Abstract

In the United States, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) uptake among eligible cisgender women has been slow, despite the availability of oral PrEP since 2012. Although women make up nearly 20% of those living with HIV, there are currently few PrEP uptake interventions for cisgender women at elevated risk for acquiring HIV. Here we describe the process used to design and pre-pilot test Just4Us, a theory-based behavioral intervention to promote PrEP initiation and adherence among PrEP-eligible cisgender women. This work was part of a multiphase study conducted in New York City and Philadelphia, two locations with HIV rates higher than the national average. The counselor-navigator component of the intervention was designed to be delivered in a 60- to 90-min in-person session in the community, followed by several phone calls to support linkage to care. An automated text messaging program was also designed for adherence support. Just4Us addressed personal and structural barriers to PrEP uptake using an empowerment framework by building on women’s insights and resources to overcome barriers along the PrEP cascade. Usability pre-pilot testing results were favorable and provided valuable feedback used to refine the intervention.

Keywords: beliefs, cisgender women, intervention development, HIV prevention, PrEP

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is a highly efficacious tool for HIV prevention (Desai et al., 2017). Since its approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2012 (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services; FDA, 2012), uptake of PrEP has increased dramatically in the United States (470% from 2014 to 2016; Huang et al., 2018). This increase in PrEP uptake has been driven almost exclusively by PrEP use among men (Huang et al., 2018; Salcuni et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2016). However, uptake of PrEP has not kept pace with the HIV infection rates in other vulnerable groups in the United States. Women comprised 19% of new HIV infections in 2017 in the United States (Center for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2019), but represented only 4.6% of PrEP users (Siegler et al., 2018). Moreover, race/ethnicity gaps in PrEP uptake are increasingly apparent (Huang et al., 2018).

Many studies have shown that awareness of PrEP is low among women, with the first of these studies conducted 1 year after FDA approval of the once per day, oral pill, Truvada™, as PrEP. Auerbach et al. (2015) found that only 10% of women in focus groups were aware of PrEP, and many were frustrated for not knowing about PrEP; additionally, a majority of participants held favorable views about PrEP and believed that PrEP should be advertised and accessible to all women who engage in sex. These findings have been reiterated among other groups of women, reported in recent research, suggesting that continued lack of outreach to women, slow development of women-focused interventions, lack of provider knowledge, and provider reluctance to prescribe PrEP to women have resulted in low awareness and uptake among women who are most in need of this prevention tool (Collier et al., 2017; Patel et al., 2019; Raifman et al., 2019; Walters et al., 2017; Willie et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019). Furthermore, recent analyses indicate that the clinical guidelines published by the CDC severely underestimated the number of women who would benefit from PrEP and may be another contributor to the ongoing disparity in PrEP uptake by gender (Calabrese et al., 2019; Turner et al., 2018).

Research on PrEP uptake among men who have sex with men in the United States has focused attention on the various steps in the PrEP cascade from awareness, willingness, planning (or intention), action (seeing a provider, getting a PrEP prescription), and maintenance (Parsons et al., 2017). For cisgender women, there are specific benefits and challenges along the PrEP cascade, with many of these factors highlighted in this article. On the beneficial side, oral PrEP offers a woman-controlled HIV prevention method that can be used covertly, if women prefer or feel safer doing so. For cisgender women who desire pregnancy with male partners living with HIV, PrEP offers a protection from HIV infection. However, many challenges remain. Identifying cisgender women who could benefit from PrEP is challenging for policymakers, providers, and women themselves due to low perceived HIV risk and because some of the PrEP eligibility indicators, such as male partner factors, may be unknown. Especially for women, concerns that others will judge them in a negative light if they are taking PrEP, referred to as women’s PrEP stigma, is a barrier to use (Calabrese et al., 2018; Chittamuru et al., 2020; Goparaju et al., 2017). Furthermore, in the United States, more women live in poverty compared with men, with Black women and women of Hispanic/Latina ethnicity disproportionately affected by poverty (Semega, 2019), which makes access to health care more challenging, especially if women are primarily responsible for dependent care. Having a history of intimate partner violence (IPV) or controlling behaviors, known risk factors for HIV among women (El-Bassel et al., 2011; Sareen et al., 2009; Teitelman et al., 2008), have been linked to greater interest in taking PrEP among women, according to some of the limited United States data currently available (Rubtsova et al., 2013; Teitelman, Lipsky, et al., 2019; Willie, Kershew, et al., 2017; Willie, Stockman, et al., 2017). However, women’s adherence to PrEP appears to be negatively affected by IPV according to research conducted in Africa (Braksmajer et al., 2019; Cabral et al., 2017).

There are few theory-based interventions in the United States to support PrEP uptake among PrEP-eligible cisgender women (Blackstock et al., 2020). To address this gap, our team, with input from our Community Consulting Group (CCG), conducted the Just4Us study, consisting of: Phase 1, formative research; Phase 2, intervention development; and Phase 3, assessing the intervention for feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy in increasing uptake of PrEP in a preliminary randomized controlled trial (RCT). This article reports on Phase 2 only: (a) development of the Just4Us intervention based on our formative research and published literature and (b) findings from our user feedback data, in which we pre-piloted aspects of the intervention components. Our Just4Us (Phase 1) formative research consisted of in-depth interviews and a survey with PrEP eligible women; relevant findings are briefly highlighted below.

There were two major components to the Just4Us intervention: (a) a 1-hr individual face-to-face session with a counselor-navigator (C-N) and follow-up phone calls to facilitate linkage to care and PrEP initiation and (b) an automated text message reminder system to support PrEP adherence. We selected the Just4Us intervention strategies based on best practices identified in relevant publications. Prior research has shown that individually tailored prevention interventions (e.g., for HIV and oral contraceptives) are effective for women, especially when delivered by those trained in communications skills (Halpern et al., 2013; Jemmott et al., 2007). Furthermore, C-Ns who incorporate skill-building, education, and coaching have been shown to reduce health care access barriers among HIV-infected persons (Bradford et al., 2007). Regarding the second component, mobile phones offer a personalized way to reach people in their daily lives, between clinic visits (Malvey & Slovensky, 2014). The ability to provide recurrent reminders offers immediate support as a cue to action for motivating adherence to routine practices (Burner et al., 2014). In addition, mobile phones to support adherence to daily pill use, with use of text-message reminders, is a proven approach to reach populations between clinic appointments (Schwebel & Larimer, 2018).

Drawing from studies in product development, user involvement in the design process, especially during early stages, is considered beneficial for identifying user’s needs and preferences. These usability studies, which are typically small, focus on soliciting qualitative feedback from users (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], 2020). We conducted two pre-pilot usability assessments as part of our design process.

This article describes how our theory-based formative research, along with relevant insights from existing literature on best practices for delivering interventions to this target population, were used to design the Just4Us intervention. We describe the resulting content and structure of the modules that comprise the intervention, user feedback data from our pre-pilot assessment of intervention strategies and materials, and subsequent adjustments made to the intervention.

Methods

Intervention Design Process

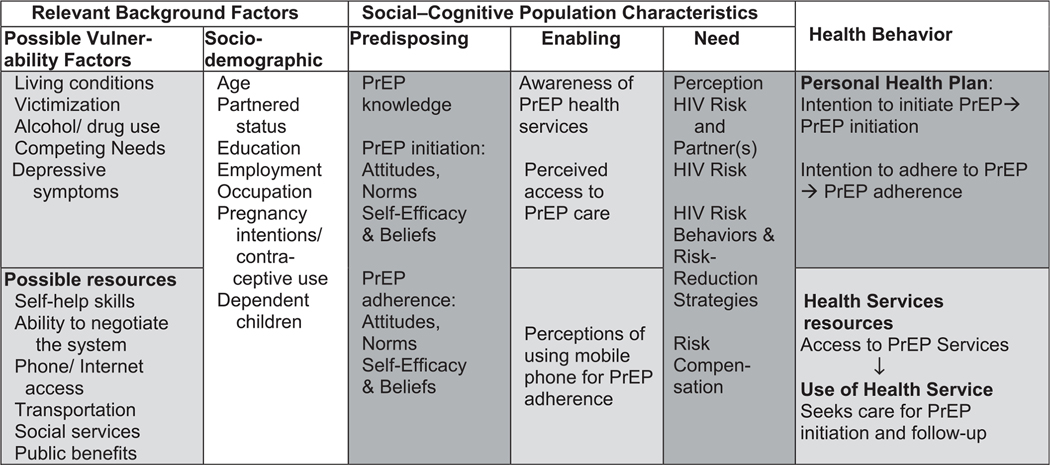

Behavioral interventions that are carefully designed, theory-based, and take into consideration the particular characteristics of a culture or population through formative research have been shown to be effective in promoting HIV prevention behaviors (CDC, 2014; Fishbein, 2000). We used two theories to support our work because they address different levels of influence on health behavior (Teitelman & Koblin, 2017). The Theory of Vulnerable Populations (Gelberg et al., 2000) guided identification of key structural barriers and facilitators to access along the PrEP continuum (e.g., living conditions, competing needs, transportation). We also used the Integrated Model of Behavior (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010) to identify salient beliefs (modifiable social cognitive factors) about starting and staying on PrEP in the next 3 months, including perceived benefits and drawbacks of PrEP, support or lack of support from important others in relation to their PrEP use, and perceived barriers as well as facilitators to PrEP uptake (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Theoretical model for the Just4Us study. Note. Light gray shading: theory of vulnerable populations constructs. Dark gray shading: integrated behavioral model constructs. No shading: constructs overlapping both theories.

The Just4Us intervention was designed based on the existing literature and our formative research, briefly summarized below, consisting of in-depth interviews (n = 41) and a quantitative survey (n = 160), among PrEP-eligible women in Philadelphia and New York City, two US cities with higher than average HIV rates (CDC, 2020).

Analysis of the in-depth interviews and surveys identified specific behavioral (e.g., starting PrEP will/will not reduce my chances of getting HIV), normative (e.g., who would support or not support them in starting PrEP), and control (e.g., I can/cannot locate a clinic to get PrEP) beliefs associated with intention to initiate and adhere to PrEP (Teitelman, Chittamuru, et al., 2020). The women had concerns (i.e., specific beliefs) about lack of support from partners and providers and anticipated stigma about using PrEP, and they identified a lack of skills in talking with partners and providers about PrEP (Chittamuru et al., 2020; Jackson et al., 2019). Women described how experiencing a combination of factors, including homelessness, joblessness, depression, drug use, and partner abuse undermined their ability to take care of themselves, including taking PrEP. We also identified several structural barriers and facilitators to starting PrEP, such as finding a provider who is knowledgeable about PrEP, cost, privacy, and transportation (Teitelman & Koblin, 2017).

During the in-depth interviews (Teitelman & Koblin, 2017), participants were provided with a verbal description of the proposed Just4Us intervention and were asked for feedback. Almost all participants thought the intervention as described was a good idea because the C-N could provide dependable information about their choices for HIV prevention, including PrEP, as well as support/encouragement and guidance on the process for obtaining PrEP. Only a few participants indicated that PrEP was not relevant for them but would be more helpful for others who may be more likely to be exposed to HIV, such as young women. Several participants noted the importance of the program in spreading vital information about PrEP into the community, particularly given the relative newness of the medication and the low awareness of its relevance to women. Some emphasized important qualities C-Ns should have, such as being empathetic about challenges and staying current with information, especially because it pertained to women. A few mentioned the importance of the program being offered in a convenient location.

Additional input on the formative research and intervention design was obtained from CCGs in New York City and Philadelphia. Potential CCG members were identified by circulating information about the Just4Us project to the staff of a wide range of organizations (e.g., homeless shelters, community clinics, drug treatment facilities, or recovery homes) and study team members asking for applications to join the CCG. We were able to accept all applications that were submitted. Initially, the CCGs developed the Just4Us study name, and subsequent meetings were held several times a year to provide input into study instruments, review study procedures, and discuss preliminary findings. Study team members incorporated suggestions from the CCG discussions groups into the study processes and intervention design. In Philadelphia, two additional CCG discussions were convened with PrEP-eligible women to present the text messaging adherence component of the intervention and obtain feedback from the group. All CCG members received $25 compensation and a snack or light meal.

Description of the Just4Us Intervention: Overview

Just4Us was developed as an individual-level, tailored, motivational, and skill-building intervention delivered by trained C-Ns to support and promote PrEP uptake intention and behavior—both initiation and adherence. The intervention used empowerment theory as a heuristic, as PrEP is a woman-controlled biomedical HIV prevention approach. Empowerment theory emphasizes an individual’s ability to solve their own problems (Perkins & Zimmerman, 1995; Zimmerman, 1995), while acknowledging that they act within—and resist—systems of oppression (Guillaumin, 2002). Thus, the Just4Us intervention was framed within an empowerment approach; as well, specific intervention strategies within the sessions were used to facilitate feelings of empowerment, as well as the exercise of agency in accessing available options. Furthermore, the team was versed in trauma-informed care and integrated those principles into the content of the intervention (Machtinger et al., 2015; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014).

The Just4Us intervention also incorporated a client-centered, harm reduction approach (Harm Reduction Coalition, 2020; Harm Reduction International, 2020), which was essential to establish a trusting, non-judgmental relationship with women. Implementing a client-centered, harm reduction approach demonstrated to women that the C-N appreciated and respected their individual needs and circumstances without negative judgment. Harm reduction meshed naturally with the intent of the intervention because it supported women in making choices that suited them best given their immediate needs, values, and available resources. The intervention was intended to help women consider relevant recommendations in light of internally driven priorities rather than on externally driven, stigmatizing societal judgments about the women’s circumstances.

Description of Just4Us Intervention: Counselor-Navigator Session and Phone Follow-up

The Just4Us research team created an intervention manual for C-Ns to use in the preparation for and the facilitation of the intervention session. The in-person session consisted of 12 mini-modules, each lasting approximately 5–8 min for a total session length of 60–90 min, with varied interactive content, including tablet-based activities. This session was designed to support initiation of PrEP and introduce the text messaging component (described below). In Table 1, each module of the C-N session is described in detail, stating the objectives/goal, then the topics covered/theoretical construct(s) addressed, followed by a description of activities. For example, in Module Eight: “I Got This: Building Skills to Get PrEP,” a goal was to build communication skills with providers about PrEP, the theoretical construct addressed was self-efficacy to start PrEP, and the activity included a role-play, practicing a conversation with a provider about PrEP. Role-plays are considered an evidence-based approach to bolster self-efficacy (Abraham & Kools, 2012).

Table 1.

Just4Us Module Descriptions

| Objectives/Goals | Topics/Theoretica/ Construct | Module Activities |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Module 1: Just4Us is just for me: taking care of ourselves now and for our future | ||

| Ensure participants understand overarching theme of Just4Us and know what is going to happen during the session | Promote favorable attitudes toward PrEP | Begin with a short deep breathing exercise, which is also offered as a tool to assist with emotion regulation. |

| Establish rapport using client-centered approach | Promote PrEPself-efficacy: PrEP may be one strategy she can use to stay healthy | Brainstorm theme of Just4Us, connect theme to participant’s overall health goals, and discuss potential barriers. |

| Identify participant’s health goals and obstacles, provide encouragement, and reinforce Just4Us empowerment theme | Tablet used to create a word cloud from responses to “What does Just4Us mean to you?” Word cloud is revisited at the end of intervention. | |

| Connect participant health goals with the goals of the intervention | Individualized action plan to stay healthy is introduced to record ideas generated through modules. | |

| Skill-building for emotion regulation, as strong emotions can be a possible barrier to health actions, including PrEP | ||

|

| ||

| Module 2: Knowledge is power: learning how PrEP can protect me against HIV | ||

| Increase PrEP awareness and basic knowledge by providing standardized information via a women-focused PrEP video, which includes role modeling PrEP acceptance by peers | PrEP awareness, knowledge, self-efficacy, stigma, norms | Participant watches an 8-min animated video with 3 women discussing PrEP and several providers who offer additional information about PrEP. Participant checks off topics she hears about on the video as she watches. Check sheet reviewed and positive feedback provided. |

| Reinforce knowledge with active watching activity | Perceived need for PrEP | Teach-back activity: Participant shares her PrEP knowledge with female friend, through a role-play. |

| Increase comfort in talking about and asking questions about PrEP | Communication about PrEP (with partners and providers, other women) | |

| Introduce topics covered in greater details in later modules | Integrating PrEP with women’s overall sexual and reproductive health (e.g., continued need for STI protection) | |

| Knowledge reinforcement | ||

|

| ||

| Module 3: Mirror talk: checking my chances of getting HIV/STIs | ||

| Identify what increases or decreases one’s likelihood to be exposed to HIV/ STIs | Address awareness of behaviors that increase or decrease chances of being exposed to HIV and STIs | Participant categorizes predetermined statements as increasing or decreasing likelihood of HIV exposure and discusses reasons. Laminated words/phrases (e.g., had sex while drunk, or used a condom during vaginal sex) are placed on a board under two headings (increase/ decrease likelihood). |

| Perceived risk/vulnerability to HIV | Additional suggestions elicited from participant as strategies she may use to reduce the likelihood of acquiring HIV/STIs. | |

|

| ||

| Module 4: One size doesn’t fit all: my personalized options for HIV/STI prevention | ||

| Increase awareness of and knowledge about PrEP in relation to other modalities of HIV prevention and other STIs | PrEP Knowledge | Participant is given a safe sex “toolkit” (laminated pictures or words) and asked to choose HIV/STI prevention strategies that have been helpful/have been used in the past and strategies they plan to use/would consider trying, including PrEP. |

| Distinguish PrEP from pregnancy prevention | Distinguish PrEP from other HIV/STI prevention strategies | |

| Increase knowledge and discuss the use and safety of PrEP regarding contraception and pregnancy | PrEP not for pregnancy prevention | |

| Knowledge reinforcement | Difference between PrEP and PEP | |

| Importance of using PrEP with other HIV/STI prevention strategies | ||

|

| ||

| Modules 5 and 6: How to make PrEP part of your life: strategies to manage what you and others think about PrEP | ||

| Increase awareness of their beliefs about PrEP | PrEP behavioral and normative beliefs | Three tablet activities on several behavioral/stigma beliefs. Participant picks one statement she most agrees with within each group of beliefs. C-N selects appropriate MI strategy to discuss beliefs with participant. |

| Address unfavorable beliefs and promote favorable beliefs about starting PrEP in the next 3 months | Women’s PrEP Stigma | Two tablet activities on normative beliefs. First, the participant selects someone who would support her starting PrEP, then someone who would get in the way of her starting PrEP. C-N discusses strategies for effective communication with others about PrEP. |

| Address stigma from others | Self-efficacy for communication about PrEP to others | Deciding about talking to others about PrEP (it is her choice). Participant is provided with communication strategies with the possibility she may encounter some initial resistance, followed by a scripted role-play activity to practice those strategies. |

| Build skill to communicate about PrEP with others (family, friends, partners) | Negotiating sexual safety and negotiating pregnancy intentions with partner | If a participant expresses concern for a strong negative response, e.g., from partner, she is given appropriate referrals for intimate partner violence (IPV). |

| Use motivational interviewing strategies, including reflective listening, summarizing, change talk, and other strategies when encountering ambivalence or resistance | ||

|

| ||

| Module 7: It’s bigger than me: acknowledging things that interfere with my taking PrEP | ||

| Identify structural vulnerability factors that may interfere with individual PrEP uptake | Identify structural vulnerability factors, including time/schedule around work, school, treatment program; childcare responsibilities; lack of money or health insurance; transportation; food insecurity; homelessness/lack of housing; etc. | Tablet activity showing road to PrEP and possible barriers, allowing participant to identify personal challenges. C-N provides appropriate local resources* that they can access and discusses a plan for accessing specific resources. |

| Identify resources for those vulnerability factors | Identify structural resources | *The C-N has access to a large file of appropriate city-specific resources. |

| Develop plan to use the resources and address the vulnerabilities | Acknowledge how such factors can interfere with or promote staying healthy/starting PrEP | |

| Provide information about local resources to address particular issues/concerns | ||

|

| ||

| Module 8: I got this: building skills to get PrEP | ||

| Providing knowledge and skills development in all the steps needed to access PrEP from a provider | Review steps on the PrEP roadmap, including all steps before the health care provider visit, at the visit and after the visit | Using the tablet, the C-N shows the participant a “roadmap to PrEP” with all the necessary steps surrounding a visit with a health care provider (e.g., identify a provider, call for an appointment), during the visit (e.g., talk about sex and drug use with provider) and after the visit (e.g., get lab work done, get prescription filled). |

| Build communication skills with health care providers | Self-efficacy for starting PrEP | In-depth conversations and role-plays include contacting a provider and ways to talk to providers. |

| Address access to health care, including how to pay for PrEP | Handouts provided: printed roadmap, insurance information about PrEP, local list of providers and contact information, provider cheat sheet (key points for provider conversation). | |

| Address stigma from others in the health system | C-Ns reference and build upon their positive beliefs, skills, and structural resources they can use to access PrEP. | |

|

| ||

| Module 9: Make it happen: the call to start PrEP | ||

| Develop skills around the health care systems | Self-efficacy for starting PrEP | Extends discussion of providers. The C-N works with participant to choose a provider, either from the list or her own provider if preferred. Discusses comfort about talking with selected provider about PrEP. C-N offers opportunity to make appointment just then during the session and if so, completes a PrEP appointment card. |

|

| ||

| Module 10: Tracking back: let’s review what we’ve learned about PrEP | ||

| Reinforcement of objectives and goals of previous modules, especially Module 8 | Knowledge reinforcement, self-efficacy for PrEP initiation | C-N reviews materials in tote bag/ health information with participant. Encourages beneficial health habits. |

| General health information included in packet (as decoy to avoid PrEP stigma and as a resource for women to help promote their health in general) | Discusses safety of taking materials home and any negative repercussions participant may face. Makes appropriate referrals or initiates IPV standard operating procedure (SOP),* as needed. | |

| *IPV SOP—procedures for addressing women in immediate harm | ||

|

| ||

| Module 11: Why is my phone buzzing? Text reminders for PrEP | ||

| Present text message adherence program | Cues to action from the Health Beliefs Model | C-N explains text messaging application and enrolls participant. Participant creates her own messages, which do not directly reference PrEP. Weekly messages sent until participant starts PrEP and then daily messages begin. C-N sends test message to participant’s mobile phone to verify participant can receive messages and can identify the Just4Us phone number. |

| Enroll participant in the text messaging (participants can opt out of the text messaging component if they choose to do so) | ||

|

| ||

| Module 12: Onward and upward: my plan for PrEP | ||

| Reinforce the plan | Reinforcement of knowledge and selfefficacy; reiterate empowerment theme | C-N expresses appreciation to participant for considering PrEP, reinforces action plan, and explains follow-up phone calls. |

| Revisits the Word Cloud from Module 1 on the tablet. Emails or texts the Word Cloud to the woman if she would like it. | ||

| Follow-up phone calls—C-Ns make up to four phone calls to assist participant in accessing PrEP | ||

| Assist participant to overcome actual barriers she may encounter when she attempts to access PrEP | Self-efficacy to overcome personal and structural barriers to initiating PrEP and staying on PrEP | C-N assesses where woman is in relation to all the steps in PrEP roadmap, supports actions taken, identifies and problem solves in relation to barriers. |

Note. Italicized text = theoretical constructs. C-N = counselor-navigator; MI = motivational interviewing; PEP = postexposure prophylaxis; PrEP = pre-exposure prophylaxis; STI = sexually transmitted infection.

The intervention started with an introduction eliciting the woman’s meaning of “Just4Us” and the C-N described the personalized action plan that would be developed throughout the remaining modules. This led into the next module, which conveyed basic information about PrEP provided through a short woman-focused video (Bond, 2018) followed by a teach-back technique for knowledge reinforcement. The C-N then worked with the woman in the next two modules to raise awareness of vulnerability to HIV, other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and their preferred choices for HIV/STI prevention, including PrEP. In Modules 5 and 6, the C-N then identified the woman’s supportive PrEP beliefs and, using motivational interviewing techniques, fostered reframing of unsupportive beliefs and identified structural resources she could use to access PrEP. The next module was designed to identify vulnerability factors and link the women to social service resources to overcome barriers to accessing PrEP. Modules 8 and 9 were used to familiarize women with all the steps needed to access PrEP and help women talk with providers and connect with local clinics accepting PrEP referrals, which included offering the woman an opportunity to call for an appointment during the session. Module 10 provided knowledge reinforcement by reviewing the information packet and condoms and lube provided in the Just4Us tote bag. Handouts were provided on general health (exercise, diet, smoking, and breast cancer screening), PrEP, and postexposure prophylaxis. We added the general health handouts to convey to women that we were interested in their health overall and also as a decoy in case a partner or others would react negatively to seeing only HIV-related materials. Module 11 involved women setting up the text message program by creating up to 3 different personalized discrete text messages to receive later for PrEP adherence support. The last module was a session wrap-up, including review of the woman’s created action plan that identified steps needed to advance her safer sex and PrEP goals. This in-person session was then followed by up to four weekly follow-up phone calls by the C-Ns to further assist women in overcoming barriers and accessing clinical care for PrEP using the customized action plan as a guide.

Description of Just4Us Intervention: Automated Text Messaging

In 2019, approximately 96% of Americans had a mobile phone and 80% of the overall population had a smart phone (about 70% among those of low income, Pew Research Center, 2019). Our survey findings with PrEP-eligible women (Broomes et al., 2019) indicated that 24% did not have access to a smart phone. Therefore, we decided to use a text message reminder system, rather than a smart phone–based application. Advantages of text messages are that they are familiar to most mobile phone users and easy to use. A disadvantage is the message length is constrained. To support PrEP adherence, an automated text messaging system was developed by the research team in conjunction with consultants from the Penn Medicine Center for Health Care Innovation and the University of Pennsylvania, School of Nursing Information Technology Services, using the Twilio platform, and linked to each woman’s text message preferences, which were entered on a REDCap database collected via a computer tablet (during the C-N session described above). Beginning 1 week after the C-N in-person session, the system sent women their customized initial query about whether they had started PrEP. Once a woman indicated that she had started PrEP, her personalized daily reminder adherence messages were sent, followed 1 hr later by a personalized prompt to reply yes if she had taken her pill for the day. Women were encouraged by the C-N to design their initial query, daily adherence message and prompt as messages that were meaningful to them, and to not reference PrEP directly for privacy reasons. Women could choose to enter up to three different daily message pairs that would alternate randomly through the week.

Just4Us Intervention: Counselor-Navigator Training

Each C-N (four in Philadelphia, two in New York City) had prior experience as an intervention facilitator and/or was a health professional (nurse, social worker); all were women and half were from a minority background (Black/African American). In addition, the research study investigators provided 6 hr of in-person group training that included (a) an overview of the Just4Us intervention, including theoretical approach and formative research; (b) a description of facilitation strategies, such as motivational interviewing techniques and perspectives such as harm reduction and empowerment; and (c) a detailed explanation of each module with time to role-play activities. A facilitator’s training guide was distributed to all C-Ns to use as a reference and included written descriptions of training content, activities, and handouts. After the group training session, C-Ns reviewed all the intervention materials, engaged in additional role-plays as needed with other staff, and conducted a mock C-N session with a co-worker on video followed by a self-evaluation. Two members of the research team independently evaluated each video using a standardized assessment form, evaluating facilitation skills, knowledge, time management, and adherence to objectives of each module, using 1–5 (poor–excellent) rating scales along with narrative feedback, which was all given to the C-N. To proceed to working with study participants, C-Ns had to achieve a mastery of 4–5 (very good–excellent) on all components, repeating the mock C-N session on video as necessary. Ongoing supervision was provided by the research study team that included a social worker, nurses, a nurse practitioner, and a physician.

Pre-pilot Study Procedures: In-person Counselor-Navigator Session

We pre-pilot tested the Just4Us intervention session with a few women in Philadelphia to estimate the length of the intervention session and to ensure all processes went smoothly before conducting the actual pilot study. We recruited PrEP-eligible cisgender women between the ages of 18 and 54 years. Eligibility criteria were consistent with PrEP guidelines, published by the CDC and New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute as of 2016 when this study began; however, the guidelines have been more recently updated (CDC, 2018; New York State Health Department of Health AIDS Institute: Medical Care Criteria Committee, 2018). Exclusion criteria were not being able to read and write English at a fifth-grade level and currently being pregnant. Study team members recruited women either in person or with flyers posted in homeless shelters, substance abuse treatment programs, recovery centers, and online sites (e.g., Craig’s List). Women interested in the study talked with a study staff member in person or by phone and were first provided with a brief description of the study and invited to provide verbal consent to screen for eligibility. If eligible, participants were scheduled for a study visit that took place at the university research site. After completing informed consent for the pre-pilot study, women completed an HIV testing and counseling session with a research staff member (all four received negative test results) and then a baseline survey on a tablet. The baseline survey contained the same questions as our formative survey (Teitelman, Chittamuru, et al., 2020; Chittamuru et al., 2020). A trained C-N then delivered the individual intervention session, which was audio-recorded. This was followed by administration of a postintervention survey on the tablet that assessed only the social-cognitive factors that were assessed at baseline (e.g., PrEP knowledge, beliefs, perceived risk). All received the packet of information, tote bag, condoms, and lube. For compensation, women received $50 in reimbursement along with a local resource guide that included clinics offering PrEP. The C-N completed a postintervention evaluation of the session. All pre-pilot study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Pennsylvania (protocol # 825256).

Pre-pilot Study Procedures: Text Messaging Application

The purpose of this pre-pilot study, conducted with a few women in Philadelphia, was to learn what types of text messages women preferred and the frequency and timing of reminder messages. To pre-pilot test the automated text messaging program, we needed women who were taking daily medication. The study team, in consultation with the Philadelphia Department of Public Health (PrEP Provider Taskforce), could not locate women who were already taking PrEP. As a proxy, the text messaging process was pre-piloted with cisgender women, ages 18–55 years old, living with HIV, recruited from an HIV clinic in Philadelphia, who were on a once daily antiretroviral (ARV) medication regimen. To be eligible, these women also had to (a) have access to a cell phone to receive and send text messages, (b) feel comfortable sending and receiving text messages in English, and (c) be willing to participate in the study for 6 weeks. Exclusion criteria included not being able to read and write English at a fifth grade level. Clinic staff referred patients to the study team by giving them the study flyer. Interested women called the study phone number, and research staff screened them for eligibility after obtaining verbal consent. If eligible, women (a) met with study staff one time, either in the clinic or the study research office, (b) completed written informed consent, (c) set up the text messaging, and (d) later received one follow-up phone call to solicit feedback. At the initial visit, participants were presented with a list of potential reminder messages they could use or customize based on the Integrated Behavioral Model to foster motivation for daily medication adherence, for example, highlighting the beneficial outcomes or those who would support them in this behavior. Participants also had the option to create their own text messages. To protect their privacy, women were encouraged to not include the words meds, ARVs, or make any reference to medications. All participants chose what time of day the first message would be sent. In all cases, the follow-up message was sent 1 hr after the first reminder message.

Each woman received one pair of text messages daily for a duration of 3–6 weeks and were given $20 as compensation. The first message was a reminder message to take their medication. The second message was a follow-up message that elicited a response regarding whether the participants had completed taking their medication that day. To gather valuable user feedback before spending additional resources on the design and development of the text message platform, our team used the “If This Then That” web application (IFTTT.com) and Google phone numbers to send the customized text messages to these women. Through this rapid, inexpensive, and innovative approach to pre-pilot testing, we were able to test our assumptions and learn about opportunities for improvement before we finalized the text message platform.

Results

Pre-pilot Testing the Just4Us Counselor-Navigator Session

The four women in the in-person C-N intervention session pre-pilot, conducted in August 2018, ranged in age between 39 and 51 years; all four were Black/African American; three had not completed high school, and one had a high school diploma. All participants reported a household income in the past year of less than US $42,000, with two participants having an income less than US $12,000. All 4 had experienced financial insecurity (not enough money for rent, food, utilities) in the past 3 months, either very often (n = 2) or once in a while (n = 2). All had heard of PrEP but none had taken it before.

Feedback from participants about the Just4Us intervention, provided after the session, was positive, with all participants indicating they were satisfied with the informational video, the discussions with the C-N, setting up the text messages, and the tablet activities. All expressed that they learned a lot, the duration of the session was appropriate, and they would recommend it to others. After listening to the audio recordings of the intervention session, the research team found that (a) the C-N was able to deliver the intervention with a high level of fidelity, (b) a good rapport was developed between the C-N and participant, and (c) the sessions were highly interactive, with the C-N providing affirming support to participants.

The C-Ns’ postintervention evaluation forms indicated that the sessions ranged in length from 62 to 74 min. C-Ns’ comments also indicated the action plan needed to be better integrated into each module and the directions in the intervention manual for setting up the text messaging program needed to be simplified because they were overly detailed and difficult for the C-N to use. In addition, women should be asked about whether they should take home any written materials as a final way to check their safety.

As a result of this pre-piloting, we found our study procedures were functioning well: (a) recruitment strategies were successful at locating PrEP-eligible women; (b) HIV testing and counseling went smoothly; (c) surveys were able to be completed on the tablets; and (d) the C-N intervention could be delivered in the 60- to 90-min time frame. In addition, the study team finalized the intervention manual. Some edits included clarifying the linkage of the action plan within all relevant modules, editing the text messaging section, and making sure to ask women whether they were comfortable taking home the tote bag and intervention materials.

Pre-pilot Testing the Automated Text Message Adherence Program

Four women, meeting study eligibility criteria, participated in the text messaging pre-pilot assessment in January and February 2018. All chose to create their own text messages. Examples of message pairs included: “Take care of yourself today/Did you take care of yourself today?” and “Give yourself love today/Did you give yourself love today?” Although they were offered the opportunity to enter up to seven different message pairs (one pair per day) that would vary in order each day of the week, three of four participants preferred to receive the same text message pair every day throughout the pilot’s lifespan. Feedback from participants indicated they were not tired of the messages because they were personal creations that were self-affirming and had specific meaning to them. “Of course, I liked the message—I wrote it!” was a common sentiment expressed by the women. As for the one participant who opted midway through the intervention to alternate the message pair she had been receiving with an additional message pair, she endorsed a preference for pretending the messages were coming from a concerned friend; the relatively spontaneous content promoted this illusion that the messages were being sent to her from elsewhere. All participants ranked the daily text reminder “5/5: extremely helpful” in reminding them to take their ARVs. They indicated the follow-up message, sent an hour after the reminder message, was incredibly important to “bump” the reminder in their awareness, especially if they had been occupied when the first message was delivered. All the women expressed an interest in maintaining the messaging for themselves at the conclusion of the pre-pilot study. As a result of all the pilot testing, the research team decided to limit the number of text message pairs to three (reduced from the originally planned seven). Also, in the final design of the text messaging program, all reminder messages and verification prompt messages would be created by the women.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is among the first theory-based intervention designed to promote PrEP initiation and adherence among PrEP-eligible women in the United States (Blackstock et al., 2020). The Just4Us intervention was designed to be used for women in the community who are not necessarily connected to a health care provider or clinic. One major goal of the intervention was to link women to PrEP clinical care with a provider of their choice. By using empowerment, harm-reduction, and trauma-informed approaches, interwoven with theoretical guidance from the Theory of Vulnerable Populations (Gelberg et al., 2000) and the Integrated Model of Behavior (Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010), the Just4Us intervention laid the foundation for informed decision-making by the women. Furthermore, to mitigate PrEP stigma, the intervention avoided labelling women as “being at high risk for HIV” but rather focused on offering them choices for reducing their chances of getting HIV and taking a proactive approach to their sexual health (Golub, 2018). These considerations are consistent with patient-centered care practices, already in place in many primary care settings, including family planning clinics, Federally Qualified Health Centers, and HIV prevention Service Organizations, which make them appropriate places for PrEP referrals (Seidman & Weber, 2016).

We wanted to make sure we identified women’s strengths, resources, and preferences and leveraged them toward overcoming challenges to starting PrEP. For example, if a woman indicated a friend would be supportive of her starting PrEP, we might suggest the friend accompany her when seeing a provider for PrEP. Or if a woman indicated she preferred to see her primary care provider with whom she had good communication, we offered an opportunity to practice discussing PrEP with her provider using a role-play activity.

Our formative research identified the possibility of both supportive and interfering partner factors, including IPV, which could influence PrEP uptake among women (Teitelman, Jackson, et al., 2019). In the United States, there are inconsistent findings regarding women with IPV and PrEP acceptability (Garfinkel et al., 2017; Rubtsova et al., 2013). Although little is known about IPV and PrEP adherence among cisgender women in the United States, study findings indicate some women anticipate partners may interfere or become abusive if they were to start PrEP (Braksmajer et al., 2019; Willie, Stockman, et al., 2017). As a result, the intervention provided skill-based content on discussing PrEP with a selected support person, as well as options for avoiding unwanted disclosure of PrEP use. Women’s safety was assessed at various points in the intervention, and specific IPV referrals were provided to address any immediate or long-term needs consistent with practice recommendations (Aaron et al., 2018).

Current evidence on oral PrEP among women indicates it takes up to 3 weeks of consistent daily adherence to achieve full protection (for vaginal sex) and continued usage for up to 4 weeks after the last possible exposure to maintain protection (Aaron et al., 2018). Therefore, it is still important to identify and reinforce women’s preferred safer sex practices as an integral part of a PrEP intervention and think holistically by incorporating prevention of STIs and pregnancy, as relevant for each woman.

In designing the activities in the intervention, we employed evidence-based behavior change strategies mapped to our theoretical constructs (Abraham & Kools, 2012; Eldredge et al., 2016; Kok et al., 2004). For example, we provided information in a standardized video format, adding in an active viewing and recall activity for knowledge reinforcement. For PrEP communication skill-building and promoting self-efficacy, we elicited women’s suggestions, offered additional specific strategies, and provided the opportunity to rehearse anticipated situations using role-plays. To tailor the intervention and make it more engaging, most activities involved interactive components, such as selecting barriers on the road to PrEP, facilitated by pictorial representations on a tablet. We used an iterative process of intervention development involving research team members and our two CCGs in New York and Philadelphia, integrating best practices in user-centered design (De Vito Dabbs et al., 2009) with a community-informed approach (Newman et al., 2011). Much of the content for the Just4Us Intervention was derived from the small body of existing literature as of 2016 on factors associated with PrEP uptake among women in the United States, as well as our own theory-based formative research, input from our CCGs, and feedback from our pilot testing. For example, low levels of PrEP knowledge, the possibility of being stigmatized as mistakenly HIV positive, and access issues, such as cost, have been identified as important topics to address in both the prior literature and in our formative work (Auerbach et al., 2015; Goparaju et al., 2017; Teitelman & Koblin, 2017; Walters et al., 2017).

Regarding our activities related to helping women understand the steps in the PrEP cascade from awareness to initiation to adherence, we initially drew from previous literature about the PrEP cascade among men who have sex with men (Liu et al., 2012). However, based on our formative research, CCG feedback, and pilot testing, we found the need to provide detailed explanations about the linkage-to-care step on the PrEP cascade that included (a) locating a provider, (b) calling for an appointment (which they could do during the intervention), (c) getting to the appointment (including determining transportation), (d) discussing PrEP with a provider, (e) getting laboratory tests, (f) getting a prescription for PrEP, (g) getting the prescription filled, and (h) completing any paperwork needed to access payment for any of these steps. Because the actual linkage would take place after the C-N visit, the follow-up phone calls were essential for supporting women because they encountered any barriers along the way. This approach is supported from evidence reported in a Cochrane review of interventions to improve acceptance and adherence to hormonal contraception, indicating follow-up phone calls can be beneficial (Halpern et al., 2013).

The Just4Us intervention not only focused on helping women move along the PrEP cascade toward initiation but also provided adherence support in the form of a text messaging component. We knew PrEP adherence of a daily oral pill would be an especially challenging issue for women, considering the findings of the FEM-PrEP study (Corneli et al., 2014, 2016) and the extensive analogous literature on contraceptive adherence (Halpern et al., 2013). In developing the text message adherence component of Just4Us, we drew on promising literature in the area of ARV and contraceptive adherence (Dowshen et al., 2012, 2013; Halpern et al., 2013). Initially, we were concerned that women would fatigue from receiving the same message pair every day; however, our pilot findings indicated women had a strong preference for receiving the same messages daily or rotating between two messages during the week. In the final design of the automated text messaging program, we could accommodate up to three message pairs per week. Assessments from additional participants in the future will allow us to determine whether this is sufficient.

Women who can benefit from PrEP often face structural barriers to PrEP uptake, such as economic insecurity, homelessness, and the cost of PrEP (Aaron et al., 2018; Seidman & Weber, 2016). The intervention included an assessment of these barriers and discussion between the C-N and woman about approaches to overcoming such barriers. However, some of the recommendations offered by women in our formative work and other studies, extended beyond the scope of the individual intervention we set out to develop. For example, women in drug recovery suggested co-locating PrEP services with treatment programs (Teitelman & Koblin, 2017). Some women were concerned about the cost of health care visits and laboratory tests, even if oral PrEP was provided for free. Therefore, to augment the potential benefits of a C-N intervention, such as Just4Us, complementary changes in PrEP care access need to be addressed as well. In addition, incarcerated women will need a more tailored approach (Ramsey et al., 2019).

For ease of implementation, the intervention consisted of a 1-hr, one-to-one session with a C-N, combined with up to four phone calls to support PrEP initiation and a daily text message reminder system to support PrEP adherence. Clinics offering PrEP often employ PrEP navigators, an already existing role well-suited to deliver this content and set up the text message program. However, for women who prefer to see their own providers, PrEP wrap-around services, such as C-Ns, may be limited. In this case, the C-N sessions could be adopted and supported by community groups. The intervention could also be adapted to deliver a few modules at a time, making it easier to implement in multiple sessions with a primary care provider.

A limitation of our text messaging pre-pilot assessment was that it was conducted among women living with HIV. However, the messages were individually tailored because each woman created her own messages. This study may also be limited by drawing on our research conducted among women living in urban areas in the Northeastern United States; however, we also incorporated findings from other existing research with a broader representation of women, although there is still limited research about PrEP among ciswomen in rural areas and in the Southern part of the United States, and more generally among adolescents girls. In addition, there is scant research on PrEP uptake during pregnancy in the United States. Therefore, our findings may not generalize to all women and all settings in the United States, but they may provide a starting place for future adaptation. One of our long-term goals, enabled by a theory-based approach, is to identify which aspects of the intervention are responsible for behavior change. This would allow us to distinguish between the core elements that would need to be retained and the other characteristics that could be modified for adaptation to other populations of women in the United States who could benefit from an intervention such as this one to support PrEP uptake (McKleroy et al., 2006). This could be especially useful for future modifications when, for example, women have a choice of PrEP delivery options in the future, that may include, for example, the dapivirine vaginal ring that has been studied in women and is awaiting regulatory approval (PrEP Watch, 2020a) or injectables that are still undergoing study (PrEP Watch, 2020b). Although these newer PrEP delivery methods have advantages over oral PrEP for women, in that they would not require daily use, they may also come with related barriers such as cost, limited access, or partner concerns (e.g., if the ring is noticed during intercourse; Nel et al., 2016).

Conclusions

Just4Us is among the first theory-based behavioral interventions designed to promote PrEP uptake among cisgender women at elevated risk for HIV in the United States. In designing Just4Us, we addressed both personal and structural factors that could interfere with PrEP initiation and adherence, and built on women’s strength and resources to overcome barriers. The next phase of this research involved conducting a two-arm pilot randomized controlled study to assess the Just4Us intervention for feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy (Teitelman, Tieu, et al., 2020; Tieu et al., 2020). This research is needed to determine whether this “dose” of intervention is enough to promote behavior change given the considerable obstacles many women face in accessing PrEP.

Key Considerations.

Public health efforts to reduce HIV infection need to include individually tailored, theory-based strategies designed for cisgender women to foster initiation and adherence to PrEP.

Interventions to increase PrEP uptake among cisgender women implemented in clinic or community settings can include counselor-navigators to assist women in decision-making about PrEP.

Using text messages to support PrEP adherence among cisgender women is a promising approach given wide use of mobile phones and high levels of acceptability.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. William Short, Community Consulting Groups members, study participants, and the outstanding staff who made this work possible.

This study was funded by an NIH, NIMH grant (1R34MH108437-01A1; PI: A. M. Teitelman) and an NIH, NIAID grant (5-P30-AI-45008-20; PI: R. Collman). Thank you to the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing, Information Technology Service, notably, Tej Patel, Joshua Poinsett, and Aous Abbas.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest, except Hong-Van Tieu has received a research grant from Gilead for a different research study on hepatitis B and C.

Ethics Approval

All procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee at the University of Pennsylvania (protocol # 825256) and NIH (Certificate of Confidentiality from NIH # CC-MH-16–257) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

ClinicalTrial registration number: NCT03699722.

Contributor Information

Anne M. Teitelman, School of Nursing, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA..

Beryl A. Koblin, Independent Consultant, Metuchen, New Jersey, USA..

Bridgette M. Brawner, School of Nursing, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA..

Annet Davis, School of Nursing, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA..

Caroline Darlington, School of Nursing, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA..

Rachele K. Lipsky, National Clinical Scholars Program, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, USA; School of Nursing, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA..

Emilia Iwu, Rutgers University School of Nursing, Division of Nursing Science and Center for Global Health, Newark, New Jersey, USA..

Keosha T. Bond, Department of Community Health and Social Medicine, City University of New York School of Medicine, New York, New York, USA..

Julie Westover, University of California San Diego, School of Medicine, San Diego, California, USA; Penn Medicine Center for Health Care Innovation, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA..

Danielle Fiore, Just4Us Study, School of Nursing, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA..

Hong-Van Tieu, Lindsley F. Kimball Research Institute, New York Blood Center, New York, New York, USA..

References

- Aaron E, Blum C, Seidman D, Hoyt MJ, Simone J, Sullivan M, & Smith DK (2018). Optimizing delivery of HIV preexposure prophylaxis for women in the United States. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 32(1), 16–23, 10.1089/apc.2017.0201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham C, & Kools M. (Eds.). (2012). Writing health communication: An evidence-based guide. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach JD, Kinsky S, Brown G, & Charles V (2015). Knowledge, attitudes, and likelihood of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use among US women at risk for acquiring HIV. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 29(2), 102–110. https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/apc.2014.0142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackstock OJ, Platt J, Golub SA, Anakaraonye AR, Norton BL, Walters SM, Sevelius JM, & Cunningham CO (2020). A pilot study to evaluate a novel pre-exposure prophylaxis peer outreach and navigation intervention for women at high risk for HIV infection. AIDS and Behavior. Advance online publication. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10461-020-02979-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond KT (2018, November 13). LOVE study: Theoretical bases and e-health HIV intervention design for Black women to increase awareness of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Oral session. American Public Health Association Annual Meeting, San Diego, CA. https://apha.confex.com/apha/2018/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/415299 [Google Scholar]

- Bradford JB, Coleman S, & Cunningham W (2007). HIV system navigation: An emerging model to improve HIV care access. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 21(Suppl 1), S49–S58. https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/apc.2007.9987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braksmajer A, Leblanc NM, El-Bassel N, Urban MA, & McMahon JM (2019). Feasibility and acceptability of pre-exposure prophylaxis use among women in violent relationships. AIDS Care, 31(4), 475–480. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09540121.2018.1503634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broomes TR, Tieu H-V, Ortiz GJ, Lucy D, Davis-Vogel A, Brawner B, Shaw P, Ratcliffe S, Koblin BA, & Teitelman AM (2019, March 18–21). A descriptive account: High risk heterosexual women, PrEP intention, and missed opportunities (Refereed poster presentation). 2019 National HIV Prevention Conference (NHPC) Atlanta, GA (Abstract # 5989). https://www.cdc.gov/nhpc/pdf/NHPC-2019-Abstract-Book.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Burner ER, Menchine MD, Kubicek K, Robles M, & Arora S (2014). Perceptions of successful cues to action and opportunities to augment behavioral triggers in diabetes self-management: Qualitative analysis of a mobile intervention for low-income Latinos with diabetes. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(1), e25. https://www.jmir.org/2014/1/e25/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabral A, Baeten J, Ngure K, Velloza J, Odoyo J, Haberer J, Celum C, Muwonge T, Asiimwe S, Heffron R, & Partners Demonstration Project Team. (2017). Intimate partner violence and self-reported pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) interruptions among HIV-negative partners in HIV serodiscordant couples in Kenya and Uganda. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, 77, 154–159. https://journals.lww.com/jaids/Fulltext/2018/02010/Intimate_Partner_Violence_and_Self_Reported.5.aspx [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese SK, Dovidio JF, Tekeste M, Taggart T, Galvao RW, Safon CB, Willie TC, Caldwell A, Kaplan C, & Kershaw TS (2018). HIV preexposure prophylaxis stigma as a multidimensional barrier to uptake among women who attend planned parenthood. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, 79(1), 46–53. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese SK, Willie TC, Galvao RW, Tekeste M, Dovidio JF, Safon CB, Blackstock O, Taggart T, Kaplan C, Caldwell A, & Kershaw TS (2019). Current US guidelines for prescribing HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) disqualify many women who are at risk and motivated to use PrEP. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, 81(4), 395–405. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30973543/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Compendium of evidence-based interventions and best practices for HIV prevention. Retrieved July 15, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/research/interventionresearch/compendium/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in the United States—2017 Update: A clinical practice guideline. Retrieved July 15, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2017.pdf

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). HIV among women. Retrieved July 15, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/gender/women/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). HIV surveillance report, 2018 (updated) (Vol. 31). Retrieved November 9, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2018-updated-vol-31.pdf

- Chittamuru D, Frye V, Koblin BA, Brawner B, Tieu H-V, Davis A, & Teitelman AM (2020). PrEP stigma, HIV stigma, and intention to use PrEP among women in New York City and Philadelphia. Stigma and Health, 5(2), 240–246. 10.1037/sah0000194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier KL, Colarossi LG, & Sanders K (2017). Raising awareness of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among women in New York City: Community and provider perspectives. Journal of Health Communication, 22(3), 183–189. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10810730.2016.1261969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corneli AL, Deese J, Wang M, Taylor D, Ahmed K, Agot K, Lombaard J, Manongi R, Kapiga S, Kashuba A, Van Damme L, & FEM-PrEP Study Group. (2014). FEM-PrEP: Adherence patterns and factors associated with adherence to a daily oral study product for pre-exposure prophylaxis. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, 66(3), 324–331. https://journals.lww.com/jaids/Fulltext/2014/07010/FEM_PrEP___Adherence_Patterns_and_Factors.12.aspx [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corneli A, Perry B, McKenna K, Agot K, Ahmed K, Taylor J, Malamatsho F, Odhiambo J, Skhosana J, & Van Damme L (2016). Participants’ explanations for nonadherence in the FEM-PrEP clinical trial. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, 71(4), 452–461. https://journals.lww.com/jaids/Fulltext/2016/04010/Participants__Explanations_for_Nonadherence_in_the.17.aspx [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vito Dabbs A, Myers BA, Mc Curry KR, Dunbar-Jacob J, Hawkins RP, Begey A, & Dew MA (2009). User-centered design and interactive health technologies for patients. Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 27(3), 175. https://journals.lww.com/cinjournal/Fulltext/2009/05000/User_Centered_Design_and_Interactive_Health.11.aspx [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai M, Field N, Grant R, & McCormack S (2017). Recent advances in pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV. BMJ, 359, j5011. https://www.bmj.com/content/359/bmj.j5011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowshen N, Kuhns LM, Gray C, Lee S, & Garofalo R (2013). Feasibility of interactive text message response (ITR) as a novel, real-time measure of adherence to antiretroviral therapy for HIV+ youth. AIDS and Behavior, 17(6), 2237–2243. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10461-013-0464-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowshen N, Kuhns LM, Johnson A, Holoyda BJ, & Garofalo R (2012). Improving adherence to antiretroviral therapy for youth living with HIV/AIDS: A pilot study using personalized, interactive, daily text message reminders. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 14(2), e51. https://www.jmir.org/2012/2/e51/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Witte S, Wu E, & Chang M (2011). Intimate partner violence and HIVamong drug-involved women: Contexts linking these two epidemics—Challenges and implications for prevention and treatment. Substance Use & Misuse, 46(2–3), 295–306. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.3109/10826084.2011.523296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldredge LKB, Markham CM, Ruiter RAC, Fernandez ME, Kok G, & Parcel GS (2016). Planning health promotion programs: An intervention mapping approach (4th ed.). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, & Ajzen I (2010). Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach. Psychology Press (Taylor & Francis). [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M (2000). The role of theory in HIV prevention. AIDS Care, 12(3), 273–278. 10.1080/09540120050042918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel DB, Alexander KA, McDonald-Mosley R, Willie TC, & Decker MR (2017). Predictors of HIV-related risk perception and PrEP acceptability among young adult female family planning patients. AIDS Care, 29(6), 751–758. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09540121.2016.1234679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelberg L, Andersen RM,& Leake BD(2000). The behavioral model for vulnerable populations: Application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Services Reseach, 34(6), 1273–1302. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1089079/ [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub SA (2018). PrEP stigma: Implicit and explicit drivers of disparity. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 15(2), 190–197. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11904-018-0385-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goparaju L, Praschan NC, Warren-Jeanpiere L, Experton LS, Young MA, & Kassaye S (2017). Stigma, partners, providers and costs: Potential barriers to PrEP uptake among US women. Journal of AIDS & Clinical Research, 8(9), 730. https://www.hilarispublisher.com/open-access/stigma-partners-providers-and-costs-potential-barriers-to-prep-uptakeamong-us-women-2155-6113-1000730.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillaumin C (2002). Racism, sexism, power and ideology: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern V, Lopez LM, Grimes DA, Stockton LL, & Gallo MF (2013). Strategies to improve adherence and acceptability of hormonal methods of contraception. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (10), CD004317. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD004317.pub2/full [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harm Reduction Coalition. (2020). Principles of harm reduction. Retrieved March 27, 2020, from https://harmreduction.org/about-us/principles-of-harm-reduction/

- Harm Reduction International. (2020). What is harm reduction? https://www.hri.global/what-is-harm-reduction

- Huang YA, Zhu W, Smith DK, Harris N, & Hoover KW (2018). HIV preexposure prophylaxis, by race and ethnicity—United States, 2014–2016. Morbity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67(41), 1147–1150. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6741a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson G, Teitelman AM, Tieu H-V, Brawner BM, Davis-Vogel A, Bannon JA, & Koblin BA (2019, March 18–21). Women & PrEP: The role of patient provider communication (refereed poster presentation). Paper presented at the National HIV Prevention Conference (NHPC), Atlanta, GA (Abstract # 6046). https://www.cdc.gov/nhpc/pdf/NHPC-2019-Abstract-Book.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Jemmott LS, Jemmott JB, & O’Leary A (2007). Effect on sexual risk behavior and STD rate of brief HIV/STD prevention interventions for African American women in primary care settings. American Journal of Public Health, 97(6), 1034–1040. https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/10.2105/AJPH.2003.020271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok G, Schaalma H, Ruiter RA, van Empelen P, & Brug J (2004). Intervention mapping: Protocol for applying health psychology theory to prevention programmes. Journal of Health Psychology, 9(1), 85–98. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1359105304038379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu A, Colfax G, Cohen S, Bacon O, Kolber M, Amico KR, Mugavero M, Grant R, & Buchbinder S (2012). The spectrum of engagement in HIV prevention: Proposal for a PrEP cascade. Paper presented at the IAPAC. https://www.iapac.org/AdherenceConference/presentations/ADH7_80040.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Machtinger EL, Cuca YP, Khanna N, Rose CD, & Kimberg LS (2015). From treatment to healing: The promise of trauma-informed primary care. Womens Health Issues, 25(3), 193–197. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S104938671500033X?via%3Dihub [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malvey D, & Slovensky DJ (2014). mHealth: Transforming healthcare. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- McKleroy VS, Galbraith JS, Cummings B, Jones P, Harshbarger C, Collins C, Gelaude D, Carey JW, & ADAPT Team. (2006). Adapting evidence-based behavioral interventions for new settings and target populations. AIDS Education and Prevention, 18(4 Suppl A), 59–73. https://guilfordjournals.com/doi/10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nel A, Bekker L-G, Bukusi E, Hellstrӧm E, Kotze P, Louw C, Martinson F, Masenga G, Montgomery E, Ndaba N, van der Straten A, van Niekerk N, & Woodsong C (2016). Safety, acceptability and adherence of Dapivirine vaginal ring in a microbicide clinical trial conducted in multiple countries in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS One, 11(3), e0147743. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26963505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New York State Health Department of Health AIDS Institute: Medical Care Criteria Committee. (2018). Clinical guidelines program: PrEP to prevent HIV and promote sexual health. Retrieved July 15, 2020, from https://www.hivguidelines.org/prep-for-prevention/

- Newman SD, Andrews JO, Magwood GS, Jenkins C, Cox MJ, & Williamson DC (2011). Community advisory boards in community-based participatory research: A synthesis of best processes. Preventing Chronic Disease, 8(3), A70. Retrieved July 15, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2011/may/10_0045.htm [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Rendina HJ, Lassiter JM, Whitfield TH, Starks TJ, & Grov C (2017). Uptake of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in a national cohort of gay and bisexual men in the United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, 74(3), 285–292. https://journals.lww.com/jaids/Fulltext/2017/03010/Uptake_of_HIV_Pre_Exposure_Prophylaxis__PrEP__in_a.8.aspx [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel AS, Goparaju L, Sales JM, Mehta CC, Blackstock OJ, Seidman D, Ofotokun I, Kempf M-C, Fischl MA, Golub ET, Adimora AA, French AL, DeHovitz J, Wingood G, Kassaye S, & Sheth AN (2019). Brief Report: PrEP eligibility among at-risk women in the Southern United States: Associated factors, awareness, and acceptability. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, 80(5), 527–532. https://journals.lww.com/jaids/Fulltext/2019/04150/Brief_Report__PrEP_Eligibility_Among_At_Risk_Women.6.aspx [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins DD, & Zimmerman MA (1995). Empowerment theory, research, and application. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(5), 569–579. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1007/BF02506982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. (2019). Mobile fact sheet. Internet & Technology. Retrieved July 15, 2020, from https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/mobile/ [Google Scholar]

- PrEP Watch. (2020a). Dapivirine vaginal ring. Next-Gen. Retrieved July 15, 2020, from https://www.prepwatch.org/nextgen-prep/dapivirine-vaginal-ring/ [Google Scholar]

- PrEP Watch. (2020b). Long-acting injectable PrEP. Next-Gen. Retrieved July 15, 2020, from https://www.prepwatch.org/nextgen-prep/long-acting-injectables/ [Google Scholar]

- Raifman JR, Schwartz SR, Sosnowy CD, Montgomery MC, Almonte A, Bazzi AR, Drainoni M-L, Stein MD, Willie TC, Nunn AS, & Chan PA (2019). Brief report: Pre-exposure prophylaxis awareness and use among cisgender women at a sexually transmitted disease clinic. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, 80(1), 36–39. https://journals.lww.com/jaids/Fulltext/2019/01010/Brief_Report__Pre_exposure_Prophylaxis_Awareness.6.aspx [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey SE, Ames EG, Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Teitelman AM, Clarke J, & Kaplan C (2019). Linking women experiencing incarceration to community-based HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis care: Protocol of a pilot trial. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 14(1), 8. https://ascpjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13722-019-0137-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubtsova A, Wingood GM, Dunkle K, Camp C, & DiClemente RJ (2013). Young adult women and correlates of potential adoption of preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP): Results of a national survey. Current HIV Research, 11(7), 543–548. https://www.eurekaselect.com/120014/article [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salcuni P, Smolen J, Jain S, Myers J, & Edelstein Z (2017). Trends and associations with PrEP prescription among 602 New York City (NYC) ambulatory care practices, 2014–2016. Open Forum Infectious Diseases, 4(Suppl 1), S21. https://academic.oup.com/ofid/article/4/suppl_1/S21/4293925 [Google Scholar]

- Sareen J, Pagura J, & Grant B (2009). Is intimate partner violence associated with HIV infection among women in the United States? General Hospital Psychiatry, 31(3), 274–278. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0163834309000437?via%3Dihub [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwebel FJ, & Larimer ME (2018). Using text message reminders in health care services: A narrative literature review. Internet Interventions, 13, 82–104. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2214782918300022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidman D, & Weber S (2016). Integrating preexposure prophylaxis for human immunodeficiency virus prevention into women’s health care in the United States. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 128(1), 37–43. https://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Fulltext/2016/07000/Integrating_Preexposure_Prophylaxis_for_Human.7.aspx [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semega J (2019). Census.gov: America counts: Stories behind the numbers: Payday, poverty, and women. Retrieved July 15, 2020, from https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2019/09/payday-poverty-and-women.html

- Siegler AJ, Mouhanna F, Giler RM, Weiss K, Pembleton E, Guest J, Jones J, Castel A, Yeung H, Kramer M, McCallister S, & Sullivan PS (2018). The prevalence of pre-exposure prophylaxis use and the pre-exposure prophylaxis-to-need ratio in the fourth quarter of 2017, United States. Annals of Epidemiology, 28(12), 841–849. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2018.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. SAMHSA. Retrieved July 15, 2020, from https://store.samhsa.gov/product/SAMHSA-s-Concept-of-Trauma-and-Guidance-for-a-Trauma-Informed-Approach/SMA14-4884 [Google Scholar]

- Teitelman A, & Koblin B (2017, December 4–5). Just4Us women & PrEP study: Preliminary findings. Paper presention. 2017 Biomedical HIV Prevention Summit, New Orleans, LA. https://www.biomedicalhivsummit.org/wpcontent/uploads/2017/11/NMAC_Summit_Book.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Teitelman AM, Chittamuru D, Koblin BA, Davis A, Brawner BM, Fiore D, Broomes T, Ortiz G, Lucy D, & Tieu HV (2020). Beliefs associated with intention to use PrEP among cisgender U.S. women at elevated HIV risk. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49, 2213–2221. 10.1007/s10508-020-01681-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teitelman AM, Jackson GY, Tieu H-V, Brawner BM, Davis-Vogel A, Bannon JA, & Koblin BA (2019, March 18–21). The importance of intimate partner support for women considering PrEP (Refereed poster presentation). Paper presented at the 2019 National HIV Prevention Conference (NHPC), Atlanta, GA (Abstract #6064). https://www.cdc.gov/nhpc/pdf/NHPC-2019-Abstract-Book.pdf [Google Scholar]