Abstract

Antenatal care is essential to promote maternal health. Prior research has focused on barriers women face to attending antenatal care, and improving quality of care is seen as a precondition for better attendance. Digital health tools are seen as a promising instrument to increase the quality of healthcare. It is less clear to what extent the use of digital health tools in low- and middle-income counties would be perceived as beneficial by end-users. The aim of this research was to explore women’s experiences with antenatal care, and whether digital health tools would change their perceptions of quality of care. This qualitative research utilised an interpretative phenomenological approach on data from semi-structured in-depth interviews collected in 2016 with 19 randomly selected pregnant women from six different dispensaries in Magu District. Findings showed that pregnant women are motivated to attend antenatal care and are grateful for the services received. However, they also articulated a need for improvements in antenatal care services such as the availability of diagnostic tests and more interactions with healthcare workers. Participants indicated that a digital health tool could help in storing patient files and improving communication with health workers. Our results indicate that pregnant women are positive about the use of digital health tools during antenatal care but that the implementation of such a tool should be implemented in parallel to structural service delivery improvements, such as testing availability.

Keywords: prenatal care, electronic clinical decision and support system, pregnant women, maternal health, quality of care

Résumé

Les soins prénatals sont essentiels pour promouvoir la santé maternelle. Les recherches se sont jusqu’à présent concentrées sur les obstacles auxquels se heurtent les femmes pour bénéficier de soins prénatals, et l’amélioration des soins est considérée comme une condition préalable pour une meilleure fréquentation des services. Les outils de santé numérique sont perçus comme des instruments prometteurs pour relever la qualité des soins de santé. On sait moins dans quelle mesure l’utilisation des outils de santé numérique dans les pays à revenu faible ou intermédiaire pourrait être jugée comme bénéfique par les utilisateurs finaux. L’objectif de cette recherche était d’explorer l’expérience des femmes en matière de soins prénatals, et de déterminer si les outils de santé numérique pourraient modifier leur perception de la qualité des soins. Cette recherche qualitative a utilisé une approche phénoménologique interprétative des données recueillies lors d’entretiens approfondis semi-structurés réalisés en 2016 avec 19 femmes enceintes sélectionnées de manière aléatoire dans six dispensaires différents du district de Magu. Les résultats ont montré que les femmes enceintes sont motivées pour se rendre aux consultations prénatales et sont reconnaissantes pour les services reçus. Néanmoins, elles ont aussi fait état de la nécessité d’améliorer les services de soins prénatals, avec par exemple la disponibilité de tests de diagnostic, et d’avoir davantage d’interactions avec les agents de santé. Les participantes ont indiqué qu’un outil de santé numérique pourrait aider à stocker les dossiers des patientes et améliorer la communication avec les agents de santé. Nos conclusions indiquent que les femmes enceintes jugent positive l’utilisation d’outils de santé numérique pendant les soins prénatals, mais que la mise en œuvre de ces outils devrait se dérouler parallèlement aux améliorations structurelles de la prestation de services, telles que la disponibilité de tests.

Resumen

La atención prenatal es esencial para promover la salud materna. Investigaciones anteriores se han enfocado en las barreras que enfrentan las mujeres para asistir a su cita de atención prenatal, y el mejoramiento de la calidad de la atención es considerado como una precondición para mejorar la asistencia a las citas. Las herramientas sanitarias digitales son percibidas como un instrumento prometedor para mejorar la calidad de los servicios de salud. Queda menos claro en qué medida el uso de herramientas sanitarias digitales en países de bajos y medianos ingresos sería percibido como benéfico por las usuarias finales. El objetivo de esta investigación era explorar las experiencias de las mujeres con la atención prenatal y determinar si las herramientas sanitarias digitales cambiarían sus percepciones de la calidad de la atención. Esta investigación cualitativa utilizó el enfoque fenomenológico interpretativo en datos de entrevistas a profundidad semiestructuradas recolectados en 2016 con 19 mujeres seleccionadas al azar de seis diferentes dispensarios en el Distrito Magu. Los hallazgos indican que las mujeres embarazadas están motivadas para asistir a sus citas de atención prenatal y agradecidas por los servicios recibidos. Sin embargo, ellas también expresaron la necesidad de mejoramientos a los servicios de atención prenatal, como la disponibilidad de pruebas de diagnóstico y más interacciones con trabajadores de salud. Los participantes indicaron que una herramienta sanitaria digital podría ser útil para guardar los expedientes de las pacientes y mejorar la comunicación con el personal de salud. Nuestros resultados indican que las mujeres embarazadas son positivas en cuanto al uso de herramientas sanitarias digitales durante la atención prenatal, pero que la aplicación de este tipo de herramienta debe realizarse en paralelo con los mejoramientos estructurales a la prestación de servicios: por ejemplo, la disponibilidad de pruebas.

Introduction

It is widely recognised that antenatal care (ANC) is a key intervention to promote maternal health.1–4 In low- and middle-income countries where maternal mortality rates remain high, ANC contains crucial components that can help to reduce maternal and infant morbidity and mortality1–4 and plays an important role in detecting high-risk pregnancies and managing pregnancy-related complications.3,5,6 In addition, women who receive ANC are more likely to deliver with a skilled birth attendant,3,6–8 which is considered to be the most effective intervention in reducing maternal mortality.9,10

In 2001, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended a minimum of four ANC consultations for all pregnant women, of which the initial visit should occur in the first trimester of pregnancy. These visits consist of several preventive interventions, such as tetanus toxoid immunisation, iron supplements, malaria prophylaxis, and deworming.1,2,6,11–13 These interventions are supplemented with health education as well as screening and treatment for complications, such as sexually transmitted infections.1,2,11–13 Since 2017, the WHO has shifted its focus to improve women’s experience of care and recommends eight ANC visits.4 However, many low- and middle-income countries have not yet implemented these new recommendations.

Tanzania implemented the model of four ANC visits recommended by the WHO in 2002.11 The coverage of at least one ANC consultation in Tanzania is promising, with 96% of pregnant women aged 15–49 receiving ANC from a skilled provider.14,15 However, in the national demographic and health survey of 2016, it was found that only 51% of women attended the recommended four ANC visits, and of these, only 24% schedule their initial ANC consultation in the first trimester of their pregnancy.14 This is worrying, since women who do not attend the recommended four ANC visits may miss essential information and interventions.1,7,13 In addition, women starting ANC late will receive interventions that are less effective as they are not provided in the right pregnancy trimester. For example, medication to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV loses efficacy if it is not started early in pregnancy.13 As a result, women and their infants face an increased risk of adverse health outcomes.1,7

Previous studies conducted in Tanzania described the experiences of pregnant women during ANC and examined the low uptake of the recommended four ANC visits, finding numerous barriers to attending maternal healthcare.1,6,16–18 In general, it has been shown that women acknowledge the benefit of receiving ANC but value this as less important than the barriers they experience.5,16,17 Barriers included difficulty in accessing health facilities due to bad road conditions,6,14,16,17 out-of-pocket expenditures,14,16,18 fear to undergo certain procedures,1 and lack of a male companion.1,14 In addition, it has been found that a pregnant woman’s decision to seek ANC is influenced by the perceived quality of care they expect to receive.19–21 Women experience long waiting times,16 poor communication about the return schedule,1 and disappointment over the received quality of care16–18 as barriers to seeking ANC. Therefore, any effort aimed at increasing the uptake of ANC should also focus on improving the quality of ANC.

Digital health tools may be promising to enable better quality care in low- and middle-income countries22–26 and several studies have demonstrated the effects of working with digital health tools in settings with limited resources.26–28 For example, it has been shown that digital tools are able to increase geographic access to care,23,29 and it can also help monitor the treatment adherence of patients.22 However, digital health tools are not a “silver bullet” to solve health systems challenges30,31 but can serve as an enabler to reach better health outcomes for patients.32 Careful evaluation of digital health tools is essential, since their feasibility, as well as benefits for both healthcare workers and patients, need to be explored.23,25,28,33,34

In an effort to reduce this research gap and contribute to the evaluation of digital tool uptake in maternal healthcare in Tanzania, The Woman-Centered Care Project (WCCP)35,36 developed a tablet-based digital health application to assist healthcare workers during ANC through step-by-step guidance through all necessary interventions and providing tailored advice and suggestions for follow-up actions when needed. This type of application is known as an electronic clinical decision and support system (eCDSS) of which a prototype was used for this study. The application was tablet-based and consisted of a comprehensive step-by-step questionnaire to be filled in by the healthcare worker during the ANC consultation at the healthcare facilities. In Tanzania, a paper-based ANC card is used for documentation and contains the information relevant to their pregnancy. The content of the eCDSS was the same as the ANC card and could therefore function as a replacement for the ANC card, with the main difference being the adjustability of the questions based on the results obtained during the consultation, and the signalling of abnormalities with an “alarm bell”. The design and development of the eCDSS and more information on the WCCP are provided in detail elsewhere.36

Although the development, implementation, and data collection regarding this eCDSS took place seven years ago, the research remains relevant as a recent study in Tanzania highlighted the continued lack of digital file and record keeping.37,38 This study explored acceptability of moving towards digitalisation in healthcare, finding that healthcare workers were supportive of digitalisation in healthcare.38 Also, studies evaluating patient experiences in low- and middle-income countries are still limited27,39–41 and robust studies assessing the effectiveness of digital health tools on health outcomes are scarce.27,34 Of the limited evidence available, one programme testing a digital health tool in three sub-Saharan African countries found that the communication with clients improved and women were invited to make informed choices, however, no significant improvement in the overall quality of the delivery of ANC was found.39,40 Another recent study conducted in Palestine found that, although healthcare workers have better adherence to ANC guidelines, pregnant women’s negative health outcomes did not decrease.27 One study in Ethiopia found that women experienced better information exchange between healthcare workers and pregnant women and that women trusted health advice more.42 Another study found no overall improvement in pregnant women’s satisfaction at the facilities where the digital health tool was used.34

The current research

The limited available research on the use of digital health tools in healthcare consultations generally reports positive results on quality improvement and patient satisfaction.23,29,42,43 It is less clear to what extent the introduction of digital health tools in maternal healthcare in low- and middle-income countries would be perceived as beneficial by beneficiaries and end-users, and whether such tools would modify women’s perceptions of (the quality of) ANC. To explore these perceptions, the aim of this study is two-fold: (1) to gain insight into the perceptions and experiences of pregnant women receiving ANC in Magu District, Tanzania and (2) to understand to what extent digital health tools are perceived as potentially beneficial for use during ANC consultations.

Methods

Study design

This qualitative research employed an interpretative phenomenological approach,44,45 drawing on semi-structured in-depth interviews to gain insight into lived experiences and perceptions of pregnant women receiving ANC in Magu District, Tanzania. This method has been described as “[…] a method which is descriptive because it is concerned with how things appear and letting things speak for themselves, and interpretative because it recognises there is no such thing as an uninterpreted phenomenon” (p. 7).46 Here, we utilised in-depth interviews because it allowed for detailed exploration of the contextualised personal perspectives on ANC of pregnant women, and the possibility for the respondent to freely elaborate on issues that are important to her.47

Study setting

This study was conducted in Magu District, one of the seven districts comprising Mwanza Region, and part of the Lake Zone in Tanzania. The study setting has been described in detail elsewhere.35,36 In brief, the Lake Zone has the highest maternal mortality rates in Tanzania (a total number of 176 maternal deaths in 2009) and is one of the regions with the highest percentages of women (46.6%) reporting problems in accessing healthcare.14,48 This formed the decision to conduct research in this District. This study was part of the Woman Centered Care Project (WCCP) of the African Woman Foundation, which had as the primary objective to improve maternal and neonatal health in Magu District.1 The development of an eCDSS was part of this objective, and the current study formed part of the needs assessment phase of intervention development.49,50

The WCCP mapped out that in Magu District, health services are delivered by 26 dispensaries, four health centres, and one district hospital.51 These different levels of health facilities vary in services provided, with the district hospital acting as the referral centre for all lower-level facilities. Dispensaries are the lowest level of health facilities and provide services mainly on an outpatient basis. In rural areas, dispensaries are the main access point for reproductive health services, including ANC.52 This study took place in six dispensaries across five wards.

Participants

To gain insight into pregnant women’s perception of ANC and their experiences with (the quality of) ANC in Magu district, in-depth interviews were conducted with pregnant women attending ANC care at the six dispensaries. These dispensaries were selected using purposive sampling based on geographic factors to represent the district as adequately as possible. In total, 19 women were randomly selected during ANC visits by the two research assistants, to collect the views and opinions of women representative of the population of pregnant women receiving ANC in the district.

Data collection

Data collection took place between January and March 2016 and in June 2016. The interviews took place in a private area allowing for a confidential discussion, either at a quiet place surrounding the dispensary (e.g. under a tree) or at the participant’s home, depending on the participant’s preference. Interviews were conducted by two members of the research team; a foreign research assistant who asked the questions in English and a local research assistant who translated to KiSwahili or into Sukuma, the regional language. To maximise credibility, two Dutch female research assistants were involved; both worked as a volunteer in the project as part of their master’s degree. They were paired with local research assistants who were employed in the project. As the foreign research assistants were aware of their outsider position, care was taken to allow the local research assistants they were paired with to explain the goal of the research and give clarifications in the local language as much as needed prior, during, and after the interview. All research assistants worked in close collaboration with the principal researcher and the local team members of the WCCP throughout the process of data collection and analysis to ensure insider perspectives were considered. Interviews took approximately 40 minutes. Participants provided informed consent to record the interview and transcribe the interview for subsequent analysis. After 19 in-depth interviews, no new information emerged from the interviews. Consequently, the research team decided that data saturation53 was reached and no further interviews were conducted.

Materials

Prior to the in-depth interviews, participants were asked to fill in a short demographic questionnaire about their age, level of education, occupation, marital status, number of children, number of pregnancies, gestational age of current pregnancy, number of current ANC visit, waiting time for current ANC visit, and estimated time spent in current ANC visit. For the in-depth interviews, a semi-structured interview guide was developed and discussed within the local research team of the WCCP (see Appendix for the overview). Questions focussed on women’s perceptions of (the quality of) ANC received in current and previous pregnancies, reasons to attend ANC, opportunities for improvement in ANC, their interpretation of digital health in relation to ANC, as well as their opinions about the use of such a tool during ANC. During the interviews, the prototype of an eCDSS was demonstrated on a tablet to ensure a basic understanding of digital health and help conceptualise the use of digital health tools during ANC.

Data analysis

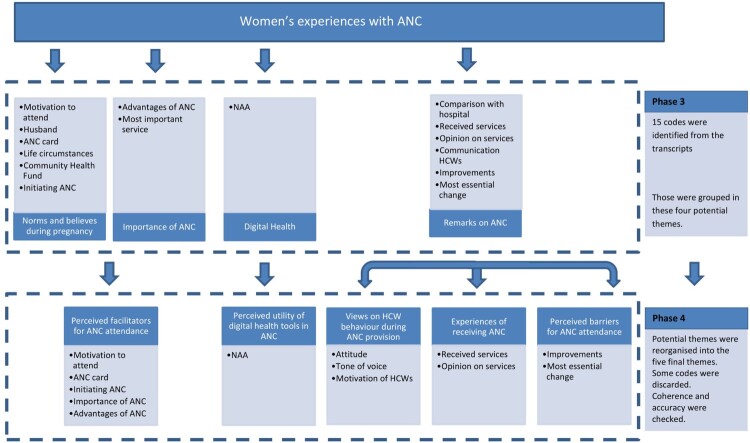

Data were analysed following the six phases of thematic analysis,53 which are presented in Table 2 accompanied by an example. To enable familiarisation with the data (Phase 1), each recording was attentively listened to and transcribed verbatim in English. To reduce interpretation biases and to ensure that inter-coder reliability was high, each transcript was read thoroughly several times by the foreign research assistants and the principal researcher and initial ideas were noted down. To generate initial codes (Phase 2), transcripts were read again several times and coded line by line using an inductive approach to create initial codes, making use of Atlas.ti 8.0 software. Subsequently, in Phase 3 initial codes were grouped into potential themes by looking at the mutual relationships between codes. For example, the initial codes advantages of ANC and most important service were grouped in the potential theme Importance of ANC. This process resulted in four potential themes. Next, in Phase 4, the coding scheme and potential themes that were independently identified by the research assistants and the first author were compared, and, to maximise inter-coder reliability, adjustments were made until consensus was reached about the final set of themes.

Table 2.

Phases of thematic analysisa

| Phase | Description of the process | Example |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Familiarising yourself with data | • Interviews were transcribed verbatim • Transcripts were thoroughly read several times • Initial ideas were noted down |

“because the healthcare workers are speaking nicely, they are not speaking like shouting” |

| 2. Generating initial codes | • Transcripts were coded line by line • Initial codes were grouped • 15 codes were identified: ANC card, most essential change, eCDSS, life circumstances, most important service, communication of HCWs, received services, husband, motivation to visit, improvements, comparison with hospital, opinion on received services, initiating ANC, advantages ANC, community health fund |

Initial code: communication of HCWs |

| 3. Searching for themes | • Codes were grouped into potential themes • Four potential themes were created: Norms and believes during pregnancy, Importance of ANC, Digital health, and Remarks on ANC |

Potential theme: remarks on ANC |

| 4. Reviewing themes | • Themes were checked for coherence • Individual work was compared and consensus reached • Themes were checked for accurate representation of data • Visual presentation of themes was made (Figure 1) • Themes were reorganised into 5 themes. Codes that did not fit within an existing theme and were not relevant for a new theme were discarded from the analysis |

Theme: Healthcare worker communication Subtheme: Tone of voice |

| 5. Defining and naming themes | • Specifics of each theme was decided on • Themes were checked for accurate content • Names were generated for each theme: (1) Experiences of receiving antenatal care (2) Perceived facilitators for antenatal care attendance (3) Perceived barriers to antenatal care attendance (4) Views on healthcare worker behaviours during antenatal care provision (5) Perceived utility of digital health tools in antenatal care. |

Final theme: Views on healthcare worker behaviours during antenatal care provision |

| 6. Producing the report | • Results were related to the research questions and literature • Quotes were selected from the transcripts to present in the report |

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101.

The codes were reorganised into five themes. Codes that did not fit within an existing theme and could also not be placed in a new theme were discarded from the analysis. Figure 1 presents a visual overview of the themes and how potential themes evolved into final themes. In Phase 5, the interview parts that were related to each of the themes were read again to verify the essence of the topic and to check for accuracy in the specific story of the team, which ultimately resulted in five final themes: (1) Experiences of receiving antenatal care, (2) Perceived facilitators for antenatal care attendance, (3) Perceived barriers to antenatal care attendance, (4) Views on healthcare worker behaviours during antenatal care provision, and (5) Perceived utility of digital health tools in antenatal care. Finally, in Phase 6, the results of the analysis were related to the aims of the research, and all interview parts forming the five themes were read again for writing the results. Quotes were selected to illustrate the results, making sure a variety of participants and perspectives were taken into account. The demographic questions were analysed to create an overview of the sample.

Figure 1.

Visual presentation of the process moving from codes to potential themes (Phase 3) to final themes (Phase 4)

Ethics and consent

Approval for this study was obtained from the National Institute of Medical Research of Tanzania on 16 March 2016 (MR/53/100/103-244-245-349-399) and Maastricht University in the Netherlands on 3 February 2021 (OZL_188_10_02_2018_S32). The district medical authority gave permission to conduct the study in their area. Before each interview, the local research assistant explained the purpose of the study to the participant, and they were asked to read and sign a written consent form. In case the participant was not able to read, the consent form was read out loud by the local research assistant. Participants were assured of confidentiality and reminded that their participation in the study was voluntary and that they could stop the interview at any time or withdraw their consent to have their data used in the research.

Results

Nineteen pregnant women, aged 16–38, participated in semi-structured in-depth interviews. Most participants were between 20 and 24 years of age, completed primary school, were married, were farmers or otherwise worked in agriculture, and already had children. The socio-demographic characteristics of the participants are summarised in Table 1. Results will be described according to the five themes: (1) Experiences of receiving antenatal care (positive experiences; unmet needs) (2) Perceived facilitators for antenatal care attendance (receiving health checks; social norms) (3) Perceived barriers to antenatal care attendance (lack of (free) services; poor infrastructure) (4) Views on healthcare worker behaviours during antenatal care provision (interpersonal behaviour; responsibilities), and (5) Perceived utility of digital health tools in antenatal care (advantages; disadvantages).

Table 1.

Socio-demographics of participants

| Variable | Number of participants |

|---|---|

| Age in years | |

| 16–20 | 3 |

| 20–24 | 10 |

| 25–29 | 4 |

| >29 | 2 |

| Number of children | |

| 0 | 3 |

| 1–2 | 10 |

| 2–4 | 5 |

| unknown | 1 |

| Number of current ANC visit | |

| 1 | 6 |

| 2 | 7 |

| >2 | 6 |

| Total number of ANC visits in the past | |

| 1–2 | 3 |

| 3–4 | 1 |

| 5–6 | 6 |

| 7–8 | 3 |

| >8 | 6 |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 1 |

| Married | 17 |

| Divorced | 1 |

| Education | |

| Lower primary school | 2 |

| Upper primary school | 16 |

| Junior secondary school | 1 |

| Occupation | |

| Farmer | 16 |

| Housewife | 1 |

| Other | 2 |

Theme 1: Experiences of receiving antenatal care

Positive perceptions

All participants felt grateful for the provided ANC services in the District, and most of them stated that they felt they received good care. When they were asked to explain what they meant with good care, the pregnant women defined this as the sum of services they received, such as weight measurement, blood testing, and abdominal examination:

“The treatment are (sic) good, there is nothing to add”. (Participant 2402)

“For the facility, there are some services which are always provided to us. First is weight, height and also HIV tests and to observe the lie of the baby. These are the things we always get when we go there”. (Participant 2602)

Unmet needs

However, several women indicated that they felt they received poor ANC at the health facility. For example, one woman stated that she was refused services as she had not come with her husband. Others revealed that they felt that the care they received was not in line with the needs of pregnant women to ensure a safe pregnancy:

“In general the services is (sic) not good, is very poor for the pregnant mama […] there is only the testing for malaria and HIV and no other tests like blood pressure or blood group”. (Participant 1305)

Moreover, although most women did not clearly express dissatisfaction with ANC, many described challenges related to the availability of materials in the ANC clinic, such as tests or medication. Other participants commented on being tested but not provided with the results of the tests or sufficient explanation of the test results:

“I don’t know what’s wrong but maybe they do not have time […] you can be tested only, and they are not going to give you the results, they just tell you, oh you can go, that way. I would like to know the results […] yes it is really important for me to know what is going on, rather than told (sic) me that I have to go home, only that is not enough, they have to explain to me”. (Participant 0703)

Theme 2: Perceived facilitators for antenatal care attendance

Receiving health checks

Almost all participants expressed that the most important reason to attend ANC was to learn about their health status and the health of their unborn baby, as well as to be reassured about the progress of the pregnancy. Women also pointed out that they felt it was important for them to undergo blood tests, such as diagnostic tests for malaria and HIV, and to receive medication when needed:

“I go to test my health and to know the condition of the baby inside […] if there are any problems the healthcare workers can let me know […]”. (Participant 2402)

Social norms

Another important reason mentioned by participants was the expectation of family members and relatives. Women clarified that they are expected to go to the clinic when they become pregnant and that they follow the example of other women receiving ANC:

“[…] any other woman, when they realise they are pregnant, they always went to the clinic. I am not sure what’s going on there but I am supposed to go there”. (Participant 0803)

“Nurses and also in the radios they say about attending ANC early (sic)”. (Participant 2705)

Furthermore, women stated that healthcare workers urge pregnant women to visit the ANC clinic either in the community or at healthcare facilities during other visits (e.g. during a previous pregnancy or non-pregnancy-related visit). Several participants indicated that they were worried that healthcare workers get angry when they find out that women do not attend ANC. In addition, several women explained the need for receiving an ANC card (in Tanzania, a paper-based ANC card is used for documentation and contains the information relevant to their pregnancy) during their visit, because they believed it enabled them to get access to good delivery care and would appease the healthcare workers. Pregnant women are responsible for keeping and bringing their ANC card every time they visit the health facility:

“When I went for ANC, it is very nice because I am going to get an ANC card […] because if you do not have an ANC card, it is a problem […] they will provide you with services (if you don’t have an ANC card) but in a harsh way, because they always ask why you didn’t come for ANC […] that is why the card is very important because it may avoid all this situation”. (Participant 0703)

Theme 3: Perceived barriers to antenatal care attendance

Lack of (free) services

Most participants articulated the need for more free medication when needed and the availability of blood tests during ANC. For example, women described that medication was often prescribed and they were told to buy it at the pharmacy, instead of these medications being given to them for free.* Other participants indicated that they were told to come back the next month in order to receive medication and blood tests because they were out of stock. Several of the participants suggested they felt it was necessary to hire more healthcare workers since they acknowledged the high workload for healthcare workers and complained about the long waiting times:

“When there is an emergency during the night, a pregnant mama that wants to deliver during the night, there is only one healthcare worker. So when we go there to wake him up, he is not friendly because it is night […] mama is having a risky situation”. (Participant 1305)

Poor infrastructure

Some women additionally expressed barriers related to building infrastructure, for example, having a reliable source of light, or more housing options close to the clinic to house healthcare workers, to ensure that someone would be present if a woman had to deliver their baby at the health facility in the night:

“The building is not enough, including houses for healthcare workers, and also for the other services including antenatal care […] you may find that maybe you have someone who is very sick and she needs an emergency services (sic) and you went there you find no one so you have to walk for a long distance to maybe to the houses […] it will be very difficult in such a situation […] there is a need to have enough buildings, enough houses for healthcare workers”. (Participant 0103)

Theme 4: Views on healthcare worker behaviours during antenatal care provision

Interpersonal behaviour

Women mentioned that healthcare workers provided “good care”, whereas some stated that healthcare workers can get angry when their rules are not followed by patients. One participant gave an example of a healthcare worker shouting at her because she did not bring her ANC card and another woman expressed that she was worried she had not complied with regulations:

“If you have a problem maybe, you didn’t go maybe on the exact date, so you are going to feel like ‘ahh they are going to tell me today […]’ because they are going to shout at you a lot”. (Participant 2402)

When participants were asked what they meant with healthcare workers providing “good” care, they answered that they were treated in a nice and polite way and not scolded. Thus, they referred more to the way the care was delivered rather than the nature of the care itself:

“Because the healthcare workers they speaking (sic) to them nicely, they are not speaking like shouting”. (Participant 2705)

Responsibilities to perform

In general, women explained that they perceived that the healthcare workers were willing to provide good service within the existing environmental limitations of the unavailability of medication and tests. They also indicated they felt that the healthcare workers were not the ones responsible for these problems. On the other hand, about one-third of the participants mentioned that healthcare workers should perform better. One of the participants questioned if blood tests were not available, or that healthcare workers were just not willing to perform tests. Two participants indicated that they wished that healthcare workers worked harder in general, and three women stated they felt that the knowledge level of the healthcare workers was not sufficient to monitor the health of pregnant women closely:

“No, I don’t think that healthcare workers know enough […] it is a limit (sic) of their knowledge to provide such services […] this is because of the shortage of healthcare workers and the shortage of the tests […] they care and they are friendly”. (Participant 1305)

Theme 5: Perceived utility of digital health tools in antenatal care

Advantages

The overall response of women towards the use of digital health tools during ANC was positive, especially when they understood what the application could do after the demonstration of the prototype. Most of them stated that the use of digital health tools would result in better care in general, and about half of the participants expressed that they thought the application would enhance better record-keeping or would help the healthcare workers in their work:

“I would feel happy because the one (the application) with many questions is good, rather than now just lay there and they just measure and you go […] healthcare workers will increase their awareness on that they should do […] because it will bring information which is correct”. (Participant 2705)

Several participants voiced that using digital health tools during ANC could stimulate the exchange of information between healthcare workers and women so that pregnant women are more informed about procedures and the results of the tests. A few others mentioned that such a device would enhance the correctness of their health information, the comprehensiveness of this information, as well as make the visit shorter in duration:

“There is an exchange of information and even I will then be able to read it so now I know that what I am supposed to do according to the report that is coming from the app […] if they have this kind of things and healthcare workers try to explain to us, it would be OK”. (Participant 1305)

Disadvantages

Most women would give permission to the healthcare worker to work with the digital health tool, but when asked what they would choose when given a choice between the tool and the traditional ANC card, only half of them would choose the digital health tool. Most participants explained that this was because they needed the ANC card to read at home and to get access to other service points where no digital health application was used.

“I choose tablet, with also ANC card because they may fill maybe (sic) some of the information, to my ANC card. So even if I am home I can look and read and then at the same time the other or the same information will be found (sic) on the tablet”. (Participant 0803)

Most of the women had difficulties in formulating negative aspects of receiving ANC with the device because they had not seen it before. However, several women were able to explain what they thought was needed to make it a success: they suggested healthcare worker training, sufficient and reliable electricity at the health facility to charge the tablets, proper information about the application for the community, and a safe place to store the tablets to avoid damage and stealing.

Discussion

The main aim of this study was to explore pregnant women’s perceptions and experiences of ANC in Magu District, Tanzania. Furthermore, we explored whether digital health tools are perceived as beneficial for use during ANC consultations. The results of this study indicate that in general, women interviewed were positive about the importance of ANC, and they were grateful for the services received such as blood tests or vaccinations. However, they also expressed a need for improvements in ANC services, and they indicated that a digital health application could help in improving care.

One of the themes that emerged from the analysis related to perceived facilitators to attend ANC (Theme 2). Our results indicate that participants mainly utilised ANC for two reasons: to understand their health status and the status of the pregnancy and because of societal expectations that dictate that attending ANC is an appropriate process to follow during pregnancy. In addition, there is an instrumental motive to attend ANC because they receive the ANC card, which gives them access to other services as well. These findings are in line with previous studies.3,7,16,54 For example, in Tanzania, Gross et al.7 found that women’s motivation to attend ANC was mostly due to norms and rituals, and less related to their personal health benefits. However, Gross et al7 also identified that the perceived poor quality of care of ANC was one of the reasons for women to attend ANC late (or not at all), which underscores that women take the quality of care they receive into account.

Although women did not explicitly state that the quality of care they received was poor, the current study also found that participants did express some concerns about the quality of care, specifically in relation to their experiences of receiving ANC (Theme 1), the perceived barriers to attending ANC (Theme 3), and their views on healthcare workers’ behaviours and responsibilities (Theme 4). Specifically, they noted poor availability of diagnostic tests, as well as the low motivation of healthcare workers. This is in line with the findings of other studies on ANC.1,3,5,16,18,20,55 Previous research on healthcare workers’ perceptions of the quality of ANC in Magu District indicated a lack of motivated healthcare workers providing ANC,50,56 which is in line with the experiences of our participants. Furthermore, participants mentioned they were often obliged to buy medication, despite the policy of the Ministry of Health to provide free medication. Healthcare workers obliging women to buy their medication is a well-known issue in Tanzania, as also identified in other studies.1,7,16,18

In addition to the criticism of having to buy their medication, the women expressed diverging feelings towards healthcare workers. On the one hand, women stated that healthcare workers were polite, provided good care, and were perceived as willing to deliver quality care during the ANC visits (Theme 4). On the other hand, women described that healthcare workers were sometimes angry, unreliable, did not provide high-quality care, and did not give sufficient and relevant information to pregnant women (Theme 1 and 4). For example, they sometimes did not provide test results to the women. These divergent views are consistent with previous research on interactions between women and healthcare providers in Tanzania.3,16,18 One potential explanation for these diverging feelings might be that some women were reluctant to share their negative views during the interviews, reflecting socially desirable answers.57 However, once the interview progressed, women often felt comfortable opening up.57 Another possible explanation is the role and position of patients (in our case women) in relation to their healthcare worker in Tanzanian society. Women might feel that they need to accept and be grateful for the care they received,21 or may not be aware of their (reproductive) rights and therefore do not easily express critique. The observation that about half of the women in the current study were able to express their concerns about the perceived quality of ANC, might thus be a sign of the urgent need to improve the situation.

As reflected by Theme 5, we also explored women’s perceptions of the possibility of including digital health tools in ANC services, with the aim to increase the quality of care. Participants in this study had little knowledge about the use of mobile technology in general, and poor access to tablets like the one used during the interviews to demonstrate the prototype. Despite this knowledge and experience gap, pregnant women generally expressed a positive attitude towards the use of such an application during the ANC visit. Women felt their care could be improved by the device due to its ability to store information and guide healthcare workers in care delivery. In addition, women reported expecting an increase in the quality of communication with the healthcare workers, and in the correctness of the information they received. Similar findings were reported by Mitchell et al.58 in a study of the use of electronic protocols for the assessment of children younger than five years of age in health facilities in Tanzania. Caretakers whose children received care from healthcare workers using an electronic device reported improved services, more thorough services, improved communication, and they considered healthcare workers to be more knowledgeable and able to provide better diagnoses.58

In low-resource settings, digital health interventions are often offered through patients’ mobile phones to deliver health education and behaviour change communication. There is some evidence for the effectiveness of these interventions in increasing ANC attendance.28,59,60 However, there has been less focus in the literature on eCDSS and its effects, not only on ANC attendance but on other outcomes including uptake and user experience by patients and healthcare workers.61 To our knowledge, the only three studies investigating clients’ perspectives on eCDSS all found diverse reactions of pregnant women to the use of an eCDSS during ANC.34,41,42 In a study conducted in Ghana, some women reacted with fear towards the device while others felt heard and listened to.41 The studies also indicated improved women-provider interactions due to the eCDSS.41,42 The current study shows similar findings in terms of women’s perception of the use of eCDSS, substantiating the potential of the role of eCDSS in providing ANC.

Methodological considerations

Although the results of this study provide valuable findings that might be used as a starting point for the development of interventions such as an eCDSS to promote the quality of ANC, a number of limitations need to be considered. This study was based on a relatively small sample of pregnant women attending different dispensaries in Magu District. Although similar results have been found in other rural areas, the findings may not be a clear representation of the entire population seeking ANC in Tanzania and transferability to all of Tanzania or low-income countries must be made with caution. Also, we sampled only women who had attended ANC consultations at the health facility, which excludes the valuable perceptions of women who do not seek ANC. This carries a risk of bias as included pregnant women already see the value of ANC and therefore may be more positive about the importance of ANC. Nevertheless, our sample represents a well-experienced group of pregnant women with a broad variety in the number of ANC consultations attended. Although we took care to select translators who were trained professionally in the translation between Kiswahili and English and had a general understanding of the regional language Sukuma, different dialects of Sukuma between villages might have been possible. Most participants were of Sukuma ethnicity and spoke Sukuma as their first language, with Kiswahili second. It might also have been possible that participants experienced a power imbalance due to the difference in education level with the interviewer. In this study, it was evident that participants had limited understanding of and experience with digital health tools, which may have contributed to a belief that digital health tools improved the quality of services due to the novelty effect of using new, high-cost technology.41,62 However, this should not be used as an argument to view these perceptions as having less value. Including the perspectives of end-users of digital health tools is essential in the process of developing and implementing digital health tools that fit local needs.

Conclusion

This study shows that circumstances in and around the health facility, like the availability of diagnostic tests and other materials, need to be improved to create a better environment for ANC provision for both women and healthcare workers. Although it is evident that these issues in infrastructure deserve attention, the study also found clear concerns of women related to the interaction with healthcare workers. In order to improve ANC in Magu District, Tanzania, more attention should be paid to the attitude of healthcare workers by emphasising the need for respectful care provision in education programmes and providing local training for healthcare workers in the field. The use of digital health tools in maternal healthcare seems promising, as this study found a positive view of pregnant women who believe digital health tools might improve communication with healthcare workers. Further research is needed to examine whether digital tools in ANC can help to increase ANC attendance and subsequently improve pregnancy and childbirth-related outcomes. Including end-users in such future research is important to ensure their voices are heard.

Appendix.

Appendix: Interview guide

| Themes | Questions |

|---|---|

| Antenatal care | > Why do you go for ANC? • In what way does ANC help you and your baby? > How do you decide when to go to the clinic for the first time? > How do you experience ANC visits? • What was done in your ANC visit today? > What is in your opinion the most important service that should be provided during ANC visits? > What do you think about the HCW who provide the ANC care? What do you like about the care they provide? • What don’t you like about the care they provide? What can they do differently? • What is the difference between the care they provide here and at the hospital? > What do you think is needed to improve the quality of the ANC visits? • Are there any services you miss? |

| Antenatal care - new ideas | > What do you think about the ANC card? > Can you think of other methods of doing an ANC visit instead using the just the ANC card? > How would you feel about an ANC visit that involves more extensive questions and tests than the ANC visit you receive now? > How do you feel about the use of electronic devices to support ANC visits? |

| Digital health | > How would you feel about the use of an electronic device during ANC visits that contains a questionnaire with health care questions to determine your health status during pregnancy? (Show prototype) • What would you like about the tablet? • What would you not like about the tablet? > Would you give consent to use such a device during an ANC visit? > What should definitely be included in such an ANC visit? (Questions, explanations or tests) > What would you expect with regard to the quality of ANC care if HCW would use such an electronic device? > If you could choose to be seen during ANC by a HCW that did use the tablet versus one that did not use the tablet, which one would you choose, and why? > What is needed to make the implementation of this tablet successful? |

| End question | > If you could change one thing about ANC visits, what would it be? > Do you have any other remarks you feel are important about ANC or the HCW? |

Footnotes

In Tanzania, maternal healthcare is funded by the Ministry of Health and therefore free of charge for all pregnant women visiting governmental health facilities for ANC; this includes any necessary medication or supplements.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- 1.Callaghan-Koru JA, McMahon SA, Chebet JJ, et al. A qualitative exploration of health workers’ and clients’ perceptions of barriers to completing four antenatal care visits in Morogoro Region, Tanzania. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31(8):1039–1049. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czw034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kerber KJ, De Graft-Johnson JE, Bhutta ZA, et al. Continuum of care for maternal, newborn, and child health: from slogan to service delivery. Lancet. 2007;370(9595):1358–1369. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61578-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mrisho M, Obrist B, Schellenberg JA, et al. The use of antenatal and postnatal care: perspectives and experiences of women and health care providers in rural southern Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9(10):1–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-9-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. 2016. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549912. [PubMed]

- 5.Finlayson K, Downe S.. Why do women not use antenatal services in low- and middle-income countries? A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta S, Yamada G, Mpembeni R, et al. Factors associated with four or more antenatal care visits and its decline among pregnant women in Tanzania between 1999 and 2010. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(7):e101893. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gross K, Alba S, Glass TR, et al. Timing of antenatal care for adolescent and adult pregnant women in south-eastern Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12(16):1–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bishanga DR, Drake M, Kim Y-M, et al. Factors associated with institutional delivery: findings from a cross-sectional study in Mara and Kagera regions in Tanzania. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(12):e0209672–15. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0209672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell OMR, Calvert C, Testa A, et al. The scale, scope, coverage, and capability of childbirth care. Lancet. 2016;388(10056):2193–2208. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31528-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, Ifakara Health Institute, National Institute for Medical Research, & World Health Organization . Midterm analytical review of performance of the health sector strategic plan III 2009–2015. 2013. Available from: https://www.who.int/healthinfo/country_monitoring_evaluation/TZ_AnalyticalReport_2013.pdf.

- 11.Kearns A, Hurst T, Caglia J, et al. Focused antenatal care in Tanzania Delivering individualised targeted, high-quality care. Women and Health Initiative, Maternal health Task force, Harvard School of Public health. 2014. Available from: https://cdn2.sph.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/32/2014/09/HSPH-Tanzania5.pdf.

- 12.Nyamtema AS, Jong AB, Urassa DP, et al. The quality of antenatal care in rural Tanzania: what is behind the number of visits? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2012;12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-12-70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization, United Nations Population Fund, & United Nations Children’s Fund . 2006. Pregnancy, childbirth, postpartum and newborn care: a guide for essential practice. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/249580/9789241549356-eng.pdf?sequence=1. [PubMed]

- 14.Ministry of Health Community Development Gender Elderly and Children, Ministry of Health, National Bureau of Statistics, Office of the Chief Government Statistician, & ICF . 2016. Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey and Malaria Indicator Survey 2015-2016. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR321/FR321.pdf.

- 15.Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elderly and Children . 2016. The National Road Map Strategic Plan to Improve Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health in Tanzania (2016-2020) - One Plan II. Available from: https://www.globalfinancingfacility.org/sites/gff_new/files/Tanzania_One_Plan_II.pdf.

- 16.Mahiti GR, Mkoka DA, Kiwara AD.. Women’s perceptions of antenatal, delivery, and postpartum services in rural Tanzania. Glob Health Action. 2015;8(1):28567. doi: 10.3402/gha.v8.28567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mubyazi GM, Bloch P, Magnussen P, et al. Women’s experiences and views about costs of seeking malaria chemoprevention and other antenatal services: a qualitative study from two districts in rural Tanzania. Malar. J. 2010;9(54):1–13. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-9-54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tancred T, Schellenberg J, Marchant T.. Using mixed methods to evaluate perceived quality of care in southern Tanzania. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016;28(2):233–239. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzw002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bishanga DR, Massenga J, Mwanamsangu AH, et al. Women’s experience of facility-based childbirth care and receipt of an early postnatal check for herself and her newborn in Northwestern Tanzania. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(481):481–416. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16030481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mselle LT, Moland KM, Mvungi A, et al. Why give birth in health facility? Users’ and providers’ accounts of poor quality of birth care in Tanzania. BMC Health Serv Res, 2013;13. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solnes Miltenburg A, Lambermon F, Hamelink C, et al. Maternity care and Human Rights: what do women think? BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2016;16(17):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12914-016-0091-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blaya JA, Fraser HSF, Holt B.. E-health technologies show promise in developing countries. Health Aff. 2010;29(2):244–251. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis T, Synowiec C, Lagomarsino G, et al. E-health in low- and middle-income countries: findings from the Center for Health Market Innovations. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90(5):332–340. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.099820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noordam AC, Kuepper BM, Stekelenburg J, et al. Improvement of maternal health services through the use of mobile phones. Trop Med Int Health. 2011;16(5):622–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02747.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization . mHealth: new horizons for health through mobile technologies. Based on the findings of the second global survey on eHealth. 2011. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44607/9789241564250_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- 26.Bervell B, Al-Samarraie H.. A comparative review of mobile health and electronic health utilization in sub-Saharan African countries. Soc Sci Med. 2019;232; doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.04.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Venkateswaran M, Ghanem B, Abbas E, et al. A digital health registry with clinical decision support for improving quality of antenatal care in Palestine (eRegQual): a pragmatic, cluster-randomised, controlled, superiority trial. Lancet Digit Health. 2022;4(2):e126–e136. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(21)00269-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feroz A, Perveen S, Aftab W.. Role of mHealth applications for improving antenatal and postnatal care in low and middle income countries: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(704):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2664-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kahn JG, Yang JS, Kahn JS.. ‘Mobile’ health needs and opportunities in developing countries. Cell Phones M-Health. 2010;29(2):252–258. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Battle JD, Farrow L, Tibaijuka J, et al. mHealth for safer deliveries: a mixed methods evaluation of the effect of an integrated mobile health intervention on maternal care utilization. Healthcare. 2015;3:180–184. doi: 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2015.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eze E, Gleasure R, Heavin C.. Reviewing mHealth in developing countries: a stakeholder perspective. Procedia Comput Sci. 2016;100:1024–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2016.09.276 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mechael P, Batavia H, Kaonga N, et al. Barriers and gaps affecting mHealth in low and middle income countries : Policy [White Paper]. Center for Global Health and Economic Development, The Earth Institute, Columbia University. 2010. Available from: https://www.ghdonline.org/uploads/Barriers__Gaps_to_mHealth_in_LMICs_-_White_Paper_-_May_2010.pdf.

- 33.Carter J, Sandall J, Shennan AH.. Mobile phone apps for clinical decision support in pregnancy: a scoping review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2019;19(1): doi: 10.1186/s12911-019-0954-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aninanya GA, Otupiri E, Howard N.. Effects of combined decision-support and performance-based incentives on reported client satisfaction with maternal health services in primary facilities: a quasi-experimental study in the Upper East Region of Ghana. PLoS One, 2021;16(4). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0249778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Solnes Miltenburg A, Van Pelt S, De Bruin W, et al. Mobilizing community action to improve maternal health in a rural district in Tanzania: lessons learned from two years of community group activities. Glob Health Action. 2019;12:1621590. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2019.1621590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Pelt S, Massar K, Shields-Zeeman L, et al. The development of an electronic clinical decision and support system to improve the quality of antenatal care in rural Tanzania: lessons learned using Intervention Mapping. Front Public Health. 2021;9; doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.645521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Unkels R, Alwy Al-Beity F, Julius Z, et al. Understanding maternity care providers’ use of data in Southern Tanzania. BMJ Glob Health. 2023;8(1): doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2022-010937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Unkels R, Manzi F, Kapologwe NA, et al. Feasibility, usability and acceptability of a novel digital hybrid-system for reporting of routine maternal health information in Southern Tanzania: a mixed-methods study. PLOS Global Public Health . 2023;3(1).doi: 10.1371/journal.pgph.0000972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mensah N, Sukums F, Awine T, et al. Health workers’ knowledge of and attitudes towards computer applications in rural African health facilities. Glob Health Action. 2014;7(1):24534, doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.24534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saronga HP, Duysburgh E, Massawe S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of an electronic clinical decision support system for improving quality of antenatal and childbirth care in rural Tanzania: an intervention study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(537):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2457-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abejirinde IOO, Douwes R, Bardají A, et al. Pregnant women’s experiences with an integrated diagnostic and decision support device for antenatal care in Ghana. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(209):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-1853-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nigussie ZY, Zemicheal NF, Tiruneh GT, et al. Using mHealth to improve timeliness and quality of maternal and newborn health in the primary health care system in Ethiopia. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2021;9(3):668–681. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-20-00685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strayer SM, Semler MW, Kington ML, et al. Patient attitudes toward physician use of tablet computers in the exam room. Fam Med; 42(9):643–647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Al-Busaidi ZQ. Qualitative research and its uses in health care. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2008;8(1):11–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith JA. Reflecting on the development of interpretative phenomenological analysis and its contribution to qualitative research in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2004;1(1):39–54. doi: 10.1191/1478088704qp004oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pietkiewicz I, Smith JA.. A practical guide to using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis in qualitative research psychology. Czas Psychol Psychol J. 2014;20(1):7–14. doi: 10.14691/cppj.20.1.7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Green J, Thorogood N.. Qualitative methods for health research. 2nd ed. SAGE; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shoo RS, Mboera LEG, Ndeki S, et al. Stagnating maternal mortality in Tanzania: what went wrong and what can be done. Tanzan J Health Res. 2017;19(2):1–12. doi: 10.4314/thrb.v19i2.6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bartholomew Eldredge LK, Markham CM, Ruiter RAC, et al. Planning Health Promotion Programs an intervention mapping approach. 4th ed. Jossey-Bass; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Van Pelt S, Massar K, Van Der Eem L, et al. “If you don’t have enough equipment, you’re not going to provide quality services”: healthcare workers’ perceptions on improving the quality of antenatal care in rural Tanzania. Int J Africa Nurs Sci. 2020;13:100232. doi: 10.1016/j.ijans.2020.100232 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Solnes Miltenburg A, Van Der Eem L, Nyanza EC, et al. Antenatal care and opportunities for quality improvement of service provision in resource limited settings: a mixed methods study. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0188279. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.The United Republic of Tanzania 2022, February 15. Tanzania Health System – Structure & Challenges. Available from: https://unitedrepublicoftanzania.com/government-of-tanzania-and-the-society/health-in-tanzania-clinics-medical-centers-hospitals-system/healthcare-in-tanzania/tanzania-health-system-structure-challenges-healthcare/.

- 53.Braun V, Clarke V.. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kawungezi PC, AkiiBua D, Aleni C, et al. Attendance and utilization of antenatal care (ANC) services: multi-center study in upcountry areas of Uganda. Open J Prev Med. 2015;05(3):132–142. doi: 10.4236/ojpm.2015.53016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mudallal RH, Othman WM, Al Hassan NF.. Nurses’ burnout: the influence of leader empowering behaviors, work conditions, and demographic traits. Inquiry. 2017;54:004695801772494. doi: 10.1177/0046958017724944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bremnes HS, Wiig ÅK, Abeid M, et al. Challenges in day-to-day midwifery practice; a qualitative study from a regional referral hospital in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Glob Health Action. 2018;11(1):1453333. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2018.1453333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grimm P. Social desirability bias: Wiley international encyclopedia of marketing. John Wiley; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mitchell M, Getchell M, Nkaka M, et al. Perceived improvement in integrated management of childhood illness implementation through use of mobile technology: qualitative evidence from a pilot study in Tanzania. J Health Commun. 2012;17(sup1):118–127. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.649105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sondaal SFV, Browne JL, Amoakoh-Coleman M, et al. Assessing the effect of mHealth interventions in improving maternal and neonatal care in Low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. PloS One. 2016;11(5):e0154664. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Watterson JL, Walsh J, Madeka I.. Using mHealth to improve usage of antenatal care, postnatal care, and immunization: a systematic review of the literature. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2015/153402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tamrat T, Kachnowski S.. Special delivery: an analysis of mHealth in maternal and newborn health programs and their outcomes around the world. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(5):1092–1101. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0836-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wells JD, Campbell DE, Valacich JS, et al. The effect of perceived novelty on the adoption of information technology innovations: a risk/reward perspective. Decis Sci. 2010;41(4):813–843. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5915.2010.00292.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]