Abstract

We used three rounds of a repeated cross-sectional survey on COVID-19 vaccination conducted throughout the entire territory of Yemen to: (i) describe the demographic and socio-economic characteristics associated with willingness to be vaccinated; (ii) analyse the link between beliefs associated with COVID-19 vaccines and willingness to be vaccinated; and (iii) analyse the potential platforms that could be used to target vaccine hesitancy and improve vaccine coverage in Yemen. Over two-thirds of respondents were either unwilling or unsure about vaccination across the three rounds. We found that gender, age, and educational attainment were significant correlates of vaccination status. Respondents with better knowledge about the virus and with greater confidence in the capacity of the authorities (and their own) to deal with the virus were more likely to be willing to be vaccinated. Consistent with the health belief model, practising one (or more) COVID-19 preventative measures was associated with a higher willingness to get a COVID-19 vaccination. Respondents with more positive views towards COVID-19 vaccines were also more likely to be willing to be vaccinated. By contrast, respondents who believed that vaccines are associated with significant side effects were more likely to refuse vaccination. Finally, those who relied on community leaders/healthcare workers as a trusted channel for obtaining COVID-19-related information were more likely to be willing to be vaccinated. Strengthening the information about the COVID-19 vaccination (safety, effectiveness, side effects) and communicating it through community leaders/healthcare workers could help increase the COVID-19 vaccine coverage in Yemen.

Keywords: COVID-19, vaccination, Yemen

1. Introduction

Yemen has been struck by a devastating civil war that has significantly impacted the country’s overall quality of life since 2011. The war has resulted in a significant number of deaths and many injuries, with many more forced to flee their homes due to the protracted hostilities. Reports of grave children’s rights violations and gender-based violence have increased [1]. In 2021, 20.7 million people (66% of the population) were estimated to be in need of humanitarian assistance. It was estimated that 16.2 million people (more than half of the population) were hungry in 2021, and over 15.4 million people (around half the population) were in need of support to access water and sanitation. Only about half (51%) of the healthcare facilities in Yemen are fully functional, and the health worker density is only 10 per 10,000 population, compared to the WHO benchmark of 22 per 10,000 [2]. About 20.1 million Yemenis (62%) are in need of health assistance. At least one child dies every ten minutes in Yemen due to preventable diseases. Furthermore, there are ongoing challenges, such as the lack of salaries for health personnel and difficulties importing medicines and other critical supplies [1].

Against this difficult background, the first COVID-19 case was registered in Yemen in April 2020, followed by warnings of a potentially catastrophic outbreak [3]. Since April 2020, the virus spread across the country, although the total number of infections and deaths due to COVID-19 was difficult to ascertain, given the poor capacity of the Yemeni healthcare system [4]. Nevertheless, a recent examination of burial activities based on satellite imagery in the governorate of Aden during the pandemic revealed that COVID-19 had had a significant, underreported impact [5].

The immunisation programme was launched on 20 April 2021 (covering 13 of the 21 governorates) [6]. Yemen received 360,000 doses of AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccinations as the first batch under the COVAX programme, according to the WHO Yemen Situation Report for March 2021. However, as of September 2022, Yemen has one of the lowest COVID-19 vaccination coverage rates globally, with about 5% of adults in Yemen having received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine [7]. Various barriers have prevented the country from increasing COVID-19 vaccination coverage, including pre-existing barriers such as vaccine hesitancy, lack of adequate supplies of vaccines in Yemen, and political instability [3]. The existing literature suggests that these barriers were amplified during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Studies

A study by Bitar et al. [8] relied on a sample of 484 participants and focused on two major questions: the main characteristics of misinformation and the main characteristics of vaccination hesitancy or rejection (the study was carried out before the immunisation campaign in Yemen had begun). University educated, higher income, employed, males living in urban areas were associated with lower misinformation about vaccination in general. In the same study, the acceptance rate for vaccination was 61% for free vaccines, and it decreased to 43% if participants had to purchase it. Females, respondents with lower monthly income, and those who believed that pharmaceutical companies made the virus for financial gains were more likely to reject the COVID-19 vaccination [8]. While beliefs were the main focus of the study by Bitar and colleagues [8], Noushad et al. [9] argued that severe shortage and lack of access to vaccines drove the low vaccination rates in the country. According to their study (conducted via WhatsApp survey to 5329 participants), over half of the respondents were willing to be vaccinated [9]. Finally, in a study by Bin Ghouth et al. [10], beliefs about the vaccine’s lack of safety and bad quality significantly contributed to a lower willingness to be vaccinated.

While there is some information on vaccination willingness and hesitancy in Yemen, the information is incomplete, as outlined above. To date, most of the existing evidence on vaccination uptake is based on one-off, small-scale surveys conducted using convenience sampling and are not representative of the population of Yemen. Against this background, this research paper aims to provide better understanding of the main correlates of vaccination intention and vaccination hesitancy, relying on a repeated cross-sectional survey conducted across Yemen. More specifically, the objective of this research paper is to describe three vaccination “personas” (willing, unwilling to be vaccinated, and unsure) in terms of (i) demographic and other individual characteristics (including knowledge and exposure to COVID-19); (ii) their main vaccination related beliefs (e.g., safety, side effects); and (iii) their preferred channels for reaching communities (e.g., community leaders, social media).

2. Methodology

2.1. Survey Instrument

We used three rounds of a survey titled “Rapid assessment of knowledge, attitudes and practices related to COVID-19” in Yemen. The survey was implemented in five rounds; however, this paper focuses on the last three rounds, where the questions on vaccination intention were asked (March 2021, August/September 2021 and April 2022).

There were about 1400 respondents per round across the entire country. The sample size was determined based on several factors, a population size of 14 million people (population at age > 17), a confidence level of 95%, and a margin of error of approximately 2.5%. The formula for calculating sample size:

| Sample size= (z2 xp (1 − p)/e2)/1 + (z2 xp (1 − p)/e2 N) |

N—population size, e—Margin of error (percentage in decimal form), z—z-score.

The three rounds of the survey followed a repeated cross-section format (rather than a longitudinal survey format); thus, the same individuals did not appear in all three rounds of the survey.

The survey was administered over the phone in the south of the country and face-to-face in the northern part. In the north of the country, for the selection of the enumeration areas, governorates were identified to serve as primary sampling units (PSUs); based on this, governorates were implicitly stratified to allow for a random selection of clusters while considering the ease of access during the selection (e.g., not a conflict-affected zone, no restrictions from authorities). In turn, a simple random selection was applied for selection to be interviewed in each governorate. By contrast, the interviews in the south were carried out over the phone. More specifically, random numbers were selected from a dataset of phone numbers in the south (noting that this method impacts upon the representativeness of the sample in the south). The application of these different data collection methods did not significantly impact the response rate across the country. In other words, the number of interviews conducted are equal to the specified sample size in each round, both in the south and in the north.

The objective of the survey was to: (i) describe the demographic and socio-economic characteristics associated with a willingness to be vaccinated; (ii) analyse the link between beliefs associated with COVID-19 vaccines and willingness to be vaccinated; and (iii) analyse the potential platforms that could be used in order to target vaccine hesitancy and improve vaccine coverage in Yemen. The survey instrument included items related to (i) knowledge of symptoms, transmission, and prevention; (ii) peoples’ sources of information; (iii) risk perception; (iv) information needs of respondents; (v) COVID-19-related stigma; and (vi) hesitancy or acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine. The questionnaire used for the data collection underwent a thorough review process, with input from several partners and counterparts, including the World Health Organisation as well as members of various United Nations and government coordination and decision-making bodies such as the COVID-19 task force and the risk communication and community engagement working group. Additionally, the questionnaire was pre-tested with selected participants to ensure clarity and relevance. The questionnaire is available upon request.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

We adopted a descriptive analysis of the main characteristics of three vaccination personas: (a) those willing; (b) unsure if they wanted to be vaccinated, and (c) those unwilling. In order to distil the three personas, we relied on the following question from the survey: “Would you be willing to get the COVID-19 vaccine when one becomes available in Yemen?”. Furthermore, the characteristics of the three personas were grouped into three major groups: (i) socio-demographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender, occupation), practising public health and social measures (PHSM), risk perception and trust in authorities); (ii) a second group relating to attitudes and beliefs towards the COVID-19 vaccines (e.g., beliefs in the vaccine safety and side effects); (iii) the final group of characteristics corresponding to the preferred channels for reaching different personas. As outlined above, in order to understand the characteristics of the different vaccination categories, we conducted a descriptive analysis, coupled with chi2 test of the difference between categorical variables. In carrying out the analysis, we focussed on the last round of the survey (round 5) and provide the analysis of the previous two rounds in Appendix A of the paper.

3. Results

3.1. Overall Description of the Sample

Table 1 provides a socio-demographic snapshot of the sample, across the three rounds. About one-third of respondents had completed secondary education and another quarter had completed some college degree, and roughly four-fifths of respondents were less than 50 years of age. Only a fraction of the sample had no or very little formal education. In round 5, about 7% of respondents could not read or write, while 15.6% had basic reading and writing skills. There were more males than females in the sample; more specifically, by the fifth round of the survey, about two-thirds of the sample consisted of males. Furthermore, the sample was almost equally split between the professions included in the study (educators, housewives, students, and office workers).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the data used in the analysis.

| Round 3 (March 2021) | Round 4 (Aug/Sept 2021) | Round 5 (April 2022) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | |

| Age | ||||||

| under 20 | 6.4 | 89 | 7.4 | 104 | 7.0 | 101 |

| 21 to 30 | 29.3 | 408 | 31.6 | 446 | 28.7 | 416 |

| 31 to 40 | 31.8 | 443 | 30.7 | 433 | 31.2 | 452 |

| 41 to 50 | 21.3 | 296 | 18.1 | 255 | 20.9 | 303 |

| 51 to 60 | 9.1 | 127 | 10.3 | 145 | 9.4 | 136 |

| 61 to 70 | 1.7 | 23 | 2.1 | 29 | 2.2 | 32 |

| 71 and above | 0.4 | 6 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.7 | 10 |

| Education | ||||||

| cannot read and write | 10.0 | 140 | 10.4 | 147 | 7.2 | 105 |

| can read and write | 18.2 | 255 | 15.6 | 220 | 15.6 | 226 |

| basic | 12.0 | 167 | 12.2 | 173 | 14.9 | 216 |

| secondary | 28.7 | 401 | 27.7 | 391 | 31.0 | 450 |

| college degree | 29.3 | 409 | 31.8 | 449 | 27.8 | 404 |

| masters or PhD | 1.9 | 26 | 2.3 | 33 | 3.5 | 50 |

| Gender | ||||||

| female | 46.6 | 651 | 42.9 | 606 | 34.1 | 494 |

| male | 53.4 | 747 | 57.1 | 807 | 66.0 | 957 |

| Occupation | ||||||

| agricultural | 9.0 | 126 | 10.5 | 149 | 8.9 | 129 |

| educational | 14.5 | 203 | 17.1 | 242 | 14.0 | 203 |

| housewife | 24.7 | 345 | 19.9 | 281 | 17.4 | 252 |

| office | 12.4 | 173 | 11.8 | 167 | 16.3 | 237 |

| student | 13.8 | 193 | 12.7 | 179 | 15.2 | 220 |

| unemployed | 6.9 | 97 | 5.9 | 84 | 4.1 | 60 |

| handicraft | 9.7 | 136 | 14.1 | 199 | 19.0 | 276 |

| other | 8.9 | 125 | 7.9 | 112 | 5.1 | 74 |

| Likely to become sick with COVID-19 | ||||||

| I do not know | 40.7 | 554 | 36.2 | 506 | 38.0 | 550 |

| Yes | 41.3 | 563 | 49.0 | 685 | 49.8 | 721 |

| No | 18.1 | 246 | 14.9 | 208 | 12.3 | 178 |

| Trust in the official information from the authorities | ||||||

| no confidence | 26.8 | 337 | 16.5 | 210 | 14.6 | 193 |

| little confidence | 38.8 | 489 | 35.1 | 447 | 26.9 | 356 |

| confident | 27.4 | 345 | 36.1 | 460 | 50.7 | 670 |

| total confidence | 7.0 | 88 | 12.4 | 158 | 7.8 | 103 |

| PHSM in the last 10 months | ||||||

| practised social distancing | 32.8 | 447 | 37.0 | 517 | 21.4 | 310 |

| worn a mask | 62.3 | 849 | 71.3 | 997 | 74.3 | 1077 |

| washed hands | N/A | N/A | 78.3 | 1095 | 82.0 | 1188 |

| PHSM in the last 4 weeks | ||||||

| practised social distancing | 18.9 | 257 | 10.5 | 147 | 3.9 | 57 |

| worn a mask | 32.7 | 446 | 37.9 | 530 | 32.1 | 464 |

| washed hands | N/A | N/A | 50.0 | 699 | 42.6 | 617 |

Notes: PHSM—public health and social measures.

Between round 3 (March, 2021) and round 5 (April, 2022), the share of respondents who believed they could become infected with COVID-19 had increased. By the fifth round of the survey data, almost half of respondents stated they felt at risk of being infected by the virus. Over time, there was an increase in confidence regarding COVID-19 information provided by the authorities, coinciding with enhanced management of COVID-19. By the fifth round, over half of respondents reported confidence or total confidence in official COVID-19 information from the authorities. However, 14.6% of respondents still had no confidence and might resist authorities’ appeals for vaccine uptake. In addition, the reopening of the country, coupled with the relaxing of some of the stringent measures aimed at containing the virus, resulted in a reduction in the share of respondents practising various public health and social measures (PHSM). More specifically, by the fifth round, only about four percent of respondents practised social distancing (over the last four weeks), while about a third wore a mask in public, whereas handwashing seemed to be a more embedded habit with close to half of respondents (42.6%) still reporting washing their hands regularly with soap and warm water.

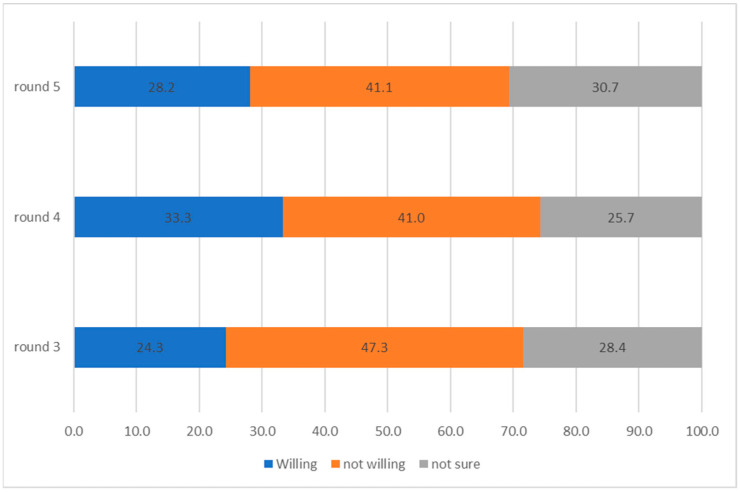

Figure 1 provides a summary of vaccination intention over time. There are a few important findings that stem from this analysis. While initially, the share of respondents not willing to be vaccinated had decreased (between rounds 3 and 4), there was very little change between rounds 4 and 5. More specifically, roughly 41% of respondents stated that they were not willing to receive the COVID-19 vaccination when it became available. Second, between rounds 3 and 4, there was an increase in the share of people willing to be vaccinated; however, it had reduced between rounds 4 and 5, at the expense of respondents who were not sure/undecided. By round 5, 28.2% of respondents were willing to be vaccinated, while 30.7% reported that they were unsure.

Figure 1.

Vaccination status, over time, in %.

Figure 2 depicts the practice of various PHSM over time. There are a few major findings that stem from this chart. First, as the pandemic ebbed, the authorities were less stringent regarding enforcement of various measures to stop the transmission of the virus. Indeed, as the chart shows, the share of people practising PHSM over the last four weeks is roughly half compared to the share of the respondents practising the same type of PHSM in the previous ten months. In addition, there are visible differences in the prevalence of different PHSM. Handwashing (albeit measured only in rounds 4 and 5) is the most prevalent and sustained type of PHSM. For example, in round 5, just forty percent of respondents had practised handwashing in the last four weeks. Noting that handwashing pre-dated COVID-19 and is relevant well beyond COVID-19, its endurance over other PHSM was understandable. By contrast, about one-third of respondents reported mask-wearing (face covering). The rest of the PHSM were practised by a lower share of respondents, which had drastically dropped over time. This was particularly the case with measures such as not attending the mosque and avoiding social gatherings.

Figure 2.

Selected PHSM, over time, in %.

3.2. Vaccination Personas

3.2.1. Persona 1: Willing to Be Vaccinated

There is some scant evidence that those willing to get vaccinated were slightly younger (Table 2), although the relationship between age and willingness to vaccinate is statistically insignificant. Furthermore, about a third of those with college degrees and close to half of respondents with higher degrees tended to be willing to be vaccinated. Consistent with the established notion from other countries and studies of other health practices, men were more likely than women to be willing to receive a COVID-19 vaccination. About a third of those who felt at risk of becoming infected with the virus were willing to receive at least one dose of the vaccine. Table 2 also provides some evidence that this vaccination persona tended also to adhere to public health and social measures (PHSM). For example, more than a third of those who practised social distancing were willing to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. Similarly high was the share of these respondents who stayed away from the mosque and were willing to receive a vaccination.

Table 2.

Round 5, vaccination status and socio-demographic characteristics.

| Willing | Not Sure | Not Willing | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | chi2 p-Value | |

| Age | |||||||

| under 20 | 37 | 37 | 32 | 32 | 31 | 31 | <0.001 |

| 21 to 30 | 33.4 | 139 | 30.8 | 128 | 35.8 | 149 | |

| 31 to 40 | 29.3 | 132 | 29.5 | 133 | 41.2 | 186 | |

| 41 to 50 | 21.5 | 65 | 32 | 97 | 46.5 | 141 | |

| 51 to 60 | 18.4 | 25 | 32.4 | 44 | 49.3 | 67 | |

| 61 to 70 | 18.8 | 6 | 25 | 8 | 56.3 | 18 | |

| 71 and above | 30 | 3 | 30 | 3 | 40 | 4 | |

| Education | |||||||

| cannot read and write | 14.3 | 15 | 18.1 | 19 | 67.6 | 71 | <0.001 |

| can read and write | 18.1 | 41 | 29.2 | 66 | 52.7 | 119 | |

| basic | 34 | 73 | 29.8 | 64 | 36.3 | 78 | |

| secondary | 28.7 | 129 | 33.6 | 151 | 37.8 | 170 | |

| college degree | 31.3 | 126 | 32.5 | 131 | 36.2 | 146 | |

| masters or PhD | 48 | 24 | 28 | 14 | 24 | 12 | |

| Gender | |||||||

| female | 19.5 | 96 | 29.9 | 147 | 50.6 | 249 | <0.001 |

| male | 32.6 | 312 | 31.1 | 298 | 36.3 | 347 | |

| Occupation | |||||||

| agricultural | 14 | 18 | 28.7 | 37 | 57.4 | 74 | <0.001 |

| educational | 30.1 | 61 | 34 | 69 | 36 | 73 | |

| housewife | 16.7 | 42 | 28.7 | 72 | 54.6 | 137 | |

| office | 31.2 | 74 | 35 | 83 | 33.8 | 80 | |

| student | 38.8 | 85 | 31.1 | 68 | 30.1 | 66 | |

| unemployed | 20 | 12 | 38.3 | 23 | 41.7 | 25 | |

| handicraft | 30.8 | 85 | 27.5 | 76 | 41.7 | 115 | |

| other | 41.9 | 31 | 23 | 17 | 35.1 | 26 | |

| Likely to become sick with COVID-19 | |||||||

| I do not know | 20.9 | 115 | 33.6 | 185 | 45.5 | 250 | <0.001 |

| yes | 36.8 | 265 | 30.9 | 223 | 32.3 | 233 | |

| no | 15.7 | 28 | 20.8 | 37 | 63.5 | 113 | |

| Public Health and Social Measures over the last 10 months | Willing | Not sure | Not willing | ||||

| Practised social distancing | % | number | % | number | % | number | chi2 p-value |

| no | 25.9 | 295 | 30.7 | 350 | 43.4 | 494 | <0.001 |

| yes | 36.5 | 113 | 30.7 | 95 | 32.9 | 102 | |

| Worn a mask | |||||||

| no | 13.2 | 49 | 25.3 | 94 | 61.6 | 229 | <0.001 |

| yes | 33.3 | 359 | 32.6 | 351 | 34.1 | 367 | |

| Stayed away from the mosque | |||||||

| no | 26.7 | 345 | 31 | 400 | 42.3 | 547 | <0.001 |

| yes | 40.1 | 63 | 28.7 | 45 | 31.2 | 49 | |

| Wash hands | |||||||

| no | 13.8 | 36 | 24.1 | 63 | 62.1 | 162 | <0.001 |

| yes | 31.3 | 372 | 32.2 | 382 | 36.5 | 434 | |

| Avoided social gatherings | |||||||

| no | 26.4 | 263 | 29.6 | 295 | 44 | 438 | <0.001 |

| yes | 32 | 145 | 33.1 | 150 | 34.9 | 158 | |

| Public Health and Social Measures over the last 4 weeks | Willing | Not sure | Not willing | ||||

| Practised social distancing | % | number | % | number | % | number | chi2 p-value |

| no | 27.5 | 383 | 31 | 431 | 41.5 | 578 | <0.001 |

| yes | 43.9 | 25 | 24.6 | 14 | 31.6 | 18 | |

| Worn a mask | |||||||

| no | 21 | 207 | 30.7 | 302 | 48.3 | 476 | <0.001 |

| yes | 43.3 | 201 | 30.8 | 143 | 25.9 | 120 | |

| Stayed away from the mosque | |||||||

| no | 27.7 | 394 | 31 | 442 | 41.3 | 589 | <0.001 |

| yes | 58.3 | 14 | 12.5 | 3 | 29.2 | 7 | |

| Wash hands | |||||||

| no | 21.4 | 178 | 29.7 | 247 | 48.9 | 407 | <0.001 |

| yes | 37.3 | 230 | 32.1 | 198 | 30.6 | 189 | |

| Avoided social gatherings | |||||||

| no | 27.2 | 377 | 31 | 430 | 41.9 | 581 | <0.001 |

| yes | 50.8 | 31 | 24.6 | 15 | 24.6 | 15 | |

Table 3 summarises the analysis of vaccination status and knowledge regarding COVID-19. There are a few conclusions that stem from the table. First, the willingness to be vaccinated increased as knowledge about protecting oneself from the virus increased. More specifically, 40.6% of those with excellent knowledge about how to protect themselves were willing to be vaccinated. Similarly, willingness to be vaccinated increased as trust in the official information from authorities and their ability to deal with the virus increased. In addition, willingness to be vaccinated is a function of risk perception of the dangers of the virus. For example, 40.3% of respondents who thought the virus was dangerous were willing to be vaccinated.

Table 3.

Round 5, vaccination status and knowledge regarding COVID-19.

| Willing | Not Sure | Not Willing | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge to Protect Yourself from the Virus | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | chi2 p-Value |

| no knowledge | 2.3 | 1 | 16.3 | 7 | 81.4 | 35 | <0.001 |

| needs improvement | 12.3 | 32 | 27.3 | 71 | 60.4 | 157 | |

| good | 32.3 | 265 | 33.7 | 277 | 34 | 279 | |

| very good | 28.9 | 54 | 34.8 | 65 | 36.4 | 68 | |

| excellent | 40.6 | 56 | 18.1 | 25 | 41.3 | 57 | |

| Trust in the official information from the authorities | |||||||

| no confidence | 14 | 27 | 22.8 | 44 | 63.2 | 122 | <0.001 |

| little confidence | 18.5 | 66 | 36.5 | 130 | 44.9 | 160 | |

| confident | 37.6 | 252 | 31.5 | 211 | 30.9 | 207 | |

| total confidence | 42.7 | 44 | 21.4 | 22 | 35.9 | 37 | |

| Trust in your own ability to deal with the virus | |||||||

| no confidence | 19.5 | 25 | 29.7 | 38 | 50.8 | 65 | <0.001 |

| little confidence | 16.3 | 54 | 33.5 | 111 | 50.2 | 166 | |

| confident | 34.4 | 226 | 31.2 | 205 | 34.4 | 226 | |

| total confidence | 41.2 | 70 | 27.1 | 46 | 31.8 | 54 | |

| How dangerous do you think the COVID-19 virus is | |||||||

| it is not dangerous | 2.6 | 7 | 24.9 | 66 | 72.5 | 192 | <0.001 |

| more or less dangerous | 29.5 | 189 | 33 | 211 | 37.5 | 240 | |

| very dangerous | 40.3 | 210 | 31.1 | 162 | 28.6 | 149 | |

We next turned to the link between vaccination status and beliefs about COVID-19 vaccines (Table 4). Consistent with the existing research, positive beliefs about the vaccine are associated with a higher willingness to be vaccinated. Nearly half (48.2%) of respondents who thought that the vaccine is effective were willing to be vaccinated. Similar findings emerged when considering beliefs about side effects. The results from the previous two rounds are reported in Appendix A, Table A3, and they were consistent with the findings emerging from round 5.

Table 4.

Round 5, vaccination status and COVID-19 vaccine beliefs.

| Willing | Not Sure | Not Willing | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccine Is Effective | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | chi2 p-Value |

| no | 10.3 | 65 | 37.7 | 238 | 52 | 328 | <0.001 |

| yes | 48.2 | 339 | 25.8 | 181 | 26 | 183 | |

| Vaccine has side effects | |||||||

| no | 48.1 | 317 | 22.9 | 151 | 29 | 191 | <0.001 |

| yes | 12.9 | 87 | 39.7 | 268 | 47.7 | 320 | |

Various sources of information could be used as a vehicle to increase vaccine acceptance and, thus, vaccine uptake. This, however, depends on what type of information source is most trusted vis-à-vis COVID-19 vaccines. Against this background, we next turned to the link between vaccination status and the most trusted source of information (Table 5). Half (50%) of respondents listing community leaders as the most trusted COVID-19 information source were willing to be vaccinated (Table 5). Similar findings emerged from the previous two rounds (Appendix A, Table A4). In addition, in some of the previous rounds (e.g., round 3) we also found evidence that those who listed community healthcare workers as a trusted source of information were more likely to be willing to receive a COVID-19 vaccination. This persona tends to trust communication materials and community leaders more than other personas trust these sources of information.

Table 5.

Round 5, vaccination status and most trusted COVID-19 information source.

| Most Trusted Source | Willing | Not Sure | Not Willing | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | chi2 p-Value | |

| TV | |||||||

| first mention | 35.6 | 252 | 28.4 | 201 | 36 | 255 | <0.001 |

| second mention | 15.8 | 15 | 39 | 37 | 45.3 | 43 | |

| third mention | 22.6 | 7 | 35.5 | 11 | 41.9 | 13 | |

| Radio | |||||||

| first mention | 16.8 | 19 | 37.2 | 42 | 46 | 52 | 0.56 |

| second mention | 10.3 | 3 | 37.9 | 11 | 51.7 | 15 | |

| third mention | 28.6 | 4 | 21.4 | 3 | 50 | 7 | |

| first mention | 33.1 | 46 | 33.8 | 47 | 33.1 | 46 | 0.21 |

| second mention | 28.6 | 22 | 29.9 | 23 | 41.6 | 32 | |

| third mention | 14.7 | 5 | 35.3 | 12 | 50 | 17 | |

| Social media | |||||||

| first mention | 36.4 | 51 | 34.3 | 48 | 29.3 | 41 | 0.21 |

| second mention | 37.1 | 39 | 31.4 | 33 | 31.4 | 33 | |

| third mention | 21.2 | 11 | 34.6 | 18 | 44.2 | 23 | |

| Communication materials | |||||||

| first mention | 47 | 31 | 27.3 | 18 | 25.8 | 17 | 0.16 |

| second mention | 42.9 | 18 | 35.7 | 15 | 21.4 | 9 | |

| third mention | 20 | 5 | 40 | 10 | 40 | 10 | |

| Health unit | |||||||

| first mention | 29.5 | 31 | 22.9 | 24 | 47.6 | 50 | 0.32 |

| second mention | 18.4 | 16 | 26.4 | 23 | 55.2 | 48 | |

| third mention | 30 | 12 | 30 | 12 | 40 | 16 | |

| Family | |||||||

| first mention | 10.4 | 23 | 24.3 | 54 | 65.3 | 145 | 0.07 |

| second mention | 17.9 | 17 | 27.4 | 26 | 54.7 | 52 | |

| third mention | 23.7 | 9 | 29 | 11 | 47.4 | 18 | |

| Friends | |||||||

| first mention | 28 | 30 | 22.4 | 24 | 49.5 | 53 | 0.03 |

| second mention | 20.6 | 21 | 24.5 | 25 | 54.9 | 56 | |

| third mention | 6.7 | 4 | 31.7 | 19 | 61.7 | 37 | |

| Community health workers | |||||||

| first mention | 26.8 | 37 | 32.6 | 45 | 40.6 | 56 | 0.29 |

| second mention | 25.6 | 21 | 28.1 | 23 | 46.3 | 38 | |

| third mention | 21.3 | 13 | 21.3 | 13 | 57.4 | 35 | |

| Volunteers | |||||||

| first mention | 39.5 | 43 | 23.9 | 26 | 36.7 | 40 | 0.35 |

| second mention | 27.1 | 19 | 24.3 | 17 | 48.6 | 34 | |

| third mention | 33.3 | 15 | 31.1 | 14 | 35.6 | 16 | |

| Community leaders | |||||||

| first mention | 50 | 8 | 25 | 4 | 25 | 4 | 0.07 |

| second mention | 5.9 | 1 | 47.1 | 8 | 47.1 | 8 | |

| third mention | 24 | 6 | 32 | 8 | 44 | 11 | |

| Religious leaders | |||||||

| first mention | 22.3 | 37 | 33.7 | 56 | 44 | 73 | 0.52 |

| second mention | 25.6 | 22 | 24.4 | 21 | 50 | 43 | |

| third mention | 23.2 | 19 | 25.6 | 21 | 51.2 | 42 | |

| Traditional healers | |||||||

| first mention | 30.8 | 4 | 15.4 | 2 | 53.9 | 7 | 0.27 |

| second mention | 25 | 3 | 25 | 3 | 50 | 6 | |

| third mention | 0 | 0 | 45.5 | 5 | 54.6 | 6 | |

| A person from the community | |||||||

| first mention | 44.4 | 4 | 22.2 | 2 | 33.3 | 3 | 0.2 |

| second mention | 66.7 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 33.3 | 3 | |

| third mention | 28.6 | 8 | 35.7 | 10 | 35.7 | 10 | |

3.2.2. Persona 2: Not Vaccinated and Undecided

As in the case above, here as well, age, gender, and education were the main correlates of this persona (not vaccinated and undecided). A large share of the unemployed (38%) were undecided regarding a possible vaccination, suggesting a link to employer encouragement being a strong incentive for vaccination. About a third of those with no opinion regarding potential infection with the virus were undecided regarding obtaining a vaccine. Furthermore, no discernible link emerged between practising PHSM and being undecided about potentially obtaining a COVID-19 vaccination. About a quarter of those who believed that the vaccine is effective were undecided regarding taking it (slightly lower compared to those who did not think that there were serious side effects if/when taking the vaccine). This persona appeared to draw information from a wide range of sources, which may be contradictory.

3.2.3. Persona 3: Not Willing to Get Vaccinated

As with the persona above, here as well, we found some evidence that this vaccination persona was older than the other categories. In addition, less educated by a significant margin. About two-thirds of respondents who could not read and write were not willing to get vaccinated. About half of women were unwilling to obtain a COVID-19 vaccine (about 15 percentage points higher than men). Almost two-thirds (63.5%) of respondents who stated that they did not believe they were likely to get infected with the virus were also unwilling to be vaccinated. Table 2 also provides the results of the link between vaccination status and practising different PHSM (wearing a mask in public, washing hands, keeping physical distance, and staying away from crowds/the mosque). The question on the PHSM practice was asked in reference to two time periods: 10 months ago and four weeks ago. The results of this analysis were unequivocal: those who did not practice PHSM were also less likely to be willing to be vaccinated. For example, 48.3% of respondents who claimed they did not wear a mask in public were unwilling to be vaccinated.

This vaccination persona was less knowledgeable about the COVID-19 virus (Table 3). For example, 81.4% of those with no knowledge were unwilling to obtain the vaccine. By the same token, this persona tended to believe that the virus is not dangerous. More specifically, 72.5% of those claiming the virus is not dangerous were unwilling to be vaccinated. Furthermore, this vaccination persona held negative attitudes and beliefs towards the vaccines. For example, about half (52%) of respondents who did not think that the vaccine is effective were unwilling to be vaccinated (Table 4). Finally, this group of people tended to trust their family and friends more than other personas for information regarding COVID-19.

As a complementary analysis, we also conducted the standard logit modelling analysis, where the three vaccination personas appeared as dependent variables in three separate models. The explanatory variables were grouped into three major groups: (i) socio-demographic variables (e.g., age, gender); (ii) practising some of the most common public health and social measures (e.g., wearing a mask, washing hands); and (iii) beliefs about the COVID-19 vaccines (e.g., effectiveness, side effects). The results are reported as Appendix A tables (Table A4, Table A5 and Table A6). The analysis supports the findings from the descriptive statistics; more specifically, certain demographic variables (e.g., gender) and variables capturing beliefs about COVID-19 vaccines explained the decision to obtain a COVID-19 vaccination.

In order to capture the PHSM/vaccination status nexus over time, we pooled the three waves together and used the three vaccination personas as dependent variables in three separate bivariate logit models (where the variables capturing different PHSM were used as independent variables). We repeated the analysis twice, first using PHSM practised over the last ten months and then over the last four weeks. The models also controlled for the survey wave (i.e., taking into account any temporal changes occurring over the three different waves). The findings (reported in Appendix A, Table A7 and Table A8) were unequivocal: those more willing to be vaccinated were also more willing to adhere to various PHSM (both over the last ten months as well as over the last four weeks).

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive attempt to describe various vaccination personas in Yemen, relying on a sample covering the entire country and spanning three points in time. In that respect, there are a few interesting findings that emerge from this study. First, our findings on the socio-demographic characteristics of vaccination willingness are consistent with the existing evidence. A recent paper using two waves of repeated cross-sectional surveys from the Middle East, North Africa, and Eastern Mediterranean region [11], for example, found that men, on average, were more likely to be vaccinated and to be willing to be vaccinated once vaccines were available to them. The same study also posits that men may be also advantaged by their higher level of mobility than women in parts of the region, and their higher engagement in formal employment, which may offer additional incentives for vaccination. The same study showed that women were disproportionately affected by misinformation about fertility, which also seemed to affect their willingness to be vaccinated. In addition, it has been argued that women are more likely to embrace conspiracy theories about the virus [12]. Other potential factors that can contribute to higher rates of vaccine hesitancy among females include the higher levels of fear of injections or side effects and the observation that the disease is more deadly in males [12]. Furthermore, in countries where men have greater access to healthcare services and the means to pay for vaccination than women, men may be more interested in the COVID-19 vaccination [13,14].

A study by Bitar et al. [7], also found that men were more likely to be willing to be vaccinated, while women were more likely to reject the vaccine. That study also finds that those with lower income are likely to reject the vaccines. While in our study, we did not have a variable capturing income, our variable on education attainment could be considered as a proxy for socio-economic status.

We also found that respondents who were practising some forms of preventative measures (e.g., wearing a mask, washing hands, practising social distancing) were more likely to be willing to obtain a vaccination. This finding supports the general health motivation construct in the health belief model [15], and aligns with social identity theory [16], which suggests that people who practise one health behaviour (such as vaccination) are more likely to practise others, such as PHSM in relation to the containment of COVID-19. Some of these associations were explored in a recent paper involving two rounds of repeated cross-sectional data on 14,000 respondents from the wider MENA region [11].

One of our principal findings relates to the link between vaccine beliefs and willingness to be vaccinated. To date, a large body of evidence stemming from the Middle East, North Africa, and Eastern Mediterranean region has also documented the link between vaccine beliefs and vaccination status. A study about vaccination among healthcare workers in Egypt, for example, found that the reasons for vaccine acceptance revolved around safety and effectiveness, while fear of side effects was the main reason for vaccine hesitancy [17]. Concerns about safety as well as a general lack of trust in the vaccines, were the main reason for vaccine hesitancy among healthcare workers in Sudan and Iraq [18,19]. Lack of trust in vaccine effectiveness and fear of side effects were the also main reasons for refusing to be vaccinated among the general population [17,20,21,22], while the belief in the effectiveness and benefits associated with the COVID-19 vaccination were the main reasons for vaccine acceptance [20,23].

These findings need to be interpreted within the broader context of the political situation in Yemen, which affected the availability of accurate information and vaccination services (including the availability of vaccines), particularly in the northern DFA (de facto authority)-controlled provinces. Across Yemen, a variety of misinformation about COVID-19 immunisation has taken root. The most frequently stated reasons for poor vaccination uptake by key informants in a study by Bin Ghouth and Al-Kaldy [9] were comparable to the findings of a sub-national survey carried out in early 2021 [24]. Some participants in that study saw the vaccination as a planned “scheme” that posed a danger to their health. Some individuals felt that the vaccination would cause death over time rather than instantly. Some claimed that the vaccine effort is a plot to create Muslim infertility [25]. Others said that the West was supplying Yemen with inadequate vaccinations [26]. People in the northern regions, on the other hand, did not see COVID-19 as a danger [24].

Finally, we found that respondents using certain sources of information (e.g., community leaders and volunteers) were more likely to be willing to be vaccinated. Compared to the regional average, trust in health workers is lower in Yemen, which can reasonably be expected to have an impact on vaccine uptake; the research in the area of vaccine demand generation has distilled two approaches. The first, more passive one, has relied on the use of mass media (TV and radio) and printed materials (banners, leaflets, posters) [27]. The second approach involved deeper face-to-face engagement with households and individual caregivers—often by trained volunteers from the community using interpersonal communication and behaviour change approaches. The success of this approach relies on extensive efforts by the community outreach workers to directly interact with the community as well as with individual caregivers. Even though the second approach is more labour intensive (and more expensive), it may also yield higher returns per contact when it comes to vaccination uptake, especially given the lower trust in health workers in Yemen.

There are some limitations associated with this research. First, the analysis is descriptive and only explores the correlation between vaccination status and the variables of interest. Correlations may be confounded by other observed and unobserved variables. In that respect, we cannot infer any direct causal links by using this methodological approach. Second, some questions changed over the course of the five rounds (e.g., additional categories were added to the most trusted source of information question), which may have some implications on the overall responses collected through this question. As the estimation and projection of demographic data in Yemen is of poor quality, the survey did not develop survey weights. More specifically, the results were not weighted for survey weights to address the representativeness of the sample. These limitations notwithstanding, there are some broad conclusions that stem from this research. First, we found that gender and socio-demographic status (e.g., education attainment) were significant correlates of vaccination status, consistent with existing knowledge. Second, respondents with better knowledge about the virus and with better confidence in authorities’ (and their own) capacity to deal with the virus were more likely to be willing to be vaccinated. Consistent with the health belief model, practising one (or more) preventative measures in relation to COVID-19 was associated with a higher willingness to get a COVID-19 vaccination. In addition, beliefs around the COVID-19 vaccines were also linked to willingness (or lack of willingness) to obtain a vaccination. Finally, those who relied on community leaders/healthcare workers as trusted sources of COVID-19-related information were more willing to be vaccinated.

Finally, there are some broad policy recommendations that stem from this research effort. Any focus on individual motivation for vaccination relies on the basic requirement that adequate vaccination services are made available to all communities. That said, outreach to communities and a localised focus on the needs of those who are undecided about vaccination can be effective in increasing uptake, thereby also increasing the social norm around being vaccinated. Supplying them with information about the COVID-19 vaccines (e.g., safety, effectiveness, and side effects) and access to trusted and skilled health workers could mitigate fears and increase confidence in the vaccines. Identifying vaccination champions among families/communities could further allay some of the fears associated with vaccines (e.g., fears of side effects). Religious leaders and other community leaders (including females) can have a strong influence on communities in Yemen, both positively and negatively—and should be considered key partners, especially in terms of understanding and addressing the needs of local communities.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Round 3 and 4, vaccination status and demographic/socio-economic characteristics.

| Round 3 | Round 4 | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Willing | Not Willing | Not Sure | Willing | Not Willing | Not Sure | ||||||||||

| % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | chi2 p-Value | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | chi2 p-Value | ||

| Age | Age | ||||||||||||||

| less than 20 | 25.8 | 23 | 44.9 | 40 | 29.2 | 26 | 0.3 | less than 20 | 29.8 | 31 | 47.1 | 49 | 23.1 | 24 | 0.1 |

| 21 to 30 | 24.5 | 99 | 45.8 | 185 | 29.7 | 120 | 21 to 30 | 34.5 | 153 | 37.5 | 166 | 28.0 | 124 | ||

| 31 to 40 | 25.8 | 112 | 47.9 | 208 | 26.3 | 114 | 31 to 40 | 31.8 | 137 | 41.8 | 180 | 26.5 | 114 | ||

| 41 to 50 | 24.3 | 71 | 44.5 | 130 | 31.2 | 91 | 41 to 50 | 37.7 | 95 | 36.5 | 92 | 25.8 | 65 | ||

| 51 to 60 | 15.0 | 17 | 57.5 | 65 | 27.4 | 31 | 51 to 60 | 30.7 | 43 | 50.7 | 71 | 18.6 | 26 | ||

| 61 to 70 | 26.3 | 5 | 52.6 | 10 | 21.1 | 4 | 61 to 70 | 21.4 | 6 | 53.6 | 15 | 25.0 | 7 | ||

| 71 and above | 60.0 | 3 | 40.0 | 2 | 0.0 | 0 | 71 and above | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | ||

| Education | Education | ||||||||||||||

| can’t read and write | 15.5 | 19 | 49.6 | 61 | 35.0 | 43 | <0.001 | can’t read and write | 18.7 | 26 | 51.1 | 71 | 30.2 | 42 | <0.001 |

| can read and write | 18.5 | 45 | 50.6 | 123 | 30.9 | 75 | can read and write | 28.8 | 63 | 46.1 | 101 | 25.1 | 55 | ||

| basic | 26.4 | 42 | 48.4 | 77 | 25.2 | 40 | basic | 34.7 | 60 | 46.8 | 81 | 18.5 | 32 | ||

| secondary | 23.0 | 92 | 51.3 | 205 | 25.8 | 103 | secondary | 34.5 | 134 | 41.8 | 162 | 23.7 | 92 | ||

| college degree | 28.3 | 115 | 42.3 | 172 | 29.5 | 120 | college degree | 36.5 | 163 | 33.3 | 149 | 30.2 | 135 | ||

| masters or phd | 65.4 | 17 | 15.4 | 4 | 19.2 | 5 | masters or phd | 60.6 | 20 | 27.3 | 9 | 12.1 | 4 | ||

| Gender | Gender | ||||||||||||||

| female | 22.3 | 139 | 46.0 | 287 | 31.7 | 198 | <0.001 | female | 31.8 | 191 | 39.0 | 234 | 29.2 | 175 | <0.001 |

| male | 26.0 | 191 | 48.4 | 355 | 25.6 | 188 | male | 34.4 | 275 | 42.4 | 339 | 23.2 | 185 | ||

| Occupation | Occupation | ||||||||||||||

| agricultural | 15.7 | 19 | 55.4 | 67 | 28.9 | 35 | <0.001 | agricultural | 25.2 | 37 | 49.7 | 73 | 25.2 | 37 | <0.001 |

| educational | 27.9 | 56 | 40.8 | 82 | 31.3 | 63 | educational | 42.3 | 102 | 31.1 | 75 | 26.6 | 64 | ||

| housewife | 20.1 | 65 | 48.5 | 157 | 31.5 | 102 | housewife | 30.5 | 85 | 43.7 | 122 | 25.8 | 72 | ||

| office | 33.1 | 57 | 47.7 | 82 | 19.2 | 33 | office | 40.1 | 67 | 32.9 | 55 | 27.0 | 45 | ||

| student | 26.9 | 52 | 43.5 | 84 | 29.5 | 57 | student | 28.5 | 51 | 42.5 | 76 | 29.1 | 52 | ||

| unemployed | 14.0 | 13 | 53.8 | 50 | 32.3 | 30 | unemployed | 26.6 | 21 | 48.1 | 38 | 25.3 | 20 | ||

| handicraft | 20.8 | 27 | 56.2 | 73 | 23.1 | 30 | handicraft | 32.8 | 65 | 47.5 | 94 | 19.7 | 39 | ||

| other | 33.1 | 41 | 37.9 | 47 | 29.0 | 36 | other | 34.9 | 38 | 36.7 | 40 | 28.4 | 31 | ||

| Likley to become sick with COVID-19 | Likley to become sick with COVID-19 | ||||||||||||||

| I don’t know | 22.6 | 125 | 38.5 | 213 | 38.9 | 215 | <0.001 | I don’t know | 21.7 | 110 | 43.3 | 219 | 35.0 | 177 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 29.3 | 164 | 49.1 | 275 | 21.6 | 121 | Yes | 44.7 | 306 | 36.5 | 250 | 18.8 | 129 | ||

| No | 16.7 | 41 | 62.9 | 154 | 20.4 | 50 | No | 24.0 | 50 | 50.0 | 104 | 26.0 | 54 | ||

| Public Health and Social Measures over the last 10 months | Willing | Not willing | Not sure | Public Health and Social Measures over the last 10 months | Willing | Not willing | Not sure | ||||||||

| Practiced social distancing | % | number | % | number | % | number | chi2 p-value | Practiced social distancing | % | number | % | number | % | number | chi2 p-value |

| No | 20.7 | 189 | 50.9 | 464 | 28.4 | 259 | <0.001 | No | 32.8 | 289 | 44.0 | 388 | 23.2 | 205 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 31.6 | 141 | 39.9 | 178 | 28.5 | 127 | Yes | 34.2 | 177 | 35.8 | 185 | 30.0 | 155 | ||

| Worn a mask | Worn a mask | ||||||||||||||

| No | 14.5 | 74 | 57.0 | 292 | 28.5 | 146 | <0.001 | No | 23.4 | 94 | 48.3 | 194 | 28.4 | 114 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 30.3 | 256 | 41.4 | 350 | 28.4 | 240 | Yes | 37.3 | 372 | 38.0 | 379 | 24.7 | 246 | ||

| Stayed away from the mosque | Stayed away from the mosque | ||||||||||||||

| No | 23.6 | 281 | 48.7 | 580 | 27.8 | 331 | <0.001 | No | 32.7 | 372 | 42.1 | 479 | 25.2 | 286 | 0.2 |

| Yes | 29.5 | 49 | 37.4 | 62 | 33.1 | 55 | Yes | 35.9 | 94 | 35.9 | 94 | 28.2 | 74 | ||

| Wash hands | |||||||||||||||

| No | 20.4 | 62 | 56.3 | 171 | 23.4 | 71 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 36.9 | 404 | 36.7 | 402 | 26.4 | 289 | |||||||||

| Avoided social gatherings | Avoided social gatherings | ||||||||||||||

| No | 19.9 | 140 | 54.7 | 384 | 25.4 | 178 | <0.001 | No | 32.9 | 276 | 43.8 | 367 | 23.3 | 195 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 29.0 | 190 | 39.3 | 258 | 31.7 | 208 | Yes | 33.9 | 190 | 36.7 | 206 | 29.4 | 165 | ||

| Public Health and Social Measures over the last 4 weeks | Willing | Not willing | Not sure | Public Health and Social Measures over the last 4 weeks | Willing | Not willing | Not sure | ||||||||

| Practiced social distancing | % | number | % | number | % | number | chi2 p-value | Practiced social distancing | % | number | % | number | % | number | chi2 p-value |

| No | 21.2 | 234 | 49.3 | 543 | 29.5 | 325 | <0.001 | No | 32.4 | 405 | 41.8 | 523 | 25.9 | 324 | 0.1 |

| Yes | 37.5 | 96 | 38.7 | 99 | 23.8 | 61 | Yes | 41.5 | 61 | 34.0 | 50 | 24.5 | 36 | ||

| Worn a mask | Worn a mask | ||||||||||||||

| No | 20.2 | 185 | 52.0 | 475 | 27.8 | 254 | <0.001 | No | 26.1 | 227 | 44.7 | 388 | 29.2 | 254 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 32.7 | 145 | 37.6 | 167 | 29.7 | 132 | Yes | 45.1 | 239 | 34.9 | 185 | 20.0 | 106 | ||

| Stayed away from the mosque | Stayed away from the mosque | ||||||||||||||

| No | 23.9 | 312 | 47.6 | 621 | 28.5 | 371 | <0.001 | No | 33.1 | 454 | 41.0 | 562 | 25.9 | 355 | 0.5 |

| Yes | 33.3 | 18 | 38.9 | 21 | 27.8 | 15 | Yes | 42.9 | 12 | 39.3 | 11 | 17.9 | 5 | ||

| Washed hands | |||||||||||||||

| No | 21.1 | 148 | 50.0 | 350 | 28.9 | 202 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 45.5 | 318 | 31.9 | 223 | 22.6 | 158 | |||||||||

| Avoided social gatherings | Avoided social gatherings | ||||||||||||||

| No | 22.2 | 232 | 50.2 | 525 | 27.6 | 289 | <0.001 | No | 32.2 | 404 | 42.8 | 537 | 25.1 | 315 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 31.4 | 98 | 37.5 | 117 | 31.1 | 97 | Yes | 43.4 | 62 | 25.2 | 36 | 31.5 | 45 | ||

Table A2.

Round 3 and Round 4, vaccination status and knowledge regarding COVID-19.

| Round 3 | Round 4 | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Willing | Not Willing | Not Sure | Willing | Not Willing | Not Sure | ||||||||||

| Knowledge to protect yourself from the virus | % | number | % | number | % | number | chi2 p-value | Knowledge to protect yourself from the virus | % | number | % | number | % | number | chi2 p-value |

| No knowledge | 6.0 | 4 | 67.2 | 45 | 26.9 | 18 | <0.001 | No knowledge | 3.7 | 1 | 59.3 | 16 | 37.0 | 10 | <0.001 |

| needs improvement | 18.1 | 89 | 53.3 | 262 | 28.7 | 141 | needs improvement | 25.7 | 83 | 48.3 | 156 | 26.0 | 84 | ||

| good | 25.9 | 133 | 45.3 | 233 | 28.8 | 148 | good | 36.3 | 224 | 41.8 | 258 | 22.0 | 136 | ||

| very good | 32.5 | 53 | 42.3 | 69 | 25.2 | 41 | very good | 33.6 | 86 | 35.2 | 90 | 31.3 | 80 | ||

| excellent | 41.8 | 51 | 27.1 | 33 | 31.2 | 38 | excellent | 41.1 | 72 | 30.3 | 53 | 28.6 | 50 | ||

| Trust in the official information from the authorities | Trust in the official information from the authorities | ||||||||||||||

| No confidence | 9.0 | 30 | 67.5 | 226 | 23.6 | 79 | <0.001 | No confidence | 23.3 | 49 | 47.1 | 99 | 29.5 | 62 | <0.001 |

| little confidence | 26.0 | 127 | 42.3 | 207 | 31.7 | 155 | little confidence | 35.6 | 159 | 44.1 | 197 | 20.4 | 91 | ||

| confident | 33.1 | 114 | 42.4 | 146 | 24.4 | 84 | confident | 35.2 | 162 | 38.0 | 175 | 26.7 | 123 | ||

| total confidence | 47.1 | 41 | 24.1 | 21 | 28.7 | 25 | total confidence | 39.9 | 63 | 29.8 | 47 | 30.4 | 48 | ||

| Trust in the ability of the health authorties to deal with the virus | Trust in the ability of the health authorties to deal with the virus | ||||||||||||||

| No confidence | 16.0 | 57.2 | 26.7 | 0.0 | No confidence | 28.9 | 41.2 | 29.9 | 0.0 | ||||||

| little confidence | 28.6 | 41.2 | 30.2 | little confidence | 38.9 | 41.4 | 19.8 | ||||||||

| confident | 34.6 | 42.7 | 22.8 | confident | 41.5 | 44.0 | 24.6 | ||||||||

| total confidence | 56.8 | 16.2 | 27.0 | total confidence | 39.5 | 35.5 | 25.0 | ||||||||

| Trust in your own ability to deal with the virus | Trust in your own ability to deal with the virus | ||||||||||||||

| No confidence | 17.6 | 49 | 51.8 | 144 | 30.6 | 85 | <0.001 | No confidence | 26.8 | 125 | 45.9 | 178 | 27.3 | 129 | <0.001 |

| little confidence | 22.6 | 110 | 46.6 | 227 | 30.8 | 150 | little confidence | 32.4 | 185 | 38.9 | 197 | 28.7 | 94 | ||

| confident | 31.0 | 119 | 48.2 | 185 | 20.8 | 80 | confident | 35.1 | 78 | 43.4 | 109 | 21.5 | 61 | ||

| total confidence | 30.6 | 34 | 33.3 | 37 | 36.0 | 40 | total confidence | 42.1 | 30 | 32.8 | 27 | 25.1 | 19 | ||

| How dangerous do you think the COVID-19 virus is | How dangerous do you think the COVID-19 virus is | ||||||||||||||

| it is not dangerous | 7.9 | 14 | 74.7 | 133 | 17.4 | 31 | <0.001 | it is not dangerous | 9.2 | 12 | 62.6 | 82 | 28.2 | 37 | <0.001 |

| more or less dangerous | 17.6 | 62 | 50.1 | 177 | 32.3 | 114 | more or less dangerous | 37.2 | 197 | 44.6 | 236 | 18.2 | 96 | ||

| very dangerous | 32.4 | 253 | 38.7 | 302 | 28.9 | 226 | very dangerous | 35.7 | 255 | 33.9 | 242 | 30.5 | 218 | ||

Table A3.

Round 3 and Round 4, vaccination status and COVID-19 vaccine beliefs.

| Willing | Not Willing | Not Sure | Willing | Not Willing | Not Sure | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccine is effective | % | number | % | number | % | number | chi2 p-value | Vaccine is effective | % | number | % | number | % | number | chi2 p-value |

| No | 17.6 | 127 | 53.6 | 386 | 28.8 | 207 | <0.001 | No | 13.6 | 85 | 52.3 | 327 | 34.1 | 213 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 61.5 | 153 | 18.1 | 45 | 20.5 | 51 | Yes | 58.1 | 370 | 26.5 | 169 | 15.4 | 98 | ||

| Vaccine has side effects | Vaccine has side effects | ||||||||||||||

| No | 39.4 | 227 | 29.7 | 171 | 30.9 | 178 | <0.001 | No | 52.8 | 318 | 27.4 | 165 | 19.8 | 119 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 13.5 | 53 | 66.2 | 260 | 20.4 | 80 | Yes | 20.8 | 137 | 50.2 | 331 | 29.1 | 192 | ||

Table A4.

Round 3 and Round 4, vaccination status and most trusted COVID-19 information source.

| Round 3 | Round 4 | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Most Trusted Source | Willing | Not Willing | Not Sure | Most Trusted Source | Willing | Not Willing | Not Sure | ||||||||

| % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | chi2 p-value | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | chi2 p-value | ||

| TV | TV | ||||||||||||||

| first mention | 26.4 | 139 | 45.4 | 239 | 28.1 | 148 | <0.001 | first mention | 37.1 | 275 | 41.5 | 308 | 21.4 | 159 | <0.001 |

| second mention | 30.0 | 76 | 44.7 | 113 | 25.3 | 64 | second mention | 23.3 | 31 | 47.4 | 63 | 29.3 | 39 | ||

| third mention | 22.6 | 14 | 32.3 | 20 | 45.2 | 28 | third mention | 34.3 | 12 | 25.7 | 9 | 40.0 | 14 | ||

| Radio | Radio | ||||||||||||||

| first mention | 25.8 | 67 | 43.9 | 114 | 30.4 | 79 | 0.2 | first mention | 33.3 | 47 | 37.6 | 53 | 29.1 | 41 | 0.8 |

| second mention | 37.0 | 27 | 34.3 | 25 | 28.8 | 21 | second mention | 32.5 | 13 | 32.5 | 13 | 35.0 | 14 | ||

| third mention | 31.8 | 14 | 31.8 | 14 | 36.4 | 16 | third mention | 28.0 | 7 | 48.0 | 12 | 24.0 | 6 | ||

| first mention | 24.5 | 26 | 46.2 | 49 | 29.3 | 31 | 0.8 | first mention | 36.7 | 62 | 33.1 | 56 | 30.2 | 51 | 0.1 |

| second mention | 29.6 | 29 | 48.0 | 47 | 22.5 | 22 | second mention | 25.2 | 34 | 49.6 | 67 | 25.2 | 34 | ||

| third mention | 28.0 | 30 | 47.7 | 51 | 24.3 | 26 | third mention | 27.3 | 12 | 43.2 | 19 | 29.6 | 13 | ||

| Social media | Social media | ||||||||||||||

| first mention | 28.9 | 26 | 41.1 | 37 | 30.0 | 27 | 0.6 | first mention | 32.3 | 41 | 39.4 | 50 | 28.4 | 36 | 0.9 |

| second mention | 29.0 | 27 | 50.5 | 47 | 20.4 | 19 | second mention | 32.4 | 33 | 34.3 | 35 | 33.3 | 34 | ||

| third mention | 29.0 | 27 | 44.1 | 41 | 26.9 | 25 | third mention | 29.8 | 28 | 40.4 | 38 | 29.8 | 28 | ||

| Communication materials | |||||||||||||||

| first mention | 36.4 | 28 | 35.1 | 27 | 28.6 | 22 | 0.9 | ||||||||

| second mention | 31.5 | 28 | 37.1 | 33 | 31.5 | 28 | |||||||||

| third mention | 29.1 | 16 | 36.4 | 20 | 34.6 | 19 | |||||||||

| Health unit | Health unit | ||||||||||||||

| first mention | 24.8 | 31 | 37.6 | 47 | 37.6 | 47 | <0.001 | first mention | 22.5 | 22 | 52.0 | 51 | 25.5 | 25 | 0.1 |

| second mention | 23.0 | 14 | 59.0 | 36 | 18.0 | 11 | second mention | 37.7 | 26 | 33.3 | 23 | 29.0 | 20 | ||

| third mention | 34.0 | 16 | 27.7 | 13 | 38.3 | 18 | third mention | 30.8 | 12 | 38.5 | 15 | 30.8 | 12 | ||

| Family | Family | ||||||||||||||

| first mention | 22.2 | 20 | 40.0 | 36 | 37.8 | 34 | 0.7 | first mention | 19.6 | 27 | 46.4 | 64 | 34.1 | 47 | 0.1 |

| second mention | 18.7 | 14 | 46.7 | 35 | 34.7 | 26 | second mention | 23.5 | 20 | 48.2 | 41 | 28.2 | 24 | ||

| third mention | 26.9 | 18 | 41.8 | 28 | 31.3 | 21 | third mention | 8.1 | 3 | 67.6 | 25 | 24.3 | 9 | ||

| Friends | Friends | ||||||||||||||

| first mention | 26.8 | 15 | 44.6 | 25 | 28.6 | 16 | 0.4 | first mention | 25.3 | 21 | 43.4 | 36 | 31.3 | 26 | 1.0 |

| second mention | 27.4 | 17 | 43.6 | 27 | 29.0 | 18 | second mention | 26.8 | 22 | 46.3 | 38 | 26.8 | 22 | ||

| third mention | 16.0 | 12 | 45.3 | 34 | 38.7 | 29 | third mention | 19.4 | 6 | 51.6 | 16 | 29.0 | 9 | ||

| Community health workers | Community health workers | ||||||||||||||

| first mention | 29.6 | 37 | 48.0 | 60 | 22.4 | 28 | <0.001 | first mention | 32.0 | 47 | 41.5 | 61 | 26.5 | 39 | 0.5 |

| second mention | 23.2 | 19 | 40.2 | 33 | 36.6 | 30 | second mention | 36.8 | 32 | 35.6 | 31 | 27.6 | 24 | ||

| third mention | 46.5 | 20 | 27.9 | 12 | 25.6 | 11 | third mention | 45.8 | 22 | 31.3 | 15 | 22.9 | 11 | ||

| Volunteers | Volunteers | ||||||||||||||

| first mention | 34.7 | 42 | 41.3 | 50 | 24.0 | 29 | 0.2 | first mention | 34.2 | 27 | 34.2 | 27 | 31.7 | 25 | 0.3 |

| second mention | 22.6 | 14 | 54.8 | 34 | 22.6 | 14 | second mention | 33.3 | 19 | 36.8 | 21 | 29.8 | 17 | ||

| third mention | 39.2 | 20 | 33.3 | 17 | 27.5 | 14 | third mention | 50.0 | 20 | 20.0 | 8 | 30.0 | 12 | ||

| Community leaders | Community leaders | ||||||||||||||

| first mention | 27.6 | 8 | 34.5 | 10 | 37.9 | 11 | 0.3 | first mention | 25.0 | 7 | 50.0 | 14 | 25.0 | 7 | 0.2 |

| second mention | 10.0 | 3 | 43.3 | 13 | 46.7 | 14 | second mention | 47.8 | 11 | 34.8 | 8 | 17.4 | 4 | ||

| third mention | 18.0 | 9 | 50.0 | 25 | 32.0 | 16 | third mention | 18.8 | 3 | 37.5 | 6 | 43.8 | 7 | ||

| Religious leaders | Religious leaders | ||||||||||||||

| first mention | 20.6 | 20 | 43.3 | 42 | 36.1 | 35 | 0.1 | first mention | 24.7 | 40 | 47.5 | 77 | 27.8 | 45 | 0.6 |

| second mention | 20.0 | 14 | 57.1 | 40 | 22.9 | 16 | second mention | 29.7 | 11 | 43.2 | 16 | 27.0 | 10 | ||

| third mention | 28.1 | 23 | 50.0 | 41 | 22.0 | 18 | third mention | 28.4 | 23 | 37.0 | 30 | 34.6 | 28 | ||

| Traditional healers | Traditional healers | ||||||||||||||

| first mention | 7.1 | 1 | 28.6 | 4 | 64.3 | 9 | <0.001 | first mention | 22.2 | 2 | 44.4 | 4 | 33.3 | 3 | 0.2 |

| second mention | 0.0 | 0 | 87.5 | 7 | 12.5 | 1 | second mention | 12.5 | 2 | 75.0 | 12 | 12.5 | 2 | ||

| third mention | 20.8 | 5 | 41.7 | 10 | 37.5 | 9 | third mention | 38.9 | 7 | 33.3 | 6 | 27.8 | 5 | ||

| A person from the community | A person from the community | ||||||||||||||

| first mention | 0.0 | 0 | 50.0 | 3 | 50.0 | 3 | <0.001 | first mention | 25.0 | 4 | 56.3 | 9 | 18.8 | 3 | 0.7 |

| second mention | 0.0 | 0 | 100.0 | 6 | 0.0 | 0 | second mention | 18.2 | 2 | 72.7 | 8 | 9.1 | 1 | ||

| third mention | 31.3 | 10 | 25.0 | 8 | 43.8 | 14 | third mention | 20.7 | 6 | 51.7 | 15 | 27.6 | 8 | ||

Table A5.

Correlates of vaccination status: not vaccinated and willing.

| Logistic Regression | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Willing to Get Vaccinated | Odds Ratios | St. Err. | t-Value | p-Value | [95% Conf | Interval] | Sig |

| Age (relative to under 20) | |||||||

| 21 to 30 | 1.176 | 0.387 | 0.49 | 0.622 | 0.617 | 2.241 | |

| 31 to 40 | 1.081 | 0.415 | 0.20 | 0.840 | 0.509 | 2.294 | |

| 41 to 50 | 0.871 | 0.352 | −0.34 | 0.733 | 0.395 | 1.923 | |

| 51 to 60 | 0.916 | 0.438 | −0.18 | 0.855 | 0.359 | 2.338 | |

| 61 to 70 | 1.011 | 0.674 | 0.02 | 0.986 | 0.274 | 3.732 | |

| 71 and above | 2.854 | 2.239 | 1.34 | 0.181 | 0.613 | 13.278 | |

| Education (relative to cannot read and write) | |||||||

| Can read and write | 0.646 | 0.319 | −0.89 | 0.376 | 0.245 | 1.702 | |

| Basic | 0.939 | 0.477 | −0.13 | 0.901 | 0.347 | 2.540 | |

| Secondary | 0.865 | 0.432 | −0.29 | 0.771 | 0.324 | 2.304 | |

| College degree | 1.256 | 0.655 | 0.44 | 0.661 | 0.452 | 3.490 | |

| Masters of PhD | 2.887 | 1.791 | 1.71 | 0.088 | 0.855 | 9.742 | * |

| Gender (relative to female) | |||||||

| Male | 2.672 | 0.762 | 3.45 | 0.001 | 1.529 | 4.671 | *** |

| Occupation (relative to agriculture) | |||||||

| Education | 1.114 | 0.537 | 0.23 | 0.822 | 0.433 | 2.866 | |

| Housewife | 1.838 | 0.918 | 1.22 | 0.223 | 0.690 | 4.894 | |

| Office | 0.607 | 0.288 | −1.05 | 0.293 | 0.239 | 1.539 | |

| Student | 1.458 | 0.695 | 0.79 | 0.429 | 0.573 | 3.711 | |

| Unemployed | 1.172 | 0.732 | 0.25 | 0.800 | 0.344 | 3.989 | |

| Handicraft | 0.893 | 0.371 | −0.27 | 0.786 | 0.396 | 2.017 | |

| Other | 0.847 | 0.441 | −0.32 | 0.749 | 0.306 | 2.348 | |

| Likely to become sick with COVID-19 (relative to do not know) | |||||||

| Yes | 1.099 | 0.219 | 0.47 | 0.637 | 0.743 | 1.624 | |

| No | 1.007 | 0.333 | 0.02 | 0.984 | 0.526 | 1.925 | |

| Practised social distancing in the last 10 months | 1.478 | 0.361 | 1.60 | 0.110 | 0.916 | 2.386 | |

| Wore face mask in the last ten months | 0.872 | 0.238 | −0.50 | 0.616 | 0.511 | 1.488 | |

| Stayed away from mosque in the last ten months | 1.422 | 0.403 | 1.24 | 0.214 | 0.816 | 2.479 | |

| Washed hands in the last ten months | 2.931 | 0.953 | 3.31 | 0.001 | 1.550 | 5.542 | *** |

| Avoided social events in the last ten months | 1.097 | 0.261 | 0.39 | 0.699 | 0.688 | 1.749 | |

| Practised social distancing in the last four weeks | 1.148 | 0.515 | 0.31 | 0.759 | 0.476 | 2.767 | |

| Wore face mask in the last four weeks | 0.829 | 0.271 | −0.57 | 0.567 | 0.437 | 1.573 | |

| Stayed away from mosque in the last four weeks | 0.912 | 0.476 | −0.17 | 0.861 | 0.328 | 2.538 | |

| Washed hands in the last four weeks | 0.540 | 0.143 | −2.33 | 0.020 | 0.321 | 0.906 | ** |

| Avoided social events in the last four weeks | 1.736 | 0.641 | 1.50 | 0.135 | 0.842 | 3.579 | |

| Trust in the official information (relative to no trust) | |||||||

| Little confidence | 0.764 | 0.327 | −0.63 | 0.530 | 0.330 | 1.768 | |

| Confident | 1.532 | 0.682 | 0.96 | 0.338 | 0.640 | 3.668 | |

| Total confidence | 2.118 | 1.050 | 1.51 | 0.130 | 0.802 | 5.595 | |

| Trust in your own ability to deal with the virus (relative to no trust) | 1.000 | ||||||

| Little confidence | 1.074 | 0.328 | 0.23 | 0.814 | 0.591 | 1.954 | |

| Confident | 1.362 | 0.444 | 0.95 | 0.344 | 0.719 | 2.580 | |

| Total confidence | 1.156 | 0.599 | 0.28 | 0.780 | 0.419 | 3.190 | |

| The virus is dangerous (relative to it is not) | 1.000 | ||||||

| More or less dangerous | 4.742 | 2.512 | 2.94 | 0.003 | 1.679 | 13.391 | *** |

| Very dangerous | 14.233 | 7.662 | 4.93 | 0.000 | 4.955 | 40.883 | *** |

| Other | 22.195 | 29.773 | 2.31 | 0.021 | 1.601 | 307.662 | ** |

| Vaccine is effective | 6.799 | 1.684 | 7.74 | 0.000 | 4.184 | 11.049 | *** |

| Vaccine has side effects | 0.162 | 0.031 | −9.52 | 0.000 | 0.111 | 0.235 | *** |

| Constant | 0.006 | 0.006 | −5.29 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.039 | *** |

| Mean dependent var | 0.320 | SD dependent var | 0.467 | ||||

| Pseudo r-squared | 0.333 | Number of obs | 1128.000 | ||||

| Chi-square | 209.738 | Prob > chi2 | 0.000 | ||||

| Akaike crit. (AIC) | 1029.857 | Bayesian crit. (BIC) | 1246.070 | ||||

*** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

Table A6.

Correlates of vaccination status: not vaccinated and unwilling.

| Logistic Regression | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Vaccinated and Not Willing | Odds Ratios | St. Err. | t-Value | p-Value | [95% Conf | Interval] | Sig |

| Age (relative to under 20) | 1.000 | ||||||

| 21 to 30 | 1.017 | 0.340 | 0.05 | 0.960 | 0.528 | 1.958 | |

| 31 to 40 | 1.066 | 0.405 | 0.17 | 0.865 | 0.507 | 2.244 | |

| 41 to 50 | 1.058 | 0.418 | 0.14 | 0.887 | 0.488 | 2.294 | |

| 51 to 60 | 1.278 | 0.551 | 0.57 | 0.570 | 0.548 | 2.976 | |

| 61 to 70 | 0.891 | 0.584 | −0.18 | 0.860 | 0.246 | 3.223 | |

| 71 and above | 0.790 | 0.691 | −0.27 | 0.787 | 0.142 | 4.389 | |

| Education (relative to cannot read and write) | 1.000 | ||||||

| Can read and write | 0.948 | 0.353 | −0.14 | 0.887 | 0.457 | 1.968 | |

| Basic | 0.751 | 0.295 | −0.73 | 0.466 | 0.347 | 1.623 | |

| Secondary | 0.810 | 0.307 | −0.56 | 0.579 | 0.385 | 1.704 | |

| College degree | 0.700 | 0.287 | −0.87 | 0.384 | 0.314 | 1.563 | |

| Masters of PhD | 0.611 | 0.305 | −0.99 | 0.323 | 0.230 | 1.624 | |

| Gender (relative to female) | 1.000 | ||||||

| Male | 0.587 | 0.123 | −2.54 | 0.011 | 0.389 | 0.886 | ** |

| Occupation (relative to agriculture) | 1.000 | ||||||

| Education | 0.667 | 0.249 | −1.08 | 0.278 | 0.321 | 1.385 | |

| Housewife | 0.583 | 0.213 | −1.48 | 0.140 | 0.285 | 1.193 | |

| Office | 0.973 | 0.353 | −0.07 | 0.940 | 0.478 | 1.980 | |

| Student | 0.652 | 0.257 | −1.08 | 0.278 | 0.300 | 1.413 | |

| Unemployed | 0.594 | 0.258 | −1.20 | 0.230 | 0.254 | 1.390 | |

| Handicraft | 0.929 | 0.276 | −0.25 | 0.805 | 0.519 | 1.664 | |

| Other | 0.678 | 0.282 | −0.94 | 0.350 | 0.300 | 1.531 | |

| Likely to become sick with COVID-19 (relative to do not know) | 1.000 | ||||||

| Yes | 1.109 | 0.184 | 0.62 | 0.533 | 0.801 | 1.535 | |

| No | 1.562 | 0.392 | 1.78 | 0.076 | 0.955 | 2.556 | * |

| Practised social distancing in the last 10 months | 0.750 | 0.146 | −1.48 | 0.139 | 0.512 | 1.098 | |

| Wore face mask in the last ten months | 0.989 | 0.206 | −0.05 | 0.959 | 0.658 | 1.487 | |

| Stayed away from mosque in the last ten months | 1.027 | 0.243 | 0.11 | 0.909 | 0.647 | 1.632 | |

| Washed hands in the last ten months | 0.552 | 0.125 | −2.63 | 0.008 | 0.354 | 0.859 | *** |

| Avoided social events in the last ten months | 0.674 | 0.119 | −2.24 | 0.025 | 0.478 | 0.952 | ** |

| Practised social distancing in the last four weeks | 1.782 | 0.791 | 1.30 | 0.193 | 0.747 | 4.252 | |

| Wore face mask in the last four weeks | 0.764 | 0.195 | −1.05 | 0.292 | 0.463 | 1.261 | |

| Stayed away from mosque in the last four weeks | 1.963 | 1.043 | 1.27 | 0.204 | 0.693 | 5.559 | |

| Washed hands in the last four weeks | 1.224 | 0.248 | 1.00 | 0.319 | 0.823 | 1.820 | |

| Avoided social events in the last four weeks | 0.448 | 0.180 | −2.00 | 0.046 | 0.203 | 0.985 | ** |

| Trust in the official information (relative to no trust) | 1.000 | ||||||

| Little confidence | 0.795 | 0.223 | −0.82 | 0.414 | 0.459 | 1.378 | |

| Confident | 0.611 | 0.174 | −1.73 | 0.084 | 0.349 | 1.068 | * |

| Total confidence | 0.593 | 0.217 | −1.43 | 0.154 | 0.290 | 1.215 | |

| Trust in your own ability to deal with the virus (relative to no trust) | 1.000 | ||||||

| Little confidence | 1.035 | 0.217 | 0.17 | 0.869 | 0.686 | 1.562 | |

| Confident | 0.873 | 0.203 | −0.58 | 0.559 | 0.553 | 1.378 | |

| Total confidence | 0.873 | 0.361 | −0.33 | 0.742 | 0.388 | 1.964 | |

| The virus is dangerous (relative to it is not) | 1.000 | ||||||

| More or less dangerous | 0.457 | 0.104 | −3.44 | 0.001 | 0.293 | 0.715 | *** |

| Very dangerous | 0.244 | 0.057 | −6.00 | 0.000 | 0.154 | 0.387 | *** |

| Other | 0.191 | 0.198 | −1.60 | 0.110 | 0.025 | 1.453 | |

| Vaccine is effective | 0.484 | 0.084 | −4.19 | 0.000 | 0.345 | 0.680 | *** |

| Vaccine has side effects | 1.444 | 0.235 | 2.26 | 0.024 | 1.050 | 1.986 | ** |

| Constant | 10.067 | 6.770 | 3.43 | 0.001 | 2.694 | 37.610 | *** |

| Mean dependent var | 0.362 | SD dependent var | 0.481 | ||||

| Pseudo r-squared | 0.150 | Number of obs | 1128.000 | ||||

| Chi-square | 170.972 | Prob > chi2 | 0.000 | ||||

| Akaike crit. (AIC) | 1340.615 | Bayesian crit. (BIC) | 1556.828 | ||||

*** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

Table A7.

Correlates of vaccination status: not vaccinated and not decided.

| Logistic Regression | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Vaccinated and Not Decided | Odds Ratios | St. Err. | t-Value | p-Value | [95% Conf | Interval] | Sig |

| Age (relative to under 20) | 1.000 | ||||||

| 21 to 30 | 0.976 | 0.303 | −0.08 | 0.937 | 0.531 | 1.792 | |

| 31 to 40 | 1.113 | 0.391 | 0.30 | 0.761 | 0.559 | 2.216 | |

| 41 to 50 | 1.191 | 0.435 | 0.48 | 0.633 | 0.582 | 2.438 | |

| 51 to 60 | 1.070 | 0.448 | 0.16 | 0.872 | 0.471 | 2.430 | |

| 61 to 70 | 1.412 | 0.932 | 0.52 | 0.602 | 0.387 | 5.151 | |

| 71 and above | 0.830 | 0.686 | −0.23 | 0.821 | 0.164 | 4.197 | |

| Education (relative to cannot read and write) | 1.000 | ||||||

| Can read and write | 1.777 | 0.718 | 1.42 | 0.155 | 0.804 | 3.924 | |

| Basic | 1.830 | 0.774 | 1.43 | 0.153 | 0.799 | 4.192 | |

| Secondary | 1.767 | 0.735 | 1.37 | 0.171 | 0.782 | 3.992 | |

| College degree | 1.633 | 0.724 | 1.10 | 0.269 | 0.684 | 3.894 | |

| Masters of PhD | 0.904 | 0.509 | −0.18 | 0.857 | 0.300 | 2.726 | |

| Gender (relative to female) | 1.000 | ||||||

| Male | 0.952 | 0.188 | −0.25 | 0.804 | 0.646 | 1.402 | |

| Occupation (relative to agriculture) | 1.000 | ||||||

| Education | 1.442 | 0.543 | 0.97 | 0.331 | 0.689 | 3.018 | |

| Housewife | 1.320 | 0.490 | 0.75 | 0.454 | 0.638 | 2.731 | |

| Office | 1.503 | 0.548 | 1.12 | 0.263 | 0.736 | 3.071 | |

| Student | 1.271 | 0.507 | 0.60 | 0.548 | 0.582 | 2.778 | |

| Unemployed | 1.637 | 0.765 | 1.05 | 0.292 | 0.655 | 4.089 | |

| Handicraft | 1.177 | 0.374 | 0.51 | 0.609 | 0.631 | 2.194 | |

| Other | 1.683 | 0.750 | 1.17 | 0.243 | 0.703 | 4.029 | |

| Likely to become sick with COVID-19 (relative to do not know) | 1.000 | ||||||

| Yes | 0.771 | 0.122 | −1.65 | 0.099 | 0.566 | 1.050 | * |

| No | 0.522 | 0.137 | −2.47 | 0.013 | 0.311 | 0.874 | ** |

| Practised social distancing in the last 10 months | 0.928 | 0.182 | −0.38 | 0.703 | 0.632 | 1.362 | |

| Wore face mask in the last ten months | 1.270 | 0.263 | 1.16 | 0.247 | 0.847 | 1.905 | |

| Stayed away from mosque in the last ten months | 0.790 | 0.201 | −0.93 | 0.352 | 0.480 | 1.299 | |

| Washed hands in the last ten months | 1.025 | 0.231 | 0.11 | 0.914 | 0.659 | 1.595 | |

| Avoided social events in the last ten months | 1.311 | 0.225 | 1.58 | 0.115 | 0.937 | 1.834 | |

| Practised social distancing in the last four weeks | 0.683 | 0.274 | −0.95 | 0.342 | 0.311 | 1.499 | |

| Wore face mask in the last four weeks | 1.348 | 0.339 | 1.19 | 0.234 | 0.824 | 2.206 | |

| Stayed away from mosque in the last four weeks | 0.258 | 0.204 | −1.71 | 0.087 | 0.055 | 1.218 | * |

| Washed hands in the last four weeks | 1.427 | 0.298 | 1.70 | 0.088 | 0.948 | 2.150 | * |

| Avoided social events in the last four weeks | 1.112 | 0.395 | 0.30 | 0.766 | 0.554 | 2.229 | |

| Trust in the official information (relative to no trust) | 1.000 | ||||||

| Little confidence | 1.613 | 0.465 | 1.66 | 0.097 | 0.917 | 2.839 | * |

| Confident | 1.361 | 0.395 | 1.06 | 0.289 | 0.770 | 2.405 | |

| Total confidence | 1.022 | 0.397 | 0.06 | 0.956 | 0.477 | 2.188 | |

| Trust in your own ability to deal with the virus (relative to no trust) | 1.000 | ||||||

| Little confidence | 0.909 | 0.194 | −0.45 | 0.656 | 0.598 | 1.382 | |

| Confident | 0.800 | 0.179 | −1.00 | 0.319 | 0.517 | 1.240 | |

| Total confidence | 1.131 | 0.497 | 0.28 | 0.780 | 0.477 | 2.678 | |

| The virus is dangerous (relative to it is not) | 1.000 | ||||||

| More or less dangerous | 1.813 | 0.437 | 2.47 | 0.014 | 1.131 | 2.907 | ** |

| Very dangerous | 1.334 | 0.330 | 1.17 | 0.243 | 0.822 | 2.166 | |

| Other | 1.919 | 1.850 | 0.68 | 0.499 | 0.290 | 12.695 | |

| Vaccine is effective | 0.539 | 0.097 | −3.42 | 0.001 | 0.378 | 0.768 | *** |

| Vaccine has side effects | 2.536 | 0.418 | 5.65 | 0.000 | 1.836 | 3.502 | *** |

| Constant | 0.072 | 0.049 | −3.90 | 0.000 | 0.019 | 0.270 | *** |

| Mean dependent var | 0.318 | SD dependent var | 0.466 | ||||

| Pseudo r-squared | 0.077 | Number of obs | 1128.000 | ||||

| Chi-square | 104.632 | Prob > chi2 | 0.000 | ||||

| Akaike crit. (AIC) | 1388.300 | Bayesian crit. (BIC) | 1604.513 | ||||

*** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

Table A8.

Vaccination status and PHSM (over the last ten months) over time, pooled analysis.

| Logistic Regression | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Willing to Vaccinate | Coef. | St. Err. | t-Value | p-Value | [95% Conf | Interval] | Sig |

| Practised social distancing in the last 10 months | 1.137 | 0.119 | 1.22 | 0.221 | 0.926 | 1.395 | |

| Wore face mask in the last 10 months | 1.942 | 0.215 | 6.00 | 0.000 | 1.563 | 2.413 | *** |

| Did not go to mosque in the last 10 months | 1.192 | 0.151 | 1.38 | 0.167 | 0.929 | 1.528 | |

| Avoided social events in the last 10 months | 0.905 | 0.087 | −1.04 | 0.300 | 0.749 | 1.093 | |

| Washed hands in the last 10 months | 1.910 | 0.244 | 5.08 | 0.000 | 1.488 | 2.452 | *** |

| Constant | 0.172 | 0.023 | −13.32 | 0.000 | 0.133 | 0.223 | *** |

| Mean dependent var | 0.307 | SD dependent var | 0.461 | ||||

| Pseudo r-squared | 0.035 | Number of obs | 2848.000 | ||||

| Chi-square | 113.752 | Prob > chi2 | 0.000 | ||||

| Akaike crit. (AIC) | 3404.417 | Bayesian crit. (BIC) | 3446.098 | ||||

| Not willing to vaccinate | Coef. | St. Err. | t-value | p-value | [95% Conf | Interval] | Sig |

| Practised social distancing in the last 10 months | 0.790 | 0.076 | −2.44 | 0.015 | 0.654 | 0.955 | ** |

| Wore face mask in the last 10 months | 0.622 | 0.059 | −5.04 | 0.000 | 0.517 | 0.748 | *** |

| Did not go to mosque in the last 10 months | 0.920 | 0.114 | −0.67 | 0.504 | 0.722 | 1.174 | |

| Avoided social events in the last 10 months | 0.914 | 0.083 | −0.99 | 0.321 | 0.765 | 1.092 | |

| Washed hands in the last 10 months | 0.504 | 0.053 | −6.55 | 0.000 | 0.411 | 0.619 | *** |

| Constant | 1.886 | 0.199 | 6.02 | 0.000 | 1.534 | 2.318 | *** |

| Mean dependent var | 0.410 | SD dependent var | 0.492 | ||||

| Pseudo r-squared | 0.036 | Number of obs | 2848.000 | ||||

| Chi-square | 128.242 | Prob > chi2 | 0.000 | ||||

| Akaike crit. (AIC) | 3733.355 | Bayesian crit. (BIC) | 3775.035 | ||||

| Undecided | Coef. | St. Err. | t-value | p-value | [95% Conf | Interval] | Sig |

| Practised social distancing in the last 10 months | 1.147 | 0.119 | 1.32 | 0.185 | 0.936 | 1.406 | |

| Wore face mask in the last 10 months | 0.952 | 0.099 | −0.47 | 0.635 | 0.776 | 1.167 | |

| Did not go to mosque in the last 10 months | 0.899 | 0.118 | −0.81 | 0.420 | 0.695 | 1.163 | |

| Avoided social events in the last 10 months | 1.218 | 0.117 | 2.05 | 0.040 | 1.009 | 1.470 | ** |

| Washed hands in the last 10 months | 1.305 | 0.155 | 2.24 | 0.025 | 1.034 | 1.647 | ** |

| Constant | 0.259 | 0.031 | −11.14 | 0.000 | 0.204 | 0.329 | *** |

| Mean dependent var | 0.283 | SD dependent var | 0.450 | ||||

| Pseudo r-squared | 0.007 | Number of obs | 2848.000 | ||||

| Chi-square | 22.641 | Prob > chi2 | 0.001 | ||||

| Akaike crit. (AIC) | 3382.133 | Bayesian crit. (BIC) | 3423.814 | ||||

*** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

Table A9.

Vaccination status and PHSM (over the last four weeks) over time, pooled analysis.

| Logistic Regression | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Willing to Vaccinate | Coef. | St. Err. | t-Value | p-Value | [95% Conf | Interval] | Sig |

| Practised social distancing in the last 4 weeks | 1.106 | 0.191 | 0.58 | 0.559 | 0.788 | 1.553 | |

| Wore face mask in the last 4 weeks | 1.665 | 0.181 | 4.68 | 0.000 | 1.345 | 2.061 | *** |

| Did not go to mosque in the last 4 weeks | 1.259 | 0.417 | 0.70 | 0.487 | 0.658 | 2.412 | |

| Avoided social events in the last 4 weeks | 1.227 | 0.206 | 1.22 | 0.223 | 0.883 | 1.706 | |

| Washed hands in the last 4 weeks | 1.871 | 0.199 | 5.88 | 0.000 | 1.518 | 2.305 | *** |

| Constant | 0.278 | 0.021 | −16.70 | 0.000 | 0.239 | 0.323 | *** |

| Mean dependent var | 0.307 | SD dependent var | 0.461 | ||||

| Pseudo r-squared | 0.050 | Number of obs | 2848.000 | ||||

| Chi-square | 166.834 | Prob > chi2 | 0.000 | ||||

| Akaike crit. (AIC) | 3351.825 | Bayesian crit. (BIC) | 3393.506 | ||||

| Unwilling to vaccinate | Coef. | St. Err. | t-value | p-value | [95% Conf | Interval] | Sig |

| Practised social distancing in the last 4 weeks | 0.924 | 0.159 | −0.46 | 0.646 | 0.659 | 1.295 | |

| Wore face mask in the last 4 weeks | 0.774 | 0.084 | −2.37 | 0.018 | 0.626 | 0.957 | ** |

| Did not go to mosque in the last 4 weeks | 1.463 | 0.486 | 1.15 | 0.252 | 0.763 | 2.804 | |

| Avoided social events in the last 4 weeks | 0.581 | 0.107 | −2.94 | 0.003 | 0.405 | 0.835 | *** |

| Washed hands in the last 4 weeks | 0.561 | 0.056 | −5.80 | 0.000 | 0.462 | 0.682 | *** |

| Constant | 1.058 | 0.072 | 0.83 | 0.407 | 0.926 | 1.209 | |

| Mean dependent var | 0.410 | SD dependent var | 0.492 | ||||

| Pseudo r-squared | 0.030 | Number of obs | 2848.000 | ||||