Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is associated with a substantial clinical and economic burden. Inhaled prostacyclins are a well-established part of pharmacotherapy for PAH. There are differences between inhaled therapies in the burden imposed by administration frequency. Simpler and less time-consuming inhaled PAH therapies may improve both adherence and persistence and potentially affect outcomes.

OBJECTIVES:

To compare real-world health care resource use, costs, and treatment adherence and persistence in patients with PAH who initiated inhaled treprostinil or iloprost.

METHODS:

Adult patients with 1 inpatient or 2 outpatient medical claims separated by at least 30 days with a diagnosis of PAH were identified using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision or Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification codes with a pharmacy claim for inhaled treprostinil or iloprost. Patients were required to be continuously enrolled in the health plan for 6 months prior to and 12 months after the index date. A proportion of days covered of 0.8 or more was considered adherent; persistence was no gap in therapy for at least 60 days. All-cause health care resource utilization and all-cause costs were assessed.

RESULTS:

405 and 62 patients were included in the inhaled treprostinil and iloprost cohorts, respectively. Adherence (50.9% and 22.6%; P < 0.0001) and persistence (6 months, 65.2% vs 35.5%; 12 months, 46.7% vs 16.1%; log-rank P < 0.001) were significantly better with inhaled treprostinil. Post-index allcause inpatient admissions (39.3% vs 54.8%; P = 0.02) and post-index emergency department (ED) utilization (36.3% vs 50.0%; P = 0.04) were lower with inhaled treprostinil. Among patients who were persistent with therapy through 12 months, there was no significant difference between groups in mean (SD) all-cause total costs ($266,462 [137,324] vs $262,826 [112,452] for inhaled treprostinil vs iloprost, respectively; P = 0.98).

CONCLUSIONS:

The results suggest that inhaled treprostinil is less burdensome, is associated with greater adherence and persistence, and may reduce all-cause hospitalizations and ED visits.

Plain language summary

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a serious disease that may lead to early death. Inhaled therapies can be used to treat PAH. Inhaled treprostinil is taken 4 times a day and iloprost is taken 6 to 9 times a day. This study found users of inhaled treprostinil stayed on therapy longer and were hospitalized less than users of iloprost. This may be due to how these therapies are taken. Flesch-Kincaid Reading Level: 8.7.

Implications for managed care pharmacy

Inhaled treprostinil and iloprost are 2 established prostacyclin therapies for the treatment of PAH. A main difference between the products is the frequency of administration. Real-world evidence is lacking on pertinent outcomes of patients initiating these products. This study provides additional evidence when reviewing coverage and reimbursement decisions for patients with PAH.

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a severe and incurable pulmonary vascular disease characterized by progressive increases in pulmonary vascular resistance, right ventricular failure, and premature death.1 Claims data analyses (1999-2007) suggest that the prevalence of PAH in the United States is 109 per million overall and 451 per million among the Medicare population.2

Historically, the prognosis of PAH was poor, with a median survival of only 2.8 years from diagnosis in the absence of therapy.3 Today, agents from 5 approved classes of therapies that target the 3 different pathways integral to the pathophysiology of the disease are available. These therapies have demonstrated improvements in symptoms, exercise capacity, and in some studies, hemodynamic status. The availability of multiple drugs that may be used alone or in various combinations, early treatment initiation, and optimization of supportive and nonpharmacologic care have together extended median survival beyond 7 years from diagnosis.4

The prostacyclin analogues (epoprostenol, treprostinil, and iloprost) are an integral and well-established part of pharmacotherapy for PAH. These agents mimic endogenous prostacyclin, resulting in nonselective pulmonary vasodilation. They also have a range of antiplatelet, antithrombotic, and anti-inflammatory properties that may contribute to their effects.5 They are available in intravenous, subcutaneous, oral, and inhaled formulations.5

Currently, 2 inhaled prostacyclin analogues are approved in the United States for the management of PAH. Inhaled treprostinil is indicated for the treatment of patients with group 1 PAH with functional class III symptoms to improve exercise ability. After completion of the INCREASE clinical trial, it is also approved for use in patients with pulmonary hypertension associated with interstitial lung disease.6 Inhaled treprostinil is administered using a dedicated ultrasonic nebulizer. With an elimination half-life of approximately 4.5 hours, it is dosed in 4 separate, equally spaced treatment sessions per day during waking hours, with each session lasting 2 to 3 minutes.7 Iloprost is indicated for the treatment of PAH to improve a composite endpoint consisting of exercise tolerance, symptoms, and lack of deterioration. Iloprost has a half-life of approximately 20 to 30 minutes and is administered using a nebulizer 6 to 9 times daily, in treatment sessions lasting 4 to 10 minutes.8

Abundant data in multiple disease states indicate that the frequency and mode of administration of pharmacotherapies have a substantial impact on real-world long-term adherence and persistence with therapy, as well as on both short- and long-term treatment outcomes.9-11 Simplifying PAH treatment may be particularly important in the management of these often complex patients who frequently require concomitant treatments for multiple comorbidities.12 This study compared real-world health care resource use, costs, and treatment adherence and persistence in patients with PAH initiating inhaled treprostinil or inhaled iloprost.

Methods

STUDY DESIGN AND COHORT

This retrospective cohort study was conducted using medical and pharmacy claims from January 1, 2010, to September 30, 2020, using the Optum deidentified Clinformatics Data Mart, a nationwide, commercial, US managed health care database that includes adjudicated administrative claims for more than 65 million unique patients. The index date was defined as the date of the first pharmacy or medical claim for iloprost or inhaled treprostinil during the identification period from July 1, 2010, to September 30, 2019. Patients with a pharmacy claim for inhaled treprostinil or iloprost were identified based on National Drug Code numbers. Patients were also identified using medical claims for inhaled treprostinil or iloprost using Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes. Adult patients aged at least 18 years as of the index date and with 1 inpatient or 2 outpatient medical claims separated by at least 30 days with a diagnosis of PAH in the 6-month pre-index period were identified using the medical file. The PAH diagnosis was identified using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision Clinical Modification codes of 416.0, 416.8, or 416.9 or Tenth Revision codes of I27.0, I27.2, I27.20, I27.21, I27.29, I27.81, I27.83, I27.89, or I27.9.13 Patients were required to be continuously enrolled in the health plan for 6 months prior to and 12 months after the index date. Demographic, clinical, and other baseline characteristics collected for the pre-index period included age, sex, race, geographic region, payer type, PAH-specific therapies, Quan-Charlson Comorbidity Index (QCCI), and other select comorbidities.

MEASUREMENT OF HEALTH CARE RESOURCE UTILIZATION AND COSTS

Health care resource utilization included all inpatient and outpatient services, including emergency department (ED) admissions, physician office visits, and other outpatient services. Costs were reported from the payer perspective and included only paid amounts, excluding out-of-pocket costs and coordination of benefits. Twelve-month postindex medical costs included all inpatient admissions, ED visits, physician office visits, and other outpatient visits; post-index hospitalization costs were calculated using all inpatient admissions. Pharmacy costs were calculated using prescription claims. Total costs were reported as the sum of medical and pharmacy costs over the 12-month post-index period. All costs were adjusted to 2020 US dollars using the Consumer Price Index.

MEASUREMENT OF ADHERENCE AND PERSISTENCE

Adherence was measured using the proportion of days covered (PDC), in which the numerator was defined as the sum of total days supply for all fills and the denominator was the number of days in the follow-up period. Patients were considered adherent to therapy if they achieved a PDC of 0.8 or more. Persistence was defined as patients without a gap in therapy, in which the gap was defined by at least 60 days. Gaps were identified starting from the time period after each fill date plus days supply. As medical claims do not contain days supply, when iloprost and inhaled treprostinil were billed as a medical benefit, they were assumed to be 28 days for inhaled treprostinil and 30 days for iloprost, which is consistent with the packaging for the products.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

All study variables for demographics, clinical characteristics, PAH-specific medications, health care resource utilization, and costs were described using means, SDs, and/or medians and interquartile ranges for continuous variables. Numbers and percentages were reported for categorical variables. Categorical outcomes for the percentage of patients at or above a PDC threshold of 0.8 or 0.5 and the percentage of patients with a hospitalization or ED visit were compared between the 2 groups using chi-square tests or Fisher exact test. Continuous variables were compared using Student’s t-test after testing for normality.

Multivariable log binomial regression models were used to assess relative risk of any hospitalization in the post-index period and adjusted for age, sex, race, geographic region, coverage type, QCCI category, PAH medication regimen, and baseline hospitalizations. Kaplan-Meier curves were generated to assess time to nonpersistence, and log-rank tests were used to test for differences between the curves. A multivariable Cox proportional hazards model was used to generate hazard ratios and adjusted for the same baseline characteristics listed above. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 or higher (SAS Institute, Inc).

Results

COHORT SELECTION

A total of 1,093 patients who had used inhaled treprostinil or iloprost during the study period were identified. After applying study criteria, 467 patients were included in the final sample, including 405 in the inhaled treprostinil cohort and 62 in the iloprost cohort (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Cohort Selection

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS, HEALTH CARE RESOURCE UTILIZATION, AND COSTS

Demographic characteristics were well balanced between the inhaled treprostinil and iloprost groups, and there were no significant differences in age at the index date, sex, race, or coverage type (Table 1). Patients in the inhaled treprostinil group had a significantly higher mean QCCI score than patients in the iloprost group (P < 0.0001). Significantly more patients in the inhaled treprostinil group than in the iloprost group were PAH treatment naive prior to the index date (P = 0.0029). Among those who received pre-index PAH treatment, the most commonly prescribed treatment was dual therapy with an endothelin receptor antagonist and either a phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor or a soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator (144 of 467 patients [30.8%]).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Cohort

| All patients (N = 467) | Inhaled treprostinil (n = 405) | Iloprost (n = 62) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 64.2 (13.2) | 65.5 (13.5) | 64.0 (13.2) | 0.43 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 315 (67.5) | 272 (67.2) | 43 (69.4) | 0.73 |

| Male | 152 (32.5) | 133 (32.8) | 19 (30.6) | |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| White | 312 (66.8) | 275 (67.9) | 37 (59.7) | 0.48 |

| Black | 68 (14.6) | 55 (13.6) | 13 (21.0) | |

| Other | 87 (18.6) | 75 (18.5) | 12 (19.4) | |

| Coverage, n (%) | ||||

| Commercial | 155 (33.2) | 136 (33.6) | 19 (30.7) | 0.65 |

| Medicare | 312 (66.8) | 269 (66.4) | 43 (69.4) | |

| QCCI, mean (SD) | 2.9 (1.8) | 2.9 (1.8) | 2.5 (1.6) | <0.01 |

| QCCI category, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 7 (1.5) | 4 (1.0) | 3 (4.8) | 0.09 |

| 1 | 199 (42.6) | 170 (42.0) | 29 (46.8) | |

| 2 | 180 (38.5) | 158 (39.0) | 22 (35.5) | |

| ≥3 | 81 (17.3) | 73 (18.0) | 8 (12.9) | |

| Treatments, n (%) | ||||

| No therapy | 111 (23.8) | 102 (25.2) | 9 (14.5) | <0.01 |

| ERA monotherapy | 80 (17.1) | 61 (15.1) | 19 (30.7) | |

| PDE5I or SGCS monotherapy | 102 (21.8) | 95 (23.5) | 7 (11.3) | |

| PCY monotherapy | 3 (0.6) | 3 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| ERA + PDE5I or SGCS | 144 (30.8) | 119 (29.4) | 25 (40.3) | |

| PCY + PDE5I or SGCS | 6 (1.3) | 4 (1.0) | 2 (3.2) | |

| ERA + PCY | 4 (0.9) | 4 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| ERA + PCY + PDE5I or SGCS | 17 (3.6) | 17 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| All-cause health care resources, n (%) | ||||

| Inpatient admissions | 182 (39.0) | 159 (39.3) | 23 (37.1) | 0.75 |

| Emergency department visits | 118 (25.3) | 103 (25.4) | 15 (24.2) | 0.83 |

| Physician office visits | 393 (84.2) | 342 (84.4) | 51 (82.3) | 0.66 |

| Other outpatient visits | 405 (86.7) | 349 (86.2) | 56 (90.3) | 0.37 |

| All-cause health care costs, in USD, mean (SD)a | ||||

| Total costs | 63,385 (60,996) | 63,878 (52,995) | 60,161 (44,393) | 0.57 |

| Medical costs | 32,736 (51,480) | 33,425 (53,487) | 28,236 (35,709) | 0.33 |

| Pharmacy costs | 30,648 (32,010) | 30,453 (33,013) | 31,926 (24,651) | 0.68 |

a All costs are adjusted using the Consumer Price Index to 2020 USD.

ERA = endothelin receptor antagonist; PCY = prostacyclin analogue; PDE5I = phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor; QCCI = Quan-Charlson comorbidity index; SGCS = soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator; USD = US dollar.

There were no significant pre-index differences between the inhaled treprostinil and iloprost groups in all-cause inpatient admissions (159 [39.3%] vs 23 [37.1%], respectively), physician office visits (342 [84.4%] vs 51 [82.3%]), ED visits (103 [25.4%] vs 15 [24.2%]), or other outpatient visits (349 [86.2%] vs 56 [90.3%]). There were no significant differences between inhaled treprostinil and iloprost in all-cause mean (SD) pre-index total costs ($63,878 [63,183] vs $60,161 [44,393]), medical costs ($33,425 [53,487] vs $28,236 [35,709]), hospitalization costs ($12,932 [27,913] vs 13,480 [31,037]), or pharmacy costs ($30,453 [33,013] vs $31,926 [24,651]).

POST-INDEX ADHERENCE AND PERSISTENCE

Adherence (PDC ≥ 0.8) was significantly greater among patients who were prescribed inhaled treprostinil compared with those who were prescribed iloprost (50.9% vs 22.6%; P < 0.0001) (Figure 2A). When using a less stringent adherence threshold of a PDC of 0.5 or more, the corresponding values were 70.1% and 33.9% (P < 0.0001). Persistence with therapy was significantly greater among those who were prescribed inhaled treprostinil compared with those who were prescribed iloprost (log-rank P < 0.0001) (Figure 2B). In a multivariable analysis adjusted for age, sex, race, geographic region, coverage type, QCCI category, PAH medication regimen, and baseline hospitalizations, patients who initiated inhaled treprostinil had a 58% reduced risk for discontinuation over the 12-month post-index period compared with patients who initiated iloprost (hazard ratio = 0.42; 95% CI = 0.30-0.58; P ≤ 0.0001) (Table 2).

FIGURE 2.

Percentage of Patients

TABLE 2.

Multivariable Regressions for Post-Index Persistence and All-Cause Hospitalizations

| Persistence (Cox proportional hazards) | All-cause hospitalization (Log binomial regression) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio | 95% CI | Pvalue | Relative risk | 95% CI | P value | |

| Cohort (ref. iloprost) | ||||||

| Inhaled treprostinil | 0.42 | 0.30-0.58 | <0.01 | 0.71 | 0.54-0.92 | 0.01 |

| Age, years (ref. <65 years) | ||||||

| ≥65 years | 0.92 | 0.68-1.24 | 0.59 | 0.96 | 0.83-1.10 | 0.55 |

| Sex (ref. male) | ||||||

| Female | 0.98 | 0.76-1.27 | 0.89 | 1.05 | 0.94-1.18 | 0.38 |

| Race (ref. White) | ||||||

| Black | 0.93 | 0.65-1.35 | 0.71 | 0.94 | 0.77-1.16 | 0.58 |

| Other | 1.11 | 0.82-1.53 | 0.48 | 1.04 | 0.86-1.27 | 0.66 |

| Geographic region (ref. Northeast) | ||||||

| Midwest | 0.78 | 0.50-1.22 | 0.28 | 1.07 | 0.89-1.29 | 0.46 |

| South | 1.02 | 0.68-1.52 | 0.93 | 0.98 | 0.83-1.15 | 0.78 |

| West | 0.73 | 0.46-1.15 | 0.17 | 0.79 | 0.62-1.01 | 0.06 |

| Coverage type (ref. commercial) | ||||||

| Medicare | 1.15 | 0.84-1.57 | 0.40 | 1.10 | 0.95-1.28 | 0.21 |

| QCCI category (ref. 0-1) | ||||||

| 2-3 | 1.12 | 0.82-1.53 | 0.48 | 0.97 | 0.84-1.13 | 0.71 |

| 4+ | 1.12 | 0.78-1.62 | 0.54 | 1.12 | 0.94-1.32 | 0.19 |

| Baseline medications (ref. no therapy) | ||||||

| ERA monotherapy | 1.12 | 0.76-1.65 | 0.58 | 0.90 | 0.64-1.27 | 0.54 |

| PDE5I or SGCS monotherapy | 1.37 | 0.95-1.98 | 0.09 | 1.01 | 0.74-1.37 | 0.97 |

| PCY monotherapy | 0.51 | 0.07-3.75 | 0.51 | 2.18 | 0.83-5.71 | 0.11 |

| ERA + PDE5I or SGCS | 1.07 | 0.75-1.53 | 0.70 | 0.96 | 0.71-1.30 | 0.81 |

| PCY + PDE5I or SGCS | 0.75 | 0.27-2.11 | 0.59 | 0.85 | 0.37-1.98 | 0.71 |

| ERA + PCY | 1.02 | 0.24-4.30 | 0.98 | 1.10 | 0.39-3.09 | 0.85 |

| ERA + PCY + PDE5I or SGCS | 1.78 | 0.93-3.37 | 0.08 | 0.88 | 0.45-1.72 | 0.71 |

| Pre-index hospitalization (ref. no hospitalization) | ||||||

| Hospitalization | 1.10 | 0.82-1.47 | 0.54 | 1.36 | 1.05-1.76 | 0.02 |

ERA = endothelin receptor antagonist; PCY = prostacyclin analogue; PDE5I = phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitor; QCCI = Quan-Charlson comorbidity index; Ref = reference; SGCS = soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator.

POST-INDEX HEALTH CARE RESOURCE UTILIZATION

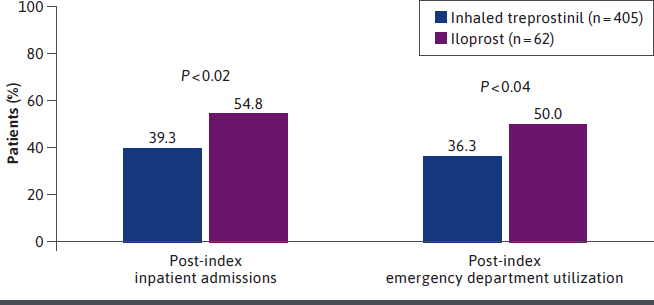

During the post-index period, a significantly lower percentage of patients who were prescribed inhaled treprostinil experienced any hospitalization compared with those who were prescribed iloprost (39.3% vs 54.8%, respectively; P = 0.02); there was also significantly lower ED utilization in the inhaled treprostinil group compared with the iloprost group (36.3% vs 50.0%, respectively; P = 0.039) (Figure 3). Furthermore, patients prescribed inhaled treprostinil experienced a significantly lower total number of all-cause hospitalizations (P = 0.02) and ED visits (P = 0.03) compared with patients prescribed iloprost. No significant differences were observed in the percentage of patients with physician office visits or other outpatient visits.

FIGURE 3.

Post-Index Inpatient Admissions and Post-Index Emergency Department Utilization

In the multivariable analysis adjusted for age, sex, race, geographic region, coverage type, QCCI category, PAH medication regimen, and baseline hospitalizations, there was a 29% reduction in risk for hospitalization among patients who were prescribed inhaled treprostinil compared with those who were prescribed iloprost (relative risk = 0.71; 95% CI = 0.54-0.92; P = 0.010) (Table 2).

POST-INDEX ALL-CAUSE HEALTH CARE COSTS

A total of 189 patients on inhaled treprostinil and 10 patients on iloprost persisted on therapy through 12 months. Among patients who were persistent with therapy through 12 months, there was no significant difference between groups in mean (SD) all-cause total costs ($266,462 [137,324] vs $262,826 [112,452]; P = 0.93). Mean all-cause medical costs were higher in the inhaled treprostinil group, whereas mean all-cause pharmacy costs were lower in the inhaled treprostinil group, but the differences were not significant.

Discussion

PAH is a devastating disease associated with substantial morbidity and mortality, as well as significant psychosocial and financial burdens. A recent study found that, even with advances in therapy, nearly 85% of patients still have cardiopulmonary symptoms and few are satisfied with their treatment.14 In light of this gap, there is considerable room to improve the management of these patients. Inhaled therapies may have advantages over systemically administered treatments in the management of pulmonary diseases, including direct delivery of higher concentrations of the drug to the target organ and potentially reduced systemic adverse events.15

This retrospective cohort study is the first, to our knowledge, to directly compare the inhaled formulation of treprostinil with iloprost for clinically and pharmacoeconomically relevant outcomes. In this study, both adherence and persistence were significantly higher in the inhaled treprostinil group than in the iloprost group. Given the lack of head-to-head clinical data comparing inhaled treprostinil and iloprost, it is not possible to definitively attribute these differences to the relative efficacy and/or tolerability of these agents. Instead, it is likely that the difference in dosing frequency and duration (8-12 minutes total daily treatment duration over 4 sessions for inhaled treprostinil vs 24-90 minutes total duration over 6-9 sessions for iloprost)7,8 was a major contributor to improved adherence and persistence.

It is important to note that inhalation time underestimates the total amount of time required to administer these drugs. A study conducted by Bourge and colleagues16 found that the transition from iloprost to inhaled treprostinil was associated with a 68% (P < 0.001) reduction in total treatment time, including a 48% reduction in time to gather supplies (P = 0.004), a 30% reduction in time to prepare the treatment system (P = 0.007), an 80% reduction in inhalation time (P < 0.001), and a 77% reduction in time required to clean the treatment system (P < 0.001). In total, the transition to inhaled treprostinil saved a mean of 1.4 hours per day (39.1 minutes at week 12 with inhaled treprostinil vs 123.2 minutes at baseline with iloprost). With the completion of the BREEZE clinical study, inhaled treprostinil is approved as a dry-powdered inhaler.17 This could potentially alleviate drug administration burden; however, further research is needed.

It is well recognized that treatment satisfaction is linked to adherence and persistence. Dissatisfied patients may be less likely to execute the treatment regimen in a fully adherent manner and have less involvement in the management of their disease over time.18,19 Maintaining and even improving treatment satisfaction is particularly critical in PAH, given that managing the often complex and time-consuming treatment regimens for the disease requires active patient or caregiver participation. Transition to inhaled treprostinil from iloprost was associated with improvements in all domains of the Cambridge Pulmonary Hypertension Outcome Review questionnaire and improvements in measures of global treatment satisfaction, perceived effectiveness, and perceived convenience, without changes in measures of perceived side effects.16,20 Overall, 94% of patients were much more or more satisfied with inhaled treprostinil therapy compared with iloprost. Differences in dose frequency and administration and past transition studies are likely to explain the differences in sample sizes identified in this study.

More than half of patients with PAH are hospitalized within 3 years of diagnosis.21 The hospitalizations are often recurrent and may be lengthy and, therefore, may be associated with considerable costs. In one study using the National Inpatient Sample to identify PAH admissions, the mean length of stay per PAH-related hospitalization was 7.6 ± 0.5 days and mean hospital charges were $103,300.22 Preventing hospitalization should be a major priority in the management of PAH, as it is associated with worse prognoses.23 Although this study does not provide direct evidence for causation, patients who were prescribed inhaled treprostinil were significantly less likely than those prescribed iloprost to require hospitalization or to use ED services for any reason.

Readmission to the hospital also presents a major challenge in patients with PAH. Recent data suggest that at least 20% of patients are readmitted within 30 days of discharge, with nearly 80% readmitted within 1 year of discharge, resulting in considerable additional clinical and economic burden.21,24,25 Consistent with the results for any hospitalization, fewer patients prescribed inhaled treprostinil than those prescribed iloprost had at least 2 all-cause hospitalizations, although this difference was not significant. The total costs of care (including both medical and pharmacy costs) were similar in the 2 groups.

LIMITATIONS

This study has several limitations. The PDC is widely used and well accepted as a measure of medication adherence; however, it is an indirect method and is based on insurance claims. As a general limitation of claims databases, the Optum Clinformatics Data Mart database provided no information on long-term disease history or reasons for discontinuation of therapy. Low sample size in the iloprost cohort might limit interpretation of certain outcomes. The data presented here provide no information on the underlying reason for the substantial and statistically significant difference in inpatient admissions and ED visits seen in these groups. At present, it can only be hypothesized that the measured differences in adherence and persistence were important contributors to the reduced health care utilization observed in the inhaled treprostinil group. Finally, this study provides no information on why adherence and persistence were greater in the inhaled treprostinil group. The differences may be attributable to a less burdensome treatment regimen; however, it is possible that other factors contributed to these differences.

Conclusions

This current real-world study demonstrated that both adherence and persistence are greater with inhaled treprostinil relative to iloprost. The results also suggest that inhaled treprostinil is less burdensome and may reduce all-cause hospitalizations and ED visits. The improvements were not associated with a significant difference in all-cause costs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The study authors would like to acknowledge members of Omni Healthcare Communications, John Ferguson and Orly Shemesh, in providing technical writing and editing assistance in this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beshay S, Sahay S, Humbert M. Evaluation and management of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Respir Med. 2020;171:106099. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2020.106099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirson NY, Birnbaum HG, Ivanova JI, et al. Prevalence of pulmonary arterial hypertension and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension in the United States. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(9):1763-8. doi:10.1185/03007995.2011.604310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prins KW, Thenappan T. World Health Organization group I pulmonary hypertension: Epidemiology and pathophysiology. Cardiol Clin. 2016;34(3):363-74. doi:10.1016/j.ccl.2016.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benza RL, Miller DP, Barst RJ, et al. An evaluation of long-term survival from time of diagnosis in pulmonary arterial hypertension from the REVEAL Registry. Chest. 2012;142(2):448-56. doi:10.1378/chest.11-1460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thenappan T, Ormiston ML, Ryan JJ, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: Pathogenesis and clinical management. BMJ. 2018;360:j5492. doi:10.1136/bmj.j5492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waxman A, Restrepo-Jaramillo R, Thenappan T, et al. Inhaled treprostinil in pulmonary hypertension due to interstitial lung disease. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:325-34. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2008470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tyvaso (inhaled treprostinil). Prescribing information. United Therapeutics Corp.; 2021. Accessed February 18, 2022. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/022387lbl.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ventavis (iloprost). Prescribing information. Actelion Pharmaceuticals US, Inc.; 2021. Accessed February 18, 2022. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/021779s010lbl.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bogart M, Stanford RH, Laliberté F, et al. Medication adherence and persistence in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients receiving triple therapy in a USA commercially insured population. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2019;14:343-52. doi:10.2147/COPD.S184653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burnier M. Medication adherence and persistence as the cornerstone of effective antihypertensive therapy. Am J Hypertens. 2006;19(11):1190-6. doi:10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guerci B, Chanan N, Kaur S, et al. Lack of treatment persistence and treatment nonadherence as barriers to glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2019;10(2):437-49. doi:10.1007/s13300-019-0590-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kjellstrom B, Sandqvist A, Hjalmarsson C, et al. Adherence to disease-specific drug treatment among patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension or chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. ERJ Open Res. 2020;6(4):00299-2020. doi:10.1183/23120541.00299-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mathai SC, Hemnes AR, Manaker S, et al. Identifying patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension using administrative claims algorithms. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019;16(7):797-806. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201810-672CME [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Helgeson SA, Menon D, Helmi H, et al. Psychosocial and financial burden of therapy in USA patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Diseases. 2020;8(2):22. doi:10.3390/diseases8020022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hill NS, Preston IR, Roberts KE. Inhaled therapies for pulmonary hypertension. Respir Care. 2015;60(6):794-802; discussion 802-795. doi:10.4187/respcare.03927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bourge RC, Tapson VF, Safdar Z, et al. Rapid transition from inhaled iloprost to inhaled treprostinil in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Cardiovasc Ther. 2013;31(1):38-44. doi:10.1111/1755-5922.12008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spikes LA, Bajwa AA, Burger CD, et al. BREEZE: Open-label clinical study to evaluate the safety and tolerability of treprostinil inhalation powder as Tyvaso DPI™ in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pulm Circ. 2022;12:e12063. doi:10.1002/pul2.12063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barbosa CD, Balp M-M, Kulich K, et al. A literature review to explore the link between treatment satisfaction and adherence, compliance, and persistence. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:39-48. doi:10.2147/PPA.S24752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiolero A, Burnier M, Santschi V. Improving treatment satisfaction to increase adherence. J Hum Hypertens. 2016;30(5):295-6. doi:10.1038/jhh.2015.89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen H, Rosenzweig E, Gotzkowsky S, et al. Treatment satisfaction is associated with improved quality of life in patients treated with inhaled treprostinil for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:31. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-11-31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burger CD, Long PK, Shah MR, et al. Characterization of first-time hospitalizations in patients with newly diagnosed pulmonary arterial hypertension in the REVEAL registry. Chest. 2014;146(5):1263-73. doi:10.1378/chest.14-0193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chaturvedi A, Kanwar M, Chandrika P, et al. National trends and inpatient outcomes of pulmonary arterial hypertension related hospitalizations - Analysis of the National Inpatient Sample database. Int J Cardiol. 2020;319:131-8. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.06.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benza RL, Gomberg-Maitland M, Elliott CG, et al. Predicting survival in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: The REVEAL risk score calculator 2.0 and comparison with ESC/ERS-based risk assessment strategies. Chest. 2019;156(2):323-37. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2019.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burke JP, Hunsche E, Régulier E, et al. Characterizing pulmonary hypertension-related hospitalization costs among Medicare Advantage or commercially insured patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: A retrospective database study. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21(3 Suppl):s47-58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Canavan N. Rehospitalization is driving costs in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2013;6(9):600-1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]