Abstract

Oral health is crucial for health-related quality of life. However, the research on the factors affecting oral health status is not comprehensive enough. This investigation aimed to evaluate the multifaceted determinants of college students’ oral health status and explore the impact of social support, oral health literacy, attitudes, behaviors, and self-efficacy on OHRQoL. By surveying 822 students from a university. Baseline data included sociodemographics (gender, age), social support (MSPSS scale), oral health self-efficacy (SESS scale), oral health knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP questionnaire), and OHRQoL (OHIP-14 scale). Based on social cognitive theory, partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) and fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) were used to examine the relationship between the study variables. PLS-SEM results showed that knowledge, attitude, and practice predicted OHRQoL through self-efficacy. FsQCA results showed that the combination of different variables was sufficient to explain OHRQoL. The conclusion was that self-efficacy plays an important role and the combination of high-level knowledge, positive attitudes, and strong self-efficacy was important in improving OHRQoL. The results of this study provided a reference for the oral health strategy planning of college students in China.

Subject terms: Health care, Health occupations

Introduction

Oral diseases not only have adverse effects on physical, social, and mental health but also limit individual development1. A large proportion of the population will face oral and dental-related problems in daily life2. The high rate of dental caries3, the high proportion of orthodontic3 and restorative care3 and the low use of oral-health education in adolescence stage4 reflect the fact that college students have very specific oral health needs. Although college students have a positive attitude toward the prevention of dental caries and periodontal disease, their understanding of oral diseases is not comprehensive enough5. Bad practice formed during adolescence may lead to poor oral health6. In addition, poor diet, eating disorders, and other psychosocial problems also affect the oral health3. Oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) is a multidimensional paradigm involving the subjective evaluation of an individual's oral health, functional health, emotional health, expectations and satisfaction with care, and self-awareness7. These affect the oral health-related quality of life. Therefore, exploring the influencing factors of their oral health status has a positive practical significance to improve the OHRQoL.

The factors that affect the OHRQoL are multiple and complex. Health is defined as physical, psychological and social well-being8, that is, a healthy bio-psycho-social model, physical function, emotional factors, and social factors will affect individual health9. OHRQoL has been used to assess oral health, emotion, and self-esteem to understand the interaction between social factors, environmental factors, physical function, and oral health7. From the perspective of biomedical and psychological aspects10, some studies have confirmed that psychosocial factors, oral health knowledge, attitudes, practice, and other factors affect oral health to varying degrees11–13. Thus, the role and function of oral health knowledge, attitudes, practices, self-efficacy and social support in the OHRQoL need to be investigated.

The Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice (KAP) theory is a theoretical model that changes human health-related behavior14. The model mainly originated from social learning theory and innovation diffusion theory15. Studies have shown that oral health knowledge, attitudes, and practice all affect oral health quality13. Oral health knowledge has a direct and positive impact on attitudes, and knowledge indirectly affects practice through attitudes13. In addition, when individuals hold positive attitudes, they are more motivated to implement practice and obtain better results16. In previous multidimensional studies, self-efficacy was considered a predictive factor for oral health status17,18. The formation of self-efficacy is a long process19, mainly derived from an individual's own performance, imitation by others, persuasive language, and emotions related to behavior20. Studies have shown that oral health knowledge can change students' oral health practice and self-efficacy21. And higher self-efficacy is related to better oral health practice and gingival health22.

Social support can convey the basic facts, knowledge, and information that affect emotions, as well as influence an individual's cognitive responses and emotional, behavioral, and health beliefs23. Research shows that support from family and friends has a positive impact on adolescent health-related behavior20. Children with a lower socio-economic status and poor oral care practice have lower OHRQoL and good oral health practice have a positive impact on OHRQoL12. At the same time, parents’ own oral health practice will also affect the oral health of the next generation, which shows that social support has a certain impact on children’s oral health13. Knowledge can play a mediating role between social support and self-efficacy in the study of pediatric osteoporosis24. Researchers found that older adults with adequate social support had greater access to resources, changed attitudes, and reduced risk of depression25. In addition, there is a relationship between low social support and individual depression21. The maintenance or change of an individual's health practice is also influenced by social support22. Strengthening individual, family, and social resources, as well as individual autonomous coping with health risks and damage, plays an important role in maintaining health of adolescents26. Therefore, social support can change an individual's OHRQoL through self-efficacy and health knowledge, attitudes, practice.

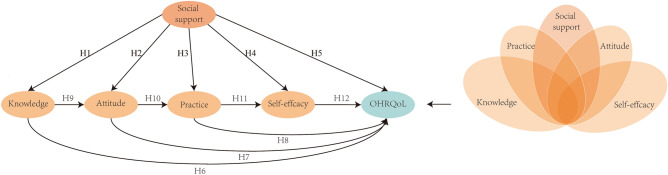

Historically, most studies on health-related knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors have focused on evaluating different populations or fields, such as the oral health status of rural children27 or the hepatitis prevention status of medical students28. Few studies on the relationship between knowledge, attitudes, and habits related to oral health and OHRQoL of university students. In addition, previous studies have indicated that social support29, health-related behavior13, and self-efficacy30 can directly affect OHRQoL, but these studies focused on investing single causal and linear relationships. Facing with the many complex factors that affect OHRQoL, these studies produced contradictory conclusions. For instance, while some studies have shown that mother’s oral health knowledge is associated with children’s oral health31, others have demonstrated that while a mother’s knowledge alone may not have a direct impact on children's sound dentition when coupled with a mother’s attitudes, it can produce children's sound dentition an additive effect32. The other study shown that some vulnerable social groups in Hong Kong are supported by family members, but the incidence of dental caries is still very high14. Therefore, the complex relationship between these factors and OHRQoL has not been fully elucidated. It is necessary to use different methods to study the complex causal relationships between multiple variables that affect oral health. In this study, we use the partial least squares structural equation model (PLS-SEM) to determine the linear (symmetric) causal relationship between influencing factors and OHRQoL, and the fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) to determine the nonlinear (asymmetric), heterogeneity, and dynamic interaction between predictive factors and results. As shown in the hypothetical model (Fig. 1), we endorsed the methodologically wiser approaches that combine both analytical techniques for the outcome of interest. Thus, this study was conducted to understand and investigate these complex factors affecting the OHRQoL of college students. The results provide the oral health of college students with a nuanced understanding of the complex causality and trade-off between antecedent factors, helping them devise effective healthy strategies.

Figure 1.

Partial least square structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) and fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) hypothetical model.

Materials and methods

Study design and sampling procedures

The study was conducted at a university in Zhejiang Province, China. Baseline data included demographics (gender, age), social support, oral health knowledge, attitudes, practice, self-efficacy and assessed subjects' OHRQoL.

The final sample size was 822 college students, who volunteered to participate in the study. The final sample size was 822 people who volunteered to participate in the study. The inclusion criteria are as follows: (1) there are no reading and comprehension disorders; (2) college students. The exclusion criteria are as follows: (1) incomplete data; (2) mental illness; and (3) reluctance to participate after explaining the study. Because of the nature of the study, the questionnaire is anonymous and protected.

Conceptual framework

The hypothetical framework of this study is proposed according to previous literature (Fig. 1). At the same time, the following verified tools were selected and adapted for this study (Supplementary table 1). The questionnaire was translated into Chinese and discussed with experts.

Variables

Social support

Using the dimension of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS33,) as an indicator, social support is a potential variable34. The scale was used to measure the social support of family, friends, and partners. The original scale is a scale containing 30 questions, which is simplified to 6 questions in this study. The item was answered on a Likert five-point scale, ranging from “1: Strongly disagree” to “5: Strongly agree”. The total score is obtained by adding up the scores of the items and ranges from 6 to 30. The higher the score, the better the social support the subjects received.

Self-efficacy

Using the dimension of the oral health care self-efficacy scale (SESS35,) as an index, self-efficacy is the decisive factor affecting the compliance of patients with chronic diseases36. The scale was used to measure the degree of self-efficacy in consulting a dentist, cleaning teeth, and eating practice. The original scale is a scale containing 15 questions, which is simplified to 14 questions in this study. A Likert five-point scale was used, ranging from “1: Strongly disagree” to “5: Strongly agree”. The total score is obtained by adding up the scores of the items and ranges from 14 to 70. The higher the score, the higher the oral self-efficacy the subjects received.

Oral health knowledge, attitudes, practice

The knowledge, attitudes, and practice of college students were assessed according to the questions used in the oral health knowledge, attitudes, practice (KAP) questionnaire37. The original scale is a scale containing 21 questions, which is simplified to 18 questions in this study. The item was answered with the Likert five-point scale, ranging from “1: Strongly disagree” to “5: Strongly agree”. The total score is obtained by adding up the scores of each item. The higher the score, the better the oral knowledge, attitude, and practice the subjects received.

Oral health-related quality of life

The scale evaluates the quality of life related to oral health, and it has good psychometric characteristics38. The original scale is a scale containing 21 questions. According to the Likert five-point scale, respondents’ responses were “very often = 4”, “often = 3”, “occasionally = 2”, “almost never = 1” or “never = 0”. The total score is obtained by adding up the scores of the items and ranges from 0 to 56. The higher the overall score of OHIP-14, the lower the OHRQoL13.

Data analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and Cronbach's alpha were used to verify the validity and reliability of the questionnaire. To test the hypothesis, this work proposes a conceptual model that includes dimensions that may affect oral-related health. PLS-SEM (V.3.2.9)39 was used to analyze the external and internal models to explore the influence of various factors. Each path of the internal model is calculated and evaluated by using a bootstrapping program (the original dataset was 5000 subsamples); and the standard error, T value, and p-value are calculated. The fsQCA 3.040 software package was used to perform fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis. It can be used to test causal and independent variables, and how combining variables leads to the same results as dependent variables.

After checking for missing data, all values between 0 and 1 were then recalibrated. When only two values are considered, 0 (not featured) and 1 (featured) were used. The following thresholds are considered together with continuous variables: 5%, 50%, and 95%41, and analysis is performed after the response is changed. FsQCA analysis provides three possible solutions (complex, minimalist, and intermediate solutions). According to the suggestion of the literature40,42, we adopted the latter.

Informed consent

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Zhejiang Shuren University (NO: 202201017). Informed consent information was included with each questionnaire and introduced before the surveys. Surveys were only conducted if subjects were fully informed of the content and aim of this research project and agreed to participate.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Data collection and analysis were carried out from May to September 2022. Results Questionnaires were sent to 822 students, of which 41 were returned, a response rate of 95.01%. The average age of the respondents was 19.14 years old (SD = 1.01), the range was 17–23 years old, and the proportion of women was 74.20%43 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participants’ demographic characteristics. (N = 822).

| Variable | Category | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 201 | 25.70 |

| Female | 580 | 74.20 | |

| Age | 17–19 | 676 | 86.56 |

| 20–23 | 105 | 13.44 |

Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM)

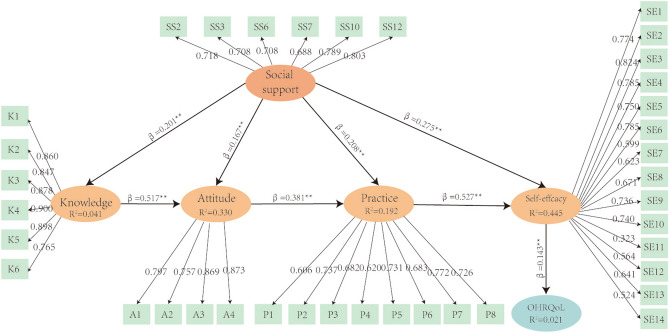

Supplementary table 1 illustrates the indicators used by the external model. For all variables, the factor loading range obtained was typically greater than 0.544; and the consistent reliability coefficient of Cronbach's alpha (CA) is always > 0.745, indicating that the internal reliability of its dimension is acceptable. The average variance extraction (AVE) of these dimensions is > 0.5, indicating the effectiveness of convergence44. Table 2 determines the importance of each relationship and its impact on the internal model. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant46. Specifically, it confirmed the positive effects of various variables (social support, self-efficacy, oral health knowledge, attitudes, practice) on OHRQoL, in which self-efficacy played an intermediary role (Fig. 2). The blindfold procedure show that Q2 is > 0, confirming the predictive relevance of the study model47. The SRMR is 0.071. When the SRMR value is less than 0.08, the model fits well48.

Table 2.

PLS-SEM: inner model.

| Relationship | Standardized beta | Mean | Standard deviation | T-value | P | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social support—> Knowledge | 0.201 | 0.203 | 0.037 | 5.457 | < 0.001 | H1 is supported |

| Social support—> Attitude | 0.167 | 0.167 | 0.033 | 5.041 | < 0.001 | H2 is supported |

| Social support—> Practice | 0.208 | 0.209 | 0.040 | 5.149 | < 0.001 | H3 is supported |

| Social support—> Self-efficacy | 0.275 | 0.276 | 0.034 | 8.078 | < 0.001 | H4 is supported |

| Knowledge—> Attitude | 0.517 | 0.518 | 0.038 | 13.501 | < 0.001 | H9 is supported |

| Attitude—> Practice | 0.381 | 0.382 | 0.035 | 10.929 | < 0.001 | H10 is supported |

| Practice—> Self-efficacy | 0.527 | 0.528 | 0.031 | 17.261 | < 0.001 | H11 is supported |

| Self- efficacy—> OHRQoL | 0.143 | 0.143 | 0.031 | 3.784 | < 0.001 | H12 is supported |

Figure 2.

Path model and PLS-SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; SS: Social support; SE self-effcacy, K knowledge, A attitude, P practice.

Fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA)

Necessity analysis

According to the results of the necessity analysis (Table 3), because all the consistency values are below 0.9049, no single factor is a necessary condition for oral health.

Table 3.

Necessity analysis for oral health related quality of life (OHRQoL).

| High OHRQoL | Low OHRQoL | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cons | Cov | Cons | Cov | |

| Social support | 0.658256 | 0.67243 | 0.652649 | 0.554267 |

| ~ Social support | 0.563664 | 0.661239 | 0.61429 | 0.5991 |

| Self-efficacy | 0.626318 | 0.709655 | 0.569836 | 0.536772 |

| ~ Self-efficacy | 0.59117 | 0.623079 | 0.691771 | 0.60615 |

| Knowledge | 0.686512 | 0.694854 | 0.625713 | 0.526511 |

| ~ Knowledge | 0.532196 | 0.631041 | 0.637362 | 0.628289 |

| Attitude | 0.75653 | 0.661369 | 0.715265 | 0.519843 |

| ~ Attitude | 0.450758 | 0.655674 | 0.534073 | 0.645851 |

| Practice | 0.603692 | 0.701364 | 0.575084 | 0.555452 |

| ~ Practice | 0.617361 | 0.636051 | 0.690811 | 0.591696 |

Cons consistency, Cov, coverage; ~ , absence of condition; Condition needed: consistency ≥ 0.90.

Sufficiency analysis

With regard to sufficiency analysis, the combination of conditions affecting OHRQoL was calculated (Table 4). The frequency cutoff value in the truth table is set to 1 and the consistency cutoff value is set to 0.77.

Table 4.

Combination of conditions affecting oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL).

| Raw coverage | Unique coverage | Consistency | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Causal models from a high level of OHRQoL | |||

| OHRQoL = f(SS*SE*K*A*P) | |||

| C1: SE*K*A | 0.492309 | 0.182291 | 0.755461 |

| C2: ~ SS*SE*A* ~ P | 0.288985 | 0.0259813 | 0.827282 |

| C3: SS*SE*K* ~ P | 0.295456 | 0.0231438 | 0.806144 |

| solution coverage: 0.541434 | |||

| solution consistency: 0.753271 | |||

| Causal models from a low level of OHRQoL | |||

| ~ OHRQoL = f(SS*SE*K*A*P) | |||

| NC: ~ SS* ~ SE* ~ K* ~ A* ~ P | 0.388053 | 0.388053 | 0.751024 |

| solution coverage: 0.388053 | |||

| solution consistency: 0.751024 | |||

SS social support, SE self-efficacy, K knowledge, A attitude, P practice, OHRQoL oral health-related quality of life.

The forward solution shows that the combination of three causal conditions can produce better OHRQoL (consistency = 0.75; coverage = 0.54; Table 4). As mentioned earlier, in the sufficiency analysis the original coverage refers to the variance of the interpretation, which means that the number of observations can be explained by a specific combination of conditions. The consistency of the solution indicates the reliability or fitness of the model. In fsQCA, when the overall consistency of the model is ≥ 0.66, the model is valid50. Therefore, the solution obtained through fsQCA is effective.

The fsQCA results showed that a combination of better self-efficacy, a positive oral health attitude, and rich oral health knowledge were associated with good OHRQoL (C1 in Table 4, coverage = 0.49; consistency = 0.75). Higher self-efficacy, richer oral health knowledge, greater social support and lower oral health attitude were supported to better OHRQoL (C3 in Table 4, coverage = 0.30; consistency = 0.80). Another combination that was linked to good OHRQoL was having high self-efficacy and a positive attitude towards oral health, even if the individual had poor oral health practices and lower social support (C2 in Table 4, coverage = 0.29; consistency = 0.82).

Comparsion of PLS-SEM and fsQCA

The study utilized PLS-SEM to determine the positive effects of social support, self-efficacy, oral health knowledge, attitudes, and practices on OHRQoL, with self-efficacy playing an intermediary role. The results also indicated that the average variance extraction (AVE) of these dimensions was > 0.5, demonstrating the effectiveness of convergence. Furthermore, fsQCA identified two combinations associated with good OHRQoL: better self-efficacy, a positive oral health attitude, and rich oral health knowledge; and high self-efficacy and a positive attitude towards oral health, even in individuals with poor oral health practices and lower social support. The fsQCA results reinforce the PLS-SEM results (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison between the results of PLS-SEM and fsQCA.

| Methods | ||

|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis | Structural equation model (SEM) | Fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) |

| H1 | Supported | Conditional supported |

| H2 | Supported | Conditional supported |

| H3 | Supported | Conditional supported |

| H4 | Supported | Conditional supported |

| H5 | Not supported | n.a.a |

| H6 | Not supported | n.a.a |

| H7 | Not supported | n.a.a |

| H8 | Not supported | n.a.a |

| H9 | Supported | Conditional supported |

| H10 | Supported | Conditional supported |

| H11 | Supported | Conditional supported |

| H12 | Supported | Conditional supported |

aNot applicable.

Discussion

The results of this study show that social support, oral knowledge, attitudes, and practice should use self-efficacy as an intermediary variable to affect college students’ OHRQoL. This is consistent with the results of previous studies13,51. In addition, previous studies on the influencing factors of OHRQoL mainly use traditional symmetry and linear relationship analysis, which may ignore the existence of multiple complex causalities among the influencing factors. Therefore, this study not only constructed an SEM model to explore the linear relationship between variables, but also used the fsQCA method to supplement the conclusion of multiple complex causalities.

The PLS-SEM results (Table 2, Fig. 2) show that self-efficacy is the core factor affecting OHRQoL and mediates between other factors and OHRQoL. The fsQCA partially validates the SEM results (Table 5). Although the influencing factors do not necessarily affect OHRQoL, self-efficacy factors are involved in all solutions (C1, C2, and C3 in Table 4). This illustrates the core role of self-efficacy and partially verifies its intermediary role (Table 4), which is similar to previous results52. In social cognitive theory, self-efficacy can predict individual behavior specificity, health quality, and well-being; and evaluation of self-efficacy and quality of life is an important part of the core outcome of frequently-occurring diseases53.

Similarly, self-efficacy is also an important factor in the self-management of chronic diseases54–56, such as hypertension57 and diabetes58. A study of patients with type 2 diabetes found that patients with high self-efficacy paid more attention to learning relevant knowledge and actively managing the condition59. Therefore, we should pay attention to improving individual self-efficacy, especially the level of oral knowledge and cultivating a positive attitude to significantly improve OHRQoL.

At the same time, the complex relationship between self-efficacy and its predictor factors also provides new ideas and insights for improving OHRQoL. Knowledge, attitude, and practice indirectly affect OHRQoL: knowledge indirectly affects practice through attitude, and attitude affects self-efficacy through practice, thus affecting OHRQoL (Table 2). The relationship between knowledge and attitude is similar to a previous study60. It is considered that people with a more positive attitude and a higher level of dental knowledge have better tooth brushing practice60. In the fsQCA positive solution, the higher coverage solution (C1 in Table 4) show that individual self-efficacy, oral knowledge and attitude can be considered important conditions affecting OHRQoL, but the results do not reflect the impact of practice. This is slightly different from previous studies61. The possible reason is that Chinese college students in this study are still in the sensitive period of constructing oral health practice, have strong plasticity, and are influenced by knowledge and attitude. Therefore, the results of this study support the core effect of the combination of knowledge, attitude, and self-efficacy on OHRQoL, which is consistent with previous results62. It is believed that patients with high quality of life have a high level of knowledge, a positive attitude and a greater sense of self-efficacy63.

Social support indirectly affects OHRQoL through the intermediary role of self-efficacy and a wide range of multi-dimensional factors such as knowledge, attitude and practice (Table 2), this is similar to previous results54. The indirect effect of social support is partially supported in the fsQCA solution (C3 in Table 4), which affects OHRQoL through a combination of self-efficacy and knowledge. This is consistent with results from patients with diabetes, suggesting that social support and knowledge are key prerequisites for patients’ self-care behavior64, and that having better social support and a high level of knowledge can better promote self-care. However, the fsQCA solution (C2 in Table 4) indicates that a combination of good attitude and strong self-efficacy can also support a high level of OHRQoL in the absence of social support, which to a certain extent emphasizes the impact of individual attitudes on oral health outcomes. This is consistent with Canter et al.62.

Consistent with Bandura's social cognitive theory, the results of this study further confirm that strategies to improve self-efficacy are beneficial to the improvement of health-related quality (HRQoL)65. However, this contrasts with the findings of Grolnick, W., who suggested that when parents over-intervene in balancing the health needs of adolescents, it may reduce their self-efficacy and lead to rebellious behavior66. Researcher can also give positive incentives to groups who correctly implement behaviors so that individuals can gain a higher sense of self-efficacy to improve oral health. This is also consistent with the fact that the external environment, human behavior, and individual cognitive processes jointly influence personal activities in Bandura's social cognitive theory51. Therefore, training for self-efficacy and its predictor factors will be the key to helping teenagers improve or maintain OHRQoL.

The rich and complex configuration of fsQCA results can help researchers improve oral health. The higher coverage solution (Table 4, score C1) shows that good self-efficacy, a high level of oral health knowledge and a positive attitude can improve OHRQoL. Therefore, it is necessary to regularly publicize oral health knowledge and improve cognitive levels among college students, while exploring internal motivation and favorable expectations of the group to guide college students to adopt positive attitudes to deal with various oral conditions. When teenagers have a successful experience and gain confidence, their self-efficacy improves, which further promotes the improvement or maintenance of their own OHRQoL, thus forming a positive feedback effect. This is consistent with previous measures aimed at self-management and improving the quality of life of patients with asthma63.

In addition, the development of extensive social support within the youth group will also help to improve the OHRQoL level. Researchers can obtain more extensive social support by encouraging subjects to increase social connections and communication activities, or through specific interventions to enhance subjects' perception of social support, to achieve higher self-efficacy and improve their quality of life. This is consistent with interventions to enhance perceived social support (PSS) and self-efficacy of patients with periodontitis, thereby improving their HRQoL after treatment23. At the same time, the OHRQoL of adolescents can be influenced from the social level by changing the public's concept of oral health, which is consistent with the strategy for the prevention of chronic diseases67.

In summary, the results obtained from the comprehensive application of PLS-SEM and fsQCA not only enrich the theoretical and practical value of the complex causal relationship between OHRQoL and multiple factors, but also lay a foundation for related research on the influencing factors of OHRQoL and provide a practical basis for the development of interventions to improve OHRQoL. However, this study also has some limitations. The study sample comprises college students aged 17–23, which may limit the generalizability of the conclusions. Furthermore, Lisa M. Jamieson's study noted that the cross-sectional nature of the findings does not establish causality68. To fully address this limitation, a longitudinal study design is necessary to investigate the influence of confounding factors on self-efficacy and oral health-related quality of life. Such a study would help establish a causal relationship between these two factors.

Conclusions

Combining the advantages of PLS-SEM and fsQCA, this paper analyzed factors related to social support, oral health knowledge, attitude, practice, and self-efficacy that affect the oral health of college students. The results show that self-efficacy is the core factor affecting OHRQoL, and has an intermediary effect between other factors and OHRQoL. Social support acts widely on other influencing factors and has a positive effect on OHRQoL. While partially verifying the results of SEM, fsQCA suggests that other influencing factors are related to the complex configuration of OHRQoL. Among them, the combination of self-efficacy, oral knowledge, and attitude has greater coverage and a greater impact on OHRQoL. Therefore, the key to improving an individual college student’s OHRQoL is to improve self-efficacy. Under this premise, regular education to improve oral health understanding and guide them to actively deal with their own oral conditions will help to improve or maintain good OHRQoL. At the same time, developing extensive social support from around the college students group will also help to improve OHRQoL at a group level.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the teachers and students who participated, and SmartPLS 3.0 and fsQCA 3.1 for their assistance in analysis of data of this process.

Author contributions

J.Z. and Z.L.X. conceived the project with the input of Y.W.2 and K.D.C. Y.W.1, J.Z., and Z.L.X. collected and analyzed the relevant data for this study. Y.W. 1and J.Z. are the main authors of this study. All the authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the General project of the Traditional Chinese Medicine Administration of Zhejiang Province (2016ZA134), the High-level pre-research program of Zhejiang Shuren university in 2019, 2022 Zhejiang Province First-class Curriculum Funding Project (ZTE Letter [2021] No. 352), 2021 Zhejiang Province First-class Curriculum Funding Project (ZTE Letter [2021] No. 195 item 588), 2021 Zhejiang Province Curriculum Civics Model Course Funding Project (ZTE Letter [2021] No. 47 item 249), 2023 Zhejiang Province Student Science and Technology Innovation Activity Plan and New Talent Program and 2021–2022 Provincial University-Industry Cooperation Collaborative Education Project.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Ying Wang and Jie Zhu.

Contributor Information

Keda Chen, Email: chenkd@zjsru.edu.cn.

Ying Wang, Email: ywang@zjsru.edu.cn.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-023-39658-6.

References

- 1.Merdad L, El-Housseiny AA. Do children’s previous dental experience and fear affect their perceived oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL)? BMC Oral Health. 2017;17:47. doi: 10.1186/s12903-017-0338-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Locker D, Clarke M, Payne B. Self-perceived oral health status, psychological well-being, and life satisfaction in an older adult population. J Dent Res. 2000;79:970–975. doi: 10.1177/00220345000790041301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silk H, Kwok A. Addressing adolescent oral health: A review. Pediatr. Rev. 2017;38:61–68. doi: 10.1542/pir.2016-0134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young C. Are young people leaving home earlier or later. J. Aust. Popul. Assoc. 1996;13:125–152. doi: 10.1007/BF03029491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhu L, Petersen PE, Wang HY, Bian JY, Zhang BX. Oral health knowledge, attitudes and behaviour of adults in China. Int. Dent. J. 2005;55:231–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2005.tb00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiang B, Wong HM, Perfecto AP, McGrath CPJ. The association of socio-economic status, dental anxiety, and behavioral and clinical variables with adolescents’ oral health-related quality of life. Qual. Life Res. 2020;29:2455–2464. doi: 10.1007/s11136-020-02504-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sischo L, Broder HL. Oral health-related quality of life: What, why, how, and future implications. J. Dent. Res. 2011;90:1264–1270. doi: 10.1177/0022034511399918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Organization WH. The World Health Report 2002: Reducing risks, Promoting Healthy Life. World Health Organization; 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bullinger M, Quitmann J. Quality of life as patient-reported outcomes: Principles of assessment. Dialog. Clin. Neurosci. 2022 doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2014.16.2/mbullinger. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malele-Kolisa Y, Yengopal V, Igumbor J, Nqcobo CB, Ralephenya TRD. Systematic review of factors influencing oral health-related quality of life in children in Africa. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2019;11:e1–e12. doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v11i1.1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gomes AC, et al. Socioeconomic status, social support, oral health beliefs, psychosocial factors, health behaviours and health-related quality of life in adolescents. Qual. Life Res. 2020;29:141–151. doi: 10.1007/s11136-019-02279-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Syrjälä AM, Knuuttila ML, Syrjälä LK. Self-efficacy perceptions in oral health behavior. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2001;59:1–6. doi: 10.1080/000163501300035661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zheng S, et al. Relationship between oral health-related knowledge, attitudes, practice, self-rated oral health and oral health-related quality of life among Chinese college students: A structural equation modeling approach. BMC Oral Health. 2021;21:99. doi: 10.1186/s12903-021-01419-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bettinghaus EP. Health promotion and the knowledge-attitude-behavior continuum. Prev. Med. 1986;15:475–491. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(86)90025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liao X, Nguyen TPL, Sasaki N. Use of the knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) model to examine sustainable agriculture in Thailand. Reg. Sustain. 2022;3:41–52. doi: 10.1016/j.regsus.2022.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991;50:179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Litt MD, Reisine S. Multidimensional causal model of dental caries development in low-income preschool children. Pub. Health Rep. 1995;11:607–617. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Syrjala AM, Kneckt MC, Knuuttila ML. Dental self-efficacy as a determinant to oral health behaviour, oral hygiene and HbA1c level among diabetic patients. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1999;26:616–621. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051X.1999.260909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Silva-Sanigorski A, et al. Parental self-efficacy and oral health-related knowledge are associated with parent and child oral health behaviors and self-reported oral health status. Commun. Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2013;41:345–352. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bundura A. Self-efficacy toward a unifying theory. Psychol. Rev. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.BenGhasheer HF, Saub R. Relationships of acculturative stress, perceived stress, and social support with oral health-related quality of life among international students in Malaysia: A structural equation modelling. Int. Soc. Prev. Commun. Dent. 2020;10:520. doi: 10.4103/jispcd.JISPCD_192_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hashemi ZS, Khorsandi M, Shamsi M, Moradzadeh R. Effect combined learning on oral health self-efficacy and self-care behaviors of students: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Oral Health. 2021;21:342. doi: 10.1186/s12903-021-01693-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miao L, Feng J, Wu L. The mediating role of self-efficacy in the relationship between Big five personality and depressive symptoms among Chinese unemployed population a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 2016;16:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12903-016-0227-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slater MD. Social influences and cognitive control as predictors of self-efficacy and eating behavior.pdf. Cognit. Ther. Res. 1989;13:231–245. doi: 10.1007/BF01173405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu J, Wei W, Peng Q, Guo Y. How does perceived health status affect depression in older adults? Roles of attitude toward aging and social support. Clin. Gerontol. 2021;44:169–180. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2019.1655123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erhart M, Wille N, Ravens-Sieberer U. Empowerment of children and adolescents–the role of personal and social resources and personal autonomy for subjective health. Gesundheitswesen. 2008;70:721–729. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1103261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao J, et al. Oral health status and oral health knowledge, attitudes and behavior among rural children in Shaanxi, western China: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14:1–7. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-14-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khan N, Ahmed SM, Khalid MM, Siddiqui SH, Merchant AA. Effect of gender and age on the knowledge, attitude and practice regarding hepatitis B and C and vaccination status of hepatitis B among medical students of Karachi. Pak. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2010;60(6):450–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vettore MV, Ahmad SF, Machuca C, Fontanini H. Socio-economic status, social support, social network, dental status, and oral health reported outcomes in adolescents. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2019;127:139–146. doi: 10.1111/eos.12605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mizutani S, et al. Effects of self-efficacy on oral health behaviours and gingival health in university students aged 18-or 19-years-old. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2012;39:844–849. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2012.01919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suresh BS, Ravishankar TL, Chaitra TR, Mohapatra AK, Gupta V. Mother’s knowledge about pre-school child’s oral health. J. Indian Soc. Pedod. Prev. Dent. 2010;28:282–287. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.76159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saied-Moallemi Z, Virtanen JI, Ghofranipour F, Murtomaa H. Influence of mothers’ oral health knowledge and attitudes on their children’s dental health. Eur. Arch. Paediatr. Dent.: Off. J. Eur. Acad. Paediatr. Dent. 2008;9:79–83. doi: 10.1007/BF03262614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J. Pers. Assess. 1988;52:30–41. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vaux A, et al. The social support appraisals (SS-A) scale studies of reliability and validity. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 1986;14:195–218. doi: 10.1007/BF00911821. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kakudate N, Morita M, Kawanami M. Oral health care-specific self-efficacy assessment predicts patient completion of periodontal treatment: A pilot cohort study. J. Periodontol. 2008;79:1041–1047. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martos-Méndez MJ. Self-efficacy and adherence to treatment: The mediating effects of social support. J. Behav. Health Soc. Issues. 2015;7:19–29. doi: 10.5460/jbhsi.v7.2.52889. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu HX, et al. Record of the press conference on the results obtained from the 4th national oral health epidemiology survey. Chin. J. Dent. Res.: Off. J. Sci. Sect. Chin. Stomatol. Assoc. (CSA) 2017;21:161–165. doi: 10.3290/j.cjdr.a41079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Andiappan M, Gao W, Bernabe E, Kandala NB, Donaldson AN. Malocclusion, orthodontic treatment, and the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-14): Systematic review and meta-analysis. Angle Orthod. 2015;85:493–500. doi: 10.2319/051414-348.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ringle CM, Wende S, Becker JM. SmartPLS 3. SmartPLS GmbH, Boenningstedt. J. Serv. Sci. Manag. 2015;10(3):32–49. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rihoux B, Ragin CC. Configurational Comparative Methods: Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) and Related Techniques. Sage Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mozas-Moral A, Bernal-Jurado E, Medina-Viruel MJ, Fernández-Uclés D. Factors for success in online social networks: An fsQCA approach. J. Bus. Res. 2016;69:5261–5264. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eng S, Woodside AG. Configural analysis of the drinking man: fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analyses. Addict. Behav. 2012;37:541–543. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sawyer SM, et al. Adolescence: A foundation for future health. The Lancet. 2012;379:1630–1640. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fornell C, Larcker DF. Evaluating structural equation models with unobserved variables and measurement error. J. Market. Res. 1981;18:39–50. doi: 10.1177/002224378101800104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dijkstra TK, Henseler J. Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Q. 2015;39:297–316. doi: 10.25300/MISQ/2015/39.2.02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hegbom F, et al. Effects of short-term exercise training on symptoms and quality of life in patients with chronic atrial fibrillation. Int. J. Cardiol. 2007;116:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chin WW. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Meth. Bus. Res. 1998;295:295–336. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hair JF, Jr, Hult GTM, Ringle CM. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Sage Publications; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ragin CC. Redesigning Social Inquiry: Fuzzy Sets and Beyond. University of Chicago Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 50.P, E. & D, S. in 2nd international QCA expert workshop (2014).

- 51.Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action. Englewood Cliffs, 1986 (1986).

- 52.Kiyak HA. Measuring psychosocial variables that predict older persons’ oral health behaviour. Gerodontology. 1996;13:69–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.1996.tb00157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith SM, et al. A core outcome set for multimorbidity research (COSmm) Ann. Fam. Med. 2018;16:132–138. doi: 10.1370/afm.2178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bahari G, Scafide K, Krall J, Mallinson RK, Weinstein AA. Mediating role of self-efficacy in the relationship between family social support and hypertension self-care behaviours: A cross-sectional study of Saudi men with hypertension. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2019;25:e12785. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang S, Edwards H, Yates P, Li C, Guo Q. Self-efficacy partially mediates between social support and health-related quality of life in family caregivers for dementia patients in Shanghai. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2014;37:34–44. doi: 10.1159/000351865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Benight CC, Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of posttraumatic recovery: The role of perceived self-efficacy. Behav. Res. Ther. 2004;42:1129–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang C, Lang J, Xuan L, Li X, Zhang L. The effect of health literacy and self-management efficacy on the health-related quality of life of hypertensive patients in a western rural area of China: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Equity Health. 2017;16:58. doi: 10.1186/s12939-017-0551-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee EH, Lee YW, Moon SH. A structural equation model linking health literacy to self-efficacy, self-care activities, and health-related quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes. Asian Nurs. Res. (Korean Soc. Nurs. Sci.) 2016;10:82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Qiu T, Huang J, Wang W. Association between diabetes knowledge and self-efficacy in patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus in china: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2020;2020:2393150. doi: 10.1155/2020/2393150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lin HC, Wong MC, Wang ZJ, Lo EC. Oral health knowledge, attitudes, and practices of Chinese adults. J. Dent. Res. 2001;80:1466–1470. doi: 10.1177/00220345010800051601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhao J, et al. Association of oral health knowledge, self-efficacy and behaviours with oral health-related quality of life in Chinese primary school children: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e062170. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-062170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Canter KS, et al. The relationship between attitudes toward illness and quality of life for children with cancer and healthy siblings. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2015;24:2693–2698. doi: 10.1007/s10826-014-0071-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mancuso CA, Sayles W, Allegrante JP. Knowledge, attitude, and self-efficacy in asthma self-management and quality of life. J. Asthma. 2010;47:883–888. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2010.492540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Handayani, L., Kosnin, A. M. & Jiar, Y. K. Social support, knowledge, attitude, and self-efficacy as predictors on breastfeeding practice. Univ Technol. (2010).

- 65.Cramm JM, Strating MM, Roebroeck ME, Nieboer AP. The importance of general self-efficacy for the quality of life of adolescents with chronic conditions. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013;113:551–561. doi: 10.1007/s11205-012-0110-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Grolnick WS, Pomerantz EM. Issues and challenges in studying parental control: Toward a new conceptualization. Child Dev. Perspect. 2009;3:165–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2009.00101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Beaglehole R, Ebrahim S, Reddy S, Voûte J, Leeder S. Prevention of chronic diseases: A call to action. The Lancet. 2007;370:2152–2157. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(07)61700-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jamieson LM, Parker EJ, Roberts-Thomson KF, Lawrence HP, Broughton J. Self-efficacy and self-rated oral health among pregnant aboriginal Australian women. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14:1–7. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-14-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.