49 A structurally diverse subset of the most promising leads identified by the ligand-based VS was experimentally assayed for binding to Aβ(1–42) fibrils to discover a number of new amyloid ligands (hits).

Figure 1.

Overview of the three-step ligand-based VS pipeline used. A molecular property filter was applied to the ZINC15 database to select a subset of compounds that are similar to known amyloid ligands. This subset was then screened through two models developed by using the binding affinities of known amyloid ligands in the FBH database. The ligands with the highest predicted affinities obtained from the VS models were then experimentally screened to identify hits.

Results and Discussion

Ligand Database

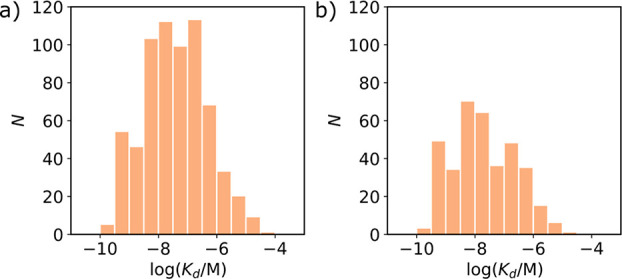

We first compiled a data set of experimentally determined dissociation constants for ligand binding to Aβ(1–42) fibrils.50−183 This initial data set contained a total of 707 unique ligands, which were structurally diverse and exhibited micromolar to subnanomolar dissociation constants (Kd) (Table S3, Table S4). Of these ligands, 44 had Kd values reported as limiting values (e.g., Kd > 1 μM). Figure 2a illustrates the distribution of dissociation constants measured for the remaining 663 ligands. Many of these ligands have been reported to target different binding sites on Aβ(1–42) fibrils,33−38,50 and in order to construct an accurate predictive model for ligand-based VS, only ligands that share a common binding site should be used.

Figure 2.

Frequency distributions showing the number of ligands (N) with experimentally determined Kd values for binding to (a) Aβ(1–42) fibrils and (b) the FBH site on Aβ(1–42) fibrils. Where multiple Kd values were reported for a single ligand, the average value was used.

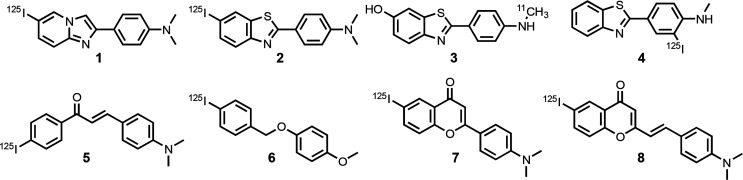

The best way to identify ligands that bind to the same site is from competition assays, and the most common competition assay used to study binding to Aβ(1–42) fibrils involves the displacement of radiolabeled fused 6,5-benzoheterocycles (FBH) (see ligands 1–4 in Figure 3). The dissociation constants measured for ligands 1–4 in direct binding assays are the same as the dissociation constants measured by competition assays using any pair of these four ligands.51−66 This result indicates that ligands 1–4 all bind at the same sites on the fibrils, which we designate the FBH site. Similarly, dissociation constants measured for ligands 5–8 in direct binding assays are the same as the dissociation constants measured by competition assays with any of ligands 1–4.67−71 We therefore conclude that dissociation constants measured by displacing any of the radiolabeled ligands 1–8 in a competition assay must report on binding to the FBH site.

Figure 3.

Structures of radiolabeled ligands used in competition assays to report on the FBH binding site on Aβ(1–42) fibrils.

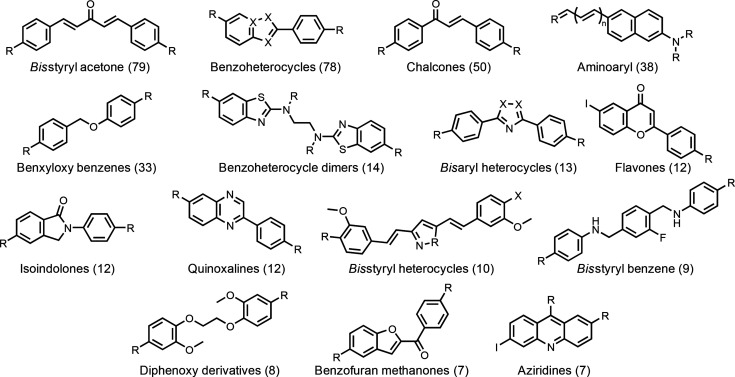

Previous work indicates that there are high-affinity and low-affinity FBH binding sites on Aβ(1–42) fibrils, but the competition assays involving displacement of 1–8 report primarily on the high-affinity site.53,55,124 We identified a total of 388 ligands within the Aβ(1–42) data set that had been characterized using a competition assay against one of 1–8 (Table S3). Of these ligands, 27 had binding constants reported as limiting values. The remaining 361 ligands exhibit a similar range of dissociation constants to that found in the complete 663 ligand data set (compare Figures 2a and 2b), and they have diverse chemical structures (see Figure 4). The database of 388 FBH site ligands therefore constitutes a good starting point for the ligand-based VS pipeline shown in Figure 1.

Figure 4.

Common ligand motifs that bind to the FBH site on Aβ(1–42) fibrils. The number of unique compounds reported for each structural class is shown in brackets. R and X represent sites of structural variation.

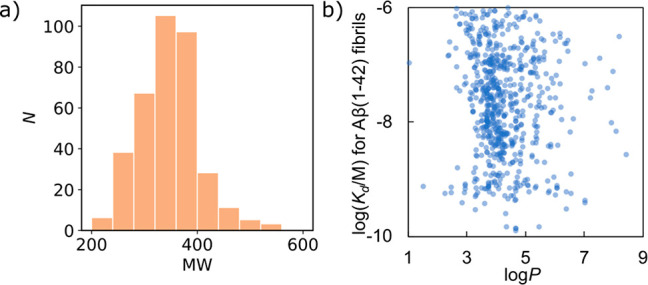

Molecular Property Filter

The first step in the pipeline in Figure 1 is to filter the compounds in the ZINC15 database based on molecular properties. Only two of the ligands in the FBH database contain ionizable functional groups, so all charged compounds were excluded. The molecular weights of the ligands in the FBH database fall in the range 200–500 Da, so a filter was applied to exclude any compounds with a molecular weight outside of this window (Figure 5a). Figure 5b shows that although there is no correlation between binding affinity and logP, there appears to be a cutoff in logP below which there are very few ligands in the database. A third filter was therefore used to exclude compounds with a logP outside the range 3.5 to 5.5, reducing the total number of compounds for screening from 698 million to 63 million.

Figure 5.

Molecular properties of ligands in the FBH database. (a) Frequency distribution of molecular weights. (b) Relationship between Kd and logP values.

Chemical Descriptor Model

The second step in the pipeline in Figure 1 is to build models based on chemical descriptors of the ligands in the FBH database. A total of 45 different descriptors based on 1D compositional properties (e.g., molecular weight), 2D topological properties (e.g., topological polar surface area), and 3D conformational properties (e.g., asphericity) were calculated for each ligand using the python package RDKit.184 In order to obtain the 3D descriptors, a three-dimensional structure was calculated for each ligand using the XedeX conformation hunting algorithm in Forge.185 The Pearson correlation coefficient was less than 0.9 for all pairwise comparisons of the descriptors, which indicates that they can be treated as independent variables. Each set of descriptors X was standardized using eq 1 in order to center the distributions at zero with unit standard deviation.

| 1 |

where μ and σ are the mean and standard deviation of descriptor X across the data set.

Different machine learning methods implemented in SciKit-learn were then used to develop predictive models for the values of log(Kd/M) in the FBH database.186 Machine learning models based on decision trees and boosted trees as well as a support vector machine were implemented in a nested cross-validation (CV) procedure using k-fold validation (k = 5 for both inner and outer loops, see SI).187 Regression models were scored by calculating the mean average error (MAE) between the predicted and experimental values of log(Kd/M). However, 27 dissociation constants were reported as limiting values and could not be readily incorporated into regression models, so classification models were developed by converting the log(Kd/M) of each ligand into a binding class: class 0 for log(Kd/M) ≤ −8, class 1 for −8 < log(Kd/M) ≤ −7, class 2 for −7 < log(Kd/M) ≤ −6, and class 3 for −6 < log(Kd/M). The classification models were scored by calculating the balanced accuracy. The scores for all of the different models are reported in Table 1.

Table 1. Evaluation of Models for Prediction of log(Kd/M) for Ligands in the FBH Databasea.

| classification | regression | |

|---|---|---|

| model | balanced accuracy | MAE |

| random forest | 0.57 | 0.48 |

| extra trees | 0.43 | 0.55 |

| XGBoost188 | 0.52 | 0.51 |

| gradient boosting | 0.58 | 0.48 |

| LightGBM189 | 0.55 | 0.45 |

| histogram-based GB | 0.58 | 0.47 |

| Ada boost190 | 0.46 | 0.63 |

| support vector machine | 0.60 | 0.41 |

| baseline (average) | 1.10 | |

| baseline (randomize) | 0.33 | 2.10 |

Scores are the average of the best models for each pass of the 5-fold outer cross-validation procedure.

The classification models gave balanced accuracy scores of 0.43 to 0.60, all of which represent an improvement on a random reallocation baseline model that gave a balanced accuracy of 0.33. The support vector machine was the highest-scoring classification model, with a balanced accuracy of 0.60. However, the improvement in the balanced accuracy score relative to the baseline model is modest, and since classification models do not predict the values for continuous variables such as log(Kd/M), this approach was not considered further.

All of the regression models outperformed a random reallocation baseline model (MAE = 2.10) and a baseline model that used the average value of log(Kd/M) for all ligands (MAE = 1.10). The support vector machine was the highest-scoring regression model, with an MAE of 0.41. The random forest, extra trees, and gradient boosted models also scored relatively well. An advantage of the random forest model is that the relative importance of different chemical descriptors can be evaluated (see SI). This analysis suggested that the number of aromatic rings is the most important feature for determining log(Kd/M), whereas the number of aliphatic rings and aliphatic chains has little influence. Based on the results in Table 1, the regression support vector machine model was selected as the chemical descriptor model for the second step of the pipeline in Figure 1. The 63 million compounds selected from the ZINC15 database using the molecular property filter were predicted to have dissociation constants in the range 4.1 < −log(Kd/M) < 10.2 using the support vector machine model. A total of 10,000 compounds were predicted to have values of −log(Kd/M) > 9.8, and these compounds were selected for further analysis in the next step.

3D Model

The third step of the pipeline in Figure 1 is the development of a model using 3D descriptions of the ligands in the FBH database. Cresset field points, which describe the local extrema of the electrostatic, van der Waals, and hydrophobic potential fields, were calculated for a diverse set of conformations of each ligand using the extended electronic distribution (XED) molecular mechanics force field in the Forge software.185,191 These field points were used to construct 3D models by using the process outlined in Figure 6. First, a small number of high-affinity reference ligands that have structural cores representative of the entire database were chosen. Field points were used to align multiple conformers of the reference ligands to one another to generate a set of templates. These field point templates were scored based on the shape and field similarity of the aligned ligands, and the best template was selected and used to align all remaining ligands in the database. Finally, a quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR) model was generated from the relationship between the experimentally measured log(Kd/M) and the field point distribution of each ligand. This model provides the basis for predicting the affinity of different compounds on a virtual screen.

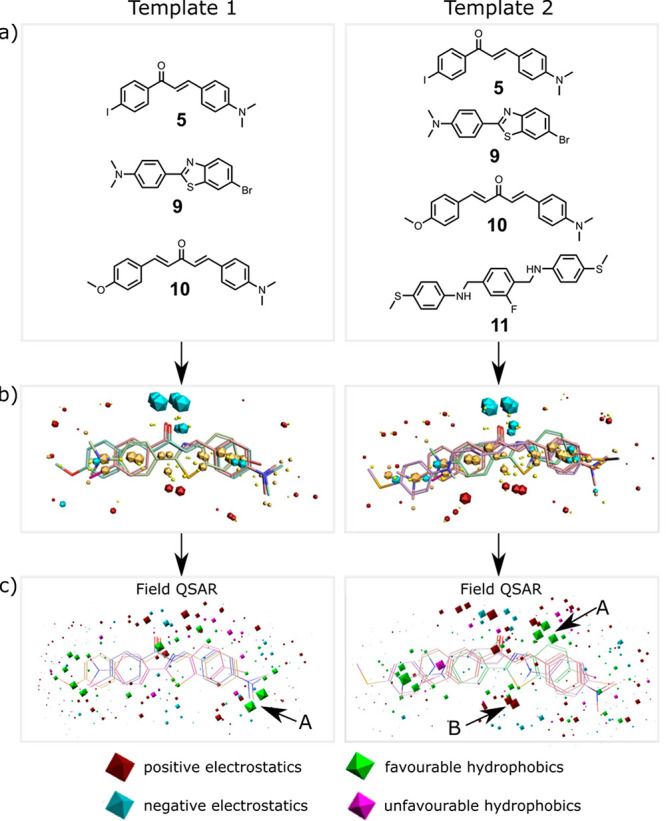

Figure 6.

Field point templates. (a) Reference ligands 5, 9, and 10 were used to construct Template 1, and 5, 9, 10, and 11 were used to construct Template 2. (b) 3D alignment of the reference ligands showing the field points (blue: negative electrostatic potential; red: positive electrostatic potential; orange: high hydrophobicity; yellow: van der Waals interactions). (c) Field-QSAR models shown relative to the reference ligands: blue sites describe regions where more negative or less positive electrostatic field coefficients favor affinity; red sites describe regions where less negative or more positive electrostatic field coefficients favor affinity; green sites describe regions where hydrophobes favor affinity; pink sites describe regions where hydrophobes disfavor affinity. The sites labeled A represent regions where hydrophobic interactions are important, and the site labeled B highlights important electrostatic interactions.

Ligands 5, 9, 10, and 11 shown in Figure 6a were used to construct templates because they have nanomolar binding affinities and structural cores that occur with a high frequency in the FBH database. It was possible to align all four ligands to create a template, but high-energy conformations were required (Template 2 in Figure 6). If ligand 11 was excluded, it would be possible to align the other three ligands in low-energy conformations (Template 1 in Figure 6). Structurally similar ligands from the FBH database were then aligned to these templates: for Template 1, benzoheterocycles, aminoaryls, flavones, quinoxalines, benzyloxybenzenes, chalcones, bis-aryl heterocycles, and bis-styryl acetones; for Template 2, bis-styryl heterocycles and bis-styryl benzenes were added (see Figure 4). Alignments were scored based on the similarity of the shape and field points of the aligned compound to the template. Alignments were manually reviewed to ensure consistency within each structural class. Certain functionalities proved to be challenging to align. For example, large numbers of alignments with similar scores but different field point distributions were generated by ligands with ethylene glycol chains or polyene linkers. These compounds were discarded from the model development. After refining the aligned data set, a total of 212 ligands were aligned to Template 1 and 222 ligands were aligned to Template 2.

For each Template, the ligands were partitioned into a training set (80%) and a test set (20%) for model development. Partitioning was activity-stratified and performed manually to ensure that each of the ligand structural classes shown in Figure 4 was represented in both training and test sets. Five different QSAR models were constructed for each template using Forge: random forest, support vector machine, relevance vector machine, k-nearest neighbors, and a regression method based on partial least-squares analysis of field points (field QSAR).192 A k-fold cross-validation procedure (k = 5) was used for the random forest, support vector machine, and relevance vector machine models, and a leave-one-out cross-validation procedure was used for the k-nearest neighbors and field QSAR models. Model performance was evaluated using the regression coefficient r2 for the training and test sets and the cross-validation regression coefficient q2 for the training set. The results are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Regression Coefficients (r2) and Cross-Validation Regression Coefficients (q2) for the Forge Models.

| template | model | cross-validation q2 | training set r2 | test set r2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Template 1 | field QSAR | 0.53 | 0.83 | 0.43 |

| random forest | 0.48 | 0.93 | 0.57 | |

| support vector machine | 0.50 | 0.99 | 0.49 | |

| k-nearest neighbors | 0.51 | a | 0.64 | |

| relevance vector machine | 0.46 | 0.86 | 0.54 | |

| Template 2 | field QSAR | 0.53 | 0.81 | 0.38 |

| random forest | 0.43 | 0.93 | 0.28 | |

| support vector machine | 0.56 | 0.99 | 0.50 |

Not applicable.

The performances of different models were very similar for the training and cross-validation sets. For the test set, the highest r2 values were obtained using the random forest model for Template 1 and the support vector machine model for Template 2. These models together with the field QSAR models were used to screen the 10,000 compounds that were selected from the ZINC15 database using chemical descriptors. Although the test set r2 values for the field QSAR models were lower, these models are useful because they identify the interactions that are important for determining ligand binding affinity. Figure 6c shows the two field QSAR models. The two templates show clear differences in the most important sites identified for hydrophobic (arrow A) and electrostatic (arrow B) interactions.

The 10,000 compounds were first filtered using the field QSAR distance-to-model score, which is based on how well the field points of the compound are represented in the models illustrated in Figure 6c. Only compounds with a good or excellent distance-to-model score were considered further. These compounds were then separately ranked for each template by averaging the values of log(Kd/M) predicted by two models, i.e., random forest and field QSAR for Template 1 and support vector machine and field QSAR for Template 2. The 50 compounds with the lowest average log(Kd/M) for each template were selected, and 46 of these 100 compounds were purchased for experimental screening based on commercial availability and scaffold diversity (see SI). While previously reported Aβ(1–42) ligands in the literature (Figure 4) are generally rigid and flat, many of the hits from the virtual screening procedure contained flexible aliphatic chains and rings.

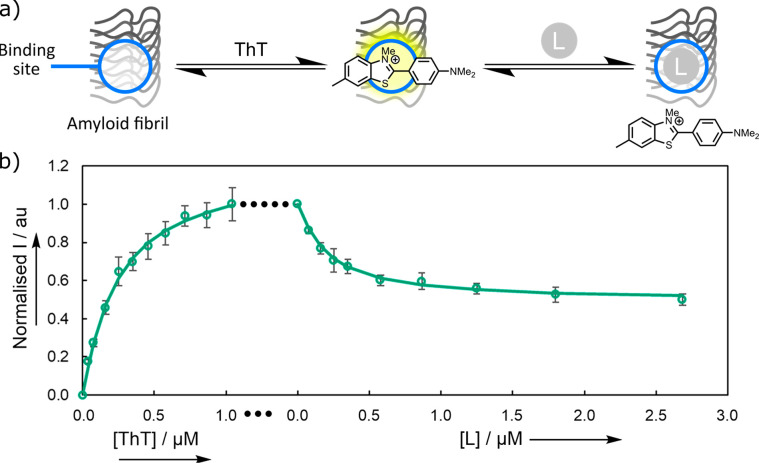

Experimental Binding Assays

Thioflavin T (ThT) competition assays were used to screen the 46 compounds selected from the VS pipeline (Figure 7a). When ThT binds to Aβ(1–42) fibrils, there is a large enhancement in the intensity of the fluorescence emission and a shift in the emission wavelength. Addition of a second nonfluorescent ligand L that binds to Aβ(1–42) fibrils at a ThT binding site will lead to a decrease in fluorescence intensity due to the displacement of the ThT. Titration of the second competing ligand (L) into a mixture of ThT and Aβ(1–42) fibrils therefore allows determination of the binding affinity. Figure 7b shows an example of this competition assay. When ThT binds to Aβ(1–42) fibrils in the first phase of the experiment, there is a characteristic increase in the fluorescence intensity. Addition of the competing ligand in the second phase of the experiment leads to a decrease in fluorescence intensity, due to displacement of the ThT from roughly half of the binding sites (Figure 7b).

Figure 7.

(a) Competition binding assay using thioflavin T (ThT). There is an increase in the fluorescence intensity when ThT binds to an amyloid fibril. Binding of a competing ligand L (E570) is detected by the decrease in fluorescence intensity when ThT is displaced. (b) Fluorescence titration of ThT into a solution of Aβ(1–42) fibrils (500 nM) in 1× PBS buffer (pH 7.4, 25 °C), followed by a titration of the competing ligand. Spectra were recorded using λex = 440 nm, and the fluorescence emission was monitored at λem = 483 nm. The experimental measurements are shown as points (error bars represent the 95% confidence interval calculated from at least three independent experiments), and the lines are the best fits to eq 2 with log(Kd(ThT)/M) = −6.7 and log(Kd(L)/M) = −7.6.

Both the free and bound states of ThT fluoresce; therefore, the background fluorescence due to free ThT must be accounted for in analysis of the titration data. In addition, the presence of two different types of binding sites must be considered: S1, which binds both ThT and L, and S2, which is only accessible to ThT.

The intensity of the fluorescence emission (I) is therefore given by eq 2:

| 2 |

where ϵfϕf and ϵbϕb are the products of the UV–vis absorption extinction coefficient and the fluorescence quantum yield for free and bound ThT, respectively, [ThT] is the concentration of free ThT, and [ThT·S1] and [ThT·S2] are the concentrations of ThT bound to S1 and S2, respectively.

The concentration of ThT bound to each site is given by eq 3:

| 3 |

where [Sn] is the concentration of unbound site Sn (n = 1 or 2), and the dissociation constant of ThT, Kd(ThT), is assumed to be the same for both sites.

The concentration of L bound to site S1 is given by eq 4:

| 4 |

where [L] is the concentration of free L, [L·S1] is the concentration of L bound to S1, and Kd is the dissociation constant.

The total concentrations of ThT, [ThT]tot and L, [L]tot are then given by eqs 5 and 6:

| 5 |

| 6 |

The quantity ϵfϕf for ThT was measured from a dilution experiment in 1× PBS buffer (pH 7.4, 25 °C), and values of ϵbϕb and Kd(ThT) were found by fitting eqs 2, 3, and 5 to a single-site binding model for the first phase of the experiment illustrated in Figure 7b, i.e., direct titration of ThT into Aβ(1–42) fibrils (−log(Kd/M) = 6.7 ± 0.1; see SI for details).

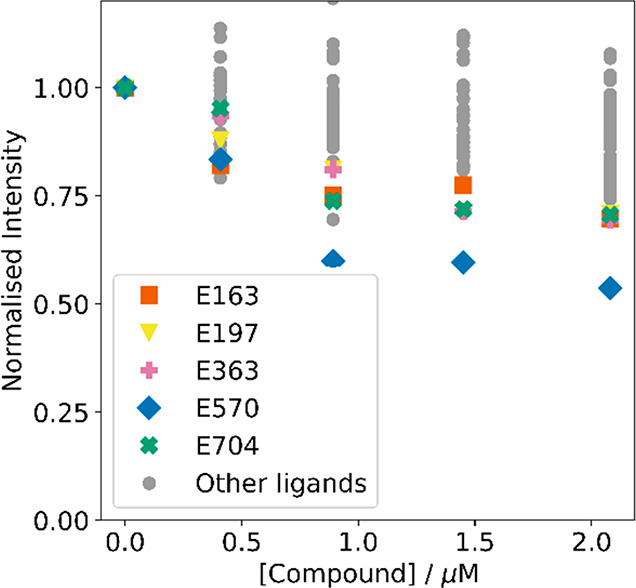

Figure 8 shows the result of titrating 44 of the 46 candidates from the VS into a mixture of Aβ(1–42) fibrils and ThT. The five compounds that displaced the greatest quantity of ThT (E163, E197, E363, E570, and E704) are highlighted as the colored data points in Figure 8, and these compounds were selected for further characterization. The other two candidates from the VS were fluorescent coumarin derivatives, so direct titration into Aβ(1–42) fibrils was used to assay these compounds instead of the competition assay. No binding was detected in these cases (see SI).

Figure 8.

ThT competition assay for 44 compounds from the VS pipeline. Increasing concentrations of each compound were added to Aβ(1–42) fibrils (250 nM) and ThT (1.0 μM) in 1× PBS buffer (pH 7.4, 25 °C). Fluorescence spectra were recorded using λex = 440 nm, and the emission intensity was monitored at λem = 483 nm. Gray data points denote low-affinity compounds that were not investigated further.

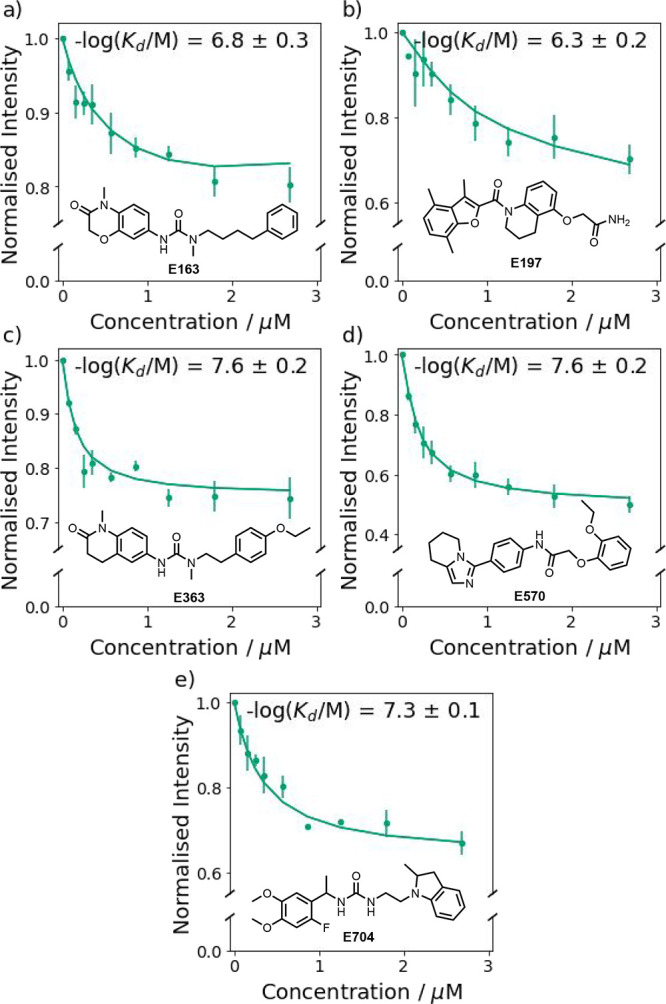

Figure 9 shows the results of titration experiments used to measure the binding affinity of E163, E197, E363, E570, and E704 for Aβ(1–42) fibrils. Fitting 1:1 binding isotherms yielded nanomolar dissociation constants for all five compounds (Table 3, 20–600 nM). The amount of ThT displaced varies from one compound to another, which indicates that the compounds target different subsets of ThT binding sites. E570 displaces about half of the ThT, whereas the other four ligands displace only 20–40% of the bound ThT. One explanation for this result is that the ligands used for model development may bind at more than one site on the fibrils, and the compounds selected by the VS would therefore contain different combinations of features that favor binding at different sites. Partial ligand displacement is a potentially useful feature of these assays that may provide additional information on the nature and distribution of different binding sites that are present on different types of fibril.34

Figure 9.

Fluorescence titration of (a) E163, (b) E197, (c) E363, (d) E570, and (e) E704 into a mixture of Aβ(1–42) fibrils (500 nM) and ThT (1.0 μM) in aqueous 1× PBS buffer (pH 7.4, 25 °C). The spectra were recorded by using λex = 440 nm, and emission was monitored at λem = 483 nm. The experimental measurements are shown as points (error bars represent the 95% confidence interval calculated from at least three independent experiments). The lines are the best fit to eq 2, and the resulting dissociation constants are shown.

Table 3. Dissociation Constants for E163, E197, E363, E570, and E704 Measured by Fluorescence Competition Assays into a Mixture of Aβ(1–42) Fibrils (500 nM) and ThT (1.0 μM) in Aqueous 1× PBS buffer (pH 7.4, 25 °C)a.

| compound | Kd/nM | –log(Kd/M) |

|---|---|---|

| E163 | 200 ± 100 | 6.8 ± 0.3 |

| E197 | 600 ± 300 | 6.3 ± 0.2 |

| E363 | 20 ± 10 | 7.6 ± 0.2 |

| E570 | 20 ± 10 | 7.6 ± 0.2 |

| E704 | 56 ± 6 | 7.3 ± 0.1 |

The spectra were recorded using λex = 440 nm, and emission was monitored at λem = 483 nm. Dissociation constants are given as the average of fits from at least three independent experiments.

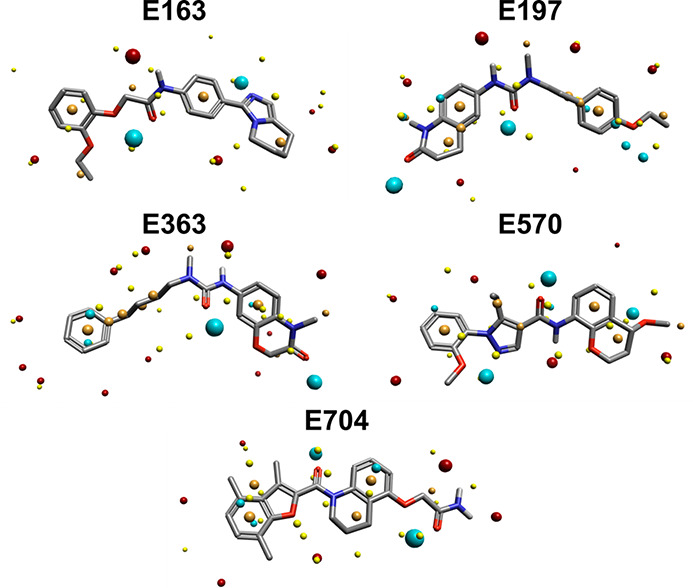

Figure 10 shows the field points for these ligands in the same alignment as Template 2. There is no obvious similarity between the field point distributions, which would be consistent with different binding site preferences and highlights the utility of the 3D models for finding structurally diverse ligands.

Figure 10.

Field points of E163, E197, E363, E570, and E704 aligned to Template 2. Blue field points describe regions of negative electrostatic potential; red field points describe regions of positive electrostatic potential; orange field points describe regions with high hydrophobicity; and yellow field points describe van der Waals interactions.

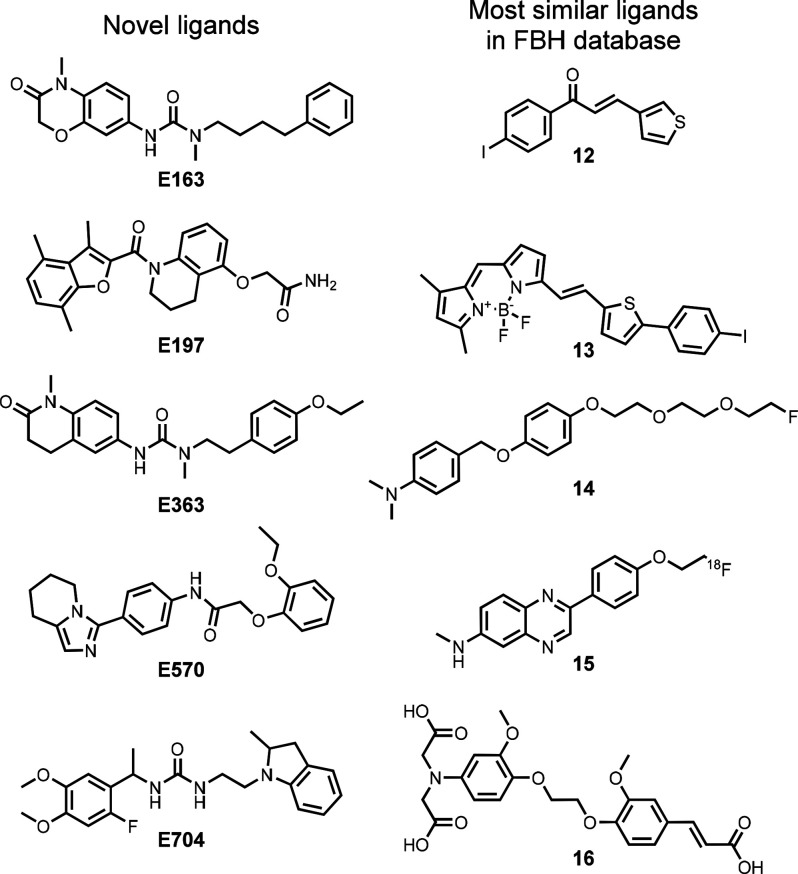

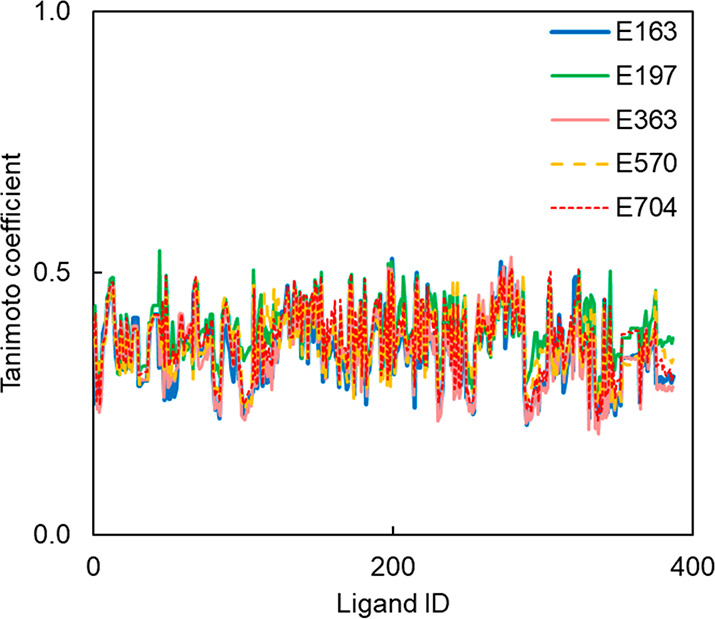

RDKit fingerprints were used to calculate Tanimoto similarity coefficients between each of the five new ligands and each compound in the FBH database.193,194Figure 11 illustrates the results. The maximum values of the similarity coefficients are about 0.5 in all cases, indicating that the newly discovered ligands have chemical structures very different from those of all previously reported Aβ(1–42) ligands. Figure 12 compares the structures of E163, E197, E363, E570, and E704 with the corresponding ligand in the FBH database, which has the highest Tanimoto coefficient.

Figure 11.

Tanimoto similarity coefficients between E163, E197, E363, E570, and E704 and each ligand in the FBH database calculated using RDKit fingerprints.

Figure 12.

Comparison of the chemical structures of the novel ligands identified by the VS pipeline with the chemical structure of the corresponding ligand in the FBH database with the highest Tanimoto similarity coefficient: 0.53 for E163 and 12, 0.54 for E197 and 13, 0.53 for E363 and 14, 0.50 for E570 and 15, and 0.51 for E704 and 16.

Conclusion

Amyloid fibrils present a challenging target for structure-based VS due to the lack of knowledge regarding binding site location and structure. Here, we describe a three-step ligand-based VS approach that exploits the wealth of Aβ(1–42) ligand data in the literature. A data set of 707 Aβ(1–42) fibril-binding ligands was first compiled, of which 388 had binding constants that reported on the same binding site, as determined by ligand competition assays. Key molecular properties required for binding were identified from the FBH database. The 698 million compounds in the ZINC15 database were filtered using charge, molecular weight, and logP, leading to 63 million compounds for further screening. The FBH database was used to train a support vector machine to predict dissociation constants by using computationally inexpensive chemical descriptors. This model was used to select the 10,000 compounds with the highest predicted affinities. The FBH database was used to train 3D models based on field points, which represent a description of surface, shape, and electronic properties.

These models were used to select 100 compounds with the highest predicted binding affinity, and 46 of these were experimentally investigated in fluorescence competition binding assays for Aβ(1–42) fibrils. The five highest affinity ligands all had nanomolar dissociation constants (25–500 nM) without any further structural optimization. The discovery of five new amyloid ligands from an experimental investigation of 46 compounds selected by the ligand-based VS pipeline represents a 10.9% hit rate. The VS pipeline also generated structurally diverse compounds that represent novel scaffolds for Aβ(1–42) ligands, which have not previously been reported.195 The conformational flexibility of the new ligands also suggests that the rigid, highly conjugated structures of the previously reported Aβ(1–42) ligands are not strictly required. The approach is not restricted to Aβ(1–42) ligands. For example, application of this methodology to in vivo data on ligand binding would be of particular interest to accelerate the discovery of novel high-affinity ligands for the biological fibrils associated with disease. New ligands for protein aggregates have a number of potential applications in disease diagnosis, including use as in vivo imaging agents or identification of different fibril polymorphs in tissue samples.

Acknowledgments

We thank Cresset Inc. (UK) for providing an academic version of Forge, and the Cambridge Trust Prince of Wales Scholarship for funding T.S.C. We thank the EPSRC Underpinning Multi-User Equipment Call (EP/P030467/1). We thank Rhys Kilian for providing feedback on the python code written for the chemical descriptor model.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.3c03749.

Details of the methods used to construct the virtual screening models, experimental details on preparation and characterization of protein aggregates, chemical structures of all ligands, and titration data (PDF)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Chiti F.; Dobson C. M. Protein Misfolding, Amyloid Formation, and Human Disease: A Summary of Progress Over the Last Decade. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017, 86 (1), 27–68. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061516-045115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl F. U. Protein Misfolding Diseases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017, 86, 21–26. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061516-044518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney P.; Park H.; Baumann M.; Dunlop J.; Frydman J.; Kopito R.; McCampbell A.; Leblanc G.; Venkateswaran A.; Nurmi A.; Hodgson R. Protein Misfolding in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Implications and Strategies. Transl. Neurodegener. 2017, 6 (1), 6. 10.1186/s40035-017-0077-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaquer-Alicea J.; Diamond M. I. Propagation of Protein Aggregation in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2019, 88 (1), 785–810. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061516-045049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James B. D.; Bennett D. A. Causes and Patterns of Dementia: An Update in the Era of Redefining Alzheimer’s Disease. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2019, 40 (1), 65–84. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. I. A.; Linse S.; Luheshi L. M.; Hellstrand E.; White D. A.; Rajah L.; Otzen D. E.; Vendruscolo M.; Dobson C. M.; Knowles T. P. J. Proliferation of Amyloid-B42 Aggregates Occurs through a Secondary Nucleation Mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2013, 110 (24), 9758–9763. 10.1073/pnas.1218402110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G.-F.; Xu T.-H.; Yan Y.; Zhou Y.-R.; Jiang Y.; Melcher K.; Xu E. Amyloid Beta: Structure, Biology and Structure-Based Therapeutic Development. Nat. Publ. Group 2017, 38, 1205–1235. 10.1038/aps.2017.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien R. J.; Wong P. C. Amyloid Precursor Protein Processing and Alzheimer’s Disease. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2011, 34, 185–204. 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley J. E.; Farr S. A.; Nguyen A. D.; Xu F. What Is the Physiological Function of Amyloid-Beta Protein?. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2019, 23 (3), 225–226. 10.1007/s12603-019-1162-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deture M. A.; Dickson D. W. The Neuropathological Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2019, 14 (1), 1–18. 10.1186/s13024-019-0333-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois B.; Villain N.; Frisoni G. B.; Rabinovici G. D.; Sabbagh M.; Cappa S.; Bejanin A.; Bombois S.; Epelbaum S.; Teichmann M.; Habert M.-O.; Nordberg A.; Blennow K.; Galasko D.; Stern Y.; Rowe C. C.; Salloway S.; Schneider L. S.; Cummings J. L.; Feldman H. H. Clinical Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease: Recommendations of the International Working Group. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20 (6), 484–496. 10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00066-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvanitakis Z.; Shah R. C.; Bennett D. A. Diagnosis and Management of Dementia: Review. JAMA 2019, 322 (16), 1589–1599. 10.1001/jama.2019.4782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathis C. A.; Mason N. S.; Lopresti B. J.; Klunk W. E. Development of Positron Emission Tomography β-Amyloid Plaque Imaging Agents. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2012, 42 (6), 423–432. 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M.-M.; Ryan P.; Rudrawar S.; Quinn R. J.; Zhang H.-Y.; Mellick G. D. Advances in the Development of Imaging Probes and Aggregation Inhibitors for Alpha-Synuclein. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2020, 41, 483–498. 10.1038/s41401-019-0304-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M.-M.; Ren W.-M.; Tang X.-C.; Hu Y.-H.; Zhang H.-Y. Advances in Development of Fluorescent Probes for Detecting Amyloid-β Aggregates. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2016, 37, 719–730. 10.1038/aps.2015.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villemagne V. L.; Rowe C. C. Amyloid Imaging. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2011, 23, S41–S49. 10.1017/S1041610211000895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kepe V.; Moghbel M. C.; Långströmd B.; Zaidi H.; Vinters H. V.; Huang S. C.; Satyamurthy N.; Doudet D.; Mishani E.; Cohen R. M.; Høilund-Carlsen P. F.; Alavi A.; Barrio J. R. Amyloid-β Positron Emission Tomography Imaging Probes: A Critical Review. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2013, 36 (4), 613–631. 10.3233/JAD-130485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark C. M.; Schneider J. A.; Bedell B. J.; Beach T. G.; Bilker W. B.; Mintun M. A.; Pontecorvo M. J.; Hefti F.; Carpenter A. P.; Flitter M. L.; Krautkramer M. J.; Kung H. F.; Coleman R. E.; Doraiswamy P. M.; Fleisher A. S.; Sabbagh M. N.; Sadowsky C. H.; Reiman P. E. M.; Zehntner S. P.; Skovronsky D. M. Use of Florbetapir-PET for Imaging β-Amyloid Pathology. JAMA 2011, 305 (3), 275–283. 10.1001/jama.2010.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fodero-Tavoletti M. T.; Brockschnieder D.; Villemagne V. L.; Martin L.; Connor A. R.; Thiele A.; Berndt M.; McLean C. A.; Krause S.; Rowe C. C.; Masters C. L.; Dinkelborg L.; Dyrks T.; Cappai R. In Vitro Characterization of [ 18F]-Florbetaben, an Aβ Imaging Radiotracer. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2012, 39, 1042–1048. 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis C.; Gamez J. E.; Singh U.; Sadowsky C. H.; Villena T.; Sabbagh M. N.; Beach T. G.; Duara R.; Fleisher A. S.; Frey K. A.; Walker Z.; Hunjan A.; Holmes C.; Escovar Y. M.; Vera C. X.; Agronin M. E.; Ross J.; Bozoki A.; Akinola M.; Shi J.; Vandenberghe R.; Ikonomovic M. D.; Sherwin P. F.; Grachev I. D.; Farrar G.; Smith A. P. L.; Buckley C. J.; McLain R.; Salloway S. Phase 3 Trial of Flutemetamol Labeled with Radioactive Fluorine 18 Imaging and Neuritic Plaque Density. JAMA Neurol. 2015, 72 (3), 287–294. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.4144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen A. D.; Rabinovici G. D.; Mathis C. A.; Jagust W. J.; Klunk W. E.; Ikonomovic M. D. Using Pittsburgh Compound B for In Vivo PET Imaging of Fibrillar Amyloid-Beta. Adv. Pharmacol. 2012, 64, 27–81. 10.1016/B978-0-12-394816-8.00002-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight R.; Khondoker M.; Magill N.; Stewart R.; Landau S. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Effectiveness of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors and Memantine in Treating the Cognitive Symptoms of Dementia. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2018, 45 (3–4), 131–151. 10.1159/000486546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villemagne V. L.; Klunk W. E.; Mathis C. A.; Rowe C. C.; Brooks D. J.; Hyman B. T.; Ikonomovic M. D.; Ishii K.; Jack C. R.; Jagust W. J.; Johnson K. A.; Koeppe R. A.; Lowe V. J.; Masters C. L.; Montine T. J.; Morris J. C.; Nordberg A.; Petersen R. C.; Reiman E. M.; Selkoe D. J.; Sperling R. A.; Van Laere K.; Weiner M. W.; Drzezga A. Aβ Imaging: Feasible, Pertinent, and Vital to Progress in Alzheimer’s Disease. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2012, 39 (2), 209–219. 10.1007/s00259-011-2045-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeVine H.; Walker L. C. What Amyloid Ligands Can Tell Us about Molecular Polymorphism and Disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2016, 42, 205–212. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aliyan A.; Cook N. P.; Martí A. A. Interrogating Amyloid Aggregates Using Fluorescent Probes. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119 (23), 11819–11856. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter K. A.; Huang X. Machine Learning-Based Virtual Screening and Its Applications to Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery: A Review. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2018, 24 (28), 3347–3358. 10.2174/1381612824666180607124038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voet A.; Qing X.; Lee X. Y.; De Raeymaecker J.; Tame J.; Zhang K.; De Maeyer M. Pharmacophore Modeling: Advances, Limitations, and Current Utility in Drug Discovery. J. Recept. Ligand Channel Res. 2014, 7, 81. 10.2147/JRLCR.S46843. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lengauer T.; Lemmen C.; Rarey M.; Zimmermann M. Novel Technologies for Virtual Screening. Drug Discovery Today 2004, 9 (1), 27–34. 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)02939-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripphausen P.; Nisius B.; Bajorath J. State-of-the-Art in Ligand-Based Virtual Screening. Drug Discovery Today 2011, 16 (9), 372–376. 10.1016/j.drudis.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyne P. D. Structure-Based Virtual Screening: An Overview. Drug Discovery Today 2002, 7 (20), 1047–1055. 10.1016/S1359-6446(02)02483-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creekmore B. C.; Chang Y. W.; Lee E. B. The Cryo-EM Effect: Structural Biology of Neurodegenerative Disease Aggregates. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2021, 80 (6), 514–529. 10.1093/jnen/nlab039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iadanza M. G.; Jackson M. P.; Hewitt E. W.; Ranson N. A.; Radford S. E. A New Era for Understanding Amyloid Structures and Disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19 (12), 755–773. 10.1038/s41580-018-0060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang Z. P.; Kung M. P.; Hou C.; Skovronsky D. M.; Gur T. L.; Plössl K.; Trojanowski J. Q.; Lee V. M. Y.; Kung H. F. Radioiodinated Styrylbenzenes and Thioflavins as Probes for Amyloid Aggregates. J. Med. Chem. 2001, 44 (12), 1905–1914. 10.1021/jm010045q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockhart A.; Ye L.; Judd D. B.; Merrittu A. T.; Lowe P. N.; Morgenstern J. L.; Hong G.; Gee A. D.; Brown J. Evidence for the Presence of Three Distinct Binding Sites for the Thioflavin T Class of Alzheimer’s Disease PET Imaging Agents on β-Amyloid Peptide Fibrils. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280 (9), 7677–7684. 10.1074/jbc.M412056200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye L.; Morgenstern J. L.; Lamb J. R.; Lockhart A. Characterisation of the Binding of Amyloid Imaging Tracers to Rodent Aβ Fibrils and Rodent-Human Aβ Co-Polymers. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 347 (3), 669–677. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.06.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye L.; Morgenstern J. L.; Gee A. D.; Hong G.; Brown J.; Lockhart A. Delineation of Positron Emission Tomography Imaging Agent Binding Sites on β-Amyloid Peptide Fibrils. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280 (25), 23599–23604. 10.1074/jbc.M501285200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh C. J.; Ferrie J. J.; Xu K.; Lee I.; Graham T. J. A.; Tu Z.; Yu J.; Dhavale D.; Kotzbauer P.; Petersson E. J.; Mach R. H. Alpha Synuclein Fibrils Contain Multiple Binding Sites for Small Molecules. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2018, 9 (11), 2521–2527. 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai L.; Qu B.; Hurtle B. T.; Dadiboyena S.; Diaz-Arrastia R.; Pike V. W. Candidate PET Radioligand Development for Neurofibrillary Tangles: Two Distinct Radioligand Binding Sites Identified in Postmortem Alzheimer’s Disease Brain Graphical Abstract HHS Public Access. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2016, 7 (7), 897–911. 10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y.; Murzin A. G.; Falcon B.; Epstein A.; Machin J.; Tempest P.; Newell K. L.; Vidal R.; Garringer H. J.; Sahara N.; Higuchi M.; Ghetti B.; Jang M. K.; Scheres S. H. W.; Goedert M. Cryo-EM Structures of Tau Filaments from Alzheimer’s Disease with PET Ligand APN-1607. Acta Neuropathol. (Berl.) 2021, 1, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrie J. J.; Lengyel-Zhand Z.; Janssen B.; Lougee M. G.; Giannakoulias S.; Hsieh C.-J.; Pagar V. V.; Weng C.-C.; Xu H.; Graham T. J. A.; Lee V. M.-Y.; Mach R. H.; Petersson E. J. Identification of a Nanomolar Affinity α-Synuclein Fibril Imaging Probe by Ultra-High Throughput in Silico Screening. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11 (7), 12746–12754. 10.1039/D0SC02159H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murugan N. A.; Nordberg A.; Ågren H. Different Positron Emission Tomography Tau Tracers Bind to Multiple Binding Sites on the Tau Fibril: Insight from Computational Modeling. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2018, 9, 1757–1767. 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murugan N. A.; Nordberg A.; Ågren H. Cryptic Sites in Tau Fibrils Explain the Preferential Binding of the AV-1451 PET Tracer toward Alzheimer’s Tauopathy. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2021, 12 (13), 2437–2447. 10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A.; Zhang K. Y. J. Advances in the Development of Shape Similarity Methods and Their Application in Drug Discovery. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 315. 10.3389/fchem.2018.00315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimeno A.; Ojeda-Montes M. J.; Tomás-Hernández S.; Cereto-Massagué A.; Beltrán-Debón R.; Mulero M.; Pujadas G.; Garcia-Vallvé S. The Light and Dark Sides of Virtual Screening: What Is There to Know?. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20 (6), 1375. 10.3390/ijms20061375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaller D.; Šribar D.; Noonan T.; Deng L.; Nguyen T. N.; Pach S.; Machalz D.; Bermudez M.; Wolber G. Next Generation 3D Pharmacophore Modeling. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2020, 10 (4), e1468 10.1002/wcms.1468. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X.; Wang Y.; Byrne R.; Schneider G.; Yang S. Concepts of Artificial Intelligence for Computer-Assisted Drug Discovery. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119 (18), 10520–10594. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. QSAR and Primary Docking Studies of Trans-Stilbene (TSB) Series of Imaging Agents for β-Amyloid Plaques. J. Mol. Struct. THEOCHEM 2006, 763 (1–3), 83–89. 10.1016/j.theochem.2006.01.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y.; Zhu L.; Chen X.; Zhang H. Binding Research on Flavones as Ligands of β-Amyloid Aggregates by Fluorescence and Their 3D-QSAR, Docking Studies. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2010, 29 (4), 538–545. 10.1016/j.jmgm.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling T.; Irwin J. J. ZINC 15 – Ligand Discovery for Everyone. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2015, 55 (11), 2324–2337. 10.1021/acs.jcim.5b00559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M.; Hori M.; Haratake M.; Tomiyama T.; Mori H.; Nakayama M. Structure-Activity Relationship of Chalcones and Related Derivatives as Ligands for Detecting of β-Amyloid Plaques in the Brain. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007, 15 (19), 6388–6396. 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.; Zhang X.; Zhang X.; Cui M.; Lu J.; Pan X.; Zhang X. 18F-Labeled Benzyldiamine Derivatives as Novel Flexible Probes for Positron Emission Tomography of Cerebral β-Amyloid Plaques. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 10577–10585. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b01063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee B. C.; Kim J. S.; Kim B. S.; Son J. Y.; Hong S. K.; Park H. S.; Moon B. S.; Jung J. H.; Jeong J. M.; Kim S. E. Aromatic Radiofluorination and Biological Evaluation of 2-Aryl-6-[ 18F]Fluorobenzothiazoles as a Potential Positron Emission Tomography Imaging Probe for β-Amyloid Plaques. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011, 19 (9), 2980–2990. 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada R.; Okamura N.; Furumoto S.; Tago T.; Maruyama M.; Higuchi M.; Yoshikawa T.; Arai H.; Iwata R.; Kudo Y.; Yanai K. Comparison of the Binding Characteristics of [18F]THK-523 and Other Amyloid Imaging Tracers to Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2013, 40 (1), 125–132. 10.1007/s00259-012-2261-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byeon S. R.; Jin Y. J.; Lim S. J.; Lee J. H.; Yoo K. H.; Shin K. J.; Oh S. J.; Kim D. J. Ferulic Acid and Benzothiazole Dimer Derivatives with High Binding Affinity to β-Amyloid Fibrils. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17 (14), 4022–4025. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.04.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fodero-Tavoletti M. T.; Smith D. P.; Mclean C. A.; Adlard P. A.; Barnham K. J.; Foster L. E.; Leone L.; Perez K.; Cortés M.; Culvenor J. G.; Li Q.-X.; Laughton K. M.; Rowe C. C.; Masters C. L.; Cappai R.; Villemagne V. L. Neurobiology of Disease In Vitro Characterization of Pittsburgh Compound-B Binding to Lewy Bodies. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27 (39), 10365–10371. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0630-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.; Cui M.; Zhang J.; Dai J.; Zhang X.; Chen P.; Jia H.; Liu B. Novel 18F-Labeled Dibenzylideneacetone Derivatives as Potential Positron Emission Tomography Probes for in Vivo Imaging of β-Amyloid Plaques. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 84, 628–638. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.07.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia J.; Song J.; Dai J.; Liu B.; Cui M. Optically Pure Diphenoxy Derivatives as More Flexible Probes for β-Amyloid Plaques. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2016, 7 (9), 1275–1282. 10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M.; Yoshida N.; Ishibashi K.; Haratake M.; Arano Y.; Mori H.; Nakayama M. Radioiodinated Flavones for in Vivo Imaging of β-Amyloid Plaques in the Brain. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48 (23), 7253–7260. 10.1021/jm050635e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang Z. P.; Kung M. P.; Hou C.; Skovronsky D. M.; Gur T. L.; Plössl K.; Trojanowski J. Q.; Lee V. M. Y.; Kung H. F. Radioiodinated Styrylbenzenes and Thioflavins as Probes for Amy-loid Aggregates. J. Med. Chem. 2001, 44 (12), 1905–1914. 10.1021/jm010045q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe H.; Ono M.; Iikuni S.; Kimura H.; Okamoto Y.; Ihara M.; Saji H. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of 123I-Labeled Pyridyl Benzoxazole Derivatives: Novel β-Amyloid Imaging Probes for Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 1009–1015. 10.1039/C4RA10742J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yousefi B. H.; Manook A.; Drzezga A.; Reutern B. V.; Schwaiger M.; Wester H. J.; Henriksen G. Synthesis and Evaluation of 11C-Labeled Imidazo[2,1-b] Benzothiazoles (IBTs) as PET Tracers for Imaging β-Amyloid Plaques in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54 (4), 949–956. 10.1021/jm101129a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y. S.; Jeong J. M.; Lee Y. S.; Kim H. W.; Ganesha R. B.; Kim Y. J.; Lee D. S.; Chung J. K.; Lee M. C. Synthesis and Evaluation of Benzothiophene Derivatives as Ligands for Imaging β-Amyloid Plaques in Alzheimer’s Disease. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2006, 33 (6), 811–820. 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M.; Cheng Y.; Kimura H.; Cui M.; Kagawa S.; Nishii R.; Saji H. Novel 18F-Labeled Benzofuran Derivatives with Improved Properties for Positron Emission Tomography (PET) Imaging of β-Amyloid Plaques in Alzheimer’s Brains. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54 (8), 2971–2979. 10.1021/jm200057u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui M.; Ono M.; Kimura H.; Kawashima H.; Liu B. L.; Saji H. Radioiodinated Benzimidazole Derivatives as Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography Probes for Imaging of α-Amyloid Plaques in Alzheimer’s Disease. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2011, 38 (3), 313–320. 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura M.; Ono M.; Matsumura K.; Watanabe H.; Kimura H.; Cui M.; Nakamoto Y.; Togashi K.; Okamoto Y.; Ihara M.; Takahashi R.; Saji H. Structure-Activity Relationships and in Vivo Evaluation of Quinoxaline Derivatives for PET Imaging of β-Amyloid Plaques. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 4 (7), 596–600. 10.1021/ml4000707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young S. C.; Soo J. L.; Seung J. O.; Dae H. M.; Dong J. K.; Cho C. G.; Kyung H. Y. Synthesis of Functionalized Benzoxazoles and Their Binding Affinities to Aβ42 Fibrils. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2008, 29 (9), 1765–1768. 10.5012/bkcs.2008.29.9.1765. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M.; Haratake M.; Mori H.; Nakayama M. Novel Chalcones as Probes for in Vivo Imaging of β-Amyloid Plaques in Alzheimer’s Brains. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007, 15 (21), 6802–6809. 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M.; Hori M.; Haratake M.; Tomiyama T.; Mori H.; Nakayama M. Structure-Activity Relationship of Chalcones and Related Derivatives as Ligands for Detecting of β-Amyloid Plaques in the Brain. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007, 15 (19), 6388–6396. 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchigami T.; Kobashi N.; Haratake M.; Kawasaki M.; Nakayama M. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Radioiodinated Quinacrine-Based Derivatives for SPECT Imaging of Aβ Plaques. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 60, 469–478. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M.; Watanabe R.; Kawashima H.; Cheng Y.; Kimura H.; Watanabe H.; Haratake M.; Saji H.; Nakayama M. Fluoro-Pegylated Chalcones as Positron Emission Tomography Probes for in Vivo Imaging of β-Amyloid Plaques in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 6394–6401. 10.1021/jm901057p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui M.; Ono M.; Kimura H.; Liu B. L.; Saji H. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Indole-Chalcone Derivatives as β-Amyloid Imaging Probe. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21 (3), 980–982. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R.; Fang X.; Lu Y.; Wang S. The PDBbind Database: Collection of Binding Affinities for Protein–Ligand Complexes with Known Three-Dimensional Structures. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47 (12), 2977–2980. 10.1021/jm030580l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez D.; Gaulton A.; Bento A. P.; Chambers J.; De Veij M.; Félix E.; Magariños M. P.; Mosquera J. F.; Mutowo P.; Nowotka M.; Gordillo-Marañón M.; Hunter F.; Junco L.; Mu-gumbate G.; Rodriguez-Lopez M.; Atkinson F.; Bosc N.; Radoux C. J.; Segura-Cabrera A.; Hersey A.; Leach A. R. ChEMBL: Towards Direct Deposition of Bioassay Data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47 (D1), D930–D940. 10.1093/nar/gky1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo Y.; Okamura N.; Furumoto S.; Tashiro M.; Furukawa K.; Maruyama M.; Itoh M.; Iwata R.; Yanai K.; Arai H. 2-(2-[2-Dimethylaminothiazol-5-Yl]Ethenyl)-6-(2-[Fluoro]Ethoxy)Benzoxazole: A Novel PET Agent for in Vivo Detection of Dense Amyloid Plaques in Alzheimer’s Disease Patients. J. Nucl. Med. 2007, 48 (4), 553–561. 10.2967/jnumed.106.037556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuebler L.; Buss S.; Leonov A.; Ryazanov S.; Schmidt F.; Maurer A.; Weckbecker D.; Landau A. M.; Lillethorup T. P.; Bleher D.; Saw R. S.; Pichler B. J.; Griesinger C.; Giese A.; Her-fert K. [11C]MODAG-001—towards a PET Tracer Targeting α-Synuclein Aggregates. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2021, 48 (6), 1759–1772. 10.1007/s00259-020-05133-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu P.; Cui M.; Wang X.; Zhang X.; Li Z.; Yang Y.; Jia J.; Zhang J.; Ono M.; Saji H.; Jia H.; Liu B. 18F-Labeled 2-Phenylquinoxaline Derivatives as Potential Positron Emission Tomography Probes for in Vivo Imaging of β-Amyloid Plaques. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 57, 51–58. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M.; Watanabe R.; Kawashima H.; Kawai T.; Watanabe H.; Haratake M.; Saji H.; Nakayama M. 18F-Labeled Flavones for in Vivo Imaging of β-Amyloid Plaques in Alzheimer’s Brains. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17 (5), 2069–2076. 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura K.; Ono M.; Kimura H.; Ueda M.; Nakamoto Y.; Togashi K.; Okamoto Y.; Ihara M.; Takahashi R.; Saji H. 18F-Labeled Phenyldiazenyl Benzothiazole for in Vivo Imaging of Neurofibrillary Tangles in Alzheimer’s Disease Brains. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 3 (1), 58–62. 10.1021/ml200230e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H.; Byeon S. R.; Kim Y. S.; Lim S. J.; Oh S. J.; Moon D. H.; Yoo K. H.; Chung B. Y.; Kim D. J. [18F]-Labeled Isoindol-1-One and Isoindol-1,3-Dione Derivatives as Potential PET Imag-ing Agents for Detection of β-Amyloid Fibrils. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 5701–5704. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe H.; Ono M.; Kimura H.; Kagawa S.; Nishii R.; Fuchigami T.; Haratake M.; Nakayama M.; Saji H. A Dual Fluorinated and Iodinated Radiotracer for PET and SPECT Imaging of β-Amyloid Plaques in the Brain. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21 (21), 6519–6522. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.08.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajasekhar K.; Narayanaswamy N.; Murugan N. A.; Kuang G.; Ågren H.; Govindaraju T. A High Affinity Red Fluorescence and Colorimetric Probe for Amyloid β Aggregates. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23668. 10.1038/srep23668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y.; Ono M.; Kimura H.; Kagawa S.; Nishii R.; Saji H. A Novel 18F-Labeled Pyridyl Benzofuran Derivative for Imaging of β-Amyloid Plaques in Alzheimer’s Brains. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20 (20), 6141–6144. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura N.; Suemoto T.; Shiomitsu T.; Suzuki M.; Shimadzu H.; Akatsu H.; Yamamoto T.; Arai H.; Sasaki H.; Yanai K.; Staufenbiel M.; Kudo Y.; Sawada T. A Novel Imaging Probe for In Vivo Detection of Neuritic and Diffuse Amyloid Plaques in the Brain. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 247–255. 10.1385/JMN:24:2:247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y.; Zhu B. Y.; Li X.; Li G. B.; Yang S. Y.; Zhang Z. R. A Pyrane Based Fluorescence Probe for Noninvasive Prediction of Cerebral β-Amyloid Fibrils. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 25 (20), 4472–4476. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.08.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dae Park Y.; Kim J.-J.; Lee S.; Park C.-H.; Bai H.-W.; Lee S. S. A Pyridazine-Based Fluorescent Probe Targeting Aβ Plaques in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Anal. Methods Chem. 2018, 2018, 1651989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Y.; Chai K.; Wu J.; Hu Y.; Shi S.; Yang D.; Yao T. A Rational Design to Improve Selective Imaging of Tau Aggregates by Constructing Side Substitution on N,N-Dimethylaniline/Quinoxaline D-π-A Fluorescent Probe. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2023, 380, 133406 10.1016/j.snb.2023.133406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seo Y.; Park K. S.; Ha T.; Kim M. K.; Hwang Y. J.; Lee J.; Ryu H.; Choo H.; Chong Y. A Smart Near-Infrared Fluorescence Probe for Selective Detection of Tau Fibrils in Alzheimer’s Dis-ease. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2016, 7 (11), 1474–1481. 10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Xu D.; Ho S.-L.; Li H.-W.; Yang R.; Wong M. S. A Theranostic Agent for in Vivo Near-Infrared Imaging of β-Amyloid Species and Inhibition of β-Amyloid Aggregation. Biomater. 2016, 94, 84–92. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu H.; Tu P.; Zhao L.; Dai J.; Liu B.; Cui M. Amyloid-β Deposits Target Efficient Near-Infrared Fluorescent Probes: Synthesis, in Vitro Evaluation, and in Vivo Imaging. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88 (3), 1944–1950. 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b04441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang W. M.; Dakanali M.; Capule C. C.; Sigurdson C. J.; Yang J.; Theodorakis E. A. ANCA: A Family of Fluorescent Probes That Bind and Stain Amyloid Plaques in Human Tissue. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2011, 2 (5), 249–255. 10.1021/cn200018v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; Li Y.; Kang J.; Ye T.; Yang Z.; Liu Z.; Liu Q.; Zhao Y.; Liu G.; Pan J. Application of a Novel Coumarin-Derivative near-Infrared Fluorescence Probe to Amyloid-β Imaging and Inhibition in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Lumin. 2023, 256, 119661 10.1016/j.jlumin.2022.119661. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M.; Maya Y.; Haratake M.; Ito K.; Mori H.; Nakayama M. Aurones Serve as Probes of β-Amyloid Plaques in Alzheimer’s Disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 361 (1), 116–121. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajasekhar K.; Narayanaswamy N.; Murugan N. A.; Viccaro K.; Lee H. G.; Shah K.; Govindaraju T. Aβ Plaque-Selective NIR Fluorescence Probe to Differentiate Alzheimer’s Dis-ease from Tauopathies. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 98, 54–61. 10.1016/j.bios.2017.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagchi D. P.; Yu L.; Perlmutter J. S.; Xu J.; Mach R. H.; Tu Z.; Kotzbauer P. T. Binding of the Radioligand SIL23 to α-Synuclein Fibrils in Parkinson Disease Brain Tissue Establishes Feasibility and Screening Approaches for Developing a Parkinson Disease Imaging Agent. PLoS One 2013, 8 (2), e55031 10.1371/journal.pone.0055031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K.; Guo T. L.; Chojnacki J.; Lee H. G.; Wang X.; Siedlak S. L.; Rao W.; Zhu X.; Zhang S. Bivalent Ligand Containing Curcumin and Cholesterol as a Fluorescence Probe for Aβ Plaques in Alzheimer’s Disease. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2012, 3 (2), 141–146. 10.1021/cn200122j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M.; Watanabe H.; Kimura H.; Saji H. BODIPY-Based Molecular Probe for Imaging of Cerebral β-Amyloid Plaques. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2012, 3, 319–324. 10.1021/cn3000058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh C. J.; Xu K.; Lee I.; Graham T. J. A.; Tu Z.; Dhavale D.; Kotzbauer P.; Mach R. H. Chalcones and Five-Membered Heterocyclic Isosteres Bind to Alpha Synuclein Fibrils in Vitro. ACS Omega 2018, 3 (4), 4486–4493. 10.1021/acsomega.7b01897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaide S.; Ono M.; Watanabe H.; Shimizu Y.; Nakamoto Y.; Togashi K.; Yamaguchi A.; Hanaoka H.; Saji H. Conversion of Iodine to Fluorine-18 Based on Iodinated Chalcone and Evaluation for β-Amyloid PET Imaging. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2018, 26 (12), 3352–3358. 10.1016/j.bmc.2018.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narlawar R.; Pickhardt M.; Leuchtenberger S.; Baumann K.; Krause S.; Dyrks T.; Weggen S.; Mandelkow E.; Schmidt B. Curcumin-Derived Pyrazoles and Isoxazoles: Swiss Army Knives or Blunt Tools for Alzheimer’s Disease?. ChemMedChem. 2008, 3 (1), 165–172. 10.1002/cmdc.200700218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Q.; Chen Y.; Yan Y.; Wan R.; Li Y.; Fu H.; Liu Y.; Liu S.; Yan X.-X.; Cui M. D-π-A-Based Trisubstituted Alkenes as Environmentally Sensitive Fluorescent Probes to Detect Lewy Pathologies. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94 (44), 15261–15269. 10.1021/acs.analchem.2c02532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallesh R.; Khan J.; Pradhan K.; Roy R.; Jana N. R.; Jaisankar P.; Ghosh S. Design and Development of Benzothiazole-Based Fluorescent Probes for Selective Detection of Aβ Aggregates in Alzheimer’s Disease. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2022, 13 (16), 2503–2516. 10.1021/acschemneuro.2c00361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu W.; Zhou D.; Gaba V.; Liu J.; Li S.; Peng X.; Xu J.; Dhavale D.; Bagchi D. P.; D’Avignon A.; Shakerdge N. B.; Bacskai B. J.; Tu Z.; Kotzbauer P. T.; Mach R. H. Design, Synthesis, and Characterization of 3-(Benzylidene)Indolin-2-One Derivatives as Ligands for α-Synuclein Fibrils. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58 (15), 6002–6017. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sozmen F.; Kolemen S.; Kumada H.-O.; Ono M.; Saji H.; Akkaya E. U. Designing BODIPY-Based Probes for Fluorescence Imaging of β-Amyloid Plaques. RSC Adv. 2014, 4 (92), 51032–51037. 10.1039/C4RA07754G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Sandberg A.; Konsmo A.; Wu X.; Nyström S.; Nilsson K. P. R.; Konradsson P.; LeVine H.; Lindgren M.; Hammarström P. Detection and Imaging of Aβ1–42 and Tau Fibrils by Redesigned Fluorescent X-34 Analogues. Chem.—Eur. J. 2018, 24 (28), 7210–7216. 10.1002/chem.201800501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchigami T.; Ogawa A.; Yamashita Y.; Haratake M.; Watanabe H.; Ono M.; Kawasaki M.; Yoshida S.; Nakayama M. Development of Alkoxy Styrylchromone Derivatives for Imaging of Cerebral Amyloid-β Plaques with SPECT. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 25, 3363–3367. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M.; Ishikawa M.; Kimura H.; Hayashi S.; Matsumura K.; Watanabe H.; Shimizu Y.; Cheng Y.; Cui M.; Kawashima H.; Saji H. Development of Dual Functional SPECT/Fluorescent Probes for Imaging Cerebral β-Amyloid Plaques. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20 (13), 3885–3888. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M.; Cheng Y.; Kimura H.; Watanabe H.; Matsumura K.; Yoshimura M.; Iikuni S.; Okamoto Y.; Ihara M.; Takahashi R.; Saji H. Development of Novel 123I-Labeled Pyridyl Benzofuran Derivatives for SPECT Imaging of β-Amyloid Plaques in Alzheimer’s Disease. PLoS One 2013, 8 (9), e74104 10.1371/journal.pone.0074104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M.; Haratake M.; Saji H.; Nakayama M. Development of Novel β-Amyloid Probes Based on 3,5-Diphenyl-1,2,4-Oxadiazole. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16 (14), 6867–6872. 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dao P.; Ye F.; Liu Y.; Du Z. Y.; Zhang K.; Dong C. Z.; Meunier B.; Chen H. Development of Phenothiazine-Based Theranostic Compounds That Act Both as Inhibitors of β-Amyloid Aggregation and as Imaging Probes for Amyloid Plaques in Alzheimer’s Disease. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2017, 8 (4), 798–806. 10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv G.; Cui B.; Lan H.; Wen Y.; Sun A.; Yi T. Diarylethene Based Fluorescent Switchable Probes for the Detection of Amyloid-β Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51 (1), 125–128. 10.1039/C4CC07656G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honson N. S.; Johnson R. L.; Huang W.; Inglese J.; Austin C. P.; Kuret J. Differentiating Alzheimer Disease-Associated Aggregates with Small Molecules. Neurobiol. Dis. 2007, 28 (3), 251–260. 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J.; Zhu B.; Yin W.; Han Z.; Zheng C.; Wang P.; Ran C. Differentiating Aβ40 and Aβ42 in Amyloid Plaques with a Small Molecule Fluorescence Probe. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11 (20), 5238–5245. 10.1039/D0SC02060E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Chen C.; Xu D.; Poon C. Y.; Ho S. L.; Zheng R.; Liu Q.; Song G.; Li H. W.; Wong M. S. Effective Theranostic Cyanine for Imaging of Amyloid Species in Vivo and Cognitive Improvements in Mouse Model. ACS Omega 2018, 3 (6), 6812–6819. 10.1021/acsomega.8b00475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu H.; Cui M.; Tu P.; Pan Z.; Liu B. Evaluation of Molecules Based on the Electron Donor—Acceptor Architecture as near-Infrared β-Amyloidal-Targeting Probes. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50 (80), 11875–11878. 10.1039/C4CC04907A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; Ouyang Q.; Li Y.; Zeng Q.; Dai B.; Liang Y.; Chen B.; Tan H.; Cui M. Evaluation of N, O-Benzamide Difluoroboron Derivatives as near-Infrared Fluorescent Probes to Detect β-Amyloid and Tau Tangles. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 227, 113968 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fodero-Tavoletti M. T.; Okamura N.; Furumoto S.; Mulligan R. S.; Connor A. R.; Mclean C. A.; Cao D.; Rigopoulos A.; Cartwright G. A.; O’keefe G.; Gong S.; Adlard P. A.; Barnham K. J.; Rowe C. C.; Masters C. L.; Kudo Y.; Cappai R.; Yanai K.; Villemagne V. L. F-THK523: A Novel in Vivo Tau Imaging Ligand for Alzheimer’s Disease. Brain 2011, 134, 1089–1100. 10.1093/brain/awr038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren W.; Zhang J.; Peng C.; Xiang H.; Chen J.; Peng C.; Zhu W.; Huang R.; Zhang H.; Hu Y. Fluorescent Imaging of β-Amyloid Using BODIPY Based Near-Infrared Off-On Fluorescent Probe. Bioconjugate Chem. 2018, 29 (10), 3459–3466. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.8b00623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y.; Ono M.; Kimura H.; Kagawa S.; Nishii R.; Kawashima H.; Saji H. Fluorinated Benzofuran Derivatives for PET Imaging of β-Amyloid Plaques in Alzheimer’s Disease Brains. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 1 (7), 321–325. 10.1021/ml100082x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawaz M. V.; Brooks A. F.; Rodnick M. E.; Carpenter G. M.; Shao X.; Desmond T. J.; Sherman P.; Quesada C. A.; Hockley B. G.; Kilbourn M. R.; Albin R. L.; Frey K. A.; Scott P. J. H. High Affinity Radiopharmaceuticals Based upon Lansoprazole for PET Imaging of Aggregated Tau in Alzheimer’s Disease and Progressive Supranuclear Palsy: Synthesis, Preclinical Evaluation, and Lead Selection. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2014, 5 (8), 718–730. 10.1021/cn500103u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao R.; Wang N.; Shen T.; Tan Y.; Ren Y.; Wei W.; Liao M.; Tan D.; Tang C.; Xu N.; Wang H.; Liu X.; Li X. High-Fidelity Imaging of Amyloid-Beta Deposits with an Ultrasensitive Fluorescent Probe Facilitates the Early Diagnosis and Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Theranostics 2022, 12 (6), 2549–2559. 10.7150/thno.68743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu H.; Cui M.; Zhao L.; Tu P.; Zhou K.; Dai J.; Liu B. Highly Sensitive Near-Infrared Fluorophores for in Vivo Detection of Amyloid-β Plaques in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58 (17), 6972–6983. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrie J. J.; Lengyel-Zhand Z.; Janssen B.; Lougee M. G.; Giannakoulias S.; Hsieh C.-J.; Pagar V. V.; Weng C.-C.; Xu H.; Graham T. J. A.; Lee V. M.-Y.; Mach R. H.; Petersson E. J. Identification of a Nanomolar Affinity α-Synuclein Fibril Imaging Probe by Ultra-High Throughput in Silico Screening. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11 (7), 12746–12754. 10.1039/D0SC02159H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdurand M.; Levigoureux E.; Zeinyeh W.; Berthier L.; Mendjel-Herda M.; Cadarossanesaib F.; Bouillot C.; Iecker T.; Terreux R.; Lancelot S.; Chauveau F.; Billard T.; Zimmer L. In Silico, in Vitro, and in Vivo Evaluation of New Candidates for α-Synuclein PET Imaging. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2018, 15 (8), 3153–3166. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.8b00229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fodero-Tavoletti M. T.; Mulligan R. S.; Okamura N.; Furumoto S.; Rowe C. C.; Kudo Y.; Masters C. L.; Cappai R.; Yanai K.; Villemagne V. L. In Vitro Characterisation of BF227 Binding to α-Synuclein/Lewy Bodies. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2009, 617 (1–3), 54–58. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y.; Zhu B.; Deng Y.; Zhang Z. In Vivo Detection of Cerebral Amyloid Fibrils with Smart Dicynomethylene-4h-Pyran-Based Fluorescence Probe. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87 (9), 4781–4787. 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe H.; Ono M.; Saji H. In Vivo Fluorescence Imaging of β-Amyloid Plaques with Push-Pull Dimethylaminothiophene Derivatives. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51 (96), 17124–17127. 10.1039/C5CC06628J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. J.; Bando K.; Ashino H.; Taguchi K.; Shiraishi H.; Shima K.; Fujimoto O.; Kitamura C.; Matsushima S.; Uchida K.; Nakahara Y.; Kasahara H.; Minamizawa T.; Jiang C.; Zhang M. R.; Ono M.; Tokunaga M.; Suhara T.; Higuchi M.; Yamada K.; Ji B. In Vivo SPECT Imaging of Amyloid-β Deposition with Radioiodinated Imidazo[1, 2-α]Pyridine Derivative DRM106 in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Nucl. Med. 2015, 56 (1), 120–126. 10.2967/jnumed.114.146944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Wang J.; Sandberg A.; Wu X.; Nyström S.; LeVine H.; Konradsson P.; Hammarström P.; Durbeej B.; Lindgren M. Intramolecular Proton and Charge Transfer of Py-rene-Based Trans-Stilbene Salicylic Acids Applied to Detection of Aggregated Proteins. ChemPhysChem 2018, 19 (22), 3001–3009. 10.1002/cphc.201800823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanna E.; Rodrigues M.; Fagan S. G.; Chisholm T. S.; Kulenkampff K.; Klenerman D.; Spillantini M. G.; Aigbirhio F. I.; Hunter C. A. Mapping the Binding Site Topology of Amyloid Protein Aggregates Using Multivalent Ligands. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12 (25), 8892–8899. 10.1039/D1SC01263K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe H.; Ono M.; Matsumura K.; Yoshimura M.; Kimura H.; Saji H. Molecular Imaging of β-Amyloid Plaques with near-Infrared Boron Dipyrromethane (BODIPY)-Based Fluorescent Probes. Mol. Imaging 2013, 12 (5), 338–347. 10.2310/7290.2013.00049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y.; Fang T.; Xu Y.; Jiang T.; Qiao J. Multi-Fluorine Labeled Indanone Derivatives as Po-tential MRI Imaging Probes for β-Amyloid Plaques. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2022, 0, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou S. S.; Yang J.; Lee J. H.; Kwon Y.; Calvo-Rodriguez M.; Bao K.; Ahn S.; Kashiwagi S.; Kumar A. T. N.; Bacskai B. J.; Choi H. S. Near-Infrared Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging of Amyloid-β Aggregates and Tau Fibrils through the Intact Skull of Mice. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 7, 270–280. 10.1038/s41551-023-01003-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura N.; Suemoto T.; Shimadzu H.; Suzuki M.; Shiomitsu T.; Akatsu H.; Yamamoto T.; Staufenbiel M.; Yanai K.; Arai H.; Sasaki H.; Kudo Y.; Sawada T. Neurobiology of Disease Styrylbenzoxazole Derivatives for In Vivo Imaging of Amyloid Plaques in the Brain. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24 (10), 2535–2541. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4456-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J. W.; Zhu J. Y.; Zhou K. X.; Wang J. S.; Tan H. Y.; Xu Z. Y.; Chen S. B.; Lu Y. T.; Cui M. C.; Zhang L. Neutral Merocyanine Dyes: For: In Vivo NIR Fluorescence Imaging of Amyloid-β Plaques. hem. Commun. 2017, 53 (71), 9910–9913. 10.1039/C7CC05056A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura N.; Furumoto S.; Harada R.; Tago T.; Yoshikawa T.; Fodero-Tavoletti M.; Mulligan R. S.; Villemagne V. L.; Akatsu H.; Yamamoto T.; Arai H.; Iwata R.; Yanai K.; Kudo Y. Novel 18F-Labeled Arylquinoline Derivatives for Noninvasive Imaging of Tau Pathology in Alzheimer Disease. J. Nucl. Med. 2013, 54 (8), 1420–1427. 10.2967/jnumed.112.117341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono M.; Cheng Y.; Kimura H.; Cui M.; Kagawa S.; Nishii R.; Saji H. Novel 18F-Labeled Benzofuran Derivatives with Improved Properties for Positron Emission Tomography (PET) Imaging of β-Amyloid Plaques in Alzheimer’s Brains. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54 (8), 2971–2979. 10.1021/jm200057u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui M.; Ono M.; Kimura H.; Ueda M.; Nakamoto Y.; Togashi K.; Okamoto Y.; Ihara M.; Takahashi R.; Liu B.; Saji H. Novel 18F-Labeled Benzoxazole Derivatives as Potential Posi-tron Emission Tomography Probes for Imaging of Cerebral β-Amyloid Plaques in Alzheimers Disease. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55 (21), 9136–9145. 10.1021/jm300251n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe H.; Ono M.; Ariyoshi T.; Katayanagi R.; Saji H. Novel Benzothiazole Derivatives as Fluorescent Probes for Detection of β-Amyloid and α-Synuclein Aggregates. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2017, 8 (8), 1656–1662. 10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui M.; Ono M.; Kimura H.; Liu B.; Saji H. Novel Quinoxaline Derivatives for in Vivo Imaging of β-Amyloid Plaques in the Brain. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011, 21 (14), 4193–4196. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.05.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe H.; Ono M.; Kimura H.; Matsumura K.; Yoshimura M.; Iikuni S.; Okamoto Y.; Ihara M.; Takahashi R.; Saji H. Novel Radioiodinated 1,3,4-Oxadiazole Derivatives with Improved in Vivo Properties for SPECT Imaging of β-Amyloid Plaques. MedChemComm 2014, 5 (1), 82–85. 10.1039/C3MD00189J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maya Y.; Ono M.; Watanabe H.; Haratake M.; Saji H.; Nakayama M. Novel Radioiodinated Aurones as Probes for SPECT Imaging Of-Amyloid Plaques in the Brain. Bioconjugate Chem. 2009, 20, 95–101. 10.1021/bc8003292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung H. F.; Lee C. W.; Zhuang Z. P.; Kung M. P.; Hou C.; Plössl K. Novel Stilbenes as Probes for Amyloid Plaques. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123 (50), 12740–12741. 10.1021/ja0167147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J.; Konsmo A.; Sandberg A.; Wu X.; Nyströ S.; Obermü U.; Wegenast-Braun B. M.; Konradsson P.; Lindgren M.; Hammarströ P. Phenolic Bis-Styrylbenzo[c]-1,2,5-Thiadiazoles as Probes for Fluorescence Microscopy Mapping of Aβ Plaque Heterogeneity. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 2038–2048. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura K.; Ono M.; Hayashi S.; Kimura H.; Okamoto Y.; Ihara M.; Takahashi R.; Mori H.; Saji H. Phenyldiazenyl Benzothiazole Derivatives as Probes for in Vivo Imaging of Neu-rofibrillary Tangles in Alzheimer’s Disease Brains. MedChemComm 2011, 2 (7), 596–600. 10.1039/c1md00034a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- An J.; Verwilst P.; Aziz H.; Shin J.; Lim S.; Kim I.; Kim Y. K.; Kim J. S. Picomolar-Sensitive β-Amyloid Fibril Fluorophores by Tailoring the Hydrophobicity of Biannulated π-Elongated Dioxaborine-Dyes. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 13, 239–248. 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2021.10.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]