| Posicionamento sobre Doença Isquêmica do Coração – A Mulher no Centro do Cuidado – 2023 | |

|---|---|

| O relatório abaixo lista as declarações de interesse conforme relatadas à SBC pelos especialistas durante o período de desenvolvimento deste posicionamento, 2022/2023. | |

| Especialista | Tipo de relacionamento com a indústria |

| Alexandre Jorge Gomes de Lucena | Declaração financeira A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Cardiopapers; Afya. |

| André Luiz Cerqueira de Almeida | Declaração financeira A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Boston Scientific: Palestrante Prótese. |

| Andréa Araujo Brandão | Declaração financeira A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Servier: Triplixan; Daiichi Sankyo: Benicar; Libbs: Venzer. B - Financiamento de pesquisas sob sua responsabilidade direta/pessoal (direcionado ao departamento ou instituição) provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras. - Servier: Hipertensão Arterial. Outros relacionamentos Financiamento de atividades de educação médica continuada, incluindo viagens, hospedagens e inscrições para congressos e cursos, provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Servier: Hipertensão Arterial. |

| Andrea Dumsch de Aragon Ferreira | Nada a ser declarado |

| Andreia Biolo | Declaração financeira B - Financiamento de pesquisas sob sua responsabilidade direta/pessoal (direcionado ao departamento ou instituição) provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras. - Alnylam Pharmaceuticals: Amiloidose. |

| Antonio Carlos Palandri Chagas | Declaração financeira A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Novo Nordisk; Viatris; Instituto Vita Nova. Outros relacionamentos Financiamento de atividades de educação médica continuada, incluindo viagens, hospedagens e inscrições para congressos e cursos, provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Novo Nordisk. |

| Ariane Vieira Scarlatelli Macedo | Declaração financeira A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Bayer: Anticoagulação e insuficiência cardíaca; Pfizer: Anticoagulação e amiloidose; Jannsen: Leucemia. Outros relacionamentos Financiamento de atividades de educação médica continuada, incluindo viagens, hospedagens e inscrições para congressos e cursos, provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Bayer: Insuficiência cardíaca. |

| Breno de Alencar Araripe Falcão | Declaração financeira A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Edwards Lifescience: Proctor de TAVI e TMVR; Medtronic: Proctor de TAVI; Boston Scientific: Proctor de CTO PCI. |

| Carisi Anne Polanczyk | Nada a ser declarado |

| Carla Janice Baister Lantieri | Nada a ser declarado |

| Celi Marques-Santos | Nada a ser declarado |

| Claudia Maria Vilas Freire | Nada a ser declarado |

| Daniela do Carmo Rassi | Nada a ser declarado |

| Denise Pellegrini | Nada a ser declarado |

| Elizabeth Regina Giunco Alexandre | Declaração financeira A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Lilly: Trulicity, Jardiance, Glyxambi. Outros relacionamentos Financiamento de atividades de educação médica continuada, incluindo viagens, hospedagens e inscrições para congressos e cursos, provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Novo Nordisk: Ozempic. |

| Érika Olivier Vilela Bragança | Nada a ser declarado |

| Fabiana Goulart Marcondes Braga | Declaração financeira A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Novartis: Palestras; AstraZeneca: Palestras e Conselho Consultivo; Boehringer: Conselho Consultivo. |

| Fabiana Michelle Feitosa de Oliveira | Nada a ser declarado |

| Fatima Dumas Cintra | Nada a ser declarado |

| Gláucia Maria Moraes de Oliveira | Nada a ser declarado |

| Isabela Bispo Santos da Silva Costa | Nada a ser declarado |

| José Sérgio Nascimento Silva | Nada a ser declarado |

| Lara Terra F. Carreira | Nada a ser declarado |

| Lidia Zytynski Moura | Declaração financeira A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Novartis: Entresto; AstraZeneca: Forxiga; Boehringer: Jardiance; Bayer: Vericiguat; Vifor: Ferrinject. B - Financiamento de pesquisas sob sua responsabilidade direta/pessoal (direcionado ao departamento ou instituição) provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras. - Bayer: Vericiguat. |

| Lucelia Batista Neves Cunha Magalhães | Nada a ser declarado |

| Luciana Diniz Nagem Janot de Matos | Nada a ser declarado |

| Magaly Arrais | Declaração financeira A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Edwards / Boston: Implante transcateter valvar; Medtronic: Implante. |

| Marcelo Heitor Vieira Assad | Declaração financeira A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Novo Nordisk: Semaglutida; AstraZeneca: Dapagliflozina; BI: Empagliflozina; GSK: Shingrix; Biolab: Evolucumabe; Daiichi Sankyo: Benicar Triplo; Novartis: Dislipidemia. B - Financiamento de pesquisas sob sua responsabilidade direta/pessoal (direcionado ao departamento ou instituição) provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras. - Amgen: LP(A). Outros relacionamentos Financiamento de atividades de educação médica continuada, incluindo viagens, hospedagens e inscrições para congressos e cursos, provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Novo Nordisk: Semaglutina; BI: Empagliglozina. |

| Marcia M. Barbosa | Nada a ser declarado |

| Marconi Gomes da Silva | Nada a ser declarado |

| Maria Alayde Mendonça Rivera | Nada a ser declarado |

| Maria Cristina Costa de Almeida | Nada a ser declarado |

| Maria Cristina de Oliveira Izar | Declaração financeira A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Amgen: Repatha; Amryt Pharma: Lojuxta; AstraZeneca: Dapagliflozina; Aché: Trezor, Trezete; Biolab: Livalo; Abbott: Lipidil; EMS: Rosuvastatina; Eurofarma: Rosuvastatina; Sanofi: Praluent, Zympass, Zympass Eze, Efluelda; Libbs: Plenance, Plenance Eze; Novo Nordisk: Ozempic, Victoza; Servier: Acertamlo, Alertalix; PTCBio: Waylivra. B - Financiamento de pesquisas sob sua responsabilidade direta/pessoal (direcionado ao departamento ou instituição) provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras. - PTCBio: Waylivra; Amgen: Repatha; Novartis: Inclisiran, Pelacarsen; NovoNordisk: Ziltivekimab. Outros relacionamentos Financiamento de atividades de educação médica continuada, incluindo viagens, hospedagens e inscrições para congressos e cursos, provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Novo Nordisk: Diabetes. |

| Maria Elizabeth Navegantes Caetano Costa | Declaração financeira A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Libbs: Plenance Enze; Servier: Vastarel. Outros relacionamentos Financiamento de atividades de educação médica continuada, incluindo viagens, hospedagens e inscrições para congressos e cursos, provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Libbs; Servier: Participação em congresso. |

| Maria Sanali Moura de Oliveira Paiva | Nada a ser declarado |

| Marildes Luiza de Castro | Declaração financeira A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - AstraZeneca: Forxiga/Insuficiência cardíaca; Servier: Acertil/Hipertensão arterial. |

| Marly Uellendahl | Declaração financeira A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - GE/Healthcare: Palestras e treinamentos na área de Ressonância Magnética Cardiovascular. |

| Milena dos Santos Barros Campos | Nada a ser declarado |

| Mucio Tavares de Oliveira Junior | Declaração financeira A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Sanofi/Pasteur: Vacinas; AstraZeneca / Boehringer Ingelheim / Merck: palestras; Novo Nordisk: Conselho consultivo. |

| Olga Ferreira de Souza | Outros relacionamentos Financiamento de atividades de educação médica continuada, incluindo viagens, hospedagens e inscrições para congressos e cursos, provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Daiichi Sankyo. |

| Ricardo Alves da Costa | Nada a ser declarado |

| Ricardo Quental Coutinho | Nada a ser declarado |

| Sheyla Cristina Tonheiro Ferro da Silva | Declaração financeira A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Palestras para Novartis: Entresto; AstraZeneca: Forxiga/ Xigduo; aliaça Boeringher-Lilly: Jardiance; Servier: Acertil, Acertalix, triplixan; Novonordisk: Saxenda, Ozempic, Rybelsus; Libbis: Naprix; Vifor: Ferinject. Outros relacionamentos Financiamento de atividades de educação médica continuada, incluindo viagens, hospedagens e inscrições para congressos e cursos, provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Aliança Boeringher-Lilly: Jardiance; Novonordisk: Ozempic, Rybelsus, Saxenda; Servier: Acertil, Acertalix, Triplixan. |

| Sílvia Marinho Martins | Nada a ser declarado |

| Simone Cristina Soares Brandão | Nada a ser declarado |

| Susimeire Buglia | Nada a ser declarado |

| Tatiana Maia Jorge de Ulhôa Barbosa | Nada a ser declarado |

| Thais Aguiar do Nascimento | Declaração financeira A - Pagamento de qualquer espécie e desde que economicamente apreciáveis, feitos a (i) você, (ii) ao seu cônjuge/ companheiro ou a qualquer outro membro que resida com você, (iii) a qualquer pessoa jurídica em que qualquer destes seja controlador, sócio, acionista ou participante, de forma direta ou indireta, recebimento por palestras, aulas, atuação como proctor de treinamentos, remunerações, honorários pagos por participações em conselhos consultivos, de investigadores, ou outros comitês, etc. Provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Abbott: Consultoria. |

| Thais Vieira | Outros relacionamentos Financiamento de atividades de educação médica continuada, incluindo viagens, hospedagens e inscrições para congressos e cursos, provenientes da indústria farmacêutica, de órteses, próteses, equipamentos e implantes, brasileiras ou estrangeiras: - Boehringer / AstraZeneca / Torrent / Novo Nordisk: Palestrante. |

| Valquíria Pelisser Campagnucci | Nada a ser declarado |

| Viviana Guzzo Lemke | Nada a ser declarado |

| Walkiria Samuel Avila | Nada a ser declarado |

Sumário

1. Introdução/Highlights 11

1.1. Introdução 12

1.2 Destaques deste Posicionamento 12

1.2.1. Epidemiologia 12

1.2.2. Bases Fisiopatológicas da Doença Aterotrombótica 12

1.2.3. Apresentação Clínica, Diagnóstico e Tratamento Clínico 12

1.2.4. Diagnóstico por Avaliação Funcional Gráfica 13

1.2.5. Diagnóstico por Imagem Cardiovascular Não Invasiva 13

1.2.6. Arritmias na Cardiopatia Isquêmica 13

1.2.7. Aterotrombose na Gravidez, Contracepção, Infertilidade, Síndrome Antifosfolípide 14

1.2.8. Cardiomiopatia Isquêmica 14

1.2.9. Intervenção Coronariana Percutânea 14

1.2.10. Revascularização Miocárdica e Transplante Cardíaco 14

1.2.11. Reabilitação na Cardiomiopatia Isquêmica 15

2. Epidemiologia da Doença Isquêmica do Coração nas Mulheres 15

2.1. Introdução 15

2.2. Mortalidade 15

2.3. Prevalência e Incidência 18

2.4. Carga de Doenças 21

2.5. Fatores de Risco 21

2.6. Conclusão 22

3. Bases Fisiopatológicas da Doença Aterotrombótica 23

3.1. Introdução 23

3.2. Ruptura de Placa 23

3.3. Dissecção Espontânea de Coronária 23

3.4. Espasmo Coronariano 24

3.5. Disfunção Microvascular Coronariana 24

3.6. Embolia e Trombose 24

3.7. Síndrome de Takotsubo 24

3.8. Miocardite 24

4. Apresentação Clínica, Diagnóstico e Tratamento Clínico 25

4.1. Dor Torácica de Etiologia Isquêmica 25

4.2. Fatores de Risco Estabelecidos e Modificáveis 26

4.3. Fatores de Risco Estabelecidos e Não Modificáveis 27

4.4. Fatores de Risco Específicos da Mulher 27

4.5. Fatores de Risco Sub-reconhecidos 28

4.5.1. Recomendações 28

4.6. Tratamento Medicamentoso nas Diferentes Formas de Manifestação Isquêmica 28

4.6.1. Recomendações 29

5. Diagnóstico por Avaliação Funcional Gráfica 29

5.1. Eletrocardiograma de Repouso 29

5.2. Teste Ergométrico 29

5.2.1. Recomendações 30

5.3. Teste Cardiopulmonar de Exercício 30

6. Diagnóstico por Imagem Cardiovascular Não Invasiva 32

6.1. Introdução 32

6.2. Ecocardiograma de Repouso e sob Estresse 32

6.3. Ultrassonografia Vascular 33

6.4. Tomografia Computadorizada 34

6.5. Ressonância Magnética Cardíaca 34

6.6. Medicina Nuclear 35

7. Arritmias na Cardiomiopatia Isquêmica 36

7.1. Fibrilação Atrial e Doença Isquêmica do Coração 36

7.2. Arritmias Ventriculares: Morte Súbita, Prevenção e Tratamento 37

7.3. Terapia de Ressincronização Cardíaca 39

7.4. Recomendações 40

8. Aterotrombose na Gravidez, Contracepção, Infertilidade, Síndrome Antifosfolípide 41

8.1. Introdução 41

8.2. Período da Gravidez 41

8.3. Contracepção 41

8.3.1. Recomendações 44

8.4. Infertilidade 44

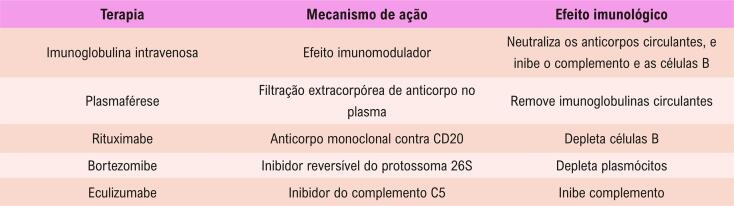

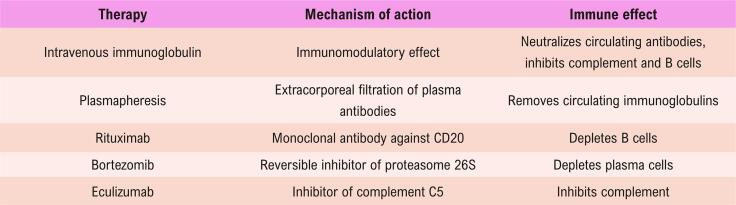

8.5. Síndrome Antifosfolípide 45

8.5.1. Recomendações 47

9. Cardiomiopatia Isquêmica na Mulher 47

9.1. Introdução 47

9.2. Tratamento Clínico 48

9.3. Dispositivos e Insuficiência Cardíaca Avançada 48

9.4. Cardiodesfibrilador Implantável 51

9.5. Insuficiência Cardíaca Avançada 51

9.6. Recomendações 51

9.6.1. Manejo Clínico e Indicações de Terapias Avançadas 51

10. Intervenção Coronariana Percutânea 51

10.1. Introdução 51

10.2. Acesso Vascular para o Cateterismo Cardíaco e Intervenção Coronariana Percutânea em Mulheres 51

10.3. Diagnóstico 52

10.3.1. Angiografia Coronária 52

10.3.2. Imagem Intravascular 52

10.3.3. Testes Invasivos com Guia de Medição 53

10.3.3.1. Reserva de Fluxo Fracionada 53

10.3.3.2. Razão de Pressão Instantânea Livre de Onda 53

10.3.4. Testes Funcionais 53

10.4. Tratamento Percutâneo da Doença Aterotrombótica Coronária em Mulheres 54

10.4.1. Revascularização para Síndromes Coronarianas Crônicas 54

10.4.1.1. Doença do Tronco de Coronária Esquerda 55

10.4.1.2. Oclusão Total Crônica 55

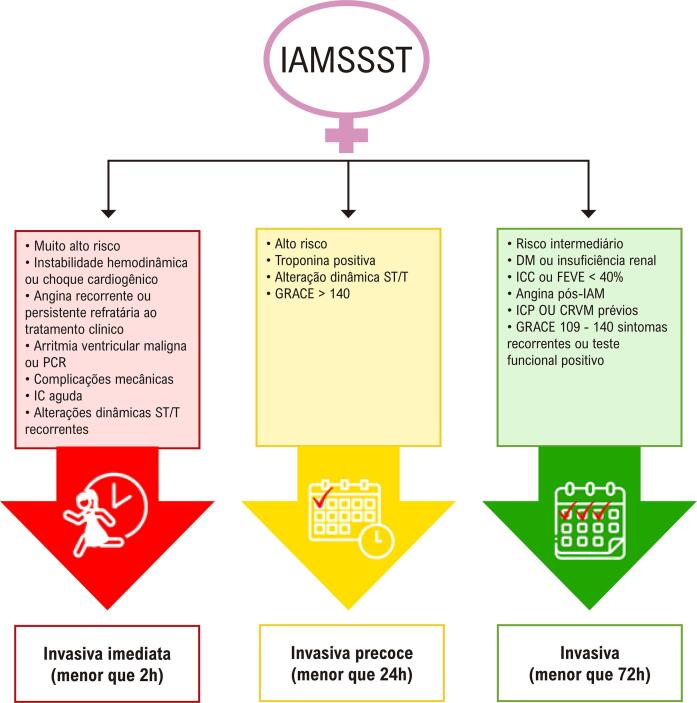

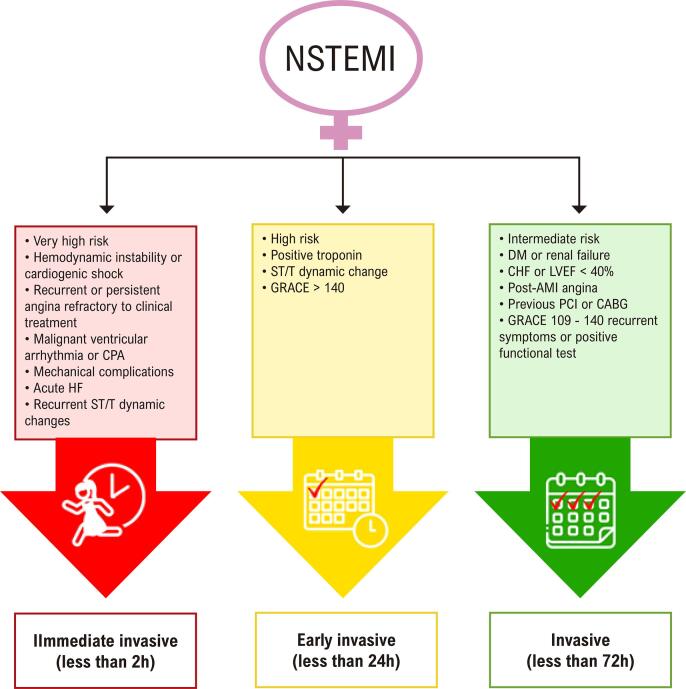

10.4.2. Revascularização para Infarto do Miocárdio sem Supradesnivelamento do Segmento ST 55

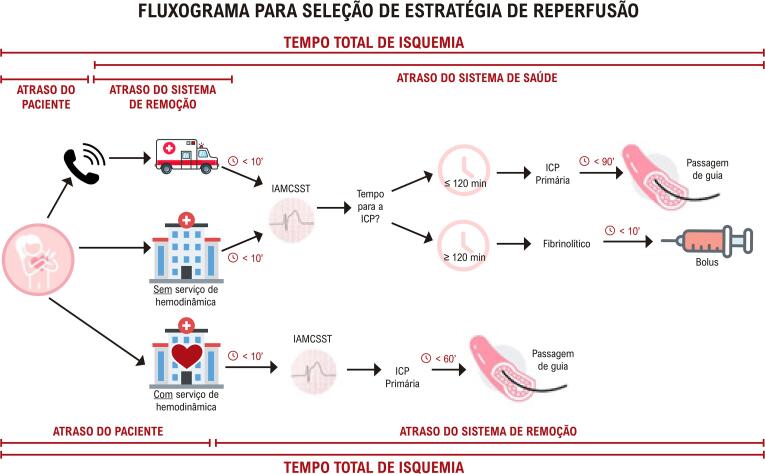

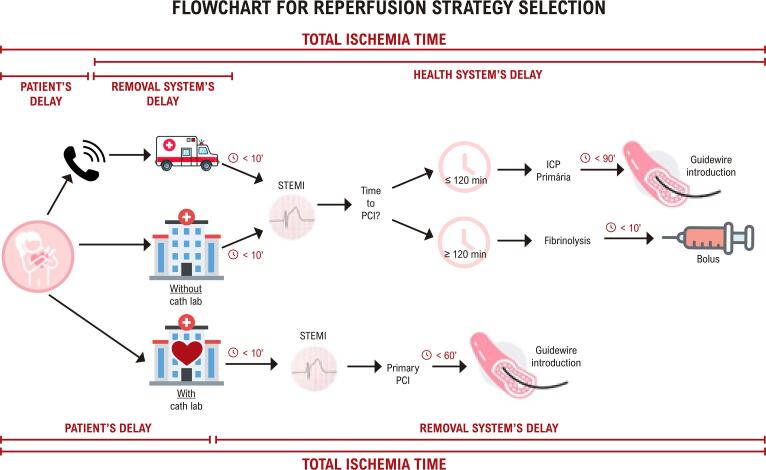

10.4.3. Revascularização para Infarto do Miocárdio Com Supradesnivelamento do Segmento ST 55

10.4.3.1. Estratégias na Abordagem da Doença Coronariana Múltipla

10.4.3.2. Choque Cardiogênico 55

10.4.4. Considerações sobre o Dispositivo durante a Revascularização Percutânea 55

10.4.4.1. Stents Farmacológicos 55

10.4.4.2. Balão Farmacológico 55

10.4.4.3. Aterectomia Rotacional e Litotripsia Intravascular 56

10.5. Terapia Farmacológica Adjunta 56

10.6. Gaps no Conhecimento 57

10.7. Recomendações 58

11. Intervenção Cirúrgica, Transplante Cardíaco 58

11.1. Revascularização do Miocárdio 58

11.1.1. Cirurgia de Revascularização do Miocárdio em Mulheres – Recomendações 60

11.2. Transplante Cardíaco 60

11.2.1. Transplante Cardíaco em Mulheres – Recomendações 62

12. Reabilitação na Cardiomiopatia Isquêmica das Mulheres 62

Referências 63

1. Introdução/Highlights

1.1. Introdução

As diferenças entre os sexos vão além das questões cromossômicas entre homens (XY) e mulheres (XX). Os valores sociais, as percepções e os comportamentos distintos moldam padrões e criam diferentes papéis na sociedade, o que pode gerar diferenças no estilo de vida e comportamento, possivelmente influenciando epidemiologia, manifestação clínica e tratamento.1

É importante destacar que, do ponto de vista clínico, a doença isquêmica do coração (DIC) ocorre mais precocemente no homem. Contudo, a incidência e a prevalência na mulher aumentam acentuadamente após a menopausa. Enfatiza-se ainda que a maior proporção de mulheres com sintomas anginosos e síndrome coronariana aguda (SCA) tem DIC não obstrutiva.

A DIC em mulheres inclui a aterosclerose coronariana clássica e compreende fisiopatologia variada, como disfunção microvascular coronariana, disfunção endotelial, anormalidades vasomotoras e dissecção espontânea de artéria coronária (DEAC).2

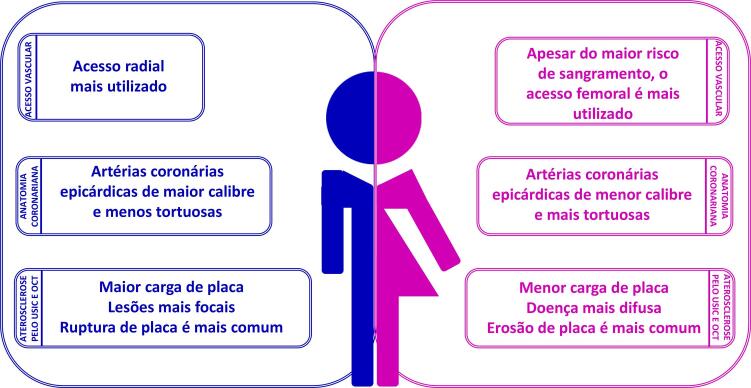

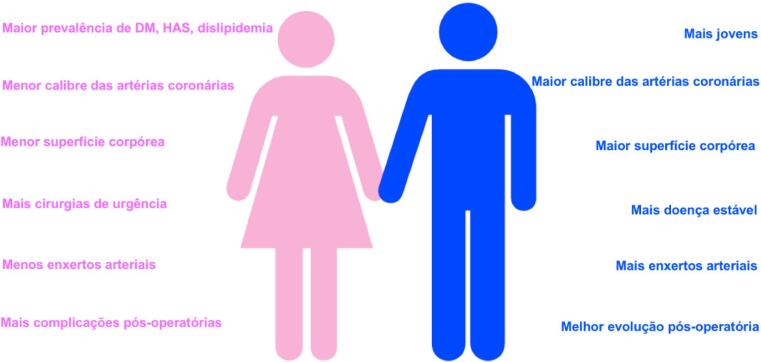

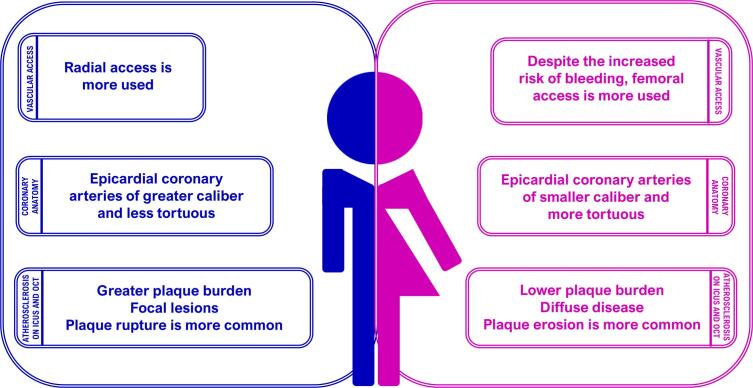

Em relação à anatomia, mulheres têm artérias coronárias epicárdicas menores do que homens, mesmo após ajuste para superfície corporal e massa do ventrículo esquerdo (VE). Porém, em comparação com os homens, as mulheres têm menor prevalência de aterosclerose coronariana obstrutiva e características de placa diversas, ainda que em níveis comparáveis de isquemia.3

As mulheres que apresentam DIC obstrutiva geralmente são mais velhas do que os homens, têm mais comorbidades cardiovasculares e maior incidência de desfechos cardiovasculares adversos, incluindo mortalidade após infarto agudo do miocárdio (IAM).4

As mulheres são menos propensas do que os homens a apresentar ruptura de placa e, nelas, a revascularização da artéria ocluída pode ser mais difícil devido a sangramento no local de acesso e artérias coronárias pequenas e mais tortuosas.5

A dor torácica é o sintoma mais prevalente de IAM em ambos os sexos. No entanto, as mulheres são mais propensas a apresentar sintomas atípicos, incluindo dor na parte superior das costas e pescoço, fadiga, náuseas e vômitos.6 A maioria das mulheres com IAM apresenta sintomas prodrômicos de falta de ar, fadiga incomum ou desconforto em braço/mandíbula nas semanas anteriores. Angina estável é a apresentação clínica mais frequente em mulheres com DIC em oposição a IAM ou morte súbita.7

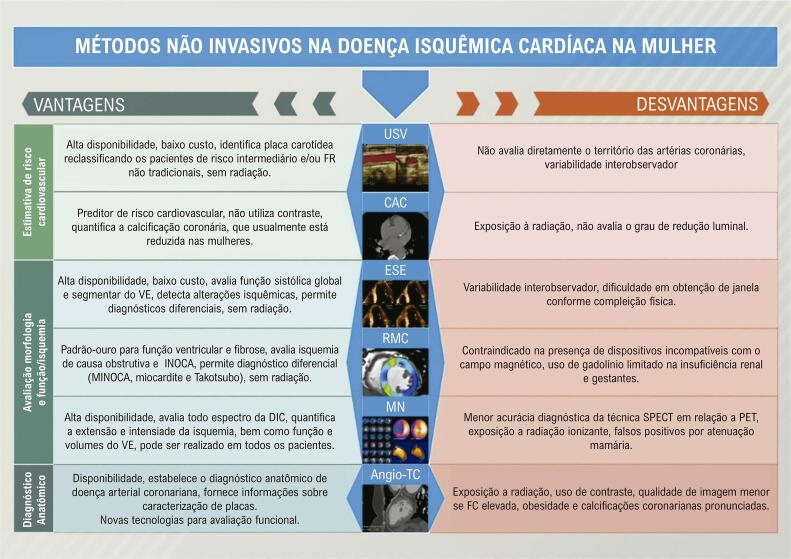

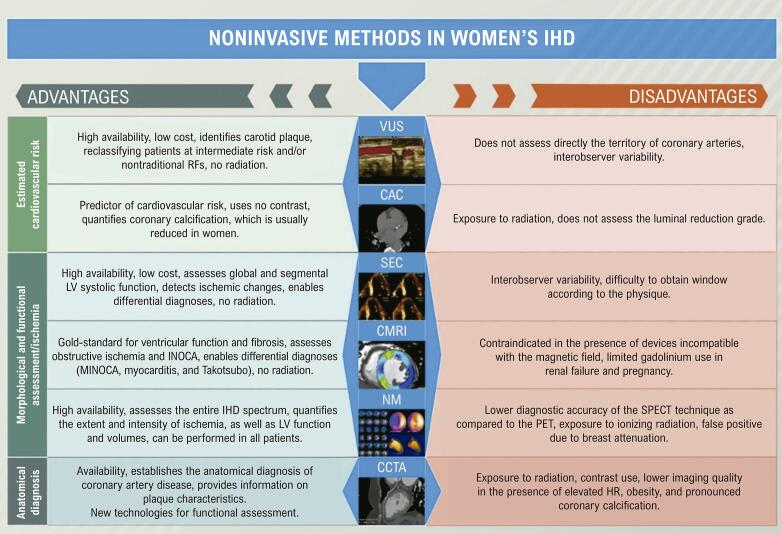

Revisão recentemente publicada resume alguns aspectos relacionados a vantagens e desvantagens, bem como valores de sensibilidade e especificidade de acordo com o gênero, dos principais métodos diagnósticos.8 A menor sensibilidade do teste ergométrico (TE) para detecção de doença coronariana obstrutiva em mulheres limita sua utilização no cenário da cardiomiopatia isquêmica (CMI).9 A ecocardiografia sob estresse (exercício ou dobutamina - ESE) tem performance melhor do que o TE, embora inferior à de outros métodos, com estudos mostrando desempenho similar ou inferior em mulheres.10,11 A incorporação de avaliação por doppler tecidual tem permitido análise quantitativa de viabilidade. A cintilografia miocárdica com imagens obtidas por tomografia computadorizada por emissão de fóton único (SPECT) tem boa performance em mulheres, principalmente quanto à sensibilidade.12 Algumas limitações em mulheres são relacionadas a falsos positivos decorrentes de atenuação mamária e menor acurácia em corações pequenos.13 Para avaliação de estresse miocárdio, a tomografia por emissão de pósitron (PET) é superior ao SPECT em qualidade de imagem e acurácia, tanto em mulheres quanto em homens.14 Dados adicionais caracterizam inflamação e vulnerabilidade das placas, eventos adversos e potencial benefício de revascularização.15

O TE e a ESE são considerados seguros na gestação, pois evitam exposição a radiação, enquanto dobutamina e dipiridamol são considerados categoria B. Técnicas de SPECT e PET-CT devem ser evitadas, mas a ressonância magnética cardíaca (RMC) é uma boa opção na gestação.16

Nas últimas décadas, têm sido documentadas diferenças na fisiologia e fisiopatologia cardiovascular entre mulheres e homens. Essas diferenças incluem as propriedades eletrofisiológicas da célula cardíaca, o que pode influenciar na ocorrência de arritmias clínicas distintas entre os sexos. Possivelmente, tais diferenças são de origem multifatorial. Entretanto, a ação hormonal e a influência autonômica são fatores importantes no comportamento eletrofisiológico distinto entre mulheres e homens.17

A média da frequência cardíaca (FC) em mulheres é aproximadamente 3 a 5 batimentos/minuto mais alta que a observada em homens.17 Além disso, foi documentado um menor tempo de recuperação do nó sinusal, menor intervalo HV, maior velocidade de condução ventricular e aumento no intervalo QT em mulheres.18

A prevalência de taquicardia sinusal inapropriada é muito maior em mulheres. Um estudo com 321 pacientes acompanhados por taquicardia sinusal inapropriada mostrou que 92% deles eram do sexo feminino.19 Aproximadamente 60% das taquicardias de QRS estreito observadas na prática clínica são secundárias a taquicardia por reentrada nodal, sendo sua prevalência duas vezes maior nas mulheres.20 O período refratário da via lenta é menor no sexo feminino, o que pode aumentar a janela de indutibilidade arrítmica e justificar o maior número de casos em mulheres.21 Entretanto, vale ressaltar que essa característica não interfere no sucesso do tratamento por ablação, que corresponde a 95% dos casos em ambos os sexos. Em contraste, a taquicardia por reentrada atrioventricular predomina no sexo masculino.18 Os homens apresentam mais frequentemente uma via acessória manifesta, com localização lateral esquerda. Por outro lado, nas mulheres, observa-se quase três vezes mais vias à direita.21

A incidência de fibrilação atrial (FA) ajustada para idade é uma vez e meia a duas vezes maior em homens. Entretanto, o risco de FA ao longo da vida é semelhante em ambos os sexos devido à maior expectativa de vida no sexo feminino. Nas mulheres, existe um aumento desproporcional de FA com o avançar da idade, de tal forma que, aos 85 anos, as diferenças na prevalência são discretas.17,22 Além disso, as mulheres são mais sintomáticas e apresentam pior qualidade de vida quando comparadas com os homens. Os mecanismos associados às diferenças entre os sexos na FA são inúmeros, mas é importante ressaltar que a DIC, mais observada no sexo masculino, pode corroborar com a maior incidência de FA nesse grupo. Em relação ao tratamento com drogas antiarrítmicas (DAA), as mulheres apresentam mais efeitos adversos. O aumento no intervalo QT basal pode afetar a tolerância ao uso de DAA, especialmente da classe III, exigindo uma monitorização mais cuidadosa nesse grupo de pacientes. Em relação aos resultados da ablação por cateter, estudos observacionais demonstram que as mulheres são submetidas menos frequente e mais tardiamente a ablação, em geral com evolução pior após o procedimento.23

As arritmias ventriculares em pacientes com coração normal apresentam características epidemiológicas variáveis entre os sexos. A taquicardia ventricular (TV) de via de saída do ventrículo direito é mais frequente em mulheres, ao passo que as arritmias com origem fascicular ocorrem mais em homens.24 Pacientes pré-púberes do sexo masculino com síndrome do QT longo tipo I e pré-púberes do sexo feminino com síndrome do QT longo tipo II apresentam maior risco de arritmia ventricular.25 A ocorrência de morte súbita cardíaca em mulheres é quase a metade da ocorrência em homens, mesmo após ajuste para fatores predisponentes.26

As mulheres com insuficiência cardíaca (IC) geralmente são mais idosas que os homens e têm maior prevalência de IC com fração de ejeção preservada (ICFEp). Além disso, mostram mais cardiopatia não isquêmica, diabetes mellitus (DM) e hipertensão arterial sistêmica (HAS). Vários fatores levam a menor inclusão de mulheres nos estudos sobre DIC. Os relacionados à condição da paciente são (1) necessidade de viajar e se ausentar do trabalho, (2) ausentar-se das responsabilidades com os filhos, a família e o lar, (3) necessidade de elevado nível de compromisso, (4) barreiras socioeconômicas, psicológicas, culturais e de saúde. Os fatores relacionados ao estudo são: (1) baixas taxas de encaminhamento e triagem de elegibilidade, (2) falta de critério de elegibilidade relacionado ao sexo, (3) liderança heterogênea dos estudos, principalmente composta por homens, (4) exclusão de idosos. Ações futuras são importantes para uma maior inclusão de mulheres portadoras de DIC nos grandes estudos.27Este posicionamento, através de ação conjunta das especialidades da cardiologia com expertise na mulher, tem como principal objetivo divulgar informações sobre a DIC sob vários aspectos para um melhor entendimento de suas particularidades, visando melhor tratar essas pacientes e consequentemente reduzir sua morbimortalidade.

1.2. Destaques deste Posicionamento

1.2.1. Epidemiologia

• A DIC mantém-se como a principal causa de morte de mulheres e homens no Brasil. Houve diminuição mais pronunciada do percentual da taxa de mortalidade por DIC padronizada nas mulheres entre os anos de 1990 e 2019, -55,5 (II95%, -58,7; -52,3), do que nos homens, -49,5 (II95%, -52,5; -46,6), nesse mesmo período. Esse declínio foi desigual nas unidades da federação em ambos os sexos, estando relacionado com o envelhecimento da população e com o índice sociodemográfico (SDI) de 2019.

• A incidência e a prevalência da DIC vêm diminuindo no Brasil ao longo dos últimos 20 anos em mulheres e homens, embora tenha ocorrido aumento na mortalidade precoce por DIC entre 18 anos e 55 anos, especialmente nas mulheres. Nas mulheres, houve uma diferença entre as regiões brasileiras na incidência de DIC padronizada por idade, que foi maior nas regiões Sudeste e Sul e menor na região Norte.

• As mulheres apresentaram taxas significativamente menores de angioplastia primária e significativamente maiores de mortalidade hospitalar. A prevalência de MINOCA (infarto do miocárdio na ausência de obstrução arterial coronária) é maior nas mulheres, com mortalidade semelhante à da DIC obstrutiva, associando-se com risco de eventos maiores.

• O estudo do Global Burden of Diseases (GBD) 2019 estimou taxa padronizada de DALYs (anos de vida ajustados por incapacidade) por DIC por 100 mil habitantes de 1.088,4 (992,8; 1.158,9) nas mulheres e de 2.116,5 (II95%, 1.989,9; 2.232,2) nos homens. A DIC foi a segunda causa mais comum de DALYs no Brasil nas mulheres (após distúrbios neonatais) e nos homens (após violência interpessoal) em 2019. Essas taxas foram heterogêneas nas regiões geográficas brasileiras e a tendência das taxas de DALYs padronizadas por idade de 1990 a 2019, nas mulheres, assemelhou-se à das taxas de mortalidade.

• As mulheres apresentam maior frequência de fatores de risco cardiovascular (FRCV) não tradicionais, como estresse mental e depressão, e sofrem maior consequência das desvantagens sociais devido a raça, etnicidade e renda. As mulheres têm ainda os fatores de risco (FR) inerentes ao sexo, como gravidez, menopausa e menarca, entre outros.

1.2.2. Bases Fisiopatológicas da Doença Aterotrombótica

A doença coronariana obstrutiva, caracterizada pela presença de placas de aterosclerose nas paredes das artérias coronárias, é o substrato mais frequente de DIC nas mulheres. Entretanto, é reconhecido que a doença coronariana não obstrutiva com evidências de danos ao músculo cardíaco ou outros sinais de enfermidade coronariana afeta desproporcionalmente mais mulheres.

• Os mecanismos fisiopatológicos envolvidos na MINOCA incluem ruptura de placa coronariana, DEAC, vasoespasmo coronariano, disfunção microvascular coronariana e embolismo/trombose. Importante destacar as síndromes que mimetizam clinicamente MINOCA, como Takotsubo, miocardite e cardiomiopatia não isquêmica.

1.2.3. Apresentação Clínica, Diagnóstico e Tratamento Clínico

• As diferenças biológicas e socioculturais específicas do sexo feminino na apresentação da dor torácica da DIC podem explicar as diferenças em sua apresentação clínica, seu diagnóstico e seu manejo, levando a atrasos na conduta e, consequentemente, desfechos desfavoráveis.

• Os sintomas isquêmicos das mulheres são mais relacionados ao estresse emocional ou mental e menos frequentemente precipitados pela atividade física, em comparação aos homens. Escore de risco global e caracterização de angina não devem ser usados uniformemente em mulheres e homens, devido ao impacto diferente dos FR e às manifestações clínicas variáveis entre os sexos.

• Existem diferentes proporções na relevância dos FR entre os sexos, como HAS, obesidade, DM e tabagismo. Os FR específicos do sexo feminino são relevantes na estratificação de risco: pré-eclâmpsia e diabetes gestacional aumentam o risco cardiovascular (RCV) da mulher por toda a vida.

• Mulheres são menos submetidas a coronariografia e tratamento cirúrgico, incluindo suporte circulatório mecânico no choque cardiogênico. No entanto, têm maior mortalidade e complicações pós-operatórias, apesar de menor carga aterosclerótica.

• Menos de 50% das pacientes são submetidas a tratamento medicamentoso adequado, além de ser baixa a aderência ao tratamento e existir subutilização de reabilitação cardíaca.

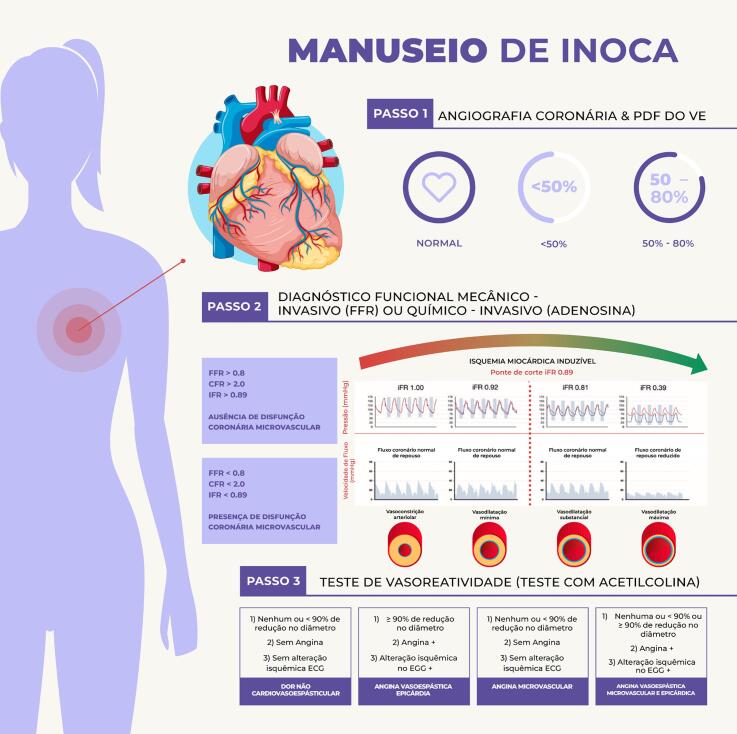

• O tratamento da MINOCA e da isquemia do miocárdio sem doença coronariana obstrutiva (INOCA) baseia-se na mudança de estilo de vida, controle dos FR e tratamento antianginoso.

1.2.4. Diagnóstico por Avaliação Funcional Gráfica

• A posição inadequada dos eletrodos no eletrocardiograma (ECG) pode causar diagnóstico equivocado nas mulheres. Mamas volumosas ou próteses mamárias podem gerar complexos de baixa voltagem e reduzem a amplitude da onda R nas derivações V1 e V2, simulando área inativa. O ECG na avaliação de dor torácica utiliza os mesmos critérios diagnósticos descritos para o sexo masculino, exceto para análise de lesão subepicárdica.

• O TE é recomendado como método inicial de escolha na avaliação de mulheres sintomáticas de risco intermediário para DIC, com ECG de repouso normal e capazes de se exercitar. Além das alterações do segmento ST, a capacidade de exercício, as respostas cronotrópica e da pressão arterial (PA), a recuperação da FC e a avaliação do escore de Duke (ED) são informações prognósticas que aumentam a acurácia do TE, especialmente nas mulheres. A capacidade funcional é a variável prognóstica mais importante para morbimortalidade por todas as causas em mulheres, incluindo as assintomáticas. A incapacidade de atingir 5 MET é preditora independente de alto risco, com aumento de três vezes na mortalidade em comparação àquelas que atingem mais de 8 MET.

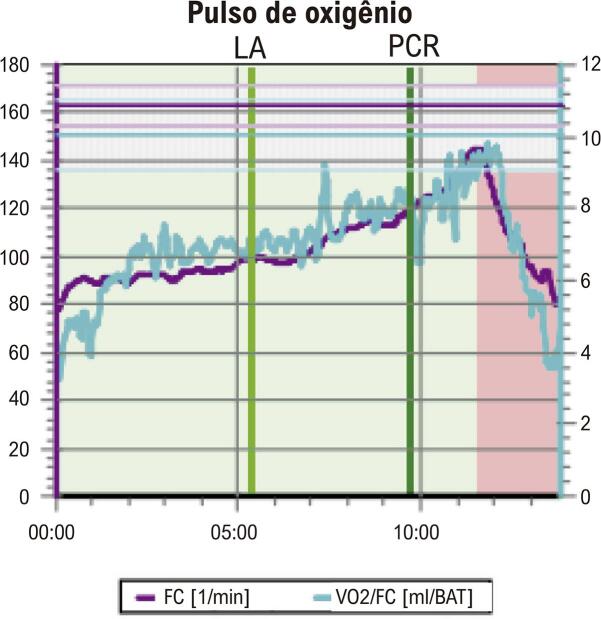

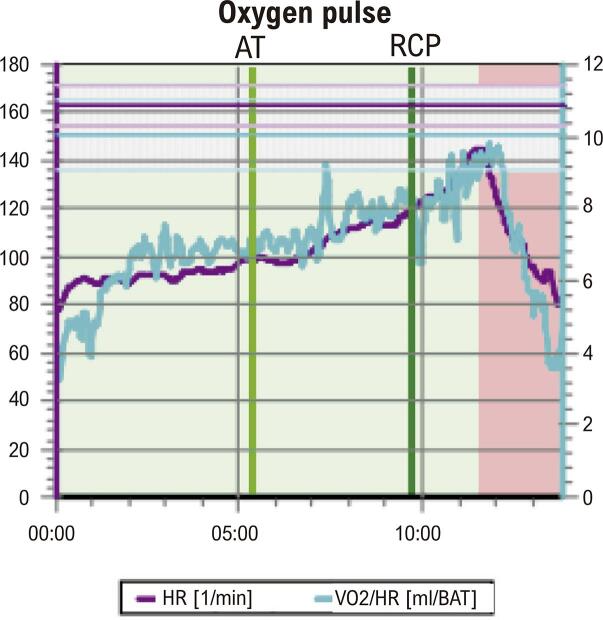

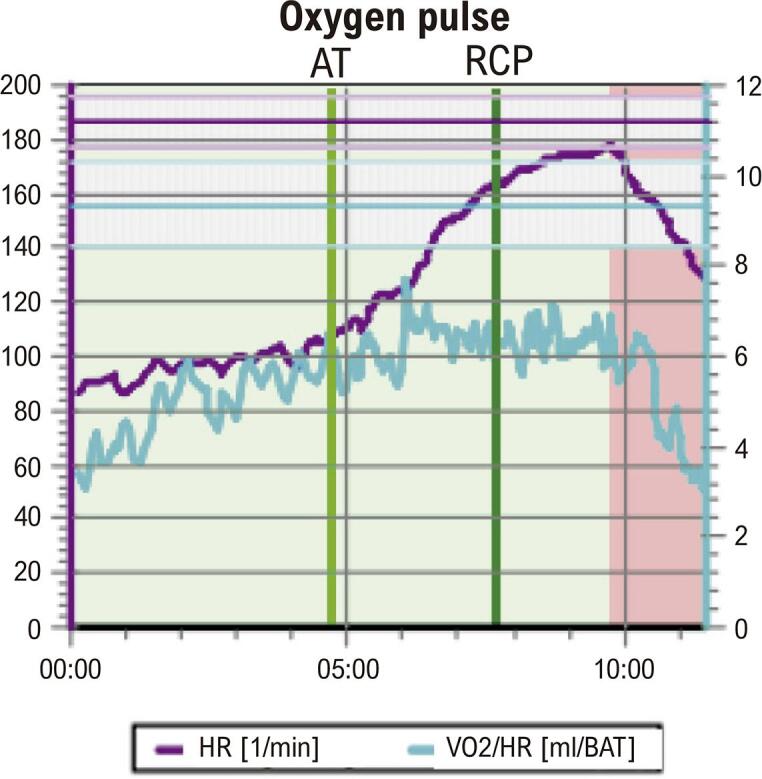

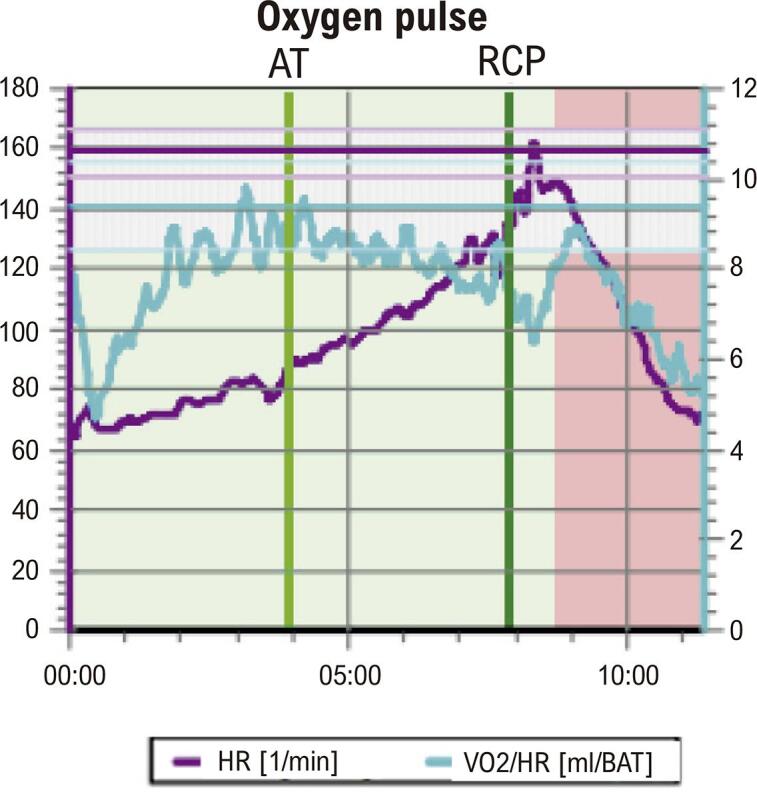

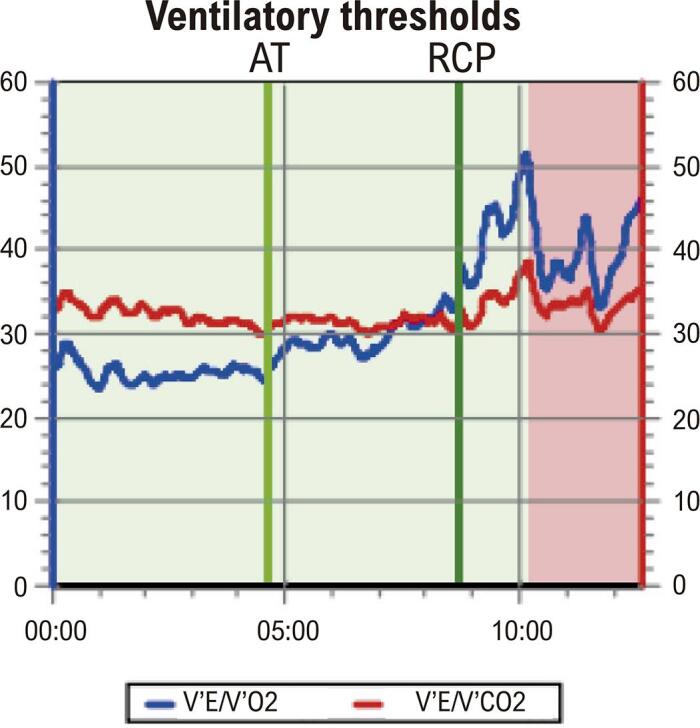

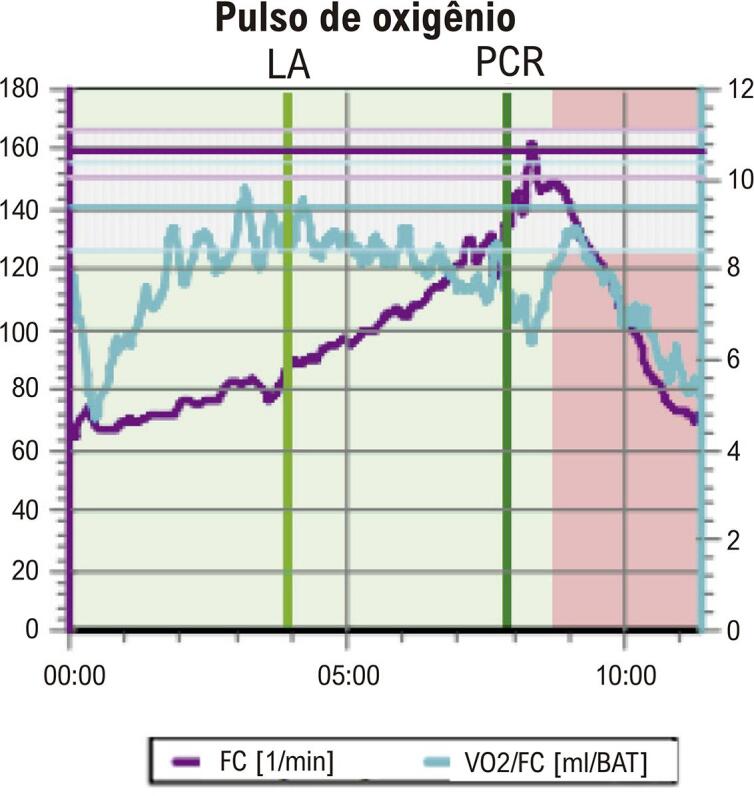

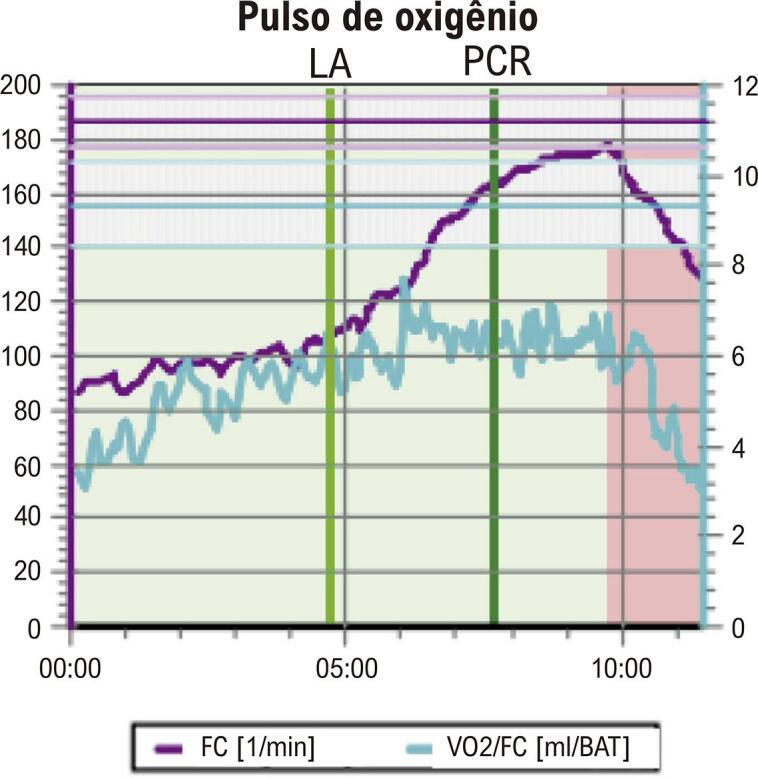

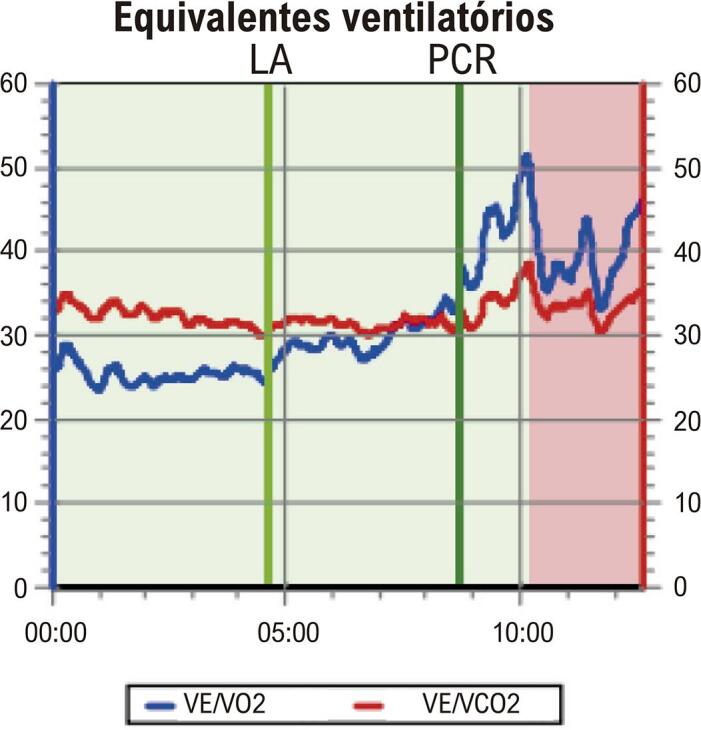

• O teste cardiopulmonar de exercício (TCPE) permite realizar diagnóstico, prognóstico, acompanhamento após intervenção terapêutica e prescrição de exercícios aeróbicos na DIC. O TCPE apresenta maior acurácia diagnóstica na DIC de mulheres do que o TE. Além dos critérios clínicos, hemodinâmicos e eletrocardiográficos, o TCPE fornece a análise do pulso de oxigênio (PO2), que permite inferir a disfunção ventricular isquêmica induzida pelo esforço, cujo achado pode ser relevante no diagnóstico da DIC macro e microvascular na mulher.

1.2.5. Diagnóstico por Imagem Cardiovascular Não Invasiva

• A ESE apresenta boa acurácia na investigação de DIC nas mulheres, avalia a função sistólica do VE, permite o diagnóstico diferencial, além de oferecer segurança pela ausência de radiação.

• A ultrassonografia vascular (USV) é útil na detecção de placas carotídeas como modificador de risco em mulheres de probabilidade intermediária e/ou FR não tradicionais, no rastreamento de aneurisma de aorta abdominal em mulheres tabagistas ou ex-tabagistas entre 55 anos e 75 anos e na busca de doença arterial periférica (DAP) silenciosa.

• Angiotomografia coronariana (Angio-TC) apresenta boa acurácia diagnóstica e prognóstica na avaliação de DIC em mulheres, caracterizando e quantificando as lesões. Classicamente, mulheres apresentam lesões menos calcificadas e não obstrutivas em relação a homens.

• A RMC oferece maiores informações na detecção da DIC na mulher: identifica isquemia por DIC obstrutiva e não obstrutiva, MINOCA, avalia viabilidade miocárdica, distingue a doença isquêmica da inflamatória e define diagnóstico de Takotsubo.

• A imagem nuclear avalia todo o espectro da DIC, desde doença coronariana obstrutiva até disfunção microvascular coronariana, sem limitações quanto a função renal, arritmias, obesidade e dispositivos intracardíacos.

1.2.6. Arritmias na Cardiopatia Isquêmica

• As mulheres têm mais taquicardia sinusal inapropriada e taquicardia por reentrada nodal e menos FA, arritmias ventriculares malignas, como TV e fibrilação ventricular (FV), e morte súbita cardíaca do que os homens. A despeito da diferença na prevalência entre os sexos, as mulheres se beneficiam do tratamento das arritmias cardíacas.

• As mulheres com FA têm maior prevalência de HAS, obesidade, depressão, ICFEp e doença valvar como causa da arritmia. São também preditores de risco de FA nas mulheres a falta ou escassez de exercício, a monoterapia com estrogênio e a multiparidade. As mulheres com FA têm alto risco de acidente vascular cerebral (AVC), não havendo diferença significativa no risco de AVC ou de embolia sistêmica e sangramento gastrointestinal entre mulheres e homens em uso de anticoagulantes. Foi demonstrada redução significativa de hemorragia intracraniana e mortalidade por todas as causas nas mulheres com FA em uso de anticoagulantes de ação direta (DOACs). As mulheres com FA têm pior qualidade de vida do que os homens e são menos submetidas a procedimentos, como a ablação por cateter ou cardioversão elétrica (CVE).

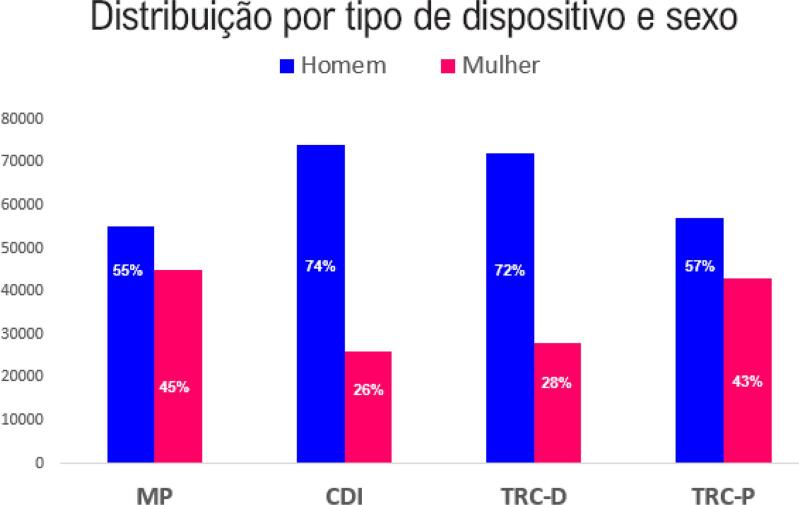

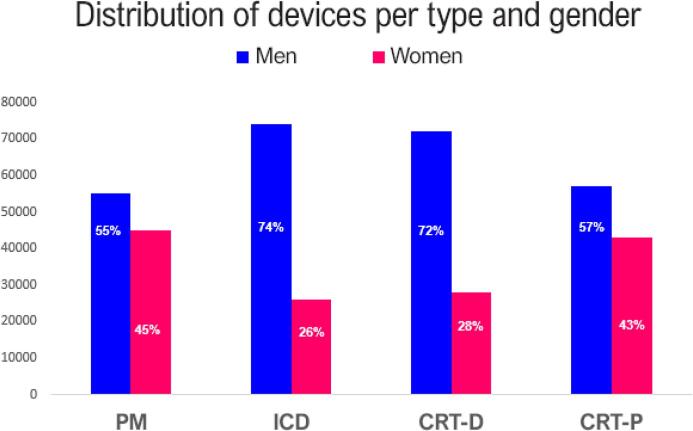

• As mulheres têm menos CMI que os homens e aquelas com DIC e portadoras de cardiodesfibrilador implantável (CDI) apresentam menos episódios de TV/FV e de tempestade elétrica e ainda menos choques pelo CDI do que os homens. As mulheres têm menos CMI e menor carga de fibrose do que os homens submetidos à terapia de ressincronização cardíaca (TRC) e respondem melhor à TRC do que os homens, com maiores intervalos de tempo até a primeira hospitalização e menor mortalidade. As terapias como CDI e TRC trazem benefícios na mortalidade. As mulheres representam em torno de 30% das populações dos estudos com essas terapias.

• O percentual de mulheres contempladas nos estudos de ablação de TV na população com DIC é baixo (7-13%). A menor indicação de procedimentos invasivos, a menor indução de TV sustentada e o menor número de choques apropriados são fatores que podem contribuir para esse percentual reduzido.

1.2.7. Aterotrombose na Gravidez, Contracepção, Infertilidade, Síndrome Antifosfolípide

• A doença aterotrombótica é uma das causas mais frequentes de IAM durante a gravidez e o puerpério.

• A conduta diante da DIC aguda durante a gravidez deve priorizar a vida materna e seguir as recomendações para a população em geral.

• A tríade conjugada (tabagismo, idade acima de 35 anos e uso prolongado, > 10 anos, de anticoncepcional combinado oral) é considerada o fator determinante da manifestação clínica da doença aterotrombótica durante a gravidez e o puerpério.

• A queixa de dor torácica durante a gravidez em mulheres que apresentam FR para a doença cardiovascular (DCV) não deve ser subestimada e deve seguir protocolo convencional de investigação para SCA.

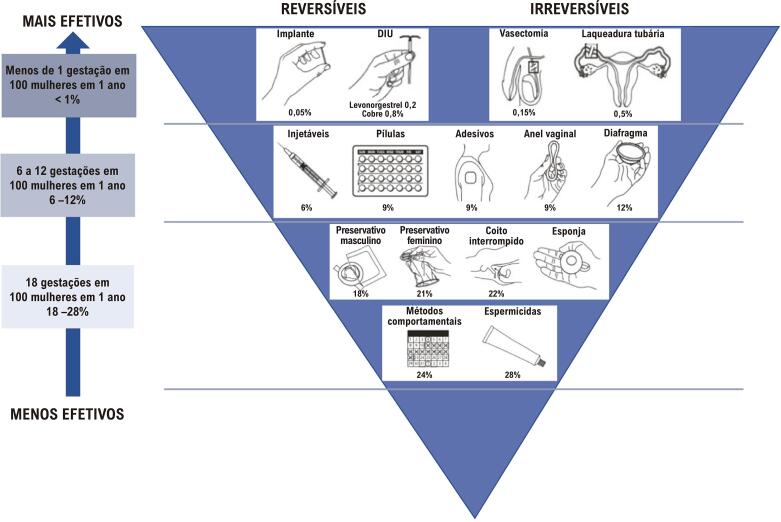

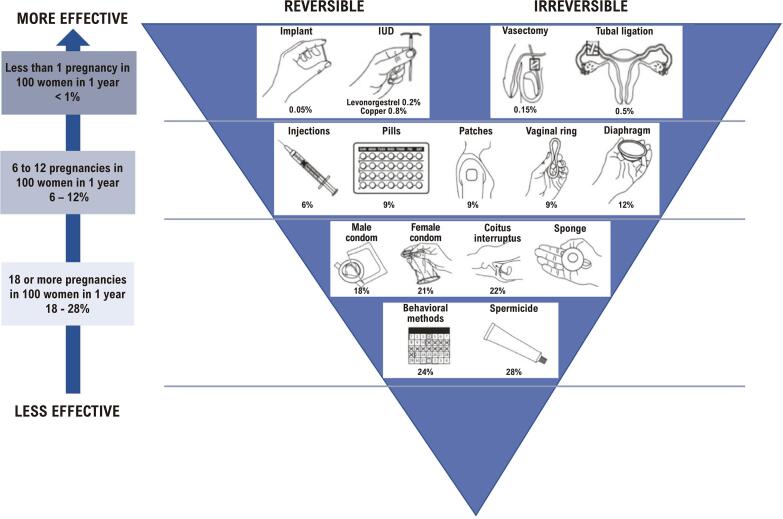

• Os contraceptivos não estão isentos de efeitos aterotrombóticos, mas a não prescrição incorre no risco de gravidez não planejada, principalmente na adolescência e em mulheres com comorbidades. A seleção do método de contracepção deve ser individualizada, atender à preferência e idade da paciente, assim como à segurança e eficácia do método.

• A frequência de distúrbios metabólicos pró-ateroscleróticos, particularmente obesidade e aumento de colesterol total, LDL-colesterol e triglicerídeos, é maior entre as mulheres que sofrem de infertilidade.

• A terapêutica da infertilidade é considerada um potencial FR para os distúrbios hipertensivos na gestação subsequente. Contudo, ainda não foi demonstrada correlação entre tratamento para fertilização e eventos cardiovasculares.

• Diagnóstico de síndrome antifosfolípide (SAF) deve ser presumido diante da manifestação clínica de trombose vascular e/ou complicações obstétricas recorrentes, sendo sua investigação obrigatória na presença de AVC e IAM em mulheres jovens.

1.2.8. Cardiomiopatia Isquêmica

• A IC relacionada à CMI é uma importante causa de morbidade e mortalidade em mulheres, que tendem a desenvolvê-la em idade mais avançada que os homens.

• A ICFEp é mais comum em mulheres, mas a etiologia isquêmica tende a manifestar-se na forma dilatada e de fração de ejeção reduzida, ainda que com menos fibrose endomiocárdica quando comparada com homens.

• As mulheres estão pouco representadas em ensaios clínicos para IC. Apesar disso, as recomendações para terapias medicamentosas e avançadas nas diretrizes não sugerem tratamento individualizado para as mulheres.

1.2.9. Intervenção Coronariana Percutânea

• No procedimento intervencionista, estratégias para redução no risco de sangramento e de complicações vasculares devem ser adotadas, priorizando a via de acesso radial e a utilização de fármacos adjuntos em doses adequadas ao peso e à função renal.

• Avaliação funcional na doença coronariana, através da análise da reserva de fluxo fracionada (FFR), é de grande valia naquelas obstruções intermediárias (40% a 70%), quando não se tem isquemia comprovada por métodos não invasivos. As mulheres parecem ter valores de FFR mais altos para doença coronariana não obstrutiva, ratificando ser ainda mais relevante medir a FFR em mulheres, além de ser também um preditor univariado significativo de prognóstico para esse grupo.

• Devem-se identificar perfis de alto risco para sangramento e perseguir a excelência nos resultados da intervenção através de seleção criteriosa e preparo adequado das lesões, baixo limiar para utilização de guia de imagem intravascular, implante otimizado dos stents e estratégia antiplaquetária pós-intervenção personalizada.

• Devem-se utilizar estratégias no laboratório de hemodinâmica para otimizar o diagnóstico etiológico nos casos de MINOCA.

• Deve-se considerar o diagnóstico de disfunção microvascular coronariana, mais frequente em mulheres, tanto em cenários crônicos como agudos, que pode ser corroborado por métodos fisiológicos invasivos coronarianos.

1.2.10. Revascularização Miocárdica e Transplante Cardíaco

• O uso de enxertos arteriais na revascularização miocárdica (RVM) é menor em mulheres.

• Na evolução pós-operatória, as mulheres apresentam maior taxa de complicações.

• A indicação cirúrgica retardada tem impacto negativo nos resultados pós-operatórios.

• Atualmente 25% dos transplantados cardíacos são realizados em mulheres, que apresentam maior taxa de complicações, principalmente rejeição, e têm melhor sobrevida do que os homens após o transplante cardíaco.

• Mulheres evoluem com incidência menor de tumores malignos no pós-operatório.

1.2.11. Reabilitação na Cardiomiopatia Isquêmica

• O encaminhamento à reabilitação cardíaca deve fazer parte da prescrição médica para mulheres com DIC, inclusive nos casos de DEAC e MINOCA.

• A avaliação inicial e a prescrição do programa de reabilitação cardíaca devem ser direcionadas pelas especificidades da mulher para que haja maior engajamento e menor desistência.

2. Epidemiologia da Doença Isquêmica do Coração nas Mulheres

2.1. Introdução

O crescimento da população e o aumento da expectativa de vida geraram incremento do número total de mortes por DIC no mundo. As taxas de mortalidade por DIC padronizadas por idade em mulheres e homens diminuíram de forma gradual na maioria dos países, provavelmente devido a melhorias no diagnóstico e tratamento, ainda que tenha ocorrido um aumento relevante da obesidade, da elevação da glicose sérica de jejum e da síndrome metabólica.28-31

A DIC mantém-se como a principal causa de morte em mulheres e homens no Brasil. A incidência e a prevalência da DIC vêm diminuindo no Brasil ao longo dos últimos 20 anos em mulheres e homens, embora tenha ocorrido aumento na mortalidade precoce por essa causa, entre 18 anos e 55 anos, especialmente nas mulheres. A DIC também foi a segunda maior causa de DALYs nas mulheres no Brasil no período de 1990 a 2019.31

As mulheres apresentam maior impacto dos FRCV tradicionais e têm pior prognóstico, apesar de a carga de risco por DIC e a carga aterotrombótica serem menores. As mulheres apresentam maior frequência de FRCV não tradicionais, como estresse mental e depressão, e sofrem maior consequência das desvantagens sociais devidas a raça, etnicidade e renda.32

A MINOCA predomina nas mulheres.29 Os desfechos são substancialmente piores em comparação aos homens, além disso as mulheres mais jovens (< 55 anos) e os subgrupos de mulheres definidos por raça, etnia, status socioeconômico e escolaridade apresentam disparidades ainda mais marcantes quanto a diagnóstico, tratamento e prognóstico da DIC.29,32

Este capítulo tem como objetivo sumarizar os achados sobre a epidemiologia da DIC nas mulheres, especialmente as brasileiras.

2.2. Mortalidade

Dados recentes do projeto GBD de 2021 estimaram para a DCV no Brasil taxas padronizadas de 3.568,0 DALYs (um DALY representa a perda do equivalente a um ano de plena saúde) e 162,2 mortes por 100 mil habitantes, com uma taxa de prevalência padronizada de 6.905,6 por 100 mil habitantes. Ainda segundo o GBD 2021, as taxas estimadas para a DIC na América Latina Tropical (Brasil e Paraguai) em 2021 foram as seguintes: prevalência de 1.989,5, mortalidade de 67,7 e 1.439,6 DALYs por 100 mil habitantes. Embora um progresso considerável tenha sido feito na diminuição do número de mortes por DCV desde 1980 até o final de 2021, houve um aumento preocupante da taxa de mortalidade bruta e do número de DALYs nos últimos anos por DCV.28

A DCV é a principal causa de morte em mulheres no mundo e foi responsável por aproximadamente um terço do total de mortes em mulheres em 2021. A mortalidade por DCV diminuiu globalmente nos últimos 30 anos, com declínio mais significativo em países com alto SDI (SDI = média composta pela renda per capita, nível educacional médio e taxa de fertilidade). No entanto, em regiões de alta renda, a tendência de redução da mortalidade por DCV diminuiu e, em 2017, aumentou o número de mortes em mulheres de alguns países, como Estados Unidos e Canadá.29

Na região das Américas, a taxa de mortalidade por DIC ajustada por idade diminuiu no período de 2000 a 2019 nos homens, passando de 149,08 (II95%, 138,23; 168,08) para 96,02 (II95%, 83,48; 117,19), com decréscimo percentual de -2,3 (II95%, -2,5; -2,1), e nas mulheres, passando de 92,36 (II95%, 81,35; 109,42) para 54,84 (II95%, 45,28; 71,76), com decréscimo percentual de -2,7 (II95%, -3,0; -2,5). Nesse mesmo período, as taxas de mortalidade diminuíram significativamente em 24 países. Costa Rica, Canadá e Chile tiveram os maiores decréscimos percentuais, enquanto aumento significativo ocorreu na República Dominicana e em Granada.30

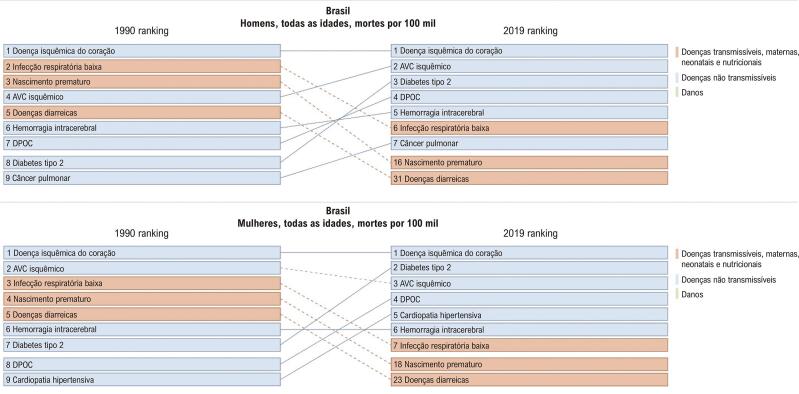

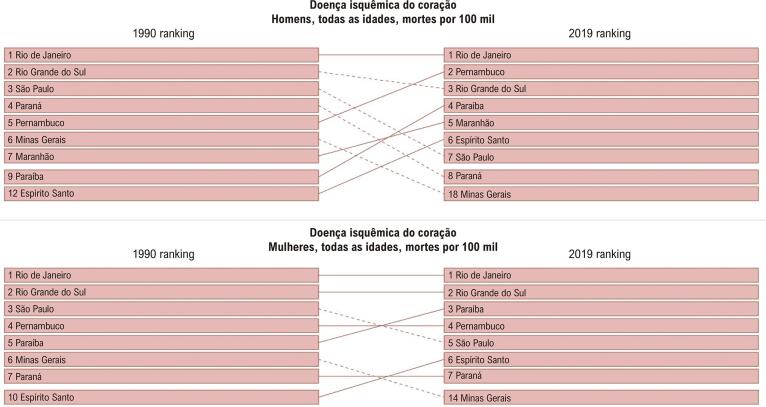

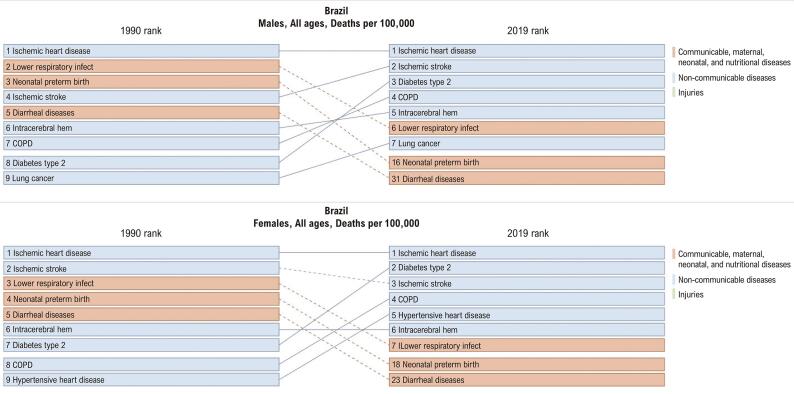

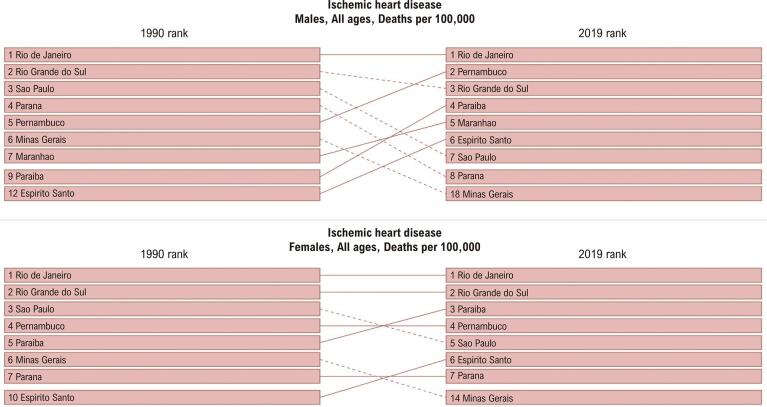

No Brasil, de 1990 a 2019, observou-se um declínio na taxa de mortalidade por DCV padronizada nas mulheres. Segundo o estudo GBD 2019, a DIC (definida como indivíduos com infarto do miocárdio prévio, angina estável ou IC isquêmica) foi a principal responsável pela morte de mulheres, seguida por DM tipo 2 e AVC, nessa ordem (Figura 2.1). Esse declínio foi desigual nas unidades da federação em ambos os sexos (Figura 2.2 e Figura 2.3A), sendo relacionado com o envelhecimento da população e o SDI de 2019.

Figura 2.1. – Ranking das taxas de mortalidade (por 100 mil habitantes) de acordo com sexo, no Brasil, em 1990 e 2019.

Fonte: Estudo Global Burden of Diseases (GBD) 2019.31

Figura 2.2. – Ranking das taxas de mortalidade por doença isquêmica do coração (por 100 mil habitantes) de acordo com as unidades da federação e por sexo, no Brasil, em 1990 e 2019.

Fonte: Estudo Global Burden of Diseases (GBD) 2019.31

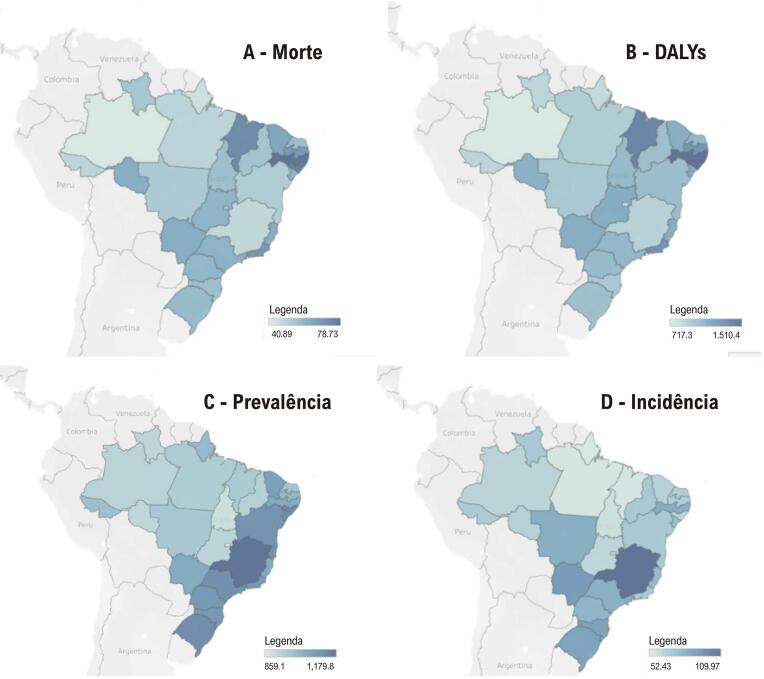

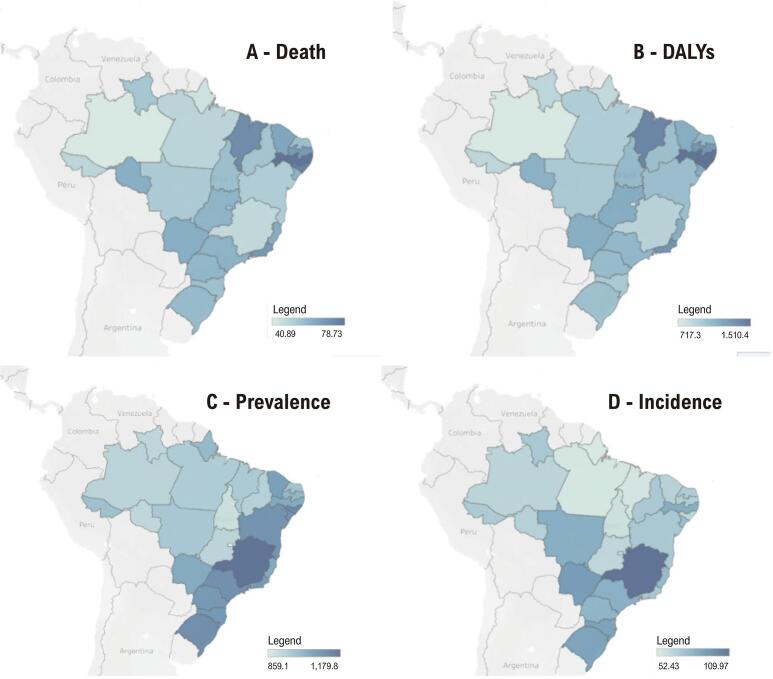

Figura 2.3. – Doença isquêmica do coração: taxas padronizadas de mortalidade (A), DALYs (B), prevalência (C) e incidência (D), por 100 mil habitantes, de acordo com as unidades da federação brasileira, nas mulheres, em 2019.

Fonte: Estudo Global Burden of Diseases (GBD) 2019.31

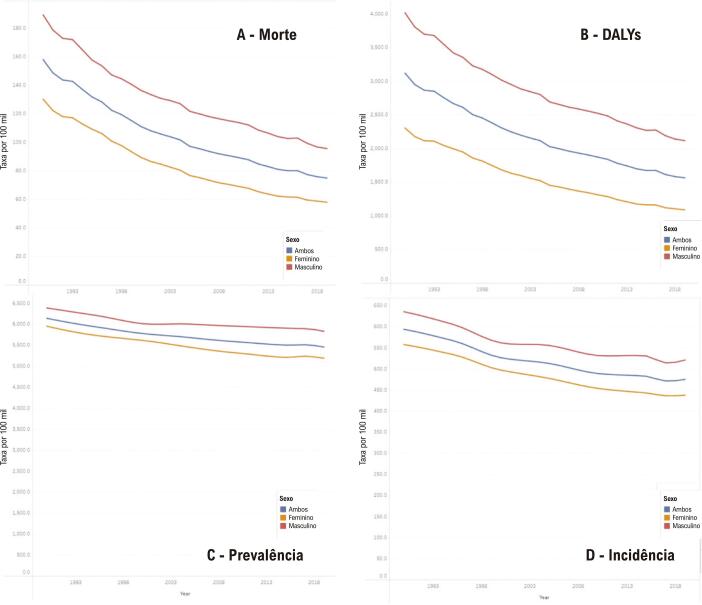

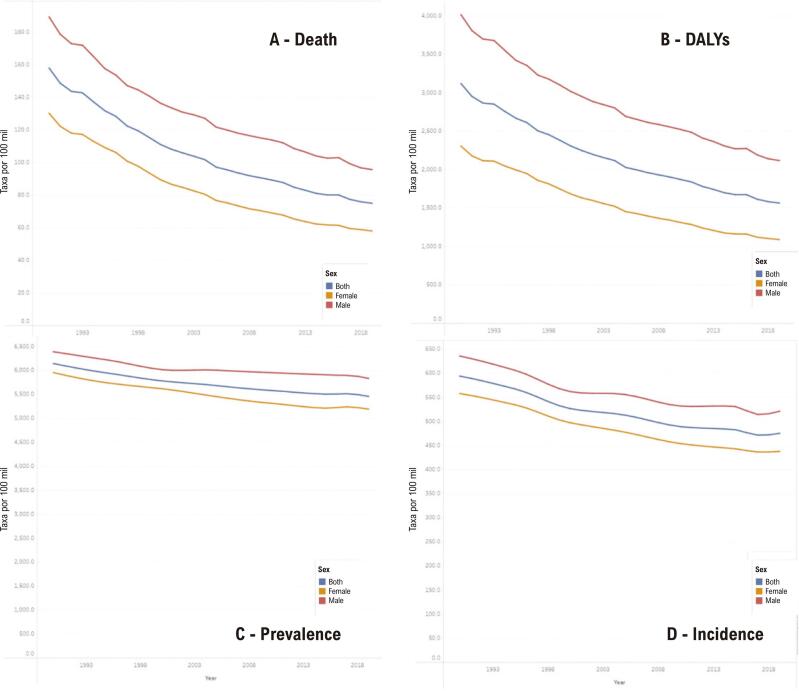

Dados do GBD 2019 estimaram que, em 2019, as taxas de mortalidade padronizadas por idade por DIC foram 58 (II95%, 51; 63) e 96 (II95%, 88; 101) por 100 mil habitantes no Brasil nas mulheres e nos homens, respectivamente. Entre os anos de 1990 e 2019, houve diminuição mais pronunciada do percentual da taxa de mortalidade por DIC padronizada nas mulheres, -55,5 (II95%, -58,7; -52,3), do que nos homens, -49,5 (II95%, -52,5; -46,6) (Figura 2.4A). Em todos os grupos etários, as taxas de mortalidade por DIC foram maiores nos homens do que nas mulheres e aumentaram com o envelhecimento em ambos os sexos (Tabela 2.1).31

Figura 2.4. – Doença isquêmica do coração: taxas padronizadas de mortalidade (A), DALYs (B), prevalência (C) e incidência (D), por 100 mil habitantes, de acordo com o sexo, no Brasil, em 2019.

Fonte: Estudo Global Burden of Diseases (GBD) 2019.31

Tabela 2.1. – Números de mortes, taxas de mortalidade, DALYs, prevalência e incidência, por 100 mil habitantes, e variações percentuais das taxas, devido a doença isquêmica do coração, por faixas etárias e sexo, Brasil, 1990 e 2019.

| DOENÇAS ISQUÊMICAS DO CORAÇÃO | 1990 | 2019 | Variação Percentual da Taxa (II 95%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Número (II 95%) | Taxa (II 95%) | Número (II 95%) | Taxa (II 95%) | ||

| MORTE | |||||

| Mulheres | |||||

| 15-49 anos |

|

|

|

|

|

| 50-69 anos |

|

|

|

|

|

| 70+ anos |

|

|

|

|

|

| Padronizada por idade |

|

|

|

|

|

| Todas as idades |

|

|

|

|

|

| Homens | |||||

| 15-49 anos |

|

|

|

|

|

| 50-69 anos |

|

|

|

|

|

| 70+ anos |

|

|

|

|

|

| Padronizada por idade |

|

|

|

|

|

| Todas as idades |

|

|

|

|

|

| INCIDÊNCIA | |||||

| Mulheres | |||||

| 15-49 anos |

|

|

|

|

|

| 50-69 anos |

|

|

|

|

|

| 70+ anos |

|

|

|

|

|

| Padronizada por idade |

|

|

|

|

|

| Todas as idades |

|

|

|

|

|

| Homens | |||||

| 15-49 anos |

|

|

|

|

|

| 50-69 anos |

|

|

|

|

|

| 70+ anos |

|

|

|

|

|

| Padronizada por idade |

|

|

|

|

|

| Todas as idades |

|

|

|

|

|

| PREVALÊNCIA | |||||

| Mulheres | |||||

| 15-49 anos |

|

|

|

|

|

| 50-69 anos |

|

|

|

|

|

| 70+ anos |

|

|

|

|

|

| Padronizada por idade |

|

|

|

|

|

| Todas as idades |

|

|

|

|

|

| Homens | |||||

| 15-49 anos |

|

|

|

|

|

| 50-69 anos |

|

|

|

|

|

| 70+ anos |

|

|

|

|

|

| Padronizada por idade |

|

|

|

|

|

| Todas as idades |

|

|

|

|

|

| DALY | |||||

| Mulheres | |||||

| 15-49 anos |

|

|

|

|

|

| 50-69 anos |

|

|

|

|

|

| 70+ anos |

|

|

|

|

|

| Padronizada por idade |

|

|

|

|

|

| Todas as idades |

|

|

|

|

|

| Homens | |||||

| 15-49 anos |

|

|

|

|

|

| 50-69 anos |

|

|

|

|

|

| 70+ anos |

|

|

|

|

|

| Padronizada por idade |

|

|

|

|

|

| Todas as idades |

|

|

|

|

|

Estudo com dados do Brasil oriundos do Sistema de Informação sobre Mortalidade (SIM) reportou que o coeficiente de morte relacionada à DIC permaneceu estável para mulheres nas regiões Norte e Centro-Oeste entre 1981 e 2001, enquanto diminuiu no Sul e Sudeste e aumentou no Nordeste. Para homens, houve tendência decrescente nos eventos nas regiões Sul e Sudeste.33

Estudo que avaliou 166.514 procedimentos de angioplastia coronariana para tratamento de DIC realizados em 180 hospitais, entre 2005 e 2008, reportou mortalidade hospitalar média de 2,3% (mínimo 0%, máximo 11,4%), que variou por região geográfica, sendo menor no Sudeste (2,0%) e maior no Norte (3,6%). A taxa de mortalidade foi maior entre mulheres e nos pacientes acima de 65 anos.34

As mulheres submetidas a RVM têm maior mortalidade e mais complicações pós-operatórias, apesar de menor carga aterosclerótica. O aumento da mortalidade no momento da RVM é maior em idades mais jovens do mais avançadas, estimando-se um risco três vezes maior de morte em mulheres com idade < 50 anos, apesar do ajuste para os FR.35

Estudo realizado no período de 1996 a 2016 com dados do SIM corrigidos por garbage code [causas que não devem ser consideradas como causa básica de morte ou são inespecíficas, sendo, portanto, consideradas insuficientes em termos de prevenção, como, por exemplo, códigos I50 da CID-10 (insuficiência cardíaca) e R96 (morte súbita), entre outras] e subnotificação analisou as tendências da mortalidade por IAM de acordo com sexo, regiões do Brasil e residência na capital versus não capital. Os autores relataram que a taxa de mortalidade por IAM padronizada por idade diminuiu 44% no país, com diferenças regionais significativas (+5% no Norte, +11% no Nordeste, -35% no Centro-Oeste, -68% no Sudeste e -85% no Sul). As variações temporais foram mais pronunciadas nas mulheres e nas capitais. A taxa padronizada por idade de mortalidade por IAM corrigida diminuiu 49% e 23% entre as mulheres que viviam nas capitais e em outras municipalidades, respectivamente.36

Outro estudo realizado com dados do SIM observou um declínio de aproximadamente 2,2% nos últimos 20 anos para o IAM nas regiões geográficas com maior desenvolvimento (Sudeste, Sul e Centro-Oeste), estabilização na região Norte e aumento na região Nordeste. Os autores também previram que essa tendência se prolongará até o ano 2030. Essas variações foram provavelmente relacionadas às melhorias no desenvolvimento social, nos FRCV, no acesso ao sistema de saúde e sua cobertura e à melhor discriminação nas codificações das declarações de óbito nas regiões Norte e Nordeste.37

No registro VICTIM, foram avaliados 878 pacientes com diagnóstico de IAM com supradesnivelamento de segmento ST (IAMCSST) admitidos em quatro hospitais com capacidade para realizar angioplastia primária em Sergipe, sendo um público e três privados, no período de dezembro de 2014 a junho de 2018. Desses pacientes, 33,4% eram mulheres. Do total, apenas 53,3% dos pacientes foram submetidos à reperfusão miocárdica (134 mulheres versus 334 homens). As mulheres apresentaram taxas significativamente menores de angioplastia primária (44% versus 54,5%; p = 0,003) e significativamente maiores de mortalidade hospitalar (16,1% versus 6,7%; p < 0,001) do que os homens.38

Outro estudo unicêntrico prospectivo realizado em Recife com 709 pacientes consecutivos com IAMCSST (36% de mulheres; média de idade, 61 anos), no período de fevereiro de 2018 a fevereiro de 2019, observou que as mulheres eram mais velhas (63,13 anos versus 60,53 anos, p = 0,011), mais frequentemente apresentavam HAS (75,1% versus. 62,4%, p = 0,001), DM (42,2% versus 27,8%, p < 0,001) e dislipidemia (34,1% versus 23,9%, p= 0,004), além de serem menos submetidas à intervenção coronariana percutânea (ICP) por acesso radial (23,7% versus 46,1%, p < 0,001) do que os homens. A taxa de mortalidade intra-hospitalar foi significativamente maior nas mulheres em comparação com os homens (13,2% versus 5,6%, p = 0,001) e sexo feminino mostrou-se um preditor independente de mortalidade intra-hospitalar (OR 2,79; IC 95%, 1,15 – 6,76; p = 0,023).39

2.3. Prevalência e Incidência

Segundo dados do estudo GBD 2019, a taxa de prevalência de DIC padronizada por idade no Brasil foi de 1.046 (II95%, 905; 1.209) por 100 mil mulheres e 2.534 (II95%, 2.170; 2.975) por 100 mil homens (Tabela 2.1).31Houve uma diferença entre as regiões brasileiras na prevalência padronizada por idade de DIC nas mulheres, que foi maior nas regiões Sudeste e Sul e menor na região Norte (Figura 2.3C).31 Houve redução do percentual da taxa padronizada de prevalência de DIC por 100 mil habitantes nas mulheres entre os anos de 1990 e 2019, de -2,4 (II95%, -4,2; -0,5), mas discreto aumento nos homens, de 1,4 (II95%, -0,4; 3,3), nesse mesmo período (Tabela 2.1 e Figura 2.4C).

O estudo GBD 2019 estimou uma incidência de DIC de 260.661 (II95%, 230.100-293.617) eventos (principalmente infarto do miocárdio) no Brasil em 2019. Em todos os grupos etários, a DIC teve maior incidência nos homens do que nas mulheres (Tabela 2.1). Em 2019, a taxa de incidência de DIC padronizada por idade foi 78 (II95%, 69; 88) por 100 mil mulheres e 148 (II95%, 130; 166) por 100 mil homens. Houve uma diferença entre as regiões brasileiras na incidência de DIC padronizada por idade nas mulheres, que foi maior nas regiões Sudeste e Sul e menor na região Norte (Figura 2.3D).31 Houve redução do percentual da taxa padronizada de incidência de DIC por 100 mil habitantes entre os anos de 1990 e 2019 nas mulheres, -11,8 (II95%, -14,7; -8,5), e nos homens, -11,8 (II95%, -14,7; -9), nesse mesmo período (Tabela 2.1 e Figura 2.4D).

A prevalência do IAM em mulheres é menor nas jovens do que em outras faixas etárias, mas existem tendências preocupantes nos últimos anos, dado que a proporção atribuível a pacientes jovens (35-54 anos) aumentou de 27% para 32% nas últimas duas décadas, com maior aumento de mulheres jovens (21% a 31%).40

A prevalência de MINOCA é maior nas mulheres. O estudo VIRGO (Variation in Recovery: Role of Gender on Outcomes of Young AMI Patients), realizado entre 2008 e 2012, incluiu prospectivamente 2.690 pacientes com IAM e idades entre 18 anos e 55 anos em 103 hospitais, na proporção de mulheres para homens de 2:1. Nos 2.374 pacientes submetidos a estudo angiográfico coronariano, as mulheres apresentaram cinco vezes mais chances de ter MINOCA do que os homens (14,9% versus 3,5%; OR 4,84; IC 95%, 3,29 – 7,13). As mulheres com obstrução coronariana significativa eram mais propensas a estar na menopausa (55,2% versus 41,2%; p < 0,001) ou ter um histórico de diabetes gestacional (16,8% versus 11,0%; p = 0,028). Cabe ressaltar que a mortalidade de 1 e 12 meses nos pacientes com MINOCA foi semelhante à mortalidade por obstrução coronariana nos mesmos 1 e 12 meses.30

2.4. Carga de Doenças

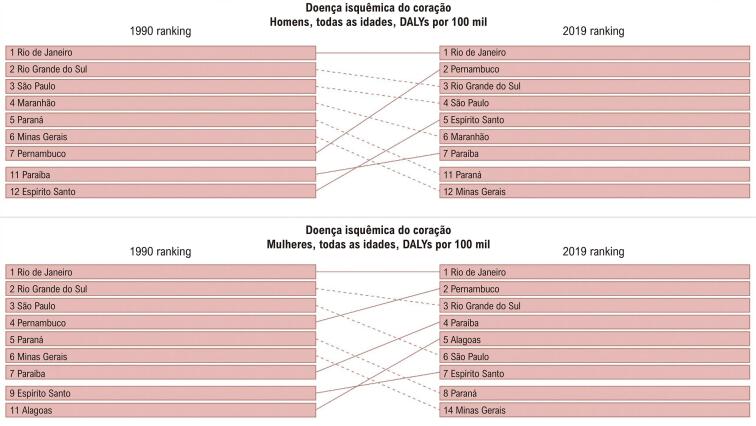

O estudo do GBD 2019 estimou taxa padronizada de DALYs por DIC por 100 mil habitantes de 1.088,4 (992,8; 1.158,9) nas mulheres e de 2.116,5 (II95%, 1.989,9; 2.232,2) nos homens (Tabela 2.1). Em 2019, DIC foi a segunda causa mais comum de DALYs no Brasil em mulheres, após complicações neonatais, e homens, após violência interpessoal.31 Essas taxas foram heterogêneas nas regiões geográficas brasileiras e a tendência das taxas de DALYs padronizadas por idade de 1990 a 2019 nas mulheres assemelhou-se à das taxas de mortalidade (Figura 2.3B). As unidades da federação com maior número de DALYs perdidos por DIC por 100 mil habitantes nas mulheres em 2019 foram Rio de Janeiro, Pernambuco, Rio Grande do Sul, Paraíba, Alagoas e São Paulo, nessa ordem (Figura 2.5).

Figura 2.5. – Ranking das taxas de DALYs devidos a doença isquêmica do coração, por 100 mil habitantes, de acordo com as unidades da federação e por sexo, no Brasil, em 1990 e 2019.

Fonte: Estudo Global Burden of Diseases (GBD) 2019.31

Entre os anos de 1990 e 2019, houve maior redução do percentual da taxa padronizada de DALYs por DIC por 100 mil habitantes nas mulheres, -52,7 (II95%, -56,1; -49,3), do que nos homens, -47,3 (II95%, -50,4; -44) (Tabela 1 e Figura 4B).

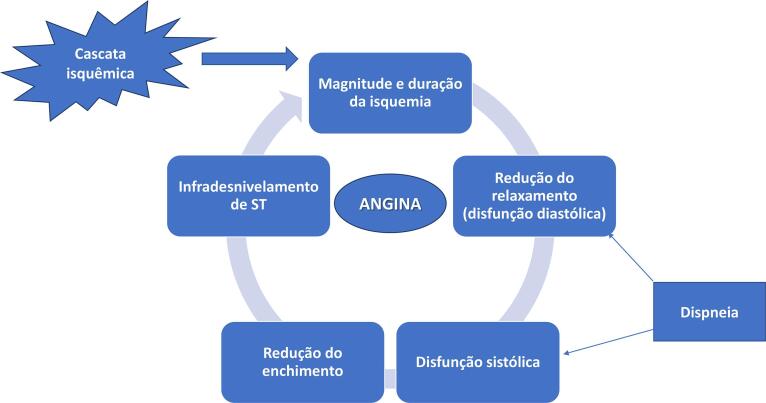

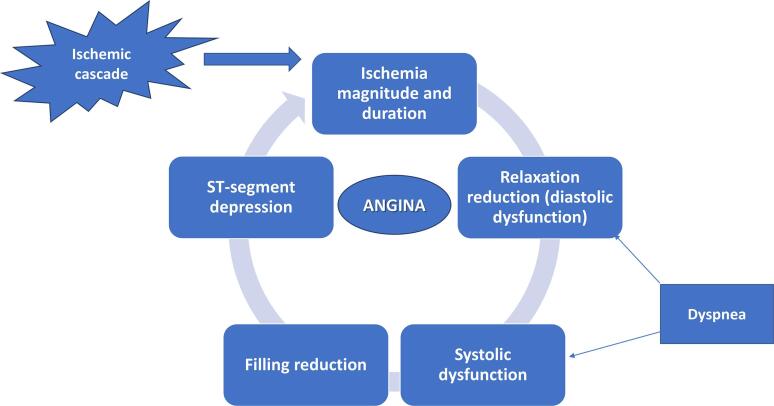

Figura 4.1. – Fisiopatologia da cascata isquêmica de equivalentes anginosos.

2.5. Fatores de Risco

Os FR tradicionais, como HAS, hiperlipidemia, DM, tabagismo, dieta pouco saudável e sedentarismo, são prevalentes nas mulheres com DIC, mas caminham lado a lado com os FR emergentes nas mulheres, como distúrbios metabólicos, distúrbios relacionados à gravidez, distúrbios autoimunes, apneia do sono, doenças crônicas, baixo nível socioeconômico, burnout e fatores psicossociais, como depressão e ansiedade.41

No estudo PURE (Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiological Study), 202.072 indivíduos com idade entre 35 anos e 70 anos, de comunidades urbanas e rurais, em 27 países, entre janeiro de 2005 e maio de 2019, foram acompanhados por uma média de 9,5 (IQR: 8,5–10,9) anos. As mulheres tiveram uma menor carga de FRCV usando dois escores de risco tradicionais diferentes (INTERHEART e Framingham). Estratégias de prevenção primária (estilo de vida saudável e uso de medicamentos comprovados) foram mais frequentes em mulheres, que, por sua vez, apresentaram menor incidência de DCV. No entanto, tratamentos de prevenção secundária para DIC foram menos frequentes em mulheres do que em homens. As diferenças entre mulheres e homens em relação a tratamentos e resultados foram mais marcantes em países de baixa e média renda, com poucas diferenças em países com alta renda, naqueles com ou sem DCV e DIC prévias.42

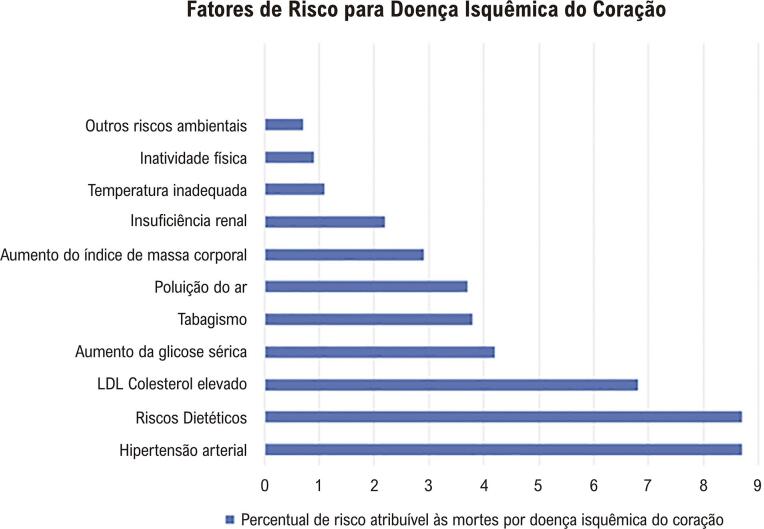

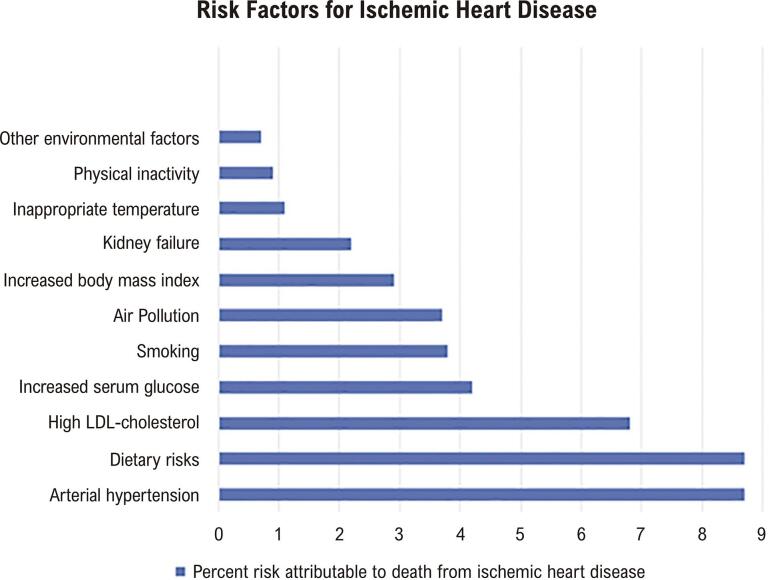

Os FR atribuíveis a DIC podem ser vistos na Figura 2.6. A HAS e os riscos dietéticos lideram o ranking dos FR atribuíveis a DIC, em ambos os sexos, mundialmente.28

Figura 2.6. – Ranking dos fatores de risco atribuíveis a doença isquêmica do coração no mundo, em ambos os sexos, em 2021.

Fonte: Estudo Global Burden of Diseases (GBD) 2019.28

No estudo caso-controle derivado do estudo VIRGO, com 2.264 pacientes com IAM (18-55 anos) e 2.264 controles pareados, 3.122 (68,9%) eram mulheres, com mediana de idade de 48 (44-52) anos. Os seguintes sete FR representaram coletivamente a maior parte do risco total de IAM em mulheres (83,9%) e homens (85,1%): DM [OR 3,59 (IC 95%, 2,72-4,74) em mulheres versus 1,76 (1,19-2,60) em homens]; depressão [OR 3,09 (IC 95%, 2,37-4,04) em mulheres versus 1,77 (1,15-2,73) em homens]; HAS [OR 2,87 (IC 95%, 2,31-3,57) em mulheres versus 2,19 (1,65-2,90) em homens]; tabagismo atual [OR 3,28 (IC 95%, 2,65-4,07) em mulheres versus 3,28 (2,65-4,07) em homens]; história familiar de infarto prematuro do miocárdio [OR 1,48 (IC 95%, 1,17-1,88) em mulheres versus 2,42 (1,71-3,41) em homens]; baixa renda familiar [OR 1,79 (IC 95%, 1,28-2,50) em mulheres versus 1,35 (0,82-2,23) em homens]; hipercolesterolemia [OR 1,02 (IC 95%, 0,81-1,29) em mulheres versus 2,16 (1,49-3,15) em homens]. Houve diferenças significativas entre os sexos nas associações de FR: HAS, depressão, DM, tabagismo atual e história familiar de DM tiveram associações mais fortes com IAM em mulheres jovens, enquanto a hipercolesterolemia teve uma associação mais forte em homens jovens.43

Estudo com 10.112 pacientes (29% mulheres) com DIC recrutados na Europa, Ásia e Oriente Médio entre 2012 e 2013 relatou que, em comparação com os homens, as mulheres eram menos propensas a atingir as metas de colesterol total [OR 0,50 (IC 95%, 0,43-0,59)], colesterol de lipoproteína de baixa densidade [OR 0,57 (IC 95%, 0,51-0,64)] e glicose [OR 0,78 (IC 95%, 0,70-0,87)], ou ser fisicamente ativas [OR 0,74 (IC 95%, 0,68-0,81)] ou não obesas [OR 0,82 (IC 95%, 0,74-0,90)]. Em contraste, as mulheres tiveram melhor controle da PA [OR 1,31 (IC 95%, 1,20-1,44)] e eram mais propensas a não fumar [OR 1,93 (IC 95%, 1,67-2,22)] do que os homens. Os autores concluíram que o controle para prevenção secundária dos FR relacionados com a DIC foi geralmente pior nas mulheres do que nos homens.44

2.6. Conclusão

A DIC contribui significativamente para a morbimortalidade das mulheres. Embora as taxas de mortalidade, DALYs, prevalência e incidência de DIC tenham diminuído ao longo dos últimos 20 anos, os dados indicam que a mortalidade por DIC nas mulheres jovens entre 35 anos e 54 anos está aumentando. O reconhecimento, a discussão, a educação e o tratamento apropriado da DIC nas mulheres são necessários para reduzir os gaps no diagnóstico e tratamento, além dos desfechos desfavoráveis nas mulheres.

3. Bases Fisiopatológicas da Doença Aterotrombótica

3.1. Introdução

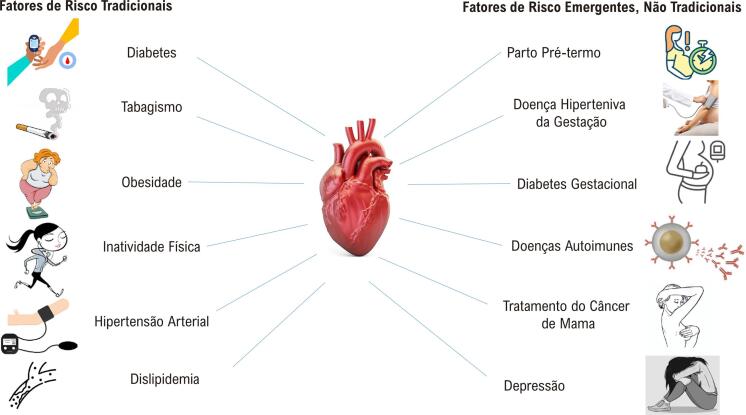

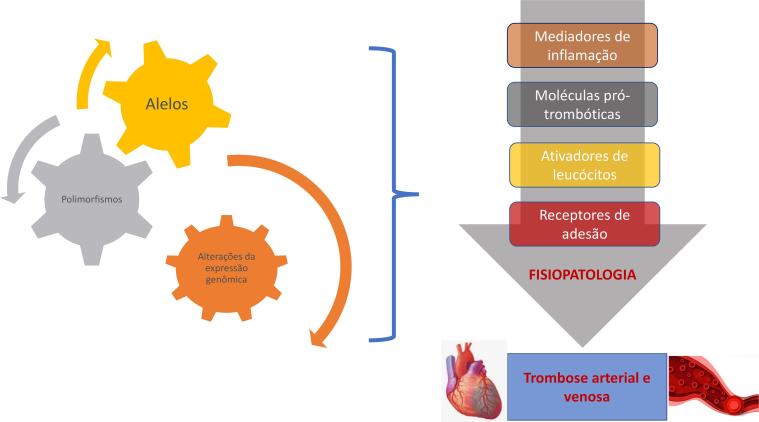

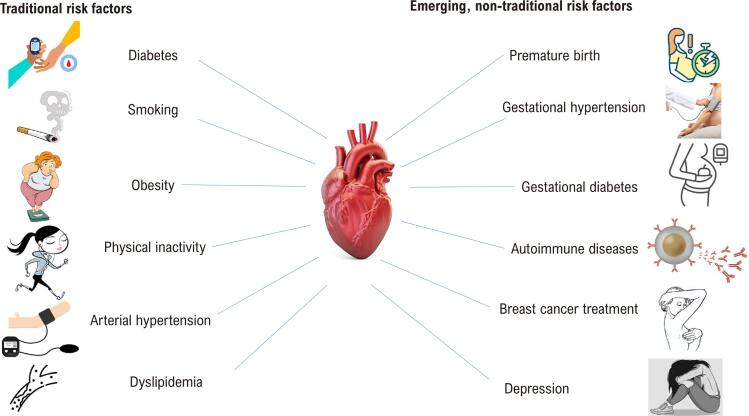

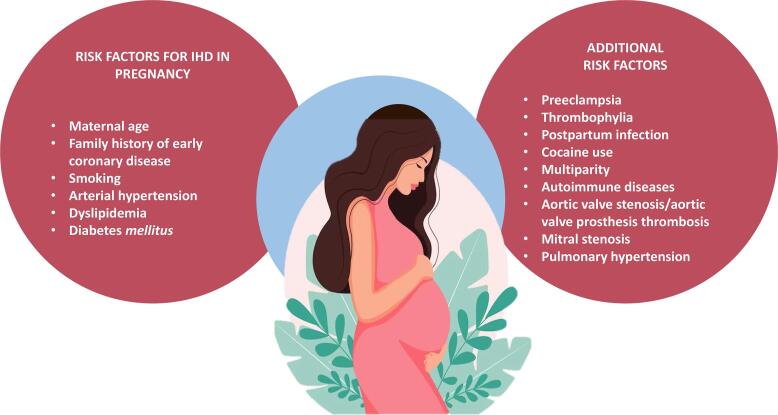

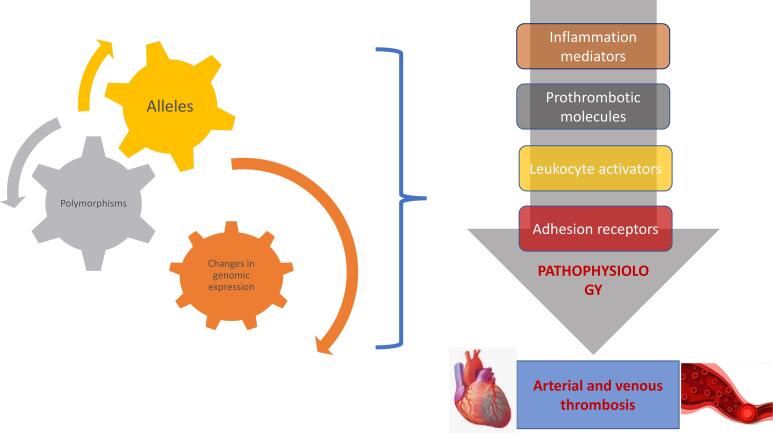

O reconhecimento de FR tradicionais para a DCV aterosclerótica, bem como de FR emergentes e não tradicionais únicos ou mais frequentes nas mulheres, e de seus diferentes impactos contribui para o novo entendimento dos mecanismos que levam aos piores desfechos nas mulheres (Figura 3.1). Maior detalhamento sobre a importância dos FR no sexo feminino pode ser visto no capítulo subsequente.

Figura 3.1. – Fatores de risco tradicionais e não tradicionais para a doença aterosclerótica cardiovascular na mulher.

As apresentações podem ser agudas, como MINOCA, que representa 3% a 15% dos casos, ou estarem relacionadas a casos de INOCA.45,46 O critério diagnóstico para MINOCA é a presença de IAM sem lesões obstrutivas (> 50%) em qualquer artéria epicárdica e ausência de diagnóstico alternativo.45-47

Os mecanismos fisiopatológicos envolvidos na MINOCA incluem ruptura de placa coronariana, DEAC, vasoespasmo, disfunção microvascular coronariana e embolismo/trombose. Importante destacar síndromes que mimetizam clinicamente MINOCA, como Takotsubo, miocardite e cardiomiopatia não isquêmica.48

3.2. Ruptura de Placa

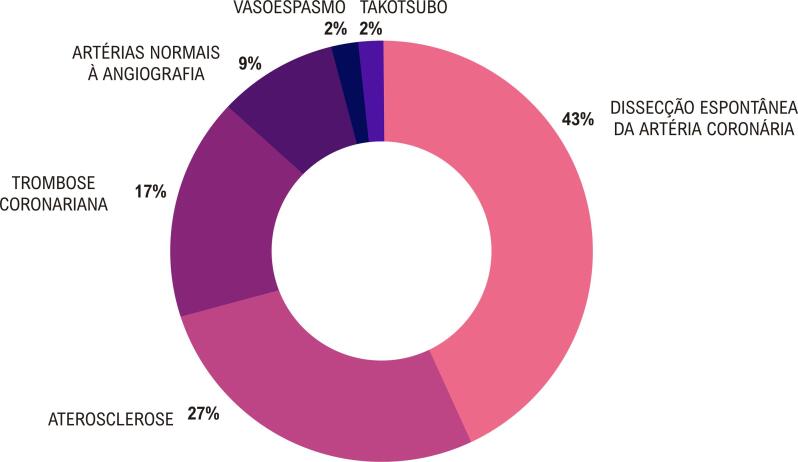

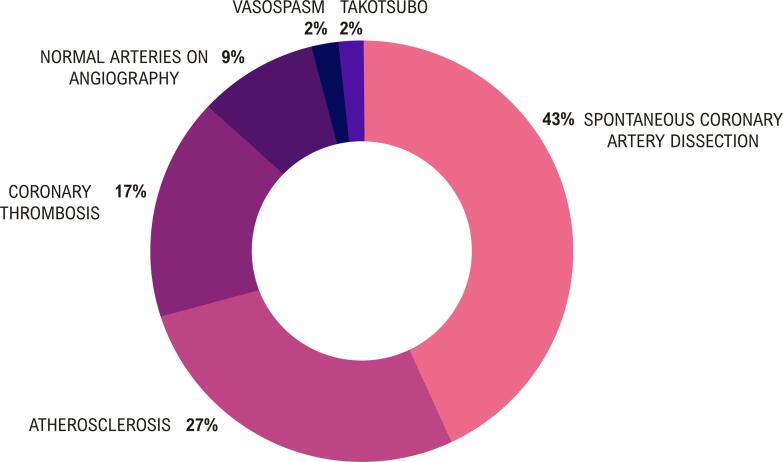

É considerado um termo amplo que envolve ruptura, erosão e nódulos calcificados nas artérias. A ruptura da placa com formação trombótica é a manifestação usual das SCA, mas pode não obstruir a luz do vaso. A erosão é a formação de trombo adjacente à superfície luminal, resultado de apoptose celular e recrutamento de neutrófilos. Os nódulos calcificados usualmente são identificados por imagem intravascular como protrusões na luz do vaso, podendo ocorrer fratura dos nódulos com acúmulo de fibrina na capa fibrosa.48 O sexo feminino e tabagismo estão associados à maior incidência de erosão do que de ruptura da placa. As alterações intravasculares podem ser detectadas por ultrassom ou tomografia de coerência óptica (OCT). O Estudo HARP demonstrou que ruptura de placa foi a causa mais frequente de MINOCA, sendo evidenciada em 43% das mulheres com essa condição.49

3.3. Dissecção Espontânea de Coronária

A DEAC resulta da formação de um falso lúmen arterial na ausência de doença aterosclerótica significativa. Existem dois mecanismos descritos, um envolvendo laceração da camada íntima e resultando em falso lúmen (inside-out) e outro onde ocorre uma hemorragia intramural com ou sem ruptura da camada íntima (outside-in).48 Os fatores predisponentes são múltiplos, como fatores genéticos, sexo feminino, gestação e terapia com estrógenos, displasia fibromuscular, doenças inflamatórias sistêmicas, além de fatores externos, como estresse emocional, atividade física intensa e uso de drogas estimulantes. Dados de registros internacionais apontam para DEAC como a principal causa de IAM no período perigestacional, ocorrendo mais no terceiro trimestre da gestação e logo após o parto.50

De acordo com as características angiográficas, quatro tipos de DEAC são descritos: tipo 1: parede arterial evidente com múltiplos lúmens radiolúcidos; tipo 2: um segmento com estreitamento difuso (normalmente > 20mm) e segmento normal proximal e distalmente (tipo 2A) ou estreitamento difuso que se estende até a extremidade distal do vaso (tipo 2B); tipo 3: um segmento curto de estenose (< 20mm) que mimetiza aterosclerose; tipo 4: caracterizado por dissecção com oclusão total abrupta de um segmento coronariano distal. De acordo com as diretrizes internacionais, a DEAC que resulta em obstrução tipo 4 não configura MINOCA, sendo que os demais tipos com lesões não obstrutivas ou não identificadas na angiografia são incluídos nessa classificação.51

3.4. Espasmo Coronariano

O espasmo coronariano como causa de isquemia é diagnosticado quando há dor torácica, com ou sem alteração isquêmica no ECG e vasoconstrição > 90% na angiografia, espontânea ou induzida com acetilcolina ou ergonovina. O mecanismo fisiopatológico é uma hiper-reatividade da camada muscular tanto das artérias epicárdicas quanto da microcirculação, embora não completamente elucidado.52 Alguns indivíduos têm gatilhos distintos que induzem espasmo, como estresse, hiperventilação, períodos diurnos e ciclos sazonais (clusters), sugerindo alterações intracelulares e pós-receptores relacionados com a hiper-reatividade. O tabagismo e a etnia asiática são descritos como fatores predisponentes, enquanto os demais FR tradicionais não parecem relacionados a maior risco. Alguns estudos sugerem que as mulheres são mais sensíveis a espasmo induzido por acetilcolina que ergonovina.53

3.5. Disfunção Microvascular Coronariana

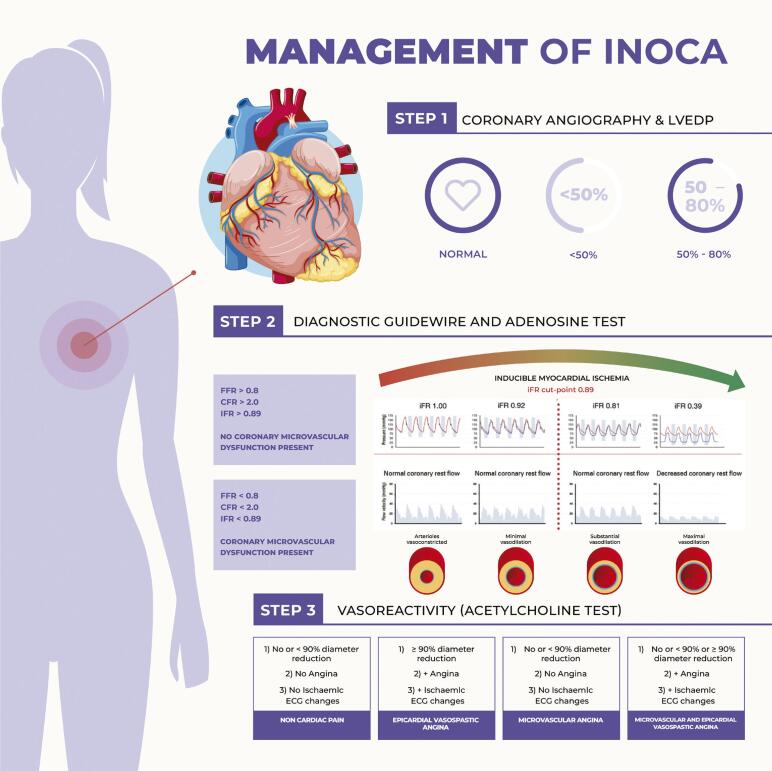

A circulação coronariana microvascular compreende vasos com calibre inferior a 0,5mm de diâmetro, não visualizados na angiografia convencional, embora representem mais de 70% da resistência vascular coronariana.54A disfunção microvascular coronariana é definida como alteração dessa reserva de fluxo coronariano (RFC) ou o aumento da resistência intramiocárdica na ausência de obstrução de artérias epicárdicas. A avalição da RFC pode ser feita através de medidas não invasivas, com doppler ou termodiluição. A RFC é expressa como a razão entre o fluxo em hiperemia máxima e o fluxo em repouso. Um valor < 2,0 é considerado alterado. O índice de resistência máximo é calculado como o produto da pressão coronariana distal em máxima hiperemia e o tempo do fluxo médio, sendo um valor ≥ 25 indicativo de disfunção da microcirculação. O diagnóstico de doença da microcirculação foi recentemente proposto pelo COVADIS (Coronary Vasomotor Disorders International Study) Group, levando em consideração achados de isquemia, ausência de doença obstrutiva e evidência de função microvascular alterada.54

Do ponto de vista fisiopatogênico, as causas parecem ser diversas e complexas. Dois endótipos são descritos: estrutural e funcional, que muitas vezes coexistem. No aspecto estrutural, existe disfunção endotelial, remodelamento arteriolar e rarefação de capilares, o que leva a uma diminuição do incremento do fluxo coronariano em repouso e aumento da demanda durante esforço. A manifestação funcional está relacionada ao acoplamento cardíaco-coronário ineficiente, resultado do aumento do tônus microvascular durante pico do exercício e durante o repouso, levando a uma maior demanda de oxigênio do miocárdio no cenário de reserva vasodilatadora esgotada saturada.48,52

Vários estudos demonstraram diferenças relacionadas ao sexo na resposta aos testes funcionais, indicando que as mulheres apresentam mais disfunção microvascular coronariana e vasoespasmo epicárdico em comparação com os homens.53

3.6. Embolia e Trombose

A embolização de artéria epicárdica sem substrato de aterosclerose é uma causa incomum de MINOCA e, usualmente, um diagnóstico de exclusão ou presuntivo.55 O National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center Group classifica essa condição como possível quando existe evidência de embolia/trombose em artéria coronária sem aterosclerose, embolização concomitante para outras artérias ou múltiplos locais e/ou na evidência de fatores predisponentes para formação de êmbolos. Várias causas são descritas para fonte de êmbolos, como diretas, paradoxais, iatrogênicas ou mesmo hipercoagulabilidade sistêmica. As fontes diretas incluem trombos formados no apêndice atrial esquerdo (AAE) na vigência de FA, no VE e nas válvulas mitral e aórtica, bem como em segmentos coronarianos proximais. Os êmbolos podem ter origem hematogênica ou de conteúdo tissular outro, como neoplasia e debris valvares. Indivíduos com shunts direito-esquerdo, como a presença de comunicação atrial, forame oval patente, malformações arteriovenosas, podem apresentar embolização paradoxal. O incremento de procedimentos invasivos coronarianos, valvares e de acesso sistêmico também tem sido relacionado com casos de embolização coronariana.45,55

3.7. Síndrome de Takotsubo