Abstract

Background: Somatic TP53 mutations are frequent in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) and are important pathogenic factors. Objective: To study TP53 mutations relative to the presence of human papillomavirus (HPV) in tumors in HNSCC patients. Methods: Using a custom-made next-generation sequencing (NGS) panel on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor tissue, we analyzed somatic TP53 mutations and the TP53 single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) codon 72 (P72R; rs1042522) (proline → arginine) from 104 patients with HNSCC. Results: Only 2 of 44 patients with HPV-positive (HPV(+)) HNSCC had a TP53 somatic mutation, as opposed to 42/60 HPV-negative (HPV(−)) HNSCC patients (p < 0.001). Forty-five different TP53 somatic mutations were detected. Furthermore, in HPV(−) patients, we determined an 80% prevalence of somatic TP53 mutations in the TP53 R72 polymorphism cohort versus 40% in the TP53 P72 cohort (p = 0.001). A higher percentage of patients with oral cavity SCC had TP53 mutations than HPV(−) oropharyngeal (OP) SCC patients (p = 0.012). Furthermore, 39/44 HPV(+) tumor patients harbored the TP53 R72 polymorphism in contrast to 42/60 patients in the HPV(−) group (p = 0.024). Conclusions: Our observations show that TP53 R72 polymorphism is associated with a tumor being HPV(+). We also report a higher percentage of somatic TP53 mutations with R72 than P72 in HPV(−) HNSCC patients.

Keywords: head and neck cancer, TP53, somatic mutation, singe-nucleotide polymorphism, HPV

1. Introduction

More than 900,000 new cases of head and neck cancer (HNC) (lip, oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, or salivary glands) were reported worldwide in 2020, accounting for approximately 5% of the total incidence of major cancers. Worldwide, approximately 50% of newly diagnosed HNC patients survive 5 years following diagnosis [1]. In 2020, the incidence of HNC in Norway accounted for approximately 2.5% (n ≈ 800) of total cancer incidence, with curative treatment reported for approximately two-thirds of diagnosed patients [2].

The consumption of alcohol and tobacco, especially in combination, is a well-known risk factor for the development of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) [3]. Another risk factor for HNSCC is poor oral health [4]. In recent decades, investigators have firmly concluded that the human papillomavirus (HPV) virus is a causal agent in HNSCC, especially in oropharyngeal (OP) SCC. The incidence of OPSCC is increasing [5]. Furthermore, cancers with HPV-positive (+) tumors exhibit different biology than HPV-negative (−) tumors, with HPV(+) patients having a better prognosis than HPV(−) OPSCC patients [6], along with a different mutational profile [7].

HPV is a small, double-stranded, circular DNA virus that may infect the epithelial cells in the head and neck region. The most well-known oncogenes from high-risk subtypes of HPV are undoubtedly its E6 and E7 oncogenes [8]. E6 binds strongly and avidly to TP53, forming a complex with a ubiquitylation protein, E6-AP, which downregulates its tumor-suppressor functions [9]. The E7 protein, on the other hand, binds avidly to retinoblastoma (RB)-associated proteins 1 and 2, which drives the proteasomal destruction of RB and the release of the E2F family of transcription factors [10]. These E2F proteins push the cell cycle beyond the G1-S checkpoint into the S phase [11]. The E7 dysregulation of RB function leads to positive feedback upregulation of p16INK4A in HPV(+) tumors [12]. On the other hand, HPV(−) tumors have a very different cause, making their detailed investigation of paramount interest.

The genetic landscape of HNC includes various somatic mutations and chromosomal aberrations [13], as well as copy number variations and epigenetic changes [14]. The molecular mechanisms underlying carcinogenesis in classical HNSCC have been unraveled to some extent [15]. Carcinogenesis is considered a multistep process from dysplasia to cancer [16]. Reports published on the genomic analysis of HPV(−) HNSCC demonstrated findings of mutations such as TP53, CDKN2A, MLL2/3, NOTCH1, PIK3CA, NSD1, FBXW7, DDR2, and CUL3 [13,15,17,18]. The reported mutational profile varies to some extent, but TP53 is the most common mutated gene in HNSCC [18,19].

The p53 tumor-suppressor system participates in a variety of essential cell functions, such as cell cycle arrest, cellular senescence, DNA repair, apoptosis, autophagy, cell metabolism, immune system regulation, generation of reactive oxygen species, mitochondrial function, and global regulation of gene expression [19,20]. Furthermore, the mutation of the TP53 tumor-suppressor gene is the most common genetic alteration in human cancer [21]. Many different TP53 allelic variants have been reported in human tumors [21]. Cells with TP53 mutations may lose the ability to execute wild-type p53 functions to varying degrees [22] and act as dominant negative inhibitors of wild-type p53 tumor-suppressive functions [23].

Several well-characterized single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have also been reported in the TP53 gene. The common TP53 codon 72 SNP (P72R; rs1042522) is one of the most thoroughly studied [24,25]. The TP53 codon 72 SNP involves a change from cytosine to guanine in the coding sequence, resulting in a change from proline (P72) to arginine (R72) in the protein [26]. The TP53 R72 SNP has been reported to modulate the ability to induce apoptosis [27]. Furthermore, the E6 oncoprotein of high-risk HPV virus has been hypothesized to improve the degradation of TP53, which harbors arginine instead of proline [28], with the potential to modulate the risk of OPSCC in HPV-infected patients.

Yeast transcription assays indicate more TP53 mutations are associated with the codon 72 arginine than proline relative to their prevalence in the germline [29]. Various studies have also shown that this TP53 SNP may affect apoptosis and cell cycle progression [27,30] by, e.g., enhancing the metastatic potential of mutant TP53 in cell lines with the TP53 R72 (arginine) SNP compared to mutated cell lines with the ancestral TP53 P72 (proline) SNP [31]. In support of this phenomenon, cell lines harboring some specific somatic TP53 mutations have been shown to exhibit more aggressive growth in association with the TP53 R72 SNP than the TP53 P72 SNP [32]. Furthermore, an increased prevalence of the TP53 R72 SNP has been observed in humans living in higher latitudes and colder climates [33].

The aim of this study was to identify the rate and repertoire of TP53 somatic mutations and the prevalence of the TP53 R72 (arginine) SNP, as well as the relationship between these parameters in a cohort of both HPV(+) and HPV(−) HNSCC patients. Such results may explain why some acquire HNSCC.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Population and Study Design

Since 1992, all patients with head and neck cancer (HNC) at the Department of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, Haukeland University Hospital (HUH), Bergen, Norway, have been registered in a hospital-based HNC registry. HUH treats all cases of HNC in the Western Health Care Region of Norway. This region includes 1.1 million inhabitants.

All HNSCC patients were subjected to a standardized diagnostic workup, including clinical examination; CT/MRI scans of the primary tumor site, neck, thorax and liver; and ultrasonographic examination of the neck with fine-needle aspiration cytology if indicated. If possible, a diagnostic endoscopic examination was performed under general anesthesia. From this cohort, we extracted 104 patients diagnosed during the period from 2003 to 2016 for further analysis. The clinical data for each patient were obtained from a retrospective chart review. The tumor site was classified according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), 10th edition. The TNM stage was classified according to the International Union against Cancer (IUCC), 7th edition.

2.2. Protocols for HPV Detection

For the detection of HPV DNA, standard Gp5+/Gp6+ primers were used, as previously described [6,34].

2.3. NGS Panel Preparation and Analysis

DNA isolation, HPV detection, and our custom-made next-generation sequencing (NGS) panel were previously described [17]. Briefly, an experienced pathologist selected representative tumor samples. The tumors represented primary HNC diagnostic or surgical samples collected in the diagnostic workup. DNA was isolated from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) blocks. DNA was extracted using a commercially available DNA extraction kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (E.Z.N.A tissue DNA kit, Omega BioTek, Norcross, GA, USA), and the DNA concentration was quantified (Qubit dsDNA BR assay, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Then, 50 ng of DNA was used to prepare amplicon libraries using an AmpliSeq Library PLUS kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Thereafter, the DNA was purified with AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coluter, High Wycombe, UK). To reduce the fixation impact, the two last steps were repeated before final quantification (Qubit dsDNA HS Kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). In the end, 1.3 pM of the library was loaded for paired-end sequencing using the Illumina MiniSeq platform, and further data management was performed in BaseSpace Sequence Hub (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA).

Bioinformatics analysis was performed using the DNA amplicon v2.2.1 workflow in BaseSpace (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The full coding sequence of TP53 was aligned to the hg19/GRCh37 reference genome using the Burrows–Wheeler aligner. Variants were called using the somatic variant caller and annotated by RefSeq using the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database. A total amplicon depth (coverage) of more than 500 reads and a variant allele (VAF) of 5% were set as strict thresholds. Only coding sequences were examined. The recorded variants were evaluated in the dbSNP (NCBI) and Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (Cosmic) databases.

2.4. Statistical Analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS statistical program (IBM Corp., IBM SPSS Statistic for Windows, Version 26.0, Armok, NY, USA). Student’s t-test and the Mann–Whitney test were used to compare groups. The p-value for the two-sided test is reported.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Variables

The present cohort (n = 104) represents a subgroup of the entire group of patients diagnosed with HNSCC in western Norway during the period from 2003 to 2016. The primary tumor sites were the oropharynx (OP) and the oral cavity (OC) (Table 1). Table 1 shows the age, gender, and TNM stage of patients in the studied cohort sorted by tumor HPV status. Among the 104 included patients, 60 had HPV(−) tumors, and 44 had tumors that were HPV(+). Almost all HPV(+) tumors were positive for HPV type 16, except for four tumors, including two tumors that were positive for HPV18, one that was positive for HPV33, and one that was positive for HPV58.

Table 1.

Clinical patient characteristics by site/tumor HPV status upon diagnosis.

| Variable | Oral | Other | Oropharynx HPV(−) |

Oropharynx HPV(+) |

Sign. HPV(−) vs. HPV(+) Condition | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Years Mean ± SD | 60.6 ± 12.5 | 68.0 ± 3.2 | 65.1 ± 10.4 | 59.4 ± 10.1 | p < 0.001 |

| Gender | Males | 28 | 4 | 27 | 37 | n.s. |

| Females | 11 | 0 | 4 | 7 | ||

| T stage | 1 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 5 | n.s. |

| 2 | 13 | 1 | 12 | 21 | ||

| 3 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 6 | ||

| 4 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 11 | ||

| TNM n.a. | 2 | 1 | ||||

| N stage | 0 | 21 | 2 | 11 | 9 | p = 0.001 |

| 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 | ||

| 2 | 6 | 1 | 9 | 27 | ||

| 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 | ||

| M stage | 0 | 29 | 4 | 22 | 43 | |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | ||

| Smoking | <10 tobacco years | 15 | 0 | 2 | 17 | n.s. |

| >10 tobacco years | 14 | 4 | 25 | 27 | ||

| Total number of patients | 29 | 4 | 27 | 44 |

Site according to International Classification Diseases, 10th edition; TNM stage according to the 7th TNM classification of malignant tumors of the International Union Against Cancer; n.a. = not applicable (three patients with metastasis without a primary tumor (C77.0) were not classified by TNM stage, but tumors were considered to originate from the oropharynx).

3.2. TP53 Somatic Mutations Detected in the Study Cohort

The mean age among the HPV(−) tumor patients was 63.1 ± 11.3 years versus 59.4 ± 10.1 years among the HPV(+) tumor patients. Regarding the TNM stage, only the N stage differed between the HPV(−) and HPV(+) tumor groups (Table 1). Smoking history did not statistically significantly differ between HPV(+) and HPV(−) patients (Table 1).

A total of 45 different TP53 mutations were registered (Supplementary Table S1). Of the detected single-base mutations, 36 were pathogenic, and 3 were neutral according to Functional Analysis through Hidden Markov Model (FATHMM) software version 2.3 [35] (Supplementary Table S1). In addition, six were insertions/deletions. A total of 44 of 104 patients had somatic TP53 mutations (Table 2, upper frame). Furthermore, 34 patients had 1 TP53 somatic mutation, 9 patients had 2, and 1 patient had 3 (Table 3, upper frame).

Table 2.

Patients (n) with TP53 mutation dependent on presence of TP53 R72 SNP.

| TP53 R72 SNP (Arg) | TP53 Mutations | Total Patients | Statistics by Mann–Whitney | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||

| All Included Patients | ||||

| No | 15 | 8 | 23 | |

| Yes | 45 | 36 | 81 | |

| Total patients | 60 | 44 | 104 | |

| Tumor HPV(−) patients | ||||

| No | 11 | 7 | 18 | Z = −3.41 p < 0.001 |

| Yes | 7 | 35 | 42 | |

| Total patients | 18 | 42 | 60 | |

| Tumor HPV(+) patients | ||||

| No | 4 | 1 | 5 | |

| Yes | 38 | 1 | 39 | |

| Total patients | 42 | 2 | 44 | |

| Oropharynx tumor HPV(−) patients | ||||

| No | 7 | 2 | 9 | Z = −2.42 p = 0.016 |

| Yes | 5 | 13 | 18 | |

| Total patients | 12 | 15 | 27 | |

| Oral cavity patients (all HPV(−)) | ||||

| No | 4 | 3 | 7 | Z = −3.15 p = 0.002 |

| Yes | 1 | 21 | 22 | |

| Total patients | 5 | 24 | 29 | |

Table 3.

Number of somatic TP53 mutations in patients with TP53 R72 SNP (Arg).

| TP53 R72 SNP | No. of TP53 Mutations per Patient | Total Patients | Statistics by Mann–Whitney | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| All Patients Included | ||||||

| No | 15 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 23 | |

| Yes | 45 | 28 | 7 | 1 | 81 | |

| Total patients | 60 | 34 | 9 | 1 | 104 | |

| Tumor HPV(−) all patients | ||||||

| No | 11 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 18 | Z = −2.85 p = 0.004 |

| Yes | 7 | 28 | 6 | 1 | 42 | |

| Total patients | 18 | 33 | 8 | 1 | 60 | |

| Tumor HPV(+) all patients | ||||||

| No | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | |

| Yes | 38 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 39 | |

| Total patients | 42 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 44 | |

| Tumor HPV(−) oropharynx patients | ||||||

| No | 7 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 9 | Z = −2.01 p = 0.044 |

| Yes | 5 | 12 | 1 | 0 | 18 | |

| Total patients | 12 | 13 | 2 | 0 | 27 | |

| All oral cavity patients | ||||||

| No | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 7 | Z = −2.27 p = 0.023 |

| Yes | 1 | 15 | 5 | 1 | 22 | |

| Total patients | 5 | 17 | 6 | 1 | 29 | |

Of patients with tumor somatic TP53 mutations, 42 patients were HPV(−), and two were HPV(+) (Table 2), which is a highly significant difference (z = −6.64; p < 0.001). Among the HPV(−) patients, 33 had one somatic TP53 mutation, 8 patients had two TP53 mutations, and one patient had three TP53 mutations (Table 3). Of the 44 patients with HPV(+) tumors, one had one TP53 mutation, and one had two (Table 3), constituting a highly significant difference between the HPV(+) and HPV(−) tumors (z = −6.38; p < 0.001).

3.3. Detection of TP53 P72R in HPV(+) and HPV(−) HNSCC Patients

The TP53 somatic mutations were distributed differently among the HPV(−) patients when comparing OP (15/27 cases) versus OC (24/29 cases) origin (z = −2.19; p = 0.028) (Table 4). Moreover, for HPV(−) patients, the presence of a TP53 mutation was associated with the TP53 R72 polymorphism (Table 2) (z = −3.41; p < 0.001). For OPSCC HPV(−) (z = 2.01; p = 0.044) and OC (z = 2.27; p = 0.023) patients, there was also a preference for R72 regarding the number of TP53 mutations (Table 3).

Table 4.

TP53 mutations in HPV(−) HNSCC patients (n) by tumor site (localization).

| Site | Total Patients | Mann–Whitney Statistics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oropharynx | Oral Cavity | Other | ||||

| TP53 mutation | No | 12 | 5 | 1 | 18 | Z = −2.19 p = 0.028 (OP vs. OC) |

| Yes | 15 | 24 | 3 | 42 | ||

| Total | 27 | 29 | 4 | 60 | ||

TP53 R72 polymorphism was associated with an increased presence of somatic TP53 mutations in HPV(−) patients. Among the 18 HPV(−) TP53 mutant-negative patients, only 7 harbored the TP53 R72 SNP, whereas among the 42 HPV(−) TP53 somatic-mutated patients, 35 patients harbored this SNP (Table 2) (z = −3.41; p < 0.001). In addition, when the number of TP53 somatic mutations was included in the analyses, the TP53 R72 SNP was also associated with TP53 mutations (Table 3) (z = −2.85; p = 0.004).

In HPV(+) HNSCC patients, there was a preponderance of patients with the TP53 arginine codon 72 polymorphism. A total of 39 of 44 patients had this SNP in the HPV(+) group, whereas 42 of 60 carried this SNP in the HPV(−) group of patients (z = −2.25; p = 0.024) (Table 5). Among the OPSCC patients only, the results were similar (z = −2.24; p = 0.025) (Table 5).

Table 5.

The presence of TP53 R72 SNP according to tumor HPV status.

| Tumor HPV | Total Patients | Mann–Whitney Statistics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||||

| All patients | |||||

| TP53 R72 | No | 18 | 5 | 23 | Z = −2.25 p = 0.024 |

| Yes | 42 | 39 | 81 | ||

| Total patients | 60 | 44 | 104 | ||

| Oropharynx patients | |||||

| TP53 R72 | No | 9 | 5 | 14 | Z = −2.24 p = 0.025 |

| Yes | 18 | 39 | 57 | ||

| Total patients | 27 | 44 | 71 | ||

Among the five HPV(+) SCC patients with the TP53 P72 SNP (proline), one patient had a somatic TP53 mutation (Table 2). In two of these patients, pathogenic mutations were observed in the TRAF3 gene and in the FGFR3 gene, respectively (Table 6). In the other three patients, no further mutations were detected with the employed NGS panel [17] (Table 6).

Table 6.

Clinical profile of TP53 P72 (proline) HPV(+) tumors.

| Patient Number | HPV Serotype | Any Pathogenic Mutation(s) | Age at Diagnosis | Smoking | Site | Site ICD 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 58 |

TP53 TRAF-3 |

67 | Yes | Tonsil | C09.9 |

| 2 | 16 | FGFR-3 | 49 | No | Base of tongue | C01 |

| 3 | 16 | n.d. | 84 | Yes | Pharynx—overlapping | C10.8 |

| 4 | 16 | n.d. | 73 | No | Tonsillar pillar | C09.1 |

| 5 | 16 | n.d. | 67 | No | Tonsil | C09.9 |

n.d.= not detected.

4. Discussion

TP53 has a complex interplay with several cellular pathways, including key roles in cell function [20], maintaining genetic stability [25], and carcinogenesis when mutated [36]. Somatic mutations in the TP53 gene are a common cancer feature [37,38]. Most mutations in the TP53 gene are single-base missense mutations altering the encoding amino acid [38]. Several TP53 mutations tend to be clustered (so-called hotspot mutation), as reported in HNSCC [22]. The TP53 gene codes for one protein with many possible TP53 mutations [21]. Our NGS panel had full coverage of the TP53 coding sequence, including all common TP53 hotspot somatic mutations [17]. In addition, the tumor microenvironment, both within the tumor cells and the cellular tumor landscape, is important [39,40,41]. Regarding prognosis and treatment responses, HNSCC tumors have especially been shown to interact with the general immune system [42,43].

In the present study, many different and well-characterized TP53 somatic mutations were encountered in the HPV(−) cohort of HNSCC patients. Some patients in this group also harbored multiple somatic TP53 mutations. In the HPV(+) group of patients, only one pathogenic TP53 missense mutation was encountered, which is likely related to the well-established effect of HPV viral oncoprotein E6, enabling the capture of the host p53 tumor suppressor protein [44]. Furthermore, tobacco smoking has been associated with increased levels of TP53 somatic mutations in HNSCC [45], but there was no significant difference with respect to smoking habits in the HPV(+) versus HPV(−) cohort of patients in our study. This could support that infection with HPV virus protects against TP53 mutations.

In the reported study, mutations in the TP53 gene were analyzed, with an additional focus on the TP53 codon 72 SNP, resulting in an arginine-reading codon from a proline-reading codon (rs1042522). Ancestral TP53 P72 occurs more frequently in equatorial human populations, whereas the TP53 R72 polymorphism occurs more commonly at higher latitudes, including in the Norwegian population [24]. In this respect, we observed a 73.5% prevalence of TP53 R72 SNPs in HPV(−) HNSCC patients, which seems to be at the high end of various European population estimates [46]. Furthermore, TP53 R72 SNPs were detected in most HPV(+) HNSCC patients, with the exception of five patients, giving an 89% prevalence among the HPV(+) patients, which is a significantly higher preponderance of this particular SNP than among the HPV(−) patients.

A limitation of our study is that analyses were performed only in tumor cells, as the TP53 R72 SNP in heterozygous individuals may be selected for tumor cells. In principle, the reported observations may be influenced by a loss of heterozygosity [32,47]. We have, however, not differentiated TP53 allele status in our analyses.

A major observation from our study is that in HNSCC HPV(−) patients, somatic TP53 mutations were associated with TP53 R72 SNPs. TP53 R72 SNPs have previously been associated with HNSCC in a Brazilian study [48]. An association of TP53 R72 SNPs with oral cancer has also been reported [49]. However, in a study by Jiang et al., no such association was found [50]. Previous studies have also reported an association of TP53 R72 SNPs with laryngeal cancer [51]. In yet another recent study, Escalante et al. suggested that TP53 R72 SNPs may be a risk factor for the pathogenesis of laryngeal cancer [52]. In addition, in the upper gastrointestinal tract, an increased risk of esophageal SCC has been associated with TP53 R72 SNPs [53], as also suggested regarding lung and breast cancer in a South Asian population [54]. In other HPV-associated cancers, such as uterine cervical cancer, TP53 R72 SNPs have been suggested to be more common in HPV(+) than HPV(−) cancers [55]. In the above-mentioned study, an association with HPV E6/E7 mRNA expression was also found, which also suggests a role for TP53 R72 SNPs in the establishment of HPV-associated cancer disease, HNSCC included [55].

The prevalence of TP53 R72 SNPs differs dependent on genetic descent, i.e., it is more prevalent in the northern hemisphere [24,33]. The distribution of these polymorphisms is likely bound to natural protection against ultraviolet radiation [24,33]. How this polymorphism affects HNSCC carcinogenesis is therefore not known, but explanations may range from a bystander effect to important clues of HNSCC generation. In any case, this might help explain why HNSCC cancer is more common among ethnic Caucasian individuals than ethnic Sub-Saharan Africans [24,56]. These hypotheses with respect to head and neck cancer and its possible association with TP53 R72 SNPs, however, require further investigation.

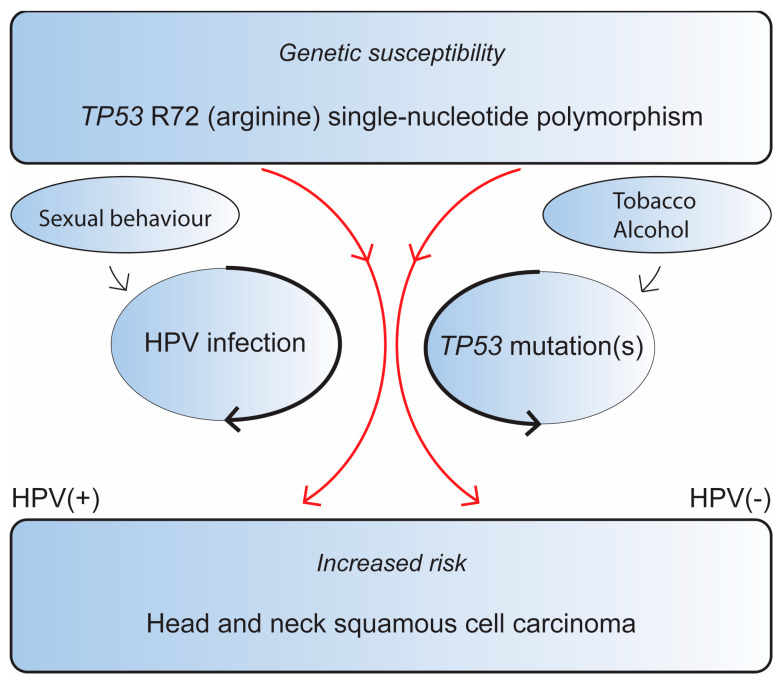

We propose two distinct pathways where the TP53 R72 SNPs increases the risk of HNSCC, both of which occur through dysregulation of the TP53 pathway. It appears to increase the risk of persistent HPV infection, leading to an increased risk of HPV(+) OPSCC, and it is associated with increased TP53 mutations, resulting in HPV(−) HNSCC (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

TP53 R72 SNPs influence the risk of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma depending on the HPV status of the tumor. Red arrows indicate the SNPs dual pathway with regards to HPV-tumor status. Black arrows indicate that persistent HPV-infection and TP53 mutations, respectively, further influence the risk of HNSCC development.

Our methodology shows the robustness of studying somatic mutations in archival material, thus providing clinicians with a broader repertoire in clinical decision-making as well as forming a basis for research [17]. Regarding future investigations, it is possible to study whether TP53 R72 or TP53 somatic mutations are associated with a changed sensitivity to immune therapy. Thus, TP53 status may become an even stronger part of precision medicine [43,57]. It is also of interest to study the role of TP53 R72 SNPs in more detail in other SCCs [53,54,55]. Furthermore, whether an SCC lung tumor constitutes an HNSCC metastasis or a primary lung tumor is an important clinical question. In addition to HPV analysis, based on the large variation of TP53 mutations found in our study, the determination of the exact TP53 and other mutation(s) present in the tumor could help answer this.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we showed a higher prevalence of the codon 72 single-nucleotide polymorphism TP53 R72 (i.e., proline → arginine) in HPV(+) OPSCC versus HPV(−) HNSCC and reported an association of the TP53 R72 SNP with an increased prevalence of TP53 somatic mutations in HPV(−) HNSCC. We have formulated our two main supported hypotheses in Figure 1. The TP53 R72 SNP might contribute to TP53 dysregulation through two pathways: either by increasing the risk of chronic HPV infection, leading to HPV(+) OPSCC, or by influencing the risk of acquiring TP53 mutations in HPV(−) HNSCC. The suggested mechanisms might shed some light on why Caucasians are more prone to HNSCC.

Acknowledgments

The technical assistance of Kalaiarasy Kugarajh is gratefully acknowledged.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/biomedicines11071838/s1, Table S1: Exact TP53 mutations detected by HPV status of patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.J.A., O.K.V., D.-E.C. and S.E.M.; data curation, S.E.M., S.F. and M.B.; formal analysis, S.E.M., H.J.A. and S.F.; investigation, S.E.M., S.L. and H.J.A.; methodology, O.K.V., S.F., S.M.D. and H.N.D.; validation, O.K.V. and H.N.D., writing—original draft, S.E.M. and H.J.A.; writing—review and editing, S.E.M., F.A.E., H.N.D., D.-E.C., S.L., M.B., S.M.D., S.F., O.K.V. and H.J.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board Ethics Committee of the Western Part of Norway (Health West) (protocol code 125-2/17 February 2011).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the fact that the data were acquired over a long period of time, many of the patients are dead, and it is of paramount importance to include all eligible patients to ensure the validity of the results concerning patients diagnosed through 2012. For inclusions as of 2013, informed consent was obtained from all patients involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data from this study are not allowed to be shared with anyone due to national legal regulations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research received external funding from the Central Health West authorities with grant number F-12125.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., Laversanne M., Soerjomataram I., Jemal A., Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cancer Registry of Norway . Cancer in Norway 2021—Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Survival and Prevalance in Norway. Cancer Registry of Norway; Oslo, Norway: 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Varoni E.M., Lodi G., Iriti M. Ethanol versus Phytochemicals in Wine: Oral Cancer Risk in a Light Drinking Perspective. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015;16:17029–17047. doi: 10.3390/ijms160817029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michaud D.S., Fu Z., Shi J., Chung M. Periodontal Disease, Tooth Loss, and Cancer Risk. Epidemiol. Rev. 2017;39:49–58. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxx006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jemal A., Simard E.P., Dorell C., Noone A.M., Markowitz L.E., Kohler B., Eheman C., Saraiya M., Bandi P., Saslow D., et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, 1975-2009, featuring the burden and trends in human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated cancers and HPV vaccination coverage levels. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2013;105:175–201. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ljokjel B., Lybak S., Haave H., Olofsson J., Vintermyr O.K., Aarstad H.J. The impact of HPV infection on survival in a geographically defined cohort of oropharynx squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) patients in whom surgical treatment has been one main treatment. Acta Otolaryngol. 2014;134:636–645. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2014.886336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seiwert T.Y., Zuo Z., Keck M.K., Khattri A., Pedamallu C.S., Stricker T., Brown C., Pugh T.J., Stojanov P., Cho J., et al. Integrative and comparative genomic analysis of HPV-positive and HPV-negative head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015;21:632–641. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-3310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoppe-Seyler K., Bossler F., Braun J.A., Herrmann A.L., Hoppe-Seyler F. The HPV E6/E7 Oncogenes: Key Factors for Viral Carcinogenesis and Therapeutic Targets. Trends Microbiol. 2018;26:158–168. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scheffner M., Huibregtse J.M., Vierstra R.D., Howley P.M. The HPV-16 E6 and E6-AP complex functions as a ubiquitin-protein ligase in the ubiquitination of p53. Cell. 1993;75:495–505. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90384-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tomita T., Huibregtse J.M., Matouschek A. A masked initiation region in retinoblastoma protein regulates its proteasomal degradation. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:2019. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16003-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cam H., Dynlacht B.D. Emerging roles for E2F: Beyond the G1/S transition and DNA replication. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:311–316. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D’Arcangelo D., Tinaburri L., Dellambra E. The Role of p16(INK4a) Pathway in Human Epidermal Stem Cell Self-Renewal, Aging and Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:1591. doi: 10.3390/ijms18071591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farah C.S. Molecular landscape of head and neck cancer and implications for therapy. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021;9:915. doi: 10.21037/atm-20-6264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ribeiro I.P., Caramelo F., Ribeiro M., Machado A., Migueis J., Marques F., Carreira I.M., Melo J.B. Upper aerodigestive tract carcinoma: Development of a (epi)genomic predictive model for recurrence and metastasis. Oncol. Lett. 2020;19:3459–3468. doi: 10.3892/ol.2020.11459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leemans C.R., Snijders P.J.F., Brakenhoff R.H. The molecular landscape of head and neck cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2018;18:269–282. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2018.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perri F., Della Vittoria Scarpati G., Pontone M., Marciano M.L., Ottaiano A., Cascella M., Sabbatino F., Guida A., Santorsola M., Maiolino P., et al. Cancer Cell Metabolism Reprogramming and Its Potential Implications on Therapy in Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck: A Review. Cancers. 2022;14:3560. doi: 10.3390/cancers14153560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dongre H.N., Haave H., Fromreide S., Erland F.A., Moe S.E.E., Dhayalan S.M., Riis R.K., Sapkota D., Costea D.E., Aarstad H.J., et al. Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing of Cancer-Related Genes in a Norwegian Patient Cohort With Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Reveals Novel Actionable Mutations and Correlations with Pathological Parameters. Front. Oncol. 2021;11:734134. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.734134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cancer Genome Atlas N. Comprehensive genomic characterization of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Nature. 2015;517:576–582. doi: 10.1038/nature14129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodriguez-Ramirez C., Nor J.E. p53 and Cell Fate: Sensitizing Head and Neck Cancer Stem Cells to Chemotherapy. Crit. Rev. Oncog. 2018;23:173–187. doi: 10.1615/CritRevOncog.2018027353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levine A.J. p53: 800 million years of evolution and 40 years of discovery. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2020;20:471–480. doi: 10.1038/s41568-020-0262-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kennedy M.C., Lowe S.W. Mutant p53: It’s not all one and the same. Cell Death Differ. 2022;29:983–987. doi: 10.1038/s41418-022-00989-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou G., Liu Z., Myers J.N. TP53 Mutations in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Their Impact on Disease Progression and Treatment Response. J. Cell. Biochem. 2016;117:2682–2692. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murai K., Dentro S., Ong S.H., Sood R., Fernandez-Antoran D., Herms A., Kostiou V., Abnizova I., Hall B.A., Gerstung M., et al. p53 mutation in normal esophagus promotes multiple stages of carcinogenesis but is constrained by clonal competition. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:6206. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-33945-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hoyos D., Greenbaum B., Levine A.J. The genotypes and phenotypes of missense mutations in the proline domain of the p53 protein. Cell Death Differ. 2022;29:938–945. doi: 10.1038/s41418-022-00980-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olivier M., Hollstein M., Hainaut P. TP53 mutations in human cancers: Origins, consequences, and clinical use. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010;2:a001008. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whibley C., Pharoah P.D., Hollstein M. p53 polymorphisms: Cancer implications. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2009;9:95–107. doi: 10.1038/nrc2584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dumont P., Leu J.I., Della Pietra A.C., 3rd, George D.L., Murphy M. The codon 72 polymorphic variants of p53 have markedly different apoptotic potential. Nat. Genet. 2003;33:357–365. doi: 10.1038/ng1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Storey A., Thomas M., Kalita A., Harwood C., Gardiol D., Mantovani F., Breuer J., Leigh I.M., Matlashewski G., Banks L. Role of a p53 polymorphism in the development of human papillomavirus-associated cancer. Nature. 1998;393:229–234. doi: 10.1038/30400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tada M., Furuuchi K., Kaneda M., Matsumoto J., Takahashi M., Hirai A., Mitsumoto Y., Iggo R.D., Moriuchi T. Inactivate the remaining p53 allele or the alternate p73? Preferential selection of the Arg72 polymorphism in cancers with recessive p53 mutants but not transdominant mutants. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:515–517. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.3.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pim D., Banks L. p53 polymorphic variants at codon 72 exert different effects on cell cycle progression. Int. J. Cancer. 2004;108:196–199. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Basu S., Gnanapradeepan K., Barnoud T., Kung C.P., Tavecchio M., Scott J., Watters A., Chen Q., Kossenkov A.V., Murphy M.E. Mutant p53 controls tumor metabolism and metastasis by regulating PGC-1alpha. Genes Dev. 2018;32:230–243. doi: 10.1101/gad.309062.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Souza C., Madden J., Koestler D.C., Minn D., Montoya D.J., Minn K., Raetz A.G., Zhu Z., Xiao W.-W., Tahmassebi N., et al. Effect of the p53 P72R Polymorphism on Mutant TP53 Allele Selection in Human Cancer. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2021;113:1246–1257. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djab019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beckman G., Birgander R., Sjalander A., Saha N., Holmberg P.A., Kivela A., Beckman L. Is p53 polymorphism maintained by natural selection? Hum. Hered. 1994;44:266–270. doi: 10.1159/000154228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ojesina A.I., Lichtenstein L., Freeman S.S., Pedamallu C.S., Imaz-Rosshandler I., Pugh T.J., Cherniack A.D., Ambrogio L., Cibulskis K., Bertelsen B., et al. Landscape of genomic alterations in cervical carcinomas. Nature. 2014;506:371–375. doi: 10.1038/nature12881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shihab H.A., Rogers M.F., Gough J., Mort M., Cooper D.N., Day I.N., Gaunt T.R., Campbell C. An integrative approach to predicting the functional effects of non-coding and coding sequence variation. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:1536–1543. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nathan C.A., Khandelwal A.R., Wolf G.T., Rodrigo J.P., Makitie A.A., Saba N.F., Forastiere A.A., Bradford C.R., Ferlito A. TP53 mutations in head and neck cancer. Mol. Carcinog. 2022;61:385–391. doi: 10.1002/mc.23385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hollstein M., Sidransky D., Vogelstein B., Harris C.C. p53 mutations in human cancers. Science. 1991;253:49–53. doi: 10.1126/science.1905840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bouaoun L., Sonkin D., Ardin M., Hollstein M., Byrnes G., Zavadil J., Olivier M. TP53 Variations in Human Cancers: New Lessons from the IARC TP53 Database and Genomics Data. Hum. Mutat. 2016;37:865–876. doi: 10.1002/humu.23035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Montemurro N., Fanelli G.N., Scatena C., Ortenzi V., Pasqualetti F., Mazzanti C.M., Morganti R., Paiar F., Naccarato A.G., Perrini P. Surgical outcome and molecular pattern characterization of recurrent glioblastoma multiforme: A single-center retrospective series. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2021;207:106735. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2021.106735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ljokjel B., Haave H., Lybak S., Vintermyr O.K., Helgeland L., Aarstad H.J. Tumor Infiltration Levels of CD3, Foxp3 (+) Lymphocytes and CD68 Macrophages at Diagnosis Predict 5-Year Disease-Specific Survival in Patients with Oropharynx Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancers. 2022;14:1508. doi: 10.3390/cancers14061508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Montemurro N., Pahwa B., Tayal A., Shukla A., De Jesus Encarnacion M., Ramirez I., Nurmukhametov R., Chavda V., De Carlo A. Macrophages in Recurrent Glioblastoma as a Prognostic Factor in the Synergistic System of the Tumor Microenvironment. Neurol. Int. 2023;15:595–608. doi: 10.3390/neurolint15020037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aarstad H.H., Moe S.E.E., Bruserud O., Lybak S., Aarstad H.J., Tvedt T.H.A. The Acute Phase Reaction and Its Prognostic Impact in Patients with Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Single Biomarkers Including C-Reactive Protein Versus Biomarker Profiles. Biomedicines. 2020;8:418. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines8100418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Poulose J.V., Kainickal C.T. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: A systematic review of phase-3 clinical trials. World J. Clin. Oncol. 2022;13:388–411. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v13.i5.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rampias T., Sasaki C., Weinberger P., Psyrri A. E6 and e7 gene silencing and transformed phenotype of human papillomavirus 16-positive oropharyngeal cancer cells. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2009;101:412–423. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brennan J.A., Boyle J.O., Koch W.M., Goodman S.N., Hruban R.H., Eby Y.J., Couch M.J., Forastiere A.A., Sidransky D. Association between cigarette smoking and mutation of the p53 gene in squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;332:712–717. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503163321104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Karczewski K.J., Francioli L.C., Tiao G., Cummings B.B., Alfoldi J., Wang Q., Collins R.L., Laricchia K.M., Ganna A., Birnbaum D.P., et al. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature. 2020;581:434–443. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2308-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marin M.C., Jost C.A., Brooks L.A., Irwin M.S., O’Nions J., Tidy J.A., James N., McGregor J.M., Harwood C.A., Yulug I.G., et al. A common polymorphism acts as an intragenic modifier of mutant p53 behaviour. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:47–54. doi: 10.1038/75586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pinheiro U.B., Fraga C.A., Mendes D.C., Farias L.C., Cardoso C.M., Silveira C.M., D’Angelo M.F., Jones K.M., Santos S.H., de Paula A.M., et al. Fuzzy clustering demonstrates that codon 72 SNP rs1042522 of TP53 gene associated with HNSCC but not with prognoses. Tumour Biol. 2015;36:9259–9265. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3677-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hou J., Gu Y., Hou W., Wu S., Lou Y., Yang W., Zhu L., Hu Y., Sun M., Xue H. P53 codon 72 polymorphism, human papillomavirus infection, and their interaction to oral carcinoma susceptibility. BMC Genet. 2015;16:72. doi: 10.1186/s12863-015-0235-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jiang N., Pan J., Wang L., Duan Y.Z. No significant association between p53 codon 72 Arg/Pro polymorphism and risk of oral cancer. Tumour Biol. 2013;34:587–596. doi: 10.1007/s13277-012-0587-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fernandez-Mateos J., Seijas-Tamayo R., Adansa Klain J.C., Pastor Borgonon M., Perez-Ruiz E., Mesia R., Del Barco E., Salvador Coloma C., Rueda Dominguez A., Caballero Daroqui J., et al. Genetic Susceptibility in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma in a Spanish Population. Cancers. 2019;11:493. doi: 10.3390/cancers11040493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Escalante P., Barria T., Cancino M., Rahal M., Cerpa L., Sandoval C., Molina-Mellico S., Suarez M., Martinez M., Caceres D.D., et al. Genetic polymorphisms as non-modifiable susceptibility factors to laryngeal cancer. Biosci. Rep. 2020;40:BSR20191188. doi: 10.1042/BSR20191188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhao L., Zhao X., Wu X., Tang W. Association of p53 Arg72Pro polymorphism with esophageal cancer: A meta-analysis based on 14 case-control studies. Genet. Test. Mol. Biomark. 2013;17:721–726. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2013.0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jafrin S., Aziz M.A., Anonna S.N., Akter T., Naznin N.E., Reza S., Islam M.S. Association of TP53 Codon 72 Arg>Pro Polymorphism with Breast and Lung Cancer Risk in the South Asian Population: A Meta-Analysis. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2020;21:1511–1519. doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2020.21.6.1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chuery A.C.S., Silva I., Ribalta J.C.L., Speck N.M.G. Association between the p53 arginine/arginine homozygous genotype at codon 72 and human papillomavirus E6/E7 mRNA expression. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2017;21:248–254. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Johnson D.E., Burtness B., Leemans C.R., Lui V.W.Y., Bauman J.E., Grandis J.R. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2020;6:92. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-00224-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu Y., Leslie P.L., Zhang Y. Life and Death Decision-Making by p53 and Implications for Cancer Immunotherapy. Trends Cancer. 2021;7:226–239. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2020.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data from this study are not allowed to be shared with anyone due to national legal regulations.