Abstract

The Bacillus anthracis Sterne plasmid pXO1 was sequenced by random, “shotgun” cloning. A circular sequence of 181,654 bp was generated. One hundred forty-three open reading frames (ORFs) were predicted using GeneMark and GeneMark.hmm, comprising only 61% (110,817 bp) of the pXO1 DNA sequence. The overall guanine-plus-cytosine content of the plasmid is 32.5%. The most recognizable feature of the plasmid is a “pathogenicity island,” defined by a 44.8-kb region that is bordered by inverted IS1627 elements at each end. This region contains the three toxin genes (cya, lef, and pagA), regulatory elements controlling the toxin genes, three germination response genes, and 19 additional ORFs. Nearly 70% of the ORFs on pXO1 do not have significant similarity to sequences available in open databases. Absent from the pXO1 sequence are homologs to genes that are typically required to drive theta replication and to maintain stability of large plasmids in Bacillus spp. Among the ORFs with a high degree of similarity to known sequences are a collection of putative transposases, resolvases, and integrases, suggesting an evolution involving lateral movement of DNA among species. Among the remaining ORFs, there are three sequences that may encode enzymes responsible for the synthesis of a polysaccharide capsule usually associated with serotype-specific virulent streptococci.

Anthrax, a disease of herbivores and other mammals, including humans, is caused by Bacillus anthracis, a gram-positive, rod-shaped, nonmotile, spore-forming bacterium. Virulence of most B. anthracis strains is associated with two megaplasmids, and strains lacking either plasmid are either avirulent or significantly attenuated. Plasmid pXO2 (60 MDa) carries genes required for the synthesis of an antiphagocytic poly-d-glutamic acid capsule (24, 37, 48, 60, 63, 64). The 110-MDa plasmid pXO1 (61) is required for synthesis of the anthrax toxin proteins, edema factor, lethal factor, and protective antigen. These proteins act in binary combinations to produce the two anthrax toxins: edema toxin (a protective antigen and edema factor) and lethal toxin (a protective antigen and lethal factor) (reviewed in references 41 and 42).

Despite the important roles of pXO1 and pXO2 in B. anthracis virulence, few plasmid-encoded genes have been identified and characterized. Plasmid pXO2 carries three genes required for capsule synthesis (capB, capC, and capA), a gene associated with capsule degradation (dep), and a trans-acting regulatory gene (acpA) (24, 48, 63, 64). Plasmid pXO1 harbors the structural genes for the anthrax toxin proteins [cya (edema factor), lef (lethal factor), and pagA (protective antigen)], as well as two trans-acting regulatory genes (atxA and pagR), a gene encoding a type I topoisomerase (topA), and a recently characterized operon containing three genes whose functions appear to affect germination (12, 21, 26, 31, 38, 50, 55, 62, 65). In addition to the Tox+ phenotype, a number of other phenotypes have been associated with pXO1. pXO1-cured strains exhibit different nutritional requirements on certain minimal media, display enhanced sporulation, and demonstrate altered phage sensitivity compared to pXO1+ strains (57).

Here we report the sequencing, assembly, and annotation of pXO1. Our analysis indicates that this plasmid has the potential to encode 143 proteins. The virulence genes of pXO1 are organized in a manner similar to pathogenicity islands (PAIs) located on the chromosomes of other bacterial pathogens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid DNA isolation.

The Sterne strain of B. anthracis is pXO1+ pXO2− (50, 56). Plasmid pXO1, isolated and purified from this strain, was kindly provided by Donald Robertson (Department of Chemistry, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah). The protocol for purification and analysis of pXO1 has been described (34).

DNA sequencing.

The sequencing strategy used to assemble the complete plasmid was based on the whole-genome, shotgun approach that has been successfully applied to the sequencing and assembly of several much larger microbial genomes (for an example, see reference 20) and a number of microbial plasmids (18, 23). A small-insert random-fragment library was generated from pXO1 DNA using the following conventional approach. Plasmid DNA was sonicated and size fractionated. Small (2- to 4-kb) DNA fragments were digested with mung bean nuclease to create blunt ends and then ligated into the EcoRV site of Escherichia coli plasmid pT7-Blue (Novagen). Recombinant plasmid DNA was transformed into E. coli DH10B (Life Technologies, Madison, Wis.) by electroporation. Overnight cultures of individual pT7-Blue clones (2 ml) were purified using a 96-well format DNA purification kit (PERFECTprep-96; 5 Prime-3 Prime, Inc., Boulder, Colo.).

Sequences were generated using dye-terminator chemistry (ABI Prism FS; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) driven by two pT7-Blue-specific primers complementary to sequences flanking the inserts. Sequencing reactions were analyzed on 36- or 48-cm polyacrylamide gels (4% Burst-Pak custom gel; Owl Scientific, Portsmouth, N.H.) or 5% Long Ranger gels (FMC, Rockland, Maine) using ABI 373 or 377 DNA sequencers (Applied Biosystems).

Sequence assembly and closure.

Sequences from randomly selected clones were assembled and edited on an Apple Power Macintosh computer using Sequencher (Gene Codes, Ann Arbor, Mich.). An initial assembly generated ∼40 contigs containing both sequence and physical gaps. The sequence gaps were closed primarily by direct walking off of appropriate clones to generate eight contigs containing approximately 180 kb of sequence. The final physical gaps were closed by generating reverse primers to the ends of each contig and systematically linking physical gaps by PCR analysis. A previously constructed pXO1 restriction map (54) was also used to establish appropriate primer pairs. The PCR products were purified with QIAquick PCR Purification Kits (Qiagen, Santa Clarita, Calif.) and sequenced using the protocols outlined above.

Locating open reading frames (ORFs).

GeneMark (6) and GeneMark.hmm (43) software programs were used to predict the location of gene boundaries in the pXO1 sequence. GeneMark.hmm uses a specially designed postprocessing ribosome-binding site prediction tool that was modified for a Bacillus subtilis matrix. It considers the lack of the ribosomal protein S1 within the bacilli and the requirement to identify ribosome-binding sites with elevated binding affinities (43). The BLAST and FASTA programs were used to conduct similarity searches against GenBank, EMBL, and Swiss-Prot sequence databases. ScanProsite was used to identify patterns within the Prosite database.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The complete circular plasmid sequence was entered into GenBank under accession no. AF065404.

RESULTS

Overall features.

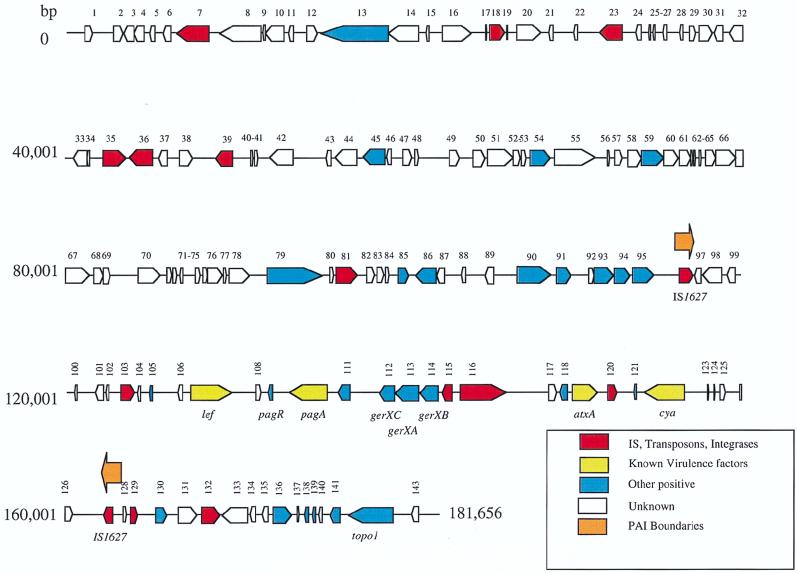

The Sterne strain of B. anthracis harbors a circular pXO1 plasmid that is 181,654 bp in length with an overall guanine-plus-cytosine content of 32.5%. A total of 143 ORFs were identified using GeneMark and GeneMark.hmm (Fig. 1). BLAST surveys showed that the majority (97) of these ORFs appear to encode proteins of unknown function. Eleven ORFs are predicted to encode proteins with similarity to hypothetical proteins from other organisms (Table 1). Putative functions could be assigned to only 35 ORFs that had significant similarity to proteins of other organisms.

FIG. 1.

Predicted pXO1 ORFs and physical map. The positions of ORFs predicted by GeneMark.hmm are illustrated as arrows along the 181,654-bp circular pXO1 plasmid. The precise start and stop for each predicted ORF and the most likely ribosome binding site are listed in features of pXO1 under GenBank accession no. AF065404. The direction of the arrows indicates the direction of transcription in each ORF relative to all the other ORFs. The gene map illustrates the position of the known toxin genes and the IS1627 elements and shows the relationship of the PAI to the remainder of the pXO1 sequence.

TABLE 1.

Putative and characterized pXO1 genes and their functionsa

| ORF | Start site | Stop site | Strand | Size (aa) | Gene product (size) and type; organism of origin (accession no.); and similarity to pXO1 or other relevant characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 07 | 6544 | 8190 | − | 548 | Reverse transcriptase (574 aa), IS629; E. coli (AB11549); 306/543 aa positive (56%) |

| 13 | 15040 | 19002 | − | 1,320 | Erythrocyte invasion/rhoptry protein (2,401 aa); P. yoelii (U36927); 520/1194 aa positive (43%) |

| 18 | 25124 | 26071 | + | 315 | Integrase/recombinase protein (311 aa); M. thermoautotrophicum (AE000865); 97/208 aa positive (46%) |

| 23 | 31621 | 33006 | − | 461 | Potential coding region (609 aa); Clostridium difficile (X98606); 249/390 aa positive (63%); also similar to maturase-related protein from Pseudomonas alcaligenes; gene not predicted by GeneMark.hmm |

| 35 | 42103 | 43539 | + | 478 | Transposase (478 aa), IS231E; B. thuringiensis (Q02403); 455/478 aa positive (95%) |

| 36 | 43808 | 45262 | − | 484 | Transposase (478 aa), IS231E; B. thuringiensis (Q02403); 347/468 aa positive (74%) |

| 39 | 48912 | 49889 | − | 325 | Transposase (478 aa), IS231E; B. thuringiensis (Q02403); 282/299 aa positive (94%) |

| 45 | 57659 | 58966 | − | 435 | Cell division protein (372 aa), ftsZ; P. horikoshii (AP000001); 103/213 aa positive (48%) |

| 54 | 67634 | 68815 | + | 393 | S-layer precursor/surface layer protein (814 aa); B. anthracis (P49051); 162/353 aa positive (45%) (limited to SLH domains) |

| 59 | 74068 | 75501 | + | 477 | Secretory protein kinase (474 aa), kln; C. limicola (U77780); 166/310 aa positive (53%); also similar to B. pertussis 339-aa VirB11 gene product |

| 79 | 91443 | 95111 | + | 1,222 | Hypothetical hydrophobic protein (567 aa); Bacillus firmus (U64515); 127/269 aa positive (47%) |

| 81 | 95978 | 97363 | + | 461 | Ras- and transposon-related protein (225 aa), yocA; B. subtilis (AF027868); 90/158 aa positive (56%) |

| 85 | 99636 | 100319 | + | 227 | Hypothetical protein (244 aa), ydiL in bltr-spoIIC intergenic region; B. subtilis (D88802); 109/222 aa positive (49%) |

| 86 | 100777 | 101922 | − | 381 | Hypothetical protein (402 aa), yrkO; B. subtilis (D84432); 199/376 aa positive (52%) |

| 87 | 101962 | 102444 | − | 160 | Unknown function, putative thioredoxin (137 aa), yolI; B. subtilis (Z99115); 55/99 aa positive (55%) |

| 90 | 106772 | 108730 | + | 652 | Hypothetical protein (980 aa), PFB0765w; Plasmodium falciparum (AE001417); 290/599 aa positive (48%) |

| 91 | 109000 | 109842 | + | 280 | Hypothetical protein (193 aa), ywoA in ngrB-spoIIQ intergene region; B. subtilis (P94571); 86/170 aa positive (50%) |

| 93 | 111374 | 112474 | + | 366 | Hyaluronate synthase (419 aa), hasA; Streptococcus pyogenes (L21187); 211/287 aa positive (73%) and 36/48 aa positive (73%) |

| 94 | 112516 | 113403 | + | 296 | UDP-glucose-pyrophosphorylase (292 aa), gtaB; B. subtilis (Q05852); 221/286 aa positive (77%) |

| 95 | 113430 | 114761 | + | 443 | Putative NDP-sugar-dehydrogenase (440 aa), ywqF; B. subtilis (Z99122); 333/434 aa positive (76%) |

| 96 | 116307 | 117131 | + | 274 | Putative transposase for IS1627; plasmid pXO1; B. anthracis Sterne L element (U30714); GeneMark.hmm truncates gene |

| 103 | 123018 | 123971 | + | 317 | Probable integrase/recombinase (296 aa), ripX; B. subtilis (P46352); 93/193 aa positive (48%) |

| 107 | 127442 | 129871 | + | 809 | Anthrax toxin lethal factor, lef; plasmid pXO1; B. anthracis (M29081 and M30210) |

| 109 | 131939 | 132238 | − | 99 | Similar to small DNA binding proteins, pagR; plasmid pXO1, B. anthracis (AF031382) (formerly called tcrA) |

| 110 | 133161 | 135455 | − | 764 | Anthrax toxin protective antigen, pagA, formerly pag; plasmid pXO1; B. anthracis (M22589) |

| 111 | 136229 | 136843 | − | 204 | Hypothetical protein in the protective antigen domain, ypa; plasmid pXO1; B. anthracis (M22589) |

| 112 | 138540 | 139523 | − | 327 | Spore germination response gerXC; plasmid pXO1; B. anthracis (AF108144), similar to gerKC in B. subtilis |

| 113 | 139480 | 140958 | − | 492 | Spore germination response, gerXA; plasmid pXO1; B. anthracis (AF108144), similar to yfkQ, gerBA, and gerAA in B. subtilis |

| 114 | 141002 | 142081 | − | 359 | Spore germination response, gerXB; plasmid pXO1; B. anthracis (AF108144), similar to gerKb in Bacillus subtilis |

| 115 | 142410 | 142991 | − | 193 | Resolvase (191 aa), Tn1546-like; Enterococcus faecium (Q06237); 125/185 aa positive (67%) |

| 116 | 143195 | 146110 | + | 972 | Transposase for TN21 (988 aa), tnpA; E. coli (P13694); 619/916 aa positive (67%) |

| 118 | 149232 | 149684 | − | 150 | Unknown function; plasmid pXO1, B. anthracis (LI3841) |

| 119 | 150042 | 151469 | + | 475 | trans-acting positive regulator, atxA; plasmid pXO1, B. anthracis (L13841) |

| 120 | 152064 | 152636 | + | 190 | Putative transposase (401 aa); S. pyogenes (AF064540); 108/182 aa positive (59%) |

| 121 | 153605 | 153937 | − | 110 | Adenine phosphoribosyl transferase, apt; plasmid pXO1; B. anthracis (AF003936), similar to adenine phosphoribosyl transferase in B. subtilis |

| 122 | 154224 | 156626 | − | 800 | Calmodulin-sensitive adenylate cyclase/edema factor, cya; plasmid pXO1; B. anthracis (M23179 and M24074) |

| 127 | 162232 | 162876 | − | 214 | Putative transposase for IS1627; plasmid pXO1; B. anthracis (U30712) Sterne R element ORF B |

| 129 | 163846 | 164238 | + | 130 | Truncated transposase for IS1627; B. anthracis (U30712); 93/137 aa positive (67%) |

| 130 | 165317 | 166030 | + | 237 | Hypothetical protein (251 aa), yrpE; B. subtilis (U93875); 213/251 aa positive (84%) |

| 132 | 167948 | 169033 | + | 361 | Putative integrase (356 aa); Streptococcus mutans (AF065141); 206/347 aa positive (59%); gene not predicted by GeneMark.hmm |

| 136 | 172285 | 17380 | + | 364 | Response regulator aspartate phosphatase C (383 aa), rapC; B. subtilis (D50453); 126/238 aa positive (52%) and 52/117 aa positive (44%) |

| 137 | 173709 | 173894 | + | 61 | Hypothetical protein similar to host factor protein 1 (68 aa), ymaH; B. subtilis (Z99113); 41/58 aa positive (70%) |

| 138 | 174200 | 174493 | − | 97 | Small DNA binding, pagR-like; B. anthracis (AF031382); 63/98 aa positive (70%) |

| 139 | 174581 | 174871 | − | 96 | Hypothetical protein (138 aa), uvgU; B. subtilis (Z99121); 59/96 aa positive (61%) |

| 141 | 175663 | 176307 | − | 214 | Thermonuclease precursor (TNASE)/micrococcal nuclease (231 aa); S. aureus (P00644); 104/188 aa positive (55%) |

| 142 | 176736 | 179399 | − | 887 | Topoisomerase 1, top1; plasmid pXO1; B. anthracis (M97227) |

Each ORF is defined by a start and stop site and by the size of the protein product. The comment section contains a description of the related protein, its function and the degree of similarity between the pXO1 protein and its relative. Only ORFs which yielded BLAST P-value scores lower than 10−8 are included in this table.

Gene density.

The GeneMark.hmm program predicts that only 110,817 bp of the pXO1 DNA (61%) represents coding regions. The average size of a pXO1 ORF is 610 bp, which is significantly shorter than the average gene size (approximately 1,000 bp) found in most microbial genomes. Other, less-stringent programs that simply separate potentially coding from noncoding regions (e.g., PARSE) indicate that the coding regions may account for as much as 75% of the total pXO1 sequence. The variability in potential coding densities and the shortened average gene size may reflect the presence of nonfunctional gene remnants on the plasmid. These analyses also are consistent with other studies showing a general tendency for plasmids to have larger intergenic spaces (22, 23) than their host microbial genome counterparts, whose gene densities range from 85 to 93% (5, 9, 14, 20, 22, 33, 58).

PAI.

The most notable organizational feature of the pXO1 sequence is a large, 44.8-kb region (coordinates 117177 to 162013) whose ends are flanked by two inverted and nearly identical copies of the IS1627 element (Sterne L and Sterne R, originally identified by J. Hornung and C. Thorne as GenBank entries for ORFs 96 and 127, respectively) (Table 1). We designate this region as a PAI because it contains all of the known toxin genes (cya, lef, and pagA) and toxin regulatory elements (atxA and pagR) (see ORFs 107, 109, 110, 119, and 122 in Table 1). The region also contains several putative insertion elements (ISs) and genes encoding integrases and transposases (see ORFs 103, 115, 116, and 120 in Table 1). The pXO1 PAI is predicted to contain a total of 31 ORFs. Fifteen ORFs are hypothetical genes that are either sequences from other organisms for which putative functions have not been assigned or “new” ORFs that do not have similarity to genes in databases. Included in this category are putative genes (ORFs 111 and 118) that were originally identified during the cloning and sequencing of the pagA and atxA genes (64, 65). One ORF is predicted to encode a protein with significant similarity to adenine phosphoribosyl transferase of E. coli (ORF 121). Three ORFs have significant similarity to spore germination response genes from other bacilli (ORFs 112 through 114) (Table 1) (26). In addition, a noncoding region of the PAI (coordinates 158.0 to 158.3) has sequence similarity to the Bacillus cereus gene encoding hemolysin II.

ISs.

The class of ORFs with the highest overall similarity to known proteins is composed of 15 putative genes that are related to ISs or genes involved in recombination and integration. These include three homologs of the IS231 sequences commonly associated with the Bacillus thuringiensis crystal toxin genes (46). Three iso-IS231 elements were identified within an 8.5-kb region (coordinates 42029 to 50635) and designated IS231R, -S, and -T (Fig. 1 and Table 1, ORFs 35, 36, and 39). While IS231R and IS231S display an apparent integral organization (a 478-amino-acid [aa] putative protein flanked by 20-bp inverted repeat), IS231S is apparently missing its left extremity. Their lengths varied from 1,604 bp for IS231S to 2,066 bp for IS231T. There is remarkable similarity between the IS231 elements from B. anthracis and those isolated from other members of the B. cereus group. The IS231R DNA sequence is 95% identical to that of IS231E from B. thuringiensis serovar finitimus (IS231T shows 97% identity); yet, IS231R is only 63% identical to its coresident element IS231S. Similarly, IS231S is 67% identical to the IS231Y sequence recently isolated from B. cereus (10b).

As described above, a pair of inverted copies of IS-like elements designated IS1627 (GenBank accession no. U30715 and U30713) flank the region of pXO1 that harbors the putative PAI. The IS150-like elements belong to the IS3 family (46). Comparative restriction analysis of this region in the Sterne strain and in the pXO1 plasmids from several other strains, including Weybridge, Weybridge A, and Vollum, indicates that there has been an inversion in this region (57). In Sterne, the two IS1627 elements are separated by 44,836 bp (coordinates 117177 to 162013) and are contained in nearly exactly duplicated sequences of 1,222 and 1,282 bp. These duplications differ by a 68-bp deletion, several single nucleotide additions or deletions, and a small number of nucleotide changes within the sequences adjacent to the ORFs. The two ORFs within these ISs are identical with the exception of a frameshift difference that causes one of the IS-like elements to be 60 aa longer than the other. Neither of these putative ORFs appears to have a strong ribosome binding site and, as a consequence, the GeneMark.hmm program truncates both ORFs to encode polypeptides containing 83 and 143 aa instead of 214 and 274 aa, respectively. A truncated IS1627 putative transposase is also located immediately adjacent to the right end of the inverted region (ORF 129).

Other ORFs with significant similarity to known proteins normally involved in transposition or mobility of DNA include two reverse transcriptase-like proteins from E. coli and Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum, respectively, that are often associated with group II intron self splicing (ORFs 07 and 23); a B. subtilis gene, yocA, whose product is similar to a transposon-related protein (ORF 81); three potential integrases (ORFs 18, 103, and 132); a Tn4430-like element (44, 45) that contains two ORFs (ORFs 115 and 116) corresponding to a resolvase and to transposase tnpA, respectively; and finally a putative transposase at ORF 120. The high proportion of sequences with predicted functions in insertion and recombination is suggestive of plasmid plasticity and the possibility of horizontal exchange of DNA among strains or species.

Origin of replication.

The pXO1 sequence does not contain ORFs with significant homology to any of the rep genes that have previously been associated with origins of replication in large plasmids of gram-positive organisms (3, 4, 7, 8). Robertson et al. (54) attempted to localize the replication origin by cloning pXO1 DNA fragments into an E. coli plasmid and then transforming the plasmid into B. subtilis. Since E. coli plasmids cannot replicate in Bacillus species, any positive transformants would presumably contain the pXO1 replication origin. This strategy produced several clones that mapped to an 11-kb region that lies between coordinates 86249 and 97209 of the pXO1 sequence (Fig. 1). Sequences within these coordinates contain 10 ORFs, but the predicted products do not show sequence similarity to rep proteins associated with theta-replicating plasmids (15, 32).

Other ORFs with similarity to known genes.

Immediately adjacent to the right IS1627 element (coordinates 111374 to 114761) of the PAI are a cluster of ORFs predicted to encode proteins with sequence similarity to hyaluronate synthetase (hasA), UDP-glucose-pyrophosphorylase (gtaB), and UDP-glucose-dehydrogenase (ywqF) of Streptococcus (ORFs 93 to 95). These enzymes participate in the biosynthesis of serotype-specific capsular polysaccharides in streptococci (11, 13, 16, 17). There is no evidence that a polysaccharide capsule is produced by B. anthracis, and the significance of these genes on pXO1 is not evident.

The remaining ORFs with sequences suggesting function include putative genes that bear resemblance to the following: an erythrocyte invasion gene from Plasmodium yoelii (ORF 13); a putative cell division gene, ftxZ, from Pyrococcus horikoshii (ORF 45); an S-layer precursor gene from B. anthracis (ORF 54); a gene (kln) encoding a putative 478-aa secretory protein kinase from Chlorobium limicola with a conserved nucleoside triphosphate-binding motif that is similar to that of VirB11 in Agrobacterium tumefaciens and Bordetella pertussis (ORF 59); a regulatory element (rapC) from B. subtilis (ORF 136); the pagR regulatory gene of B. anthracis (ORF 138); and a gene encoding a thermonuclease precursor/micrococcocal nuclease from Staphylococcus aureus (ORF 141). There are 108 additional ORFs on pXO1, encoding hypothetical proteins for which there are either no database matches or no assigned functions.

DISCUSSION

The most recognizable feature of the B. anthracis Sterne megaplasmid pXO1 is a putative PAI (27) that houses all three toxin genes and all of their known regulatory elements. Two IS1627 elements (ORFs 96 and 127) mark the molecular boundaries of this 44.8-kb region. Thorne (57) provided evidence that this region can behave as a mobile and distinct unit; the 44.8-kb region is inverted in pXO1 plasmids originating from two different strains of B. anthracis. The pXO1 PAI lacks other characteristics common to PAIs of other organisms. The guanine-plus-cytosine content of the pXO1 PAI (30%) does not differ significantly from that of the rest of the plasmid (32.5%) or the host genome (33%) (52). Also, there is no apparent difference in codon usage between the PAI and non-PAI regions (data not shown). These observations suggest that the majority of the pXO1 sequences must have evolved from backgrounds that are similar to this class of bacilli or related organisms.

The pXO1 sequence does not contain a replication initiator-like protein (repA) and typical reiterated sequences (iterons) containing clusters of direct and inverted repeats that define origins of replication in most theta-replicating plasmids (15, 32, 39). An 11-kb region of the plasmid, corresponding to coordinates 86249 to 97209, has been reported to contain an origin of replication (54). None of the ORFs within this region are predicted to encode proteins with functions related to rep or inc functions in other organisms. Theta-replicating plasmids that do not have iterons or encode proteins like the product of repA (15) include the prototype plasmid ColE1 (reviewed in reference 39) and the B. subtilis plasmid pLS20 (49). ColE1 requires the host DNA polymerase I to initiate replication while replication of pLS20 is independent of polymerase I activity. Although pXO1 has sequences that resemble dnaA boxes and replication termination signals, none of these sequences are tightly clustered within any particular region. Searches for palindromes and secondary structures reveal several sites where palindromes exist in small clusters, but a putative origin cannot be assigned primarily on this basis. These results suggest that pXO1 may have a rare and perhaps unique origin of replication.

The high number of IS-like elements on pXO1 suggests that the PAI and perhaps other regions within this plasmid may have evolved by mechanisms involving duplication, inversion, and deletion. A similar phenomenon appears to have occurred in the Rhizobium 536-kb megaplasmid (from strain NGR234) that has 18% of its sequence in the form of mosaic sequences and ISs (23). Families of transposable elements on these large bacterial plasmids may have driven the movement and evolution of genes with functions related to pathogenicity and symbiosis throughout different species.

The presence of 15 ORFs with similarity to transposases, integrases, and recombinases suggests that pXO1 is a plasmid with a high degree of genetic plasticity. However, the genomes of B. anthracis isolates from diverse origins show extremely low levels of genetic variation at the molecular level (36). It has been argued previously that the severe molecular monomorphism of B. anthracis is the result of either a very recent origin of this species or population size constrictions or bottlenecks associated with the spread of this disease. Due to the lack of other genetic variation, structural rearrangements as observed in pXO1 may play a more important evolutionary role than in other organisms. Indeed, the pXO1 genes encoding activities related to recombination could act in trans to increase structural changes in both the B. anthracis chromosome and in pXO2. Rapid evolutionary change could benefit a pathogen, and genetic linkage of trans-acting recombinases to toxin genes could be an evolved situation.

The Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi, contains at least 17 linear and circular plasmids, whose combined length exceeds 500,000 bp (22). There is one striking similarity between these plasmids and pXO1. The average size of ORFs within the 11 linear Borrelia plasmids is 507 bp. The average size of ORFs in pXO1 is 610 bp. A recent analysis of the Borrelia plasmids indicates that a significant portion of the plasmid genes are damaged due to a myriad of recombinational events between like plasmids (10). The short lengths of the Borrelia plasmid ORFs are apparently due to this decay process, resulting in the accumulation of pseudogenes. It is not clear whether pXO1 is evolving by similar processes. Perhaps a subset of nonfunctional genes within pXO1 are being driven into extinction but are currently trapped in the slow evolution of B. anthracis.

Among the pXO1 ORFs with a high degree of similarity to known genes are two clusters of genes whose potential expression and function could affect the virulence and life cycle of B. anthracis. A cluster of three genes, gerXA, gerXB, and gerXC (ORFs 112, 113, and 114) (26), encode proteins with sequence similarities to proteins involved in the spore germination response in B. subtilis. In B. subtilis, each of four germination response operons, gerA, gerB, gerK, and yfk, encodes three genes (51, 66). For example, the gerA operon contains gerA, gerAB, and gerAC (51). The gerA genes are involved in the germination response to l-alanine. The gerB and gerK loci are involved in the response to a combination of asparagine, glucose, fructose, and KCl. The pXO1-encoded ger genes have recently been shown to belong to a single operon whose function appears to influence the germination rate of B. anthracis spores in a murine alveolar macrophage assay (25, 26). These plasmid-borne gene products appear to facilitate the germination of the bacterial spore at sites within certain mammalian target cells.

Another cluster (ORFs 93, 94, and 95) is a set of three genes that are similar to genes involved in the synthesis of the serotype-specific polysaccharide capsule of virulent group A streptococci. The streptococcal genes hasA, hasB, and hasC are transcribed in an operon and encode hyaluronate synthase, UDP-glucose dehydrogenase, and UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase, respectively (11, 13, 16, 17). The three corresponding pXO1 genes closely resemble the streptoccal genes (Table 1), except that the order of the pXO1 genes is A, C, B. There are no reports of a polysaccharide capsule in B. anthracis. Genes on the other B. anthracis megaplasmid, pXO2, facilitate synthesis of a d-glutamic acid capsule by virulent strains (60). Therefore, pXO1 ORFs 93, 94, and 95 may represent another example of nonfunctional genes that have yet to decay away.

pXO1 contains three IS231 elements with significant homology to their counterparts in the B. cereus subgroup (46). IS231 is a group of ISs originally identified in large plasmids from the entomopathogen B. thuringiensis. These B. thuringiensis ISs are structurally associated with the insecticidal ∂-endotoxin genes and other transposable elements. They harbor two terminal inverted repeats and encode a single transposase related to that found in IS1151 from Clostridium perfringens and the IS4 family of ISs. Following transposition, IS231A generates duplications of between 10 and 12 bp at preferred target sites (46, 53). A recent study of the occurrence and diversity of ISs among B. cereus members shows that, of all the elements tested, IS231 displayed the most widespread distribution and variability (29, 40). Detailed structural and/or functional analyses of several iso-IS231 sequences have since shown that this diversity is not only related to the DNA sequence but also to a modular assemblage of these entities (10b). The presence of IS231 elements in pXO1 confirms previous reports of the existence of these elements in B. anthracis (30). Recent PCR and sequencing data also suggests that IS231-like elements exist on the chromosome of B. anthracis and in the capsule containing plasmid pXO2 (10b). The strong homology (more than 95% identity) between two of the IS231 elements from B. anthracis and IS231E from B. thuringiensis serovar finitimus indicates that either direct exchanges occurred between these hosts or these species at one time shared common genomic pools.

Another observation in pXO1 is the clustering of these three IS231 elements within an 8.5-kb region. This is reminiscent of other IS231 groupings within itself and in association with the class II transposon Tn4430 in B. thuringiensis (44). Mahillon and Chandler (47) recently proposed several mechanisms that could account for this behavior, including the successive insertion of related ISs into a highly preferred region. Insertion specificity appears to have relied on the DNA sequence and structural conformation of the target site for IS231A (28). pXO1 also harbors a Tn4430-like element (ORFs 115 and 116) that spans 3.7 kb and includes a Tn1546-like resolvase and a Tn21-like transposase. However, this element is not linked to the IS231 cluster but is located directly adjacent to the known toxin genes.

Large megaplasmids (50 to 500 kb) that confer selective advantage on their hosts are common throughout microbial communities. Examples include the TOL family of plasmids that allow Pseudomonas species to metabolize toluene and other toxic organic chemicals (2) and the 536-kb plasmid pNGR234a of Rhizobium that promotes the symbiotic relationship between this species and a variety of legumes (23). Many megaplasmids are also known to carry virulence factors. Several gram-positive pathogens, including C. perfringens and B. thuringiensis, harbor such plasmids. Diverse strains of C. perfringens are characterized by their ability to produce numerous extracellular toxins. Genes encoding certain of these toxins are located on the bacterial chromosome, but others are often housed in megaplasmids ranging in size from 90 to 130 kb (19, 35). In B. thuringiensis, at least 50 different insecticidal ∂-endotoxins have been identified on plasmids ranging in size from 60 to 300 kb (1). Clearly, the presence of the structural genes encoding the anthrax toxin proteins on pXO1 results in selection for plasmid maintenance by B. anthracis during infection. However, it is not clear if pXO1 confers a selective advantage on B. anthracis in nonhost environments. Spontaneous loss of pXO1 during growth in laboratory medium is rare. Although pXO1− soil isolates of B. anthracis are uncommon, all environmental strains in our collection were isolated from soil collected near diseased animals (36). It is possible that pXO1− isolates exist in other soil samples. Certain pXO1-associated phenotypes have been noted, but they have not been associated with specific genes. These include altered sensitivity to certain bacteriophages, different nutritional requirements for growth on certain minimal media, and altered sporulation characteristics. Study of the numerous pXO1 ORFs that do not have obvious similarity to known genes may lead to a better understanding of these and other phenotypes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the technical support of Lakshmi Pillai, Lena Martinez, and James Fulwyler.

This work was supported by the Office of Non-Proliferation and National Security, U.S. Department of Energy. Work by A.R.H. and T.M.K. was supported by Public Health Service Grant AI33537 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

⋕ Present address: Nevarus Agricultural Discovery Institute, San Diego, CA 92121.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aronson A I. Insecticidal toxins. In: Sonenshein A L, editor. Bacillus subtilis and other gram-positive bacteria. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 953–963. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Assinder S J, Williams P A. The TOL plasmids: determinants of the catabolism of toluene and the xylenes. Adv Microb Physiol. 1990;31:1–69. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(08)60119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baum J, Gilbert M. Characterization and comparative sequence analysis of replication origins from three large Bacillus thuringiensis plasmids. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5280–5289. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.17.5280-5289.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baum J, Gonzalez J. Mode of replication, size and distribution of naturally occurring plasmids in Bacillus thuringiensis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;96:143–148. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90394-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blattner F, Plunkett G, Bloch C, Perna N, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner J, Rode C, Mayhew G, Jason G, Davis N, Kerkpatrick H, Goeden M, Rose D, Mau B, Shao Y. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 1997;277:1453–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borodovsky M, McIninch J. GeneMark: parallel gene recognition for both DNA strands. Comput Chem. 1993;17:123–133. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brantl S, Behnke D, Alonso J. Molecular analysis of the replication region of the conjugative Streptococcus agalactiae plasmid pIP501 in Bacillus subtilis. Comparison with plasmids pAMb1 and pSM19035. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:4783–4789. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.16.4783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braund C, Le Chatelier E, Ehrlich S, Janniere L. A fourth class of theta-replicating plasmids: the pAM beta 1 family from gram-positive bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11668–11672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bult C, White O, Olsen G, Zhou L, Fleischmann R D, Sutton G G, Blake J A, FitzGerald L, Clayton R, Gocayne J, Kerlavage A, Dougherty B, Tomb J, Adams M, Reich C, Overbeek R, Kerkness E, Weinstock K, Merrick J, Glodek A, Scott J, Geoghagen N, Venter J. Complete genome sequence of the methanogenic archaeon, Methanococcus jannaschii. Science. 1996;273:1058–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5278.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Casjens S, Huang W M, Robertson M, Palmer N, Peterson J, Sutton G, Fraser C. In Abstracts of the 3rd Conference on Microbial Genomes. 1998. Uncontrolled rearrangements among Borrelia linear plasmids? Microbial and comparative genomics, p. C–12. [Google Scholar]

- 10a.Chen, Y., et al. Unpublished data.

- 10b.Chen, Y., R. Okinaka, and J. Mahillon. Unpublished data.

- 11.Crater D, Dougherty B, van de Rijn I. Molecular characterization of hasC from an operon required for hyaluronic acid synthesis in group A streptococci. Demonstration of UDP-glucose pyrophophorylase activity. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:28676–28680. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.48.28676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dai Z, Sirard J-C, Mock M, Koehler T. The atxA gene product activates transcription of the anthrax toxin genes and is essential for virulence. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:1171–1181. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeAngelis P L, Papaconstantinou J, Weigel P H. Molecular cloning, identification, and sequence of the hyaluronan synthase gene from group A Streptococcus pyrogenes. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:19181–19184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deckert G, Warren P, Gaasterland T, Young W, Lenox A, Graham D, Overbeek R, Snead M, Keller M, Aujay M, Huber R, Feldman R, Short J, Olsen G, Swanson R. The complete genome of the hyperthermophilic bacterium Aquifex aeolicus. Nature. 1998;392:353–358. doi: 10.1038/32831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.del Solar G, Giraldo R, Ruiz-Echevarria M J, Espinosa M, Diaz-Orejas R. Replication and control of circular bacterial plasmids. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:434–464. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.2.434-464.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dougherty B, van de Rijn I. Molecular characterization of hasB from an operon required for hyaluronic acid synthesis in group A streptococci. Demonstration of UDP-glucose dehydrogenase activity. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:7118–7124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dougherty B, van de Rijn I. Molecular characterization of hasA from an operon required for hyaluronic acid synthesis in group A streptococci. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:169–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dougherty B, Hill C, Weidman J, Richardson D, Venter J, Ross R. Sequence and analysis of the 60 kb conjugative bacteriocin-producing plasmid pMRC01 from Lactococcus lactis DPC3147. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:1029–1038. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00988.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dupy B, Daube G, Popoff M R, Cole S T. Clostridium perfringens urease genes are plasmid borne. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2313–2320. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2313-2320.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fleischmann R, Adams M, White O, Clayton R, Kirkness E, Kerlavage A, Bult C, Tomb J-F, Dougherty B, McKenney K, Sutton G, FitzHugh W, Fields C, Gocayne J, Scott J, Shirley R, Liu L, Glodek A, Kelley J, Weidman J, Philips C, Spriggs T, Hedblom E, Cotton M, Utterback T, Hanna M, Nguyen D, Saudek D, Barndon R, Fine L, Fritchman J, Fuhrmann J, Geoghagen N, Gnehm C, McDonald L, Small K, Fraser C, Smith H, Venter J. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae RD. Science. 1995;269:496–512. doi: 10.1126/science.7542800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fouet A, Sirard J-C, Mock M. Bacillus anthracis pXO1 virulence plasmid encodes a type DNA topoisomerase. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:471–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fraser C, Casjens S, Huang W M, Sutton G G, Clayton R, Lathigra R, White O, Ketchum K A, Dodson R, Hickeyt E K, Gwinn M, Dougherty B, Tomb J-F, Fleischmann R K, Richardson D, Peterson J, Kerlavage A R, Quackenbush J, Salzberg S, Hanson M, van Vugt R, Palmer N, Adams M D, Gocayne J, Weidman J, Utterback T, Watthey L, McDonald L, Artiach P, Bowman C, Garland S, Fujii C, Cotton M D, Horst K, Roberts K, Hatch B, Smith H O, Venter J C. Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochaete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature. 1997;390:580–588. doi: 10.1038/37551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frelberg C, Fellay R, Balroch A, Broughton W, Rosenthal A, Perret X. Molecular basis of symbiosis between Rhizobium and legumes. Nature. 1997;387:394–401. doi: 10.1038/387394a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green B D, Battisti D L, Koehler T M, Thorne C B, Ivins B E. Demonstration of a capsule plasmid in Bacillus anthracis. Infect Immun. 1985;49:291–297. doi: 10.1128/iai.49.2.291-297.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guidi-Rontani C, Weber-Levy M, Labruyere E, Mock M. Germination of Bacillus anthracis spores with alveolar macrophages. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:9–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guidi-Rontani C, Pereira Y, Ruffie S, Sirard J-C, Weber-Levy M, Mock M. Identification and characterisation of a germination operon on the virulence plasmid pXO1 of Bacillus anthracis. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:407–414. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hacker J, Blum-Oehler G, Muhldorfer I, Tschape H. Pathogenicity islands of virulent bacteria: structure, function and impact on microbial evolution. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:1089–1097. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3101672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hallet B, Rezsöhazy R, Mahillon J, Delcour J. IS231A insertion specificity: consensus sequence and DNA bending at the target site. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:131–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Helgason E, Caugant D, Lecadet M-M, Chen Y, Mahillon J, Lövgren A, Hegna I, Kvaløy K, Kolstø A-B. Genetic diversity of Bacillus cereus/B. thuringiensis isolates from natural sources in Norway. Curr Microbiol. 1998;37:80–87. doi: 10.1007/s002849900343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henderson I, Yu D, Turnbull P C. Differentiation of Bacillus anthracis and other “Bacillus cereus group” bacteria using IS231-derived sequences. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;128:113–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoffmaster A R, Koehler T M. Autogenous regulation of the Bacillus anthracis pag operon. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4485–4492. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.15.4485-4492.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Janniere L, Gruss A, Ehrlich S. Plasmids. In: Sonenshein A, Hoch J, Losick R, editors. Bacillus subtilis and other gram-positive bacteria. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 625–644. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaneko T, Sato S, Kotani H, Tanaka A, Asamizu E, Nakamura Y, Miyajima N, Hirosawa M, Sugiura M, Sasamoto S, Kimura T, Hosouchi T, Matsuno A, Muraki A, Nakzaki N, Naruo K, Okumura S, Shimpo S, Takeuchi C, Wada T, Watanabe A, Yamada M, Yasuda M, Tabata S. Sequence analysis of the genome of the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. II. Sequence determination of the entire genome and assignment of potential protein-coding regions. DNA Res. 1996;3:109–136. doi: 10.1093/dnares/3.3.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaspar R, Robertson D. Purification and physical analysis of Bacillus anthracis plasmids pXO1 and pXO2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1987;149:362–368. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)90375-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katayama S, Dupuy B, Daube G, China B, Cole S T. Genome mapping of Clostridium perfringens strains with I-CeuI shows many virulence genes to be plasmid-borne. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;251:720–726. doi: 10.1007/BF02174122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keim P, Kalif A, Schupp J, Hill K, Travis S E, Richmond K, Adair D M, Hugh-Jones M, Kuske C R, Jackson P. Molecular evolution and diversity in Bacillus anthracis as detected by amplified fragment length polymorphism markers. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:818–824. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.3.818-824.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keppie J, Harris-Smith P W, Smith H. The chemical basis of the virulence of Bacillus anthracis. IX. Its aggressins and their mode of action. Br J Exp Pathol. 1963;44:446–453. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koehler T M, Dai Z, Kaufman-Yarbray M. Regulation of the Bacillus anthracis protective antigen gene: CO2 and a trans-acting element activate transcription from one of the two promoters. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:586–595. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.3.586-595.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kornberg A, Baker T A. DNA replication. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: W. H. Freeman and Company; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Léonard C, Chen Y, Mahillon J. Diversity and differential distribution of IS231, IS232 and IS240 among Bacillus cereus, B. thuringiensis, and B. mycoides. Microbiology. 1997;143:2537–2547. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-8-2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leppla S H. The anthrax toxin complex. In: Alouf J, Freer J, editors. Sourcebook of bacterial protein toxins. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1991. pp. 277–298. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leppla S H. Anthrax toxins. In: Moss J, Iglewski B, Vaughn M, Tu A T, editors. Bacterial toxins and virulence factors in disease. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker; 1995. pp. 543–572. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lukshin A, Borodovsky M. GeneMark.hmm: new solutions for gene finding. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1107–1115. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.4.1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mahillon J, Seurinck J, Delcour J, Zabeau M. Cloning and nucleotide sequence of different iso-IS231 elements and their structural association with the Tn4430 transposon in Bacillus thuringiensis. Gene. 1987;51:187–196. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90307-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mahillon J, Lereclus D. Structural and functional analysis of Tn4430: identification of an integrase-like protein involved in the co-integrate-resolution process. EMBO J. 1988;7:1515–1526. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02971.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mahillon J, Rezsöhazy R, Hallet B, Delcour J. IS231 and other Bacillus thuringiensis elements: a review. Genetica. 1994;93:13–26. doi: 10.1007/BF01435236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mahillon J, Chandler M. Insertion sequences. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:725–774. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.3.725-774.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Makino S, Uchida I, Terakado N, Ssakawa C, Yoshikawa M. Molecular characterization and protein analysis of the cap region, which is essential for encapsulation in Bacillus anthracis. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:722–730. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.2.722-730.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meijer W J J, de Boer A J, van Tongeren S, Venema G, Bron S. Characterization of the replication region of the Bacillus subtilis plasmid pLS20: a novel type of replicon. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:3214–3224. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.16.3214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mikesell P, Ivins B E, Ristroph J D, Dreier T M. Evidence for plasmid-mediated toxin production in Bacillus anthracis. Infect Immun. 1983;39:371–379. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.1.371-376.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moir A, Kemp E H, Robinson C, Corfe B M. The genetic analysis of bacterial spore germination. J Appl Bacteriol. 1994;77:9S–16S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Priest F. Systematics and ecology of Bacillus. In: Sonenshein A, Hoch J, Losick R, editors. Bacillus subtilis and other gram-positive bacteria. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rezsöhazy R, Hallet B, Delcour J, Mahillon J. The IS4 family of insertion sequences: evidence for a conserved transposase motif. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:1283–1295. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Robertson D, Bragg T, Simpson S, Kaspar R, Xie W, Tippetts M. Mapping and characterization of the Bacillus anthracis plasmids pXO1 and pXO2. Salisbury Med Bull. 1990;68(Suppl.):55–58. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Robertson D L, Tippetts M T, Leppla S H. Nucleotide sequence of the Bacillus anthracis edema factor gene (cya): a calmodulin-dependent adenylate cyclase. Gene. 1988;73:363–371. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90501-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sterne M. The use of anthrax vaccines prepared from avirulent (unencapsulated) variants of Bacillus anthracis. Onderstepoort J Vet Sci Anim Ind. 1939;13:307–312. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thorne C. Bacillus anthracis. In: Sonenshein A L, editor. Bacillus subtilis and other gram-positive bacteria. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 113–124. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tomb J-F, White O, Kerlavage A, Clayton R, Sutton G, Fleischmann R, Ketchum K, Klenk H, Gill S, Dougherty B, Nelson K, Quackenbush J, Zhou L, Kerkness E, Peterson S, Loftus B, Richardson D, Dodson R, Khalak H, Glodek A, McKenney K, Fitzegerald L, Lee N, Adams M, Hickey E, Berg D, Gocayne J, Utterback T, Peterson J, Kelley J, Cotton M, Weldman J, Fujii C, Bowman C, Watthey L, Wallin E, Hayes W, Borodovsky M, Karp P, Smith H, Fraser C, Venter J. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1997;388:539–547. doi: 10.1038/41483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tomcsik J. Bacterial capsules and their relation to the cell wall. In: Spooner E T C, Stocker B A D, editors. Bacterial anatomy. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Uchida I, Sekizaki T, Hashimoto K, Terakado N. Association of the encapsulation of Bacillus anthracis with a 60 megadalton plasmid. J Gen Microbiol. 1985;131:363–367. doi: 10.1099/00221287-131-2-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Uchida I, Hashimoto K, Terakado N. Virulence and immunogenicity in experimental animals of Bacillus anthracis strains harbouring or lacking 110 MDa and 60 MDa plasmids. J Gen Microbiol. 1986;132:557–559. doi: 10.1099/00221287-132-2-557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Uchida I, Hornung J, Thorne C, Klimpel K, Leppla S. Cloning and characterization of a gene whose product is a trans-activator of anthracis toxin synthesis. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5329–5338. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.17.5329-5338.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Uchida I, Makino S, Sasakawa C, Yoshikawa M, Sugimoto C, Terakado N. Identification of a novel gene, dep, associated with depolymerization of the capsular polymer in Bacillus anthracis. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:487–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vietri N, Marrero R, Hoover T, Welkos S. Identification and characterization of a trans-activator involved in the regulation of encapsulation by Bacillus anthracis. Gene. 1995;152:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)00662-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Welkos S L, Lowe J R, Eden-McCutchan F, Vodkin M, Leppla S H, Schmidt J J. Sequence and analysis of the DNA encoding protective antigen of Bacillus anthracis. Gene. 1988;69:287–300. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90439-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yamamoto H, Uchiyama S, Nugroho F A, Sekiguchi J. Cloning and sequencing of a 35.7 kb in the 70°–73° region of the Bacillus subtilis genome reveal genes for a new two-component system, three spore germination proteins, an iron uptake system and a general stress response protein. Gene. 1997;194:191–199. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00130-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]