Abstract

Cytokines are potent stimuli for CD4+-T-cell differentiation. Among them, interleukin-12 (IL-12) and IL-4 induce naive CD4+ T cells to become T-helper 1 (Th1) or Th2 cells, respectively. In this study we found that macrophage-tropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) strains replicated more efficiently in IL-12-induced Th1-type cultures derived from normal CD4+ T cells than did T-cell-line-tropic (T-tropic) strains. In contrast, T-tropic strains preferentially infected IL-4-induced Th2-type cultures derived from the same donor CD4+ T cells. Additional studies using chimeric viruses demonstrated that the V3 region of HIV-1 gp120 was the principal determinant for efficiency of replication. Cell fusion analysis showed that cells expressing envelope protein from a T-tropic strain effectively fused with IL-4-induced Th2-type culture cells. Flow cytometric analysis showed that the level of CCR5 expression was higher on IL-12-induced Th1-type culture cells, whereas CXCR4 was highly expressed on IL-4-induced Th2-type culture cells, although a low level of CXCR4 expression was observed on IL-12-induced Th1-type culture cells. These results indicate that HIV-1 isolates exhibit differences in the ability to infect CD4+-T-cell subsets such as Th1 or Th2 cells and that this difference may partly correlate with the expression of particular chemokine receptors on these cells. The findings suggest that immunological conditions are one of the factors responsible for inducing selection of HIV-1 strains.

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) isolates are classified into two main groups, macrophage-tropic (M-tropic) and T-cell-line-tropic (T-tropic) strains, depending on their ability to infect preferentially either macrophages or laboratory-derived T-cell lines, respectively. The M-tropic strains predominant early in the course of infection, when individuals are generally asymptomatic, and typically evolve to T-tropic strains as the disease progresses (4, 9, 21). This switch is likely to be relevant to the development of AIDS in infected individuals. Despite these differences in tropism, both M- and T-tropic viruses are able to infect primary CD4+ T cells (47, 57). The primary CD4+ T cells are classified into three subsets, i.e., T-helper 1 (Th1), Th2, and Th0, as defined by differences in their immune responses and patterns of cytokine production (42, 49, 51). Several cytokines secreted from Th1 and Th2 cells mutually inhibit the differentiation maintenance and functions of the reciprocal cell type. This cross-regulation may partly explain the predominance of either a Th1- or Th2-type response during infection by particular pathogens (1, 43). Some reports have noted that in vitro-stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) and cloned T cells derived from HIV-1-infected individuals in early stages of infection preferentially produce Th1-type cytokines, such as interleukin-2 (IL-2) and gamma interferon (IFN-γ), whereas cells derived from HIV-1-infected patients in late stages of disease preferentially secrete Th2-type cytokines, such as IL-4 (12, 34). It is possible that differences in the ability of HIV-1 to replicate under either Th1- or Th2-type immunological conditions may be relevant to the shift from M- to T-tropic HIV-1 strains.

In this study, we show that M-tropic viruses preferentially infect IL-12-induced Th1-type culture cells and that T-tropic viruses preferentially infect IL-4-induced Th2-type culture cells. This difference in tropism is determined by the V3 loop of HIV-1 gp120. These findings show that Th1- and Th2-type cytokine-induced environments are fundamentally linked to the evolution of viruses with distinct cell tropisms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 culture medium containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 U of penicillin per ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin per ml. PBMC were isolated from healthy HIV-1-seronegative donors, and CD4+ T cells were enriched by using immunomagnetic M-450 CD4 beads and isolated with M-450 CD4 DETACHaBEADS (Dynal, Oslo, Norway). For the IL-12-induced Th1-type culture, CD4+ T cells or CD4+/CD45RA+ T cells were purified with anti-CD45RA monoclonal antibody (MAb) (Immunotech, Marseille, France) (more than 98% CD3+ cells) and stimulated with anti-CD3 MAb OKT3 (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, Md.) immobilized on plates in the presence of IL-2 (100 IU/ml; Shionogi, Osaka, Japan) and IL-12 (10 ng/ml; R&D, Minneapolis, Minn.) as described previously (52). For the IL-4-induced Th2-type culture, CD4+ T cells or CD4+/CD45RA+ T cells were isolated and then maintained with culture medium containing IL-2 and IL-4 (10 ng/ml; R&D) on an OKT3-immobilized plate. At days 3 and 6, the cells were restimulated with OKT3.

Monocyte-derived macrophage (MDM) cells were prepared as described previously (30). HTLV-I+/CD4+ MT-4 cells, CD4+/CD8+ MOLT4 cells, and PBMC activated with phytohemagglutinin (PHA) for 2 days (PHA-PBMC) were cultured as described previously (30).

Intracellular cytokine analysis.

Eight days after initiation of culture, 2 × 106 IL-12-induced Th1- and IL-4-induced Th2-type culture cells were stimulated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.), 1 μg of ionomycin (Sigma) per ml, and 10 μg of brefeldin-A (Sigma) per ml for 4 h at 37°C. Cells were incubated with 1× fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) lysing solution (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.) for 10 min at room temperature and permeabilized with 500 μl of FACS permeabilizing solution (Becton Dickinson) for 10 min. After being washed with phosphate-buffered saline containing 2% FCS, the cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled antibody against IFN-γ and phycoerythrin-labeled antibody against IL-4 (Fastimmune; Becton Dickinson) for 30 min and fixed with 1% (vol/vol) paraformaldehyde. Cell samples were analyzed with a FACScan (Becton Dickinson).

Construction of recombinant HIV-1 infectious DNA.

Chimeric HIV-1 plasmid DNA constructs were derived mainly from JR-CSF (M-tropic strain) (32) and NL4-3 (T-tropic strain) (2) infectious plasmid DNAs (pJR-CSF and pNL4-3, respectively). Construction of HIV-1 chimeric infectious plasmids pCNC-DX, pCNC-MX, pNCN-SX, pNCN-SN, pNCN-SM, and pNCN-MN was based on the method described previously by Chesebro et al. (10), and pCNC-AD and pNCN-DX were constructed by using similar methods. Other chimeric proviral DNA clones derived from NL4-3 and JR-FL (M-tropic strain), pNFN-SX, pMXFLV3, and pNLFLV3, were described previously (45). pNLCSFV3 was prepared by exchanging the V3 loop region from pJR-CSF in pNL4-3 as described previously (10), with the following modifications. pNL4-3 was digested with FspI, and an extra StuI site in the 5′ flanking region was removed. This modified plasmid DNA, pNL4-3-10-17, contained unique restriction sites at positions 6822 (StuI) and 7247 (NheI), and a double-stranded synthetic oligonucleotide (sense, 5′-CCT ACG CGT CTA GAC CGC GG-3′; antisense, 5′-CTA GCC GCG GTC TAG ACG CGT AGG-3′) containing StuI, MluI, XbaI, and NheI sites was inserted into the StuI and NheI sites. In the next step, a 299-bp DNA fragment of NL4-3 from the StuI site (6822) to the MluI site (7121) was amplified by PCR to create an MluI site, and double-stranded oligonucleotides corresponding to the pJR-CSF sequence from the MluI site (7121) to the XbaI site (7211) (sense, 5′-CG CGT AAA AGT ATC CAT ATC GGA CCA GGG AGA GCA TTT TAT ACA ACA GGA GAA ATA ATA GGA GAT ATA AGA CAA GCA CAT TGT AAC ATT T-3′; antisense, 5′-CT AGA AAT GTT ACA ATG TGC TTG TCT TAT ATC TCC TAT TAT TTC TCC TGT TGT ATA AAA TGC TCT CCC TGG TCC GAC ATG GAT ACT TTT A-3′) and to the pNL4-3 sequence from the XbaI site (7211) to the NheI site (7247) (sense, 5′-CTA GAG CAA AAT GGA ATG CCA CTT TAA AAC AGA TAG-3′; antisense, 5′-CTA GCT ATC TGT TTT AAA GTG GCA TTC CAT TTT GCT-3′) were synthesized and inserted into the appropriate StuI, MluI, and NheI sites of modified pNL4-3-10-17. To confirm that these mutations did not affect the viral infectivity, synthetic oligonucleotides of pNL4-3 sequence from the MluI site to the XbaI site (sense, 5′-CG CGT AAA AGT ATC CGT ATC CAG AGG GGA CCA GGG AGA GCA TTT TAT ACA ACA GGA GAA ATA ATA GGA GAT ATA AGA CAA GCA CAT TGT AAC ATT T-3′; antisense, 5′-CT AGA AAT GTT ACA ATG TGC TTG TCT TAT ATC TCC TAT TAT TTC TCC TGT TGT ATA AAA TGC TCT CCC TGG TCC CCT CTG GAT ACG GAT ACT TTT A-3′) were replaced with those of pNLCSFV3, and the virus derived was indistinguishable from the original NL4-3 with regard to infectivity and tropism for MT-4 cells. All mutant plasmids were confirmed by sequencing analysis.

Viruses.

HIV-1 virus stocks from COS cells transfected with HIV-1 infectious DNA were prepared as described before (30). The 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) of each virus stock was determined by end point titration of threefold dilutions in triplicate on PHA-PBMC from a single donor. TCID50 values were determined by the Reed-Muench method as described previously (30). A recombinant vaccinia virus which expresses Env derived from JR-CSF (the env sequence from position 6236 to 8782 was amplified by PCR and cloned into a pBSF216 insertion vector) was generated as described previously (27).

HIV-1 infection.

Th1- or Th2-type culture cells induced for 8 days with IL-12 or IL-4 were exposed to 200 TCID50 of virus per 2 × 105 cells for 2 h at 37°C. MT-4 cells and PHA-PBMC were infected in parallel with the same dose of virus. After triplicate washing with medium to remove residual free virus, IL-12-induced Th1- and IL-4-induced Th2-type culture cells were cultured in the presence of IL-2 (100 IU/ml) and IL-12 (10 ng/ml) or in the presence of IL-2 and IL-4 (10 ng/ml), respectively. MT-4 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS, and PHA-PBMC were similarly cultured with the addition of IL-2. MDM cells were exposed for 2 h at 37°C to 30 TCID50 of virus per 3 × 104 cells. After triplicate washing with medium, MDM cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FCS and 5% giant cell tumor-conditioned medium (GCT-CM) (Origen, Rockville, Md.). Virus production in culture supernatant from HIV-1-infected cells at 11 days after infection was measured by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay specific for the HIV-1 p24gag antigen (Coulter, Hialeah, Fla.).

Cell-cell fusion assay.

For introduction of the HIV-1 env gene into cells, 2 × 105 HeLaS3 cells were infected for 2 h at 37°C with 106 PFU of a recombinant vaccinia virus (27) which expresses Env derived from JR-CSF or IIIB or with a control recombinant vaccinia virus (27). After being washed, cells were suspended in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FCS and treated with anti-vaccinia virus Ab 2D5 (26) to inhibit vaccinia virus-induced cell fusion. Env-expressing HeLaS3 cells were cocultured with IL-12-induced Th1- or IL-4-induced Th2-type culture cells in RPMI containing 10% FCS and 100 IU of IL-2 per ml for 16 h at 37°C, and fusion cells were observed by light microscopy.

Flow cytometric analysis of CCR5 and CXCR4 expression.

One million IL-12-induced Th1- or IL-4-induced Th2-type culture cells were incubated with a specific MAb against CCR5 (R&D) or CXCR4 (12G5) (20) for 30 min at 4°C. After triplicate washing, cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled antibody against mouse immunoglobulin G for 30 min at 4°C and fixed with 500 μl of phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.5% (vol/vol) formaldehyde. Cells were then analyzed with a FACScan (Becton Dickinson).

RESULTS

Preparation of IL-12-induced Th1- or IL-4-induced Th2-type cultures.

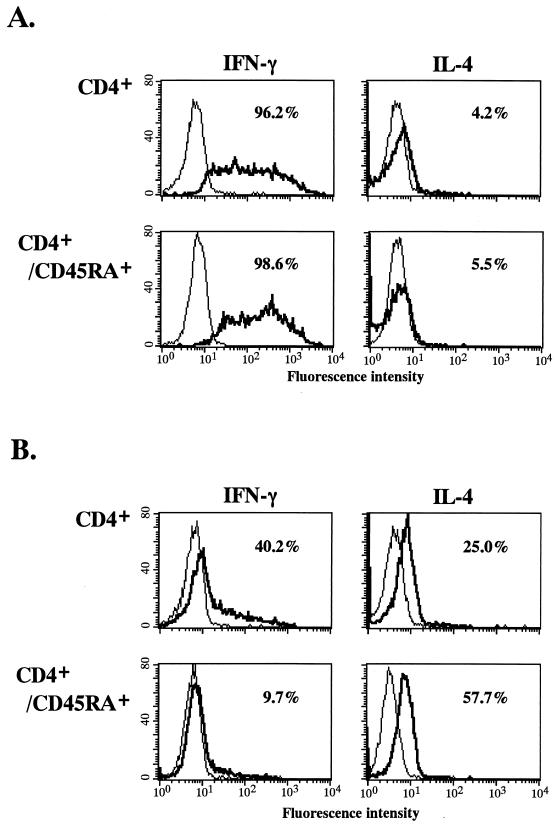

Cytokine-induced Th1- and Th2-type CD4+-T-cell cultures were prepared from normal adult peripheral bulk CD4+ T cells or peripheral naive CD4+/CD45RA+ T cells. Figure 1 shows intracellular IFN-γ and IL-4 staining patterns of these cultured cells. IL-12-induced cultures (Th1-type CD4+-T-cell culture) from CD4+ or CD4+/CD45RA+ T cells consisted mainly of IFN-γ-producing cells (96.2 and 98.6%, respectively) with few IL-4-producing cells (4.2 and 5.5%, respectively) (Fig. 1A). In contrast, a high level of IL-4-producing cells (57.7%) but few IFN-γ-producing cells (9.7%) were present in the IL-4-induced culture (Th2-type CD4+-T-cell culture) derived from only CD4+/CD45RA+ T cells, whereas high levels of IFN-γ--producing cells (40.2%) were detected from IL-4-treated bulk CD4+ T cells (Fig. 1B). High levels of cells producing IFN-γ (50.2%) or IL-4 (23.9%) alone were maintained by an additional 7 days of continuous treatment with IL-12 or IL-4, even after removal of OKT3 stimulation, for the Th1- and Th2-type cultures, respectively. In contrast, decreased levels of IFN-γ (16.5%)- or IL-4 (4.4%)-producing cells were detected in the same Th1- or Th2-type culture cells without additional IL-12- or IL-4-treatment. Therefore, we used the CD4+-T-cell-derived cultures as the Th1-type culture and the CD4+/CD45RA+-T-cell-derived cultures as the Th2-type culture in subsequent infection experiments, and we continuously added IL-12 or IL-4, respectively, after HIV-1 infection. Since similar kinetics of cell proliferation for the Th1-type and Th2-type cultures were observed, it is possible to compare the replication potentials of HIV-1 strains in these Th culture cells (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Characterization of IL-12 (A)- or IL-4 (B)-induced CD4+ or CD4+/CD45RA+ T-cell cultures by intracellular cytokine analysis. Eight-day-old cultures were stimulated with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, ionomycin, and brefeldin-A for 4 h. After permeabilization, cells were stained with a MAb against IFN-γ or IL-4 and analyzed with a FACScan. Percentages of IFN-γ+ and IL-4+ cells are shown. The percentages of IFN-γ and IL-4 double-positive Th0 cells were less than 1.3 and 1.0% in IL-12- and IL-4-induced culture cells, respectively. Results are from three independent experiments with three different blood donors.

Tropism of chimeric HIV-1 clones.

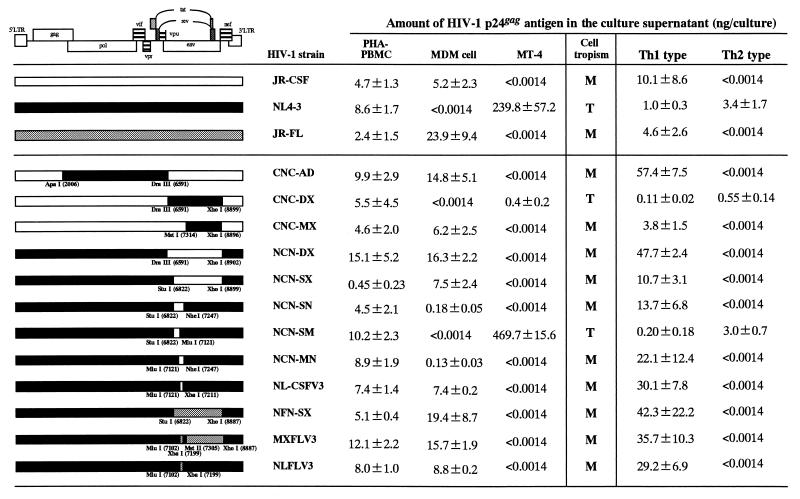

As we described previously, molecularly cloned M-tropic HIV-1 (JR-CSF) replicates in IL-12-induced Th1-type cultures more efficiently than molecularly cloned T-tropic HIV-1 (NL4-3) (52). To determine which region of the M-tropic HIV-1 is involved in efficient replication in the IL-12-induced Th1-type culture, we constructed HIV-1 chimera clones from two parental isolates, JR-CSF and NL4-3. Figure 2 illustrates three JR-CSF-based recombinant viruses with substitutions involving corresponding proviral DNA fragments from NL4-3 and also six NL4-3-based recombinant viruses which contained substitutions from JR-CSF. We also prepared three NL4-3-based recombinant viruses with substitution of DNA fragments from another M-tropic HIV-1 strain, JR-FL. Initially, these chimeric viruses were inoculated into PHA-PBMC, MDM cells, and MT-4 cells, and their replication patterns were measured by the HIV-1 p24gag assay in cultures. All chimeric HIV-1 strains replicated competently in PHA-PBMC (Fig. 2). In MDM cells, JR-CSF, JR-FL, and chimeric viruses possessing the V3 loop sequence derived from these M-tropic HIV-1 strains (CNC-AD, CNC-MX, NCN-DX, NCN-SX, NCN-SN, NCN-MN, NLCSFV3, NFN-SX, MXFLV3, and NLFLV3) preferentially replicated. In MT-4 cells, only NL4-3 and chimeric viruses possessing the V3 loop derived from this T-tropic HIV-1 strain (CNC-DX and NCN-SM) could replicate (Fig. 2) (10). These observation support the importance of the V3 loop sequence for cell tropism, as described previously (10).

FIG. 2.

Comparison of HIV-1 replication in PHA-PBMC, MT-4 cells, MDM cells, an IL-12-induced Th1-type culture, and an IL-4-induced Th2-type culture with molecular clones JR-CSF, JR-FL, and NL4-3 and chimeric viruses PHA-PBMC, MT-4 cells, Th1-type cells, and Th2-type cells (2 × 105) were infected with 200 TCID50 of virus. Thirty thousand MDM cells were infected with 30 TCID50 of virus. The amount of HIV-1 p24gag (nanograms/culture) in the culture medium was measured 11 days (PHA-PBMC, MT-4 cells, Th1-type cells, and Th2-type cells) and 21 days (MDM cells) after infection. Values represent the means and standard deviations from triplicate determinations. Results of one representative experiment with PHA-PBMC, MDM cells, Th1-type cells, and Th2-type cells from a single donor are shown. Similar levels of HIV-1 p24gag production were observed for the other three blood donors. The HIV-1 p24gag level in three primary cultures varied 1.2-fold for PHA-PBMC, 5.0-fold for MDM cells, 4.8-fold for Th1-type cells, and 18.6-fold for Th2-type cells.

Infection of IL-12-induced Th1-type culture cells with chimeric HIV-1.

In the next series of experiments, we tested the preferences of recombinant HIV-1 for IL-12-induced Th1-type cultures. In these experiments, the cells were continuously treated with IL-12 in the Th1-type culture after HIV-1 infection to maintain the Th1-type environment. Comparison of the mean levels of HIV-1 p24gag production showed that JR-CSF and JR-FL proliferated 10- and 4.6-fold more efficiently, respectively, than NL4-3 in the Th1-type culture at 11 days after infection (Fig. 2). FACS analyses indicated that high levels of HIV-1-producing cells (more than 90% of the cells) were detected in either JR-CSF- or NL4-3-infected cultures by staining with an anti-HIV-1 specific human antibody (data not shown). The JR-CSF-based recombinant virus, CNC-DX, containing the fragment from the NL4-3 clone between the DraIII (position 6591) and XhoI (8899) sites (2.3 kb), did not preferentially replicate in the IL-12-induced Th1-type culture. However, high levels of HIV-1 replication similar to those of JR-CSF were observed in cultures infected with the JR-CSF-based recombinant viruses CNC-AD and CNC-MX (with a replaced internal fragment from NL4-3 between the ApaI [2006] and DraIII [6591] sites [4.5 kb] or between the MstII [7314] and XhoI [8896] sites [2.5 kb], respectively). These observations suggested that part of the env region located between the DraIII (6591) and MstII (7314) sites of JR-CSF might be important for efficient proliferation in the IL-12-induced Th1-type culture. To confirm this, six chimeric HIV-1 strains with various internal env fragments of JR-CSF in NL4-3-based proviral DNA were inoculated into the IL-12-induced Th1-type culture, and supernatants were tested for HIV-1 p24gag production 11 days after infection. NCN-DX and NCN-SX, which contain nearly all of the env region of JR-CSF (encoding the N-terminal 126 amino acids of Env gp120 derived from NL4-3 and the rest of 378 amino acids from JR-CSF in NCN-DX) displayed efficient proliferation similar to that of JR-CSF and JR-FL. NCN-SN and NCN-MN, which contain a part of the env region of JR-CSF, also replicated well in the IL-12-induced Th1-type culture, in contrast to NCN-SM, which could not efficiently replicate. NCN-SN has a substitution of a 425-bp fragment from JR-CSF between the StuI (position 6822) and NheI (7247) sites in the NL4-3 proviral DNA. In this 425-bp fragment, the V3 loop sequence is located in the latter half between the MluI (7121) and NheI (7247) sites. The fact that NCN-MN but not NCN-SM could replicate in the IL-12-induced Th1-type culture indicated that the V3 loop sequence of M-tropic HIV-1 may be necessary for efficient HIV-1 replication in IL-12-induced Th1-type cultures. This speculation was confirmed by using another set of recombinant viruses. The NL4-3-based virus NLCSFV3, which encodes only 35 amino acids of the V3 loop of JR-CSF, also replicated vigorously in IL-12-induced Th1-enriched cultures. Similarly, the three NL4-3-based viruses containing the V3 loop sequence of JR-FL (NFN-SX, MXFLV3 and NLFLV3) replicated efficiently in the IL-12-induced Th1-type culture in a manner similar to that of JR-CSF and JR-FL. Since differences in cell proliferation among infected cells were not observed during these experiments, it is unlikely that the low level of HIV-1 replication with NL4-3, CNC-DX, and NCN-SM infection is due to its cytotoxic effect against target cells (data not shown). These results demonstrate the major influence of the V3 loop sequence, specifically allowing high levels of HIV-1 replication under the IL-12-induced Th1-type immunological conditions.

Infection of IL-4-induced Th2-type culture cells with chimeric HIV-1.

We infected the IL-4-induced Th2-type culture with NL4-3, JR-CSF, JR-FL, or recombinant viruses. IL-4 was added after HIV-1 infection to maintain Th2-type conditions. Figure 2 shows HIV-1 p24gag production in supernatants from IL-4-induced Th2-type cultures 11 days after infection. NL4-3 was able to replicate about 1,000 to 3,000 times more efficiently than JR-CSF and JR-FL (Fig. 2). FACS analysis with anti-HIV-1 human antibody indicated that more than 95% of the cells produced HIV-1 in the NL4-3-infected culture, versus only 11% in the JR-CSF-infected culture, at 7 days postinfection (data not shown). The JR-CSF-based recombinant virus CNC-DX, which replicated less efficiently in the IL-12-induced Th1-type culture, replicated to a level similar to that of NL4-3 in the IL-4-induced Th2-type culture. JR-CSF-based recombinant viruses that efficiently proliferated in IL-12-induced Th1-type cultures, such as CNC-AD and CNC-MX, replicated less efficiently in the IL-4-induced Th2-type cultures. These results suggest that the region between the DraIII (position 6591) and MstII (7314) sites, which contains the V1, V2, and V3 regions of gp120, is necessary for replication in the IL-4-induced Th2-type culture. Furthermore, all NL4-3-based recombinant viruses which replicated efficiently in the IL-12-induced Th1-type culture (NCN-DX, NCN-SX, NCN-SN, NCN-MN, NLCSFV3, NFN-SX, MXFLV3, and NLFLV3) did not replicate well in the IL-4-induced Th2-type culture (Fig. 2). Loss of replication in the IL-4-induced Th2-type cultures was observed after change of only the V3 loop region from that of T-tropic to that of M-tropic HIV-1. Only one NL4-3-based recombinant virus, NCN-SM, productively replicated in the IL-4-induced Th2-type culture. Also, we did not find differences in cell proliferation status among HIV-1-infected IL-4-induced Th2-type cultures. Thus, our results showed that the infectivity for the IL-4-induced Th2 type culture can also be specifically determined by the V3 loop sequence of the T-tropic HIV-1.

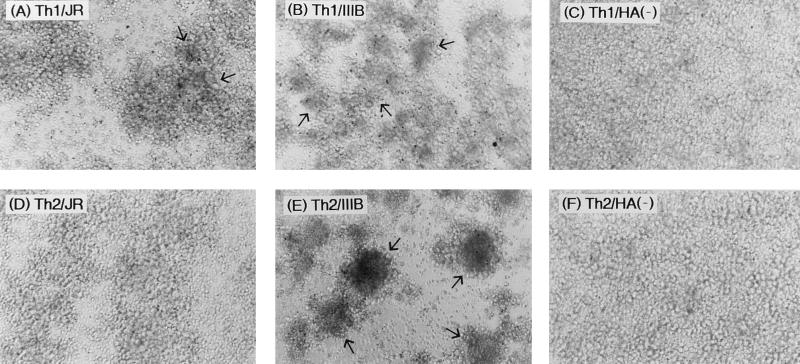

Efficiency of fusion of cytokine-induced Th1- and Th2-type culture cells to Env-expressing cells.

It is well known that chemokine receptors, especially CCR5 and CXCR4, are the major coreceptors for M-tropic and T-tropic HIV-1, respectively (3, 17, 19), and that the usage of these coreceptors can be determined by the V3 loop region of HIV-1 (11, 15). Based on the results of the above-described experiments that the IL-12-induced Th1- or IL-4-induced Th2-type culture preference of HIV-1 was determined by the V3 loop sequence, we thought it possible that preference was determined in the viral entry step. Thus, we next examined the efficiency of direct fusion of cytokine-induced Th1- and Th2-type culture cells with HIV-1 Env-expressing cells. It was reported that cells expressing JR-CSF or IIIB Env by infection with recombinant vaccinia virus fused specifically to CCR5+ or CXCR4+ cells, respectively (18). Figure 3 shows the formation of a large syncytium following overnight coculture of IIIB Env-expressing cells and IL-4-induced Th2-type culture cells. In contrast, IL-12-induced Th1-type culture cells fused less efficiently with IIIB Env-expressing cells. However, fusion with IL-12-induced Th1-type culture cells resulted in a slightly larger syncytium than seen for the IL-4-induced Th2-type culture cells cocultivated with JR-CSF Env-expressing cells (Fig. 3). No syncytia were formed following coculture of hemagglutinin-negative control vaccinia virus-infected HeLaS3 cells and either IL-12-induced Th1-type or IL-4-induced Th2-type culture cells.

FIG. 3.

Representative photomicrographs showing cell-cell fusion of HIV Env-expressing HeLaS3 cells and IL-12-induced Th1- or IL-4-induced Th2-type culture cells. JR-CSF (A and D) or IIIB (B and E) Env-expressing HeLaS3 cells, or hemagglutinin (HA)-negative control vaccinia virus-infected HeLaS3 cells (C and F), were cocultured with IL-12-induced Th1- or IL-4-induced Th2-type culture cells for 16 h. Note the presence of typical syncytium-forming cells (giant cells) between Env-expressing HeLaS3 cells and IL-12-induced Th1- or IL-4-induced Th2-type culture cells (arrows). Magnification, ca. ×240.

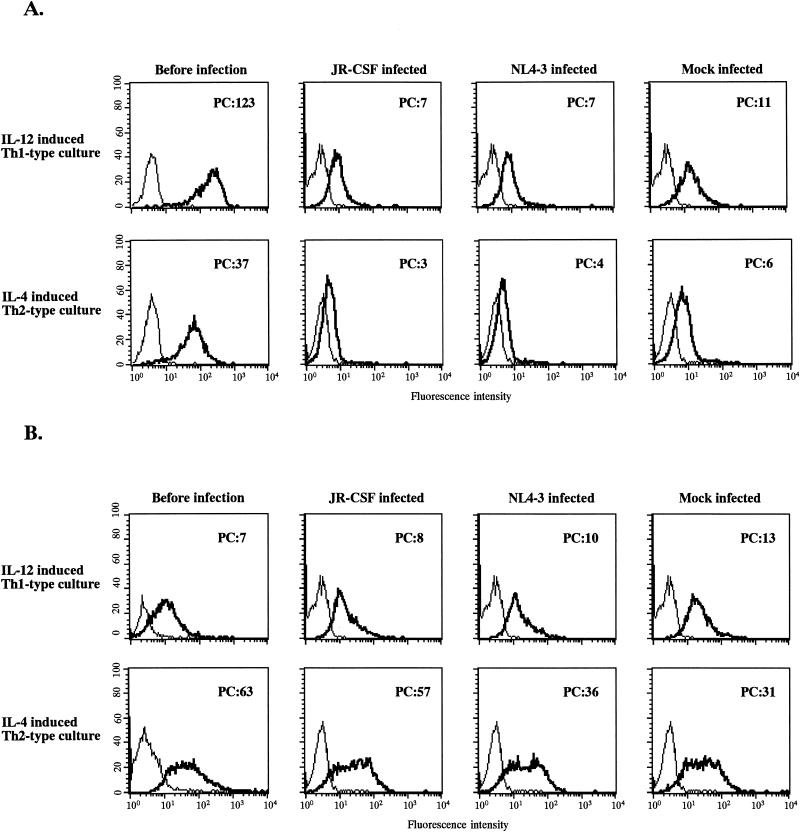

Expression of chemokine receptors.

We next analyzed the levels of expression of the chemokine receptors. The levels of CCR5 and CXCR4 expression on the surfaces of the IL-12-induced Th1- and IL-4-induced Th2-type culture cells before HIV-1 infection were compared by using a CCR5- or CXCR4-specific MAb and FACS analysis. The expression of CCR5 on the IL-12-induced Th1-type culture cells was slightly higher than that on the IL-4-induced Th2-type culture cells (Fig. 4A). In contrast, the expression of CXCR4 on the IL-4-induced Th2-type culture cells was slightly higher than that on the IL-12-induced Th1-type culture cells (Fig. 4B). Additional FACS analyses showed that the level of CCR5 expression in the JR-CSF-, NL4-3-, or mock-infected cultures was significantly down-regulated after 4 days of culture without anti-CD3 stimulation. This CCR5 down-regulation corresponds to results reported previously (41). However, the CCR5 expression on HIV-1- or mock-infected IL-12-induced Th1-type culture cells was still slightly higher than that on HIV-1- or mock-infected IL-4-induced Th2-type culture cells, whereas the level of CXCR4 expression on HIV-1- or mock-infected IL-4-induced Th2-type culture cells was significantly higher than that on HIV-1- or mock-infected IL-12-induced Th1-type culture cells (Fig. 4). The level of CXCR4 was unchanged after 4 days of culture without anti-CD3 stimulation. Since we also observed similar levels of CXCR4 expression after 7 days of culture without anti-CD3 stimulation, the CXCR4 expression appeared to be stable (data not shown). These results suggested that the distinct levels of expression levels of cell surface chemokine receptors in the IL-12-induced Th1- and IL-4-induced Th2-type cultures are associated with cytokine-induced Th1- and Th2-type preferences of the M-tropic and T-tropic HIV-1 strains, respectively.

FIG. 4.

Expression of CCR5 (A) and CXCR4 (B) on IL-12-induced Th1- and IL-4-induced Th2-type cells before or after HIV-1 infection. Cells were stained with an anti-CCR5 or anti-CXCR4 MAb before or 4 days after JR-CSF or NL4-3 infection. Samples were analyzed with a FACScan. Results of one representative experiment for two different blood donors are shown. PC, mean of peak channel in three individual experiments.

DISCUSSION

In this study we have demonstrated that HIV-1 isolates differ in their ability to infect cytokine-induced Th1- or Th2-type cultures and that this difference partially correlates with the expression of chemokine receptors on these cells. M-tropic viruses, which use CCR5, were shown to preferentially infect IL-12-induced Th1-type cultures, while T-tropic isolates, which use CXCR4, were shown to preferentially infect IL-4-induced Th2-type cultures. The V3 loop in gp120 was shown to be the principal determinant for their efficient replication.

Although an early loss of Th1-type cytokine (IL-2, IFN-γ, and IL-12) production and responsiveness after HIV-1 infection is observed (5, 36, 39, 44), there is debate as to whether this explains HIV-1 pathogenesis (24, 46). It was found that Th0 and Th2 cells were more efficiently killed than Th1 cells following infection with a T-tropic HIV-1 strain (35, 54). Based on these findings, it has been postulated that a strong dominance of Th1-type cytokines would be more protective against disease progression than a Th2-type cytokine response (13, 14). However, this idea may be an oversimplification of the situation that occurs in vivo. We recently found that the M-tropic HIV-1 strains can replicate and preferentially kill Th1-type bulk CD4+ T cells and clonal CD4+ T cells (52). M-tropic HIV-1 strains are isolated mainly from patients at early stages of the disease, while T-tropic HIV-1 strains appear at the late stages of the disease (4, 16, 21, 22, 29, 31, 37, 47, 48, 53, 55). It has been suggested that the switch of viral phenotype from M-tropic, non-syncytium-inducing (NSI) viruses to T-tropic, syncytium-inducing (SI) viruses may be relevant to the progression of the clinical condition. Thus, we assume that the two biologically distinct types of HIV-1 (M-tropic, NSI strains and T-tropic, SI strains) may have different roles in disease progression. M-tropic HIV-1 may first destroy the immune system and may change the immunological environment from Th1- to Th2-type immune responses. HIV-1 strains may be able to adapt to the new immunological environment by evolution of the V3 loop region.

Our results also showed that the preferences of M-tropic and T-tropic HIV-1 strains for IL-12-induced Th1- and IL-4-induced Th2-type conditions were mutually exclusive. M-tropic HIV-1 strains did not replicate efficiently in the Th2-type cultures prepared in the present study. We previously observed that M-tropic HIV-1 strains could replicate in IL-4-stimulated CD4+ Th2-type cultures to levels similar to those of T-tropic strains (52). This discrepancy may be due to two modifications of our procedures for the preparation and maintenance of Th2-type cultures: (i) the Th2-type cultures were prepared from a CD45RA+ naive CD4+-T-cell population, while Th2-type cultures were prepared from bulk naive and memory CD4+ T cells in other studies (52), and (ii) the Th2-type cultures were maintained with continuous exogenous addition of IL-4 both before and after HIV-1 infection. The present method was superior to the previous one in that it allowed the preparation and maintenance of high levels of IFN-γ- or IL-4-producing T cells (Fig. 1). However, a few reports have demonstrated effective replication of HIV-1 in Th1- or Th2-type cells (23, 38), and Mikovits et al. recently reported no difference in the susceptibilities of Th1 or Th2 clone cells to HIV-1 (40). In our present study, we did not test antigen-specific bulk or clonal CD4+ Th2 cells with regard to M-tropic HIV-1 susceptibility. It is possible that anti-CD3-stimulated naive CD4+ T cells might alternatively produce high levels of anti-M-tropic HIV-1 factors such as β-chemokines in the presence of IL-2 and IL-4.

Our present studies indicate that both viral and cellular factors contribute to the IL-12-induced Th1- and IL-4-induced Th2-type culture preferences of HIV-1 strains. Infection experiments using chimeric HIV-1 showed that the env region, and specifically the V3 loop region, was a critical viral determinant for these preferences. The V3 loop region is also a principal domain that determines M-tropism and T-tropism of HIV-1 (8, 10, 15, 25, 50). These tropisms result from differential usage of the chemokine receptors as HIV-1 coreceptors (3, 11, 17, 19). M-tropic strains and T-tropic strains use as coreceptors mainly the chemokine receptors CCR5 and CXCR4, respectively (6). A slightly higher CCR5 expression was observed in IL-12-induced Th1-type cultures than in IL-4-induced Th2-type cultures, consistent with recent reports (7, 33). In contrast, CXCR4 expression was slightly higher in IL-4-induced Th2-type cultures than in Th1-type cultures, as also recently reported (28). Thus, these differences in CCR5 or CXCR4 expression between Th1 and Th2 cells might partially explain the extent of HIV-1 replication in our present study. Low-level viral replication with T-tropic strains was observed in IL-12-induced Th1-type cultures, whereas no M-tropic strains could efficiently replicate in IL-4-induced Th2-type cultures. Furthermore, a high rate of syncytium formation in IL-4-induced Th2-type culture cells cocultured with T-tropic Env-expressing cells showed that high levels of CXCR4 expression were associated with preferential infection of IL-4-induced Th2-type cultures with T-tropic HIV-1 strains. On the other hand, weak syncytium formation was observed in IL-12-induced Th1-type culture cells cocultured with M-tropic Env-expressing cells. A previous study reported that M-tropic, NSI HIV-1 strains were able to mediate cell-cell fusion between limited numbers of cells but were unable to form apparent syncytia (56). Northern hybridization analysis showed lower levels of CCR5 mRNA expression than of CXCR4 expression in both IL-12-induced Th1- and IL-4-induced Th2-type cultures (data not shown). Thus, the lower level of fusion between cells expressing M-tropic Env and CCR5 may be due to these reasons. However, it is possible that another factor(s) apart from differential expression of coreceptors may contribute to the effective infection of M-tropic HIV-1 strains in IL-12-induced Th1-type culture cells, because coreceptor expression by this culture is not exclusively of one type.

In conclusion, this is the first report to suggest that cytokine-induced CD4+-T-cell differentiation to Th1 or Th2 cells is one of the factors responsible for inducing the switch of viral phenotype from M-tropic, NSI viruses to T-tropic, SI viruses.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Y. Ichihashi for providing anti-vaccinia virus MAb. We are also grateful to William R. Ampofo for correcting the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Public Health and Welfare and the Ministry of Biotechnology and Science in Japan. Y.K., Y.T., and N.Y. were sponsored by the Japan Health Sciences Foundation. N.Y. and Y.T. were also supported by Priority Areas from the Ministry of Education, Sports and Culture and by CREST (Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology) of Japan Science and Technology Corporation (JST). N.Y. was also supported by the Program for Promotion of Fundamental Studies in Health Sciences of the Organization for Drug ADR Relief, R&D Promotion and Product Review of Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbas A K, Murphy K M, Sher A. Functional diversity of helper T lymphocytes. Nature (London) 1996;383:787–793. doi: 10.1038/383787a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adachi A, Gendelman H E, Koenig S, Folks T, Willey R, Rabson A, Martin M A. Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. J Virol. 1986;59:284–291. doi: 10.1128/jvi.59.2.284-291.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alkhatib G, Combadiere C, Broder C C, Feng Y, Kennedy P E, Murphy P M, Berger E A. CC CKR5: a RANTES, MIP-1α, MIP-1β receptor as a fusion cofactor for macrophage-tropic HIV-1. Science. 1996;272:1955–1958. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asjö B, Albert J, Karlsson A, Morfeldt-Manson L, Biberfeld G, Lidman K, Fenyö E M. Replicative properties of human immunodeficiency virus from patients with varying severity of HIV infection. Lancet. 1986;ii:660–662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barcellini W, Rizzardi G P, Borghi M O, Fain C, Lazzarin A, Meroni P L. TH1 and TH2 cytokine production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells from HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 1994;8:757–762. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199406000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bates P. Chemokine receptors and HIV-1: an attractive pair? Cell. 1996;86:1–3. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonecchi R, Bianchi G, Bordignon P P, D’Ambrosio D, Lang R, Borsatti A, Sozzani S, Allavenia P, Gray P A, Mantovani A, Sinigaglia F. Differential expression of chemokine receptors and chemotatic responsiveness of type 1 T helper cells (Th1s) and Th2s. J Exp Med. 1998;187:129–134. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.1.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cann A J, Churcher M J, Boyd M, O’Brien W, Zhao J Q, Zack J, Chen I S Y. The region of the envelope gene of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 responsible for determination of cell tropism. J Virol. 1992;66:305–309. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.1.305-309.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng-Mayer C, Seto D, Tateno M, Levy J A. Biologic features of HIV-1 that correlate with virulence in the host. Science. 1988;240:80–82. doi: 10.1126/science.2832945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chesebro B, Nishio J, Perryman S, Cann A, O’Brien W, Chen I S Y, Wehrly K. Identification of human immunodeficiency virus envelope gene sequences influencing viral entry into CD4-positive HeLa cells, T-leukemia cells, and macrophages. J Virol. 1991;65:5782–5789. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.5782-5789.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choe H, Farzan M, Sun Y, Sullivan N, Rollins B, Ponath P D, Wu L, Mackay C R, LaRosa G, Newman W, Gerard N, Gerard C, Sodroski J. The β-chemokine receptors CCR3 and CCR5 facilitate infection by primary HIV-1 isolates. Cell. 1996;85:1135–1148. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clerici M, Hakim F T, Venzon D J, Blatt S, Hendrix C W, Wynn T A, Shearer G M. Changes in interleukin-2 and interleukin-4 production in asymptomatic, human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive individuals. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:759–765. doi: 10.1172/JCI116294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clerici M, Shearer G M. A TH1-TH2 switch is a critical step in the etiology of HIV infection. Immunol Today. 1993;14:107–111. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90208-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clerici M, Shearer G M. The Th1-Th2 hypothesis of HIV infection: new insights. Immunol Today. 1994;15:575–581. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cocchi F, DeVico A L, Garzino-Demo A, Cara A, Gallo R C, Lusso P. The V3 domain of the HIV-1 gp120 envelope glycoprotein is critical for chemokine-mediated blockade of infection. Nat Med. 1996;2:1244–1247. doi: 10.1038/nm1196-1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daar E S, Chernyavskiy T, Ahao J Q, Krogstad P, Chen I S Y, Zack J A. Sequential determination of viral load and phenotype in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1995;11:3–9. doi: 10.1089/aid.1995.11.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deng H, Liu R, Ellmeier W, Choe S, Unutmaz D, Burkhart M, Di Marzio P, Marmon S, Sutton R E, Hill C M, Davis C B, Peiper S C, Schall T J, Littman D R, Landau N R. Identification of a major co-receptor for primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature (London) 1996;381:661–666. doi: 10.1038/381661a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doranz B J, Grovit-Ferbas K, Sharron M P, Mao S, Goetz M B, Daar E S, Doms R W, O’Brien W A. A small-molecule inhibitor directed against the chemokine receptor CXCR4 prevents its use as an HIV-1 co-receptor. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1395–1400. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.8.1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dragic T, Litwin V, Allaway G P, Martin S R, Huang Y, Nagashima K A, Cayanan C, Maddon P J, Koup R A, Moore J P, Paxton W A. HIV-1 entry into CD4+ cells is mediated by the chemokine receptor CC-CKR-5. Nature (London) 1996;381:667–673. doi: 10.1038/381667a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Endres M J, Clapham P R, Marsh M, Ahuja M, Turner J D, McKnight A, Thomas J F, Stoebenau-Haggarty B, Choe S, Vance P J, Wells T N, Power C A, Sutterwala S S, Doms R W, Landau N R, Hoxie J A. CD4-independent infection by HIV-2 is mediated by fusin/CXCR4. Cell. 1996;87:745–756. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81393-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Evans L A, McHugh T M, Stites D P, Levy J A. Differential ability of human immunodeficiency virus isolates to productively infect human cells. J Immunol. 1987;138:3415–3418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fenyö E M, Morfeldt-Msonä L, Chiodi F, Lind B, von Gegerfelt A, Albert J, Olausson E, Åsjö B. Distinct replicative and cytopathic characteristics of human immunodeficiency virus isolates. J Virol. 1988;62:4414–4419. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.11.4414-4419.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foli A, Saville M W, Baseler M W, Yarchoan R. Effects of the Th1 and Th2 stimulatory cytokines interleukin-12 and interleukin-4 on human immunodeficiency virus replication. Blood. 1995;85:2114–2123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graziosi C, Pantaleo G, Gantt K R, Fortin J P, Demarest J F, Cohen O J, Sekaly R P, Fauci A S. Lack of evidence for the dichotomy of TH1 and TH2 predominance in HIV-infected individuals. Science. 1994;265:248–252. doi: 10.1126/science.8023143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hwang S S, Boyle T J, Lyerly H K, Cullen B R. Identification of envelope V3 loop as the major determinant of CD4 neutralization sensitivity of HIV-1. Science. 1992;257:535–537. doi: 10.1126/science.1636088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ichihashi Y, Takahashi T, Oie M. Identification of a vaccinia virus penetration protein. Virology. 1994;202:834–843. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jin N Y, Funahashi S, Shida H. Constructions of vaccinia virus A-type inclusion body protein, tandemly repeated mutant 7.5 kDa protein, and hemagglutinin gene promoters support high levels of expression. Arch Virol. 1994;138:315–330. doi: 10.1007/BF01379134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jourdan P, Abbal C, Nora N, Hori T, Uchiyama T, Vendrell J, Bousquet J, Taylor N, Pene J, Yssel H. IL-4 induces functional cell-surface expression of CXCR4 on human T cells. J Immunol. 1998;160:4153–4157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karlsson A, Parsmyr K, Sandström E, Fenyö E M, Albert J. MT-2 cell tropism as prognostic marker for disease progression in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:364–370. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.2.364-370.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawano Y, Tanaka Y, Misawa N, Tanaka R, Kira J, Kimura T, Fukushi M, Sano K, Goto T, Nakai M, Kobayashi T, Yamamoto N, Koyanagi Y. Mutational analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) accessory genes: requirement of a site in the nef gene for HIV-1 replication in activated CD4+ T cells in vitro and in vivo. J Virol. 1997;71:8456–8466. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8456-8466.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koot M, Keet I P, Vos A H, de Goede R E, Roos M T, Coutinho R A, Miedema F, Schellekens P T, Tersmette M. Prognostic value of HIV-1 syncytium-inducing phenotype for rate of CD4+ cell depletion and progression to AIDS. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118:681–688. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-9-199305010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koyanagi Y, Miles S, Mitsuyasu R T, Merrill J E, Vinters H V, Chen I S Y. Dual infection of the central nervous system by AIDS viruses with distinct cellular tropisms. Science. 1987;236:819–822. doi: 10.1126/science.3646751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loetscher P, Uguccioni M, Bordoli L, Baggiolini M, Moser B, Chizzolini C, Dayer J. CCR5 is characteristic of Th1 lymphocytes. Nature (London) 1998;391:344–345. doi: 10.1038/34814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maggi E, Macchia D, Parronchi P, Mazzetti M, Ravina A, Milo D, Romagnani S. Reduced production of interleukin 2 and interferon-gamma and enhanced helper activity for IgG synthesis by cloned CD4+ T cells from patients with AIDS. Eur J Immunol. 1987;17:1685–1690. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830171202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maggi E, Mazzetti M, Ravina A, Annunziato F, de Carli M, Piccinni M P, Manetti R, Carbonari M, Pesce A M, del Prete G, Romagnani S. Ability of HIV to promote a TH1 to TH0 shift and to replicate preferentially in TH2 and TH0 cells. Science. 1994;265:244–248. doi: 10.1126/science.8023142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maggi E, Giudizi M G, Biagiotti R, Annunziato F, Manetti R, Piccinni M P, Parronchi P, Sampognaro S, Giannarini L, Zuccati G, Romagnani S. Th2-like CD8+ T cells showing B cell helper function and reduced cytolytic activity in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Exp Med. 1994;180:489–495. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.2.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mammano F, Salvatori F, Ometto L, Panozzo M, Chieco-Bianchi L, De Rossi A. Relationship between the V3 loop and the phenotypes of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) isolates from children perinatally infected with HIV-1. J Virol. 1995;69:82–92. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.82-92.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meyaard L, Fouchier R, Brouwer M, Hovenkamp E, Miedema F. Syncytium-inducing HIV-1 replicate equally well in all types of T-helper cell clones. AIDS. 1996;10:1598–1600. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199611000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meyaard L, Hovenkamp E, Keet I P M, Hooibrink B, de Jong I H, Otto S A, Miedema F. Single-cell analysis of IL-4 and IFN-γ production by T cells from HIV-infected individuals: decreased IFN-γ in the presence of preserved IL-4 production. J Immunol. 1996;157:2712–2718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mikovits J A, Taub D D, Turcovski-Corrales S M, Ruscetti F W. Similar levels of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in human TH1 and TH2 clones. J Virol. 1998;72:5231–5238. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.5231-5238.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moriuchi H, Moriuchi M, Fauci A S. Cloning and analysis of the promoter region of CCR5, a co-receptor for HIV-1 entry. J Immunol. 1997;159:5441–5449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mosmann T R, Coffman R L. TH1 and TH2 cells: different patterns of lymphokine secretion lead to different functional properties. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989;7:145–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.07.040189.001045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mosmann T R, Sad S. The expanding universe of T-cell subsets: Th1, Th2 and more. Immunol Today. 1996;17:138–146. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)80606-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Navikas V, Link J, Wahren B, Persson C, Link H. Increased levels of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), IL-4 and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) mRNA expressing blood mononuclear cells in human HIV infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 1994;96:59–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06230.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O’Brien W A, Sumner-Smith M, Mao S H, Sadeghi S, Zhao J Q, Chen I S Y. Anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 activity of an oligocationic compound mediated via gp120 V3 interactions. J Virol. 1996;70:2825–2831. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.2825-2831.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Romagnani S, Maggi E, Del Prete G. An alternative view of the Th1/Th2 switch hypothesis in HIV infection. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1994;10:iii–ix. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.iii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schuitemaker H, Kootstra N A, de Goede R E, de Wolf F, Miedema F, Tersmette M. Monocytotropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) variants detectable in all stages of HIV-1 infection lack T-cell line tropism and syncytium-inducing ability in primary T-cell culture. J Virol. 1991;65:356–363. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.1.356-363.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schuitemaker H, Koot M, Kootstra N A, Dercksen M W, de Goede R E, van Steenwijk R P, Lange J M, Schattenkerk J K M E, Miedema F, Tersmette M. Biological phenotype of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 clones at different stages of infection: progression of disease is associated with a shift from monocytotropic to T-cell-tropic virus population. J Virol. 1992;66:1354–1360. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.3.1354-1360.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seder R A, Paul W E. Acquisition of lymphokine-producing phenotype by CD4+ T cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 1994;12:635–673. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.12.040194.003223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shioda T, Levy J A, Cheng-Mayer C. Small amino acid changes in the V3 hypervariable region of gp120 can affect the T-cell-line and macrophage tropism of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:9434–9438. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.20.9434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Swain S L, Bradley L M, Croft M, Tonkonogy S, Atkins G, Weinberg A D, Duncan D D, Hedrick S M, Dutton R W, Huston G. Helper T-cell subsets: phenotype, function and the role of lymphokines in regulating their development. Immunol Rev. 1991;123:115–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1991.tb00608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tanaka Y, Koyanagi Y, Tanaka R, Kumazawa Y, Nishimura T, Yamamoto N. Productive and lytic infection of human CD4+ type 1 helper T cells with macrophage-tropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1997;71:465–470. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.465-470.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tersmette M, de Goede R E, Al B J, Winkel I N, Gruters R A, Cuypers H T M, Huisman H G, Miedema F. Differential syncytium-inducing capacity of human immunodeficiency virus isolates: frequent detection of syncytium-inducing isolates in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and AIDS-related complex. J Virol. 1988;62:2026–2032. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.6.2026-2032.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vyakarnam A, Matear P M, Martin S J, Wagstaff M. Th1 cells specific for HIV-1 gag p24 are less efficient than Th0 cells in supporting HIV replication, and inhibit virus replication in Th0 cells. Immunology. 1995;86:85–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang N, Zhu T, Ho D D. Sequence diversity of V1 and V2 domains of gp120 from human immunodeficiency virus type 1: lack of correlation with viral phenotype. J Virol. 1995;69:2708–2715. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2708-2715.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weiss C D, Barnett S W, Cacalano N, Killeen N, Littman D R, White J M. Studies of HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein-mediated fusion using a simple fluorescence assay. AIDS. 1996;10:241–246. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199603000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhu T, Mo H, Wang N, Nam D S, Cao Y, Koup R A, Ho D D. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of HIV-1 patients with primary infection. Science. 1993;261:1179–1181. doi: 10.1126/science.8356453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]