Abstract

The p6Gag protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) is produced as the carboxyl-terminal sequence within the Gag polyprotein. The amino acid composition of this protein is high in hydrophilic and polar residues except for a patch of relatively hydrophobic amino acids found in the carboxyl-terminal 16 amino acids. Internal cleavage of p6Gag between Y36 and P37, apparently by the HIV-1 protease, removes this hydrophobic tail region from approximately 30% of the mature p6Gag proteins in HIV-1MN. To investigate the importance of this cleavage and the hydrophobic nature of this portion of p6Gag, site-directed mutations were made at the minor protease cleavage site and within the hydrophobic tail. The results showed that all of the single-amino-acid-replacement mutants exhibited either reduced or undetectable cleavage at the site yet almost all were nearly as infectious as wild-type virus, demonstrating that processing at this site is not important for viral replication. However, one exception, Y36F, was 300-fold as infectious the wild type. In contrast to the single-substitution mutants, a virus with two substitutions in this region of p6Gag, Y36S-L41P, could not infect susceptible cells. Protein analysis showed that while the processing of the Gag precursor was normal, the double mutant did not incorporate Env into virus particles. This mutant could be complemented with surface glycoproteins from vesicular stomatitis virus and murine leukemia virus, showing that the inability to incorporate Env was the lethal defect for the Y36S-L41P virus. However, this mutant was not rescued by an HIV-1 Env with a truncated gp41TM cytoplasmic domain, showing that it is phenotypically different from the previously described MA mutants that do not incorporate their full-length Env proteins. Cotransfection experiments with Y36S-L41P and wild-type proviral DNAs revealed that the mutant Gag dominantly blocked the incorporation of Env by wild-type Gag. These results show that the Y36S-L41P p6Gag mutation dramatically blocks the incorporation of HIV-1 Env, presumably acting late in assembly and early during budding.

The proteins required for the assembly of infectious retroviruses are initially expressed as three separate polyproteins, Gag, Gag-Pol, and Env (reviewed in references 6 and 26). Of these three proteins, the Gag polyprotein, Pr55Gag in the case of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), is the major structural protein in the viral particle and provides all of the functions needed for retroviral assembly and budding (reviewed in reference 8). The HIV-1 Gag-Pol polyprotein is produced by a translational frameshift within the C terminus of Gag that occurs infrequently, at about 5% of the level of Pr55Gag expression. This precursor contains the viral enzymes required for replication: protease, reverse transcriptase, and integrase. The Env protein complex consists of two proteins: the surface glycoprotein gp120SU, which is noncovalently attached to the transmembrane protein, gp41TM. This complex initiates infection by binding to the host cell and provides for viral entry into the cell by directly fusing with the plasma membrane.

Electron microscopy studies have shown that assembling lentiviruses form a bar-like structure at the cortex of the plasma membrane, presumably consisting of both Gag and Gag-Pol precursors (reviewed in reference 16). As this structure grows, the nascent particle adopts a spherical shape and finally buds from the cell with a coat of plasma membrane that contains Env. The incorporation of surface glycoproteins into retroviral particles (as well as into other enveloped viruses) appears to lack specificity since Envs from distantly related retroviruses as well as glycoproteins from unrelated enveloped viruses can be incorporated into retroviruses by a process called pseudotyping (63). The exceptions to this pseudotyping phenomenon are the lentiviral Envs, which cannot be incorporated into type C viruses due to the long cytoplasmic tails found in their TM proteins (41). While there are several reports of interactions between HIV-1 Gag and Env during assembly (4, 7, 10, 11, 13, 36, 40, 60, 62), the interactions between budding retroviruses and their Envs are not yet understood.

Lentiviruses bud as immature virions containing Gag and Gag-Pol proteins. These polyproteins are cleaved into the individual proteins by the viral protease that is present in the Gag-Pol precursor. This processing starts during budding and is completed well after particle release (26, 28, 29, 57). Cleavage of Gag and Gag-Pol allows for structural rearrangements and interactions that, in turn, induce a morphological rearrangement and form a condensed, well-ordered mature virion structure (reviewed in reference 16). This maturation event is required for viral infectivity (31). The Pr55Gag polyprotein is cleaved by the HIV-1 protease into six major mature protein products: p17MA (matrix), p24CA (capsid), p2Gag (sp1), p7NC (nucleocapsid), p1Gag (sp2), and p6Gag (20). Results from a large number of studies have produced a basic understanding of the roles that MA, CA, and NC play in the virus life cycle both as domains in Pr55Gag and as individual proteins (reviewed in reference 6). In contrast, the function of p6Gag in the virus life cycle is not as well understood as those of the other Gag proteins.

The two functions that have been demonstrated for p6Gag have been mapped to the ends of the molecule. The C terminus of this protein has been shown to be required for the incorporation of Vpr, an accessory protein that appears to have important roles in pathogenesis (32, 33, 37). The N-terminal portion of p6Gag contains a late (L) viral assembly domain that is required for efficient budding of Gag (18). Studies using site-directed mutagenesis and the construction of chimeric viruses have shown that a PTAPP sequence that is highly conserved among the different isolates of HIV-1 is required for the L-domain function of p6Gag (18, 25, 47, 50).

The p6Gag protein has an unusual amino acid composition: overall, its sequence has many polar and positively charged residues (44). Interestingly, analysis of the Gag proteins from HIV-1MN virions has demonstrated that this C-terminal 16-amino-acid (aa) tail is removed from approximately 30% of the p6Gag molecules found in mature HIV-1MN (21). This appears to be the result of an HIV-1 protease cleavage between aa 36 and 37 within the p6Gag sequence KELY36-P37LAS. Comparisons between several HIV-1 strains show that this minor cleavage site as well as the hydrophobic tail of p6Gag is well conserved (44), raising the possibility that this region is important for HIV-1 replication. To determine the importance of this cleavage site and the general nature of the C-terminal region of p6Gag, the amino acids at this minor cleavage site and some of the hydrophobic residues in this portion of p6Gag were altered by site-directed mutagenesis. Mutant viruses were tested for infectivity, and their p6Gag proteins were analyzed. The results show that maintenance of the cleavage site as well as many of the hydrophobic residues is not required for virus replication. Unexpectedly, the data also revealed that mutations within p6Gag can block the incorporation of Env into HIV-1 virions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA mutagenesis.

The pNL4-3 infectious molecular clone of HIV-1 was used for these studies (1) and altered by site-directed mutagenesis using PCR-based methods, either by a single amplification with a mutagenic primer method or by two rounds of amplification using the previously described overlap extension procedure (24). Mutations introduced into p6Gag by this method are as follows: L35P, nucleotide (nt) 2237, T→C; Y36C, nt 2240, A→G; Y36F, nt 2240, A→T; Y36S, nt 2240, A→C; P37H, nt 2243, C→A; L41P, nt 2255, T→C; L44P, nt 2264, T→C; and P49L, nt 2278, C→T. The TML751X mutation altered nt 8472 from an A to a G, producing a leucine-to-nonsense mutation at codon 751, resulting in the truncation of the gp41TM cytoplasmic tail. This mutation is similar to those previously described by Freed and Martin (12) and Mammano et al. (40). An Env-defective mutant, Env−, was constructed so as to contain a −1 frameshift in the Env precursor leader by the deletion of a T at nt 6349. Mutant DNA fragments were inserted into the pNL4-3 backbone (at the ApaI-BclI sites for the p6Gag mutants, the EcoRI-KpnI sites for the Env− frameshift, and the BamHI-XhoI sites for the L751X mutant) to produce the mutant molecular clones. After construction, the region of the DNA that was PCR amplified was sequenced to confirm the mutation and to rule out the possibility of any additional changes introduced during the mutagenesis process.

Cell culture methods.

293T transformed human kidney and HeLa-CD4-LTR-lacZ (HCLZ; gift of David Waters, AIDS Vaccine Program) cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium; H9 T-cell leukemia cells and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) (provided by the blood donor program of the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md.) were cultured in RPMI 1640. All media were supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U of penicillin per ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml. All cell culture products were obtained from Life Technologies Inc. (Gaithersburg, Md.). Transfections of 293T cells were carried out by using a calcium phosphate mammalian cell transfection kit (5 Prime-3 Prime, Inc., Boulder, Colo.) according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. DEAE-dextran transfections of H9 cells were carried out on 5 × 106 H9 cells for 20 min at room temperature at a DNA concentration of 5 μg/ml and a DEAE-dextran concentration of 200 μg/ml in 0.1 M Tris-HCl-buffered RPMI 1640 medium without supplements. Virion production was measured by reverse transcriptase assay on cell culture supernatants as previously described (17). All infections were done in the presence of polybrene (2 μg/ml), with sheared salmon sperm DNA (sssDNA) as a negative control. The HCLZ assay, a method to measure viral infectivity similar to that used for the MAGI assay (30), was performed as previously described (17). Briefly, a six-well tissue culture cluster (product no. 3506; Costar, Cambridge, Mass.) was seeded with 5 × 105 HCLZ cells the day before infection. The cells were infected with dilutions of virus, and the assay was developed for β-galactosidase activity with a 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-galactoside stain 48 h postinfection. Positive-staining cells (those colored blue from infection) were observed by light microscopy and counted (as blue cell-forming units [BCFU]) to score infection events. The ability of viruses to replicate was measured by infecting H9 cells as previously described (17). Briefly, H9 cells were exposed to 10-fold dilutions of virus, and the cultures were monitored periodically for infection by the presence of and increase in reverse transcriptase activity in the culture medium. Infections using PBMC were carried out as follows. PBMC were separated from whole blood by centrifugation with Ficoll and stimulated with phytohemagglutinin (PHA) for 48 h before infection. Infections were carried out by plating 106 cells and dilutions of virus into 24-well plates; 24 h later, the PHA and virus were removed and 2 ml of RPMI 1640 medium with 50 U of recombinant interleukin-2 (Life Technologies Inc.) was added. Samples were taken at 4 and 12 days postinfection and assayed for reverse transcriptase activity. Pseudotyping of HIV-1 mutants was accomplished by calcium phosphate cotransfection of 293T cells with a vesicular stomatitis virus G protein (VSV-G) expression construct pCMVHg (5) (a gift of Jane Burns, University of California) or a clone of the Mo10A1 murine leukemia virus (MuLV), pRB161-7 (46) (gift of Robert Gorelick, National Cancer Institute, Frederick Cancer Research and Development Center).

Protein analysis.

Virions were isolated by centrifugation through a 20% sucrose pad in an SW28Ti rotor at 25,000 rpm at 4°C for 1 h. Lysates of transfected cells were prepared by washing T150 flasks that contain the adherent cells in phosphate-buffered saline (Life Technologies), followed by lysis with 2 ml of a 20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5)–0.2 M NaCl–1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 solution. Cell debris were removed from the lysates by centrifugation at 2,500 × g. Immunoblot analysis was performed as previously described, using the enhanced chemiluminescence procedure (Amersham Life Science, Arlington Heights, Ill.) (22). Equal amounts of virions as measured by reverse transcriptase activity (∼1.2 × 107 cpm) and 2% of the cell lysates were used for immunoblot analysis. Monoclonal antibody against gp120SU, rabbit antiserum against gp41TM and p6Gag, and goat antiserum against p24CA were obtained from the AIDS Vaccine Program. Monoclonal antibody against gp41TM was obtained from New England Nuclear Inc. (Boston, Mass.). For microscale high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC), HIV-1 samples were treated with freshly prepared guanidine-HCl (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) to a final concentration of 4 M, and then the samples were reduced by the addition of 3% (vol/vol) β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) for 30 min at 37°C. The samples were separated by using a Shimadzu HPLC system (composed of LC-10AD pumps, SCL-10A system controller, CTO-10AC oven, FRC-10A fraction collector, and SPD-M10AV diodearray detector) with a 2.1- by 100-mm Poros R2/H narrow-bore column (Boehringer GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) at a flow rate of 300 μl/min, using a 3 to 60% (vol/vol) linear gradient of water with 0.1% (vol/vol) trifluoroacetic acid and acetonitrile with 0.0875% (vol/vol) trifluoroacetic acid, respectively. The molecular weights of selected proteins were measured by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time-of-flight mass spectrometry using a Shimadzu Kompact Maldi-II laser desorption mass spectrometer. One microliter of sample, containing approximately 1 to 100 pmol, was mixed with 0.3 μl of matrix suspension (sinapinic acid [10 mg/ml] in 50% water–50% acetonitrile) directly on the stainless steel target plate. Laser desorption/ionization mass spectra were acquired with a low laser fluence; each spectrum was the sum of at least 100 laser shots. Three molecular mass standards, substance P (1,349.6 Da), bovine insulin (5,734.6 Da), and ubiquitin (8,565.9 Da), were used as standards for the mass measurement of the p1, p7NC, and p6Gag proteins.

RESULTS

Mutagenesis of the p6Gag tail region.

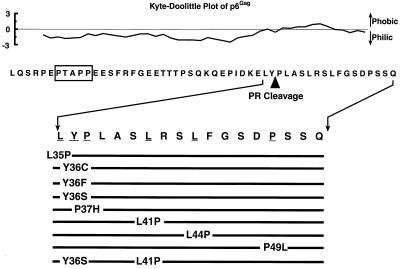

The hydropathic character of the p6Gag sequence was analyzed by the Kyte-Doolittle algorithm (34), and the plot confirmed that this protein is predominantly hydrophilic (Fig. 1). However, the analysis also showed that some of the residues in the C-terminal 16 aa of p6Gag have a more hydrophobic character than the rest of the protein. It has been shown that a substantial fraction of the p6Gag proteins inside HIV-1 virions (approximately 30% in the case of HIV-1MN) are cleaved internally between Y36 and P37 (21) (Fig. 1). Interestingly, this cleavage physically separates the highly hydrophilic region from the more hydrophobic region, producing three species of p6Gag inside the virion: a full-length 52-aa, an N-terminal 36-aa, and a C-terminal 16-aa species. The functional significance of this cleavage site or of the p6Gag tail’s hydrophobic nature is not understood.

FIG. 1.

Mutations in p6Gag. Hydropathic analysis of p6Gag (using a 10-aa window) is presented above its sequence; mutations made to the C-terminus of p6Gag are presented below. Amino acids are represented by the standard single-letter code. The L domain in p6Gag is boxed. The internal protease cleavage site in p6Gag is indicated below the amino acid sequence.

To determine whether any of these sequences in p6Gag, either the minor protease cleavage site or some of the C-terminal hydrophobic residues, are important for HIV-1 assembly and replication, a series of site-directed mutations was made in this region of the pNL4-3 molecular clone. Since the gag and pol reading frames overlap in this region, the mutations that can be made within the coding sequence of p6Gag without altering the pol reading frame are generally limited to those in the second position of the gag codon that are redundant in the wobble base of the pol frame. A summary of the single amino acid mutations made in p6Gag is presented in Fig. 1. Based on the Poorman algorithm, the internal p6Gag protease cleavage site (KELY36-P37LAS) site is predicted to be a marginal site for digestion, consistent with its limited use in vivo (49). Three substitutions, Y36S, Y36C, and P37H, that should reduce or eliminate the internal protease cleavage of p6Gag were made to the amino acids on either side of the scissile bond (49, 61). Additionally, we constructed the Y36F mutant, in which the tyrosine at the scissile bond is replaced with a phenylalanine, a residue that should not inhibit cleavage at this internal site (49, 61). The importance of the hydrophobic amino acids in the C terminus of HIV-1 was tested with other mutants (L35P, L41P, and L44P) which decreased the hydrophobic nature of the carboxyl-terminal region of p6Gag without adding ionic charge to the sequence. A P49L mutant was made to test the addition of a hydrophobic residue in the otherwise hydrophilic six amino acids at the extreme carboxyl terminus of p6Gag. Finally, we constructed the double mutant Y36S-L41P, in which the internal cleavage site and one of the hydrophobic residues in p6Gag were altered (Fig. 1).

Infectivity and replication of mutants.

The mutant DNA constructs were transiently transfected into 293T human kidney fibroblasts to produce virus. All of these mutants appeared to produce near-wild-type levels of reverse transcriptase at the 48- and 72-h harvests (data not shown). The mutant viruses were examined for the ability to carry out a single round of infection, using HCLZ cells in an LTR-lacZ Tat complementation assay. The results (Table 1) showed that all but two of the mutant viruses tested gave titers that were essentially equivalent to those of the wild-type virus. The Y36F mutant had a titer that was approximately 300-fold lower than titers for the other mutant and wild-type samples, while the Y36S-L41P mutant had essentially no titer (2 BCFU/ml) in the HCLZ assay.

TABLE 1.

Infectivity of p6Gag mutants

| Virus | BCFU/mla | TCID/ml

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| H9 | PBMC | ||

| sssDNA (negative control) | <1 | <1 | <1 |

| NL4-3 | 2 × 105 | ≥105 | ≥105 |

| L35P | 1 × 105 | 104 | ≥105 |

| Y36C | 1 × 105 | 104 | ≥105 |

| Y36F | 6 × 103 | 103 | 104 |

| Y36S | 2 × 105 | 104 | ≥105 |

| P37H | 1 × 105 | 104 | ≥105 |

| L41P | 2 × 105 | 104 | ≥105 |

| L44P | 4 × 105 | 104 | ≥105 |

| P49L | 1 × 105 | 104 | ≥105 |

| Y36S-L41P | 2 | <1 | <1 |

Determined by HCLZ assay.

In addition to a single-round infection assay, the ability of the mutants to carry out multiple rounds of replication was examined by the infection of the H9 T-cell leukemia line with a series of 10-fold dilutions of virus. Similar to the infectivity results, most of the mutants exhibited tissue culture infective dose (TCID) titers somewhat lower than wild-type TCID titers (Table 1). The two exceptions were the Y36F mutant, which had a titer at least 100-fold lower than the wild-type titer, and the Y36S-L41P mutant, which produced no detectable infection with this assay. Considering that mutations in HIV can sometimes have a different effect in primary cells than in established cell lines, the mutant viruses were also assayed for the ability to replicate on PHA-stimulated human PBMC, using the same method as used for the H9 experiment. The results from these primary cells essentially corresponded with the data obtained from the H9 T-cell leukemia cells (Table 1): all of the single-substitution mutants were able to replicate, though at a lower dilution than for the wild type, while Y36S-L41P showed no evidence of replication.

The infectivity and replication assays presented above showed that the Y36S-L41P mutant was profoundly defective (Table 1). Based on these results, the Y36S-L41P virus was at most 10−5-fold as infectious as similar amounts of wild-type virus. In a long-term replication experiment, several H9 cell cultures were exposed to Y36S-L41P virus and then cultured for 6 months yet did not produce a detectable infection (data not shown). Additionally, transfection of H9 cells with this construct followed by long-term culture failed to produce a spreading infection under conditions that readily detected the virus replicating from wild-type DNA as well as DNAs of poorly replicating mutants (data not shown). Together, all of these data show that this mutation did not revert to a virus that could replicate even after prolonged cell culture, suggesting that this defect did not allow even a low level of infection.

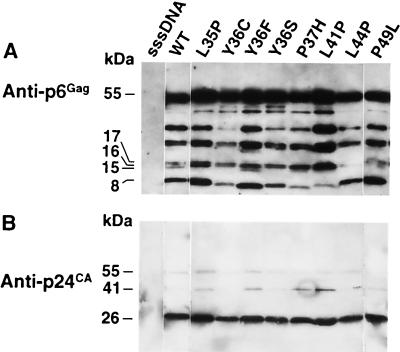

Virion samples produced by transfection of the infectious mutants into 293T cells were analyzed by p6Gag and p24CA immunoblot analysis. The characterization of the Y36S-L41P mutant is presented below. The results of the p6Gag immunoblot showed that for most of the preparations, the wild-type and the single-substitution mutant samples produced essentially similar patterns of mature and partially cleaved p6Gag proteins (Fig. 2A). However, the p6Gag bands in some of the mutant samples migrated higher in the blot than wild-type bands. Additionally, the intensities of some of the p6Gag bands were stronger or weaker than for the wild-type control. The intensity differences are not caused by differential reactivity with the antiserum or unequal sample loading, as Pr55Gag is detected equally in the samples. The hydrophilic nature of p6Gag apparently causes the wild-type protein to migrate higher than expected (8 versus 6 kDa) and to transfer poorly onto polyvinylidene difluoride (19). Therefore, mutations introduced into p6Gag, especially those that alter the small amount of hydrophobic character that the protein possesses, could be the cause of these anomalous immunoblot results. Immunoblot analysis of p24CA (Fig. 2B) showed that all of the samples had comparable amounts of p24CA, with no gross differences in Gag processing between the wild-type and mutant samples. These results, along with the reverse transcriptase data, indicate that the single-substitution mutations do not appear to measurably impact virion budding or Gag processing.

FIG. 2.

Immunoblot analysis of the single-substitution mutants. A single set of blots was exposed to antiserum against p6Gag (A) and then successively stripped and reprobed with antiserum to p24CA (B). The virion samples produced by transfection (corresponding to ∼1.2 × 107 cpm of reverse transcriptase activity) are identified above each lane. sssDNA, mock control; WT, sample of the wild-type NL4-3 virions. The apparent molecular masses as determined by relative mobility are presented at the left.

Cleavage of the p6Gag internal protease site.

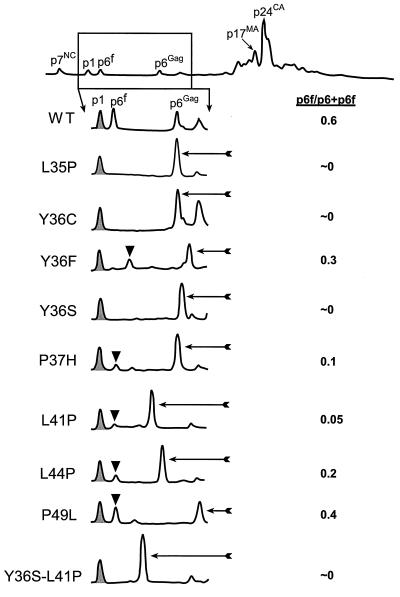

Due to the hydrophobic nature of the N-terminal p6Gag cleavage product, immunoblot analysis is unable to reliably detect this protein (19) and cannot be used to determine whether the minor protease site was processed in the mutants. Therefore, these mutant virions were analyzed by microscale HPLC so that the various products of p6Gag can be isolated, characterized, and quantitated. Approximately 5 μg (total protein) of virus produced from the wild-type DNA and each mutant construct was subjected to microscale HPLC analysis, and the peaks containing mature Gag proteins were identified by immunoblotting, mass spectrometry, sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by staining of the gel with Coomassie brilliant blue (C-PAGE), and protein sequence analyses. These analyses revealed no significant differences in the HPLC profiles of the other mature Gag proteins between the wild-type and mutant samples, confirming that overall processing occurs normally for all the mutants (Fig. 3 and data not shown). The HPLC chromatograms of the p6Gag region for all the viruses tested are presented in Fig. 3. Compared to the wild-type sample, which eluted as expected from previous experiments, the mutant p6Gag proteins were resolved at somewhat different positions within the chromatograms due to the sequence changes in these relatively small proteins. The molecular weights of the proteins within the peaks in this region of the HPLC were determined by mass spectroscopy (Table 2). The data matched the values calculated from the full-length sequence of the wild-type NL4-3 and mutant p6Gag proteins, confirming the identity of the peaks and demonstrating that these proteins were not internally cleaved. Sequence and mass spectrometry data of the peak that elutes between p1 and p6Gag, labeled p6f in Fig. 3, revealed that it contained both of the N- and C-terminal p6Gag cleavage fragments. This peak, when present, was found in most of the mutant samples except for Y36F, where the N-terminal cleavage product appeared to elute later in the chromatogram, probably due to the hydrophobic Y-to-F exchange. Mass spectrometry of this peak showed that it had the expected size for the Y36F N-terminal fragment, confirming the identity of this peak. The mass spectrometry data for all of the p6Gag-containing peaks were in good agreement with the values calculated from the sequences (Table 2), showing that the majority of these mutant proteins were full length, correctly processed, and not posttranslationally modified.

FIG. 3.

HPLC analysis of p6Gag mutants. The complete HPLC chromatogram for wild-type NL4-3 virions is shown at the top, with the region presented below boxed. The identities of the Gag proteins determined by C-PAGE, immunoblotting, protein sequence, and mass spectrometry are identified above the peaks. The p1Gag peak is shaded; the p6Gag fragment peak, labeled p6f on the wild-type (WT) profile, is identified by a black triangle; full-length mutant p6Gag is highlighted with an arrow. The relative amount of p6Gag cleaved versus the total p6Gag present (all three species) is presented on the right.

TABLE 2.

Mass spectrometry results of HPLC-purified Gag proteins

| Protein | Mol wt

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Observed | Difference from calculated (%) | |

| p6Gag (NL4-3) | 5,811.20 | +3.84 (0.07) |

| p6Gag (NL4-3, aa 1–36) | 4,164.70 | +1.16 (0.02) |

| p6Gag (NL4-3, aa 37–52) | 1,663.39 | +1.55 (0.09) |

| p6Gag L35P | 5,802.63 | +11.31 (0.1) |

| p6Gag Y36C | 5,755.00 | +7.64 (0.1) |

| p6Gag Y36F | 5,788.70 | −2.66 (0.04) |

| p6Gag Y36F (aa 1–36) | 4,146.90 | −0.46 (0.01) |

| p6Gag Y36S | 5,739.42 | +8.16 (0.1) |

| p6Gag P37H | 5,845.00 | −2.38 (0.04) |

| p6Gag L41P | 5,789.37 | −1.95 (0.03) |

| p6Gag L44P | 5,778.60 | −12.53 (0.2) |

| p6Gag P49L | 5,808.70 | −14.71 (0.3) |

| p6Gag Y36S-L41P | 5,717.80 | +2.58 (0.05) |

| p1Gag (NL4-3) | 1,841.50 | +0.34 (0.02) |

| p2Gag (NL4-3) | 1,466.48 | +2.80 (0.2) |

| p7NC (NL4-3) | 6,382.35 | +22.98 (0.36) |

The HPLC analysis showed that approximately 60% of the p6Gag protein from wild-type HIV-1NL4-3 was cleaved at the Y36-P37 junction (Fig. 3; Table 2) as estimated from the relative areas of the A206 peaks in the chromatogram. In contrast, the internal cleavage of p6Gag in all of the single-amino-acid-substitution mutants was impaired to various degrees. Three of the single-substitution mutants, L35P, Y36C, and Y36S, exhibited no detectable cleavage of p6Gag, while two others, P37H and L41P, had very low levels (more than 10-fold lower than wild-type levels). The remainder, mutants Y36F, L44P, and P49L, had levels of processed p6Gag that were moderately (two- to threefold) lower than wild-type levels. Since the mutants that did not cleave at this minor site were nearly as infectious as wild-type virus (Table 1), these results show that protease cleavage does not appear to be required for infectivity. In fact, the only single-amino-acid-substitution mutant that exhibited significantly impaired infectivity and replication was the Y36F mutant, which had the second-highest level of cleavage of the mutants at the internal site (Fig. 3).

Protein analysis of Y36S-L41P.

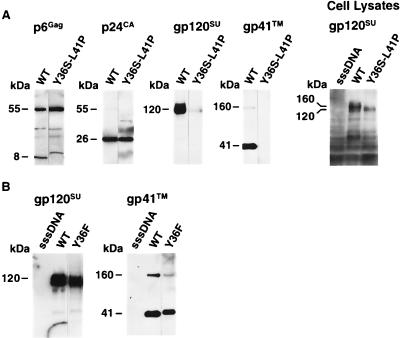

To examine the reason for the striking defect in infectivity and replication exhibited by Y36S-L41P, proteins from the mutant were analyzed. Immunoblot analysis of wild-type and Y36S-L41P mutant virions with p6Gag antiserum revealed that the mutant p6Gag band migrated higher than the wild-type protein (Fig. 4A), similar to the result with the other mutants. Stripping and reprobing the blot with p24CA antiserum showed that the mutant and wild-type samples produced equivalent signals of p24CA, indicating that similar amounts of virus were present on the blot and the processing to produce this protein occurred normally (Fig. 4A). HPLC and mass spectrometry analysis of the Y36S-L41P mutant showed that the mature p6Gag of the Y36S-L41P mutant was not cleaved at the internal Y36-P37 site in p6Gag (Fig. 3; Table 2), yet the other Gag proteins eluted as expected (data not shown), confirming that Gag is processed normally.

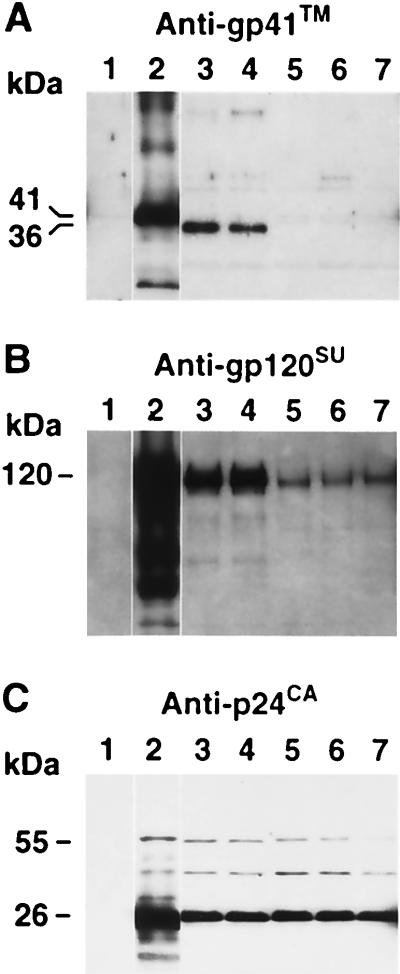

FIG. 4.

Immunoblot analysis of Y36S-L41P and Y36F virions. (A) Blots of both wild-type NL4-3 (WT) and Y36S-L41P virion samples produced from transfection (corresponding to ∼1.2 × 107 cpm of reverse transcriptase activity) as well as samples of lysates isolated from cells transfected with viral constructs (2% of the lysate from a confluent T150 flask). (B) Immunoblots of wild-type and Y36F virions samples produced from transfection (corresponding to ∼1.2 × 107 cpm of reverse transcriptase activity). Samples are identified above the lanes, and the antiserum used for each reaction is noted above each blot. Molecular masses as determined by relative mobility are presented on the left.

Since the proteolytic cleavage of Gag appeared normal and the levels of reverse transcriptase activity suggested that the Pol proteins were not affected by the mutation, the presence of Env was examined by immunoblot analysis. The results showed that a nearly undetectable amount of gp120SU was associated with the purified virions compared to wild-type (Fig. 4A). Since gp120SU can be spontaneously shed from the surface of HIV-1-infected cells, the small amount of gp120SU found associated with the mutant could be due to contamination of the virion preparations by these shed proteins. To confirm that Env is not on the virion, immunoblot analysis for gp41TM, which is not shed from cells or virions, was carried out. The results clearly showed that, unlike the wild-type virions, the Y36S-L41P mutant contained no detectable gp41TM protein, confirming the gp120SU result. A gp120SU immunoblot of cell lysates from 293T cells transfected by the Y36S-L41P and wild-type constructs showed that mature Env was expressed by both the mutant and wild-type constructs (Fig. 4A).

An Env packaging defect could also be the explanation for the lower infectivity of the Y36F mutant. Virions produced by the Y36F and wild-type constructs were examined by both gp120SU and gp41TM immunoblot analysis to determine whether the levels of Env were lower for this mutant. The results show that the levels of either of these proteins were not significantly different from those of the wild-type sample (Fig. 4B). Therefore, the defect in the Y36F mutant is not in the packaging of Env.

Since the immunoblot results reveal that Env is expressed by the Y36S-L41P mutant but not packaged, it was important to confirm that these results are from the Y36S and L41P substitutions and not from any inadvertent mutations introduced into the construct during cloning. As with all of the mutants, the ApaI-to-BclI region that was subjected to mutagenesis was sequenced after reconstruction into the full-length viral DNA to confirm the expected sequence. To demonstrate that the sequences outside the mutated fragment were not altered in this mutant, the ApaI-BclI fragment that contained the Y36S-L41P mutation was placed in a new pNL4-3 backbone. Reciprocally, the backbone of the mutant was combined with a wild-type ApaI-BclI fragment from pNL4-3. Transfection and analysis of these two DNAs produced the expected results: virus produced from the former construct had the mutant phenotype and virus from the latter produced the wild-type phenotype (data not shown). As an additional check, the EcoRI-to-XhoI fragment of the Y36S-L41P mutant that contains env was cloned into a wild-type background. The properties of this reconstruction were indistinguishable from those of the wild type (data not shown).

Rescue of Y36S-L41P by pseudotyping.

The results shown above suggest that the Y36S-L41P mutant is primarily defective due to the absence of Env in the particles. However, this mutation may also produce other defects in the viral life cycle that cannot be determined due to the inability of this mutant to efficiently bind and enter host cells. To test this possibility, the mutant was cotransfected with a VSV-G expression plasmid in hopes of pseudotyping the Y36S-L41P mutant and bypassing the Env incorporation defect. As controls, the wild-type construct and an Env− mutant that contains a frameshift mutation in the leader sequence of the env gene (thus does not produce gp120SU or gp41TM) were also cotransfected with the VSV-G expression construct. The resultant viruses were assayed for infectivity in the HCLZ assay to determine whether these virions could undergo one round of replication. The results, presented in Table 3, showed that VSV-G clearly rescued the Y36S-L41P mutant to near wild-type levels, higher than the level of the pseudotyped Env− mutant. The ability of the VSV-G envelope to rescue the infectivity of the Y36S-L41P mutant suggests that the inability to incorporate Env is the only defect in this mutant. However, recent work by Aiken has shown that VSV-G pseudotyping of an Env− HIV-1 mutant suppresses the requirement for Nef and viral sensitivity to cyclosporin A compared to HIV-1 that uses its own Env to enter the cell (2). Therefore, even though the Y36S-L41P was rescued by VSV-G pseudotyping, it is still possible that the endocytic mode of entry used by this glycoprotein masks other defects in this mutant. To test this possibility, the Y36S-L41P mutant was cotransfected with an expression plasmid for Mo10A1, an MuLV whose Env, like HIV Env, uses a direct fusion mechanism with the host plasma membrane and can infect human cells (42, 43, 46, 55). Previous studies have shown that MuLV Env can pseudotype HIV-1 and rescue HIV-1 Env-deficient viruses (35, 39, 53). The results showed that the MuLV Env rescued the Y36S-L41P mutant (Table 4). The efficiency of the rescue was considerably lower than the VSV-G results, consistent with data from other studies (2, 38). The reduced levels may be due to differences in incorporation into the virion and/or receptor usage by these two surface glyco-proteins. Since the source of MuLV Env was the Mo10A1 molecular clone, this DNA also produced an MuLV that can infect human cells. However, since MuLV does not produce Tat, it did not score positive in the HCLZ assay (Table 4). Since pseudotyping with either VSV-G or 10A1 Env protein can complement the mutant phenotype, these data confirm that the defect in Y36S-L41P is in the incorporation of the HIV-1 Env into the virion and not in other aspects of assembly or infection.

TABLE 3.

Rescue of Y36S-L41P mutant by VSV-G

| Transfection mixturea | Titer

|

|

|---|---|---|

| BCFU/mlb | Relative to NL4-3 + sssDNA | |

| sssDNA (negative control) | <1 | <8 × 10−7 |

| NL4-3 + sssDNA | 1.3 × 106 | 1 |

| NL4-3 + VSV-G | 1.2 × 107 | 11 |

| Y36S-L41P + VSV-G | 1.4 × 105 | 0.1 |

| NL4-3 Env− + VSV-G | 5.3 × 104 | 4 × 10−2 |

| Y36S-L41P + sssDNA | 8 | 6 × 10−6 |

| NL4-3 Env + sssDNA | 62 | 5 × 10−5 |

| sssDNA + VSV-G | <1 | <8 × 10−7 |

1:1 (wt/wt) DNA cotransfection ratio.

Determined by HCLZ assay.

TABLE 4.

Rescue of Y36S-L41P mutant by MuLV Env

| Transfection mixturea | Titer

|

|

|---|---|---|

| BCFU/mlb | Relative to NL4-3 + sssDNA | |

| sssDNA (negative control) | 7 | 6 × 10−6 |

| NL4-3 + sssDNA | 1.2 × 106 | 1 |

| NL4-3 + Mo10A1 | 2.7 × 106 | 2 |

| Y36S-L41P + Mo10A1 | 3.9 × 104 | 3 × 10−2 |

| NL4-3 Env− + Mo10A1 | 7.9 × 103 | 7 × 10−3 |

| Y36S-L41P + sssDNA | 9 | 8 × 10−6 |

| NL4-3 Env− + sssDNA | 16 | 1 × 10−5 |

| sssDNA + Mo10A1 | <1 | <8 × 10−7 |

1:1 (wt/wt) DNA cotransfection ratio.

Determined by HCLZ assay.

The results presented above show that the phenotype of the Y36S-L41P mutant is very similar to those of p17MA mutants that have amino acid changes within the first 30 residues of MA (10, 11, 13, 62). These mutants were unable to incorporate Env complexes but could be rescued by both wild-type MuLV Env and mutant HIV-1 Env that contained a truncation in the cytoplasmic domain of gp41TM (12, 40). Studies of the MA crystal structure suggest that this particular block is due to a steric interference between p17MA and the cytoplasmic domain of gp41TM within the immature virions (23, 51). To determine if a similar mechanism is responsible for the failure to incorporate Env into the Y36S-L41P virions, the identical truncation of gp41TM (removing 104 aa from the cytoplasmic tail) was constructed and introduced into both pNL4-3 wild-type and the Y36S-L41P mutant DNA constructs. These Env truncation mutants were tested for infectivity by HCLZ assay and for Env incorporation by immunoblot analysis. The results revealed that the two separate clones of a construct with a wild-type Gag and the truncated envelope, NL4-3/TML751X, were infectious (Table 5) and incorporated Env: gp120SU and a 36-kDa species of gp41TM (Fig. 5, lanes 2 and 3), consistent with the previous studies (12, 40). In contrast, two clones with the combination of the Y36S-L41P Gag mutation and the Env truncation, Y36S-L41P/TML751X, showed very low infectivity in the HCLZ assay (Table 5) and did not incorporate detectable levels of the truncated gp41TM (Fig. 5, lanes 3 and 4). Immunoblot analysis detected much lower levels of gp120SU in the p6Gag mutant samples than in the wild-type Gag constructs (Fig. 5). As proposed before, this is likely to be shed gp120SU that contaminates the sucrose density-pelleted material, indicating that Env was produced by these constructs and expressed on the surface of the cells. These results show that, unlike the MA mutants, the Y36S-L41P mutant could not incorporate the truncated Env and thus is functionally different from those p17MA mutants.

TABLE 5.

Infectivity of TM truncation mutants

| Virus | Titer

|

|

|---|---|---|

| BCFU/mla | Relative to NL4-3 | |

| None | 8 | 6 × 10−6 |

| NL4-3 | 1.4 × 106 | 1 |

| NL4-3/TML751X | 9.7 × 105 | 0.7 |

| NL4-3/TML751X | 2.0 × 106 | 1 |

| Y36S-L41P | 10 | 7 × 10−6 |

| Y36S-L41P/TML751X | 93 | 4 × 10−5 |

| Y36S-L41P/TML751X | 60 | 1 × 10−5 |

Determined by HCLZ assay.

FIG. 5.

Immunoblot analysis of virions with the gp41TM L751X mutation. The same blot of both wild-type NL4-3 and mutant virion samples produced from transfection (corresponding to ∼1.2 × 107 cpm of reverse transcriptase activity) was analyzed with gp41TM antibody (A) and then successively stripped and reprobed with gp120SU antibody (B) and p24CA antiserum (C). Lanes: 1, sssDNA (negative control); 2, wild-type NL4-3; 3 and 4, two separate clones of NL4-3/TML751X; 5 and 6, two separate clones of Y36S-L41P/TML751X; 7, Y36S-L41P. Molecular masses as determined by relative mobility are presented on the left.

Y36S-L41P exhibits a dominant negative effect.

The Env incorporation defect of the Y36S-L41P mutant could be due to the inactivation of an important domain in Gag or, alternatively, to the introduction of a sequence that blocks the incorporation of Env. Studies have shown that wild-type Gag can complement Gag-Pol precursor mutants in trans (48, 54) and that Gag mutants can dominantly interfere with wild-type Gag assembly in trans (58), suggesting that HIV-1 Gag molecules can form functionally mixed particles. To determine whether wild-type Gag can complement the Y36S-L41P, the mutant and wild-type constructs were cotransfected into 293T cells at a ratio of 9 to 1 to coexpress these two Gag proteins. As controls, transfections with similar amounts of mutant or wild-type plasmids with the appropriate amount of carrier were also tested. The resultant virus stocks were assayed for a single round of infectivity with the HCLZ assay. The data (Table 6) showed that the 9-to-1 cotransfection produced a titer 3,000-fold lower than that produced by the wild-type transfection. It is important to note that while the ratio of mutant Gag to wild-type Gag is different in the cotransfections, the total expression of viral proteins is essentially the same as for either the wild-type or mutant DNA transfections (Fig 6B). These results show that the mutant dominantly interferes with the ability of the wild-type Gag proteins to incorporate Env. A control cotransfection of sssDNA and wild-type DNA at a 9-to-1 ratio produced a titer 10-fold lower than that produced by the wild-type transfections. The large difference between this control and the 9-to-1 mutant-to-wild-type cotransfection shows that the reduction in titer was due to the presence of the mutant phenotype and not simply less wild-type expression. The virus stock produced from a 1-to-1 cotransfection of Y36S-L41P and wild-type yielded a titer 10-fold lower than that found after transfection with the wild type (Table 6). This weaker inhibition demonstrates that the negative effect was dependent on the relative amount of mutant DNA in the transfection. Taken together, these results show that the Y36S-L41P mutant Gag inhibits the infectivity of the wild-type virions in trans, apparently by forming virions that contain both mutant and wild-type Gag proteins during particle formation.

TABLE 6.

Cotransfection of Y36S-L41P and wild-type constructs

| Transfection | DNA cotransfection ratio (wt/wt) | Titer

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| BCFU/mla | Titer to NL4-3 | ||

| sssDNA (negative control) | <1 | <5 × 10−6 | |

| pNL4-3 | 2 × 105 | 1 | |

| Y36S-L41P | <1 | <5 × 10−6 | |

| Y36S-L41P + pNL4-3 | 9:1 | 5 × 101 | 3 × 10−3 |

| Y36S-L41P + pNL4-3 | 1:1 | 2 × 104 | 10−1 |

| sssDNA + pNL4-3 | 9:1 | 2 × 104 | 1 × 10−1 |

| Y36S-L41P + sssDNA | 9:1 | 1 | 5 × 10−6 |

Determined by HCLZ assay.

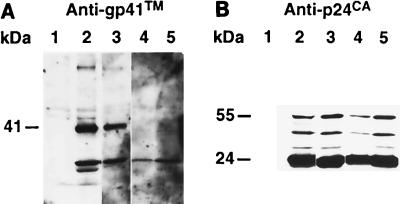

FIG. 6.

Immunoblot analysis of Y36S-L41P and wild-type cotransfectants. A blot containing virion samples produced from the cotransfections (corresponding to ∼1.2 × 107 cpm of reverse transcriptase activity) was reacted with anti-gp41TM antibody and then stripped and reacted with antiserum against p24CA. Lanes: 1, sssDNA (negative control); 2, wild-type NL4-3; 3, Y36S-L41P and NL4-3 transfection at a 1-to-1 ratio; 4, Y36S-L41P and NL4-3 transfection at a 9-to-1 ratio; 5, Y36S-L41P.

Virions from the mutant and wild-type cotransfections were examined to determine whether the loss of infectivity was due to an inhibition of Env incorporation. A gp41TM immunoblot of virions produced from the cotransfections showed that both the samples from the wild-type transfection and those from the 1-to-1 cotransfection contained gp41TM signal (Fig. 6, lanes 2 and 3), though the band in the lane containing proteins from the 1-to-1 mixture was less intense (lane 3). In contrast, both the 9-to-1 cotransfection and Y36S-L41P samples did not contain a detectable band for gp41TM (lanes 4 and 5). Stripping and reacting this same blot with p24CA antiserum showed that nearly equivalent amounts of virus were present in all of the virus samples. These results demonstrate that this dominant negative effect reduces the ability of the wild-type Gag proteins to incorporate Env, as suggested by the infectivity results.

DISCUSSION

The results presented here show that all of the single-amino-acid mutations within the internal cleavage site and the hydrophobic tail of p6Gag inhibited cleavage yet had a minor effect on viral replication and infectivity. Therefore, protease processing at this site is not essential for virus infectivity. In fact, the Y36F mutant had decreased infectivity yet had the second-highest level of internal cleavage of the mutants, showing that internal cleavage of p6Gag and infectivity are not linked.

The basis for the Y36F mutant defect is currently unknown. The levels of virus released into the medium as determined by reverse transcriptase assay and immunoblotting do not appear to be significantly lower than those for the other mutants. Furthermore, immunoblot analysis for Env showed that this mutant incorporated amounts of Env similar to those incorporated by the wild type.

The observation that mutations distal to the protease site also inhibited the use of this site was unexpected since it is thought that the four amino and three carboxyl residues flanking the scissile bond fit into the protease substrate-binding pocket and most directly affect proteolysis (9, 27, 52, 57, 61). An explanation for these results is that the tertiary structure of p6Gag strongly influences this cleavage. However, structural studies of p6Gag produced in bacteria have failed to show any ordered structure, and in vitro studies have found that peptides containing this cleavage site as well as recombinant p6Gag protein itself are not cleaved by protease (56). Since p6Gag is first produced as a sequence within the Pr55Gag precursor, the ability of protease to cleave at this site may be determined more by structures adopted and interactions made during assembly and processing of the Gag polyprotein than by the primary sequence around the cleavage site.

Unlike the single-substitution mutants, the Y36S-L41P mutant was unable to infect cells because it did not incorporate significant amounts of Env. The inability to acquire the Env protein complex appears to be the only significant defect for this mutant since it could be rescued by pseudotyping with either VSV-G or MuLV Env. In some cases, the HCLZ assay did detect a very low amount of infectivity with the double mutant, raising the possibility that some Env was incorporated into the virion. This result could also be explained by rare Env-independent infection events arising from nonspecific virus-cell fusion. The results of the replication assays and the failure to isolate a revertant after attempts at long-term culturing of either transfected or infected H9 cells show that while these viruses might infect cells at a very low level, they fail to replicate at a detectable level.

The cotransfection experiments presented here demonstrated that this mutation acts in a trans-dominant negative fashion. This implies that the failure to incorporate Env is due to the presence of a sequence in p6Gag that blocks incorporation rather than the alternative, the loss of a p6Gag sequence that is required for Env incorporation. This interpretation is supported by a finding that truncation of the C-terminal tail of p6Gag has little effect on the incorporation of gp41TM into virions (45).

The mechanism for the exclusion of Env by the Y36S-L41P mutant is not clear. Studies using polarized cells have shown that the cytoplasmic tail of Env can influence the site of viral budding (36), suggesting a coordination of Env and Gag localization. Therefore, it is possible that the failure to incorporate Env into Y36S-L41P virions is due to an inability of the mutant Pr55Gag proteins to assemble in a region of the plasma membrane that contains HIV-1. However, several observations argue against this hypothesis. It has been shown that deletion of the C terminus of the gp41TM cytoplasmic tail causes HIV-1 to bud from both surfaces of polarized cells (36), indicating that this truncated Env no longer localizes to a specific region of the plasma membrane. Therefore, the inability of the Y36S-L41P mutant to incorporate the truncated Env suggests that a polarized budding phenomenon is not responsible for the Env packaging defect. Furthermore, recent experiments by Mammano et al. have shown that truncation of the cytoplasmic tail of HIV-1 Env allows it to be incorporated into MuLV (41). This result together with the fact that either MuLV Env or VSV-G can pseudotype both MuLV and HIV-1 shows that all of these glycoproteins, even if confined to a limited area, are present in a common region on the surface of the cell. Therefore, the differential ability to incorporate MuLV Env and VSV-G and not the HIV-1 full-length or truncated Env argues that the defect of the mutant is not due to an alteration of the site of budding. Finally, the trans-dominant negative effect of this mutant appears to be the result of an interaction between the mutant and wild-type Gags, most likely producing virions that contain mixtures of the two. This effect suggests that these Gags assemble and bud from similar regions of the cell.

Our data are consistent with a model in which the presence of the mutant p6Gag protein within the Gag precursor excludes HIV Env but not other Env proteins during assembly and budding. Some p17MA mutants appear to sterically block the long cytoplasmic tail of gp41TM from fitting into the immature budding virion at the cortical membrane-Gag interface (3, 11, 12, 23, 40, 51). The failure of Y36S-L41P mutant to package the truncated gp41TM demonstrates that the mechanism for this defect is different from that of the p17MA mutants. The location of p6Gag in assembling and budding virions is not known. However, given the current body of data, it is unlikely that the majority of p6Gag is present near the surface of the plasma membrane (16, 59). Thus, from our data as well as the established models of immature virion structure, it appears unlikely that this defect is due to p6Gag structurally blocking the insertion of Env into the virion at the cortical membrane as seems the case for the p17MA mutants.

While it is not clear how this mutant Gag excludes Env, it is important to appreciate that p6Gag is required for efficient budding, as it harbors the L domain for HIV-1 (18, 25, 47, 50). The mechanism for L-domain action is unknown, though in the case of avian viruses the L domain appears to interact with a cellular protein (15). A recent study by Garnier et al. (14) found that the entire p6Gag region within Pr55Gag is an important determinant of virus particle size. Taken together, these observations implicate p6Gag in the regulation of assembly and budding, possibly in conjunction with host proteins, by an unknown mechanism. While the mutations presented here do not affect the L domain proper, the Env incorporation defect identified here is likely to be linked to the role of p6Gag in assembly and budding, probably as a domain in Pr55Gag. Env could be excluded from the virion either directly by the mutant p6Gag during its role in assembly or by interfering with host proteins that might assist in this process.

These results identify a novel aspect in the role of p6Gag in HIV-1 assembly. Since relatively little is known about p6Gag, this observation may provide an important clue to its function.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jane Burns for the VSV-G expression construct; Robert Gorelick for the Mo10A1 clone; Bradley Kane for assistance with the mass spectrometry analysis; Conner McGrath for assistance with computer analysis; Douglas Schneider and Jeffery Rossio for the PHA-stimulated human PBMC; David Waters for the HCLZ cells; and Larry Arthur, Lou Henderson, and Alan Rein for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript.

This project was funded in whole or in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract NO1-CO-56000.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi A, Koenig S, Gendelman H E, Daugherty D, Gattoni-Celli S, Fauci A S, Martin M A. Productive, persistent infection of human colorectal cell lines with human immunodeficiency virus. J Virol. 1987;61:209–213. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.1.209-213.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aiken C. Pseudotyping human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) by the glycoprotein of vesicular stomatitis virus targets HIV-1 entry to an endocytic pathway and suppresses both the requirement for Nef and the sensitivity to cyclosporin A. J Virol. 1997;71:5871–5877. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.8.5871-5877.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barklis E, McDermott J, Wilkens S, Fuller S, Thompson D. Organization of HIV-1 capsid proteins on a lipid monolayer. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7177–7180. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.13.7177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bugelski P J, Maleeff B E, Klinkner A M, Ventre J, Hart T K. Ultrastructural evidence of an interaction between Env and Gag proteins during assembly of HIV type 1. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1995;11:55–64. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burns J C, Friedmann T, Driever W, Burrascano M, Yee J K. Vesicular stomatitis virus G glycoprotein pseudotyped retroviral vectors: concentration to very high titer and efficient gene transfer into mammalian and nonmammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8033–8037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.8033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coffin J, Hughes S, Varmus H. Retroviruses. Plainview, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Press; 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cosson P. Direct interaction between the envelope and matrix proteins of HIV-1. EMBO J. 1996;15:5783–5788. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Craven R, Parent L. Dynamic interactions of the Gag polyprotein. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1996;214:65–94. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-80145-7_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Darke P L, Nutt R F, Brady S F, Garsky V M, Ciccarone T M, Leu C T, Lumma P K, Freidinger R M, Veber D F, Sigal I S. HIV-1 protease specificity of peptide cleavage is sufficient for processing of gag and pol polyproteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;156:297–303. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)80839-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorfman T, Mammano F, Haseltine W A, Gottlinger H G. Role of the matrix protein in the virion association of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein. J Virol. 1994;68:1689–1696. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1689-1696.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freed E O, Martin M A. Domains of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix and gp41 cytoplasmic tail required for envelope incorporation into virions. J Virol. 1996;70:341–351. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.341-351.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freed E O, Martin M A. Virion incorporation of envelope glycoproteins with long but not short cytoplasmic tails is blocked by specific, single amino acid substitutions in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix. J Virol. 1995;69:1984–1989. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1984-1989.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freed E O, Orenstein J M, Buckler-White A J, Martin M A. Single amino acid changes in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix protein block virus particle production. J Virol. 1994;68:5311–5320. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.5311-5320.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garnier L, Ratner L, Rovinski B, Cao S X, Wills J W. Particle size determinants in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag protein. J Virol. 1998;72:4667–4677. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.4667-4677.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garnier L, Wills J W, Verderame M F, Sudol M. WW domains and retrovirus budding. Nature. 1996;381:744–745. doi: 10.1038/381744a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gelderblom H. Fine structure of HIV and SIV. Los Alamos, N.Mex: Los Alamos National Laboratory; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorelick R J, Nigida S M, Bess J W, Jr, Henderson L E, Arthur L O, Rein A. Noninfectious human immunodeficiency virus type 1 mutants deficient in genomic RNA. J Virol. 1990;64:3207–3211. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.7.3207-3211.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gottlinger H G, Dorfman T, Sodroski J G, Haseltine W A. Effect of mutations affecting the p6 gag protein on human immunodeficiency virus particle release. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3195–3199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henderson, L. Personal communication.

- 20.Henderson L E, Bowers M A, Sowder II R C, Serabyn S, Johnson D G, Bess J W, Jr, Arthur L O, Bryant D K, Fenselau C. Gag proteins of the highly replicative MN strain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: posttranslational modifications, proteolytic processings, and complete amino acid sequences. J Virol. 1992;66:1856–1865. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.1856-1865.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henderson L E, Copeland T D, Sowder R C, Schultz A M, Oroszlan S. Analysis of proteins and peptides purified from sucrose gradient banded HTLV-III. In: Bolognesi D, editor. Human retroviruses, cancer, and AIDS: approaches to prevention and therapy. New York, N.Y: Alan R. Liss Inc.; 1988. pp. 135–147. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henderson L E, Sowder II R C, Smythers G, Oroszlan S. Chemical and immunological characterizations of equine infectious anemia virus gag-encoded proteins. J Virol. 1988;61:2587–2595. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.4.1116-1124.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hill C P, Worthylake D, Bancroft D P, Christensen A M, Sundquist W I. Crystal structures of the trimeric human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix protein: implications for membrane association and assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3099–3104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.3099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horton R M, Cai Z, Ho S N, Pease L R. Gene splicing by overlap extension: tailor-made genes using polymerase chain reaction. BioTechniques. 1990;8:528–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang M, Orenstein J M, Martin M, Freed E O. p6Gag is required for particle production from full-length human immunodeficiency virus type 1 molecular clones expressing protease. J Virol. 1995;69:6810–6818. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6810-6818.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hunter E. Macromolecular interactions in the assembly of HIV and other retroviruses. Semin Virol. 1994;5:71–83. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jaskolski M, Tomasselli A G, Sawyer T K, Staples D G, Heinrikson R L, Schneider J, Kent S B, Wlodawer A. Structure at 2.5-A resolution of chemically synthesized human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease complexed with a hydroxyethylene-based inhibitor. Biochemistry. 1991;30:1600–1609. doi: 10.1021/bi00220a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaplan A H, Manchester M, Swanstrom R. The activity of the protease of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is initiated at the membrane of infected cells before the release of viral proteins and is required for release to occur with maximum efficiency. J Virol. 1994;68:6782–6786. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6782-6786.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaplan A H, Swanstrom R. HIV-1 gag proteins are processed in two cellular compartments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:4528–4532. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.10.4528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kimpton J, Emerman M. Detection of replication-competent and pseudotyped human immunodeficiency virus with a sensitive cell line on the basis of activation of an integrated β-galactosidase gene. J Virol. 1992;66:2232–2239. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.4.2232-2239.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kohl N E, Emini E A, Schleif W A, Davis L J, Heimbach J C, Dixion R A, Scolnick E M, Sigal I S. Active human immunodeficiency virus protease is required for viral infectivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:4686–4690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.13.4686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kondo E, Gottlinger H G. A conserved LXXLF sequence is the major determinant in p6Gag required for the incorporation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Vpr. J Virol. 1996;70:159–164. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.159-164.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kondo E, Mammano F, Cohen E, Gottlinger H G. The p6Gag domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is sufficient for the incorporation of Vpr into heterologous viral particles. J Virol. 1995;69:2759–2764. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.5.2759-2764.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kyte J, Doolittle R F. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J Mol Biol. 1982;157:105–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Landau N R, Page K A, Littman D R. Pseudotyping with human T-cell leukemia virus type I broadens the human immunodeficiency virus host range. J Virol. 1991;65:162–169. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.1.162-169.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lodge R, Gottlinger H, Gabuzda D, Cohen E A, Lemay G. The intracytoplasmic domain of gp41 mediates polarized budding of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in MDCK cells. J Virol. 1994;68:4857–4861. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.4857-4861.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu Y L, Bennett R P, Wills J W, Gorelick R, Ratner L. A leucine triplet repeat sequence (LXX)4 in p6Gag is important for Vpr incorporation into human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particles. J Virol. 1995;69:6873–6879. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6873-6879.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luo T, Douglas J L, Livingston R L, Garcia J V. Infectivity enhancement by HIV-1 Nef is dependent on the pathway of virus entry: implications for HIV-based gene transfer systems. Virology. 1998;241:224–233. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lusso P, di Marzo Veronese F, Ensoli B, Franchini G, Jemma C, DeRocco S E, Kalyanaraman V S, Gallo R C. Expanded HIV-1 cellular tropism by phenotypic mixing with murine endogenous retroviruses. Science. 1990;247:848–852. doi: 10.1126/science.2305256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mammano F, Kondo E, Sodroski J, Bukovsky A, Gottlinger H G. Rescue of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix protein mutants by envelope glycoproteins with short cytoplasmic domains. J Virol. 1995;69:3824–3830. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3824-3830.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mammano F, Salvatori F, Indraccolo S, De Rossi A, Chieco-Bianchi L, Gottlinger H G. Truncation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein allows efficient pseudotyping of Moloney murine leukemia virus particles and gene transfer into CD4+ cells. J Virol. 1997;71:3341–3345. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.3341-3345.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McClure M O, Marsh M, Weiss R A. Human immunodeficiency virus infection of CD4-bearing cells occurs by a pH-independent mechanism. EMBO J. 1988;7:513–518. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02839.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McClure M O, Sommerfelt M A, Marsh M, Weiss R A. The pH independence of mammalian retrovirus infection. J Gen Virol. 1990;71:767–773. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-4-767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Myers G, Korber B, Hahn B H, Jeang K-T, Mellors J W, McCutchan F E, Henderson L E, Pavlakis G N. Human retroviruses and AIDS 1995, a compilation and analysis of nucleic acid and amino acid sequences. Los Alamos, N.Mex: Los Alamos National Laboratory; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ott, D. Unpublished data.

- 46.Ott D E, Keller J, Sill K, Rein A. Phenotypes of murine leukemia virus-induced tumors: influence of 3′ viral coding sequences. J Virol. 1992;66:6107–6116. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.10.6107-6116.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parent L J, Bennett R P, Craven R C, Nelle T D, Krishna N K, Bowzard J B, Wilson C B, Puffer B A, Montelaro R C, Wills J W. Positionally independent and exchangeable late budding functions of the Rous sarcoma virus and human immunodeficiency virus Gag proteins. J Virol. 1995;69:5455–5460. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5455-5460.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park J, Morrow C D. The nonmyristylated Pr160gag-pol polyprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 interacts with Pr55gag and is incorporated into viruslike particles. J Virol. 1992;66:6304–6313. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.11.6304-6313.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Poorman R A, Tomasselli A G, Heinrikson R L, Kezdy F J. A cumulative specificity model for proteases from human immunodeficiency virus types 1 and 2, inferred from statistical analysis of an extended substrate data base. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:14554–14561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Puffer B A, Parent L J, Wills J W, Montelaro R C. Equine infectious anemia virus utilizes a YXXL motif within the late assembly domain of the Gag p9 protein. J Virol. 1997;71:6541–6546. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6541-6546.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rao Z, Belyaev A S, Fry E, Roy P, Jones I M, Stuart D I. Crystal structure of SIV matrix antigen and implications for virus assembly. Nature. 1995;378:743–747. doi: 10.1038/378743a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ridky T W, Cameron C E, Cameron J, Leis J, Copeland T, Wlodawer A, Weber I T, Harrison R W. Human immunodeficiency virus, type 1 protease substrate specificity is limited by interactions between substrate amino acids bound in adjacent enzyme subsites. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:4709–4717. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.9.4709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Spector D H, Wade E, Wright D A, Koval V, Clark C, Jaquish D, Spector S A. Human immunodeficiency virus pseudotypes with expanded cellular and species tropism. J Virol. 1990;64:2298–2308. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.5.2298-2308.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Srinivasakumar N, Hammarskjold M L, Rekosh D. Characterization of deletion mutations in the capsid region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 that affect particle formation and Gag-Pol precursor incorporation. J Virol. 1995;69:6106–6114. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.10.6106-6114.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stein B S, Gowda S D, Lifson J D, Penhallow R C, Bensch K G, Engleman E G. pH-independent HIV entry into CD4-positive T cells via virus envelope fusion to the plasma membrane. Cell. 1987;49:659–668. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90542-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stys D, Blaha I, Strop P. Structural and functional studies in vitro on the p6 protein from the HIV-1 gag open reading frame. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1182:157–161. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(93)90137-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Swanstrom R, Wills J. Synthesis, assembly, and processing of viral proteins. In: Coffin J, Hughes S, Varmus H, editors. Retroviruses. Plainview, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Press; 1997. pp. 263–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Trono D, Feinberg M B, Baltimore D. HIV-1 Gag mutants can dominantly interfere with the replication of the wild-type virus. Cell. 1989;59:113–120. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90874-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vogt V. Retroviruses. In: Coffin J, Hughes S, Varmus H, editors. Retroviruses. Plainview, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Press; 1997. pp. 27–70. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Weclewicz K, Ekstrom M, Kristensson K, Garoff H. Specific interactions between retrovirus Env and Gag proteins in rat neurons. J Virol. 1998;72:2832–2845. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2832-2845.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wlodawer A, Erickson J W. Structure-based inhibitors of HIV-1 protease. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:453–585. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.002551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yu X, Yuan X, Matsuda Z, Lee T H, Essex M. The matrix protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is required for incorporation of viral envelope protein into mature virions. J Virol. 1992;66:4966–4971. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.8.4966-4971.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zavada J. The pseudotypic paradox. J Gen Virol. 1982;63:15–24. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-63-1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]