Dear Editor,

Non-tuberculous (atypical) mycobacteria are acid-mycolic-based bacteria that may cause various diseases of dermatological interest, such as skin and soft tissue infections. Their diagnosis is usually addressed by a thorough anamnesis, and clinical aspect, and confirmed by PCR exams when available.[1]

Here we present a case of an otherwise healthy 45 years old female patient who accessed our service after the appearance of strange and tender neoformations on her left, causing a stingy-painful sensation.

After a careful anamnestic interview, she said she experienced intensive gardening in her country house and installed a new aquarium the previous week.

Her past medical history is silent, and she has not taken drugs in a chronic or discontinuous manner in the last two months.

At physical examination, we appreciated some nodules and bullous formations on her medium finger, carpal end wrist end, and no axillary lymph nodes were appreciated on palpation.

We suspected infection with a sporotrichosis growth and requested a wide emathochimical panel. We executed a soft-tissue biopsy, a cultural sample for anaerobic and aerobic bacteria, fungi and PCR for sporothrix schenckii, mycobacterium, and leishmania complex (the country house of the patient was in an endemic area).

All the exams were negative, but since sporotrichosis infection seemed the more probable (due to timing, clinical history, and solid consistency of the lesions), we administered itraconazole 200 mg/die.[2]

Two weeks later patient condition worsened, and he was admitted to the hospital ward for further testing.

Among the other exams, we performed another PCR on fresh biopsy for mycobacterium complex, blood tests, CT lung scan, and abdomen ultrasound, all negatives.

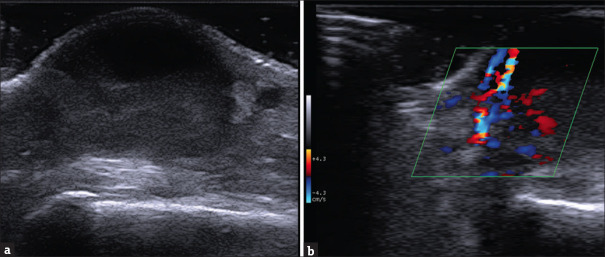

At clinical observation, the cutaneous lesions were mainly of a bullous aspect, with a soft-liquid consistency [Figure 1a and b]. Some lymph node swelling was appreciated on the ipsilateral axilla.

Figure 1.

(a) Lesions distributed on the left hand (b) Side view of the hand and forearm

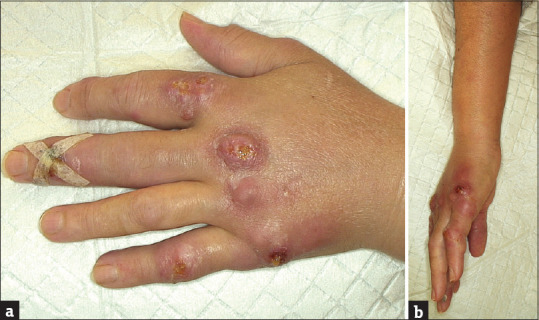

An ultrasound exam of the most representative lesion of the hand highlighted the presence of a well-demarcated dermal formation, with liquid consistency on the upper part and a more echogenic content on the lower portion of the neoformed space. The lesion was enclosed by the epidermis and papillar dermis on the roof and hypoderma and fascial structures on the floor [Figure 2a]. Color-doppler examination showed enhanced vascular flux on the cavities’ basal side, suggesting an extended tissue inflammation [Figure 2b].

Figure 2.

Ultrasound of the nodular formation of the dorsal hand using a high-frequency linear probe [SL3235 appleprobe – Esaote] (a) Deep to the epidermal line, starting from the upper part of the papillar dermis, there we can see the well limited the cutaneous abscess. On the upper part of the lesion a clear anechoic area corresponding to the liquid-exudative part; down it a less well-demarcated area with a non-homogeneous and hypoechoic aspect, with internal echoes, corresponding to colliquative material and debris. On the borders are visible residual collagen bundles of reticular dermis. (b) Colordoppler imaging of the lesion (40% Gain). We note the heterogeneous and bidirectional speed flow with different spot origins of the signal, indicative of strong vascular activity caused by an inflammatory component

Tissue colliquation, among with local inflammation, a sporotrichosis dissemination, and regional lymph node swelling, was highly suggestive of mycobacterial infection.[3] But the now available cultural exams and the new PCR testing requested were negative for every microbiological affection.

Despite the double negative testing, we stopped itraconazole treatment and started rifampicin 10 mg/kg/day plus clarithromycin 15 mg/kg/day.

Lesions almost completely healed three weeks later, confirming the ex juvantibus diagnosis of atypical mycobacterial infection.[1]

Signs and medical history can indicate a nontuberculous mycobacterial infection, especially a history of water exposure, penetrating injury, surgical procedure, negative routine bacterial cultures, and lack of response to non-tubercular specific antibiotics.[4]

Although rarely, PCR can give false-negative results, empirical therapy was necessary in our case, providing an ex-adjuvantibus diagnosis.

Even if ultrasonography is not available in all dermatological divisions, it had an incisive role in this case: it demonstrated the presence of well-delimited nodules, exudate, and necrotic material indicative of an inflammatory process typical of tuberculous infections,[5,6,7] allowing consequently to establish the correct therapy.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ang P, Rattana-Apiromyakij N, Goh CL. Retrospective study of Mycobacterium marinum skin infections. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:343–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pereira MA, Freitas RJ, Nascimento SB, Pantaleão L, Vilar EG. Sporotrichosis: A Clinicopathologic Study of 89 Consecutive Cases, Literature Review, and New Insights About Their Differential Diagnosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2020;42:751–5. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000001617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aubry A, Chosidow O, Caumes E, Robert J, Cambau E. Sixty-three Cases of Mycobacterium marinum Infection: Clinical Features, Treatment, and Antibiotic Susceptibility of Causative Isolates. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1746–52. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.15.1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung J, Ince D, Ford BA, Wanat KA. Cutaneous Infections Due to Nontuberculosis Mycobacterium: Recognition and Management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:867–78. doi: 10.1007/s40257-018-0382-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dos Santos JB, Figueiredo AR, Ferraz CE, de Oliveira MH, da Silva PG, de Medeiros VLS. Cutaneous tuberculosis: Epidemiologic, etiopathogenic and clinical aspects-Part I. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:219–28. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20142334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lindeboom JA, Smets AMJB, Kuijper EJ, van Rijn RR, Prins JM. The sonographic characteristics of nontuberculous mycobacterial cervicofacial lymphadenitis in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2006;36:1063–7. doi: 10.1007/s00247-006-0271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levy J, Barrett DL, Harris N, Jeong JJ, Yang X, Chen SC. High-frequency ultrasound in clinical dermatology: A review. Ultrasound J. 2021;13:24. doi: 10.1186/s13089-021-00222-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]