Background:

Local excision as the main alternative for fertility-sparing surgery (FSS) has been widely used in patients with early-stage cervical cancer to achieve fertility preservation, but its safety and practicability are still questioned. Therefore, The authors evaluated the current application of local excision in early-stage cervical cancer with this population-based study and compared its efficacy with hysterectomy.

Materials and methods:

Women diagnosed with International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage I cervical cancer at childbearing age (18–49 years) recorded in the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database from 2000 to 2017 were included. Overall survival (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS) rates were compared between local excision and hysterectomy.

Results:

A total of 18 519 patients of reproductive age with cervical cancer were included, and 2268 deaths were observed. 17.0% of patients underwent FSS via local excision, and 70.1% underwent hysterectomy. Among patients younger than 39 years, OS and DSS of local excision were comparable to those of hysterectomy, whereas, in patients older than 40 years, OS and DSS of local excision were significantly worse than those of hysterectomy. In addition, OS and DSS of local excision were similar to hysterectomy in patients with stage IA cervical cancer, but OS and DSS were inferior to hysterectomy in patients with stage IB cervical cancer who underwent local excision.

Conclusion:

For patients without fertility requirements, hysterectomy remains the best therapeutic option. However, for patients under 40 years of age diagnosed with stage IA cervical cancer, FSS via local excision is a viable option that can achieve a well-balanced outcome between tumour control and fertility preservation.

Keywords: Early-stage cervical cancer, fertility preservation, hysterectomy, local excision, prognosis

Introduction

Highlights

This study compared local excision with hysterectomy in cervical cancer.

Local excision is an alternative to retain fertility in patients under 40 years of age with stage IA cervical cancer.

Hysterectomy remains the recommended option for patients 40 years of age and older or in stage IB cervical cancer.

For decades, cervical cancer has been recognized as a long-lasting and significant global health issue1,2. As one of the most common malignancies that affect the female genitourinary system, cervical cancer accounted for an estimated 604 000 new cases and 342 000 deaths in 20203. The high incidence is accompanied by an alarming trend toward younger age groups for cervical cancer4. Greater than 25% of women with cervical cancer are under 40 years old, with the proportion of younger women affected by cervical cancer has been on the rise over the past three decades, ranging from 10 to 40%5–7.

Cervical cancer constitutes a significant threat to women’s reproductive health. Apart from the physical and psychological trauma of this condition, the impact on women’s willingness to conceive, the fear of subsequent impaired fertility and both sexual health and quality of life should be taken into account. Although most young cervical cancer patients are diagnosed in the early stages of the disease, the standard curative therapies are hysterectomy and radiotherapy, both of which inevitably affect fertility and impede future childbearing and may also, to some extent, lead to physical and psychological disorders and reduced quality of life8,9. This raises the challenging question of whether it is possible to preserve the uterus without increasing the risk of cancer recurrence, thereby allowing women the opportunity to have children.

For women of reproductive age with early-stage cervical cancer who have a strong desire for fertility, local excision, as the major approach of fertility-sparing surgery (FSS), has been introduced to achieve the preservation of fertility10,11. Local excision includes, but is not limited to cryosurgery, electrocautery, excisional biopsy, laser ablation or thermal ablation https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/manuals/2021/AppendixC/Surgery_Codes_Cervix_2022 12. The safety and impact on fertility of local excision have been somewhat validated in extensive follow-ups at several medical institutions. A single-centre study conducted in Germany reported favourable fertility and oncologic outcomes among 16 patients who underwent local excision for early-stage cervical cancer during the 8-year follow-up period, with nine pregnancies and mostly spontaneous conceptions, and no recurrence of cervical cancer within the investigated time range13. Similarly, a study involving 91 Czech women showed that in patients with cervical cancer with a maximum diameter of less than 2 cm and infiltration of less than half of the interstitial cervical space, the recurrence rate was an acceptable 5.0% with no mortality in patients who underwent local excision over 20 years14. Despite the findings of these meta-analyses and case-control studies, a lack of large studies comparing local excision and hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer persists. This study was performed to investigate the current applications of local excision for early-stage cervical cancer, and to explore whether FSS via local excision could produce an equivalent, or even superior prognosis when compared with hysterectomy.

Material and methods

Data sources and study population

This retrospective population study used data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program. The SEER database is one of the largest population-based cancer registries in the United States, with a substantial collection of real-world cancer data covering nearly 28% of the US population to present current demographics, incidence, survival and cancer treatment. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Cohort Studies in Surgery (STROCSS) reporting guidelines15, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A381.

Women who were diagnosed with first primary cervical cancer [International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, third edition (ICD-O-3) codes: C53.0–C53.9] from 2000 to 2017 recorded in the SEER database were included. Patients diagnosed solely by autopsy or death certificates were excluded, as were those without a microscopic confirmation of the cancer diagnosis. We further excluded patients under 18 years of age and those without complete follow-up information, including follow-up time and age at diagnosis. In addition, we excluded patients for whom the type of surgical intervention was unknown or those treated with local tumour destruction to accurately assess the effect of surgical intervention (Fig. 1). We included 18 519 cases of early-stage cervical cancer at 18–49 years old. Patients aged 50 years and older were also included for comparison (Figure S1, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A382).

Figure 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for patients included in this study. FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

Definition of variables

All patients were on follow-up from the time of the first initial diagnosis of cervical cancer until they died, withdrew from the study alive, or at the end of the study (31 December 2017). For the patients included in this study, we assessed the following variables: age at diagnosis, sex, race, Hispanic origin, year of diagnosis, urban/rural residency at diagnosis, median household income, The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage, surgical procedure, histological types, duration of follow-up and the vital status at the end of the follow-up. For cervical cancer, the T value, N value and M value of the stage were based on American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) third stage codes for patients diagnosed between 2000 and 2003, AJCC sixth stage codes for patients diagnosed between 2004 and 2009, AJCC seventh stage codes for patients diagnosed between 2010 and 2015 and SEER combined stage for patients diagnosed in 2016 and 201716,17 Since the SEER database documents survival in months, and 1 month is the shortest interval of time available for analysis, survival shorter than one month was recorded as 0 months in the SEER database. Age at cancer diagnosis was categorized as 18–24 years, 25–29 years, 30–34 years, 35–39 years, 40–44 years and 45–49 years. Two surgical procedures for cervical cancer were compared: local excision and hysterectomy. The procedure codes for local excision are 20–29 and encompass, but are not restricted to, cryosurgery, electrocautery, excisional biopsy, laser ablation or thermal ablation and combinations thereof. The surgical code for hysterectomy is 30–62. Regardless of whether the fallopian tubes or ovaries are removed, as long as the uterus is removed it is incorporated as a hysterectomy. This includes total hysterectomy, radical or extended hysterectomy, etc. We further assessed urban/rural residency at diagnosis and the patient’s median household income to be reflective of the patient’s socioeconomic circumstance. These variables were based on the assessment of a county’s demographic and socioeconomic conditions, for the most part, a direct evaluation of the properties of the target population in the survey sample data.

Statistical analysis

We characterized stage I cervical patients and compared them according to the type of surgical procedures used. Surgical operation trends were assessed according to age and year of diagnosis. The overall survival (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS) were calculated by the Kaplan–Meier method. The OS rate was determined as the percentage of survivors (all causes of death) after follow-up. The DSS rate was measured as the percentage of patients who did not die from cervical cancer (rather than other causes) within the defined time. Cox regression models were employed to evaluate whether there were any significant differences in survival outcomes between the two different treatments. Multivariate Cox analyses were designed to account for patients’ baseline characteristics, tumour-related features and socioeconomic factors. All analyses were performed using SEER*Stat software version 8.3.8 and R 3.6.3. All statistical tests were two-sided, and values with P less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 2268 fatalities occurred among 18 519 patients of reproductive age with stage I cervical cancer, with a median follow-up of 6.5 years (range: 0–17.9 years). The predominant age of patients was 40–44 years (24.9%), followed by 35–39 years (23.9%) and 45–49 years (19.9%). Patients were primarily white (79%), non-Hispanic (74.4%) and resided in urban areas (89.8%), with a median household income (72.3%). Squamous cell carcinomas made up the majority of the tumours (61.5%). Of stage I cervical cancer patients, 87.1% underwent surgery as their first course of treatment, with 17.0% undergoing FSS through local excision and 70.1% undergoing hysterectomy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients diagnosed with FIGO stage I cervical cancer

| Characteristics | No. patients, n (%) | No. deaths, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 18 519 (100) | 2268 (100) |

| Age | ||

| 18–24 years | 396 (2.2) | 41 (1.8) |

| 25–29 years | 1808 (9.8) | 172 (7.6) |

| 30–34 years | 3585 (19.4) | 350 (15.4) |

| 35–39 years | 4420 (23.9) | 465 (20.5) |

| 40–44 years | 4616 (24.9) | 634 (28) |

| 45–49 years | 3694 (19.9) | 606 (26.7) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 18 519 (100) | 2268 (100) |

| Race | ||

| White | 14 623 (79) | 1650 (72.8) |

| Black | 1981 (10.7) | 417 (18.4) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 192 (1) | 25 (1.1) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1477 (8) | 173 (7.6) |

| Unknown | 246 (1.3) | 3 (0.1) |

| Hispanic origin | ||

| Non-Hispanic | 13 776 (74.4) | 1773 (78.2) |

| Hispanic | 4743 (25.6) | 495 (21.8) |

| Year of diagnosis | ||

| 2004–2009 | 10 129 (54.7) | 1664 (73.4) |

| 2010–2017 | 8390 (45.3) | 604 (26.6) |

| Rural/urban status | ||

| Urban | 16 627 (89.8) | 1971 (86.9) |

| Rural | 1851 (10) | 295 (13) |

| Unknown | 41 (0.2) | 2 (0.1) |

| Median household incomea | ||

| High | 4866 (26.3) | 488 (21.5) |

| Median | 13 382 (72.3) | 1736 (76.5) |

| Low | 268 (1.4) | 44 (1.9) |

| Unknown | 3 (0) | 0 |

| TNM stage | ||

| T1 | 18 519 (100) | 2268 (100) |

| Surgery | ||

| Local excision | 3149 (17) | 263 (11.6) |

| Hysterectomy | 12 984 (70.1) | 1216 (53.6) |

| None | 2386 (12.9) | 789 (34.8) |

| Histology | ||

| Adenocarcinomas | 5276 (28.5) | 431 (19) |

| Squamous cell carcinomas | 11 387 (61.5) | 1501 (66.2) |

| Other | 1856 (10) | 336 (14.8) |

FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

Low income referred to those with a median household income of less than $35 000. Median income referred to those with a median household income ranged from $35 000 to $75 000. High income referred to those with a median household income of more than $75 000.

Prevalence of surgical procedures by age at cancer diagnosis

The vast majority of patients with early-stage cervical cancer were surgically treated. Specifically, for stage I patients, there was a consistent increase in the number of patients who underwent hysterectomy as an initial treatment, from ages 18–49. The proportion of stage I patients undergoing FSS via local excision was in excess of half at the age of 18–19 years, and this proportion then decreased sharply with increasing age, fluctuating at less than 10% for those aged 45–49 years (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Rates of patients aged 18–49 years receiving different types of surgical interventions.

Survival analysis of stage I patients by surgical intervention

The OS and DSS in those who underwent FSS via local excision were significantly better in patients who underwent surgery compared with those who did not receive surgery (5-year OS: 92.0% vs. 66.2%, P=0.7; 5-year DSS: 93.4% vs. 69.4%, P=0.4), but were similar as those undergoing hysterectomy (5-year OS: 92.0%; 5-year DSS: 93.3%) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Outcomes of patients aged 18–49 years with FIGO stage I cervical cancer who underwent different types of surgical interventions. (A) Overall survival (OS) of patients with stage I cervical cancer by surgical interventions. (B) Disease-specific survival (DSS) of patients with stage I cervical cancer by surgical interventions. FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

To obviate the influence of baseline patient characteristics, tumour characteristics and socioeconomic factors, OS and DSS analyses were further conducted with a Cox regression model adjusted by age at diagnosis, race, year of diagnosis, Hispanic origin, median household income, urban/rural residency at diagnosis, histology and surgical procedure. In multivariable Cox analyses, both OS (hazard ratio: 1.08; 95% CI: 0.94–1.24; P=0.268) and DSS (hazard ratio: 1.00; 95% CI: 0.86–1.184; P=1) for local excision were not substantially different from hysterectomy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariable Cox analysis of the overall survival and disease-specific survival of reproductive-age women (18–49 years) diagnosed with FIGO stage I cervical cancer

| Overall survival | Disease-specific survival | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P |

| All patients | — | — | — | — |

| Age at diagnosis | ||||

| 18–24 years | Reference | Reference | ||

| 25–29 years | 1.07 (0.76–1.51) | 0.7 | 1.07 (0.74–1.55) | 0.70 |

| 30–34 years | 1.08 (0.78–1.50) | 0.63 | 1.05 (0.74–1.49) | 0.80 |

| 35–39 years | 1.19 (0.86–1.64) | 0.29 | 1.05 (0.74–1.48) | 0.80 |

| 40–44 years | 1.48 (1.07–2.03) | 0.016 | 1.28 (0.90–1.81) | 0.17 |

| 45–49 years | 1.78 (1.29–2.45) | <0.001 | 1.45 (1.02–2.05) | 0.04 |

| Race | ||||

| White | Reference | Reference | ||

| Black | 1.44 (1.29–1.62) | <0.001 | 1.54 (1.35–1.75) | <0.001 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 1.15 (0.98–1.35) | 0.087 | 1.27 (1.06–1.52) | 0.009 |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 1.27 (0.84–1.92) | 0.25 | 0.96 (0.55–1.65) | 0.87 |

| Unknown | 0.11 (0.04–0.35) | <0.001 | NA | 0.97 |

| Hispanic origin | ||||

| Non-Hispanic | Reference | Reference | ||

| Hispanic | 0.98 (0.88–1.09) | 0.65 | 1.02 (0.9–1.15) | 0.77 |

| Year of diagnosis | ||||

| 2004–2009 | Reference | Reference | ||

| 2010–2017 | 0.85 (0.77–0.94) | 0.001 | 0.85 (0.76–0.94) | 0.002 |

| Rural/urban status | ||||

| Rural | Reference | Reference | ||

| Urban | 0.86 (0.75–0.99) | 0.03 | 0.93 (0.79–1.09) | 0.4 |

| Unknown | 0.27 (0.06–1.14) | 0.07 | 0.42 (0.09–1.89) | 0.3 |

| Median household income | ||||

| Low | 1.50 (1.07–2.09) | 0.018 | 1.43 (0.97–2.11) | 0.073 |

| Median | 1.21 (1.09–1.35) | <0.001 | 1.17 (1.04–1.31) | 0.01 |

| High | Reference | Reference | ||

| Unknown | NA | 0.98 | NA | 1.0 |

| Histology | ||||

| Squamous cell carcinomas | 1.32 (1.18–1.47) | <0.001 | 1.22 (1.08–1.38) | 0.002 |

| Adenocarcinomas | Reference | Reference | ||

| Other | 2.01 (1.74–2.32) | 0 | 2.12 (1.81–2.48) | 0 |

| Surgery | ||||

| Local excision | 1.08 (0.94–1.24) | 0.27 | 1.00 (0.86–1.18) | 0.97 |

| Hysterectomy | Reference | Reference | ||

| None | 4.26 (3.89–4.67) | 0 | 4.76 (4.29–5.27) | 0 |

FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; HR, hazard ratios; NA, not applicable.

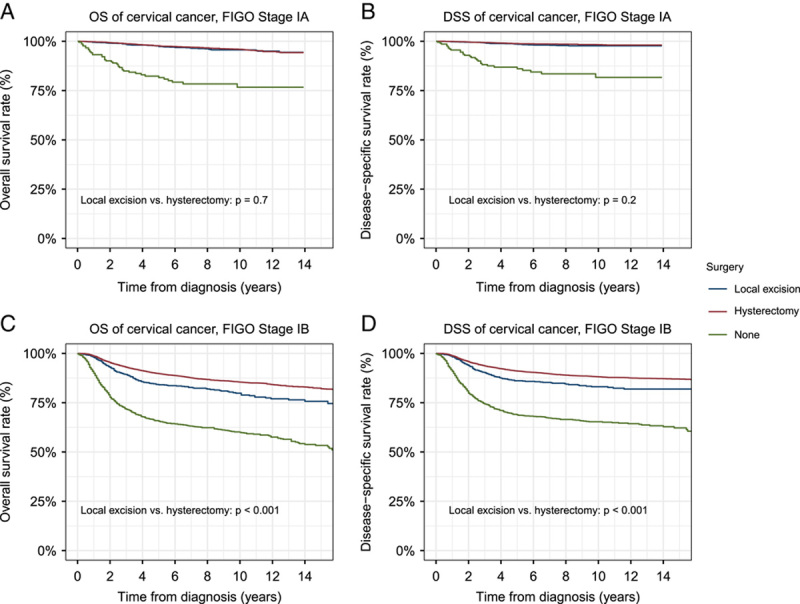

The OS and DSS of local excision were similar to that of hysterectomy for stage IA cervical cancer (OS: P=0.7; DSS: P=0.2), but the OS and DSS of local excision were worse than hysterectomy for stage IB cervical cancer (OS: P<0.001; DSS: P<0.001) (Fig. 4). The HRs of local excision were stable from 18 to 34 years of age but increased dramatically from 39 years of age. The therapeutic effects of local excision decreased notably by age and were significantly worse than hysterectomy in patients older than 40 years (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

Outcomes of surgical interventions in patients with different stages of cervical cancer. (A) Overall survival (OS) of patients with stage IA cervical cancer. (B) Disease-specific survival (DSS) of patients with stage IA cervical cancer. (C) OS of patients with stage IB cervical cancer. (D) DSS of patients with stage IB cervical cancer. FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

Figure 5.

Multivariate Cox analysis of overall survival (OS) and disease-specific survival (DSS) in patients with stage I cervical cancer. (A) Hazard ratios (HRs) for unadjusted OS in patients with stage I cervical cancer undergoing local excision in comparison with hysterectomy by cancer stage; (B) HRs for unadjusted DSS in patients with stage I cervical cancer undergoing local excision in comparison with hysterectomy by cancer stage. (C) HRs for adjusted OS in patients with stage I cervical cancer undergoing local excision in comparison with hysterectomy by cancer stage; (D) HRs for adjusted DSS in patients with stage I cervical cancer undergoing local excision in comparison with hysterectomy by cancer stage.

Survival analysis of patients with stage I cervical cancer by age at cancer diagnosis

To avoid the effects of age on survival analyses, we further investigated the long-term prognosis after local excision (Figs. 6 – 7). We found that the OS and DSS of local excision were no worse than those of hysterectomy in patients younger than 39 years, and the prognosis was even better for patients younger than 34 years (5-year OS: 18–24 years: 94.0% vs. 88.8%, P=0.07; 25–29 years: 96.0% vs. 90.5%, P<0.001; 30–34 years: 96.4% vs. 91.3%, P<0.001; 35–39 years: 93.4% vs. 94.0%, P=1; 5-year DSS: 18–24 years: 94.6% vs. 90.7%, P=0.1; 25–29 years: 96.4% vs. 91.7%, P<0.001; 30–34 years: 97.0% vs. 91.9%, P<0.001; 35–39 years: 94.2% vs. 94.8%, P=0.6). For patients aged 40 years, OS and DSS were markedly worse for local excision than hysterectomy (5-year OS: 40–44 years: 85.9% vs. 91.6%, P<0.001; 45–49 years: 78.9% vs. 91.7%, P<0.001; 5-year DSS: 40–44 years: 89.5% vs. 93.4%, P<0.001; 45–49 years: 82.5% vs. 93.3%, P<0.001). The graphical representation in Fig. 8 depicted a superior survival rate associated with local excision compared to hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer patients younger than 39 years of age, in terms of both 5-year OS and DSS. Furthermore, Figures S2, Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A383 and S3, Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A384, respectively, displayed the results of Cox analysis of the outcomes of two surgical treatment options, local excision and hysterectomy, for patients with stage IA and IB cervical cancer.

Figure 6.

Surgical intervention outcomes in patients with FIGO stage I cervical cancer in different age groups. (A) Overall survival (OS) in patients aged 18–24 years with stage I cervical cancer. (B) OS in patients aged 25–29 years with stage I cervical cancer. (C) OS in patients aged 30–34 years with stage I cervical cancer. (D) OS in patients aged 35–39 years with stage I cervical cancer. (E) OS in patients aged 40–44 years with stage I cervical cancer. (F) OS in patients aged 45–49 years with stage I cervical cancer. FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

Figure 7.

Surgical intervention outcomes in patients with FIGO stage I cervical cancer in different age groups. (A) Disease-specific survival (DSS) in patients aged 18–24 years with stage I cervical cancer. (B) DSS in patients aged 25–29 years with stage I cervical cancer. (C) DSS in patients aged 30–34 years with stage I cervical cancer. (D) DSS in patients aged 35–39 years with stage I cervical cancer. (E) DSS in patients aged 40–44 years with stage I cervical cancer. (F) DSS in patients aged 45–49 years with stage I cervical cancer. FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

Figure 8.

The 5-year survival rate of patients aged 18–49 years with FIGO stage I cervical cancer who underwent surgical intervention. (A) Five-year overall survival (OS) of patients with cervical cancer undergoing local excision compared with hysterectomy; (B) Five-year disease-specific survival (DSS) of patients with cervical cancer undergoing local excision compared with hysterectomy. FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

Analysis of the causes of death in patients with stage I cervical cancer with different surgical approaches

The study investigated the cumulative mortality rate of various causes of death in patients with FIGO stage I cervical cancer who underwent surgical intervention. As shown in Figure 9, patients who underwent FSS via local excision had higher rates of death from infectious diseases than those who underwent hysterectomy. However, patients who underwent hysterectomy exhibited a higher cumulative incidence of deaths from gastrointestinal diseases during the early follow-up and from cancer-related deaths later in follow-up, although the differences did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 9.

Cumulative mortality rate (CMR) in patients with FIGO stage I cervical cancer who underwent surgical intervention. (A) CMR of patients with stage I cervical cancer receiving local excision and hysterectomy who died from cancer-related diseases; (B) CMR of patients with stage I cervical cancer receiving local excision and hysterectomy who died from infectious diseases; (C) CMR of patients with stage I cervical cancer receiving local excision and hysterectomy who died from cardiovascular diseases; (D) CMR of patients with stage I cervical cancer receiving local excision and hysterectomy who died from respiratory diseases; (E) CMR of patients with stage I cervical cancer receiving local excision and hysterectomy who died from gastrointestinal diseases; (F) CMR of patients with stage I cervical cancer receiving local excision and hysterectomy who died from renal diseases; (G) CMR of patients with stage I cervical cancer receiving local excision and hysterectomy who died from external injuries (H) CMR of patients with stage I cervical cancer receiving local excision and hysterectomy who died from other causes of death. FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

Discussion

From a retrospective of more than 18 000 patients of reproductive age with early-stage cervical cancer, we compared the prevalence and long-term outcomes of local excision and hysterectomy for stage I cervical cancer. Our findings indicated that the majority of reproductive-age women with stage I cervical cancer received hysterectomy as initial treatment, while only 17.0% were treated with FSS via local excision. This phenomenon was also verified in another SEER study containing 6359 cases, where younger age was an independent determinant of the choice of local excision in patients with early-stage cervical cancer18.

Despite the low application rate, FSS via local excision has shown a similar prognosis as the commonly used hysterectomy in women aged 18–39 with stage I cervical cancer, indicating that it has the capability to achieve high-quality tumour clearance while conserving fertility. In the context of a parallel increase in the number of women at the age of first marriage, and the growing number of women who are choosing to delay childbearing or remain unmarried for a variety of reasons, fertility preservation will be an imperative element in enhancing the quality of life and social stability of women of reproductive age. Local excision offers a viable alternative for patients and families to make informed decisions about cancer treatment based on therapeutic benefits, social situations, personal beliefs and preferences19,20. Besides, due to the concerns of incomplete resection and tumour residual by local excision, careful preoperative clinical and histologic assessments of the patient, involving preoperative pelvic MRI, contrast computed axial tomography, and PET, are recommended prior to this approach to properly evaluate for parametrial and possible lymphadenopathy. Moreover, special cautions should be taken when employing this approach, including active routine surveillance and even adjuvant radiochemotherapy, to ensure effective treatment outcomes and reduce the risk of cancer recurrence21,22.

Meanwhile, we found that the therapeutic effects of local excision remain unsatisfactory for patients aged 40 years and older. Advancing age can have a considerable bearing on medical decision-making in cancer patients23. Although a study from Taiwan involving 156 patients with cervical cancer showed no significant association between local excision and women’s age, as well as clinical elements such as length of hospitalization, in-hospital mortality and in-hospital complications, the absence of critical information such as cancer stage and pathology reports in the cases could have profound impacts on their results. Additionally, the limited amount of outcome events of readmission, in-hospital complications, etc and unadjusted results in their analyses of related outcomes stratified by age rendered their conclusions less reliable24. In contrast, an epidemiological and clinical analysis from Japan backed up our results. They confirmed that cervical cancer cases under 39 years of age will have a superior prognosis in both localized and advanced lesions, regardless of histological type25.

Considering that stage IB cervical cancer typically features a more pronounced microscopic lesion than stage IA, we hypothesized that the prognosis of local excision may vary depending on the precise stage classification according to FIGO26. In our study, we observed a similar prognosis for local excision and hysterectomy in stage IA, whereas local excision in stage IB was much less therapeutic than hysterectomy. A previous SEER study showed that hysterectomy did not confer a better prognosis than local excision for patients with stage IA cervical cancer, regardless of whether the type was squamous or more invasive adenocarcinoma. This demonstrates that for patients with early-stage cervical cancer with prospective fertility plans, a more conservative local excision option is appropriate, and this is independent of the cell type27. This can minimize the damage patients suffer during surgery, improve their quality of life and can reduce healthcare costs. It is worth noting, however, that a considerably more cautious attitude should be held toward patients with stage IB cervical cancer. Although research utilizing the National Cancer Database (NCDB) database showed similar survival rates even for stage IB patients of reproductive age (hysterectomy 92.1%, 95% CI 88.2–94.8%, vs. local excision 93.6%, 95% CI 88.0–96.6%, P=0.44), it is necessary to take into account that their conclusive findings are on the basis of ~30% of the patient cohort being classified as stage IB NOS. Therefore, it is difficult to draw conclusions that are applicable to the IB1 population28. Morice and colleagues also concluded, after reviewing studies on fertility-preserving surgery published from 1987 to 2016, that for patients with stage IB2 or IIA1, fertility-sparing surgery is not recommended21.

We acknowledge several limitations of our study. Firstly, considering its descriptive and retrospective study design, we were unable to prospectively appraise the effect of surgical interventions on early cervical cancer patients or derive causal inferences. Second, due to the limited data included in the SEER database, we could not perform a comprehensive risk adjustment. Information on patients’ physical status, comorbidities, the extent of local excision, surgical route (abdominal, vaginal or minimally invasive) and presence of lymphatic space invasion in the tumour were not captured in the database, but all of these factors are pertinent to the prognosis. Third, we lacked data on postoperative fertility outcomes. Since miscarriage, preterm delivery and stillbirth are all emotionally distressing situations, fertility and obstetric outcomes should be given additional consideration along with oncologic outcomes to determine the most appropriate individual treatment modality. Nonetheless, our study benefits from the inclusion of a large number of patients and represents one of the largest comparisons between local excision and hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer, which could provide valuable insights into the current clinical practice.

Conclusions

The selection of surgical intervention for patients with early-stage cervical cancer should be based on the experience of the medical team and discussions with the patient or family and, more importantly, on objective tumour statistics as well as a comprehensive assessment of prognosis. This study suggests that hysterectomy remains the best treatment for patients without fertility requirements. For patients under 40 years of age with stage IA cervical cancer, FSS via local excision is a viable alternative. Local excision can achieve a good balance between tumour control and preservation of fertility and can yield therapeutic results comparable to hysterectomy in women of childbearing age. However, additional prospective studies are needed to validate the efficacy, prognosis and reproductive outcomes of local excision in these patients, in an effort to balance the best chance of cure with the most desirable fertility outcomes.

Ethical approval

The data from the SEER database are publicly available. Thus, the present study was exempted from the approval of local ethics committees.

Source of funding

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81873824, 82001514, 82101703).

Author contribution

Y.C.: formal analysis and wrote the original manuscript. Y.Z.: formal analysis and collected and analyzed the data. Y.W.: collected and analyzed the data. J.D. and M.W.: formal analysis. X.Z.: collected the data. T.W.: provided design improvement. W.T.: revise the manuscript. S.Y.: revise the manuscript. J.Z.: provided design improvement. S.Z.: provided design improvement. C.Z.: project administration, provided design improvement, administrative and material support and supervised the study. S.W.: Formal analysis, designed the study, interpreted the data, revise the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Research registration unique identifying number (UIN)

Name of the registry: Research Registry.

Unique Identifying number or registration ID: researchregistry8549.

Hyperlink to your specific registration (must be publicly accessible and will be checked): https://www.researchregistry.com/browse-the-registry#home/registrationdetails/63995741e87bed0026d97156/.

Guarantor

Shixuan Wang had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Data availability statement

All data used in this study can be freely accessed from the SEER programme (https://seer.cancer.gov/).

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Y.C., Y.Z. and Y.W. contributed equally.

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website, www.journal-surgery.net.

Published online 19 April 2023

Contributor Information

Ying Chen, Email: chenying1824@163.com.

Yongqiang Zheng, Email: zhengyq@sysucc.org.cn.

Yaling Wu, Email: wyl76212@163.com.

Jun Dai, Email: dj_hust1987@sina.com.

Xiaoran Zhu, Email: kara232009@hotmail.com.

Tong Wu, Email: tongwu66@tjh.tjmu.edu.cn.

Weicheng Tang, Email: 972028628@qq.com.

Shuhao Yang, Email: 1500592337@qq.com.

Jinjin Zhang, Email: jinjinzhang@tjh.tjmu.edu.cn.

Su Zhou, Email: suzhou@tjh.tjmu.edu.cn.

Meng Wu, Email: mengwu@tjh.tjmu.edu.cn.

Chun Zhang, Email: 18008633845@163.com.

Shixuan Wang, Email: shixuanwang@tjh.tjmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1. Isla-Ortiz D, Palomares-Castillo E, Mille-Loera JE, et al. Cervical cancer in young women: do they have a worse prognosis? A retrospective cohort analysis in a population of Mexico. Oncologist 2020;25:e1363–e71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arbyn M, Castellsagué X, de Sanjosé S, et al. Worldwide burden of cervical cancer in 2008. Ann Oncol 2011;22:2675–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021;71:209–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization. IAfRoCI. Global Cancer Observatory (GCO); Accessed 17 November 2020. https://gco.iarc.fr [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rob L, Skapa P, Robova H. Fertility-sparing surgery in patients with cervical cancer. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:192–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Watson M, Saraiya M, Benard V, et al. Burden of cervical cancer in the United States, 1998-2003. Cancer 2008;113(10 suppl):2855–2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Song B, Ding C, Chen W, et al. Incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in China, 2013. Chin J Cancer Res 2017;29:471–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nitecki R, Woodard T, Rauh-Hain JA. Fertility-sparing treatment for early-stage cervical, ovarian, and endometrial malignancies. Obstet Gynecol 2020;136:1157–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sonoda Y, Abu-Rustum NR, Gemignani ML, et al. A fertility-sparing alternative to radical hysterectomy: how many patients may be eligible? Gynecol Oncol 2004;95:534–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tomao F, Corrado G, Peccatori FA, et al. Fertility-sparing options in young women with cervical cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2016;17:5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Somigliana E, Mangili G, Martinelli F, et al. Fertility preservation in women with cervical cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2020;154:103092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kyrgiou M, Bowden SJ, Athanasiou A, et al. Morbidity after local excision of the transformation zone for cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia and early cervical cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2021;75:10–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tsaousidis C, Kraemer B, Kommoss S, et al. Large conization-retrospective monocentric results for fertility preservation in young women with early stage cervical cancer. Reprod Sci 2022;29:791–799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hruda M, Robova H, Rob L, et al. Twenty years of experience with less radical fertility-sparing surgery in early-stage cervical cancer: oncological outcomes. Gynecol Oncol 2021;163:100–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Agha R, Abdall-Razak A, Crossley E, et al. STROCSS 2019 Guideline: Strengthening the reporting of cohort studies in surgery. Int J Surg 2019;72:156–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. The SEER program, SEER combined/AJCC cancer staging, Accessed 1 April 2020. https://seer.cancer.gov/seerstat/variables/seer/ajcc-stage/.

- 17. Song X, Han Y, Shao Y, et al. Assessment of local treatment modalities for FIGO stage IB-IIB cervical cancer: a propensity-score matched analysis based on SEER database. Sci Rep 2017;7:3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Machida H, Mandelbaum RS, Mikami M, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of reproductive-aged women with early-stage cervical cancer: trachelectomy vs hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;219:461 e1–e18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Machida H, Blake EA, Eckhardt SE, et al. Trends in single women with malignancy of the uterine cervix in United States. J Gynecol Oncol 2018;29:e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Han X, Zang Xiong K, Kramer MR, et al. The affordable care act and cancer stage at diagnosis among young adults. J Natl Cancer Inst 2016;108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bentivegna E, Gouy S, Maulard A, et al. Oncological outcomes after fertility-sparing surgery for cervical cancer: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:e240–e53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nezhat C, Roman RA, Rambhatla A, et al. Reproductive and oncologic outcomes after fertility-sparing surgery for early stage cervical cancer: a systematic review. Fertil Steril 2020;113:685–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pal SK, Hurria A. Impact of age, sex, and comorbidity on cancer therapy and disease progression. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:4086–4093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lai JC, Chen HH, Chu KH, et al. Nationwide trends and in-hospital complications of trachelectomy for surgically resectable cervical cancer in Taiwanese women: a population-based study, 1998-2013. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol 2017;56:449–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yagi A, Ueda Y, Kakuda M, et al. Epidemiologic and clinical analysis of cervical cancer using data from the population-based Osaka Cancer Registry. Cancer Res 2019;79:1252–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Matsuo K, Machida H, Mandelbaum RS, et al. Validation of the 2018 FIGO cervical cancer staging system. Gynecol Oncol 2019;152:87–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bean LM, Ward KK, Plaxe SC, et al. Survival of women with microinvasive adenocarcinoma of the cervix is not improved by radical surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;217:332. e1–e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cui RR, Chen L, Tergas AI, et al. Trends in use and survival associated with fertility-sparing trachelectomy for young women with early-stage cervical cancer. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:1085–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this study can be freely accessed from the SEER programme (https://seer.cancer.gov/).