Abstract

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are the most used acid-inhibitory drugs, with a wide range of applications in the treatment of various digestive diseases. However, recently, there has been a growing number of digestive complications linked to PPIs, and several studies have indicated that the intestinal flora play an important role in these complications. Therefore, developing a greater understanding of the role of the gut microbiota in PPI-related digestive diseases is essential. Here, we summarize the current research on the correlation between PPI-related digestive disorders and intestinal flora and establish the altered strains and possible pathogenic mechanisms of the different diseases. We aimed to provide a theoretical basis and reference for the future treatment and prevention of PPI-related digestive complications based on the regulation of the intestinal microbiota.

Keywords: proton pump inhibitors, digestive diseases, microbiota, intestinal flora, Clostridium difficile, inflammatory bowel disease, short-chain fatty acids

Introduction

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are currently the most widely used acid-suppressive agents and are the first-line therapy for gastric acid–related disorders, such as peptic ulcer disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and Barrett’s esophagus (Freedberg et al., 2017). PPIs accumulate in parietal cells via circulation throughout the body. The acidic environment surrounding parietal cells prompts the conversion of PPI prodrugs to active metabolites, which then inhibits gastric H+, K+–ATPase activity in epithelial cells to prevent gastric acid secretion (Sachs et al., 2006; Shin and Kim, 2013). Although PPIs exhibit exceptional acid inhibition effects, various studies have linked PPI use with adverse digestive events, such as small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) and Clostridium difficile infection. Considering the wide range of PPI applications, these complications warrant further attention.

The human gastrointestinal tract is colonized by 500–1,000 species of bacteria, totaling approximately 1014 individuals (Gilbert et al., 2018). Microorganisms that assist the host in physiological and biochemical functions are collectively referred to as intestinal flora (Sender et al., 2016). The intestinal flora is increasingly being highlighted as a key factor in digestive health. Normal intestinal flora can prevent pathogenic microbes from colonizing the digestive tract by depleting surrounding nutrients and producing antimicrobial substances, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and bacteriocins (Masanta et al., 2013). Second, the intestinal microbiota produce various metabolites that influence the host gastrointestinal physiological functions (Collins, 2014); one such example is butyrate, which is essential for maintaining the integrity of the colonic epithelium (Jørgensen and Mortensen, 2000). The intestinal flora is also crucial for the maturation of the host mucosal immune system during early life; additionally, the microbiota maintains this regulation throughout life via ongoing interactions with the gastrointestinal mucosa (McDermott and Huffnagle, 2014). Furthermore, the intestinal flora plays an important role in nutrient absorption and energy homeostasis (Flint et al., 2012). Therefore, PPI-induced gut microbiota may significantly affect the corresponding pharmacological action of PPIs.

Numerous studies have shown that PPIs significantly alter the intestinal flora of patients; these changes have been closely associated with PPI-associated digestive complications (Malfertheiner et al., 2017), including functional dyspepsia (FD), SIBO, and C. difficile-associated disease (CDAD). Thus, it is of great significance to clarify these PPI-associated changes in the intestinal flora and their corresponding role in different gut disorders. This review aimed to evaluate the association between PPI-dependent alterations in the intestinal flora and resultant digestive diseases. We also discussed the changes in the specific disease-associated strains and their possible mechanisms in related intestinal disorders, with the aim of providing a deeper understanding of PPI-related digestive complications.

Impact and mechanisms of PPIs on intestinal flora

Normal intestinal flora is primarily composed of Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, and Actinobacteria. The dominant bacteria varies between specific sites: gram-positive aerobic bacteria are the dominant species in the duodenum; gram-positive/gram-negative anaerobes and facultative anaerobes are dominant in the ileum; and obligate anaerobes, particularly Bacteroides, are the predominant species of the colon (Canny and McCormick, 2008; Molloy et al., 2012). After PPI application, Planococcaceae, Oxalobacteraceae, and Sphingomonadaceae populations have been found to increase in the proximal small intestine (Freedberg et al., 2014); (Shi et al., 2019). The abundance of several taxa, including the orders Bacillales (e.g., Staphylococcaceae), Lactobacillales (e.g., Enterococcaceae, Lactobacillaceae, and Streptococcaceae), and Actinomycetales (e.g., Actinomycetaceae, and Micrococcaceae), were observed to increase in the distal small intestine and blind colon. The abundance of the families Bifidobacteriaceae, Ruminococcaceae, and Lachnospiraceae also decreased following PPI treatment. (Perry et al., 2020). Overall, PPI-induced intestinal bacterial alteration is significant and extensive and may be closely related to many digestive disorders.

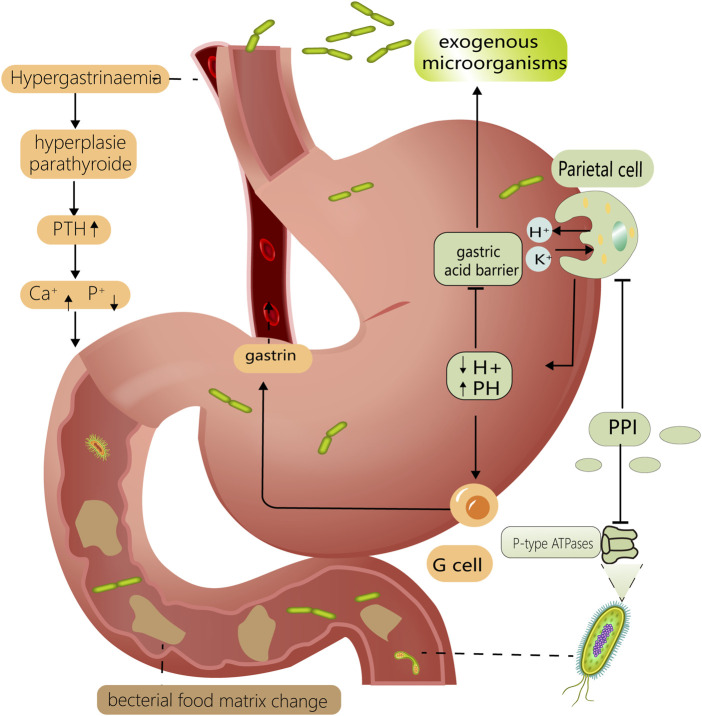

The mechanism by which PPIs affect the intestinal flora can be divided into pH- and non-pH-dependent pathways. First, direct pH modifications alter the environment of the digestive tract; therefore, bacteria with specific pH requirements, such as H. pylori, are directly affected (Perry et al., 2020). Thus, pH changes can disrupt the gastric acid barrier, making it easier for exogenous microorganisms to invade the gastrointestinal tract. There are several non-PH-dependent mechanisms by which PPIs affect the intestinal microbiota. First, PPI-induced hormonal changes, such as hypergastrinemia and hyperparathyroidism, affect intestinal osmolality as well as calcium and phosphorus metabolism, which in turn affect the intestinal flora (Yang and Metz, 2010). Second, PPIs influence digestive functions and cause changes in the composition and distribution of digestive tract contents; this may interfere with nutrient absorption functions, thereby altering the quantity or location of the bacterial food matrix and disrupting the intestinal flora (Epstein et al., 2006). Finally, PPIs affect the physiological function of several microbes by directly binding to their non-gastric H+/K+–ATPases, thereby regulating their corresponding distribution and cell count (Vesper et al., 2009); such affected microbes include fungi, Helicobacter pylori, and Streptococcus pneumoniae (Melchers et al., 1998; Hoskins et al., 2001). The ways in which PPIs affect the gut microbiota are multifaceted, which may explain their extensive impact (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Mechanisms of PPI altering intestinal flora. PPIs reduce gastric acid secretion by inhibiting H⁺/K⁺ ATPase on gastric parietal cells. Lower PH levels compromise the gastric acid barrier, allowing exogenous bacteria to enter the intestine more easily. It also has a prominent effect on microorganisms with specific PH requirements, such as Helicobacter pylori. Reduced gastric PH stimulates gastric G-cells to secrete more gastrin, resulting in hypergastrinemia and hyperparathyroidism. This can disrupt the intestinal flora by interfering with the metabolism of calcium and phosphorus in the digestive tract. PPI can also interfere with the P-type ATPase of some gut microorganisms, such as fungi and Helicobacter pylori. Above mechanisms work in concert to for PPI to have a considerable effect on the gut flora.

PPI-induced digestive system complications

FD

FD is a digestive disease with numerous complex symptoms that lack obvious pathophysiological features. Nonetheless, H. pylori infection, intestinal flora changes, and dysbiosis of the brain–gut bacterial axis may be related to FD (Ford et al., 2020); further, increases in the permeability of the intestine is receiving increasing attention as a potential cause of FD (Tominaga et al., 2007; Vanheel et al., 2014).

Several guidelines recommend PPIs for the treatment of FD to relieve acid reflux and heartburn symptoms or to aid in the eradication of H. pylori (Moayyedi et al., 2017). However, a recent study indicated that PPIs may increase intestinal permeability under high psychological stress, which was established based on changes in the adrenocorticotropic hormone–mast cell–vasoactive intestinal peptide–intestinal permeability axis (Takashima et al., 2020). Notably, the results of fecal microbiota transplantation from PPI-administered mice to germ-free mice demonstrated that the intestinal flora is closely related to variations in intestinal permeability.

Further microbiota analysis revealed that a decrease in Bifidobacterium abundance was most likely related to PPI-induced FD. Bifidobacterium are vital components of the normal intestinal flora and are crucial for the fermentation of carbohydrates into SCFAs (Tsukuda et al., 2021). Butyric acid is an essential SCFA that has a substantial effect on the gastrointestinal tract and is produced by Bifidobacterium species. Specifically, butyric acid provides energy for mitochondrial respiration in intestinal epithelial cells (Morrison and Preston, 2016), influences the growth and metabolism of intestinal epithelial cells, and affects the production and distribution of intestinal epithelial connexins (Peng et al., 2009). Furthermore, butyric acid increases smooth muscle excitability in the colon and promotes the release of 5-HT from enteroendocrine cells, both of which are beneficial for intestinal peristalsis and transit (Martin-Gallausiaux et al., 2021). These factors could elucidate the relationship observed between Bifidobacterium abundance and permeability variation in the intestinal mucosa. Overall, PPI can affect butyric acid production by reducing the abundance of Bifidobacterium, thereby causing changes in intestinal permeability and peristaltic capacity and leading to the onset of FD.

Additionally, the abundances of Streptococcus, Prevotella, Veillonella, and Actinomyces are negatively associated with the development of FD (Imhann et al., 2016; Zhong et al., 2017). Further, treatment with Lactobacillus acidophilus can reduce the increased intestinal permeability caused by stress in rats (Kang et al., 2022). Overall, the lower abundance of Streptococcus, Prevotella, and Lactobacillus in PPI-treated patients suggests that these strains may also be involved in PPI-induced FD.

Although some studies have found an association between PPI use and increased intestinal permeability, animal research models are not adequate. Additionally, the specific pathogenic mechanisms of the altered strains have not yet been clearly established. Due to the Complexity of FD diagnosis and treatment, there remains a scarcity of high-quality clinical studies pertaining to FD, which further restricts research into the exact role of PPIs in FD. We advise patients with FD to exercise caution when using PPIs and recommend discontinuation of PPI mediation once clinical symptoms are alleviated; doing so may produce significant benefits for these patients.

Lower gastrointestinal bleeding

PPIs are widely used to prevent gastrointestinal bleeding induced by NSAIDs, aspirin, and antiplatelet medications. However, recent clinical trials have demonstrated that the positive effect of these PPIs is primarily restricted to the upper gastrointestinal tract; in fact, PPIs have even been associated with bleeding in the lower gastrointestinal tract (Watanabe et al., 2008; Nagata et al., 2015; Washio et al., 2016).

In 1996, Uejima et al. (1996) established that the intestinal flora, especially gram-positive bacteria, such as Escherichia coli, play an important role in NSAID-induced gastrointestinal injury. Nadatani et al. (2019) determined that PPIs enhance the risk of indomethacin-induced small intestinal injury; further, similar small intestinal injuries were observed following the transplantation of feces from PPI-treated mice into germ-free mice. Additional microbiota analysis indicated that the primary cause of these small intestinal injuries may be a corresponding decrease in the abundance of Lactobacillus johnsonii; corresponding, the trend of damage aggravation was significantly inhibited following L. johnsonii supplementation (Nadatani et al., 2019). The protective effect of L. johnsonii may be associated with its production of lactic acid (Watanabe et al., 2009). NSAID-induced intestinal injury is primarily mediated by activation of the lipopolysaccharide/Toll-like receptor 4 signaling pathway, which, in turn, activates NF-κB to promote tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) release from monocytes cells. Both in vivo and in vitro experiments have demonstrated that lactic acid, produced by L. johnsonii, can inhibit the phosphorylation of I-κb to reduce its degradation; then, I-κb can bind to NF-κB to inhibit its activation and, thus, reduce NSAID-induced intestinal injury (Watanabe et al., 2009).

Another study also confirmed the importance of intestinal flora. Sequencing analysis revealed a decrease in the abundance of the phylum Actinomycetes, particularly Bifidobacterium, in the jejunum of individuals with gastrointestinal bleeding; nonetheless, intestinal damage was alleviated by Bifidobacterium supplementation (Wallace et al., 2011). Recent research has established that the common probiotic Bifidobacterium has many effects on the gut. For example, species of this genus optimize the structure of the intestinal flora, antagonize the colonization of E. coli, inhibit the activation of NF-κB (Bermudez-Brito et al., 2012), enhance the function of the intestinal mucus layer and cupped cells, and increase the production of mucin; ultimately, these functions may be associated with its corresponding ability to reduce gastrointestinal bleeding (Engevik et al., 2019). However, the specific underlying mechanisms of Bifidobacterium require further clarification. Alternatively, a clinical study reported that after patients were administered Lactobacillus casei for 3 months, gastrointestinal bleeding symptoms were partly relieved. However, the study design of this trial was incomplete, lacking a placebo control group and utilizing a small sample size (Endo et al., 2011).

Existing studies have documented that the intestinal flora is closely linked to PPI-induced lower gastrointestinal bleeding; however, the majority of these studies were conducted on animal models, the hierarchy of evidence was low, and the results of different studies lacked consistency with each other. The normal intestinal flora is maintained in a dynamic equilibrium based on the interaction between various microbial strains; this internal effect contributes to the complexity of the intestinal flora, which may explain the differences observed in different studies. Recent studies have focused more on the role of specific strains rather than on the overall effect of the microbiota, which also limits further understanding of the association between the intestinal flora and gastrointestinal bleeding. Ultimately, advanced sequencing technologies and multidisciplinary approaches may provide a better understanding of these interactions.

SIBO

SIBO is a disease in which the number of bacteria in the small intestine increases abnormally, resulting in the production of large amounts of hydrogen, methane, and SCFAs, thereby causing symptoms, such as bloating and diarrhea (Erdogan et al., 2015). The clinical diagnostic criteria for SIBO are not uniform, and small intestinal aspirate content culture alongside methane (CH4) and hydrogen (H2) exhalation testing are commonly used to further clarify the diagnosis (Pimentel et al., 2020).

In 1994, Fried indicated that PPI and SIBO may be related (Fried et al., 1994). Subsequently, numerous studies have been conducted to explore this issue; however, the corresponding results have been inconsistent. An early meta-analysis found no association between PPI use and SIBO prevalence (Lo and Chan, 2013). However, subsequent meta-analysis in 2018 indicated that PPI use moderately increased SIBO risk; nonetheless, subgroup analysis based on different diagnostic methods indicated a correlation between PPI use and SIBO when assessed using small intestine aspirate culture or the glucose hydrogen breath test but not when using the lactulose hydrogen breath test (Su et al., 2018). In a recent clinical trial that diagnosed SIBO using both small intestine aspirate contents and stool sample cultures, the small intestinal flora of PPI-treated and non-PPI-treated individuals was not significantly different (Weitsman et al., 2022).

This substantial disparity between studies can be attributed to various factors. First, SIBO is linked to the development of GERD (Schatz et al., 2015); this correlation may be attributed to the additional intestinal gas in patients with SIBO, causing an increase in intra-abdominal pressure, which could lead to a large reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus (Takakura and Pimentel, 2020). Nonetheless, GLP-1 and YY peptides, produced by intestinal fermentation, can delay gastric emptying and lead to the transient relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter (Urita et al., 2006); therefore, PPI, as a guideline-recommended drug for GERD, indirectly increases the occurrence of SIBO in patients with GERD. Secondly, PPI use is more prevalent in older people, which makes the participants in some studies older. Overall, older people have a higher incidence of SIBO due to poorer gastrointestinal function, which could lead to an indirect association between PPI and SIBO (Rao and Bhagatwala, 2019). Finally, different studies utilize differing diagnostic methods. At present, aspirated intestinal content culture is the gold standard for the diagnosis of SIBO, with a number of colonies >1 × 105 colony forming units/mL being diagnosed as SIBO. However, this method is invasive and challenging (Adike and DiBaise, 2018). Although methane and hydrogen breath tests are commonly used, they lack precise operating guidelines and diagnostic standards. Furthermore, the prevalence rates obtained for the same group of patients using the breath test and small intestinal content culture differed significantly (Shah et al., 2020); therefore, diagnostic methods may be the greatest limitation in exploring the link between PPIs and SIBO.

Numerous studies have focused on the association between PPIs and SIBO; however, most clinical studies and meta-analyses have not controlled for various confounding factors, such as dose, duration, and type of PPI exposure, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were also insufficiently stringent across these studies. Thus, the relationship between PPIs and SIBO ultimately remains unclear. New sequencing techniques or metabolite analyses of the intestinal flora may be of high significance for SIBO diagnosis; this could be used to effectively avoid the aforementioned issues, thereby producing high quality clinical studies to address this problem.

CDAD

In recent years, CDAD has gained increasing attention as a potential PPI-induced gastrointestinal complication. Clostridium difficile is a gram-positive anaerobic bacterium that is carried by approximately 3% of healthy adults; however, this proportion can reach 50% in long-term hospitalized patients (Poutanen and Simor, 2004).

Clostridium difficile most often takes the form of dormant spores (Kelly and LaMont, 1998); however, antibiotics, particularly fluoroquinolones, can promote spore conversion to the active trophic form, which can ultimately induce CDAD (Pépin et al., 2005). Some studies have demonstrated that PPIs can also increase the risk of developing CDAD (Dial et al., 2004; Akhtar and Shaheen, 2007; Hong et al., 2019); a recent retrospective study demonstrated that this PPI-mediated effect can reach up to 7.15-fold (Hung et al., 2021)and may be more pronounced when combined with antibiotics (Archimandritis et al., 1998).

Several potential mechanisms have been established for PPI-associated CDAD. First, PPIs regulate the gene expression levels of C. difficile–related toxins directly. When C. difficile is exposed to PPIs, the maximum expression levels of toxin-associated genes can reach approximately 120-fold the corresponding normal levels (Stewart and Hegarty, 2013). Among them, toxin A primarily affects the intestinal epithelium and can cause cytoskeletal actin disassembly via glycosylation of small GTPases in epithelial cells; this can eventually lead to cell death and increase colonic epithelial permeability, which induces the occurrence of CDAD (Wetzel and McBride, 2020). Second, elevated pH levels caused by PPIs accelerated the transition of C. difficile spores to the viable trophic form (Nerandzic et al., 2009). Third, under normal conditions, normal salivary nitrite can mix with gastric acid to create nitrogen oxides that can kill C. difficile; however, this effect is greatly diminished by the pH increase caused by PPI treatment (Cunningham et al., 2014). Finally, PPI treatment disrupts normal intestinal flora; the occurrence of CDAD is closely correlated with the overall change in intestinal microbiota induced by PPI (Clooney et al., 2016). The efficacy of fecal transplantation for CDAD also confirms the significance of normal intestinal flora in this disease (Broecker et al., 2016). Therefore, several recent clinical studies have supported the use of probiotics, such as Lactobacillus and yeast, for the treatment and prevention of CDAD (Goldenberg et al., 2017). Collectively, these results confirm the correlation between PPI treatment and CDAD.

Although many studies have indicated an association between PPI use and CDAD, most were retrospective studies with significant heterogeneity and relatively low quality of evidence. Overall, it is necessary to exercise caution when prescribing PPIs to patients with CDAD risk factors, such as long-term hospitalization and a history of CDAD; additionally, probiotics should be considered as a novel strategy for the prevention of CDAD.

Gastrointestinal infectious diseases

PPI users are more likely to develop bacterial gastroenteritis, which is primarily caused by Salmonella and Campylobacter (García Rodríguez et al., 2007; Doorduyn et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2014). Several mechanisms have been established for PPI-associated bacterial gastroenteritis. First, PPIs disrupt the gastric acid barrier, allowing exogenous bacteria, particularly acid-resistant bacteria, to enter the gastrointestinal tract easily (Martinsen et al., 2019). According to in vitro tests, most exogenous bacteria, including Vibrio cholerae and Campylobacter jejuni, are disturbed at a pH of 3.0; however, Salmonella and Campylobacter can still persist under these conditions and can rapidly multiply due to their shortened incubation period (Foley et al., 2013). Second, normal intestinal flora can antagonize the colonization of pathogenic bacteria through the production of antimicrobial substances, such as organic acids, bacteriocins, and competing nutrients (Zhao et al., 2018); however, PPI treatment disrupts the balance of intestinal flora, leading to a reduction in the normal antagonistic effect against exogenous bacteria. Further, this altered gut microbiota has been reported to instead facilitate the exposure of intestinal epithelial cells to pathogenic bacteria (Freedberg et al., 2014) and may even provide a protective environment for these ingested pathogens (Masanta et al., 2013). Finally, PPIs inhibit lysosomal acidification by suppressing the neutrophil vacuolar-type H+ ATPase (V-ATPase), which ultimately reduces neutrophil antibacterial activity (Song et al., 2017).

Despite numerous clinical studies supporting the link between PPI and bacterial gastroenteritis, most prior research designs are imperfect. Some studies have suggested that excluding participants who had gastroenteritis prior to the first use of PPIs or correcting for confounding factors, such as susceptibility and time dependence of bacterial gastrointestinal infections, can remarkably reduce the association between PPI treatment and bacterial gastroenteritis (Garcia Rodríguez and Ruigómez, 1997; Hassing et al., 2016).

Diseases caused by fungal infections of the digestive system have also been linked to the use of PPIs, particularly Candida infections (Mottaghi et al., 2021). In addition to the factors discussed above, the PPI-induced reduction in Lactobacillus can also prompt fungal infections, the presence of Lactobacillus typically inhibits the growth of fungi, such as Pseudomonas, via the production of lactic acid (Wang et al., 2004).

PPIs have also been shown to be associated with intestinal infections caused by multidrug-resistant microorganisms. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that PPI use increased infection rate by 75% (Willems et al., 2020), including infections by multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus. The potential mechanisms for this increased infection rate include the PPI-dependent disruption of the gastric acid barrier and microecological balance (Nakamura et al., 2019).

Overall, the current literature primarily supports the link between PPI treatment and bacterial gastroenteritis; however, most results were obtained via single-center observational and retrospective studies and lack information on confounding factors, such as duration of PPI exposure, antibiotic intake, and dietary patterns. More rigorous clinical studies and higher-quality evidence are needed to establish the strength and cause-and-effect relationship of this correlation. Overall, it is also crucial to consider the risk of enteric infection when prescribing PPIs.

Cholelithiasis and biliary system diseases

Cholelithiasis, or gallstone formation, is one of the most prevalent disorders of the digestive system, with numerous causative factors, including family history, female sex, and lack of physical activity. PPI has been demonstrated to increase the occurrence of gallstone disease (Fukuba et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2021); further, intestinal flora also play a critical role in gallstone formation because of its corresponding influence on bile acid and cholesterol metabolism (Wang et al., 2020).

There are several known pathogenic mechanisms of PPI in cholelithiasis. First, the intestinal flora composition of mice chronically exposed to PPIs is comparable to that of mice fed with high-fat diet (Yang et al., 2020); importantly, a high-fat diet has been clearly identified as a risk factor for gallstone formation. Second, PPI use increases the abundance of producing bile salt hydrolase (BSH) bacteria, such as Lactobacillus and Clostridium. These bacteria play an important role in bile acid metabolism via the depolymerization of glycine or taurine from conjugated bile acid sterol cores; then, primary bile acids are metabolized to secondary bile acids by 7α-dehydroxylase (Foley et al., 2019). Elevated BSH activity causes an increase in secondary bile acids in the intestine, and some secondary bile acids, especially deoxycholic acid, can promote gallstone formation via enterohepatic circulation (Wang et al., 2020). Third, in the intestine, 7α-dehydroxylase is mainly produced by Clostridium and Eubacterium, which also increases their abundance and can contribute to gallstone formation by increasing secondary bile acid production (Jia et al., 2018). Finally, PPIs decrease cholecystokinin release by delaying gastric emptying, thereby attenuating gallbladder motility and delaying gallbladder emptying (Cahan et al., 2006). Long-term PPI use may also promote bile duct epithelial proliferation and bile duct epithelial micropapillary growth, resulting in focal bile duct stenosis and obstruction, which may also be associated with gallstone formation (Yang et al., 2020).

Although current clinical studies have demonstrated a correlation between PPIs and cholelithiasis, the specific effect of PPI-induced changes in the intestinal flora on cholelithiasis remains unclear. PPIs also cause the reduction of other bacteria that produce BSH, such as Bifidobacterium; however, studies on the direct impact of PPI on the activity of BSH and 7α-dehydroxylase are limited (Hu et al., 2022).

The relationship between PPIs and infectious diseases of the biliary system has been discussed in several clinical studies (Chuang et al., 2019; Min et al., 2019). The biliary system typically maintains a sterile environment with bile acids (D'Aldebert et al., 2009); however, a recent study proposes that there is a clear transfer of intestinal microorganisms to the biliary tract in patients with biliary tract diseases (An et al., 2022). Additionally, animal models of SIBO revealed that intestinal flora and metabolites can affect bile acid metabolism and cause biliary disease (Almeida et al., 2013); overall, this establishes a correlation between biliary system disease and the intestinal microbiota. In recent years, correlational studies of PPI and bile duct cancer have also been reported (Kamal et al., 2021); however, we believe that this effect is more likely indirectly caused by PPI-induced cholelithiasis and biliary tract infections.

Many studies on the effects of PPIs on cholelithiasis and biliary system diseases are retrospective analyses based on large-scale epidemiological databases that are prone to residual confounding factors. These confounding factors are derived from the limitations in the research methodology and are difficult to adjust. Therefore, a higher level of evidence, such as results from randomized controlled trials, is needed to clarify these findings. Due to the connection between the hepatobiliary system and the small intestine, alongside the important role of the intestinal flora in bile acid metabolism, the use of PPIs can potentially impact the biliary tract through the intestinal flora. Therefore, long-term PPIs users should remain vigilant about the health of their hepatobiliary system.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

IBD is a chronic inflammatory disease of the intestine that includes ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. The etiology of IBD is diverse, with genetic factors, environmental factors, intestinal flora disruption, and immune imbalance being identified as potentially risk factors (Zhang and Li, 2014). In particular, the intestinal flora in a transgenic mouse model of IBD showed an intestinal inflammatory response only when intestinal microbes were present, emphasizing the importance of the intestinal microbiota in IBD (Lloyd-Price et al., 2019). In recent years, several large population cohort studies have indicated a link between PPI use and the occurrence of IBD (Allin and Moayyedi, 2021; Lo et al., 2020; Xia et al., 2021) Further microbiota analysis have indicated a strong similarity between changes in the intestinal flora of patients with IBD and PPI participants, suggesting that the gut microbiota could play a significant role in PPI-induced IBD (Issa et al., 2007).

There are multiple potential mechanisms by which PPI use can induce IBD. First, PPI use increases the risk of intestinal bacterial infections, which are considered typical initiating events of IBD (Rivera-Chávez et al., 2016). Second, PPI treatment promotes the occurrence of CDAD, which is a common cause of IBD (Sokol et al., 2008). Third, the abundance of the protective bacteria Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is reduced in the intestine. Notably, in vitro and in vivo studies have shown that F. prausnitzii exhibits an anti-inflammatory effect; specifically, its metabolites possess the ability to inhibit NF-B activation and IL-8 secretion, which are strongly linked to intestinal inflammation. Thus, reducing the abundance of F. prausnitzii may result in a high risk of IBD relapse and a reduced duration of remission (Sokol et al., 2008; Rajca et al., 2014). Finally, The abundance of Lactobacillus reuteri is reduced following PPI use. L. reuteri has the ability to convert the histidine present in food to histamine. Then, histamine increases cAMP levels by activating histamine receptors (H2); next, cAMP inhibits downstream MEK/ERK–MAPK signaling via protein kinase A and suppresses the production of TNF-α, a key driving factor for chronic inflammation in IBD. Therefore, a decrease in Lactobacillus royi may also contribute to IBD development (Thomas et al., 2012). Furthermore, the relationship between bile acids and IBD has recently received significant attention (Lloyd-Price et al., 2019); in particular, deoxycholic acid has been observed at significantly low levels in patients with IBD but dramatically increases after treatment (Ding et al., 2020). Therefore, PPI-induced bile acid alterations may also be an influencing factor in PPI-associated IBD.

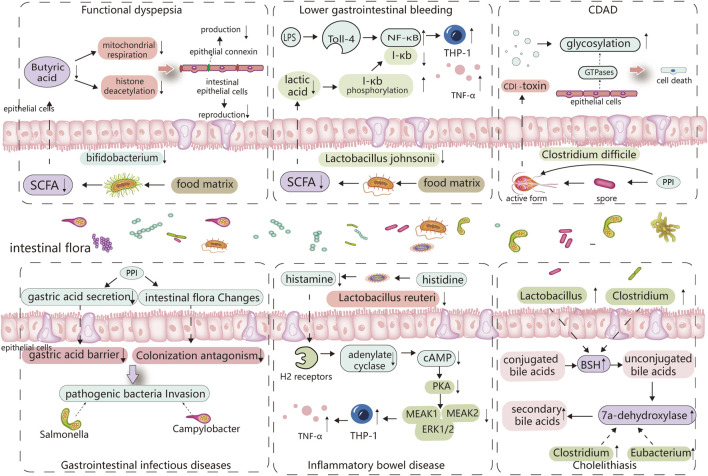

Numerous clinical studies have verified a correlation between PPIs and IBD. However, further cohort studies are required to strengthen these findings; additionally, more basic research is required to determine the primary pathophysiological mechanisms and the role of intestinal flora in PPI-induced IBD. In recent years, regular administration of probiotics, such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, has also been considered a potential method for preventing IBD (Manzoor et al., 2022), which further indicates the importance of the intestinal flora in IBD (Figure 2; Table 1).

FIGURE 2.

Major altered bacterial strains and possible pathogenesis in different PPI-induced digestive diseases. The altered gut microbiota caused by PPIs and its digestive side effects are inextricably linked, with certain strains of bacteria playing an important role. Reduced Bifidobacterium abundance limits the production of butyric acid, which is linked to the reproduction of intestinal epithelial cells and the synthesis of epithelial connexin. Butyric acid deficiency increases epithelial permeability and induces functional dyspepsia. Lactobacillus johnsonii is linked to the production of lactic acid, which can inhibit the phosphorylated degradation of I-κb and promote its binding to NF-κB, thereby inhibiting TNF-α release from monocytes cells, When the abundance of Lactobacillus johnsonii decreases, THP-1 cells produce more TNF-, which is linked to PPI-induced lower gastrointestinal bleeding. PPI directly promotes Clostridium difficile toxin expression, and elevated pH also stimulates Clostridium difficile spore germination, which is associated with C. difficile-associated diseases. PPI disrupts the gastric acid barrier and normal intestinal flora, allowing exogenous pathogenic bacteria to invade and cause gastrointestinal infectious diseases. Lactobacillus reuteri can convert histidine to histamine and activates H2 receptors, cause adenylate cyclase produce more cAMP, which through PKA restrains downstream MEK/ERK-MAPK signaling, inhibiting the production of TNF-α, thus delaying the incidence of IBD. So, Lactobacillus reuteri reduction promotes the occurrence of IBD. PPI increases the abundance of bacteria that produce 7a-dehydroxylase and bile salt hydrolase in the intestine, comprises Eubacterium, Clostridium, and Lactobacillus, thereby cause an increase in the synthesis of secondary bile acids, especially deoxycholic acid (LDA). These bile acids act as a lithogenic core and promote the development of cholelithiasis.

TABLE 1.

Major changed gut bacteria affected by PPI in different diseases.

| Disease | Changed flora | References |

|---|---|---|

| Functional dyspepsia | Bifidobacterium | Takashima, S |

| Streptococcus, Prevotella Veillonella, Actinomyces | Imhann, F | |

| Lactobacillus acidophilus | Kang, Y | |

| Lower gastrointestinal Bleeding | Lactobacillus johnsonii | Nadatani Y |

| actinomycetes | Wallace, J.L | |

| Lactobacillus casei | Endo, H | |

| Clostridium difficile associated diarrhea | Clostridium difficile | Nerandzic, M.M |

| Bacteroides, Firmicutes | Clooney, A.G | |

| Lactobacillus, yeast | Goldenberg, J.Z | |

| Gastrointestinal infectious Diseases | Salmonella | Wu, H.H |

| campylobacter | Doorduyn, Y | |

| Candida | Mottaghi, B | |

| Vancomyc inresistant enterococci | Willems, R.P.J | |

| Escherichia coli | Nakamura, A | |

| Cholelithiasis | Lactobacillus, Clostridium | Foley, M.H |

| Eubacterium | Jia, W | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Faecalibacterium prausnitzii | Sokol, H |

| Lactobacillus reuteri | Thomas, C.M |

Discussion

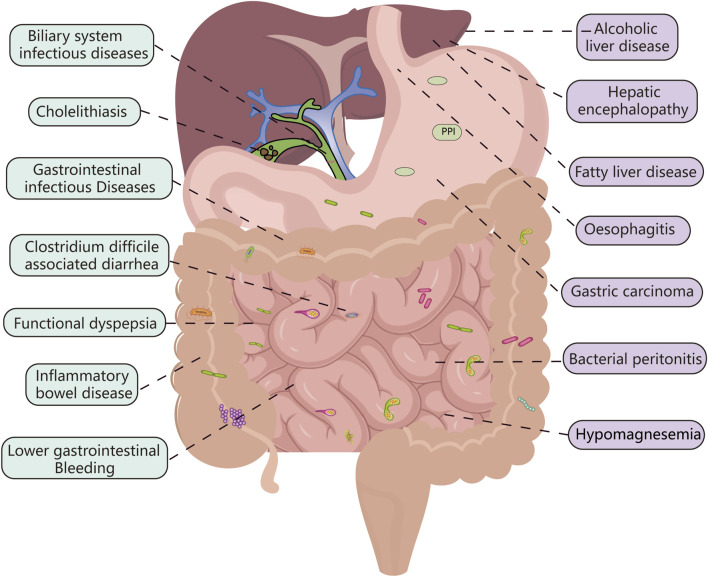

Over the past decade, there has been an overwhelming amount of literature on the adverse digestive effects of PPI use; further, several studies have highlighted the significant role of the intestinal flora in the relationship between PPI and the digestive system. However, there is a lack of comprehensive literature regarding the role of the gut microbiota in PPI-related digestive complications. In this review, we evaluated the overall changes to the intestinal flora alongside variations to the specific strains within the microbiota and established their association with PPI-related digestive disorders whilst detailing all possible mechanisms of action involved in this relationship (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

PPI-related digestive diseases: the connection between the green-labeled diseases and the intestinal flora is more obvious, while the purple-labeled diseases require more research.

The PPI-mediated alteration of bacterial metabolites, such as SCFAs, lactic acid and histamine, is a crucial mechanism in the development of certain digestive complications. For example, SCFAs, which are mainly produced by Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus species, are related to intestinal permeability, immunity, and hormones (Dalile et al., 2019). Among these SCFAs, butyrate can directly affect other intestinal bacteria via cross-feeding (Koh et al., 2016). (Huang et al., 2020). This may explain the association between PPIs and FD, intestinal infectious diseases, and CDAD. Emerging evidence suggests that SCFAs play critical roles in various digestive diseases. However, the precise effect of PPI on SCFA production is unknown; therefore, further research into the SCFAs produced by PPI-associated bacteria may be helpful in understanding the relationship between intestinal flora and PPI-related digestive complications. Moreover, PPIs can disrupt the gastric acid barrier and intestinal microecology and cause exogenous bacterial invasion, which can lead to infectious diseases of the gastrointestinal and biliary tracts and SIBO. PPIs can also directly affect pathogenic bacteria, such as C. difficile, which results in CDAD; however, this is a rare phenomenon.

The intestinal flora also plays an important role in other PPI-mediated diseases. Disruption of the gut microbiota affects the fermentation of the intestinal contents, resulting in hypomagnesemia (Thongon and Krishnamra, 2012; William and Danziger, 2016). Additionally, an increase in the abundances of Proteobacteria and Streptococcus species has been linked to the development of rheumatoid arthritis (Imhann et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2021). Other related diseases include gastric cancer (Lofgren et al., 2011), bacterial peritonitis (Preto-Zamperlini et al., 2014; Wellhöner et al., 2019), hepatic encephalopathy (Bian et al., 2017; Tsai et al., 2017), and alcoholic fatty liver (Llorente et al., 2017; Pyo et al., 2021).

Specifying the advantages and disadvantages of PPI use for each individual patient may be considered the greatest limitation in the effective use of PPIs. Although current studies have found numerous PPI-related side effects, the evidence for most of these studies is relatively weak. In the majority of these studies, the associations are of a small magnitude; additionally, some conclusion are inconsistent with other studies and lack a rational explanation of the corresponding mechanisms. Further, few studies reporting the adverse events of PPIs have attempted to balance the corresponding benefits of PPI use with its purported harm. It is important to remain vigilant regarding the potential PPI-related digestive adverse effects. However, in clinical practice, it is important to carefully evaluate and individually manage patients who require PPI therapy to avoid long-term abuse. This may greatly reduce the likelihood of the related adverse reactions observed in these studies.

The large number of human and animal studies summarized in this review support the link between intestinal flora disruption and PPI-related digestive complications, indicating that the gut microbiota might be a promising target for the prevention and treatment of related diseases. Fecal microbiota transplantation, as a method of re-establishing intestinal microecology, can be effective in certain PPI-related digestive diseases, such as FD and CDAD. Alternatively, some probiotics, such as Lactobacillus, have also been used to prevent lower gastrointestinal bleeding. However, more probiotics need to be identified and their roles in PPI-related digestive complications need to be explored further. In addition, more in vivo and in vitro studies are needed to further establish the mechanisms and molecular targets of the gut microbiota in these diseases. Addressing these identified gaps in knowledge should be a priority in future studies.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Professor Jianye Dai (Faculty of Pharmacy, Lanzhou University) and Professor Bin Luo (Faculty of Public Health, Lanzhou University) for help in quality of figures and article structure.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32160255); the Natural Science Foundation of Gansu Province: (22JR5RA898). Medical Innovation and Development Project of Lanzhou University (lzuyxcx-2022-157).

Author contributions

LT contributed to the conception and design of this work, and wrote and revised the manuscript. MB, CH, and CZ provided guidance on the organization and content of the manuscript. LT, WF, and YLu contributed to make table. LT, HM, NJ, and YLi helped in preparation of the figures. NM, LG, JZ, XZ, and PY helped to revise the structure and language of the manuscript. JY and WM provided guidance, edited and revised the manuscript, and is responsible for all aspects of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Adike A., DiBaise J. K. (2018). Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: Nutritional implications, diagnosis, and management. Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am. 47 (1), 193–208. 10.1016/j.gtc.2017.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar A. J., Shaheen M. (2007). Increasing incidence of clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in african-American and hispanic patients: Association with the use of proton pump inhibitor therapy. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 99 (5), 500–504. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allin K. H., Moayyedi P. (2021). Proton pump inhibitor use: A risk factor for inflammatory bowel disease or an innocent bystander? Gastroenterology 161 (6), 1789–1791. 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida J. A., Liu Y., Song M., Lee J. J., Gaskins H. R., Maddox C. W., et al. (2013). Escherichia coli challenge and one type of smectite alter intestinal barrier of pigs. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 4 (1), 52. 10.1186/2049-1891-4-52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An C., Chon H., Ku W., Eom S., Seok M., Kim S., et al. (2022). Bile acids: Major regulator of the gut microbiome. Microorganisms 10 (9), 1792. 10.3390/microorganisms10091792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archimandritis A., Souyioultzis S., Katsorida M., Tzivras M. (1998). Clostridium difficile colitis associated with a 'triple' regimen, containing clarithromycin and metronidazole, to eradicate Helicobacter pylori . J. Intern Med. 243 (3), 251–253. 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1998.00272.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermudez-Brito M., Plaza-Díaz J., Muñoz-Quezada S., Gómez-Llorente C., Gil A. (2012). Probiotic mechanisms of action. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 61 (2), 160–174. 10.1159/000342079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian J., Wang A., Lin J., Wu L., Huang H., Wang S., et al. (2017). Association between proton pump inhibitors and hepatic encephalopathy: A meta-analysis. Med. Baltim. 96 (17), e6723. 10.1097/md.0000000000006723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broecker F., Klumpp J., Schuppler M., Russo G., Biedermann L., Hombach M., et al. (2016). Long-term changes of bacterial and viral compositions in the intestine of a recovered Clostridium difficile patient after fecal microbiota transplantation. Cold Spring Harb. Mol. Case Stud. 2 (1), a000448. 10.1101/mcs.a000448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahan M. A., Balduf L., Colton K., Palacioz B., McCartney W., Farrell T. M. (2006). Proton pump inhibitors reduce gallbladder function. Surg. Endosc. 20 (9), 1364–1367. 10.1007/s00464-005-0247-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canny G. O., McCormick B. A. (2008). Bacteria in the intestine, helpful residents or enemies from within? Infect. Immun. 76 (8), 3360–3373. 10.1128/iai.00187-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang S. C., Lin C. C., Peng C. Y., Huang W. H., Su W. P., Lai S. W., et al. (2019). Proton pump inhibitors increase the risk of cholecystitis: A population-based case-control study. Gut 68 (7), 1337–1339. 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clooney A. G., Bernstein C. N., Leslie W. D., Vagianos K., Sargent M., Laserna-Mendieta E. J., et al. (2016). A comparison of the gut microbiome between long-term users and non-users of proton pump inhibitors. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 43 (9), 974–984. 10.1111/apt.13568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins S. M. (2014). A role for the gut microbiota in IBS. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 11 (8), 497–505. 10.1038/nrgastro.2014.40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham R., Mustoe E., Spiller L., Lewis S., Benjamin N. (2014). Acidified nitrite: A host defence against colonization with C. difficile spores? J. Hosp. Infect. 86 (2), 155–157. 10.1016/j.jhin.2013.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Aldebert E., Biyeyeme Bi Mve M. J., Mergey M., Wendum D., Firrincieli D., Coilly A., et al. (2009). Bile salts control the antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin through nuclear receptors in the human biliary epithelium. Gastroenterology 136 (4), 1435–1443. 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalile B., Van Oudenhove L., Vervliet B., Verbeke K. (2019). The role of short-chain fatty acids in microbiota-gut-brain communication. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 16 (8), 461–478. 10.1038/s41575-019-0157-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dial S., Alrasadi K., Manoukian C., Huang A., Menzies D. (2004). Risk of Clostridium difficile diarrhea among hospital inpatients prescribed proton pump inhibitors: Cohort and case-control studies. Cmaj 171 (1), 33–38. 10.1503/cmaj.1040876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding N. S., McDonald J. A. K., Perdones-Montero A., Rees D. N., Adegbola S. O., Misra R., et al. (2020). Metabonomics and the gut microbiome associated with primary response to anti-TNF therapy in Crohn's disease. J. Crohns Colitis 14 (8), 1090–1102. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doorduyn Y., Van Den Brandhof W. E., Van Duynhoven Y. T., Breukink B. J., Wagenaar J. A., Van Pelt W. (2010). Risk factors for indigenous Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli infections in The Netherlands: A case-control study. Epidemiol. Infect. 138 (10), 1391–1404. 10.1017/s095026881000052x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo H., Higurashi T., Hosono K., Sakai E., Sekino Y., Iida H., et al. (2011). Efficacy of Lactobacillus casei treatment on small bowel injury in chronic low-dose aspirin users: A pilot randomized controlled study. J. Gastroenterol. 46 (7), 894–905. 10.1007/s00535-011-0410-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engevik M. A., Luk B., Chang-Graham A. L., Hall A., Herrmann B., Ruan W., et al. (2019). Bifidobacterium dentium fortifies the intestinal mucus layer via autophagy and calcium signaling pathways. mBio 10 (3), 010877–e1119. 10.1128/mBio.01087-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein M., McGrath S., Law F. (2006). Proton-pump inhibitors and hypomagnesemic hypoparathyroidism. N. Engl. J. Med. 355 (17), 1834–1836. 10.1056/NEJMc066308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdogan A., Rao S. S., Gulley D., Jacobs C., Lee Y. Y., Badger C. (2015). Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: Duodenal aspiration vs glucose breath test. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 27 (4), 481–489. 10.1111/nmo.12516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint H. J., Scott K. P., Louis P., Duncan S. H. (2012). The role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 9 (10), 577–589. 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley M. H., O'Flaherty S., Barrangou R., Theriot C. M. (2019). Bile salt hydrolases: Gatekeepers of bile acid metabolism and host-microbiome crosstalk in the gastrointestinal tract. PLoS Pathog. 15 (3), e1007581. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley S. L., Johnson T. J., Ricke S. C., Nayak R., Danzeisen J. (2013). Salmonella pathogenicity and host adaptation in chicken-associated serovars. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 77 (4), 582–607. 10.1128/mmbr.00015-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford A. C., Mahadeva S., Carbone M. F., Lacy B. E., Talley N. J. (2020). Functional dyspepsia. Lancet 396 (10263), 1689–1702. 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30469-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedberg D. E., Kim L. S., Yang Y. X. (2017). The risks and benefits of long-term use of proton pump inhibitors: Expert review and best practice advice from the American gastroenterological association. Gastroenterology 152 (4), 706–715. 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedberg D. E., Lebwohl B., Abrams J. A. (2014). The impact of proton pump inhibitors on the human gastrointestinal microbiome. Clin. Lab. Med. 34 (4), 771–785. 10.1016/j.cll.2014.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried M., Siegrist H., Frei R., Froehlich F., Duroux P., Thorens J., et al. (1994). Duodenal bacterial overgrowth during treatment in outpatients with omeprazole. Gut 35 (1), 23–26. 10.1136/gut.35.1.23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuba N., Ishihara S., Sonoyama H., Yamashita N., Aimi M., Mishima Y., et al. (2017). Proton pump inhibitor is a risk factor for recurrence of common bile duct stones after endoscopic sphincterotomy - propensity score matching analysis. Endosc. Int. Open 5 (4), E291–e296. 10.1055/s-0043-102936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Rodríguez L. A., Ruigómez A. (1997). Gastric acid, acid-suppressing drugs, and bacterial gastroenteritis: How much of a risk? Epidemiology 8 (5), 571–574. 10.1097/00001648-199709000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García Rodríguez L. A., Ruigómez A., Panés J. (2007). Use of acid-suppressing drugs and the risk of bacterial gastroenteritis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 5 (12), 1418–1423. 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert J. A., Blaser M. J., Caporaso J. G., Jansson J. K., Lynch S. V., Knight R. (2018). Current understanding of the human microbiome. Nat. Med. 24 (4), 392–400. 10.1038/nm.4517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg J. Z., Yap C., Lytvyn L., Lo C. K., Beardsley J., Mertz D., et al. (2017). Probiotics for the prevention of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 12 (12), Cd006095. 10.1002/14651858.CD006095.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassing R. J., Verbon A., de Visser H., Hofman A., Stricker B. H. (2016). Proton pump inhibitors and gastroenteritis. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 31 (10), 1057–1063. 10.1007/s10654-016-0136-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S. H., Lee E. K., Shin J. Y. (2019). Proton-pump inhibitors and the risk of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in high-risk antibiotics users: A population-based case-crossover study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 28 (4), 479–488. 10.1002/pds.4745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins J., Alborn W. E., Jr., Arnold J., Blaszczak L. C., Burgett S., DeHoff B. S., et al. (2001). Genome of the bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae strain R6. J. Bacteriol. 183 (19), 5709–5717. 10.1128/jb.183.19.5709-5717.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H., Shao W., Liu Q., Liu N., Wang Q., Xu J., et al. (2022). Gut microbiota promotes cholesterol gallstone formation by modulating bile acid composition and biliary cholesterol secretion. Nat. Commun. 13 (1), 252. 10.1038/s41467-021-27758-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W., Man Y., Gao C., Zhou L., Gu J., Xu H., et al. (2020). Short-chain fatty acids ameliorate diabetic nephropathy via GPR43-mediated inhibition of oxidative stress and NF-κB signaling. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 4074832. 10.1155/2020/4074832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung Y. P., Lee J. C., Tsai B. Y., Wu J. L., Liu H. C., Liu H. C., et al. (2021). Risk factors of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in hospitalized adults: Vary by hospitalized duration. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 54 (2), 276–283. 10.1016/j.jmii.2019.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imhann F., Bonder M. J., Vich Vila A., Fu J., Mujagic Z., Vork L., et al. (2016). Proton pump inhibitors affect the gut microbiome. Gut 65 (5), 740–748. 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issa M., Vijayapal A., Graham M. B., Beaulieu D. B., Otterson M. F., Lundeen S., et al. (2007). Impact of Clostridium difficile on inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 5 (3), 345–351. 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.12.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia W., Xie G., Jia W. (2018). Bile acid-microbiota crosstalk in gastrointestinal inflammation and carcinogenesis. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 15 (2), 111–128. 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen J., Mortensen P. B. (2000). Utilization of short-chain fatty acids by colonic mucosal tissue strips. A new method of assessing colonic mucosal metabolism. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 35 (6), 659–666. 10.1080/003655200750023651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamal H., Sadr-Azodi O., Engstrand L., Brusselaers N. (2021). Association between proton pump inhibitor use and biliary tract cancer risk: A Swedish population-based cohort study. Hepatology 74 (4), 2021–2031. 10.1002/hep.31914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y., Kang X., Yang H., Liu H., Yang X., Liu Q., et al. (2022). Lactobacillus acidophilus ameliorates obesity in mice through modulation of gut microbiota dysbiosis and intestinal permeability. Pharmacol. Res. 175, 106020. 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.106020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly C. P., LaMont J. T. (1998). Clostridium difficile infection. Annu. Rev. Med. 49, 375–390. 10.1146/annurev.med.49.1.375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. W., Jeong Y., Park S. J., Jin H., Lee J., Ju J. H., et al. (2021). Influence of proton pump inhibitor or rebamipide use on gut microbiota of rheumatoid arthritis patients. Rheumatol. Oxf. 60 (2), 708–716. 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh A., De Vadder F., Kovatcheva-Datchary P., Bäckhed F. (2016). From dietary fiber to host physiology: Short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell. 165 (6), 1332–1345. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorente C., Jepsen P., Inamine T., Wang L., Bluemel S., Wang H. J., et al. (2017). Gastric acid suppression promotes alcoholic liver disease by inducing overgrowth of intestinal Enterococcus. Nat. Commun. 8 (1), 837. 10.1038/s41467-017-00796-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Price J., Arze C., Ananthakrishnan A. N., Schirmer M., Avila-Pacheco J., Poon T. W., et al. (2019). Multi-omics of the gut microbial ecosystem in inflammatory bowel diseases. Nature 569 (7758), 655–662. 10.1038/s41586-019-1237-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo C. H., Lochhead P., Khalili H., Song M., Tabung F. K., Burke K. E., et al. (2020). Dietary inflammatory potential and risk of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 159 (3), 873–883.e1. 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo W. K., Chan W. W. (2013). Proton pump inhibitor use and the risk of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: A meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 11 (5), 483–490. 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lofgren J. L., Whary M. T., Ge Z., Muthupalani S., Taylor N. S., Mobley M., et al. (2011). Lack of commensal flora in Helicobacter pylori-infected INS-GAS mice reduces gastritis and delays intraepithelial neoplasia. Gastroenterology 140 (1), 210–220. 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.09.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malfertheiner P., Kandulski A., Venerito M. (2017). Proton-pump inhibitors: Understanding the complications and risks. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 14 (12), 697–710. 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzoor S., Wani S. M., Ahmad Mir S., Rizwan D. (2022). Role of probiotics and prebiotics in mitigation of different diseases. Nutrition 96, 111602. 10.1016/j.nut.2022.111602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Gallausiaux C., Marinelli L., Blottière H. M., Larraufie P., Lapaque N. (2021). Scfa: Mechanisms and functional importance in the gut. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 80 (1), 37–49. 10.1017/s0029665120006916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinsen T. C., Fossmark R., Waldum H. L. (2019). The phylogeny and biological function of gastric juice-microbiological consequences of removing gastric acid. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20 (23), 6031. 10.3390/ijms20236031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masanta W. O., Heimesaat M. M., Bereswill S., Tareen A. M., Lugert R., Groß U., et al. (2013). Modification of intestinal microbiota and its consequences for innate immune response in the pathogenesis of campylobacteriosis. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2013, 526860. 10.1155/2013/526860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott A. J., Huffnagle G. B. (2014). The microbiome and regulation of mucosal immunity. Immunology 142 (1), 24–31. 10.1111/imm.12231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melchers K., Herrmann L., Mauch F., Bayle D., Heuermann D., Weitzenegger T., et al. (1998). Properties and function of the P type ion pumps cloned from Helicobacter pylori . Acta Physiol. Scand. Suppl. 643, 123–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min Y. W., Kang D., Shin J. Y., Kang M., Park J. K., Lee K. H., et al. (2019). Use of proton pump inhibitors and the risk of cholangitis: A nationwide cohort study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 50 (7), 760–768. 10.1111/apt.15466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moayyedi P., Lacy B. E., Andrews C. N., Enns R. A., Howden C. W., Vakil N. (2017). ACG and CAG clinical guideline: Management of dyspepsia. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 112 (7), 988–1013. 10.1038/ajg.2017.154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molloy M. J., Bouladoux N., Belkaid Y. (2012). Intestinal microbiota: Shaping local and systemic immune responses. Semin. Immunol. 24 (1), 58–66. 10.1016/j.smim.2011.11.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison D. J., Preston T. (2016). Formation of short chain fatty acids by the gut microbiota and their impact on human metabolism. Gut Microbes 7 (3), 189–200. 10.1080/19490976.2015.1134082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mottaghi B., Emami M. H., Riahi P., Fahim A., Rahimi H., Mohammadi R. (2021). Candida colonization of the esophagus and gastric mucosa; a comparison of patients taking proton pump inhibitors and those taking histamine receptor antagonist drugs. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench 14 (4), 349–355. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadatani Y., Watanabe T., Suda W., Nakata A., Matsumoto Y., Kosaka S., et al. (2019). Gastric acid inhibitor aggravates indomethacin-induced small intestinal injury via reducing Lactobacillus johnsonii. Sci. Rep. 9 (1), 17490. 10.1038/s41598-019-53559-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata N., Niikura R., Aoki T., Sakurai T., Moriyasu S., Shimbo T., et al. (2015). Effect of proton-pump inhibitors on the risk of lower gastrointestinal bleeding associated with NSAIDs, aspirin, clopidogrel, and warfarin. J. Gastroenterol. 50 (11), 1079–1086. 10.1007/s00535-015-1055-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura A., Komatsu M., Ohno Y., Noguchi N., Kondo A., Hatano N. (2019). Identification of specific protein amino acid substitutions of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli ST131: A proteomics approach using mass spectrometry. Sci. Rep. 9 (1), 8555. 10.1038/s41598-019-45051-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nerandzic M. M., Pultz M. J., Donskey C. J. (2009). Examination of potential mechanisms to explain the association between proton pump inhibitors and Clostridium difficile infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53 (10), 4133–4137. 10.1128/aac.00252-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng L., Li Z. R., Green R. S., Holzman I. R., Lin J. (2009). Butyrate enhances the intestinal barrier by facilitating tight junction assembly via activation of AMP-activated protein kinase in Caco-2 cell monolayers. J. Nutr. 139 (9), 1619–1625. 10.3945/jn.109.104638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pépin J., Saheb N., Coulombe M. A., Alary M. E., Corriveau M. P., Authier S., et al. (2005). Emergence of fluoroquinolones as the predominant risk factor for Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea: A cohort study during an epidemic in quebec. Clin. Infect. Dis. 41 (9), 1254–1260. 10.1086/496986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry I. E., Sonu I., Scarpignato C., Akiyama J., Hongo M., Vega K. J. (2020). Potential proton pump inhibitor-related adverse effects. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1481 (1), 43–58. 10.1111/nyas.14428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel M., Saad R. J., Long M. D., Rao S. S. C. (2020). ACG clinical guideline: Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 115 (2), 165–178. 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poutanen S. M., Simor A. E. (2004). Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in adults. Cmaj 171 (1), 51–58. 10.1503/cmaj.1031189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preto-Zamperlini M., Farhat S. C., Perondi M. B., Pestana A. P., Cunha P. S., Pugliese R. P., et al. (2014). Elevated C-reactive protein and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in children with chronic liver disease and ascites. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 58 (1), 96–98. 10.1097/mpg.0000000000000177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyo J. H., Kim T. J., Lee H., Choi S. C., Cho S. J., Choi Y. H., et al. (2021). Proton pump inhibitors use and the risk of fatty liver disease: A nationwide cohort study. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 36 (5), 1235–1243. 10.1111/jgh.15236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajca S., Grondin V., Louis E., Vernier-Massouille G., Grimaud J. C., Bouhnik Y., et al. (2014). Alterations in the intestinal microbiome (dysbiosis) as a predictor of relapse after infliximab withdrawal in Crohn's disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 20 (6), 978–986. 10.1097/mib.0000000000000036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao S. S. C., Bhagatwala J. (2019). Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: Clinical features and therapeutic management. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 10 (10), e00078. 10.14309/ctg.0000000000000078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Chávez F., Zhang L. F., Faber F., Lopez C. A., Byndloss M. X., Olsan E. E., et al. (2016). Depletion of butyrate-producing clostridia from the gut microbiota drives an aerobic luminal expansion of Salmonella. Cell. Host Microbe 19 (4), 443–454. 10.1016/j.chom.2016.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs G., Shin J. M., Howden C. W. (2006). Review article: The clinical pharmacology of proton pump inhibitors. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 23 (2), 2–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02943.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatz R. A., Zhang Q., Lodhia N., Shuster J., Toskes P. P., Moshiree B. (2015). Predisposing factors for positive D-xylose breath test for evaluation of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: A retrospective study of 932 patients. World J. Gastroenterol. 21 (15), 4574–4582. 10.3748/wjg.v21.i15.4574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sender R., Fuchs S., Milo R. (2016). Are we really vastly outnumbered? Revisiting the ratio of bacterial to host cells in humans. Cell. 164 (3), 337–340. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah A., Talley N. J., Jones M., Kendall B. J., Koloski N., Walker M. M., et al. (2020). Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 115 (2), 190–201. 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y. C., Cai S. T., Tian Y. P., Zhao H. J., Zhang Y. B., Chen J., et al. (2019). Effects of proton pump inhibitors on the gastrointestinal microbiota in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Genomics Proteomics Bioinforma. 17 (1), 52–63. 10.1016/j.gpb.2018.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J. M., Kim N. (2013). Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the proton pump inhibitors. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 19 (1), 25–35. 10.5056/jnm.2013.19.1.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokol H., Pigneur B., Watterlot L., Lakhdari O., Bermúdez-Humarán L. G., Gratadoux J. J., et al. (2008). Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105 (43), 16731–16736. 10.1073/pnas.0804812105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song T., Jeon H. K., Hong J. E., Choi J. J., Kim T. J., Choi C. H., et al. (2017). Proton pump inhibition enhances the cytotoxicity of paclitaxel in cervical cancer. Cancer Res. Treat. 49 (3), 595–606. 10.4143/crt.2016.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart D. B., Hegarty J. P. (2013). Correlation between virulence gene expression and proton pump inhibitors and ambient pH in Clostridium difficile: Results of an in vitro study. J. Med. Microbiol. 62 (10), 1517–1523. 10.1099/jmm.0.059709-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su T., Lai S., Lee A., He X., Chen S. (2018). Meta-analysis: Proton pump inhibitors moderately increase the risk of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. J. Gastroenterol. 53 (1), 27–36. 10.1007/s00535-017-1371-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takakura W., Pimentel M. (2020). Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and irritable bowel syndrome - an update. Front. Psychiatry 11, 664. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takashima S., Tanaka F., Kawaguchi Y., Usui Y., Fujimoto K., Nadatani Y., et al. (2020). Proton pump inhibitors enhance intestinal permeability via dysbiosis of gut microbiota under stressed conditions in mice. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 32 (7), e13841. 10.1111/nmo.13841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas C. M., Hong T., van Pijkeren J. P., Hemarajata P., Trinh D. V., Hu W., et al. (2012). Histamine derived from probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri suppresses TNF via modulation of PKA and ERK signaling. PLoS One 7 (2), e31951. 10.1371/journal.pone.0031951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thongon N., Krishnamra N. (2012). Apical acidity decreases inhibitory effect of omeprazole on Mg(2+) absorption and claudin-7 and -12 expression in Caco-2 monolayers. Exp. Mol. Med. 44 (11), 684–693. 10.3858/emm.2012.44.11.077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga K., Higuchi K., Iketani T., Ochi M., Kadouchi K., Tanigawa T., et al. (2007). Comparison of gastrointestinal symptoms and psychological factors of functional dyspepsia to peptic ulcer or panic disorder patients. Inflammopharmacology 15 (2), 84–89. 10.1007/s10787-006-0011-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai C. F., Chen M. H., Wang Y. P., Chu C. J., Huang Y. H., Lin H. C., et al. (2017). Proton pump inhibitors increase risk for hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis in A population study. Gastroenterology 152 (1), 134–141. 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukuda N., Yahagi K., Hara T., Watanabe Y., Matsumoto H., Mori H., et al. (2021). Key bacterial taxa and metabolic pathways affecting gut short-chain fatty acid profiles in early life. Isme J. 15 (9), 2574–2590. 10.1038/s41396-021-00937-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uejima M., Kinouchi T., Kataoka K., Hiraoka I., Ohnishi Y. (1996). Role of intestinal bacteria in ileal ulcer formation in rats treated with a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug. Microbiol. Immunol. 40 (8), 553–560. 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1996.tb01108.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urita Y., Sugimoto M., Hike K., Torii N., Kikuchi Y., Kurakata H., et al. (2006). High incidence of fermentation in the digestive tract in patients with reflux oesophagitis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 18 (5), 531–535. 10.1097/00042737-200605000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanheel H., Vicario M., Vanuytsel T., Van Oudenhove L., Martinez C., Keita Å V., et al. (2014). Impaired duodenal mucosal integrity and low-grade inflammation in functional dyspepsia. Gut 63 (2), 262–271. 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vesper B. J., Jawdi A., Altman K. W., Haines G. K., Tao L., Radosevich J. A. (2009). The effect of proton pump inhibitors on the human microbiota. Curr. Drug Metab. 10 (1), 84–89. 10.2174/138920009787048392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace J. L., Syer S., Denou E., de Palma G., Vong L., McKnight W., et al. (2011). Proton pump inhibitors exacerbate NSAID-induced small intestinal injury by inducing dysbiosis. Gastroenterology 141 (4), 1314–1322. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K., Lin H. J., Perng C. L., Tseng G. Y., Yu K. W., Chang F. Y., et al. (2004). The effect of H2-receptor antagonist and proton pump inhibitor on microbial proliferation in the stomach. Hepatogastroenterology 51 (59), 1540–1543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Hao C., Yao W., Zhu D., Lu H., Li L., et al. (2020). Intestinal flora imbalance affects bile acid metabolism and is associated with gallstone formation. BMC Gastroenterol. 20 (1), 59. 10.1186/s12876-020-01195-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washio E., Esaki M., Maehata Y., Miyazaki M., Kobayashi H., Ishikawa H., et al. (2016). Proton pump inhibitors increase incidence of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced small bowel injury: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 14 (6), 809–815. 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T., Nishio H., Tanigawa T., Yamagami H., Okazaki H., Watanabe K., et al. (2009). Probiotic Lactobacillus casei strain shirota prevents indomethacin-induced small intestinal injury: Involvement of lactic acid. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 297 (3), G506–G513. 10.1152/ajpgi.90553.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T., Sugimori S., Kameda N., Machida H., Okazaki H., Tanigawa T., et al. (2008). Small bowel injury by low-dose enteric-coated aspirin and treatment with misoprostol: A pilot study. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 6 (11), 1279–1282. 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitsman S., Celly S., Leite G., Mathur R., Sedighi R., Barlow G. M., et al. (2022). Effects of proton pump inhibitors on the small bowel and stool microbiomes. Dig. Dis. Sci. 67 (1), 224–232. 10.1007/s10620-021-06857-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellhöner F., Döscher N., Tergast T. L., Vital M., Plumeier I., Kahl S., et al. (2019). The impact of proton pump inhibitors on the intestinal microbiota in chronic hepatitis C patients. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 54 (8), 1033–1041. 10.1080/00365521.2019.1647280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetzel D., McBride S. M. (2020). The impact of pH on clostridioides difficile sporulation and physiology. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 86 (4), e02706–e02719. 10.1128/aem.02706-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willems R. P. J., van Dijk K., Ket J. C. F., Vandenbroucke-Grauls C. (2020). Evaluation of the association between gastric acid suppression and risk of intestinal colonization with multidrug-resistant microorganisms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 180 (4), 561–571. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- William J. H., Danziger J. (2016). Proton-pump inhibitor-induced hypomagnesemia: Current research and proposed mechanisms. World J. Nephrol. 5 (2), 152–157. 10.5527/wjn.v5.i2.152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H. H., Chen Y. T., Shih C. J., Lee Y. T., Kuo S. C., Chen T. L. (2014). Association between recent use of proton pump inhibitors and nontyphoid salmonellosis: A nested case-control study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 59 (11), 1554–1558. 10.1093/cid/ciu628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia B., Yang M., Nguyen L. H., He Q., Zhen J., Yu Y., et al. (2021). Regular use of proton pump inhibitor and the risk of inflammatory bowel disease: Pooled analysis of 3 prospective cohorts. Gastroenterology 161 (6), 1842–1852. 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M., Xia B., Lu Y., He Q., Lin Y., Yue P., et al. (2021). Association between regular use of gastric acid suppressants and subsequent risk of cholelithiasis: A prospective cohort study of 0.47 million participants. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 813587. 10.3389/fphar.2021.813587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y. S. H., Chang H. W., Lin I. H., Chien L. N., Wu M. J., Liu Y. R., et al. (2020). Long-term proton pump inhibitor administration caused physiological and microbiota changes in rats. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 866. 10.1038/s41598-020-57612-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y. X., Metz D. C. (2010). Safety of proton pump inhibitor exposure. Gastroenterology 139 (4), 1115–1127. 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. Z., Li Y. Y. (2014). Inflammatory bowel disease: Pathogenesis. World J. Gastroenterol. 20 (1), 91–99. 10.3748/wjg.v20.i1.91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W., Caro F., Robins W., Mekalanos J. J. (2018). Antagonism toward the intestinal microbiota and its effect on Vibrio cholerae virulence. Science 359 (6372), 210–213. 10.1126/science.aap8775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong L., Shanahan E. R., Raj A., Koloski N. A., Fletcher L., Morrison M., et al. (2017). Dyspepsia and the microbiome: Time to focus on the small intestine. Gut 66 (6), 1168–1169. 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]