Abstract

The objective of this study was to quantify the quality of life (QoL) of caregivers with children with influenza-like illnesses (ILI) and to identify factors associated with worse QoL. This was a cross-sectional cohort study of caregivers in a pediatric emergency department with previously healthy young children with ILI. The primary outcome was caregiver QoL. Additional measures included health literacy, social support, and caregiver health status. Two hundred and eighty-one caregivers completed the study. And 41% reported overall QoL was worse during their child's illness. The median QoL score was 3.8 [3.1, 4.6] in a 7-point scale. Illness duration was associated with worse overall QoL score (0.128 worse for each additional day of illness). The median emotions domain score was 2.5 [1.5, 4.0], the worst of any domain. Caregivers who perceived worse illness severity had lower emotions domain scores (2.61 vs 6.00, P = .0269). Caregivers with adequate literacy had lower mean QoL scores (3.08 vs 4.44, P < .0001). Childhood illnesses worsen caregiver QoL. Factors associated with worse QoL were perception of illness severity and duration. Addressing caregiver QoL could mitigate the impact of childhood acute illnesses on caregiver wellbeing.

Keywords: pediatrics, emergency medicine, influenza-like illness, quality of life, family-centered care, Abbreviations, ED, emergency department; ILI, influenza-like illness; MSPSS, multidimension scale of perceived social support; PFCC, patient- and family-centered care; QoL, quality of life; SF-12v2, Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form version 2.

Introduction

Improving the wellbeing of pediatric patients and their families by creating therapeutic partnerships that incorporate social, cultural, and contextual factors is a key healthcare issue.1,2 Health-related quality of life (QoL), broadly defined as an individual's concepts of perceived physical, psychological, and social health over time, is an important health outcome in clinical practice, quality improvement, and healthcare services research. 3 For families who present for unscheduled care with acutely ill children, QoL is an important aspect of wellbeing that incorporates the intangible costs of disease burden including worry, anxiety, inability to complete tasks of daily life, and social disruption . 4 However, our current understanding of how acute illnesses affect the QoL of whole families is limited. Additionally, QoL is not systematically addressed in emergency departments (EDs) or in discharge instructions.5–7 Therefore, understanding QoL changes during acute illness is important to optimize patient- and family-centered care (PFCC) and offers an opportunity to improve patient experience, quality, safety, and equity for children and families.1,8,9

The clinical burden of influenza has been well-described but its effects on caregiver wellbeing are not understood. Influenza-like illnesses (ILIs) are defined as acute fever and one or more of the following respiratory symptoms: cough, rhinorrhea, or sore throat. 10 ILIs affect millions of children yearly and significantly impact caregiver wellbeing, finances, and emotional health.11,12 They constitute a bulk of primary care sick visits and nearly 15% of all ED visits. 13 QoL for children with acute cough is known to be significantly lower at the time of ED visits and is most impacted by cough severity. 14 Optimal PFCC for ILIs identifies and addresses the needs and wellbeing of the caregiver because their anxiety, stress, and worry may drive decision making and utilization.

While studies have investigated caregiver QoL in children with chronic illnesses, fewer have studied acute illnesses.15–17 Chow et al 18 developed this study's primary measure, the Care-QoL-ILI, in an urban Australian population where it was shown to have good concurrent and discriminant validity. The impact of ILI on caregiver wellbeing in a diverse US population is unknown. In young children with ILI, estimation of the child's QoL remains difficult and the multifaceted burdens of disease affect the caregiver and family as a whole. 19 These multifaceted changes in quality of life may be affected by social determinants of health and family contextual factors.20,21 Additionally, racial disparities exist in pediatric ED outcomes, including appendicitis care, diagnostic imaging, antibiotic usage, gastroenteritis, and pain management.22–26 These known racial disparities in emergency care and outcomes suggest that there may be racial disparities in other important measures, including caregiver QoL. Therefore, a foundational quantitative understanding of caregiver QoL is needed, including analysis of racial differences in changes in QoL during acute illnesses, to provide insights into how to reduce disparities and improve family-centered care for diverse populations. The ED is an opportune location to sample a diverse group of caregivers who choose unscheduled care in order to ultimately develop interventions that improve PFCC in EDs.

The objective of this study was to quantify the QoL of caregivers with previously healthy young children with ILI who presented to ED and urgent cares (UCs) in a pediatric healthcare system serving a diverse socioeconomic population. This study coincided with the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. We sought to identify factors associated with worse QoL to provide insights into the caregiver experience of illness and inform future efforts to improve family-centered care in a variety of settings. We hypothesized that prolonged illness duration prior to ED presentation, lower health literacy and lower levels of social support would be associated with worse caregiver QoL.

Method

Study Design, Participants, and Setting

This was a cross-sectional cohort study to quantify the health-related QoL of caregivers presenting to an ED or UC with a child aged 6 to 48 months with ILI. For this study, “caregiver” refers to a parent or legal guardian who primarily cares for the child at home. The Institutional Review Board of Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center approved this study.

ILI was defined as an acute respiratory disease of sudden onset and fever (temperature ≥ 38 °C) measured at the study site or reported by caregivers within 24 h prior to presentation and accompanied by at least one of the following: cough, nasal congestion, runny nose, or sore throat.10,27 A consecutive sample of all children who presented to the study sites were identified and assessed for eligibility by study personnel using the chief complaint listed on the electronic ED and UC track board. Research staff identified caregivers by reviewing electronic health records of registered patients and approached caregivers for enrollment. Participants were not enrolled if (1) the parent/legal guardian was not present, (2) the child had a history of severe chronic disease, (3) the child had already been evaluated at our ED for the current illness, (4) the legal guardian did not live primarily in the household of the child during the period of illness, or (5) the child was treated in our Shock/Trauma Suite for critical illness or sexual abuse at the visit. Written informed consent and demographic information were obtained via caregiver self-report. Surveys were administered during the ED visit. After the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, study procedures were altered. Enrollment, verbal consent, and survey administration were conducted remotely via phone, with study procedures completed via phone or online (based on caregiver preference) within 24 h of the ED visit. A review of the child's medical records was conducted to catalog laboratory testing, medical treatment, and disposition. We enrolled only English-speaking subjects due to the lack of validation of the Care-QoL-ILI in other languages and the low proportion of non-English-speaking patients in our ED.

The study setting was the pediatric ED and UC at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center. The study took place at both the main hospital site as well as at a suburban satellite location. These sites have an annual combined volume of approximately 120 000 visits and serve populations with diverse racial and socioeconomic backgrounds. Each year, an average of 14 300 children between the ages of 6 and 48 months present for evaluation of ILI.

Questionnaires

The primary outcome, secondary outcome, and key co-variates were measured with validated and reliable tools. The primary outcome of interest, QoL, was measured using the Care-QoL-ILI—a validated disease-specific measure of wellbeing of caregivers of children aged 6 and 48 months with ILI. It contains 16 questions that cover 4 domains: daily activities, perceived support, social life, and emotions. Participants are asked to consider the past week when answering questions on a 7-point Likert scale for each question (eg, “much worsened,” “stayed the same,” and “much improved”) allowing for subjective comparison across time. It also measures caregiver perception of disease severity. It was developed in Australia using rigorous methods and was determined to be valid and reliable in urban English-speaking populations. 18 Preparatory to this study, short cognitive interviews were conducted with 20 caregivers at the study sites to identify verbiage that needed to be clarified due to slight syntax variations in the Australian English. A selection of 5 questions from the Care-QoL-ILI was presented to each participant, allowing for adequate evaluation of all survey questions. 28 The cognitive interviews indicated that no alterations of the original survey language were necessary for our study population.

The Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form version 2 (SF-12v2) is a generic assessment of health-related QoL of the caregivers themselves, allowing comparison of baseline differences that may affect acute changes in QoL during the ILI.29,30 The Newest Vital Sign is a health literacy screen used in healthcare settings. 31 Its questions pertain to the interpretation of a nutrition label to reliably and accurately measure health literacy. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) is a validated tool measuring caregivers’ perceived social support. 32

Sample Size

Our sample size of 260 was based on a standard of 15 to 30 participants for each potential variable to ensure that goodness of fit (R2) was not overestimated. This allowed us to include 8 to 16 variables, which is adequate for the number of potential predictors. The Care-QoL-ILI is a 7-point scale and prior work showed significant differences across multiple domains. 18 We assumed a conservative estimate of a mean difference of 0.8 and a standard deviation of 2.0, allowing for the identification of clinically important differences. 27 Our sample size, site location, and population demographics predicted a socioeconomically diverse sample.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize demographic data, illness characteristics, and QoL scores across sites. Care-QoL-ILI scores were calculated for each domain, as well in aggregate, with 7 being the highest (best) possible QoL and 1 being the lowest (worst). We used a linear mixed model to examine factors that are associated with Care-QoL-ILI domain and aggregate scores. Potential factors included demographic characteristics, health literacy, perceived social support, days of illness prior to presentation, and perception of disease severity. We compared models with and without adjustment for baseline health status as measured by the SF-12v2. Interactions of factors by time with P < .15 were included in the model along with main effects with other predictors and backward variable selection were conducted by removing the nonsignificant higher-order terms and then main effects. This step was repeated until all variables left in the model were significant (P < .05). Analysis was performed in SAS version 9.4.

Results

Demographics

Enrollment began on February 17, 2020 and was completed on May 7, 2021. Enrollment transitioned from in-person enrollment at the study sites to remote on April 17, 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. A total of 308 caregivers with previously healthy young children with ILI were enrolled across all sites (Supplemental material). Of those, 281 (91%) caregivers completed all study components. And 134 were enrolled from the EDs and 147 from the UCs. Table 1 shows demographics and Table 2 shows illness characteristics. There were no differences in demographics or disease characteristics among those enrolled who did or did not complete the study procedures.

Table 1.

Demographics and Household Characteristics.

| Total (%) | |

|---|---|

| N | 281 |

| Caregiver relationship to child | |

| Mother | 264 (93.9) |

| Father | 14 (5.0) |

| Grandmother | 3 (1.1) |

| Caregiver age (years) | |

| <20 | 7 (2.5) |

| 20-24 | 65 (23.1) |

| 25-29 | 75 (26.7) |

| 30-34 | 75 (26.7) |

| 35-39 | 42 (14.9) |

| 40-44 | 9 (3.2) |

| ≥45 | 1 (0.4) |

| Unspecified | 7 (2.5) |

| Caregiver highest education level | |

| Less than high school graduate | 18 (6.4) |

| High school graduate | 78 (27.8) |

| Vocation/tech training school | 12 (4.2) |

| Some college | 73 (26.0) |

| College graduate | 68 (24.2) |

| Postgraduate | 32 (11.4) |

| Household income (USD) | |

| Less than $5000 | 57 (20.3) |

| $5001 to $15 000 | 28 (10.0) |

| $15 001 to $30 000 | 54 (19.2) |

| $30 001 to $50 000 | 47 (16.7) |

| $50 001 to $75 000 | 24 (8.5) |

| $75 001 to $90 000 | 17 (5.7) |

| $90 001 to $119 999 | 24 (8.5) |

| More than $120 000 | 27 (9.6) |

| Not reported | 3 (1.1) |

| Race | |

| Asian | 4 (1.4) |

| White | 172 (61.2) |

| Black | 87 (31.0) |

| More than one | 10 (3.5) |

| Prefer not to answer | 7 (2.5) |

| Not reported | 1 (0.4) |

| Caregiver employment Status | |

| Employed | 181 (64.4) |

| Full time | 127 (45.2) |

| Part time | 54 (19.2) |

| Child gender | |

| Male | 150 (53.4) |

| Female | 131 (46.6) |

| Child age (years) | |

| Mean | 6.34 (2.1) |

| Median | 5.4 (1.8) |

| Child attends school/day care | 125 (44.5) |

| Total children in the home | |

| 1 | 99 (35.3) |

| 2 | 97 (34.5) |

| 3 | 56 (19.9) |

| 4 | 18 (6.4) |

| ≥5 | 4 (1.4) |

| Unspecified | 7 (2.5) |

Table 2.

Illness Characteristics.

| Total (%) | |

|---|---|

| Total | 281 |

| Child missed day care or school | 122 (43.4) |

| Day care/school days missed | |

| 1 | 27 (9.6) |

| 2 | 33 (11.7) |

| ≥3 | 50 (17.8) |

| Not specified | 12 (9.8%) |

| Prior visit to healthcare site | 181 (64.4) |

| Prior ED visits | |

| 1 | 78 (27.8) |

| 2 | 15 (5.3) |

| ≥3 | 8 (2.8) |

| Prior urgent care visits | |

| 1 | 95 (33.8) |

| 2 | 13 (4.6) |

| ≥3 | 3 (1.1) |

| Prior office visits | |

| 1 | 51 (18.1) |

| 2 | 13 (4.6) |

| ≥3 | 12 (4.3) |

| Caregiver missed work | 129 (45.9) |

| Work days missed | |

| 1 | 49 (17.4) |

| 2 | 37 (13.2) |

| ≥3 | 38 (13.5) |

| Unspecified | 5 (1.8) |

| Caregiver time caring for child | |

| The same | 34 (12.1) |

| Slightly more than usual | 87 (31.0) |

| Much more than usual | 160 (56.9) |

| Medical interventions | |

| IV fluids | 14 (5.0) |

| Antibiotics | 63 (22.4) |

| Breathing support (oxygen) | 11 (3.9) |

| Chest x-ray | 27 (9.6) |

| Breathing treatment (albuterol) | 18 (6.4) |

| Steroids | 23 (8.2) |

| Antivirals | 6 (2.1) |

| None | 165 (58.7) |

| Caregiver perception of illness severity | |

| Mildly sick | 39 (13.9) |

| Fairly sick | 125 (44.5) |

| Very sick | 92 (32.7) |

| Extremely sick | 11 (3.9) |

| Unspecified | 14 (5.0) |

| Days of illness prior to visit | |

| 1 | 71 (25.3) |

| 2 | 94 (33.5) |

| ≥3 | 112 (39.9) |

| Unspecified | 4 (1.4) |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; IV, intravenous.

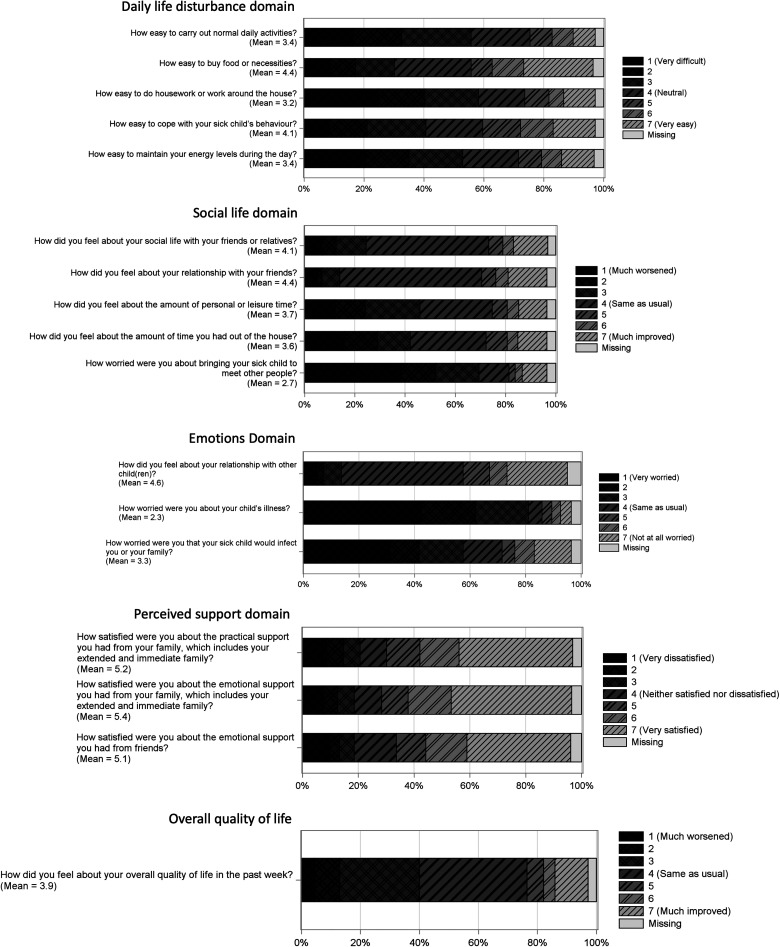

Care-QoL-ILI Scores

The distribution of responses to each question is shown in Figure 1. Table 3 summarizes the domain scores as measured by the Care-QOL-ILI instrument. And 41% of caregivers reported their overall QoL was worse or much worse than before the illness started. The median aggregate calculated caregiver QoL score across all sites was 3.8 [interquartile range 3.1, 4.6]. The median self-reported overall QoL was 4.0 [3.0, 4.0]. Wide variation was found in the individual domains that constitute the aggregate scores. The daily life disturbance and social life domains had modestly lower scores (3.6 and 3.4, respectively), while caregivers reported good scores in the perceived support domain (6.0). The median emotions domain score was 2.5 [1.5, 4.0], the worst of any domain.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Care-QoL-ILI scores by domain. Abbreviations: ILI, influenza-like illnesses; QoL, quality of life.

Table 3.

QoL Scores by Domain and in Aggregate.

| Domain | Mean (SD) | Median [Q1-Q3] |

|---|---|---|

| Daily life disturbance | 3.7 (1.54) | 3.6 [2.4, 4.8] |

| Perceived support | 5.2 (1.88) | 6.0 [4.0, 7.0] |

| Social life | 3.7 (1.30) | 3.4 [2.8, 4.2] |

| Emotions | 2.8 (1.58) | 2.5 [1.5, 4.0] |

| Overall QoL rating | 3.9 (1.52) | 4.0 [3.0, 4.0] |

| Aggregated QoL score | 3.8 (1.10) | 3.8 [3.1, 4.6] |

Abbreviations: QoL, quality of life; SD, standard deviation.

Factors Associated With QoL

Factors associated with QoL scores were identified for each domain and in aggregate. Health literacy, perception of severity of illness, duration of illness prior to presentation, and caregiver race were associated with differences in QoL scores. Adequate caregiver health literacy was associated with worse QoL in the Daily Life Disturbance domain. Within this domain, caregivers with adequate literacy had a lower mean score than those with limited literacy (3.08 vs 4.44, P < .0001).

Caregivers who perceived their child to be mildly sick had much higher mean daily life disturbance scores than those who perceived their child to be very sick (4.83 vs 3.87, P = .0065). Caregivers who perceived their child as very sick also had much lower scores in the Emotions domain as compared to those perceiving their child as not sick (2.61 vs 6.00, P = .0269). Differences in Emotion scores were significant across all categories of perceived illness severity (mildly sick, fairly, sick, very sick, and extremely sick).

Duration of illness prior to the index presentation was associated with differences in overall self-reported QoL. For each additional day of illness prior to presentation, the overall QoL score was lower by 0.128. Duration of illness was not associated with any differences in specific domains.

Caregiver race was associated with differences in the aggregate QoL and overall self-reported QoL scores. When QoL scores in all domains were aggregated, Black race was associated with higher QoL compared to White race (4.20 vs 3.68, P = .0006). When caregivers were asked to rate their overall QoL, Black race was associated with higher QoL (4.72 vs 3.43, P = .0278). Black race was associated with better QoL compared to White race in the Social Life domain (4.16 vs 3.43, P = .0001).

Household income level was not associated with QoL differences. No factors were associated with changes in the Perceived Social Support domain. The health status of the caregiver as measured by the SF-12v2 was not associated with QoL differences across the domains. Similarly, perceived measures of social support as measured by the MSPSS were not associated with QoL differences.

Standardized Cronbach's alpha was used to validate internal consistency for each domain. Consistency in the Daily Life Disturbance and Perceived Social Support domain were excellent at 0.92 and 0.93, respectively. Consistency in the Social Life domain was good (0.88), and satisfactory in the Emotions domain (0.7). 33

Discussion

This study is the first to quantify QoL in a diverse US population of caregivers of young children with ILI. High-quality pediatric PFCC requires an understanding of how caregiver wellbeing and QoL are affected by acute illnesses. In this study, we investigated this knowledge gap and found that caregivers in our population experienced QoL deficiency during their child's ILI. This study coincided with the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and the significant uncertainty regarding the social and medical aspects of the pandemic may have amplified changes in caregiver QoL. The Emotions domain constituted the lowest QoL, suggesting that caregivers reported substantial worry about their child's illness and contagiousness to the family. There was also wide variation in worry across caregivers. We also found an association between the caregivers’ perception of their child's illness with this domain. Our prior work found a lack of attention to this aspect in ED discharge instructions. 5 This finding suggests an area of opportunity to identify and address caregivers in which their worry about their child's illness is a key driving factor in health-seeking behavior and wellbeing.

Our findings may inform efforts to improve family-centered care by highlighting the modest but important impairments in caregiver QoL during childhood ILIs. Despite their relatively mild medical severity, ILIs affect family QoL in various domains and represent a substantial portion of primary care and ED visits yearly. Efforts to systematically identify caregiver QoL decrements could more precisely direct interventions to reduce emotional distress, refine caregivers’ judgment of disease severity and empower families to improve their wellbeing during childhood illnesses.

Our findings were similar to Chow et al in that lower QoL scores were associated with severity of illness (as perceived by the caregiver) and duration of illness. Overall QoL scores were also similar during the illness (3.87 vs 3.8). Our study emphasized the Chow findings that, within the Emotions domain, worry about the child's illness and spread to other children constituted a significant portion of worse caregiver QoL. Similarly, in a study of parental QoL during acute otitis media, Holl et al found aspects of QoL most affected during illness included worry and sleep and daily life disruption. 34 Our findings also confirm findings of these 2 studies; caregiver perception of more severe illness is associated with worse caregiver QoL. Results in our care sites (ED and UC) were similar to the outpatient clinic sites of the previous studies.

We found that better health literacy was associated with worse QoL in the Daily Disturbance domain. While caregivers with higher health literacy may be able to better transform health knowledge into healthy behaviors, this unexpected finding suggests that this ability does not necessarily mitigate the detrimental effects of a sick child on the daily functions of a household. The impact of health literacy on QoL is unclear, and within pediatrics, definitive linkages between health literacy and child health outcomes including QoL remain elusive.35,36 Our findings lend further credence to the need for further study to delineate the interplay between how caregiver health literacy affects household wellbeing, health-seeking behavior, and optimal PFCC. 37

In our analysis of factors associated with QoL differences, we found Black race was associated with higher QoL in the Social Life domain, overall QoL rating, and the aggregate QoL score. Household income and education were not associated with QoL differences. Socioeconomic, racial, and family contextual differences may modify the degree to which adverse experiences affect experienced QoL. Some studies have found the reported QoL differences favor White families and disfavor Black and Latino youth.20,38 Others report higher QoL in Black patients in various diseases and populations, as in our study.39,40 In addition to parental self-efficacy, coping and perception of severity of illness, further work is warranted to understand the contextual factors contributing to how the race of the caregiver modifies changes in caregiver QoL during acute childhood illnesses.41,42 Qualitative research to specifically explore these findings and more fully understand their implications is needed to inform further discussion.

Our study has several limitations. Although we recruited from multiple locations to diversify our sample, it was conducted in a single tertiary healthcare system. We were not able to compare QoL scores to caregivers of children without ILI. This could lead to factors other than the child's ILI influencing the caregiver QoL. However, this risk is mitigated by previous validation demonstrating good responsiveness of the Care-QoL-ILI to changes in QoL after the child's recovery and our use of the SF-12v2 to control for caregiver health status. 18 Further work is warranted to determine changes in QoL across a range of time points in families who present to multiple healthcare settings with children with ILI. This work was also conducted during the unique and specific contexts of the COVID-19 pandemic. While many aspects of health-seeking behavior and policies have remained postpandemic, the validity of our conclusions may be affected as we emerge from the pandemic. While the Care-QoL-ILI was rigorously validated, it was done so in Australia, where differing governmental and social support may limit generalizability in the United States. Finally, we only conducted our study in English, as the primary survey has not yet been validated in other languages.

Our study has implications for improving PFCC for common childhood illnesses. While we found wide variation in caregiver QoL, the greatest impairments were in areas of worry, daily life disturbance, and overall QoL. While further work is needed to clarify linkages between QoL and healthcare utilization, our findings highlight specific QoL impairments that clinicians in a variety of setting could address to improve PFCC. Additional studies to build upon our findings and provide a rich understanding of these effects could be used to derive utility indices for disease burden, improve patient experience, and optimize PFCC for acute childhood illnesses by systematically identifying decrements in caregiver QoL and effectively addressing aspects most important to families.

Conclusion

This is the first study to quantify caregiver QoL during their young child's ILI in a diverse US population. Caregiver QoL was lowest in the domain measuring worry about their child's illness and contagiousness to other children. Factors associated with worse QoL were the caregiver perception of severity of illness and duration of illness prior to presentation. Caregiver race also impacted QoL. Further study is warranted to investigate changes of caregiver QoL over the course of acute illnesses and identify optimal methods to address these changes to improve family-centered care and mitigate the impact of a child's acute illness on caregiver QoL.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-png-1-jpx-10.1177_23743735231188840 for Caregiver Quality of Life During Pediatric Influenza-Like Illness: A Cross-Sectional Study During the COVID-19 Pandemic by Kevin M Overmann, Stephen C Porter, Yin Zhang and Maria T Britto in Journal of Patient Experience

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Maria Yui Kwan Chow and Julie Leask for the use of the Care-QoL-ILI survey.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics Statement: The Institutional Review Board of Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center approved this study (IRB ID: 2019-1021).

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Kevin M Overmann https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4822-8018

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Dudley N, Ackerman A, Brown KM, et al. Patient- and family-centered care of children in the emergency department. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1):e255‐72. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Integrating Social Care into the Delivery of Health Care: Moving Upstream to Improve the Nation's Health. The National Academies Press; 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Lane MM. Health-related quality of life measurement in pediatric clinical practice: an appraisal and precept for future research and application. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2005;3(1):34. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-3-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Programme on mental health: WHOQOL user manual . 1998. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/77932

- 5.Overmann KM, Vukovic AA, Britto MT. A content analysis of emergency department discharge instructions for acute pediatric febrile illnesses: the current state and opportunities for improvement. J Patient Exp. 2021;8:23743735211060773. doi: 10.1177/23743735211060773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agborsangaya CB, Lau D, Lahtinen M, Cooke T, Johnson JA. Health-related quality of life and healthcare utilization in multimorbidity: results of a cross-sectional survey. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(4):791‐9. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0214-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butun A, Linden M, Lynn F, McGaughey J. Exploring parents’ reasons for attending the emergency department for children with minor illnesses: a mixed methods systematic review. Emerg Med J. 2019;36(1):39‐46. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2017-207118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Emergency Physicians , O'Malley P, Mace SE, Brown K. Patient- and family-centered care and the role of the emergency physician providing care to a child in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48(5):643‐5. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stille C, Turchi RM, Antonelli R, et al. The family-centered medical home: specific considerations for child health research and policy. Acad Pediatr. 2010;10(4):211‐7. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2010.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lambert SB, O'Grady KF, Gabriel SH, Nolan TM. Respiratory illness during winter: a cohort study of urban children from temperate Australia. J Paediatr Child Health. 2005;41(3):125‐9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2005.00561.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang J, Jit M, Zheng Y, et al. The impact of influenza on the health related quality of life in China: an EQ-5D survey. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):686. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2801-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bilcke J, Coenen S, Beutels P. Influenza-like-illness and clinically diagnosed flu: disease burden, costs and quality of life for patients seeking ambulatory care or no professional care at all. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e102634. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iskander M, Booy R, Lambert S. The burden of influenza in children. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007;20(3):259‐63. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3280ad4687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lovie-Toon YG, Chang AB, Newcombe PA, et al. Longitudinal study of quality of life among children with acute respiratory infection and cough. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(4):891‐903. doi: 10.1007/s11136-017-1779-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Varni JW, Limbers CA, Neighbors K, et al. The PedsQL Infant Scales: feasibility, internal consistency reliability, and validity in healthy and ill infants. Qual Life Res. 2011;20(1):45‐55. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9730-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Newcombe PA, Sheffield JK, Petsky HL, Marchant JM, Willis C, Chang AB. A child chronic cough-specific quality of life measure: development and validation. Thorax. 2016;71(8):695‐700. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mistry RD, Stevens MW, Gorelick MH. Health-related quality of life for pediatric emergency department febrile illnesses: an evaluation of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory 4.0 generic core scales. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7(1):5. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chow MY, Morrow A, Heron L, Yin JK, Booy R, Leask J. Quality of life for parents of children with influenza-like illness: development and validation of Care-ILI-QoL. Qual Life Res. 2014;23(3):939‐51. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0538-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Germain N, Aballea S, Toumi M. Measuring the health-related quality of life in young children: how far have we come? J Mark Access Health Policy. 2019;7(1):1618661. doi: 10.1080/20016689.2019.1618661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wallander JL, Fradkin C, Chien AT, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in health-related quality of life and health in children are largely mediated by family contextual differences. Acad Pediatr. 2012;12(6):532‐8. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2012.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monroe P, Campbell JA, Harris M, Egede LE. Racial/ethnic differences in social determinants of health and health outcomes among adolescents and youth ages 10-24 years old: a scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):410. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-15274-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goyal MK, Chamberlain JM, Webb M, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the delayed diagnosis of appendicitis among children. Acad Emerg Med. 2021;28(9):949‐56. doi: 10.1111/acem.14142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goyal MK, Johnson TJ, Chamberlain JM, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in antibiotic use for viral illness in emergency departments. Pediatrics. 2017;140(4). doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marin JR, Rodean J, Hall M, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in emergency department diagnostic imaging at US children's hospitals, 2016-2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(1):e2033710. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.33710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Congdon M, Schnell SA, Londono Gentile T, et al. Impact of patient race/ethnicity on emergency department management of pediatric gastroenteritis in the setting of a clinical pathway. Acad Emerg Med. 2021;28(9):1035‐42. doi: 10.1111/acem.14255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goyal MK, Kuppermann N, Cleary SD, Teach SJ, Chamberlain JM. Racial disparities in pain management of children with appendicitis in emergency departments. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(11):996‐1002. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chow MY, Yin JK, Heron L, et al. The impact of influenza-like illness in young children on their parents: a quality of life survey. Qual Life Res. 2014;23(5):1651‐60. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0606-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwarz N, Sudman S. Answering Questions, Methodology for Determining Cognitive and Communicative Processes in Survey Research. Jossey-Bass; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220‐33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheak-Zamora NC, Wyrwich KW, McBride TD. Reliability and validity of the SF-12v2 in the medical expenditure panel survey. Qual Life Res. 2009;18(6):727‐35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiss BD, Mays MZ, Martz W, et al. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: the newest vital sign. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(6):514‐22. doi: 10.1370/afm.405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52(1):30‐41. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walters SJ. Quality of Life Outcomes in Clinical Trials and Health-Care Evaluation: A Practical Guide to Analysis and Interpretation. Wiley, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Holl K, Rosenlund M, Giaquinto C, et al. The impact of childhood acute otitis media on parental quality of life in a prospective observational cohort study. Clin Drug Investig. 2015;35(10):613‐24. doi: 10.1007/s40261-015-0319-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DeWalt DA, Hink A. Health literacy and child health outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2009;124(Suppl 3):S265‐74. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1162B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zheng M, Jin H, Shi N, et al. The relationship between health literacy and quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16(1):201. doi: 10.1186/s12955-018-1031-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Riemann L, Lubasch JS, Heep A, Ansmann L. The role of health literacy in health behavior, health service use, health outcomes, and empowerment in pediatric patients with chronic disease: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(23):12464. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182312464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wallander JL, Fradkin C, Elliott MN, Cuccaro PM, Tortolero Emery S, Schuster MA. Racial/ethnic disparities in health-related quality of life and health status across pre-, early-, and mid-adolescence: a prospective cohort study. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(7):1761‐71. doi: 10.1007/s11136-019-02157-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cousino MK, Lim HM, Smith C, et al. Primary disease, sex, and racial differences in health-related quality of life in adolescents and young adults with heart failure. Pediatr Cardiol. 2022;43(7):1568‐77. doi: 10.1007/s00246-022-02884-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jackson I, Rowan P, Padhye N, Hwang LY, Vernon SW. Racial/ethnic differences in health-related quality of life among female breast cancer survivors: cross-sectional findings from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Public Health. 2021;196:74‐81. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodríguez EM, Kumar H, Alba-Suarez J, Sánchez-Johnsen L. Parental coping, depressive symptoms, and children's asthma control and school attendance in low-income, racially, and ethnically diverse urban families. J Asthma. 2017;54(8):833‐41. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2016.1274402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kan K, Fierstein J, Boon K, et al. Parental quality of life and self-efficacy in pediatric asthma. J Asthma. 2021;58(6):742‐9. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2020.1731825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-png-1-jpx-10.1177_23743735231188840 for Caregiver Quality of Life During Pediatric Influenza-Like Illness: A Cross-Sectional Study During the COVID-19 Pandemic by Kevin M Overmann, Stephen C Porter, Yin Zhang and Maria T Britto in Journal of Patient Experience