Abstract

Endemic systemic mycoses such as blastomycosis, coccidioidomycosis, histoplasmosis, talaromycosis, paracoccidioidomycosis are emerging as an important cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. We conducted a systematic review on endemic systemic mycoses reported in Italy from 1914 to nowadays. We found out: 105 cases of histoplasmosis, 15 of paracoccidioidomycosis, 10 of coccidioidomycosis, 10 of blastomycosis and 3 of talaromycosis. Most cases have been reported in returning travelers and expatriates or immigrants. Thirtytwo patients did not have a story of traveling to an endemic area. Fortysix subjects had HIV/AIDS. Immunosuppression was the major risk factor for getting these infections and for severe outcomes. We provided an overview on microbiological characteristics and clinical management principles of systemic endemic mycoses with a focus on the cases reported in Italy.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11046-023-00735-z.

Keywords: Systemic mycoses, Talaromycosis, Paracoccidioidomycosis, Blastomycosis, Coccidioidomycosis, Histoplasmosis

Introduction

The most common endemic systemic mycoses are caused by thermally dimorphic fungi [1]. This group of fungi grows as a mold at 22–25 °C and as yeasts at 37 °C [2]. Among these diseases, blastomycosis, coccidioidomycosis, histoplasmosis, talaromycosis, paracoccidioidomycosis are emerging as an important cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide [3]. They have a peculiar geographical distribution in most cases. Migratory flows and travels allow their spread also in non-endemic countries [4]. They can affect both immunocompetent and immunocompromised people, particularly those with HIV/AIDS, where they manifest with more severe outcomes [5]. Recently the International Society for Human and Animal Mycology and the European Confederation of Medical Mycology published guidelines for the diagnosis and management of the endemic mycoses [3].

In Italy many case reports and case series have been published about endemic mycoses, mostly imported from endemic areas. Systematic reviews regarding Italian cases have been conducted only about histoplasmosis [4, 6–8]. A review about cases of paracoccidioidomycosis in Europe was conducted by Wagner et al. [9].

We conducted a systematic review on endemic systemic mycoses reported in Italy. A practical update of microbiological and clinical aspects is provided.

Materials and Methods

This systematic review was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [10].

Information sources were represented by three major databases, MEDLINE, CENTRAL and Embase, screened from inception until 1st April 2022 using a combination of keywords. The detailed search strategy is described in Appendix 1 (See supplementary materials).

Records were de-duplicated before entering the subsequent phase of the review. One investigator (VZ) carried out the first selection of the retrieved records by title and abstract in order to establish eligibility for full-text review. The second step consisted of further screening of full-text articles to define final inclusion in the systematic review according to the inclusion criteria. We included case reports, case series, systematic reviews about the following mycoses: histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, talaromycosis, blastomycosis, and paracoccidioidomycosis. We included full texts written in English and Italian. Additional cases were sought from the reference list of included papers and reviews.

The following information was extracted from each article and entered into pilot-tested evidence tables: mycosis, author, year, number of cases, patients’ nationality, age, gender, comorbidities, immunocompromised status, country of exposure, clinical presentation and affected organs, isolated species, co-infections, diagnosis, antifungal therapy, and outcomes.

The authors confirm that the ethical policies of the journal, as noted on the journal’s author guidelines page, have been adhered to. No ethical approval was required as this is a review article with no original research data.

Results

Summary of the Literature

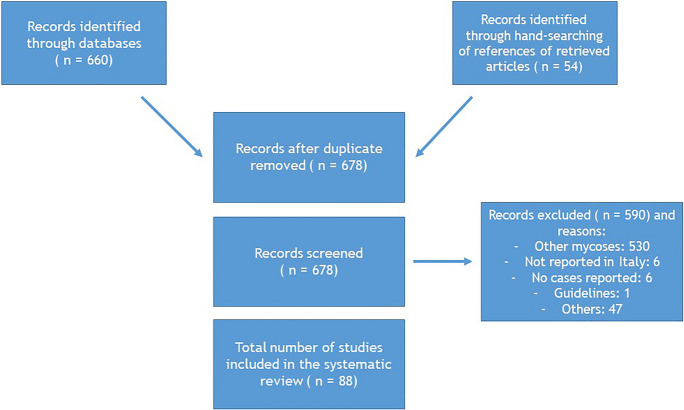

The literature search identified 88 articles about cases of histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, talaromycosis, blastomycosis, and paracoccidioidomycosis reported in Italy (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Literature selection procedure

Talaromycosis

Talaromycosis, or penicilliosis, is a systemic fungal disease caused by Talaromyces marneffei (formerly Penicillium marneffei), a dimorphic fungus classified in the group of the Eurotiales order and Trichocomaceae family [11].

It is endemic in tropical and subtropical areas of South and Southeast Asia: in Northeastern India, Southern China, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Northern Thailand [11]. Talaromycosis especially affects immunocompromised patients, in particular those with HIV infection and a CD4 count < 100 cells/µL [12]. It has become the third most common HIV-related opportunistic infection in South and SouthEast Asia [12], where it is an AIDS-defining illness [11]. Travel-related talaromycosis is being increasingly reported also in non-endemic countries [11].

Human Infections occur through inhalation of T. marneffei conidia. The transmission is seasonal, coinciding with rainy seasons [11]. Bamboo rats are the main animal reservoir of T. marneffei [11]. There is no evidence of both animal-to-person or person-to-person transmission [12].

The incubation period of the disease is variable (from 1 to 3 weeks to years) [11]. Clinical manifestations appear only after hematogenous dissemination. The signs and symptoms are similar in adults and in children [13], but differ in patients with and without HIV. Patients without HIV are more likely to have bone and joint infections but are less likely to have fever, splenomegaly, skin lesions and positive fungal blood cultures [14]. Most patients present symptoms related to reticuloendothelial system involvement, including generalized lymphadenopathy, hepatomegaly, and splenomegaly. Talaromycosis can involve respiratory system (fever, dyspnea, and chest pain); gastrointestinal system (diarrhea); central nervous system (CNS) and cause mucosal or skin involvement (lesions appear as umbilicated papule, resembling molluscum contagiosum, nodules, or necrotic lesions, and they are usually located over the face and upper trunk) [15, 16].

The diagnosis is traditionally made through the identification of the fungus in clinical specimens by microscopy and culture [11]. Microscopically, T. marneffei appears as oval or round intracellular yeasts with cross-wall formations. Cultures of bone marrow, blood and biopsies of skin lesions have the highest sensitivity [12]. Talaromyces marneffei takes from 3 to 14 days to grow up in culture [11]. Talaromyces marneffei can be observed in histopathological sections with Grocott methenamine silver or periodic acid-Schiff stain. Infected tissues appear as granulomatous, suppurative reaction, and non-reactive necrosis [11]. No commercial serological tests are available. Antigens are available instead [3]. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) based tests and next-generation sequencing (NGS) are useful tools for rapid diagnosis, even if hardly available. Galactomannan and β-D-glucan also can be helpful [11].

Disseminated disease is fatal if untreated. First choice treatment consists in liposomal amphotericin B (3–5 mg/kg per day) for 2 weeks, followed by oral itraconazole (200 mg/twice daily) for 10 weeks. If it is not possible to use amphotericin B, voriconazole or fluconazole (much less active) can be used. For immunocompromised patients itraconazole should be continued as secondary prophylaxis, until restoration of cellular immunity. For HIV patients with CD4 < 100 cells/µL living in endemic areas, primary prophylaxis with itraconazole 200 mg/day is indicated [3, 16].

Three cases of talaromycosis have been described in Italy (Table 1). All patients were immunocompromised (AIDS). Two patients were Italians who traveled to Thailand, the other one was a Chinese student living in Italy since 2016. All patients had disseminated infection, successfully treated with clinical recovery [17–19].

Table 1.

Reported cases of talaromycosis, paracoccidioidomycosis, blastomycosis and coccidioidomycosis

| Mycosis | Author, year | No patients | Nationality | Age, gender | Comorbidities | Immunocompromise | Country of infection acquisition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Talaromycosis | Antinori et al., 2006 | 1 | Italian | 36 y.o./M | Nº | Yes (AIDS) | Thailand |

| Talaromycosis | Viviani et al., 1993 | 1 | Italian | 33 y.o./M | Intravenous drug abuse; Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (treated) | Yes (AIDS) | Thailand |

| Talaromycosis | Basile et al., 2022 | 1 | Chinese | Late twenties /M | No | Yes (AIDS) | China |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Pecoraro et al., 1998 | 1 | Venezuela | 60 y.o./M | Smoker | No | Venezuela |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Scarpa et al., 1965 | 1 | Italian | 43 y.o./M | No | No | Venezuela |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Borgia et al., 2000 | 1 | Venezuela | 61 y.o./M | No | No | Venezuela |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Farris, 1955 | 1 | Italian | 66 y.o./M | No | No | Brazil |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Fulciniti et al., 1995 | 1 | Italian | 60 y.o./M | Smoker | No | Venezuela |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Benoldi et al., 1985 | 1 | Italian | 41 y.o./M | No | No | Venezuela |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Della Favera et al., 1914 | 1 | Brazilian | 13 y.o./M | Nd | Nd | Brazil |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Bertaccini et al., 1934 | 1 | Italian | Nd | Nd | Nd | Brazil |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Molese et al., 1957 | 1 | Italian | 47 y.o/M | No | No | Venezuela |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Schirladi-Grimaldi, 1963 | 1 | Italian | 36 y.o. /M | No | No | Venezuela |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Velluti et al., 1979 | 1 | Italian | 52 y.o./M | No | No | Venezuela |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Lasagni et al., 1979 | 1 | Italian | Nd | Nd | Nd | Venezuela |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Finzi et al., 1980 | 1 | Italian | 59 y.o. /M | No | No | Brazil |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Cuomo et al., 1985 | 1 | Italian | 37 y.o./M | Epilepsy | No | Venezuela |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Solaroli et al., 1998 | 1 | Italian | 49 y.o./M | No | No | Brazil |

| Blastomycosis | Codifava et al., 2012 | 1 | Ghana | 3 y.o. /M | No | No | Ghana |

| Blastomycosis | Ietto et al., 2021 | 1 | Senegal | 27 y.o. /M | Disseminated tuberculosis (treated) | No | Senegal |

| Blastomycosis | Rimondi et al., 1995 | 1 | Italian | 54 y.o. /M | No | No | None |

| Blastomycosis | Rivasi et al., 2000 | 1 | Italian | 78 y.o. /M | No | No | None |

| Blastomycosis | Rivasi et al., 2000 | 1 | Italian | 52 y. o. /M | No | No | None |

| Blastomycosis | Cavalot et al., 1992 | 1 | Italian | 57 y.o. /M | No | No | Central America |

| Blastomycosis | Sgobbi et al., 1978 | 1 | Italian | 31 y.o. /M | No | No | Canada |

| Blastomycosis | Wolf Chasen, 1951 | 1 | Italian | 25 y.o. /F | No | No | None |

| Blastomycosis | Wolf Chasen, 1951 | 1 | Italian | 19 y.o. /M | No | No | None |

| Blastomycosis | Florenzano-Zini, 1950 | 1 | Italian | 48 y.o. /F | Pulmonary tuberculosis | No | None |

| Coccidioidomycosis | Corpolongo et al., 2014 | 1 | Italian | 49 y.o. /M | No | No | Venezuela |

| Coccidioidomycosis | Tortorano et al., 2015 | 1 | Italian | 56 y.o. /F | No | No | Argentina |

| Coccidioidomycosis | D'Avino et al., 2012 | 1 | Italian | 48 y.o. /M | Disseminated cryptococcosis, CMV retinitis | Yes (AIDS) | United States |

| Coccidioidomycosis | Gobbi et al., 2012 | 1 | Italian | 28 y.o /M | Recurrent sinusitis | No | United States |

| Coccidioidomycosis | Scanarini et al., 1991 | 1 | Italian | 68 y.o /F | No | No | None |

| Coccidioidomycosis | Vilardo et al., 1964 | 1 | Italian | 43 y.o. /M | No | No | Venezuela |

| Coccidioidomycosis | Sotgiu and Corbelli, 1955 | 1 | Italian | 38 y.o. /M | No | No | United States |

| Coccidioidomycosis | Castellani, 1933 | 1 | Italian | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd |

| Coccidioidomycosis | Jacono-Boeri, 1932 | 1 | Italian | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd |

| Coccidioidomycosis | Jacono-Boeri, 1932 | 1 | Italian | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd |

| Mycosis | Clinical features | Species | Co-infection | Diagnosis | Treatment | Outcome | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Talaromycosis | Disseminated (skin; bone marrow; blood) | Talaromyces marneffei | No | Positive culture of skin, bone marrow and blood; histology (skin) | Amphotericin B, then itraconazole | Recovered | [18] |

| Talaromycosis | Disseminated (skin; pnuemonia; blood) | Talaromyces marneffei | No | Positive culture of skin, sputum and blood; histology | Amphotericin B + flucitosine, then itraconazole | Recovered (died 1 year later for other opportunistic infections) | [17] |

| Talaromycosis | Disseminated (skin; brain; blood) | Talaromyces marneffei | No | Positive culture of blood; Histology; PCR | Amphotericin B, then isavuconazole | Recovered | [19] |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Osteomyelitis; subpleural nodular formations (one excavatum) | Paracoccidioides brasiliensis | No | Histology | Ketoconazole | Recovered | [57] |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Laterocervical lymphadenopathy; ulcerated lesions of the lip; dental avulsion; pulmonary: miliary dissemination, pneumonia with excavations, hilar and carenal lymphadenopathies and endotracheal vegetation | Paracoccidioides brasiliensis | No | Histology | Amphotericin B | Death | [63] |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Pneumonia; osteomyelitis | Paracoccidioides brasiliensis | No | Positive bone culture; histology | Itraconazole | Recovered | [59] |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Skin facial plaques; larynx; pneumonia | Paracoccidioides brasiliensis | No | Histology | Diathermocoagulation + sulfonamides | Persistency | [53] |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Osteomyelitis | Paracoccidioides brasiliensis | No | Histology | Itraconazole | Slow amelioration | [58] |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Ulcerated skin plaque; pneumonia | Paracoccidioides brasiliensis | No | Histology; serology | Ketoconazole + sulfamethoxypyridazine | Recovered | [62] |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Nd | Paracoccidioides brasiliensis | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd | [52] |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Nd | Paracoccidioides brasiliensis | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd | [56] |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Pneumonia; oral mucosa and lymph nodes involvement; hepatosplenomegaly | Paracoccidioides brasiliensis | No | Histology | Nystatin | Persistency | [61] |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Generalized lymphadenopathy; Gastro-intestinal | Paracoccidioides brasiliensis | No | Positive culture of lymph nodes and feces; histology | Nystatin, then amphotericin B | Recovered | [64] |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Pneumonia | Paracoccidioides brasiliensis | No | Nd | Amphotericin B and miconazole | Recovered | [60] |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Nd | Paracoccidioides brasiliensis | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd | [60] |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Pneumonia; skin involvement | Paracoccidioides brasiliensis | No | Histology | Miconazole | Recovered | [55] |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Pneumonia; skin involvement | Paracoccidioides brasiliensis | No | Histology; serology | Ketoconazole | Recovered | [60] |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Pneumonia; brain and skin involvement | Paracoccidioides brasiliensis | No | Nd | Itraconazole | Recovered | [54] |

| Blastomycosis | Osteolytic lesion of the distal femur and muscle abscess | Blastomyces dermatitidis | No | Histology | Surgery + Amphotericin B, then itraconazole | Recovered | [25] |

| Blastomycosis | Fluid collections in psoas muscles with bone lytic lesions of the pelvis | Blastomyces dermatitidis | No | PCR; sequencing of the 18 s region | Itraconazole | Recovered | [34] |

| Blastomycosis | Adrenal insufficiency | Blastomyces dermatitidis | No | Positive culture of adrenal glands biopsy; histology | Fluconazole | Recovered | [40] |

| Blastomycosis | Nodule on the right knee | Blastomyces dermatitidis | No | Histology | Nd | Nd | [38] |

| Blastomycosis | Nodule on the right knee | Blastomyces dermatitidis | No | Histology | Nd | Nd | [38] |

| Blastomycosis | Infiltrative lesions of the lip, tongue, soft palate and epiglottis; larynx | Blastomyces dermatitidis | No | Histology | Amphotericin B, then itraconazole | Recovered | [35] |

| Blastomycosis | Pneumonia; spondylodiscitis | Blastomyces dermatitidis | No | Histology | Amphotericin B | Recovered | [36] |

| Blastomycosis | Gum nodule; odontopathy | Blastomyces dermatitidis | No | Microscopic detection | Potassium iodide + surgery | Recovered | [39] |

| Blastomycosis | Gum nodule | Blastomyces dermatitidis | Streptococcal skin infection | Microscopic detection | Potassium iodide + surgery + penicillin | Recovered | [39] |

| Blastomycosis | Pneumonia | Blastomyces dermatitidis | No | Microscopic detection | Nd | Nd | [37] |

| Coccidioidomycosis | Pneumonia | Coccidioides immitis | No | Serology | Fluconazole | Recovered | [75] |

| Coccidioidomycosis | Persistent erythematous papular plaque | Coccidioides posadasii | No | Microscopic detection; culture; histology | Itraconazole | Lost to follow up | [74] |

| Coccidioidomycosis | Lymphadenopathy | Coccidioides immitis | No | Histology | Fluconazole | Recovered | [71] |

| Coccidioidomycosis | Pneumonia | Coccidioides immitis | No | Serology; microscopic detection; positive culture of Bronchoalveolar lavage | Itraconazole | Recovered | [72] |

| Coccidioidomycosis | Pituitary granuloma | Coccidioides immitis | No | Histology | Surgery + ketoconazole | Recovered | [76] |

| Coccidioidomycosis | Pneumonia; oral involvement + Lymphadenopathy | Coccidioides immitis | No | Histology | Amphotericin B | Amelioration | [77] |

| Coccidioidomycosis | Pneumonia | Coccidioides immitis | No | Microscopic detection; culture | Nd | Amelioration | [73] |

| Coccidioidomycosis | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd | [73] |

| Coccidioidomycosis | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd | [73] |

| Coccidioidomycosis | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd | [73] |

CMV Cytomegalovirus

Blastomycosis

Blastomycosis is a systemic fungal disease caused by Blastomyces dermatitidis, a dimorphic fungus classified in the group of the Onygenales order and Ajellomycetaceae family [20]. Blastomyces gilchristii is another species identified in 2013, which causes similar disease in humans [21]. Recently another distinct species was identified in Canada: Blastomyces helicus [22].

Blastomycosis is endemic in the United States of America (USA) and Canada, particularly in the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys, in the Mid-western states and Canadian provinces that border the Great Lakes, and areas adjacent to the Saint Lawrence Seaway. B. dermatitidis is also present in Africa and India [23, 24]. No epidemiological data are available for Europe, where the disease has been reported only in travelers [25].

Blastomyces species are found in a specific ecological niche characterized by wet earth with animal droppings (especially dogs) and decaying vegetation [26, 27]. Infection in people occurs through inhalation of the conidia. Sometimes, the infection could be transmitted through direct skin inoculation (for trauma or insect bites). B. dermatitidis is usually not transmitted from person to person and not even from animal to person [26].

Approximately 50% of people exposed to blastomycosis develop symptoms, whereas the remaining 50% have asymptomatic or subclinical disease. Incubation period of blastomycosis ranges from 3 weeks to 3 months [28]. Pulmonary blastomycosis can present with acute pneumonia which mimic bacterial pneumonia or chronic pneumonia like tuberculosis and lung cancer [26]. Extrapulmonary dissemination (via hematogenous spread or direct inoculation) affects skin, bones, and male genitourinary system, in decreasing order of frequency. Skin lesions are frequently misdiagnosed as pyoderma gangrenosum or basal/squamous cell carcinoma. CNS involvement is uncommon in immunocompetent hosts; it may occur in HIV patients, either as meningitis or cranial abscesses [29].

The gold standard for diagnosis is the culture of clinical specimens. Growth on Sabouraud dextrose agar is very slow and could take up to four weeks. For this reason histopathological identification is very important. Yeast appears as 15 µm cells with thick, double-refractile walls and a single broad-based bud. Gomori methenamine silver or periodic–acid Schiff staining are usually used for tissue samples, calcofluor white or Papanicolaou stains are used for respiratory samples. Antigen testing (not commercially available as a kit) of the galactomannan component can be performed on urine, serum, bronchoalveolar lavage, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Antigenuria has a sensitivity of 75–93% and specificity of 80% in patients with proved blastomycosis. Cross-reactivity is described for histoplasmosis, paracoccidioidomycosis, and talaromycosis [30]. Serum β-d-glucan is unreliable for diagnosis of blastomycosis because the yeast cell wall contains very little of this carbohydrate [31]. Serological tests (complement fixation or immunodiffusion) are available, but they have poor sensitivity and specificity. PCR based tests are useful (even if they are still not validated) [30].

Itraconazole is the first choice for treatment in all forms (600 mg/day for 3 days, then 200–400 mg/day for 6/12 months), except in severe or life-threatening diseases. In these cases, liposomal amphotericin B (3–5 mg/kg/day) is indicated until clinical improvement, followed by itraconazole 200 mg twice daily for 6–12 months [32]. CNS blastomycosis should be treated for at least 12 months and until CNS abnormalities resolution (liposomal amphotericin B 5 mg/kg/day for 4–6 weeks, followed by an oral azole) [33].

Ten cases of blastomycosis have been described in Italy (Table 1). All patients were immunocompetent. In all cases, the species identified was B. dermatitidis. Nevertheless as all but one of the cases were diagnosed before 2013, one cannot disregard misidentifications with the recently described species B. gilchristii and B. helicus. Only four subjects have a travel history in these countries, respectively: Ghana [25], Senegal [34], Central America [35] and Canada [36]. Only two patients developed pneumonia [36, 37], the other eight presented with extrapulmonary manifestations: bone, joints and soft tissues (n = 5) [25, 34, 36, 38], oral cavity (n = 3) [35, 39] and adrenal glands (n = 1) [40]. No deaths are reported. Seven patients recovered (for three patients this information is lacking).

Paracoccidioidomycosis

Paracoccidioidomycosis is a systemic fungal disease caused by Paracoccidioides spp, a dimorphic fungus classified in the group of the Onygenales order and Ajellomycetaceae family. Two species, P. brasiliensis sensu stricto and P. lutzii, cause paracoccidioidomycosis. Recently other species have been described: P. americana, P. restrepiensis and P. venezuelensis [41–43].

Paracoccidioidomycosis is endemic in Latin America, especially in Brazil, Colombia and Venezuela. Argentina (North), Ecuador (Cuenca River valley), and Paraguay (Oriental side) are areas of moderate to high endemicity. Southern Mexico, from the Gulf of Mexico to the Pacific Coast, and Central American countries are territories of low endemicity. Few data are available for Bolivia, Peru, and Uruguay, but autochthonous cases have been reported [44]. Cases of paracoccidioidomycosis have been reported in Europe, United States, Canada, Japan, Africa, and the Middle East. All of them affected patients who visited or lived in South America [9, 44].

Paracoccidioidomycosis is a noncontagious disease, transmitted through conidia inhalation from soil and humid vegetation. Men and armadillos are the main accidental hosts [44].

Paracoccidioides species usually causes a subclinical primary pneumonia [45]. Only 1–2% of infected individuals develop clinical manifestations during their lives [46]. We can distinguish two main clinical forms of paracoccidioidomycosis: the acute or subacute form (juvenile type) and the chronic form (adult type) [45]. In endemic area, the acute/subacute form occurs in children, youths, and in adults under 30 years of age [45], but travelers can show similar clinical presentation. In this case the disease develops a few weeks or months after exposure to Paracoccidioides spp [44]. Dissemination is possible and typically causes fever, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly. Intestinal, cutaneous and neurological involvement is also possible, while lung involvement is rare [45, 46]. The chronic form affects mostly adult males and it usually consists of a reactivation of pulmonary latent foci formed during the primary infection [45], presenting with cough, dyspnea, and sputum expectoration [46]. The chronic form occurs many years after exposure to Paracoccidioides spp [44]. Dissemination is possible and typically affects lymph nodes, skin, adrenal glands, CNS, and oral mucosa [45].

The gold standard for diagnosis is the identification of the fungus in clinical specimens [44]. It appears as spherical yeast, with multiple budding yeasts surrounding a mother cell and birefringent and greenish walls [47]. P. brasiliensis cultures usually take weeks to grow [48]. Histological examination through Grocott–Gomori staining shows granuloma with giant multinucleated cells and polymorphonuclear cell infiltrates [47]. Several immunoassays are available[47]. The most used is double agar gel immunodiffusion because of its cost-effectiveness, sensitivity (> 80%) and specificity (> 90%) [44]. Serum β-d-glucan has good sensitivity but it seems to be not useful for predicting clinical response to antifungal therapy [49]. Paracoccidioides spp can be also detected by PCR based test [47].

The first choice for treatment is itraconazole (200 mg/day administered for 6–9 months in mild disease and for 12–18 months in moderate disease) [50]. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole requires a longer duration of therapy (at least 24 months), with lower cure rates, and higher relapse rates when compared to itraconazole [51]. Liposomal amphotericin B is indicated for CNS disease, severe/disseminated forms and in immunocompromised patients (3–5 mg/kg/day, followed by oral azole or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) [50]. For immunocompromised patients itraconazole should be continued until restoration of cellular immunity (secondary prophylaxis). Primary prophylaxis with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is effective also for paracoccidioidomycosis [50].

Fifteen cases of paracoccidioidomycosis have been described in Italy since 1914 (Table 1) [52]. All patients have traveled or lived in South America: 10 patients in Venezuela and the other 5 in Brazil [52–56]. Lung involvement was described in 10 patients. The other presented extrapulmonary manifestations related to bone (3) [57–59], skin and mucosa (6) [53, 54, 60–63] and lymph nodes (3) [61, 63, 64]. All patients were immunocompetent. Death occurs only in one case [63], an italian farmer who worked for four years in Venezuela and developed after five years chronic pulmonary paracoccidioidomycosis, disseminated to lymph nodes, skin and oral mucosa.

Coccidioidomycosis

Coccidioidomycosis, also known as ‘‘Valley fever’’[65], is a systemic fungal infection caused by some dimorphic fungi belonging to the genus Coccidioides which is classified in the Onygenales order and the Onygenaceae family [20]. Only two species, Coccidioides immitis and Coccidioides posadasii, have been differentiated [65].

Coccidioides species are endemic in the deserts of the North and in some areas of Central and South America [66]. In the United States, California and Arizona are the states with the most of the cases [67].

The transmission of coccidioidomycosis is seasonal. The highest incidence occurs in the fall. Coccidiomycosis is not transmitted from person to person but only through conidia inhalation from soil [66].

Primary pulmonary coccidioidomycosis is the typical clinical presentation of the disease. It could be asymptomatic, mild to moderate (often resolved without treatment) or severe. Some individuals develop pulmonary complications as pleural effusions, cavitations, fibrocavitations, and empyema. Extrapulmonary dissemination occurs in a small percentage of patients (HIV/AIDS patients have higher risk). Dissemination is described typically in these sites: bone, skin and soft tissues, CNS, and lymph nodes. Coccidioidal meningitis is fatal, when untreated [66].

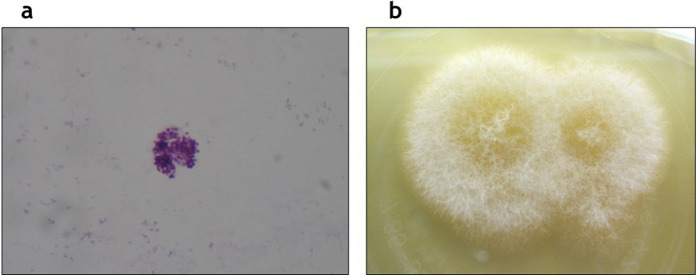

Coccidioidomycosis can be diagnosed by direct microscopic examination and culture of clinical specimens (Fig. 2a) [66]. Colonies of Coccidioides spp develop readily, usually within 3–5 days, on Sabouraud dextrose agar (Fig. 2b) [3, 68]. Through direct microscopy coccidial spherules are observed. Mature spherules are thick-walled (80 μm diameter), with endospores (2–4 μm diameter) inside [68]. Histological examination shows granulomatous inflammation. PCR based tests are also available [66]. Pulmonary coccidioidomycosis could be diagnosed by a serological test, with the immunodiffusion for the detection of precipitating specific antibodies (IgM are produced 1–3 weeks after symptoms onset, followed by IgG 4–8 weeks later) [3]. Skin tests are also feasible. Their positivity indicates past or present infection. Skin test conversion indicates infection in the intervening time [66]. Coccidioidal antigen with an enzyme immunoassay test is available (not commercially available as a kit) [3]. β-d-glucan can be useful, even if it has low sensitivity [69].

Fig. 2.

Coccidioides immitis. A Coccidial spherules through direct microscopy. B Colonies grown on Sabouraud dextrose agar after three days of incubation. [Courtesy of Chiara Savio]

Appropriate management of coccidioidomycosis requires treatment with fluconazole (400 mg/day orally) or itraconazole (200 mg 2 times daily) for patients with symptomatic chronic cavitary pneumonia, with soft tissue and bone involvement, immunocompromise and meningitis. Surgery may be considered in patients not responsive to treatment. For CNS disease the treatment is long-life (higher dosages are required). For immunocompromised patients, itraconazole should be continued until restoration of cellular immunity (secondary prophylaxis). For HIV patients in endemic areas primary prophylaxis is not indicated, but serological screening is recommended. Severe disease should be treated with liposomal amphotericin B (3–5 mg/kg/day) [70].

Ten cases of coccidioidomycosis have been described in Italy (Table 1). In particular, three cases were imported from the USA [71–73], while others were from South America (Argentina and Venezuela) [74, 75]. In four cases no travel history was reported [76]. All patients were Italian citizens. Only one case was attributed to C. posadasii [74], while in the other cases C. immitis was detected as an etiologic agent. Only one patient was immunocompromised (AIDS) [71]. No deaths were reported. In 1955 Sotgiu and Corbelli described a case of pneumonia in an Italian man who worked in the port of Genoa, who stayed in close contact with grain from North America. In this paper the authors referred to this case as the 4th described in Italy, after Castellani, Jacono and Boeri in 1933 and 1932 [73]. In 1991 Scanarini et al. reported a rare case of primary intrasellar localization of coccidioidomycosis [76]. Gobbi et al. in 2012 reported the case of a 28-years-old Italian man living in Tucson, Arizona for study purposes. He traveled in California and Nevada for visiting Sonora Desert and developed pneumonia, once coming back to Italy [72]. Tortorano et al. (2015) reported a case of a 56-years-old man with persistent erythematous papular plaque without other symptoms [74]. D'Avino et al. in 2012 reported a rare case of AIDS patient with cervical-node coccidiomycosis [71]. Four patients fully recovered [71, 72, 75, 76], two showed clinical improvement [73, 77]. For the other patients no follow-up data are available.

Histoplasmosis

Histoplasmosis is a systemic fungal disease caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, a dimorphic fungus classified in the group of the Onygenales order and Ajellomycetaceae family.

Three different varieties have been historically recognised, each with a typical geographic distribution: H. capsulatum var. capsulatum (New World, mainly in the Ohio and Mississippi River Valleys in USA, and Latin America), responsible for classic human histoplasmosis, H. capsulatum var. duboisii (Central and West Africa), responsible for African human histoplasmosis, H. capsulatum var. farciminosum (Old World, mainly in Asia) responsible for histoplasmosis in equines [78, 79]. Recent studies demonstrated that Histoplasma genus shows high diversity and four geographical clusters have been proposed for american isolates (H. capsulatum sensu stricto, H. ohiense, H. suramericanum, and H. mississippiense), but there is no consensus today on these new species [79, 80]. Some histoplasmin skin reports and case reports showed that histoplasmosis is distributed more extensively than historically thought and probably has ecological niches also in Italy and Europe [81, 82].

Histoplasmosis is transmitted through conidia inhalation from soil containing bird or bat guano [83]. It is usually not transmitted from person to person, even if transmission through solid organ transplant is reported [84].

After inhalation, about 90% of individuals exposed remain asymptomatic or develop self-limited symptoms. Pulmonary histoplasmosis can be acute, subacute, and chronic with cavitations or nodules. The incubation period is short for the acute disease (2 weeks). Dissemination is described typically in HIV/AIDS patients in: skin and soft tissues, CNS, bone marrow and lymph nodes. Physical examination usually reveals lymphadenopathy, hepatomegaly, and splenomegaly [83]. Histoplasmosis is an AIDS-defining illness [85]. The progressive disseminated form has high mortality. Skin involvement implicates diffuse maculopapular eruption and ulceration in advanced lesions [84].

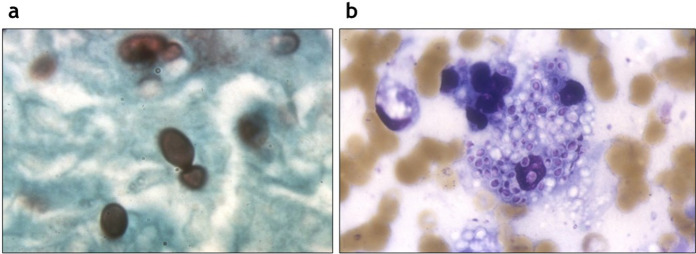

The culture of clinical specimens is routinely used for the diagnosis. Growth in Sabouraud dextrose agar culture usually takes up from 2 to 8 weeks [86]. Cultures of bone marrow, blood and respiratory samples are usefull in disseminated infection and in chronic cavitary pulmonary disease, respectively. CSF culture is often negative [84]. Histopathological evidence of H. capsulatum is one of the diagnostic criteria of proven histoplasmosis [87]. The yeast cells are ovoidal (size 2–4 μm), usually intracellular and showing narrow-based budding with Gomori methenamine silver (Fig. 3a) or periodic–acid Schiff stains. Histoplasmosis typically presents granulomatous inflammation (Fig. 3b), which may be caseating or non caseating [84]. Serological tests are available and show the highest sensitivity in subacute and chronic histoplasmosis [86]. Histoplasmosis antigen testing is mostly done on urine, but it is available (even if not validated) also on serum, bronchoalveolar lavage, and CSF. It’s useful also for monitoring the effectiveness of the therapy. The sensitivity is high in HIV/AIDS patients and in the disseminated disease (antigen detected in 95% of cases) [84]. For CNS histoplasmosis diagnosis the best combination is made by serology and CSF antigen tests [88]. Urine test for histoplasmosis antigen is indicated in patients with CD4 count < 100 cells/µL in areas where histoplasmosis is endemic, and it must be repeated every year [89]. Histoplasmosis antigen is not available worldwide (also in Italy). Cross-reactions occur with other endemic mycoses both for serologic tests and antigens [84, 86]. Serum β-d-glucan is not reliable for histoplasmosis diagnosis [31]. PCR based tests are useful (even if they are still not validated) [84].

Fig. 3.

Histoplasma capsulatum. A Yeast cells with Gomori methenamine silver stain. B Blastoconidia inside a macrophage (Giemsa stain). [Courtesy of Stefano Andreoni, Claudio Farina, Gianluigi Lombardi]

Chronic pulmonary and disseminated histoplasmosis are fatal if untreated [84]. International guidelines are available [90]. The first choice for treatment is itraconazole (600 mg/day for 3 days, then 200–400 mg/day for 12 months) for mild/moderate acute pulmonary histoplasmosis and for chronic cavitary pulmonary. For severe pulmonary disease intravenous steroids are recommended [90]. Liposomal amphotericin B is indicated in CNS disease, severe/disseminated forms and in immunocompromised patients (3–5 mg/kg/day) for 2 weeks, followed by itraconazole for at least 12 months. For immunocompromised patients itraconazole should be continued until restoration of cellular immunity and demonstration of clinical cure (secondary prophylaxis) [91]. Primary prophylaxis with itraconazole 200 mg/day is indicated for HIV patients with CD4 < 150 cells/μL living in endemic areas [84].

Systematic reviews have been conducted about cases of histoplasmosis in Italy [4, 6–8]. According to our systematic research, 105 cases of histoplasmosis have been described in Italy (Table 2). Death occurs in 20 patients (19%). For 28 patients no history of travels outside Italy was described. For all the other subjects a country of infection's acquisition was signaled. Most cases have been acquired in Ecuador (n = 20) [92–95] and in general in central and south America [96, 97]. Immunocompromised patients were 49:42 with HIV/AIDS, two with leukemia [98], one with breast cancer [99], one has Crohn disease [94], one sarcoidosis [94], one rheumatoid arthritis [100] and only one was a lung transplant recipient [101]. Among them, 14 deaths were reported (28%). Almost half of the patients (n = 48) presented disseminated histoplasmosis. Most of them had AIDS as a major risk factor. Unusual clinical presentations have also been reported: one case of endophthalmitis occurred in an Italian 64 years old man with diabetes who lived in Brazil for several years [102], and one of adrenal incidentaloma [103] in an Italian 74-year-old man who worked in Pakistan as a well-driller for 2 years. Two different clusters have been investigated. In 1997 Nasta et al. described the first one. Four Italian spelunkers, returning from Perù, presented mild acute pulmonary disease with hepatosplenomegaly with complete resolution after ketoconazole treatment [104]. The second consists of 17 members of a naturalistic expedition to Ecuador. All subjects were immunocompetent, only one presented disseminated histoplasmosis, while the other suffered from mild acute pulmonary disease. All of them recovered. Only seven patients required antifungal therapy [92].

Table 2.

Reported cases of histoplasmosis

| Mycosis | Author, year | No patients | Nationality | Age, gender | Comorbidities | Immunocompromise | Country of infection acquisition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histoplasmosis | Sotgiu and Corbelli, 1955 | 1 | Italian | 60 y.o. /M | Nd | Nd | Nd |

| Histoplasmosis | Sotgiu and Corbelli, 1955 | 1 | Italian | 31 y.o. /M | Nd | Nd | Nd |

| Histoplasmosis | Corbelli et al., 1957 | 1 | Italian | 68 y.o. /M | Nd | Nd | Nd |

| Histoplasmosis | Corbelli et al., 1957 | 1 | Italian | 32 y.o. /M | Nd | Nd | Nd |

| Histoplasmosis | Zavoli, 1957 | 1 | Italian | 39 y.o. /M | Recurrent tonsillitis, angina | No | India, East Africa |

| Histoplasmosis | Allegri and Bottiglioni, 1958 | 1 | Italian | 42 y.o. /F | Nd | Nd | Nd |

| Histoplasmosis | Costa et al., 1959 | 1 | Italian | 24 y.o. /M | Nd | Nd | Nd |

| Histoplasmosis | Salfelder et al., 1963 | 1 | Italian | 25 y.o. /F | Nd | Nd | Nd |

| Histoplasmosis | Papa et al., 1965 | 1 | Italian | 66 y.o. /M | No | No | None |

| Histoplasmosis | Mesolella et al., 1966 | 1 | Italian | 71 y.o. /M | No | No | None |

| Histoplasmosis | Altucci et al., 1968 | 1 | Italian | 54 y.o. /F | Nd | Yes (leukemia) | None |

| Histoplasmosis | Altucci et al., 1968 | 1 | Italian | 72 y.o. /F | Nd | Yes (leukemia) | None |

| Histoplasmosis | Pellegrino et al., 1977 | 1 | Nd | Nd | Nd | No | None |

| Histoplasmosis | Zanini et al., 1987 | 1 | Italian | 60 y.o. /M | Malaria (treated), edentulous | No | Africa (Nigeria, Guinea, Camerun) |

| Histoplasmosis | Masini et al., 1988 | 1 | Nd | Nd | Nd | Yes (AIDS) | Nd |

| Histoplasmosis | Vaj et al., 1989 | 1 | Italian | 31 y.o. /M | No | No | Mexico |

| Histoplasmosis | Visonà et al., 1991 | 1 | Italian | 29 y.o. /M | No | No | Ecuador |

| Histoplasmosis | Tinelli et al., 1992 | 1 | Italian | 37 y.o. /M | No | No | Africa (Nigeria, Sudan, Zaire) |

| Histoplasmosis | Biglino et al., 1992 | 1 | Italian | 41 y.o. /F | No | No | None |

| Histoplasmosis | Gori et al., 1993 | 1 | Italian | 48 y.o. /M | No | Yes (AIDS) | America |

| Histoplasmosis | Confalonieri et al., 1994 | 1 | Italian | 50 y.o. /M | Smoker, mycosis fungoides (treated with chemotherapy) | No | None |

| Histoplasmosis | Confalonieri et al., 1994 | 1 | Italian | 54 y.o. /M | Smoker | No | None |

| Histoplasmosis | Manfredi et al., 1994 | 1 | Italian | 29 y.o. /M | IDU | Yes (AIDS) | Mexico |

| Histoplasmosis | Gargiulo et al., 1995 | 1 | Ivorian | 36 y.o. /M | Nd | Yes (AIDS) | Ivory Coast |

| Histoplasmosis | Conte et al., 1996 | 1 | Brazilian | 28 y.o. /M | No | Yes (AIDS) | America |

| Histoplasmosis | Vullo et al., 1997 | 1 | Italian | 36 y.o. /M | IDU | Yes (AIDS) | United States |

| Histoplasmosis | Antinori et al., 1997 | 1 | Italian | 35 y.o. /M | Spinocellular carcinoma (treated) | Yes (AIDS) | None |

| Histoplasmosis | Nasta et al., 1997 | 1 | Italian | Late twenties /M | No | No | Perù |

| Histoplasmosis | Nasta et al., 1997 | 1 | Italian | Late twenties /M | No | No | Perù |

| Histoplasmosis | Nasta et al., 1997 | 1 | Italian | Late twenties /M | No | No | Perù |

| Histoplasmosis | Nasta et al., 1997 | 1 | Italian | Late twenties /M | No | No | Perù |

| Histoplasmosis | Angius et al., 1998 | 1 | Argentinian | 53 y.o. /M | Kaposi Sarcoma | Yes (AIDS) | Argentina |

| Histoplasmosis | Pometta et al., 1999 | 1 | Italian | 41 y.o. /M | No | No | San Salvador |

| Histoplasmosis | Faggi et al., 2000 | 1 | Brazilian | 24 y.o. /M | No | Yes (AIDS) | Brazil |

| Histoplasmosis | D'Antuono et al., 2000 | 1 | Nd | Nd | Nd | Yes (AIDS) | Nd |

| Histoplasmosis | Antinori et al., 2000 | 1 | Brazilian | 35 y.o. /M | No | Yes (AIDS) | Brazil |

| Histoplasmosis | Antinori et al., 2000 | 1 | Italian | 29 y.o. /F | IDU, Herpes Zoster (treated) | Yes (AIDS) | None |

| Histoplasmosis | Farina et al., 2000 | 1 | Italian | 43 y.o. /M | IDU, HCV chronic infection | Yes (AIDS) | None |

| Histoplasmosis | Farina et al., 2000 | 1 | Italian | 22 y.o. /M | No | No | Guatemala; Honduras |

| Histoplasmosis | Farina et al., 2000 | 1 | Venezuelan | 50 y.o. /F | Lue (treated) | Yes (AIDS) | Venezuela |

| Histoplasmosis | Farina et al., 2000 | 1 | Italian | 29 y.o. /M | No | No | Perù |

| Histoplasmosis | Farina et al., 2000 | 1 | Italian | 32 y.o. /M | IDU | Yes (AIDS) | Nepal; India; Marocco |

| Histoplasmosis | Farina et al., 2000 | 1 | Italian | 45 y.o. /F | No | No | Dominican Republic |

| Histoplasmosis | Farina et al., 2000 | 1 | Italian | 53 y.o. /F | No | No | Dominican Republic |

| Histoplasmosis | Romano et al., 2000 | 1 | Italian | 80 y.o. /M | Hypertension | Yes (rheumatoid arthritis) | None |

| Histoplasmosis | Lio et al., 2000 | 1 | Italian | 74 y.o. /M | Alcohol abuser | No | Pakistan |

| Histoplasmosis | Mignogna et al., 2001 | 1 | Tanzanian | 44 y.o. /M | No | No | Tanzania; United States |

| Histoplasmosis | Rizzi et al., 2001 | 1 | Nd | Nd | IDU | Yes (AIDS) | None |

| Histoplasmosis | Rizzi et al., 2001 | 1 | Nd | Nd | IDU | Yes (AIDS) | None |

| Histoplasmosis | Rivasi et al., 2001 | 1 | Ghana | 36 y.o. /M | Malaria, Herpes Zoster and Candida esophagitis (treated) | Yes (AIDS) | Ghana |

| Histoplasmosis | Calza et al., 2003 | 1 | Italian | 43 y.o. /M | IDU | No | None |

| Histoplasmosis | Lo Cascio et al., 2003 | 1 | Nigeria | 40 y.o. /F | Nephrotic syndrome | Yes (AIDS) | Nigeria |

| Histoplasmosis | Faggian et al., 2004 | 1 | Nigeria | 40 y.o. /F | Nephrotic syndrome | Yes (AIDS) | Nigeria |

| Histoplasmosis | Faggian et al., 2004 | 1 | Colombian | 29 y.o. /M | Pulmonary tuberculosis | Yes (AIDS) | Colombia |

| Histoplasmosis | Garavelli et al., 2005 | 1 | Colombian | 28 y.o. /M | Kaposi Sarcoma | Yes (AIDS) | Colombia |

| Histoplasmosis | Farina et al., 2005 | 1 | Italian | 45 y.o. /M | No | No | Nicaragua |

| Histoplasmosis | Farina et al., 2005 | 1 | Ivorian | 37 y.o./F | No | Yes (AIDS) | Ivory Coast |

| Histoplasmosis | Farina et al., 2005 | 1 | Ivorian | 48 y.o. /M | No | Yes (AIDS) | Ivory Coast |

| Histoplasmosis | Farina et al., 2005 | 1 | Italian | 41 y.o. /F | No | Yes (AIDS) | None |

| Histoplasmosis | Antinori et al., 2006 | 1 | Ivorian | 30 y.o. /M | Herpes Zoster (treated) | Yes (AIDS) | Ivory Coast |

| Histoplasmosis | Antinori et al., 2006 | 1 | Brazilian | 29 y.o. /F | No | Yes (AIDS) | Brazil |

| Histoplasmosis | Antinori et al., 2006 | 1 | Brazilian | 29 y.o. /M | PJP (treated) | Yes (AIDS) | Brazil |

| Histoplasmosis | Antinori et al., 2006 | 1 | Italian | 42 y.o. /M | IDU | Yes (AIDS) | South America |

| Histoplasmosis | Galetta et al., 2007 | 1 | Italian | 64 y.o. /F | Malaria (treated) | Yes (Breast cancer) | Costa Rica |

| Histoplasmosis | Bartoloni et al., 2011 | 1 | Ecuadorian | 35 y.o. /M | No | Yes (AIDS) | Ecuador |

| Histoplasmosis | Inojosa et al., 2011 | 1 | Ghana | 30 y.o. /M | Hypertension | Yes (AIDS) | Ghana |

| Histoplasmosis | Inojosa et al., 2011 | 1 | Liberia | 32 y.o. /M | No | Yes (AIDS) | Liberia |

| Histoplasmosis | Inojosa et al., 2011 | 1 | Senegal | 47 y.o. /M | PJP (treated), HBV chronic infection | Yes (AIDS) | Senegal |

| Histoplasmosis | Inojosa et al., 2011 | 1 | Ivorian | 40 y.o. /F | No | Yes (AIDS) | Ivory Coast |

| Histoplasmosis | Fortuna et al., 2011 | 1 | Italian | 67 y.o. /M | No | No | None |

| Histoplasmosis | Scarlata et al., 2011 | 1 | Ghana | 36 y.o. /M | No | Yes (AIDS) | Ghana |

| Histoplasmosis | Grancini et al., 2013 | 1 | Italian | 64 y.o. /M | Diabetes with retinopathy, chronic renal failure, cardiovascular disease | No | Brazil |

| Histoplasmosis | Ardizzoni et al., 2013 | 1 | Italian | 30 y.o. /M | No | No | Brazil |

| Histoplasmosis | Righi et al., 2014 | 1 | Italian | 63 y.o. /M | Sarcoidosis | Yes (Lung transplant) | None |

| Histoplasmosis | Amadori et al., 2015 | 1 | Brazilian | 24 y.o. /M | No | Yes (AIDS) | Brazil |

| Histoplasmosis | Amadori et al., 2015 | 1 | Thailand | 39 y.o. /F | HBV and HCV hepatitis | Yes (AIDS) | Thailand |

| Histoplasmosis | Delfino et al., 2015 | 1 | Ecuadorian | 32 y.o. /M | Pulmonary tuberculosis (incompletely treated) | Yes (AIDS) | Ecuador |

| Histoplasmosis | Bonsignore et al., 2017 | 1 | Italian | 43 y.o. /F | Splenectomy | No | None |

| Histoplasmosis | Zanotti et al., 2018 | 1 | Ivorian | 19 y.o. /F | No | Yes (AIDS) | Ivory Coast |

| Histoplasmosis | Papalini et al., 2019 | 1 | Cuban | 33 y.o. /F | No | Yes (AIDS) | Cuba |

| Histoplasmosis | Staffolani et al., 2020 | 17 | Nd | 11/17 male; 38.5 mean age (years) | Nd | No | Ecuador |

| Histoplasmosis | Staffolani et al., 2020 | 1 | Nd | Nd | No | No | Bolivia |

| Histoplasmosis | Staffolani et al., 2020 | 1 | Nd | Nd | No | No | Mexico |

| Histoplasmosis | Staffolani et al., 2020 | 1 | Nd | Nd | No | No | Mexico |

| Histoplasmosis | Staffolani et al., 2020 | 1 | Nd | Nd | No | No | Cuba |

| Histoplasmosis | Staffolani et al., 2020 | 1 | Nd | Nd | Nd | Yes (Crohn Disease) | Panama |

| Histoplasmosis | Staffolani et al., 2020 | 1 | Nd | Nd | Nd | Yes (Sarcoidosis) | South America |

| Histoplasmosis | Asperges et al., 2021 | 1 | Colombian | 42 y.o. /F | No | Yes (AIDS) | Colombia |

| Histoplasmosis | Antinori et al., 2021 | 1 | Brazilian | 27 y.o. /M | Disseminated tuberculosis (treated) | Yes (AIDS) | Brazil |

| Mycosis | Clinical features | Species | Co-infection | Diagnosis | Treatment | Outcome | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histoplasmosis | Primary pulmonary | Histoplasma capsulatum | Nd | Positive culture of blood; histology | Nd | Death | [73] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated | Histoplasma capsulatum | Nd | Histology | Nd | Recovered | [73] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated | Histoplasma capsulatum | Nd | Histology | Nd | Death | [112] |

| Histoplasmosis | Hepatosplenic localizations | Histoplasma capsulatum | Nd | Histology | Nd | Death | [112] |

| Histoplasmosis | Oral lesions | Histoplasma capsulatum | No | Positive culture of oral biopsy | Potassium iodide, then N-methyl glucamine antimoniate | Recovered | [113] |

| Histoplasmosis | Primary pulmonary | Histoplasma capsulatum | Nd | Histology | Nd | Improvement | [114] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated | Histoplasma capsulatum | Nd | Histology | Nd | Death | [115] |

| Histoplasmosis | Primary pulmonary | Histoplasma capsulatum | Nd | Histology | Nd | Recovered | [116] |

| Histoplasmosis | Skin involvement; hepatomegaly | Histoplasma capsulatum | No | Histology | Nd | Recovered | [117] |

| Histoplasmosis | Laryngeal lesions | Histoplasma capsulatum | No | Positive culture of oral biopsy; histology | N-methyl glucamine antimoniate, nystatin, sulfonamides | Recovered | [118] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated | Histoplasma capsulatum | Nd | Positive culture of blood and bone marrow | Amphotericin B | Death | [98] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated | Histoplasma capsulatum | Nd | Positive culture of bone marrow | Nd | Death | [98] |

| Histoplasmosis | Acute pulmonary disease | Histoplasma capsulatum | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd | [119] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Lungs; skin; lymph nodes; oropharyngeal and gingival ulcers) | Histoplasma capsulatum | No | Histology | Amphotericin B | Recovered | [120] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Lungs; liver) | Histoplasma capsulatum | Disseminated candidiasis, myocardial and cerebral toxoplasmosis | Histology | Nd | Nd | [121] |

| Histoplasmosis | Acute pulmonary disease (mild) with hepatosplenomegaly | Histoplasma capsulatum | No | Nd | Nd | Recovered | [122] |

| Histoplasmosis | Chronic nodular pneumonia | Histoplasma capsulatum | No | Histology | Nd | Nd | [94] |

| Histoplasmosis | Recurrent pulmonary histoplasmosis with hepatosplenomegaly | Histoplasma capsulatum | No | Positive culture of lung biopsy; histology; serology | Ketoconazole, then amphotericin B | Recovered | [123] |

| Histoplasmosis | Pneumonia (mild) | Histoplasma capsulatum | No | Histology | Fluconazole | Recovered | [124] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Liver; spleen; lymph nodes; urine) | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | No | Positive culture of urine and lymph node biopsy; histology | Amphotericin B, then Ketoconazole | Recovered | [125] |

| Histoplasmosis | Tracheobronchial and pulmonary histoplasmosis with cavitation | Histoplasma capsulatum | CMV gastroenteritis | Histology | Amphotericin B + ketoconazole | Death | [81] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Lungs; spleen; liver; oropharyngeal, epiglottic and laryngeal ulcers) | Histoplasma capsulatum | No | Histology; serology | Amphotericin B, then itraconazole | Recovered | [81] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Lungs; liver; spleen; lymph nodes; bone marrow;) | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | Oropharyngeal candidiasis, visceral leishmaniasis, pulmonary tuberculosis, S. epidermidis bacteremia | Positive culture of blood; histology | Fluconazole | Death | [126] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Lungs; skin; bone marrow) | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | Nd | Positive culture of sputum | Amphotericin B | Recovered | [127] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Lungs; spleen; liver; skin; blood; bone marrow) | Histoplasma capsulatum | Oropharyngeal candidiasis | Positive culture of blood; histology | Fluconazole | Death | [128] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (CNS; spleen; liver; lymph nodes; oropharynx; blood) | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | No | Positive culture of CSF; blood and bone marrow; histology | Amphotericin B, then itraconazole | Death | [129] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (skin; bone marrow; lungs; spleen; liver; lymph nodes) | Histoplasma capsulatum | No | Histology | Amphotericin B + itraconazole | Death | [130] |

| Histoplasmosis | Acute pulmonary disease (mild) with hepatosplenomegaly | Histoplasma capsulatum | No | Serology | Ketoconazole | Recovered | [104] |

| Histoplasmosis | Acute pulmonary disease (mild) with hepatosplenomegaly | Histoplasma capsulatum | No | Serology | Ketoconazole | Recovered | [104] |

| Histoplasmosis | Acute pulmonary disease (mild) with hepatosplenomegaly | Histoplasma capsulatum | No | Serology | Ketoconazole | Recovered | [104] |

| Histoplasmosis | Acute pulmonary disease (mild) with hepatosplenomegaly | Histoplasma capsulatum | No | Serology | Ketoconazole | Recovered | [105] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (skin; blood; liver) | Histoplasma capsulatum | No | Positive culture of blood and skin; histology | Fluconazole, then itraconazole | Recovered (died 8 months later for other reasons) | [131] |

| Histoplasmosis | Chronic pulmonary disease | Histoplasma capsulatum | No | Histology | Itraconazole | Recovered | [132] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Heart; blood) | Histoplasma capsulatum | Oral candidiasis | Positive culture of blood | Fluconazole | Death | [133] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated | Histoplasma capsulatum | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd | [134] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Bone marrow; skin; liver; lymph nodes; spleen; blood) | Histoplasma capsulatum | Lue | Positive culture of blood, skin and bone marrow; histology | Amphotericin B, then itraconazole | Recovered | [135] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Lungs; bone marrow; liver; lymph nodes; spleen; kidney; heart) | Histoplasma capsulatum | No | Histology (post mortem) | None | Death | [135] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Lungs; skin; blood) | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | No | Positive culture of blood; histology | Amphotericin B | Recovered (died 1 year later for other opportunistic infections) | [8] |

| Histoplasmosis | Acute pulmonary disease | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | No | Histology | Itraconazole | Recovered | [8] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Lungs; blood) | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | No | Positive cultures of blood; serology | Itraconazole | Recovered (died 2 years later for Kaposi Sarcoma) | [8] |

| Histoplasmosis | Acute pulmonary disease (mild) with hepatosplenomegaly | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | No | Serology | Ketoconazole | Recovered | [8] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Lungs; skin; blood) | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | No | Positive cultures of blood; histology | Amphotericin B | Nd | [8] |

| Histoplasmosis | Acute pulmonary disease | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | No | Serology | Ketoconazole, then itraconazole | Recovered | [8] |

| Histoplasmosis | Acute pulmonary disease | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | No | Serology | Amphotericin B, then itraconazole | Recovered | [8] |

| Histoplasmosis | Large hand ulcer | Histoplasma capsulatum | No | Positive culture of skin biopsy; histology | Itraconazole, then fluconazole | Recovered | [100] |

| Histoplasmosis | Adrenal insufficiency (of bilateral surrenal masses) | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | Helicobacter pylori gastritis | Histology | Itraconazole | Recovered | [103] |

| Histoplasmosis | Ulcerated lesion of the tongue | Histoplasma capsulatum | No | Histology | Fluconazole | Recovered | [136] |

| Histoplasmosis | Pulmonary histoplasmosis with nodules | Histoplasma capsulatum | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd | [137] |

| Histoplasmosis | Pulmonary histoplasmosis with focal consolidation | Histoplasma capsulatum | Nd | Nd | Nd | Nd | [137] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Skin; Lungs) | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | No | Histology; PCR | Nd | Lost to follow up | [107] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Lungs with mediastinal lymph node involvement; blood; skin; spleen) | Histoplasma capsulatum | Bacterial pneumonia | Positive culture of blood; histology | Amphotericin B, then itraconazole | Recovered | [138] |

| Histoplasmosis | Papular-ulcerative lesions of trunk, arms and face | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | No | Positive culture of skin biopsy; histology; PCR | Itraconazole | Recovered | [139] |

| Histoplasmosis | Papular-ulcerative lesions of trunk, arms and face | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | Esophageal candidiasis | Histology | Itraconazole | Recovered | [140] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Lungs; spleen; liver; lymph nodes; skin; ulcerated palatal lesion) | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | Oropharyngeal candidiasis | Positive culture os skin biopsy; histology; serology | Fluconazole, then itraconazole | Recovered | [140] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Spleen; blood; lymph nodes) | Histoplasma capsulatum | No | Positive culture of blood; histology | Itraconazole | Nd | [141] |

| Histoplasmosis | Acute pulmonary disease | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | No | Serology | Itraconazole | Recovered | [7] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Lungs; blood) | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | Salmonellosis | Positive cultures of blood; histology | Amphotericin B, then itraconazole | Recovered | [7] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Lungs; lymph nodes; blood) | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | PJP | Positive cultures of blood | Itraconazole | Death | [7] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Lungs; blood) | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | PJP, vaginal and tracheo-bronchial candidiasis | Positive cultures of blood | Amphotericin B, then itraconazole | Recovered | [7] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Liver; spleen; lymph nodes; bone marrow) | Histoplasma capsulatum var duboisii | Mac | Histology | Itraconazole | Recovered | [6] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Skin; liver; lungs; spleen; lymph nodes; kidney; heart; brain; stomach; uterus; ovary; adrenal glands) | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | PJP | Histology (post mortem) | None | Death | [6] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Skin; lungs; liver; lymph nodes) | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | No | Histology (post mortem) | None | Death | [6] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Lungs; skin; blood) | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | No | Positive culture of blood and skin; histology | Amphotericin B, then itraconazole | Lost to follow up | [6] |

| Histoplasmosis | Solitary Pulmonary Nodule | Histoplasma capsulatum | No | Histology | Surgery | Recovered | [99] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Lungs; spleen; lymph nodes) | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | No | Histology | Amphotericin B | Recovered | [95] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Skin; bone marrow; spleen; liver; lymph nodes) | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | Strongyloides stercoralis infection | Histology | Amphotericin B, then itraconazole | Lost to follow up | [142] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Lungs; palatal ulcer; spleen; liver; lymph nodes) | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | Pulmonary tuberculosis | Positive culture of palatal biopsy; histology | Amphotericin B, then fluconazole | Lost to follow up | [142] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Lungs; bone marrow; skin) | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | Strongyloides stercoralis infection, oral candidiasis | Histology | Amphotericin B, then itraconazole | Recovered | [142] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Kidney; bone marrow; lymph nodes; spleen; liver) | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | Disseminated CMV | Positive culture of bone marrow; histology | Amphotericin B, then itraconazole | Recovered | [142] |

| Histoplasmosis | Ulcerated palatal lesion | Histoplasma capsulatum | No | Histology | Nd | Nd | [143] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Lungs; lymph nodes; CNS; skin; spleen; liver) | Histoplasma capsulatum | No | Histology | Amphotericin B, then itraconazole | Recovered | [144] |

| Histoplasmosis | Endophthalmitis with CNS involvement | Histoplasma capsulatum | No | Positive culture of vitreous biopsy; histology; PCR | Fluconazole, then Itraconazole, then Amphotericin B | Death | [102] |

| Histoplasmosis | Acute pulmonary disease (mild) with involvement of mediastinal lymph nodes, erythema nodosum and polyarthralgia | Histoplasma capsulatum | No | Histology; serology | None | Recovered | [145] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Lungs; mediastinal lymph nodes; bone marrow) | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | No | Positive culture of BAL and bone marrow; PCR | Caspofungin, then Amphotericin B | Death | [101] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Lymph nodes; spleen; liver) | Histoplasma capsulatum | Cerebral toxoplasmosis | Positive culture of lymph nodes; histology; serology | Amphotericin B, then itraconazole | Recovered | [97] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Lungs; lymph nodes) | Histoplasma capsulatum | Esophageal candidiasis | PCR | Amphotericin B, then itraconazole | Recovered | [97] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Lungs; skin) | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | No | Positive culture of skin and lungs biopsy; histology; positive β-D-glucan and galactomannan | Amphotericin B, then itraconazole | Recovered | [93] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Lungs; liver; kidney; lymph nodes) | Histoplasma capsulatum | Disseminated candidiasis | Positive culture of blood; histology (post mortem) | Nd | Death | [146] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Bone marrow; lymph nodes; tonsils; gastro-intestinal) | Histoplasma capsulatum | No | Positive culture of bone marrow; histology | Amphotericin B, then itraconazole | Recovered | [85] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Lungs; skin; spleen; liver; lymph nodes) | Histoplasma capsulatum | No | Positive culture of blood and bone marrow; histology | Amphotericin B, then itraconazole | Recovered | [96] |

| Histoplasmosis | Acute pulmonary disease; 1/17 Disseminated | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | No | Serology (2/15) | Itraconazole (7/17) | Recovered | [92] |

| Histoplasmosis | Acute pulmonary disease | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | No | Nd | Itraconazole | Recovered | [92] |

| Histoplasmosis | Acute pulmonary disease | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | No | Nd | Itraconazole | Recovered | [92] |

| Histoplasmosis | Acute pulmonary disease | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | No | Nd | Itraconazole | Recovered | [92] |

| Histoplasmosis | Acute pulmonary disease | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | No | Nd | Itraconazole | Recovered | [92] |

| Histoplasmosis | Acute pulmonary disease | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | No | Positive culture of BAL; serology | Itraconazole | Recovered | [92] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Lungs; bone marrow; lymph nodes) | Histoplasma capsulatum var capsulatum | No | Positive culture of BAL; histology; serology | Itraconazole | Recovered | [92] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Lungs; lymph nodes; blood; gastrointestinal) | Histoplasma capsulatum | No | Microscopic smear identification; positiver culture of blood; serology | Amphotericin B | Death | [147] |

| Histoplasmosis | Disseminated (Lungs; liver; spleen; lymph nodes) | Histoplasma capsulatum | Oral candidiasis | Histology; PCR | Amphotericin B, then itraconazole | Recovered | [4] |

CMV Cytomegalovirus, HBV Hepatitis B virus, HCV Hepatitis C virus, IDU Intravenous drug user, PJP Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia, BAL Bronchoalveolar lavage

Discussion

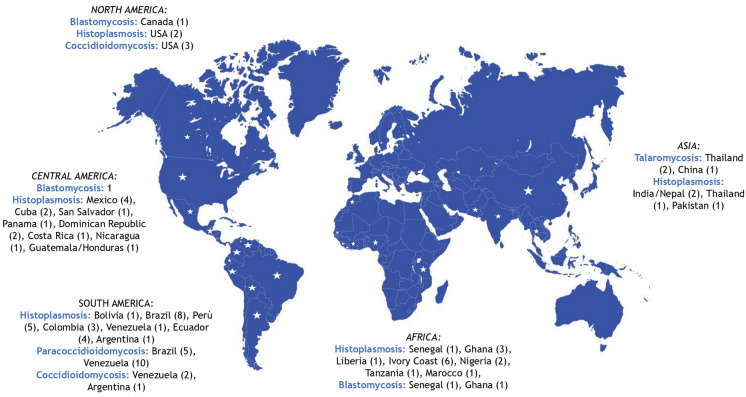

We found out from 1914 to nowadays: 105 cases of histoplasmosis, 15 of paracoccidioidomycosis, 10 of coccidioidomycosis, 10 of blastomycosis and 3 of talaromycosis reported in Italy (Fig. 4). The most reported infection in Italy is histoplasmosis and this probably reflects its global distribution [79]. Typically, cases of endemic mycoses in non endemic countries are described in travelers, expatriates and migrants [1]. The understanding of the epidemiology of such diseases is still in progress [105].

Fig. 4.

Countries of infection acquisition

In Italy a national surveillance system of endemic mycoses is missing. Moreover, the diagnosis of these mycoses is often difficult because clinical experience of physicians and diagnostic tests both are lacking (except for some reference centers). Thus, our data probably don’t reflect the real epidemiology of endemic mycoses in the country. In Spain, recently, Molina-Morant et al. reviewed the literature about endemic mycoses in the country between 1997 and 2014. There were 286 cases of histoplasmosis, 94 of coccidioidomycosis and 25 of paracoccidioidomycosis [106].

The period between the last time spent in an endemic area and the time of diagnosis sometimes is very long and could last years [62, 74, 107]. This latency period usually is longer for migrants or expatriates rather than travelers [4]. This reminds us how important it is to accurately collect the entire traveling history of the patient.

Among 143 cases of fungal infections reported here, death occurs in 21 cases (20 histoplasmosis, and one paracoccidioidomycosis). Mortality rate was 14.7% (21 deaths/143 cases). Immunosuppression is a major risk factor for getting these mycoses and for more severe outcomes [8]. Immunocompromised patients were 54 and among them 46 had HIV/AIDS. Mortality rate was 26% in immunocompromised patients (14 deaths/54 cases). Other reported conditions of immunosuppression were: cancer, inflammatory bowel diseases, sarcoidosis, rheumatologic disorders. We collect only one case of histoplasmosis in a lung transplant recipient [101]. However, this topic is emerging worldwide, considering the increasing use of immunosuppressive drugs for many diseases. In 2019 the American Society of Transplantation published their guidelines on diagnosis, prevention and management of blastomycosis, histoplasmosis, and coccidioidomycosis, that are endemic in USA, in the pre‐ and post- transplant period [108].

For histoplasmosis (n = 28), coccidioidomycosis (n = 4), and blastomycosis (n = 6), cases in people who never traveled or have links to endemic regions have been reported. So, these cases could be considered as autochthonous. In particular, evidence about the presence of Histoplasma spp in Italy has been documented by isolation in soil [109], cases in animals [110, 111] and histoplasmin reactivity surveys [81, 98]. No similar studies have been conducted in Italy for coccidioidomycosis, and blastomycosis. Nevertheless, species identification for the above mentioned isolations from soil or animals only relied on morphological features, and only one of these possible autochthonous cases was diagnosed by PCR-based tests.

In non-endemic countries the diagnosis of endemic mycoses could be challenging. Even if the culture remains the gold standard, PCR based tests detected the fungus in 8 cases (4 of these with negative cultures of clinical samples). Most of the described cases were diagnosed by histology and/or cultures. Serology and antigen testing have been less diriment.

Conclusions

The increasing trend of international travels, migration flows alongside the increasing number of persons living with immunosuppression conditions (e.g. solid organ transplants) has led to an increase of imported cases of endemic mycoses in non endemic countries such as Italy. A story of travels and immunosuppression should lead clinicians to consider endemic mycoses in differential diagnosis of systemic diseases.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Chiara Savio (Department of Infectious—Tropical Diseases and Microbiology, IRCCS Sacro Cuore—Don Calabria Hospital, Negrar di Valpolicella, Verona, Italy) for images concession. We thank Dr. Luca Tirloni for his kind help. We thank the AMCLI (Associazione Microbiologi Clinici Italiani) Committee for Mycology members: Gianluigi Lombardi; Stefano Andreoni; Elisabetta Blasi; Claudio Farina; Paolo Fazii, Silvana Sanna; Laura Trovato; Giuliana Lo Cascio.

Authors Contributions

Conceptualization, SDB and LP; methodology, AA and LP; investigation, VZ, RP, FDA; writing, review and editing, VZ, RP, FDA, SDB, LP, AA, CF, GL; supervision, MC, FL, RL. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Trieste within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. A.A.’s work was partly funded by the Italian Ministry of Health “Fondi Ricerca Corrente” to IRCCS Sacro Cuore—Don Calabria Hospital—Linea 1.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

None to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Verena Zerbato, Email: verena.zerbato@gmail.com.

Stefano Di Bella, Email: stefano932@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Bonifaz A, Vázquez-González D, Perusquía-Ortiz AM. Endemic systemic mycoses: coccidioidomycosis, histoplasmosis, paracoccidioidomycosis and blastomycosis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2011;9:705–714. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2011.07731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gauthier GM. Fungal dimorphism and virulence: molecular mechanisms for temperature adaptation, immune evasion, and in vivo survival. Mediat Inflamm. 2017;2017:8491383. doi: 10.1155/2017/8491383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson GR, 3rd, Le T, Chindamporn A, et al. Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of the endemic mycoses: an initiative of the European Confederation of Medical Mycology in cooperation with the International Society for Human and Animal Mycology. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:e364–e374. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00191-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antinori S, Giacomelli A, Corbellino M, et al. Histoplasmosis diagnosed in Europe and Israel: a case report and systematic review of the literature from 2005 to 2020. J Fungi. 2021 doi: 10.3390/jof7060481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ashraf N, Kubat RC, Poplin V, et al. Re-drawing the maps for endemic mycoses. Mycopathologia. 2020;185:843–865. doi: 10.1007/s11046-020-00431-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antinori S, Magni C, Nebuloni M, et al. Histoplasmosis among human immunodeficiency virus-infected people in Europe: report of 4 cases and review of the literature. Medicine. 2006;85:22–36. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000199934.38120.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farina C, Rizzi M, Ricci L, et al. Imported and autochthonous histoplasmosis in Italy: new cases and old problems. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2005;22:169–171. doi: 10.1016/S1130-1406(05)70034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farina C, Gnecchi F, Michetti G, et al. Imported and autochthonous histoplasmosis in Bergamo province, Northern Italy. Scand J Infect Dis. 2000;32:271–274. doi: 10.1080/00365540050165901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagner G, Moertl D, Glechner A, et al. Paracoccidioidomycosis diagnosed in Europe—a systematic literature review. J Fungi. 2021 doi: 10.3390/jof7020157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao C, Xi L, Chaturvedi V. Talaromycosis (Penicilliosis) due to Talaromyces (Penicillium) marneffei: insights into the clinical trends of a major fungal disease 60 years after the discovery of the pathogen. Mycopathologia. 2019;184:709–720. doi: 10.1007/s11046-019-00410-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ustianowski AP, Sieu TPM, Day JN. Penicillium marneffei infection in HIV. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2008;21:31–36. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3282f406ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sirisanthana V, Sirisanthana T. Disseminated Penicillium marneffei infection in human immunodeficiency virus-infected children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1995;14:935–940. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199511000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawila R, Chaiwarith R, Supparatpinyo K. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of penicilliosis marneffei among patients with and without HIV infection in Northern Thailand: a retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:464. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Supparatpinyo K, Khamwan C, Baosoung V, et al. Disseminated Penicillium marneffei infection in Southeast Asia. Lancet. 1994;344:110–113. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(94)91287-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents Recommendations from CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America; 2009 [PubMed]

- 17.Viviani MA, Tortorano AM, Rizzardini G, et al. Treatment and serological studies of an Italian case of penicilliosis marneffei contracted in Thailand by a drug addict infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Eur J Epidemiol. 1993;9:79–85. doi: 10.1007/BF00463094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Antinori S, Gianelli E, Bonaccorso C, et al. Disseminated Penicillium marneffei infection in an HIV-positive Italian patient and a review of cases reported outside endemic regions. J Travel Med. 2006;13:181–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2006.00039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Basile G, Piccica M, Vellere I, et al. Disseminated talaromyces infection in an AIDS patient. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022;28:64–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dukik K, Muñoz JF, Jiang Y, et al. Novel taxa of thermally dimorphic systemic pathogens in the Ajellomycetaceae (Onygenales) Mycoses. 2017 doi: 10.1111/myc.12601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown EM, McTaggart LR, Zhang SX, et al. Phylogenetic analysis reveals a cryptic species Blastomyces gilchristii, sp. nov. within the human pathogenic fungus Blastomyces dermatitidis. PLoS ONE. 2013 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwartz IS, Wiederhold NP, Hanson KE, et al. Blastomyces helicus, a new dimorphic fungus causing fatal pulmonary and systemic disease in humans and animals in Western Canada and the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2019 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baily GG, Robertson VJ, Neill P, et al. Blastomycosis in Africa: clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 1991;13:1005–1008. doi: 10.1093/clinids/13.5.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Randhawa HS, Chowdhary A, Kathuria S, et al. Blastomycosis in India: report of an imported case and current status. Med Mycol. 2013 doi: 10.3109/13693786.2012.685960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Codifava M, Guerra A, Rossi G, et al. Unusual osseous presentation of blastomycosis in an immigrant child: a challenge for European pediatricians. Ital J Pediatr. 2012 doi: 10.1186/1824-7288-38-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saccente M, Woods GL. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:367–381. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00056-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shelnutt LM, Kaneene JB, Carneiro PAM, et al. Prevalence, distribution, and risk factors for canine blastomycosis in Michigan, USA. Med Mycol. 2019;58:609–616. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myz110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klein BS, Vergeront JM, Davis JP. Epidemiologic aspects of blastomycosis, the enigmatic systemic mycosis. Semin Respir Infect. 1986;1:29–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bradsher RW., Jr The endemic mimic: blastomycosis an illness often misdiagnosed. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2014;125:188–202. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mazi PB, Rauseo AM, Spec A. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2021;35:515–530. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2021.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Girouard G, Lachance C, Pelletier R. Observations on (1–3)-beta-D-glucan detection as a diagnostic tool in endemic mycosis caused by Histoplasma or Blastomyces. J Med Microbiol. 2007;56:1001–1002. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47162-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Limper AH, Knox KS, Sarosi GA, et al. An official American thoracic society statement: treatment of fungal infections in adult pulmonary and critical care patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:96–128. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2008-740ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chapman SW, Dismukes WE, Proia LA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of blastomycosis: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1801–1812. doi: 10.1086/588300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ietto G, Baj A, Parise C, et al. Blastomycosis of the psoas muscles. IDCases. 2021;24:e01156. doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2021.e01156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cavalot AL, Cravero L, Valente G, et al. Blastomycosis of the cervicofacial area: a review of the literature and case report. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 1992;12:605–610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sgobbi S, Bellando-Randone P. Systemic North American blastomycosis. Chir Organi Mov. 1978;64:439–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]