Abstract

Immunogenic peptides containing epitopes of the gp120 C4 and V3 regions from human immunodeficiency virus strains MN and EV91 have been studied by nuclear magnetic resonance and molecular modeling and used as immunogens in rhesus monkeys. The results, combined with those for other peptides, suggest a correlation between solution conformation and immunologic cross-reactivity.

Peptides containing sequences from the third variable (V3) region of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) gp120 are immunogenic for antibodies that neutralize T-cell-line-adapted (TCLA) HIV strains (13, 23, 24, 29). The V3 region also contains sequences that elicit anti-HIV cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses (30). The more conserved C4 region of gp120 contains a potent T helper (Th) determinant (4, 24). These observations led to the development of hybrid peptides, containing both C4 and V3 sequences, that are immunogenic for anti-HIV T-cell responses and for anti-TCLA-HIV neutralizing antibodies (14–16, 23, 24, 35). In addition, the V3 loop is of interest because it is implicated in HIV tropism and primary isolate coreceptor usage (6, 17). A recently determined crystal structure of gp120 suggested that both the C4 and V3 domains were at or near the gp120 regions that interact with coreceptors (19, 28).

Studies have been carried out on the immunogenic cross-reactivity of C4-V3 gp120 envelope peptides based on individual HIV isolates, as well as on polyvalent mixtures of several such peptides. In these peptides, the 16-residue C4 sequence is constant since the Th epitope it contains is highly conserved among HIV strains. The V3 segment (23 or 24 residues) of each hybrid peptide is strain specific since this portion of the envelope protein is variable in sequence and contains the strain-specific principal neutralizing determinant for TCLA HIV. Despite sequence variability in V3, cross-reactivity between antibodies elicited by one C4-V3 peptide and HIV strains with disparate V3 region amino acid sequences has been described (14, 16, 24, 33).

Immunogenic peptides in solution often preferentially adopt specific conformations (11, 20). Hence, one hypothesis to explain immunogenic cross-reactivity among variant sequences is that the respective peptides exist predominantly as conformers that present similar epitopes in a specific region of the conformer surface. In studies of C4-V3 hybrid peptides derived from HIV strains RF and Can0A, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) was used to demonstrate that particular conformations predominated in solution (7, 32). These results, combined with molecular simulation (32), showed that the immunogenic V3 sequence from HIVCan0A was likely to adopt preferential conformations that resembled the three-dimensional structure of an HIVMN V3 loop peptide when it is bound to the anti-HIV neutralizing monoclonal antibody 50.1 (27). In contrast, results for the non-cross-reactive V3 sequence from strain RF showed a distinctly different conformational propensity. To examine correlations between HIV gp120 structure and immunogenicity, we have assessed solution conformations in two other immunogenic gp120 C4-V3 peptides and have determined the immunologic cross-reactivity of induced neutralizing antibodies generated by the four peptides. The results support the hypothesis that preferred solution conformations of peptide immunogens are important for determining the specificity of C4-V3 peptide-induced anti-HIV neutralizing antibody responses.

Peptide C4-V3MN (C4-V3 peptide of strain MN) has the sequence KQIINMWQEVGKAMYA-TRPNYNKRKRIHIGPGRAFYTTK, while peptide C4-V3EV91 has the sequence KQIINMWQEVGKAMYA-TRPGNNTRKSIPIGPGRAFI ATS, where the hyphen denotes the junction of the common C4 segment (N-terminal 16 residues) and the strain-specific V3 segment (C-terminal 23 residues). The sequences of peptides C4-V3RF and C4-V3Can0A have been previously reported (7, 32). All four peptides were synthesized, purified, and characterized by mass spectrometry as previously described (16). For NMR spectroscopy, peptides were at a concentration of 4 mM in 0.67 ml of 5 mM KH2PO4–20 mM NaCl–2 mM NaN3–10% 2H2O (pH 4.0). Spectra, including DQF-COSY (25, 26), Relayed-COSY (2), TOCSY (1, 21), and NOESY (18) at mixing times of 100 to 300 ms, were collected as previously described on a Varian Unity 500-MHz spectrometer at a temperature of 5°C (7, 32). Spectra were processed by using Felix 2.3 (Biosym Technologies Inc.). Resonances were assigned as previously described (7, 32), and conformational preferences were determined by short- and medium-range nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE) connectivities (8–10).

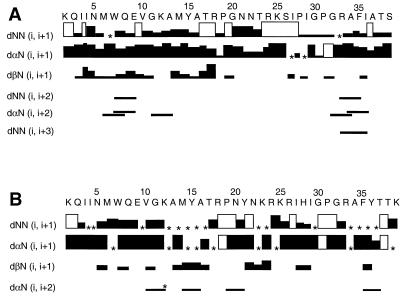

Resonances for nearly all hydrogens in peptides C4-V3MN and C4-V3EV91 were assigned (data available upon request). By the criterion of chemical shift deviation from random-coil values (34), neither peptide exhibited a tendency to form a stable secondary structure. Consistent with this were circular dichroism spectra of C4-V3MN in the range of 190 to 300 nm, which exhibited molar ellipticity values typical of random coil peptides (data not shown). Nevertheless, several NOE signals were attributed to long-range through-space interactions that indicate the tendency of certain regions to adopt particular conformers. These NOEs are summarized in Fig. 1A and B for peptides C4-V3EV91 and C4-V3MN, respectively.

FIG. 1.

Interresidue NOE connectivities in C4-V3EV91 (A) and C4-V3MN (B). In rows dNN (i, i+1), dαN (i, i+1), and dβN (i, i+1), the thicknesses of the solid boxes are proportional to the intensities of the NOE cross-peak. An asterisk appears at positions where NOE intensity could not be determined due to overlap with other peaks. A blank box indicates that the NOE was not detected. In rows dNN (i, i+2), dαN (i, i+2), and dNN (i, i+3), the lines connect residues showing the NOE. The line marked with an asterisk in panel B represents an ambiguous NOE in C4-V3MN (see text). Connectivities to NH of prolines refer to CδH.

In the C4 segment of both peptides, the first four or five residues (Lys1 to Asn5) show NOE patterns [strong dαN (i, i+1) and weak or absent dNN (i, i+1) NOEs] (8) characteristic of an extended conformation. In C4-V3EV91, the region Met6 to Ala13 adopts nascent helical conformations [a combination of dαN (i, i+2) and dNN (i, i+2) NOEs] (10). In C4-V3MN also, two NOEs of the type dαN (i, i+2) were observed for the region Val10 to Tyr15, suggesting that in this region this peptide adopts a nascent helical conformation.

For the V3 segment of C4-V3EV91, NOESY data suggest the existence of distinct conformational tendencies in several regions. A type II β-turn (the segment Arg18-Pro19-Gly20-Asn21) is suggested by dNN (Gly20-Asn21) and dαN (Pro19-Gly20) NOEs (9). For residues Asn22 through Ser26, strong dαN (i, i+1) and absent dNN (i, i+1) NOEs indicate a stretch of extended conformation (8). The next seven residues, Ile27 to Arg33, show preferences for two type I β-turns. The first involves the segment Ile27-Pro28-Ile29-Gly30, within which a dNN (i, i+1) NOE from Ile29 to Gly30 and a dδN (Pro28-Ile29) NOE which distinguishes a type I from a type II β-turn are observed (9). The conserved GPGR motif makes up the second reverse turn in this region. A dNN (i, i+1) NOE between Gly32 and Arg33, which is expected for such a turn, could not be identified due to peak overlap. However, a dδN NOE is clearly observed for Pro31-Gly32, consistent with the second and third residues of a turn. A short stretch of nascent helical conformation for the region Ala33 to Ile36 is suggested by dNN (i, i+2) and dαN (i, i+2) NOEs. The last three residues in the V3 segment of C4-V3EV91 exhibit an extended β-like conformation, as suggested by strong dαN (i, i+1) and weak dNN (i, i+1) NOEs. These secondary structural tendencies are summarized in Fig. 2.

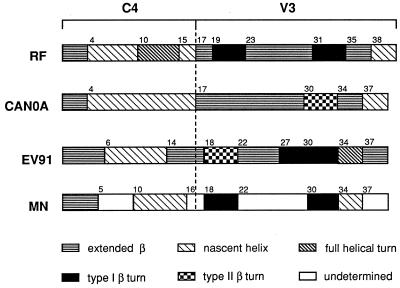

FIG. 2.

Comparison of NMR-derived conformational preferences among four C4-V3 peptides. For each peptide, the drawn pattern in a given region refers to the preferred solution conformation, as indicated in the key at the bottom of the figure.

In peptide C4-V3MN, conformational preferences in many portions of the V3 segment could not be uniquely identified due to extensive overlap of cross peaks in the NOESY spectrum. Some regions, however, show enough discernible NOEs to suggest the existence of conformational tendencies (Fig. 1B). The segment Arg18-Pro19-Asn20-Tyr21 exhibits a pattern expected for a type I β-turn (9) (dNN [Asn20-Tyr21] and dαN [Pro19-Tyr21] NOEs). A second type I β-turn is also suggested for the segment Gly30-Pro31-Gly32-Arg33. Immediately C-terminal to this turn is a possible segment of nascent helix, comprised of amino acids Ala34 to Tyr36 [dαN (i, i+2) NOE] (Fig. 1B). Figure 2 summarizes preferred conformations for peptides C4-V3EV91 and C4-V3MN, as described above, as well as for peptides C4-V3RF (7) and C4-V3Can0A (32). The C4 segments of all four peptides, which are identical in amino acid sequence, show in each case a threshold population of nascent helical conformation between residues 5 and 15. The V3 domains, which differ in amino acid sequence, show significantly different conformational elements. Whereas a tendency for a reverse turn at the GPGX motif is found in all four peptides, the nature of these turns is different, with C4-V3Can0A displaying a type II β-turn while other C4-V3 peptides show a type I β-turn. In addition, the C4-V3EV91 V3 region exhibits a preference for two consecutive type I β-turns within the sequence IPIGPGR.

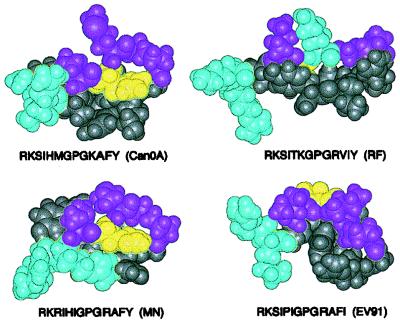

The NMR results detailed above reveal preferred solution conformations primarily for the main chain. These data were used as a starting point to search for preferred low-energy conformers, including side chains, by molecular modeling of a 13-residue segment encompassing the tip of the V3 loop, by using the method previously applied to HIVRF and HIVCan0A sequences (32). This is the principal neutralizing determinant for laboratory-adapted strains of HIV, and the structure of this region is known for the MN sequence bound to a Fab fragment of a neutralizing antibody (27). The modeled sequence of C4-V3EV91 comprised Arg24 to Ile36 (RKSIPIGPGRAFI). The following conformations, based on NMR data, were set: Arg24 to Ser26, β-strand; Ile27 to Gly30, type I β-turn; Gly30 to Arg33, type I β-turn; Ala34 to Ile36, α-helix. The modeled sequence of C4-V3MN comprised residues Arg24 to Tyr36 (RKRIHIGPGRAFY). Residues Arg24 to Ile29 were set as a β-strand, residues Gly30 to Arg33 were set as a type I β-turn, and Ala34 to Tyr36 were set as an α-helix. Each side chain conformation was initially set to the minimum-energy rotamer. The final structure of each peptide, shown in Fig. 3, was among the lowest-energy structures of all samplings, based on molecular dynamics calculations.

FIG. 3.

CPK models of simulated conformations for a 13-residue segment of the V3 loop from four TCLA HIV-1 strains, based on NMR connectivity patterns, made by using the program Insight II (Biosym/MSI Inc.). The conformers displayed were energy minimized with Discover 3.1 by use of a procedure detailed previously (32). Magenta atoms correspond to residue positions of the hydrophobic patch of the V3 region of strain MN (27). Cyan atoms correspond to lysine and arginine residues N-terminal to the GPGX motif. Yellow atoms correspond to the position of the histidine residue in the V3 region in strain MN. Gray atoms correspond to all other residues.

The resulting model of the HIVMN V3 loop in solution (Fig. 3, lower left model) exhibited a continuous hydrophobic surface formed by one Gly, one Pro, and two Ile residues (Fig. 3, magenta atoms). In the sequence of the V3 loop from HIVCan0A, in which one of the Ile residues of HIVMN was replaced by Met, these four residues also formed an apolar patch (Fig. 3, upper left model), as previously reported (32). The configuration of the side chain of His28 (Fig. 3, yellow atoms) in HIVCan0A was also the same as that in the simulated C4-V3MN peptide.

Simulations of the HIV V3 regions in peptides C4-V3RF (32) and C4-V3EV91 (Fig. 3, upper right and lower right models, respectively) exhibited V3 motifs that differed from those of peptides C4-V3MN and C4-V3Can0A. For C4-V3RF, a positively charged lysine residue (Fig. 3, cyan atoms) disrupted the hydrophobic surface of the apolar patch (32). In the V3 sequence of C4-V3EV91, the model revealed that the additional β-turn at Ile27-Pro28-Ile29-Gly30 caused the apolar patch to be bent rather than flat (Fig. 3, lower right model). Hence, the tip of the V3 loop in C4-V3RF was dramatically different from that of C4-V3MN and C4-V3Can0A, and that of C4-V3EV91 had a bent, rather than flat, apolar patch.

Previous studies have demonstrated that while gp120 V3 neutralizing antibodies are usually strain specific (14, 16, 23, 24, 35), occasional cross-reactivities between disparate strains, often attributed to homologies in the V3 loop tip sequence GPG or GPGR, have been reported (16). Rhesus monkeys were immunized with peptides C4-V3MN, C4-V3RF, C4-V3EV91, C4-V3Can0A, or a polyvalent mixture of all four peptides. Immune sera were then assayed for syncytium inhibition and free-virus neutralization activities against four different HIV strains (IIIB, MN, RF, and SF2) grown and assayed in CEM cells as previously described (16, 23). Table 1 shows the resulting syncytium inhibition titers and neutralization titers, defined as the reciprocal of the serum dilution that reduced syncytium numbers or infectious virus titer 10-fold, respectively, for these sera.

TABLE 1.

Ability of C4-V3 peptides to induce anti-HIV neutralizing antibodies in rhesus monkeys to four TCLA HIV isolates after two or three immunizations

| Rhesus no. or control serum | Immunogen | Syncytium inhibition titera

|

Neutralization titer

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIVIIIB | HIVMN | HIVRF | HIVSF2 | HIVIIIB | HIVMN | HIVRF | HIVSF2 | ||

| Rhesus no. | |||||||||

| 26252 | Polyvalent | +/− | 98 | 163 | 29 | <20 | >5,000 | >6,400 | 993 |

| 26322 | Polyvalent | +/− | 93 | 540 | 12 | 112 | >5,000 | >6,400 | <200 |

| 26423 | Polyvalent | 0 | 39 | 15 | +/− | <20 | 4,581 | >6,400 | <200 |

| 26424 | C4-V3MN | 0 | 55 | 0 | 10 | <20 | >5,000 | <20 | <200 |

| 26452 | C4-V3MN | 0 | 12 | 0 | 10 | <20 | 4,449 | <20 | <200 |

| 26631 | C4-V3MN | 0 | 14 | 0 | 0 | <20 | 2,576 | <20 | <200 |

| 26654 | C4-V3RF | 0 | 0 | 31 | 0 | <20 | <20 | 4,351 | <20 |

| 26716 | C4-V3RF | 0 | +/− | 191 | 0 | <20 | <20 | >6,400 | <20 |

| 26739 | C4-V3RF | 0 | +/− | 243 | 0 | <20 | <20 | 4,351 | <20 |

| 26906 | C4-V3EV91 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 24 | <20 | 442 | <20 | <200 |

| 26992 | C4-V3EV91 | 0 | +/− | 0 | 0 | <20 | <20 | <20 | <20 |

| 27011 | C4-V3EV91 | 0 | +/− | 0 | 0 | <20 | <20 | <20 | <20 |

| 27055 | C4-V3Can0A | 0 | +/− | 0 | 0 | <20 | <20 | <20 | <20 |

| 27094 | C4-V3Can0A | 0 | 18 | 0 | 0 | <20 | 4,197 | <20 | <20 |

| 27111 | C4-V3Can0A | 0 | 32 | 0 | 0 | <20 | 4,449 | <20 | <20 |

| Control sera | |||||||||

| HIVIIIB | Positive serum (goat 70) | 45 | 504 | ||||||

| HIVMN | Positive patient serum | 60 | 4,314 | ||||||

| HIVRF | Positive serum (goat 1004) | 130 | 310 | ||||||

| HIVSF2 | Positive patient serum | 427 | 12,800 | ||||||

+/−, less than 90% and more than 25% inhibition of syncytium formation at a 1:10 dilution.

As reported, peptide C4-V3MN induced antibodies that inactivated HIVMN in syncytium inhibition and reverse transcriptase production assays (16), as did peptide C4-V3Can0A (33). Anti-C4-V3MN sera had no inhibitory activity toward either HIVIIIB or HIVRF. Antibodies against C4-V3EV91 were weakly reactive against HIVMN in that sera from only one of three monkeys neutralized HIVMN. Antibodies induced by peptide C4-V3RF were type specific, with anti-HIVRF V3 antisera neutralizing only HIVRF. Thus, the MN and Can0A (and to a lesser degree EV91) C4-V3 peptides, though disparate in primary amino acid sequence, neutralized HIVMN in a similar manner, whereas the HIVRF C4-V3 peptide was strictly HIVRF specific.

The present results of NMR-derived conformational preferences in peptides C4-V3MN and C4-V3EV91 may be combined with previous results for peptides C4-V3RF (7) and C4-V3Can0A (32) to summarize similarities and differences among them. The conformational features of the C4 segment in all four peptides were very similar, suggesting that the respective unique V3 sequences had little influence on C4 conformation. Each C4 segment begins with an extended conformation, which is followed by a major segment of nascent helix (Fig. 2). The nascent helical region coincides with a T-helper epitope (4) that is thought to exist in an extended conformation when bound to the major histocompatibility complex on antigen-presenting cells (22).

The V3 segments of each of the four C4-V3 peptides are derived from different HIV type 1 (HIV-1) strains. Preference for a β-turn conformation appears at the N-terminal end of the V3 region in all of the peptides except C4-V3Can0A (Fig. 2). The lack of detectable turn conformation in the latter may be related to the finding that β-turn stability in peptides in solution is correlated with the residue at the third position of the turn. Asparagine at this position in C4-V3RF and C4-V3MN, and glycine in the case of C4-V3EV91, are associated with greater turn stability than is histidine in C4-V3Can0A (9). A long stretch of extended conformation precedes the GPGX β-turn in the V3 regions of three of the peptides and may also be present in C4-V3MN (Fig. 2). In all four peptides, the GPGX motif has a tendency to take β-turn conformations, type I in peptides C4-V3RF, C4-V3EV91, and C4-V3MN and type II in peptide C4-V3Can0A. Other solution NMR studies have found turns at the GPGX motif in peptides derived from the gp120 V3 loop of HIV-1 strains MN (3, 5), IIIB/LAI (36), and RF (31). A propensity for an additional type I β-turn comprised of residues Ile27-Pro28-Ile29-Gly30 in C4-V3EV91 is identified immediately before the common Gly30-Pro31-Gly32-Arg33 β-turn. Consecutive turns at the tip of the V3 loop have been demonstrated for HIV-1MN V3 peptide bound to the Fab fragment of a neutralizing antibody. The antibody-bound peptide has a structure of type II β-turn (GPGR), type III β-turn (GRAF), and type I β-turn (RAFY), which together resemble a 310 helix configuration (12). Conformational propensities in the region C-terminal to the GPGX motif vary among the four C4-V3 peptides (Fig. 2). Strains RF and Can0A show preferences for extended conformations from residues 34 to 37 followed by nascent helical preferences to the C terminus. In strains EV91 and MN, the tendency towards a helical or nascent helical conformation immediately follows GPGX, which is then followed by an extended conformation to the end of the peptide.

Molecular simulation of conformations in four different V3 sequences suggest that preferred solution conformations of MN and Can0A near the tip of the V3 loop are similar to each other. Furthermore, both have conformational characteristics similar to the HIVMN V3 region bound to a neutralizing antibody (27). In that crystal structure, four peptide residues, equivalent in numbering to Ile27, Ile29, Gly30, and Pro31 of C4-V3MN, form a continuous hydrophobic surface which makes extensive contacts with the antigen-binding site of the antibody and is suggested to be required for high-affinity binding (27). In the present study, modeled V3 solution conformers of MN and Can0A exhibit a flat hydrophobic surface at the very beginning of the reverse turn (Fig. 3). These apolar patches are composed of side chains from residues I, I, G, and P in MN and I, M, G, and P in Can0A. Thus, these models indicate that predominant conformers of C4-V3MN and C4-V3Can0A in solution shared with the antibody-antigen complex a relatively flat hydrophobic region in the tip of the V3 loop.

The V3 sequence of EV91 also has the residues I, I, G, and P, which, by simulation, form an apolar patch at the tip of its V3 loop. However a proline residue between the two isoleucine residues of EV91 (histidine in this position for the V3 sequence of MN and Can0A) resulted in a propensity for a reverse turn, causing a bend in the middle of the apolar patch (Fig. 3). In the V3 sequence of strain RF, the second isoleucine residue is replaced by lysine (I, K, G, P). Modeling suggests that the positively charged side chain of this lysine is oriented toward the face of the apolar patch and therefore disrupts the continuity of the hydrophobic surface in C4-V3RF (Fig. 3).

The present study demonstrates differential neutralizing capabilities among the four peptides tested in rhesus monkeys (Table 1), hence extending previous findings (14–16, 23, 24). Haynes et al. reported that C4-V3MN and C4-V3Can0A peptides were immunologically similar since, in BALB/c mice, each peptide induced antibodies that were cross-reactive to the V3 region of the other peptide (16). In contrast, C4-V3RF and C4-V3EV91 peptides elicited type-specific antibodies in BALB/c mice (16). Peptides C4-V3MN and C4-V3Can0A also both elicit neutralizing HIV MN antibody responses (16, 33; also this study). Molecular simulation of HIV V3 sequences based on NMR results for main chain preferences have shown that HIV Can0A and MN may preferentially present molecular surfaces that are very similar, which in turn are distinct from V3 conformations of RF and EV91 sequences. Furthermore, the modeled conformations of both HIVMN and HIVCan0A peptides are similar to that of the HIVMN peptide bound to a neutralizing antibody (27) that was induced by an MN V3 immunogenic peptide. Taken together, these data support the hypothesis that preferred solution conformations are an important factor in determining the specificity of C4-V3 peptide-induced anti-HIV neutralizing antibody responses. It will be of interest to begin to correlate V3 region conformer structure with HIV coreceptor usage.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the expert technical assistance of Richard M. Scearce, Dawn M. Jones, Charlene McDanal, and William Millard. Robert D. Stevens, Department of Pediatrics, Duke University Medical Center, is also gratefully acknowledged for mass spectrometric analyses.

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institute of Health (GM 41829 to L.D.S. and AI135351 to B.F.H.) and the Department of Defense, Army (DAMD 17-94-J-4467). H.M.V. and R.d.L. were supported by NIH Training Fellowships AI07392-06 and AI07217, respectively.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bax A, Davis D G. MLEV-17 based two-dimensional homonuclear magnetization transfer spectroscopy. J Magn Reson. 1985;65:355–360. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bolton P H, Bodenhausen G. Relayed coherence transfer spectroscopy of heteronuclear systems: detection of remote nuclei in NMR. Chem Phys Lett. 1982;89:139–144. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Catasti P, Fontenot J D, Bradbury E M, Gupta G. Local and global structural properties of the HIV-MN V3 loop. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:2224–2232. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.5.2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cease K B, Margalit H, Cornette J L, Putney S D, Robey W G, Ouyang C, Streicher H Z, Fischinger P J, Gallo R C, DeLisi C, Berzofsky J A. Helper T-cell antigenic site identification in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome virus gp120 envelope protein and induction of immunity in mice to the native protein using a 16-residue synthetic peptide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:4249–4253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.12.4249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chandrasekhar K, Profy A T, Dyson H J. Solution conformational preferences of immunogenic peptides derived from the principal neutralizing determinant of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein gp120. Biochemistry. 1991;30:9187–9194. doi: 10.1021/bi00102a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choe H, Farzan M, Sun Y, Sullivan N, Rollins B, Ponath P D, Wu L, Mackay C R, LaRosa G, Newman W, Gerard N, Garard C, Sodroski J. The β-chemokine receptors CCR3 and CCR5 facilitate infection by primary HIV-1 isolates. Cell. 1996;85:1135–1148. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Lorimier R, Moody M A, Haynes B F, Spicer L D. NMR-derived solution conformations of a hybrid synthetic peptide containing multiple epitopes of envelope protein gp120 from the RF strain of human immunodeficiency virus. Biochemistry. 1994;33:2055–2061. doi: 10.1021/bi00174a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dyson H, Wright P E. Defining solution conformations of small linear peptides. Annu Rev Biophys Biophys Chem. 1991;20:519–538. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.20.060191.002511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dyson H J, Rance M, Houghten R A, Lerner R A, Wright P E. Folding of immunogenic peptide fragments of proteins in water solution. I. Sequence requirements for the formation of a reverse turn. J Mol Biol. 1988;201:161–200. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90446-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dyson H J, Rance M, Houghten R A, Wright P E, Lerner R A. Folding of immunogenic peptide fragments of proteins in water solution. II. The nascent helix. J Mol Biol. 1988;201:201–218. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90447-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dyson H J, Lerner R A, Wright P E. The physical basis for induction of protein-reactive antipeptide antibodies. Annu Rev Biophys Biophys Chem. 1988;17:305–324. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.17.060188.001513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghiara J B, Stura E A, Stanfield R L, Profy A T, Wilson I A. Crystal structure of the principal neutralizing site of HIV-1. Science. 1994;264:82–85. doi: 10.1126/science.7511253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goudsmit J, Debouck C, Meloen R H, Smit L, Bakker M, Asher D M, Wolff A V, Gibbs C J, Jr, Gajdusek D C. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 neutralization epitope with conserved architecture elicits early type-specific antibodies in experimentally infected chimpanzees. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:4478–4482. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.12.4478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hart M K, Palker T J, Matthews T J, Langlois A J, Lerche N W, Martin M E, Scearce R M, McDanal C, Bolognesi D P, Haynes B F. Synthetic peptides containing T and B cell epitopes from human immunodeficiency virus envelope gp120 induce anti-HIV proliferative responses and high titers of neutralizing antibodies in rhesus monkeys. J Immunol. 1990;145:2677–2685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hart M K, Weinhold K J, Scearce R M, Washburn E M, Clark C A, Palker T J, Haynes B F. Priming of anti-human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) CD8+ cytotoxic T cells in vivo by carrier-free HIV synthetic peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:9448–9452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.21.9448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haynes B F, Torres J V, Langlois A J, Bolognesi D P, Gardner M B, Palker T J, Scearce R M, Jones D M, Moody M A, McDanal C, Matthews T J. Induction of HIVMN neutralizing antibodies in primates using a prime-boost regimen of hybrid synthetic gp120 envelope peptides. J Immunol. 1993;151:1646–1653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hwang S S, Boyle T J, Lyerle H K, Cullen B R. Identification of the envelope V3 loop as the primary determinant of cell tropism in HIV-1. Science. 1991;253:71–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1905842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeener J, Meier B H, Bachmann P, Ernst R R. Investigation of exchange processes by two-dimensional NMR spectroscopy. J Phys Chem. 1979;71:4546–4553. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwong P D, Wyatt R, Robinson J, Sweet R W, Sodroski J, Hendrickson W A. Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing human antibody. Nature. 1998;393:648–659. doi: 10.1038/31405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lerner R A. Antibodies of predetermined specificity in biology and medicine. Adv Immunol. 1984;36:1–44. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60898-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levitt M H, Freeman R, Frenkiel T. Broadband heteronuclear decoupling. J Magn Reson. 1982;47:328–330. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Madden D R, Garboczi D N, Wiley D C. The antigenic identity of peptide-MHC complexes: a comparison of the conformations of five viral peptides presented by HLA-A2. Cell. 1993;75:693–708. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90490-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palker T J, Clark M E, Langlois A J, Matthews T J, Weinhold K J, Randall R R, Bolognesi D P, Haynes B F. Type-specific neutralization of the human immunodeficiency virus with antibodies to env-encoded synthetic peptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:1932–1936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.6.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palker T J, Matthews T J, Langlois A, Tanner M E, Martin M E, Scearce R M, Kim J E, Berzofsky J A, Bolognesi D P, Haynes B F. Polyvalent human immunodeficiency virus synthetic immunogen comprised of envelope gp120 T helper cell sites and B cell neutralization epitopes. J Immunol. 1989;142:3612–3619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piantini U, Sørensen O W, Ernst R R. Multiple quantum filters for elucidating NMR coupling networks. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:6800–6801. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rance M, Sørensen O W, Bodenhausen G, Wagner G, Ernst R R, Wüthrich K. Improved spectral resolution in COSY 1H NMR spectra of proteins via double quantum filtering. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1983;117:479–485. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(83)91225-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rini J M, Stanfield R L, Stura E A, Salinas P A, Profy A T, Wilson I A. Crystal structure of a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 neutralizing antibody, 50.1, in complex with its V3 loop peptide antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6325–6329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rizzuto C D, Wyatt R, Hernandez-Ramos N, Sun Y, Kwong P D, Hendrickson W A, Sodroski J. A conserved HIV gp120 glycoprotein structure involved in chemokine receptor binding. Science. 1998;280:1949–1953. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rusche J R, Javaherian K, McDanal C, Petro J, Lynn D L, Grimaila R, Langlois A, Gallo R C, Arthur L O, Fischinger P J, Bolognesi D P, Putney S D, Matthews T J. Antibodies that inhibit fusion of human immunodeficiency virus-infected cells bind a 24-amino acid sequence of the viral envelope gp120. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:3198–3202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.9.3198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takahashi H, Nakagawa Y, Pendleton C D, Houghten R A, Yokomuro K, Germain R N, Berzofsky J A. Induction of broadly cross-reactive cytotoxic T cells recognizing an HIV-1 envelope determinant. Science. 1992;255:333–336. doi: 10.1126/science.1372448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vranken W F, Budesinsky M, Martins J C, Fant F, Boulez K, Gras-Masse H, Borremans F A M. Conformational features of a synthetic cyclic peptide corresponding to the complete V3 loop of the RF HIV-1 strain in water and water/trifluoroethanol solutions. Eur J Biochem. 1996;236:100–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vu H M, de Lorimier R, Moody M A, Haynes B F, Spicer L D. Conformational preferences of a chimeric peptide HIV-1 immunogen from the C4-V3 domains of gp120 envelope protein of HIV-1 CAN0A based on solution NMR: comparison to a related immunogenic peptide from HIV-1 RF. Biochemistry. 1996;35:5158–5165. doi: 10.1021/bi952665x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weinberg J, Liao H-X, Torres J V, Matthews T J, Robinson J, Haynes B F. Identification of a synthetic peptide that mimics an HIV glycoprotein 120 envelope conformational determinant exposed following ligation of glycoprotein 120 by CD4. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1997;13:657–664. doi: 10.1089/aid.1997.13.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wishart D S, Sykes B D, Richards F M. Relationship between nuclear magnetic resonance chemical shift and protein secondary structure. J Mol Biol. 1991;222:311–333. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90214-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yasutomi Y, Palker T J, Gardner M B, Haynes B F, Letvin N L. Synthetic peptide in mineral oil adjuvant elicits simian immunodeficiency virus-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes in rhesus monkeys. J Immunol. 1993;151:5096–5105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zvi A, Hiller R, Anglister J. Solution conformation of a peptide corresponding to the principal neutralizing determinant of HIV-1IIIB: a two-dimensional NMR study. Biochemistry. 1992;31:6972–6979. doi: 10.1021/bi00145a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]