Abstract

Purpose

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) are the leading cause of death globally. The current model of care for high-income countries involves preventive medication and highly trained healthcare professionals, which is expensive and not transposable to low-income countries. An innovative, effective approach adapted to limited human, technical, and financial resources is required. Measures to reduce CVD risk factors, including diet, are proven to be effective. The survey “Scaling-up Packages of Interventions for Cardiovascular disease prevention in selected sites in Europe and Sub-Saharan Africa” aims to develop non-pharmacological cardiovascular prevention and control programs in primary care and community settings in high, middle, and low-income countries. This review aims to identify the existing, validated dietary interventions for primary CVD prevention from national and international clinical guidelines that can be implemented in primary care and communities.

Methods

A systematic review of CVD prevention guidelines was conducted between September 2017 and March 2023 using the Turning Research Into Practice medical database, the Guidelines International Network, and a purposive search. The ADAPTE procedure was followed. Two researchers independently conducted the searches and appraisals. Guidelines published after 01/01/2012 addressing non-pharmacological, dietary interventions for primary CVD prevention or CVD risk factor management, in the adult general population in primary care or in community settings were included and appraised using the Appraisal of Guidelines Research and Evaluation II score. Individual dietary recommendations and the studies supporting them were extracted. Then supporting data about each specific dietary intervention were extracted into a matrix.

Results

In total, 1375 guidelines were identified, of which 39 were included. From these, 383 recommendations, covering 10 CVD prevention themes were identified. From these recommendations, 165 studies for effective dietary interventions for CVD prevention were found. Among these, the DASH diet was the most effective on multiple CVD risk factors. Combining diet with other interventions such as exercise and smoking cessation increased efficacy. No guidelines provided detailed implementation strategies.

Conclusion

The DASH diet combined with other interventions was the most effective on an individual basis. However, expansion in the wider population seems difficult, without government support to implement regulations such as reducing salt content in processed food.

Trial Registration

Clinical Trials NCT03886064

Keywords: Heart diseases, Primary prevention, Diet, Primary health care, Population health management

Plain language summary

Heart disease is the leading cause of death around the world. Strategies to prevent heart disease in high-income countries rely on medications and the skills of highly trained healthcare professionals. However, this is expensive and unsuitable for low-income countries. Consequently, an innovative, effective approach, which can be adapted to countries with limited human, technical and financial resources is needed. A program called SPICES was developed to identify strategies other than medication to prevent and control heart disease. This program reviewed the evidence for smoking cessation, physical activity, and dietary strategies, which may be useful to prevent heart disease in communities with limited resources.

In this review, the investigators searched online databases to find clinical guidelines that recommended dietary strategies to manage heart disease worldwide. The information found from this search revealed that the DASH diet, inspired by the Mediterranean diet, helps with weight loss, and improves blood pressure and cholesterol levels making it the most effective diet for preventing heart disease. It is even more effective if it is combined with other strategies such as exercise, stopping smoking or reducing the amount of alcohol consumed. However, this works well for individuals but is difficult to expand to the wider population. Therefore, government support is needed to implement regulations such as reducing salt content in processed food.

Introduction

During the twenty-first Century, cardiovascular diseases (CVD) have become the leading global cause of death, resulting in 17.9 million deaths in 2019 [1]. In Europe, CVD costs are estimated at 169 billion Euros annually [2]. Furthermore, CVD death rates are higher in the lower socioeconomic levels between and within countries with three quarters of CVD deaths occurring in low-income countries [3].

The current model of care for high-income countries involves preventive medication and highly trained healthcare professionals but is becoming increasingly difficult to maintain due to high costs and is not transposable to low-income countries. An innovative, effective approach adapted to limited human, technical, and financial resources is required. Inspired by the progress made in HIV and AIDS treatment in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), the World Health Organization (WHO) created the ICCC Framework (Innovative Care for Chronic Conditions). This framework redirects the current health policies from being population-centered to patient-centered, involving patients, families, and communities [3].

CVD occurrence increases predictably with accumulating CVD risk factors. Measures to reduce modifiable CVD risk factors, including diet, are proven to be effective. For example, in the general population, it is estimated that reducing cholesterol by 10% could decrease CVD mortality by 20% [4] and adopting a Mediterranean diet could reduce cardiovascular event occurrence by 30% [5]. Furthermore, CVD prevention interventions such as policies promoting healthy eating, smoking cessation, and physical activity, are cost-effective on international and national levels. It has been estimated that their costs would not exceed 4% of current health expenditure in high-income countries and 1–2% in low-income countries [6]. Also, behavioral changes are cost-effective on an individual level [7].

Consequently, the “Scaling-up Packages of Interventions for Cardiovascular disease prevention in selected sites in Europe and Sub-Saharan Africa” (SPICES) study was developed to evaluate and implement a comprehensive non-pharmacological cardiovascular prevention and control program in primary care and community settings in high, middle, and low-income countries [8]. The study involved systematically reviewing systematic clinical practice guidelines for smoking cessation, physical activities, and diet to identify best practice recommendations for reducing CVD. The smoking cessation and physical activity reviews have been previously published [9].

This review aims to identify the existing, validated dietary interventions for primary cardiovascular prevention from national and international clinical practice guidelines including European Union Countries, the UK, and Sub–Saharan Africa that can be implemented in primary care and communities.

Material and methods

Information sources and search

A systematic review of CVD prevention guidelines was conducted at the beginning of the SPICES study between September 2017 and January 2018 using the TRIP (Turning Research Into Practice) medical database and the International Guidelines Library of the Guidelines International Network (G-I-N). Subsequently, an update was performed in March 2023 prior to publication to ensure all recent guidelines were included. Following the ADAPTE procedure, the PIPOH tool (Population, Intervention, Professional/Patient, Outcome, Healthcare setting) was used to define the database search queries [10]. Population was defined as a primary care general population, free from cardiovascular disease. The Interventions were those focusing on cardiovascular risk factors including diabetes, hypertension, smoking, sedentary lifestyle, unhealthy diet, excess weight, or obesity. Professionals/Patients were any healthcare professional working in primary care or lay people. The Outcomes were reduced morbidity or mortality. The Healthcare setting and context was primary care. Search queries were “cardiovascular disease prevention” and “cardiovasc* prevention OR risk* OR risico* OR risque*”.

Then, a purposive search for every national clinical guideline used in the SPICES countries was performed. Guidelines included the Haute Autorité de Santé for France, the Tijdschrift Huisarts and the Nederland Huisartsen Genootschap for Belgium, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for the United Kingdom, the European Society of Cardiology for European Countries for South Africa and the WHO for Uganda.

The review was reported following the 2020 PRISMA reporting guidelines.

Eligibility criteria

Guidelines were included if they addressed non-pharmacological, dietary interventions for primary CVD prevention or CVD risk factor management, in the adult general population in primary care or in community settings. At least one patient outcome measure used for CVD risk assessment, such as mortality and morbidity, had to be reported in the guidelines. They had to be published after 01/01/2012 and be the latest version for revised guidelines. Guidelines could be written in English, French or Dutch.

Guidelines were excluded if they focused solely on specific populations such as elderly people, infants, children, pregnant women, or people with cancer. Guidelines focusing on secondary or tertiary prevention or only addressing cardiovascular risk assessment, pharmacological or surgical interventions, or specific conditions (such as type 1 diabetes, familial hypercholesterolemia) were excluded as were guidelines published before 2012 as these were considered out-of-date. Guidelines with no free full text availability were excluded as the consortium felt that recommendations to healthcare professionals or stakeholders should be freely accessible.

Searches were independently conducted by two researchers with a merging of results at each step of the review. Discrepancies were resolved by the two researchers and the study scientific committee.

Guideline, recommendation, and study selection

Two data collection phases were performed. During the first phase, the two researchers independently selected the guidelines. In the second phase, guidelines were evaluated according to the “Appraisal of Guidelines Research and Evaluation II” (AGREE II) tool integrated in the ADAPTE procedure [10]. The AGREE II tool consists of 23 items arranged into six domains: scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigor of development, clarity of presentation, applicability, and editorial independence. The two researchers independently scored each guideline by domain. An overall assessment was then performed and ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). This score was independent from the other domain scores.

A scientific committee consisting of three members was created to select guidelines based on the overall assessment scores. If the overall assessment scores from both researchers were equal to or higher than 5 for a selected guideline, it was included in the review. The difference between the overall assessment scores could not exceed one. If the difference was greater than one, an overall assessment score was found by consensus between the two researchers and the scientific committee.

Once the guidelines were selected, they were inspected for specific recommendations for effective, dietary interventions for primary CVD prevention. Recommendations with an A or B level of evidence, or Class I or Strong and/or 1 + + ,1 + , 2 + + , 2 + for NICE grading (regardless of level of evidence) were included. If an effective dietary intervention for primary CVD prevention with a pragmatic implementation strategy was supported by a study, this study, regardless of date, was considered for inclusion in a final matrix. Study exclusion criteria included study population under 50, gender specific study, and the absence of a control group for individual interventions.

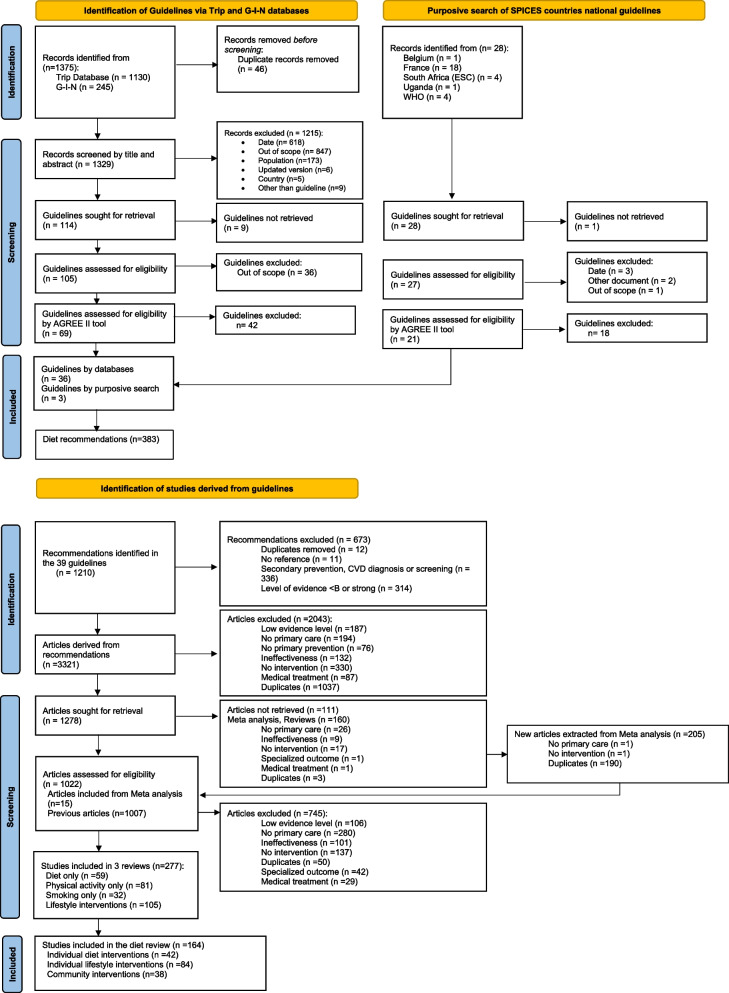

As the recommendations in the different guidelines frequently cited the same studies, a duplicate elimination process was performed. The complete selection process of guidelines, recommendations and studies is described in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Selection process of guidelines, recommendations, and studies

Data extraction and synthesis

For each included guideline, publication year or year of latest update, country, developing organization, language and title were extracted. From each included guideline a list of all dietary recommendations was created to provide an overview of relevant content. Recommendation themes were created inductively by grouping similar topic recommendations. The strength of recommendation, level of evidence, intervention description, outcomes, implementation strategies and evidence gaps were extracted from each recommendation if reported. The recommendations and studies they cited were then compiled into two matrices. After reading the full text, study title, implementation or intervention description, intervention frequency and duration, setting, material used, psychological model used where applicable, mass media use, and delivered intervention status were extracted into the matrices.

Results

A total of 39 primary CVD prevention guidelines were included (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Two guidelines were from the WHO and 37 were from high-income countries. None were by an organization from a middle- or low-income country.

Fig. 2.

Selection of primary CVD prevention guidelines, recommendations and studies

Table 1.

List of included guidelines addressing dietary interventions for primary CVD prevention

| GUIDELINE | AUTHOR | COUNTRY | YEAR | RATING SYSTEM (RS) | LINK TO EVIDENCE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: Screening for and management of obesity in adults | USPSTF | USA | 2012 | USPSTF | Body of evidence after a table of graded recommendations |

| Canadian Diabetes Association 2013 Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of diabetes in Canada | Canadian Diabetes Association | Canada | 2013 | GRADE | Major evidence cited in a specific paragraph before the recommendation box |

| 2013 AHA/ACC guidelines on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk | ACC/AHA) | USA | 2014 | ACC/AHA Classification of Recommendation/Level of Evidence (COR/LOE) construct | Table to link the general critical question (CQ) + specific evidence statement developed in the CQ |

| 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guidelines for the management of overweight and obesity in adults | ACC / AHA / TOS | USA | 2014 | ACC/AHA (COR/LOE) | Table to link the general CQ + specific evidence statement developed in the CQ |

| Team-based care and improvement of blood pressure control: recommendation of the Community Preventive Services Task Force | Community Preventive Services Task Force | USA | 2014 | No RS | References at the end of the article (no link) |

| Clinical practice guidelines for the management of overweight and obesity in adults, adolescents, and children in Australia | NHMRC | Australia | 2014 | NHMRC | Body of evidence after a table of graded recommendations |

| Lipid modification: cardiovascular risk assessment and the modification of blood lipids for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. CG181 | NICE | UK | 2014 | GRADE | Body of evidence first then recommendations |

| Behavior change: individual approaches (PH49) | NICE | UK | 2014 | No RS | Isolated body of evidence (specific chapter) |

| Cardiovascular disease prevention (PH25) | NICE | UK | 2014 | No RS | Isolated body of evidence (specific chapter) |

| Guidelines for the management of absolute cardiovascular disease risk | NVDPA | Australia | 2014 | NHMRC | Body of evidence after a table of graded recommendations |

| Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases. Guidelines for primary health care in low-resource settings | WHO | World | 2015 | GRADE | Body of evidence after each recommendation |

| Maintaining a healthy weight and preventing excess weight gain among adults and children | NICE | UK | 2015 | No RS | Isolated body of evidence (specific chapter) |

| Recommendations for prevention of weight gain and use of behavioral and pharmacological interventions to manage overweight and obesity in adults in primary care | Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care | Canada | 2015 | GRADE | Major evidence cited in a specific paragraph before the recommendation box |

| Sugars intake for adults and children | WHO | World | 2015 | GRADE | Body of evidence after each recommendation |

| Hypertension evidence-based nutrition practice guideline | ADA | USA | 2016 | Academy’s nutrition care process RS | Selected body of evidence after each recommendation |

| Guideline for the management of dyslipidemia for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in the adult | Canadian 2016 Lipids Panel Members | Canada | 2016 | GRADE | Body of evidence after each recommendation |

| Recommended Dietary Pattern to Achieve Adherence to the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology (AHA/ACC) Guidelines: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association | ACC/AHA | USA | 2016 |

ACC/AHA (COR/LOE) |

Main references throughout the text |

| The 2015 Dutch food-based dietary guidelines | Committee Dutch Dietary Guidelines | Netherlands | 2016 | No RS | Main references throughout the text |

| Risk estimation and the prevention of cardiovascular disease | SIGN | UK | 2017 | SIGN | Body of evidence first then recommendations |

| AACE/ACE Guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia and prevention of cardiovascular disease | AACE/ACE | USA | 2017 | AACE/ACE | Isolated body of evidence (specific chapter) |

| Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management (NG 136) | NICE | UK | 2019 | No RS | Isolated body of evidence (specific chapter) |

| ACC/AHA Guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease | ACC/AHA | USA | 2019 |

ACC/AHA (COR/LOE) |

Body of evidence after each recommendation |

| Updated Cardiovascular prevention guideline of the Brazilian society of cardiology | Brazilian Society of Cardiology | Brazil | 2019 | Brazilian Society of Cardiology RS | Main references throughout the text |

| Primary Prevention of ASCVD and T2DM in Patients at Metabolic Risk: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline | ADA/ European Endocrine Society | USA/Europe | 2019 | GRADE | Body of evidence after a table of graded recommendations |

| Innovation to Create a Healthy and Sustainable Food System: A Science Advisory from the American Heart Association | AHA | USA | 2019 | No RS | Main references throughout the text |

| ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk | ESC/EAS | Europe | 2020 | ESC RS | Main references throughout the text |

| Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk assessment & management | Qatari Ministry of Health | Qatar | 2020 | Qatari RS | Main references throughout the text |

| VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for screening and management of overweight and obesity | VA/DoD | USA | 2020 | GRADE | Body of evidence after each recommendation |

| VA/DoD clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of hypertension in the primary care setting | VA/DoD | USA | 2020 | GRADE | Body of evidence after each recommendation |

| VA/DoD clinical practice guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia for cardiovascular risk reduction | VA/DoD | USA | 2020 | GRADE | Body of evidence after each recommendation |

| Outil d'aide au repérage précoce et intervention brève: alcool, cannabis, tabac chez l'adulte | HAS | France | 2021 | No RS | Main references throughout the text |

| 2021 Dietary Guidance to Improve Cardiovascular Health: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association | USPSTF | USA | 2021 | USPSTF RS | Report of the systematic review dedicated to one recommendation |

| 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice | ESC | Europe | 2021 | ESC RS | Main references throughout the text |

| Behavioral Counseling Interventions to Promote a Healthy Diet and Physical Activity for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Adults Without Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement | USPSTF | USA | 2022 | USPSTF | Body of evidence after a table of graded recommendations |

| Obesity prevention (CG189) | NICE | UK | 2022 | No RS | Isolated body of evidence (specific chapter) |

| Comprehensive Management of Cardiovascular Risk Factors for Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association | AHA | USA | 2022 | No RS | Main references throughout the text |

| Standards of Care in Diabetes—2023 | ADA | USA | 2022 | ADA RS | Body of evidence after a table of graded recommendations |

| Vitamin, Mineral, and Multivitamin Supplementation to Prevent Cardiovascular Disease and Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement | USPSTF | USA | 2022 | USPSTF RS | Report of the systematic review dedicated to one recommendation |

| Preventing type 2 diabetes—population and community interventions (PH35) | NICE | UK | 2022 | No RS | Isolated body of evidence (specific chapter) |

ADA- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, ACC/AHA- American College of Cardiology / American Heart Association, NHMRC-National Health and Medical Research Council, NICE- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, NVDPA- National Vascular Disease Prevention Alliance, SIGN- Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network, TOS- The Obesity Society, USPSTF- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, VA/DoD- Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Defense, WHO- World Health Organization,

From the selected guidelines, 383 dietary recommendations were extracted. Recommendation ratings indicate comparability and quality. The Canadian Diabetes Association, Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Defense (VA/DoD), World Health Organization (WHO) and the collaboration between the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Endocrine Society used the independent GRADE rating system which is a current gold standard [11]. The other organizations used their own rating systems or other organization’s rating system. However, 11guidelines had no recommendation rating system, including six NICE guidelines. The body of evidence could be linked to the recommendations in 29 guidelines and could not in the other 10 (Table 1).

Among the 383 dietary recommendations extracted, ten major themes were identified (Table 2 and Table 3). Of these, only 17 recommendations recommended against current strategies (4.4%). Recommendations addressing soya, nuts, stanol esters and sterols were contradictory, with the same recommendation strength. Vitamin D, potassium, calcium, magnesium, vitamins A, B, C, E, and omega-3 fatty acids supplements were also controversial. For example, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics promoted magnesium, calcium, potassium, and vitamin D supplementation while the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network (SIGN) stated that the evidence did not support supplementation [12–14]. Only one guideline recommended that no alcohol should be consumed when 13 recommended only consuming small amounts [15].

Table 2.

Summary of diet and lifestyle recommendations

| Healthy diet and macronutrients (n = 133) | Micronutrients and supplements (n = 20) | Weight management (n = 43) | Alcohol reduction (n = 14) | Lifestyle interventions (n = 54) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommendations for |

Healthy diet characteristics by macronutrients: • Percentage of macronutrients (n = 2), • Increase in dietary fiber (n = 3) • Ideal macronutrients distribution (n = 2) • Low index carbohydrate diet (n = 3) • Polyunsaturated fatty acids and monounsaturated fatty acids (n = 2), • Reduce amounts of dietary cholesterol (n = 4) • Reduce calories from saturated fat (n = 11) • Reduce calories from trans-fat (n = 7) |

Reduce sodium intake (n = 8) | Maintain weight loss of 3 to 5% at least (n = 11) | Consume small amounts of alcohol (n = 13) | Integrate physical activity (n = 9) |

| Adopt Mediterranean dietary pattern (alternatively Nordic style diet (n = 2), vegetarian style diet) (n = 6) | Consume adequate amounts of dietary potassium (n = 2) | Diets for weight loss (n = 8) | Combine diet and physical activity (n = 17) | ||

| Adopt DASH (n = 5) | Consume adequate amounts of dietary calcium and eventually adopt supplementation (n = 1) | Promote a healthy weight (n = 5) | Promote smoking cessation (n = 9) | ||

| Variety of diets (n = 1) | Consume adequate amounts of dietary magnesium and eventually adopt supplementation (n = 1) | Promote weight loss (n = 10) | Develop multimodal interventions (n = 15) | ||

|

Healthy diet characteristics by type of food: •Fruits and vegetables (n = 12) •Grains and whole grains food (n = 12) •Legumes (n = 5) •Dairy products (n = 4) •Filtered coffee and tea (n = 3) •Nuts (n = 12) •Non tropical vegetable oils (n = 4) •Plant stanols or sterols (n = 1) •Consumption of fresh unprocessed food (n = 3) •Restrict refined carbohydrates and sweetened beverage (n = 11) •Reduce red meat and prefer fish, lean meats (n = 11) |

Use weight loss maintenance programs (n = 5) | Integrate psychosociological factors to CVD prevention (n = 4) | |||

| Use yeast rice nutraceuticals (n = 2) | Provide meal replacement for weight loss (n = 1) | ||||

| Use functional food enriched with phytosterols (n = 2) | |||||

| Space carbohydrates between meals for glyceamic control of diabetics (n = 1) | |||||

| Recommendations against | No evidence to support a soya intake recommendation (n = 2) | No evidence to recommend consumption of vitamine D to improve blood pressure (n = 1) | Do not use routinely very-low calorie diets (n = 2) | Do not drink alcohol (n = 1) | |

| No evidence to support nuts intake recommendation (n = 1) | No evidence to recommend whether reducing sodium intake plus changing dietary intake of potassium, calcium, or magnesium on blood pression control (n = 1) | Do not use unduly restrictive and nutritionally unbalanced diets (n = 1) | |||

| No evidence of safety of consumption of stanol esters and plant sterols on the long term (n = 1) | No evidence to recommend supplementation of Vitamins A,B,C, E (n = 4) |

Table 3.

Summary of diet and lifestyle implementation recommendations

| Professionnals involved (n = 9) | Customization of intervention for individuals (n = 63) | Healthy family behaviours (n = 3) | Theoretical models (n = 25) | Public policies (n = 19) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommendations for | Type of professionnals involved (n = 4) | Adapt diet adaptation to patient's preference and conditions (n = 8) | Encourage healthy family behaviours (n = 3) | Behavioral change models and their implementation (n = 19) | Develop legislative measures (n = 4) |

| Involve professionnals with specific expertise in nutrition (n = 3) | Involve person's partner or spouse (n = 1) | Shared decision model (n = 2) | Use Labelling and information on food items (n = 2) | ||

| Ensure the muldisciplinary team is regularly trained and competent (n = 2) | Use comprehensive lifestyle programs (n = 19) | Match behavioral change to individual needs (n = 2) | Use economic incentives (n = 1) | ||

| Intensity of lifestyle program (n = 6) | Use brief advice for alcohol reduction (n = 2) | Develop school educational campaigns (n = 1) | |||

| Use telehealth and electronic weight-loss programs (n = 10) | Develop workplace interventions (n = 1) | ||||

| Use commercial weight-loss programs (n = 2) | Regulate fast-foods in community settings (n = 2) | ||||

| Characteristics of weight loss maintenance programs (n = 5) | Develop policies adressed to alcohol (n = 2) | ||||

| Gradual physical activity and diet improvement (n = 2) | Involve food manufacturers (n = 2) | ||||

| Diabetes care organizational model (n = 2) | Adress financial issues for healty diet (n = 1) | ||||

| Individualize self-management (n = 3) | Implement behavioural change in nutritional strategies (n = 1) | ||||

| Use community setting programs (n = 2) |

Within the non-pharmacological recommendations, 1210 studies were identified, of which 164 were included in the diet study matrix (Table 4). Among these studies, 42 investigated dietary interventions targeting individuals, 84 investigated lifestyle interventions targeting individuals, and 38 involved communities in CVD prevention using dietary interventions. All but two of the 164 studies, used a CVD prevention surrogate endpoint [16, 17]. The mean publication dates were 1999 for dietary interventions, 2004 for lifestyle interventions and 1994 for studies involving communities. Only nine studies involving communities were randomized controlled trials. The selection criteria for this category was therefore lowered to cohort studies to include the other 29 studies.

Table 4.

Matrix of dietary interventions

| Date of publication | Name of Reference | POPULATION | CONTEXT | Description of Strategy | Outcome | Outcome | Professionnal | Intervention type | Diet type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1982 | Beard TC, Gray WR, Cooke HM, Barge R. Randomised controlled trial of a no-added-sodium diet for mild hypertension. Lancet 1982;2(8296):455–8 | 90 patients with anti hypertensive medication | Community | A shopping guide and address list for obtaining unsalted foods, including unsalted wholemeal bread and cakes made with potassium baking-powder, and unsalted restaurant meals. For 4 weeks they attended weekly 2 h small-group discussions at which slides were shown, recipes exchanged. Patients received the Australian dietary guidelines to eat less fat and sugar, more cereals and breads (preferably whole meal), and more fruits and vegetables -but were asked not to diet for weight reduction during the trial period | blood pressure | After coming to a mean sodium excretion rate of 35 mmol/24 h, the diet group finished with a lower mean SBP and DBP than the control group, and on about half the medication | ? | Educational |

The natural sodium content of a balanced diet was described as rather generous but safe. Milk (Na 21–28 mmol/1) was rationed and edible seaweed (kelp) prohibited. Patients received the Australian dietary guidelines to eat less fat and sugar, more cereals and breads (preferably wholemeal), and more fruits and vegetables -but were asked not to diet for weight reduction during the trial period.Australian dietary guidelines: more vegetables and fruit, particularly green, orange and red vegetables, such as broccoli, carrots, capsicum and sweet potatoes, and leafy vegetables like spinach, and legumes/beans like lentils. Grain (cereal) foods, particularly wholegrain cereals like wholemeal breads, wholegrain/high breakfast cereals, oats, wholegrain rice and pasta. Reduced fat milk, yoghurt and cheese varieties (reduced fat milks are not suitable for children under the age of 2 years as a main milk drink). Lean meats and poultry, fish, eggs, nuts and seeds and legumes/beans (except many Australian men would benefit from eating less red meat). Water instead of soft drinks, cordials, energy drinks, sports drinks and sweetened fruit juices and/or alcoholic drinks Most Australians need to eat less: Meat pies, sausage rolls and fried hot chips, Potato crisps, savoury snacks, biscuits and crackers Processed meats like salami, bacon and sausages Cakes, muffins, sweet biscuits and muesli bars Confectionary (lollies) and chocolate Ice-cream and desserts, Cream and butter, Jam and honey, Soft drinks, cordial, energy drinks and sports drinks Wine, beer and spirits |

| 1985 | MacMahon SW, Macdonald GJ, Bernstein L, Andrews G, Blacket RB. Comparison of weight reduction with metoprolol in treatment of hypertension in young overweight patients. Lancet. 1985; 8840: 1233–1236 | 42 men and 14 women, aged 20–55 years; supine diastolic blood pressure (phase V) 90–109 mm Hg, BMI greater than 26; no antihypertensive treatment | Community | In the weight reduction group, patients received an individually tailored dietary programme aimed at reducing caloric intake by 1000 cal per day, with protein, fat, and carbohydrate providing 15, 30, and 55% of calories, respectively. 7-day food logs were recorded in week 4 of the baseline and week 16 of the follow-up periods. Patients in the beta-blocker group were given metoprolol 100 mg twice a day. Patients in the placebo group were given one "metoprolol" placebo tablet twice a day. Subjects in all groups were seen individually every 3 weeks over 21 weeks (weeks 5 to 25) | blood pressure | Considering the weight-loss group, the fall in their systolic pressure of 13 mm Hg was significantly greater than that in the placebo group (7 mm Hg) but not different from that in the metoprolol group (10 mm Hg). Their fall in diastolic pressure (10 mm Hg) was greater than that in both the metoprolol (6 mm Hg) and placebo (3 mm Hg) groups | ? | ? | Weight loss diet type: an individually tailored dietary programme aimed at reducing caloric intake by 1000 cal per day, with protein, fat, and carbohydrate providing 15, 30, and 55% of calories, respectively |

| 1985 | Langford HG, Blaufox MD, Oberman A et al. Dietary therapy slows the return of hypertension after stopping prolonged medication. JAMA 1985;253 (5) 657- 664 | 584 patients | hypertensive population—primary prevention | The patients were seen at two-week intervals for 16 weeks and at monthly intervals thereafter, unless diastolic BP was 95 mmHg or higher, a development that required scheduling of weekly visits. Two types of dietary intervention groups were established: * The goal for one group was to decrease sodium intake to 70 mEq/day (4 g) and increase potassium intake to 100 mEq/day while maintaining body weight. * The goal for the second group was to reduce body weight Weight loss was achieved primarily by reducing caloric consumption, with relatively little emphasis on changing exercise. Nutritional intervention consisted of eight initial consecutive weekly group sessions, then monthly sessions thereafter plus individual consultation as needed | Decrease of hypertensive medication | At 56 weeks, randomization either to weight-loss group (mean loss of 4.5 kg [10 lb]) or to sodium-restriction group (mean reduction of 40 mEq/day) increased the likelihood of remaining without drug therapy, with an adjusted odds ratio of 2.17 for the sodium group and 3.43 for the weight group | ? | decrease sodium intake OR reduce body weight by reducing calories | ? |

| 1986 | Chalmers J, Morgan T, Doyle A. et al. Australian National Health and Medical Research Council dietary salt study in mild hypertension. J Hypertens 1986:4(suppl 6):S629-37 | 212 untreated subject with mild hypertension (DBP 90–100 mmHG) | Deit counseling, following 3 day of dietary intake record. 3 groups, no siginificant difference between them. Every 15 days, by dietitian and nurses. 12 weeks intervention.. Avoid adding salt. Eat extra fruits and vegetables. Drink fruit juices. Eat high potassium breakfast | blodd pressure | Two-hundred subjects completed the diet phase of 12 weeks. The falls in systolic and diastolic blood pressures (mmHg) in the diet phase were 7.7 ± 1.1 and 4.7 ± 0.7 (B), 8.9 ± 1.0 and 5.8 ± 0.6 (C) and 7.9 ± 0.9 and 4.2 ± 0.7 (D). These falls were all greater than those in the control group on an intention-to-treat analysis (P less than 0.005) but did not differ from each other | Dietician |

Diet counseling 4 groups: - normal (control) - low sodium - low sodium /high potassium - high potassium |

Diet counseling 4 groups: - normal (control) - low sodium - low sodium /high potassium - high potassium |

|

| 1986 | Baron JA, Schori A, Crow B, Carter R, Mann JI. A randomized controlled trial of low carbohydrate and low fat/high fiber diets for weight loss. Am J Public Health 1986; 76: 1293–1296 | 135 overweight subjects | One hundred thirty-five overweight subjects were recruited into the study with the help of six diet clubs and employee groups from the Oxford (United Kingdom) area | A commercial low-carbohydrate diet versus a commercial low-fat/high fiber diet. Spouses were randomized together. Each subject planned his/her own menus, with the assistance of the group leaders and the study investigators. Thus the dietary advice was in a form typical of that in currently used popular diets. Both diet regimens featured diet instruction sheets with the same format; therefore they were virtually identical in materials and procedures, although they differed substantially in content. At each center, participating subjects were given a general orientation to dieting. This included a brief discussion of behavioral techniques and the value of exercise, both of which were not specifically encouraged further. After instruction in the appropriate diet, each subject then participated in the normal operation of his or her group, which in all cases included weekly meetings. One of the study investigators visited each group regularly during the three-month diet period to offer encouragement and further instruction, if needed. Meanwhile, group leaders regularly weighed participants and avoided activities that might discourage or aid the weight loss of one study diet group compared to the other | weight loss | Dieters given low carbohydrate/low fiber dietary advice tended to lose more weight than those given a higher carbohydrate/higher fiber regimen (5.0 vs 3.7 kg on average at three months) | commercial diet programs leaders | commercial weekly group sessions | The two diet programs were both currently used commercially and had been designed for this popular use. Each focused on the restriction of one type of nutrient (carbohydrates or fat, depending on the diet). In each case, the diet was designed to be equivalent to 1,000–1,200 cal a day, although a few particularly active subjects were advised to liberalize the diet to 12 units (1,200- 1,400 cal) daily. The 10 carbohydrate units permitted a daily carbohydrate intake of at most 50 g (a less severe limitation than that imposed in low-carbohydrate ketogenic diets).'Similarly, the basic low fat diet restricted fat intake to at most 30 g a day. Each regimen had zero-unit foods that were not restricted directly. For the low-carbohydrate diet, these included meats and cheese; for the low-fat/high fiber diet, bread, potatoes, and fresh fruit. Increased intake of foods rich in fiber was specifically stressed to those in the low-fat group; this advice was not given to the low-carbohydrate dieters. Neither diet required a minimum of any food, although a half pint of milk per day was recommended to the low-carbohydrate dieters |

| 1986 | Croft PR, Brigg D, Smith S, Harrison CB, Branthwaite A, Collins MF. How useful is weight reduction in the management of hypertension? J R Coll Gen Pract. 1986; 36: 445–448 | 110 participants with hypertension | GP office | The patients attending the clinic were given active dietary advice for weight reduction by two dietitians working at the surgery. The groups were given identical advice, but the importance of weight reduction for blood pressure control was emphasized to the hypertensive patients. The hypertensive patients who did not attend the weight reduction clinic were seen only by the general practitioner. They were told that for six months their blood pressure would be checked periodically before any decision about specific treatment was taken. If patients in this group indicated that they intended to lose weight, they were not discouraged but were given no specific advice or diet sheets. Their plan to lose weight was recorded. All three groups of patients were given advice about modest restriction of salt use and reduction of excessive alcohol intake. No advice was given about smoking or exercise | weight loss | The weight loss achieved by obese hypertensive patients randomly allocated to a weight reduction programme in general practice was associated with significant reductions in both systolic and diastolic blood pressure when compared with a control group of obese hypertensive patients who were not dieting. The mean weight loss during the six months of the study was 6.5 kg for all the dieting hypertensive patients (a significant change) and 0.2 kg for the non-dieting hypertensive patients (a non-significant change) | 2 dieticians | dietary advice | active dietary advice for weight reduction by two dietitians working at the surgery |

| 1988 | Wallace P, Cutler S, Haines A. Randomised controlled trial of general practitioner intervention in patients with excessive alcohol consumption. BMJ 1988; 297: 663–8 | 909 patients having drinking above the limits set for study and had not received advice | Medical Research Council's general practice research framework, mostly in rural or small urban settings | Patients randomised to the treatment group were contacted by their general practitioner and asked to attend for a brief interview. All general practitioners received a training session with use of a specially recorded video programme to illustrate the elements of the intervention. After an assessment interview about the pattern and amount of alcohol consumption and evidence of alcohol related problems and dependence (obtained by using the brief Edinburgh alcohol dependence scale2') patients were shown a histogram based on figures from a national survey of drinking habits to illustrate how their weekly consumption compared with that of the general population. Advice was given about the potential harmful effects of their current level of alcohol consumption, backed with the information booklet That's the Limit. Men were advised to drink not more than 18 U/week and women not more than 9 U/week. Where there was evidence of dependence on alcohol general practitioners were encouraged to advise abstinence. Patients were given a drinking diary, the front cover of which was a facsimile of an EClO prescription with the words "Cut Down on your Drinking!" The last page contained a guide to the alcohol content of a range of drinks. An initial follow up appointment one month later was offered to all patients; subsequent appointments at four, seven, and 10 months were at the discretion of the general practitioner. During these sessions the patient's drinking diary was reviewed and feedback given on the results of blood tests indicating evidence of damage due to alcohol | alcohol consumption | At one year a mean reduction in consumption of alcohol of 18.2 (SE 1.5) U/week had occurred in treated men compared with a reduction of 8.1 (1.6) U/week in controls (p less than 0.001) The proportion of men with excessive consumption at interview had dropped by 43.7% in the treatment group compared with 25.5% in controls (p less than 0.001). A mean reduction in weekly consumption of 11.5 (1.6) U occurred in treated women compared with 6.3 (2.0) U in controls (p less than 0.05), with proportionate reductions of excessive drinkers in treatment and control groups of 47.7% and 29.2% respectively | general practitioner (who had had a training session) | Brief intervention providing advice and information about how to reduce consumption + a drinking diary | no |

| 1988 | Weinberger MH, Cohen SJ, Miller JZ, Luft FC, Grim CE, Fineberg NS. Dietary sodium restriction as adjunctive treatment of hypertension. JAMA. 1988;259(17):2561–2565 | 114 hypertensive patients. All but 18 of these patients were receiving antihypertensive drugs and had achieved adequate blood pressure control | written or oral interventiion, veteran administration hypertension clinic |

A food questionnaire designed to identify the individual's usual food preferences: the dietitians used the food preference questionnaires to review and identify sources of sodium in the usual diet and to provide alternatives that would permit reduction of dietary Dietary restriction lessons: held with both the patient and partner on three occasions Lessons 1 and 3 were conducted in the clinic and lesson 2 in the patient's home |

blood pressure | Significant falls in blood pressure and body weight were observed with no significant correlations noted between the two variables, implying independence of these effects | Dieticians | Three lessons based on alternatives to usual diet to permit salt reduction | reduced sodium diet based on usual diet |

| 1990 | Singh RB, Rastogi SS, Mehta PJ, Mody R, Garg V. Effect of diet and weight reduction in hypertension.Nutrition. 1990; 6: 297–302 | 416 hypertensive participants | ? | Weight reduction by a low-energy diet and a high-polyunsaturates-, fiber- and potassium-rich diet may be independently useful to hypertensives. Participants were randomized to either a low-energy cardiovasoprotective (CVP) diet, a low-energy usual diet, an optimal-energy CVP diet, or an optimal-energy, usual pre-experimental diet plus drug therapy in a single-blind and controlled fashion. Groups A and B received significant fewer calories per day than Groups C and D. Groups A and C also received significantly more calories per amount of complex carbohydrates, polyunsaturates, potassium, and magnesium than did Groups B and D. Dietary compliance and drug intake was checked weekly | Lipids | After 3 months, there was a significant fall in mean serum cholesterol (p less than 0.01) and mean serum triglycerides (p less than 0.05) in Group A compared with Group D. Group A and B patients had a loss of around 10 kg of mean body weight, with no weight change | ? | ? Dietary compliance and drug intake was checked weekly | a low-energy cardiovasoprotective (CVP) diet (Group A; n = 106), a low-energy usual diet (Group B; n = 104), an optimal-energy CVP diet (Group C; n = 104), or an optimal-energy, usual pre-experimental diet (Group D; n = 102) plus drug therap |

| 1990 | Campbell LV, Barth R, Gosper JK, Jupp JJ, Simons LA, Chisholm DJ. Impact of intensive educational approach to dietary change in NIDDM. Diabetes Care 1990;13(8):841–7 | 70 participants with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, suboptimal recent glycemic control, dietary fat intake ≥ 35% of total energy intake, and BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2, age of onset of diabetes > 30 yr, duration of diabetes > 3 mo, duration of current treatment > 1 mo, no education program attendance within the previous 6 mo,and English speaking, | primary care |

Diet education Multiprofessionnal behavioral individual,dietary compliance, dietary intake, total cholesterol level, glycemic control Dietary instruction was greatly simplified. Subjects were told to decrease all fats and to increase legumes. Calories restriction and carbohydrate portions (exchanges) were not discussed, and types of fat were not distinguished. INTERVENTION• dietary (13.5 h in length) • conducted over 11 wk (total 22 h). The educational approach was based on a practical application of the cognitive motivational theory by Heckhausen and Kuhl o First: establish adequate reasons for behavioral change, the physician describes the major diabetic complications, and each subject visualizes the individual adverse effects of such afflictions (variable, goal value). o help the patient through the steps that lead to action. the physician encourages good metabolic control via healthy diet to help prevent complications. The simplified diet is then demonstrated by the dietitian, and patients are encouraged to practice devising realistic diet plans, i.e., plans they feel able to achieve (variable, expectancy). o Explore the many favorable and unfavorable individual consequences of making dietary changes, losing weight, and reducing the risk of complications with the psychologist, e.g., social inconvenience, better appearance, added expense, flatulence, and improved health (variable, instrumentality). o Patients then declare in writing whether they intend to follow the diet. o If this is the case, they are assisted to set realistic and specific goals for individual changes and to develop coping strategies for forseeable crisis situations |

dietary compliance, dietary intake | The intensive approach was associated with significantly greater improvements in dietary compliance, dietary intake (complex carbohydrate, [P = 0.013], legumes [P less than 0.0001], fiber [P less than 0.0001], total fat [P less than 0.004], saturated fat [P less than 0.004]), and total cholesterol level (P = 0.007) | Multiprofessionnal team | cognitive motivational theory | simplified med diet, Subjects were told to decrease all fats and to increase legumes. Calories restriction and carbohydrate portions (exchanges) were not discussed, and types of fat were not distinguished |

| 1992 | Sciarrone SEG, Beilin LJ, Rouse IL, Rogers PB. A factorial study of salt restriction and a low-fat/high-fibre diet in hypertensive subjects. J Hypertens 1992;10:287–98 | 95 hypertensive subjects, mean age 53.5 years, consuming less than 30 ml ethanol/day were selected from community volunteers | community volunteers | Subjects followed either a low-sodium, low-fat/high-fibre diet (less than 60 mmol sodium/day; 30% fat energy; P:S ratio = 1; 30–50 g fibre/day) or a low-sodium, normal-fat/normal-fibre diet (less than 60 mmol sodium/day; 40% fat energy; P:S ratio = 0.3; 15 g fibre/day) for 8 weeks. Half of each group received 100 mmol/day NaCl and the remainder received placebo. Instructions:—no add salt to cooking, abstain from commercially prepared food, purchase "no salt variety " if available- low or no salt bread, butter and margarine,—avoid cheese, commercial cake, biscuits, chocolate- Avoid dining out. Provided with low sodium bread and no added salt butter. Low fat:—avoid frying- encouraged to consume 3 serving /day of vegetables 2/day of fruit- provided low salt whole meal bread bead, low salt margarine, and fruits | Blood pressure and lipids | Sodium restriction reduced blood pressure and did not raise low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. A low-fat/high-fibre diet did not reduce blood pressure but lowered cholesterol levels | ? | ? | Subjects followed either a low-sodium, low-fat/high-fibre diet (less than 60 mmol sodium/day; 30% fat energy; P:S ratio = 1; 30–50 g fibre/day) or a low-sodium, normal-fat/normal-fibre diet (less than 60 mmol sodium/day; 40% fat energy; P:S ratio = 0.3; 15 g fibre/day) for 8 weeks. Half of each group received 100 mmol/day NaC |

| 1992 | Anderson JW, Garrity TF, Wood CL, Whitis SE, Smith BM, Oeltgen A6PR. Prospective, randomised, controlled comparison of the effects of low- fat and low-fat plus high-fiber diets on serum lipid concentrations. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;56:887–894 | 340 caucasian individuals between 30 and 50 y of age, and between 80% and I 20% of ideal body weight by the Metropolitan tables | Public screening of individuals drawn from major employers, churches, and shopping centers in the Central Kentucky area occurred between March and October of 1987 |

• l0-wk, diet-education program EDUCATIONAL SEMINAR protocols for the two diet groups were also quite similar and one instructor conducted the seminars for both groups - Dietary goals would be approached through a process of gradual change in habitual diet practices o 1-h sessions in which a modest amount of new information was presented each week; participant discussion and questions were encouraged. o Participants in both groups ( 10/group) were strongly encouraged to attend meetings with a spouse or close friend. o Demonstrations and active problem solving were major vehicles for learning. o Emphasis was placed on practical rather than theoretical knowledge (recipe modification, shopping strategies, label reading, and healthful restaurant eating were topics of seminar sessions) o Dietary-fat reduction was stressed for both diet groups• Appropriate instructional materials: some prepared by project staff and some available from the AHA and the HCF Nutrition Research Foundation (8). After the seminar, each participant and partner met individually for 30 mm with a consulting dietitian assigned to them for the duration of the project. o They discussed individual dietary progress and problems of the past week, o They set achievable goals for the next week. • Participants were encouraged to call the dietitian during the week when problems and questions arose with regard to the diet regimen. • These dietitians also made home visits 4 times during the year at which further instruction and problem solving were accomplished, as well as data collection integral to the diet assessment. • Each dietitian was responsible for four participants, two each from the two diet groups. • When a participant missed a seminar session, the participant was asked to attend the same session when it was offered during the subsequent wave of the study or individually with the dietitian |

Lipids | The high-fiber group experienced a greater average reduction (13%) in serum cholesterol than did the low-fat (9%) and usual-diet (7%) groups. After adjustment for relevant covariates, the reduction in the high-fiber group was significantly greater than that in the low-fat group (P = 0.0482) | Instructor + consulting dietician | Educational seminar |

AHA diet: • 55% of energy from carbohydrate, 20% of energy from protein, 25% of energy from fat, and 200 mg dietary cholesterol/d • amount of dietary fiber recommended, namely = 15 g • Preplanned meal patterns tailored to meet each individual’s lifestyle, preferences, and habits - three servings each of fruits and vegetables;—four servings of bread or starch foods;—two low-fat dairy items;—198.45 g lean meat, poultry, or seafood;—no egg yolk;—and fat servings based on energy content HCF diet: • 55% of energy from carbohydrate, 20% of energy from protein, 25% of energy from fat, and 200 mg dietary cholesterol/d. • amount of dietary fiber recommended = 50 g at least one serving of beans and one serving of cereal chosen from the HCF exchange groups • The use of soluble-fiber rich cereals such as oat bran was encouraged |

| 1994 | Campbell, M.K., DeVellis, B.M., Strecher, V.J., Ammerman, A.S., DeVellis, R.F., Sandler, R.S. Improving dietary behavior (the effectiveness of tailored messages in primary care settings). Am J Public Health. 1994;84:783–787 | 558 adult patients (ages 18 and above) recruited from four family practices in central North Carolina between September and November 1991 | primary care, Two practices served a primarily urban population and two were primarily rural | The tailored intervention consisted of a one-time, mailed nutrition information packet tailored to the participant's stage of change, dietary intake, and psychosocial information. All tailored group members were mailed a packet containing a nutrition profile summarizing their current diet and level of interest in changing behavior, a tailored page regarding dietary fat intake, and a tailored page regarding fruit and vegetable intake. Each message acknowledged the participant's stage and addressed his or her beliefs about both susceptibility to diet-related diseases and perceived benefits of and motives for changing diet. Individualized diet feedback was then provided regarding baseline fat and fruit/vegetable intake. Contemplators received information designed to decrease barriers to change and to increase self-efficacy. Depending on stage of change, self-efficacy, and history of past relapse, participants also received tailored recipes and specific diet tips designed to promote skills and to provide cues to action. Those individuals who were already trying to change received tailored recipes and messages aimed at preventing relapse | Change of dietary habits | Tailored nutrition messages are effective in promoting dietary fat reduction for disease prevention | tailored mailed nutrition information | 1990 Dietary Guidelines for Americans | |

| 1996 | Siggaard R, Raben A, Astrup A. Weight loss during 12 weeks ad libitum carbohydrate-rich diet in overweight and normal weight subjects at a Danish working site. Obes Res 1996; 4:347 ± 356 | 86 normal-weight and overweight employees | Danish worksite | Before Intervention: 4-day dietary record based upon weighing. Weighed and instructed weekly in how to achieve and maintain an ad libitum carbohydrate- rich, low-fat diet. The instructions were a combination of lectures and written material. The material contained information on different topics related to nutrition, e.g. physiological mechanisms involved in appetite regulation and macronutrient balance, the macronutrient content of different food, the importance of carbohydrate-rich, low-fat snacks and how to read food labels. The dietary guideline contained carbohydrate-rich and low-fat recipes (8 recipes for breakfast, 12 for lunch, 6 for snacks and 55 for dinner). The subjects were encouraged to choose some of the recipes for their meals and were told that they could eat as much as they wished until satisfaction | Weight loss | a significant loss of body weight (4.2 ± 0.4 kg) and fat mass (4.4 ± 0.6 kg) was observed in I (p < 0.05 vs. C). The weight loss in I was not regained at 24 and 52 weeks' follow-up (82% of I participating) compared to baseline | ? | Lectures + written material |

The emphasis was placed on the consumption of natural high-carbohydrate foods such as whole grains, fruits, vegetables and low-fat dairy products, but there were no limitations as to the source of carbohydrate Patients were given a dietary guideline developed to increase the daily carbohydrate intake and decrease the daily fat intake. The guideline guaranteed a minimum intake of 7.0 to 8.0 MJ/d with carbohydrate amounting to 60 to 65 E%, protein to 15 to 20 E%, fat to 20 to 25 E% and dietary fiber to 4.9 to 6.2 glMJ |

| 1997 | Beresford, S.A., Curry, S.J., Kristal, A.R., Lazovich, D., Feng, Z., Wagner, E.H. A dietary intervention in primary care practice (the Eating Patterns Study). Am J Public Health. 1997;87:610–616 | 2111 patients of six primary care clinics | The intervention consisted of two components: a self-help booklet and physician endorsement. We developed the booklet, Help Yourself: a guide to healthful eating, on the basis of behavior change principes derived from the social learning theory, and the dietary recommendations of the National Research Council. We presented motivations for dietary change such as improving health, following the changing social norm to eat lower fat, higher fiber foods, and doing something positive for oneself. Current dietary behavior was assessed trough the use of a brief self test at the beginning of the book. We presented specific behaviors skills in an easy to follow format, beginning by identifying current behaviors and suggesting sequential changes in small, simple steps. No external goals were included: rather, individuals were encouraged to set their own goals | Change of dietary habits | Intervention and control groups both reported a decrease in fat intake and an increase in fiber intake. The differential change and 95% confidence interval (CI) for the percentage of energy obtained from fat was -1.2 (CI = -0.71, -1.7) (P = .0015), for grams fiber/1000 kcal 0.32 (CI = -0.066, 0.71) (P = .086), for fat score -0.044 (CI = -0.016, -0.072) (P = .010), and for fiber score 0.036 (CI = 0.011, 0.061) (P = .014) | book + physician | information | healthy eating | |

| 1997 | Glasgow RE, La Chance PA, Toobert DJ, Brown J, Hampson SE, Riddle MC. Long-term effects and costs of brief behavioural dietary intervention for patients with diabetes delivered from the medical office. Patient Educ Couns 1997; 32: 175–84 | 206 Diabetic patients > 40 yo, in primary care | Before: 4-day food record form and questionnaire. A 5–10 min touchscreen dietary barriers assessment (Barriers to dietary self-care are an expanded list of 30 questions adapted from the Barriers to SelfCare instrument that immediately generated two printed feedback forms:—for the patient—for the physician with information on four issues: 1. question the patient would most like to discuss at that visit (reported verbatim from patient statements) 2. the patient's dietary intake 3. summary of the key barriers 4. a visual analog scale indicating the patient's standing on: readiness to engage in dietary change, seriousness of diabetes, importance of diabetes, desire for participation in decisions. Then: Brief (20-min) patient centered goals, setting and problem solving, and to receive dietary self-help materials coordinated with the computer feedback, to lower fat intake. Patient with higher self-efficacy estimated level: home video adressing strategies for the most frequent type of barriers. Patient with lower self-efficacy estimated level: returned for 30 min individuaized video via a touch screen. Follow-up by phone at weeks 1, 3 and at 3 and 6 months: review, adjust strategies, discuss difficulties, give more material. Book "The Human Side of Diabetes" was given at 9 months | Change of dietary habits + Lipids | Brief Intervention produced significantly greater improvement than Usual Care on multiple measures of change in dietary behaviour (e.g., covariate adjusted difference of 2.2% of calories from fat; p = 0.023) and on serum cholesterol levels (covariate adjusted difference of 15 mg/dl; p = 0.002) at 12-month follow-up. There were also significant differences favouring intervention on patient satisfaction (p < 0.02) but not on HbA1c levels. The costs of intervention ($137 per patient) were modest relative to many commonly used practices | physician + follow-up by phone | 4-day food record and dietary validated questionnaire = book at 9 month | the Human side of diabetes | |

| 1997 | Keyserling, T.C., Ammerman, A.S., Davis, C.E., Mok, M.C., Garrett, J., Simpson, R.J. A randomized controlled trial of a physician-directed treatment program for low-income patients with high blood cholesterol (the Southeast Cholesterol Project). Arch Fam Med. 1997;6:135–145 | 372 low-income and minority patients with high cholesterol | Twenty-one community and rural health centers in North Carolina and Virginia |

3 major components paralleling the NCEP recommendations: (1) a clinician-directed dietary component using the Food for Heart Program (FFHP); (2) referral to a local dietitian if LDL-C remained elevated at 4-month follow-up (3) a prompt for the clinician to consider drug treatment based on the LDL-C at 7-month follow-up In addition, a quarterly reinforcement mailing with recipes and health tips was sent to all intervention patients after they returned for their 7-month blood test Food for Heart Program which consists of the following components: (1) The dietary risk assessment (DRA), a validated food-frequency instrument that identifies major sources of saturated fat and cholesterol in the diet (2) A color- and number-coded educational strategy that guides clinician counseling without requiring extensive knowledge of behavior-change theory or food composition (3) Easy-to-read, illustrated patient education materials that are culturally specific to the population served, promote interaction between patient and clinician, divide recommendations into small achievable steps, and offer practical assistance for dietary change (4) record goals and monitor patient progress Dietitian Referral If the LDL-C remained elevated at 4 months, participants were referred to a dietitian or health educator for a maximum of 3 counseling sessions, each lasting 30 min. They were trained to use the FFHP educational materials in greater depth and to supplement this program with other materials as appropriate. At the end of 3 counseling sessions, the dietitians or health educators completed a summary checklist that was mailed to the clinic and filed in the patient's FFHP folder. This checklist served as feedback to the clinician and as a guide for long-term monitoring and reinforcement at subsequent clinic visits Prompt for Use of Lipid-Lowering Medication The prompt consisted of a letter for the clinician and a drug treatment folder for the patient's chart. The folder included a quick overview of NCEP guidelines for initiating drug therapy, including medications of choice and their cost, detailed information on each class of lipid-lowering agents and a flow diagram illustrating how to use the agents, and simply written, single-page handouts for the patient describing the importance of each medication, getting started, increasing the dosage, coping with potential adverse effects, and other information designed to help maximize adherence to the medical regimen TRAINING: A nutritionist on the study staff trained intervention clinicians to use the FFHP during a 90-min tutorial that included a brief review of essential elements of a lipid lowering diet, dietary behavior-change strategies, use of the FFHP materials, and practice using the materials |

Lipids | Total cholesterol and LDL-C decreased more in the intervention group than in the control group. Overall, the difference in lipid reduction between groups was modest and of borderline statistical significance; among participants who did not take lipid-lowering medication during follow-up, the difference in lipid reduction between groups was larger | dietician | educational program lead by dietician | NCEP recommendations and FFHP educational material |

| 1997 | Roderick, P., Ruddock, V., Hunt, P., Miller, G. A randomized trial to evaluate the effectiveness of dietary advice by practice nurses in lowering diet-related coronary heart disease risk. Br J Gen Pract. 1997;47:7–12 | 956 participants aged 35–59 years, recruited opportunistically by their GPs | primary care |

Trained NURSES nurses were trained by a state registered dietician over a one-and-a-half-day period in diet and its relationship with coronary heart disease, how to use the nutritional tools (including interpretation of the food frequency questionnaire to assess dietary habits), and how to negotiate dietary changes with each patient Intervetion All: standard health education from the leaflets Guide to Healthy Eating, Giving up smoking, Look After Your Heart, Heart Disease, and Exercise, Why Bother? Intervention: o Negociating changes, food substitution (objectives: 5 changes), review of quantity/freqency food intake o Specially designed dietary sheets: all foods were classified as ‘to eat plentifully’, ‘in moderation’ or ‘on special occasions only’ o Special leaflets o Patients who were overweight (BMI over 25 kg/m2) were given special advice, including a self-monitoring chart and a choice of a calorie-restricted diet o Diet: reduction in total and saturated fat intake and an increased consumption of complex carbohydrates and fruit and vegetables o Changes recorded by nurse Follow UP 4–6 weeks, at which time progress with dietary change was assessed, weight remeasured and further changes agreed if appropriate High CVD risk or High CHolesterol– > furthre follow up at 3 and 6 months |

Lipids + Weight loss | Compliance with annual follow up was 80%. Compared with 'usual care' practices, there was a mean 0.20 mmol/l lower serum cholesterol (95% CI -0.38 to -0.03 at 1 year) in 'dietary advice' practices. There was a small fall in weight of 0.56 kg (95% CI -1.04 to -0.07) and reductions in total and saturated fat. Factor VII coagulant activity fell by a mean of 6.7% of the standard (95% CI -15.4 to + 2.0) | nurses trained by dietician | negociating changes |

for overweighted patients a choice of a calorie-restricted diet o Diet: reduction in total and saturated fat intake and an increased consumption of complex carbohydrates and fruit and vegetables |

| 1999 | Fleming MF, Manwell LB, Barry KL, Adams W, Stauffacher EA. Brief physician advice for alcohol problems in older adults: a randomized community-based trial. J Fam Pract 1999; 48: 378–84 | 105 men and 53 women. alcohol drinkers > 14 alcoholic drinks/wk (11 drinks/wk for women) | primary care, Twenty-four community-based primary care practices in Wisconsin | Intervention group patients received two 10- to 15-min physician-delivered counseling sessions that included advice, education, and contracting using a scripted workbook. Patients randomized to the intervention group were given the same booklet than the control group (general health advice) and were scheduled to see their personal physicians. The brief intervention protocol used by the participating physician included a workbook containing feedback on the patient's health behaviors, a review of problem-drinking prevalence, reasons for drinking, adverse effects of alcohol, drinking cues, a drinking agreement in the form of a prescription, and drinking diary cards. Two 10- to 15-min visits with the physician were scheduled 1 month apart (a brief intervention and a reinforcement session). Each patient received a follow-up phone call from the clinic nurse 2 weeks after each visit. Patient follow-up procedures included telephone interviews at 3, 6, and 12 months. Family members were contacted at 12 months to corroborate the patients' self-reports | alcohol consumption | At 12 months, There was a 34% reduction in 7-day alcohol use, 74% reduction in mean number of binge-drinking episodes, and 62% reduction in the percentage of older adults drinking more than 21 drinks per week in the intervention group compared with the control group | Trained physicians | Brief advice. Intervention group patients received two 10- to 15-min physician-delivered counseling sessions that included advice, education, and contracting using a scripted workbook | no |

| 1999 | Lutz, S.F., Ammerman, A.S., Atwood, J.R., Campbell, M.K., DeVellis, R.F., Rosamond, W.D. Innovative newsletter interventions improve fruit and vegetable consumption in healthy adults. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99:705–709 | 710 health maintenance organization clients | Healthy adults population |

3 intervention groups receiving: 2) non tailored newsletters, 3) computer-tailored newsletters: Participants' responses to the baseline survey were used to create messages for the tailored newsletters. Fruit or vegetable information used to tailor each newsletter included intake, eating behaviors (eg, frequency that fruits and vegetables are eaten as a snack), nutrition-related activities (eg, cooking and shopping), and psychosocial factors (eg, perceived barriers) 4) tailored newsletters with tailored goal-setting information Intervention groups received 1 newsletter each month for 4 months The baseline survey were used to tailor the newsletters Tailored goal-setting messages: subjects were given the specific difficult goal of "increasing fruit and vegetable intake to 5 or more servings each day." VS a vague, nonquantitative goal of "eating more fruits and vegetables." + 3 tailored subgoals to help them achieve the overall goal of "5 a day." These subgoals were selected using participants' responses to the eating behavior questions from the baseline survey |

Change of dietary habits | food frequency questionnaire | Theoretical constructs: self-efficacy from the Social Cognitive Theory, stage of readiness to change from the Transtheoretical Model of Change, and perceived barriers and benefits from the Health Belief Model + Goal-setting theory guided development of the tailored newsletters with a goal-setting component | All newsletters contained strategies for improving fruit and vegetable consumption. Tailored newsletters used computer algorithms to match a person's baseline survey information with the most relevant newsletter messages for promoting dietary change | |

| 1999 | Ockene IS, Hebert JR, Ockene JK, et al. Effect of physician-delivered nutrition counseling training and an office-support program on saturated fat intake, weight, and serum lipid measurements in a hyperlipidemic population: Worcester Area Trial for Counseling in Hyperlipidemia (WATCH). Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:725–31 | Eleven hundred sixty-two patients: 20–65 y/o, no prior lipid-lowering drug treatment, no dietitian referral within 1 yea | Primary care. Forty-five primary care internists at the Fallon Community Health Plan |

Interventions: - 8 to 10 min interview with PCP - WATCH intervention: o one-on-one counseling and attend group sessions o 1) increase patients' awareness of the risk factors associated with coronary heart disease; o 2) provide patients with nutrition knowledge to promote the lowering of blood cholesterol levels; o 3) increase patients' confidence in their ability to make dietary changes; o 4) enhance patient's skills needed for long-term changes in eating patterns Training: Primary care physicians o 2 sessions: § 2,5 h small group sessions (3–10 physicians): didactic instruction, videotape observation, and role-playing § 30’ individualized tutorial: role-playing the counseling-intervention approach with a patient simulator • 1) advise nutrition change and use personalized information to reinforce the need for such change; • (2) assess experience with dietary change to determine the patient's resources for change (strengths) and factors that inhibit it (barriers); • (3) review current diet using the Dietary Risk Assessment • (4) prioritize areas of high-fat intake; • (5) develop a plan for change; and • (6) arrange for follow-up - Office-support program: no training, series of handouts to be given to the patient, including the Dietary Risk Assessment, goal sheets containing dietary change recommendations, a brief cooking and recipe guide, tips for eating out, motivational material, and suggestions for further reading |

Change of dietary habits | Effective for the third group (+ office support). Compared with group 1, patients in group 3 had average reductions of 1.1 percentage points in percent of energy from saturated fat (a 10.3% decrease) (P = .01); a reduction in weight of 2.3 kg (P < .001); and a decrease of 0.10 mmol/L (3.8 mg/dL) in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level (P = .10). Average time for the initial counseling intervention in group 3 was 8.2 min, 5.5 min more than in the control group | primary care physicians | WATCH intervention | changes adapted to the Diaetary risk assessment |

| 2000 | Kristal, A.R., Curry, S.J., Shattuck, A.L., Feng, Z., Li, S. A randomized trial of a tailored, self-help dietary intervention (the Puget Sound Eating Patterns study). Prev Med. 2000;31:380–389 | Adults over 18 who were enrolled in the Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound | home-based and health care facility-based |

Participants received a package of self-help materials, dietary analysis with behavioral feedback and a semi-monthly newsletter. The self-help packet included an introductory letter with computer generated messages, a “Help Yourself” manual with inform ation, suggestions, skills, stickers and handwritten notes, individualized dietary change materials such as tip sheets, refrigerator magnet, recipe cards, shopping lists and self evaluations, and computer generated behavioral feedback. Participants received a motivational phone call. Providers received training for incorporating the self-help intervention into the medical visit. Just prior to the appointment, a self-help booklet and a script to introduce it were placedin the patient's medical chart. Telephone based surveys measured change in fat intake, food frequency, stages of change, and dietary recalls. Patients participated in a cholesterol screening Budget: $57 per patient Intervention: Self-help kit, newsletters, letters, manuals, tip sheets, magnets, recipes, shopping lists, self-evaluations, telephone, motivational call script Evaluation: Surveys, cholesterol screening device, telephone |

Change of dietary habits | The intervention effect ± SE for fat, based on a diet habits questionnaire, was -0.10 ± 0.02 (P < 0.001), corresponding to a reduction of approximately 0.8 percentage points of percentage energy from fat. For fruits and vegetables, the intervention effect was 0.47 ± 0.10 servings/day (P < 0.001) | ? | computer, telephone and self-help intervention | ? |

| 2000 | Sasaki S, Ishikawa T, Yanagibori R, Amano K. Change and 1-year maintenance of nutrient and food group intakes at a 12-week worksite dietary intervention trial for men at high risk of coronary heart disease. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol 2000;46(1):15–22 | 320 workers of Toho-Gas Compagny, Nogoya, Japan, with nonfasting serum cholesterol, nonfasting blood glucose, and/or BMI > 25 at the annual health checkup | annual health checkup |

Using the pre-intervention dietary assessment: an individual results sheet used in the education consisted of 7 pages with a summary of the subject's dietary habits and individualized advice for dietary modification Approximately 15 min of individual counseling was performed by trained nurses under the supervision of a registered dietitian During the subsequent 12wk, a newsletter was sent to the subjects every week. The newsletter consisted of an easy-to-understanding story on "how to normalize your serum cholesterol level, body weight, or blood glucose by modifying your diet," or related topics for cardiovascular prevention. The education method used in the study is described in detail more elsewhere |

Change of dietary habits | The Keys score, and the changes in intake of saturated fatty acids (SFA), monounsaturated fatty acid, total fat, and cholesterol (the decrease), as well as dietary fiber, potassium, calcium, and iron (the increase) were significantly different between the intervention (n = 63) and control (n = 123) groups (p < 0.05). The changes were almost maintained with little recidivism at the 1 y follow-up point in the intervention group (i.e., for the decrease in SFA and Keys score, p < 0.001) | trained nurses supervised by dietician | counselling + | ? |