Abstract

Improvements to enhanced recovery pathways in orthopedic surgery are reducing the time that patients spend in the hospital, giving an increasingly vital role to prehabilitation and/or rehabilitation after surgery. Nutritional support is an important tenant of perioperative medicine, with the aim to integrate the patient’s diet with food components that are needed in greater amounts to support surgical fitness. Regardless of the time available between the time of contemplation of surgery and the day of admission, a patient who eats healthy is reasonably more suitable for surgery than a patient who does not meet the daily requirements for energy and nutrients. Moreover, a successful education for healthy food choices is one possible way to sustain the exercise therapy, improve recovery, and thus contribute to the patient’s long-term health. The expected benefits presuppose that the patient follows a healthy diet, but it is unclear which advice is needed to improve dietary choices. We present the principles of healthy eating for patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery to lay the foundations of rational and valuable perioperative nutritional support programs. We discuss the concepts of nutritional use of food, requirements, portion size, dietary target, food variety, time variables of feeding, and the practical indications on what the last meal to be consumed six hours before the induction of anesthesia may be together with what is meant by clear fluids to be consumed until two hours before. Surgery may act as a vital “touch point” for some patients with the health service and is therefore a valuable opportunity for members of the perioperative team to promote optimal lifestyle choices, such as the notion and importance of healthy eating not just for surgery but also for long-term health benefit.

Keywords: orthopedic surgery, prehabilitation, nutrition therapy, food and beverage, perioperative medicine, preoperative conditioning

Introduction

Perioperative medicine deals with the surgical patient from the time of contemplation of surgery to full recovery. In the context of modern-day elective surgery involving the hip, knee, and spine, hospitalization is a short stay focusing on the appropriateness of surgical, anesthetic, nursing, and rehabilitation practices. Therefore, the period before hospitalization arouses the most interest for what concerns patient education on how to best prepare for surgery. This material can be reported in information booklets, delivered during preoperative education sessions, or communicated via online videos. Within these mediums, information is given regarding a range of topics, such as the background to osteoarthritis or low back pain, the technical details of the operation, when to stop routine medications, and what to expect from the hospital stay.1 However, apart from fasting guidelines before admission, it is the opinion of the authors that very poor technical information on healthy eating choices is provided. This is at a point when patients may be more responsive and motivated than at other times to optimize lifestyle factors, such as diet. The prevalence of orthopedic patients reporting sub-optimal intakes ranges from 50 to 91.5% in the perioperative period.2–4 As we become aware of the critical role of improving lifestyle choices for everyday health but also for recovery from surgery,5–7 it is relevant both to patient experience and care quality to integrate the journey towards surgery with the dietary notions that help to fulfill the needs of energy, nutrients, and fluids. A healthy diet is, in fact, a prerequisite for the effective application of nutritional optimization methodologies that should be applied only to patients who already meet their metabolic requirements. To inform patients, and to remind healthcare professionals of what is meant by healthy eating, the technical concepts relating to food and nutrition must be translated into terms of common use avoiding simplification of knowledge and ambiguity.8 The educational component should promote patient self-management,9 using practical examples to help clear the general notions.

In view of sustaining the nutritional requirements before surgery and during rehabilitation, our goal is to bring together the principles of healthy eating into the perioperative practices for patients undergoing elective major orthopedic surgery as a starting point for designing successful nutritional optimization strategies. In order to do this, educating health professionals is the first step, and our intention with this work is to describe a practical and usable categorization of foods based on the nutritional intent, to which the general concepts of quantity, quality, food timing, and preoperative eating can be integrated with effectiveness.

The Principles of Healthy Eating

Nutritional Use

Food can be categorized according to different properties, such as the origin (animal or plant-based), processing (whole or refined), acid-base load, glycemic index, or antioxidant capacity.10 The classification based on the main nutritional value lets us distinguish five groups of foods: starchy carbohydrates, the five sources of proteins, fats (oils and spreads), micronutrient-rich fruits, and fiber-rich greens and vegetables. It is essential to inform patients about these distinctions to transcend local misconceptions or culinary customs that might in the long run unbalance the diet.11,12 Although tubers are vegetables, they are to be considered as an alternative to cereals and derivatives and therefore as a primary energy source (Table 1). Although green beans are legumes, they are not to be considered a source of protein but as low-protein vegetables, having an edible pod and high-water seeds. Essentially, each meal must be based on cereals, derivatives, or tubers together with a source of proteins, fats, and fiber. It may be useful to suggest patients introduce certain food categories only at certain moments of the day to aid equal distribution of energy and macromolecules. Fresh fruit, nuts, low-salt low-sugar baked goods, or yogurt are ideal snacks in mid-morning and mid-afternoon.13 Although the guidelines or suggestions regarding healthy eating habits have long been around as a means of disease prevention and quality of life improvement, they are not consistently followed by patients or applied by institutions.14 Moreover, it is not uncommon that some patients often wish to turn to plant-based products or exotic foods assumed to be ethically superior or healthier.15 Most of these foodstuffs hardly find a place in the daily diet because they deviate from the nutritional criteria that recognize the five food groups, thus misleading even the most attentive patient. Examples are the plant-based alternatives of milk (eg, oat milk), the flours from legumes (eg, chickpea flour), oily fresh fruits (eg, avocado), soy products (eg, tofu, tempeh), or sea vegetables (eg, algae). Although these foods might not be a wrong health choice, patients should be advised that it is first of all important to know how to integrate the distinct five food groups into the usual diet.

Table 1.

Categorizations of Foods Based on the Primary Nutritional Function and Tips on How to Consume Standard Portions

| Primary Nutritional Use | Major Food Groups | Food Products | Examples | Portion* g (Edible, Drained) | Primary Cooking Techniques | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrates: energy | Cereals and derivatives | Wheat products | Pasta, cous-cous, semolina | 80 | Boiling | To be preferred in this food group; from wholegrains |

| Grains | Rice, barley, spelled | 80 | Boiling | To be preferred in this food group; from wholegrains | ||

| Salty baked goods (soft) | Durum wheat bread, rye bread | 50 | Ready-to-eat | Prefer wholegrains; might contain too much salt | ||

| Salty baked goods (hard) | Rusks, bread sticks, crackers, taralli | 30 | Ready-to-eat | Prefer wholegrains; might contain too much salt | ||

| Sweet baked goods (soft) | Brioche, croissant | 50 | Ready-to-eat | Might contain seasoning fat and too many sugars | ||

| Sweet baked goods (hard) | Biscuits, breakfast cereals | 30 | Ready-to-eat | Prefer wholegrains; might contain seasoning fat/sugars | ||

| Tubers | Tubers (raw) | Potato, yam, sweet potato | 200 | Boiling, baking | Avoid frying or excessive salting | |

| Proteins: structure, micronutrients | Milk | Milk | Cow milk, goat milk | 150 | Ready-to-eat | To be preferred in this food group; prefer the skimmed |

| Dairy products | Yogurt | Cow’s milk yogurt | 150 | Ready-to-eat | To be preferred in this food group; avoid added sugars | |

| Cheese (fresh) | Mozzarella, stracchino | 100 | Ready-to-eat | Prefer the low-fat or fat free | ||

| Cheese (aged, soft) | Blue cheese, camembert | 100 | Ready-to-eat | Might contain a lot of salt | ||

| Cheese (aged, hard) | Cheddar, parmesan, grana padano, pecorino | 50 | Ready-to-eat | Might contain a lot of salt | ||

| Meat | White meat (fresh) | Chicken, turkey, other birds, rabbit | 100 | Pan broiling, roasting | To be preferred in this food group; avoid chargrill/panfrying | |

| Red meat (fresh) | Beef, sheep, hog, horse, deer | 100 | Pan broiling, roasting | Avoid chargrill/panfrying | ||

| Cold cuts, cured | Ham, salami, bresaola, mortadella | 50 | Raw | Might contain a lot of salt | ||

| Seafood | Fish, mollusks, crustaceans (fresh) | Turbot, swordfish, mackerel, prawns, shrimps, mussels | 150 | Sautéing, baking, poaching | To be preferred in this food group | |

| Fish (preserved) | Tuna, salmon, cod | 50 | Ready-to-eat | Avoid preservations in oil or brine | ||

| Egg | Egg | Chicken egg, duck egg | 50 | Soft boiling, poaching | The white is the protein part; the yolk is the fat part | |

| Legumes | Legumes (fresh or canned) | Beans, lentils, soy, chickpeas, peas | 150 | Ready-to-eat, boiling | To be preferred in this food group | |

| Legumes (dried) | Beans, lentils, soy, chickpeas, peas | 50 | Soaking-boiling | Cook in salty water to lower nutrient loss | ||

| Lipids: energy | Seasoning fats | Oily fruits | Olive oil | 10 | Ready-to-eat | To be preferred in this food group; source of unsaturated fats |

| Oily fruits | Coconut oil, palm oil | 10 | Ready-to-eat | Source of saturated fats | ||

| Animal fats | Butter, lard | 10 | ready-to-eat | Source of saturated fats | ||

| Fruit | Fruits (dried in shell) | Walnuts, hazelnuts, almonds, cashews, pine/Brazil nuts | 30 | Raw | To be preferred in this food group; very caloric | |

| Oily seeds | Sunflower seeds, sesame seeds, pumpkin seeds | 30 | Raw | To be preferred in this food group; very caloric | ||

| Carbohydrates: fiber, micronutrients | Greens and vegetables | Leafy greens | Lettuce, spinach, chard, kale | 80 | Raw, boiling | Avoid lengthy cooking; cook in salty water to lower nutrient loss |

| Vegetables | Tomato, carrot, aubergine, broccoli, zucchinis | 200 | Raw, steaming, boiling, baking | Avoid lengthy cooking; cook in salty water to lower nutrient loss | ||

| Legumes | Beans (in edible pods) | Green beans | 200 | Steaming, boiling, stewing | Do not remove the pots if edible | |

| Fungi | Mushrooms | White button, shiitake, porcini | 200 | Steaming, poaching | Avoid panfrying or excessive roasting | |

| Carbohydrates: fiber, micronutrients | Fruits | Fruits (fresh) | Apple, pear, orange, apricots, banana, peach, berries | 150 | Raw | Avoid juice machines that remove the fiber |

| Fruits (dehydrated) | Dates, raisins, prunes, apricots | 30 | Raw | Contain high concentration of sugar | ||

| Flavoring | Plants and products | Aromatic herbs (fresh) | Basil, parsley, oregano, chives, sage, rosemary, coriander | Quantum satis | Blanching | Used as seasonings in place of salt and fatty seasonings |

| Spice seeds (dried) | Anise, cumin, fennel, poppy, sesame | Quantum satis | Raw, blanching | Used as seasonings in place of salt fatty seasonings | ||

| Spices (dried) | Pepper, chili peppers, ginger, cardamom, cinnamon, cloves | Quantum satis | Raw, stewing | Used as seasonings in place of salt and fatty seasonings | ||

| Vegetables (fresh) | Onion, garlic | Quantum satis | Poaching, stewing | Prefer the cooking in little water in place of oil; avoid frying |

Notes: *The standard portion is defined as the quantity of food that is assumed to be an accepted reference unit by health professionals, an amount easily identifiable, and a serving that meets the consumer’s expectations. The standard portion must be adapted in the case of a personalized diet.

Food Quantity

The concept of food quantity encompasses the daily, weekly, and seasonal requirements together with the portion size. Meeting daily needs is essential for the maintenance of a good nutritional status.16 Different quantitative dietary reference values (DRV) are used by the European Food Safety Authority to issue dietary recommendations, such as the average requirement (AR) of healthy individuals, the population reference intake (PRI) for most healthy people, the adequate intake (AI) when AR is not available, and the reference intake (RI) for macronutrients.17 The healthy eating instructions for preoperative education should feasibly adhere to these dietary standards as well as consider that distinct daily values are recommended in older and surgical populations.18 In the context of orthopedic surgery, we can consider appropriate requirement energy of 27–30 kcal and 1.2–1.5 grams of proteins per kg of body weight.19,20 The abovementioned categorization of foods based on the primary nutritional function allows the definition of quantitative standardized portions since similar amounts of macronutrients are provided by food products of the same group, with water content being the main determinant of weight variation. For instance, about 50 kcal is provided either by 80 g of banana or 350 g of watermelon. The healthy portioning may be referred to as the commercial serving (eg, canned food) to facilitate patients’ choices. Regularly, certain foods must be consumed more than once a day or a week to fulfill the requirement of certain nutrients. For example, it is recommended to consume at least five portions of a variety of fresh fruit, greens, and vegetables every day. Moreover, the seven lunches and seven dinners per week are suggested to comprise a portion of legumes 3–4 times, seafood 3–4 times, eggs 2 times, dairy products 2 times, and meat 2–3 times.21,22 Requirements depend also on body-environment interactions, and it may be necessary to adapt intakes to unfavorable conditions (eg, increased vitamin D in the less sunny seasons). If there is not enough time prior to surgery, nutrient deficits may be corrected through dietary supplementation after discharge.23,24

Food Quality

Despite being inherently based on quantitative attributes, food quality is the aspect that bestows the “healthy” connotation to a diet.25,26 It combines the refrain from unhealthy food components with the pursuit of nutrient balance. A high-quality diet adheres to the suggested dietary target (SDT) and does not exceed the tolerable upper intake level (UL). The SDT for certain food components like sugars aims at preventing chronic degenerative diseases27 while the UL refers to the maximum intake to be unlikely to pose a risk to health, being useful in case of use of dietary supplements.28 Nutrient balance is ensured if the patient meets the requirements daily, varies the food choices each week, and follows food seasonality. Patients should be taught in reading food labels to choose less processed food and educated in conservation, handling, and cooking techniques. In Table 1 we summarize these concepts. It is important to consider that the nutritional profile of a meal is highly dependent on the way the raw food was stored and cooked, especially as regards the vitamin content. For example, prolonged boiling in unsalted water causes mineral depletion of greens and vegetables.29 Following seasonality and weekly variety is also a means to sustain a healthy diet. Each day and week, the patients should alternate the animal with plant-based protein sources30 as well as vary the consumption of fruits, greens, and vegetables. Practical advice is always the easiest to grasp, such as changing the color of the fruit, green, and vegetables every meal. Each season, the patient should prefer local and seasonal products. It is, in fact, important to recall that food quality depends not only on the geographical location and the season of growth and harvest but also varies according to the subspecies of plants, the cultivar and ecotype, the chemotype, soil and nourishment, environmental impact during plant growth, the weather and climate changes, and the agricultural practices.31,32

Food Timing

Food is a potent “zeitgeber” (time cue), being capable of acting as a circadian time trigger.33 The time to eat a meal, the order of nutrients ingested in the same meal, and the distribution of intakes are to be considered the time variables of feeding. Regardless of the composition and number of meals, patients should be advised to eat at fixed times to avoid circadian misalignments.34 Moreover, meals should be consumed not too close to physical activity or bedtime.35 The decrease in appetite and food intake of aging (ie, geriatric anorexia) may expose older patients to inadequate amounts of food. Greens and vegetables boost meal volume, stomach stretching, gastric mechanoreceptor activation, vagus nerve signaling, and early satiety. Older adults might be instructed to prefer single dishes that combine carbohydrates with proteins, avoiding eating vegetables at the beginning of the meal. Energy intake should be high in the morning to sustain the waking hours, thus progressively being reduced during the day.36 Proteins should be evenly allocated over main meals to provide a steady stream of blood amino acids,37 with this concern being most significant for patients with sarcopenia. The right timing of both energy and protein sources is one of the factors that can in fact positively influence the maintenance of the nitrogen balance.38 Eventually, biochemistry reminds us that the bioavailability of some nutrients varies in the presence of other food components. For example, it is wise to inform patients that the iron in plants is poorly absorbed unless it is consumed with L-ascorbic (eg, freshly squeezed lemon juice should be added).39 These tips can make a difference in patients with age-related malabsorption.40 The timing of food is often conditioned by prescribed medicines, which are to be taken at certain times on a full or empty stomach or at some distance from meals, and by surgical, anesthetic, and nursing practices. In time, it is important that any dietary advice, albeit generalist, is always comprising detailed instructions for what concerns the last dinner before surgery and the eating behaviors on the day of admission.

Healthy Eating Prior to Orthopedic Surgery

Dietetics is the science that studies the elaboration of diets with common or special foods, the administration of food through tubes connected to gastrointestinal districts, and the supply of nutritional factors via parenteral routes. Nutrition is the science that focuses on the biological processes that allow or condition the growth, development, conservation, and reintegration of physical and energy losses. Considering these disciplines in the context of major orthopedic surgery, eating through diet is the determining condition of a balanced nutritional status, which is a set of measurable parameters related to health, performance, and consequently the suitability for surgery. It is not uncommon for the patient to ask what the most appropriate food is to eat in preparation for surgery, when should the last meal be, or if any dietary supplements may be of use for a better recovery. In building a healthy eating strategy, it is primarily important to convey the concepts of quantity, quality, and timing of food, possibly through a standard dietary plan contingent on the technical skills of the perioperative team in order to simplify the integration of theoretical concepts into the patient’s everyday routine. Subsequently, it is vital to give specific indications for the day of surgery for what concerns eating and drinking practices. Current enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) guidelines do not specify what is meant by “6-hour fast for solid food” or what “clear fluids” are allowed until 2 hours before the induction of anesthesia.41,42 The last meal could be the dinner of the day before if the surgery is early in the morning, breakfast if the surgery is late in the morning, or lunch if surgery is in the late afternoon. We argue that the last meal should be light, generally lighter than usual, conceivably consisting of a source of complex carbohydrates and proteins, such as an egg with bread or yogurt with cereals and fruit. It is also reasonable to recommend that a glass of water should be preferred, but it is also possible to drink a glass of fresh juice extracted (pulp-free) from a maximum of 50 g of fruit or vegetables.43 Another aspect worth discussing with the patient in the context of surgical preparation is the use of dietary supplements, for which there are limited evidences associating their use with reduced length of stay and accelerated return to functional mobility.44 Although not pertinent to our argument, we can reasonably assume that most patients do not require supplements if they follow a healthy and balanced diet before and after surgery. Their use must in fact be limited to malnourished patients or when there is not enough time to correct the deficits through dietary strategies. In addition, some food components found in dietary supplements are known to interact with medications, hence affecting the therapeutic efficacy.45 Therefore, we suggest abstention rather than improper use or use with no purpose. On the day of surgery, it is reasonable to schedule that at least one meal might be skipped and to plan the time for oral refeeding accordingly to ensure a functional stream of energy and protein. On the one hand, it is imperative to resume oral feeding as soon as possible but, on the other hand, it is not prudent to provide meals that require long digestion times. In the absence of postoperative diets planned by the dietetic unit, water balance and high caloric density meals in small volumes should be favored. If no complications arose, it may be possible to resume normal feeding 4 hours after surgery.46 We suggest that patients continue to follow healthy eating indications after the operation in order to balance the nutritional needs during the rehabilitation process and, most likely, for good health in later life. In fact, it is not uncommon for patients to experience a loss of weight or lean mass after orthopedic surgery,47 which might accelerate the natural physical decline observed early in subjects with frailty.4,35

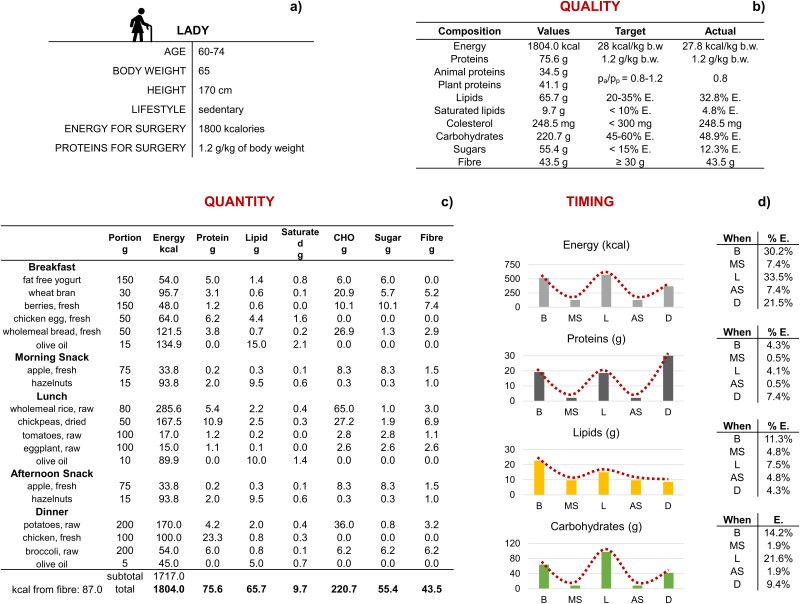

In Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure 1, we have reported two exemplary healthy eating plans for a lady and a man, respectively, to guide health professionals toward the applicability of the basic food principles. One way to summarize the patients’ needs, answer the questions, help the transitioning from hospital to home, and anticipate the barriers of the first days after discharge is the use of an information booklet (Supplementary Material), whose acceptability and effectiveness should be evaluated with quality-improvement initiatives. Of note, dietary counseling combined with exercise therapy in the context of prehabilitation48 and postoperative rehabilitation49 of orthopedic patients could reveal the most satisfactory outcomes.

Figure 1.

Exemplary healthy eating calculations for a lady candidate for major orthopedic surgery.

Notes: (a) Parameters to be considered for setting a dietary plan in a lady between 60 and 74 years of age, body weight of 65 kg, height of 170 cm, sedentary lifestyle, daily energy requirement in preparation for surgery 1800 kcal, and protein 1.2 g/kg of body weight. (b) Qualitative values of the dietary plan. (c) Composition of a daily plan that comprises three main meals (breakfast, lunch, dinner) and two snacks (morning and afternoon). Energy per gram of food component = 4 kcal for proteins, 9 kcal for lipids, 4 kcal for carbohydrates, and 2 kcal for fiber. (d) Histograms showing the daily trends for energy (kcal), protein (g), lipid (g), and carbohydrate (g) intakes at breakfast (B), morning snack (MS), lunch (L), afternoon snack (AS), and dinner (D). The tables report the energy intakes at each meal and the energetic contribution of the three macromolecules.

Conclusion

In summary, the hospitalization of patients undergoing elective hip, knee, and spine surgery is short, with perioperative processes focusing on the principles of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS). There is a growing interest in prehabilitation techniques, and nutrition is one of the three pillars of this concept. There is a clinical acknowledgement that the promotion of healthy eating should be championed by all members of the multidisciplinary team along with the fact that patients who follow a healthy diet are more likely to have an enhanced recovery than patients who eat poorly. Whilst not unreasonable, there is currently no evidence to sustain this argument. Nevertheless, we should take advantage of the teachable moment from the contemplation of surgery to admission. Scheduling a patient for major elective surgery can take place weeks or months in advance and health eating education should be part of the preparation. The sooner patients start to eat healthily in view of surgery the better, and following the same indications after discharge should not have a deadline. In teaching patients about healthy eating, dietitians are able to easily fill this educational role, providing expert advice that adheres to the dietary reference values and is based on our proposed key principles of healthy eating that apply for the orthopedic patient. These include eating a variety of food from all healthy food groups (Table 1), choosing whole, unprocessed products whenever possible, and drinking plenty of water (Supplementary Figure 2). In this article, the eating plans have been designed to ensure optimal amounts of proteins and calories, mainly referring to the foods used in the cuisines of Italy and England. Nevertheless, different countries and ethnicities could mean different cultural heritages. Should the healthy eating indications integrated into perioperative medicine practices of major elective orthopedic surgery be one for all? Probably not, and it will therefore be the task of future clinicians and researchers to investigate ways of integrating evidence-based dietary indications that have external validity and respect the food diversity.

Healthy eating is not to be confused with the nutritional optimization strategies advocating optimal bodily reservoirs through intakes greater than the requirements but beneficial to the patient’s health in view of or under particular circumstances. Nutritional optimization should, in fact, be applied to manage perioperative malnutrition,50 which refers to any balance deviation including excess (eg, obesity) and insufficiency (eg, anemia) factors associated with poor outcomes.51 Diet therapy as part of the preoperative conditioning process is a valid add-on for specific patients.52,53 Conversely, by following our simple guidelines on healthy eating, the entire surgical population is likely to benefit, especially in terms of getting fit for surgery, long-term patient satisfaction, and positive impact on both quality-adjusted life years and economic indicators in health care.54–58 The accomplishment of future preoperative education might need pioneering dissemination methods,59 thus exploiting different approaches as in fact occurs for what concerns the management of anxiety60 or physical activity to practice.61

Funding Statement

This research was part of the project “Ricerca Corrente” of the Italian Ministry of Health, which funded the APC.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.(UK) NGC. Evidence review for preoperative rehabilitation: joint replacement (primary): hip, knee and shoulder: evidence review C; 2020. [PubMed]

- 2.Miyoba N, Ogada I, Mulenga J. Dietary adequacy of adult surgical orthopaedic patients admitted to a teaching hospital in Zambia; a hospital-based cross-sectional study. BMC Nutr. 2018;4:37. doi: 10.1186/s40795-018-0245-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Purcell S, Thornberry R, Elliott SA, et al. Body composition, strength, and dietary intake of patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2016;77(2):98–102. doi: 10.3148/cjdpr-2015-037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Briguglio M, Gianola S, Ismael Aguirre M, et al. Nutritional support for enhanced recovery programs in orthopedics: future perspectives for implementing clinical practice. Nutr Clin Metab. 2019;33(3):190–198. doi: 10.1016/j.nupar.2019.04.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bongers BC, Dejong CHC, den Dulk M. Enhanced recovery after surgery programmes in older patients undergoing hepatopancreatobiliary surgery: what benefits might prehabilitation have? Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021;47(3 Pt A):551–559. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2020.03.211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dahlberg K, Bylund A, Stenberg E, Jaensson M. An endeavour for change and self-efficacy in transition: patient perspectives on postoperative recovery after bariatric surgery-a qualitative study. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-Being. 2022;17(1):2050458. doi: 10.1080/17482631.2022.2050458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mancuso CA, Rigaud MC, Wellington B, et al. Qualitative assessment of patients’ perspectives and willingness to improve healthy lifestyle physical activity after lumbar surgery. Eur Spine J. 2021;30(1):200–207. doi: 10.1007/s00586-020-06508-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sosis MB, Loberg KW, Pandit UA. Coffee is not a clear liquid. Anesth Analg. 2000;91(5):1308–1309. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200011000-00053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veronovici NR, Lasiuk GC, Rempel GR, Norris CM. Discharge education to promote self-management following cardiovascular surgery: an integrative review. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2014;13(1):22–31. doi: 10.1177/1474515113504863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ronald LP. Oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC): new horizons in relating dietary antioxidants/bioactives and health benefits. J Funct Foods. 2015;18:797–810. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2014.12.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sproesser G, Ruby MB, Arbit N, et al. Understanding traditional and modern eating: the TEP10 framework. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1606. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7844-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramírez AS, Golash-Boza T, Unger JB, Baezconde-Garbanati L. Questioning the dietary acculturation paradox: a mixed-methods study of the relationship between food and ethnic identity in a Group of Mexican-American women. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018;118(3):431–439. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2017.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Potter M, Vlassopoulos A, Lehmann U. Snacking recommendations worldwide: a scoping review. Adv Nutr. 2018;9(2):86–98. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmx003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leme ACB, Hou S, Fisberg RM, Fisberg M, Haines J. Adherence to food-based dietary guidelines: a systemic review of high-income and low- and middle-income countries. Nutrients. 2021;13(3):1038. doi: 10.3390/nu13031038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tuorila H, Hartmann C. Consumer responses to novel and unfamiliar foods. Curr Opin Food Sci. 2020;33:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cofs.2019.09.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asamane EA, Greig CA, Thompson JL. The association between nutrient intake, nutritional status and physical function of community-dwelling ethnically diverse older adults. BMC Nutr. 2020;6:36. doi: 10.1186/s40795-020-00363-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.EFSA. Dietary reference values for the EU. DRV Finder. Available from: https://multimedia.efsa.europa.eu/drvs/index.htm. Accessed July 17, 2023.

- 18.Campbell WW, Trappe TA, Wolfe RR, Evans WJ. The recommended dietary allowance for protein may not be adequate for older people to maintain skeletal muscle. J Gerontol a Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(6):M373–80. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.6.m373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Volkert D, Beck AM, Cederholm T, et al. ESPEN practical guideline: clinical nutrition and hydration in geriatrics. Clin Nutr. 2022;41(4):958–989. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2022.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weimann A, Braga M, Carli F, et al. ESPEN practical guideline: clinical nutrition in surgery. Clin Nutr. 2021;40(7):4745–4761. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2021.03.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Italian Ministry of Health. Linee Guida per una Sana Alimentazione Italiana - Revisione 2018; 2019.

- 22.The Scottish Government. Eat well - A guide for older people in Scotland; 2020.

- 23.Briguglio M, Gianturco L, Stella D, et al. Correction of hypovitaminosis D improved global longitudinal strain earlier than left ventricular ejection fraction in cardiovascular older adults after orthopaedic surgery. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2018;15(8):519–522. doi: 10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2018.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirsch KR, Wolfe RR, Ferrando AA. Pre- and Post-surgical nutrition for preservation of muscle mass, strength, and functionality following orthopedic surgery. Nutrients. 2021;13(5):1675. doi: 10.3390/nu13051675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freeland-Graves JH, Nitzke S; Dietetics AoNa. Position of the academy of nutrition and dietetics: total diet approach to healthy eating. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113(2):307–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Echouffo-Tcheugui JB, Ahima RS. Does diet quality or nutrient quantity contribute more to health? J Clin Invest. 2019;129(10):3969–3970. doi: 10.1172/JCI131449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moshtaghian H, Louie JC, Charlton KE, et al. Added sugar intake that exceeds current recommendations is associated with nutrient dilution in older Australians. Nutrition. 2016;32(9):937–942. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2016.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turck D, Bohn T, Castenmiller J, et al. Guidance for establishing and applying tolerable upper intake levels for vitamins and essential minerals: draft for internal testing. EFSA J. 2022;20(1):e200102. doi: 10.2903/j.efsa.2022.e200102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kimura M, Itokawa Y. Cooking losses of minerals in foods and its nutritional significance. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol. 1990;36:S25–32. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.36.4-SupplementI_S25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang J, Liao LM, Weinstein SJ, Sinha R, Graubard BI, Albanes D. Association between plant and animal protein intake and overall and cause-specific mortality. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(9):1173–1184. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Worthington V. Effect of agricultural methods on nutritional quality: a comparison of organic with conventional crops. Altern Ther Health Med. 1998;4(1):58–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Montgomery DR, Biklé A, Archuleta R, Brown P, Jordan J. Soil health and nutrient density: preliminary comparison of regenerative and conventional farming. PeerJ. 2022;10:e12848. doi: 10.7717/peerj.12848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stephan FK. The “other” circadian system: food as a Zeitgeber. J Biol Rhythms. 2002;17(4):284–292. doi: 10.1177/074873040201700402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wehrens SMT, Christou S, Isherwood C, et al. Meal timing regulates the human circadian system. Curr Biol. 2017;27(12):1768–1775.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2017.04.059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Briguglio M. The burdens of orthopedic patients and the value of the HEPAS approach (healthy eating, physical activity, and sleep hygiene). Front Med. 2021;8:650947. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.650947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davis R, Rogers M, Coates AM, Leung GKW, Bonham MP. The impact of meal timing on risk of weight gain and development of obesity: a review of the current evidence and opportunities for dietary intervention. Curr Diab Rep. 2022;22(4):147–155. doi: 10.1007/s11892-022-01457-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paddon-Jones D, Rasmussen BB. Dietary protein recommendations and the prevention of sarcopenia. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2009;12(1):86–90. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32831cef8b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jordan LY, Melanson EL, Melby CL, Hickey MS, Miller BF. Nitrogen balance in older individuals in energy balance depends on timing of protein intake. J Gerontol a Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65(10):1068–1076. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Briguglio M, Hrelia S, Malaguti M, et al. Oral Supplementation with sucrosomial ferric pyrophosphate plus L-ascorbic acid to ameliorate the martial status: a randomized controlled trial. Nutrients. 2020;12(2):386. doi: 10.3390/nu12020386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Russell RM. Factors in aging that effect the bioavailability of nutrients. J Nutr. 2001;131(4 Suppl):1359S–61S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.4.1359S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wainwright TW. Consensus statement for perioperative care in total Hip replacement and total knee replacement surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society recommendations. Acta Orthop. 2020;91(3):363. doi: 10.1080/17453674.2020.1724674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Debono B, Wainwright TW, Wang MY, et al. Consensus statement for perioperative care in lumbar spinal fusion: enHanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society recommendations. Spine J. 2021;21(5):729–752. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2021.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Briguglio M, Wainwright TW, Crespi T, et al. Oral hydration before and after hip replacement: the notion behind every action. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2022;13:21514593221138665. doi: 10.1177/21514593221138665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burgess LC, Phillips SM, Wainwright TW. What Is the role of nutritional supplements in support of total hip replacement and total knee replacement surgeries? A systematic review. Nutrients. 2018;10(7):820. doi: 10.3390/nu10070820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Briguglio M, Hrelia S, Malaguti M, et al. Food bioactive compounds and their interference in drug pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic profiles. Pharmaceutics. 2018;10(4):277. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics10040277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim J-W, Park Y-G, Kim J-H, Jang E-C, Ha Y-C. The optimal time of postoperative feeding after total hip arthroplasty: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Clinical Nursing Research. 2020;29(1):31–36. doi: 10.1177/1054773818791078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Briguglio M. Nutritional orthopedics and space nutrition as two sides of the same coin: a scoping review. Nutrients. 2021;13(2):483. doi: 10.3390/nu13020483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Briguglio M, Wainwright TW. Nutritional and Physical Prehabilitation in Elective Orthopedic Surgery: rationale and Proposal for Implementation. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2022;18:21–30. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S341953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Musumeci G, Mobasheri A, Trovato FM, Szychlinska MA, Imbesi R, Castrogiovanni P. Post-operative rehabilitation and nutrition in osteoarthritis. F1000Res. 2014;3:116. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.4178.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williams DGA, Villalta E, Aronson S, et al. Tutorial: development and implementation of a multidisciplinary preoperative nutrition optimization clinic. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2020;44(7):1185–1196. doi: 10.1002/jpen.1824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wall C, de Steiger R. Pre-operative optimisation for hip and knee arthroplasty: minimise risk and maximise recovery. Aust J Gen Pract. 2020;49(11):710–714. doi: 10.31128/AJGP-05-20-5436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Drost JM, Cook CB, Spangehl MJ, Probst NE, Mi L, Trentman TL. A plant-based dietary intervention for preoperative glucose optimization in diabetic patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2022;16(1):150–154. doi: 10.1177/1559827619879073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lingamfelter M, Orozco FR, Beck CN, et al. Nutritional counseling program for morbidly obese patients enables weight optimization for safe total joint arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2020;43(4):e316–e322. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20200521-08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Webb P, Danaei G, Masters WA, et al. Modelling the potential cost-effectiveness of food-based programs to reduce malnutrition. Glob Food Sec. 2021;29:100550. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2021.100550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hugo C, Isenring E, Miller M, Marshall S. Cost-effectiveness of food, supplement and environmental interventions to address malnutrition in residential aged care: a systematic review. Age Ageing. 2018;47(3):356–366. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afx187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mazzei DR, Ademola A, Abbott JH, Sajobi T, Hildebrand K, Marshall DA. Are education, exercise and diet interventions a cost-effective treatment to manage Hip and knee osteoarthritis? A systematic review. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2021;29(4):456–470. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2020.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li D, Liu P, Zhang H, Wang L. The effect of phased written health education combined with healthy diet on the quality of life of patients after heart valve replacement. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2021;16(1):183. doi: 10.1186/s13019-021-01437-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dean S, Al Sayah F, Johnson JA. Measuring value in healthcare from a patients’ perspective. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2021;5(Suppl 2):88. doi: 10.1186/s41687-021-00364-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sharif F, Rahman A, Tonner E, et al. Can technology optimise the pre-operative pathway for elective hip and knee replacement surgery: a qualitative study. Perioper Med. 2020;9(1):33. doi: 10.1186/s13741-020-00166-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang R, Huang X, Wang Y, Akbari M. Non-pharmacologic approaches in preoperative anxiety, a comprehensive review. Front Public Health. 2022;10:854673. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.854673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Steffens D, Delbaere K, Young J, Solomon M, Denehy L. Evidence on technology-driven preoperative exercise interventions: are we there yet? Br J Anaesth. 2020;125(5):646–649. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.06.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]