West Virginia has a proud tradition of military service and WVU Medicine proudly continues that tradition by providing training and research for U.S. Army Special Forces

KEY WORDS: Special operations, medic, military-civilian partnership

BACKGROUND

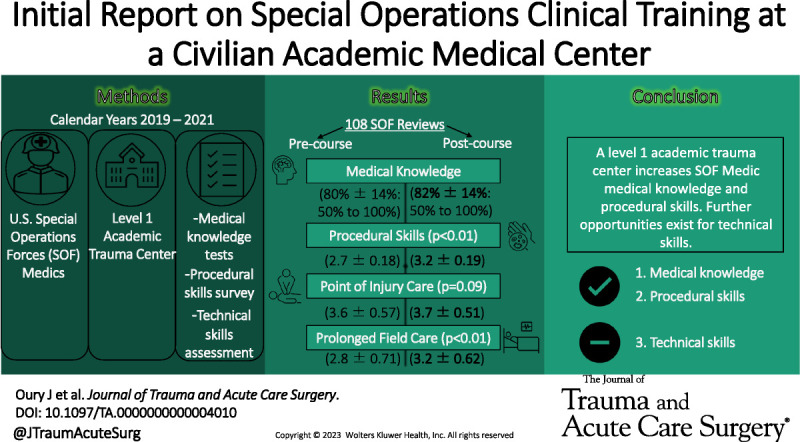

Military-civilian partnerships for combat casualty care skills training have mostly focused on traditional, combat surgical team training. We sought to better understand US Special Forces (SF) Medics' training at West Virginia University in Morgantown, West Virginia, a Level 1 trauma center, via assessments of medical knowledge, clinical skills confidence, and technical performance.

METHODS

Special Forces Medics were evaluated using posttraining medical knowledge tests, procedural skills confidence surveys (using a 5-point Likert scale), and technical skills assessments using fresh perfused cadavers in a simulated combat casualty care environment. Data from these tests, surveys, and assessments were analyzed for 18 consecutive SF medic rotations from the calendar years 2019 through 2021.

RESULTS

A total of 108 SF Medics' tests, surveys, and assessments were reviewed. These SF Medics had an average of 5.3 years of active military service; however, deployed experience was minimal (73% never deployed). Review of knowledge testing demonstrated a slight increase in mean test score between the precourse (80% ± 14%; range, 50–100%) when compared with the postcourse (82% ± 14%; range, 50–100%). Skills confidence scores increased between courses, specifically within the point of injury care (p = 0.09) and prolonged field care (p < 0.001). Technical skills assessments included cricothyroidotomy, chest tube insertion, and tourniquet placement.

CONCLUSION

This study provides preliminary evidence supporting military-civilian partnerships at an academic Level 1 trauma center to provide specialty training to SF Medics as demonstrated by increase in medical knowledge and confidence in procedural skills. Additional opportunities exist for the development technical skills assessments.

LEVEL OF EVIDENCE

Therapeutic/Care Management; Level IV.

Military-civilian partnership is not a new endeavor.1 Numerous civilian academic medical centers are currently participating in trauma and surgical skills training and sustainment. These efforts have largely been focused on traditional combat casualty care teams, such as forward surgical units. All four branches of the US military have elite units that fall under the realm of special or unconventional operations. Special operations “are defined as operations conducted by specially trained, equipped and organized Department of Defense forces against strategic or tactical targets in pursuit of national military, political, economic or psychological objectives. These operations may be conducted during periods of peace or hostilities.”2 Elite units have their own medics or corpsmen (US Navy) that go through extensive civilian and military medical training. These soldiers, sailors, and airmen are combatants who are tasked with learning battlefield medicine such as Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC, “T Tri C”) and Prolonged Field Care (PFC). Student Special Forces Medics (Army Military Occupational Specialty 18D) and Navy Special Amphibious and Reconnaissance Corpsman (SARC) benefit from medical training at civilian institutions during initial and advanced training programs at the Joint Special Operations Medical Training Facility at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. Special Forces Medics have been working with and through civilian health care institutions ever since 1953.3 Our university is one of the few civilian health care institutions in which student Special Forces Medics and SARCs train at during their Special Operation Clinical Training (SOCT) rotation. The course was developed to provide an immersive training environment with emphasis on the procedural skills, medical knowledge, critical care, and critical care nursing necessary for thriving in an unconventional or austere environment.

Tactical Combat Casualty Care is protocols aimed at preventing mortality in the first hours of treatment.4 More specifically, they are a set of evidence-based point of injury trauma care guidelines to be used on the battlefield.5 They were first developed in the mid-90s after Operation Gothic Serpent in Somalia in response to data that the leading cause of preventable death in the Vietnam War was extremity hemorrhage.6,7 In 2001, the Committee on TCCC was founded, and the guidelines were updated with data and lessons learned early from the war in Afghanistan and continue to be updated to this day. These guidelines are now the core principles of caring for injured soldiers on the battlefield. The spectrum of care starts at point of injury with Care Under Fire, progresses to Tactical Field Care, and finally ends with Casualty Evacuation Care.

During the wars of Afghanistan and Iraq, in theater medical infrastructure became highly developed, and training became centered around operating within the resource-rich environment and TCCC. Special Forces Medics identified a departure from unconventional and austere medical skill sets. The isolated environment in which unconventional operations occur required a larger focus on what was to be called PFC.5 Prolonged Field Care is a field of medical care applied beyond doctrinal planning timelines.5 The defining scenario of PFC is taking care of a patient from point of injury to evacuation lasting longer than 72 hours in an austere environment. As such, a PFC Working Group was created to help develop guidelines and training for Special Operations Medics in the austere environments. However, there continues to be a lack of data and analysis on how training at civilian institutions prepares medics for these PFC conditions. The intent of this study was to examine how training at an academic Level 1 trauma center impacts the TCCC/PFC procedural skills and medical knowledge of students in Special Forces Medic and SARC programs.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This was a prospective, single-armed cohort study assessing both objective measures of knowledge and technical skills, and subjective measures of confidence in procedural skills and patient management. All students in SOCT courses at our institution from 2019 to 2021 were included in this study. This study received institutional review board approval. The STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines was used to ensure proper reporting of methods, results, and discussion points (Supplement Digital Content, Supplementary Data 1, http://links.lww.com/TA/D29).8 Throughout the 24-day SOCT course, students received specific trauma and prolonged field care training via traditional didactic lectures (10% of time), procedural skill trainers (10% of time), clinical rounds with faculty (30% of time), and direct patient care (50% of time). These rotations included trauma, general surgery, thoracic surgery, orthopedics and podiatry, ophthalmology, surgical and cardiovascular intensive care, and emergency medicine among others. At the conclusion of the SOCT course, students completed a half-day casualty care exercise (CASEX) for assessment of technical metrics, time to completion of specific trauma care tasks, and prolonged field care procedural skills. This was performed in a realistic casualty care environment using fresh human cadavers in our institution's Fresh Tissue Training Program procedure laboratory. These perfused and ventilated human cadavers create a dynamic, high-fidelity simulated patient care environment.9 The establishment of maximum time standards for technical skills evaluated during the CASEX was based on the expert opinion of the authors in consultation with Joint Special Operations Medical Training Instructors.

Fresh, nonembalmed human cadavers were stored at 4°C and allowed to warm to room temperature (20°C) before training sessions. Regional limb vascular perfusion was achieved via femoral arterial cannulation and the use of a centrifugal perfusion pump (Medtronic BPX-40 BioPump [Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN], Medtronic Bio Medicus Bio Console 550 [Medtronic]). A blood substitute consisting of water and non-toxic red paint was used. Simulated blast, gunshot wounds, and burns were created using moulage or actual tissue manipulation.10

A “low-light” environment is created whereby students operate using headlamps and minimal pass-through lighting from covered windows. Simulated patients or cadavers are placed respectfully around the room, and the students must render care in the location in which they encounter the simulated casualty. Before entering the simulation room, the students are briefed on the casualty scenarios, divided into two-man teams, and given a short amount of time to pack an aid bag with needed medical supplies. They are only allowed to render care for their simulated patient using the supplies they bring in the room, two simple ventilators, and 3 U of simulated whole blood. They are allowed to share supplies and instruments among teams.

As the students enter the room, an instructor meets them at their casualty and provides them with mechanism and time of injury, injuries, symptoms and vital signs, treatment give report (Table 1). The combat casualty scenarios included complex multiple injuries, such as gunshot wounds to the core and extremities, traumatic amputations, blast injuries, traumatic brain injuries, and burns. The instructor remains present to assess the students as they render care to the simulated combat casualty. The exercise is approximately 4 hours and extends from the initial resuscitation through a scaled period of prolonged field care. The extension into prolonged field care is truncated and expedited for real-world time constraints. Assessment includes technical metrics evaluation of performance and time to completion of the following key steps of procedures: loss of airway and cricothyroidotomy, tension pneumothorax with needle decompression and chest tube insertion, extremity hemorrhage with tourniquet placement, and tourniquet conversion and blood resuscitation. Evaluation was the completion of steps as assessed by expert evaluators and proctors. These evaluators consisted of medical students and general surgery residents who were former SF Medics and board-certified surgeons who were members of the trauma faculty. Upon completion of their individual scenarios, there is a large group debrief with opportunities to refresh on skills and procedures.

TABLE 1.

MIST Report Example

| M | Blast and vehicle entrapment |

| I | Burns face, circumferential chest burns, blast lung, and open fracture left tibia with arterial hemorrhage |

| S | Tachypnea, GCS score of 4 |

| T | No interventions at point of injury |

| Vitals | HR, 160 bpm; RR, 40 breaths per minute; BP, 140/80 mm Hg; SpO2, 86% |

MIST report: M, mechanism and time of injury; I, injuries; S, symptoms and vital signs; T, treatment give.

BP, blood pressure; bpm, beats per minute; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; HR, heart rate; RR, respiratory rate.

Students were provided demographic surveys before the training event. Demographic information included years of military service, military branch, rank, number of deployments, and number of combat deployments. A prerotation and postrotation survey and knowledge test was also administered. Survey questions assessed trainee confidence in their ability to perform key procedural skills specific to the management of trauma pretraining and posttraining. Surveys used a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from 0 (no confidence) to 5 (complete confidence). The knowledge test consisted of a multiple-choice examination written and vetted by board-certified surgeons who are members of the trauma faculty.

Demographic data collected are presented as mean ± SD. Confidence scores are presented as mean ± SD Likert score and as median (interquartile range). A paired t test and a Wilcoxon signed-rank test were used to determine the difference between the Likert scores. Analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel (2021) (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA).

RESULTS

A total of 18 SOCT courses were included, with 108 students over the 2-year period. No students were excluded. Students had an average of 5.3 years of active military service (Table 2). Deployed experience was minimal, with 72% having never been deployed and only 22% ever deploying to combat (Table 2). Review of knowledge testing demonstrated a 2% increase in mean test scores between the precourse test (80% ± 14%) when compared with the postcourse test (82% ± 14%). This increase was not significant (p = 0.085).

TABLE 2.

Demographics

| Total | Range | Percent of Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total trainees | 108 | NA | 100% |

| Army | 101 | NA | 93.5% |

| Navy | 7 | NA | 6.5% |

| Total | Range | Percent of Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Junior enlisted | 9 | NA | 8.3% |

| Noncommissioned officer | 99 | NA | 92.7% |

| Mean ± SD, y | Range | Percent of Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Years of service | 5.31 ± 3.82 | 2–16 | NA |

| Deployments, Mean ± SD | Range | Percent of Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No deployments | NA | NA | 72% |

| Deployments | 0.64 ± 1.38 | 0–6 | 28% |

| Combat Deployments | 0.40 ± 0.94 | 0–6 | 22% |

NA, not applicable.

Combat and prolonged casualty care procedural skills confidence scores increased between precourse and postcourse evaluations (2.81 ± 0.71 vs. 3.17 ± 0.63, p < 0.01; Table 3). Confidence scores for focused assessment with sonography in trauma showed a significant increase (2.73 ± 0.87 vs. 3.31 ± 0.67, p < 0.01; Table 3) along with medic confidence in general nursing care (1.96 ± 0.92 vs. 2.96 ± 0.79, p < 0.01; Table 3). With nine Likert score comparisons, the p value for significance of Likert score comparisons was p < 0.056. Table 3 includes median Likert score with interquartile range.

TABLE 3.

Skill Set Confidence Evaluation

| Skill Set | Pre | Post | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall POI care | Mean ± SD | 3.56 ± 0.57 | 3.66 ± 0.51 | 0.086 |

| Median (IQR) | 4 (1.0) | 4 (1.0) | 0.087 | |

| Overall PCC | Mean ± SD | 2.81 ± 0.71 | 3.17 ± 0.63 | <0.001 |

| Median (IQR) | 3 (1.0) | 3 (1.0) | <0.001 | |

| Manage shock | Mean ± SD | 3.52 ± 0.62 | 3.66 ± 0.53 | 0.028 |

| Median (IQR) | 4 (1.0) | 4 (1.0) | 0.029 | |

| Tourniquet | Mean ± SD | 3.94 ± 0.49 | 3.95 ± 0.35 | 0.417 |

| Median (IQR) | 4 (0) | 4 (0) | 0.48 | |

| Airway | Mean ± SD | 3.75 ± 0.49 | 3.88 ± 0.35 | 0.006 |

| Median (IQR) | 4 (0) | 4 (0) | 0.0065 | |

| NT for tension PTX | Mean ± SD | 3.60 ± 0.58 | 3.76 ± 0.49 | 0.009 |

| Median (IQR) | 4 (1.0) | 4 (0) | 0.0097 | |

| Chest tube | Mean ± SD | 3.59 ± 0.64 | 3.59 ± 0.80 | 0.160 |

| Median (IQR) | 3 (1.3) | 4 (1.0) | <0.001 | |

| FAST | Mean ± SD | 2.73 ± 0.87 | 3.31 ± 0.67 | <0.001 |

| Median (IQR) | 3 (1.0) | 3 (1.0) | <0.001 | |

| General nursing care | Mean ± SD | 1.96 ± 0.92 | 2.96 ± 0.79 | <0.001 |

| Median (IQR) | 2 (2.0) | 3 (0) | <0.001 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD Likert score, 0 to 4, or as median (IQR).

FAST, focused assessment with sonography in trauma; IQR, interquartile range; NT, needle thoracostomy; PCC, prolonged causality care; POI, point of injury; PTX, pneumothorax.

Technical skills and time to completion during the evaluated CASEX (Table 4) include time to cricothyrotomy (228 ± 132 seconds), needle decompression (127 ± 102 seconds), chest tube insertion (702 ± 363 seconds), tourniquet placement (149 ± 69 seconds), and administration of whole blood (484 ± 180 seconds). Eighty-four percent of students were able to perform a successful cricothyrotomy; 67%, placement of a chest tube; and 71%, placement of a tourniquet within the expected time standard, as stated in Table 4.

TABLE 4.

Technical Metrics During CASEX: Time to Completion of Critical Tasks

| Average Time, s | SD, s | Maximum Time Standard, s | Percent Meeting Standard | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Airway | Identify loss of airway to skin incision | 149 | 75 | 210 | 79% |

| time to secure airway (cricothyrotomy) | 228 | 132 | 360 | 84% | |

| Breathing | Identify tension PTX to needle decompression | 127 | 102 | 180 | 67% |

| Placement of chest tube | 702 | 363 | 900 | 67% | |

| Circulation | Time to identify hemorrhage and placement of TQ | 149 | 69 | 210 | 71% |

| Time to begin whole blood resuscitation | 484 | 180 | 660 | 94% |

Time is presented in seconds.

PTX, pneumothorax; TQ, tourniquet.

DISCUSSION

Demographic results from our study showed that more Special Forces Medic students are coming to our institution with limited deployments or combat experience. This only further increases the need to have properly tailored programs to instruct and educate them for their operational environments. Furthermore, time and experience in the military in our student cohort are also very minimal (about 5 years of service). Results showed an increase in knowledge from pretests to posttests by 2%, showing a small yet positive trend in the education program to impart medical knowledge. Further evaluation of knowledge gaps identified on these examinations can help guide areas of reinforcement or determine if areas of concentration are not vitally important to the overall mission. Finally, the increase in confidence for overall PFC, including basic ventilator management and troubleshooting; treatment of hyperkalemia and rhabdomyolysis; treatment of other causes of nontraumatic shock; nursing care, such as Foley and intravenous management and wound care; and focused assessment with sonography in trauma examinations were significant, showing a positive trend after completion of our course. Prolonged Field Care skills include basic ventilator management and troubleshooting, treatment of hyperkalemia and rhabdomyolysis, and treatment of other causes of nontraumatic shock. Overall results from our study confirm an increase in knowledge, skills, and confidence. Technical skills assessment demonstrated that the majority of the SF Medics performed critical casualty care procedures correctly and timely. Identification of procedural skills deficiencies can be helpful in developing refresher and retraining courses.

Special Forces Medics are a unique type of health care provider whose skills may not specifically apply to the civilian health care sector. Special Forces Medics are highly trained as practitioners in emergency and primary care medicine, advanced life support techniques, parasitology, and dentistry and have the ability to deliver limited veterinary care.8 They provide care far in advance of conventional military and support and are often the only advanced medical care available for days or hundreds of miles.9 The primary limitation of Special Forces Medics is that they cannot open the thoracic, abdominal, or cranial cavities to control bleeding without the immediate availability of higher-level surgical support.11

Today, there is still controversy on where Special Forces Medics fit in the scope of civilian medicine. They are generally considered to be in between a flight medic/paramedic and a physician assistant. According to the American Academy of Physician Assistants, the first physician assistant class was developed for physician shortage and was consisted of four Navy corpsmen who received extensive military medical training and experience from the Vietnam War.12 Determining the appropriate instruction and curriculum at these civilian health care institutions is important for the success of these medics. Working through and with members of the surgical community at these civilian institutions, Special Forces Medics and SARCs learn the acceptable civilian standards of care within the health care profession. They can take these experiences and attempt to emulate them while deployed and fighting downrange in austere environments. In addition, the results of our study provide evidence that SOCT training in combat casualty and prolonged field care at our civilian academic medical center are effective. Members of the trauma surgery community can refer to our course as a framework for further developing military-civilian partnership for SF Medic training.

Prior studies from the senior authors demonstrate the utility of fresh tissue training in teaching military medics lifesaving procedures such as needle decompression for tension pneumothorax and limb tourniquet application.10,13 The SOCT combat casualty care course at our institution, however, is comprehensive. It provides educational and procedural training with multiple methods of knowledge assessment and technical evaluation to help prepare Special Forces Medics and SARCs for real-world TCCC and PFC scenarios. The program continues to evolve with feedback from students and internal quality improvement in metrics and qualitative data gathering. These tools will guide changes to the curriculum and help us to achieve our goal of preparing Special Forces Medics and SARCs for TCCC and PFC skills.

Certain limitations were acknowledged during the analysis of this study. The sample size of 108 students is relatively small and can skew general analysis. Furthermore, the training was only at our institution and used only our program to measure teaching effectiveness; it did not compare the techniques of the university with other programs, which would be beneficial in the future. Data collection through surveys themselves can be very subjective when using a Likert scale. Standardization can be difficult for these surveys because participants may have different perspectives on the ranking system. Also, pretests and posttests developed for progression of knowledge comprised only 20 questions and might not accurately reflect knowledge. Finally, there was no stratification for experience level and deployments or age, which could also create different data conclusions.

We plan to use the data collected from this study to further enhance the experience and quality of training of these soldiers while training at our university and share this with other institutions of higher learning. Other future research should revolve around the human performance of these Special Operations Medics and how to further optimize care under the most stressful scenarios.

CONCLUSION

Military-civilian health care partnerships provide a mutual training benefit for both organizations. Each organization is dedicated to providing the best health care to the individuals whom they serve. The blending of lessons learned and experienced practices in different settings enhances the quality of care given. Civilian institutions will continue to be an integral part of the training of military medical personnel. Continued exploration of training and curriculum will better serve these military medical professionals.

Supplementary Material

AUTHORSHIP

D.G. and A.W. conceived the study concept and study design. J.O., J.D., and K.A. performed data acquisition, and B.L.R. performed data analysis. All provided critical revision and editing with all authors approving the final manuscript.

The view(s) expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of the Air Force, or the Department of Defense or the US Government.

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text, and links to the digital files are provided in the HTML text of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.jtrauma.com).

Contributor Information

Benjamin L. Reed, Email: benjamin.reed@hsc.wvu.edu.

James Donovan, Email: donovanjm@upmc.edu.

Kamil Abbas, Email: kaa0032@mix.wvu.edu.

Alison Wilson, Email: awilson@hsc.wvu.edu.

Daniel Grabo, Email: daniel.grabo@hsc.wvu.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Knudson MM, Elster EE, Woodson J, Kirk G, Turner P, Hoyt DB. A shared ethos: the military health system strategic partnership with the American College of Surgeons. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222(6):1251–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.SOF Primer. SOF Primer Page . Available at: https://www.soc.mil/USASOCHQ/SOFPrimer.html. Accessed March 8, 2023.

- 3.Dorogi LT. Early Special Forces Medical Training: 1952–1971. J Spec Oper Med. 2007;7(1):73–80. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farr WD. The death of the golden hour and the return of the future guerrilla hospital. Joint Special Operations University Report. 2017;17–10. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keenan S. Deconstructing the definition of prolonged field care. J Spec Oper Med. 2015;15(4):125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maughon JS. An inquiry into the nature of wounds resulting in killed in action in Vietnam. Mil Med. 1970. Jan;135(1):8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butler FK, Jr. Tactical Combat Casualty Care: beginnings. Wilderness Environ Med. 2017;28(2S):S12–S17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Von Elm E Altman DG Egger M Pocock SJ Gøtzsche PC Vandenbroucke JP, STROBE Initiative . The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carey JN, Minneti M, Leland HA, Demetriades D, Talving P. Perfused fresh cadavers: method for application to surgical simulation. Am J Surg. 2015;210(1):179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grabo DJ Jr. Polk T Strumwasser A Inaba K Foran CP Luther C, et al. A novel, perfused-cadaver simulation model for tourniquet training in military medics. J Spec Oper Med. 2018;18(4):97–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.United States Army . FM 3–18: Special Forces Operations. Fort Bragg, NC, May 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.AAPA . History. Published March 8, 2023. Available at: https://www.aapa.org/about/history/. Accessed March 8, 2023.

- 13.Grabo D Inaba K Hammer P Karamanos E Skiada D Martin M, et al. Optimal training for emergency needle thoracostomy placement by prehospital personnel: didactic teaching versus a cadaver-based training program. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77(3 Suppl 2):S109–S113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]