Abstract

Introduction:

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), the most common childhood malignancy, has a relatively favorable long-term prognosis. Yet the complexity of treatment and the emotionality of the diagnosis leave families feeling unprepared for many aspects of therapy. This qualitative study aimed to identify desired elements and format of a communication resource to support patients and families facing a diagnosis of ALL.

Methods:

Semi-structured interviews of 12 parents of children receiving ALL treatment, 10 parents of survivors of ALL, and eight adolescent and young adult (AYA) survivors of ALL were conducted between February and June 2021. The interviews focused on communication experiences throughout treatment and identified domains to be addressed in a resource in development.

Results:

All participants supported the development of an interactive, electronic health (eHealth) resource to help navigate ALL treatment. They felt a website would be helpful in addressing information gaps and mitigating pervasive feelings of overwhelm. Participants specifically sought: (a) information resources to address feelings of cognitive overload; (b) practical tips to help navigate logistical challenges; (c) clear depictions of treatment choices and trajectories to facilitate decision-making; and (d) additional psychosocial resources and support. Two overarching themes that families felt should be interwoven throughout the eHealth resource were connections with other patients/families and extra support at transitions between phases of treatment.

Conclusions:

A new diagnosis of ALL and its treatment are extremely overwhelming. Patients and families unanimously supported an eHealth resource to provide additional information and connect them with emotional support, starting at diagnosis and extending throughout treatment.

Keywords: cancer, eHealth, parent pediatric, qualitative

1 |. INTRODUCTION

When a child is diagnosed with cancer, families are required to absorb vast amounts of information while emotionally overwhelmed. Most patients and parents learn about their diagnosis and treatment through extensive discussions with their care team and lengthy consent forms. These conversations and documents lay the groundwork for families’ understanding of their child’s diagnosis and the impact of treatment on short- and long-term health and quality of life.1,2 Although clinicians and families spend significant time and effort on early treatment conversations, communication gaps remain. Patients and parents recall only a small fraction of the information presented in early cancer treatment discussions,3–5 and there is suboptimal parent understanding of prognosis,6 late effects risks,7,8 and clinical trial participation.9 As a result, many parents lack the information they want and need to make decisions and prepare for their children’s future.10–12 Effective strategies are needed to improve early treatment communication so that families are equipped for what lies ahead during and after therapy.

A primary communication gap is in helping families synthesize information about the impact of a treatment regimen in a way that sets realistic expectations for the experiences of treatment and post-treatment survivorship.10,13,14 High-quality communication in pediatric cancer not only provides information, but does so in a way that supports decision-making,15 hope,16 and the ability to manage the physical and emotional effects of treatment.17 Epstein and Street have outlined six core functions of patient-centered cancer communication: exchanging information, fostering healing relationships, enabling patient self-management, managing uncertainty, responding to emotion, and making decisions.18 Several organizations have developed helpful websites and books to support the information needs of parents of children with cancer, and there are some strategies to support seminal conversations such as the Day 1 Talk and the Day 100 Talk.1,19 Yet, to our knowledge, there are no interventions to support multiple aspects of pediatric cancer communication throughout a child’s cancer treatment.20,21 One challenge to the development of communication interventions in pediatric oncology is the rarity of pediatric cancer and variability of diagnoses and treatments.

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), the most common pediatric malignancy, has survival rates of 90% achieved through 2 years of multiagent chemotherapy, with many potential acute and long-term effects of treatment.22–24 Current clinical trials for children with ALL tailor treatment based on clinical characteristics, tumor genomics, and disease response data to risk-stratify patients and determine optimal therapy. The length and complexity of ALL treatment exemplify the complicated treatment information that must be conveyed and provide an opportunity to improve communication for the most common pediatric malignancy.

We conducted this qualitative study to explore interest in and priorities for a family-centered, interactive resource to support cancer communication for families and patients with ALL. We also explored prior communication experiences to ensure that the resultant intervention supports beneficial aspects of current communication practices, while simultaneously addressing patient- and family-identified gaps.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Participants

Participants were recruited from the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute/Boston Children’s Hospital Cancer and Blood Disorders Center (DFCI/BCH). To ensure that patients and their families had faced similar clinical scenarios and treatment decisions, all included patients had been diagnosed with ALL and were treated on a DFCI ALL Consortium trial. Standard information resources provided to patients and families at the DFCI include the informed consent document and a binder of general home care strategies for pediatric cancer; some providers also share medication teaching sheets or other resources per provider preference and/or parent request.

We recruited three groups of participants. Parents of patients actively receiving treatment for ALL (abbreviated “PA”) were eligible if their child (<18 years of age at diagnosis) had been diagnosed within the last 12 months and was actively receiving cancer-directed therapy. Parents of survivors (PS), were eligible if their child had been diagnosed with ALL within the previous 5 years and at least 1 month had elapsed since completion of treatment without evidence of relapsed disease. Adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood ALL (AYA) were eligible if they had been 10–18 years old at the time of diagnosis and had completed treatment without evidence of relapse. As several families had multiple eligible family members (e.g., two parents and an AYA patient), each family determined who would participate. Participants who were non-English-speaking were excluded from this study due to interviewing constraints. Purposive sampling was used to ensure a diversity of perspectives, including age, racial/ethnic, ALL risk group, and educational diversity.

Eligible participants were approached by email or mail after obtaining permission to approach from the patient’s treating oncology team. Participants were interviewed from February 2021 to June 2021 and received a $20 gift card as a token of appreciation. Interviews occurred by phone or remote video call. The Institutional Review Board of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute approved this study and provided a waiver of written documentation of consent.

2.2 |. Procedure

Individual semi-structured interviews were conducted by interviewers trained in qualitative interview techniques (Katie A. Greenzang and Madison L. Scavotto). The interview guide included open-ended questions focusing on participants’ recollection of the conversations they had about diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship, as well as their perspectives on written informational materials (Table S1). Participants were asked their thoughts about a communication resource and optimal format and content. Probing questions were asked for clarification or elaboration. Continuous analysis was performed, and recruitment continued until meaning saturation was achieved.25

3 |. DATA ANALYSIS

All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and coded line-by-line using standard, comprehensive, directed thematic qualitative analysis.26 Questions from the interview guide served as the framework for the predetermined coding structure, and drawing from grounded theory, we used open coding and constant comparison to identify emerging themes.27 The final code book was developed and iteratively revised through recurrent meetings with the study team. Two authors (Sarah F. Schlegel and Madison L. Scavotto) individually coded seven transcripts. When the κ statistic of the dual-coded interviews indicated high interrater reliability (>0.8),28 the coders independently coded the remainder of the interviews. Team meetings occurred throughout the coding process to discuss and resolve discrepancies, ensuring both credibility and dependability. The study team reviewed all coded data, looking within and across participant types, to identify key contexts and themes. Data analysis and management were supported by NVivo (QSR International, Version 1.4.1, 2021).

4 |. RESULTS

We approached 58 families, and 26 families consented for at least one family member to participate. In total, 30 individuals participated in 28 interviews (Figure S1): 12 PA, 10 PS, and eight AYAs. Two families opted for a single interview with both parents, and two AYA participants had a corresponding parent participate in a separate interview. See Tables 1 and 2 for participant characteristics. There were no notable differences in the communication experiences or desired elements or format of a communication resource between the three groups of participants; all expressed similar needs and preferences.

TABLE 1.

Participant characteristics–parents (22 parents participated in 20 discrete interviews as two families opted for a single interview with both parents)

| Parent characteristics (N = 22)a |

N (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 18 (82) |

|

| |

| Age at interview | |

| <40 years | 13 (59) |

|

| |

| Race | |

| Asian | 4 (18) |

| Black | 2 (9) |

| Other/mixed race | 1 (5) |

| White | 15 (68) |

|

| |

| Ethnicity | |

| Asian Indian | 3 (14) |

| Egyptian | 1 (5) |

| Hispanic | 2 (9) |

| Jewish-Ashkenazi | 1 (5) |

| Pakistani | 1 (5) |

| Non-Hispanic | 14 (64) |

|

| |

| Highest level of education completed | |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 14 (64) |

|

| |

| Characteristics of children of participating parents (N = 20) | |

| Gender | |

| Female | 8 (40) |

|

| |

| Age at diagnosis in years | |

| Median, range | 4.5 (1–13) |

|

| |

| Cancer diagnosis | |

| B-cell ALL | 15 (75) |

| T-cell ALL | 5 (25) |

|

| |

| Final protocol risk group | |

| Low risk | 5 (25) |

| Intermediate risk | 5 (25) |

| High risk | 7 (35) |

| Very high risk | 3 (15) |

|

| |

| Treatment status | |

| In active therapy | 10 (50) |

Abbreviation: ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

Participants self-reported gender and race/ethnicity in their own words, not from prespecified categories. Disease characteristics were extracted by chart review.

Table 2.

AYA participant characteristics (two of the AYA participants had a corresponding parent participate in a separate interview)

| AYA characteristics (N = 8)a | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Genderb | |

| Female | 3 (38) |

|

| |

| Age at interview | |

| Median, range | 16.5 (13–19) |

|

| |

| Race | |

| Multiracial | 1 (13) |

| White | 7 (88) |

|

| |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 1 (13) |

| Jewish | 1 (13) |

| Non-Hispanic | 6 (75) |

|

| |

| Cancer diagnosis | |

| B-cell ALL | 5 (63) |

| T-cell ALL | 3 (38) |

|

| |

| Final protocol risk group | |

| Low risk | 3 (38) |

| Intermediate risk | 2 (25) |

| High risk | 2 (25) |

| Very high risk | 1 (13) |

Abbreviations: ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AYA, adolescent and young adult.

Participants self-reported gender and race/ethnicity in their own words, not from prespecified categories. Disease characteristics were extracted by chart review.

One patient was born biologically female but identifies as transgender male.

Although participants valued the thoughtful communication they had with their oncology providers, all 30 participants felt that an interactive resource would provide valuable additional information and support. When queried about the optimal format, they all supported creation of an electronic health (eHealth) resource, specifically a website, as they wanted something that could be accessed on their phones or computers at various locations without the need to carry around binders of paperwork. While some also requested a single-page printed information sheet to support the initial informed consent process, all participants felt an interactive website would be optimal for all other aspects of communication so that they could turn to it with different questions at different times.

“I mean the doctors gave us enough information, but us being not technical, being not from a medical world, we were not too sure what everything meant. They tried to water it down, but those meetings, it’s hard to understand in one-hour meetings what everything means. So, if we had like a website to go to, we would’ve got better information maybe.” (PS #11)

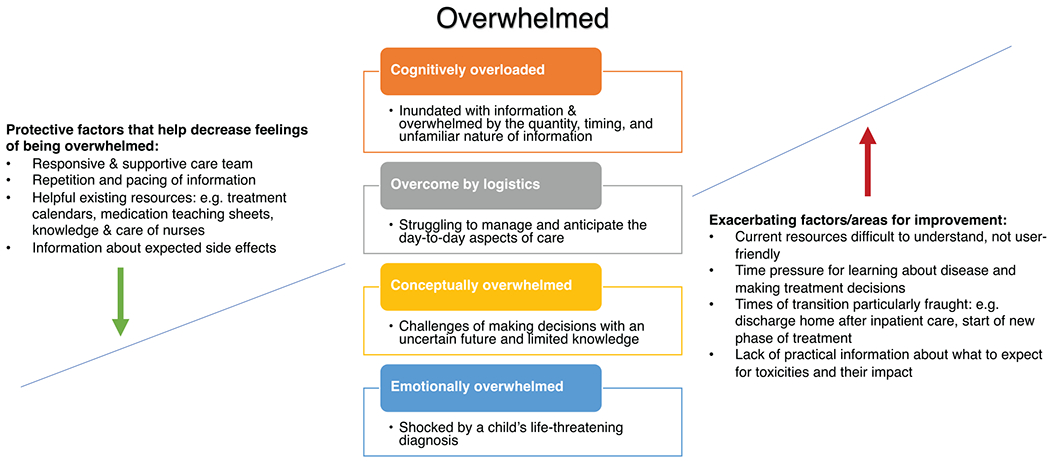

Participants uniformly felt overwhelmed by the cancer diagnosis and by all that treatment entailed (Figure 1). This feeling of shock impaired their ability to absorb information. Therefore, they sought additional resources to help mitigate the emotionality of the diagnosis, and to provide information.

FIGURE 1.

Overwhelming aspects of a new acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) diagnosis, and protective and exacerbating factors

There were four primary ways in which participants felt overwhelmed, and their desired interventions mapped to these four areas (Table 3):

TABLE 3.

Desired elements of an eHealth resource

| Themes | Example quotes |

|---|---|

| Central source of information about diagnosis and treatment | • “But having those resources available online. We spend a lot of time in the hospital waiting and sitting around, so having mobile access and website access, I think, is–the–for me, the more information the better, whether I need all of that, or whether the information I’m looking for is more toward the technical side, or if somebody else is maybe focusing more toward the emotional impact. It varies from kid to kid, and I think it really comes down to the parents’ level, not of interest but, of how they kind of attack these problems, and then what their particular child needs. So, having a multitude of those resources available, I think, is really important.” (PS #4) • “You don’t understand it until you start doing it, and it’s sort of like being thrown into the water never having learned how to swim. There’s no preparation. You don’t even have a life preserver. So yes. I do think that would be a great idea to have… this protected website. You can go in there and go on a tab and say, this is—but then like you said, zoom out so you can see where you are in the whole scheme of things.” (PA #24) |

| Practical and logistical information to support home care | • “There’s no playbook for when your kid has cancer and I wish that even the more like tactical, practical things I just knew, like here’s what you should pack. Here’s what you should just keep in the car.” (PS #1) • “… if it could have all the medications in it and you tap on it and I guess it says what it does and stuff. That would have been super helpful in the beginning. I guess what it does and what some of the side effects are.” (AYA #23) |

| Envisioning the future to support decision-making and an understanding of the “big picture” | • “I have probably a book-thick paperwork of each and every phase. And I think that’s great, and I do refer to it often. But initially, to have something that maybe looked more like an outline. Like, you know, first year this will go on for this many months, and then you’re gonna be moving to this… But I think having something a little bit shorter just to say like, this is what you’re gonna look at for this, might help.” (PA #17) |

| Emotional and psychosocial support | • “…the social-emotional for the child and the parent. Not for me, but more for my husband. I know that he struggled and I’m like, I don’t know where—book a—find a psychologist and just book an appointment with whoever. But I know that there might’ve been places that he could’ve been referred to, but I didn’t really have that readily available. But again, I didn’t ask, and he wasn’t gonna ask.” (PS #2) |

| Hearing from other patients/families | • “And honestly, talking to a doctor is great, but talking to somebody who’s already been through it is just so much more helpful. Because they talk in your—the way you’re feeling and thinking and they already went through it and they can tell you what to expect. Doctors can tell you what to expect, but they don’t really know because they’ve never done it.” (PS #6) |

| Times of transition | • “And I think that if I knew somebody that was getting diagnosed—a kid with cancer right now, I would immediately tell them about certain resources that they should know about while they are in the hospital for that month to prepare themselves for when they get out of the hospital. Because when you get out, you have to do so many things to keep your kids healthy. You have to give them tons of medications. And they can’t really tell you—they don’t really tell you what’s gonna happen. We didn’t know anything, actually. And we were really feeling not prepared at all.” (PS #7) |

Abbreviations: AYA, adolescent and young adult; eHealth, electronic health; PA, parents of patients actively receiving treatment; PS, parents of survivors.

Cognitive overload:

Participants felt overwhelmed by the quantity and unfamiliarity of the information they received about the diagnosis and treatment.

“I was, as I said, completely overwhelmed. So, I don’t really remember the details of what we were told, because it was just so much, and I wasn’t processing any of it because I was just in panic mode.” (PS #9)

To address these feelings, participants valued a website as a central source of information to complement and build upon current information resources. In this way, they hoped for easily accessible, user-friendly, and tailored information, presented in different modalities (e.g., graphical depictions, video interviews, etc.):

“But to have one central location where people can be like, oh, look, there’s links here. Let me go to these links and check it out, to have it available. Not everybody is going to take advantage of it, but I sure as heck would have.” (PA #18)

Participants felt they were better able to absorb information when it was broken down into more manageable pieces and when it was repeated several times. Therefore, they valued a resource that could titrate information to individual needs and desired levels of detail throughout treatment.

Overcome by logistics:

Respondents felt overwhelmed by what was asked of them, from managing their own/their child’s care at home, to rethinking seemingly mundane tasks like navigating hospital parking garages and cleaning their homes.

“I would have watched 100 videos of parents telling me what did and didn’t work after coming home from induction. Everything from like, how crazy did you go cleaning your house before you brought your kid home and infection protocol stuff, to bringing siblings back in afterwards.” (PA #18)

Participants valued information about expected side effects and realistic expectations for the experience of treatment. Many participants felt less distressed by symptoms they felt prepared for and felt empowered and reassured by knowledge. Conversely, those who felt they received insufficient information about likely toxicities felt unprepared and overwhelmed.

“I had a steroid that I had to take, and it made my cheeks chubby, and I wasn’t expecting that. I was pretty upset about that.” (AYA #19)

There was a wide range of practical and logistical aspects of treatment that participants felt would be helpful to include on a website, including advice on how to get through the day in clinic, how to handle life at home during treatment, how to manage side effects, what to pack for the hospital, and what to expect from survivorship.

“… little goofy things like that that come up over these two years, like what can he do, what can he not do, what are things that are – that people have found in the past that have worked for various activities, whether it’s sports or music or something. That website could be a pretty good resource if things were categorized nicely as far as, okay, you wanna play sports, well, here’s a few things that you should be thinking about, or protective gear or whatever.” (PA #27)

Conceptually overwhelmed:

Participants felt overwhelmed by trying to anticipate the future and make good decisions. The time pressure for learning about the disease and the uncertainty of making treatment decisions, particularly about enrollment in a clinical trial, increased emotional stress.

“But the anxiety comes down to what choice is gonna be the right choice, not being able to tell the future? Is the new protocol the right choice? Is it gonna do the job and, obviously, be less damaging to him because of the medications that are used in it and the volume of medications that are used in it? Or going to the more standard treatment plan where you have different medications that are more damaging over the long-term.” (PS #4)

Many found providers, especially nurses, and existing written resources helpful for envisioning the future and the different phases of treatment. Nurses were seen as reliable and invaluable sources of information about the day-to-day experience of ALL.

“We actually found the conversation with the nurse to be the helpful thing… just having somebody who approached the conversation from the perspective of like, that you said, this is how your life is going to change. This is what you should expect while you’re here in the hospital, here’s what you should expect a couple months from now.” (PA #13)

Written materials that were particularly helpful to participants included calendars or schedules, and medication information sheets. Therefore, nearly all participants wanted visual representations of treatment and maps or trackers to understand what to expect and when.

Emotionally overwhelmed:

Patients and families struggled to process the new, life-threatening diagnosis, and the emotionality of this diagnosis often left them struggling to attend to complex information and worried about making decisions. Though many participants expressed that their care teams were supportive and attentive to both their emotional and informational needs, multiple participants wished for additional emotional supports and better and easier access to psychosocial support. The emotional burden of treatment was characterized as significant and heavy on patients, parents, and siblings, and many found it difficult to identify the right resources:

“Another thing that I think would be really good on the website would be parents’ mental health. Like mothers pretty much have PTSD after this. Like there’s - it would be really nice like to have in the website some resources for parents and their mental health… a lot of parents get divorced, you know? There’s a lot of uncomfortable things happening in your own family: your relationship with your husband, your relationship with your other kids. You know, resources for the other kids because they’re all getting pushed aside, and your main attention is just on your son who is sick.” (PS #7)

There were two overarching themes that resonated across all aspects of overwhelm, which participants felt should be addressed in the website. First, nearly all participants expressed a desire to connect with and learn from other families. Many respondents sought validation and shared experiences; some wanted access to other families to exchange questions and suggestions. Both parents and AYAs valued this lived experience.

“Doctors and social workers and all of them, they can say things, but they’ve never lived it. And hearing it from someone who’s like been through it and knows it, I feel like I would just believe it more.” (AYA #22)

Second, times of transition were particularly anxiety-inducing, such as the discharge home after the initial prolonged inpatient hospitalization, moving to a new phase of treatment, and the completion of planned therapy.

“But when we came home, we had to keep up everything. Like we had to keep up, we had to keep eye on him… Mentally I was not ready to leave the hospital, but we actually had to leave it. And it was very, very tough to like feeling the inpatient to going outpatient.” (PS #15)

Participants felt an eHealth resource could offer additional support at these transition points to address the practical and emotional aspects of different phases of treatment, and they hoped the website could include patient and family videos and testimonials.

5 |. DISCUSSION

Patients and parents dealing with ALL treatment and survivorship supported the creation of an interactive eHealth resource to provide additional information and support during this overwhelming time. Participants hoped the website could serve as a central repository of information about the sequence of treatment and side effects of medications, while also providing emotional support and connection to further trusted people and resources. Additionally, as some were concerned about the trustworthiness of information found through online web searches, they sought reliable information from pre-vetted sources.

Current outcomes of ALL therapy are excellent relative to other childhood malignancies, and risk-stratified care seeks to minimize short- and long-term toxicities of therapy for those with lowest risk disease. Yet, patients and parents are still overwhelmed by all that is asked of them during the 2 years of therapy. ALL treatment disrupts every aspect of life, and all participants in our study sought additional guidance and support to navigate both the existential and quotidian aspects of cancer treatment. They wanted answers to the questions that they worried were too mundane to trouble their care team with, and they wanted help managing emotions and challenges that felt too big to tackle in a single conversation. Patients and families are looking for resources to help them understand how their lives will be impacted in the short- and long-term.29

Although participants appreciated their care teams’ communication, all desired an additional resource that could be available anytime, with multiple approaches to sharing information–written, graphical, and video–to help support their information needs and communication with their care team. An interactive eHealth resource would not supplant or impinge on usual care provided by the care team. In fact, we envision a resource that could create space for meaningful conversations between patients, families, and their providers. We are currently conducting qualitative interviews with ALL providers to ensure that the resultant intervention meets provider and patient needs, and fits into current care practices across sites participating in the DFCI ALL Consortium.

This study was unique in evaluating the specific needs of families facing a single diagnosis, treated on the same treatment regimen, and whose initial informed consent conversations were based off the same source documents. Yet, participants in our study still had many unmet communication needs similar to those found in other studies of multiple pediatric malignancies, such as anticipatory guidance on treatment side effects, practical aspects of care, and psychosocial support.30,31 Echoing other studies, even those who felt they received excellent information from their clinical teams still valued additional resources.31,32 Notably, the desired elements of an intervention aligned with the six core functions of cancer communication outlined by Epstein and Street.18 Strategies to address these core communication functions can be harnessed, along with specific recommendations made by participants, to create a website that supports families facing ALL throughout the course of treatment and survivorship.

Beyond meeting patients’ and parents’ stated needs, and supporting decision-making,33 an interactive resource may help improve clinical outcomes. A structured caregiver educational program for parents of children with cancer in Chile improved parent knowledge, and was also associated with decreased rates of central line infections and fewer visits to the emergency department.34 Similarly, suboptimal adherence to oral 6-mercaptopurine throughout ALL therapy is a risk factor for relapse, and strategies to increase adherence that combine education and automated reminders have been tried.35,36 Some of these existing approaches could be integrated into the eHealth resource we are currently developing.

Strengths of this study include the incorporation of perspectives from a population facing the same diagnosis and treatment approach, which is often challenging to obtain given the rarity of pediatric cancer. An additional strength is the rigorous qualitative methodology with triangulation across three participant subgroups. Limitations of this study include the fact that all participants were drawn from a single urban academic center. The communication practices, multidisciplinary care team approach, and patient demographics may not reflect typical practices at other sites. Furthermore, there may be differential comfort with and access to the internet and electronic resources, particularly for more vulnerable patient groups. In future work, we will need to ensure that the resource we develop is accessible to all. We also asked participants to reflect on aspects of care and communication that may have happened months to years prior. We do not know the exact content of those conversations, and participants may have had trouble remembering long-ago details.

Although great strides have been made in the treatment of ALL, treatment is still lengthy, disruptive, and overwhelming to patients and families. The new eHealth resource we are developing will hopefully help address patient and family needs and help clinicians provide optimal communication about what to expect during treatment and beyond.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all of the patients and parents who contributed their time and perspectives.

Funding information

NCI, Grant/Award Number: K08CA245036

Abbreviations:

- ALL

acute lymphoblastic leukemia

- AYA

adolescent and young adult

- eHealth

electronic health

- PA

parents of patients actively receiving treatment

- PS

parents of survivors

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no relevant financial or non-financial conflict of interest to disclose.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information can be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of this article.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mack JW, Grier HE. The Day One Talk. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(3):563–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramirez LY, Huestis SE, Yap TY, Zyzanski S, Drotar D, Kodish E. Potential chemotherapy side effects: what do oncologists tell parents? Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;52(4):497–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ong LM, Visser MR, Lammes FB, van Der Velden J, Kuenen BC, de Haes JC. Effect of providing cancer patients with the audiotaped initial consultation on satisfaction, recall, and quality of life: a randomized, double-blind study. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(16):3052–3060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodgers CC, Stegenga K, Withycombe JS, Sachse K, Kelly KP. Processing information after a child’s cancer diagnosis - how parents learn. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2016;33(6):447–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kodish E, Eder M, Noll RB, et al. Communication of randomization in childhood leukemia trials. JAMA. 2004;291(4):470–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mack JW, Cook EF, Wolfe J, Grier HE, Cleary PD, Weeks JC. Understanding of prognosis among parents of children with cancer: parental optimism and the parent-physician interaction. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(11):1357–1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenzang KA, Cronin AM, Kang T, Mack JW. Parent understanding of the risk of future limitations secondary to pediatric cancer treatment. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65(7):e27020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carpenter K, Scavotto M, McGovern A, et al. Early parental knowledge of late effect risks in children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2022;69(2):e29473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hazen RA, Drotar D, Kodish E. The role of the consent document in informed consent for pediatric leukemia trials. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007;28(4):401–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenzang KA, Dauti A, Mack JW. Parent perspectives on information about late effects of childhood cancer treatment and their role in initial treatment decision making. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65(6):e26978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eder ML, Yamokoski AD, Wittmann PW, Kodish ED. Improving informed consent: suggestions from parents of children with leukemia. Pediatrics. 2007;119(4):e849–e859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kessel RM, Roth M, Moody K, Levy A. Day One Talk: parent preferences when learning that their child has cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(11):2977–2982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaye E, Mack JW. Parent perceptions of the quality of information received about a child’s cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(11):1896–1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Russ AJ, Kaufman SR. Family perceptions of prognosis, silence, and the “suddenness” of death. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2005;29(1):103–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mack JW, Wolfe J, Cook EF, Grier HE, Cleary PD, Weeks JC. Parents’ roles in decision making for children with cancer in the first year of cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(15):2085–2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mack JW, Wolfe J, Cook EF, Grier HE, Cleary PD, Weeks JC. Hope and prognostic disclosure. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(35):5636–5642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stinson JN, Sung L, Gupta A, et al. Disease self-management needs of adolescents with cancer: perspectives of adolescents with cancer and their parents and healthcare providers. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6(3):278–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Epstein R, Street RL Jr. Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering. American Psychological Association; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feraco AM, McCarthy SR, Revette AC, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of the “Day 100 Talk”: an interdisciplinary communication intervention during the first six months of childhood cancer treatment. Cancer. 2021;127(7):1134–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sisk BA, Mack JW, Ashworth R, DuBois J. Communication in pediatric oncology: state of the field and research agenda. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65(1):e26727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sisk BA, Schulz GL, Mack JW, Yaeger L, DuBois J. Communication interventions in adult and pediatric oncology: a scoping review and analysis of behavioral targets. PLoS One. 2019;14(8):e0221536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhatia S. Late effects among survivors of leukemia during childhood and adolescence. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2003;31(1):84–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ness KK, Armenian SH, Kadan-Lottick N, Gurney JG. Adverse effects of treatment in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: general overview and implications for long-term cardiac health. Expert Rev Hematol. 2011;4(2):185–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dixon SB, Chen Y, Yasui Y, et al. Reduced morbidity and mortality in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(29):3418–3429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hennink MM, Kaiser BN, Marconi VC. Code saturation versus meaning saturation: how many interviews are enough? Qual Health Res. 2017;27(4):591–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Creswell JW. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. 5th ed. SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ. 2000;320(7227):114–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2012;22(3):276–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paladino J, Lakin JR, Sanders JJ. Communication strategies for sharing prognostic information with patients: beyond survival statistics. JAMA. 2019;322(14):1345–1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewandowska A. The needs of parents of children suffering from cancer - continuation of research. Children (Basel). 2022;9(2):144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitchell W, Clarke S, Sloper P. Care and support needs of children and young people with cancer and their parents. Psychooncology. 2006;15(9):805–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robertson EG, Wakefield CE, Shaw J, et al. Decision-making in childhood cancer: parents’ and adolescents’ views and perceptions. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(11):4331–4340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parker K, Cottrell E, Stork L, Lindemulder S. Parental decision making regarding consent to randomization on Children’s Oncology Group AALL0932. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021;68(4):e28907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De la Maza V, Manriquez M, Castro M, et al. Impact of a structured educational programme for caregivers of children with cancer on parental knowledge of the disease and paediatric clinical outcomes during the first year of treatment. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2020;29(6):e13294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhatia S, Hageman L, Chen Y, et al. Effect of a daily text messaging and directly supervised therapy intervention on oral mercaptopurine adherence in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2014205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bhatia S, Landier W, Hageman L, et al. 6MP adherence in a multiracial cohort of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a Children’s Oncology Group study. Blood. 2014;124(15):2345–2353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.