Abstract

This cohort study evaluates the association of patient characteristics with the interval between hemodialysis and surgery among patients with end-stage kidney disease.

Introduction

Patients with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) experience significantly elevated perioperative risk compared with patients with normal or near normal kidney function.1 We recently observed an association between longer intervals between preoperative hemodialysis and surgery and postoperative mortality.2 Little is known, however, about whether minoritized or otherwise socially vulnerable patients with ESKD experience longer preoperative intervals between hemodialysis and surgery. We hypothesized that age, sex, race and ethnicity, and social deprivation are associated with variability in preoperative hemodialysis timing.

Methods

In this cohort study, we identified adults (aged ≥18 years) with prevalent ESKD receiving hemodialysis undergoing surgical procedures from January 1, 2011, to September 30, 2018, from the United States Renal Data System (USRDS). Details of the patient cohort, dialysis treatments, and procedures have been previously described.2 The Stanford University institutional review board provided a waiver of participant consent according to 45 CFR §46.104. This study followed STROBE reporting guidelines.3

The primary exposures were age, sex, race and ethnicity, and social deprivation index.4 Consistent with the USRDS Annual Report,5 race and ethnicity was categorized as Hispanic (any race), non-Hispanic Asian, non-Hispanic Black, and non-Hispanic White. We excluded patients who identified as American Indian or Alaska Native, Pacific Islander, Middle Eastern or Arabian, Indian (subcontinent), or other or unknown owing to small population sizes and insufficient power. The primary outcome was the proportion of procedures with a 2- or 3-day interval between the last outpatient hemodialysis session and the surgical procedure. A 2- or 3-day interval is associated with higher postoperative mortality compared with a 0- or 1-day interval.2 We identified disparities in preoperative hemodialysis timing using a logistic regression adjusted for patient and procedural covariates and with robust variance estimation to account for patient-level clustering. Model specifications and the approach to missing data are available in the eAppendix and eTable in Supplement 1. Analyses were performed using Stata version 17.1 (StataCorp). A 2-sided Bonferroni-corrected P value threshold of .006 (.05 / 8 hypotheses) was used to determine statistical significance.

Results

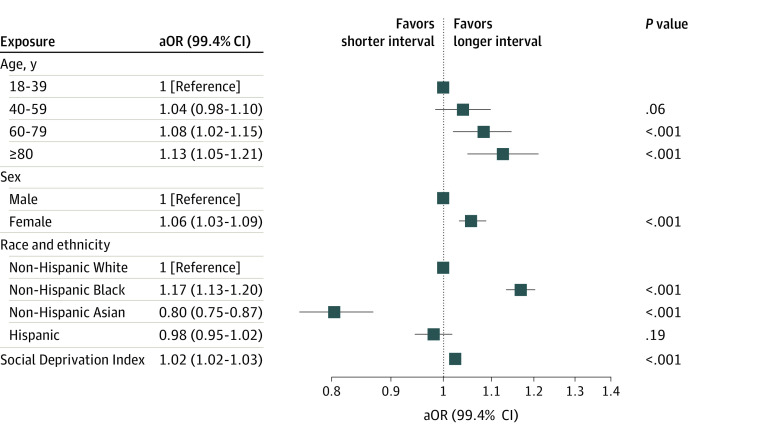

We identified 1 120 763 procedures among 338 391 patients. Of these, 81.9% of procedures had a shorter (0- or 1-day) interval between the last outpatient hemodialysis treatment and surgery and 18.1% had a longer (2 or 3-day) interval (Table). Compared with patients aged 18 to 39 years, older patients had longer hemodialysis-surgery intervals (age 60 to 79 years: adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 1.08 [99.4% CI, 1.02-1.15]; P < .001; age ≥80 years: aOR, 1.13 [99.4% CI, 1.05-1.21]; P < .001). Similarly, women (vs men: aOR, 1.06 [99.4% CI, 1.03-1.09]; P < .001), non-Hispanic Black race and ethnicity (vs non-Hispanic White: aOR, 1.17 [99.4% CI, 1.13-1.20]; P < .001), and each increasing decile of social deprivation index on a scale from 1 (lowest area deprivation) to 10 (highest area deprivation) (aOR, 1.02 [99.4% CI, 1.02-1.03]; P < .001) were all significantly associated with longer intervals between hemodialysis and surgery (Figure).4

Table. Selected Patient, Procedure, and Facility Characteristics by Interval Between Last Preoperative Hemodialysis and Procedure.

| Characteristic | Procedures, by interval between last hemodialysis and procedure, No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Short (0 or 1 d) (n = 917 635) | Long (2 or 3 d) (n = 203 128) | ||

| Patient characteristics | |||

| Age, y | |||

| Median (IQR) | 65.0 (56.0-73.0) | 64.0 (55.0-73.0) | |

| 18-39 | 35 127 (3.8) | 9117 (4.5) | |

| 40-59 | 285 059 (31.1) | 63 505 (31.3) | |

| 60-79 | 485 678 (52.9) | 106 545 (52.5) | |

| ≥80 | 111 771 (12.2) | 23 961 (11.8) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 525 174 (57.2) | 113 204 (55.7) | |

| Female | 392 461 (42.8) | 89 924 (44.3) | |

| Race and ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 177 091 (19.3) | 37 154 (18.3) | |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 30 527 (3.3) | 6530 (3.2) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 302 372 (33.0) | 75 525 (37.2) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 407 567 (44.4) | 83 900 (41.3) | |

| Missing | 78 (0.0) | 19 (0.0) | |

| Social deprivation index, median (IQR)a | 7 (5-9) | 7 (5-9) | |

| Cause of ESKD | |||

| Diabetes | 547 236 (59.6) | 114 554 (56.4) | |

| Hypertension | 222 943 (24.3) | 53 528 (26.4) | |

| Glomerulonephritis | 55 725 (6.1) | 13 401 (6.6) | |

| Cystic kidney | 14 295 (1.6) | 3520 (1.7) | |

| Other urologic | 10 417 (1.1) | 2511 (1.2) | |

| Other or unknown | 65 776 (7.2) | 15 289 (7.5) | |

| Missing | 1243 (0.1) | 325 (0.2) | |

| Vascular access type | |||

| Catheter | 273 886 (29.8) | 64 325 (31.7) | |

| Graft | <147 800 (<16.1)b | 38 463 (18.9) | |

| Fistula | 496 003 (54.1) | 97 599 (48.0) | |

| Missing | <10 (<0.0)b | <2800 (<1.3)b | |

| Rural-urban commuting area code, median (IQR)c | 1 (1-1) | 1 (1-1) | |

| Dialysis schedule | |||

| MWF | 624 504 (68.1) | 76 431 (37.6) | |

| TThS | 293 131 (31.9) | 126 697 (62.4) | |

| Listed for kidney transplant | 38 989 (4.2) | 10 379 (5.1) | |

| Years receiving hemodialysis at time of procedure, median (IQR)d | 3.3 (1.6-5.7) | 3.2 (1.5-5.7) | |

| Prior procedure within 30 d | 217 812 (23.7) | 36 497 (18.0) | |

| Medicare/Medicaid dual eligible | 419 815 (45.7) | 98 342 (48.4) | |

| Charlson comorbiditiese | |||

| Myocardial infarction | 262 705 (28.6) | 58 727 (28.9) | |

| Congestive heart failure | 505 925 (55.1) | 112 856 (55.6) | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 512 567 (55.9) | 113 750 (56.0) | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 369 252 (40.2) | 82 363 (40.5) | |

| Dementia | 64 549 (7.0) | 15 369 (7.6) | |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 392 175 (42.7) | 88 664 (43.6) | |

| Connective tissue disease–rheumatic disease | 63 627 (6.9) | 14 348 (7.1) | |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 90 774 (9.9) | 20 317 (10.0) | |

| Mild liver disease | 245 349 (26.7) | 56 136 (27.6) | |

| Diabetes without complications | 571 328 (62.3) | 125 986 (62.0) | |

| Diabetes with complications | 539 917 (58.8) | 118 152 (58.2) | |

| Paraplegia and hemiplegia | 61 346 (6.7) | 13 716 (6.8) | |

| Cancer | 138 629 (15.1) | 31 151 (15.3) | |

| Moderate or severe liver disease | 31 109 (3.4) | 7247 (3.6) | |

| Metastatic carcinoma | 24 958 (2.7) | 5727 (2.8) | |

| AIDS/HIV | 15 301 (1.7) | 3765 (1.9) | |

| Charlson comorbidity index, median (IQR) | 8 (2-10) | 8.0 (2-10) | |

| Procedure characteristics | |||

| RVU of the surgical procedure, median (IQR) | 6.3 (1.8-12.0) | 9.0 (4.2-13.3) | |

| Procedure day of the week | |||

| Monday | 49 832 (5.4) | 124 077 (61.1) | |

| Tuesday | 280 506 (30.6) | 9940 (4.9) | |

| Wednesday | 186 981 (20.4) | 25 938 (12.8) | |

| Thursday | 261 431 (28.5) | 18 666 (9.2) | |

| Friday | 138 885 (15.1) | 24 507 (12.1) | |

| Procedure organ system | |||

| Cardiovascular | 298 909 (32.6) | 88 102 (43.4) | |

| ENT and dental | 2184 (0.2) | 492 (0.2) | |

| Endocrine | 6184 (0.7) | 1605 (0.8) | |

| Eye | 351 537 (38.3) | 61 814 (30.4) | |

| Gastrointestinal and abdominal | 33 862 (3.7) | 8545 (4.2) | |

| Hematologic | 709 (0.1) | 188 (0.1) | |

| Nervous system | 7198 (0.8) | 1714 (0.8) | |

| Obstetric and gynecologic | 1444 (0.2) | 457 (0.2) | |

| Orthopedic | 38 204 (4.2) | 10 200 (5.0) | |

| Skin and breast | 159 423 (17.4) | 21 487 (10.6) | |

| Thoracic | 1199 (0.1) | 396 (0.2) | |

| Urologic | 16 782 (1.8) | 8128 (4.0) | |

| Facility characteristics | |||

| Procedure facility type | |||

| Office | 340 422 (37.1) | 53 803 (26.5) | |

| Home | 2969 (0.3) | 325 (0.2) | |

| Inpatient hospital | 69 943 (7.6) | 29 990 (14.8) | |

| Outpatient hospital | 387 167 (42.2) | 95 769 (47.1) | |

| Ambulatory surgery center | 87 975 (9.6) | 19 567 (9.6) | |

| Skilled nursing facility | 22 030 (2.4) | 2675 (1.3) | |

| Other | 7129 (0.8) | 999 (0.5) | |

| For-profit facilityf | 801 759 (87.4) | 177 676 (87.5) | |

Abbreviations: ENT, ear, nose, and throat; ESKD, end-stage kidney disease; MWF, Monday-Wednesday-Friday; RVU, relative value unit; TThSat, Tuesday-Thursday-Saturday.

Social deprivation index was quantified using deciles (integers from 1 to 10), with increasing values representing higher area level deprivation based on seven demographic characteristics collected in the American Community Survey.4 Data were available for 905 398 procedures with a short interval and 199 861 with a long interval.

Exact cell count modified to preserve patient privacy.

Data available for 915 824 procedures with a short interval and 202 708 with a long interval.

Data available for less than 940 200 procedures with a short interval and less than 203 140 with a long interval. Exact counts were modified to preserve patient privacy.

Charlson comorbidities were determined using published coding algorithms.6 Kidney disease was not included, as the study cohort only consisted of patients with ESKD. For calculation of the Charlson Comorbidity Index, all patients were considered to have kidney disease.

Data were available for 909 611 procedures with a short interval and 201 007 with a long interval.

Figure. Association of Age, Sex, Race and Ethnicity, and Social Deprivation With the Interval Between Preoperative Hemodialysis and Surgical Procedure.

Adjusted model estimates reflect Bonferroni-corrected thresholds for statistical significance. Thus, 99.4% CIs are displayed, and P < .006 was used to determine statistical significance. Social deprivation index was quantified using deciles (integers from 1 to 10), with increasing values representing higher area level deprivation based on 7 demographic characteristics collected in the American Community Survey.4 aOR indicates adjusted odds ratio.

Discussion

This study found significant age-, sex-, race and ethnicity–, and social deprivation–related disparities in the timing of preoperative hemodialysis among patients with ESKD. Given that a longer interval between preoperative hemodialysis and surgical procedures is associated with higher postoperative mortality, these findings are concerning and identify a possible avenue to improve equity in surgical outcomes for patients with ESKD. Study limitations include residual confounding and limited generalizability to persons who identify as American Indian or Alaska Native, Pacific Islander, Middle Eastern or Arabian or Indian (subcontinent), or those without fee-for-service Medicare. Our study highlights the need for equitable access to perioperative care coordination for persons with ESKD.

eAppendix. Supplemental Methods

eTable. Missing Data for Exposures and Selected Covariates

eReferences.

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Harrison TG, Hemmelgarn BR, James MT, et al. Association of kidney function with major postoperative events after non-cardiac ambulatory surgeries: a population-based cohort study. Ann Surg. 2023;277(2):e280-e286. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fielding-Singh V, Vanneman MW, Grogan T, et al. Association between preoperative hemodialysis timing and postoperative mortality in patients with end-stage kidney disease. JAMA. 2022;328(18):1837-1848. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.19626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative . The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453-1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robert Graham Center . Social deprivation index (SDI). November 5, 2018. Accessed February 28, 2023. https://www.graham-center.org/rgc/maps-data-tools/sdi/social-deprivation-index.html

- 5.United States Renal Data System . 2022 Annual data report. Accessed March 20, 2023. https://adr.usrds.org/2022

- 6.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130-1139. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Supplemental Methods

eTable. Missing Data for Exposures and Selected Covariates

eReferences.

Data Sharing Statement