Abstract

In India, breast cancer is the most common cause of mortality for women and has the potential to spread to other body organs. As a transcription factor, interactions with the estrogen receptor (ER) alpha are primarily responsible for the development of malignant tumors. Aromatase inhibitors are the most often used treatment for ER(+) breast cancer. Various synthetic compounds have been developed over the years to block the aromatase receptor, however, the majority of them are hazardous and cause multidrug resistance. So, combating these natural drugs can be prioritized. The current study was conducted to investigate the anticancer potential of Lagenaria siceraria phytoconstituents against breast cancer target protein (PDB ID: 3EQM) based on a literature review. In this study, 34 Lagenaria siceraria ligands were chosen, and the structure of the human aromatase receptor was acquired from the protein data bank. For those natural chemicals, molecular docking, drug-likeness, toxicity, and molecular dynamics were used to evaluate and analyse their anti-breast cancer activity. Five substances, 2,3-Diphenyl quinoxaline, 17–Acetoxy pregnolone, Benzyl–d-glucoside, Ergostenol acetate, and Stigmast-7-en-3-ol, shown higher binding affinity than Tamoxifen, signaling their potential use in breast cancer treatment.

Keywords: Molecular docking, Toxicity study, Molecular dynamics, ADME study, Drug target prediction

Introduction

Breast cancer is the commonest cause of cancer death in women worldwide. Rates vary by around five times globally, although they are rising in areas where the disease was previously under-represented (Harbeck et al. 2019). Estrogens have been associated with a number of the identified risk factors. According to reports, developed nations account for about 25% of breast cancer patients. One of the common cancers, accounting for more than 27% of all cancer patients in India, is breast cancer. The national average for cancer cases in India is 100.4 per 100,000 for 2022, with breast cancer being detected in many women (105.4 per 100,000). There will be 287,850 new cases of invasive breast cancer and 51,400 new cases of DCIS in the United States, respectively. In urban regions, there was one instance of breast cancer reported for every 22 women, and for every 60 women in rural areas. Males have, however, only sporadically been known to have breast cancer. Each year, more than 1500 new cases are reported in the United States (Łukasiewicz et al. 2021).

Although there have been various reports of chemotherapeutics acting against breast cancer but each of them faces imminent threat of toxicity and multidrug resistance. So, to combat these problems, exploration of vast array of biomolecules from natural origin can be an option. Lagenaria siceraria is a very common plant that has received few reports of its ability to combat cancer. The L. siceraria (Molina) Standley syn. (Family: Cucurbitaceae) plant, also known as the bottle gourd or calabash, is a wonderful fruit found in nature that contains all the necessary nutrients for human health. It has a long history of usage as a diuretic, purgative, general tonic, aphrodisiac, and cardioprotective agent (Sakthivel et al., 2022; Saeed et al. 2022). Various literature studies have shown anti-cancer effects of L. siceraria. The experiment described focuses on ligand preparation and optimization for breast cancer receptor targeting using L. siceraria leaf-derived compounds. The ligands were prepared and analyzed using various computational methods, including molecular docking, drug target prediction, toxicity prediction, and molecular dynamics simulation.

Methodology

Extraction method

By using the soxhlation procedure, the aerial components of the L. siceraria were extracted. The aerial components were dried by employing the shade drying technique. For 72 h, shade drying was done in the open air with a temperature of 25 °C as the ambient temperature. The aerial components were manually milled into a coarse powder after being broken up into small bits. For the extraction, 200 g of L. siceraria aerial parts powder was combined with 1200 ml of 100% methanol (Merck, Mumbai, India). The combination was filtered, and the filtrate was concentrated using a rotary evaporator at 45 to 50 °C. The filtrate and concentrated filtrate were then combined, and the resulting residue was stored in a refrigerator until further use (Mondal et al. 2023).

Ligands preparation and optimization

As reported by Mondal et al., all the ligands (34) from L. siceraria leaf detected using GCMS (performed on GCMS-QP 2010 plus single quadrupole gas chromatograph-mass spectrometer), were drawn in Chem Draw Professional 15.0 (Fig. 1) (Mondal et al. 2023). Three-dimensional structures of the ligands were created in Open Babel and saved in SDF format for further preparation and molecular docking analysis (Sarkar et al. 2022; Rahman et al. 2022).

Fig. 1.

Phytochemical ligands from L. siceraria

Drug like properties of the ligands

The bioavailability score, Ghose’s rule, Veber’s rule, and Lipinski’s rule of five were all used to determine the cutoff values for the physicochemical attributes of all the ligands. The MW (molecular weight), HBD (hydrogen bond donor), HBA (hydrogen bond acceptor), log P (lipophilicity log), and log S (aqueous solubility log) molecular characteristics were used to calculate drug likeness. The parameters were generated using the SWISSADME server (www.swissadme.ch/index.php) (Samajdar 2023; Ogunlakin et al. 2023).

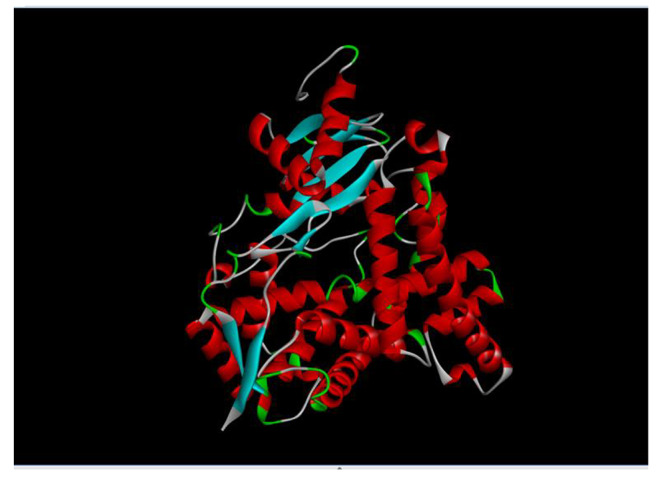

Preparation and optimization of breast cancer receptor

The crystallographic structures of the aromatase inhibitor protein (Fig. 2), which targets breast cancer (PDB ID: 3EQM), were made available via the protein data bank. The water molecules were removed from the protein to get it ready for molecular docking, and then hydrogen atoms were added using the BIOVIA Discovery Studio 2021 Client application to fix the ionization of the amino acid residues (Ayar et al. 2022; Pattar et al. 2020).

Fig. 2.

Structure of 3EQM protein

Molecular docking analyses and visualization

The PyRx application was used to perform molecular docking using the Auto dock Vina tool once the proteins were saved in .pdb format and loaded. The PyPx stable was used to determine which conformer was the most stable. A grid dimension of 57.02 Å x 66.94 Å x 51.40 Å was chosen for the experiment. The intermolecular interactions between the ligands obtained from L. siceraria and 3EQM protein were identified and visualized using the Discovery Studio 2021 Client software (Apeh et al., 2020).

Prediction of drug target

The top scoring ligands were subjected to drug target prediction using PASS online software (http://www.way2drug.com/passonline/predict.php). The PASS (prediction of activity spectra for substances) software product, which predicts more than 300 pharmacological effects and biochemical mechanisms on the basis of the structural formula of a substance, may be efficiently used to find new targets (mechanisms) for some ligands and, conversely, to reveal new ligands for some biological targets (Mahmud et al. 2022; Al-Madhagi et al. 2022).

Toxicity prediction

The top-scoring ligands were subjected to toxicity prediction using ProTox II software in human cells (https://tox-new.charite.de/protox_II/). The webserver takes a two-dimensional chemical structure as input and reports the possible toxicity profile of the chemical for 34 models with confidence scores (Banerjee et al. 2018; Chaudhari et al. 2022).

Molecular dynamics simulation

The top-scoring natural ligands was put through a 500 ns MD simulation using the GROMOS96 43a1 force field and GROMACS software in order to examine the stability and interactions of the ligand-receptor complexes. MD simulations were used to study structural parameters such as the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) for complex stability (Patil et al. 2022; Bodas et al. 2022).

Results

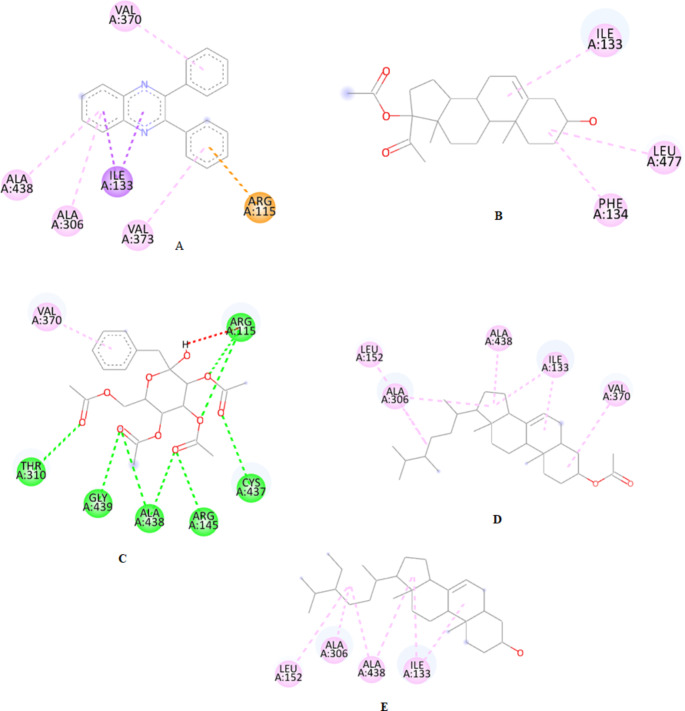

PyRx docking was utilized to ascertain the binding affinities and significant interactions between L. siceraria-derived phytochemical ligands and the breast cancer receptor-targeting aromatase inhibitor protein (3EQM). The binding affinities of the acquired ligands and the standard breast cancer treatment Tamoxifen were evaluated. Table 1 shows the binding affinity obtained from the protein bound ligands and the standard drug Tamoxifen (Samajdar 2022; De et al. 2023). The binding affinity of the L. siceraria ranged from − 9.4 to -4.2 kcal/mol. The molecular interactions between the most active ligands and the active site of the breast cancer receptor-targeting aromatase inhibitor protein were visualized using the Discovery Studio 2021 Client program (Fig. 3). These samples showed the expected interactions with the protein’s active-region amino acids, indicating strong antagonistic characteristics against the aromatase inhibitor protein, which attacks the breast cancer receptor. For the protein coded 3EQM, Stigmast-7-en-3-ol had the highest binding affinity of -9.4 kcal/mol followed by Ergostenol acetate (-9.3 kcal/mol) and 2, 3 Diphenyl Qunoxaline (-8.9 kcal/mol) (Ahmed et al., 2016). The ligand with values lowest binding affinity was observed in Glyceraldehyde (-4.2 kcal/mol). As compared to the commonly used aromatase inhibitor drug Tamoxifen (-8.0 kcal/mol), the binding affinities of five natural compounds (Stigmast-7-en-3-ol, Ergostenol acetate, 2,3 Diphenyl Qunoxaline, 17-α-Acetoxy pregnolone, Benzyl-β-d- glucoside) derived from L. siceraria were found to be higher indicating their future usage in inhibition of breast cancer. The 3D figure of the top scoring is also presented (Fig. 4.). These ligands were further studied for their receptor target prediction, toxicity studies and molecular dynamics studies (Subbaiyan et al. 2020; Pattar et al. 2020).

Table 1.

Results of Ligands docking in aromatase inhibitor target

| Ligands | Binding Affinity (cΔG in kcal/mol) |

|---|---|

| 3EQM | |

| Stigmast-7-en-3-ol | -9.4 |

| Ergostenol acetate | -9.3 |

| 2,3 Diphenyl quinoxaline | -8.9 |

| 17-α-Acetoxy pregnolone | -8.6 |

| Benzyl-β-d- glucoside | -8.4 |

| Ergosta-5,7,22-trien-3-ol | -8.0 |

| Tamoxifene | -8.0 |

| 3D, 7D, 11D Phytanic acid | -6.7 |

| Pentadecanoic acid | -6.2 |

| Phytol | -6.2 |

| 7,10,13-Hexadecanetrienal | -6.2 |

| Pentadecanoic acid | -6.1 |

| 13 Docosenamide | -5.9 |

| Dibenzofuran | -5.9 |

| Heptaecanoic acid | -5.9 |

| Octadecanoic acid | -5.9 |

| Tetradecanoic acid | -5.9 |

| Octadecanamide | -5.9 |

| α-Terpineol | -5.7 |

| Nerol | -5.7 |

| Pentacosanol | -5.7 |

| Glutamine | -5.6 |

| 1,3,5-Triazine-2,4,6-triamine | -5.6 |

| 9-Tetradecenal | -5.5 |

| Hexadecanamide | -5.4 |

| Benzimidazole | -5.4 |

| 4 H-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro | -5.3 |

| 1,2,3-Propandioldiacetate | -5.1 |

| Ribitol | -5.1 |

| 3-Methyl-5-propylnonane | -5.0 |

| 1,2-Cyclopentanedione | -4.8 |

| Glycerine | -4.4 |

| 2-Methyl Propanoic acid | -4.4 |

| Glyceraldehyde | -4.2 |

Fig. 3.

Molecular interaction of 3EQM and (A) 2,3-Diphenyl quinoxaline (B) 17-α-Acetoxy pregnolone (C) Benzyl-β-d- glucoside (D) Ergostenol acetate (E) Stigmast-7-en-3-ol

Fig. 4.

3D structure of (A) 2,3-Diphenyl quinoxaline (B) 17-α-Acetoxy pregnolone (C) Benzyl-β-d- glucoside (D) Ergostenol acetate (E) Stigmast-7-en-3-ol

The ligands’ molecular weights from SwissADME varied from 90.08 to 414.71 g, and their LogP values ranged from 0.23 to 6.73, indicating their lipophilicity. The predicted values of all ligand sets were within the range of Lipinski’s rule of five cutoffs. This is due to the fact that all ligands exhibit drug-like qualities that meet Ghosh’s rule requirement and that compounds with log P values in this range are soluble in fats, oils, lipids, and nonpolar solvents (Table 2). Virtual phytochemicals from L. siceraria have been examined utilizing molecular docking scores and ADME data, and the results imply that they may be 3EQM protein inhibitors (Awadelkareem et al. 2022). The drug target prediction using top scoring ligands showing all five of them is hiving aromatase inhibition properties (Dash et al. 2020; Al-Madhagi et al. 2022) (Table 3). The same set of ligands were studied for their toxicity using ProTox II software showed that Stigmast-7-en-3-ol, Ergostenol acetate, 2,3 Diphenyl quinoxaline, 17-α-Acetoxy pregnolone, Benzyl-β-d- glucoside had a predicted class 4 to class 6 toxicity with higher LD50 values indicating their safe usage in human. The root mean square deviation (RMSD) values of the best four ligands from L. siceraria in association with the protein 3EQM are shown in Fig. 5 (Banerjee and Ulker 2022). The stability of each simulated model was assessed using calculations of the backbone atom RMSD for the ligand-protein combination shown in the picture. The most popular quantitative method for comparing the similarity of two protein structures that are superimposed (the reference and target structures) is the RMSD. It tracks changes in the separation of atoms in two stacked configurations. The RMSD of A (2,3-Diphenyl quinoxaline) rises until 350 ns, then stabilizes at 0.9 Å and 400 ns, while D (Benzyl-β-d- glucoside), shows steady rise until 300 ns, then stabilize at 0.8–0.9 Å until 350 ps and E (Stigmast-7-en-3-ol) shows a very similar trend as D. This demonstrates that these ligands do not alter their orientation in the active site of proteins and stay stable inside the pocket. The ligand B (17-α-Acetoxy pregnolone) were stable about 0.6 Å with a sharp rise to 1.4 Å at 250 ns. However, C (Ergostenol acetate) showed higher RMSD and maintained at 0.8 Å with a sharp rise to 1.2 Å at 400 ns, which directly resembles to the charge analyses. The 3EQM-top ligand complex showed the best stability as seen with the least total and average RMSD and the highest number of peaks within the 0.6 to 0.8 Å range (greatest left shift). (Qazi and Raza 2021; Rowaiye et al. 2022).

Table 2.

ADME parameters for each ligand from SwissADME

| Molecule | MW | MLOGP | #H-bond acceptors | #H-bond donors | Lipinski #violations | Ghose #violations | Veber #violations | Ali Solubility (mol/l) | Ali Log S | GI absorption |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2-Methyl Propanoic acid | 102.13 | 0.89 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4.93E-02 | -1.31 | High |

| Glyceraldehyde | 90.08 | 1.66 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 7.59E + 00 | 0.88 | High |

| 1,2-Cyclopentanedione | 98.1 | 0.42 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1.44E + 00 | 0.16 | High |

| Glycerin | 92.09 | 1.51 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 1.00E + 01 | 1 | High |

| 1,3,5-Triazine-2,4,6-triamine | 126.12 | 2.73 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2.62E-01 | -0.58 | High |

| 4 H-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl | 144.13 | 1.77 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2.70E-01 | -0.57 | High |

| Glutamine | 146.14 | 3.58 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3.04E + 01 | 1.48 | High |

| Alpha-Terpineol | 154.25 | 2.3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3.21E-04 | -3.49 | High |

| 2,3-Dihydrobenzofuran | 120.15 | 1.75 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1.08E-02 | -1.97 | High |

| 1,2,3-Propanetriol diacetate | 176.17 | 0.23 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1.78E-01 | -0.75 | High |

| Nerol | 154.25 | 2.59 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2.14E-04 | -3.67 | High |

| 3-Methyl-5-propylnonane | 184.36 | 5.67 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3.29E-07 | -6.48 | Low |

| Benzimidazole | 118.14 | 0.98 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 9.30E-03 | -2.03 | High |

| Ribitol | 152.15 | 2.33 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 7.91E + 00 | 0.9 | Low |

| Tetradecanoic acid | 210.36 | 3.7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7.25E-06 | -5.14 | High |

| Pentadecanoic acid | 234.38 | 4.01 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.45E-05 | -4.84 | High |

| 3D,7D,11D-Phytanic acid | 296.53 | 5.25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3.35E-09 | -8.47 | Low |

| 9-Tetradecenal | 284.48 | 4.67 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.33E-09 | -8.87 | High |

| 7,10,13-Hexadecatrienal | 255.44 | 3.79 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6.00E-08 | -7.22 | High |

| Heptadecanoic acid | 438.43 | 0.76 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.53E-04 | -3.34 | High |

| Phytol | 283.49 | 4.27 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4.77E-09 | -8.32 | High |

| Octadecanoic acid | 282.34 | 3.59 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7.14E-06 | -5.15 | High |

| Hexadecanamide | 337.58 | 5.06 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.09E-10 | -9.96 | Low |

| Benzyl beta-d-glucoside | 368.68 | 6.47 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3.82E-13 | -12.42 | Low |

| Octadecanamide | 438.69 | 6.51 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 3.93E-09 | -8.41 | Low |

| 2,3-Diphenylquinoxaline | 442.72 | 6.7 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2.77E-10 | -9.56 | Low |

| Stigmasta-7,25-dien-3-ol | 412.69 | 6.62 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4.72E-10 | -9.33 | Low |

| gamma-Ergostenol acetate | 414.71 | 6.73 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4.00E-10 | -9.4 | Low |

| 17-alpha-Acetoxypregnenolone | 374.51 | 3.46 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.02E-05 | -4.7 | High |

Table 3.

Predicted target receptors for top scoring ligands

| Top scoring ligands | Target receptors |

|---|---|

| 2,3-Diphenyl quinoxaline |

Androgen antagonist Menopausal disorders treatment Aromatase receptor Estradiol 17alpha-dehydrogenase inhibitor Estrogen agonist |

| 17-α-Acetoxy pregnolone |

Aromatase receptor Antihypercholesterolemic Adenomatous polyposis treatment Caspase 3 stimulant Glyceryl-ether monooxygenase inhibitor |

| Benzyl-β-d- glucoside |

Cholesterol antagonist Alkylacetylglycerophosphatase inhibitor Alcohol O-acetyltransferase inhibitor Steroid synthesis inhibitor Aromatase receptor |

| Ergostenol acetate |

Thioredoxin reductase inhibitor Formaldehyde dehydrogenase (glutathione) inhibitor Aromatase receptor Plasmanylethanolamine desaturase inhibitor Lactose synthase inhibitor |

| Stigmast-7-en-3-ol |

Interleukin 1a antagonist 2-Enoate reductase inhibitor Angiogenesis stimulant Aromatase receptor Mannan endo-1,4-beta-mannosidase inhibitor |

Fig. 5.

RMSD plot during molecular dynamics simulations of (A) 2,3-Diphenyl quinoxaline (B) 17-α-Acetoxy pregnolone (C) Benzyl-β-d- glucoside (D) Ergostenol acetate (E) Stigmast-7-en-3-ol

Conclusions

In conclusion, our finding suggests, five natural ligands 2,3-Diphenyl quinoxaline, 17-Acetoxy pregnolone, Benzyl- β -d-glucoside, Ergostenol acetate, and Stigmast-7-en-3-ol obtained from L. siceraria had significant in silico anti-breast cancer activity with dock score ranging between (-8.1 Kcal/mol to -9.4 Kcal/mol) as compared to standard Tamoxifen (-8.0 Kcal/mol) in aromatase receptor protein PDB ID: 3EQM. Additionally, an ADME study, target prediction study, and molecular dynamics study were also carried out for these ligands to establish the optimal drug-likeness profile. Toxicity prediction indicated safe usage of these ligands. This information might serve as a starting point for more research into the creation of a cure for breast cancer and save humanity from the spread of deadly disease.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Department of Pharmaceutical Technology, Brainware University, for providing inspiration for the research.

Abbreviations

- MD

Molecular Dynamics

- ADME

Absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion

- RMSD

Root mean square division

- GCMS

Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry

- DCIS

Ductal carcinoma in situ

Author contributions

SS performed the interpretation and writing of manuscript. PM provided the GCMS analysis and structural elucidation of the phytochemicals. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ahmed B, Ashfaq UA, ul Qamar MT, Ahmad M. Anti-cancer potential of phytochemicals against breast cancer: molecular docking and simulation approach. Bangladesh J Pharmacol. 2016;9(4):545–550. doi: 10.3329/bjp.v9i4.20412. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Madhagi WM, Alzomor AK, Zamakshshari NH, Mubarak MA. Formulation and in-silico study of meclizine ointment as anti-eczema. In Silico Pharmacol. 2022;30(1):15. doi: 10.1007/s40203-022-00129-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apeh VO, Asogwa E, Chukwuma FI, Okonkwo OF, Nwora F, Uke R (2020) Chemical analysis and in silico anticancer and anti-inflammatory potentials of bioactive compounds from Moringa oleifera seed oil. Adv trad med, 1–16

- Awadelkareem AM, Al-Shammari E, Elkhalifa AE, Adnan M, Siddiqui AJ, Snoussi M, Khan MI, Azad ZA, Patel M, Ashraf SA. Phytochemical and in silico adme/tox analysis of Eruca sativa extract with antioxidant, antibacterial and anticancer potential against caco-2 and HCT-116 colorectal carcinoma cell lines. Molecules. 2022;27(4):1409. doi: 10.3390/molecules27041409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayar A, Aksahin M, Mesci S, Yazgan B, Gül M, Yıldırım T. Antioxidant, cytotoxic activity and pharmacokinetic studies by Swiss Adme, Molinspiration, Osiris and DFT of PhTAD-substituted dihydropyrrole derivatives. Curr Comput. 2022;18(1):52–63. doi: 10.2174/1573409917666210223105722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee P, Ulker OC. Combinative ex vivo studies and in silico models ProTox-II for investigating the toxicity of chemicals used mainly in cosmetic products. Toxicol Mech methods. 2022;32(7):542–548. doi: 10.1080/15376516.2022.2053623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee P, Eckert AO, Schrey AK, Preissner R. ProTox-II: a webserver for the prediction of toxicity of chemicals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(W1):W257–W263. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodas KS, Bagul CD, Shinde VM. Evaluation of wound healing effect of Mallotus philippensis (Lam.) Mull. Arg. By in silico multitargets directed for multiligand approach. In Silico Pharmacol. 2022;10(1):19. doi: 10.1007/s40203-022-00134-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhari B, Patel H, Thakar S, Ahmad I, Bansode D. Optimizing the Sunitinib for cardio-toxicity and thyro-toxicity by scaffold hopping approach. In Silico Pharmacol. 2022;10(1):10. doi: 10.1007/s40203-022-00125-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dash L, Sharma N, Vyas M, Kumar R, Kumar R, et al. Prediction of anticancer activity of potential anticancer compounds using pass online software. Plant Arch. 2020;20(2):2808–2813. [Google Scholar]

- De A, Bhattacharya S, Debroy B, Bhattacharya A, Pal K. Exploring the pharmacological aspects of natural phytochemicals against SARS-CoV-2 Nsp14 through an in silico approach. In Silico Pharmacol. 2023;11(1):12. doi: 10.1007/s40203-023-00143-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbeck N, Penault-Llorca F, Cortes J, Gnant M, Houssami N, Poortmans P, Ruddy K, Tsang J, Cardoso F. Cardoso. Breast cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:66. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Łukasiewicz S, Czeczelewski M, Forma A, Baj J, Sitarz R, Stanisławek A. Breast cancer—epidemiology, risk factors, classification, prognostic markers, and current treatment strategies—an updated review. Cancers. 2021;13(17):4287. doi: 10.3390/cancers13174287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmud S, Paul GK, Biswas S, Kazi T, Mahbub S, Mita MA, Afrose S, Islam A, Ahaduzzaman S, Hasan MR, Shimu MS (2022) phytochemdb: a platform for virtual screening and computer-aided drug designing. Database, 2022, baac002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mondal P, Sarkar A, Dutta S, Khamkat P, Barik V, Mondal S (2023) GCMS Analysis and Assessment of the Anthelmintic Potential of the Arial Parts of the Common Indian Vegetative Plant Lagenaria Siceraria (Molina) Standley (LS). Int. J. Pharm. Investig, 2023;13(3)

- Ogunlakin AD, Onifade TR, Gyebi GA, Obafemi BA, Ojo OA (2023) In silico pharmacology and bioavailability of bioactive constituents from Triclisia subcordata (Oliv), an underutilized medicinal plant in Nigeria. Plant Sci Today. 20

- Patil PH, Birangal S, Shenoy GG, Rao M, Kadari S, Wankhede A, Rastogi H, Sharma T, Pinjari J, Puralae Channabasavaiah J. Molecular dynamics simulation and in vitro evaluation of herb–drug interactions involving dietary polyphenols and CDK inhibitors in breast cancer chemotherapy. Phytother Res. 2022;36(10):3988–4001. doi: 10.1002/ptr.7547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattar SV, Adhoni SA, Kamanavalli CM, Kumbar SS. In silico molecular docking studies and MM/GBSA analysis of coumarin-carbonodithioate hybrid derivatives divulge the anticancer potential against breast cancer. Beni-Suef univ j basic appl sci. 2020;9(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s43088-020-00059-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qazi S, Raza K. Phytochemicals from ayurvedic plants as potential medicaments for ovarian cancer: an in-silico analysis. J Mol Model. 2021;27:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s00894-021-04736-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman MA, Shorobi FM, Uddin MN, Saha S, Hossain MA. Quercetin attenuates viral infections by interacting with target proteins and linked genes in chemicobiological models. In Silico Pharmacol. 2022;16(1):17. doi: 10.1007/s40203-022-00132-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowaiye AB, Ogugua AJ, Ibeanu G, Bur D, Asala MT, Ogbeide OB, Abraham EO, Usman HB. Identifying potential natural inhibitors of Brucella melitensis Methionyl-tRNA synthetase through an in-silico approach. PLOS Neglected Trop Dis. 2022;16(3):e0009799. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0009799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed M, Khan MS, Amir K, Bi JB, Asif M, Madni A, Kamboh AA, Manzoor Z, Younas U, Chao S (2022) Lagenaria siceraria fruit: a review of its phytochemistry, pharmacology, and promising traditional uses. Front Nutr 9. 10.3389/fnut.2022.927361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sakthivel S, Dhanapal AR, Balakrishnan E, Selvapitchai S. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of bottle gourd (Lagenaria siceraria): impact of organic liquid fertilizer. Energy Nexus. 2022;5:100055. doi: 10.1016/j.nexus.2022.100055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Samajdar S. Structure based molecular docking analysis for selected phytochemicals from Murraya koenigii targeting aromatase receptor against breast cancer. Indian J Sci. 2022;13(75):49605–49611. [Google Scholar]

- Samajdar S. In silico ADME prediction of Phytochemicals present in Piper longum. Asian J Pharm. 2023;13(2):89–93. doi: 10.52711/2231-5659.2023.00017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar A, Agarwal R, Bandyopadhyay B. Molecular docking studies of phytochemicals from Terminalia chebula for identification of potential multi-target inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 proteins. J Ayurveda Integr Med. 2022;13(2):100557. doi: 10.1016/j.jaim.2022.100557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbaiyan A, Ravichandran K, Singh SV, Sankar M, Thomas P, Dhama K, Malik YS, Singh RK, Chaudhuri P. In silico molecular docking analysis targeting SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and selected herbal constituents. J Pure Appl Microbiol. 2020;14(Suppl 1):989–998. doi: 10.22207/JPAM.14.SPL1.37. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.