Highlights

-

•

Youth make decisions to vape based on multiple and intersecting factors.

-

•

Individual determinants of intentions played a significant role in deciding not to vape.

-

•

Youth reported multiple mediating determinants that promoted vaping, especially the school environment.

-

•

Males and females reported a few different influences on vaping decision-making (e.g., sports among males).

-

•

Health promotion efforts should account for multiple determinants to vaping.

Keywords: Vaping, E-cigarette, Youth, Adolescence, Qualitative, Behaviour change

Abstract

Vaping rates among Canadian youth are significantly higher compared to adults. While it is acknowledged that various personal and socio-environmental factors influence the risk of school-aged youth for vaping uptake, we don’t know which known behavior change factors are most influential, for whom, and how. The Unified Theory of Behavior (UTB) brings together theoretically-based behavior change factors that influence health risk decision making. We aimed to use this framework to study the factors that influence decision making around vaping among school-aged youth. Qualitative interviews were conducted with 25 youth aged 12 to 18 who were either vaped or didn't vape. We employed a collaborative and directed content analysis approach and the UTB constructs served as the coding framework for analysis. Gender differences were explored in the analysis. We found that multiple intersecting factors play a significant role in youth decision making to vape. Youth who vaped and those who did not vape reported similar mediating determinants that either reinforced or challenged their decision-making, such as easy access to vaping, constant exposure to vaping, and the temptation of flavors. Youth who didn't vape reported individual determinants that strengthened their intentions to not vape, including more negative behavioral beliefs (e.g., vaping is harmful) and normative beliefs (e.g., family disapproves), and strong self-efficacy (e.g. self-confidence). Youth who did vape, however, reported individual determinants that supported their intentions to vape, such as social identity, coolness, and peer endorsement. The findings revealed cohesion across multiple determinants, suggesting that consideration of multiple determinents when developing prevention messages would be beneficial for reaching youth.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Under the Tobacco and Vaping Products Act (TVPA), e-cigarettes containing nicotine were legalized in Canada in 2018 (Health Canada, 2019). Although preventing distribution to youth is enforced by the TVPA, vaping rates among youth are significantly higher compared to adults (Health Canada, 2019). In 2021, 29 % of Canadian youth aged 15–19 reported ever trying vaping, and 13 % reported vaping in the past 30 days (Statistics Canada, 2022). In comparison, adults aged 25 and older reported ever trying and past 30-day vaping at 13 % and 4 % respectively (Statistics Canada, 2022). A decrease in vaping behaviors was noted during the COVID-19 pandemic, which was attributed to recommendations for social distancing, not being in a school environment, and less access to older peers who could purchase products for younger youth (Hopkins & Al-Hamdani, 2021). Despite this initial decrease during the pandemic, vaping behaviors among youth have risen to pre-pandemic rates (Smith, 2021).

It is well established that tobacco use behaviors are influenced by sex and gender (Bottorff et al., 2014, Johnson et al., 2009), which has lent to the development of more meaningfully tailored interventions (e.g., Richardson et al., 2013). Emerging evidence indicates that sex and gender also influence vaping uptake. For example, males are more likely to have ever tried vaping compared to females (Statistics Canada, 2021). Additionally, vape tricks were found to be highly important to female youth, but male youth placed more importance on experiencing a nicotine rush from vaping (Al-Hamdani, Hopkins, & Davidson, 2021). In another study examining gender differences in reasons for vaping and type of products used, the authors found that the most common reason for vaping among females was because it was perceived as less harmful to others, whereas the most common reason among males was the perception that e-cigarettes are less harmful than combustible cigarettes (Yimsaard et al., 2021). In addition, they found that males were more likely to use e-liquids with higher nicotine concentrations, and tank style devices with larger volume capacities compared to females (Yimsaard et al., 2021). Moreover, biological sex differences exist regarding the effects of nicotine; due to estrogen, females metabolize nicotine quicker than males, thus finding quitting more challenging (Kong, Kuguru, & Krishnan-Sarin, 2017). Additional evidence on the influence of sex and gender on vaping among youth is needed. For example, research is needed to understand how gender influences factors that lend to youth deciding whether to vape or not.

Nicotine is associated with several negative effects, especially among youth. Nicotine is carcinogenic, alters brain waves, and increases blood pressure and heart rate (Canadian Public Health Association, 2021). As nicotinic acetylcholine receptors are maturing, youth are particularly susceptible to the effects of nicotine on mental health and brain development (Oostlander, Hajjar, & Pausé, 2020). Increased impulsivity, mood swings and depression are seen among youth who vape (Leslie, 2020). Vaping may predispose youth to long-term nicotine addiction (Government of Canada, 2020), which encourages other behaviors, such as combustible cigarette use (Hammond et al., 2019), and uptake of psychostimulant drug use (Ren & Lotfipour, 2019). Although e-cigarettes are marketed as a smoking cessation tool and are perceived to produce less dependence, there is evidence that indicates otherwise. For example, a study examining young adult vaping behavior in Poland noted exclusive users of e-cigarettes have a higher incidence of nicotine dependence than exclusive combustible cigarette smokers; Fagerstrom scores (nicotine dependence level) were twice as high among those who vaped compared to tobacco smokers (Jankowski, Zejda, Lubanski, & Brozek, 2019). Furthermore, many youth report vaping as a mindless habit, engaging in vaping unconsciously, thereby lending to the perception that they are not addicted (Quorus Consulting Group Inc., 2020).

It is well established in the literature that various socio-environmental and personal factors influence uptake of vaping among youth, including enticing advertising tactics (Weeks, 2019), peer influence (Ren and Lotfipour, 2019, Rocheleau et al., 2020), developmental stage (Ren & Lotfipour, 2019), and determinants of health (e.g., low income) (Tercyak et al., 2021, Vu et al., 2020). What we don’t know is the most pertinent behavioral factors underpinning the decision-making process around youth vaping, nor do we know how gender might influence these behavioral factors. Understanding the most salient factors that lend to the decision to vape is critical for effectively addressing the issue of youth vaping, and resonating with youth through prevention efforts. Qualitative research is particularly needed to better understand youth-decision making processes because qualitative research enables contextualized youth voices and experiences to be heard, ultimately providing youth-driven evidence to underpin intervention efforts that are responsively designed.

1.2. UTB framework

For this descriptive qualitative study, we employed the Unified Theory of Behavior (UTB) (Jaccard and Levitz, 2013, Jaccard et al., 2002, Jaccard et al., 2012) to investigate and understand the most salient evidence-based factors underpinning youth decision-making around vaping. Utilizing theoretical frameworks to guide research is key to providing an evidence-based focus for the study, bringing forward meaning, connecting to existing scholarship, and identifying strengths and limitations (Collins & Stockton, 2018). Since we are focusing on a health behavior (that of vaping), utilizing a behavior-change theory to understand factors that influence vaping behavior was appropriate for this study. We specifically wanted to employ one that accommodates the vast array of known factors that influence health behaviors (e.g., self-efficacy, social norms) versus one factor alone (e.g., self-efficacy). The UTB is novel in this way, enabling the exploration of a comprehensive list of factors with youth in order to determine the most salient ones in context. Employing The UTB consists of 10 determinants: five are individual determinants focused on intention (behavioral beliefs, normative beliefs, self-concept, emotions, self‐efficacy), four are mediating determinants influenced the translation of intention to actual behavior (knowledge, environment, salience, and habitual processing), and one more recently added construct is focused on split-second decision-making (Jaccard & Levitz, 2013). These constructs have been used to study adolescent problem behaviors such as risky sexual behavior and binge drinking (Jaccard and Levitz, 2013, Jaccard et al., 2002, Sadzaglishvili, 2015). A few studies have utilized the UTB framework to understand help-seeking among youth and young adults with mental health problems (Ben-David et al., 2019, Ben-David et al., 2022, Lindsey et al., 2013, Munson et al., 2012). More recently, we have applied this theory in a study examining vaping decision making among Indigenous youth (Struik, Werstuik, Sundstrom, Dow-Fleisner, & Ben-David, 2022). Similarly, the purpose of this study is to understand factors that influence the decision to vape or to not vape among school-aged youth.

2. Methods

2.1. Sample and recruitment

Through purposive sampling (Campbell et al., 2020), we recruited youth who lived in British Columbia, Canada, were between the ages of 12 and 18, were currently attending school, and either vaped or did not vape. We recruited youth through online ads on Instagram, which were posted by a third party (PH1 Research). In the ad, youth were invited to click on the ad link, respond to screening questions, and then invited to contact a study researcher if they were deemed eligible. This study received approval from the University of British Columbia’s Behavioral Research Ethics Board (#H20-02312).

2.2. Data collection

All eligible participants provided informed consent. Youth under the age of 16 provided parental consent in addition to their assent to participate in the study. Participants also filled out a demographic questionnaire, which asked about their demographic information (e.g., age, gender), social media use, and use and exposure to smoking and vaping. Youth were then invited to participate in a ∼45 min semi-structured interview via UBC zoom to talk about factors that influence their decision-making around vaping. These interview questions were structured around the UTB constructs. For example, in order to gather information around how youth perceive social norms around vaping, we asked questions like, “Who in your life approves of vaping? Who disapproves? What messages do you get about vaping from important people in your life?” Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview of interview questions used to tap into each UTB construct. Each interview participant received a $20 gift card to thank them for their time.

Table 1.

Unified Theory of Behavior Constructs and Questions.

| Construct | Definition | Example of Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Intentions | ||

| Behavioral beliefs | The perceived advantages and disadvantages that young people associate with vaping. | What do you perceive as the pros and cons of using vaping products? |

| Social Norms | The endorsement or disapproval from significant social relationships (e.g., family or friends) regarding a young person's decision to vape. | Are there significant individuals in your life that encourage or discourage your use of vaping products? |

| Self-Concept/Social Image | Young people's decisions may be affected by the type of image they associate with youths who vape or choose not to vape | Imagine young people who would or would not choose to use a vaping product. How would you describe them? |

| Emotions | The emotional responses that young people experience when contemplating the use of vaping products. | Do you experience any particular emotions when you think about using vaping products? |

| Self-Efficacy (combined with knowledge) | The degree of confidence that young people have in their ability to successfully vape or abstain from vaping. | Could you please describe the strategies or coping mechanisms you use or will use to either vape or avoid vaping? |

| Moderators of intention-behavior | Factors that could influence or change the correlation between a youth's intention to vape and their actual behavior. | Are there any specific conditions or factors that might alter your decision to vape, even if you originally intended to? |

| Knowledge (combined with skills) | The extent of information that youth possess and the skills they employ to either initiate or abstain from vaping. | Can you describe the information or skills that you utilize or would utilize to either begin vaping or to resist vaping? |

| Environmental | Circumstances in the surrounding context that can either hinder or promote the initiation or abstention from vaping. | Can you identify any factors or situations in your environment that would make it more challenging or simpler for you to either start vaping or abstain from vaping? |

| Salience | Environmental prompts that aid in either initiating or abstaining from vaping. | Are there any specific triggers or reminders in your surroundings that could potentially assist you in either starting to vape or avoiding vaping? |

| Habits | Automatic processes that influence a youth's decision to either start or abstain from vaping. | Can you mention any habitual behaviors you have that might contribute to either your decision to start vaping or your effort to abstain from it? |

| Split-second decision-making | Youth confronted with a situation last minute that gets in the way of them vaping or not vaping despite previous opposite intention. | Can you think of a scenario where you might suddenly decide not to vape, even if you had intended to? |

2.3. Data analysis

The interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed by the research team, and then integrated into NVivo 1.3 (QSR International) qualitative data management software program for analysis. The dataset was broken down into four datasets to note differences and similarities across four groups: female youth who vape, male youth who vape, female youth who do not vape, and male youth who do not vape. The UTB served as the coding framework, and then two researchers engaged in collaborative and simultaneous conventional and directed content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005) of four interview transcripts (two with youth who vape, two with youth who do not vape) via zoom to develop codes for each construct. Once the coding framework was agreed upon, one researcher independently coded the remaining transcripts, noting nuances within the datasets and consulting with the team as needed. Once the analysis was complete, the lead author then reviewed the final coded datasets with SBD who has experience applying this UTB framework among youth and young adults accessing mental health services in a North America context (Ben-David et al., 2019, Ben-David et al., 2022). The lead author then merged the datasets of youth who vape and those who do not vape, retaining noteworthy gender differences for presentation in results and discussion.

3. Results

3.1. Sample

In total, 25 youth between the ages of 12 and 18 (average 16) participated in this study. About half 52 % (n = 13) of the participants were female and 48 % (n = 12) of the participants were male. This distribution of genders applies to all the findings mentioned unless specifically differentiated. The majority (88 %) (n = 22) of the sample was White/Caucasian and born in Canada, again, a statistic spanning both genders. All youth, regardless of gender, were attending school, one of which was attending University. In relation to smoking, most participants (88 %) (n = 22), across both genders, did not smoke. In relation to vaping, 44 % (n = 10) of the participants, not restricted to a particular gender, reported that they currently vaped either all the time or sometimes, 32 % (n = 8) of the participants reported that they did not currently vape but that they tried vaping in the past, and the remaining 24 % (n = 6) reported that they never vaped. Only those that reported current vaping either all the time or sometimes were classified as youth who vape in this study. Most (68 %) (n = 17) youth, across both genders, reported that no one vaped in their home. Except for two youth that did not answer the demographic question, only 2 (8 %) of the youth participants reported that none of their friends vaped, and the remaining (88 %) (n = 22), across both genders, reported that some or most of their friends vaped.

In relation to social media use, most youth participants across both genders used Instagram (96 %) (n = 24), Snapchat and YouTube, both at 92 % (n = 23), and TikTok (72 %)(n = 18) sometimes or all the time. Youth participants reported only sometimes using Facebook and Messenger, both at 56 % (n = 14), encompassing both male and female respondents. Regarding seeing vaping content on social media, participants, without any gender-specific trends, reported seeing vaping all the time or sometimes most commonly on Snapchat (84 %) (n = 21), Instagram (80 %) (n = 20), TikTok (60 %) (n = 15), and finally, YouTube (28 %) (n = 7).

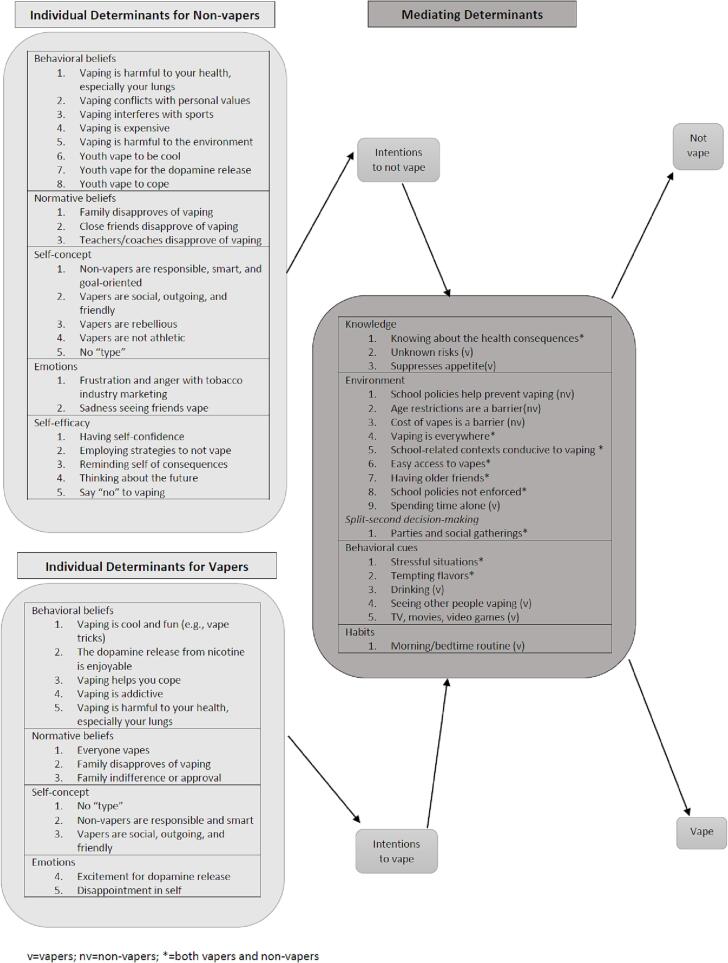

3.2. Factors influencing youth who do not vape

Participants who didn't vape reported a large number of factors that influenced their intentions to not vape, which covered all five individual determinants (behavioral beliefs, normative beliefs, emotions, self-concept, and self-efficacy). For behavioral beliefs, non-vaping youth primarily reported negative beliefs about vaping (e.g, bad for your lungs). For normative beliefs, there was a strong negative orientation towards vaping across their family and social networks (e.g., widespread disapproval). In relation to emotions, youth participants across both genders reported negative feelings (e.g., anger) towards vaping and vape companies. When asked about their self-concept, participants who didn't vape reported mixed associations between vaping and personal characteristics. For example, some said that there was “no type”, while others described those who vaped as “outgoing” and “rebellious”, and those who didn't vape as “smart” and “athletic”. In relation to self-efficacy, youth reported a number of factors that reinforced their intentions to not vape, including confidence in their refusal, reflection, and avoidance strategies. Split-second decision-making was reported as something that challenged their decision to not vape, which was primarily in the form of social gatherings and parties. While habitual processes did not factor into the decision-making among participants who didn't vape, they reported various influences in relation to the other three mediating determinants (behavioral cues, knowledge, and environment) that either reinforced or challenged their decision to not vape. Overall, youth participants reported a number of factors under these mediating determinants that challenged their decision to not vape, including the widespread use of e-cigarettes in their social environments, accessibility of vaping, feeling stressed or bored, and tempting flavors. See Table 2 for an overview of all factors influencing non-vaping youth, and Fig. 1 to see a visual diagram of these factors.

Table 2.

Factors influencing youth who do not vape (n = 14).

| UTB construct | # | Exemplary quote |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral beliefs | ||

| Vaping is harmful to your health, especially your lungs | 14 | “The people I know who like use a vape a lot- like even just walking up the stairs they’re like hacking, they can barely breathe just walking up the stairs and doing simple tasks.” Participant 3 |

| Youth vape because they are curious | 14 | “There’s a lot of people doing it and [a lot of] curiosity around it for those who’ve never tried it before. And it’s marketed as something really fun and enjoyable apparently.” Participant 12 |

| Vaping conflicts with personal values (e.g., health, role model) | 12 | “I would feel really disappointed in myself. And I know that a lot of other people in my life would be really disappointed in me. And I don’t want to take that chance.” Participant 8 |

| Youth vape to fit in and be cool | 11 | “For a lot of [vapers] I feel like it’s just kind of a coolness factor, they see other people doing it and they just want to fit in” Participant 5 |

| Vaping interferes with sports (stronger for males) | 9 | “One of my friends that is very active and does play sports, when they vape right before a game, they’ll experience like headaches and they’re out of breath a lot faster than they would be.” Participant 5 |

| Youth vape to cope with stress and hardship | 6 | “I think knowing what my triggers are like….stress…” Participant 25 |

| Vaping is expensive | 6 | “I heard some kids at my school who vape say that it’s kind of expensive.” Participant 12 |

| Vaping is harmful to the environment (females) | 2 | “[Vaping] might not have the best impact on the world in terms of manufacturing them and stuff.” Participant 18 |

| Normative beliefs | ||

| Family disapproves | 15 | “My brother does not promote it at all and regrets it. My parents, family, [and] myself disapprove of vaping.” Participant 2 |

| Close friends disapprove | 8 | “My friend group right now would not approve of it.” Participant 12 |

| Teachers/coaches disapprove | 8 | “Even from the teachers and principals, I’ve heard quite a lot of the school faculty and staff make comments about the kids who vape.” Participant 5 |

| Self concept | ||

| Non-vapers are responsible, smart, and goal-oriented | 7 | “I would say definitely more ambitious like my friends that don’t vape are definitely more focused on school or sports just like have their priorities more in order I would say.” Participant 4 |

| Vapers are social, outgoing, and friendly | 6 | “They’re all very friendly, upbeat, and happy. And they just- they just smoke cause it gives them a happy, somewhat euphoric feeling, makes them feel good. Um, but they’re not sketchy at all.” Participant 5 |

| Vapers are rebellious | 5 | “When I did hang out with my friends that vaped, they were the bad type of friends; it’s mostly the rebels who vape.” Participant 19 |

| Vapers are not athletic | 5 | “I don’t know anyone who plays serious sports that vapes.” Participant 8 |

| There is “no type” of vaper or non-vaper | 5 | “[Vapers] are not really any different any other person besides that they have a nicotine addiction.” Participant 21 |

| Emotions | ||

| Frustration and anger with tobacco marketing | 4 | “I just wish that the advertisements for vapes weren’t targeted towards children. They say they’re not but they very clearly are. The bright colours, the smells and all of that.” Participant 5 |

| Sadness seeing friends put their health at risk | 5 | “If it is used for its actual purpose to stop smoking, that’s good; otherwise, why would you do it. Why do they not have a regard for their life?” Participant 18 |

| Self-efficacy | ||

| Having self-confidence | 14 | “I’m a bit more confident on the way that I stand and I stand my ground when people try and get you to try stupid things like [vaping].” Participant 8 |

| Employing strategies to not vape (e.g., listening to music, walking away, avoiding known high vape areas) | 8 | “If I’m in any stressful situation, I tend to listen to music, zone out and figure things out. With a vaping head rush, its only momentary, not a permanent fix.” Participant 16 |

| Reminding self of consequences | 6 | “When I first started playing basketball when I started vaping and could barely last on the court and cough my lungs out. I barely had the stamina to keep up. That’s a big reason [to not vape] – so I can stay in shape.” Participant 21 |

| Thinking about the future | 4 | “I’m graduating this year. I have a budget for money so it just doesn’t make sense to put vaping money aside when I’m trying to save up and if I want to go to college or anything, it just doesn’t make sense money-wise.” Participant 1 |

| Saying “no” | 4 | “I say no. If they keep pushing, I just leave. I usually just sternly say no. Sometimes I get an “aww come on man”. But it’s an easy no for me.” Participant 2 |

| Split-second decision | ||

| Parties and social gatherings | 8 | “If I were go to like a small get-together and seeing everyone else around me vaping and I’m not, there’s kind of this awkward pressure that I should be doing it.” Participant 5 |

| Knowledge | ||

| Knowing about the health consequences | 11 | “I’m also like a soccer player looking to play varsity and that could like impact that negatively for me as well so it’s more just about making the smart choice for me. I just remember what’s best for that and my health too.” Participant 4 |

| Environment | ||

| Vaping is everywhere | 10 | “To not vape is definitely going against like everything [and] everybody.” Participant 1 |

| School is conducive to vaping (commute, bathrooms, lunchtime) | 12 | “I have seen my friend take a hit inside class even without the teacher seeing. The bathrooms are a spot where everyone vapes.” Participant 21 |

| Vaping is easy to access online | 6 | “You can go online and order one and you don’t need to show any ID or anything.” Participant 3 |

| Vaping is easy to access through older peers | 5 | “If you have friends who are old enough to go and buy it for you, that makes it easy.” Participant 8 |

| School policies help prevent vaping | 4 | “If you were caught vaping in the school you would be suspended for a little bit and the vape would be taken away from you and you could not claim it, you would have to get a parental guardian to claim it. So that could also be a big factor.” Participant 5 |

| Cost is a barrier | 3 | “[Vapers] go into debt or whatever trying to pay for that habit and I’m just like it just doesn’t seem worth it at all.” Participant 1 |

| Age restrictions are a barrier | 3 | “Um, definitely it’s hard to get a vape, like to get one if you’re underage you have to like have friends of a friend buy it for you.” Participant 7 |

| Behavioral cue | ||

| Feeling stressed or bored | 3 |

“If I was stressing about an exam, I would go into the bathroom, take a few hits, come back and then I would feel a lot more relaxed.” Participant 5 “I feel like smoking is something people do that just to fill time, you know, just to fill time” Participant 24 |

| Tempting flavors | 2 | “All the flavours and packaging and stuff that’s all like really colourful and it really appeals to the younger people, they’re like cotton candy or birthday cake flavoured.” Participant 8 |

Fig. 1.

Individual and mediating determinants to vaping among school-aged youth.

Only a couple of differences between males and females were found in relation to behavioral beliefs. First, male participants more often reported a negative impact on sports as a reason to not vape compared to females. Second, a few females participants reported a concern for the environment, but no males brought this up as a reason to not vape.

3.3. Factors influencing youth who vape

Participants who did vape reported factors within four out of the five individual determinants that influenced their vaping intentions (behavioral beliefs, normative beliefs, emotions, and self-concept). Their overall behavioral beliefs were positive towards vaping in that they thought it was cool, makes you feel good, and is helpful for coping. Their normative beliefs reflected a mix of disapproval and approval of vaping by others in their family and social networks. Emotional factors included both negative (disappointment in self) and positive (excitement for dopamine release) aspects, and factors related to self-concept were similar to that of youth who didn’t vape in that they were mixed. Factors in relation to self-efficacy were not present. Split-second decision-making was present in the form of social contexts (e.g., parties and social gatherings), and was conducive to vaping. Factors related to all four mediating constructs (knowledge, behavioral cues, environment, and habitual processes) were reported to influence their decision-making. Similar to the youth who didn't vape, those who vaped reported similar factors within these mediating constructs that facilitated and promoted their vaping, including the omnipresence of vaping within their social environments, accessibility of vape products, stress and boredom, and tempting flavors. See Table 3 for an overview of these factors, and Fig. 1 for a visual diagram.

Table 3.

Factors influencing youth who vape (n = 11).

| UTB Construct | # | Exemplary quote |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral beliefs | ||

| Vaping is cool and fun (e.g., vape tricks) | 11 | “There's the tricks too that look kind of cool. Like, for me, personally, I don't care much for the nic. Like the nicotine. A lot of my friends do. I'm only in it for the tricks to be honest.” Participant 29 |

| Vaping makes you feel good because of the dopamine release | 7 | “Well, it started when my friend had one and I tried it and…I felt that it was all fun and games. That was with no nicotine in it….but then one of my friends’ friends had six nicotine in his and I tried that and it was the best feeling ever. It was just amazing. So I figured I'd get my own.” Participant 22 |

| Vaping makes you feel out of breath | 6 | “It does mess with your lungs a bit. Like when I played competitive soccer, if I had a game, I wouldn't vape like the day before or something just to clear up my lungs….I have noticed like you don't, you can't run as well; you run out of breath faster.” Participant 26 |

| Vaping is addictive | 3 | “It is very addictive. So, you know, the nicotine, you need it constantly and you're going to need more and more as you use it more and more. Yeah.” Participant 23 |

| Vaping helps you cope | 2 | “Not being in control of how I am feeling at the time – stress and anger takes over. Vaping helps me deal with the stress and anger.” Participant 16 |

| Normative beliefs | ||

| Everyone vapes | 11 | “I think it's because everyone does [vape]. It's a social thing…I don't know, it's nice. I enjoy it.” Participant 14 |

| Family indifference or approval | 10 | “My mother would rather me vape than other things. My immediate family don’t see it as their favorite thing but they rather me vape than do other things.” Participant 10 |

| Family disapproves | 10 | “My Dad…wasn’t happy at all because he’s been struggling with addiction with cigarette products, so when he knew that I was vaping he was really, really disappointed.” Participant 9 |

| Self concept | ||

| No “type” for vapers and nonvapers | 8 | “I cant give any stereotypes to people who vape. Like me and my friends all do really well in school and make good decisions and we vape. Cant give one stereotype.” Participant 17 |

| Non-vapers are responsible and smart | 6 | “People who don’t are more goal oriented. That’s why athletes may not.” Participant 15 |

| Vapers are social, outgoing and friendly | 3 | “I feel like it's the type of people who do other stuff, like drink and drugs and stuff. People who want to be cool and fit in. They are probably people who are kind of “popular” if you want to use that word.” Participant 14 |

| Emotions | ||

| Excitement for dopamine release | 3 | “Um, I guess like happiness kind of? It does make you feel really good inside, even if it's just for like five minutes.” Participant 23 |

| Disappointment in self | 3 | “I would say if I was addicted to something, I would be sad if anything. When I do vape, which is maybe twice a month, it makes me sad because I am breaking my trust which I have with myself.” Participant 6 |

| Split second decision | ||

| Parties and social gatherings | 8 | “Mm, I think um, a lot of you know, of your like peers. You know, so like if you’re in a big group of people and they all have one and they’re all doing it you’re probably going to be tempted to do it too.” Participant 11 |

| Knowledge | ||

| Health consequences | 11 | I don’t want my lungs to crap out on me in 5 years when I’m you know, 21. But honestly, a lot of the times, kids don’t really care about health risks. Like we understand them, we know them, yet, people continue to do it.” Participant 11 |

| Unknown risks warrants use | 3 | “Ah, well, solid research. A big, big case of all people dying from vaping and it might change my perspective.” Participant 29 |

| Suppresses appetite (female only) | 1 | “I started vaping because I am anorexic and nicotine suppresses your appetite… Just knowing that it is a stimulant and gives you energy for a short time. Knowing it supresses your appetite and gives you something to do.” Participant 17 |

| Environment | ||

| School is conducive to vaping | 8 | “If you go to school, it is not hard to vape.” Participant 6 |

| Easy access to vapes online and offline | 7 | “It's pretty easy to get access to any of that stuff. Like no matter what the laws are, young kids are always going to get alcohol, they're always going to get weed, they're always going to get what they want. There's always someone who can get someone something.” Participant 23 |

| Spending time alone (no parental supervision) | 5 | “When your parents are home, you can just do it in your room with the door closed unless they…just burst into your room without notice.” Participant 23 |

| Having older friends | 4 | “Since I am under 17, sometimes buying vape juice is hard. Luckily one of my friends is 19 so he gives me stuff sometimes.” Participant 10 |

| School policies are not enforced | 7 | “Everyone has them, by everyone [I mean] friends and people at school. There are just not very many rules about it - they are not very enforced. I think everyone does so that makes me more inclined to do it I guess.” Participant 14 |

| Behavioral cues | ||

| Tempting flavors | 3 | “Definitely would not smoke cigarettes because they are gross, but I guess since vape juice is more flavored it is more tempting.” Participant 14 |

| Drinking | 2 | “More tempting is like I would say when you're like under the influence and out of the home for some reason. I'm not sure why. But it's the same with everybody. Like when anybody is under the influence of alcohol, you get this urge for nicotine. Like I want it and I need it.” Participant 23 |

| Feeling stressed or bored | 9 | “I think it’s also [very] tied to your emotions. So if you’re having a bad day or you’re feeling very stressed or angry, you might want to use your friends or do something like that [vape] to really help relieve the stress kind of thing.” Participant 11 |

| Other people vaping | 6 | “Something to get me thinking about it [vaping] is seeing my friends do it.” Participant 6 |

| Watching TV, movies, video games (male only) | 2 | “Like if I'm playing a video game or something and it's been like half an hour, I get drawn to it I guess.” Participant 26 |

| Habitual processes | ||

| Morning/bedtime routine (male only) | 2 | “When I wake up, when I go to bed, everything. Yeah, like from the second I wake up, I'm vaping all throughout the day.” Participant 22 |

A few differences between male and female youth who vaped were found in relation to the mediating constructs knowledge, behavioral cues, and habitual processes. In relation to knowledge, one female participant mentioned that knowing about nicotine as an appetite suppressor made vaping tempting. In relation to behavioral cues, watching movies and video gaming were conducive to vaping among the male participants. Finally, habitual processes that aligned with vaping (morning/bedtime routine) were only reported by a couple of males.

4. Discussion

In this study, we aimed to understand decision making in relation to vaping among school-aged youth. We utilized the UTB to frame this qualitative study and understand salient constructs in youth decision-making around vaping. This model lent to an ability to ground theoretical and evidence-based constructs that influence behaviors in participant experiences and contexts. In this regard, only salient constructs for the various populations under study were brought forward, which is a major strength of using this framework to guide this study.

When looking at the findings holistically, individual determinants that influence intentions to vape appear to play the strongest role in behavior regardless of external mediating variables. Specifically, youth who made the decision to not vape reported behavioral beliefs (e.g., vaping is harmful), normative beliefs (e.g., friend and family disapproval), and self-efficacy (e.g., refusal skills) that supported their choice to not vape. Conversely, youth who did vape held more beliefs and perceptions that reinforced their decision to vape compared to their non-vaping counterparts, including that vaping helps you cope, makes you look cool, feels good, and is endorsed by their peers. While adolescents are at higher risk for engaging in health risk behaviors, like vaping, due to the neurological development that hallmarks this stage of development (e.g., slow development of the prefrontal cortex), researchers emphasize an interplay with contextual factors, including social and family influences (normative beliefs), personal values and goals (behavioral beliefs), and positive personal skills development (self-efficacy) in health risk decision making (National Academies of Sciences, 2019). Our findings, in combination with this evidence, cue to the importance of strengthening reported individual determinants (e.g., building self-efficacy) when designing prevention interventions.

One of the most interesting aspects of using the UTB in this study is how it revealed similar findings across multiple behavior change constructs. For example, concern among youth who did not vape, especially male youth, about the negative impact that vaping may have on their ability to engage in sports or physical activities (e.g., gym) permeated their behavioral beliefs (e.g., vaping interferes with sports; health is important), normative beliefs (e.g., coaches disapprove), self-efficacy (e.g., reminding self of consequences with sports engagement), self-concept (e.g., vapers are not athletic), and knowledge (e.g., vaping is harmful to your health). Our findings provide theoretical evidence for developing prevention messages that tap into multiple and intersecting behavior change constructs (versus just one) to address vaping. For example, rather than creating a message simply about how e-cigarettes damage the lungs and hinder athletic performance (behavioral beliefs), which is typical of prevention messages (Struik, Sharma, Rodberg, Christianson, & Lewis, 2023), messages could tap into multiple constructs around vaping and athletic performance, like share the impact of vaping on performance (knowledge), reinforce the value of health for sustaining sports and exercise (behavioral beliefs), tie in the words of coaches (normative beliefs), and invite youth to reflect on how vaping has consequences on athletic performance (self-efficacy).

Youth who vaped also brought forward the impact of social influences on developing a vaping identity across multiple constructs. More specifically, behavioral beliefs (e.g., vaping is cool), normative beliefs (e.g., everyone vapes; family is indifferent), self-concept (e.g. vapers are social, outgoing, and friendly), split-second decision making (e.g., parties), environment (e.g., school contexts; exposure online), and behavioral cues (e.g., seeing other people vaping) reveal how one’s social identity can become quickly entrenched with vaping. Given that adolescents are at a developmental stage where they are establishing their social identity and they are particularly vulnerable to establishing an identity as a vaper (Donaldson et al., 2021), combating this via prevention efforts is critical. Our findings provide multiple intersecting constructs that could be tapped into from a prevention intervention (e.g., denormalizing vaping) and policy perspective (e.g., reducing exposures in schools) to reach youth, revealing the importance of ensuring that prevention efforts intersect with policy efforts.

It was also interesting to note that both youth who vaped and youth who did not vape shared the challenges of split second decision making when it came to vaping. This relatively new construct added to the UTB (Jaccard & Levitz, 2013) appeared to be particularly relevant to vaping among youth. Despite experiencing the same pressures to make that split-second decision to vape (e.g., parties and social gatherings), youth who didn't vape appeared to be “primed” by their individual determinants that supported non-vaping intentions, and ultimately to choose not to vape. Raising awareness in a prevention campaign about this type of pressure to vape (e.g., being at a party) may be a productive way to help youth anticipate and be proactive, versus reactive in contexts that result in split-second decision-making to vape.

Our findings also revealed that school contexts are a challenging space for youth when it comes to vaping, especially when combined with what youth described as low policy enforcement. School is a key place where youth form social connections, and vaping has been described as a mediator to connecting with peers (Quorus Consulting Group Inc., 2020). In addition, school can cause stress and anxiety (e.g., homework, grades), which is another reason that youth are turning to vaping (Quorus Consulting Group Inc., 2020). Combining these school-related factors with the fact that vaping devices are increasingly compact and easy to conceal, often have fruity or minty flavours, and that vapor can be inhaled and exhaled inconspicuously (Dormanesh & Allem, 2022), and also that school staff are unprepared to respond to the issue of vaping (Quorus Consulting Group Inc., 2020), lends to unprecedented rates of vaping in schools (Chadi, Hadland, & Harris, 2019), to which youth in this study confirm. In light of these findings, efforts to educate school staff, and to raise awareness of and implement school policies is a priority area for addressing youth vaping.

It is important to acknowledge that these findings cannot be similarly applied across all youth populations. This was brought forward in our study with Indigenous youth, where their cultural practices and their ongoing experiences of colonialism played a major role in which UTB constructs surfaced as salient, and how they surfaced. Researchers emphasize that it is critical to recognize the impact of colonial constructs, like reservations, on psychological distress experienced by Indigenous peoples (McNamara et al., 2018), and we found that this rang true for decision making around vaping among Indigenous youth (Struik et al., 2022). We also found that engaging in cultural practices was an important means to avoiding vaping (e.g., suggesting engaging in cultural activities to build their self-efficacy, like beadwork) (Struik et al., 2022). In other words, their individual determinants (e.g. self-efficacy) were directly tied to their culture. Consideration for context and culture is critical when exploring the most salient UTB constructs that influence vaping among other subpopulations of youth.

Some of the gender-related findings in this study warrant attention. It was interesting that female participants expressed concerns about the environmental impact of vaping (e.g., plastic waste; vapour). Researchers have found that females are more environmentally conscious, and have a greater perceived sense of responsibility to make environmentally friendly choices (Hampel et al., 1996, Hojnik et al., 2019), and this is inclusive of adolescent females (Hampel et al., 1996). Given that researchers have brought forward environmental concerns in relation to vaping (Pourchez, Mercier, & Forest, 2022), bringing this forward in prevention messaging may be a novel way to reach young females. Another noteworthy finding was that one female reported vaping as a way to suppress their appetite. The use of tobacco products, including vaping, as an appetite suppressant among females is not new (Mason, Tackett, Smith, & Leventhal, 2022). In light of evidence that eating disorders have been on the rise since the pandemic (Toulany et al., 2022), attention to the gender-based vulnerabilities in prevention efforts must be given due attention. For example, it will be important to ensure that harmful stereotypes are not reinforced in messages (e.g., using tall slim models in the messages) like they have been in smoking prevention messaging (Struik, Bottorff, Jung, & Budgen, 2012). Furthermore, males listed video gaming and watching movies as behavioral cues to vape, which is not surprising given that e-cigarette marketing has proliferated digital media channels, including video games and movies (Goodwin, 2021), and more males are video-gamers than females (Leonhardt & Overå, 2021). It would be interesting to apply a gender-based analysis to the content of e-cigarette advertisements in video-games to identify potential gender-based marketing tactics. Lastly, the influence of sports on vaping decisions was especially significant among male participants, highlighting the potential to utilize gender-based norms, such as the association of boys with sports, to promote health.

5. Limitations and strengths

There are a few noteworthy limitations and strengths of this study. First, our reliance on online advertisements for recruitment meant that we only collected data from young people with internet access, excluding those without. Second, this study excludes youth who are not attending school, and is not capturing the voices of youth who are not immersed in this context, which plays a role in influencing their behavior. However, this also enabled a window into the everyday lives of school-attending youth that has been difficult to capture, providing evidence for taking tangible steps to address this issue at the school level. Third, the sample is representative of a single community in British Columbia, Canada. In this regard, the socio-geographical contexts of vaping among youth in other geographical locations with different policies may be different. Given that the North American context of vaping is similar, however, the findings hold high transferability potential. Finally, based on previous research findings from our study with Indigenous youth, we know that social location matters. Therefore, another limitation of this study is that the findings are representative of a largely White sample. The use of the UTB to frame the study is a major strength of this study as it provides a theoretical evidence base to move forward in prevention efforts. In addition, disaggregating the findings by vaping status and gender also enabled us to present similarities and differences that need attention in future research and health promotion efforts.

6. Future research

The results of this study highlight the complex relationship between individual determinants of intentions to vape and determinants that mediate intention to actual behavior. Considering these findings, there are several critical paths for future research to address. First, we need to delve deeper into the nuances of determinants and their role in preventing or encouraging vaping among youth. For instance, research could specifically investigate how perceptions of vaping's impact on sports performance can be leveraged to strengthen prevention messages aimed at youth, especially males who show significant concern in this area. The rise of gym culture among youth, especially male youth (Skauge & Seippel, 2022), may present as an opportunity to intervene vaping. However, caution must be applied in this regard as focusing solely on physical performance and appearance as a reason to not vape comes with potentially dangerous implications (e.g., body image issues, injuries, reinforcing harmful gender stereotypes, etc.). Message framing in this regard must fully account for these potential harms, and consult with youth through research about if and how to tap into gym culture for vaping prevention in a positive way.

Additionally, it would be beneficial to continue investigating the influence of different social contexts on youth vaping, such as school environments. Schools, due to their inherent social nature and stressors, pose a challenging context for youth vaping prevention. Research could explore effective ways of enforcing anti-vaping policies in schools, educating school staff about vaping risks, and designing interventions that decrease the social appeal of vaping in these contexts. Overall, while the study highlights the vast and complex territory yet to be explored, the study presents a significant step towards a comprehensive, theoretically-informed understanding of youth decision-making in relation to vaping. Prevention efforts would benefit from incorporating these findings into future prevention messaging and policy directions.

7. Conclusions

This study enabled the identification of factors that influence the decision to vape among school-aged youth. The UTB surfaced as a flexible model for identifying theoretically-based factors that influence vaping decision-making, which hold promise for informing vaping prevention efforts. Moreover, the focus on both youth who vape and youth who do not vape and the nuanced analysis of gender-related vaping determinants provides unique insights. This will inform future research and interventions in their efforts to tailor prevention strategies to different populations and contexts, cultivating an evidence-based, multifaceted approach to youth vaping prevention.

Author credit statement

Laura Struik: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Project administration. Sarah Dow-Fleisner: Conceptualization, Writing - review & editing. Shelly Ben-David: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Kyla Christianson: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing - review & editing. Shaheer Khan: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing - review & editing. Youjin Yang: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing - review & editing. Saige-Taylor Werstuik: Writing - original draft, Writing – reviewing & editing.

Author agreement

All authors of this paper have seen and approved the final version of this manuscript being submitted. The authors confirm that this manuscript is original work, has not received prior publication, and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Role of funding sources

This work was supported by a Canadian Cancer Society Emerging Scholar Award (Prevention) (grant#: 707156) held by Dr. Laura Struik. The Canadian Cancer Society had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Canadian Cancer Society Emerging Scholar Award (Prevention) (grant#: 707156) held by Dr. Laura Struik. We would also like to acknowledge and thank the youth who participated in this study.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Al-Hamdani, M., Hopkins, D. B., & Davidson, M. (2021). The 2020–2021 youth and young adult vaping project. https://www.heartandstroke.ca/-/media/pdf-files/get-involved/yyav-full-report-final-eng-24-3-2021.ashx.

- Ben-David S., Cole A., Brucato G., Girgis R.R., Munson M.R. Mental health service use decision-making among young adults at clinical high risk for developing psychosis. Early Intervention in Psychiatry. 2019;13(5):1050–1055. doi: 10.1111/eip.12725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-David, S., Vien, C., Biddell, M., Ortiz, R., Gawliuk, M., Turner, S., Mathias, S., & Barbic, S. (2022). Service use decision-making among youth accessing integrated youth services: Applying the unified theory of behavior. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry = Journal de l’Academie Canadienne de Psychiatrie de l’enfant et de l’adolescent, 31(1), 4–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bottorff J.L., Haines-Saah R., Kelly M.T., Oliffe J.L., Torchalla I., Poole N.…Phillips J.C. Gender, smoking and tobacco reduction and cessation: A scoping review. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2014;13(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12939-014-0114-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell S., Greenwood M., Prior S., Shearer T., Walkem K., Young S., Bywaters D., Walker K. Purposive sampling: Complex or simple? Research case examples. Journal of Research in Nursing. 2020;25(8):652–661. doi: 10.1177/1744987120927206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Public Health Association. (2021). Tobacco and vaping use in Canada: Moving forward. https://www.cpha.ca/tobacco-and-vaping-use-canada-moving-forward.

- Chadi N., Hadland S.E., Harris S.K. Understanding the implications of the “vaping epidemic” among adolescents and young adults: A call for action. Substance Abuse. 2019;40(1):7–10. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2019.1580241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins C.S., Stockton C.M. The central role of theory in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2018;17(1) 1609406918797475. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson C.D., Fecho C.L., Ta T., Vuong T.D., Zhang X., Williams R.J., Roeseler A.G., Zhu S.-H. Vaping identity in adolescent e-cigarette users: A comparison of norms, attitudes, and behaviors. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2021;223 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dormanesh A., Allem J.-P. New products that facilitate stealth vaping: The case of SLEAV. Tobacco Control. 2022;31(5):685–686. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin R.D. E-cigarette promotion in the digital world: The “Shared Environment” of today’s youth. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2021;23(8):1261–1262. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntab114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada. (2020). Risks of vaping. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/smoking-tobacco/vaping/risks.html.

- Hammond D., Reid J.L., Rynard V.L., Fong G.T., Cummings K.M., McNeill A., Hitchman S., Thrasher J.F., Goniewicz M.L., Bansal-Travers M., O’Connor R., Levy D., Borland R., White C.M. Prevalence of vaping and smoking among adolescents in Canada, England, and the United States: Repeat national cross sectional surveys. BMJ. 2019 doi: 10.1136/bmj.l2219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampel B., Boldero J., Holdsworth R. Gender patterns in environmental consciousness among adolescents. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Sociology. 1996;32(1):58–71. doi: 10.1177/144078339603200106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada (2019). Backgrounder: Regulation of vaping products in Canada. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/news/2019/12/backgrounder-regulation-of-vaping-products-in-canada.html.

- Hojnik J., Ruzzier M., Konečnik Ruzzier M. Transition towards sustainability: Adoption of eco-products among consumers. Sustainability. 2019;11(16) doi: 10.3390/su11164308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins D.B., Al-Hamdani M. Young canadian e-cigarette users and the COVID-19 pandemic: Examining vaping behaviors by pandemic onset and gender. Frontiers in Public Health. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.620748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh H.-F., Shannon S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J., Dodge T., Dittus P. Parent-adolescent communication about sex and birth control: A conceptual framework. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2002;97:9–41. doi: 10.1002/cd.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J., Levitz N. Counseling adolescents about contraception: Towards the development of an evidence-based protocol for contraceptive counselors. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;52(4):S6–S13. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaccard J., Litardo H., Wan C.K. Social psychology and cultural context. SAGE Publications; Thousand Oaks: 2012. Subjective culture and social behavior; pp. 95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Jankowski K., Zejda M., Lubanski L., Brozek E-cigarettes are more addictive than traditional cigarettes—a study in highly educated young people. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019;16(13) doi: 10.3390/ijerph16132279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson J.L., Greaves L., Repta R. Better science with sex and gender: Facilitating the use of a sex and gender-based analysis in health research. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2009;8(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-8-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong G., Kuguru K.E., Krishnan-Sarin S. Gender differences in U.S. adolescent E-cigarette use. Current Addiction Reports. 2017;4(4):422–430. doi: 10.1007/s40429-017-0176-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonhardt M., Overå S. Are there differences in video gaming and use of social media among boys and girls?—A mixed methods approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021;18(11) doi: 10.3390/ijerph18116085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie F.M. Unique, long-term effects of nicotine on adolescent brain. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2020;197 doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2020.173010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey M.A., Chambers K., Pohle C., Beall P., Lucksted A. Understanding the behavioral determinants of mental health service use by urban, under-resourced black youth: Adolescent and caregiver perspectives. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2013;22(1):107–121. doi: 10.1007/s10826-012-9668-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason T.B., Tackett A.P., Smith C.E., Leventhal A.M. Tobacco product use for weight control as an eating disorder behavior: Recommendations for future clinical and public health research. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2022;55(3):313–317. doi: 10.1002/eat.23651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara B.J., Banks E., Gubhaju L., Joshy G., Williamson A., Raphael B., Eades S. Factors relating to high psychological distress in Indigenous Australians and their contribution to Indigenous-non-Indigenous disparities. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2018;42(2):145–152. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munson M.R., Jaccard J., Smalling S.E., Kim H., Werner J.J., Scott L.D. Static, dynamic, integrated, and contextualized: A framework for understanding mental health service utilization among young adults. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;75(8):1441–1449. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, E. and M., Health and Medicine Division, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education, Board on Children, Y. and F., Committee on Applying Lessons of Optimal Adolescent Health to Improve Behavioral Outcomes for Youth, Kahn NF, & Graham R. (2019). Promoting positive adolescent health behaviors and outcomes: Thriving in the 21st century. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554988/. [PubMed]

- Oostlander S., Hajjar J., Pausé E. E-cigarette use among Canadian Youth: A review of the literature using an interdisciplinary lens. University of Ottawa Journal of Medicine. 2020;10(1):14–22. doi: 10.18192/uojm.v10i1.4626. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pourchez J., Mercier C., Forest V. From smoking to vaping: A new environmental threat? The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 2022;10(7):e63–e64. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(22)00187-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quorus Consulting Group Inc. (2020). Exploratory research on youth vaping. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2020/sc-hc/H14-347-2020-eng.pdf.

- Ren M., Lotfipour S. Nicotine gateway effects on adolescent substance use. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2019;20(5):696–709. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2019.7.41661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson C.G., Struik L.L., Johnson K.C., Ratner P.A., Gotay C., Memetovic J.…Bottorff J.L. Initial impact of tailored web-based messages about cigarette smoke and breast cancer risk on boys’ and girls’ risk perceptions and information seeking: Randomized controlled trial. JMIR Research Protocols. 2013;2(2) doi: 10.2196/resprot.2858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocheleau G.C., Vito A.G., Intravia J. Peers, perceptions, and E-cigarettes: A social learning approach to explaining E-cigarette use among youth. Journal of Drug Issues. 2020;50(4):472–489. doi: 10.1177/0022042620921351. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sadzaglishvili, S. (2015). Adolescent risk taking behaviors: The case of Georgia.

- Skauge M., Seippel Ø. Where do they all come from? Youth, fitness gyms, sport clubs and social inequality. Sport in Society. 2022;25(8):1506–1527. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, W. (2021). How the pandemic impacted vaping and smoking rates — and why it showed vaping is “here to stay.”https://www.cbc.ca/radio/whitecoat/how-the-pandemic-impacted-vaping-and-smoking-rates-and-why-it-showed-vaping-is-here-to-stay-1.6068729.

- Statistics Canada. (2021). Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey, 2020. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/210317/dq210317b-eng.htm.

- Statistics Canada. (2022). Canadian tobacco and nicotine survey, 2021. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/220505/dq220505c-eng.htm.

- Struik L.L., Bottorff J.L., Jung M., Budgen C. Reaching adolescent girls through social networking: A new avenue for smoking prevention messages. The Canadian Journal of Nursing Research = Revue Canadienne de Recherche En Sciences Infirmieres. 2012;44(3):84–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struik L., Sharma R.H., Rodberg D., Christianson K., Lewis S. A content analysis of behavior change techniques (BCTs) employed in North American vaping prevention interventions. AJPM Focus. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.focus.2023.100126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struik L.L., Werstuik S.-T., Sundstrom A., Dow-Fleisner S., Ben-David S. Factors that influence the decision to vape among Indigenous youth. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):641. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13095-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tercyak K.P., Phan L., Gallegos-Carrillo K., Mays D., Audrain-McGovern J., Rehberg K., Li Y., Cartujano-Barrera F., Cupertino A.P. Prevalence and correlates of lifetime e-cigarette use among adolescents attending public schools in a low income community in the US. Addictive Behaviors. 2021;114 doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toulany A., Kurdyak P., Guttmann A., Stukel T.A., Fu L., Strauss R., Fiksenbaum L., Saunders N.R. Acute care visits for eating disorders among children and adolescents after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2022;70(1):42–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vu T.-H.-T., Groom A., Hart J.L., Tran H., Landry R.L., Ma J.Z., Walker K.L., Giachello A.L., Kesh A., Payne T.J., Robertson R.M. Socioeconomic and demographic status and perceived health risks of E-cigarette product contents among youth: results from a national survey. Health Promotion Practice. 2020;21(1_suppl):148S–156S. doi: 10.1177/1524839919882700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks, C. (2019). How the vaping industry is targeting teens – and getting away with it. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-vaping-advertising-marketing-investigation/.

- Yimsaard P., McNeill A., Yong H.H., Cummings K.M., Chung-Hall J., Hawkins S.S.…Hitchman S.C. Gender differences in reasons for using electronic cigarettes and product characteristics: Findings from the 2018 ITC four country smoking and vaping survey. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2021;23(4):678–686. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntaa196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.