Abstract

Introduction

Pleuropulmonary blastoma is a rare, aggressive intrathoracic neoplasm of early childhood.

Case presentation

We report a case of a 4-month-old male baby who has presented with recurrent respiratory infections since birth. A surgical team was consulted due to abnormal opacification observed on a chest X-ray. An enhanced-contrast CT scan of the chest revealed a heterogenous, well-delineated mass measuring about 3,8 × 6 cm in the posterior mediastinum. A left posterolateral thoracotomy was performed. The mass was separated from the lung parenchyma, located behind the parietal pleura, and adherent to the chest wall and superior ribs. The lesion was totally removed. Histologically, the lesion was a pleuropulmonary blastoma type III. Currently, the patient is on a 6-month course of chemotherapy.

Clinical discussion

The aggressive, insidious behavior of PPB requires a high index of suspicion for diagnosis. The clinical manifestations and imaging modalities are atypical and nonspecific. However, PPB should be kept in mind when a huge solid or cystic mass is observed in the lung field on imaging.

Conclusion

Extrapulmonary pleuropulmonary blastoma is a very rare entity characterized by highly aggressive behavior and a poor prognosis. Early excision of thoracic cystic lesions in children is warranted regardless of the symptoms to avoid future mishaps.

Keywords: Pleuropulmonary blastoma, Congenital pulmonary airway malformation, Pediatric, Neoplasm, Case report

Highlights

-

•

Pleuropulmonary blastoma is a rare, highly aggressive neoplasm in early childhood located in the lung, pleura, or both.

-

•

Extrapulmonary PPB is a very rare entity of PPB with a poor prognosis.

-

•

PPB ought to be taken into consideration in the differential diagnosis of a young child's huge hemithorax mass.

-

•

The surgical treatment of PPBs includes complete surgical excision for resectable lesions. For lesions greater than 10 cm or unresectable lesions, a biopsy followed by neoadjuvant chemotherapy and excision is recommended.

1. Introduction

Pleuropulmonary blastoma (PPB) is a rare and aggressive primary malignant intrathoracic tumor in children. It can arise from the lung, pleura, or both [1]. It accounts for 0.5 % of all malignant tumors in children [1]. Despite being rare, they are considered the most common primary cancers in the lung during childhood, especially in those who are under 5 years of age. The first two years of age remain the highest risk for developing PPB, with about 90 % of the cases occurring within this age group [2,3]. PPB is characterized by blastomatous and sarcomatous features without any epithelial component, differentiating it from classical adult-type pulmonary blastoma [4]. It is a dysembryonic tumor analogous to the Wilms tumor in kidneys, neuroblastoma in the adrenals, and hepatoblastoma arising from the liver [5]. The Dehner classification provides the histologic grading system for PPB. Type I is purely cystic, type II has mixed cystic and solid elements, and type III is purely solid [3].

In this report, we describe a case of a 4-month-old baby diagnosed with a left thoracic mass in the posterior mediastinum and underwent complete excision. Histologically, the mass was a pleuropulmonary blastoma type III. Currently, the patient is receiving chemotherapy according to the protocols. The main aim of reporting this case is to highlight the importance of early intervention for thoracic cystic lesions in children to avoid misattribution and future repercussions. This surgical case was reported according to The SCARE 2020 guidelines [12].

2. Case presentation

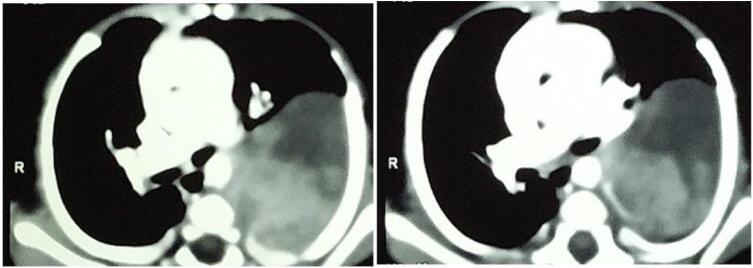

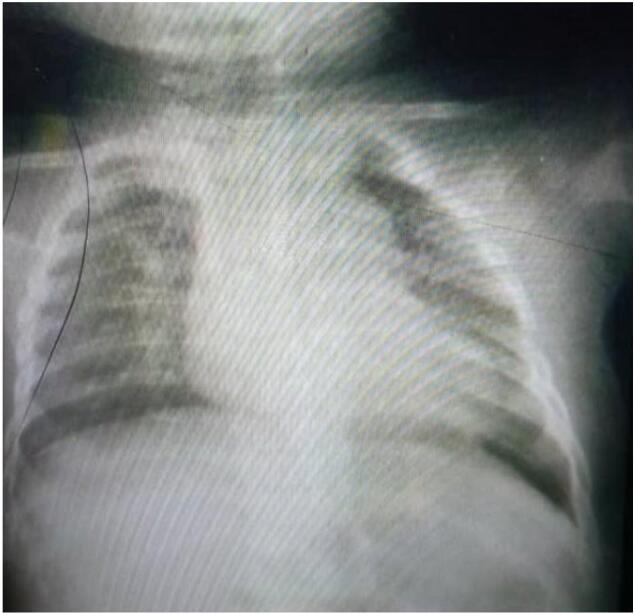

A 4-month-old male baby was admitted to the pediatric department with a history of recurrent respiratory infections since birth that sometimes necessitate hospitalization. The pediatric surgery specialty was consulted in the last admission due to an abnormal opacity detected on the chest X-ray. On evaluation, there were no signs of dyspnea or cyanosis, but a limitation in the movement of the left chest wall. Auscultation of the chest showed a relative diminishing of breath sounds in the left chest. A chest X-ray revealed a round, homogenous opacity occupying the upper 2/3 of the left chest without mediastinum shift (Fig. 1). A CT scan of the chest with IV contrast was requested and demonstrated a heterogenous, well-delineated mass measuring about 3,8 × 6 cm, located in the posterior mediastinum, and compressing the left lung (Fig. 2). No evidence of metastasis in the chest or abdomen could be appreciated. Further investigation, including ECHO-heart, was normal. The blood results were unremarkable.

Fig. 1.

An X-ray of the chest showing a spherical opacity filling the upper 2/3 of the left chest.

Fig. 2.

CT scan of the chest demonstrated a heterogeneous, well-defined mass measuring approximately 3,8 × 6 cm in the posterior mediastinum and compressing the left lung.

The decision was made to take the baby for a thoracotomy. The left chest cavity was accessed through the fourth intercostal space. Following the opening of the parietal pleura, a cystic mass was found in the left thoracic cavity (Fig. 3A), adherent to the left chest wall, located behind the parietal pleura, separated from the lung parenchyma, and compressing the upper lobe of the left lung (Fig. 3B). Due to its adherence to the superior left ribs, the mass was dissected after releasing firm adhesions, isolated from the ribs and chest wall (Fig. 3C), and excised (Fig. 4). Cauterization of the tumor's vicinity was made. An intercostal nerve block was performed for the third to fifth intercostal spaces. A 16-Fr chest tube was placed. The post-operative trajectory was uneventful, and the baby was discharged on the fifth postoperative day in stable condition. The baby was seen after one month without any complaints. A chest X-ray was repeated, and it showed full expansion of the left lung without any abnormality (Fig. 5).

Fig. 3.

Intraoperative images of the surgical excision of the tumor.

A: The tumor was recognized immediately upon accessing the left thoracic cavity through 4th intercostal space. B: The tumor was extrapulmonary and not attached to lung parenchyma after ongoing dissection. C: Advanced stage of dissection with releasing most of the tumor mass outside the field.

Fig. 4.

The surgical specimen of the neoplasm after removal.

Fig. 5.

A chest X-ray revealed a complete expansion of the left lung with no abnormalities after one month of excision.

Histopathological evaluation of the surgical specimen revealed mixed blastematous and sarcomatous features, fibrosarcoma-like areas, dystrophic calcification, foci of hemorrhage, and fibrosis combined with areas of necrosis (Fig. 6A,B,C). Ki67 immunohistochemical staining demonstrated a high mitotic proliferative index (Fig. 6D). The conclusion was pleuropulmonary blastoma type III. The patient was referred to the pediatric oncology specialty to receive adjuvant chemotherapy.

Fig. 6.

Histopathological images of the surgical specimen of the PPB type III: A& B with low power magnification (H&E 200), and C with high power magnification (H&E 400) showing a heterogeneous solid tumor composed of mixture of primitive blastomatous and sarcomatous elements. D Ki67 immunohistochemical staining revealing high mitotic activity of the tumor (400).

Currently, the patient is on a 6-month course of chemotherapy. On the first day of each month, he is given vincristine, actinomycin, and cyclophosphamide plus mesna to protect the lining of the bladder against damage from cyclophosphamide. On the 15th day of each month, he is administered adriamycin and carboplatin.

3. Discussion

PPB is a rare intrathoracic neoplasm of early childhood with an unfavorable outcome [9]. The tumor usually is located in the lung periphery, but it may be extrapulmonary with involvement of the mediastinum, diaphragm, and/or pleura [13]. Extrapulmonary PPBs are extremely rare, highly aggressive tumors that account for 25 % of all PPB cases [11].

The clinical manifestations of PPB are nonspecific. They range from fever, cough, and other symptoms of upper respiratory tract infection to being accompanied by pleural effusion, pneumothorax, chest pain, and upper abdominal pain. The imaging findings of PPB are also atypical. As a result, the rates of missed diagnosis and misdiagnosis of PPB are high [1]. In our case, the patient was suffering from recurrent respiratory infections in early infancy that necessitated hospitalization on occasion without identifying a real reason.

The preoperative diagnosis of PPB is a clinical challenge. A huge solid or cystic mass is usually found at the time of diagnosis [7]. On occasion, it may present with a pneumothorax or a big radiolucent lesion that may be misattributed as a pneumatocele. Ultrasound is a poor imaging modality for diagnosing PPB as findings are non-specific and may show a large region of consolidation without a sonographic air bronchogram [2]. The imaging findings favoring the possibility of PPB on a chest radiograph include a large mass lesion with small pleural effusion, contralateral mediastinal shift, and a lack of chest wall invasion [2].

The differential diagnosis for a chest wall mass identified on imaging in a young child is wide. For type 1 PPB lesions, the differential diagnosis includes other cystic lesions such as bronchogenic cysts, lung cysts, pneumatoceles, and pulmonary interstitial emphysema. The differential diagnosis for types II and III PPBs, particularly when they are locally aggressive, includes more common tumors such as neuroblastoma, Ewing's sarcoma, Askin tumor, and rhabdomyosarcoma. However, chest lesions that arise from the chest wall, such as Ewing's sarcoma and Askin tumors, usually demonstrate findings of chest wall involvement. Neuroblastoma typically arises in the posterior mediastinum and demonstrates chest wall involvement as rib erosion. Rhabdomyosarcoma can also involve the chest wall [2].

Type II PPB and type III PPB have metastatic potential to the brain, bone, and, rarely, liver. Thus, chest computed tomography and brain magnetic resonance imaging with a possible bone scan are required [6]. The tumor is usually located at the periphery of the lung, but it may also be located in extrapulmonary locations, such as the mediastinum, diaphragm, and/or pleura [9].In our case, the tumor was located behind the parietal pleura and had a moderate size, which made its compressing symptoms not as obvious as those of other congenital pulmonary parenchymal lesions.

According to the literature, the risk factors for PPB include pneumothorax, bilateral or multiple pulmonary cystic lesions, and DICER1 gene mutations; PPB can also be accompanied by pulmonary cystic lesions [1]. The correlation between PPB and Congenital Pulmonary Airway Malformation (CPAM) remains controversial. While some pathologists argue that there is no pathological similarity between PPB and CPAM, some clinicians have found a correlation between these two conditions in their clinical practice; however, there is no evidence of transformation between PPB and CPAM [1].

The association between DICER1 mutations and PPB is reported in approximately 66 % of the cases. Therefore, all patients with PPB should be screened for the DICER1 mutation [2]. Recent advances in genetics have identified a loss-of-function mutation in DICER1 as an etiology for this transformation in PPB. DICER1 is a microRNA synthesis gene present in the lung epithelium, and its absence results in cystic dilation and mesenchymal proliferation, leading to PPB. It is now implicated in familial tumor syndrome, which includes cystic nephroma, ovarian Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors, and ciliary body medulloepithelioma [3]. Currently, attempts to screen DICER1 mutation carriers for cystic PPB at a young age may permit the early detection of PPB type I. Subsequent surgical resection may prevent the progression to types II and III, with their higher morbidity and mortality [6].

In addition to the three types of PPB, PPB type Ir is a purely cystic tumor that lacks a primitive cell component. The r designation signifies regression or nonprogression. Type Ir was originally recognized in older siblings of pleuropulmonary blastoma patients but can be seen in very young children. A lung cyst in an older individual with a DICER1 mutation or in a relative of a pleuropulmonary blastoma patient is most likely to be Type Ir [6]. Type I cystic PPB may progress to the aggressive Type II and Type III PPB but may also regress to Type Ir, where no malignant cells are present [10].

Complete surgical resection remains the primary goal of treatment of children with PPB [3,7]. Commonly used surgical procedures include cystectomy, segmentectomy, lobectomy, and total pneumonectomy. No study to date has investigated the correlation between the surgical procedure performed and the prognosis of PPB [1]. A formal lobectomy may not be necessary when a PPB lesion is outside the normal lobes or joins with only a small pedicle [9]. On the other hand, invasion of the surrounding structures and the extreme friability of the tumor may prevent complete excision [4]. Thoracotomy is the recommended surgical approach, while thoracoscopic procedures are discouraged, except if the lesion is well delineated and R0/R1 should be obtained as anticipated in an open procedure [10].

For children with huge unresectable tumors, puncture biopsy or surgical biopsy can be performed first. After the lesion has been pathologically confirmed, the size of the tumor can be reduced by four to eight courses of chemotherapy followed by radical surgery [1]. The European Cooperative Study Group for Pediatric Rare Tumors (EXPeRT) has identified a threshold of 10 cm as a reasonable cut-off point, above which up-front biopsy followed by neoadjuvant chemotherapy is a reasonable approach [8].

Type I and Ir PPB have not been noted to metastasize and should be managed via complete resection with widely negative margins. Adjuvant chemotherapy is not typically given for Type I PPB unless there are complicating circumstances such as intraoperative tumor spill, incomplete resection, or local invasion of adjacent structures [8].In type II and type III PPB, both systemic chemotherapy and surgical resection are critical components of treatment [6,8]. Radiotherapy is only recommended in the case of a residual viable tumor after chemotherapy and second-look surgery in PPB type II-III [10].

The PPB type and the presence of distant metastasis at diagnosis are the most important prognostic factors related to treatment outcomes [6]. Moreover, the absence of pleural or mediastinal involvement is deemed an indicator of long-term survival [4]. The outcome of purely cystic PPB (types I and Ir) is better than the outcome of more aggressive types. Type II has better outcomes than type III, although both have high relapse and death rates [6]. In a large subgroup of patients that were tested at any point in the natural history of PPB, the germline DICER1 status had no impact on prognosis [6]. The overall survival rates for type I-PPB, type II-PPB, and type III-PPB are 91 %, 71 %, and 53 %, respectively, as reported by the International Pleuropulmonary Blastoma Registry [6]. Extrapulmonary PPBs have a poor prognosis. Local recurrence and distant metastasis frequently occur after or during therapy. Patients with pleural, mediastinal, or extrapulmonary involvement at the time of diagnosis have a worse prognosis than those without such involvement (2-year survival rate, lung parenchyma only: 80.0 % ± 11.3 %, mediastinum: 37.5 % ± 17.1 %, and pleura: 47.9 % ± 14.9 %, P = 0.05) [11]. In this report, the patient was 4 months old and had PPB type III, which is exceptional for his age group. In addition, the location of the tumor is outside the lung parenchyma and involves the parietal pleura, making the prognosis of our case the worst.

4. Conclusion

Extrapulmonary pleuropulmonary blastoma is a very rare entity characterized by highly aggressive behavior and a poor prognosis. Moreover, PPB ought to be taken into consideration when a young child's huge hemithorax mass is discovered. CT imaging will clarify the nature and extent of the mass. If the mass is resectable, it is preferable to remove it as an excisional biopsy as soon as possible. If the tumor is greater than 10 cm or unresectable, it must be biopsied, followed by neoadjuvant chemotherapy and complete excision. Thus, early intervention for thoracic cystic lesions in children is warranted regardless of the symptoms to avoid future mishaps.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient's parents/legal guardian for publication and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was waived by the Faculty of Medicine at Aleppo University.

Funding

No funding or grant support.

Author contribution

Drafting the manuscript, data analysis, and interpretation: A.H.AlKhamisy.

Supervision, data collection, and surgical management: M. Morjan

Pathological assessment of tumor: L.Ghabreau

Oncology medical management and follow-up: K.Khanji

W.Abbas contributed to patient care.

A. Barakat participated in the application of chemotherapy protocols to the patient.

Guarantor

Ayman Hussein AlKhamisy, Mohamad Morjan

Research registration number

N/A.

Conflict of interest statement

No conflicts.

Contributor Information

Ayman AlKhamisy, Email: drkhamisy1981@gmail.com.

Mohamad Morjan, Email: mohamedpediatr@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Zhang N., Zeng Q., Ma X., Chen C., Yu J., Zhang X., Yan D., Xu C., Liu D., Zhang Q. Diagnosis and treatment of pleuropulmonary blastoma in children: a single-center report of 41 cases. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2020;55(7):1351–1355. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2019.06.009. Jul. Epub 2019 Jun 27. PMID: 31277979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gbande P., Abukeshek T., Bensari F., El-Kamel S. Pleuropulmonary blastoma, a rare entity in childhood. BJR Case Rep. 2021;7(4):20200206. doi: 10.1259/bjrcr.20200206. Apr 29. PMID: 35047198; PMCID: PMC8749406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zamora A.K., Zobel M.J., Ourshalimian S., Zhou S., Shillingford N.M., Kim E.S. The effect of gross total resection on patients with pleuropulmonary blastoma. J. Surg. Res. 2020;253:115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2020.03.019. Sep. Epub 2020 Apr 27. PMID: 32353636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuzucu A., Soysal O., Yakinci C., Aydin N.E. Pleuropulmonary blastoma: report of a case presenting with spontaneous pneumothorax. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2001;19(2):229–230. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(00)00634-5. Feb. (PMID: 11300091) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goel P., Panda S., Srinivas M., Kumar D., Seith A., Ahuja A., Sarkar C., Chowdhury S., Agarwala S. Pleuropulmonary blastoma with intrabronchial extension. Pediatr. Blood Cancer. 2010;54(7):1026–1028. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22440. Jul 1. (PMID: 20127851) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Messinger Y.H., Stewart D.R., Priest J.R., Williams G.M., Harris A.K., Schultz K.A., Yang J., Doros L., Rosenberg P.S., Hill D.A., Dehner L.P. Pleuropulmonary blastoma: a report on 350 central pathology-confirmed pleuropulmonary blastoma cases by the International Pleuropulmonary Blastoma Registry. Cancer. 2015;121(2):276–285. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29032. Jan 15. Epub 2014 Sep 10. PMID: 25209242; PMCID: PMC4293209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi Y.C., Tang L.F., Chen Z.M., Du L.Z. Pleuropulmonary blastoma in an infant. Indian J. Pediatr. 2009;76(9):948–949. doi: 10.1007/s12098-009-0189-8. Sep. Epub 2009 Nov 4. PMID: 19904509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knight S., Knight T., Khan A., Murphy A.J. Current management of pleuropulmonary blastoma: a surgical perspective. Children (Basel). 2019;6(8):86. doi: 10.3390/children6080086. Jul 25. PMID: 31349569; PMCID: PMC6721434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Backer N., Puligandla P.S., Su W., Anselmo M., Laberge J.M. Type 1 pleuropulmonary blastoma in a 3-year-old male with a cystic lung mass. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2006;41(11):e13–e15. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.07.015. Nov. (PMID: 17101339) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bisogno G., Sarnacki S., Stachowicz-Stencel T., Minard Colin V., Ferrari A., Godzinski J., Gauthier Villars M., Bien E., Hameury F., Helfre S., Schneider D.T., Reguerre Y., Lopez Almaraz R., Janic D., Cesen M., Kolenova A., Rascon J., Martinova K., Cosnarovici R., Pourtsidis A., Ben Ami T., Roganovic J., Koscielniak E., Schultz K.A.P., Brecht I.B., Orbach D. Pleuropulmonary blastoma in children and adolescents: the EXPeRT/PARTNER diagnostic and therapeutic recommendations. Pediatr. Blood Cancer. 2021;68 Suppl 4(Suppl 4):e29045 doi: 10.1002/pbc.29045. Jun. (Epub 2021 Apr 7. PMID: 33826235; PMCID: PMC9813943) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ali M., Malik M.A., Peters N.J., Reddy M., Samujh R. Extrapulmonary pleuropulmonary blastoma in a 3-year-old child: a case report and review of literature. J. Indian Assoc. Pediatr. Surg. 2021;26(5):342–344. doi: 10.4103/jiaps.JIAPS_159_20. Sep-Oct. Epub 2021 Sep 16. PMID: 34728923; PMCID: PMC8515531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agha R.A., Franchi T., Sohrab C., Mathew G., Kirwan A., Thomas A., et al. The SCARE 2020 guideline: updating consensus surgical case report (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2020;84(1):226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Indolfi P., Casale F., Carli M., Bisogno G., Ninfo V., Cecchetto G., Bagnulo S., Santoro N., Giuliano M., Di Tullio M.T. Pleuropulmonary blastoma: management and prognosis of 11 cases. Cancer. 2000;89(6):1396–1401. Sep 15. (PMID: 11002236) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]