Abstract

Objective

Aldo-keto reductase 1C3 (AKR1C3) has been postulated to be involved in androgen, progesterone, and estrogen metabolism. Aldo-keto reductase 1C3 inhibition has been proposed for treatment of endometriosis and polycystic ovary syndrome. Clinical biomarkers of target engagement, which can greatly facilitate drug development, have not yet been described for AKR1C3 inhibitors. Here, we analyzed pharmacodynamic data from a phase 1 study with a new selective AKR1C3 inhibitor, BAY1128688, to identify response biomarkers and assess effects on ovarian function.

Design

In a multiple-ascending-dose placebo-controlled study, 33 postmenopausal women received BAY1128688 (3, 30, or 90 mg once daily or 60 mg twice daily) or placebo for 14 days. Eighteen premenopausal women received 60 mg BAY1128688 once or twice daily for 28 days.

Methods

We measured 17 serum steroids by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry, alongside analysis of pharmacokinetics, menstrual cyclicity, and safety parameters.

Results

In both study populations, we observed substantial, dose-dependent increases in circulating concentrations of the inactive androgen metabolite androsterone and minor increases in circulating etiocholanolone and dihydrotestosterone concentrations. In premenopausal women, androsterone concentrations increased 2.95-fold on average (95% confidence interval: 0.35-3.55) during once- or twice-daily treatment. Note, no concomitant changes in serum 17β-estradiol and progesterone were observed, and menstrual cyclicity and ovarian function were not altered by the treatment.

Conclusions

Serum androsterone was identified as a robust response biomarker for AKR1C3 inhibitor treatment in women. Aldo-keto reductase 1C3 inhibitor administration for 4 weeks did not affect ovarian function.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02434640; EudraCT Number: 2014-005298-36

Keywords: endometriosis, polycystic ovary syndrome, ovulation, menstrual cycle, ovary, steroid metabolism, androgens, androsterone, randomized clinical trial

Significance.

This manuscript is the first to describe effects of AKR1C3 inhibition on steroidogenesis in healthy premenopausal and postmenopausal women. We identified circulating concentrations of the androgen metabolite androsterone as a key pharmacodynamic biomarker for AKR1C3 inhibition. This novel finding is expected to help clinical development of drugs targeting AKR1C3, which have been proposed to be of potential benefit to women with endometriosis or polycystic ovary syndrome. In addition, we show for the first time that AKR1C3 inhibition does not disrupt ovarian function in healthy premenopausal women as documented by unchanged circulating estrogens and progesterone and normal menstrual cycle dynamics, which we assessed by an innovative combined sparse-dense sampling approach around the luteinizing hormone peak.

Introduction

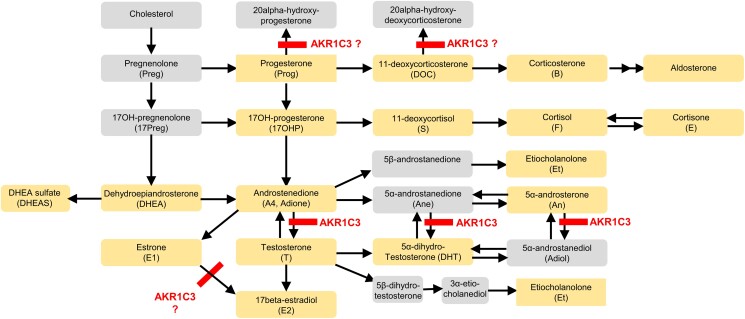

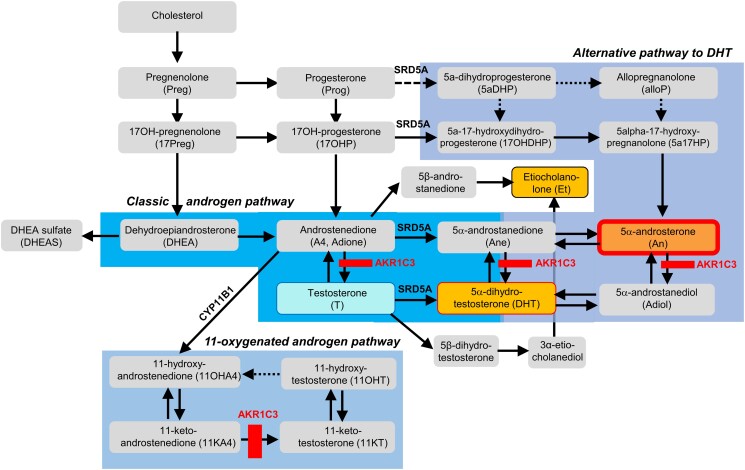

The enzyme aldo-keto reductase 1C3 (AKR1C3) or 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 5 is of critical importance for androgen activation in humans (Figure 1). A key role for AKR1C3 has been postulated in the production of androgens in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer1 and in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).2,3 In addition to androgen activation, AKR1C3 has also been implicated in progesterone metabolism and estrogen biosynthesis; and it plays a role in prostaglandin synthesis,3,4 suggesting it as a possible drug target in endometriosis,5‐8 a condition characterized by altered endometrial steroidogenesis and inflammation.

Figure 1.

Steroid metabolism pathways: Expected effects of treatment with an AKR1C3 inhibitor. (1) Progesterone is a substrate of AKR1C3 (and other enzymes); AKR1C3 (and AKR1C1) reduces progesterone to 20α-hydroxyprogesterone.31,32 Increased progesterone concentrations are expected upon treatment with an AKR1C3 inhibitor. (2) Androstenedione is a substrate of AKR1C3. Conversion to testosterone is expected to be reduced during treatment with an AKR1C3 inhibitor.31,33 (3) Estrone (E1) is a substrate of AKR1C3 (and other enzymes). A reduction in E2 concentrations and an increase in E1 concentrations are expected upon treatment with an AKR1C3 inhibitor.31 (4) 11-Deoxycorticosterone is inactivated by AKR1C3.34 This effect—which is outside the focus of this paper—is mentioned only for completeness. Orange boxes: analytes included in the AbsoluteIDQ Stero17 kit. Gray boxes: other metabolites in the pathway.

Endometriosis and PCOS each affect up to 10-15% of women of reproductive age. Treatment options, however, are currently limited. Thus, developing AKR1C3 inhibitors as therapies for these conditions would address urgent clinical needs. The development of such therapies would be greatly facilitated if response biomarkers indicative of effective in vivo AKR1C3 inhibition could be identified. One approach to detect target engagement biomarkers is the systematic investigation of the effects of AKR1C3 inhibition on steroid metabolism. A previous study in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer employing the AKR1C3 inhibitor ASP95219 provided only limited information regarding response biomarkers. In vivo effects of AKR1C3 inhibitors in women have not been reported yet, to our knowledge.

Here, we report results of a phase 1 study with the novel selective AKR1C3 inhibitor BAY1128688 in healthy premenopausal and postmenopausal women. BAY1128688, which is the result of a rational drug design approach starting from natural ligand, strongly inhibits human AKR1C3 activity (IC50: 1.4 nM; measured by quantification of coumberol formation from coumberone at a coumberone concentration of 0.3 µmol/L [Km];10,11 details in Section S1.1) but shows no inhibition of AKR1C1, AKR1C2, and AKR1C4 at concentrations up to 10 µM.7 The development of BAY1128688 was terminated due to hepatotoxicity observed in a phase 2 study of BAY1128688.12 The hepatotoxicity is assumed to be due to off-target effects of the drug.13 Therefore, it is not precluding AKR1C3 as a target for the treatment of endometriosis as Rizner and Penning point out in the above-referenced review.8

In the phase 1 study presented here, we carried out a detailed analysis of steroid biosynthesis and metabolism employing multisteroid profiling by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), alongside a detailed assessment of menstrual cycle parameters in the participating healthy premenopausal women.

Participants and methods

The study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol for this study was approved by the relevant independent ethics committees (lead ethics committee: Landesamt für Gesundheit und Soziales, Ethik-Kommission des Landes Berlin, Germany) and competent authority (Bundesinstitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte [BfArM], Germany) before the start of the study. The clinical parts of the study were conducted at three clinical research facilities in Germany in 2015 and completed in 2016. All participants gave their written informed consent before entry into the study. The study was registered with clinicalTrials.gov (NCT02434640) and EudraCT (2014-005298-36).

Study population

This was a study in healthy premenopausal and postmenopausal women. To be eligible, a woman had to be healthy and have a body mass index of ≥18 and ≤30 kg/m2. Participating women had to fulfill the published inclusion/exclusion criteria (NCT02434640). Key criteria are described below.

Postmenopausal women had to be between 45 and 68 years of age (inclusive) and to be nonsmokers for ≥3 months. Their postmenopausal status had to be confirmed by medical history (natural menopause ≥12 months before the first administration of study medication, surgical menopause by bilateral oophorectomy >3 months before the first administration of study medication, or hysterectomy) and by serum follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) level (>40 U/L).

Premenopausal women had to be between 18 and 48 years of age (inclusive), be sterilized by tubal ligation, have completed at least three menstrual cycles since delivery, abortion, or lactation, if applicable, be nonsmokers or light smokers (<10 cigarettes/day), and to have their pretreatment cycle assessed as ovulatory based on serum hormone levels (progesterone >5 nmol/L [1.57 µg/L]; 17β-estradiol [E2] >100 pmol/L [27.2 pg/mL]) and urinary estrone-3-glucuronide (E3G) signal on the ClearBlue Fertility Monitor (SPD Swiss Precision Diagnostics GmbH, Geneva, Switzerland).

Study design, treatments, and procedures

This was a two-part ascending-dose safety and pharmacokinetic (PK)/pharmacodynamic (PD) study.

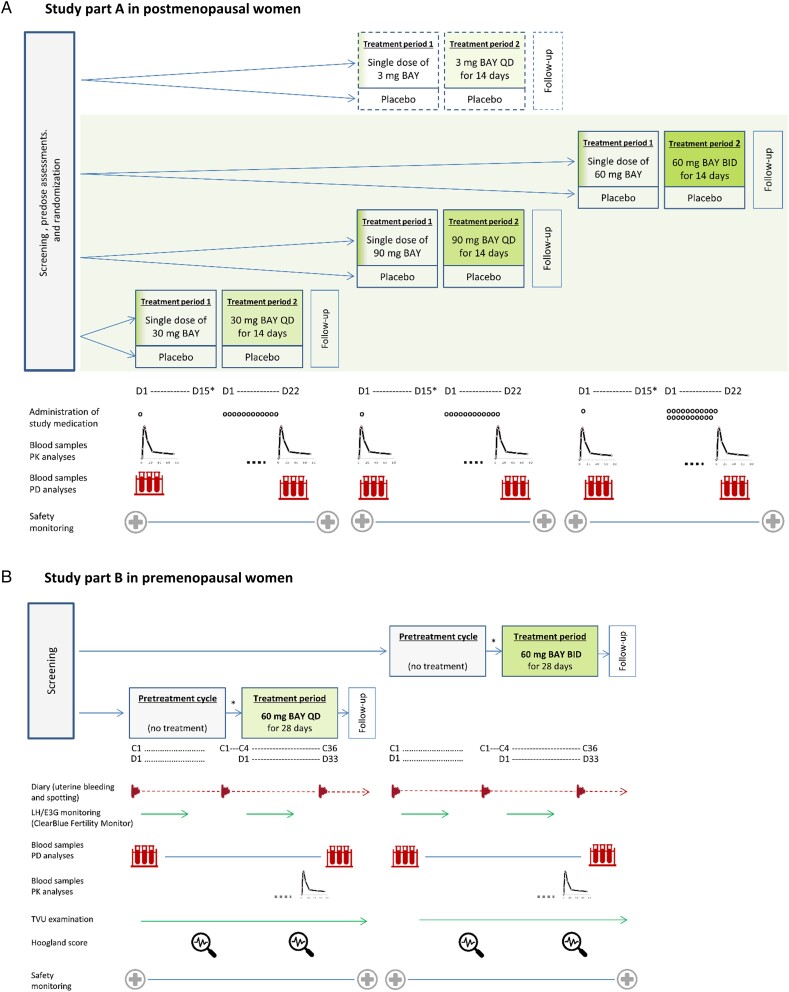

Part A of this early clinical phase 1 study, which focused on safety endpoints, was conducted in postmenopausal women as a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, combined ascending single-/multiple-dose study with three dose levels of BAY1128688 (30 mg once daily [QD], 90 mg QD, and 60 mg twice daily [BID] over 14 days) (Figure 2A). In addition, independent of the dose-escalation protocol, a new tablet formulation of BAY1128688 (3 mg QD) was studied to characterize its PK properties. Nine participants per dose step (seven on active drug and two on placebo) were included.

Figure 2.

Study design and procedures. (A) Blood samples for PK analyses of BAY1128688 and its metabolite BAY1107202 (M-7) in plasma were collected predose and 0.25, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24, 48, 72, 96, 120, 144, 192, 264, and 336 h of postdose in period 1 and—using the same sampling schedule until 192 h of postdose—on day 14 and following in period 2. Blood samples for PD analyses (steroid assay, eicosanoid assay, additional hormones, and prostaglandin metabolites within pathway) were taken at 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, and 48 h after dosing on day 1 period 1 and on day 14 in period 2 and—following the same sampling schedule, also on day −1 before Period 1. Additionally, predose samples for PK and PD analyses were taken at predefined intervals in period 2. Safety monitoring included evaluation of AE reports, measurement of vital signs, electrocardiograms, and clinical laboratory tests. Independent of the three-step dose-escalation procedure (30 mg QD, 90 mg QD, and 60 mg BID), the PK of 3 mg BAY1128688 given in the form of three new 1 mg tablets was studied using the same protocol. (B) The pretreatment cycle started with the onset of menstrual bleeding and ended with the onset of the next menstrual bleeding. The treatment period started on day 4 after the onset of menstrual bleeding (cycle day 4). The duration of treatment was 28 days, irrespective of subsequent menstrual bleedings. Pretreatment cycle and treatment period could be separated by up to 2 menstrual cycles. Samples for PD analyses (steroid assay, eicosanoid assay, additional hormones, and prostaglandin metabolites within pathway, FSH, and LH) were taken at 3- to 4-day intervals on scheduled visits, on visits introduced through urinary E3G increases (high-fertility days), on the first days of menstrual bleeding before starting treatment and at the end of treatment. Samples for PK analyses of BAY1128688 and its metabolite BAY1107202 (M-7) in plasma were collected on any day between D15 and D28 of the treatment period, following the same sampling schedule as in part A of the study. BAY, BAY1128688; BID, twice daily; C…, day … of menstrual cycle; D…, d… day within cycle or period; E3G, estrone-3-glucuronide; LH, luteinizing hormone; PD, pharmacodynamic; PK, pharmacokinetic; QD, once daily; TVU, transvaginal ultrasound. *The washout between single-dose administration in period 1 and the first dose in period 2 was 14-28 days.

Part B, which focused on PD endpoints, was conducted in premenopausal women as an open-label, intraindividual-comparison multiple-dose study with two dose levels (60 mg BAY1128688 QD and 60 mg BAY1128688 BID over 28 days) and no placebo control (Figure 2B). In both study parts, progression to the next higher dose level followed evaluation of safety and tolerability data collected at the previous level. Dosing in part B started after evaluation of the relevant safety and PK data collected in part A.

Both part A and part B comprised four study periods each. In both parts, blood samples for PK, PD, and safety analyses were taken as specified in Figure 2A and B.

In part A, the screening and randomization period was followed by treatment period 1 with single-dose administration of the study medication, treatment period 2 with multiple-dose administration over 14 days, and finally follow-up.

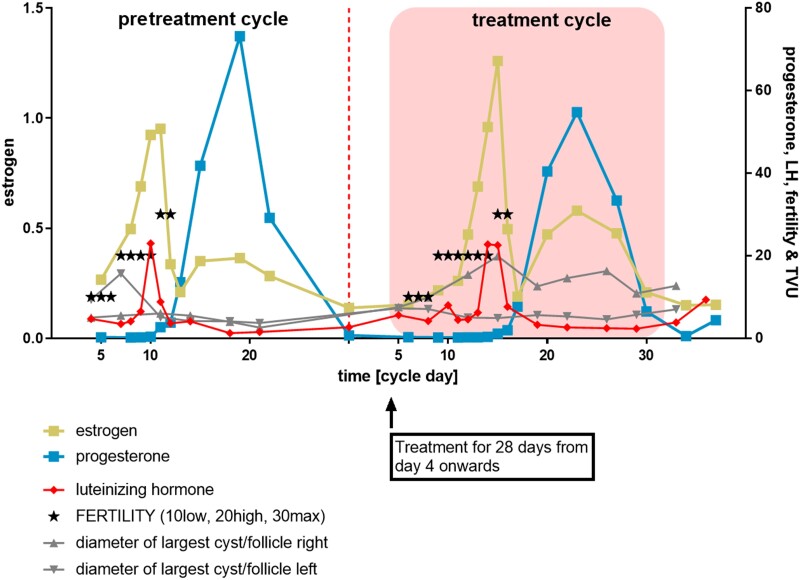

In part B, the screening period was followed by a pretreatment cycle, a 28-day treatment period, and follow-up. In the pretreatment cycle, hormonal changes over one menstrual cycle were evaluated, and evidence of ovulation was obtained. Treatment with BAY1128688 started on the fourth day of menstrual bleeding in the first or second menstrual cycle (after pretreatment) and was continued for 28 days in total. During both the pretreatment and the on-treatment menstrual cycle, ovarian activity was monitored by regular transvaginal ultrasound examinations and hormone measurements (Figure 2B). To detect the luteinizing hormone (LH) peak, the participants tested their urine LH levels every day using the abovementioned ClearBlue Fertility Monitor. Around the time of the LH peak, blood samples for hormone measurement were taken daily, otherwise only on every second or third day (combined sparse-dense sampling approach). The participants were also asked to document drug intake and any uterine bleedings and spotting in a diary, starting with the pretreatment cycle and ending with the follow-up visit.

Pharmacodynamic evaluations

Multiplex LC-MS/MS by means of a commercially available, validated assay (AbsoluteIDQ Stero17 Kit, Biocrates Life Sciences AG, Innsbruck, Austria)14 was used to simultaneously quantify 17 steroids in serum, including analytes previously described as substrates or products of AKR1C3 (Figure 1). In addition, various eicosanoids (including prostaglandins) and polyunsaturated fatty acids were simultaneously determined in plasma using the LC-MS/MS-based assay described by Unterwurzacher et al.15

Assessments of ovarian function (part B) included transvaginal ultrasound examinations, measurements of follicle diameter and endometrial thickness, classification of ovarian activity using Hoogland scores,16 and evaluation of the bleeding pattern based on participants’ daily self-assessments of the maximum bleeding intensity.

Pharmacokinetic evaluations

The concentrations of BAY1128688 and its less active main metabolite BAY1107202 (M-7) in plasma were determined using a validated LC-MS/MS method (details in Section 1.2.1; performance parameters in Table S1). Based on concentration-time data, standard noncompartmental PK parameters were calculated for both analytes (details in Section 1.2.2). In addition, a population pharmacokinetic (popPK) model and a population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (popPK/PD) model were developed for BAY1128688 and the time course of bilirubin in serum, respectively (details in Section S1.2.3).

Safety assessments

General safety assessments: Safety was assessed in all study participants based on adverse event (AE) reporting, vital signs, electrocardiograms, standard clinical laboratory tests (hematology, serum chemistry including liver function tests, and urinalysis). The primary safety endpoint was the number and severity of treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs).

Exploratory biomarkers for renal safety: See Section S1.3.

Statistical analysis

For data analysis, the software package SAS v9.2 and v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and R v3.1.2 (R Core Team 2013) were used. Graphs were prepared using Prism v8.02.2 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

All participants who received at least one dose of the study medication were included in the safety analyses; all participants who completed the study without protocol violations affecting the validity of PD analysis (or PK analysis) were included in the PD analyses (or PK analyses if they received BAY1128688). All participants treated with placebo were pooled.

All data were analyzed by descriptive statistical methods. Pharmacodynamic values below the lower limit of quantitation were excluded from analysis.

For steroid data from part A, ratios between postdose measurements and baseline—defined as the last measurement before drug administration in the respective period—were calculated to determine fold increases or decreases.

The steroid data obtained in part B, ie, in premenopausal women, were summarized with LH-peak-adjusted areas under the concentration-time curves (AUC). The steroid AUCs were calculated for the intervals from day 5 before the LH peak to day 10 after the peak of each cycle, the interval during which the data density was highest. In case no values were available for these time points/visits, the interval limits were replaced by the median of all earlier or later visits, respectively.

Differences in steroid levels between cycles (pretreatment vs. treatment, part B) were assessed using a linear mixed effect model where the subject was included as random factor to accommodate for differences in the average steroid levels of each woman. The model equation reads:

where Ycs is the AUC for the steroid of subject s in cycle c (pretreatment and treatment), S is the random subject effect, and C is the fixed cycle effect. β0 and β1 are intercept and coefficient for modeling the impact of the cycle. ε is the residual error of the measurement. The random subject effects Ss are modeled by a normal distribution.

All statistical analyses were exploratory.

Results

Participants and procedures

In total, 100 healthy postmenopausal women and 52 healthy premenopausal women were screened for this study. We randomized 51 women (33 postmenopausal and 18 premenopausal), and all received study medication, completed the study as planned, and were included in the safety and biomarker/PD analyses; all participants who received active drug were included in the PK analyses (subject disposition in Figure S1) (supplementary tables and figures are provided in Section S2.1 and S2.2, respectively). All participants were White. Their characteristics were well balanced with no notable differences between dose groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic data and smoking history.

| Dose groupa | Age (years) | BMI (kg/m2) | Smoking history | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Arith. mean | Range | Arith. mean | SD | Never/former/current | ||

| Part A (postmenopausal women) | 3 mg QD | 5 | 57.0 | 52-64 | 23.3 | 4.42 | 4/1/- |

| 30 mg QD | 7 | 56.6 | 52-60 | 24.6 | 1.91 | 4/3/- | |

| 60 mg BID | 7 | 61.7 | 52-68 | 24.2 | 1.69 | 4/3/- | |

| 90 mg QD | 7 | 62.3 | 57-67 | 24.1 | 2.43 | 5/2/- | |

| Placebo | 7 | 62.3 | 59-67 | 25.9 | 2.11 | 4/3/- | |

| Total | 33 | 60.2 | 52-68 | 24.5 | 2.52 | 21/12/- | |

| Part B (premenopausal women) | 60 mg QD | 9 | 40.4 | 32-48 | 24.6 | 2.61 | 4/1/4 |

| 60 mg BID | 9 | 38.4 | 32-46 | 23.4 | 3.02 | 1/4/4 | |

| Total | 18 | 39.4 | 32-48 | 24.0 | 2.81 | 5/5/8 | |

Abbreviations: BID, twice daily; BMI, body mass index; N, number of participants; QD, once daily; SD, standard deviation.

mg specifications refer to the doses of BAY1128688 administered (single doses).

Pharmacodynamics

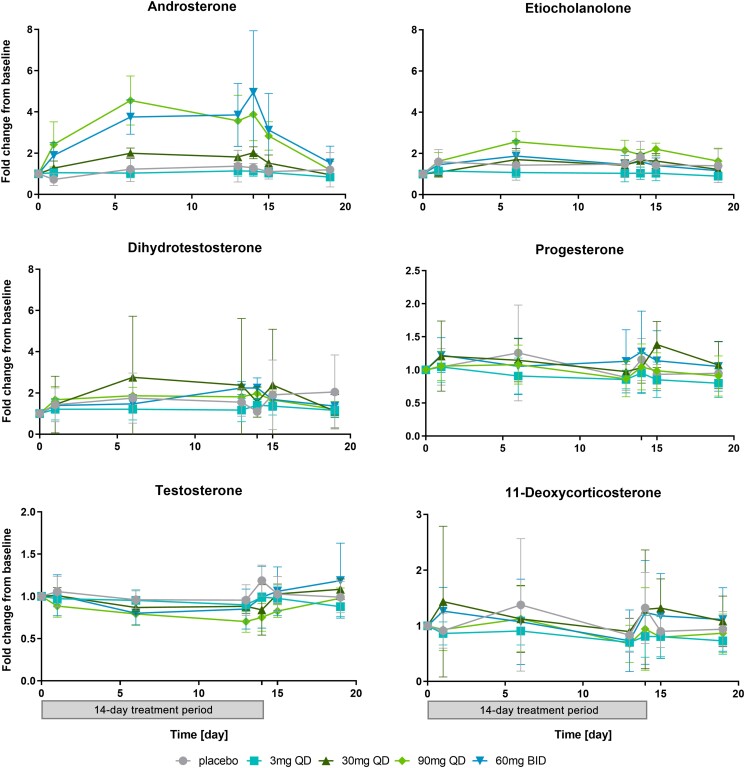

In our study, serum concentrations of the inactive androgen metabolite androsterone increased in a dose-dependent manner in postmenopausal women receiving the novel AKR1C3 inhibitor BAY1128688 at dosages between 30 mg QD and 60 mg BID for 14 days, and they were also substantially increased in premenopausal women receiving 60 mg BAY1128688 QD or BID for 28 days. No or less pronounced increases in serum androsterone were observed after single-dose administration. We also observed slight increases in the inactive androgen metabolite etiocholanolone and the active androgen 5α-dihydrotestosterone (DHT), both of which were much less pronounced than the increase in androsterone (Figure 3 and Table S2).

Figure 3.

Steroid assays: Change-from-baseline versus time curves for selected analytes (means and standard deviations) (postmenopausal women, 14-day treatment period, and 5-day follow-up). The treatment history (14 days on treatment and 5-day follow-up without treatment) is depicted below the x-axes at the bottom of the picture. Changes from baseline were calculated as the ratio between the value at time X and the last value before administration of the first dose of BAY1128688 in period 2. The x-axis shows the time after the first dose in period 2 in days. For clarity, only the predose value is presented for days on which multiple samples were taken. NB: The analysis of intraday profiles did not reveal any circadian effects on steroid levels. For number of valid values per time point, see Table S2. The change-from-baseline versus time curves for estradiol and estrone are not presented here because these data sets contained too many invalid values and values below the detection limit. BID, twice daily; QD, once daily.

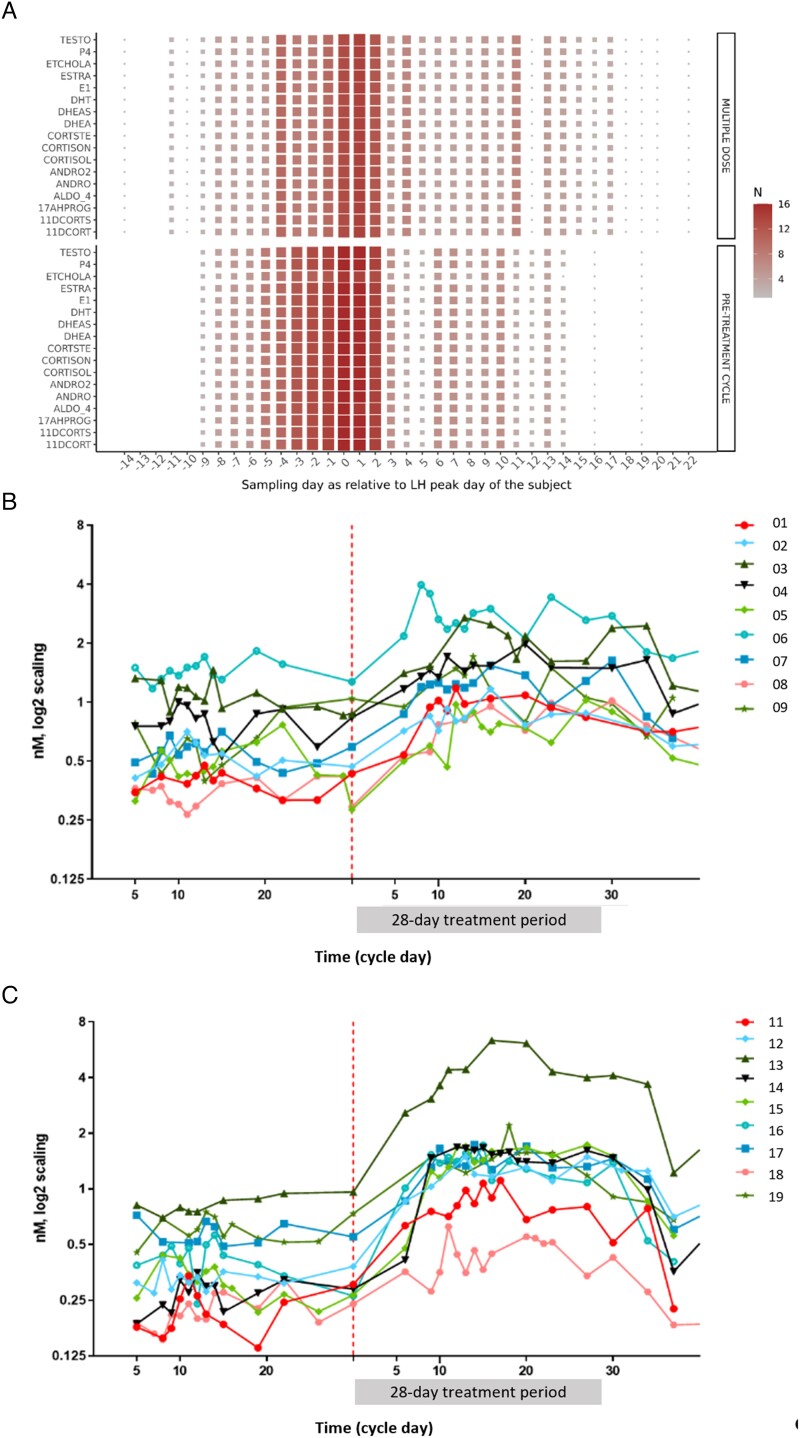

In premenopausal women, the switch from sparse blood sampling during early follicular phase to dense sampling around the LH peak was successful as illustrated in Figure 4A. The combined sparse-dense, LH-peak-centered blood sampling scheme, where the participants monitored their urine LH levels using an at-home test, was applied to minimize the burden caused by repeated blood draws. The LH-peak-adjusted AUCs (day −5 to day +10 relative to LH peak) for serum androsterone markedly increased during the treatment cycle compared to the pretreatment cycle (Table 2; point estimate for mean fold change from baseline [90% confidence interval {CI}]: 2.95 [0.35-3.55]; P = .019). Treatment-related increases in serum androsterone concentrations were seen in each individual participant; however, the degree of the increase varied considerably between participants (Figure 4B and C).

Figure 4.

Blood sampling schedule for steroid and hormone measurements in premenopausal women (A) and individual androsterone serum concentrations before and during treatment with BAY1128688 60 mg QD (B) or BID (C). (A) The heat map shows for each steroid the quantity of observations (N) available per sampling time point relative to the LH peak. The quantity of observations is coded on a scale ranging from very few observations (small gray squares) to large number of observations (large dark red squares). The interval where the availability of observations was greatest in both cycles (day −5 to day +10 relative to the LH peak) was considered for AUC calculations. (B and C) For clarity, a log2 y-axis was used. The red dotted line indicates the first measurement in the treatment period. The numbers 1-19 represent individual study participants. 11DECORT, 11-deoxycorticosterone; 11DECORTS, 11-deoxycortisol; 17AHPROG, 17α-hydroxyprogesterone; ALDO 4, aldosterone; ANDRO2, androstenedione; ANDRO, androsterone; CORTSTE, corticosterone; CORTISOL, cortisol; CORTISON, cortisone; DHEAS, dehydroepiandrosterone; DHEA, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate; DHT, dihydrotestosterone; ESTRA, estradiol; E1, estrone; ETCHOLA, etiocholanolone; P4, progesterone; TESTO, testosterone.

Table 2.

Steroid assay: Changes from baseline in LH-peak-adjusted AUCs (premenopausal women receiving 60 mg BAY1128688 once or twice daily over 28 days).

| Analyte | Pretreatment cycle AUC (nmol/d) |

Treatment period AUC (nmol/d) |

Mixed linear model | X-fold change from baseline | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC difference (nmol/d) |

SE | Adj P value | Median | Mean | CI | N | |||

| 11-Deoxycorticosterone | 1.89 | 1.61 | −0.308 | 0.118 | .365 | 0.87 | 0.88 | (0.78-0.98) | 14 |

| 11-Deoxycortisol | 5.96 | 4.84 | −0.953 | 0.672 | 1 | 0.79 | 0.85 | (0.70-1.00) | 14 |

| 17alpha-Hydroxyprogesterone | 47.5 | 42.5 | −5.20 | 1.90 | .285 | 0.87 | 0.88 | (0.79-0.96) | 14 |

| Aldosterone | 3.16 | 3.17 | 0.0041 | 0.279 | 1 | 0.94 | 1.05 | (0.87-1.22) | 14 |

| Androstenedione | 51.5 | 51.1 | −0.312 | 2.49 | 1 | 0.98 | 0.99 | (0.91-1.07) | 14 |

| Androsterone | 7.03 | 20.6 | 13.5 | 3.24 | .019 | 2.42 | 2.95 | (0.35-3.55) | 14 |

| Corticosterone | 106 | 90.6 | −17.7 | 16.7 | 1 | 0.95 | 0.98 | (0.78-1.19) | 14 |

| Cortisol | 4577 | 4102 | −407 | 397 | 1 | 0.92 | 0.95 | (0.85-1.04) | 14 |

| Cortisone | 914 | 859 | −55.6 | 33.4 | 1 | 0.92 | 0.94 | (0.88-1.01) | 14 |

| Dehydroepiandrosterone | 153 | 130 | −23.3 | 7.83 | .182 | 0.78 | 0.83 | (0.75-0.91) | 14 |

| Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate | 60 526 | 69 510 | 9524 | 4386 | .833 | 1.12 | 1.11 | (1.01-1.21) | 14 |

| Dihydrotestosterone | 6.69 | 10.2 | 3.49 | 0.438 | <.001 | 1.53 | 1.52 | (1.41-1.63) | 14 |

| Estradiol | 6.79 | 7.29 | 0.343 | 0.444 | 1 | 1.12 | 1.06 | (0.94-1.18) | 14 |

| Estrone | 3.84 | 4.02 | 0.139 | 0.226 | 1 | 1.08 | 1.05 | (0.94-1.15) | 14 |

| Etiocholanolone | 3.52 | 7.01 | 3.47 | 0.891 | .036 | 1.70 | 1.96 | (1.66-2.27) | 13 |

| Progesterone | 258 | 213 | −50.6 | 19.9 | .416 | 0.90 | 0.84 | (0.70-0.98) | 14 |

| Testosterone | 10.9 | 9.45 | −1.43 | 0.484 | .191 | 0.87 | 0.86 | (0.78-0.94) | 14 |

Data are sorted alphabetically; P values are Bonferroni–Holm adjusted.

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the concentration-time curve (day −5 to day +10 relative to the LH peak determined by the investigator); CI, 90% confidence interval; LH, luteinizing hormone; N, number of participants; SE, standard error.

There were also minor increases (fold change < 2) within the reference range in circulating etiocholanolone and DHT concentrations (Table 2). Serum testosterone appeared to slightly decrease in the treatment cycle compared with the pretreatment cycle.

Of note, there were no systematic changes in serum E2 and progesterone concentrations upon treatment with BAY1128688 as illustrated in Figure S2. In keeping with this, menstrual cyclicity and ovarian function in the premenopausal participants were not altered by the treatment, as illustrated in Figure 5. All participants had an ovulatory pretreatment cycle. During the treatment cycle (28 days of BAY1128688), most participants (14 of 18 participants) had a Hoogland score of 6, indicative of normal ovulation (Figure S3). Among the remaining four participants, two participants did not ovulate in the treatment cycle and two participants could not attend the transvaginal ultrasound examination; however, their on-treatment hormonal profiles were indicative of ovulation.

Figure 5.

Exemplary individual hormone concentration (nm) and follicle size versus time curves. The above patterns of hormonal and follicle size changes indicate presence of an ovulation in an exemplary participant before treatment and on treatment with BAY1128688 60 mg BID. The asterisks refer to the ClearBlue fertility signals. Follicle diameters were determined during transvaginal ultrasound (TVU) examinations. Note: Confirmation of ovulation in the pretreatment cycle was a prerequisite for enrollment in the treatment phase.

Systemic measurements of eicosanoids (including prostaglandins) and polyunsaturated fatty acids showed broad variability within and between participants (data not shown). There was no obvious impact of AKR1C3 inhibition on any of the prostaglandins investigated.

Pharmacokinetics

An overview of the PK parameters of BAY1128688 and its main metabolite M-7 determined in plasma after single-dose and multiple-dose administration of BAY1128688 is given in Table S3.

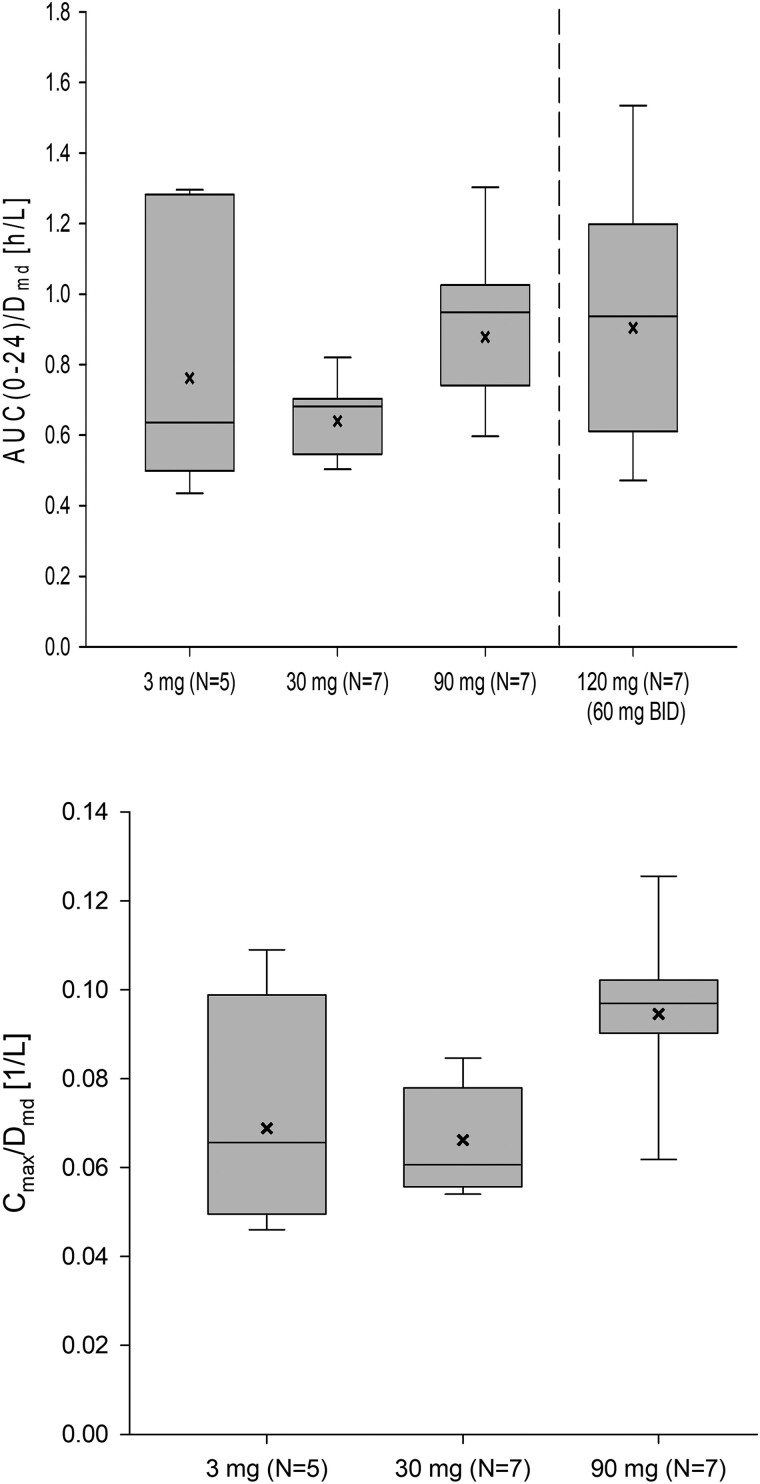

Following multiple-dose administration to postmenopausal women, the exposure of BAY1128688 (AUC[0-24]multiple-dose) increased roughly dose proportionally, whereas Cmax seemed to increase slightly supra-proportionally within the tested dose range (Figure 6). With repeated QD administration, minor to moderate accumulation of BAY1128688 was observed (accumulation indices [RAAUC] between 1.23 and 1.61). With repeated BID administration, accumulation was slightly more pronounced (RAAUC = 2.32). Linearity indices (RLIN) around 1 (0.94-1.28) indicate that the steady-state PK is predictable from single-dose data. The time courses of the mean Ctrough concentrations indicate that PK steady-state conditions were reached after about 4-8 days of treatment in all dose groups (data on file at Bayer AG). The metabolic ratio (M-7 to parent compound) was low at steady state in all dose groups (0.115-0.136).

Figure 6.

Dose-normalized exposure of BAY1128688 in plasma at steady state (postmenopausal women; period 2, day 14). Box: 25th to 75th percentile; horizontal line: median; whiskers: 10th to 90th percentile; x: geometric mean. Note: Cmax/D for 60 mg BID administration is not presented because—unlike AUC—Cmax is affected by the dosing interval. AUC(0-24), area under the plasma concentration vs time curve from time 0 to 24 h postdose; BID, twice per day; Cmax, maximum observed concentration in plasma (within the dosing interval); D, dose; md, multiple dose.

Largely similar multiple-dose PK parameters were obtained in premenopausal women.

Safety results

In total, 41 of 51 participants (80%) were affected by TEAEs. All TEAEs were of mild or moderate intensity and nonserious; and none of the AEs led to premature discontinuation of treatment with the study drug. The most common TEAEs in participants receiving BAY1128688 were (with decreasing total frequency) headache, nausea, increased serum bilirubin, vomiting, nasopharyngitis, and decreased appetite (Table S4). In the majority of instances, these TEAEs were classified as study drug related (with the exception of nasopharyngitis). Headache, increased serum bilirubin, and decreased appetite were reported only for participants receiving BAY1128688. A detailed overview of all TEAEs is given in Table S5.

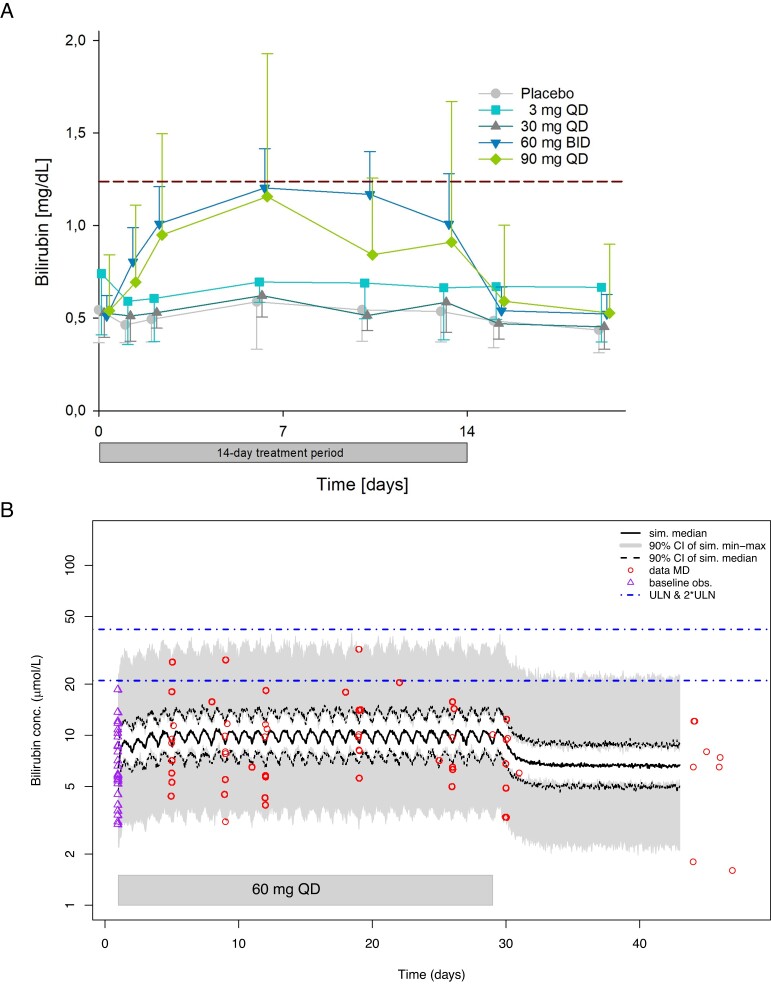

Dose-dependent reversible increases from baseline in total serum bilirubin concentrations were mostly observed not only in postmenopausal participants (Figure 7A) but also in one premenopausal participant who received 60 mg BAY1128688 once daily (Table S5). However, at the highest dose of 60 mg BID increases in serum bilirubin were noted as AEs in five of seven (71%) postmenopausal women versus none of the premenopausal participants receiving the same dosage. Increases in mean and median total serum bilirubin were observed in postmenopausal women during 2 weeks of treatment at doses of 90 mg QD and 60 mg BID but not at 30 and 3 mg QD, with maximum median increases of 2.2-fold median baseline values with 90 mg QD over baseline at day 6 of treatment (individual maximum increase around 2.3-fold upper limit of normal [ULN] at day 6) and with maximum median increases of 2.8-fold median baseline values with 60 mg BID over baseline at day 6 of treatment (individual maximum increase around 1.2-fold ULN at day 13). The increases in serum bilirubin were modest in all participants, ie, below 1.50-fold above the ULN. Only in two participants, one postmenopausal woman (90 mg QD), whom the investigator knew to have a predisposition for elevated bilirubin levels, and one premenopausal woman (60 mg QD), a more pronounced increase was observed (up to 2.31-fold and 1.53-fold, respectively, above the ULN). Of note, no concomitant changes in liver enzymes (transaminases; alkaline phosphatase) were detected in any of the participants. Exploratory biomarkers did not show any early signs of kidney damage (Section S2.4).

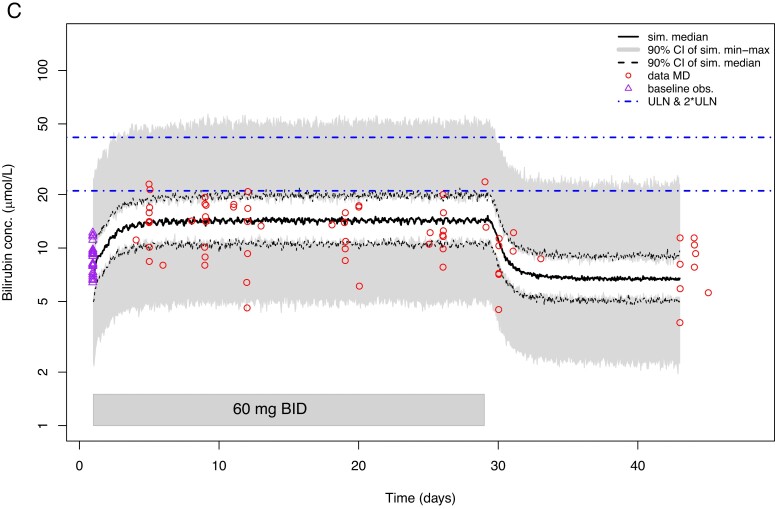

Figure 7.

Observed concentration-time curves (mg/dL) (A) and model-predicted concentration-time curves (µmol/L) (B and C) for total bilirubin in serum. (A) Mean bilirubin serum concentration-time curves observed in postmenopausal women during and after 14-day treatment with BAY1128688. The dashed horizontal line in indicates the ULN (1.23 mg/dL). Whiskers indicate standard deviations. The 3 mg group included five participants, the other groups seven participants each. (B) Model-predicted bilirubin serum concentration-time curves for premenopausal women taking 60 mg BAY1128688 QD. (Figure C see further below) Model-predicted bilirubin serum concentration-time curves for premenopausal women taking 60 mg BAY1128688 BID. BID, twice daily; CI, confidence interval; conc., concentration; MD, multiple dose; obs., observations; QD, once daily; sim., simulated; ULN, upper limit of normal.

Population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling of bilirubin

A popPK/PD model based on the popPK model for BAY1128688 described in Section S2.3 was inferred to describe serum bilirubin concentrations from part A. For this purpose, a turnover model was used in which the bilirubin concentration () was modeled under the influence of the plasma concentration of BAY1128688 () via an Emax submodel:

In this model, kin and kout refer to the bilirubin first-order rate constants for liver to plasma influx and elimination from plasma, respectively, and EC50 refers to half of BAY1128688 plasma concentration at which the maximum bilirubin serum concentration is observed.

A dose-stratified visual predictive check for participants from part A confirmed the quality of the developed popPK/PD model. In a second step, it was evaluated whether popPK/PD model from part A was capable of predicting the bilirubin data observed in premenopausal, tubal-ligated women part B. It was found that the random effect parameters of the model needed to be reestimated to improve individual fits and account for the larger variability in bilirubin concentrations observed in these women. Fixed effect parameters were not altered.

The two popPK/PD models were subsequently used for in silico clinical trial simulations to evaluate whether serum bilirubin concentrations would exceed the 2-fold of the ULN in postmenopausal or premenopausal, tubal-ligated women when given 60 mg of BAY1128688 QD or BID. The simulations revealed that 60 mg BID dosing in postmenopausal women would lead to bilirubin concentrations in which the 90% CI of the median would not exceed the 1.5·ULN. In premenopausal women, 60 mg QD dosing would lead to scenario in which the 90% CI of the maximum simulated concentration would stay below 2·ULN and the 90% CI of the simulated median would remain below the ULN (Figure 7B). A 60 mg BID dosing regimen in these women would lead to a scenario in which the 90% CI of the maximum simulated concentration would always include both ULN and 2·ULN, whereas the 90% CI of the simulated median would remain below the ULN (Figure 7C).

These modeling results were supportive for further exploration of the investigated BAY1128688 doses and dosing regimens in future clinical trials with patients (eg, trial NCT03373422).

Discussion

This manuscript is the first to describe effects of AKR1C3 inhibition on a panel of steroids in women, which facilitated the identification of serum androsterone as a robust in vivo response biomarker in healthy premenopausal and postmenopausal women. We also show for the first time that AKR1C3 inhibition does not disrupt ovarian function in healthy premenopausal women as documented by unchanged circulating sex steroid concentrations and normal menstrual cycle dynamics, assessed by an innovative combined sparse-dense sampling approach around the LH peak.

In our study, serum androsterone concentrations increased in a dose-dependent manner in postmenopausal women receiving the novel AKR1C3 inhibitor BAY1128688 at dosages between 30 mg QD and 60 mg BID, and they were also substantially increased in premenopausal women receiving 60 mg BAY1128688 QD or BID for 28 days. A dose of 30 mg of BAY1128688 translates into exposures corresponding to in vitro IC50 coverage for enzymatic activity of human AKR1C3. No or less pronounced increases were observed after single-dose administration and multiple-dose administration of 3 mg QD.

In our study, circulating pretreatment concentrations of the inactive androgen metabolite androsterone (5α-androsterone) in participating premenopausal women were in the range previously observed in healthy premenopausal women by Ke et al.17 (Table S6). The on-treatment values (60 mg BAY1128688 QD or BID) were also mostly within that range, but in single cases, they were considerably increased above that reference range (maximum: 6.36 nmol/L). Systemic effects of increased levels of androsterone in the range observed in our study are not to be expected as androsterone is a precursor steroid, which can be activated, but exerts only little, if any, androgenic activity itself.

We also saw marked, although less robust, increases in the inactive androgen metabolite etiocholanolone (also known as 5β-androsterone) and the active androgen DHT. No marked changes were observed for the other steroids measured; testosterone appeared to slightly decrease during the treatment cycle.

The observed increases in DHT concentrations can be regarded as minor from the clinical point of view. The circulating DHT concentrations determined in the participating premenopausal women prior to and during treatment were largely within the range reported by Shiraishi et al.18 for healthy premenopausal women (follicular phase) and the range reported by Mezzullo et al.19 for healthy pre- and menopausal women (Table S6).

Figure 8 provides a visual summary of the main findings of our study regarding the impact of AKR1C3 inhibition on in vivo androgen biosynthesis and metabolism. AKR1C3 has a critical role in androgen activation, converting androstenedione to testosterone, 5α-androstanedione to DHT and also 5α-androsterone to 5α-androstanediol. Accordingly, it is expected that these three conversions will be blocked by AKR1C3 inhibition. In our study, we observed a marked increase in androsterone, likely reflecting the conversion of androstenedione to 5α-androstanedione and eventually to androsterone in the presence of AKR1C3 inhibition (Figure 8). The pronounced increase in androsterone contrasted with the comparably only minor increase in etiocholanolone, reflective of 5β-reduction of androstenedione. It is tempting to speculate that reduction in the activity of the androgen-activating enzyme AKR1C3 may prompt a counter-regulatory upregulation in the androgen-activating 5α-reductase activity conveyed by SRD5A1 and SRD5A2 genes. The same speculated change may also have contributed to the observed minor increase in DHT by slightly increasing conversion of testosterone to DHT. An upregulation of 5α-reductase type 1 activity would also increase steroid flow into the alternative pathway to DHT20 through increased conversion of progesterone and 17-hydroxy-progesterone to their 5α-reduced metabolites (Figure 8), which would result in a further increase in 5α-androsterone. However, our study is limited by the fact that the multisteroid profiling assay did not comprise intermediates of the alternative DHT pathway other than androsterone.

Figure 8.

Visual summary of main findings mapped onto steroidogenesis flowchart. Solid arrows: major conversion steps; dotted and dashed arrows: minor conversion steps. The different pathways of steroid genesis are highlighted by different shades of blue (classic pathway in dark blue; alternative/backdoor pathway in violet blue; 11-oxygenated androgen pathway in light blue). AKR1C3, aldo-keto reductase 1C3; CYP11B1, cytochrome P450 11B1; SRD5A, 5α-reductases.

Similarly, in this study, we did not measure the 11-oxygenated androgens, which have been proposed to play a major role in female androgen homeostasis21,22 and androgen excess in women with PCOS.23 The impact of AKR1C3 inhibition on the 11-oxygenated androgen pathway can be safely assumed to be much more pronounced than that on the classic androgen pathway, as Karl Storbeck's group has shown that AKR1C3 has a strong substrate preference for 11-ketoandrostenedione over androstenedione.24

Of note, we did not observe any changes in systemic estrogens and progesterone with AKR1C3 inhibitor treatment. This may indicate that the potential role of AKR1C3 in progesterone metabolism and estrogen activation is only minor when investigated in vivo.

Adding to this, we present substantial evidence that ovarian function and menstrual cyclicity were not affected by AKR1C3 inhibition. The Hoogland score,16 which was initially developed to evaluate inhibition of ovulation by hormonal contraceptives, was used to inform about the presence of ovulatory events in the ovary and confirmed ovulation for 14/18 participants in the treatment cycle (two participants not evaluable and two participants anovulatory). The hormonal fluctuations of E2, progesterone, LH, and FSH were in line with the expectations of normal ovulatory cycles25 for 16/18 participants. It cannot be excluded that the absence of an ovulation in two participants during treatment (age 44 and 46 years; ovulatory in pretreatment cycle) could be related to AKR1C3 inhibition; however, anovulatory cycles are not uncommon. Prior et al.26 report an anovulation rate of 37% for clinically normal menstrual cycles in women from 20 to 49.9 years of age.

The focus of this publication was on circulating PD biomarkers as they will be easier to evaluate in clinical studies than tissue-based biomarkers. Effects of AKR1C3 inhibition and resulting changes in local metabolic turnover of steroids (androgens, estrogen, or progesterone) in the endometrium and endometrial lesions27‐29 as well as other target tissues of interest, such as adipose tissue, remain a topic for future studies.

An additional innovative aspect of this study was that burden on the study participants was minimized without loss of information. This was achieved by (1) using a multiplex LC-MS/MS assay minimizing blood volume requirements for steroid analyses and (2) through the combined sparse/dense sampling regimen for assessment of cyclic sex hormonal changes in premenopausal women. Participants monitored themselves for the occurrence of the LH peak by means of a urine fertility monitor with dense sampling selectively implemented around the time of the LH peak only.

In this phase 1 study in healthy female participants, 2 or 4 weeks of treatment with the AKR1C3 inhibitor BAY1128688 was safe and well tolerated with no serious or severe AEs or AEs leading to termination of treatment. In particular, the observed increases in serum bilirubin were not accompanied by any increase in alanine or aspartate aminotransferase that would indicate hepatotoxicity.

The findings observed in a phase 2 study with BAY128688 in premenopausal women with endometriosis (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03373422; Eudra CT number: 2017-000244-18)12 (increases in serum bilirubin and hepatotoxicity) are described elsewhere.13 Briefly, BAY1128688 was identified in vitro as inhibitor of the organic anion transporting polypeptide (OATP) 1B1/3 transporters, which facilitate uptake of bilirubin into the hepatocyte. Inhibition of OATPs might be causal for the increases in serum bilirubin observed in the present phase 1 study after 2 or 4 weeks of treatment; ie, these increases are assumed not to be caused by AKR1C3 inhibition but to represent an off-target activity. The hepatotoxicity observed in the phase 2 study after more than 8 weeks of treatment is also believed to be an off-target effect.

The PK of the new AKR1C3 inhibitor BAY1128688 was comprehensively characterized in both premenopausal and postmenopausal women in this study. Overall, the PK of BAY1128688 appeared to be similar in premenopausal and postmenopausal women. No relevant change in the PK of BAY1128688 was observed between single- and multiple-dose administration, indicating the predictability of steady-state PK of BAY1128688 from single-dose PK data and the absence of time-dependent PKs. The developed popPK/PD model was used to explore potential BAY1128688 doses and dosing regimens and associated exposures with regard to anticipated bilirubin increases in serum. The observed data were supportive for further exploration of the investigated doses in future clinical trials in patients using both QD and BID administration.

In conclusion, we identified serum androsterone as a robust PD response biomarker for in vivo AKR1C3 inhibition in women. Such a biomarker can be expected to facilitate clinical development of AKR1C3 inhibiting drugs. We also documented that AKR1C3 inhibition did not interfere with physiological ovarian function in vivo.

Future studies should explore the androgen metabolome even more comprehensively, particularly considering the 11-oxygenated androgens, and investigate how AKR1C3 inhibition impacts on androgen homeostasis in women with androgen excess, namely, PCOS. Recent studies have shown that increased AKR1C3 expression and activity in adipose tissue drives androgen production and subsequently insulin resistance and lipotoxicity.23,30 Therefore, AKR1C3 inhibition might represent a promising treatment approach in mitigating both androgen excess and metabolic dysfunction in women with a PCOS, a prevalent condition for which no specific treatment exists to date.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participating volunteers for their participation and continued commitment to the study. Further, we would like to thank our Bayer colleague Kerstin Gude for her critical review of safety results shared in this manuscript. Dr. Matthias Berse was the coordinating investigator of this study (Leiter der klinischen Prüfung according to German Drug Law). Marion Schumann—employed by Allied Clinical Management GmbH, Berlin, at that time—was responsible for the operational conduct of this study. Safety, hormones, and proteins laboratory determinations were performed by a central laboratory, SYNLAB GmbH, Berlin, Germany. Steroids were analyzed at Biocrates, Innsbruck, Austria. Medical writing support was provided by C. Hilka Wauschkuhn, Bonn, Germany, on behalf of Bayer AG. The clinical parts of this Bayer-sponsored study were conducted at the three clinical research organizations: CRS Clinical Research Services Berlin GmbH, Parexel International GmbH (Berlin, Germany), and Nuvisan GmbH (Neu-Ulm, Germany).

Contributor Information

Isabella Gashaw, Research and Development, Pharmaceuticals, Bayer AG, 13353 Berlin, Germany.

Stefanie Reif, Research and Development, Pharmaceuticals, Bayer AG, 13353 Berlin, Germany.

Herbert Wiesinger, Research and Development, Pharmaceuticals, Bayer AG, 13353 Berlin, Germany.

Andreas Kaiser, Research and Development, Pharmaceuticals, Bayer AG, 13353 Berlin, Germany.

Frank S Zollmann, Pharma Consult, 12161 Berlin, Germany.

Christian Scheerans, Research and Development, Pharmaceuticals, Bayer AG, 13353 Berlin, Germany.

Joachim Grevel, Clinical Development, Bast GmbH, 69115 Heidelberg, Germany.

Paolo Piraino, Research and Development, Pharmaceuticals, Bayer AG, 13353 Berlin, Germany.

Henrik Seidel, Research and Development, Pharmaceuticals, Bayer AG, 13353 Berlin, Germany.

Michaele Peters, Research and Development, Pharmaceuticals, Bayer AG, 13353 Berlin, Germany.

Antje Rottmann, Research and Development, Pharmaceuticals, Bayer AG, 13353 Berlin, Germany.

Beate Rohde, Research and Development, Pharmaceuticals, Bayer AG, 13353 Berlin, Germany.

Wiebke Arlt, Medical Research Council London Institute of Medical Sciences, W12 0NN London, United Kingdom; Department of Clinical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, Imperial College London, W12 0NN London, United Kingdom.

Jan Hilpert, Research and Development, Pharmaceuticals, Bayer AG, 13353 Berlin, Germany.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Journal of Endocrinology online.

Funding

The study was sponsored and funded by Bayer AG. W.A. receives funding from the Wellcome Trust (Investigator Award WT209492/Z/17/Z) and the National Institute of Health and Care Research (NIHR) Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre (NIHR203326). The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR UK or the Department of Health and Social Care UK.

Conflicts of interest: S.R., H.W., A.K., C.S., P.P., H.S., M.P., A.R., B.R., and J.H. are employed by Bayer AG. I.G. was employed by Bayer AG at time of study design, conduct, and analysis. W.A. serves as a scientific consultant to Bayer AG. F.S.Z. is an employee of Pharma Consult, Berlin, Germany. Bayer contracted Pharma Consult, Berlin, Germany for medical monitoring services in the context of the study reported. J.G. was an employee of Bast GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany, at the time of the analyses. Bayer contracted Bast GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany for analytical and modeling services in the context of the study reported. W.A. is Editor-in-Chief of EJE. She was not involved in the review or editorial process for this paper, on which she is listed as an author.

References

- 1. Tamae D, Mostaghel E, Montgomery B, et al. The DHEA-sulfate depot following P450c17 inhibition supports the case for AKR1C3 inhibition in high risk localized and advanced castration resistant prostate cancer. Chem Biol Interact. 2015;234:332–338. 10.1016/j.cbi.2014.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. O'Reilly MW, Kempegowda P, Walsh M, et al. AKR1C3-mediated adipose androgen generation drives lipotoxicity in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(9):3327–3339. 10.1210/jc.2017-00947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Matsuura K, Shiraishi H, Hara A, et al. Identification of a principal mRNA species for human 3alpha-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase isoform (AKR1C3) that exhibits high prostaglandin D2 11-ketoreductase activity. J Biochem. 1998;124(5):940–946. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Desmond JC, Mountford JC, Drayson MT, et al. The aldo-keto reductase AKR1C3 is a novel suppressor of cell differentiation that provides a plausible target for the non-cyclooxygenase-dependent antineoplastic actions of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Cancer Res. 2003;63(2):505–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rakhila H, Carli C, Daris M, Lemyre M, Leboeuf M, Akoum A. Identification of multiple and distinct defects in prostaglandin biosynthetic pathways in eutopic and ectopic endometrium of women with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2013;100(6):1650–9.e1-2. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sinreih M, Anko M, Kene NH, Kocbek V, Rižner TL. Expression of AKR1B1, AKR1C3 and other genes of prostaglandin F2α biosynthesis and action in ovarian endometriosis tissue and in model cell lines. Chem Biol Interact. 2015;234:320–331. 10.1016/j.cbi.2014.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Peters M, Einspanier A, Bothe U, Sohler F, Fischer OM, Zollner TM. A novel AKR1C3 inhibitor demonstrates strong efficacy in a marmoset monkey: Poster SRI 2016; 2016.

- 8. Rižner TL, Penning TM. Aldo-keto reductase 1C3-assessment as a new target for the treatment of endometriosis. Pharmacol Res. 2020;152:104446. 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.104446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Loriot Y, Fizazi K, Jones RJ, et al. Safety, tolerability and anti-tumour activity of the androgen biosynthesis inhibitor ASP9521 in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: multi-centre phase I/II study. Invest New Drugs. 2014;32(5):995–1004. 10.1007/s10637-014-0101-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yee DJ, Balsanek V, Bauman DR, Penning TM, Sames D. Fluorogenic metabolic probes for direct activity readout of redox enzymes: selective measurement of human AKR1C2 in living cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(36):13304–9. 10.1073/pnas.0604672103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Halim M, Yee DJ, Sames D. Imaging induction of cytoprotective enzymes in intact human cells: coumberone, a metabolic reporter for human AKR1C enzymes reveals activation by panaxytriol, an active component of red ginseng. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(43):14123–8. 10.1021/ja801245y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bayer AG. A study to test whether study drug BAY1128688 brings pain relief to women with endometriosis and if so to get a first idea which dose(s) work best (AKRENDO1): Clinical trial synopsis 2019 Sep 05. Accessed February 23, 2023. https://clinicaltrials.bayer.com/study/17472/

- 13. Hilpert J, Groettrup-Wolfers E, Kosturski H, et al. Hepatotoxicity of AKR1C3 inhibitor BAY1128688: findings from an early terminated phase IIa trial for the treatment of endometriosis. Drugs in R&D. 10.1007/s40268-023-00427-5/DRDA-D-23-00010R1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Koal T, Schmiederer D, Pham-Tuan H, Röhring C, Rauh M. Standardized LC-MS/MS based steroid hormone profile-analysis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2012;129(3-5):129–138. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2011.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Unterwurzacher I, Koal T, Bonn GK, Weinberger KM, Ramsay SL. Rapid sample preparation and simultaneous quantitation of prostaglandins and lipoxygenase derived fatty acid metabolites by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry from small sample volumes. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2008;46(11):1589–1597. 10.1515/CCLM.2008.323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hoogland HJ, Skouby SO. Ultrasound evaluation of ovarian activity under oral contraceptives. Contraception. 1993;47(6):583–590. 10.1016/0010-7824(93)90025-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ke Y, Gonthier R, Labrie F. A sensitive and accurate LC-MS/MS assay with the derivatization of 1-amino-4-methylpiperazine applied to serum allopregnanolone, pregnenolone and androsterone in pre- and postmenopausal women. Steroids. 2017;118:25–31. 10.1016/j.steroids.2016.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shiraishi S, Lee PWN, Leung A, Goh VHH, Swerdloff RS, Wang C. Simultaneous measurement of serum testosterone and dihydrotestosterone by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Clin Chem. 2008;54(11):1855–1863. 10.1373/clinchem.2008.103846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mezzullo M, Pelusi C, Fazzini A, et al. Female and male serum reference intervals for challenging sex and precursor steroids by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2020;197:105538. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2019.105538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Reisch N, Taylor AE, Nogueira EF, et al. Alternative pathway androgen biosynthesis and human fetal female virilization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(44):22294–9. 10.1073/pnas.1906623116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pretorius E, Arlt W, Storbeck K-H. A new Dawn for androgens: novel lessons from 11-oxygenated C19 steroids. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2017;441:76–85. 10.1016/j.mce.2016.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Turcu AF, Rege J, Auchus RJ, Rainey WE. 11-Oxygenated androgens in health and disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16(5):284–296. 10.1038/s41574-020-0336-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. O'Reilly MW, Kempegowda P, Jenkinson C, et al. 11-Oxygenated C19 steroids are the predominant androgens in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(3):840–848. 10.1210/jc.2016-3285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Barnard M, Quanson JL, Mostaghel E, Pretorius E, Snoep JL, Storbeck K-H. 11-Oxygenated androgen precursors are the preferred substrates for aldo-keto reductase 1C3 (AKR1C3): implications for castration resistant prostate cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2018;183:192–201. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2018.06.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Reed BG, Carr BR. The normal menstrual cycle and the control of ovulation.In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, et al. eds. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2000. - . Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279054/. Last update: 05 Aug 2018. Last accessed: 19 Jun 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Prior JC, Naess M, Langhammer A, Forsmo S. Ovulation prevalence in women with spontaneous normal-length menstrual cycles—a population-based cohort from HUNT3, Norway. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0134473. 10.1371/journal.pone.0134473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hevir N, Vouk K, Šinkovec J, Ribič-Pucelj M, Rižner TL. Aldo-keto reductases AKR1C1, AKR1C2 and AKR1C3 may enhance progesterone metabolism in ovarian endometriosis. Chem Biol Interact. 2011;191(1-3):217–226. 10.1016/j.cbi.2011.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Huhtinen K, Desai R, Ståhle M, et al. Endometrial and endometriotic concentrations of estrone and estradiol are determined by local metabolism rather than circulating levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(11):4228–4235. 10.1210/jc.2012-1154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Huhtinen K, Saloniemi-Heinonen T, Keski-Rahkonen P, et al. Intra-tissue steroid profiling indicates differential progesterone and testosterone metabolism in the endometrium and endometriosis lesions. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(11):E2188–E2197. 10.1210/jc.2014-1913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Paulukinas RD, Mesaros CA, Penning TM. Conversion of classical and 11-oxygenated androgens by insulin-induced AKR1C3 in a model of human PCOS adipocytes. Endocrinology. 2022;163(7):bqac068. 10.1210/endocr/bqac068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Penning TM, Burczynski ME, Jez JM, et al. Structure-function aspects and inhibitor design of type 5 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (AKR1C3). Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2001;171(1-2):137–149. 10.1016/S0303-7207(00)00426-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rižner TL, Šmuc T, Rupreht R, Šinkovec J, Penning TM. AKR1C1 And AKR1C3 may determine progesterone and estrogen ratios in endometrial cancer. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;248(1-2):126–135. 10.1016/j.mce.2005.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Byrns MC, Mindnich R, Duan L, Penning TM. Overexpression of aldo-keto reductase 1C3 (AKR1C3) in LNCaP cells diverts androgen metabolism towards testosterone resulting in resistance to the 5α-reductase inhibitor finasteride. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2012;130(1-2):7–15. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2011.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sharma KK, Lindqvist A, Zhou XJ, Auchus RJ, Penning TM, Andersson S. Deoxycorticosterone inactivation by AKR1C3 in human mineralocorticoid target tissues. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;248(1-2):79–86. 10.1016/j.mce.2005.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.