Abstract

The NS3-NS4A serine protease of hepatitis C virus (HCV) mediates four specific cleavages of the viral polyprotein and its activity is considered essential for the biogenesis of the HCV replication machinery. Despite extensive biochemical and structural characterization, the analysis of natural variants of this enzyme has been limited by the lack of an efficient replication system for HCV in cultured cells. We have recently described the generation of chimeric HCV-Sindbis viruses whose propagation depends on the NS3-NS4A catalytic activity. NS3-NS4A gene sequences were fused to the gene coding for the Sindbis virus structural polyprotein in such a way that processing of the chimeric polyprotein, nucleocapsid assembly, and production of infectious viruses required NS3-NS4A-mediated proteolysis (G. Filocamo, L. Pacini, and G. Migliaccio, J. Virol. 71:1417–1427, 1997). Here we report the use of these chimeric viruses to select and characterize active variants of the NS3-NS4A protease. Our original chimeric viruses displayed a temperature-sensitive phenotype and formed lysis plaques much smaller than those formed by wild-type (wt) Sindbis virus. By serially passaging these chimeric viruses on BHK cells, we have selected virus variants which formed lysis plaques larger than those produced by their progenitors and produced NS3-NS4A proteins different in size and/or sequence from those of the original viruses. Characterization of the selected protease variants revealed that all of the mutated proteases still efficiently processed the chimeric polyprotein in infected cells and also cleaved an HCV substrate in vitro. One of the selected proteases was expressed in a bacterial system and showed a catalytic efficiency comparable to that of the wt recombinant protease.

The major etiological agent of non-A, non-B hepatitis was identified in 1989 and named hepatitis C virus (HCV) (8, 23). Presently, it is estimated that approximately 1% of the human population is infected by HCV (42). Exposure to HCV results in an overt acute disease in only a small percentage of cases, while in most instances the virus establishes a chronic infection which causes liver inflammation and slowly progresses to liver failure and cirrhosis (24). In addition, seroepidemiological surveys have indicated an important role of HCV in the pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma (27). The absence of a protective vaccine and the limited efficacy of alpha interferon treatment (55) have raised considerable interest in developing alternative anti-HCV therapies.

The genetic organization of HCV is similar to that of flaviviruses and pestiviruses (9, 37), and therefore HCV was assigned to a separate genus of the family Flaviviridae (43). The HCV genome consists of a single-stranded RNA of about 9.5 kb in length encoding a precursor polyprotein of 3,010 to 3,033 amino acids (8, 9, 26, 50). Individual viral proteins are produced by proteolysis of the precursor: the putative structural proteins (C, E1, E2, and p7) span the amino-terminal third of the precursor and are generated by cleavages probably mediated by the endoplasmic reticulum signal peptidase (21, 44), and the remaining part of the precursor contains the nonstructural proteins (NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B), which presumably form the virus replication machinery and are released from the nascent precursor by two virus-encoded proteases. A zinc-dependent protease associated with NS2 and the N terminus of NS3 is responsible for the cleavage between NS2 and NS3 (16, 19, 39). A distinct serine protease located in the N-terminal domain of NS3 is responsible for proteolytic cleavages at the NS3/NS4A, NS4A/NS4B, NS4B/NS5A, and NS5A/NS5B junctions (3, 17, 52).

Substantial efforts have been devoted to the characterization of the HCV serine protease, which is contained within the amino-terminal 180 amino acids of NS3 (3, 13, 17, 20, 52). Although the NS3 protease domain possesses enzymatic activity, the 54-amino-acid NS4A protein is required for cleavage at the NS3/NS4A and NS4B/NS5A sites and increases cleavage efficiency at the NS4A/NS4B and NS5A/NS5B junctions (2, 14, 33, 51). The central domain of NS4A, encompassing amino acids 21 to 32, was shown to be sufficient for activation of the protease (30, 34, 46, 53). In transfected cells, NS3 and NS4A assemble into a stable heterodimeric complex whose formation requires both the amino-terminal and the central domains of NS4A, as well as about 30 amino acids at the amino terminus of NS3 (4, 14, 30, 34, 45, 51). The determination of the crystal structure of the NS3 protease domain uncomplexed and complexed with central domain of NS4A (29, 36, 56) has confirmed the characteristics of this enzyme predicted by molecular modelling and biochemical studies (12, 40). The enzyme adopts a chymotrypsin-like fold and features a tetrahedrally coordinated metal distal to the active site. The central domain of NS4A forms a β strand which contributes to the formation of an eight-stranded β barrel with the amino-terminal domain of NS3 and plays a significant role in stabilizing NS3. Thus, NS4A is considered an integral structural component of the enzyme. For this reason, we here refer to the HCV serine protease as the NS3-NS4A protease. This protease cleaves the viral polyprotein in a precise temporal order which is probably critical for virus replication: the NS3/NS4A cleavage is the first event and occurs only in cis, and this is followed by cleavage at the NS5A/NS5B, NS4A/NS4B, and NS4B/NS5A sites, which can also occur in trans (2, 14, 33). An additional peculiar feature of the protease domain of NS3 is that it is covalently attached to an RNA helicase possessing ATPase activity (18, 25, 28).

This overwhelming amount of data makes the NS3 protease an attractive candidate for developing effective HCV therapies. Indeed, several in vitro assay systems have been developed and are being used for the identification of specific inhibitors.

Protease inhibitors have proved to be good therapeutic agents in the case of the human immunodeficiency virus protease. However, the long-term clinical efficacy of these drugs is potentially limited by the existence of inhibitor-resistant protease variants which are found in untreated subjects and emerge both in vivo during treatment and during selection in culture (10, 22, 32). Apparently, the ability of the virus to produce inhibitor-resistant protease variants depends largely on the ability of the protease to tolerate substitutions in critical subsites. Thus, attempts to subvert viral resistance should take this feature in account and concentrate on the search for inhibitors active against a broad range of variants. These attempts greatly benefit from the possibility of using in vitro cell culture systems for the selection and characterization of virus variants with decreased sensitivity to inhibitors.

Sequence analysis of several HCV isolates indicates that there are multiple HCV genotypes and subtypes and that even in the same individual the virus exists as quasispecies (6, 47). Accordingly, a number of sequence differences are found in the portion of the genome encoding the NS3-NS4A protease. Only a few variants have been characterized biochemically, and these show similar kinetic parameters. On the other hand, the lack of an efficient in vitro infection system prevents a large-scale comparison of the different protease variants present in various HCV isolates and also precludes testing the sensitivities to inhibitors of the different variants in cell culture.

We have recently described the generation of stable Sindbis virus (SBV)-HCV chimeric viruses whose propagation depends on the activity of the serine protease of HCV (15). Here we report the use of these viruses as a genetic system for the identification of functional variants of the NS3-NS4A protease which could be used to identify and characterize protease variants with decreased sensitivity to inhibitors. Since there are no selective inhibitors of the NS3-NS4A protease presently available, we investigated whether variants of the NS3-NS4A protease could be selected in the absence of a specific selective pressure, taking advantage of the high rate of spontaneous mutations of the SBV replication machinery. We selected more-infectious virus mutants by serial passaging on BHK cells, and almost all of them produced an NS3-NS4A protease different from those encoded by the original chimeras. All of these mutant enzymes displayed a measurable activity when assayed in vitro and efficiently processed the chimeric polyprotein in infected cells. These results imply that HCV-SBV chimeric viruses can be used under the appropriate conditions of selective pressure as a surrogate system for the identification and characterization of inhibitor-resistant variants of the NS3-NS4A protease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Manipulation of nucleic acids and construction of recombinant plasmids.

cDNA fragments were cloned in the desired expression vectors by standard DNA protocols or by PCR amplification of the area of interest, using synthetic oligonucleotides with the appropriate restriction sites. PCR amplification was performed by the procedure of Barnes (1). Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out by inserting the mutations in the PCR primers. DNA fragments containing the desired mutations were sequenced and recloned in the appropriate vectors by using restriction sites flanking the mutations.

For cloning and analysis of the NS3-NS4A-coding regions from selected virus variants, BHK cells were infected with the indicated chimeric virus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1. After 20 h of incubation at 37°C, infected monolayers were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and total RNA was extracted as described previously (7). The NS3-NS4A-coding regions of the viral RNAs were retrotranscribed by using the antisense oligonucleotide SB24 (5′-GCCGAGCATGTTAAAGAATCCTCT-3′, complementary to nucleotides 25 to 48 of the SBV 26S RNA) and Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Gibco, BRL) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNAs were amplified by PCR for 16 cycles with oligonucleotides HCVG56 (5′-GGGTCTAGACTCATGGCGCCCATCACGGC-3′, corresponding to nucleotides 3396 to 3425 of the BK strain of HCV and containing an XbaI restriction site) and HCVG43 (5′-GAACAATGGCCGGCCTCCC-3′, complementary to nucleotides 5362 to 5381 of the BK strain of HCV and containing an FseI restriction site). Amplified cDNAs were digested with the appropriate restriction enzymes and ligated with the indicated vector DNA digested with the same endonucleases. The nucleotide sequence of each cDNA was determined by automated and/or manual sequencing of the purified PCR products and of at least two corresponding clones.

Plasmid pSIN-FL5wt was constructed by several subcloning steps and is identical to pSIN-Mut5wt (15) but contains HCV sequences from nucleotide 3411 to 5469 (amino acid residues 1027 to 1713). Plasmid pSIN-FL5SA is identical to pSIN-FL5wt except that the TCG triplet coding for serine 1165 of HCV was changed to GCG, coding for alanine.

Plasmids pSIN-Mutα and pSIN-Mutɛ are pSIN-FL5wt derivatives and differ from this plasmid only in the NS3-NS4A protease gene. For the construction of these plasmids, the NS3-NS4A cDNAs of mutants A (pSIN-Mutα) and E (pSIN-Mutɛ) were obtained as described above, digested with XbaI and FseI, and cloned in pSIN-FL5wt digested with the same enzymes.

Plasmid pT7-7MutA is a pT7-7(NS31027-1206) derivative (49). To construct this plasmid, the cDNA containing the protease gene of mutant A was amplified with primers SB25 (5′-CTGACTAATACTACAACACCACC-3′, corresponding to nucleotides 7621 to 7643 of the SBV 49S RNA) and HCVG55 (5′-TCGGCTAGCCTACTTTTTCTTGCCCTCTTCCATTTCATCGAACTC-3′, complementary to nucleotides 5441 to 5485 of the BK strain of HCV and containing three triplets coding for lysine, a stop codon, and an NheI restriction site) as described above, digested with NdeI and NheI, and cloned in pT7-7(NS31027-1206) digested with the same enzymes.

Plasmids used as templates for in vitro RNA synthesis were linearized with the appropriate restriction enzyme and transcribed in vitro with an SP6 mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Transcription efficiency was monitored by analysis of the RNAs on denaturing agarose gels, in comparison with known standards. Transcription mixtures were transfected in BHK cells by electroporation as described previously (15).

Virus infection and serial passaging.

Clone 21 BHK cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). BHK cells were routinely infected with the indicated viruses adequately diluted in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS. For serial passaging, viruses produced by cells electroporated with recombinant RNAs (passage I) were diluted in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS and used to infect BHK cells (106, plated in 10-cm-diameter tissue culture plates) at an MOI of less than or equal to 0.1 PFU per cell. After a 2-h binding period at 37°C, unbound viruses were removed and replaced with 10 ml of growth medium, and cells were incubated at either 30 or 37°C. Media containing progeny viruses (passage II) were collected between 2 and 5 days postinfection when the cytopathic effect was clearly detected, titrated on BHK cells, and used as inocula for the next passage (passage III), which was performed as described above. The infection cycle was repeated eight more times to yield passages IV to XI.

Plaque purification and propagation of purified viruses.

Passage IX (at 30 and 37°C) of Mut5 virus and passage XI (at 30 and 37°C) of FL5 virus were titrated by plaque assay on BHK cells. Eight well-separated plaques for each virus at each temperature were picked, diluted with 1.5 ml of DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, and used to infect BHK cells (105 per well, plated in six-well tissue culture plates) for 2 days at the relevant temperature. Viruses were amplified once more as described above (passage II), titrated on BHK cells, and used to infect BHK cells for preparation of detergent extracts or RNAs.

Antibodies and immunological techniques.

The rabbit polyclonal anti-SBV (R159/II) and anti-SBV C (3/6/82) antisera were raised against purified SBV and nucleocapsid, respectively. The rabbit polyclonal anti-NS3 (R37/V) and anti-NS4 (R39/V) antisera were raised against glutathione S-transferase–NS3 and TrpE-NS4 fusion proteins, respectively (52). The anti-NS3 rat monoclonal immunoglobulin G 46.D8 was raised against a purified NS3 protease fragment encompassing amino acids 1027 to 1206 of the HCV polyprotein (15). The anti-NS4A human monoclonal antibody D10.E6 was kindly provided by M. U. Mondelli and was obtained by immortalization of human B lymphocytes (38).

Plaque immunostaining and immunoblotting were performed as described previously (15). For metabolic labelling of viral proteins, BHK cells were infected with the indicated viruses at an MOI of less than 0.1 for 72 h at 30°C (FL5) or at an MOI of 1 for 16 h at 37°C (all other mutants) and then labelled with 35S-amino acids (Easytag, Amersham, United Kingdom) for 1 h at 37°C. Cell monolayers were washed once with PBS and lysed as follows. Lysis under denaturing conditions was performed by incubating the monolayers for 5 min at room temperature with 0.4 ml of immunoprecipitation buffer (20 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA) supplemented with 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). Lysates were passed several times through a 26-gauge needle to reduce viscosity, heated for 5 min at 95°C, diluted with immunoprecipitation buffer, and supplemented with Triton X-100 to adjust the final detergent concentrations to 0.25% SDS and 1% Triton X-100. Lysis under nondenaturing conditions was performed by incubating the monolayers for 30 min at 4°C with 1.6 ml of immunoprecipitation buffer supplemented with 1% Triton X-100. Lysates were then clarified by centrifugation for 10 min at top speed in a refrigerated microcentrifuge. Immunoprecipitation was performed with the R39/V anti-NS4A rabbit serum as described previously (52).

Preparation of CHAPS extracts and assay of activity of the NS3 protease on in vitro-translated HCV substrate.

BHK cells were infected with chimeric viruses at an MOI of 1. After 14 h at 37°C, the cells were washed twice with PBS and extracted directly in the culture dish for 30 min on ice with 25 mM HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.5)–80 mM K-acetate–1 mM Mg-acetate–10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT)–1% 3-[(3 cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonic acid (CHAPS)–20% (wt/vol) glycerol (CHAPS extracts). Extracts were clarified by centrifugation for 20 min in a refrigerated microcentrifuge, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until used. Extracts were diluted by using as the diluent CHAPS extracts derived from BHK cells infected with wild-type (wt) SBV (control extracts). The purified recombinant NS3 protease domain (NS31-180) (49) was a kind gift of C. Steinkühler. This protease was diluted by using control extracts and used at the concentrations indicated in the figure legends. For immunoblot analysis, 30 μl of each undiluted or diluted extract was fractionated on an SDS–10% polyacrylamide gel and probed with the anti-NS3 monoclonal antibody 46.D8. mRNA encoding the NS5A-NS5BΔC51 substrate was transcribed and translated in vitro as described previously (48). Aliquots (5 μl) of the translation reaction mixture were mixed with an equal volume of adequately diluted cell extract and incubated at 30°C for 60 min. Where indicated, a 2 μM final concentration of a synthetic peptide comprising three lysine residues and amino acids 21 to 32 of NS4A (Pep4AK) (5) was included in the reaction mixture. Reactions were stopped by the addition of 100 μl of sample buffer (0.3 M Tris [pH 8.8], 2.5% SDS, 100 mM DTT, 1 M sucrose, 0.01% bromophenol blue). Cleavage of the labelled precursor was assessed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on 10% gels and autoradiography.

Structural analyses.

Structural analyses were performed by using Insight (11) and Whatif (54).

Bacterial expression and protein purification.

The MutA protein was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) by a protocol modified from that of Pryor and Leiting (41). A 1.5-liter liquid culture derived from a single transformed bacterial colony was grown at 37°C to an A600 of 0.8 in M9 modified minimal medium (5 g of glucose per liter, 1 g of ammonium sulfate per liter, 100 mM potassium phosphate [pH 7], 5 μM biotin, 7 μM thiamine, 0.5% Casamino Acids, 0.5 mM MgSO4, 0.5 mM CaCl2, 13 μM FeSO4, 50 mg of ampicillin per liter). It was then cooled to 18°C, brought to 100 μM ZnCl2, and induced with 600 μM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) for 6 h at 18°C. All subsequent operations were performed at 4°C unless otherwise indicated. Cells were harvested and then disrupted with a Microfluidizer (model 110-S) in 80 ml of buffer A (25 mM sodium phosphate [pH 6.5], 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1% CHAPS, and 6 mM DTT, containing 0.2 M NaCl and COMPLETE [Boehringer] protease inhibitor mixture). The insoluble material was pelleted at 27,000 × g for 30 min in a Sorvall SS34 rotor. The clarified supernatant was filtered through 10 ml of DEAE-Sepharose Fast Flow resin (Pharmacia) preequilibrated in lysis buffer. The MutA protein was subsequently purified by chromatography as follows. The sample was loaded on a 10-ml High Trap heparin-Sepharose column (Pharmacia) equilibrated with buffer A containing 200 mM NaCl and eluted with a 200-ml linear gradient from 0.2 to 1 M NaCl in the same buffer. The fractions containing the protein of interest were pooled, the NaCl concentration was adjusted to 100 mM by dilution with buffer A, and the mixture was loaded on a 6-ml Resource S column. After a wash with 5 column volumes of the loading buffer, the NS3 protein was eluted in a >80% pure form with a 60-ml linear gradient from 0.1 to 1 M NaCl in buffer A. Protein stocks were quantified by amino acid analysis and stored at a concentration of 5 to 20 μM in buffer A containing 50% glycerol and 0.5 M NaCl at −80°C after shock-freezing in liquid nitrogen.

Peptides and HPLC protease assays.

The peptide substrate derived from the NS5A-NS5B cleavage sequence (H-EAGDDIVPCSMSYTWTGA-OH) was purchased from Anaspec. The concentration of stock peptide aliquots, prepared in buffered aqueous solutions and kept at −80°C until use, was determined by quantitative amino acid analysis performed on HCl-hydrolyzed samples. If not specified differently, cleavage assays were performed in 60 μl of 25 mM HEPES-NaOH (pH 7.5)–0.05% Triton X-100–15% glycerol–10 mM DTT. Pep4AK (5) was used as a protease cofactor. This peptide was preincubated for 10 min at 23°C with NS31-180 or MutA (2 nM), and the reactions were started by adding the substrate at a final concentration of 5 μM. Incubation times at 23°C were chosen in order to obtain <10% conversion. Reactions were stopped by addition of 40 μl of 1% trifluoracetic acid. Cleavage of peptide substrates was determined by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) with a Merck-Hitachi chromatograph equipped with an autosampler, as described previously (49). Cleavage products were quantified by integration of chromatograms with respect to appropriate standards. Initial rates of cleavage were determined with samples having <10% substrate conversion. Kinetic parameters were calculated from a nonlinear least-squares fit of initial rates as a function of substrate concentration with the aid of Kaleidagraph software, assuming Michaelis-Menten kinetics.

RESULTS

Comparison of chimeric viruses expressing different forms of the NS3-NS4A protease.

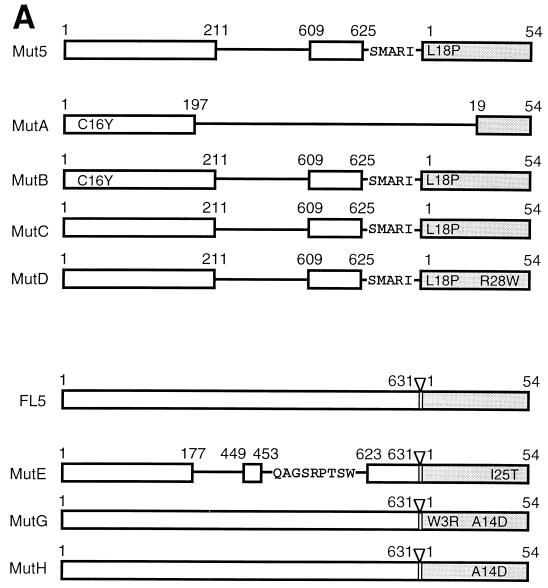

Mut5 is a chimeric virus derived from SBV whose propagation depends on the activity of the NS3-NS4A protease of HCV (15). The genome of this chimera (pSIN-Mut5wt) was constructed by fusing HCV sequences coding for a ΔNS3-NS4A fusion protein, encompassing the protease domain of NS3 and the entire NS4A, with the gene coding for the SBV structural polyprotein (Fig. 1A) (15). In addition, the catalytic serine of the SBV C capsid/autoprotease protein was mutated into alanine and two NS3 specific cleavage sites were engineered at the NS4A/C and C/PE2 junctions, in such a way that release of the SBV C protein from the chimeric polyprotein, correct maturation of the SBV PE2 and E1 glycoproteins, and, consequently, generation of viable viral particles required two NS3-dependent cleavages (Fig. 1A) (15). In fact, this chimeric genome produced infectious virus only in the presence of an active protease. The Mut5 virus displayed a temperature-dependent phenotype in the formation of lysis plaques and stably expressed the ΔNS3-NS4A protease.

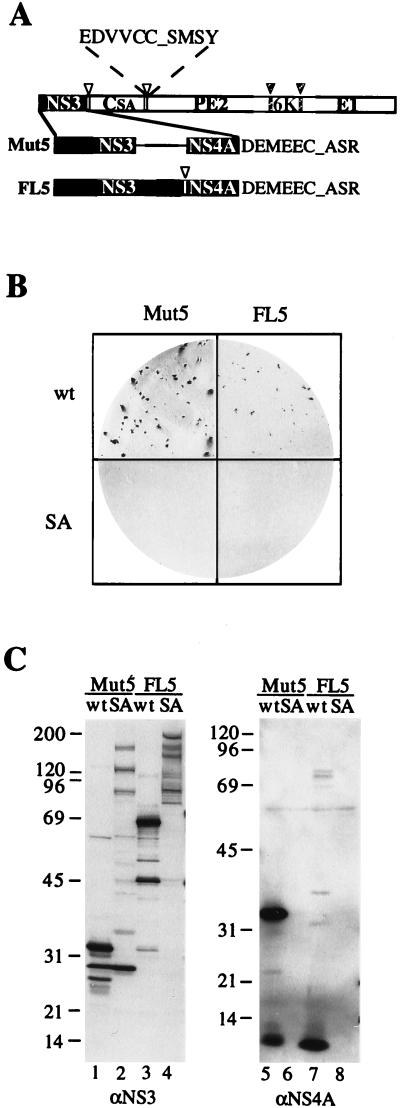

FIG. 1.

Comparison of chimeric viruses expressing different forms of the NS3-NS4A protease. (A) Schematic diagram of structural polyproteins encoded by chimeric cDNAs. Empty and hatched arrowheads and bars indicate the cleavage sites of NS3 and signal peptidase, respectively. CSA, SBV C protein inactivated by alanine substitution of the catalytic serine; PE2, 6K, and E1, SBV membrane proteins. The sizes of the black boxes reflect the sizes of the NS3 proteases present in the pSIN-Mut5 and pSIN-FL5 constructs. DEMEEC_ASR and EDVVCC_SMSY denote the amino acid sequences of the NS4A/C and C/PE2 junctions, respectively, with the underscores representing the scissile bonds. (B) Plaque phenotypes of chimeric viruses. Shown are plaques produced in BHK cells by transfection of the indicated chimeric RNAs. Plaques were revealed by immunostaining with the rabbit anti-SBV serum after 3 days of incubation at 30°C. (C) Processing of chimeric polyprotein. Cell lysates were produced at 18 h posttransfection, fractionated on an SDS–10% polyacrylamide gel, transferred to nitrocellulose, and analyzed by immunoblotting with the anti-NS3 (αNS3) and anti-NS4A (αNS4A) monoclonal antibodies. Positions of molecular mass standards (in kilodaltons) are indicated at the left.

The NS3 protein encompasses a protease domain and a helicase domain, and it is possible that the presence of the helicase may affect the protease activity. To test this hypothesis, we constructed another chimeric cDNA (pSIN-FL5wt [Fig. 1A]), encoding the full-length NS3 protein followed by NS4A and thus differing from pSIN-Mut5wt not only in the size of the NS3 sequence but also in that it encoded three NS3-specific cleavage sites (NS3/NS4A, NS4A/C, and C/PE2) instead of two. The infectivity of pSIN-FL5wt was tested in comparison with that of pSIN-Mut5wt in a plaque formation assay following transfection of the in vitro-transcribed RNAs in BHK cells. Although transfection of both constructs yielded lysis plaques at 30 but not at 37°C, pSIN-FL5wt RNA reproducibly induced formation of lysis plaques slightly smaller than those formed by pSIN-Mut5wt (Fig. 1B). As expected and as observed in the case of pSIN-Mut5, inactivation of NS3 by alanine substitution of the catalytic serine abolished the infectivity of pSIN-FL5 (Fig. 1B, compare wt and SA), confirming that this chimera also required the activity of the NS3-NS4A protease for its propagation. This conclusion was further supported by analysis of the processing of the chimeric polyproteins (Fig. 1C). Transfection of pSIN-FL5wt yielded the predicted 69-kDa NS3 protein and 6-kDa NS4A protein (Fig. 1C, lanes 3 and 7) as well as SBV C, PE2, and E1 proteins of the correct size (data not shown). In addition, the anti-NS3 antibody recognized a 47-kDa band, representing an amino-terminal fragment of NS3 generated by an NS4A-dependent autocleavage in the helicase domain (NS3ΔH; Fig. 1C, lane 3) (17, 52). The anti-NS4A antibody also recognized a number of minor bands, including a 75-kDa NS3-NS4A precursor and a 38-kDa NS4A-C precursor (Fig. 1C, lane 7, and data not shown). As already described (15), transfection of pSIN-Mut5wt resulted in the production of a 33-kDa ΔNS3-NS4A fusion protein (Fig. 1C, lanes 1 and 5) and of SBV structural proteins of the correct size (data not shown). Conversely, transfection with pSIN-Mut5SA and pSIN-FL5SA yielded several higher-molecular-mass bands, corresponding to unprocessed or partially processed precursors recognized by the anti-NS3 antibody (Fig. 1C, lanes 2 and 4). Notably, a 29-kDa band, representing an NS3-containing fragment of the viral polyprotein of unknown origin, was visible in cells transfected with pSIN-Mut5wt and pSIN-Mut5SA.

These results indicated that inactivation of the protease abolished processing and infectivity and that expression of different forms of NS3-NS4A had a detectable effect on the propagation of chimeric viruses.

In vitro evolution of NS3-dependent chimeric viruses.

We previously observed that when subcultured at 30 and 37°C, pSIN-Mut5wt virus stably expressed the 33-kDa ΔNS3-NS4A protease up to the sixth passage (15) and that the titer of the progeny virus increased, suggesting the emergence of virus mutants with an improved propagation ability. Intrigued by this observation and to understand if there was any correlation between the activity of the NS3-NS4A protease and the improved virus propagation, we repeated the subculture experiment with both pSIN-Mut5wt and pSIN-FL5wt viruses. We thus propagated the viruses obtained by transfection of both pSIN-Mut5wt and pSIN-FL5wt RNAs (Mut5 and FL5) for 9 and 11 consecutive passages, respectively, at either 30 or 37°C. We observed a progressive increase in titer, which rose from 104 to 107 PFU ml−1 in the case of Mut5 and from <103 to 107 PFU ml−1 in the case of FL5 (Table 1), accompanied by the emergence of virus variants which formed lysis plaques larger than those produced by their ancestors (Fig. 2). This increase in titer and plaque size was gradual, suggesting that viruses progressively accumulated mutations which led to improved spreading ability. Also, more-infectious variants of both chimeras emerged at earlier passages when subcultured at 30°C rather than 37°C. Mut5 and FL5 progeny viruses remained temperature sensitive, but those derived from subculture at 37°C formed very small lysis plaques at 37°C (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Titers of viruses derived from passaging of Mut5 and FL5 virusesa

| Passage | Titer (PFU ml−1)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mut5

|

FL5

|

|||

| 30°C | 37°C | 30°C | 37°C | |

| III | 5.6 × 104 | 4 × 104 | 1.5 × 105 | <103 |

| V | 6.8 × 105 | 1 × 105 | 4 × 106 | 8 × 104 |

| VII | 1.7 × 106 | 5 × 105 | 9.6 × 106 | 1.5 × 105 |

| IX | 1 × 107 | 1.4 × 106 | 2.2 × 107 | 7.5 × 105 |

| XI | 1.6 × 107 | 1 × 106 | ||

Mut5 and FL5 viruses were subcultured at 30 and 37°C as described in Materials and Methods. Media of the indicated passages were collected when a cytopathic effect was clearly evident and titrated on BHK cells at 30°C.

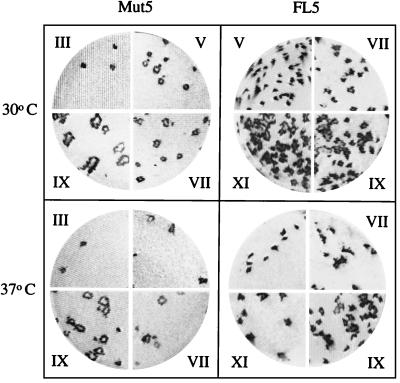

FIG. 2.

Plaque phenotypes of serial passages of chimeric viruses. Shown are plaques produced in BHK cells after infection with serial passages of the FL5 and Mut5 viruses obtained by subculture at 30 or 37°C. Roman numerals indicate the passage used as the inoculum. Plaques were revealed by immunostaining with the rabbit anti-SBV serum after 3 days of incubation at 30°C.

Next, we analyzed the NS3 and NS4A proteins produced by cells infected with the various passages derived from the subculture experiment. Immunoblots with anti-NS3 and anti-NS4A antibodies indicated that progeny viruses produced NS3-NS4A proteins different in size from those encoded by the original viruses (compare Fig. 3 to Fig. 1C). In particular, subculture of Mut5 at 30°C led to the progressive replacement of the 33-kDa ΔNS3-NS4A fusion protein with a 28-kDa band, which reacted with both anti-NS3 and anti-NS4A antibodies and thus represented a smaller ΔNS3-NS4A fusion protein (Fig. 3, lanes 1 to 4). At 37°C, a less pronounced disappearance of the 33-kDa ΔNS3-NS4A fusion protein became evident at passage IX and was associated with the appearance of a 32-kDa smeared band which reacted with both the anti-NS3 and anti-NS4A antibodies, thus also representing a ΔNS3-NS4A fusion protein (Fig. 3, lanes 5 to 8). Propagation of FL5 resulted in a complex change of the NS3-NS4A protein pattern (Fig. 3, lanes 9 to 16). Subculture at 30°C resulted in the disappearance of the 69-kDa full-length NS3 protein and the emergence of a 24-kDa major band, which presumably encompassed the entire NS3 protease domain (Fig. 3A, lanes 9 to 12). Two additional bands of 31 and 34 kDa, which reacted with both anti-NS3 and anti-NS4A antibodies and presumably represented ΔNS3-NS4A uncleaved precursors, also became visible, while no detectable changes in the migration of the 6-kDa band corresponding to NS4A were observed (Fig. 3, lanes 9 to 12). Subculture at 37°C caused no significant changes in the pattern of bands reactive with the anti-NS3 antibody, except that the 47-kDa NS3ΔH band was replaced by a 52-kDa band (Fig. 3A, lanes 13 to 16). This 52-kDa band was also detected when the NS3 protein was expressed in the absence of NS4A by using noninfectious SBV vectors (data not shown). The 6-kDa band corresponding to NS4A became barely detectable, and no other major band reacting with the anti-NS4A antibody became visible. The anti-NS4A antibody barely recognized the 38-kDa NS4A/C protein and a series of 60- to 75-kDa NS3-NS4A precursors which were also present in cells transfected with the pSIN-FL5wt RNA (Fig. 3B, lanes 13 to 16, and 1C, lane 7). Immunoblot analysis with anti-SBV antibodies showed no significant changes in the electrophoretic mobilities of the SBV structural proteins (data not shown). No accumulation of uncleaved precursors containing the NS4A/C and C/PE2 junctions was observed, implying that cleavage at these sites occurred efficiently (data not shown; see below).

FIG. 3.

Evolution of the NS3-NS4A protease upon passaging. BHK cells were infected at an MOI of less than or equal to 0.1 with the indicated passages (roman numerals above the lanes) of Mut5 and FL5 viruses obtained by subculture at the indicated temperature. Cell lysates were produced after 72 h at the corresponding temperature, fractionated by SDS–10% PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and analyzed by immunoblotting with the anti-NS3 (A) and anti-NS4A (B) monoclonal antibodies. Positions of molecular mass standards (in kilodaltons) are indicated at the left of each panel.

Taken together, these results confirmed that subculture of chimeric viruses caused the outburst of more infectious mutants and indicated that the improved spreading ability of these mutants was associated with changes in the electrophoretic pattern of the NS3-NS4A protease.

Activities of the NS3-NS4A proteases encoded by evolved chimeric viruses.

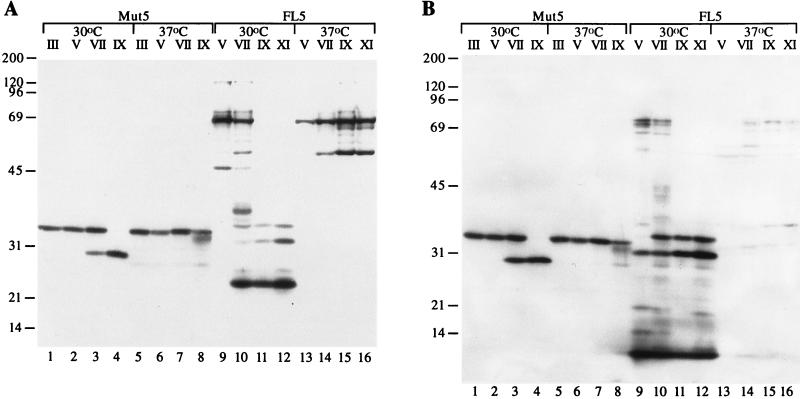

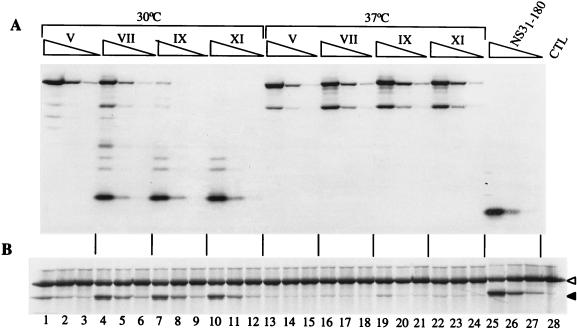

We prepared extracts of cells infected with the various passages of chimeric viruses and assayed the activity of the NS3-NS4A proteases present in these extracts on a 35S-labelled in vitro-translated HCV substrate comprising the NS5A/NS5B cleavage site (48). For comparison, we also assayed a purified recombinant protease, encompassing amino acids 1 to 180 of NS3 (NS31-180 [49]) supplemented with a synthetic peptide spanning amino acids 21 to 32 of NS4A (Pep4AK [5]). The activity of each protease was determined by estimating the amount of NS3-NS4A protease in serial fivefold dilutions of each extract by immunoblotting with an anti-NS3 monoclonal antibody. Within the limits of this type of quantitation, extracts from cells infected with various passages of Mut5 virus contained comparable amounts of NS3 protease (Fig. 4A). The activity assay indicated that the protease produced by cells infected with passages III and V of Mut5 virus subcultured at 30°C catalyzed very little conversion of the substrate (Fig. 4B, lanes 1 to 6), while that produced by cells infected with passages VII and IX showed a higher activity, comparable to that of NS31-180 supplemented with Pep4AK peptide (Fig. 4, lanes 7 to 12, 25, and 26). This apparent increase in activity matched the replacement of the 33-kDa ΔNS3-NS4A band with the 28-kDa ΔNS3-NS4A band, thus suggesting that the latter form of the protease was possibly more active (Fig. 4, lanes 1 to 12). The protease produced by cells infected with Mut5 viruses subcultured at 37°C displayed little activity, and no increase in the activity was observed for later passages (Fig. 4B, lanes 13 to 24).

FIG. 4.

Activity of the NS3 protease variants produced by BHK cells infected with Mut5 progeny. BHK cells were infected at an MOI of 1 with the indicated passages (roman numerals above the lanes) of Mut5 virus obtained by subculture at the indicated temperature. CHAPS extracts were produced after 14 h of incubation at 37°C. The amount of NS3-NS4A protease present in each extract was estimated by immunoblotting with an anti-NS3 monoclonal antibody (A), and the protease activity was determined with the in vitro-translated, 35S-labelled NS5A-NS5BΔC51 substrate (B) as described in Materials and Methods. Three dilutions of each extract were analyzed (undiluted and 1:5 and 1:25 dilutions, symbolized by the triangles above the lanes). The purified recombinant NS3 produced in bacteria (NS31-180) was supplemented with Pep4AK (2 μM final concentration) and used at 10 and 2 nM final concentrations. CTL, control extract. Empty and black triangles indicate the NS5A-NS5BΔC51 precursor and the mature NS5A protein, respectively. Only the relevant parts of the gels are shown.

The activities of the proteases encoded by viruses derived from subculture of FL5 showed a trend similar to that observed with Mut5 progeny. All extracts contained commensurate amounts of NS3 protein, despite the difference in the size of the NS3 band (Fig. 5A). Also in this case, subculture at 30°C was accompanied by a small increase in the NS3-NS4A protease activity which paralleled the disappearance of the 69-kDa NS3 band and the appearance of the 24-kDa ΔNS3 band, suggesting that this form of NS3 was probably responsible for the increase in activity (Fig. 5, lanes 1 to 12). Conversely, propagation of FL5 at 37°C resulted in an appreciable decrease in the activity of the NS3-NS4A protease, although all extracts displayed measurable activity (Fig. 5, lanes 13 to 24).

FIG. 5.

Activity of the NS3 protease variants produced by BHK cells infected with FL5 progeny. BHK cells were infected at an MOI of 1 with the indicated passages (roman numerals above the lanes) of FL5 virus obtained by subculture at the indicated temperature. CHAPS extracts were produced and analyzed as described in the legend to Fig. 4. The purified recombinant NS3 produced in bacteria (NS31-180) was supplemented with Pep4AK (2 μM final concentration) and used at 10, 2, and 0.4 nM final concentrations.

These data indicated that all variants of the NS3-NS4A proteases expressed by viruses selected during subculture were active, thus confirming that mutant viruses that emerged during subculture were still dependent on the NS3-NS4A protease activity for their propagation. Moreover, they suggested that changes in the electrophoretic profile of the NS3-NS4A proteases correlated with changes in the in vitro activities of the variant enzymes. The reduction in the sizes of the ΔNS3-NS4 (Mut5) and NS3 (FL5) proteins observed during subculture at 30°C was associated with an increased in vitro activity, thus prompting the speculation that these smaller forms of the NS3-NS4A protease either possessed a higher intrinsic activity or were more stable under the experimental conditions employed. Conversely, the reduction of the in vitro activity observed for the enzymes expressed by FL5 viruses passaged at 37°C correlated with the inability to perform the self-cleavage which generated the 47-kDa NS3ΔH fragment.

Characterization of NS3-NS4A proteases encoded by selected mutant viruses.

To characterize individual NS3-NS4A protease variants produced by distinct viruses, we plaque purified mutants derived from subculture of Mut5 and FL5 at both 30 and 37°C. Mutants were grouped on the basis of the electrophoretic profile of the NS3 and NS4A proteins, and one member of each group was selected for further examination (data not shown; see below). MutA, MutB, MutC, and MutD were derived from passage IX of Mut5 at 30°C (MutA and MutB) and 37°C (MutC and MutD); MutE, MutG, and MutH were derived from passage XI of FL5 at 30°C (MutE) and 37°C (MutG and MutH).

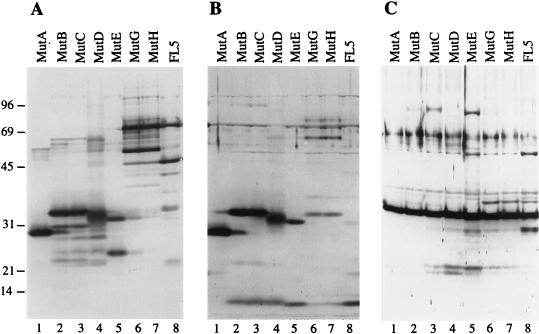

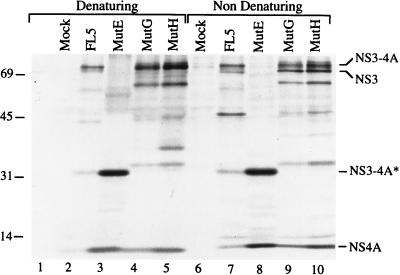

The immunoblot shown in Fig. 6 indicated that the profile of the NS3 and NS4A proteins produced by these selected mutants was similar to that of the proteases derived from cells infected with the corresponding passage (compare Fig. 3 and 6). Cells infected with viruses derived from Mut5 produced either a 28-kDa (MutA), a 33-kDa (MutB and MutC), or a 32-kDa (MutD) protein reactive with both anti-NS3 and anti-NS4A antibodies and thus representing ΔNS3-NS4A fusion proteins (Fig. 6A and B, lanes 1 to 4). MutE-infected cells produced two proteins of 24 and 31 kDa that were reactive with the anti-NS3 antibody (Fig. 6A, lane 5). The 31-kDa protein also reacted with the anti-NS4A antibody, which also recognized the 6-kDa NS4A band (Fig. 6B, lane 5), indicating that the 31-kDa band represented a ΔNS3-NS4A precursor which, upon self-cleavage, originated the 24-kDa ΔNS3 band and the 6-kDa NS4A band. Cells infected with MutG and MutH produced two major proteins reactive with the anti-NS3 antibody: a 69-kDa band corresponding to the full-length NS3 protein and a 52-kDa band (Fig. 6A, lanes 6 and 7). Neither of these bands was recognized by the anti-NS4A antibody, which hardly recognized the 6-kDa NS4A and a series of minor bands akin to those observed in lanes 13 to 16 of Fig. 3B (Fig. 6B, lanes 6 and 7). Similar results were obtained by probing the blots with different anti-NS4A antibodies (data not shown). The poor detection of the NS4A proteins in the immunoblot is most likely due to reduced metabolic stability of these mutant proteins, since by immunoprecipitation we verified that MutG- and MutH-infected cells did express an NS4A protein comigrating with that observed in cells infected with MutE and FL5 viruses (Fig. 7, lanes 1 to 5). Under nondenaturing conditions, the anti-NS4A antibody also coimmunoprecipitated the NS3 proteins produced by cells infected with FL5, MutG, and MutH but not MutE (Fig. 7, lanes 6 to 10). This result indicated that, similarly to the proteins produced by the original FL5 virus, the NS3 and NS4A proteins encoded by MutG and MutH assembled into a detergent-stable complex, while those encoded by MutE did not.

FIG. 6.

Immunoblot analysis of viral proteins produced by cells infected with plaque-purified viruses. BHK cells were infected at an MOI of less than 0.1 (FL5) or 1 (all other mutants) with passage II of the viruses indicated above the lanes. Cell lysates were produced after 72 h at 30°C (FL5) or 16 h at 37°C (all other mutants), fractionated by SDS–10% PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and analyzed by immunoblotting with the anti-NS3 monoclonal antibody (A) and the anti-NS4A (B) and anti-SBV C (C) rabbit sera. Positions of molecular mass standards (in kilodaltons) are indicated at the left of each panel.

FIG. 7.

Complex formation between the NS3 and NS4A proteins encoded by plaque-purified viruses. BHK cells were infected at an MOI of less than 0.1 (FL5) or 1 (all other mutants) with passage II of the viruses indicated above the lanes. Cells were labelled with 35S-amino acids and lysed under denaturing and nondenaturing conditions as described in Materials and Methods. Immunoprecipitation was performed with the anti-NS4A rabbit serum. Immunoprecipitated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE. Shown is the autoradiogram of the relevant region of the gel. HCV-specific proteins are indicated on the right. Positions of molecular mass standards (in kilodaltons) are indicated on the left.

To investigate whether the proteases encoded by mutant viruses cleaved the chimeric structural polyprotein in vivo, we analyzed the profile of the SBV C protein produced in infected cells by immunoblotting. Transfection experiments with the wt and SA versions of pSIN-Mut5 and pSIN-FL5 RNAs demonstrated that SBV C was released from the chimeric polyprotein precursors only in the presence of an active NS3-NS4A protease (reference 15 and data not shown). Cells infected with all selected mutant viruses produced a 33-kDa SBV C protein identical to that of the original FL5 virus (Fig. 6C, compare lanes 1 to 7 with lane 8). The anti-SBV C antibody also recognized a few minor bands probably representing uncleaved precursors (including a 38-kDa NS4A-C precursor), which were also present in cells infected with FL5 and Mut5 (Fig. 6C, lane 8, and data not shown). This suggested that proteases encoded by mutant viruses cleaved the cognate polyproteins with an efficiency comparable to that of the enzymes encoded by the original chimeric viruses.

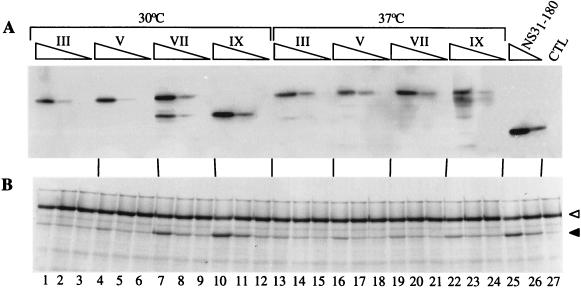

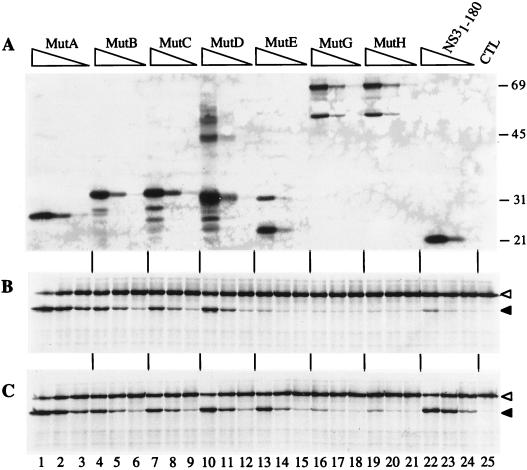

Next, we assessed the in vitro activities of the variant proteases. We prepared CHAPS extracts of cells infected with various mutants, estimated the amount of NS3 present in each extract by immunoblotting (Fig. 8A), and assayed the activity of each extract in the absence or presence of Pep4AK (Fig. 8B and C). The NS3-NS4A proteases produced by cells infected with Mut5 derivatives (MutA, MutB, MutC, and MutD) had a maximal activity in the same range as that of the purified recombinant NS31-180 protease, but unlike the latter, they were either poorly or not stimulated by the addition of Pep4AK (Fig. 8B and C, lanes 1 to 12 and 22 to 24). This result is in line with the hypothesis that these ΔNS3-NS4A fusion proteases are activated intramolecularly by NS4A. Consistent with the data shown in Fig. 4, the 28-kDa ΔNS3-NS4A protease produced by MutA was more active than all of the other forms of virally encoded protease and possibly slightly more active than the recombinant NS3 (Fig. 8B and C, compare lanes 1 to 3 with lanes 4 to 12 and 22 to 24). The MutE, MutG, and MutH extracts displayed little activity in the absence of Pep4AK (Fig. 8B and C, lanes 13 to 21). However, while MutE protease was stimulated about 10-fold by Pep4AK and reached an activity comparable to that of the NS31-180 protease, the MutG and MutH enzymes were activated only partially by the synthetic cofactor and were clearly less active than the NS31-180 protease (Fig. 8B and C, compare lanes 13 to 21 with lanes 22 to 24).

FIG. 8.

Activities of protease variants expressed by plaque-purified viruses. BHK cells were infected at an MOI of 1 with passage II of the viruses indicated above the lanes. CHAPS extracts were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. The amount of NS3-NS4A protease present in each extract was estimated by immunoblotting (A), and the protease activity was determined with the in vitro-translated, 35S-labelled NS5A-NS5BΔC51 substrate (B and C) as described in the legend to Fig. 4, except that activity was determined in the absence (B) or presence (C) of a 2 μM final concentration of Pep4AK. The purified recombinant NS3 produced in bacteria (NS31-180) was used at 10, 2, and 0.4 nM final concentrations. Positions of molecular mass standards (in kilodaltons) are indicated on the right.

These data confirmed that all selected proteases were active in vitro on an HCV substrate, and they suggested that the stability of the NS3-NS4A interaction could be responsible for the different in vitro activities of the various enzymes.

Characterization of mutated protease genes.

To identify the mutations present in the proteases encoded by the selected mutant viruses, we have cloned and sequenced the corresponding cDNAs. With one exception, all nucleotide changes resulted in amino acid substitutions, indicating that silent mutations were usually not selected. The deduced amino acid sequences are illustrated in Fig. 9A. All protease variants except that encoded by MutC differed from the original proteases by at least one amino acid. The most remarkable type of mutations were deletions of HCV sequences corresponding to the helicase domain of NS3 found in the MutA and MutE proteases. MutA encoded a ΔNS3-ΔNS4A fusion protein encompassing amino acids 1 to 197 of NS3 and amino acids 19 to 54 of NS4A. MutE encoded the protease domain (amino acids 1 to 177) of NS3 connected to the NS4A protein via a 23-amino-acid linker sequence derived from the helicase domain. In the latter protease the sequence of the NS3/NS4A cleavage site was conserved, and the linker sequence was derived from three different regions of the helicase gene and included a 9-amino-acid stretch (QAGSRPTSW) encoded by an alternative reading frame, indicating that this mutant originated from multiple recombination events. MutA and MutE each contained a point mutation, the replacement of cysteine 16 of NS3 by tyrosine (C16Y) and that of isoleucine 25 of NS4A by threonine (I25T), respectively. Cysteine 16 is not always conserved in the different HCV strains available, but it is never a tyrosine. The C16Y mutation was the only one found in the MutB protease, suggesting that this mutation emerged early during subculture of Mut5 and was then followed by the deletion observed for MutA. Isoleucine 25 is located in the NS4A domain necessary for protease activation, is conserved in all HCV serotypes, and affects the stability of the NS3-NS4A complex (4, 34, 46).

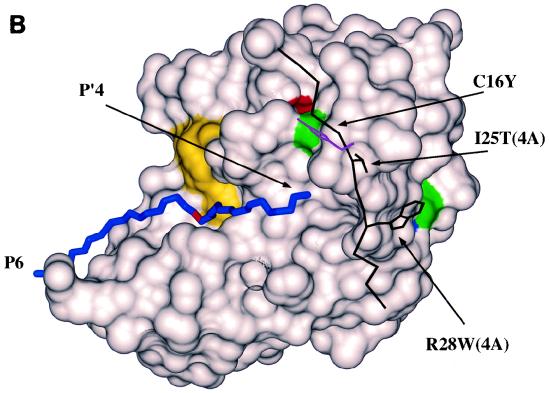

FIG. 9.

Mutations of selected protease variants. (A) Schematic representation of mutations found in NS3-NS4A protease variants. The amino acid sequence of each protease variant was deduced from the nucleotide sequence of corresponding cDNA, obtained as described in Materials and Methods, and compared to that of the HCV BK protease. The NS3 and NS4A domains are symbolized by white and grey boxes, respectively. Numbers above each box indicate the first and last amino acids of each domain. Point mutations (natural amino acid, its position, and mutated amino acid) are indicated inside the boxes. Black lines indicate deleted regions, and amino acids encoded by frameshift mutations are indicated outside the boxes. Triangles indicate the NS3/NS4A cleavage site. Numbering refers to the first natural amino acids of NS3 and NS4A. (B) Model of the solvent-accessible surface of the NS3-NS4A mutant protease. The model contains all three mutations falling in the region of known structure. The substrate is modelled, and its C-alpha trace (in blue) is shown for orientation. The scissile bond is in red. The surface of the catalytic triad residues is in yellow, and the solvent-exposed surface of the replaced tyrosine 16 of NS3 and tryptophan 28 of NS4A is shown in green (carbon atoms), red (oxygen atoms), and blue (nitrogen atoms). Threonine 25 of NS4A is completely buried. For clarity, the C-alpha trace of residues 20 to 32 of NS4A and the side chains of threonine 25 and tryptophan 28 of NS4A (in black) and tyrosine 16 of NS3 (in magenta) are shown on top of the surface model.

Only point mutations in NS4A were observed in the MutD, MutG, and MutH proteases. The MutD protease showed only replacement of arginine 28 by tryptophan (R28W). Replacement of arginine 28 by asparagine, glutamine, or aspartate significantly impaired a 14-mer NS4A peptide from activating NS3 in vitro (46), while mutation to alanine did not impair the full-length NS4A from activating NS3 in vivo (34). The MutG and MutH proteases both had an alanine 14-to-aspartate (A14D) substitution, and the MutG protease also contained a tryptophan 3-to-arginine (W3R) mutation, thus suggesting that MutG was derived from MutH. Both mutations introduce a charged residue in the hydrophobic amino-terminal domain of NS4A, which is necessary for the assembly of a stable NS3-NS4A complex but not for protease activation (4, 30, 34, 51).

We also determined the sequences of the NS4A/C and C/PE2 junctions. No mutations were found at the NS4A/C junction, while two of the selected viruses (MutG and MutH) had the P2 residue of the C/PE2 cleavage site changed from cysteine to tyrosine. Notably, although the P2 residue of all natural NS3 cleavage sites is not conserved, tyrosine is never observed in this position.

We modelled the C16Y, I25T, and R28W mutations in the three-dimensional structure of the protease (Fig. 9B). The available X-ray structures of the NS3-NS4A complex include the regions from isoleucine 3 to methionine 179 of NS3 and from glycine 21 to serine 32 of NS4A (29, 56). NS4A is deeply buried within the core of the protease and forms an internal beta strand of an antiparallel beta sheet pairing with the strands from valine 35 to serine 37 and tyrosine 6 to threonine 10 of the protease domain. In the wt structure, the backbone of cysteine 16 is completely buried, while its S gamma is partially exposed. The replacement of this residue with a tyrosine is compatible with the local structural environment and can be modelled without any unfavorable interaction, with the hydrophobic part of the tyrosine side chain buried between the enzyme and its cofactor in a favorable hydrophobic environment and the OH pointing toward the solvent. Since exposed cysteines are very rare in protein structures, the C16Y mutation could be interpreted as a counterselection for the presence of an exposed cysteine. Arginine 28 of NS4A is buried and makes hydrogen bonds with glutamine 8 and glutamine 28 of NS3. When this residue is replaced by a tryptophan, the hydrogen bond with glutamine 8 is retained, and the lack of a second hydrogen bond is likely to be compensated for by a more favorable hydrophobic interaction of the bulky tryptophan side chain with its environment. The I25T mutation is difficult to interpret, since the isoleucine side chain is buried, and a substitution with a polar side chain is unexpected. It should be mentioned, however, that buried threonine side chains are not unusual in proteins.

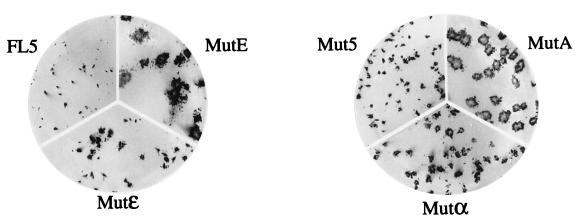

The observation that MutC showed no changes in the NS3-NS4A gene clearly indicated that the improved plaque phenotype of this mutant was due to a mutation(s) occurring in another part(s) of the viral genome. Nonetheless, it was conceivable that mutations found in other protease variants were responsible for the improved plaque phenotype of the cognate viruses. To verify this hypothesis, we replaced the NS3-NS4A protease-coding sequences of pSIN-FL5wt with those found in MutA and MutE and tested the infectivities of viruses derived from transfection of these clones (Mutα and Mutɛ, respectively) in comparison with the corresponding parent viruses. As shown in Fig. 10, the Mutα and Mutɛ viruses produced lysis plaques slightly larger than those formed by infection with Mut5 and FL5 but clearly smaller than those formed by MutA and MutE. This result indicated that although mutations in the protease gene played a role in determining the spreading ability of the chimeric viruses, they were not sufficient by themselves to cause the improvement of the plaque phenotype displayed by selected viruses, thus implying that other mutations had a synergistic or additive effect in determining the phenotype of the selected viruses. This conclusion is in line with the observation that passaging of chimeric viruses resulted in a stepwise improvement in plaque phenotype, indicating that several mutations had accumulated during subculture.

FIG. 10.

Correlation between NS3-NS4A protease variants and plaque phenotypes of chimeric viruses. Shown are plaques produced in BHK cells after infection with plaque-purified MutA and MutE viruses and with passage I of FL5, Mut5, Mutα, and Mutɛ viruses. Plaques were revealed by immunostaining with the rabbit anti-SBV serum after 3 days of incubation at 30°C.

Biochemical characterization of the MutA-encoded NS3-NS4A protease.

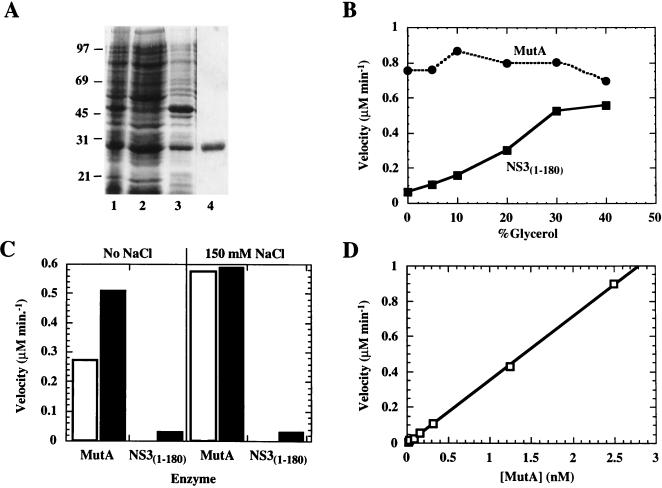

To further investigate the characteristics of the selected protease variants, we decided to express and purify the MutA protease. For this purpose we cloned the corresponding cDNA in the pT7-7 bacterial expression vector. The expression cassette included the exact sequence indicated in Fig. 9A, but the C-terminal cysteine was replaced by glycine and a three-residue lysine tail was added to improve solubility, thus resulting in the C-terminal sequence DEMEEGKKK. Expression of the recombinant protein in E. coli cells was induced with IPTG at 18°C, and more than 70% of the protein was recovered in the soluble fraction upon mechanical disruption of bacterial cells (Fig. 11A, lanes 1 to 3). The protein was purified by affinity and ion-exchange chromatographies on heparin-Sepharose and Resource S columns, respectively. The purification procedure yielded about 1 mg of more than 80% pure protein per liter of bacteria, as judged by SDS PAGE (Fig. 11A, lane 4).

FIG. 11.

Biochemical characterization of the MutA protease. (A) SDS-PAGE analysis of different purification stages of the MutA protease expressed in E. coli. Lanes: 1, whole-cell lysate; 2, soluble fraction; 3, particulate fraction; 4, purified protein. Positions of molecular mass standards (in kilodaltons) are indicated on the left. (B) Effect of glycerol concentration on the protease activity of purified MutA protein. Two nanomolar MutA or NS31-180 protease was incubated with 5 μM NS5A-NS5B synthetic peptide substrate for 10 min in the presence of increasing concentrations of glycerol. Reactions were started by the addition of the substrate. In the case of NS31-180, Pep4AK was added to a final concentration of 100 μM. Cleavage products were quantified by HPLC as described in Materials and Methods. (C) Effect of ionic strength and Pep4AK on the protease activity of purified MutA protein. Two nanomolar MutA or NS31-180 protease was incubated with the NS5A-NS5B synthetic peptide substrate in the absence (empty bars) or presence (filled bars) of 100 μM Pep4AK. Where indicated, reaction mixtures were supplemented with 150 mM NaCl. (D) The protease activity of MutA NS3-NS4A purified protein is a linear function of the enzyme concentration. The purified MutA protease was incubated with the NS5A-NS5B synthetic peptide substrate at 0.01, 0.019, 0.037, 0.075, 0.15, 0.31, 1.25, and 2.5 nM. Reactions were carried out for 20 min in a buffer containing 15% glycerol and 150 mM NaCl.

The activity of this NS3-NS4A single-chain protein was characterized by using as the substrate a peptide corresponding to the NS5A/NS5B junction and compared to that of the recombinant NS31-180. The latter protease required Pep4AK and high glycerol concentrations for optimal activity (49). Glycerol presumably acted by stabilizing the complex of NS3 with the synthetic Pep4AK cofactor in an active conformation. Thus, we first ascertained whether the MutA protease also required glycerol for activity and found that it was highly and equally active at all tested glycerol concentrations (Fig. 11B). Therefore, we assessed the effect of ionic strength and Pep4AK in buffers containing 15% glycerol. As indicated by the results shown in Fig. 11C, MutA displayed about twofold-higher activity in buffer supplemented with 150 mM NaCl than in buffer without NaCl. Pep4AK stimulated the activity about twofold in no-salt buffer and had no effect in the presence of physiological salt concentrations. Under these experimental conditions, the NS31-180 protease was significantly less active than the MutA protease, was strictly dependent on the presence of Pep4AK, and was poorly affected by the presence of salt.

The Km and Kcat values of the MutA protease were 2.8 μM and 30 min−1, respectively, and were not affected by the presence of Pep4AK. The NS31-180 protease supplemented with Pep4AK and assayed in the presence of 50% glycerol had comparable parameters (Km = 4 μM; Kcat = 34 min−1). These results indicated that the two proteases had completely different requirements for maximal activity but showed the same overall catalytic efficiency when assayed under optimized conditions. They also indicated that the MutA protease was constitutively activated by the endogenous NS4A moiety. Activation occurred intramolecularly and not through the formation of homodimers or higher-order oligomers, since the enzyme activity remained constant at different concentrations (Fig. 11D) and analytical gel filtration experiments indicated that the protein eluted in a single peak, at an apparent molecular mass of approximately 24 kDa (data not shown), corresponding to its monomeric form.

DISCUSSION

The inability of HCV to replicate efficiently in cultured cells still represents a major limitation in the study of this virus. Despite significant efforts, none of the attempts to infect cultured cells with HCV have progressed to a level adequate to study the genetics of the virus and to test the efficacy of antiviral drugs. The recent identification of HCV molecular clones infectious in chimpanzees by intrahepatic injection has opened new perspectives for genetic analysis of HCV functions (31, 57). However, although this research is still in the early stages, there is no evidence that these clones are competent for replication in tissue culture cells. Thus, the possibility remains that inefficient replication in cultured cells is an intrinsic feature of HCV biology. In this perspective, surrogate systems based on artificial expression of HCV proteins still represent a valid alternative to studying viral enzymes.

The serine protease of HCV is considered a promising target for the development of a selective antiviral therapy, and the capacity to assess its activity in tissue culture cells is an important requisite to evaluate the efficacy of inhibitor compounds. We recently described the construction of chimeric SBVs whose propagation required the activity of this protease, and we proposed their use for the development of cell-based assays and as tools for a genetic approach to the study of this enzyme (15). In this paper we report the evolution of NS3-dependent chimeric viruses and the characterization of protease variants encoded by selected mutants. Chimeric viruses derived by transfection of in vitro-transcribed RNAs replicated inefficiently in BHK cells, and their subculture for several passages yielded mutant progeny viruses with an improved spreading ability. Interestingly, the NS3-NS4A proteases encoded by these mutants were different from those produced by the original chimeras but efficiently cleaved the cognate chimeric polyprotein in vivo and displayed a measurable activity in vitro on a bona fide HCV substrate.

The most important conclusion to be drawn from our data is that the strategy adopted to construct chimeric viruses proved to be adequate in making virus propagation stably dependent on the presence of a functional protease, thus rendering these viruses utilizable to generate, select, and characterize active variants of the protease itself. This conclusion confirms that chimeric viruses can be used as a tool to study the HCV serine protease with a genetic approach. From this perspective, the most relevant aspects of our results concern the correlation between the mutations found in the different protease variants, their activities, and the phenotypes of the cognate viruses.

First, it is worth noting that all of the selected protease variants contained the minimal active domains of NS3 and NS4A and that all mutations occurred far from the catalytic core of the enzyme (Fig. 9). In two variants, MutA and MutE, both selected at 30°C, deletion mutations were found. They comprised the helicase domain of NS3 and the amino terminus of NS4A, both dispensable for protease activity, and almost exactly mapped to the C terminus of the NS3 (MutE) and the N terminus of the NS4A (MutA) minimal domains. All other changes were point mutations. They occurred both in NS3 (MutA and MutB) and in NS4A (MutD, MutE, MutG, and MutH), and remarkably, in all cases the mutated residues either were directly involved in the NS3-NS4A interaction or were located in the NS4A domain which is required to stabilize the NS3-NS4A complex. These results indicated that although both NS3 and NS4A were required for in vivo processing of the chimeric polyprotein, alterations in the NS3-NS4A interaction were tolerated.

A second important consideration is that even though all selected proteases efficiently cleaved the chimeric polyprotein in vivo (Fig. 6), they showed considerable variation in basal and stimulated activities in vitro (Fig. 8). This difference between the various enzymes and the apparent discrepancy between the in vivo and in vitro data can be explained by considering the stability of the NS3-NS4A complexes.

The observation that the single-chain proteases encoded by MutA, MutB, MutC, and MutD were poorly activated by the Pep4AK cofactor (Fig. 8) suggested that in these enzymes NS3 and NS4A were tightly associated in functional complexes and that the NS3 and NS4A domains of the single-chain proteases interact intramolecularly. As discussed below, the data obtained with the recombinant MutA protease support this interpretation. Furthermore, the observation that the MutB, MutC, and MutD proteases displayed similar activities indicated that this intramolecular interaction was only marginally affected by the C16Y (MutB) and W28R (MutD) mutations. Consistently, modelling these mutations in the context of the protease structure predicted a slightly favorable or neutral effect on the stability of the NS3-NS4A interaction. The slight increase in activity of the MutA enzyme can be rationalized by assuming that the deletion found in MutA improves the reciprocal positioning of the two domains, thus generating a more stable and apparently more active protease.

The MutE protease displayed modest basal activity on the in vitro-translated substrate but was fully activated by the addition of the Pep4AK peptide. This result was in line with the observation that no NS3-NS4A complex was detected by coimmunoprecipitation with this variant enzyme (Fig. 7). Another observation in this direction is that the NS4A-dependent cleavage at the NS3-NS4A site was not complete in vivo, as demonstrated by the presence of a substantial amount of the 31-kDa ΔNS3-NS4A precursor (Fig. 6A and B, lanes 5). Also, modelling of the I25T mutation borne by this variant predicted an unfavorable effect on the stability of the NS3-NS4A interaction. The essential role of this residue for cofactor activity has been extensively demonstrated (4, 34, 46). In vitro, replacement of isoleucine 25 with serine significantly impaired the ability of a 14-mer NS4A peptide to activate the protease (46). In transfected cells, replacement of isoleucine 25 with aspartate only marginally affected the ability of a full-length NS4A to form a stable complex with NS3 and had no effect on protease activation (4). Thus, the most likely interpretation of our data is that the I25T mutation found in the MutE protease decreases the affinity of the NS3-NS4A interaction and that this reduced affinity is responsible for the low basal activity observed in the in vitro assay. In vivo, however, the intracellular concentrations of NS3 and NS4A are probably high enough to compensate for this reduced affinity, so that the protease efficiently processes the polyprotein.

The proteases encoded by MutG and MutH displayed only modest in vitro activity, although they had only one (MutH) or two (MutG) point mutations in the hydrophobic amino-terminal domain of NS4A (Fig. 9). Deletion experiments with transfected cells have shown that this domain is required for stabilization of the NS3-NS4A complex but is dispensable for activation of the protease (4). Furthermore, because of its hydrophobic nature, this domain of NS4A was postulated to be responsible for the membrane anchoring of the NS3-NS4A complex (51). Our data can be interpreted in line with these findings. The mutated NS4A proteins encoded by MutG and MutH were barely detectable by immunoblotting (Fig. 6B, lanes 6 and 7), but the NS3-NS4A complexes encoded by these two mutants could be immunoprecipitated as effectively as the wt complex (Fig. 7). Thus, the most likely interpretation of our results is that A14D and W3R mutations do not significantly interfere with the formation of a stable and active complex between NS3 and NS4A but do impair the ability of NS4A to interact productively with the endoplasmic reticulum membrane, thus causing its rapid degradation. Degradation of NS4A presumably leads to the inactivation and eventual degradation of NS3. Indeed, Tanji et al. have shown that NS4A increases the metabolic stability of NS3 (51). In this view, the MutG and MutH enzymes would be fully active but short-lived, thus accounting for the very poor activity observed in vitro as well as for the inability to perform the NS4A-dependent self-cleavage that generates the 47-kDa NS3ΔH protein (Fig. 3 and 6). An alternative interpretation is that the amino-terminal portion of NS4A does not interact with the membrane but stabilizes the complex by direct contact with NS3. Consequently, mutations in this region could affect the overall structure of the NS3-NS4A complex and, as a result, the activity and/or stability of the enzyme.

Considered from a genetic point of view, our results indicate that the different variants of the protease gene play a role in determining the plaque phenotypes of corresponding chimeric viruses. Although all chimeric viruses were still significantly impaired in their ability to grow on BHK cells compared to wt SBV, they showed differences in plaque phenotypes which could be correlated with mutations in the protease gene. In particular, the different plaque phenotypes of the Mut5, FL5, Mutα, and Mutɛ viruses clearly indicated that mutations in the protease gene, which represented the only differences between these viruses, affected the ability of the viruses to propagate in BHK cells (Fig. 1 and 10). On the other hand, the observation that viruses with an identical protease gene (Fig. 10, compare MutA to Mutα and MutE to Mutɛ) displayed different plaque phenotypes showed that, as expected, mutations outside the protease gene also affected the spreading abilities of the different viruses. Since the Mutα and Mutɛ viruses showed a plaque phenotype intermediate between those of the parental (Mut5 and FL5) and evolved (MutA and MutE) viruses, we hypothesize that mutations in the protease gene and those occurring elsewhere influence the propagation ability of the viruses cooperatively and that neither is sufficient to determine the full phenotype of the virus. Indeed, MutG and MutH also had a mutation at the C/PE2 junction that could intuitively be thought to be coselected with those found in the protease gene. In sum, we can conclude that different variants of the protease gene affect, in concert with other mutations, the phenotypes of the chimeric viruses. Nonetheless, it is difficult to tell whether the mutations found in the protease genes of evolved viruses were selected because of their specific effect on the virus phenotype or simply by cosegregation with other favorable mutations.

The molecular mechanisms by which the mutations in the protease gene affect the plaque phenotypes of the different viruses remain speculative, and our data can be interpreted in the light of three non-mutually exclusive hypotheses.

The first, and probably most intriguing, hypothesis is that mutations in the protease gene affect the activity and/or stability of the protease itself and that this in turn has a favorable effect on the virus phenotype. The subculture routine we employed for the evolution was such that no specific selective pressure for a more active protease could be predicted. In fact, although protease activity was essential for propagation, the level of activity required could not be determined a priori. Thus, it is conceivable that rather than being selected for an absolute increase in activity, the mutations found in the protease genes were selected for their ability to process the polyprotein in a timely manner. One possibility is that mutations change the enzyme specificity. This hypothesis could account for the observation that the MutG and MutH viruses had mutations both in the protease and in the C/PE2 cleavage site. Furthermore, a striking feature of the C16Y (MutA and MutB), R28W (MutD), and I25T (MutE) mutations was that they were localized within the same region of the protease-cofactor complex (Fig. 9B). The side chains of NS3 residue 16 and those of NS4A residues 25 and 28 all fall within an area of less than 30 Å2. No structure of the enzyme complexed with substrate is known. However, when we modelled the substrate according to the canonical serine protease substrate binding mode, we observed that the region where these mutations map corresponds roughly to the part of the enzyme expected to interact with the P′ site of the substrate. This region is about 20 Å from the P1 site, a position that, according to our modelling, would contact the P′5 or P′6 position of a substrate in an extended conformation. It is very tempting to speculate that, since the cleavage sites that we engineered in our chimeric molecules mimic the specific HCV substrate only up to P′4, these mutations might optimize binding of positions C terminal to the engineered cleavage site.

A second hypothesis to explain the effect of mutations is that rather than influencing the protease activity, they suppress one or more functions which interfere with virus replication or assembly. The deletion of the NS3 helicase observed in MutE could be interpreted as a knockout of its function. In fact, the NS3 helicase activity is not required for viability of chimeric viruses, and it might have a deleterious effect on virus replication. Similarly, deletion of the amino terminus of NS4A (MutA) or point mutations in the same region (MutG and MutH) could be interpreted as a way of preventing the association of NS4A with the membrane. It is conceivable that the presence of this protein in the membrane interferes with virus assembly.

Finally, another hypothesis is that mutations in the protease gene affect the virus phenotype simply because they influence the size of the viral genome. A survey of SBV mutants and vectors suggests that genomes of wt size or smaller have a selective advantage in propagation, possibly because they are more efficiently packaged into mature virions, but no clear upper or lower limit to the genome size has been defined. Consistently, two of the seven mutants we selected showed a deletion of HCV sequences, and recloning these shorter versions of the protease gene into the original chimeric genome resulted in an improved plaque phenotype. However, this hypothesis cannot explain the other five selected mutants, in which changes in the size of the genome were not observed. Surprisingly, both deletion mutants were obtained from passaging at 30°C. This result can be interpreted by assuming either that the SBV replication machinery is more prone to recombination events at 30°C or that, for unknown reasons, at this temperature smaller chimeric genomes are more easily selected. It would be interesting to investigate whether this temperature dependence in the selection of deletion mutants is inherent only to NS3-dependent chimeric viruses or is a more general phenomenon of SBV replicons.

The NS3 protein encompasses two enzymatic activities which are probably regulated during HCV replication. NS3 and NS4A interact with other viral proteins to form a multiprotein complex which presumably represents the core of the HCV replication machinery (35). These events cannot be reproduced by our chimeric viruses. However, our data indicate that evolution of chimeric viruses yielded variants of the NS3-NS4A protease that were remarkably similar to the original enzymes. The possibility of manipulating the genomes of chimeric viruses provides the opportunity to generate repertoires of chimeric viruses encoding natural variants of the NS3-NS4A protease. These repertoires can be used for the selection of variants with desired properties, provided that an appropriate selective pressure is used. The most promising application of this feature is the possibility of selecting and characterizing protease variants with decreased sensitivity to inhibitors. Several in vitro assays have been developed to screen for NS3-NS4A protease inhibitors, and it is probable that potent and selective compounds will be identified in the near future. Passaging of repertoires of chimeric viruses in the presence of gradually increasing concentrations of inhibitors should result in the emergence of virus variants that can evade the drug action. Characterization of the enzymes encoded by these variants should allow understanding of the structural basis for drug resistance and help in the design of compounds with a broader activity.

Understanding the NS3-NS4A interaction is critical for the development of protease inhibitors. One approach to study this interaction is based on the design and production of functional NS3-NS4A fusion proteins. This approach requires the determination of the minimal domains of NS3 and NS4A and of the correct link between them. The architecture of such fusion proteins poses several problems related to the proper positioning of the NS3 and NS4A domains and to the stability and solubility of the resulting molecules. The MutA protease provided a serendipitous answer to this problem. Our initial characterization of the recombinant MutA protease revealed that this enzyme variant possessed a number of biochemical properties which make it an attractive candidate for further enzymological studies. The first interesting property was its high solubility. Bacterial expression of the NS3-NS4A protease encoded by the original Mut5 virus yielded only minute amounts of insoluble protein (data not shown). In contrast, expression of the MutA protease without any solubilizing tag yielded about 1 mg of a 40% soluble protein per liter of bacteria, and the addition of the lysine tail increased the yield and solubility by about twofold (Fig. 11A and data not shown). The recombinant MutA protease displayed the same overall catalytic activity as the recombinant NS31-180 protease but did not require the presence of glycerol and the synthetic Pep4AK cofactor for maximal activity. In addition, the observation that the MutA protease was in a monomeric form and could not be activated by the Pep4AK peptide even at very low concentrations indicated that the NS3-NS4A interaction occurred intramolecularly. This feature was probably responsible for the glycerol independence of the MutA enzyme and indicated that this variant protease was more stable than the NS31-180 protease complexed with the Pep4AK peptide. This improved stability and the less strict requirements of the MutA enzyme for maximal activity make this variant enzyme a promising candidate for screening assays as well as for structural studies by nuclear magnetic resonance or X-ray crystallography.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank C. Steinkühler for helpful discussion and critical review, J. Clench for editing the manuscript, M. Emili for graphics, and P. Neuner for oligonucleotide synthesis. We are grateful to R. Cortese for continous support and encouragement.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barnes W M. PCR amplification of up to 35-kb DNA with high fidelity and high yield from lambda bacteriophage templates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2216–2220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartenschlager R, Ahlborn-Laake L, Mous J, Jacobsen H. Kinetic and structural analysis of hepatitis C virus polyprotein processing. J Virol. 1994;68:5045–5055. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.5045-5055.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartenschlager R, Ahlborn-Laake L, Mous J, Jacobsen H. Nonstructural protein 3 of hepatitis C virus encodes a serine-type proteinase required for cleavage at the NS3/4 and NS4/5 junctions. J Virol. 1993;67:3835–3844. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.3835-3844.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bartenschlager R, Lohman V, Wilkinson T, Koch J O. Complex formation between the NS3 serine-type proteinase of the hepatitis C virus and NS4A and its importance for polyprotein maturation. J Virol. 1995;69:7519–7528. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.7519-7528.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bianchi E, Urbani A, Biasiol G, Brunetti M, Pessi A, De Francesco R, Steinkühler C. Complex formation between the hepatitis C virus serine protease and a synthetic NS4A co-factor peptide. Biochemistry. 1997;36:7890–7897. doi: 10.1021/bi9631475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bukh J, Miller R H, Purcell R H. Genetic heterogeneity of hepatitis C virus: quasispecies and genotypes. Semin Liver Dis. 1995;15:41–63. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chomczynski P, Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987;162:156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]