Background:

This study aimed to establish and validate nomograms to predict the probability of recurrence and recurrence-free survival (RFS) in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) after conversion hepatectomy based on hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC).

Methods:

Nomograms were constructed using data from a retrospective study of 214 consecutive patients treated with HAIC-based conversion liver resection between January 2016 and July 2020. Nomograms predicting the probability of tumor recurrence and RFS were established based on predictors selected by multivariate regression analysis. Predictive accuracy and discriminative ability of the nomogram were examined. Bootstrap method was used for internal validation. External validation was performed using cohorts (n=128) from three other centers.

Results:

Recurrence rates in the primary and external validation cohorts were 63.6 and 45.3%, respectively. Nomograms incorporating clinicopathological features of tumor recurrence and RFS were generated. Concordance index (C-index) scores of the nomograms for predicting recurrence probability and RFS were 0.822 (95% CI, 0.703–0.858) and 0.769 (95% CI, 0.731–0.814) in the primary cohort, and 0.802 (95% CI, 0.726–0.878) and 0.777 (95% CI, 0.719–0.835) in the external validation cohort, respectively. Calibration curves indicated good agreement between the nomograms and actual observations. Moreover, the nomograms outperformed the commonly used staging systems. Patients with low risk, stratified by the median nomogram scores had better RFS (low risk vs. high risk, 36.5 vs. 5.2 months, P<0.001). The external validation cohort supported these findings.

Conclusions:

The presented nomograms showed favorable accuracy for predicting recurrence probability and RFS in HCC patients treated with HAIC-based conversion hepatectomy. Identifying risk factors and estimating tumor recurrence may help clinicians in the decision-making process regarding adjuvant therapies for patients with HCC, which eventually achieves better oncological outcomes.

Keywords: conversion, hepatectomy, hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy, hepatocellular carcinoma, nomogram, recurrence

Introduction

Highlights

We have developed the first predictive nomogram for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who underwent hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC)-based conversion hepatectomy.

Our findings may guide clinicians in developing personalized therapeutic strategies for patients undergoing HAIC-based liver resection.

HCC is the sixth most common malignancy and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide1,2. Patients with HCC often lose the opportunity to undergo radical surgery due to an initial diagnosis at an advanced stage3. Factors such as large tumor volume, vascular invasion, and metastasis are regarded as vital impediments as to why patients are ruled out for radical hepatectomy3,4. Nevertheless, investigators indicated that an increase in resection rates should be advocated because surgical resection resulted in a potential survival benefit for patients with intermediate and advanced stages of HCC, albeit accompanied by a high postresection recurrence rate5. Recently, a growing number of studies have been exploring tumor downstaging strategies that enable originally inoperable patients to receive radical resection through various effective therapies, thereby improving their prognosis6–8. However, high postoperative tumor recurrence rate remains a primary obstacle to long-term survival9–11. Thus, it is reasonable and necessary to screen high-risk patients who may benefit from adjuvant therapies to curtail the recurrence rates.

HAIC has been proven to benefit patients with advanced HCC or as adjuvant therapy after surgical resection in Asian countries, such as China, Japan, and South Korea12–15. Nonetheless, no study has been reported to predict HCC recurrence after HAIC-based conversion hepatectomy.

Reliable prognostic information after conversion hepatectomy is crucial for patients with HCC and clinicians because it helps medical practitioners make decisions on adjuvant treatment and follow-up frequency, and can provide helpful information about treatment strategies and outcomes for patients with high risk of tumor recurrence. Currently, targeted therapy, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), and HAIC have contributed significantly to the treatment efficacy in intermediate-stage, advanced-stage, and recurrent HCC16–18. Consequently, a combination of the above treatments preoperatively or postoperatively may improve the prognosis of patients with a high risk of tumor recurrence.

Considering the high risk of recurrence following liver resection, especially in patients undergoing conversion hepatectomy who may already be prone to recurrence before conversion therapy, early detection of recurrence and identification of those patients who may benefit from adjuvant or neoadjuvant treatment are of vital importance19,20. Owing to the lack of a practical and specific predictive approach, a prognostic model that includes recurrence-related factors needs to be established, based on perioperative clinicopathological parameters. This study aimed to retrospectively analyze patients with HCC who underwent HAIC-based conversion surgery in four centers. Prognostic models for postoperative recurrence risk and recurrence-free survival (RFS) probabilities were constructed and validated. Moreover, an easy-to-use nomogram demonstrating individualized and highly accurate risk assessment for the predictive model was established, which could be useful for guiding decision-making in the clinical management of HCC.

Methods

Patients and study design

Data on consecutive patients with HCC who underwent HAIC-based conversion therapy as an initial treatment followed by hepatectomy between 1 January 2016, and 31 July 2020, were included. HCC diagnosis was based on the criteria of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases21.

Patients with insufficient future liver remnant because of large tumor volume or multiple lesions, vascular invasion, Child–Pugh grade A, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status ≤2 at the initial diagnosis, were the eligibility criteria for HAIC treatment. The inclusion criteria for conversion hepatectomy were as follows: (1) patients achieved disease control after conversion therapy; (2) the initial treatment was HAIC-based therapy; (3) R0 tumor resection; (4) Child–Pugh class A or B; and (5) ECOG ≤2 before treatment. The exclusion criteria included: (1) presence of cardiac, pulmonary, or renal insufficiency before HAIC or liver resection; (2) distant tumor metastasis; (3) missing clinicopathological information or no follow-up data; (4) diagnosis or history of other concurrent malignant tumors; and (5) tumor progression during conversion treatment.

A total of 214 consecutive patients from our cancer center were enrolled in the study. Patients who underwent HAIC-based conversion hepatectomy from three other hospitals (total n=128) between 2017 and 2021 were recruited as the external validation cohort using the same inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Clinicopathological information of the patients was collected before the initial HAIC treatment, between the last HAIC treatment and hepatectomy, and 1 month after liver resection. This work has been reported in line with the STROCSS criteria22 (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A292).

Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy and evaluation

HAIC was performed using the modified FOLFOX regimen. The protocol was as follows: oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2, leucovorin 400 mg/m2, fluorouracil bolus 400 mg/m2 on day 1, and fluorouracil infusion 2400 mg/m2 for 46 h. Every 3 weeks was regarded as one treatment cycle12,23. At each center, patients were treated with HAIC using the same protocol and dose.

Tumor response evaluation was conducted in patients who received HAIC after two treatment cycles. Assessment was performed using computed tomography (CT) or MRI. The maximum treatment duration lasted for no more than six cycles. Tumor response was evaluated using the modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (mRECIST)24, including (1) complete response (2) partial response, (3) stable disease, and (4) progressive disease.

Hepatectomy and follow-up

Routine preoperative assessments, such as liver, renal, and coagulation function tests; evaluation of liver cancer-specific tumor markers including alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II (PIVKA-II), carbohydrate antigen 19-9, and carcinoembryonic antigen; abdominal imaging (CT, MRI, and ultrasonography); CT scan of the chest; cardiopulmonary function examinations; and ECOG score, were completed before hepatectomy.

After liver resection, the patients were monitored in the outpatient clinic every 2 months for the first 2 years after the operation and every 3–6 months thereafter. Routine blood tests, tumor marker assessment, liver and coagulation function tests, and abdominal imaging (CT, MRI, or ultrasonography) were performed at each follow-up visit. Diagnostic criteria for tumor recurrence included: (1) the appearance of new lesions with typical radiological features of HCC on two imaging studies, and (2) evidence of new extrahepatic lesions not found before hepatectomy.

The endpoints of this study were tumor recurrence and RFS. RFS was calculated from the date of surgical resection to the date of HCC recurrence or the date of the last follow-up visit.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were reported as numbers (%) and compared using the chi-squared and Kruskal–Wallis tests. Continuous data were expressed as the median with interquartile range and compared using the independent sample t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test. For missing values of baseline variables, multiple imputation analysis was conducted using the fully conditional specification discriminant function for categorical missing data and the fully conditional specification regression for continuous missing data. Survival curves were generated using the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences were analyzed using the log-rank test. Univariate analysis was conducted on training cohort. Factors correlated with tumor recurrence and RFS were included in the multivariate analysis. Multivariable logistic regression and Cox regression analyses were performed to identify the independent prognostic factors for tumor recurrence probability and RFS, respectively. Predictors with significance (P<0.2 in the univariate analysis were subsequently entered into the multivariate regression model. Nomograms predicting the probability of tumor recurrence and RFS were established based on predictors selected by multivariate regression analysis. Bootstrap method with 1000 resamples was used for internal validation of the predictive models and calibration curve generation. The performance of the models, including discrimination and calibration, was assessed using the concordance index (C-index) and a calibration curve plotted using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test. Comparisons of recurrence and survival probabilities between the nomogram-predicted and other commonly used staging systems were performed using Kaplan–Meier curves, and dissimilarities were analyzed using the log-rank test. A 2-sided P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. IBM SPSS Statistics (version 26.0; IBM Corp.) was used for statistical analyses and R software (Version 4.1.1, Regression Modeling Strategies package, R Foundation for Statistical Computing) was used for nomogram development and validation.

Results

Patient characteristics

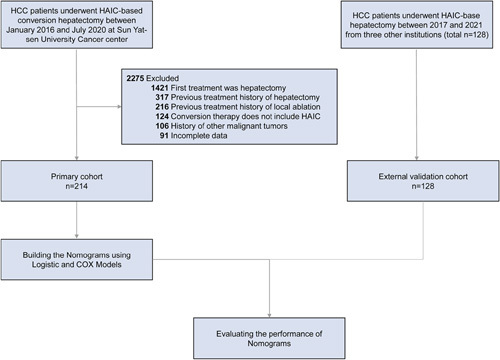

Eight hundred and twenty-nine and 582 unresectable patients in the primary and external validation cohorts were treated with HAIC, respectively. Curative liver resection was conducted for 214 patients (25.8%) in the primary cohort and 128 patients (22.0%) in the external validation cohort owing to downstaging. Thirty-six patients (4.3%) in the primary cohort and 21 patients (3.6%) in the external validation cohort experienced progressive disease. Clinicopathological features of the patients with HCC who underwent HAIC-based conversion therapy in the training (n=214) and validation (n=128) cohorts are listed in Table 1. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatments of the patients are listed in Supplementary Table (Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A293). The inclusion criteria for this study are depicted in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the patients

| n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Training cohort (N=214) | External validation cohort (N=128) | P |

| Age [median (range)] | 53 (16–79) | 56 (29–82) | 0.846 |

| Sex (male/female) | 177/37 (82.7/17.3) | 109/19 (85.2/14.8) | 0.554 |

| Hepatitis B (yes/no) | 189/25 (88.3/11.7) | 117/11 (91.4/8.6) | 0.368 |

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.02 | ||

| ≤3 | 4 (1.9) | 9 (7) | |

| 3–5 | 15 (7) | 14 (10.9) | |

| ≥5 | 195 (91.1) | 105 (82.1) | |

| HAIC cycles (≤2/2–6/≥6) | 120/83/11 | 68/54/6 | 0.822 |

| Tumor number (solitary/multiple) | 107/107 (50/50) | 89/39 (69.5/30.5) | 0.001 |

| MVI | 0.69 | ||

| 0 | 169 (79) | 100 (78.1) | |

| 1 | 35 (16.4) | 24 (18.8) | |

| 2 | 10 (4.6) | 4 (3.1) | |

| BCLC stage | 0.855 | ||

| A | 87 (40.7) | 54 (42.2) | |

| B | 49 (22.9) | 26 (20.3) | |

| C | 78 (36.4) | 48 (37.5) | |

| CNLC stage | 0.333 | ||

| I | 74 (34.6) | 53 (41.4) | |

| II | 60 (28) | 28 (21.9) | |

| III | 80 (37.4) | 47 (36.7) | |

| ECOG PS (0/1) | 167/47 (78/22) | 92/ 36 (71.9/28.1) | 0.198 |

| Pre-HAIC serum tests | |||

| Platelets (<100/≥100) (×103/μl) | 4/210 (1.9/98.1) | 6/122 (4.7/95.3) | 0.134 |

| PT (≤13.5/>13.5) | 199/15 (93/7) | 118/10 (92.2/7.8) | 0.782 |

| AFP (<400/≥400) (ng/ml) | 95/119 (44.4/55.6) | 79/49 (61.7/38.3) | 0.002 |

| PIVKA-II (<40/≥40) (mAU/ml) | 11/203 (5.1/94.9) | 14/114 (10.9/89.1) | 0.046 |

| CA19-9 (≤35/>35) (U/ml) | 146/68 (69.2/31.8) | 81/47 (63.3/36.7) | 0.349 |

| ALB (≤35/>35) (g/l) | 7/207 (3.3/96.7) | 15/113 (11.7/88.3) | 0.002 |

| TBIL (≤20.5/>20.5) (μmol/l) | 184/30 (86/14) | 112/16 (87.5/12.5) | 0.69 |

| Preoperative serum tests | |||

| Platelets (<100/≥100) (×103/μl) | 25/189 (11.7/88.3) | 15/113 (11.7/88.3) | 0.992 |

| PT (≤13.5/>13.5) | 209/5 (97.7/2.3) | 117/11 (91.4/8.6) | 0.008 |

| AFP (<400/≥400) (ng/ml) | 144/70 (67.3/32.7) | 100/28 (78.1/21.9) | 0.032 |

| PIVKA-II (<40/≥40) (mAU/mL) | 58/156 (27.1/72.9) | 32/96 (25/75) | 0.669 |

| CA19-9 (≤35/>35) (U/ml) | 149/65 (69.6/30.4) | 89/39 (69.5/30.5) | 0.985 |

| ALB (≤35/>35) (g/l) | 11/203 (5.1/94.9) | 12/116 (9.4/90.6) | 0.13 |

| TBIL (≤20.5/>20.5) (μmol/l) | 204/10 (95.4/4.6) | 111/17 (86.7/13.3) | 0.004 |

| Postoperative serum tests | |||

| Platelets (<100/≥100) (×103/μl) | 21/193 (9.8/90.2) | 9/119 (7/93) | 0.379 |

| AFP (≤25/>25) (ng/mL) | 192/22 (89.7/10.3) | 105/23 (82/18) | 0.061 |

| PIVKA-II (<40/≥40) (mAU/ml) | 161/53 (75.2/24.8) | 90/38 (70.3/29.7) | 0.319 |

| CA19-9 (≤35/>35) (U/ml) | 157/57 (73.4/26.6) | 94/34 (73.4/26.6) | 0.988 |

| ALB (≤35/>35) (g/l) | 6/208 (2.8/97.2) | 15/113 (11.7/88.3) | 0.001 |

| TBIL (≤20.5/>20.5) (μmol/l) | 204/10 (95.4/4.6) | 110/18 (85.9/14.1) | 0.002 |

AFP, alpha‐fetoprotein; ALB, albumin; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; CA19-9, carbohydrate antigen 19-9; CNLC, The China Liver Cancer; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score; HAIC, hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy; INR, international normalized ratio; MVI, microvascular invasion; PIVKA-II, protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II; PT, prothrombin time; TBIL, total bilirubin.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the patient enrollment process for the primary and validation cohorts. HAIC, hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

In the training cohort, the median follow-up time was 36.7 months. Tumor recurrence was observed in 63.6% (136 of 214) patients. The median RFS was 10.8 months (95% CI, 8.5–13.1 months). The 1-year, 2-year, and 3-year RFS rates were 46.7, 26.6, and 21.9%, respectively. For the external validation cohort, the median follow-up time was 18.1 months, and 45.3% (58 of 128) of the patients experienced tumor recurrence. The median RFS was 14.1 months (95% CI, 11.4–16.8 months). The 1-year and 2-year RFS rates were 57.3, and 42.9%, respectively.

The median number of treatment cycles of HAIC is 2 (ranging from 1 to 6 cycles) in both training and validation cohorts. The median duration from initiation of HAIC to surgery is 3.2 months (ranging from 0.7 to 13.7 months) in the training cohort and 3.8 months (ranging from 0.8 to 23.8 months) in the validation cohort.

Independent prognostic factors for recurrence and recurrence-free survival in the training cohort

According to multivariate logistic regression analysis, tumor differentiation [odds ratio (OR), 1.696; 95% CI, 1.026–2.803], microvascular invasion (MVI) grade (grade 1 vs. grade 0, OR, 1.452; 95% CI, 1.148–4.704; grade 2 vs. grade 0, OR, 10.309; 95% CI, 1.816–130.179), pre-HAIC AFP level (OR, 6.592; 95% CI, 2.524–17.221), pre-HAIC neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) (OR, 1.815; 95% CI, 1.123–10.248), preoperative NLR (OR, 13.952; 95% CI, 1.185–164.202), preoperative systemic inflammatory response index (SIRI) (OR, 3.142; 95% CI, 1.351–7.306), and postoperative AFP level (OR, 4.669; 95% CI, 1.398–15.591) were independent risk factors of recurrence.

Similarly, multivariate Cox regression analysis identified eight independent risk factors of RFS, which included tumor number [hazard ratio (HR), 1.91; 95% CI, 1.291–2.825], MVI grade (grade 1 vs. grade 0, HR, 1.407; 95% CI, 1.243–2.347; grade 2 vs. grade 0, HR, 1.903; 95% CI, 1.896–4.041), pre-HAIC AFP level (HR, 3.726; 95% CI, 2.133–6.51), pre-HAIC systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) (HR, 1.993; 95% CI, 1.332–2.981), preoperative NLR (HR, 6.432; 95% CI, 2.672–15.483), preoperative SIRI (HR, 1.904; 95% CI, 1.183–3.066), postoperative AFP level (HR, 3.308; 95% CI, 1.847–5.925), and postoperative protein induced by PIVKA-II level (HR, 2.757; 95% CI, 1.83–4.152). The predictors of tumor recurrence and RFS are listed in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses of prognostic factors for recurrence probability in the training cohort

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P |

| Age (≥65 vs. <65) (years) | 2.429 (1.123–5.252) | 0.024 | ||

| ORR (non-ORR vs. ORR) | 2.399 (1.253–4.592) | 0.008 | ||

| Tumor number (multiple vs. solitary) | 1.628 (0.928–2.855) | 0.089 | ||

| Differentiation | 1.74 (1.19–2.545) | 0.004 | 1.696 (1.026–2.803) | 0.039 |

| MVI | ||||

| 1 vs. 0 | 2.828 (1.17–6.839) | 0.021 | 1.452 (1.148–4.704) | 0.034 |

| 2 vs. 0 | 6.364 (0.788–51.374) | 0.082 | 10.309 (1.816–130.179) | 0.017 |

| ALBI grade (grade 2 vs. grade 1) | 2.263 (1.015–5.047) | 0.046 | ||

| ECOG PS | ||||

| Score 1 vs. score 0 | 1.54 (1.261–1.718) | 0.003 | ||

| Score 2 vs. score 0 | 1.851 (0.894–3.833) | 0.097 | ||

| Pre-HAIC AFP (≥400 vs. <400) (ng/ml) | 1.593 (0.902–2.815) | 0.109 | 6.592 (2.524–17.221) | <0.001 |

| Pre-HAIC CA19-9 (>35 vs. ≤35) (U/ml) | 1.582 (0.853–2.935) | 0.146 | ||

| Pre-HAIC NLR (≥5 vs. <5) | 5.429 (1.22–24.163) | 0.026 | 1.815 (1.123–10.248) | 0.025 |

| Pre-HAIC SII (≥609.9 vs. <609.9) | 1.767 (1.006–3.106) | 0.048 | ||

| Preoperative AFP (≥400 vs.<400) (ng/ml) | 2.063 (1.099–3.875) | 0.024 | ||

| Preoperative PIVKA-II (>40 vs. ≤40) (mAU/ml) | 1.333 (0.719–2.473) | 0.015 | ||

| Preoperative CA19-9 (>35 vs. ≤35) (U/ml) | 2.182 (1.138–4.187) | 0.001 | ||

| Preoperative SIRI (≥1.1 vs.<1.1) | 1.748 (0.953–3.205) | 0.071 | 3.142 (1.351–7.306) | 0.008 |

| Preoperative NLR (≥5 vs.<5) | 5.457 (0.678–43.909) | 0.111 | 13.952 (1.185–164.202) | 0.036 |

| Postoperative AFP (>25 vs. ≤25) (ng/ml) | 4.08 (1.929–8.63) | <0.001 | 4.669 (1.398–15.591) | 0.012 |

| Postoperative PIVKA-II (>40 vs. ≤40) (mAU/ml) | 3.144 (1.477–6.695) | 0.003 | ||

| Postoperative CA19-9 (>35 vs. ≤35) (U/l) | 1.877 (0.96–3.669) | 0.066 | ||

AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; ALBI, albumin–bilirubin; CA19-9, carbohydrate antigen 19-9; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score; HAIC, hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy; MVI, microvascular invasion; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; OR, odds ratio; ORR, objective response rate; PIVKA-II, protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II; SII, systemic immune-inflammation index; SIRI, systemic inflammatory response index.

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses of prognostic factors for recurrence-free survival in the training cohort

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P |

| Age (≥65 vs.<65) (years) | 1.441 (1.092–1.902) | 0.01 | ||

| ORR (non-ORR vs. ORR) | 1.617 (1.141–2.292) | 0.007 | ||

| Tumor number (multiple vs. solitary) | 1.521 (1.083–2.137) | 0.016 | 1.91 (1.291–2.825) | 0.001 |

| Differentiation | 1.432 (1.148–1.786) | 0.001 | ||

| MVI | ||||

| 1 vs. 0 | 2.486 (1.623–3.81) | <0.001 | 1.407 (1.243–2.347) | 0.019 |

| 2 vs. 0 | 2.325 (1.171–4.615) | 0.016 | 1.903 (1.896–4.041) | 0.009 |

| ALBI grade (grade 2 vs. grade 1) | 1.542 (1.03–2.309) | 0.134 | ||

| ECOG PS | ||||

| Score 1 vs. score 0 | 1.987 (0.276–14.308) | 0.095 | ||

| Score 2 vs. score 0 | 1.472 (0.992–2.185) | 0.055 | ||

| Pre-HAIC AFP (≥400 vs. <400) (ng/ml) | 1.239 (0.883–1.739) | 0.105 | 3.726 (2.133–6.51) | <0.001 |

| Pre-HAIC CA19-9 (>35 vs. ≤35) (U/ml) | 1.324 (0.93–1.884) | 0.119 | ||

| Pre-HAIC NLR (≥5 vs. <5) | 2.126 (1.273–3.549) | 0.004 | ||

| Pre-HAIC SII (≥609.9 vs. <609.9) | 1.507 (1.072–2.117) | 0.018 | 1.993 (1.332–2.981) | 0.001 |

| Preoperative AFP (≥400 vs.<400) (ng/ml) | 1.739 (1.228–2.461) | 0.002 | ||

| Preoperative CA19-9 (>35 vs. ≤35) (U/ml) | 1.392 (0.979–1.978) | 0.066 | ||

| Preoperative SIRI (≥1.1 vs.<1.1) | 1.117 (1.015–2.049) | 0.049 | 1.904 (1.183–3.066) | 0.008 |

| Preoperative NLR (≥5 vs.<5) | 2.713 (1.375–5.351) | 0.004 | 6.432 (2.672–15.483) | <0.001 |

| Postoperative AFP (>25 vs. ≤25) (ng/l) | 2.768 (1.948–3.934) | <0.001 | 3.308 (1.847–5.925) | <0.001 |

| Postoperative PIVKA-II (>40 vs. ≤40) (mAU/ml) | 2.6 (1.806–3.745) | <0.001 | 2.757 (1.83–4.152) | <0.001 |

| Postoperative CA19-9 (>35 vs. ≤35) (U/l) | 1.277 (0.887–1.839) | 0.189 | ||

| Postoperative NLR (≥5 vs.<5) | 2.267 (0.835–6.156) | 0.108 | ||

| Postoperative SIRI (≥1.1 vs. <1.1) | 0.737 (0.47–1.155) | 0.183 | ||

AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; ALBI, albumin–bilirubin; CA19-9, carbohydrate antigen 19-9; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score; HAIC, hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy; HR, hazard ratio; MVI, microvascular invasion; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; ORR, objective response rate; PIVKA-II, protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II; SII, systemic immune-inflammation index; SIRI, systemic inflammatory response index.

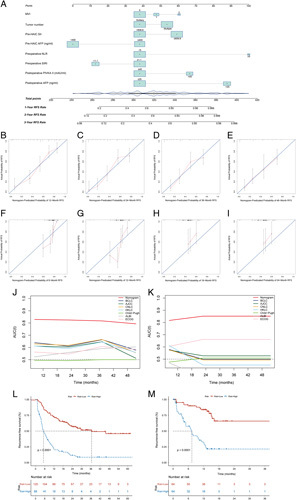

Prognostic nomograms for recurrence and recurrence-free survival

Nomograms to predict the recurrence probability and RFS of patients with HCC receiving HAIC-based conversion hepatectomy are illustrated in Figures 2A and 3A. The nomograms used to predict the probability of tumor recurrence and RFS were built based on the independent risk factors identified by multivariate analysis. Significant prognostic factors predicting the probability of tumor recurrence include tumor differentiation, MVI grade, pre-HAIC AFP level, pre-HAIC NLR, preoperative NLR, preoperative SIRI, and postoperative AFP level. Independent risk factors for RFS included tumor number, MVI grade, pre-HAIC AFP level, pre-HAIC SII, preoperative NLR, preoperative SIRI, postoperative AFP level, and postoperative PIVKA-II level. For example, a patient with MVI grade 0, poor tumor differentiation, pre-HAIC AFP<400 ng/ml, pre-HAIC NLR<5, preoperative NLR<5, preoperative SIRI≥1.1, and postoperative AFP>25 ng/ml would score a total of 214 points (18 points for MVI grade, 100 points for tumor differentiation, 0 points for pre-HAIC AFP level, 18 points for pre-HAIC NLR, 18 points for preoperative NLR, 18 points for preoperative SIRI, and 42 points for postoperative AFP), which corresponded to 86% probability of recurrence. Similarly, a patient with MVI grade 2, multiple tumors, pre-HAIC SII<609.9, pre-HAIC AFP<400 ng/ml, preoperative NLR<5, preoperative SIRI≥1.1, postoperative PIVKA-II>40 mAU/ml, and postoperative AFP ≤25 ng/ml would have a total of 332 points (60 points for MVI, 54 points for tumor number, 38 points for pre-HAIC SII, 0 points for pre-HAIC AFP, 38 points for preoperative NLR, 38 points for preoperative SIRI, 66 points for postoperative PIVKA-II, and 38 points for postoperative AFP). For this case, the predicted probability of 1-year, 2-year, and 3-year RFS was 80.0, 71.0, and 56.0%, respectively.

Figure 2.

Development and performance of the nomogram for predicting tumor recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma patients following HAIC-based conversion hepatectomy. (A) Nomogram for predicting the probability of tumor recurrence generated based on clinicopathological factors. (B and C) Calibration plots for predicting tumor recurrence in the primary cohort and the external validation cohort. (D and E) ROC curves of the nomogram for predicting tumor recurrence in the primary cohort and the external validation cohort. (F and G) ROC curves showing the performance of the nomogram and other models for predicting tumor recurrence in the primary cohort and the external validation cohort. AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; ALBI, albumin–bilirubin; AUC area under the curve; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; CNLC, The China Liver Cancer; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score; HAIC, hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy; HKLC, Hong Kong Liver Cancer; MVI, microvascular invasion; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; SIRI, systemic inflammatory response index.

Figure 3.

Development and performance of the nomogram for predicting recurrence-free survival of hepatocellular carcinoma patients following HAIC–based conversion hepatectomy. (A) Nomogram for predicting the RFS rate developed based on clinicopathological features. (B–E) Calibration plots for predicting 1-year, 2-year, 3-year, and 4-year RFS in the primary cohort. (F–I) Calibration plots for predicting 1-year, 2-year, 3-year, and 4-year RFS in the external validation cohort. (J and K) Time-dependent receiver operating characteristic values showing the performance of the nomogram and other systems for predicting RFS in the primary cohort and the external validation cohort. (L and M) RFS was compared between patients with nomogram median score in the primary cohort and the external validation cohort. AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; ALBI, albumin–bilirubin; AUC area under the curve; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; CNLC, The China Liver Cancer; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score; HAIC, hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy; HKLC, Hong Kong Liver Cancer; MVI, microvascular invasion; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PIVKA-II, protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II; RFS, recurrence-free survival; SII, systemic immune-inflammation index; SIRI, systemic inflammatory response index.

Performance of the nomogram in predicting tumor recurrence

Internal validation was performed using bootstrapping with 1000 replications. An unadjusted C-index of 0.822 and a bootstrap-corrected C-index of 0.80 indicate good prediction accuracy for tumor recurrence by the model. In addition, the calibration curve exhibited good agreement between the predictions and observed outcomes with Brier scores of 0.162 and 0.178 in both cohorts, respectively (Fig. 2B and C). The areas under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for the probability of tumor recurrence were 0.822 (95% CI, 0.703–0.858) and 0.802 (95% CI, 0.726–0.878) for the primary and external validation cohorts, respectively (Fig. 2D and E).

The ROC value of the nomogram for predicting the probability of tumor recurrence were higher than those of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) eighth staging system (0.822 vs. 0.60), Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system (0.822 vs. 0.60), China Liver Cancer (CNLC) staging system (0.822 vs. 0.60), Hong Kong Liver Cancer (HKLC) staging system (0.822 vs. 0.58), Child–Pugh class (0.822 vs. 0.49), albumin–bilirubin (ALBI) grade (0.822 vs. 0.56), and ECOG performance score (0.822 vs. 0.55) in the primary cohort. (Fig. 2F). Similar results were observed in the external validation cohort (0.80 vs. 0.56, 0.80 vs. 0.52, 0.80 vs. 0.55, 0.80 vs. 0.58, 0.80 vs. 0.50, 0.80 vs. 0.53, and 0.80 vs. 0.55) (Fig. 2G).

Performance of the nomogram in predicting recurrence-free survival

Internal validation was performed using the bootstrap method. The C-index were 0.769 (95% CI, 0.731–0.814) in the primary cohort and 0.777 (95% CI, 0.719–0.835) in the external validation cohort. Based on the calibration curves, the nomogram-estimated probabilities of RFS at 1, 2, 3, and 4 years were in concordance with the actual rate in the primary cohort (Fig. 3B–E). Similar results were observed in the external validation cohort (Fig. 3F–I).

The 1-year, 2-year, and 3-year RFS rates predicted by the nomogram were higher than those predicted by the BCLC (0.842, 0.839, 0.839 vs. 0.639, 0.611, 0.664), AJCC eighth (0.842, 0.839, 0.839 vs. 0.611, 0.603, 0.647), CNLC (0.842, 0.839, 0.839 vs. 0.629, 0.617, 0.665), HKLC staging systems (0.842, 0.839, 0.839 vs. 0.612, 0.59, 0.645), Child–Pugh class (0.842, 0.839, 0.839 vs. 0.493, 0.489, 0.504), ALBI grade (0.842, 0.839, 0.839 vs. 0.528, 0.564, 0.596), and ECOG performance status (0.842, 0.839, 0.839 vs. 0.568, 0.551, 0.613), in the primary cohort. Similar results were obtained in the external validation cohort (0.814, 0.843, 0.841 vs. 0.569, 0.499, 0.498; 0.814, 0.843, 0.841 vs. 0.568, 0.532, 0.531; 0.814, 0.843, 0.841 vs. 0.566, 0.495, 0.495; 0.814, 0.843, 0.841 vs. 0.571, 0.421, 0.419; 0.814, 0.843, 0.841 vs. 0.489, 0.518, 0.517; 0.814, 0.843, 0.841 vs. 0.453, 0.427, 0.424; 0.814, 0.843, 0.841 vs. 0.628, 0.659, 0.657). Time-dependent ROCs are shown in Figure 3J and K.

The assessment of the discriminative ability of the nomogram in predicting the probability of RFS was plotted as Kaplan–Meier curves stratified by the median risk scores calculated from the models. For the probability of RFS, patients were stratified into low-risk and high-risk subgroups by the nomogram with 1-year recurrence rates of 29.4 and 79.5%, respectively (P<0.001); 2-year recurrence rates of 54.8 and 90.9%, respectively (P<0.001); and 3-year recurrence rates of 81.7 and 95.5%, respectively (P<0.01) in the primary cohort. In the external validation cohort, patients were also divided into low-risk and high-risk subgroups, with 1-year recurrence rates of 40.6 and 75%, respectively (P<0.001); 2-year recurrence rates of 95.3 and 98.4%, respectively (P=0.05). Moreover, patients in the high-risk group had a lower RFS rate than those in the low-risk group (primary cohort, low risk vs. high risk, 36.5 vs. 5.2 months, P<0.001; external validation cohort, low risk vs. high risk, median not achieved vs. 6.7 months, P<0.001). Kaplan–Meier curves are plotted in Figure 3L and M.

Kaplan–Meier curves for RFS in the primary and external validation cohorts were generated using different conventional staging systems. Although significant prognostic strata were observed in most of the staging systems as shown by the Kaplan–Meier curves (P<0.05) in the primary cohort, some overlapping of the Kaplan–Meier curves was detected for the BCLC, AJCC eighth, CNLC, and HKLC staging systems. Likewise, the Kaplan–Meier curves displayed significant prognostic strata for most of the staging systems (P<0.05), except for BCLC, AJCC eighth, CNLC, Child–Pugh, and ALBI in the external cohort. The results are illustrated in Figure S1 (Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A294) and Figure S2 (Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A295).

Discussion

Radical liver resection is one of the most important treatments for long-term survival of patients with HCC25. However, due to the biological characteristics of HCC, many patients lose their opportunity to undergo radical surgery at diagnosis due to the presence of locally advanced disease or metastasis, which is a critical factor leading to the poor outcome of patients with HCC4,25. Vascular invasion and multiple lesions have long been recognized as key risk factors for HCC recurrence following hepatectomy, and should be considered as potential contraindications to surgery16,26. Nevertheless, studies have pointed out that survival benefits from liver resections occur in patients with intermediate and advanced stages of HCC, even in those with a high postresection recurrence rate5. Hence, the resection rates should be increased. In recent years, conversion therapy has provided patients with initially unresectable tumors, the opportunity to undergo surgery, thereby improving their survival rate even to a level comparable to that of patients who initially received hepatectomy20. Nonetheless, a high postoperative recurrence rate remains a challenge to achieving long-term survival, especially in patients who have undergone conversion liver resection19,20. These patients may have high recurrence risk before surgery, such as large tumor size, multiple lesions, and vascular invasion, which would theoretically have a higher recurrence rate after surgery. Thus, while pursuing a higher surgical resection rate, preventing or reducing tumor recurrence after surgery is pivotal for improving patient survival.

Similarly, 63.6% (136 of 214 cases) of patients who underwent HAIC-based conversion hepatectomy had postoperative tumor recurrence in the training cohort and 45.3% (58 of 128 cases) of patients had recurrence in the validation cohort. Our findings indicated that tumor differentiation, tumor number, presence of MVI, pre-HAIC AFP level, pre-HAIC NLR, pre-HAIC SII, preoperative NLR, preoperative SIRI, postoperative AFP level, and postoperative PIVKA-II level were independent risk factors for tumor recurrence or RFS. Based on this retrospective analysis involving patients from four institutions, two prognostic nomograms that integrated clinicopathological parameters were developed to predict recurrence probability and RFS after HAIC-based conversion hepatectomy. To our knowledge, this is the first predictive nomogram developed for patients with HCC who underwent HAIC-based conversion liver resection, which may provide a convenient tool for identifying patients with a high risk of recurrence and low RFS rates who would benefit from postoperative individualized treatment and intermittent monitoring. The C-indices of the recurrence and RFS prediction models were 0.822 and 0.769, respectively, indicating good prediction accuracy. Moreover, the calibration curve indicated that the actual values were highly consistent with observed values. There are definite differences in baseline assessments between the training and validation cohorts, such as tumor number, pre-HAIC AFP level, pre-HAIC ALB level. However, our predictive nomograms achieved satisfactory C-indices in both cohorts, which provided strong evidence that the nomograms worked reasonably well in different patient populations.

Another strength of this study is that the variables in the models were commonly available in clinical practice. Some have been reported to be associated with the prognosis after liver resection. Among these factors, AFP and PIVKA II are two major tumor markers that are widely used and known biomarkers for diagnosing, monitoring, and managing HCC27,28. The combined use of these two indicators can improve the diagnostic yield of HCC29,30. In particular, serum tumor markers in postoperative reviews have the potential to detect tumor recurrence at the earliest possible stage after surgery. Multiple tumor lesions and the presence of MVI have been confirmed to be significantly associated with HCC recurrence31,32. Tumors with poor differentiation are biologically more aggressive, which may substantially affect their recurrence and long-term survival33. These studies support our findings, showing an association between recurrence and important clinicopathological features, such as the level of serum tumor markers, the presence of MVI, and the number of tumor lesions. Alteration of inflammatory biomarkers, which may be related to local tumors or inflammatory immune responses, has been proven to be associated with tumor patient outcomes recently34,35. Given that the liver is a vital immune organ, the initiation and progression of liver malignancies are associated with immune escape36. In actual clinical practice, some patients with HCC treated with HAIC can achieve a satisfactory objective response rate, which may be attributed to the localized tumor-associated inflammatory immune responses triggered by the necrotic death of tumor cells to achieve a synergistic antitumor effect. Previous clinical studies have established that HAIC combined with ICIs may benefit advanced liver cancer patients18,37. In addition, inflammatory biomarkers can potentially predict the efficacy and adverse effects of HAIC combined with ICIs therapy38. Our findings revealed that inflammatory biomarkers related to the prognosis of HCC, including NLR, SII, and SIRI, are also closely associated with the recurrence and RFS of patients with HCC. A nomogram is an easy-to-use tool for constructing a graphical predictive model that generates the numerical probability of a clinical event39. Besides, the nomogram has good predictive and discriminant validity for individuals, which may assist in clinical decision-making39. In this study, the nomograms outperformed traditional generic staging systems, such as BCLC, AJCC, and CNLC, with regard to discrimination. Compared with traditional staging systems, the two prognostic nomograms demonstrated the advantage of higher accuracy in predicting recurrence probability and RFS for patients treated with HAIC-based conversion liver resection.

Conversion liver resection has been the focus of current research and is of enormous importance in treating patients with HCC19,20. Curative liver resection is the best option to achieving long-term survival16. However, ∼80% of patients with HCC are inoperable at the initial diagnosis because of local tumor invasion or distant metastasis. These tumors often exhibit large volumes, multiple lesions, or vascular invasion3,4. Conversion therapy may render originally inoperable tumors resectable by various means10,40. Transcatheter interventional therapy, such as transarterial chemoembolization and HAIC, is currently one of the most commonly used conversion therapies for HCC10,20. Notably, HAIC confers survival benefit to patients with liver cancer at different stages, especially those in the intermediate and advanced stages12,41. Compared with transarterial chemoembolization or sorafenib treatment, HAIC showed superior therapeutic efficacy12,42. Hence, it is believed that HAIC will attract more attention and appreciation as an important treatment option in the near future.

By retrospectively analyzing patients with HCC treated with HAIC-based conversion hepatectomy, this study constructed and validated risk models to predict the probability of recurrence and RFS rate, which provided patients with a high recurrence risk with an empirically based rationale for intervention during the perioperative period. Theoretically, patients undergoing conversion liver resection are at more advanced tumor stages than those undergoing radical surgical resection at the initial diagnosis20. Tumor recurrence is a serious problem in patients with HCC after hepatic resection. The recurrence rate was higher in patients who underwent conversion hepatectomy than in those who underwent initial radical resection20. Accordingly, the surveillance interval should be shortened in patients undergoing conversion therapy. More importantly, for patients with high-risk recurrence features, such as the presence of MVI, multiple lesions, and poor tumor differentiation, postoperative adjuvant therapy should be considered following conversion hepatectomy. For patients with a low risk of recurrence, reducing the use of adjuvant therapies such as chemotherapy may be considered.

The current study had several limitations. First, as it was a retrospective study, shortcomings related to the retrospective design are acknowledged. At present, most studies on HAIC originated from Asian countries. While most studies showed that HAIC could bring survival benefits to HCC patients, some reported that the clinical benefit of HAIC is equivocal12,13,43. Although the nomograms established herein demonstrated good calibration and discrimination in the training and validation cohorts, future studies with larger sample size, patient recruitment from global multicenters, and prospective evaluations are warranted to validate these findings. Second, as in all retrospective studies, selection bias is inevitable. Finally, the nomograms in this study were generated using clinicopathological factors which are easily available; hence, more specific markers need to be explored to improve the accuracy of the model in predicting tumor recurrence probability and patient survival rates.

Conclusions

We developed two reliable nomograms to predict the probability of recurrence and RFS in patients with HCC following HAIC-based conversion hepatectomy. Our findings may guide clinicians in developing personalized therapeutic strategies for patients undergoing HAIC-based liver resection.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of SYSUCC (No. B202031801).

Sources of funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82172579, No. 81871985); Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (No. 2018A0303130098 and No. 2017A030310203); Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province (No. 2017A020215112); Medical Scientific Research Foundation of Guangdong Province (No. A2017477); Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangzhou (No. 201903010017 and No. 201904010479); Clinical Trials Project (5010 Project) of Sun Yat-sen University (No. 5010-2017009); and Clinical Trials Project (308 Project) of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center (No. 308-2015-014).

Author contribution

M.D.: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, software and visualization, writing – original draft. Q.L. and J.W.: data curation, methodology, writing – original draft. C.L.: methodology, software, and visualization. R. Guan: formal analysis, software, and visualization. S.L.: data curation. W.W.: methodology and data curation. H.C.: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, writing – review and editing. C.Z.: conceptualization, data curation, methodology, supervision, writing – review and editing. R. Guo: conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, methodology, supervision, writing – review and editing.

Conflicts of interest disclosure

The authors declare that they have no financial conflict of interest with regard to the content of this report.

Research registration unique identifying number (UIN)

Name of the registry: Research Registry; Nomograms to predict the recurrence probability and recurrence-free survival for hepatocellular carcinoma after conversion hepatectomy based on hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy: A multicenter, retrospective study

Unique Identifying number or registration ID: researchregistry8524.

Hyperlink to your specific registration (must be publicly accessible and will be checked): 4. https://www.researchregistry.com/browse-theregistry#home/registrationdetails/638c59be1ff953002165bf6d

Guarantor

Rongping Guo.

Data availability statement

All data used during the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge and express their deepest gratitude to the participants of this research.

Footnotes

Min Deng, Qiucheng Lei, and Jiamin Wang contributed equally to this work.

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website, www.journal-surgery.net.

Published online 11 April 2023

Contributor Information

Min Deng, Email: dengmin@sysucc.org.cn.

Qiucheng Lei, Email: 47723543@qq.com.

Jiamin Wang, Email: 263385180@qq.com.

Carol Lee, Email: dengminmei@sina.com.

Renguo Guan, Email: dengmin0207@126.com.

Shaohua Li, Email: dm.engineer@163.com.

Wei Wei, Email: weiweisysucc@outlook.com.

Huanwei Chen, Email: zjwsysucc@outlook.com.

Chong Zhong, Email: zhongchongtcmg@outlook.com.

Rongping Guo, Email: guorongpingsysucc@outlook.com.

References

- 1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021;71:209–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Villanueva A. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2019;380:1450–1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Anwanwan D, Singh SK, Singh S, et al. Challenges in liver cancer and possible treatment approaches. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 2020;1873:188314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2021;7:6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhou J, Sun H, Wang Z, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (2019 Edition. Liver Cancer 2020;9:682–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gilgoff IS, Kahlstrom E, MacLaughlin E, et al. Long-term ventilatory support in spinal muscular atrophy. J Pediatr 1989;115:904–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Krenzien F, Schmelzle M, Struecker B, et al. Liver transplantation and liver resection for cirrhotic patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison of long-term survivals. J Gastrointest Surg 2018;22:840–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yang X, Xu H, Zuo B, et al. Downstaging and resection of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with extrahepatic metastases after stereotactic therapy. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr 2021;10:434–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Utsunomiya T, Shimada M, Kudo M, et al. A comparison of the surgical outcomes among patients with HBV-positive, HCV-positive, and non-B non-C hepatocellular carcinoma: a nationwide study of 11 950 patients. Ann Surg 2015;261:513–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kumar Y, Sharma P, Bhatt N, et al. Transarterial therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma: a comprehensive review with current updates and future directions. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2016;17:473–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gunasekaran G, Bekki Y, Lourdusamy V, et al. Surgical treatments of hepatobiliary cancers, eng. Hepatology 2020;73(suppl):128–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. He M, Li Q, Zou R, et al. Sorafenib plus hepatic arterial infusion of oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin vs sorafenib alone for hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein invasion: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2019;5:953–960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li SH, Mei J, Cheng Y, et al. Postoperative adjuvant hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy with FOLFOX in hepatocellular carcinoma with microvascular invasion: a multicenter, phase III, randomized study. J Clin Oncol 2023;41:1898–1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Choi JH, Chung WJ, Bae SH, et al. Randomized, prospective, comparative study on the effects and safety of sorafenib vs. hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein tumor thrombosis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2018;82:469–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nouso K, Miyahara K, Uchida D, et al. Effect of hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy of 5-fluorouracil and cisplatin for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in the Nationwide Survey of Primary Liver Cancer in Japan. Br J Cancer 2013;109:1904–1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Reig M, Forner A, Rimola J, et al. BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation: The 2022 update. J Hepatol 2022;76:681–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sangro B, Sarobe P, Hervas-Stubbs S, et al. Advances in immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;18:525–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mei J, Li SH, Li QJ, et al. Anti-PD-1 immunotherapy improves the efficacy of hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatocell Carcinoma 2021;8:167–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang W, Hu B, Han J, et al. Surgery after conversion therapy with PD-1 inhibitors plus tyrosine kinase inhibitors are effective and safe for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a pilot study of ten patients. Front Oncol 2021;11:747950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhu XD, Huang C, Shen YH, et al. Downstaging and resection of initially unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma with tyrosine kinase inhibitor and anti-PD-1 antibody combinations. Liver Cancer 2021;10:320–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, et al. Diagnosis, staging, and management of hepatocellular carcinoma: 2018 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2018;68:723–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mathew G, Agha R. STROCSS Group. STROCSS 2021: Strengthening the reporting of cohort, cross-sectional and case-control studies in surgery. Int J Surg 2021;96:106165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li S, Deng M, Wang Q, et al. Transarterial infusion chemotherapy with FOLFOX could be an effective and safe treatment for unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Oncol 2022;2022:2724476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis 2010;30:52–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2018;69:182–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Llovet JM, Bru C, Bruix J. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: the BCLC staging classification. Semin Liver Dis 1999;19:329–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Daniele B, Bencivenga A, Megna AS, et al. Alpha-fetoprotein and ultrasonography screening for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2004;127(suppl 1):S108–S112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang YS, Chu JH, Cui SX, et al. Des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin (DCP) as a potential autologous growth factor for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Physiol Biochem 2014;34:903–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Okuda K. Hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2000;32(suppl):225–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Inagaki Y, Tang W, Makuuchi M, et al. Clinical and molecular insights into the hepatocellular carcinoma tumour marker des-gamma-carboxyprothrombin. Liver Int 2011;31:22–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lim KC, Chow PK, Allen JC, et al. Microvascular invasion is a better predictor of tumor recurrence and overall survival following surgical resection for hepatocellular carcinoma compared to the Milan criteria. Ann Surg 2011;254:108–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hung HH, Lei HJ, Chau GY, et al. Milan criteria, multi-nodularity, and microvascular invasion predict the recurrence patterns of hepatocellular carcinoma after resection. J Gastrointest Surg 2013;17:702–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nathan H, Schulick RD, Choti MA, et al. Predictors of survival after resection of early hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg 2009;249:799–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bruix J, Cheng AL, Meinhardt G, et al. Prognostic factors and predictors of sorafenib benefit in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis of two phase III studies. J Hepatol 2017;67:999–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mao S, Yu X, Sun J, et al. Development of nomogram models of inflammatory markers based on clinical database to predict prognosis for hepatocellular carcinoma after surgical resection. BMC Cancer 2022;22:249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zongyi Y, Xiaowu L. Immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett 2020;470:8–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Deng M, Li S, Wang Q, et al. Real-world outcomes of patients with advanced intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma treated with programmed cell death protein-1-targeted immunotherapy. Ann Med 2022;54:803–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mei J, Sun XQ, Lin WP, et al. Comparison of the prognostic value of inflammation-based scores in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after anti-PD-1 therapy. J Inflamm Res 2021;14:3879–3890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Iasonos A, Schrag D, Raj GV, et al. How to build and interpret a nomogram for cancer prognosis. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:1364–1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yim HJ, Suh SJ, Um SH. Current management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an Eastern perspective. World J Gastroenterol 2015;21:3826–3842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Li S, Zhong C, Li Q, et al. Neoadjuvant transarterial infusion chemotherapy with FOLFOX could improve outcomes of resectable BCLC stage A/B hepatocellular carcinoma patients beyond Milan criteria: an interim analysis of a multi-center, phase 3, randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 2021;39(suppl):4008. [Google Scholar]

- 42. He MK, Le Y, Li QJ, et al. Hepatic artery infusion chemotherapy using mFOLFOX versus transarterial chemoembolization for massive unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective non-randomized study. Chin J Cancer 2017;36:83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhao J, Li D, Shi Y, et al. Transarterial infusion chemotherapy with and without embolisation in hepatocellular carcinoma patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Acad Med Singap 2017;46:174–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data used during the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.