Abstract

Carbonic anhydrase, a zinc enzyme catalyzing the interconversion of carbon dioxide and bicarbonate, is nearly ubiquitous in the tissues of highly evolved eukaryotes. Here we report on the first known plant-type (β-class) carbonic anhydrase in the archaea. The Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum ΔH cab gene was hyperexpressed in Escherichia coli, and the heterologously produced protein was purified 13-fold to apparent homogeneity. The enzyme, designated Cab, is thermostable at temperatures up to 75°C. No esterase activity was detected with p-phenylacetate as the substrate. The enzyme is an apparent tetramer containing approximately one zinc per subunit, as determined by plasma emission spectroscopy. Cab has a CO2 hydration activity with a kcat of 1.7 × 104 s−1 and Km for CO2 of 2.9 mM at pH 8.5 and 25°C. Western blot analysis indicates that Cab (β class) is expressed in M. thermoautotrophicum; moreover, a protein cross-reacting to antiserum raised against the γ carbonic anhydrase from Methanosarcina thermophila was detected. These results show that β-class carbonic anhydrases extend not only into the Archaea domain but also into the thermophilic prokaryotes.

Carbonic anhydrase is a zinc-containing enzyme that catalyzes the reversible hydration of CO2 (CO2 + H2O ⇋ HCO3− + H+). In eukaryotes, the enzyme participates in various physiological functions, which include the interconversion of CO2 and HCO3− during photosynthesis and intermediary metabolism, facilitated diffusion of CO2, pH homeostasis, and ion transport (5, 45). Carbonic anhydrase is nearly ubquitous in highly evolved eukaryotes, but until recently the enzyme was thought to play a minor role in prokaryotic physiology (48). All carbonic anhydrases are divided into three distinct classes (α, β, and γ) that have no sequence homology and evolved independently (22). Carbonic anhydrases from mammals (including the 10 active human isoforms) (22, 39) together with the two periplasmic enzymes from the unicellular green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (16, 17) belong to the α class. The β class is comprised of enzymes from the chloroplasts of both monocotyledonous and dicotyledonous plants (22). Four prokaryotic carbonic anhydrases from species in the Bacteria domain, two belonging to the α class and two belonging to the β class, have been described (13, 20, 49, 50). The only carbonic anhydrase purified from an archaeon, Methanosarcina thermophila, is decidedly distinct from the α and β classes and is the prototype of a novel class (γ class) (2).

Crystal structures have been determined for five isozymes (CA I to CA V) of the monomeric human carbonic anhydrase (9, 14, 21, 28, 51) and the Neisseria gonorrhoeae enzyme (25) belonging to the α class. The overall folds of these monomeric enzymes are highly similar, with a 10-stranded, mainly antiparallel, β-sheet as the dominating structure. The catalytically active zinc is ligated to three histidine residues, with a water molecule acting as a fourth ligand. The structure of the prototype γ carbonic anhydrase from M. thermophila has recently been solved and found to be entirely different from those of the α-class enzymes (31). The enzyme is a trimer with three zinc-containing active sites, each located at the interface between two monomers. The zinc is coordinated in a tetrahedral geometry with three histidines and two to three putative water molecules serving as ligands (1). The main secondary structures are several parallel β-sheets forming a left-handed β-helix. Although a three-dimensional structure has yet to be determined for a β carbonic anhydrase, extended X-ray absorption fine structure and circular dichroism of the plant enzyme indicate that the zinc coordination and overall structure are quite different from those for either the α- or γ-class enzymes (10, 42).

Methanoarchaea, the largest group within the Archaea domain, obtain energy for growth by either the production of methane from the reduction of CO2, utilizing H2 or formate as electron donors, or the conversion of the methyl groups of acetate, methanol, or methylamines to methane (8, 15). To date, the only characterized carbonic anhydrase from the Archaea domain is the γ carbonic anhydrase (Cam) from the methanoarchaeon M. thermophila, which can convert the methyl group of acetate, methanol, or methylated amines to methane. Western blot analysis indicates that Cam is expressed predominantly during growth on acetate, suggesting that this carbonic anhydrase is important for acetotrophic growth (3). Cam appears to be located outside the cell, and it has been proposed that it might be required for a CH3CO2−/H+ symport system or for efficient removal of cytoplasmically produced CO2 during growth on acetate (2).

Here we report on the initial characterization of a β carbonic anhydrase from Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum ΔH, the first carbonic anhydrase from a CO2-reducing methanoarchaeon in the Archaea domain. Our results show that β carbonic anhydrases occur not only in the Archaea domain but also in thermophilic chemolithoautotrophs, species that represent some of the deepest branches of the universal tree of life (53).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning and hyperexpression of the cab gene in Escherichia coli.

Two oligonucleotides (primers MBTCA1 [5′-GGTTTGTTACCATGGTTATTAAAG-3′; partially corresponding to the amino terminus of Cab] and MBTCA2 [5′-CGTAGAGGATCCTTCAG-3′; partially corresponding to the carboxy terminus of Cab]), 100 ng of M. thermoautotrophicum ΔH genomic DNA, and the GeneAmp DNA amplification kit (Perkin-Elmer Cetus) were used to amplify the genomic region containing the cab gene. The amplification generated NcoI and BamHI restriction sites on the ends of the amplified product. The product was digested with NcoI and BamHI and cloned into the appropriately digested pET16b− (Novagen) to generate plasmid pMBTCA13. E. coli BL21(DE3) competent cells were transformed with pMBTCA13, grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani broth containing 100 μg of ampicillin per ml, and induced with 27.8 mM lactose and 0.5 mM zinc sulfate (final concentration) at an A600 of 0.8. After an induction of 3 h at 37°C, the cells were harvested by centrifugation and stored at −70°C.

Purification of the heterologously produced Cab.

Carbonic anhydrase activity was measured at room temperature, using a modification of the electrometric method of Wilbur and Anderson as described previously (58). Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford method (11), using Bio-Rad dye reagent and bovine serum albumin (Sigma) as the standard. Thawed cell paste (10 g [wet weight]) was suspended in 20 ml of buffer A (50 mM potassium phosphate [pH 6.8]) and passed twice through a chilled French pressure cell at 138 MPa. The cell lysate was centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 20 min to remove cell debris. The supernatant solution was recentrifuged at 100,000 × g for 2 h. The cell extract was then heated at 65°C for 20 min and centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 15 min. The supernatant was loaded onto a Mono Q 10/10 anion-exchange column (Pharmacia) equilibrated with buffer A. After a 30-ml wash, the column was developed with a 100-ml linear gradient from 0 to 1 M KCl. Fractions containing active enzyme were pooled, desalted, and again run on a Mono Q column. The enzyme eluted between 460 and 520 mM KCl. The active fractions were pooled and stored at −20°C.

Esterase activity.

Activity for p-nitrophenylacetate hydrolysis was determined at 25°C, using a modification of the method of Armstrong et al. (4). The reaction mixture (1.35 ml) contained freshly prepared 3 mM p-nitrophenylacetate in acetone. The uncatalyzed rate of the reaction was determined by adding 0.15 ml of 100 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.0) and recording the change in A348 per min (Δɛ = 5,000 M−1 cm−1). After 2 min, 15 μl of enzyme solution was added, and the catalyzed reaction was monitored for an additional 3 min.

Molecular mass determination.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed as described previously (33), using 12% gels. The native molecular mass was determined by gel filtration chromatography, using a Superose 12 gel filtration column (Pharmacia) calibrated with bovine milk α-lactalbumin (14.2 kDa), bovine erythrocyte carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa), chicken egg albumin (45 kDa), bovine serum albumin (66 kDa; dimer, 132 kDa), and urease (trimer, 272 kDa; hexamer, 545 kDa). Protein samples (0.5 ml) were loaded onto the column pre-equilibrated with buffer A containing 150 mM KCl, and the column was developed with a flow rate of 0.4 ml/min.

Metals analysis.

A comprehensive metals analysis (20 elements) was carried out by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy, using a Jarrel Ash Plasma Comp 750 instrument at the Chemical Analysis Laboratory, University of Georgia. All solutions were prepared in plasticware, using deionized water (18 Ω) from a Barnstead-Thermolyne deionization system. Dialysis tubing (Spectrum) was treated and buffers were made metal free by batch treatment with Chelex 100 (Bio-Rad) (3, 24). Samples of two independent enzyme preparations were first concentrated in dialysis tubing (3.5-kDa cutoff) embedded in dry polyethylene glycol (Mr = 8000; Sigma) at 4°C before dialysis against 2 liters of metal-free buffer (20 mM potassium phosphate [pH 6.8]) for 20 h at 4°C. A sample of each enzyme preparation along with a sample of buffer alone were analyzed for metals content. Protein concentrations were determined by the biuret method (18), with bovine serum albumin (Sigma) as the standard. The results with the biuret method indicated that the Bradford method underestimated the carbonic anhydrase protein concentration by a factor of 2.

Steady-state kinetics.

Initial rates of CO2 hydration were determined by stopped-flow spectroscopy (KinTek stopped-flow apparatus; State College, Pa.) at 25°C, using the changing pH indicator method (29). Saturated solutions of CO2 were prepared by bubbling CO2 into distilled, deionized water at 25°C, and the CO2 concentration was varied from 6 to 24 mM by mixing with an appropriate volume of N2-saturated water. CO2 hydration activity was determined at pH 8.5 with a final Cab concentration of 2 μM. The absorbance change was measured at 578 nm in a final buffer concentration of 50 mM TAPS (N-tris[hydroxymethyl]methyl-3-aminopropanesulfonic acid; pKa 8.4)–28.6 mM Na2SO4–48.6 μM m-cresol purple. The steady-state parameters kcat and kcat/Km and their standard errors were determined by fitting the observed initial rates (corrected for the uncatalyzed reaction) to the Michaelis-Menten equation, using the Kaleidagraph program (Synergy Software, Reading, Pa.).

Western blot analysis.

M. thermoautotrophicum ΔH cells were suspended in 50 mM potassium phosphate (pH 6.8) and passed twice through a chilled French pressure cell at 138 MPa, and the cell extract was collected following centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 20 min to remove unbroken cells. Polyclonal antibodies directed against the purified heterologously produced Cab were raised in New Zealand White rabbits (Cocalico Biological Corp., Reamstown, Pa.). Cell extract proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE on 12.0% gels and electrotransferred to a polyvinylidene membrane (Immobilon; Millipore) as recommended (Bio-Rad). Additional protein sites were blocked by incubating the membrane in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) containing 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20, and 10% evaporated milk. Primary antisera raised to Anabaena strain PCC7120 carbonic anhydrase (α type) (50), the M. thermoautotrophicum ΔH Cab (β type), and the M. thermophila Cam (γ type) (3) were used at dilutions of 1:10,000, 1:5,000, and 1:10,000, respectively. A 1:7,500 dilution of anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G-alkaline phosphatase conjugate was used. The antibody-antigen complex was detected with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate and 4-nitroblue tetrazolium chloride as recommended by the supplier (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals).

Materials.

All chemicals were of reagent grade and purchased from Sigma or Fisher Scientific. Highly purified human carbonic anhydrase was obtained from Sigma. T4 DNA ligase and restriction enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs. Gel filtration and SDS-PAGE molecular mass standards were from Sigma. Oligonucleotide primers were obtained from and sequencing was performed at the Nucleic Acid Facility, Pennsylvania State University.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Heterologous production and purification of Cab.

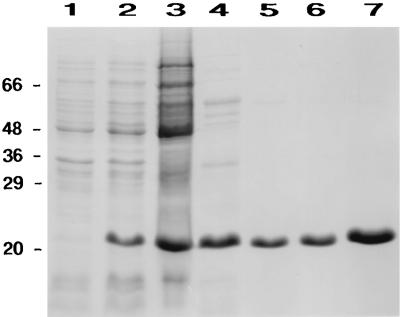

Recently, genome sequencing (41, 46) of the thermophilic, obligately chemolithoautotrophic methanoarchaeon M. thermoautotrophicum ΔH revealed an open reading frame (ORF) with a deduced sequence 34.3% identical to that of CynT, the β carbonic anhydrase of E. coli (20). The gene, designated cab (carbonic anhydrase beta), was PCR amplified and cloned into the pET16b− vector to produce plasmid pMBTCA13 and then expressed in E. coli by using the T7 promoter/polymerase expression system (54, 55). Greater than 95% of the carbonic anhydrase activity was recovered in the soluble fraction after ultracentrifugation of the E. coli cell extract for 2 h at 100,000 × g. By taking advantage of the thermal stability of Cab, a major purification step was the incubation of the high-speed (ultracentrifuge) soluble supernatant at 65°C for 15 min followed by centrifugation to remove the denatured E. coli proteins. The heterologously produced enzyme was purified 13-fold to apparent homogeneity (Table 1), as indicated by a single polypeptide band after SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Purification of Cab heterologously produced in E. coli

| Step | Total activity (U)a | Protein (mg)b | Sp act (U/mg) | Recovery (%) | Purification (fold) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell extractc | 896.4 | 298.8 | 3.0 | 100 | 1 |

| Heated cell extractd | 715.5 | 79.5 | 9.0 | 80 | 3 |

| Mono Qe | 624.0 | 16.0 | 39.0 | 70 | 13 |

Measured by the electrometric method (58). One unit = (t0 − t)/t, where t0 is the time for the uncatalyzed reaction and t is the time of the catalyzed reaction.

Determined by the Bradford assay, which resulted in protein concentrations twofold higher than those determined by the biuret assay.

After ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 2 h.

After incubation at 65°C for 15 min followed by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 15 min.

After the second Mono Q step.

FIG. 1.

SDS-PAGE of heterologously produced Cab at various steps during purification from E. coli. Lane 1, 20 μg of cell extract protein from E. coli carrying pMBTCA13 prior to induction; lane 2, 20 μg of cell extract protein from E. coli carrying pMBTCA13 3 h after induction; lane 3, 100 μg of cell extract protein after centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 2 h; lane 4, 16 μg of protein after incubation at 65°C for 15 and centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 20 min; lane 5, 7 μg of protein from the first Mono Q step; lane 6, 7 μg of protein from the second Mono Q step; lane 7, 14 μg of protein from the second Mono Q step. Positions of molecular mass markers are shown on the left in kilodaltons.

Most dicotyledonous plant carbonic anhydrases that have been purified and characterized are reported to be dependent on a reducing agent to retain catalytic activity. The oxidized, inactive pea enzyme could be reactivated to only 60% of the original activity by the addition of a reducing agent (26, 27). Purification in the presence of reducing agents or the addition of reducing agents to purified Cab had no affect on the catalytic activity (47). Thus, Cab joins the other two prokaryotic β carbonic anhydrases that are insensitive to oxidation (20, 49).

Biochemical characterization. (i) Thermostability.

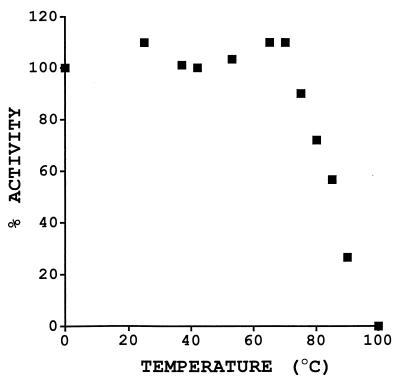

The activity of Cab was stable when the enzyme was incubated for 15 min at temperatures up to 75°C (Fig. 2). This is not surprising since the optimal growth temperature for M. thermoautotrophicum ΔH is between 65 and 75°C (8). Little activity was recovered when the enzyme was incubated at temperatures of 90°C or higher. Thus, Cab is the most thermostable carbonic anhydrase yet characterized.

FIG. 2.

Thermostability of Cab. Cab was incubated for 15 min at the indicated temperatures and cooled on ice, and activity was determined at 25°C by the electrometric method (58). Activity is represented as a percentage of the activity of a sample maintained on ice throughout the experiment (38.5 U/mg).

(ii) Inhibition.

Iodide, nitrate, and azide are potent inhibitors of Cab (IC50 [concentrations of inhibitor resulting in 50% inhibition of enzyme activity, determined by a semilogarithmic plot of percentage of inhibition versus logarithmic concentration of inhibitor] of 1.0, 1.5, and 2.1 mM, respectively); however, chloride and sulfate, which inhibit plant β carbonic anhydrases, had no effect on the activity of Cab (47). The insensitivity to chloride and sulfate suggests a fundamental difference in the active sites of Cab and the plant enzymes. The effect of these anions on the two other known prokaryotic β carbonic anhydrases has not been reported. The insensitivity to chloride and sulfate is also observed for Cam from M. thermophila, the only other known methanoarchaeal carbonic anhydrase (2, 3).

Although all three classes of carbonic anhydrase are inhibited by the same types of compounds, inhibition constants vary considerably between individual enzymes. Detailed structural information for enzyme-inhibitor complexes exists only for the α class carbonic anhydrases, primarily human isozymes CA I and CA II (37). Anions prevent formation of the coordinated hydroxide ion, which is essential in the catalytic hydration of CO2 (35, 36). Nitrate belongs to a group of anions that appear to bind close to the metal ion without displacing the critical zinc-bound water molecule necessary for activity (38). Conversely, another group of anions including chloride, iodide, and azide directly coordinate to the metal ion and displace the zinc-bound water molecule (32, 40). The α class carbonic anhydrases are only weakly inhibited or not inhibited by divalent anions such as sulfate (43); thus, sulfate is only an inhibitor for plant enzymes belonging to the β class.

Cab is also susceptible to inhibition by the sulfonamides acetazolamide and ethoxyzolamide (IC50s of 0.06 and 0.007 mM, respectively). Sulfonamides inhibit the activity of carbonic anhydrases by binding to the active site zinc via the nitrogen atom of the sulfonamide group (37). Differences in the affinity of the sulfonamides have been explained by subtle differences in the active sites of the human isozymes; therefore, it is not surprising to see differences between the different classes of carbonic anhydrases.

(iii) Esterase activity.

Some carbonic anhydrases belonging to the α family catalyze the reversible hydrolysis of esters. With p-nitrophenylacetate as a substrate, commercially available human CA II showed an esterase activity of 38.2 mol of p-nitrophenylacetate per min per mol of enzyme. In contrast, Cab showed no detectable esterase activity (<0.01 mol of p-nitrophenylacetate per min per mol of enzyme); thus, Cab joins other carbonic anhydrases from the β class in lacking any detectable esterase activity (20, 30). Cam, the only characterized carbonic anhydrase of the γ class, also lacks an esterase activity (3).

(iv) Subunit composition.

A subunit molecular mass of 21 kDa was estimated by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1). A subunit molecular mass of 18.9 kDa was calculated on the basis of the amino acid composition deduced from the nucleotide sequence. Native gel filtration chromatography of Cab gave an estimated molecular mass of 90 kDa. Given a calculated subunit molecular mass of 18.9 kDa, these results suggest that the native enzyme is a tetramer.

According to quaternary structure, the β carbonic anhydrases are divided into three groups represented by the dicotyledon, monocotyledon, and nonplant enzymes (7). The native molecular masses of the enzymes from dicotyledenous plants have been reported to vary between 140 and 250 kDa, with a subunit mass of 24 to 34 kDa. The oligomeric state has been recently shown to be an octamer, consisting of two covalently linked tetramers (7). Carbonic anhydrases from monocotyledenous plants have been suggested to be dimers (19). CynT from E. coli has been reported to be either a tetramer or a dimer, depending on the experimental conditions (20), and the β carbonic anhydrase identified in the unicellular green alga Coccomyxa sp. has also been shown to be a tetramer (23). Thus, the quaternary structure of Cab is like that of the enzymes from E. coli and Coccomyxa sp.

(v) Metals analysis.

The carbonic anhydrases from the α, β, and γ classes contain one zinc per enzyme subunit and are thought to have a common zinc hydroxide mechanism for catalysis. A comprehensive metals analysis (20 elements) of Cab was performed by plasma emission spectroscopy using two independent enzyme preparations with similar specific activities. Since the Bradford assay was found to underestimate the concentration of Cab by a factor of 2, the biuret assay was used to determine protein concentrations for the metals analysis. The analysis revealed 1.01 and 0.97 Zn per subunit of Cab for preparations I and II, respectively, suggesting Cab contains one zinc per subunit.

Kinetic properties of Cab.

Kinetic parameters for the CO2 hydration activity were measured at 25°C in a stopped-flow spectrophotometer. The values for Cab are presented in Table 2 along with the values for the kinetically characterized β-class carbonic anhydrases as well as those for the only two kinetically characterized prokaryotic enzymes besides Cab, the prototypical γ-class methanoarchaeal enzyme and the α-class neisserial enzyme. The Km value for CO2 is similar to those of the characterized enzymes of the β class; however, the kcat for Cab is lower than those for the carbonic anhydrases isolated from higher plants (6, 34) and the unicellular green alga Coccomyxa sp. (23) (Table 2). One possible reason for the greater than 10-fold difference in kcat and in the catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) may be that the assay temperature was more than 40°C below the optimal growth temperature of M. thermoautotrophicum, which is between 65 and 75°C. The optimal temperature for Cab activity is expected to be near the growth temperature; however, the decreased solubility of CO2 at these temperatures under atmospheric pressure precludes the determination of accurate kinetic parameters above 25°C.

TABLE 2.

Distribution and properties of carbonic anhydrases

| Enzyme | Domain | Class | Molecular mass (kDa)

|

Subunit composition | Kinetic parameterc

|

Reference(s) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subunita | Holoenzymeb | kcat (s−1) | Km (mM) | kcat/Km (s−1 M−1) | |||||

| Carbonic anhydrase from: | |||||||||

| Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum | Archaea | β | 18.9 | 90 | Tetramer | 1.7 × 104 | 2.9 | 5.9 × 106 | This study |

| Escherichia coli | Bacteria | β | 24.7 | 90 | Tetramer | ND | ND | ND | 20 |

| Pisum sativum (pea) | Eucarya | β | 24.2 | 180 | Octamer | 2.3 × 105 | 2.5 | 9.2 × 107 | 6 |

| Populus tremula × Populus tremuloides | Eucarya | β | 24.8 | 205 | Octamer | 1.8 × 105 | 3.0 | 6.0 × 107 | 34 |

| Coccomyxa sp. | Eucarya | β | 24.7 | 100 | Tetramer | 3.8 × 105 | 4.7 | 8.1 × 107 | 23 |

| Methanosarcina thermophila | Archaea | γ | 22.9 | 74 | Trimer | 7.7 × 104 | 14.8 | 5.5 × 106 | 1 |

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Bacteria | α | 25.3 | 25 | Monomer | 1.1 × 106 | 20 | 5.5 × 107 | 13 |

| Human CA II | Eucarya | α | 29.3 | 30 | Monomer | 1.0 × 106 | 8.3 | 1.2 × 108 | 29, 52 |

Calculated from deduced amino acid sequences. The subunit molecular masses of the P. sativum and P. tremula × P. tremuloides enzymes were based on the deduced amino acid sequence minus the chloroplast transit peptide sequence.

Determined by gel filtration.

kcat and Km for CO2 in the direction of CO2 hydration were determined between pH 8.5 and 9.0 at 25°C. ND, not determined.

The values determined for Cab are the first kinetic parameters reported for a prokaryotic β carbonic anhydrase. Among the prokaryotic carbonic anhydrases that have been kinetically characterized, the N. gonorrhoeae α-class enzyme (13) has the highest kcat value and is as catalytically efficient (kcat/Km) as the high-activity human isozyme, CA II (29, 52). The Km values for CO2 for the α and γ prokaryotic carbonic anhydrases (1, 13) are over fivefold greater than that of Cab, suggesting that Cab may have a physiological role distinct from those of the prokaryotic α- and γ-class enzymes.

Alignment of β-class carbonic anhydrases.

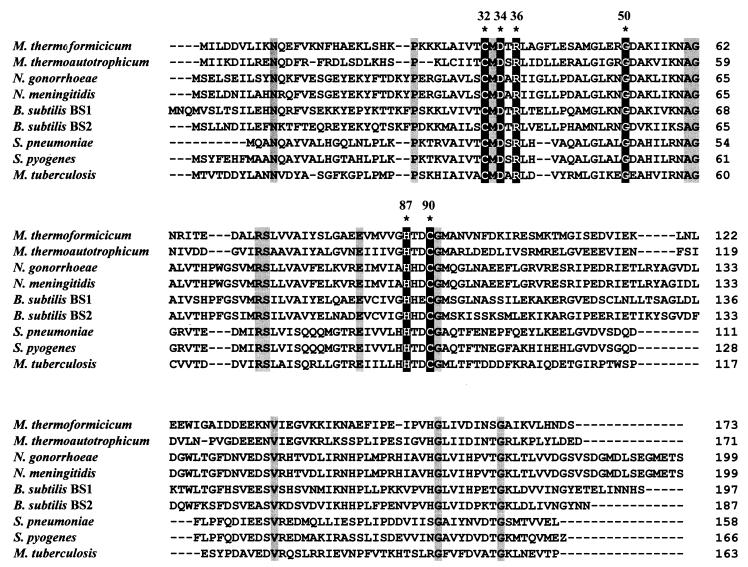

On the basis of amino acid sequence comparisons, carbonic anhydrases belong to three genetically distinct classes (α, β, and γ) that evolved independently (22). We had previously identified 51 ORFs with deduced sequences having significant identity and similarity to the sequences of Cab from M. thermoautotrophicum ΔH by Blastp and tBLASTn searches of the nonredundant sequence database at the National Center for Biotechnology Information and the finished and unfinished microbial genome sequences (48). Of the 26 ORFs identified from species of the Bacteria and Archaea domains, only 2 are known to encode documented carbonic anhydrases (20, 49). Distinct from all other β carbonic anhydrase sequences, the plant sequences form two monophyletic groups representing monocotyledons and dicotyledons. The remaining sequences form four clades, and Cab is found in one of the two clades composed exclusively of prokaryotic sequences.

An alignment of the sequences that form a clade with Cab is shown in Fig. 3. Indicated in this alignment are six amino acid residues that are 100% conserved among the 62 sequences of putative β carbonic anhydrases identified in the search. Extended X-ray absorption fine structure studies of the spinach enzyme suggest that the active-site zinc is coordinated by two cysteine residues and one histidine residue (10, 42). Cysteine-32, histidine-87, and cysteine-90 of Cab are conserved among all of the sequences and would be expected to be the ligands for the active-site zinc in Cab; however, a structure is needed for definitive proof. Three other residues in Cab that are conserved among these sequences are asparagine-34, arginine-36, and glycine-50, suggesting an important structural or catalytic role. The alignment shown in Fig. 3 reveals additional residues that are 100% conserved among the members of this clade.

FIG. 3.

Comparison of the deduced sequence of Cab with the deduced sequences of putative carbonic anhydrases. The deduced amino acid sequences were aligned by using ClustalX (56). Abbreviations and GenBank accession numbers or databases: B. subtilis BS1, 1945660; B. subtilis BS2, 2293156; M. thermoautotrophicum ΔH, 1272331; M. thermoformicicum, 1279772; Myobacterium tuberculosis, 1722951; N. gonorrhoeae, University of Oklahoma Genome Center; N. meningitidis, Sanger Centre; Streptococcus pneumoniae, The Institute for Genomic Research; Streptococcus pyogenes, University of Oklahoma Genome Center. Identical amino acids are lightly shaded; darkly shaded amino acids in white are conserved among all β carbonic anhydrase sequences. Numbering refers to that of the Cab amino acid sequence.

Expression of Cab in M. thermoautotrophicum.

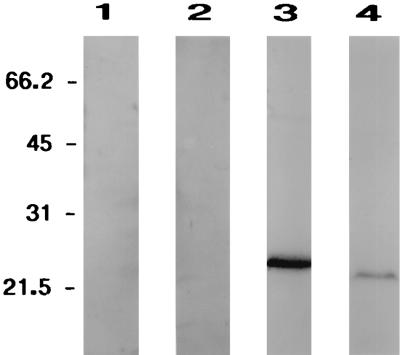

We have previously shown that carbonic anhydrase activity (0.8 U/mg) is present in M. thermoautotrophicum cell extract (48). Western blot analysis was performed to determine if this activity is at least in part due to expression of Cab in M. thermoautotrophicum. In addition to an antiserum raised against Cab, antisera raised against the Anabaena strain PCC7120 α carbonic anhydrase and M. thermophila γ carbonic anhydrase (Cam) were used. A cross-reacting protein of the correct size for Cab was detected by Western blot analysis using the antiserum raised to Cab (Fig. 4). No proteins cross-reacting to the antiserum raised against the α carbonic anhydrase were detected; however, a protein cross-reacting to the antiserum raised against the γ carbonic anhydrase from M. thermophila was detected (Fig. 4). Analysis of the genome sequence of M. thermoautotrophicum revealed an ORF encoding a protein with 30.7% identity to Cam; however, it is not yet known if the protein encoded by this ORF has carbonic anhydrase activity. Thus, the carbonic anhydrase activity detected in M. thermoautotrophicum may be due to the presence of both β and γ carbonic anhydrases.

FIG. 4.

Western blot analysis for carbonic anhydrase in cell extract protein from M. thermoautotrophicum. Each lane was loaded with 50 μg of M. thermoautotrophicum ΔH cell extract protein and probed with either preimmune serum (lane 1) or antiserum to the Anabaena strain PCC7120 α carbonic anhydrase (lane 2), M. thermoautotrophicum β carbonic anhydrase Cab (lane 3), or M. thermophila γ carbonic anhydrase Cam (lane 4); detection was with anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G-alkaline phosphatase conjugate. Positions of molecular mass markers are indicated to the left in kilodaltons.

Cab is the first documented carbonic anhydrase from a CO2-reducing chemolithoautotrophic methanoarchaeon. These microbes have a high demand for CO2 in both catabolic and anabolic reactions, suggesting that carbonic anhydrase may be essential to deliver CO2 to the cell and concentrate it in the vicinity of CO2-utilizing enzymes. This is analogous to the role of carbonic anhydrase in photosynthetic organisms in which the enzyme is essential for efficient CO2 transport into the cell and elevation of the CO2 concentration near the active site of the CO2-fixing enzyme ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase (5). For example, Cab could convert bicarbonate to CO2, the substrate for the formylmethanofuran dehydrogenase (57) catalyzing the first committed step of methanogenesis. In addition to utilizing CO2 in its energy metabolism, M. thermoautotrophicum is a chemolithoautotroph, synthesizing cell carbon from CO2. The central anabolic pathways for M. thermoautotrophicum are the autotrophic pathway for acetyl coenzyme A biosynthesis and the incomplete reductive tricarboxylic acid cycle (44). Some of the CO2 fixation enzymes in these pathways utilize HCO3−; thus, interconversion between CO2 and HCO3− is another potential role for Cab. Similar mechanisms requiring carbonic anhydrase may also facilitate the growth of anaerobes which obtain energy by reducing carbon dioxide to either acetate (Acetobacterium woodii and Clostridium thermoaceticum) or methane (Methanobacterium formicicum and Methanospirillum hungateii). In fact, carbonic anhydrase activity has been detected in these anaerobes, and Western blot analysis has identified proteins that cross-react to antisera raised against Cab (12, 48).

Conclusions.

The results presented here are the first demonstration of plant-type (β-class) carbonic anhydrases in the Archaea. The heterologously produced carbonic anhydrase from M. thermoautotrophicum, designated Cab, is the first documented β carbonic anhydrase from a thermophile and is thermostable at temperatures up to 75°C. It is anticipated that the thermophilic nature of Cab will facilitate the determination of a crystal structure, the first for any enzyme of the β class. The presence of β carbonic anhydrase in a thermophilic archaeon suggests that this enzyme may play a more widespread role in prokaryotic physiology than previously thought.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank John Coleman and Birgit Alber for the generous gifts of antisera. We also thank Cheryl Ingram-Smith for critical reading of the manuscript.

The work was supported by NIH-GM44661 and NASA-Ames cooperative agreement NCC-1057.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alber, B. E., C. M. Colangelo, J. Dong, C. M. V. Stalhandske, T. T. Baird, C. Tu, C. A. Fierke, D. N. Silverman, R. A. Scott, and J. G. Ferry. Kinetic and spectroscopic characterization of the gamma carbonic anhydrase from the methanoarchaeon Methanosarcina thermophila. Biochemistry, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Alber B E, Ferry J G. A carbonic anhydrase from the archaeon Methanosarcina thermophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6909–6913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.6909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alber B E, Ferry J G. Characterization of heterologously produced carbonic anhydrase from Methanosarcina thermophila. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3270–3724. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.11.3270-3274.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armstrong J M, Myers D V, Verpoote J A, Edsall J T. Purification and properties of human erythrocyte carbonic anhydrases. J Biol Chem. 1966;241:5137–5149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Badger M R, Price G D. The role of carbonic anhydrase in photosynthesis. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1994;45:369–392. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bjorkbacka H, Johansson I M, Forsman C. Possible roles for His 208 in the active-site region of chloroplast carbonic anhydrase from Pisum sativum. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1999;361:17–24. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1998.0961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bjorkbacka H, Johansson I M, Skarfstad E, Forsman C. The sulfhydryl groups of Cys 269 and Cys 272 are critical for the oligomeric state of chloroplast carbonic anhydrase from Pisum sativum. Biochemistry. 1997;36:4287–4294. doi: 10.1021/bi962825k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boone D R, Whitman W B, Rouviere P. Diversity and taxonomy of methanogens. In: Ferry J G, editor. Methanogenesis: ecology, physiology, biochemistry, and genetics. London, England: Chapman & Hall; 1993. pp. 35–80. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boriack-Sjodin P A, Heck R W, Laipis P J, Silverman D N, Christianson D W. Structure determination of murine mitochondrial carbonic anhydrase V at 2.45-Å resolution: implications for catalytic proton transfer and inhibitor design. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10949–10953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.10949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bracey M H, Christiansen J, Tovar P, Cramer S P, Bartlett S G. Spinach carbonic anhydrase: investigation of the zinc-binding ligands by site-directed mutagenesis, elemental analysis, and EXAFS. Biochemistry. 1994;33:13126–13131. doi: 10.1021/bi00248a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braus-Stromeyer S A, Schnappauf G, Braus G H, Gossner A S, Drake H L. Carbonic anhydrase in Acetobacterium woodii and other acetogenic bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7197–7200. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.22.7197-7200.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chirica L C, Elleby B, Jonsson B H, Lindskog S. The complete sequence, expression in Escherichia coli, purification and some properties of carbonic anhydrase from Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Eur J Biochem. 1997;244:755–760. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eriksson A E, Liljas A. Refined structure of bovine carbonic anhydrase-III at 2.0 angstrom resolution. Proteins Struct Funct Genet. 1993;16:29–42. doi: 10.1002/prot.340160104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferry J G. Enzymology of one-carbon metabolism in methanogenic pathways. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1999;23:13–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1999.tb00390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fukuzawa H, Fujiwara S, Tachiki A, Miyachi S. Nucleotide sequences of two genes CAH1 and CAH2 which encode carbonic anhydrase polypeptides in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6441–6442. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.21.6441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fukuzawa H, Fujiwara S, Yamamoto Y, Dionisio-Sese M L, Miyachi S. cDNA cloning, sequence, and expression of carbonic anhydrase in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii—regulation by environmental CO2 concentration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4383–4387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.11.4383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gornall A G, Bardawill C J, David M M. Determination of serum proteins by means of the Biuret reaction. J Biol Chem. 1948;177:751–766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graham D, Reed M L, Patterson B D, Hockley D G, Dwyer M R. Chemical properties, distribution, and physiology of plant and algal carbonic anhydrases. Annu N Y Acad Sci. 1984;429:222–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1984.tb12340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guilloton M B, Korte J J, Lamblin A F, Fuchs J A, Anderson P M. Carbonic anhydrase in Escherichia coli. A product of the cyn operon. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:3731–3734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hakansson K, Carlsson M, Svensson L A, Liljas A. Structure of native and apo carbonic anhydrase-II and structure of some of its anion-ligand complexes. J Mol Biol. 1992;227:1192–1204. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90531-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hewett-Emmett D, Tashian R E. Functional diversity, conservation, and convergence in the evolution of the α-, β-, and γ-carbonic anhydrase gene families. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 1996;5:50–77. doi: 10.1006/mpev.1996.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hiltonen T, Bjorkbacka H, Forsman C, Clarke A K, Samuelsson G. Intracellular beta-carbonic anhydrase of the unicellular green alga Coccomyxa. Cloning of the cDNA and characterization of the functional enzyme overexpressed in Escherichia coli. Plant Physiol. 1998;117:1341–1349. doi: 10.1104/pp.117.4.1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holmquist B. Elimination of adventitious metals. Methods Enzymol. 1988;158:6–12. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)58042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang S, Xue Y, Sauer-Eriksson E, Chirica L, Lindskog S, Jonsson B H. Crystal structure of carbonic anhydrase from Neisseria gonorrhoeae and its complex with the inhibitor acetazolamide. J Mol Biol. 1998;28:301–310. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johansson I M, Forsman C. Kinetic studies of pea carbonic anhydrase. Eur J Biochem. 1993;218:439–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johansson I M, Forsman C. Solvent hydrogen isotope effects and anion inhibition of CO2 hydration catalysed by carbonic anhydrase from Pisum sativum. Eur J Biochem. 1994;224:901–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.00901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kannan K K, Notstrand B, Fridborg K, Lovgren S, Ohlsson A, Petef M. Crystal structure of human erythrocyte carbonic anhydrase B. Three-dimensional structure at a nominal 2.2-Å resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:51–55. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khalifah R G. The carbon hydroxide hydration activity of carbonic anhydrase. I. Stop-flow kinetic studies on the native human isozymes B and C. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:2561–2573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kisiel W, Graf G. Purification and characterization of carbonic anhydrase from Pisum sativum. Phytochemistry. 1972;11:113–117. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kisker C, Schindelin H, Alber B E, Ferry J G, Rees D C. A left-hand beta-helix revealed by the crystal structure of a carbonic anhydrase from the archaeon Methanosarcina thermophila. EMBO J. 1996;15:2323–2330. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar V, Kannan K K, Sathyamurthi P. Differences in anion inhibition of human carbonic anhydrase I revealed from the structures of iodide and gold cyanide complexes. Acta Crystallogr. 1994;D50:731–738. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994001873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of the bacteriophage T7. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Larsson S, Bjorkbacka H, Forsman C, Samuelsson G, Olsson O. Molecular cloning and biochemical characterization of carbonic anhydrase from Populus tremula × tremuloides. Plant Mol Biol. 1997;34:583–592. doi: 10.1023/a:1005849202731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindskog S. Carbonic anhydrase. In: Eichorn G L, Marzilli L G, editors. Advances in inorganic chemistry. Vol. 4. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier/North Holland; 1982. pp. 115–170. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lindskog S. Carbonic anhydrase. In: Spiro T G, editor. Zinc enzymes. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1983. pp. 78–121. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lindskog S. Structure and mechanism of carbonic anhydrase. Pharmacol Ther. 1997;74:1–20. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(96)00198-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mangani S H, Hakansson K. Crystallographic studies of the binding of protonated and unprotonated inhibitors to carbonic anhydrase using hydrogen sulphide and nitrate anions. Eur J Biochem. 1992;210:867–871. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mori K, Ogawa Y, Ebihara K, Tamura N, Tashiro K, Kuwahara T, Mukoyama M, Sugawara A, Ozaki S, Tanaka I, Nakao K. Isolation and characterization of CA XIV, a novel membrane-bound carbonic anhydrase from mouse kidney. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:15701–15705. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.22.15701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nair S K, Christianson D W. Crystallographic studies of azide binding to human carbonic anhydrase II. Eur J Biochem. 1993;213:507–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nolling J, Pihl T D, Vriesema A, Reeve J N. Organization and growth phase-dependent transcription of methane genes in two regions of the Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum genome. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2460–2468. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.9.2460-2468.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rowlett R S, Chance M R, Wirt M D, Sidelinger D E, Royal J R, Woodroffe M, Wang Y F, Saha R P, Lam M G. Kinetic and structural characterization of spinach carbonic anhydrase. Biochemistry. 1994;33:13967–13976. doi: 10.1021/bi00251a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simonsson I, Lindskog S. The interaction of sulfate with carbonic anhydrase. Eur J Biochem. 1982;123:29–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1982.tb06494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simpson P G, Whitman W B. Anabolic pathways in methanogens. In: Ferry J G, editor. Methanogenesis: ecology, physiology, biochemistry, and genetics. London, England: Chapman & Hall; 1993. pp. 445–472. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sly W S, Hu P Y. Human carbonic anhydrases and carbonic anhydrase deficiencies. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:375–401. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.002111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith D R, Doucette-Stamm L A, Deloughery C, Lee H, Dubois J, Aldredge T, Bashirzadeh R, Blakely D, Cook R, Gilbert K, Harrison D, Hoang L, Keagle P, Lumm W, Pothier B, Qiu D, Spadafora R, Vicaire R, Wang Y, Wierzbowski J, Gibson R, Jiwani N, Caruso A, Bush D, Safer H, Patwell D, Prabhakar S, McDougall S, Shimer G, Goyal A, Pietrokovski S, Church G M, Daniels C J, Mao J-I, Rice P, Nolling J, Reeve J N. Complete genome sequence of Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum deltaH: functional analysis and comparative genomics. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7135–7155. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.22.7135-7155.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith, K. S., and J. G. Ferry. Unpublished data.

- 48.Smith, K. S., C. Jakubzick, T. S. Whittam, and J. G. Ferry. Carbonic anhydrase is widespread in prokaryotes and dates to the origin of life. Submitted for publication.

- 49.So A K, Espie G S. Cloning, characterization and expression of carbonic anhydrase from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC6803. Plant Mol Biol. 1998;37:205–215. doi: 10.1023/a:1005959200390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Soltes-Rak E, Mulligan M E, Coleman J R. Identification and characterization of a gene encoding a vertebrate-type carbonic anhydrase in cyanobacteria. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:769–774. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.3.769-774.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stams T, Nair S K, Okuyama T, Waheed A, Sly W S, Christianson D W. Crystal structure of the secretory form of membrane-associated human carbonic anhydrase IV at 2.8-Å resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13589–13594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Steiner H, Jonsson B H, Lindskog S. The catalytic mechanism of human carbonic anhydrase C: inhibition of CO2 hydration and ester hydrolysis by HCO3−. FEBS Lett. 1976;62:16–20. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(76)80006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stetter K O. Hyperthermophiles in the history of life. In: Bock G R, Goode J A, editors. Evolution of hydrothermal ecosystems on Earth (and Mars?). Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons; 1996. pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Studier F W, Moffat B A. Use of the bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase to direct selective high-level expression of cloned genes. J Mol Biol. 1986;189:113–130. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tabor S, Richardson C C. A bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase/promoter system for controlled expression of specific genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:1074–1078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.4.1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thompson J D, Gibson T J, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins D J. The Clustal X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vorholt J A, Thauer R K. The active species of ‘CO2’ utilized by formylmethanofuran dehydrogenase from methanogenic Archaea. Eur J Biochem. 1997;248:919–924. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilbur K M, Anderson N G. Electrometric and colorimetric determination of carbonic anhydrase. J Biol Chem. 1948;176:147–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]