Abstract

Background

The increase in COVID-19 cases in Indonesia has resulted in changes in the hospital workflow, including the staffing process and scheduling, especially in the isolation units. Nurse managers are working hard in the scheduling system to ensure high-quality care is provided with the best human resources.

Objective

This study aimed to explore the experiences of nurse managers in managing staff nurses’ work schedules during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

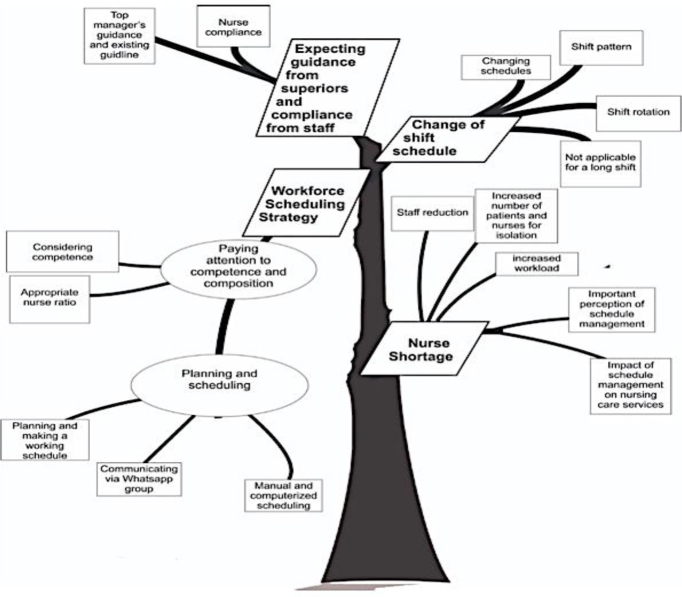

A qualitative descriptive design was used in this study. Eleven nurse managers from three COVID-19 referral hospitals were selected using purposive sampling. Data were collected using online semi-structured interviews. Thematic analysis was used for data analysis, and data were presented using a thematic tree. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist was used as a reporting guideline of the study.

Results

Four themes were developed: (i) Nurse shortage, (ii) Strategically looking for ways to fulfill the workforce, (iii) Change of shift schedule, and (iv) Expecting guidance from superiors and compliance from staff.

Conclusion

The lack of nurse staff is a problem during a pandemic. Thus, managing personnel effectively, mobilizing and rotating, and recruiting volunteers are strategies to fulfill the workforce during the pandemic. Using a sedentary shift pattern and sufficient holidays could prevent nurses from falling ill and increase compliance with scheduling. In addition, a staffing calculation formula is needed, and top nursing managers are suggested to provide guidance or direction to the head nurses to reduce confusion in managing the work schedule during the pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19, nurse managers, staffing, scheduling, workforce, Indonesia

Background

The increase in COVID-19 cases has caused changes in healthcare services, especially in hospitals. The increasing number of confirmed patients has resulted in changes in the treatment workflow in the isolation rooms (Gao et al., 2020), including the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) in direct contact with patients, which has become a challenge among nurses. Another change also occurs in the nurse scheduling because hospitals lack the personnel to handle the patients with COVID-19 (Al Thobaity & Alshammari, 2020). Therefore, adjustments must be made to the workforce composition in nursing shifts (Gao et al., 2020). However, healthcare services mostly require nurses to contact patients directly in carrying out nursing care (Huang et al., 2020).

Undoubtedly, nurses often experience a high workload, which leads them to fatigue, anxiety, and depression (Hu et al., 2020; Marzilli, 2021). This can be an obstacle in managing the work schedule. Asmaningrum et al. (2020) found that nurse managers made personnel arrangements during the pandemic, such as calculating the number, ratio of nurses, and composition. Furthermore, workflow changes were made, such as schedule changes, adding extra holidays, and rotating nurses in the team. In addition, our preliminary study at the Indonesian hospitals revealed that there were changes in nurses’ workflow during the pandemic. This was due to nurses being sick and an increase in patients with COVID-19, resulting in frequent changes to the service schedule. Also, changes in the official schedule cause inappropriate schedule patterns, increased workload, irregular working hours, fatigue, and human error. In addition, nurses’ workload during the pandemic became high, so many nurses were exposed to the virus. At the same time, nurse managers needed extra time to organize and change schedules.

A literature review was also carried out in a previous study on nurses’ experiences during pandemics and epidemics (Fernandez et al., 2020). It was found that nurses who worked during the pandemic were significantly affected by the unpreparedness of the nursing field in dealing with the current crisis. Indeed, the experience of nurse managers in undergoing this pandemic is significant in exploring how to improve service quality and avoid negative impacts for nurses. However, to our knowledge, a lack of studies discussed this issue in Indonesia; therefore, this study aimed to explore the experiences of nurse managers in managing staff nurses’ work schedules during the pandemic. This study will add the body of knowledge in nursing management and administration.

Methods

Study Design

A qualitative descriptive study was conducted to explore the experiences of nurse managers in managing schedules during the COVID-19 pandemic from January to July 2021. Qualitative descriptions are suitable for health research and bring researchers closer to the data about the participants’ experiences (Colorafi & Evans, 2016). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist (Tong et al., 2007) was used to report this study.

Participants

Eleven nurse managers from three COVID-19 referral hospitals and different rooms were participated to ensure sample representation and data saturation. The inclusion criteria of the participants were nurse managers, such as heads of the nursing section, heads of installation, or head nurses who were involved in managing the official nurse schedule. The exclusion criteria were team leaders, case managers, and infection prevention control nurses. Purposive sampling was used to select the participants for this study. Purposive sampling is the chosen strategy to provide the necessary information for research needs (Polit & Beck, 2018). Participant recruitment was done by distributing online flyers, WhatsApp captions, and Google Forms links. The researcher contacted those interested in participating and scheduled interviews according to the time agreed upon with the participants.

Data Collection

Data were taken from three COVID-19 referral hospitals in Indonesia. A semi-structured interview guideline was developed by the researchers and validated by senior researchers. The interview guide consisted of six open-ended questions to explore the experience of nurse managers in managing schedules during a pandemic, including (1) Tell us about your experience in managing work schedules during the COVID-19 pandemic, (2) Tell us about your understanding of managing nurse scheduling, (3) How do you perceive the management of the official schedule during the COVID-19 pandemic? (4) Why do we need to manage nurse schedules during a pandemic? (5) What challenges do you face while managing your official schedule during a pandemic? (6) Tell us about your expectations in managing schedules during the COVID-19 pandemic. The probing questions were carried out to encourage participants to provide more information, for example, how to schedule in a situation of being understaffed while patients continue to increase? Bracketing was done during the interview process, and this is important to reduce bias that could affect the research objective. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the interview was conducted online via the Zoom application for 40–60 minutes.

A digital video recorder in the Zoom was used, and field notes regarding non-verbal expressions during the interviews were also made. Prior to data collection, the essential aspects of the research, such as using a digital recorder, the purpose and benefits of the study, and how long the interview would take, were explained to the participants. Also, informed consent was obtained online from the participants via Google Forms before the interviews.

The interviewer was the first author holding a master’s degree in nursing education, an expert in the area of interest, and worked as a nurse manager but in a different setting. The interviewer was also trained in the qualitative approach. Bracketing was done during the data collection and analysis. During the interview, the third author, who holds a Ph.D education with qualitative research expertise, joined as a supervisor. The research team was independent and did not meet with the participants before the interviews to avoid the bias that might influence the participants’ responses or data analysis. During the interviews, the participants were not accompanied by anyone. In this study, repeated interviews were conducted only with one participant.

Data Analysis

For the effectiveness and efficiency of the study, the number of participants was adjusted to saturation at the time of the interviews, at approximately 15 people. Data saturation was agreed upon by the two researchers at around 11 interviews. The data were analyzed using thematic analysis, aiming to reach an understanding of the meaning patterns from the descriptions of the participants’ life experiences (Sundler et al., 2019). The researchers copied the interviews verbatim into text and then read them through several times. Furthermore, the search for meaning and identification of themes was carried out, and finally, the themes were organized into a meaningful whole (Sundler et al., 2019). The final themes were defined based on process descriptions and presented as a thematic tree. The thematic tree could represent and link all possible faults (final themes and subthemes) (Salleh et al., 2017).

Trustworthiness

Semi-structured per-informant interviews were conducted at different times, hospitals, and rooms to facilitate qualitative research. To increase the reliability of the study, peer reviews were done involving all the research team members at each step during the eight months of the study. In addition, the researchers used WhatsApp to conduct member checks with the participants. The results of a member check validated that the study results were in accordance with the experiences expressed by the participants.

Ethical Considerations

This study followed an ethical review process, and approval was obtained from the hospital ethics committee (Ethical approval number: 008/PEN/KEPK/RSUD CIAWI/III/2021) and the University of Indonesia ethics committee (Ethical approval number: SK-40/UN2.F12.DI.2.1/ETIK 2021). In addition, all participants completed the online study consent form. Data collection was carried out after the participants were informed about the research objectives. It was explained that their participation was voluntary and that they could choose not to complete the interviews without any consequences. Furthermore, the participants were informed of their anonymity and that the data provided would be kept confidential. The participants’ names were coded from P1-P11.

Results

Characteristics of the Participants

The age of the participants ranged from 29 to 48 years, and the years of service ranged from 7 to 22 years. Most of the participants were head nurses and holders of a bachelor of science in nursing. Diploma III refers to a three-year nursing program at the college/university level. The hospital names were not presented for confidentiality, replaced with RS P, RS S, and RS C (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participants’ demographic characteristics (n = 11)

| Characteristics | Description | Number |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 29–48 years | 11 |

| Gender | Male | 1 |

| Female | 10 | |

| Work Period | 6–10 | 3 |

| 11–15 | 5 | |

| 16–20 | 2 | |

| More than 20 years | 1 | |

| Hospital | RS P | 3 |

| RS S | 3 | |

| RS C | 5 | |

| Education | Bachelor of Science in Nursing | 7 |

| Diploma III in Nursing | 4 | |

| Work Unit | COVID Room | 5 |

| Non-COVID Room | 5 | |

| Inpatient Room | 1 | |

| Position | Head of Installation (Nurse) | 1 |

| Head Nurse | 10 |

Thematic Findings

The thematic tree was used to present the findings of this study, which provides various aspects of the nurse manager’s experience with scheduling during a pandemic (see Figure 1). Four themes were developed: (i) Nurse shortage, (ii) Strategically looking for ways to fulfill the workforce, (iii) Change of shift schedule, and (iv) Expecting guidance from superiors and compliance from staff.

Figure 1.

Overview of thematic tree analysis

Theme 1. Nurse Shortage

The reduction in staffing and increased number of patients are obstacles to managing the schedule during the pandemic. The decrease in personnel was due to the number of sick nurses who had to undergo self-isolation. When there is a reduction in staffing, scheduling becomes constrained. The constrained schedule causes nursing care to patients to not be optimal, complaints often occur, and nurses are exhausted. The following are some illustrative excerpts from the participants:

”Since August, we have experienced a decrease in personnel due to self-isolation for three months, so we can say it is difficult to make a schedule because of lack of nurses.” (Head of the installation, P2)

“The decrease is due to the increasing number of patients who are also self-isolating. If there is one person in the hospital, it is very influential. It also affects their friends.” (Head nurse, P11)

“Nursing care is not maximal; that is the first. The second is that there are many patient complaints, ma’am. Many complain about slow service. Then, many complain that they are called late when they come, ma’am. Then the third thing, of course, fatigue…” (Head of the installation, P2)

Managing schedules is one of the nurse managers’ functions related to the staff. Participants realized that managing schedules was the manager’s job and were essential because it affected the quality of care. They said:

“…So the function is indeed to regulate, with this schedule, it is okay to arrange your friends per shift so that it is as expected.” (Head nurse, P5)

“This is very important, ma’am, because if we make a mistake in managing the schedule of the service, it will automatically affect the quality of care.” (Head nurse, P6)

Theme 2. Workforce Scheduling Strategy

The workforce scheduling strategy is challenging. With nurse shortage, the head nurses asked for help from another room and proposed the addition of new personnel, such as adding volunteers to the heads of the installation or nursing managers. The heads of the installation then mobilized the staff by asking for help from a non-COVID-19 room. Also, the rotation of nurses was carried out by the nursing managers in coordination with the head nurses in the units.

“…If there is a shortage of staff, the nurse from the internal medicine room (IMR) or intensive care unit (ICU) will help us. So, every shift, we have assistance from the ICU or the IMR.” (Head nurse, P7)

“I checked the schedule first, ma’am, and looked at the number of patients. If the patients were still at a high level, I mobilized the nurses.” (Head of the installation, P2)

“We had an incident like that, ma’am, so we had a chance to recruit.” (Head nurse, P6)

Subtheme 2.1 Paying attention to competence and composition

In addition to clinical nurse level and competence, staff capabilities need to be considered in scheduling. The head nurses combined the composition of nurses in shifts, such as having senior nurses and volunteers in each shift, and made every effort to have at least a charge nurse and associate nurses.

“Besides the level of Clinical Nurse, I also consider competence…” (Head nurse, P1)

“So, we attempt to have one or two senior volunteers for each shift.” (Head nurse, P5)

“Well, for this scheduling, it is the same. The strategy is how to keep the appropriate composition. There is a person in charge and the associate nurses. We share the Primary Nurse the same way.” (Head nurse, P6)

Subtheme 2.2: Planning and scheduling

Schedule planning was done regularly, both manually and computerized. The schedule was analyzed by counting the number of nurses in shifts, working hours, and working days. The communication regarding the update of the schedule was carried out through WhatsApp, in which the head nurses created a WhatsApp group to inform about scheduling changes.

“We make a schedule a week before the 21st of each month. We plan an official schedule.” (Head nurse, P6)

“The analysis is for the working hours and working days. For example, how many people are there in the morning shift, how many in the afternoon, how many at night, and some on leave or not.” (Head nurse, P11)

“We have a WhatsApp group, for one ward where all the nurses in my room are included in the group, so everyone knows that if there is a change, they will be notified, even though it is scheduled.” (Head nurse, P9)

Theme 3. Change of Shift Schedule

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the nurse shift pattern at the hospital was eight hours in the morning, afternoon, and night. Four participants stated that they did not apply overtime or long shifts during the pandemic and applied for middle shifts. In addition, participants indicated that they used fixed-shift rotations for five working days, but other participants stated that they used shift rotations of six or even eight working days. In certain circumstances where there is a shortage of personnel, nurse managers make changes in the scheduling.

“The schedule for our unit remains the same. It is made up of shifts, morning, afternoon, and evening shifts” (Head nurse, P6)

“…So, to anticipate if someone gets sick in the morning, there is a middle service which backs up the morning service…” (Head nurse, P7)

“So, in the morning and evening, after taking care of them, they are off …they get a day off.” (Head of the installation, P2)

“The schedule pattern after this pandemic is that we use shifts, ma’am, but not long shifts. Only morning and evening shifts.” (Head of the installation, P2)

Theme 4. Expecting Guidance from Superiors and Compliance from Staff

The participants stated that policies were needed during the pandemic, especially in the isolation rooms. Schedule management requires guidance and examples. The head nurses wanted the nurses to comply with the service schedule. Using a sedentary shift pattern with three working days and two days off gave nurses rest time and reduced jealousy. According to the participants, using the fixed shift pattern and vacation time could reduce the incidence of nurses being sick.

“Maybe in the isolation unit there needs to be a new policy. How about special scheduling.” (Head nurse, P6)

“So, we do not just deliver the official schedule like this, without being guided by examples. I hope that when someone submits the schedule, and we are guided, there is guidance…” (Head of the installation, P2)

“For this scheduling, I really hope that my friends (staff) will be obedient so that they are giving the service according to what I made” (Head nurse, P5)

Discussion

This study aimed to explore the experiences of nurse managers in managing staff nurses’ work schedules during the COVID-19 pandemic. Four themes were developed and explained in the following discussion.

Theme 1. Nurse Shortage

This theme indicated the challenge of nurse managers in managing the nurse workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, an effective and efficient schedule should be made, with an adequate number of nurses in each shift (Rashwan, 2017). The lack of nurse staff in this study occurred because many nurses got sick and needed to self-isolate. This study supports the review conducted by Al Thobaity and Alshammari (2020) found that staff shortages are a problem that nurses face when dealing with COVID-19. Data from the International Council of Nurses (2021) also show that in several countries, nurses are the health workers who are most exposed to COVID-19. Therefore, nurse resilience needs to be improved by ensuring physical and psychological safety and health to maintain the number of nurses (International Council of Nurses, 2021; Zahednezhad et al., 2021). Hospitals can play a role in preventing nurses from falling ill, especially by providing a passive shift pattern with three working days and two days off to provide rest time for nurses.

Additionally, in this study, the nurse managers understand the importance of schedule management and its impact on care services. This understanding could be considered one of the nurse managers’ competence to ensure high-quality care, although with a lack of personnel. However, structural components of staff tend to affect the care process and quality of service (Voyce et al., 2015). Thus, the nurse managers’ competence in scheduling is highly needed.

Theme 2. Workforce Scheduling Strategy

According to the study findings, the first strategy used by the head nurses to overcome the shortage was to make the staff effective, based on the nurses’ competence and composition. If it could not be anticipated, the head nurses asked for help from other rooms and proposed the addition of new personnel, such as adding volunteers to the heads of the installation or the nursing managers. Nurse managers make an effort to recruit nurses, both volunteers and non-volunteers, to compensate for staff shortages during a pandemic (Poortaghi et al., 2021). The strategy carried out by the nurse managers was adjusted to the span of control. It is noteworthy that the head nurses could only make staff effective, while the head of the installation mobilized nurses between rooms by asking for help from non-COVID-19 rooms. At the same time, the rotation of nurses between rooms or units was carried out by the nursing managers in coordination with the head nurses in the units. The head nurses coordinated the implementation of the directive function in consultation with other departments or management. However, nurse managers need to understand the organizational structure and recognize who will make decisions (Marquis & Huston, 2017) to get feedback and good results. However, managing schedules during a pandemic is not easy. Mobilizing nurses and new volunteers between rooms was a challenge for nurse managers to maintain a skill mix during a pandemic. However, a combination of senior and junior nurses in shifts could foster understanding and reduce work stress (Gao et al., 2020; Kuppuswamy & Sharma, 2020), as well as improve the quality of care, reduce fatigue, and increase job satisfaction (Kernick, 2018).

Another effort needed to overcome the shortage of personnel while still paying attention to patient safety is the strategy to overcome the labor shortage from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which hospitals need to understand and meet the minimum number of staff needed to create a safe work environment during a pandemic. Hospitals can work with other health services to recruit additional nurses, adjust service schedules, rotate nurses to service sites, and assist nursing students and volunteers. If the shortage of personnel is not met, the hospital may allow nurses who are suspected or confirmed to be infected with SARS-CoV-2 but are healthy enough and willing to work, but according to the priority of tasks recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Cdc) (2021).

Besides, another scheduling strategy developed in this study was planning and analyzing the schedule during the pandemic, which could be done by counting the number of nurses per shift, working hours, and working days. With schedule planning, the number of staff in the units will be well controlled because it was done by counting the number of nurses according to the number of patients per shift so that nurses will not be tired. This is in line with Gao et al. (2020) stated that, by scheduling, the head nurses could dynamically adjust the nurses’ working hours to ensure patient safety and service quality. However, schedules are drawn up manually and using computers, so a flexible formula is needed for scheduling nurses shifts under conditions of an insufficient number of nurses in the form of software that is helpful in scheduling during a pandemic (Seccia, 2020).

In addition to the second strategy, the nurse managers’ briefing function was implemented by communicating official schedule updates through social media platforms, such as WhatsApp. The head nurse created a WhatsApp group to inform of the scheduling changes. This is in line with a review conducted by Farsi (2021) stated that social media platforms, such as WhatsApp, are currently used to obtain and disseminate information quickly, cheaply, and more easily accessible, including in the field of nursing.

Theme 3. Change of Shift Schedule

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the nurse shift pattern at the hospital was eight hours in the morning, afternoon, and evening. This is in line with Gao et al. (2020) that the shift pattern during the pandemic is a shift of four or eight hours in isolation rooms and shifts of eight or 12 hours in semi-contaminated areas with a pattern of the morning, afternoon, and evening shifts (Gao et al., 2020). However, not applying overtime or long shifts and implementing middle shifts were some of the nurse managers’ efforts to avoid stress and fatigue among nurses during the pandemic (Suter et al., 2020). Meanwhile, permanent shift rotation for five working days and shift rotation for six to eight working days were carried out to overcome fatigue and adjust to the adequacy of the existing workforce. This is not in line with the statement by Kuppuswamy and Sharma (2020) that nurses are placed in the COVID-19 isolation room for 14 days on duty and then quarantined for 14 days where the hospital provides accommodation. There is a difference in shift rotation between the results of this study and the other studies, showing that policies made regarding the length of the rotation of nurses in isolation rooms should be adjusted to the ability of a country or region regarding the adequacy of existing personnel.

During the pandemic, nurse managers frequently changed schedules. A previous study stated that changes in the schedule were carried out flexibly to meet the workforce’s composition and reduce the occurrence of stress and fatigue (Asmaningrum et al., 2020). The schedule was made in the form of a team with a fixed composition of nurses for every shift. Therefore, nurses had mental readiness in the team. In addition, monitoring the schedule for each shift was carried out to overcome the shortage of personnel. Dynamically adjusting nurses’ working hours and increasing the number of nurses on duty can ensure patient safety and maintain service quality. In other words, flexible shifts can further ensure that nurses have time off and reduce their workload and stress, especially during middle and night shifts (Gao et al., 2020).

Theme 4. Expecting Guidance from Superiors and Compliance from Staff

No doubt, a team approach is needed between the nursing manager and the head nurses to build trust and support (Marquis & Huston, 2017) to avoid confusion in the schedule management. Schedule management requires guidance, exemplified to make it easier to make a schedule. According to the findings of this study, the head nurses expected their top nurse managers could provide guidance and direction in making official schedules and improving communication to find out the difficulties faced in increasing nurses’ satisfaction in scheduling implementation. In other words, the competence of top nurse managers is also needed in carrying out resource management and strategic management, such as making contingency plans for both internal and external disaster management and planning and implementing emergencies (Morse & Warshawsky, 2021).

In addition, policies regarding schedule management are also needed, especially in isolation rooms. Policymaking related to workforce management, including scheduling, needs to be carried out to implement the nursing manager’s planning function (National Health Service (Nhs) England, 2019). Hospitals can also provide training related to the competencies that nurse managers must possess. At the same time, professional organizations can add continuing education programs related to advanced disaster nursing to nurses at Clinical Nurse levels 1 and 2 to be ready to face crises. The career ladder policy in Indonesia is outlined within the Regulation of Health Ministry No. 40 the year 2014 on the career ladder. The nursing career ladder starts from clinical nurse level I up to V (Indonesian Ministry of Health, 2014).

Besides, the nurse staff compliance regarding the schedules is also needed. It is understandable that nurses’ shift cycles during the pandemic tend to be irregular, and this causes nurses to have no guarantee that they can go on vacation on weekends, resulting in nurses’ non-compliance with scheduling (Lee & Jeong, 2021). Hospitals can use a sedentary shift pattern with three working days and two days off to give nurses time to rest, reduce jealousy between nurses, and provide definite days off to reduce the incidence of nurses falling ill. However, the nurse manager’s control function must be implemented by evaluating the staff’s implementation of the service schedule.

Implications of the Study

The findings of this study show that adequate human resources are critical in managing schedules during the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, nurse managers should strategically carry out interventions to overcome staff shortages by changing schedules according to pandemic conditions, recruiting volunteers, and increasing communication regarding schedule management through social media while still paying attention to the competence of nurses on duty. In addition, guidance from top nurse managers regarding schedule management and policy is needed among head nurses during the pandemic.

The study findings also provide encouragement to health organizations about the need for adequate hospital resources, flexible work schedules, and adequate rest periods during the pandemic in order to reduce the incidence of sick nurses. Also, the findings encourage national and international nurse managers about the efforts to manage work schedules in critical situations and that working hours and work schedules in each country will differ according to the adequacy of available resources.

In addition, the results of this study reveal the experience of nurse managers in managing schedules during the COVID-19 pandemic and that nurse managers feel confused in managing schedules. To obtain more information about personnel management strategies, further research is needed in various more diverse institutions.

Conclusion

It is concluded that the shortage of human resources is a major problem for nurse managers during the pandemic. Effective managing personnel, mobilizing, rotating, and recruiting volunteers are the strategies that can be used by the hospitals. The use of a sedentary shift pattern and sufficient holidays can reduce the incidence of nurses being sick and increase nurses’ compliance with scheduling. Besides, a staffing calculation formula is needed by considering the unpredictable shortage of staffing. The nursing manager can guide the head nurses to reduce confusion in schedule management.

Acknowledgment

The researchers express their gratitude to the hospitals where the study was conducted and the participants in this study.

Declaration of Conflicting Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest in this study.

Funding

None.

Authors’ Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception of this study, drafting and revising the work critically, approved for the final version, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Authors’ Biographies

Ns. Kartika Mawar Sari Sugianto, S.Kep is a Master Student in Nursing Leadership and Management Program, Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Indonesia, Indonesia.

Prof. Dr. Rr. Tutik Sri Hariyati, SKp, MARS is a Professor at the Department of Basic Science and Fundamental Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Indonesia, Indonesia.

Hening Pujasari, S.Kp., M.Biomed., MANP., Ph.D is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Basic Science and Fundamental of Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Indonesia, Indonesia.

Dr. Enie Novieastari, S.Kp., MSN is an Associate Professor at the Department of Basic Science and Fundamental Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Indonesia, Indonesia.

Dr. Hanny Handiyani, S.Kp., M.Kep is a Head of Master's Degree Program of Nursing Science, Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Indonesia, Indonesia.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

References

- Al Thobaity, A., & Alshammari, F. (2020). Nurses on the frontline against the COVID-19 pandemic: An integrative review. Dubai Medical Journal, 3(3), 87-92. 10.1159/000509361 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asmaningrum, N., Nur, K. R. M., Purwandari, R., & Ardiana, A. (2020). Nursing work arrangement in health care settings during the pandemic of Covid-19: Nurse managers’ perspectives. NurseLine Journal, 5(2), 231-240. 10.19184/nlj.v5i2.20544 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . (2021). Strategies to mitigate healthcare personnel staffing shortages. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/mitigating-staff-shortages.html

- Colorafi, K. J., & Evans, B. (2016). Qualitative descriptive methods in health science research. HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 9(4), 16-25. 10.1177/1937586715614171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farsi, D. (2021). Social media and health care, Part I: Literature review of social media use by health care providers. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(4), e23205. 10.2196/23205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, R., Lord, H., Halcomb, E., Moxham, L., Middleton, R., Alananzeh, I., & Ellwood, L. (2020). Implications for COVID-19: A systematic review of nurses' experiences of working in acute care hospital settings during a respiratory pandemic. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 111, 103637. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X., Jiang, L., Hu, Y., Li, L., & Hou, L. (2020). Nurses’ experiences regarding shift patterns in isolation wards during the COVID‐19 pandemic in China: A qualitative study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(21-22), 4270-4280. 10.1111/jocn.15464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, D., Kong, Y., Li, W., Han, Q., Zhang, X., Zhu, L. X., . . . Yang, J. (2020). Frontline nurses’ burnout, anxiety, depression, and fear statuses and their associated factors during the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China: A large-scale cross-sectional study. EClinicalMedicine, 24, 100424. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L., Lin, G., Tang, L., Yu, L., & Zhou, Z. (2020). Special attention to nurses’ protection during the COVID-19 epidemic. Critical Care, 24, 120. 10.1186/s13054-020-2841-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indonesian Ministry of Health . (2014). Regulation No 40 Year 2014 on Career Ladder. Jakarta: Ministry of Health, Republic of Indonesia; Retrieved from https://peraturan.bpk.go.id/Home/Details/119077/permenkes-no-40-tahun-2014. [Google Scholar]

- International Council of Nurses . (2021). ICN COVID-19 update. Retrieved from https://www.icn.ch

- Kernick, D. (2018). Skill-mix change and the general practice workforce challenge. The British Journal of General Practice, 68(669), 176. 10.3399/bjgp18X695429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuppuswamy, R., & Sharma, S. K. (2020). Efficient utilization of nursing manpower during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pondicherry Journal of Nursing, 13(2), 39-42. 10.5005/jp-journals-10084-12145 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J., & Jeong, I. S. (2021). Compliance with recommendations on work schedule for shift nurses in South Korea. Safety and Health at Work, 12(2), 255-260. 10.1016/j.shaw.2021.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquis, B. L., & Huston, C. J. (2017). Leadership roles and management functions in nursing: Theory and application (9th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Marzilli, C. (2021). A year later: Life after the Year of the Nurse. Belitung Nursing Journal, 7(2), 59-61. 10.33546/bnj.1509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse, V., & Warshawsky, N. E. (2021). Nurse leader competencies: Today and tomorrow. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 45(1), 65-70. 10.1097/naq.0000000000000453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Health Service (NHS) England . (2019). Nursing and midwifery e-rostering: A good practice guide. Retrieved from https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/20190903_UPDATED_Nursing_Midwifery_E-Rostering_Guidance_September_2019.pdf

- Polit, D., & Beck, C. (2018). Essentials of nursing research: Appraising evidence for nursing practice (9th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Poortaghi, S., Shahmari, M., & Ghobadi, A. (2021). Exploring nursing managers’ perceptions of nursing workforce management during the outbreak of COVID-19: A content analysis study. BMC Nursing, 20(1), 1-10. 10.1186/s12912-021-00546-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashwan, W. (2017). An integrated framework for staffing and shift scheduling in hospitals. (PhD Thesis), Technological University Dublin, Ireland. Retrieved from https://arrow.tudublin.ie/busdoc/25/ [Google Scholar]

- Salleh, I. S., Ali, N. S. M., Yusof, K. M., & Jamaluddin, H. (2017). Analysing qualitative data systematically using thematic analysis for deodoriser troubleshooting in palm oil refining. Chemical Engineering Transactions, 56, 1315-1320. 10.3303/CET1756220 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seccia, R. (2020). The nurse rostering problem in COVID-19 emergency scenario. Retrieved from http://www.optimization-online.org/DB_FILE/2020/03/7712.pdf

- Sundler, A. J., Lindberg, E., Nilsson, C., & Palmér, L. (2019). Qualitative thematic analysis based on descriptive phenomenology. Nursing Open, 6(3), 733-739. 10.1002/nop2.275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suter, J., Kowalski, T., Anaya-Montes, M., Chalkley, M., Jacobs, R., & Rodriguez-Santana, I. (2020). The impact of moving to a 12h shift pattern on employee wellbeing: A qualitative study in an acute mental health setting. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 112, 103699. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349-357. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voyce, J., Gouveia, M. J. B., Medinas, M. A., Santos, A. S., & Ferreira, R. F. (2015). A Donabedian model of the quality of nursing care from nurses’ perspectives in a Portuguese hospital: A pilot study. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 23(3), 474-484. 10.1891/1061-3749.23.3.474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahednezhad, H., Zareiyan, A., & Jame, S. Z. B. (2021). Relationship between quality of work-life, resilience and burnout among nursing professionals during COVID-19 pandemic in Iran: A cross-sectional study. Belitung Nursing Journal, 7(6), 508-515. 10.33546/bnj.1702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).