Abstract

Background

To evaluate the role of ST‐segment resolution (STR) alone and in combination with Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) flow in reperfusion evaluation after primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) for ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction by investigating the long‐term prognostic impact.

Methods and Results

From January 2013 through September 2014, we studied 5966 patients with ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction enrolled in the CAMI (China Acute Myocardial Infarction) registry with available data of STR evaluated at 120 minutes after PPCI. Successful STR included STR ≥50% and complete STR (ST‐segment back to the equipotential line). After PPCI, the TIMI flow was assessed. The primary outcome was 2‐year all‐cause mortality. STR < 50%, STR ≥50%, and complete STR occurred in 20.6%, 64.3%, and 15.1% of patients, respectively. By multivariable analysis, STR ≥50% (5.6%; adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 0.45 [95% CI, 0.36–0.56]) and complete STR (5.1%; adjusted HR, 0.48 [95% CI, 0.34–0.67]) were significantly associated with lower 2‐year mortality than STR <50% (11.7%). Successful STR was an independent predictor of 2‐year mortality across the spectrum of clinical variables. After combining TIMI flow with STR, different 2‐year mortality was observed in subgroups, with the lowest in successful STR and TIMI 3 flow, intermediate when either of these measures was reduced, and highest when both were abnormal.

Conclusions

Post‐PPCI STR is a robust long‐term prognosticator for ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction, whereas the integrated analysis of STR plus TIMI flow yields incremental prognostic information beyond either measure alone, supporting it as a convenient and reliable surrogate end point for defining successful PPCI.

Registration

URL: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov; Unique identifier: NCT01874691.

Keywords: acute myocardial infarction, ECG, outcome, reperfusion

Subject Categories: Catheter-Based Coronary and Valvular Interventions

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CAMI

China Acute Myocardial Infarction

- IRA

infarct‐related artery

- PPCI

primary percutaneous coronary intervention

- STR

ST‐segment resolution

- TIMI

Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

The single‐lead ST‐segment resolution analyzed without core laboratories after primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction is a strong independent predictor of long‐term mortality in patients with a broad spectrum of clinical variables in the real‐world practice.

Approximately 20% of patients showed a discrepancy between Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction flow and ST‐segment resolution, which could be used to categorize them into 2 subgroups: those with optimal epicardial blood flow but microvascular dysfunction, and those with unsatisfactory initial recanalization but potential blood flow restoration at a later time.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

A combination of ST‐segment resolution ≥50% and Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 3 flow could be defined as successful primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction.

Rapid mechanical reperfusion by the primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) represents the pivotal step in the current management of ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), providing substantial prognostic benefits over fibrinolytic therapy. 1 However, there is still a guideline‐level lack of definition on successful PPCI. 2 , 3 Current diagnostic tools for myocardial reperfusion may be classified as invasive, such as intracoronary Doppler wire or angiography, or noninvasive, including ECG, myocardial contrast echocardiography, and cardiac magnetic resonance. 4 , 5 Because of the dynamic nature of myocardial reperfusion, 6 it is impractical for invasive indexes to reflect such a process, particularly outside the catheterization laboratory. In contrast, noninvasive tools could provide a more reproducible assessment of microcirculation; however, except for ECG, most of them are neither feasible in the short‐term nor cost‐efficient. 7

ST‐segment resolution (STR), the simplest tool for reflecting microvascular obstruction at the cellular level, 8 , 9 has been widely used as a surrogate end point in clinical trials evaluating reperfusion in STEMI. However, it has been questioned whether the impact of achieving STR on survival is robust in routine practice, given the conflicting results on its prognostic value have been reported in either randomized clinical trials or registry studies, probably attributable to inconstant methods and timing for ECG analysis. 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 In addition, despite reports of infrequent disagreement between STR and angiographic index, 11 , 17 , 18 , 22 , 23 , 24 it is unclear whether the combination of these indexes, which assess various aspects of microcirculatory integrity after reperfusion therapy, has additional long‐term prognostic value in a real‐world setting.

Using data derived from a large cohort of patients in the CAMI (China Acute Myocardial Infarction) registry, we sought to evaluate the long‐term prognostic value of STR alone and in combination with Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) flow after PPCI for STEMI.

METHODS

Overview of the CAMI Registry and Data Collection

The CAMI registry is a prospective, nationwide, multicenter, observational study for acute myocardial infarction (AMI) care in China. The study design has been described previously (NCT01874691). 25 , 26 In brief, we studied a total of 26 648 patients with acute myocardial infarction enrolled from 108 hospitals from 31 provinces and municipalities throughout mainland China between January 2013 and September 2014, with broad coverage of geographic regions, including urban and rural areas. These hospitals are the largest or central hospitals in their administrative areas (Data S1). 26 The CAMI registry was approved by the Ethics Committee of Fuwai Cardiovascular Hospital (No. 431). Written informed consent was obtained from eligible patients.

A comprehensive collection of data, including patient demographic factors, risk factors, medical history, reperfusion therapy, reasons for treatment plan, medications, procedures, and events, was conducted through a secure, web‐based electronic data capture system (Data S2). 26 All information was collected using a standardized set of variables and predefined, standard, unified definitions, systematic data entry and transmission procedures, and rigorous data quality control. Enrollment, data collection, and follow‐up were all performed by trained physicians at each participating site in a real‐time manner, to ensure data accuracy and reliability. Senior cardiologists were responsible for data quality control. Hospital sites underwent random on‐site audits for the accuracy of diagnosis and variables based on medical records. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Study Population and ECG Analysis

The present substudy was conducted in patients with STEMI with qualifying post‐PPCI ECGs. The final diagnosis of STEMI had to meet the third Universal Definition for Myocardial Infarction. 27 The qualifying ECGs should fulfill the following criteria: (1) ≥1 mm of ST‐segment elevation in at least 2 contiguous leads; and (2) without bundle‐branch block, ventricular pacing, or rhythm. STR was evaluated on the basis of ECGs acquired on admission and 120 minutes after PPCI in local participating hospitals, measuring in the single lead with the most prominent ST‐segment elevation on the baseline. Patients were categorized by the degree of STR: <50%, ≥50%, and complete STR (ie, ST‐segment elevation back to the equipotential line). Successful STR included STR ≥50% and complete STR.

Periprocedural Management

TIMI flow was used to evaluate reperfusion in the infarct‐related artery (IRA) at the end of the procedure. 28 The existence of macroscopic thrombosis in the IRA during the angiography was recorded by operators. The periprocedural use of antiplatelet agents (including aspirin, clopidogrel, and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors) and the use of parenteral anticoagulant during the procedure followed the STEMI guideline. 29

Outcomes

The primary clinical outcome was 2‐year all‐cause death. Follow‐up data were obtained by telephone interview, follow‐up letter, or clinic visit. All events were carefully checked and verified by an independent group of clinical physicians.

The secondary clinical outcome was in‐hospital major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events, including all‐cause death, reinfarction, and stroke.

Statistical Design and Analysis

Baseline characteristics and clinical outcomes for patients with different STR were compared. Continuous variables were expressed as mean±SD or median and interquartile range and were compared using the ANOVA or the Kruskal‐Wallis test. Categorical variables were expressed as numbers and percentages and were compared using the Pearson χ 2 test or the Fisher exact test. Survival curves were constructed by the Kaplan‐Meier method and compared by the log‐rank test. The adjusted associations between STR and 2‐year all‐cause mortality were examined by the development of the Cox proportional hazards regression model, which considered a group of baseline and procedural characteristics (ie, age, sex, hypertension, diabetes, history of myocardial infarction or stroke, symptom‐to‐balloon time, Killip class, cardiogenic shock, cardiac arrest, left ventricular ejection fraction, anterior infarction, and post‐PCI TIMI flow) as covariates. Subgroup analyses were performed by including an interaction term in the proportional hazards model.

Subsequently, 4 groups were identified, including successful STR and TIMI 3 flow, successful STR and TIMI 0 to 2 flow, STR <50% and TIMI 3 flow, and STR <50% and TIMI 0 to 2 flow.

Two‐sided P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

There were 5966 patients with STEMI treated with PPCI in the CAMI registry with data that could be evaluated for STR (Figure 1). Table S1 provides key baseline characteristics for all patients with STEMI with PPCI, the study cohort, and those excluded. Excluded subjects were more likely to have hyperlipidemia and a prior myocardial infarction history and less likely to receive PPCI within 12 hours after symptom onset. Included patients more frequently had single‐vessel disease, had thrombosis in IRA, and used glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors. Rates of 2‐year all‐cause death were similar among 3 groups (Figure S1).

Figure 1. A flowchart for subject selection.

AMI indicates acute myocardial infarction; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CAMI, China Acute Myocardial Infarction; NSTEMI, non–ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction; PPCI, primary percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction; and STR, ST‐segment resolution.

Baseline Characteristics

At 120 minutes after PPCI, STR <50%, STR ≥50%, and complete STR could be achieved in 1227 (20.6%), 3837 (64.3%), and 902 (15.1%) patients, respectively. As shown in Table 1, median age and sex did not differ significantly between the groups. Patients with STR <50% had more diabetes, Killip class ≥II, and anterior infarction compared with those with STR ≥50% and complete STR. There was no statistical difference in cardiogenic shock, cardiac arrest, and left ventricular ejection fraction among the 3 groups. A vast majority of the present cohort received periprocedural dual‐antiplatelet therapy and could achieve post‐PPCI TIMI 3 flow.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics and Clinical Outcomes According to STR

| Variable | STR <50% (n=1227) | STR ≥50% (n=3837) | Complete STR (n=902) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 60.5±11.8 | 60.4±11.8 | 59.8±11.8 | 0.222 |

| ≤60 y | 591/1227 (48.2) | 1828/3837 (47.6) | 440/902 (48.8) | 0.812 |

| Female sex | 253/1227 (20.6) | 739/3837 (19.3) | 195/902 (21.6) | 0.220 |

| Killip class ≥II | 258/1225 (21.1) | 710/3830 (18.5) | 109/898 (12.1) | <0.001 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 53/1226 (4.3) | 128/3830 (3.3) | 30/901 (3.3) | 0.086 |

| Cardiac arrest | 14/1224 (1.1) | 49/3828 (1.3) | 10/898 (1.1) | 0.879 |

| Current smoker | 618/1218 (50.7) | 1976/3811 (51.8) | 495/899 (55.1) | 0.596 |

| Hypertension | 595/1220 (48.8) | 1810/3820 (47.4) | 395/900 (43.9) | 0.148 |

| Diabetes | 250/1218 (20.5) | 683/3816 (17.9) | 124/898 (13.8) | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 71/1219 (5.8) | 262/3814 (6.9) | 78/899 (8.7) | 0.026 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 71/1219 (5.8) | 169/3816 (4.4) | 45/899 (5.0) | <0.001 |

| Prior stroke | 100/1218 (8.2) | 281/3814 (7.4) | 62/900 (6.9) | <0.001 |

| Creatinine clearance, mL/min | 86.6 (63.1–112.4) | 86.3 (63.6–110.2) | 86.8 (66.8–110.3) | 0.813 |

| Symptom‐to‐balloon time, h | 6.0 (4.0–10.8) | 5.7 (3.9–9.4) | 5.7 (3.8–8.8) | 0.075 |

| ≤12 h | 996/1210 (82.3) | 3344/3763 (88.9) | 811/896 (90.5) | <0.001 |

| Periprocedural antithrombotic therapy | ||||

| Aspirin | 1198/1223 (98.0) | 3772/3815 (98.9) | 888/898 (98.9) | 0.059 |

| Clopidogrel | 1202/1216 (98.8) | 3763/3792 (99.2) | 886/891 (99.4) | 0.297 |

| GPI | 489/1057 (46.3) | 1641/3597 (45.6) | 406/836 (48.6) | 0.307 |

| UFH | 929/1051 (88.4) | 3231/3581 (90.2) | 782/837 (93.4) | <0.001 |

| LMWH | 94/1051 (8.9) | 241/3581 (6.7) | 43/837 (5.1) | 0.004 |

| Bivalirudin | 14/1051 (1.3) | 60/3581 (1.7) | 4/837 (0.5) | 0.012 |

| LVEF, % | 52.6±9.7 | 53.9±10.0 | 54.7±10.4 | 0.054 |

| Single‐vessel disease | 377/1205 (31.1) | 1267/3683 (34.4) | 256/889 (28.8) | 0.002 |

| Anterior infarction | 653/1225 (53.3) | 1917/3813 (50.3) | 319/900 (35.4) | <0.001 |

| Thrombosis in IRA | 760/1224 (62.1) | 2497/3807 (65.6) | 581/895 (64.9) | 0.019 |

| Device of intervention | <0.001 | |||

| Thrombus aspiration | 45/1055 (4.3) | 102/3615 (2.8) | 35/836 (4.2) | |

| Only PTCA | 72/1055 (6.8) | 160/3615 (4.4) | 27/836 (3.2) | |

| Stent | 938/1055 (88.9) | 3353/3615 (92.8) | 774/836 (92.6) | |

| Post‐PCI TIMI flow | <0.001 | |||

| 0–2 | 85/1047 (8.1) | 145/3597 (4.0) | 34/836 (4.1) | |

| 3 | 962/1047 (91.9) | 3452/3597 (96.0) | 802/836 (95.9) | |

| MACCE during hospitalization | 92/1227 (7.5) | 112/3835 (2.9) | 21/902 (2.3) | <0.001 |

| All‐cause death | 84/1227 (6.8) | 74/3835 (1.9) | 15/902 (1.7) | <0.001 |

| Reinfarction | 7/1225 (0.6) | 18/3830 (0.5) | 4/900 (0.4) | 0.892 |

| Stroke | 7/1226 (0.6) | 30/3830 (0.8) | 3/901 (0.3) | 0.249 |

| 2‐y All‐cause death | 139/1185 (11.7) | 203/3637 (5.6) | 45/876 (5.1) | <0.001 |

Data are reported as mean±SD, number/total (percentage), or median (interquartile range). GPI indicates glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor; IRA, infarct‐related artery; LMWH, low‐molecular‐weight heparin; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MACCE, major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular event; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PTCA, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty; STR, ST‐segment resolution; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction; and UFH, unfractionated heparin.

Clinical Outcomes

The in‐hospital major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events were observed in 7.5% of the patients with STR <50%, compared with 1.9% and 1.7% of those in the STR ≥50% and complete STR group, respectively (P<0.001), which could be responsible for significantly higher mortality rate in patients with STR <50%.

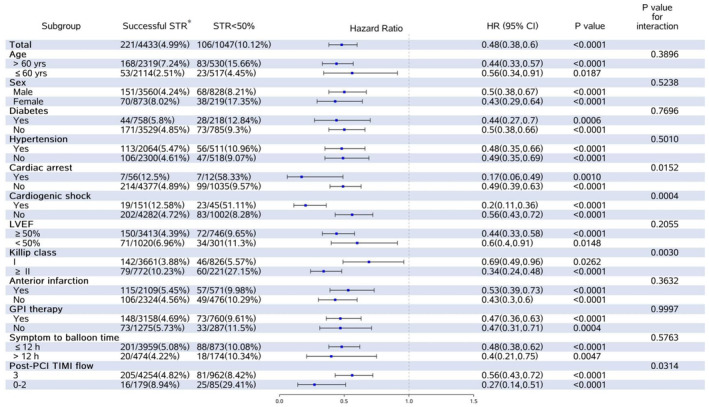

A complete clinical 2‐year follow‐up was obtained for 5698 patients (95.5%). The mortality rate was the highest in patients with STR <50% (11.7%), intermediate in patients with STR ≥50% (5.6%), and lowest in patients with complete STR (5.1%). From day 0, Kaplan‐Meier curves began to diverge for the all‐cause mortality in favor of STR >50% and complete STR for up to 2 years (Figure 2A). By multivariable analysis, both STR ≥50% (adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 0.45 [95% CI, 0.36–0.56]; P<0.001) and complete STR (adjusted HR, 0.48 [95% CI, 0.34–0.67]; P<0.001) were strongly associated with a reduced risk of 2‐year all‐cause mortality (Table 2). The adjusted HR and 95% CI of STR with respect to 2‐year mortality in the different subgroups of patients are shown in Figure 3. STR was an independent predictor of 2‐year mortality across all the spectrums of clinical variables.

Figure 2. Kaplan‐Meier curves for the 2‐year all‐cause mortality.

A, According to ST‐segment resolution (STR). B, According to concordant/discordant STR and Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) flow. Log‐rank test: P<0.001. Successful STR (SS) included STR ≥50% and complete STR.

Table 2.

Multivariate Predictors of 2‐Year All‐Cause Death

| Variable | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| STR ≥50% (vs STR <50%) | 0.45 (0.36–0.56) | <0.001 |

| Complete STR (vs STR <50%) | 0.48 (0.34–0.67) | <0.001 |

| Aged ≤60 y | 0.42 (0.33–0.54) | <0.001 |

| Female sex | 1.56 (1.25–1.94) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 1.21 (0.95–1.55) | 0.131 |

| Hypertension | 0.94 (0.77–1.16) | 0.584 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 1.18 (0.79–1.77) | 0.426 |

| Prior stroke | 1.58 (1.17–2.14) | 0.003 |

| Symptom‐to‐balloon time ≤12 h | 1.19 (0.87–1.61) | 0.279 |

| Killip class ≥II | 2.46 (1.97–3.07) | <0.001 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 2.29 (1.63–3.24) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac arrest | 2.31 (1.32–4.03) | 0.003 |

| LVEF ≥50% | 0.79 (0.63–0.99) | 0.039 |

| Anterior infarction | 1.10 (0.89–1.36) | 0.388 |

| Post‐PCI TIMI 3 flow | 0.16 (0.05–0.52) | 0.002 |

HR indicates hazard ratio; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STR, ST‐segment resolution; and TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

Figure 3. Unadjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for the 2‐year all‐cause mortality according to clinical or angiographic subgroups.

*Successful ST‐segment resolution (STR) included STR ≥50% and complete STR. GPI indicates glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; and PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Subgroup Analysis

Both STR and post‐PCI TIMI flow measures were available in 5480 patients (91.9%). A total of 4254 (77.6%), 179 (3.3%), 962 (17.6%), and 85 (1.5%) patients had successful STR and TIMI 3 flow (concordance), successful STR and TIMI 0 to 2 flow (discordance), STR <50% and TIMI 3 flow (discordance), and STR <50% and TIMI 0 to 2 flow (concordance), respectively. Thus, concordance between STR and TIMI flow occurred in 4339 of 5480 patients (79.2%), and discordance was present in 1141 of 5480 patients (20.8%). As shown in Table 3, among patients with TIMI 0 to 2 flow, the incidence of thrombosis in the IRA was 74.6% for successful STR and 69.4% for STR <50%, and the proportion of patients using the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors was 63.3% and 58.8%, respectively.

Table 3.

Baseline Characteristics According to Concordant/Discordant STR and TIMI Flow

| Characteristic | Successful STR*+TIMI 3 flow (n=4254) | Successful STR*+TIMI 0–2 flow (n=179) | STR <50%+TIMI 3 flow (n=962) | STR <50%+TIMI 0–2 flow (n=85) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 60.2±11.7 | 61.7±12.6 | 60.0±11.7 | 61.6±13.4 | 0.107 |

| ≤60 y | 2035/4254 (47.8) | 79/179 (44.1) | 484/962 (50.3) | 33/85 (38.8) | 0.108 |

| Female sex | 840/4254 (19.7) | 33/179 (18.4) | 202/962 (21.0) | 17/85 (20.0) | 0.795 |

| Killip class ≥II | 735/4247 (17.3) | 37/178 (20.8) | 193/961 (20.1) | 28/84 (33.3) | 0.001 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 142/4248 (3.3) | 9/178 (5.1) | 32/962 (3.3) | 13/84 (15.5) | 0.001 |

| Cardiac arrest | 53/4245 (1.2) | 3/177 (1.7) | 10/960 (1.0) | 2/84 (2.4) | 0.729 |

| Current smoker | 2248/4229 (53.2) | 71/178 (39.9) | 502/954 (52.6) | 33/85 (38.8) | 0.013 |

| Hypertension | 1987/4238 (46.9) | 77/178 (43.3) | 469/956 (49.1) | 42/85 (49.4) | 0.726 |

| Diabetes | 727/4233 (17.2) | 31/177 (17.5) | 205/954 (21.5) | 13/85 (15.3) | 0.040 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 302/4233 (7.1) | 15/177 (8.5) | 58/955 (6.1) | 4/85 (4.7) | 0.121 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 192/4234 (4.5) | 10/178 (5.6) | 51/955 (5.3) | 4/85 (4.7) | 0.441 |

| Prior stroke | 303/4232 (7.2) | 12/178 (6.7) | 75/954 (7.9) | 10/85 (11.8) | 0.046 |

| Creatinine clearance, mL/min | 87.0 (65.1–111.0) | 84.8 (64.4–105.3) | 90.6 (63.8–114.4) | 70.3 (47.8–91.2) | 0.815 |

| Symptom‐to‐balloon time, h | 5.7 (3.9–9.3) | 6.0 (4.5–9.5) | 6.2 (4.1–10.7) | 5.7 (3.7–11.8) | 0.711 |

| ≤12 h | 3725/4184 (89.0) | 162/177 (91.5) | 790/949 (83.2) | 70/85 (82.4) | <0.001 |

| Periprocedural antithrombotic therapy | |||||

| Aspirin | 4194/4236 (99.0) | 172/176 (97.7) | 939/958 (98.0) | 83/85 (97.6) | 0.049 |

| Clopidogrel | 4184/4208 (99.4) | 172/176 (97.7) | 942/951 (99.1) | 84/85 (98.8) | 0.112 |

| GPI | 1923/4233 (45.4) | 112/177 (63.3) | 435/961 (45.3) | 50/85 (58.8) | <0.001 |

| UFH | 3863/4216 (91.6) | 132/177 (74.6) | 859/955 (89.9) | 62/85 (72.9) | <0.001 |

| LMWH | 241/4216 (5.7) | 40/177 (22.6) | 71/955 (7.4) | 20/85 (23.5) | <0.001 |

| Bivalirudin | 62/4216 (1.5) | 1/177 (0.6) | 13/958 (98.2) | 1/85 (1.2) | 0.721 |

| LVEF, % | 54.0±9.9 | 53.1±11.6 | 52.6±9.3 | 51.7±9.3 | 0.248 |

| Single‐vessel disease | 1396/4113 (33.9) | 48/171 (28.1) | 309/945 (32.7) | 28/84 (33.3) | 0.397 |

| Anterior infarction | 2035/4237 (48.0) | 74/177 (41.8) | 524/961 (54.5) | 47/85 (55.3) | <0.001 |

| Thrombosis in IRA | 2802/4235 (66.2) | 132/177 (74.6) | 609/961 (63.4) | 59/85 (69.4) | 0.107 |

| Device of intervention | |||||

| Thrombus aspiration | 115/4242 (2.7) | 19/179 (10.6) | 34/959 (3.5) | 10/85 (11.8) | <0.001 |

| Only PTCA | 168/4242 (4.0) | 17/179 (9.5) | 55/959 (5.7) | 16/85 (18.8) | |

| Stent | 3959/4242 (93.3) | 143/179 (79.9) | 870/959 (90.7) | 59/85 (69.4) | |

Data are reported as mean±SD, number/total (percentage), or median (interquartile range). GPI indicates glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor; IRA, infarct‐related artery; LMWH, low‐molecular‐weight heparin; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; PTCA, percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty; STR, ST‐segment resolution; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction; and UFH, unfractionated heparin.

Successful STR included STR ≥50% and complete STR.

In the subgroup defined according to the post‐PCI TIMI flow shown in Figure 3, the risks of death at 2 years varied significantly according to the extent of STR. Among patients with TIMI 3 flow, successful STR was associated with lower 2‐year mortality than STR <50% (4.8% versus 8.4%; unadjusted HR, 0.56 [95% CI, 0.43–0.72]). Similarly, in the group of TIMI 0 to 2 flow, 2‐year mortality ranged from 8.9% in those with successful STR to 29.4% in those with STR <50% (unadjusted HR, 0.27 [95% CI, 0.14–0.51]; P for interaction=0.032).

DISCUSSION

We evaluated a large cohort of patients with STEMI focusing on the relationship between STR alone and in combination with TIMI flow after PPCI and long‐term survival. The principal findings included the following: (1) Successful STR occurred in ≈80% of patients and was associated with a substantial reduction in all‐cause mortality at 2 years compared with STR <50% after adjusting for potential clinical confounders. In addition, STR was an independent predictor of 2‐year mortality across a wide spectrum of clinical variables. (2) STR and TIMI flow were concordant in ≈80% of patients. Successful STR predicted lower risks of 2‐year mortality compared with STR <50% across different levels of TIMI flow, especially in TIMI 0 to 2 flow.

This study is the largest investigation to date about the long‐term prognostic value of STR in the contemporary, real‐world, clinical practice and further confirmed STR after PPCI was a reliable predictor of late survival. Although a group of studies has determined the prognostic significance of postprocedural STR in the current PPCI era, these results were derived from either randomized clinical trials, which were performed in a selected target population and using a core laboratory for ECG analysis (and thus might not be representative of real‐world clinical practice) 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ; or registry studies restricted to examining modest‐sized cohorts, 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 23 a single‐center design, 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 23 relatively short‐term follow‐up, 22 or preceded routine use of stent, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor, P2Y12 inhibitor, or statin, 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 therapies known to improve myocardial perfusion and to reduce epicardial reocclusion after PPCI. 30 The substudy of the APEX‐AMI (Assessment of Pexelizumab in Acute Myocardial Infarction) trial (n=4866), a randomized clinical trial to assess the efficacy of pexelizumab at day‐90 mortality, demonstrated that 6 STR methods measured in a core laboratory provided strong prognostic information on 90‐day clinical outcomes. 12 Our study extended this implication of the single‐lead STR obtained from multicenter clinician assessments in real‐world settings across different levels of hospitals for a longer follow‐up. The real‐world study of the Lombardima Registry (n=3403) showed that STR was associated with 30‐day mortality in patients with STEMI undergoing primary or facilitated PCI, except for those with post‐PCI TIMI 0 to 2 flow and nonanterior infarction. 22 We enrolled only PPCI‐treated patients and further confirmed that STR had a robust predictive value of long‐term mortality in a larger cohort across more subgroups, including post‐PCI TIMI flow and infarct location. Our results suggest the post‐PCI STR should be used routinely as a tool for assessing the efficacy of reperfusion therapy in the current PPCI era.

The finding of more patients who had diabetes, Killip class ≥II, prior myocardial infarction, and anterior infarction in the group of patients with STR <50% is consistent with earlier findings, 13 , 22 in which patients without STR tended to have the worse risk profile at baseline. After multivariable analysis including the above characteristics, either STR >50% or complete STR remained an independent predictor of 2‐year mortality, suggesting such comorbidities might not have impacted the prognostic value of STR.

Another clinically relevant finding of our study was that the assessment of both STR and TIMI flow, which reflect the different facets and pathophysiological processes of myocardial reperfusion, yields incremental long‐term prognostic information beyond either measure alone. As expected, patients with both STR ≥50% and TIMI 3 flow had the greatest survival, with >95% of patients still alive after 2 years. Conversely, the poorest survival was observed in patients with both STR <50% and TIMI 0 to 2 flow (29.4% 2‐year mortality, a 6.1‐fold increase; Figure 2B). Notably, the discordance between STR and TIMI flow in the present study (≈21%) represented the restoration of epicardial blood flow with microvascular dysfunction or unsatisfied initial recanalization with perhaps microcirculation restoration later. Previously, several small studies had highlighted a difference between TIMI flow and STR following PPCI (ranging from 24% to 36%). 17 , 18 , 22 , 23 However, these earlier studies only demonstrated that the absence of early STR after a successful PPCI procedure (TIMI flow ≥2) could indicate patients who are unlikely to benefit from the rapid restoration of flow in the IRA. Our study first demonstrated that among patients with TIMI 0 to 2 flow, approximately two‐thirds could achieve successful STR, with relatively benign outcomes with the incidence of the 2‐year mortality of 8.9% versus 29.4% in those with STR <50%. There was a significant interaction between STR and TIMI flow for long‐term mortality, showing that TIMI 0 to 2 flow was associated with better risk reduction in 2‐year mortality compared with TIMI 3 flow when the successful STR was attributed to both groups. Such a phenomenon might be explained by the subsequent restoration of blood flow caused by the periprocedural antiplatelet agents, 30 emphasizing the necessity for routinely evaluating STR after PPCI for all patients, and more aggressive antiplatelet therapy for those with obvious thrombus burden and temporary suboptimal patency in the IRA.

We evaluated the prognostic value of STR at a relatively late time with a large cohort of patients with PPCI in a real‐world registry. In the thrombolytic era, STR is determined 90 to 180 minutes after the start of treatment. 31 Compared with fibrinolysis, PPCI could lead to earlier patency of IRA, noted by the MONAMI (ST‐Monitoring in Acute Myocardial Infarction) study, which reported that most PPCI‐treated patients, whether high or low risk, could achieve complete STR within 90 minutes. 32 However, several studies have demonstrated that STR measured at 120 or even 180 minutes has a sufficient predictive value of adverse cardiovascular outcomes, 10 , 20 suggesting analysis of STR at a relatively late time would improve the sensitivity for identification of patients with complete STR. Immediate STR analysis for reperfusion evaluation could miss the dynamic efficacy of such antiplatelet therapy on the microcirculation. 33 , 34 Our results indicated that predicting long‐term survival in patients with STEMI by 120 minutes STR after PPCI was acceptable.

Along with the widespread acceptance that the optimal reperfusion should be redefined as the restoration of normal coronary blood flow with favorable microcirculation, 7 , 35 several indexes for assessing the myocardial infarction obtained from “myocardial blush,” intracoronary Doppler wire, and the tomographic or volumetric imaging techniques have been described. 4 , 5 However, none of them could be applied just as STR in clinical practice because of the limited operational repeatability or cost efficiency. Nevertheless, still, a part of STEMI trials assessed procedural success merely through the angiographic assessment, 36 , 37 and only the European Society of Cardiology guideline has recommended STR for assessing microvascular function after PPCI. 3 We support that STR, especially in combination with TIMI flow, deserves a higher priority for defining successful PPCI in future STEMI trials, which aim to investigate the efficacy of new periprocedural pharmacotherapy or other adjunctive therapy for further improving reperfusion success, and in routine practice, for identification of patients at different risks of long‐term mortality.

Some limitations to our study should be noted. First, data from the CAMI registry were collected nearly 10 years ago when the more potent antiplatelet agents with proven superior results, such as ticagrelor, 38 were rarely used in China. 39 In addition, there was a lack of uniform measurement standards for kinds of laboratory tests across different levels of Chinese hospitals during that era, particularly for myocardial infarction markers. Therefore, further studies with more up‐to‐date data are necessary. Second, the present study cannot address the issue about the optimal timing for STR measurement because we used static ECG rather than continuous ST‐segment monitoring. However, continuous ST monitoring is not widely available in clinical practice, which requires additional personnel and training and may be difficult to perform rapidly in acutely ill patients. 32 Third, the relatively small sample size with discordance between STR and TIMI flow should be noted as a caution in interpreting our data, and we could not provide a mechanistic explanation for the subsequent achievement of STR ≥50% in those with TIMI 0 to 2 flow. Fourth, the present results may not be applicable to other patients with STEMI with noninterpretable ST segments. Last, as a retrospective study, although several statistical adjustments were performed, we could not exclude the presence of unmeasured selection bias.

CONCLUSIONS

Single‐lead STR after PPCI is a reliable long‐term prognostic predictor in a real‐world setting for patients with STEMI across a wide spectrum of baseline characteristics. The integrated analysis of STR and TIMI flow after PPCI could provide complementary prognostic information for patients with STEMI during long‐term follow‐up and should be strongly encouraged for successful reperfusion evaluation in routine practice.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (2020‐I2M‐C&T‐B‐050) and the Twelfth Five‐Year Planning Project of the Scientific and Technological Department of China (2011BAI11B02). The funders had no role in the design of the study, data collection and analysis, or manuscript preparation.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Data S1–S2

Table S1

Figure S1

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: Jingang Yang and Chao Wu developed the research idea and designed the study; Quanmin Jing, Weimin Li, Haiyan Xu, Yongjia Wu, Fenghuan Hu, and Chen Jin collected data; Ling Li, Wenbo Zhang, Sidong Li, Yanyan Zhao, Yang Wang, and Wei Li were responsible for the data analysis; Chao Wu wrote the first draft of the article, which was reviewed by all authors. Xiaojin Gao, Shubin Qiao, and Yuejin Yang are the guarantors. The corresponding authors attest that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

This article was sent to Jennifer Tremmel, MD, Associate Editor, for review by expert referees, editorial decision, and final disposition.

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.123.029670

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 10.

Contributor Information

Jingang Yang, Email: jingangyang@126.com.

Yuejin Yang, Email: yangyjfw@126.com.

References

- 1. Keeley EC, Boura JA, Grines CL. Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomised trials. Lancet. 2003;361:13–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12113-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE Jr, Chung MK, de Lemos JA, Ettinger SM, Fang JC, Fesmire FM, Franklin BA, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST‐elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;127:e362–e425. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182742cf6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli‐Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, Crea F, Goudevenos JA, Halvorsen S, et al. 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST‐segment elevation: the Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST‐segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2017;39:119–177. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Niccoli G, Scalone G, Lerman A, Crea F. Coronary microvascular obstruction in acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:1024–1033. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Niccoli G, Burzotta F, Galiuto L, Crea F. Myocardial no‐reflow in humans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:281–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.03.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Galiuto G, Gabrielli FA, Lombardo A, La Torre G, Scarà A, Rebuzzi AG, Crea F. Reversible microvascular dysfunction coupled with persistent myocardial dysfunction: implications for post‐infarct left ventricular remodelling. Heart. 2007;93:565–571. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.091538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McCartney PJ, Berry C. Redefining successful primary PCI. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;20:133–135. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jey159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kléber AG. ST‐segment elevation in the electrocardiogram: a sign of myocardial ischemia. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;45:111–118. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(99)00301-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schröder R. Prognostic impact of early ST‐segment resolution in acute ST‐elevation myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2004;110(21):e506–e510. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000147778.05979.E6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Berrocal DH, Cohen MG, Spinetta AD, Ben MG, Rojas Matas CA, Gabay JM, Magni JM, Nogareda G, Oberti P, Von Schulz C, et al. Early reperfusion and late clinical outcomes in patients presenting with acute myocardial infarction randomly assigned to primary percutaneous coronary intervention or streptokinase. Am Heart J. 2003;146:E22–E1082. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(03)00424-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McLaughlin MG, Stone GW, Aymong E, Gardner G, Mehran R, Lansky AJ, Grines CL, Tcheng JE, Cox DA, Stuckey T, et al. Prognostic utility of comparative methods for assessment of ST‐segment resolution after primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction: the Controlled Abciximab and Device Investigation to Lower Late Angioplasty Complications (CADILLAC) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1215–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Buller CE, Fu Y, Mahaffey KW, Todaro TG, Adams P, Westerhout CM, White HD, van't Hof AW, Van de Werf FJ, Wagner GS, et al. ST‐segment recovery and outcome after primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST‐elevation myocardial infarction: insights from the Assessment of Pexelizumab in Acute Myocardial Infarction (APEX‐AMI) trial. Circulation. 2008;118:1335–1346. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.767772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sejersten M, Valeur N, Grande P, Nielsen TT, Clemmensen P; DANAMI‐2 Investigators . Long‐term prognostic value of ST‐segment resolution in patients treated with fibrinolysis or primary percutaneous coronary intervention results from the DANAMI‐2 (DANish trial in acute myocardial infarction‐2). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1763–1769. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.03.084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Farkouh ME, Reiffel J, Dressler O, Nikolsky E, Parise H, Cristea E, Baran DA, Dizon J, Merab JP, Lansky AJ, et al. Relationship between ST‐segment recovery and clinical outcomes after primary percutaneous coronary intervention: the HORIZONS‐AMI ECG substudy report. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:216–223. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.112.000142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Spitaleri G, Brugaletta S, Scalone G, Moscarella E, Ortega‐Paz L, Pernigotti A, Gomez‐Lara J, Cequier A, Iñiguez A, Serra A, et al. Role of ST‐segment resolution in patients with ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention (from the 5‐year outcomes of the EXAMINATION [Evaluation of the Xience‐V Stent in Acute Myocardial Infarction] trial). Am J Cardiol. 2018;121:1039–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fabris E, van't Hof A, Hamm CW, Lapostolle F, Lassen JF, Goodman SG, Ten Berg JM, Bolognese L, Cequier A, Chettibi M, et al. Clinical impact and predictors of complete ST segment resolution after primary percutaneous coronary intervention: a subanalysis of the ATLANTIC Trial. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2017;8:208–217. doi: 10.1177/2048872617727722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Claeys MJ, Bosmans J, Veenstra L, Jorens P, De Raedt H, Vrints CJ. Determinants and prognostic implications of persistent ST‐segment elevation after primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction: importance of microvascular reperfusion injury on clinical outcome. Circulation. 1999;99:1972–1977. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.99.15.1972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Matetzky S, Novikov M, Gruberg L, Freimark D, Feinberg M, Elian D, Novikov I, Di Segni E, Agranat O, Har‐Zahav Y, et al. The significance of persistent ST elevation versus early resolution of ST segment elevation after primary PTCA. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:1932–1938. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(99)00466-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brodie BR, Stuckey TD, Hansen C, VerSteeg DS, Muncy DB, Moore S, Gupta N, Downey WE. Relation between electrocardiographic ST‐segment resolution and early and late outcomes after primary percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:343–348. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.09.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. De Luca G, Suryapranata H, Ottervanger JP, Hoorntje JC, Gosselink AT, Dambrink JH, de Boer MJ, van't Hof AW. Postprocedural single‐lead ST‐segment deviation and long‐term mortality in patients with ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction treated by primary angioplasty. Heart. 2008;94:44–47. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.103556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kumar S, Sivagangabalan G, Hsieh C, Ryding AD, Narayan A, Chan H, Burgess DC, Ong AT, Sadick N, Kovoor P. Predictive value of ST resolution analysis performed immediately versus at ninety minutes after primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:467–474. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Palmerini T, De Servi S, Politi A, Martinoni A, Musumeci G, Ettori F, Piccaluga E, Sangiorgi D, Lauria G, Repetto A, et al. Prognostic implications of ST‐segment elevation resolution in patients with ST‐segment elevation acute myocardial infarction treated with primary or facilitated percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:605–610. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.10.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tomaszuk‐Kazberuk A, Kozuch M, Bachorzewska‐Gajewska H, Malyszko J, Dobrzycki S, Musial WJ. Does lack of ST‐segment resolution still have prognostic value 6 years after an acute myocardial infarction treated with coronary intervention? Can J Cardiol. 2011;27:573–580. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2011.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shah A, Wagner GS, Granger CB, O'Connor CM, Green CL, Trollinger KM, Califf RM, Krucoff MW. Prognostic implications of TIMI flow grade in the infarct related artery compared with continuous 12‐lead ST‐segment resolution analysis. Reexamining the "gold standard" for myocardial reperfusion assessment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:666–672. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(99)00601-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Xu H, Li W, Yang J, Wiviott SD, Sabatine MS, Peterson ED, Xian Y, Roe MT, Zhao W, Wang Y, et al. The China Acute Myocardial Infarction (CAMI) Registry: a national long‐term registry‐research‐education integrated platform for exploring acute myocardial infarction in China. Am Heart J. 2016;175:193–201.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Xu H, Yang Y, Wang C, Yang J, Li W, Zhang X, Ye Y, Dong Q, Fu R, Sun H, et al. Association of hospital‐level differences in care with outcomes among patients with acute ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction in China. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2021677. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.21677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Simoons ML, Chaitman BR, White HD; Writing group on behalf of the Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Glob Heart. 2012;7:275–295. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2012.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. TIMI Study Group . The Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) trial. Phase I findings. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:932–936. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198504043121437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chinese Society of Cardiology of Chinese Medical Association . 2010 Chinese Society of Cardiology (CSC) guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction. Chin J Cardiol. 2010;38:675–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kleinbongard P, Heusch G. A fresh look at coronary microembolization. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2022;19:265–280. doi: 10.1038/s41569-021-00632-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. de Lemos JA, Braunwald E. ST segment resolution as a tool for assessing the efficacy of reperfusion therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:1283–1294. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01550-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Terkelsen CJ, Nørgaard BL, Lassen JF, Poulsen SH, Gerdes JC, Sloth E, Gøtzsche LB, Rømer FK, Thuesen L, Nielsen TT, et al. Potential significance of spontaneous and interventional ST‐changes in patients transferred for primary percutaneous coronary intervention: observations from the ST‐MONitoring in Acute Myocardial Infarction study (the MONAMI study). Eur Heart J. 2006;27:267–275. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ernst NM, Suryapranata H, Miedema K, Slingerland RJ, Ottervanger JP, Hoorntje JC, Gosselink AT, Dambrink JH, de Boer MJ, Zijlstra F, et al. Achieved platelet aggregation inhibition after different antiplatelet regimens during percutaneous coronary intervention for ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1187–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.06.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hochholzer W, Trenk D, Frundi D, Blanke P, Fischer B, Andris K, Bestehorn HP, Büttner HJ, Neumann FJ. Time dependence of platelet inhibition after a 600‐mg loading dose of clopidogrel in a large, unselected cohort of candidates for percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2005;111:2560–2564. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000160869.75810.98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Roe MT, Ohman EM, Maas AC, Christenson RH, Mahaffey KW, Granger CB, Harrington RA, Califf RM, Krucoff MW. Shifting the open‐artery hypothesis downstream: the quest for optimal reperfusion. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:9–18. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(00)01101-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kim JS, Park SM, Kim BK, Ko YG, Choi D, Hong MK, Seong IW, Kim BO, Gwon HC, Hong BK, et al. Efficacy of clotinab in acute myocardial infarction trial‐ST elevation myocardial infarction (ECLAT‐STEMI). Circ J. 2012;76:405–413. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-11-0676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Han YL, Liu JN, Jing QM, Ma YY, Jiang TM, Pu K, Zhao RP, Zhao X, Liu HW, Xu K, et al. The efficacy and safety of pharmacoinvasive therapy with prourokinase for acute ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction patients with expected long percutaneous coronary intervention‐related delay. Cardiovasc Ther. 2013;31:285–290. doi: 10.1111/1755-5922.12020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, Cannon CP, Emanuelsson H, Held C, Horrow J, Husted S, James S, Katus H, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1045–1057. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Working Group on Coronary Artery Disease; National Center for Cardiovascular Quality Improvement . Clinical performance and quality measures for adults with acute ST‐elevation myocardial infarction in China. Chin Circ J. 2019;2020(35):313–325. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1–S2

Table S1

Figure S1