Abstract

Background

Adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART) can be challenging since it needs to be continued for a lifetime. At their age, adolescents start to be responsible for their life, and this continued therapy might be a challenge for them.

Objective

This study explored the experiences of adherence to ART in adolescents living with HIV in Jakarta, Indonesia.

Methods

A qualitative study with an Appreciative Inquiry (AI) approach was employed to explore challenges adolescents face in ART adherence which focused more on positive aspects of the experience. In-depth interviews were conducted with ten adolescents who were selected purposively based on criteria including those aged 13-19 years, having been diagnosed with HIV infection and receiving ART for more than a year, and never having discontinued ART. All participants were registered in the outpatient clinic in one top referral hospital in Jakarta. The data were analyzed using thematic analysis.

Results

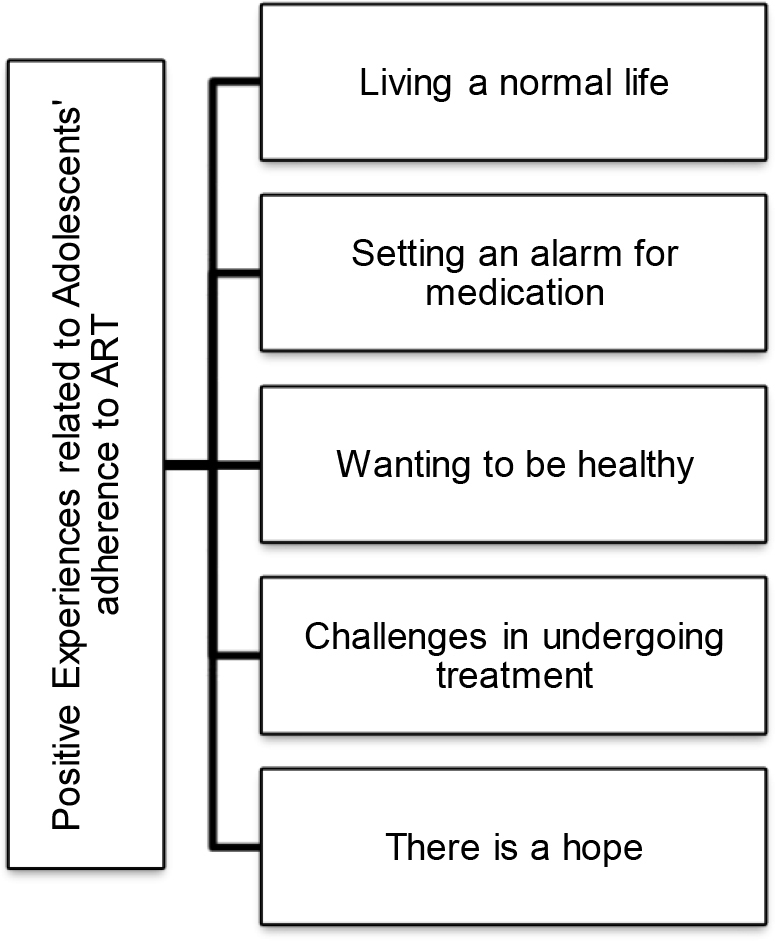

Five themes were identified from the data: living a normal life, wanting to be healthy, taking medication on time, challenges in undergoing treatment, and there is hope.

Conclusion

Adolescents with HIV want to live as normal and healthy as possible, like other adolescents. Even though adolescents face several challenges to comply with ART, they try to take the medication as prescribed. The findings of this study serve as input for nurses to maintain compliance with ARVs in adolescents who have HIV.

Keywords: adherence, adolescents, antiretroviral therapy, appreciative inquiry, HIV infection, Indonesia, nursing

Background

Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNIAIDS) data in 2019 shows that the number of people who lived with HIV infection across the world was 37.9 million in 2018; of these, 1.7 million (4.48%) were children aged less than 15 years (UNAIDS, 2019). The Indonesian Ministry of Health reported the following percentages of HIV infection cases from April to June 2019 according to specific age groups: 1.9% for children less than four years old, 0.9% for children aged 5–14 years, and 2.7% for adolescents aged 15–19 years old (Direktorat Jendral P2P, 2019). Adolescents in Indonesia are at risk of being infected with HIV due to their developmental characteristics. Adolescents are psychologically immature, extremely curious, and can easily be influenced by their surroundings, particularly related to sexual risk behavior. Often, adolescents have a sexual relationship or other similar experiences only out of curiosity (Media, 2016), which may lead to HIV infection.

The only treatment for HIV infection is antiretroviral therapy (ART) (Indonesian Ministry of Health, 2019). ART is recommended for patients with HIV infection by disturbing the virus replication and reducing the virus levels, thereby improving immunity and reducing the occurrence of opportunistic infections and the mortality rate (Godfrey et al., 2017; Karyadi, 2017; Mahathir et al., 2021). Consequently, adolescents’ quality of life following ART will be improved.

Adherence to HIV treatment is challenging, particularly for adolescents. According to the registrar book from a top referral hospital for infectious disease in Indonesia, 31 adolescents aged 10-19 took ART in March 2018. However, only 51.61% of them complied with the ART, while others were categorized as ‘loss to follow up’ patients. In the majority, adolescent compliance is less than other children’s age. This is because the disease is caused by vertical transmission (92%) in adolescents aged less than 13 years old (Indonesian Ministry of Health, 2019), and because of that, most of them are not aware of their HIV-positive status (Hornschuh et al., 2017). Denison et al. (2015) stated that if children are not aware of their HIV-positive status until they become teenagers, they may not adhere to ART because they would not know the consequence of nonadherence.

As part of health workers, pediatric nurses must act as a counselor and a facilitator in order to assist adolescents in complying with ARV therapy. Accordingly, their lives become optimal and adapt to their disease conditions requiring children to take ARV for life. As a counselor, a pediatric nurse is responsible for counseling pre-ART, facilitating decisions on who will be the drug assistance for each adolescent, monitoring side effects, regular health teaching on health problems related to ART, and evaluating the effectiveness of ART. Meanwhile, as a facilitator, a pediatric nurse is responsible for facilitating patient access to ART and its availability during certain times to ensure patients’ compliance with ART.

Nonadherence to therapy has several negative impacts on patients and increases the healthcare burden. Moreover, adolescents have needs and characteristics very distinct, and they will get different information. The current research exploring adherence ARVs in adolescents with HIV experiences is still low. Therefore, strong evidence is needed to explore and identify problems regarding the experience of adolescents with HIV in undergoing ARV therapy (Chenneville et al., 2017). Nurses as healthcare professionals can apply the self-efficacy theory to identify factors that can boost confidence in adolescents with HIV/AIDS regarding their ability to adhere to ART. In the present qualitative study, the appreciative inquiry (AI) approach was used to explore and identify problems, strengths, and positive aspects to discover new ways to improve adherence to ART in adolescents with HIV infection.

Methods

Study Design

This was a qualitative study using the Appreciative Inquiry (AI) approach. In this study, adolescents were interviewed about their experience in adhering to ART. AI aims to explore the positive experiences of participants in order to develop a change in an individual or situation. AI consisted of four phases: discovery, dream, design, and destiny. The researchers described results from the first and second phases in this paper.

Participants

The participants in this study were adolescents with HIV/AIDS who underwent ARV therapy at a top referral hospital for infectious diseases in Indonesia. The inclusion criteria were as follows: aged 13–19 years, not married, been diagnosed with HIV infection for more than one year, never stopped the medication, aware of their HIV positive status, able to use Bahasa Indonesia, and cognitive-abled. Exclusion criteria were the HIV adolescent that experienced health deterioration during data collection. Participants were recruited using purposive sampling. Nurses in the outpatient clinic assisted in recruiting the participants. The nurses identified adolescents with HIV/AIDS admitted to the outpatient clinic, and then the researchers met with the adolescents to obtain their consent to be involved in the study. Ten adolescents agreed to be involved in this study. During the data collection period, no participants withdrew from the study.

Data Collection

The data were collected from May to June 2020 using offline and online in-depth interviews, recorded using a recorder. Data collection was held in the counseling room, cafe, or participant’s house. When the interview was conducted, no one else was listening. The interview guidelines (Table 1) and observation sheet were the additional instrument used during the interview process and had been tested beforehand. Interview and observational data were documented in the field note. The interview process lasted 45 – 60 minutes. No repeat interview was performed. Interviews were conducted until no new information was obtained from the participants. The results of the interviews that have become transcripts were stored in a flash disk and printed for further clarification to the participants.

Table 1.

Interview guidelines

| No | Questions |

|---|---|

| 1 |

Discovery Phase Could you describe how did you live with HIV? Could you describe how did you get along with ARV treatment? |

| 2 |

Dream Phase What do you dream about living with HIV? What do you dream about undergoing ARV treatment? |

Data Analysis

A thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2012) was applied systematically to identify, organize, and facilitate ideas into the meaning in one set of data. This method was chosen to explore the different perspectives among the participants, highlight the similarities and differences and produce unexpected insights. In general, the data analysis process included data recognition, compiling the code, searching for themes, reviewing other potential themes that will appear, defining and naming themes, and writing reports (Nowell et al., 2017). Data analysis was focused on the adolescents’ experiences during ARV therapy.

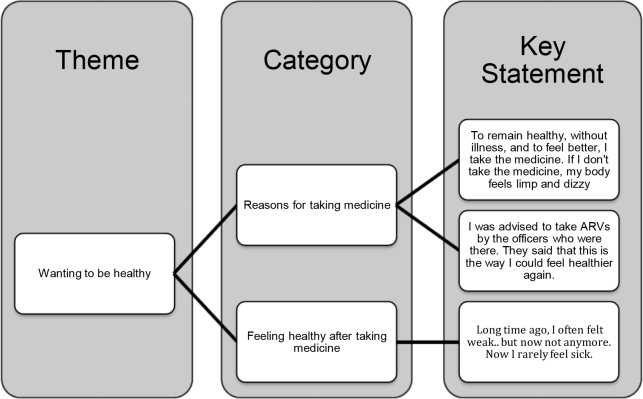

The first analysis process was analyzing the transcript, which was read three to four times, and the experience of each participant was rewritten in a detailed manner. Meaning units were identified from the transcripts and were condensed into key statements. Key statements were sorted into categories which were later formulated into themes (an example of this process is provided in Figure 1). Afterward, the themes of each transcript were compared, and the themes that were relevant to the research question were highlighted. Then the researcher identified the linkages between the themes. The researchers confirmed that the themes possess enough data evidence. After describing and identifying the themes, the researchers validated and confirmed the themes to the participants.

Figure 1.

Example of theme formulation

Trustworthiness/Rigor

The rigor of this study was achieved through several strategies: First, a thick description of the study process, including data analysis, related to transferability. Member checking, the process when the researchers asked for confirmation of the themes from the participants, was also conducted to achieve credibility and confirmability. Finally, to achieve instrument stability, the researchers involved the supervisor as an external reviewer and used literature reviews of the related references.

Ethical Consideration

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Indonesia (reference: SK-110/UN2.F12.D1.2.1/ETIK.2020). Informed consent was given to adolescents over 18 years old, while for adolescents aged 18 years old or below, the informed consent was given to their mothers.

Results

Adolescents aged 13–19 years were involved in this study. Out of these, six participants were senior high school graduates. The HIV infection in eight participants was caused by vertical transmission. Four participants lived with their parents at the time of data collection, while the remaining lived with only their father, only their mother, or other family members. Most participants did not join the peer support group. Nine participants were still receiving first-line therapy, i.e., neviral and duviral, while one participant was receiving second-line therapy, i.e., alluvia, tenofovir, and lamivudine. The names used in the study are pseudonyms, which are only known to the participants and authors. From this study, five main themes (Figure 2) were obtained closely related to the adolescents’ condition when adhering to ART.

Figure 2.

Themes identified related to adolescents who take ART

Theme 1: Living a normal life

Adolescents in this study reported taking ART every day to live like adolescents without HIV infection. Two of the adolescents said:

“Yes, helping my mom, eating, sleeping, doing common activities, and surely playing sports… The point is, I have to maintain my immune system so that it is continuously functioning.” (Robert)

“What I do, staying with my younger sister, playing with my mobile phone, eating, sleeping, watching TV, doing homework, helping my parents.” (Juliet)

Robert and Juliet defined living a normal life as doing everyday activities such as eating, sleeping, and playing. The purpose of doing such daily activities was to keep functioning like other normal adolescents, even though not quite as normal. This was mentioned by Isabel:

“… being back to normal life, even though not really like them, just go on, …, sometimes I play with my friend at home, at work, mingle with them, …” (Isabel)

Furthermore, Richard gave another definition of normal:

“When going home after Asr prayer, I do not directly go home. I play with my schoolmates for a while and play on a mobile phone…” (Richard)

Richard describes his normal life as spending his time after school with his schoolmates. Those Robert and Richard’s definitions of normal life matched with their development characteristics as adolescents, where peer group relationship is important.

Theme 2: Setting an alarm for medication

Participants mentioned methods used as reminders for taking ART, including phone alarms or alarm watches.

“Oh yes, I have an alarm before 10 o’clock… I set the alarm for 9.55 am. So, before taking medicine, at 9.55 am, the alarm starts beeping, which means that in 5 more minutes, I have to take medicine, and I prepare accordingly. When the alarm beeps again for the second time at 10.00 am, I take my medicine. So, I set two alarms” (Robert)

“I always look at the clock in the living room. I stay at home, not playing with others until I take medicine. When it’s already 6 pm, then I take my medicine. That’s it. I take my medicine at 6.” (Jesica)

Robert used two alarms to remind him to take ART on time. This strategy was successful in keeping him adhered to taking ARV drugs. In comparison, Jesica used her home clock to remind her when was the time to take medicine. Other adolescents employed people who reminded them to take ART, such as family, friends, and healthcare professionals.

“My mother keeps the medicine. She asks me to take medicine regularly. No skipping.” (Eric)

“… and then from the health team, they always support me, even they always remind me to take medicine, they told me when I have to go to the hospital again” (Jesica)

Theme 3: Wanting to be healthy

Some reasons that motivated the participants to adhere to ART were their wish to remain healthy after taking the medicines and their belief that they would always be healthy if they adhered to the therapy.

“To remain healthy, without illness, and even feel better, I take medicine rather than not taking it. If (I) don’t take medicine, my body feels limp and dizzy” (Isabel)

“Long time ago I often felt weak, but now not anymore. Now I rarely feel sick” (Mark)

Isabel clearly mentioned that her purpose in taking medicine regularly was to remain healthy. Likewise, Juliet and Jesica said the same reason:

“My motivation is to be strong, to be healthy… just to be healthy” (Juliet)

“To be healthy, so I can grow up, in a healthy condition all the time” (Jesica)

Juliet and Jesica clearly expressed their motivation relating to ARV adherence, which was to keep them in a healthy condition; consequently, they can grow to adulthood period.

Theme 4: Challenges in undergoing treatment

Participants felt many challenges must be faced in undergoing ARV treatment. The challenges include feeling the side effects of drugs, forgetting, queuing when taking medication, having to regularly take medication at the same time, being bored of taking medication, and large drug sizes. The participants expressed this in the following statements:

“I felt dizzy at first, but as time went on, I got used to just feeling dizzy, like people who fly, yes they fly” (David)

“My hands often feel numb, when my feet get wet, everything gets wet to the point of sweating like it’s hot, but when the water hits the hands, the feet don’t get wet” (Richard)

“The first time I was nauseous, it was hard to swallow, at first I was often sick, in the past, I used to feel bad every time I took medicine, now I don’t feel bad anymore” (Mark)

Theme 5: There is a hope

This theme describes participants’ hopes for their future life. When they talked about future life, this meant the ART availability and their plan to have a family of their own.

“It’s good that the medicine is there; hopefully, the medicine doesn’t run out, it’s always available and free. My hope is to get well soon, stay healthy, don’t get sick easily.” (Mark)

“Hopefully, if I get married later, my child won’t be affected.” (Kyle)

“The point is that I have to be obedient to be able to live my future to have a wife to achieve my goals.” (Robert)

The hope is also related to the expectation of being free from stigma as a person with HIV, namely that no one is shunned or demeaned. The participants expressed the following statements:

“Don’t look down on people who have HIV disease; it’s not necessarily that HIV is contagious by holding hands” (Isabel)

“HIV people don’t stay away, don’t stay away, stay friends” (Mark)

Discussion

Most of these adolescents understood the importance of taking care of their health by adhering to the treatment. The findings of this study showed that the acceptance of their current condition is important in adolescents with HIV infection as a positive coping mechanism. This study is coherent with the previous research that identifies the correlation between self-efficacy and HIV medication adherence. The patients’ beliefs in their ability to have self-control in relation to HIV medication are good for them (Aregbesola & Adeoye, 2018). This belief in self-control on HIV treatment impacts the psychological state. This finding is similar to that of a study conducted by Rzeszutek et al. (2016), who stated that building an adequate psychological condition is an essential aspect of HIV/AIDS medication and treatment. Patients’ acceptance of their disease and adherence to therapy is influenced by their views, beliefs, mental health, and social support (Rzeszutek et al., 2016).

Adolescents with ART can normally live like other adolescents without HIV infection. In this study, all the participants could work, help their parents with work, go to school, play, and mingle. This was in line with the finding of a study conducted by Madiba and Mokgatle (2016), who stated that teenagers want to be healthy and normal like other people. They express positive feelings in their lives, and HIV infection is not necessarily related to bad health. Most of them understand the importance of taking care of their health. Peer support plays an important role in helping people with HIV infection adapt to their normal life (Martiana et al., 2021).

Adolescents with HIV infection define normal life while using ART to perform activities like other normal adolescents and not have any physical complaints or other diseases (Kalra & Emmanuel, 2019). Adolescents with HIV infection felt healthier than those who had cancer and diabetes. The participants felt that living a normal life gave them the hope and strength to live their life with HIV infection (Smith et al., 2016).

Challenge faced by adolescents who managed their medication regarding ART adherence was that they had to remember the time of taking medicine according to the dose daily. In a study conducted by Hornschuh et al. (2017), adolescents forgot to take their ARV medication at times because they forgot to turn on the medication reminder, which affected their treatment adherence. Another study revealed that failing to take medicine was the factor due to which adolescents missed their medication and missed doses; this led to poor adherence to ART and was found to be the main factor associated with treatment nonadherence in adolescents (Wambugu et al., 2018).

In our study, adolescents mentioned that setting the alarm for medication was the most important factor in ART adherence. Medication reminders were either through a mobile phone alarm or a watch. A study in Cambodia found that the challenge in adhering to ART was the feeling of difficulty in remembering to take medicine (Chhim et al., 2018). The use of a reminder system has been proven to be effective in improving adherence and success of ART treatment in individuals with HIV infection. In a previous study, the most common reminder used by adolescents was an alarm on their mobile phone; it was an audio reminder or a picture-based reminder that automatically popped up after being set (Ekop & Okechukwu, 2018).

In addition to a technology-based reminder, a reminder from family, friends, or healthcare professionals is essential. Although an adolescent is an independent person according to their developmental stage, support from family and healthcare workers is required to prevent nonadherence to therapy (Nabunya et al., 2020). In one study, participants considered using external support to reduce their difficulty remembering the time of taking their medication. Such difficulties can be resolved by having a reminder, receiving information about the importance of not missing a dose, or being motivated to adhere to the treatment through some support (Lockwood et al., 2019).

Besides taking medication on time, challenges faced by participants in undergoing ARV treatment were feeling the side effects of drugs, forgetting to take medication, queuing when taking medication, having to regularly take medication at the same hour, getting bored of taking medication, and having large drug sizes. This is in line with research that states that the barriers and challenges to ARV adherence for children/adolescents with HIV include unpleasant drug taste, pill burden, dietary restrictions, acute and long-term side effects, coordination with daily schedules, forgetfulness, and treatment fatigue (Garvie et al., 2017).

The first challenge in undergoing treatment is the side effects of the drug. Not a few drugs have side effects. The side effects of ARVs are related to each compound as well as to host genetic factors and the patient’s lifestyle. In a study by Godfrey et al. (2017), about 94% of patients taking ARV therapy showed side effects. Discomfort caused by various side effects is an important factor that can cause patients to be less compliant or lead to discontinuation of treatment. Ten main symptoms may appear as side effects of ARV treatment, namely diarrhea, nausea or vomiting, stomach problems, dizziness, sleep problems or nightmares, weakness, weight loss, and clinical signs of anxiety (Natukunda et al., 2017). This is in line with the research of Gobel (2019), which stated that several participants noted that the side effects they often felt while undergoing ARV treatment were dizziness, nausea, vomiting, skin rashes, itching, and even hallucinations. This situation causes them to decide on treatment because they are unable to withstand the side effects that arise.

Participants in this study underwent ARV treatment for at least one year with full hope for the success of ARV treatment for their health and the future that would be achieved. The desire to live longer and healthier is the motivation for adolescents to take ARVs. This is in line with previous research that stated that most adolescents started ARVs after being sick for a long time and required them to take ARVs, so it was a valuable experience for adolescents so that it would not happen again (Denison et al., 2015). In this study, the participants expressed that their hope to be healthy became their motivation for taking ARV drugs. Based on the self-efficacy theory, patients with HIV/AIDS were found to show higher self-efficacy because they had the belief and felt the benefits of ART, which made them take ARV drugs regularly. Their self-confidence continuously grew and developed through the individual learning process throughout their lives due to performance accomplishments (Sugiharti et al., 2014). This was in line with the finding of a study conducted by Madiba and Mokgatle (2016) that adolescents took the medicines correctly to prevent illness because they wanted to be healthy and normal. In their research, most adolescents started ART after prolonged illness and felt the effect of the therapy, i.e., improved health status.

In this study, participants had hopes related to stigma, namely that people with HIV would not be shunned and still be accompanied because stigma and rejection seem to remain prominent in the lives of HIV-infected adolescents. HIV infection remains a stigmatized disease and a problem for those living with HIV infection (Abubakar et al., 2016). Participants also have hopes related to treatment, namely ARV drugs will always be there for them, and participants’ expectations regarding the future are wanting to achieve the desired goals, being able to make parents happy, and being able to build a household where no family member has HIV due to contracting from a person living with HIV. This is in line with research in India that a person with HIV can lead a healthy, normal, and productive life when they practice a positive life. Their positive approach to life, their expectations of treatment outcomes, and hopes for a good future show positive signs of life, which can ultimately lead to a good quality of life (Kalra & Emmanuel, 2019).

The limitation of the study was related to maximum variations of the participants. Most of the participants have HIV from the vertical transmission. This means that they took the medication long ago, and family support is guaranteed. Therefore, different experiences or hope might be different in adolescents who get infected from another transmission.

The implication of this study to the nursing practice is that nurses working with adolescents with HIV should identify challenges and explore adherence experiences to maintain compliance with ARVs. Nurses can also be a counselor for adolescents with HIV who take ART. As counselors, nurses can help adolescents adhere to ART by accompanying them when they get bored with the treatment. This study also provides important insight into the adolescents and their families handling problems during ART.

Conclusion

This study found that adolescents with their characteristics of not wanting to be controlled and having independent behavior can adhere to ART despite all challenges they face. A specific approach is required in adolescents; therefore, the authors used the AI approach to explore their experience in taking ARV drugs. The data showed that adolescents could live a normal life like other adolescents without HIV infection. This can be possible because of the motivation that they want always to be healthy and maintain their health to fulfill their dream and hope and to make their parents happy. Rewards should be provided for adolescents who have adhered to ART by making them role models for ARV adherence, involving them in providing education to other adolescents with HIV infection, and sharing testimonials of their experience in taking ARV drugs so that they can be proud of their ability.

Acknowledgment

The authors express their gratitude to the participants involved in this study.

Declaration of Conflicting Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in this study.

Funding

This study was supported by the Directorate of Research and Development, Universitas Indonesia, through HIBAH PUTI SAINTEKKES UI 2020.

Authors’ Contributions

NN: conception of the work, acquisition, data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. DW: conception of the work, data analysis, and reviewed draft manuscript. HH: data acquisition and analysis. INR and AW: revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors provided final approval of the version to be published.

Authors’ Biographies

Ns. Nuraidah, S.Kep., M.Kep., Sp.Kep.A is a Pediatric Nurse Specialist working in RSPI Soelianti Soeroso (an infectious disease hospital, including HIV-AIDS). Her research interest is AIDS in children.

Dessie Wanda, S.Kp., M.N., Ph.D is an Associate Professor at the Department of Pediatric Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Indonesia. Her research interests are infectious disease, clinical education, reflective practice, and qualitative research.

Ns. Happy Hayati, S.Kp., M.Kep., Sp.Kep.An is a Pediatric Nurse Specialist and a Lecturer at the Department of Pediatric Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Indonesia. She is an expert in qualitative nursing and AIDS in children.

Dr. Imami Nur Rachmawati, S.Kp., M.Sc. is an Associate Professor at the Department of Maternity Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Indonesia. Her interests are in qualitative research, adolescent reproductive health, and maternal health including women with HIV/AIDS.

Agung Waluyo, S.Kp., M.Sc., Ph.D is an Associate Professor at the Department of Medical Surgical Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Indonesia. He is an expert in HIV-AIDS in Indonesia. He has several international collaborations and publications related to HIV-AIDS.

Data Availability

Data from this research is not available publicly; however, readers interested in the data may contact the corresponding author for access.

References

- Abubakar, A., Van de Vijver, F. J. R., Fischer, R., Hassan, A. S., K Gona, J., Dzombo, J. T., Bomu, G., Katana, K., & Newton, C. R. (2016). ‘Everyone has a secret they keep close to their hearts’: Challenges faced by adolescents living with HIV infection at the Kenyan coast. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 1-8. 10.1186/s12889-016-2854-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aregbesola, O. H., & Adeoye, I. A. (2018). Self-efficacy and antiretroviral therapy adherence among HIV positive pregnant women in South-West Nigeria: A mixed methods study. Tanzania Journal of Health Research, 20(4). 10.4314/thrb.v20i4.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, & K. J. Sher (Eds.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol 2: Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological. (pp. 57-71). American Psychological Association. 10.1037/13620-004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chenneville, T., Machacek, M., Walsh, A. S. J., Emmanuel, P., & Rodriguez, C. (2017). Medication adherence in 13-to 24-year-old youth living with HIV. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 28(3), 383-394. 10.1016/j.jana.2016.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chhim, K., Mburu, G., Tuot, S., Sopha, R., Khol, V., Chhoun, P., & Yi, S. (2018). Factors associated with viral non-suppression among adolescents living with HIV in Cambodia: A cross-sectional study. AIDS Research and Therapy, 15(1), 1-10. 10.1186/s12981-018-0205-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denison, J. A., Banda, H., Dennis, A. C., Packer, C., Nyambe, N., Stalter, R. M., Mwansa, J. K., Katayamoyo, P., & McCarraher, D. R. (2015). “The sky is the limit”: Adhering to antiretroviral therapy and HIV self‐management from the perspectives of adolescents living with HIV and their adult caregivers. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 18(1), 19358. 10.7448/IAS.18.1.19358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Direktorat Jendral P2P . (2019). Laporan perkembangan HIV AIDS dan PIMS Triwulan II tahun 2019 [Report on the development of HIV AIDS and sexually transmitted infections quarter II of 2019]. https://siha.kemkes.go.id/portal/files_upload/Laporan_HIV_TW_II_20192.pdf

- Ekop, E. E., & Okechukwu, A. A. (2018). Reminder systems for improving adherence among HIV-infected adolescents attending a tertiary facility in Abuja. Asian Journal of Pediatric Research, 1(1), 1-10. 10.9734/ajpr/2018/v1i124584 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garvie, P. A., Brummel, S. S., Allison, S. M., Malee, K., Mellins, C. A., Wilkins, M. L., Harris, L. L., Patton, E. D., Chernoff, M., & Rutstein, R. M. (2017). Roles of medication responsibility, executive and adaptive functioning in adherence for children and adolescents with perinatally acquired HIV. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal, 36(8), 751-757. 10.1097/INF.0000000000001573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobel, F. A. (2019). Loss to follow up pada Odha yang menerima terapi antiretroviral di Kecamatan Ujung Bulu Kabupaten Bulukumba [Loss to follow-up on people living with HIV who receive antiretroviral therapy in Ujung Bulu District, Bulukumba Regency]. Nursing Inside Community, 1(2), 55-60. [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey, C., Thigpen, M. C., Crawford, K. W., Jean-Phillippe, P., Pillay, D., Persaud, D., Kuritzkes, D. R., Wainberg, M., Raizes, E., & Fitzgibbon, J. (2017). Global HIV antiretroviral drug resistance: A perspective and report of a national institute of allergy and infectious diseases consultation. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 216(suppl_9), S798-S800. 10.1093/infdis/jix137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornschuh, S., Dietrich, J. J., Tshabalala, C., & Laher, F. (2017). Antiretroviral treatment adherence: Knowledge and experiences among adolescents and young adults in Soweto, South Africa. AIDS Research and Treatment, 5192516. 10.1155/2017/5192516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indonesian Ministry of Health . (2019). Pedoman nasional pelayanan kedokteran tata laksana HIV [National guidelines for medical services for HIV management]. https://yankes.kemkes.go.id/view_unduhan/46/kmk-no-hk0107menkes902019

- Kalra, R., & Emmanuel, A. E. (2019). Living with HIV/AIDS: A qualitative study to assess the quality of life of adolescents (13-19 Years) attending ART Centre of Selected Hospital in New Delhi. Indian Journal of Youth and Adolescent Health, 6(1), 28-35. [Google Scholar]

- Karyadi, T. H. (2017). Keberhasilan pengobatan terapi antiretroviral [Successfulness of antiretroviral therapy]. Jurnal Penyakit Dalam Indonesia, 4(1), 1-3. 10.7454/jpdi.v4i1.105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood, N. M., Lypen, K., Shalabi, F., Kumar, M., Ngugi, E., & Harper, G. W. (2019). ‘Know that you are not alone.’Influences of social support on youth newly diagnosed with HIV in Kibera, Kenya: A qualitative study informing intervention development. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(5), 775. 10.3390/ijerph16050775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madiba, S., & Mokgatle, M. (2016). Perceptions and experiences about self-disclosure of HIV status among adolescents with perinatal acquired HIV in poor-resourced communities in South Africa. AIDS Research and Treatment, 2607249. 10.1155/2016/2607249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahathir, M., Wiarsih, W., & Permatasari, H. (2021). “Accessibility”: A new narrative of healthcare services for people living with HIV in the capital city of Indonesia. Belitung Nursing Journal, 7(3), 227-234. 10.33546/bnj.1409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martiana, I., Waluyo, A., Yona, S., & Edianto, E. (2021). A secondary analysis of peer support and family acceptance among homosexual living with HIV and antiretroviral therapy: Quality of life perspectives. Jurnal Keperawatan Indonesia, 24(1), 1-8. 10.7454/jki.v24i1.1095 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Media, Y. (2016). Pengembangan strategi dalam upaya penanggulangan HIV/AIDS melalui pendekatan sosial budaya [Strategy development in the effort to overcome HIV/AIDS through a socio-cultural approach]. Jurnal Ekologi Kesehatan, 15(1), 1-14. 10.22435/jek.v15i1.4139.1-14 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nabunya, P., Bahar, O. S., Chen, B., Dvalishvili, D., Damulira, C., & Ssewamala, F. M. (2020). The role of family factors in antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence self-efficacy among HIV-infected adolescents in southern Uganda. BMC public health, 20(1), 1-9. 10.1186/s12889-020-8361-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natukunda, H. P. M., Cluver, L. D., Toska, E., Musiime, V., & Yakubovich, A. R. (2017). Beyond clinical trials: Cross-sectional associations of combination antiretroviral therapy with reports of multiple symptoms and non-adherence among adolescents in South Africa. South African Medical Journal, 107(11), 965-975. 10.7196/SAMJ.2017.v107i11.12405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1609406917733847. 10.1177/1609406917733847 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rzeszutek, M., Oniszczenko, W., Schier, K., Biernat-Kałuża, E., & Gasik, R. (2016). Temperament traits, social support, and trauma symptoms among HIV/AIDS and chronic pain patients. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 16(2), 137-146. 10.1016/j.ijchp.2015.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S. T., Dawson-Rose, C., Blanchard, J., Kools, S., & Butler, D. (2016). “I am normal”: Claiming normalcy in Christian-identified HIV-infected adolescent and emerging adult males. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 27(6), 835-848. 10.1016/j.jana.2016.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiharti, S., Yuniar, Y., & Lestary, H. (2014). Gambaran kepatuhan orang dengan HIV-AIDS (Odha) dalam minum obat Arv di Kota Bandung, Provinsi Jawa Barat, tahun 2011-2012 [Description of adherence of people with HIV-AIDS (PLHA) in taking ARV drugs in Bandung City, West Java Province, 2011-2012]. Indonesian Journal of Reproductive Health, 5(2), 1-11. 10.22435/kespro.v5i2.3888.113-123 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS . (2019). UNAIDS data 2019. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2019-UNAIDS-data_en.pdf

- Wambugu, N., Gatongi, P., Mbuthia, J., Mokaya, J., & Ndwiga, T. (2018). Adherence to antiretroviral drugs among HIV positive adolescents at comprehensive care clinic, Gertrude’s Children Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya. American Journal of Nursing Science, 7(1), 23-30. 10.11648/j.ajns.20180701.13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data from this research is not available publicly; however, readers interested in the data may contact the corresponding author for access.