CASE

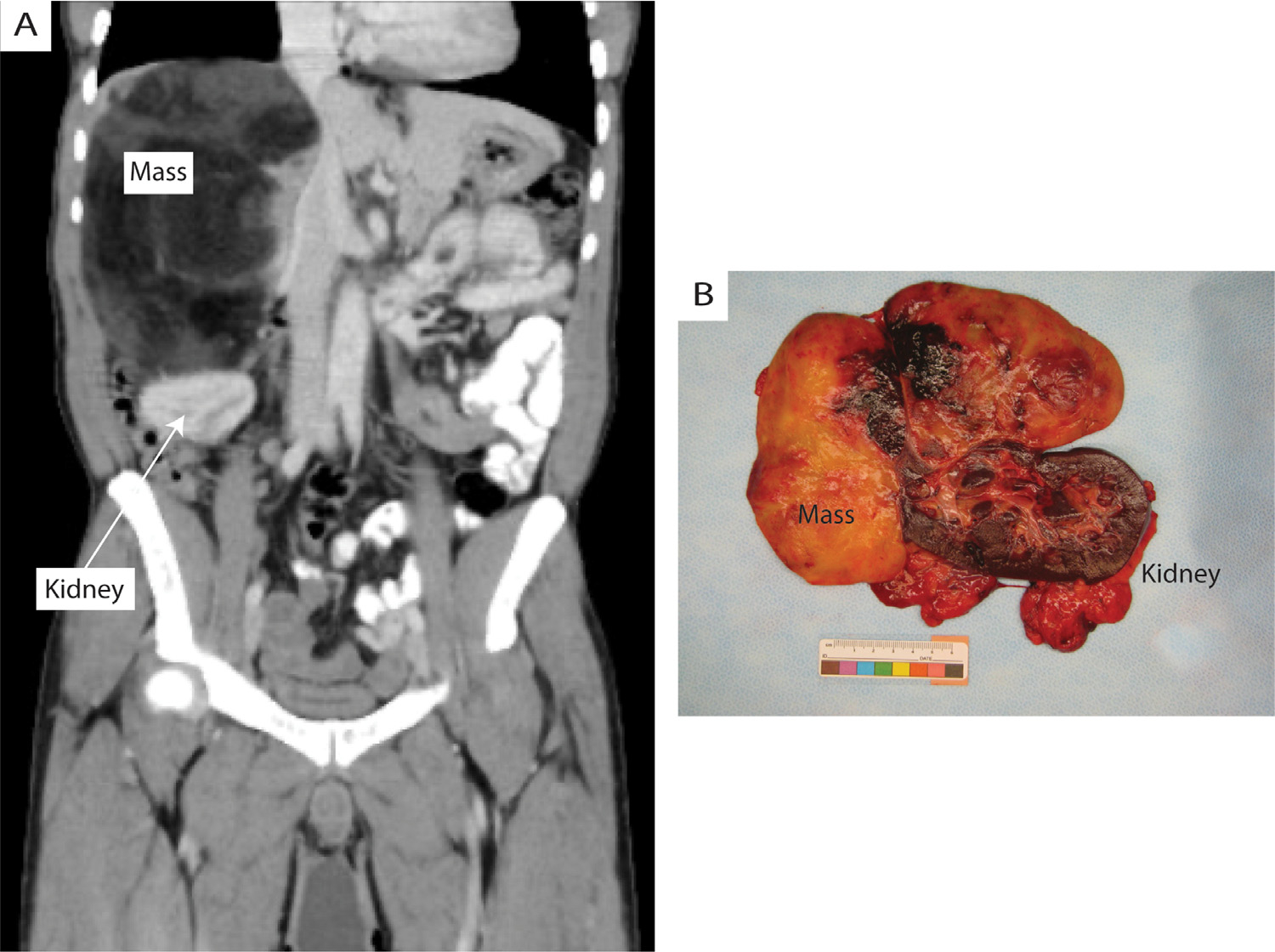

A 46-year-old man with sickle cell anemia was taken to the operating room for resection of a 19 cm right-sided retroperitoneal mass identified on CT performed for flank pain (Fig. 1A). The mass was removed en bloc with the adrenal and kidney (Fig. 1B). Hepatic mobilization with ligation of the venous branches draining the caudate lobe and the right hepatic artery was performed along with a small, non-anatomical partial hepatectomy at a location where the mass was densely adherent to the liver. On post-operative day#2 the patient was jaundiced. Total bilirubin was 24.4 mg/dL (direct component 20.0 mg/dL) with corresponding hemoglobin of 6.8 g/dL and mild transaminitis (Table 1). CT scan only revealed a 6 cm simple fluid collection within the resection fossa, but the bilirubin continued to rise. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography on post-operative day#4 revealed a persistent fluid collection but no biliary ductal dilation. Subsequent cholescintigraphy revealed no extravasation of the 99mTc-mebrofenin radiotracer.

Figure 1.

(A) Pre-operative contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrating large right-sided retroperitoneal mass, shown in coronal view. (B) Gross pathology image of resected specimen in cross section.

Table 1.

Relevant laboratory data prior to and following the operation

| Pre-op* | POD#0 (intra-op)† | POD#1 | POD#2* | POD#3 | POD#4 | POD#5 | POD#6 | POD#11 | POD#34 | POD#61 | Reference Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin | 8.7 | 9.0 | 9.2 | 6.8 | 9.7 | 11.2 | 11.0 | 10.7 | 11.6 | 9.9 | 10.3 | 13.9–16.3 g/dL |

| Bilirubin, total | 2.4 | 3.8 | 9.9 | 24.4 | 34.1 | 34.8 | 37.6 | 35.0 | 13.8 | 4.3 | 2.9 | 0–1.2 mg/dL |

| Bilirubin, direct | - | - | 5.5 | 20.0 | 33.0 | 34.0 | 36.0 | 28.4 | 8.7 | 2.44 | - | 0–0.4 mg/dL |

| ALT | 46 | 63 | 68 | 65 | 63 | 54 | 55 | 58 | 70 | 46 | 42 | 0–40 U/L |

| ALP | 199 | 135 | 136 | 105 | 120 | 112 | 136 | 158 | 310 | 277 | 210 | 30–120 U/L |

| AST | 56 | 87 | 133 | 149 | 122 | 80 | 71 | 67 | 68 | 46 | 44 | 0–37 U/L |

ALT, alanine amino transferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; AST, aspartate amino transferase; POD, post-operative day.

The patient was transfused 2 units of packed red blood cells (pRBC) prior to the operation, 2 units pRBC on POD#2.

Estimated blood loss from the surgery was 250 mL.

What Is Your Diagnosis?

Common bile duct injury

Biliary duct obstruction

Hepatic sequestration

Stauffer’s syndrome

Diagnosis

-

C.

Hepatic sequestration

DISCUSSION

Ligating the right hepatic artery placed the patient at risk for a bile duct injury however the negative Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography and cholescintigraphy excluded both bile duct leak and obstruction from the differential. Furthermore, an isolated right hepatic artery injury rarely results in clinical symptoms as blood flow should be maintained via collateral vessels originating from the remaining hepatic and gastroduodenal arteries.1 Stauffer’s syndrome with jaundice was unlikely as its manifestations should improve after tumor resection and in 90% of cases alkaline phosphatase is elevated.2 Sickle cell hepatopathies (acute sickle cell hepatic crisis, acute intrahepatic cholestasis, and hepatic sequestration) are a spectrum of hepatic complications caused by intrahepatic sickling and sinusoidal obstruction, most often seen in patients with sickle cell anemia.3 Identifying the predominant sickle cell hepatopathy rely on the degree of conjugated bilirubin elevation and transaminitis.3 This patient likely had hepatic sequestration as these patients typically present with abdominal pain, jaundice, an acute drop in hemoglobin, a rapid rise in conjugated bilirubin, and hepatomegaly resulting from trapped sickled red blood cells in the liver sinusoids.3 Management is supportive with blood transfusion and/or exchange transfusion, and our patient received both.4 After the 3 to 4-day acute phase of hepatic sequestration hemoglobin levels increase and occasionally phlebotomy is be needed to prevent blood hyperviscosity.5 Early recognition of acute sickle cell hepatopathies and prompt involvement of hematology is important as they can be fatal.6 Ultimately the patient recovered well and surgical pathology revealed an adrenal myelolipoma.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: none.

Declarations of interest: none.

References

- 1.Strasberg SM, Helton WS. An analytical review of vasculobiliary injury in laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy. HPB (Oxford). 2011;13:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma N, Darr U, Darr A, Sood G. Stauffer Syndrome: a comprehensive review of the icteric variant of the syndrome. Cureus. 2019;11:e6032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shah R, Taborda C, Chawla S. Acute and chronic hepatobiliary manifestations of sickle cell disease: a review. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2017;8:108–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kyrana E, Rees D, Lacaille F, et al. Clinical management of sickle cell liver disease in children and young adults. Arch Dis Child. 2021;106:315–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee ES, Chu PC. Reverse sequestration in a case of sickle crisis. Postgrad Med J. 1996;72:487–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allali S, de Montalembert M, Brousse V, et al. Hepatobiliary complications in children with sickle cell disease: a retrospective review of medical records from 616 patients. J Clin Med. 2019;8:1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]