Abstract

Sin Nombre virus (SNV), a member of the Hantavirus genus, causes acute viral pneumonia in humans and is thought to persistently infect mice. The deer mouse, Peromyscus maniculatus, has been identified as the primary reservoir host for SNV. To understand SNV infection of P. maniculatus, we examined wild deer mice for localization of viral antigens and nucleic acid. Morphologic examination consistently revealed septal edema within lung tissue and mononuclear cell infiltrates in portal areas of the liver. Immunohistochemical analysis of SNV-infected deer mice identified viral antigens within lung, liver, kidney, and spleen. The lungs consistently presented with the highest levels of viral antigen by immunohistochemistry and with the highest levels of nucleic acid by reverse transcriptase (RT) PCR. The mononuclear cell infiltrates surrounding liver portal triads were positive for SNV antigens in addition to resident macrophages in liver sinuses. Spleen tissue contained antigens in both the red pulp and the periartereolar region of the white pulp. The kidney presented with no gross pathology, although antigens could be localized to glomeruli. Virus antigen levels within the kidney were highest in deer mice that did not have antibodies to SNV but contained viral nucleic acid detectable by RT PCR. Since transmission is thought to occur via urine, our results suggest that virus transmission may be highest in the early stages of infection. In addition, these results indicate that SNV does cause some pathology within its reservoir host.

In 1993, an outbreak of an unexplained pulmonary illness in the southwestern United States was found to be caused by a newly described hantavirus designated Sin Nombre virus (SNV) (7, 23). The primary reservoir host for SNV was identified as the deer mouse, Peromyscus maniculatus (4, 22, 23). Subsequently, several other New World hantaviruses and their reservoir hosts have been identified. These include Black Creek Canal virus in the cotton rat, Sigmodon hispidus (26, 27); New York virus in the white-footed mouse, Peromyscus leucopus (29); Bayou virus in the rice rat, Oryzomys palustris (21, 32, 33), and El Moro Canyon and Rio Segundo viruses in harvest mice from the genus Reithrodontomys (11, 12).

The Old World hantaviruses, including Hantaan, Puumala, and Seoul viruses, cause a disease in humans, termed hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome (2, 3, 16), which has a wide range of severity, from asymptomatic to renal failure and death. SNV, in contrast, results in a disease designated hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS) (1, 6, 13, 14, 30). Characteristic symptoms of HPS include an initial febrile prodrome with the ensuing onset of noncardiogenic pulmonary edema and hypotension. The primary histopathological features of HPS include interstitial pneumonitis and hyaline membrane formation, which is likely caused by infection of pulmonary endothelium by SNV (10, 24, 35). SNV has also been shown to be widely distributed within vascular endothelium throughout many organs, including lung, liver, spleen, kidney, pancreas, and lymph nodes (35). SNV infects cells of the immune system, including follicular dendritic cells, macrophages, and lymphocytes (35).

Rodent infections, caused by other members of the Hantavirus genus, have been previously described (17, 18, 31, 34). These Old World hantaviruses, including Hantaan, Seoul, and Puumala viruses, each have distinct reservoir hosts. Studies examining laboratory-inoculated rodents found that these animals were systemically infected (18, 34). In the reservoir for Hantaan virus, the striped field mouse (Apodemus agrarius) virus persisted up to 180 days postinfection, and antigen, not infectious virus, was detectable for 1 year after infection (18). Lee et al. (18) found that A. agrarius contained viral antigens in many organs, including lung, liver, and kidney. In Puumala virus-infected bank voles (Clethrionomys glareolus) there was a strong correlation with virus antigen levels and the titer of the rodent immune response to the virus (8). As the infected rodents generated an immune response, the amount of viral antigens decreased but persisted in the lung and other tissues for up to 1 year (8). Seoul virus infections of its reservoir host, the Norway rat (Rattus norvegicus), were found to resemble those with the Hantaan and Puumala viruses (31, 34). In these studies, the animals contained high amounts of viral antigens, particularly in the lungs, for over 1 year postinfection, with no histopathology, suggesting that these reservoir hosts were persistently infected.

Pathogenesis caused by Sin Nombre-like North American hantaviruses in rodent reservoirs has recently been reported for the New York virus in P. leucopus (19). Ultrastructural analysis of P. leucopus organs revealed viral particles in pulmonary endothelium. Morphological findings included immune infiltrates in portal zones of the liver and edema of alveolar septa in the lungs. These findings suggested that P. leucopus may not be an asymptomatic carrier of New York virus and could serve as a model for HPS (19).

With the recent elucidation of HPS pathology in humans (24, 35), and lung pathology caused by New York virus in P. leucopus (19), we were interested in determining the pathological effects of Sin Nombre virus in the deer mouse. Specifically, we wanted to determine if the virus infection resulted in a persistent, acute, or latent infection. An immunohistochemical approach was used to ascertain if SNV-infected P. maniculatus mice have pathologic features similar to HPS or are true asymptomatic reservoir hosts. Blood from wild-caught deer mice was first examined for antibodies to SNV by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and for the presence of SNV RNA by (RT) PCR. Based upon results obtained from the examination of blood, deer mice were separated into four groups for further analysis by immunohistochemistry.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Rodents.

All SNV-positive P. maniculatus mice utilized were adults caught in Nevada and California as previously described (25). Rodents were collected by using Sherman live traps (H. B. Sherman Trap Co., Tallahassee, Fla.). Animals were removed from the traps, and a sample of blood was collected from the retroorbital sinus with a heparinized capillary tube. Mice were then sacrificed by cervical dislocation and frozen on dry ice for transport to the BSL-3 lab. Partially thawed mice were dissected, and organs were aliquoted for further analysis. For histological examination, semifrozen tissue was fixed in buffered formalin and for RT PCR, tissue was refrozen at −80°C until RNA was extracted. Negative P. maniculatus were wild caught or purchased from a colony at the University of South Carolina, Columbia.

Antibodies.

Monoclonal antibody GB04-BF07 to Puumala virus nucleoprotein and cross-reactive with SNV nucleoprotein and affinity-purified mouse antinucleoprotein antibody specific for SNV were obtained from Tom Ksiazek, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga. Hyperimmune rabbit anti-SNV serum was also obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

ELISA.

Detection of antihantavirus antibodies was performed as previously described (25). Microtiter plates were coated with recombinant nucleocapsid antigen, and heat-inactivated P. maniculatus serum was added to coated wells. After incubation, anti-Peromyscus horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody was added. Plates were then incubated with substrate solution [2,2′-azino-di-(3-ethylbenzthiozaline-sulfonate)] (ABTS), and absorbance at 405 nm was recorded. P. maniculatus serum was considered positive if the absorbance value was greater than the mean value plus 3 standard deviations from negative control wells.

RNA isolation and RT PCR.

Methods used for detection of SNV RNA were as described previously (28). In short, RNA from blood clots and rodent organs was extracted by using an RNAid Plus kit (Bio 101, La Jolla, Calif.) and amplified with hantavirus-specific primers by nested RT PCR. Primers utilized for S-segment amplification were forward first-round 5′ TGTGTGTTTGGAGACCCTGG 3′ and reverse 5′ TC(A-G)ATAGATTGTGTATGCA 3′. Second-round primers were forward 5′ ATGTCAACAAC(A-G)AGTGGGATG 3′ and reverse 5′ CATGGGTTATCACTTAG(G-A)TC 3′. This amplifies a 211-bp fragment corresponding to positions 143 to 353. Primers utilized for M-segment amplification were forward first-round 5′ GGAATGAGCACCCTCAAAGAAGTGCAAGACAAC 3′ and reverse 5′ CAAGTGGGCAAACAGCTGA 3′. Second-round M segment primers were forward 5′ TGGACCC(A-C)GATGA(C-T)GTTAACAA 3′ and reverse 5′ ACATCAAGGACATT(T-C)CCATA 3′. This amplifies a 280-bp fragment corresponding to positions 2689 to 2969. Products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis and direct sequencing.

Immunohistochemistry.

Deer mouse tissue was dissected and fixed in phosphate-buffered formalin, processed, and embedded in paraffin. Sections were cut at 5 μm and mounted onto slides. The sections were deparaffinized and digested with a solution of 0.6 M Tris (pH 7.5), 0.1 mg of proteinase K per ml, and 0.1% calcium chloride. Viral antigens were localized by using a Vectastain ABC-AP kit (Vector Labs, Burlingame, Calif.) or Signets Ultra Strepavidin as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Sections were blocked with 10% serum and incubated with primary antibody. The sections were then incubated with appropriate biotinylated secondary antibody. Following the addition of secondary antibody, a complex of avidin and biotinylated alkaline phosphatase (ABC-AP) was added. The final step was the addition of Vector red alkaline phosphatase substrate. Sections were then counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted with permount (Fisher Scientific). The following controls were also included in immunohistochemical examination: (i) phosphate-buffered saline in place of primary monoclonal antibody or (ii) both primary and secondary antibodies to show specificity of immune reagents. Control antibodies were purchased from Vector Labs and consisted of antibodies that were purified from the pooled sera of healthy adult animals. The purified antibodies contain a spectrum of the immunoglobulin G subclasses present in serum. Both mouse and rabbit control antibodies were utilized to ensure that staining observed with SNV antibodies was not nonspecific absorption to rodent tissue.

Microscopy.

All images were visualized with a Nikon Eclipse E 800 microscope. Digital images were captured by using a Photonic Sciences charge-coupled device camera (Millham, United Kingdom) and Image Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Springs, Mass.). Digitized images were focused by using a sharpening algorithm provided with Image Pro Plus software.

RESULTS

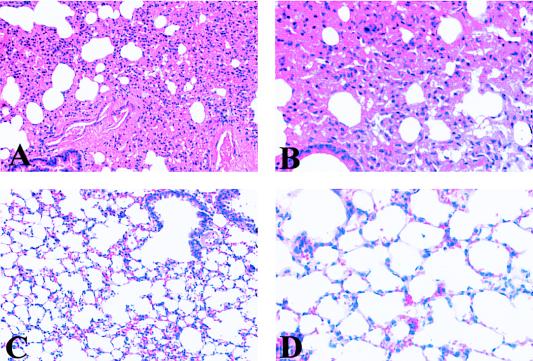

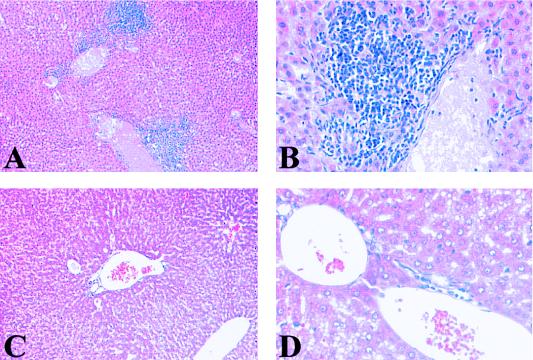

To determine if SNV infection in deer mice is associated with identifiable pathologic changes and to determine the distribution of viral antigens in rodent tissues, we utilized wild-caught P. maniculatus mice. Mice were bled from the retro-orbital socket of the eye and tested for SNV antibodies by ELISA and screened for SNV RNA by RT PCR (Table 1). Based on ELISA and RT PCR results from blood, the deer mice were divided into four groups as follows: (i) uninfected rodents (ELISA negative; RT PCR negative), (ii) recently infected rodents (ELISA negative; RT PCR positive), (iii) rodents with acute infection (ELISA positive; RT PCR positive), and (iv) rodents with chronic infection (ELISA positive; RT PCR negative). Based on these serological findings, we suggest that the rodents in group 2 were recently infected because they had not yet produced an immune response to SNV, although viral RNA was present in the blood. The group 4 rodents appeared to be in a late stage of infection, since viral RNA had disappeared from the blood. After serological and RT PCR examination of the blood, 25 mice were examined for the presence of SNV RNA in organs by RT PCR and for the presence of pathology by standard histological techniques. Lung, liver, kidney, and spleen were sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for morphological examination. Figures 1A and B illustrate deer mouse lung tissue with septal edema associated with SNV infection in P. maniculatus. The lungs of most infected rodents had some alveolar septal edema, in contrast to SNV-negative P. maniculatus lungs, which did not contain any edema (Fig. 1C and D). Other consistent morphologic findings include immune infiltrates in portal zones of SNV-infected P. maniculatus liver (Fig. 2A and B). Figures 2C and D illustrate normal liver portal morphology. The spleens and kidneys of infected deer mice showed no abnormal tissue morphology compared with those of uninfected P. maniculatus mice.

TABLE 1.

ELISA, RT PCR, and morphologic analysis results for SNV-infected P. maniculatus

| Group | Mouse | Sexc | ELISA | RT PCR resultsb

|

H & Ea

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood | Lung | Liver | Kidney | Bladder | Lung edema | Liver infiltrate | ||||

| 1 | 1 | M | Negative | Negative | Negative | ND | Negative | ND | − | − |

| 2 | F | Negative | Negative | Negative | ND | Negative | ND | − | − | |

| 3 | F | Negative | Negative | Negative | ND | Negative | ND | − | − | |

| 2 | 4 | F | Negative | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | ++ | − |

| 5 | F | Negative | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | + | +++ | |

| 6 | F | Negative | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | + | ++ | |

| 7 | M | Negative | Positive | Positive | ND | Positive | ND | − | − | |

| 3 | 8 | M | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | +++ | +++ |

| 9 | M | Positive | Positive | Positive | ND | Positive | ND | ++ | ++ | |

| 10 | M | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Negative | +++ | ++ | |

| 11 | M | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Negative | Negative | +++ | − | |

| 12 | M | Positive | Positive | Positive | Negative | Negative | Positive | +++ | ++ | |

| 13 | M | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Negative | Positive | + | − | |

| 14 | M | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Negative | +++ | + | |

| 15 | M | Positive | Positive | Positive | ND | Negative | ND | +++ | + | |

| 16 | M | Positive | Positive | Positive | ND | Negative | ND | +++ | ++ | |

| 4 | 17 | M | Positive | Negative | Negative | ND | Negative | Negative | ++ | + |

| 18 | M | Positive | Negative | Positive | Positive | Negative | Negative | +++ | ++ | |

| 19 | M | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | Positive | ++ | − | |

| 20 | F | Positive | Negative | Positive | Positive | Negative | Negative | ++ | ++ | |

| 21 | M | Positive | Negative | Negative | ND | Negative | Negative | ++ | ++ | |

| 22 | M | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative | +++ | ++ | |

| 23 | F | Positive | Negative | Positive | ND | Positive | Negative | +++ | + | |

| 24 | M | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | + | − | |

| 25 | F | Positive | Negative | Positive | ND | Negative | ND | + | ++ | |

H & E, hematoxylin and eosin stained; +++, severe; ++, moderate; +, mild; −, negative.

ND, not determined.

M, male; F, female.

FIG. 1.

Morphologic examination of lung tissue from P. maniculatus mice. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin-stained lung tissue from an SNV-infected rodent, illustrating large amounts of edema in alveolar septum. (B) High magnification showing thickening of alveolar walls in lungs of infected rodents. (C and D) Hematoxylin and eosin-stained lung tissue from an uninfected deer mouse, illustrating normal lung morphology with open and thin walls of alveoli. (Magnification: panels A and C, ×200; panels B and D, ×400).

FIG. 2.

Morphologic examination of P. maniculatus liver tissue by hematoxylin and eosin staining. (A and B) Hematoxylin and eosin-stained liver tissue from an SNV-infected rodent, showing large amounts of mononuclear cell infiltrates surrounding a portal vein. (C and D) Uninfected liver tissue, illustrating the absence of infiltrates in normal rodents. (Magnification: panels A and C, ×200; panels B and D, ×400).

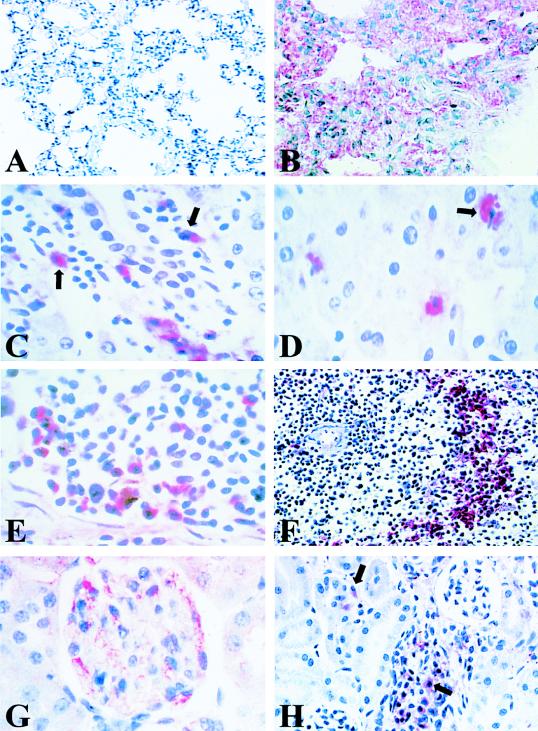

To determine if the pathological morphology present in liver and lung was associated with the expression of SNV antigens, we examined P. maniculatus tissues for the presence of viral proteins. Lung was the first organ examined, because it has been shown in other hantavirus-infected rodent reservoirs to contain large amounts of viral antigens. Infected deer mice contained various levels of SNV antigens (red staining) within their lungs. Viral antigens were localized to edematous tissue, especially alveolar septa (Fig. 3B). Some animals had SNV antigens distributed throughout the lung section, while other mice had more focal staining of antigens. Normal lung did not contain any antigen staining (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

Immunohistochemical examination of SNV-infected P. maniculatus tissue. (A) Absence of immune staining in normal P. maniculatus lung tissue (B). Infected lung tissue, showing localization of SNV antigens (red) to alveolar and capillary walls. (C) SNV antigen-positive cells in the liver of an infected rodent, illustrating immunolocalization of SNV antigens (red) to mononuclear infiltrates (arrow) surrounding a liver portal vein. (D) SNV-positive Kuppfer cells (arrow) in liver sinuses. (E) Spleen tissue (red pulp), illustrating localization of viral antigens to mononuclear cells. (F) Characteristic reticular staining pattern found within the white pulp of infected rodent spleens. (G) Immunolocalization of SNV antigens to endothelial cells of a glomerulus in the kidney cortex of an infected deer mouse. (H) Staining pattern of a kidney, illustrating mononuclear cells (arrow) infected with SNV in a convalescent-stage rodent. (Magnification: panel A, ×200; panels B and F, ×400; panels C to E and H, ×600).

Immunohistochemical analysis of the liver localized viral antigens to infiltrating mononuclear cells (Fig. 3C) and Kuppfer cells within liver sinuses (Fig. 3D). In some rodents, evidence of viral antigens was found in hepatocytes (data not shown). In contrast, liver from uninfected animals contained no virus antigen or mononuclear infiltrates.

Examination of P. maniculatus spleen from infected animals revealed SNV antigens in mononuclear cells within both red and white pulp (Fig. 3E and F). Figure 3E shows viral antigens within mononuclear cells in the red pulp of the spleen. Figure 3F illustrates the reticular staining pattern found within the white pulp of the spleen in infected rodents. SNV-negative spleen tissue did not contain viral antigen staining (data not shown).

The kidneys of infected P. maniculatus showed no gross pathological changes compared with those of normal deer mice. Upon immunohistochemical analysis, viral antigens were found to produce focal staining to no staining in infected rodents. Group 2 rodents (ELISA negative; RT PCR positive) had the greatest amount of viral antigens. Figure 3G shows infected endothelium within a kidney glomerulus. As rodents developed an immune response to SNV, the amount of viral antigens dropped dramatically. Interestingly, a few rodents in group 4 (ELISA positive; RT PCR negative) had focal staining localized to infiltrating mononuclear cells (Fig. 3H).

DISCUSSION

In humans, Sin Nombre virus causes a disease termed HPS (1, 5, 6, 13, 14). Pathologic findings in humans demonstrate that SNV primarily infects endothelial cells of the microvasculature, especially in human lungs, which is likely the reason for the severe edema associated with HPS (24, 35). The main pulmonary histopathological findings include interstitial pneumonitis, hyaline membrane formation, and mononuclear cell infiltrates (24, 35). We were surprised that P. maniculatus mice infected with SNV had changes in tissue morphology similar to those associated with SNV infections in humans. Deer mice consistently had septal edema of lung tissue and mononuclear infiltrates surrounding hepatic portal triads. These findings are in agreement with those reported for P. leucopus mice infected with New York hantavirus (19) and have similarities with those for human pathogenesis (24, 35). However, these results were in contrast to those for classical infections of rodents with other members of the Hantavirus genus. The major finding of previous studies, which examined infections of reservoir hosts, was that organs, including lung, liver, and kidney, contained viral antigens without the presence of detectable tissue pathology (17, 18, 31, 34).

To correlate tissue pathology observed in P. maniculatus lungs and livers with SNV infection, immunohistochemistry was performed to localize viral antigens within various organs. Immune staining of deer mice revealed viral antigens in lung, liver, kidney, and spleen. Lungs presented with the greatest amount of viral antigens localized to alveolar septum. Lungs from mice that were ELISA and RT PCR positive invariably had the greatest amount of viral antigens and associated pathology of all rodents examined. These findings suggest that rodent reservoirs for SNV may not be asymptomatic carriers and that lung morphology may be an indication of viral infection. Although there is an excellent correlation between the presence of SNV antigens and observed edema in the lungs of infected P. maniculatus mice, we cannot rule out the possibility that mice were concurrently infected with another rodent pathogen present in their natural environment. Indeed, we found an SNV-negative rodent with pulmonary edema, suggesting that agents besides SNV can cause pulmonary manifestations in P. maniculatus mice. Although the majority of areas where we observed edema were associated with SNV antigens, we have detected SNV antigen staining in areas of the lung without edema, which could represent newly infected sites. We occasionally observed edema in SNV-infected animals which did not contain SNV antigens, suggesting that another pathogen was contributing to the edema or that inflammatory cytokines were inducing the pathology. Interestingly, we found that 1 of the 25 rodents examined (no. 13) contained only focal areas of edema and a lack of immune infiltrate around portal triads in the liver. However, this rodent was ELISA positive and contained SNV RNA in its blood, lungs, liver, and bladder. Our ability to localize viral antigens to both edematous and normal lung tissue suggests that this rodent was more recently infected than the other rodents in group 3. Overall, the amount of edema in lung tissue seemed to decrease in the rodents that no longer had detectable virus in the blood, and immunohistochemical staining revealed more focal localization of viral antigens. This finding suggests that the edema found in lung tissue is a result of acute infection with SNV and that as the persistent or chronic state develops, the septal edema is being resolved. The finding that SNV remains in lungs of infected rodents after the virus has been cleared from the blood is evidence for viral persistence in these rodents. Examination of laboratory-infected rodents (which requires a BSL-4 facility) may help to answer the question of whether direct damage to the vascular endothelium caused by SNV or host immune responses and cytokine mediators causes the edema observed in these rodents.

Immune infiltrates in infected liver tissue were the second-most-consistent pathologic finding observed in infected deer mice. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed viral antigens in infiltrating cells and suggests that SNV may become systemic by means of replication in monocytes/macrophages or lymphocytes.

Immunohistochemical examination of the spleen revealed antigens in both lymphoid (white pulp) and erythroid (red pulp) compartments. Detection of viral antigens in white and red pulp of the spleen, which contains numerous cell types, including monocytes, lymphocytes, and follicular dendritic cells, suggests that immune cells may be infected with SNV.

The organ most surprising to us was the kidney. Antigen staining in this organ was quite variable from rodent to rodent. Deer mice in group 2 (ELISA negative; RT PCR positive) contained the highest concentration of viral antigens. Only 8 of 25 rodents (32%) were RT PCR organ positive, suggesting a low overall percentage of viral nucleic acid within the kidney. The highest percentages of kidney RT PCR-positive mice were in group 2 (ELISA negative; RT PCR positive) and group 3 (ELISA positive; RT PCR positive), with 50 and 55%, respectively, in agreement with immunohistochemistry data. In contrast, in group 4 mice (ELISA positive; RT PCR negative) only 22% of the kidneys were RT PCR positive. These data suggest that P. maniculatus mice may be shedding the greatest amount of virus in urine during earlier stages of infection. Immunohistochemical analysis of group 4 mice revealed focal or no viral antigen staining, but staining was observed in circulating mononuclear cells within the kidney. These results are consistent with studies examining Hantaan and Puumala viral infections of rodent hosts (8, 17, 18). Lee et al. (18) found that viral antigens in the kidneys of striped field mice were widely scattered and that infectious virus isolation from this organ could be accomplished only up to 45 days postinfection. Gavrilovskaya et al. (8) had similar results with Puumala virus infection in bank voles, although infectious virus could be isolated up to 13 months postinfection. In addition, Gavrilovskaya (8) found that the ability of bank voles to horizontally transmit virus to cagemates was directly correlated to level of humoral immunity. Our data are similar to those from previous studies in regard to viral antigen levels in rodents without detectable humoral immunity. We discovered that in SNV infection there was an inverse correlation between the antibody level and the amount of viral antigens present in the kidney. These results suggest that the rodent immune system is decreasing the amount of virus, thereby decreasing the quantity of infectious virus shed in excreta. This assumption, in turn, suggest that the infection rates of at-risk groups (mammalogists) are low, despite the high frequency of infection and broad geographic range of P. maniculatus mice, because deer mice secrete the highest amount of infectious virus during the early or acute stages of disease, when antibodies to SNV are absent. An additional observation of interest was that three of the four group 2 mice (ELISA negative; RT PCR positive) were juveniles as determined by the fact that their body masses were less than 12 g. (The three rodents had body masses of 11, 11, and 10.5 g.) This fact is interesting because it has been reported that hantavirus infection in rats (R. norvegicus) could be attributable to the onset of puberty and to increases in aggressive behavior (9). These data suggest that hantavirus infection in P. maniculatus mice could also be attributable to the onset of puberty but may reflect the small sample size of this group.

These data suggest that P. maniculatus mice are persistently infected with SNV as are other hantavirus reservoir hosts. Persistence is a situation in which infectious virus is present, usually at low levels, in host cells for long periods without killing or seriously impairing the host. Studies examining Hantaan virus infection of its reservoir host, the striped field mouse, found that the virus persists in these rodents for at least 1 year (18). Puumala virus infection in its reservoir host, the bank vole, was found to persist for up to 13 months postinfection (8). These previous studies were performed in a controlled laboratory setting in which investigators could examine rodents for up to 1 year postinfection. We could not reproduce these studies because of the need for a BSL-4 containment facility, so wild-caught infected rodents were utilized in these studies. Therefore, we could not definitively determine when rodents became infected with SNV or whether the animals were proceeding through cycles of infection, clearance, and reinfection.

Recently, Black Creek Canal virus infection was examined in experimentally inoculated S. hispidus (15). The investigators found that S. hispidus was persistently infected with Black Creek Canal virus and that the infection could be divided into an acute and a chronic phase. The acute phase was correlated with the highest viral titers as measured by dilution of organ lysates on Vero E6 cells, and the chronic, or persistent, stage was associated with a decrease in the amount of infectious virus in tissue homogenates (15). Nevertheless, infectious virus was still detectable in excreta during the chronic stages of infection. Our examination of naturally acquired SNV infection in P. maniculatus fits well with the experimental results found with Black Creek Canal infection of S. hispidus. Experimental infections of P. maniculatus need to be performed in order to monitor temporal changes in viral accumulation in organs of infected animals. These experiments will clarify when infected deer mice are capable of transmitting infectious virus to naïve cagemates. Studies examining the seroprevalence of SNV antibodies in deer mice have found that seropositivity was higher in adult males, suggesting horizontal transmission among these rodents (20). However, immunohistochemical analysis of male and female deer mice revealed no differences in antigen localization or quantity. An additional question that should be addressed is whether SNV-infected P. maniculatus dams vertically transmit virus to their offspring.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grants AI 36418 and AI 39808 and by National Cancer Institute grant CA 09563.

REFERENCES

- 1.Butler J C, Peters C J. Hantaviruses and hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:387–395. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen L, Yank W. Abnormalities of T cell immunoregulation in hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:1016–1019. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.5.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Childs J E, Glass G E, Ksiazek T G, Rossi C A, Barrera Oro J G, LeDuc J W. Human-rodent contact and information with lymphocytic choriomeningitis and Seoul viruses in an inner-city population. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1991;44:117–121. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1991.44.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Childs J E, Ksiazek T G, Spiropoulou C F, Krebs J W, Morzunov S, Maupin G O, Gage K L, Rollin P E, Sarisky J, Enscore R E, Frey J K, Peters C J, Nichol S T. Serologic and genetic identification of Peromyscus maniculatus as the primary rodent reservoir for a new hantavirus in the southwestern United States. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:1271–1280. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.6.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dohmae K, Okabe M, Nishimune Y. Experimental transmission of hantavirus infection in laboratory rats. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:1589–1592. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.6.1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duchin J S, Koster F T, Peters C J, Simpson G L, Tempest B, Zaki S R, Ksiazek T G, Rollin P E, Nichol S T, Umland E T, Moolenaar R L, Reef S, Nolte K B, Gallaher M M, Butler J C, Breiman R F Hantavirus Study Group. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome: a clinical description of 17 patients with a newly recognized disease. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:949–955. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199404073301401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elliot L H, Ksiazek T G, Rollin P E, Spiropoulou C F, Morzunov S, Monroe M, Goldsmith C S, Humphrey C D, Zaki S, Krebs J W, Maupin G O, Gage K L, Childs J E, Nichol S T, Peters C J. Isolation of the causative agent of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;51:102–108. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.51.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gavrilovskaya, I., N. Apekina, A. Bernshtein, V. Demina, N. Okulova, Y. Myasnikov, and M. Chumakov. 1990. Pathogenesis of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome virus infection and mode of horizontal transmission of hantavirus in bank voles. Arch. Virol. (Suppl. 1):57–62.

- 9.Glass G E, Childs J E, Korch G W, LeDuc J W. Association of intraspecific wounding with hantaviral infection in wild rats (Rattus norvegicus) Epidemiol Infect. 1988;101:459–472. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800054418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldsmith C S, Elliott L H, Peters C J, Zaki S R. Ultrastructural characteristics of Sin Nombre virus, causative agent of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Arch Virol. 1995;140:2107–2122. doi: 10.1007/BF01323234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hjelle B, Anderson B, Torrez-Martinez N, Song W, Gannon W L, Yates T L. Prevalence and geographic variation of hantaviruses of new world harvest mice (Reithrodontomys): identification of a divergent genotype from a Costa Rican Reithrodontomys mexicanus. Virology. 1994;207:452–459. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hjelle B, Chavez-Giles F, Torrez-Martinez N, Yates T, Sarisky J, Webb J, Ascher M. Genetic identification of a novel hantavirus of the harvest mouse Reithrodontomys megalotis. J Virol. 1994;68:6751–6754. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.10.6751-6754.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hjelle B, Krolikowski J, Torrez-Martinez N, Chavez-Giles F, Vanner C, Laposanta E. Phylogenetically distinct hantavirus implicated in a case of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome in the northeastern United States. J Med Virol. 1995;46:21–27. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890460106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hjelle B, Lee S, Song W, Torrez-Martinez N, Song J W, Yanagihara R, Gavrilovskaya I, Mackow E. Molecular linkage of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome to the white-footed mouse, Peromyscus leucopus: genetic characterization of the M genome of New York virus. J Virol. 1995;69:8137–8141. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.12.8137-8141.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hutchinson K L, Rollin P E, Peters C J. Pathogenesis of a North American hantavirus, Black Creek Canal virus, in experimentally infected Sigmodon hispidus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59:58–65. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.59.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LeDuc J W, Childs J E, Glass G E. The hantaviruses, etiologic agents of hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome: a possible cause of hypertension and chronic renal disease in the United States. Annu Rev Public Health. 1992;13:79–98. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.13.050192.000455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee H W, French P W, Lee P W, Baek L J, Tsuchiya K, Foulke R S. Observations on natural and laboratory infection of rodents with the etiologic agent of Korean hemorrhagic fever. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1981;30:477–482. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1981.30.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee H W, Lee P W, Baek L J, Song C K, Seong I W. Intraspecific transmission of Hantaan virus, etiologic agent of Korean hemorrhagic fever, in the rodent Apodemus agrarius. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1981;30:1106–1112. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1981.30.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lyubsky S, Gavrilovskaya I, Luft B, Mackow E. Histopathology of Peromyscus leucopus naturally infected with pathogenic NY-1 hantaviruses: pathologic markers of HPS viral infection in mice. Lab Investig. 1996;74:627–633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mills J N, Ksiazek T G, Ellis B A, Rollin P E, Nichol S T, Yates T L, Gannon W L, Levy C E, Engelthaler D M, Davis T, Tanda D T, Frampton W, Nichols C R, Peters C J, Childs J E. Patterns of association with host and habitat: antibody reactive with Sin Nombre virus in small mammals in the biotic communities of the southwestern United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;56:273–284. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.56.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morzunov S, Feldmann H, Spiropoulou C F, Semenova V A, Rollin P E, Ksiazek T G, Peters C J, Nichol S T. A newly recognized virus associated with a fatal case of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome in Louisiana. J Virol. 1995;69:1980–1983. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1980-1983.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nerurkar V R, Song J W, Song K J, Nagle J W, Hjelle B, Jenison S, Yanagihara R. Genetic evidence for a hantavirus enzootic in deer mice (Peromyscus maniculatus) captured a decade before the recognition of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Virology. 1994;204:563–568. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nichol S T, Spiropoulou C F, Morzunov S, Rollin P E, Ksiazek T G, Feldmann H, Sanchez A, Childs J, Zaki S, Peters C J. Genetic identification of a hantavirus associated with an outbreak of acute respiratory illness. Science. 1993;262:914–917. doi: 10.1126/science.8235615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nolte K B, Feddersen R M, Foucar K, Zaki S, Koster F T, Madar D, Merlin T L, McFeeley P J, Umland E T, Zumwalt R E. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome in the United States: a pathological description of a disease caused by a new agent. Hum Pathol. 1995;26:110–120. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(95)90123-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Otteson E W, Riolo J, Rowe J E, Nichol S T, Ksiazek T G, Rollin P E, St. Jeor S C. Occurrence of hantavirus within the rodent population of northeastern California and Nevada. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;54:127–133. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.54.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ravkov E V, Rollin P E, Ksiazek T G, Peters C J, Nichol S T. Genetic and serologic analysis of Black Creek Canal virus and its association with human disease and Sigmodon hispidus infection. Virology. 1995;210:482–489. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rollin P E, Ksiazek T G, Elliott L H, Ravkov E V, Morzunov S, Livingstone W, Monroe M, Glass G, Ruo S, Khan A S, Childs J, Nichol S T, Peters C J. Isolation of Black Creek Canal virus, a new hantavirus from Sigmodon hispidus in Florida. J Med Virol. 1995;46:35–39. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890460108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rowe J E, St. Jeor S C, Riolo J, Otteson E W, Monroe M, Henderson W W, Ksiazek T G, Rollin P E, Nichol S T. Coexistence of several novel hantaviruses in rodents indigenous to North America. Virology. 1995;213:122–130. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song J W, Baek L J, Gajdusek D C, Yanagihara R, Gavrilovskaya I, Luft B J, Mackow E R, Hjelle B. Isolation of pathogenic hantavirus from white-footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopus) Lancet. 1994;344:1637. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90430-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spiropoulou C F, Morzunov S, Feldmann H, Sanchez A, Nichol S T. Genome structure and variability of a virus causing hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Virology. 1994;200:715–723. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanishita O, Takahashi Y, Okuno Y, Tamura M, Asada H, Dantas J R, Yamanouchi T, Domae K, Kurata T, Yamanishi K. Persistent infection of rats with hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome virus and their antibody responses. J Gen Virol. 1986;67:2819–2824. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-67-12-2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Torrez-Martinez N, Bharadwaj M, Goade D, Delury J, Moran P, Hicks B, Nix B, Davis J L, Hjelle B. Bayou virus-associated hantavirus pulmonary syndrome in eastern Texas: identification of the rice rat, Oryzomys palustris, as reservoir host. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998;4:105–111. doi: 10.3201/eid0401.980115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Torrez-Martinez N, Hjelle B. Enzootic of Bayou hantavirus in rice rats (Oryzomys palustris) in 1983. Lancet. 1995;346:780–781. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91541-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yanagihara R, Herbert L A, Gajdusek D C. Experimental infection with Puumala virus, the etiologic agent of nephropathia epidemica, in bank voles (Clethrionomys glareolus) J Virol. 1985;55:34–38. doi: 10.1128/jvi.55.1.34-38.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zaki S, Greer P W, Coffield L M, Goldsmith C S, Nolte K B, Foucar K, Feddersen R M, Zumwalt R E, Miller G L, Khan A S, Rollin P E, Ksiazek T G, Nichol S T, Mahy B W, Peters C J. Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome: pathogenesis of an emerging infectious disease. Am J Pathol. 1995;146:552–579. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]