Abstract

Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) is a recently described arterivirus responsible for disease in swine worldwide. Comparative sequence analysis of 3′-terminal structural genes of the single-stranded RNA viral genome revealed the presence of two genotypic classes of PRRSV, represented by the prototype North American and European strains, VR-2332 and Lelystad virus (LV), respectively. To better understand the evolution and pathogenicity of PRRSV, we obtained the 12,066-base 5′-terminal nucleotide sequence of VR-2332, encoding the viral replication activities, and compared it to those of LV and other arteriviruses. VR-2332 and LV differ markedly in the 5′ leader and sections of the open reading frame (ORF) 1a region. The ORF 1b sequence was nearly colinear but varied in similarity of proteins encoded in identified regions. Furthermore, molecular and biochemical analysis of subgenomic mRNA (sgmRNA) processing revealed extensive variation in the number of sgmRNAs which may be generated during infection and in the lengths of noncoding sequence between leader-body junctions and the translation-initiating codon AUG. In addition, VR-2332 and LV select different leader-body junction sites from a pool of similar candidate sites to produce sgmRNA 7, encoding the viral nucleocapsid protein. The presence of substantial variations across the entire genome and in sgmRNA processing indicates that PRRSV has evolved independently on separate continents. The near-simultaneous global emergence of a new swine disease caused by divergently evolved viruses suggests that changes in swine husbandry and management may have contributed to the emergence of PRRS.

Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) is a small, enveloped positive single-stranded RNA virus that causes reproductive failure in breeding swine and respiratory problems in young pigs. The syndrome was first recognized as a “mystery swine disease” in the United States in 1987 (27), but in the time since the virus was identified in Europe (Lelystad virus [LV] [67]) and in the United States (VR-2332 [4, 10]), PRRSV has become a significant pathogen of swine herds worldwide, with new disease phenotypes continuing to emerge (49).

PRRSV is a member of the family Arteriviridae in the order Nidovirales (7). The arterivirus family consists of PRRSV, lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus (LDV), equine arteritis virus (EAV), and simian hemorrhagic fever virus (SHFV) (46). The 5′-capped (51) and 3′-polyadenylated (5, 50, 61) RNA is polycistronic, containing (5′ to 3′) two large replicase open reading frames (ORFs), 1a and 1b, and several smaller ORFs (11, 28, 42, 55). In the infected cell, arteriviruses produce a nested set of six to eight major coterminal subgenomic mRNAs (sgmRNAs) each thought to express only the relative 5′-terminal ORF. These sgmRNAs have a leader sequence derived from the 5′ end of the genome that is joined at specific leader-body junction sites located downstream by an unclear discontinuous transcription mechanism (29). The sgmRNAs of PRRSV encode four glycoproteins (GP2 to 5, encoded by sgmRNAs 2 to 5), an unglycosylated membrane protein (M, encoded by sgmRNA 6), and a nucleocapsid protein (N, encoded by sgmRNA 7) (3, 32, 33, 38, 41, 43). The European prototype strain of PRRSV, LV, contains all six of these proteins in the virion (35, 36, 65), but only the proteins encoded by ORFs 5 to 7 have conclusively been demonstrated to be in the virion of North American isolates (3, 43, 45).

Nucleotide and amino acid sequence comparisons of the 3′-terminal ORFs 2 to 7 have shown that there are significant differences between PRRSV strains native to Europe and those found in North America (26, 42). Therefore, although these two PRRSV strains cause similar diseases (4, 67), they are genotypically different in the genes encoding structural proteins. In order to fully investigate the genomic properties of these two divergent groups of PRRSV strains, we completed the sequencing of the 5′ 12,066 nucleotides of North American prototype VR-2332 that contain ORF1 and compared the generated nucleotide and predicted amino acid sequences to those of the European PRRSV prototype strain LV (15,111 bases [38, 39]), LDV strain P (LDVP) (14,104 bases [44]), and EAV strain Bucyrus (12,719 bases [63]).

The genotypic comparison between strains VR-2332 and LV revealed that ORF 1a of VR-2332 is vastly different from that of LV in both length and sequence, while ORF 1b is relatively conserved between the two strains of PRRSV. The 5′ leader sequence of VR-2332 was 31 bases shorter than that of LV and differed considerably in nucleotide sequence. Regional amino acid sequence comparisons also revealed that although the recognized functional domains of the ORF 1a proteins were present in both strains, the proteins were not well conserved between these domains. In order to investigate biochemical differences caused by the total genome variation, we determined the use of subgenomic leader-body junction sites for VR-2332 mRNAs and found that VR-2332 can utilize various sites, all of which are different from those used by LV (37). In particular, examination of the display of sgmRNA 7 transcripts revealed that three potential leader-body junction sites are present at the same relative sites on the genomes of North American VR-2332 and European LV strains, yet the junction site utilized to form sgmRNA 7 was peculiar to each isolate. Therefore, these two strains, which cause comparable diseases in the same host, differ greatly in both genotype and selection of a subgenomic transcript leader-body junction site. The results, combined with those of earlier studies (26, 42), suggest that these two PRRSV strains underwent divergent evolution on two continents from a distant common ancestor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Virus and cells.

The fourth cell culture passage of the VR-2332 isolate of PRRSV was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and was passaged twice before the isolate was used to generate nearly full-length VR-2332 mRNA 7 cDNA. The LV isolate was provided by Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health, St. Joseph, Mo. David Benfield (South Dakota State University, Brookings) provided plaque-purified VR-2332. All PRRSV samples were propagated in simian MA-104 cells in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum at 37°C (10). Porcine alveolar macrophages were prepared as described previously (2). PRRSV isolates were grown in macrophages in standard RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 2% swine serum.

Viral cDNA identification, RNA isolation, RT-PCR, and cloning.

The construction and screening of a VR-2332-infected cell library was described previously (42). A 270-bp fragment, generated by restriction endonuclease digestion of a plasmid containing cDNA of bases 20 to 222 of the LV strain of PRRSV and a flanking vector sequence, was radiolabeled with [32P]dCTP (3,000 Ci/mmol; Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.) by random oligonucleotide-primed synthesis (17) and used as a probe for the detection of similar sequences in VR-2332. VR-2332 library clones 412 and 658 were identified in this manner.

Viral genomic RNA was isolated from infected MA-104 cell medium. The medium was collected 4 days postinfection (p.i.), and cellular debris was removed by centrifugation for 20 min in a JA-14 rotor (Beckman Instruments, Inc., Fullerton, Calif.) at 8,000 rpm at 4°C. The virus was pelleted from the supernatant, and the RNA was purified from this pellet essentially as described previously (9). Viral RNA was denatured by treatment with 10 mM methylmercuric hydroxide, primed with VR-2332-specific primers, and reverse transcribed with SUPERSCRIPT II RNase H− reverse transcriptase (RT) (Life Technologies, Inc.). PCRs were completed with VR-2332, LV, LDVP primers, or degenerate primers designed from regions of high homology between LV and LDVP sequences (Table 1). PCR amplification was completed with the Long PCR kit (Boehringer Mannheim Corporation) with an optimization of annealing temperature for individual primer pairs and an elongation time for predicted product size. PCR products were purified with a Microcon 100 kit (Amicon).

TABLE 1.

Primers used to generate ORF 1 clones of VR-2332

| Primer | Sequence | Location |

|---|---|---|

| 658P1/ | 5′-CAGGAGCTGTGACCATTGGC | 45–64 |

| /658P4 | 5′-GAAGGGTGTTTCTGTGCAGC | 60–79 |

| 5′5500/ | 5′-CAAGACCCAATTCTGCACG | 5848–5863 |

| 5′6050/ | 5′-GCGCCCCTCAGGCCAGTTTT | 6049–6068 |

| /3′5800 | 5′-TGGCTGCCGACCTTCAC | 6124–6140 |

| 5′5800/ | 5′-GGCAGCCACATAATTAAAGACATA | 6149–6172 |

| /3′6200 | 5′-ACTGCACCGAGGCTTGAA | 6458–6475 |

| LAF2/ | 5′-GCTTTGTATCTGCTTCAAACATG | 6544–6566 |

| 5′7550/ | 5′-GGTCCCCGTCAACCCAGAGAAT | 7522–7543 |

| /3′ORF1b | 5′-ACCGTCGACATTCATCATACCTA | 7568–7590 |

| /3′8242 | 5′-CGGATAATGGGACAGGTTC | 7633–7652 |

| /3′42-60 | 5′-AATCCTTTCACCCGCATCA | 8123–8141 |

| 5′40-56/ | 5′-CCTGATGCGGGTGAAAG | 8139–8156 |

| 5′8342/ | 5′-AGGAGMAYTGGCAAACYGTGAC | 8352–8375 |

| 5′8242/ | 5′-CCCGCYAAGACCTCKATGG | 8539–8560 |

| VRBP1/ | 5′-GTTTGGTGATCTATGCACAG | 9080–9099 |

| 5′-160/ | 5′-TCCCACCATGCCAAACTATCACTG | 9237–9260 |

| /VRBP2 | 5′-CAGATGTTCAACCCACCAGT | 9257–9277 |

| VRBP5/ | 5′-CTCATGGACAGCTGTGCTTG | 9463–9482 |

| /3′965 | 5′-GTGGGCCGATGATGAACCTG | 10028–10047 |

| VRBP9/ | 5′-GAATGCACGGTTGCTCAGGC | 10840–10859 |

| 5′1500/ | 5′-GAGGACGACGCCATCACTAT | 10588–10787 |

| /VRBP6 | 5′-CCCAGGAGTGCCTAGAAAC | 11163–11181 |

| /3′2260 | 5′-GGTGACATCCTCCAACGGTAGTGC | 11325–11348 |

| /VRBP4 | 5′-GTTCAATGACAGGGCCCGG | 12031–12049 |

| /P23 | 5′-GCCACCACATCCAAACTAC | 12489–12507 |

To obtain leader-body junction sites, total RNA from infected-cell lysates was isolated by acid guanidine phenol extraction or by the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Santa Clarita, Calif.) on day 3 (MA-104) or day 2 p.i. (alveolar macrophages). Reverse transcription was performed with random hexamers and Moloney murine leukemia virus RT (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, Conn.). For the first round of PCRs, a leader sequence forward primer (658P1/, 5′-CAGGAGCTGTGACCATTGGC) was synthesized based on the sequence of clones 658 and 412 and was used with reverse primers specific to each of the ORFs (712P5, 5′-CGGCTTCAATGGCGGCTAG [ORF 2]; 712P2, 5′-GGCGCACATGAGTTGATG [ORF 3]; P42, 5′-GCAATCGCGAGCAACAGCC [ORF 4]; 05P1, 5′-GGTTGCCACGGAACCATC [ORF 5]; 06P1, 5′-GCGGCACTTTCAACGTGG [ORF 6]; and P72, 5′-CGCCCTAATTGAATAGGTGAC [ORF 7]). First-round PCR products were diluted 200-fold and used in nested PCRs with, as the leader sequence forward primer, 658P2 (5′-GCTGCACAGAAACACCCTTC) and reverse primers specific to the internal sequence of each ORF PCR product generated (712P6, 5′-GGCCTCATAAGATCTTCTG [ORF2]; 712P3, 5′-CTAGCTCGTCATGATCGTC [ORF3]; 416P1, 5′-CATGTTGGACGTAGCTGG [ORF4]; O5P2, 5′-GAAGCAAGTCAACGCAGCC [ORF5]; 06P2, 5′-GGTGAAAGCACAATTCAGG [ORF6]; and P73, 5′-CTTTCCCGGTCCCTTGCC [ORF7]). Alternatively, nested PCRs were completed with 658P1/ as the forward primer and a primer developed for 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (Qt, 5′-CCA GTGAGCAGAGTGACGAGGACTCGAGCTCAAGCTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT TT) in the first round, and in the second round, 658P2 and another primer developed for 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (Qo, 5′-CCAGTGAGCAGAGTGACG) were used (19). PCR was performed for a total of 30 cycles. These nucleic acids were denatured for 1 min at 93°C, annealed at 55 to 63°C for 30 s to 1 min, and extended at 72°C for 1 min. The amplified fragments were then polished at 72°C for 10 min. Fragments corresponding to the approximate predicted size were gel purified with GeneClean II (Bio 101, Vista, Calif.) or a Qiaquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen).

Purified fragments were ligated into the pGEM-T vector (Promega, Madison, Wis.) and transformed into competent DH5α cells. For each leader-body junction, at least two clones from independent PCRs were sequenced with the exception of mRNA 7, for which a total of 10 clones were analyzed (16).

Primer extension.

RNA was obtained from total RNA from infected MA-104 cells on day 3 p.i. with Trizol reagent (Gibco BRL). Primer extension analysis to determine the length of the 5′ leader was completed as described previously but with modifications (60). Briefly, 1 μg of infected-cell total RNA was denatured in the presence of 10 mM methylmercuric hydroxide for 5 min and hybridized for 16 h at 30°C to the leader sequence reverse complement primer /658P4 (Table 1), which was isotopically 5′-end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP (Amersham Life Science) and T4 polynucleotide kinase (Promega Corporation). The labeled primer was extended with Superscript II RNase H− RT (Gibco BRL). The fragment was sized with a sequencing reaction on clone 712 (42), with a 19-mer primer, P71/ (5′-GCTGTTAAACAGGGAGTGG), by electrophoresis through a 7 M urea–polyacrylamide gel (9%).

Northern blotting.

One microgram of total RNA was denatured with glyoxyl, electrophoresed through a 2% agarose gel (6), transferred to nylon membranes (MagnaGraph; MSI, Westboro, Mass.), and cross-linked to the membrane by UV light. Membranes were hybridized to radiolabeled oligomers in QuikHyb (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) at 68°C for 16 h, washed three times in 6× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M sodium chloride plus 0.015 M sodium citrate [pH 7.0])–0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate at 72°C, and exposed to autoradiography film (NEN Life Science Products, Boston, Mass.) or a phosphorimaging screen (Molecular Dynamics, Inc., Sunnyvale, Calif.). The reverse complement oligomer sequences were derived from defined nucleotide regions of potential sgmRNA 7 species (ORF7-VR, 5′-CCTTCTTTCTCTTCTGCTGCTTGCCGTTGTTATTTGGC AT, melting temperature (Tm) = 79.5°C; ORF7-LV, 5′-TACTTTTCTTTTTCTTCTGGCTCTGGTTTTTACCGGCCAT, Tm = 76.4°C; ORF7-JS 1,5′-ACGCCGGACGACAAATGCGTGGTTAAAGGGGTGGAGAGAC, Tm = 85.4°C; ORF7-JS 2, 5′-TTATTTGGCATATTTGACAAGGTTTACGGGGTGGAGAGAC, Tm = 76.7°C; and ORF7-JS 3, 5′-GACAAGGTTTACCACTCCCTGTTTAACGGGGTGGAGAGAC, Tm = 78.9°C). The oligomers were 3′-end radiolabeled with [α-32P]dATP (Amersham Life Science) and terminal deoxynucleotide transferase (Promega Corporation).

Sequence analysis.

Automated sequencing reactions were completed with a Taq DyeDeoxy terminator cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems) and a PE 2400 Thermocycler (Perkin-Elmer) at the University of Minnesota Advanced Genetic Analysis Center. Analysis of the newly generated VR-2332 sequence and comparison to the sequences of other arteriviruses were completed with computer software included in the LASERGENE package (DNASTAR Inc., Madison, Wis.), Wisconsin package version 9.1 (Genetics Computer Group [GCG], Madison, Wis.), and EUGENE (Molecular Biology Information Resource, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Tex.). Sequences used for sequence analysis (and their GenBank accession numbers) include VR-2332 leader sequence (AF030244), ORF 2 to the 3′ end (PRU00153), LV (M96262), LDVP (PRU15146), and EAV (X53459).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The complete genomic sequence for strain VR-2332 detailed in this report has been deposited as GenBank accession no. PRU87392.

RESULTS

Determination of the 5′-end sequence of VR-2332 viral RNA.

Library clones 412 and 658 included putative 5′ leader sequences of 162 and 170 bases, respectively, based on sequence comparison to other arteriviruses. These separate clones exhibited complete nucleotide identity for all 162 5′ leader nucleotides of clone 412. Eight additional nucleotides were present at the 5′ end of clone 658. To establish the sequence as the VR-2332 5′ leader sequence, a SmaI restriction endonuclease digestion of clone 412 was used to probe, at high stringency, a Northern blot of total RNA from MA-104 cells infected with PRRSV. Hybridization of the radiolabeled probe to discrete bands of RNA derived from VR-2332-infected cells but not to RNA derived from LV-infected cells was observed. A primer synthesized by using the additional eight nucleotides present in the 170-base (clone 658) sequence has identified the VR-2332 leader sequence joined to downstream ORF 1 nucleotides (d5800 clones; Fig. 2A) with no alterations in the leader sequence presented below.

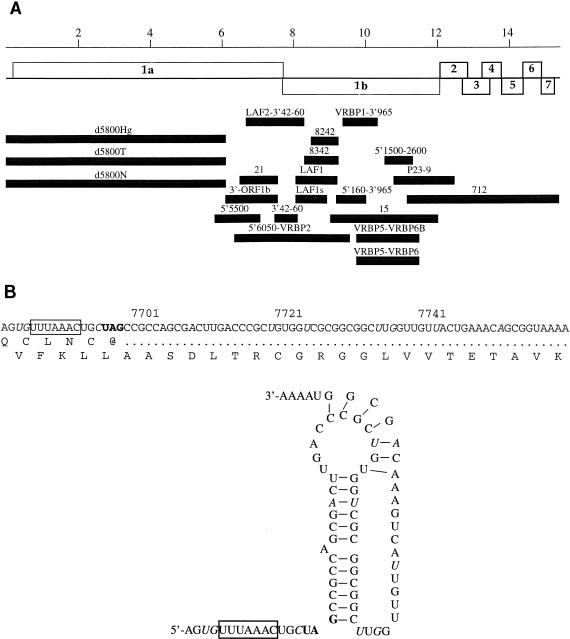

FIG. 2.

(A) Schematic of the 15,409-base viral genome of VR-2332 (open boxes) with sequenced cDNA clones (shaded boxes). (B) Sequence of the VR-2332 region between ORF 1a and 1b and its resulting predicted RNA pseudoknot tertiary structure involved in ribosome frameshifting, as modeled on the predicted pseudoknot of LV (1, 38). The proposed heptanucleotide slippery sequence (boxed), UAG stop codon of ORF 1a (bold), and differences between VR-2332 and LV (italics) are indicated.

In order to locate the exact 5′ end of strain VR-2332, primer extension reaction products were analyzed. The strong stop for VR-2332 primer extension comigrated with a thymidine residue at nucleotide 2965 in clone 712 (98 bases from the start of P71), corresponding to a primer extension product of 98 nucleotides (Fig. 1A). Because the primer extension reaction was completed with a primer annealing to bases 78 to 59 of the leader sequence of ORF 7 clone 658, the 20-base difference represents an uncloned genomic sequence. Therefore, the 5′ end of the leader sequence of PRRSV VR-2332 is 190 bases in length (170 plus 20 nucleotides). The 20 5′-terminal nucleotides have not yet been identified.

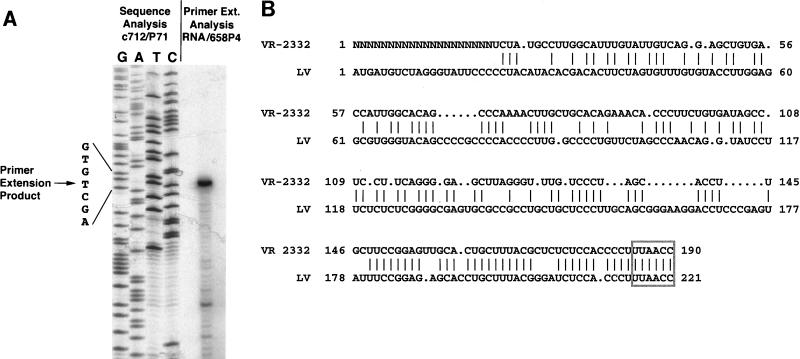

FIG. 1.

(A) Primer extension analysis of strain VR-2332. RNA from VR-2332-infected MA-104 cells was hybridized to γ-32P-radiolabeled VR-2332 leader reverse primer /658P4 and reverse transcribed. The primer extension products were electrophoresed alongside the known sequencing products obtained from clone 712 and forward primer P71/. The primer extension product migrated with the thymidine residue located at nucleotide 2965 of clone 712, resulting in an extension product of 98 nucleotides. (B) Comparison of PRRSV leader sequences. VR-2332 leader (190 bases in length) and LV leader (221 bases in length) sequences exhibit 61.0% identity as analyzed by the GCG GAP program, with a gap weight of 5 and a length weight of 5 (lines between the sequences indicate identity). The leader-body junction sequence utilized for transcription of each mRNA is boxed.

Comparison of VR-2332 with other arterivirus leader sequences.

The VR-2332 leader sequence is intermediate in length among the leader sequences of LDVP (156 bases [8]), LDVC (161 bases [20]), SHFV (208 bases [68]), EAV (211 bases [12, 63]), and LV (221 bases [38, 39]). The 190-base leader sequence was aligned with the 221-base leader sequence of LV (Fig. 1B). The two PRRSV isolates exhibited an overall moderate sequence identity of 61.0% for the known leader sequences when aligned with the GAP program in GCG. The leader sequences of two isolates of LDV exhibited similar sequence identities to VR-2332 (62.5% for LDVP and 62.3% for LDVC) when they were compared by using the same parameters. The only region of distinct similarity was in the approximately 40-base region at the 3′ end of the leader sequences, which exhibited 90.4% identity. The hexanucleotide UUAACC (Fig. 1B) was shown to be completely conserved between the two strains and defines the leader-body junction sequence for strain VR-2332 (see below).

Determination of the genomic sequence for ORF 1 of strain VR-2332.

The genomic sequence for VR-2332 ORF 1 was generated from RT-PCR products covering the region at least three times, as schematically outlined in Fig. 2A, by using the primers listed in Table 1. The sequence of clone 712 (ORFs 2 to 7) was reported previously (42). Using LV-specific primers, we obtained RT-PCR cDNA clones LAF1, LAF1s, LAF2-3′40-60, 21, 3′-ORF1b, and 3′42-60. LV-LDVP primers produced clones 8242 and 8342 by similar RT-PCR methods. The remaining clones were generated by RT-PCR with VR-2332-specific primers disclosed through sequence analysis of the previously mentioned clones. All clones were sequenced and aligned into 12,066 contiguous bases.

When the newly generated sequence was combined with the sequence of clone 712, the complete VR-2332 viral genome consisted of 15,409 bases with a polyadenylated tract at the 3′ end (Fig. 2A). The genome of LV is 15,098 nucleotides in length (39), and thus, the VR-2332 genome is 311 nucleotides longer than the genome of the European strain LV. The predicted lengths (and calculated molecular masses) of the products of strain VR-2332 ORF 1a and 1b are 2,502 amino acids (272.1 kDa) and 1,457 amino acids (161.0 kDa), respectively, while strain LV possesses ORF 1 proteins of 2,396 amino acids (260.1 kDa) and 1,458 amino acids (161.3 kDa), respectively (Fig. 3A).

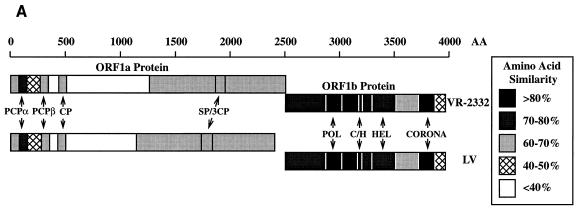

FIG. 3.

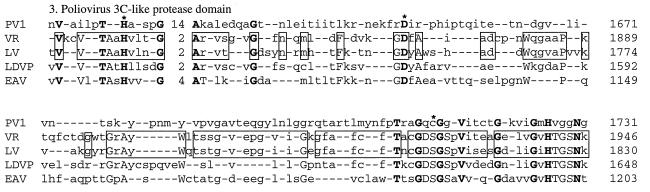

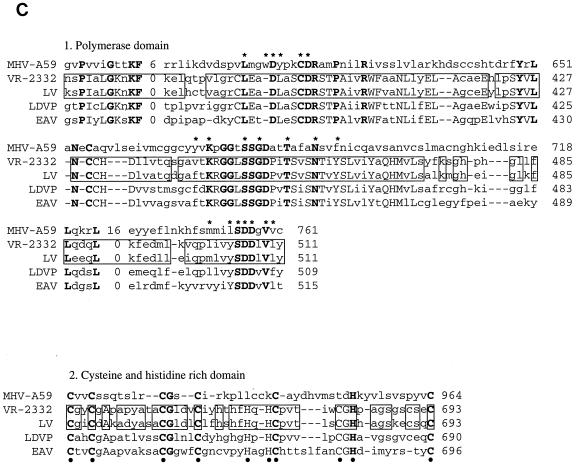

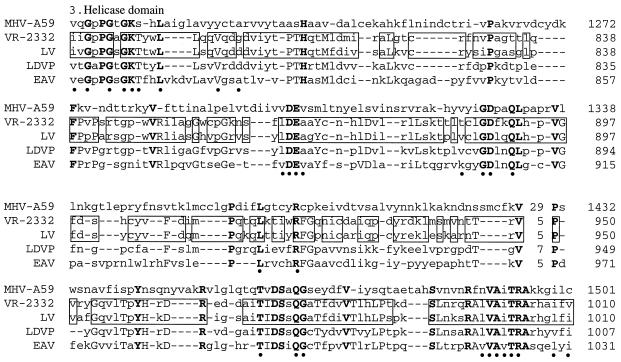

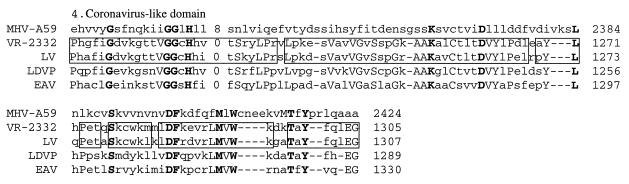

(A) Schematic of amino acid comparisons of VR-2332 (upper bars) and LV (lower bars) by domain, showing regions of similarity and dissimilarity (GCG GAP program alignments; see text). (B) ORF 1a alignment of the following: (1) arteriviral PCPα and -β domains and their respective catalytic residues (α or β) (with blosum62.cmp and pam250.cmp, a gap weight of 12, and a gap length weight of 4); (2) an unusual arteriviral cysteine protease domain with putative catalytic residues (•) (with blosum62.cmp, a gap weight of 5, and a gap length weight of 5); and (3) the poliovirus 3C-like protease (PV1) domain with catalytic H and D and C/S residues (∗) (with blosum62.cmp, a gap weight of 1, and a gap length weight of 2). (C) ORF 1b with MHV-A59 ORF 1b residues used to align the following: (1) a putative polymerase region with amino acids conserved among positive strand RNA viruses (48) shown (∗) (with blosum62.cmp, a gap weight of 5, and a gap length weight of 5); (2) a domain with conserved cysteine and histidine residues (•) (with blosum62.cmp, a gap weight of 6, and a gap length weight of 2); (3) helicase domains showing conserved amino acids (•) in Sindbis virus-like RNA plant virus group A2 (22) (with blosum62.cmp, a gap weight of 2, and a length weight of 2); and (4) a coronaviruslike domain (with blosum62.cmp, a gap weight of 5, and a gap length weight of 5). In all panels, amino acids conserved in aligned sequences are shown in boldface, those conserved among arteriviruses are shown in uppercase (except for the PCPα and -β -alignment which shows conservation between VR-2332, LV, and LDVP in uppercase), and similar amino acids between the two PRRSV strains are boxed.

Genetic comparison of PRRSV VR-2332 ORF 1 sequence to those of other arteriviruses.

Needleman-Wunsch pairwise comparisons between VR-2332 ORF 1 and other arterivirus ORF 1 nucleotide and protein sequences showed that ORF 1b is relatively more conserved than ORF 1a among arteriviruses (Table 2). The low degree of nucleotide and protein similarity to the European prototype strain of PRRSV, LV, obtained for both ORF 1a and 1b was particularly striking and was not expected for two viruses causing the same disease phenotype in the same host.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of VR-2332 ORF 1 sequences to those of other arterivirusesa

| ORF | LV

|

LDVP

|

EAV

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % nt identity | % aa similarity | % nt identity | % aa similarity | % nt identity | % aa similarity | |

| 1a | 54.7 | 55.6 | 51.6 | 46.7 | 41.0 | 28.3 |

| 1b | 63.1 | 75.3 | 55.4 | 62.2 | 47.8 | 46.6 |

Needleman-Wunsch alignment was carried out with the GCG GAP program: nwsgapdna.cmp (for nucleotide comparison) with a gap weight of 50, and a gap length weight of 3 and blosum62.cmp (for amino acid comparison) with a gap weight of 12 and a gap length weight of 4. nt, nucleotide; aa, amino acid.

The ORF 1 sequence of VR-2332 contained a predicted pseudoknot sequence at the end of ORF 1a (Fig. 2B), very similar to the pseudoknot sequence of strain LV (1, 38), so that the 1,457 additional amino acids of ORF 1b were predicted to be translated through ribosomal frameshifting (Fig. 3A) (12). Regions corresponding to seven protein domains have been identified in ORF 1 of all members of the order Nidovirales (12, 13, 56–58). These protein domains were identified for strain VR-2332 by genetic comparison and were aligned with and compared to PRRSV LV (Fig. 3A) and other viruses (Fig. 3B and C).

The VR-2332 ORF 1a sequence, like that of LV, contained two papainlike cysteine protease (PCP) motifs (PCPα was 78.0% similar [amino acids 74 to 146] and PCPβ was 62.5% similar [amino acids 268 to 339]), an unusual cysteine protease with a putative CG catalytic site (63.9% similar [amino acids 435 to 506]), and a poliovirus 3C-like serine protease motif (68.6% similar [amino acids 1840 to 1946]) that were moderately conserved between the strains (Fig. 3A). All four predicted proteases and their cleavage sites have yet to be defined. However, both PCP sites are functional in LV (13), and the relative conservation of these two motifs suggests that both sites are likely to be functional in VR-2332. All serine protease sites predicted for LV (62) were shown to be conserved in the ORF 1b sequence of VR-2332. A region of little protein similarity (39.3%), VR-2332 amino acids 507 to 1236 and LV amino acids 498 to 1119 (optimal similarity score obtained with the GCG GAP program, a blosum62.cmp scoring matrix, a gap weight of 2, and a gap length weight of 4), in the ORF 1a product resided between the third cysteine protease domain and the serine protease domain and accounted for the majority of the extra 106 amino acids in strain VR-2332 (Fig. 3A and data not shown). An exhaustive search of many databases revealed no other predicted protein motifs present in the ORF 1 product of strain VR-2332.

ORF 1b was more conserved than ORF 1a. ORF 1b of VR-2332 was highly similar to that of LV, in that it coded for polymerase (86.9% similar [amino acids 367 to 511]) and nidovirus-unique coronaviruslike (89.7% similar [amino acids 1209 to 1305]) domains. In addition, nucleoside triphosphate/helicase (77.2% similar [amino acids 787 to 1010]) and cysteine- and histidine-rich (76.6% similar, probably metal binding [amino acids 647 to 693]) domains that were less similar to LV were also identified. A region of 151 amino acids at the C terminus of the ORF 1b product exhibited only 49.0% similarity between the two PRRSV strains (Fig. 3A).

Comparison of putative functional domains of VR-2332 ORF 1 to other viruses.

As shown in Fig. 3B, panel 1, VR-2332 ORF 1a PCP motifs were aligned with those of LV, LDVP, and EAV (13, 57, 58, 66). PCPα is well conserved between both strains of PRRSV and LDVP. However, the putative catalytic residues of PCPβ, when aligned, suggest that there is considerable divergence between the viruses, including those between VR-2332 and LV, as the lengths of regions between conserved residues are quite variable. The poliovirus 3C-like serine protease motif also contains different lengths of nonconserved amino acids between conserved residues (Fig. 3B, panel 3).

In other ORF 1 functional domains, strains VR-2332 and LV are clearly more related to each other than to other arteriviruses, although there are many short amino acid stretches which also have identity to LDVP (Fig. 3). EAV possesses little homology to other arteriviruses (59).

VR-2332 leader-body junction sequences.

Previous results suggested that each sgmRNA leader-body junction included one specific junction site on the PRRSV genome (34, 37, 52). However, sequence analysis of the 3′ end of VR-2332 identified 15 potential leader-body junction sequences which could theoretically be used for transcription of the six sgmRNAs 2 to 7 (consensus sequence with one mismatch, see below). Therefore, leader-body junction sequence analysis was completed by RT-PCR for each ORF-specific sgmRNA transcript. The leader-body junction consensus sequence for VR-2332 was determined to be UUAACC, similar to all arterivirus consensus sequences described to date (8, 14, 15, 21, 34, 37, 52), with nucleotide differences among the sgmRNAs noted for the first five bases of this sequence ([U/A][U/C/A/G][A/C][A/G][C/U]C) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of the numbers of nucleotides between the leader-body junction site and the initiating AUG for sgmRNAs of VR-2332 (North American) and LV (European [37]) PRRSV

| ORF | mRNA | VR-2332 junction

|

No. of nucleotides

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Sequencea | VR-2332 (no. of clones) | LVb | ||

| 2 | 2 | Leader | CACCCCUUuAACCAugUcUg | ||

| Subgenomic | CACCCCUUGAACCAACUUUA | 19 (5) | 38 | ||

| Genomic | CuguCaUUGAACCAACUUUA | ||||

| 3 | 3 | Leader | CACCCCUUUAACCAUgucug | ||

| Subgenomic | CACCCCUUUAACCAUAGUGU | 83 (4) | 11 | ||

| Genomic | guCaaaUgUAACCAUAGUGU | ||||

| 4 | 4.1 | Leader | CACCCCUUUaACCauGucUG | ||

| Subgenomic | CACCCCUUUCACCUAGAAUG | 4 (3) | 83 | ||

| Genomic | aAuuggUUUCACCUAGAAUG | ||||

| 4.2 | Leader | CACCCCUUuAaCCaUGUcUg | |||

| Subgenomic | CACCCCUUCAGCCGUGUUUC | 56 (1) | NDc | ||

| Genomic | CAaCauUUCAGCCGUGUUUC | ||||

| 5 | 5 | Leader | CACCCCUUUAaCCaugucUg | ||

| Subgenomic | CACCCCUUUAGCCUGUCUUU | 40 (3) | 32 | ||

| Genomic | aACuguUUUAGCCUGUCUUU | ||||

| 5-1 | Leader | CACCCCUUUAacCAugucug | |||

| Subgenomic | CACCCCUUUAGUCACUGUGU | 111 (1) | ND | ||

| Genomic | aguCuCUUUAGUCACUGUGU | ||||

| 6 | 6 | Leader | CACCCCUuUAACCAugucUg | ||

| Subgenomic | CACCCCUAUAACCAGAGUUU | 17 (4) | 24 | ||

| Genomic | aACCCCUAUAACCAGAGUUU | ||||

| 7 | 7.1 | Leader | CACCCCUUUAACCAuGucUg | ||

| Subgenomic | CACCCCUUUAACCACGCAUU | 123 (7) | 9 | ||

| Genomic | gcaaaugaUAACCACGCAUU | ||||

| 7.2 | Leader | CACCCCuUuAACCaUGUCug | |||

| Subgenomic | CACCCCGUAAACCUUGUCAA | 9 (3) | ND | ||

| Genomic | ggagugGUAAACCUUGUCAA | ||||

The leader-body junction motif for each sgmRNA is underlined. Nucleotides conserved between the subgenomic, leader, and genomic sequences are in uppercase.

Material reprinted with the permission of the Society of General Microbiology and J. J. M. Meulenberg (37).

ND, not detected.

The length of untranslated sequence between the leader-body junction sequence and the starting AUG for each ORF is shown in Table 3. For mRNAs 2, 3, and 6 only one junction site was identified. However, for mRNAs 4 and 7, two genomic sites were identified and designated 4.1 and 4.2 and 7.1 and 7.2, respectively, designations similar to the nomenclature of additional EAV mRNA 3 species (14). Another mRNA (5-1 [7]) utilized a site downstream of the starting AUG for ORF 5, and it appears to encode a truncated protein utilizing the second ORF 5 methionine (amino acid 132; data not shown). The length of untranslated sequence preceding ORFs 3 and 4.1 for VR-2332 agrees with that of another North American isolate (ISU79 [34, 40]). However, mRNA 3-1, detected in ISU79-infected cells, was not detected in our analysis of VR-2332-infected cells. This could be due to the genomic sequence variation at this leader-body junction site (ISU79 has UUGACC and VR-2332 has UUGACU) or to the different cell lines used for sgmRNA junction site analysis. The lengths of sequences preceding mRNAs 5, 6, and 7.1 agree with those of a Japanese isolate (EDRD-1 [52]), which was shown to be more related to North American isolates than to LV (38) (Table 3). Thus, with limited RT-PCR and sequence analysis, we have obtained evidence that the leader-body junction sites utilized by strain VR-2332 for mRNAs 4 and 7 seem to be more heterogeneous than previously reported. Because the initial RNA was isolated from swine alveolar macrophages, this finding suggests that more than one leader-body junction site may be utilized in vivo to produce at least some sgmRNAs.

When the untranslated sequence lengths between the leader and initiator AUG for the mRNAs of North American and Japanese isolates were compared to those of LV, significant differences were readily apparent (Table 3). Also, with the exception of mRNA 7 (see below), the alignment of nucleotide sequences from VR-2332 and LV ORFs 2 to 7 revealed that the junction site motifs used were poorly conserved between strains (data not shown). Strain-specific selection of leader-body junction sites and their placement in ORFs 2 to 7 delineate a clear biochemical difference between VR-2332 and LV.

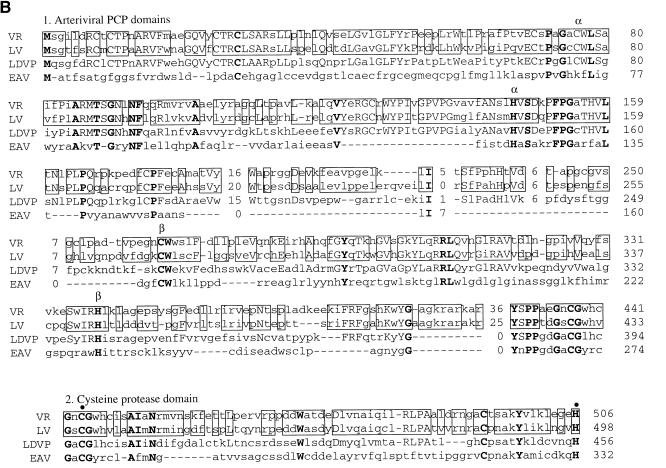

sgmRNA 7 junction site utilization in virally infected cells.

sgmRNA 7.1 and 7.2 (coding for the nucleocapsid [N] protein) (Table 3) were further investigated in order to confirm the difference in leader-body junction site utilization between North American and European strains and to assess the relative abundance of the two VR-2332-specific mRNA 7 species. VR-2332 and LV contain three potential leader-body junction motifs at the same relative positions (Fig. 4). However, Northern analysis of total RNA from VR-2332 and LV-infected MA-104 cells revealed two isoforms for VR-2332 and one for LV. When a Northern blot was analyzed with a VR-2332 ORF 7 sequence probe, one mRNA 7 was a highly abundant, slower-migrating band (presumably VR-2332 mRNA 7.1; see below) and the other was a less abundant, faster-migrating band (presumably VR-2332 mRNA 7.2) (Fig. 5A, lane 1). Both cloned (Fig. 5A, lane 1) and uncloned (data not shown) VR-2332 preparations exhibited similar profiles for mRNA 7. When the blot was reprobed for LV ORF 7 sequence, only one mobility species was discerned, which migrated with VR-2332 mRNA 7.2 (Fig. 5A, lane 2). Evidence of an LV mRNA 7 equivalent to VR-2332 mRNA 7.1 was not observed in the Northern analysis and has not been described previously (37).

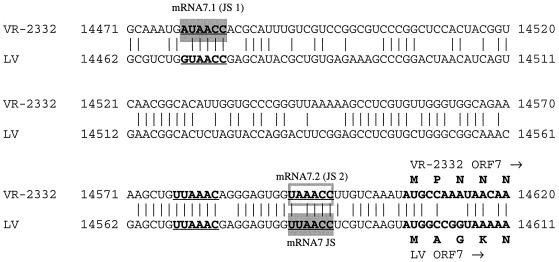

FIG. 4.

Predicted junction site motifs (bold and underlined) in VR-2332 and LV ORF 7. VR-2332 mRNA 7.1 utilizes the first junction site motif (JS 1) and mRNA 7.2 utilizes the third junction site motif (JS 2). LV uses the third junction site motif exclusively (37) (JS). A potential junction site motif at nucleotide 14577 (VR-2332) appears not to be used (Fig. 5). The beginning ORF 7 nucleotide and predicted protein sequences are shown in bold type (with the GAP program [fastadna.cmp], a gap weight of 16, and a length weight of 4).

FIG. 5.

(A) Northern blot analysis of PRRSV mRNA 7. Total RNA from cells infected with VR-2332 (lane 1) or LV (lane 2) were electrophoresed through an agarose gel and blotted onto a nylon membrane. The membrane was probed sequentially with a VR-2332 ORF 7 oligomer (lane 1) and then an oligomer to LV ORF 7 (lane 2). No nonspecific hybridization was detected in several analyses. (B) Northern blot analysis of total RNA from VR-2332-infected MA-104 (CL2621) cells and alveolar macrophages (AM) shows that junction site 1 is used to transcribe the majority of mRNA 7 (7.1) and that junction site 2 is used to transcribe a minority of mRNA 7 (7.2). Mock-, VR-2332-, and LV-infected-cell total RNA populations were electrophoresed through a 2% agarose gel and transferred to membranes. The membranes were probed with reverse complement oligomers to VR-2332 ORF 7 (a), VR-2332 ORF 7 junction site 1 (b), VR-2332 ORF 7 junction site 2 (c), and LV ORF 7 (d). An RNA ladder (Gibco BRL) was used to assess sgmRNA size.

We assessed whether all three junction sites were utilized during VR-2332 infection of simian MA-104 cells and of freshly isolated porcine alveolar macrophages, the natural host cell of the virus. Identification of mRNA 7.1 and 7.2 in infected alveolar macrophages would suggest that the two species of mRNA 7 are biologically relevant. Northern blots of total RNA from both types of infected cells were probed with radiolabeled VR-2332 or LV ORF 7 oligomers. VR-2332 expresses both mRNA 7.1 and 7.2 in both populations of cells (Fig. 5B, panel a). In addition, sgmRNA 7 leader-body junction oligomer probes were used to detect expression of each mRNA 7 species in infected cells. The VR-2332 leader-body junction site 1 probe (for the junction site 123 bases upstream of the ORF 7 AUG) hybridized to a species of mRNA that migrated with mRNA 7.1 in both populations of infected cells (Fig. 5B, panel b). Similarly, the junction site 2 probe (for the junction site 9 bases upstream of the ORF 7 AUG) identified mRNA 7.2 in both cell populations (Fig. 5B, panel c), which migrated with LV mRNA 7 (Fig. 5B, panel d). The other leader-body junction site (VR-2332 nucleotide 14577 in Fig. 4) was not detected in VR-2332-infected cells, indicating that this species was expressed at very low levels or not at all.

Therefore, both the North American strain VR-2332 and the European strain LV possess genomic sequences containing three similar leader-body junction motifs in the region preceding ORF 7. VR-2332 utilizes the site 123 bases upstream of the initiating ORF 7 AUG for the majority of mRNA 7 transcripts and the site 9 bases upstream for a minor fraction of them. LV, in contrast, utilizes only the site 9 bases upstream of ORF 7 for its mRNA 7 transcripts. No obvious consensus sequence or RNA structure surrounds the chosen leader-body junction motifs that are used (unpublished data). It is interesting that neither strain of PRRSV appears to utilize the third potential junction site, even though that putative junction site was completely conserved in both strains.

DISCUSSION

The complete comparative genome analysis and experimental data reported here confirm and extend the remarkable differences between North American and European PRRSV reported earlier from an analysis of the 3′ structural gene and noncoding region sequences (42). VR-2332, the North American prototype, exhibits substantial nucleotide and amino acid sequence and length divergence from the European prototype, LV, over the entire length of the virus. The identified protease and polymerase motifs in ORF 1, relatively well conserved during evolution, signify their importance for the maintenance of viable PRRSV virus. Other than these motifs, notably in the sequence and length of the 5′ leader, most of ORF 1a, and the region of ORF 1b corresponding to the C-terminal end of the product, the strains exhibit inordinate divergence. It is striking that these and other genotypic differences in ORFs 2 to 7 and the 3′ noncoding region do not manifest appreciable differences in disease phenotype. The data suggest the divergent evolution of related viruses on separate continents from a distant common ancestor and the simultaneous emergence of a new disease in swine.

In this report, we have examined the subgenomic messages produced in cells, and not only did we find that the leader-body junction sequences used for each mRNA of strain VR-2332 are different from those for LV mRNAs, but we also found evidence in infected swine macrophages that the VR-2332 sgmRNA junction sites utilized are variable, particularly in the case of mRNA 7. Although both VR-2332 and LV genomic sequences naturally contain potential leader junction sequences for mRNA 7 at three sites, only one particular site is used preferentially for transcription in each isolate. It appears that the leader sequence, ending in UUAACC, is joined to downstream leader-body junction motifs by more than simple base pair homology, since only a specific subset of potential leader-body motifs are utilized. Thus, we suggest that another viral nucleotide or protein sequence(s), secondary structure of the viral RNA, or other host factors may play a role in site selection. The differences in PRRSV polymerase proteins described in this report may play a key role in determining the choice of junction site utilized.

Multiple species of mRNA 7 were not previously described for any arterivirus. Multiple species of mRNA 3 were reported for EAV (14) and for PRRSV ISU79, although ISU79 mRNA 3-1 is predicted to encode a truncated ORF 3 protein (34). The ORF 3 protein is incorporated into the LV virion (65), but it has not been detected in any North American isolate or in other arteriviruses. The ORF 7 product, the N protein, is a fundamental protein found in all viruses and functions to enclose and protect the viral genome. Both LV and VR-2332 contain three potential junction sites (ending 123, 23, and 9 bases upstream of the ORF 7 initiator AUG [Fig. 4]) for mRNA 7 formation at the same relative positions in their genomes (38, 42), yet VR-2332 selects the junction site ending 123 bases upstream of ORF 7 (AUAACC) to produce most mRNA 7 while LV selects the site ending 9 bases upstream (UUAACC) to transcribe mRNA 7 (Fig. 4). This may indicate an essential need for a U in the second position and a C in the fifth position, but other mRNA junction sites (mRNAs 2, 4.2, and 5-1) indicate that different nucleotides can be tolerated in these positions. The significance of this difference among isolates of PRRSV is unknown.

The mechanism of leader-body junction site selection in arteriviruses is not well studied. However, coronavirus transcription has been examined by several investigators (reviewed in references 29, 53, and 64), and these investigators have obtained diverse results. Specific selection may be influenced by the primary 5′ leader sequence (30, 54, 69), sequences flanking the downstream consensus sequence (23, 24), the 3′ noncoding region (31), sequences in ORF 1 (63), or sequences at some other location on the genome. Secondary and tertiary structures of the RNA (18), viral replicase proteins, or in some cellular gene or protein with which viral genes or proteins interact during transcription may also influence junction site selection (70). In mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) defective interfering RNA studies, investigators found that the amount of subgenomic defective interfering transcription was influenced by the addition of novel intragenic (leader-body junction) sequences (25). The investigators concluded that downstream intragenic sequences suppressed transcription from the upstream intragenic region. This seems unlikely to be the case in arterivirus transcription, however, because both VR-2332 and LV genomic sequences naturally contain potential leader-body junction sequences for mRNA 7 at three sites, yet one particular site is used preferentially for transcription in each isolate. Arteriviruses, in contrast to coronaviruses, utilize a shorter leader-body junction sequence and have overlapping ORFs, which suggests that the two virus families may not use identical mechanisms to couple the leader to each junction site for formation of their mRNAs. It is possible that the different species of mRNA 7 detected in this study may instead be used to produce different proteins. VR-2332 ORF 7 is predicted to code for two smaller products (5.0 and 3.7 kDa) in addition to the N protein (13.6 kDa), whereas LV ORF 7 is predicted to code for only one additional product (5.9 kDa) in addition to the LV N protein (13.8 kDa). Alternatively, the two different mRNA 7 5′ untranslated leader sequences identified for VR-2332 may reflect different quantities of nucleocapsid protein expression needed at different times during infection.

The evidence presented in this report suggests that the genotypic differences between VR-2332 and LV and the simultaneous appearance of frank disease do not appear to be the result of recent recombination events between other viruses. If this were the case, the regions of noted similarity (the ORF 1b product and some structural proteins, in particular) would most likely be better conserved between VR-2332 and LV. Rather, the genomic and biochemical differences are considerable and extend throughout the genome of PRRSV, with moderate conservation interspersed with dissimilarity. Computer searches for sequences similar to PRRSV do not reveal a potential virus family, other than arteriviruses, for such a recombination event. It is possible that, because of very close similarity to LDV, the two strains of PRRSV evolved from an LDV-like viral ancestor on separate continents, as has been hypothesized previously (47). However, divergent PRRSV evolution does not explain the simultaneous appearance of similar diseases in the United States and Europe. The association of distinct PRRSV genotypes with a similar, new disease phenotype in swine might therefore be related to global changes in commercial swine management and husbandry.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Margaret Elam, Thy Truong, Judy Laber, and Dan Strom for excellent technical expertise and Vivek Kapur for a critical review of this paper.

Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health, Inc., University of Minnesota Agricultural Experiment Station, and Minnesota Pork Producers Association provided financial support for the research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abrahams J P, van den Berg M, van Batenburg E, Pleu C. Prediction of RNA secondary structure, including pseudoknotting, by computer simulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:3035–3044. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.10.3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baarsch M J, Wannemuehler M J, Molitor T W, Murtaugh M P. Detection of tumor necrosis factor alpha from porcine alveolar macrophages using an L929 fibroblast bioassay. J Immunol Methods. 1991;140:15–22. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(91)90121-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bautista E M, Meulenberg J J, Choi C S, Molitor T W. Structural polypeptides of the American (VR-2332) strain of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Arch Virol. 1996;141:1357–1365. doi: 10.1007/BF01718837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benfield D A, Nelson E, Collins J E, Harris L, Goyal S M, Robison D, Christianson W T, Morrison R B, Gorcyca D E, Chladek D W. Characterization of swine infertility and respiratory syndrome (SIRS) virus (isolate ATCC VR-2332) J Vet Diagn Investig. 1992;4:127–133. doi: 10.1177/104063879200400202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brinton M A, Gavin E I, Fernandez A V. Genotypic variation among six isolates of lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus. J Gen Virol. 1986;67:2673–2684. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-67-12-2673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown T. Analysis of RNA by northern and slot-blot hybridization. In: Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1993. pp. 4.9.1–4.9.14. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cavanagh D, Brian D A, Enjuanes L, Holmes K V, Lai M M, Laude H, Siddell S G, Spaan W, Taguchi F, Talbot P J. Recommendations of the Coronavirus Study Group for the nomenclature of the structural proteins, mRNAs, and genes of coronaviruses. Virology. 1990;176:306–307. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90259-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Z, Kuo L, Rowland R R R, Even C, Faaberg K S, Plagemann P G W. Sequences of 3′ end of genome and of 5′ end of open reading frame 1a of lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus (LDV) and common junction motifs between 5′ leader and bodies of seven subgenomic mRNAs. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:643–660. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-4-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Z, Faaberg K S, Plagemann P G W. Determination of the 5′ end of the lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus genome by two independent approaches. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:925–930. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-4-925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collins J E, Benfield D A, Christianson W T, Harris L, Hennings J C, Shaw D P, Goyal S M, McCullough S, Morrison R B, Joo H S, Gorcyca D E, Chladek D W. Isolation of swine infertility and respiratory syndrome virus (isolate ATCC VR-2332) in North America and experimental reproduction of the disease in gnotobiotic pigs. J Vet Diagn Investig. 1992;4:117–126. doi: 10.1177/104063879200400201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conzelmann K, Visser N, van Woensel P, Thiel H. Molecular characterization of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus, a member of the arterivirus group. Virology. 1993;193:329–339. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.den Boon J A, Snijder E J, Chirnside E D, de Vries A A F, Horzinek M C, Spaan W J M. Equine arteritis virus is not a togavirus but belongs to the cornaviruslike superfamily. J Virol. 1991;65:2910–2920. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.6.2910-2920.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.den Boon J A, Faaberg K S, Meulenberg J J M, Wassenaar A L M, Plagemann P G W, Gorbalenya A E, Snijder E J. Processing and evolution of the N-terminal region of the arterivirus replicase ORF1a protein: identification of two papainlike cysteine proteases. J Virol. 1995;69:4500–4505. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4500-4505.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.den Boon J A, Kleijnen M F, Spaan W J M, Snijder E J. Equine arteritis virus subgenomic mRNA synthesis: analysis of leader-body junctions and replicative-form RNAs. J Virol. 1996;70:4291–4298. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4291-4298.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Vries A A, Chirnside E D, Bredenbeek P J, Gravestein L A, Horzinek M C, Spaan W J. All subgenomic mRNAs of equine arteritis virus contain a common leader sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:3241–3247. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.11.3241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faaberg K S, Elam M R, Nelsen C J, Murtaugh M P. Subgenomic RNA7 is transcribed with different leader-body junction sites in PRRSV (strain VR2332) infection of CL2621 cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1998;440:275–279. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-5331-1_36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feinberg A P, Vogelstein B. A technique for radiolabeling DNA restriction endonuclease fragments to high specific activity. Anal Biochem. 1983;132:6–13. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fischer F, Stegen C F, Koetzner C A, Masters P S. Analysis of a recombinant mouse hepatitis virus expressing a foreign gene reveals a novel aspect of coronavirus transcription. J Virol. 1997;71:5148–5160. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5148-5160.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frohman M A. On beyond classic RACE (rapid amplification of cDNA ends) PCR Methods Appl. 1994;4:S40–S58. doi: 10.1101/gr.4.1.s40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Godeny E K, Chen L, Kumar S N, Methven S L, Koonin E V, Brinton M A. Complete genomic sequence and phylogenetic analysis of the lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus (LDV) Virology. 1990;194:585–596. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Godeny E K, de Vries A A F, Wang X C, Smith S L, de Groot R J. Identification of the leader-body junctions for the viral subgenomic mRNAs and organization of the simian hemorrhagic fever virus genome: evidence for gene duplication during arterivirus evolution. J Virol. 1998;72:862–867. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.862-867.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Habili N, Symons R H. Evolutionary relationship between luteoviruses and other RNA plant viruses based on sequence motifs in their putative RNA polymerases and nucleic acid helicases. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:9543–9555. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.23.9543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hiscox J A, Mawditt K L, Cavanagh D, Britton P. Characterization of the transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV) transcription initiation sequence. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1995;380:529–535. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1899-0_84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeong Y S, Repass J F, Kim Y N, Hwang S M, Makino S. Coronavirus transcription mediated by sequences flanking the transcription consensus sequence. Virology. 1996;217:311–322. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joo M, Makino S. Analysis of coronavirus transcription regulation. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1995;380:473–478. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1899-0_75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kapur V, Elam M R, Pawlovich T M, Murtaugh M P. Genetic variation in porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus isolates in the midwestern United States. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:1271–1276. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-6-1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keffaber K K. Reproductive failure of unknown etiology. Am Assoc Swine Prac Newsl. 1989;1:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuo L, Chen Z, Rowland R R R, Faaberg K S, Plagemann P G W. Lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus (LDV): subgenomic mRNAs, mRNA leader and comparison of 3′-terminal sequences of two LDV isolates. Virus Res. 1992;23:55–72. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(92)90067-J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai M M. Transcription, replication, recombination, and engineering of coronavirus genes. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1995;380:463–471. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1899-0_74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liao C-L, Lai M M C. Requirement of the 5′-end genomic sequence as an upstream cis-acting element for coronavirus subgenomic mRNA transcription. J Virol. 1994;68:4727–4737. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.4727-4737.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin Y-J, Zhang X, Wu R-C, Lai M M C. The 3′ untranslated region of coronavirus RNA is required for subgenomic mRNA transcription from a defective interfering RNA. J Virol. 1996;70:7236–7240. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.7236-7240.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mardassi H, Massive B, Dea S. Intracellular synthesis, processing, and transport of proteins encoded by ORFs 5 to 7 of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Virology. 1996;221:98–112. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meng X-J, Paul P S, Halbur P G. Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequences of the 3′-terminal genomic RNA of the porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:1795–1801. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-7-1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meng X-J, Paul P S, Morozov I, Halbur P G. A nested set of six or seven subgenomic mRNAs is formed in cells infected with different isolates of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:1265–1270. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-6-1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meulenberg J J, Petersen-den Besten A, De Kluyver E P, Moormann R J, Schaaper W M, Wensvoort G. Characterization of proteins encoded by ORFs 2 to 7 of Lelystad virus. Virology. 1995;206:155–163. doi: 10.1016/S0042-6822(95)80030-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meulenberg J J, Petersen-den Besten A. Identification and characterization of a sixth structural protein of Lelystad virus: the glycoprotein GP2 encoded by ORF2 is incorporated in virus particles. Virology. 1996;225:44–51. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meulenberg J J M, de Meijer E J, Moormann R J M. Subgenomic RNAs of Lelystad virus contain a conserved leader-body junction sequence. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:1697–1701. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-8-1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meulenberg J J M, Hulst M M, de Meijer E J, Moonen P L J M, den Besten A, de Kluyver E P, Wensvoort G, Moormann R J M. Lelystad virus, the causative agent of porcine epidemic abortion and respiratory syndrome (PEARS), is related to LDV and EAV. Virology. 1993;192:62–72. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meulenberg J J M, Bos-de Ruijter J N A, van de Graaf R, Wensvoort G, Moormann R J M. Infectious transcripts from cloned genome-length cDNA of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. J Virol. 1998;72:380–387. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.380-387.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morozov I, Meng X J, Paul P S. Sequence analysis of open reading frames (ORFs) 2 to 4 of a U.S. isolate of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus. Arch Virol. 1995;140:1313–1319. doi: 10.1007/BF01322758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mounir S, Mardassi H, Dea S. Identification and characterization of the porcine reproductive respiratory virus ORFs 7, 5 and 4 products. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1995;80:317–320. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1899-0_51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murtaugh M P, Elam M R, Kakach L T. Comparison of the structural protein coding sequences of the VR-2332 and Lelystad virus strains of the PRRS virus. Arch Virol. 1995;140:1451–1460. doi: 10.1007/BF01322671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nelson E A, Christopher-Hennings J, Benfield D A. Structural proteins of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) Adv Exp Med Biol. 1995;380:321–323. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1899-0_52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palmer G A, Kuo L, Chen Z, Faaberg K S, Plagemann P G W. Sequence of the genome of lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus: heterogenicity between strains P and C. Virology. 1995;209:637–642. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pirzadeh B, Dea S. Monoclonal antibodies to the ORF5 product of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus define linear neutralizing determinants. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:1867–1873. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-8-1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Plagemann P G W, Moennig B. Lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus, equine arteritis virus and simian hemorrhagic fever virus: a new group of positive stranded RNA viruses. Adv Virus Res. 1992;41:99–192. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60036-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Plagemann P G W. Lactate dehydrogenase-elevating virus and related viruses. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 1105–1120. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Poch O, Sauvaget I, Delarue M, Tordo N. Identification of four conserved motifs among the RNA dependent polymerase encoding elements. EMBO J. 1989;8:3867–3874. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08565.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rossow, K. D., J. L. Shivers, P. E. Yeske, D. D. Polson, R. R. R. Rowland, S. R. Lawson, M. P. Murtaugh, E. A. Nelson, and J. E. Collins. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus infection in neonatal pigs characterized by marked neurovirulence. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Sagripanti J L. Polyadenylic acid sequences in the genomic RNA of the togavirus of simian hemorrhagic fever. Virology. 1985;145:350–355. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(85)90171-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sagripanti J L, Zandomeni R O, Weinmann R. The cap structure of simian hemorrhagic fever virion RNA. Virology. 1986;151:146–150. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(86)90113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saito A, Kanno T, Murakami Y, Muramatsu M, Yamaguchi S. Characteristics of major structural protein coding gene and leader-body sequence in subgenomic mRNA of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus isolated in Japan. J Vet Med Sci. 1996;58:377–380. doi: 10.1292/jvms.58.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sawicki S G, Sawicki D L. Coronaviruses use discontinuous extension for synthesis of subgenome-length negative strands. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1995;380:499–506. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1899-0_79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shieh C K, Soe L H, Makino S, Chang M F, Stohlman S A, Lai M M. The 5′-end sequence of the murine coronavirus genome: implications for multiple fusion sites in leader-primed transcription. Virology. 1987;156:321–330. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90412-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith S L, Wang X, Godeny E K. Sequence of the 3′ end of the simian hemorrhagic fever virus genome. Gene. 1997;191:205–210. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(97)00061-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Snijder E J, Wassenaar A L M, Spaan W J M. The 5′ end of the equine arteritis virus replicase gene encodes a papainlike cysteine protease. J Virol. 1992;66:7040–7048. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.12.7040-7048.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Snijder E J, Wassenaar A L M, Spaan W J M. Proteolytic processing of the replicase ORF1a protein of equine arteritis virus. J Virol. 1994;68:5755–5764. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5755-5764.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Snijder E J, Wassenaar A L, Spaan W J, Gorbalenya A E. The arterivirus Nsp2 protease. An unusual cysteine protease with primary structure similarities to both papain-like and chymotrypsin-like proteases. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:16671–16676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.28.16671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Snijder E J, Meulenberg J J. The molecular biology of arteriviruses. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:961–979. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-5-961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Triezenberg S J. Primer extension. In: Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1992. pp. 4.8.1–4.8.5. [Google Scholar]

- 61.van Berlo M F, Horzinek M C, van der Zeijst B A. Equine arteritis virus-infected cells contain six polyadenylated virus-specific RNAs. Virology. 1982;30:345–352. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(82)90354-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van Dinten L C, Wassenaar A L M, Gorbalenya A E, Spaan W J M, Snijder E J. Processing of the equine arteritis virus replicase ORF1b protein: identification of cleavage products containing the putative viral polymerase and helicase domains. J Virol. 1996;70:6625–6633. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.6625-6633.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van Dinten L C, den Boon J A, Wassenaar A L, Spaan W J, Snijder E J. An infectious arterivirus cDNA clone: identification of a replicase point mutation that abolishes discontinuous mRNA transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:991–996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.3.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.van Marle G, van der Most R G, van der Straaten T, Luytjes W, Spaan W J. Regulation of transcription of coronaviruses. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1995;380:507–510. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1899-0_80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van Nieuwstadt A P, Meulenberg J J M, van Essen-Zandbergen A, Petersen-den Besten A, Bende R J, Moormann R J M, Wensvoort G. Proteins encoded by open reading frames 3 and 4 of the genome of Lelystad virus (Arteriviridae) are structural proteins of the virion. J Virol. 1996;70:4767–4772. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4767-4772.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wassenaar A L M, Spaan W J M, Gorbalenya A E, Snijder E J. Alternative proteolytic processing of the arterivirus replicase ORF1a polyprotein: evidence that NSP2 acts as a cofactor for the NSP4 serine protease. J Virol. 1997;71:9313–9322. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9313-9322.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wensvoort G, Terpstra C, Pol J M A, ter Laak E A, Bloemraad M, de Kluyver E P, Kragten C, van Buiten L, den Besten A, Wagenaar F, Broekhuijsen J M, Moonen P L J M, Zetstra T, de Boer E A, Tibben H J, de Jong M F, van’t Veld P, Groenland G J R, van Gennep J A, Voets M T, Verheijden J H M, Braamskamp J. Mystery swine disease in the Netherlands: the isolation of Lelystad virus. Vet Q. 1991;13:121–130. doi: 10.1080/01652176.1991.9694296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zeng L, Godeny E K, Methven S L, Brinton M A. Analysis of simian hemorrhagic fever virus (SHFV) subgenomic RNAs, junction sequences, and 5′ leader. Virology. 1995;207:543–548. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang X, Liao C-L, Lai M M C. Coronavirus leader RNA regulates and initiates subgenomic mRNA transcription both in trans and in cis. J Virol. 1994;68:4738–4746. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.4738-4746.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang X, Lai M M C. Interactions between the cytoplasmic proteins and the intergenic (promoter) sequence of mouse hepatitis virus RNA: correlation with the amounts of subgenomic mRNA transcribed. J Virol. 1995;69:1637–1644. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1637-1644.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]