Background:

Guidelines do not provide clear recommendations with regard to the use of low intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) during laparoscopic surgery. The aim of this meta-analysis is to assess the influence of low versus standard IAP during laparoscopic surgery on the key-outcomes in perioperative medicine as defined by the StEP-COMPAC consensus group.

Materials and methods:

We searched the Cochrane Library, PubMed, and EMBASE for randomized controlled trials comparing low IAP (<10 mmHg) with standard IAP (10 mmHg or higher) during laparoscopic surgery without time, language, or blinding restrictions. According to the PRISMA guidelines, two review authors independently identified trials and extracted data. Risk ratio (RR), and mean difference (MD), with 95% CIs were calculated using random-effects models with RevMan5. Main outcomes were based on StEP-COMPAC recommendations, and included postoperative complications, postoperative pain, postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) scores, and length of hospital stay.

Results:

Eighty-five studies in a wide range of laparoscopic procedures (7349 patients) were included in this meta-analysis. The available evidence indicates that the use of low IAP (<10 mmHg) leads to a lower incidence of mild (Clavien–Dindo grade 1–2) postoperative complications (RR=0.68, 95% CI: 0.53–0.86), lower pain scores (MD=−0.68, 95% CI: −0.82 to 0.54) and PONV incidence (RR=0.67, 95% CI: 0.51–0.88), and a reduced length of hospital stay (MD=−0.29, 95% CI: −0.46 to 0.11). Low IAP did not increase the risk of intraoperative complications (RR=1.15, 95% CI: 0.77–1.73).

Conclusions:

Given the established safety and the reduced incidence of mild postoperative complications, lower pain scores, reduced incidence of PONV, and shorter length of stay, the available evidence supports a moderate to strong recommendation (1a level of evidence) in favor of low IAP during laparoscopic surgery.

Keywords: complications, intra-abdominal pressure, laparoscopic surgery, pneumoperitoneum, StEP-COMPAC outcomes

Introduction

Highlights

Low pressure laparoscopy reduces early pain scores, postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) and length of stay.

Low pressure laparoscopy reduces the risk of mild postoperative complications.

Low pressure laparoscopy does not increase the rate of intraoperative complications.

The use of low intra-abdominal pressure (IAP) during laparoscopic surgery is recommended.

The Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) guidelines constitute a major advancement in evidence-based improvement of postoperative patient outcomes. Continuous updating of these guidelines with the latest clinical trial evidence allows for the most advanced level of patient care. One of the elements included in many of the ERAS Society protocols is minimally invasive or laparoscopic surgery, advocated for fewer complications and a quicker recovery. While the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery consensus guidelines advises using the lowest IAP with an adequate view of the surgical field1, the ERAS Society seems to recognize the importance of IAP but is conservative in their current recommendations. The ERAS guidelines for gastrointestinal2,3, colorectal4, gynecologic5 and bariatric6 surgery all discuss some strategies as neuromuscular blockade allows for lower insufflation pressures, but no target level of pressure is explicitly recommended. For more specialized procedures such as gastrectomy7, liver resection8, esophagectomy9 and pancreatoduodenectomy10, evidence regarding minimally invasive surgery is limited and IAP is not mentioned. Heterogeneity between guidelines due to inconsistent evidence concerning the safety and efficacy of low pneumoperitoneum pressure probably explains the large variability in routine clinical practice. The standard practice in most centers, is set the IAP to a routine pressure of 12–15 mmHg11 instead of the lowest possible IAP with an adequate view of the surgical field. Although a consensus definition is lacking, we predefined low pneumoperitoneum pressure as an IAP less than 10 mmHg in line with the described perfusion pressure in the distal segment of the capillary network of the parietal peritoneum12. Moreover, a sustained increase in IAP of 12 mmHg or higher is defined as intra-abdominal hypertension and could lead to organ ischemia13–15. There is physiological evidence that low IAP reduces postoperative pain scores16,17 and recent studies from our group show that acute pain in the first hours to days after surgery correlates with 30-day complications18,19. While a causal relationship between early pain scores and complications after surgery has not been fully established, it is compelling to hypothesize that strategies that decrease early postoperative pain may reduce complications after surgery. In a previous systematic review and meta-analysis16, postoperative complications could not be included as outcome measure due to insufficient reporting. Also, sufficient data with regard to safety and other clinical outcomes were lacking. Moreover, only relatively small studies with high/unclear risk of bias were available for the meta-analysis published in 2016. Therefore, an updated analysis of the available clinical evidence concerning the impact of the IAP during laparoscopic surgery is warranted.

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to assess the influence of low IAP during laparoscopic surgery on clinical and patient core outcomes in perioperative care as defined by the Standardized Endpoints in Perioperative medicine – Core Outcome Measures for Perioperative and Anesthetic Care (StEP-COMPAC) consensus group20.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

This review was conducted according to the PRISMA guidelines recommended by the Cochrane Handbook21, see PRISMA checklist in Supplement (Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A270). The PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane databases were searched without time, language and blinding restrictions. Thereafter, references and cross-references were searched by hand. The last search was carried out in November 2021. The databases were searched with ‘laparoscopy,’ ‘peritoneoscopy,’ ‘coelioscopy,’ and ‘celioscopy,’ and with ‘pneumoperitoneum,’ ‘artificial pneumoperitoneum,’ and ‘insufflation’ in Mesh term with an exploration of all trees and of titles or abstracts with word variations. This resulted in the following search strategies:

In PubMed: (laparoscop* OR coelioscop* OR celioscop* OR peritoneoscop*) AND (pneumoperitoneum OR pneumoperitoneum, Artificial [MeSH] OR insufflations OR insufflation [MeSH] AND (randomized controlled trial [pt] OR controlled clinical trial [pt] OR randomized [tiab] OR randomly [tiab] OR trial [tiab]).

In EMBASE: (exp Laparoscopy/ OR laparoscop*.ti,ab,kw. OR peritoneoscop*.ti,ab,kw. OR coelioscop*.ti,ab,kw. OR celioscop*.ti,ab,kw.) AND (Pneumoperiton*.ti,ab,kw. OR Pneumo-periton*.ti,ab,kw. OR artificial pneumoperitoneum/ OR Pneumoperitoneum/ OR insufflation/).

In Cochrane library: (MeSH [Laparoscopy] OR (laparoscop* OR peritoneoscop* OR coelioscop* OR celioscop*):ti,ab,kw OR MeSH [pneumoperitoneum] OR [pneumoperitoneum, artificial] OR [insufflation] OR (Pneumoperiton* OR Pneumo-periton*):ti,ab,kw.

Data outcomes

The StEP-COMPAC consensus defined some clinical and patient-centered core outcomes divided over six domains for use in perioperative clinical trials20. Mortality/survival; perioperative complications; resource use; short-term recovery after surgery; longer term recovery after surgery and overall success/failure of surgery. In line with StEP-COMPAC, the main outcomes of this meta-analysis included the core outcomes of all domains.

In addition, we included secondary outcomes related to patient safety and surgical procedural feasibility and success, including intraoperative complications, quality of the surgical working field (quantified with the Leiden Surgical Rating Scale), the incidence of conversion to laparotomy or higher IAP, duration of surgery and blood loss. Other collected data were mean age, sex, BMI, type of procedure, depth of neuromuscular block (NMB), incidence of shoulder pain, analgesia use (morphine equivalent), heart rate, mean arterial blood pressure, end-tidal CO2, liver enzymes, and indicators of inflammation of immune suppression. For missing or unclear information, authors of the original articles were contacted. If no reply was received, SDs were calculated if sufficient data were available22.

Eligibility criteria

All randomized controlled trials in human adults comparing IAPs lower than 10 versus 10 mmHg or higher, for standard or robotic laparoscopic intra-abdominal, intraperitoneal procedures were eligible. Studies published in all languages were included and translated if applicable.

Selection process and data extraction

All search results were imported in Covidence, duplicates were removed. Dual screening and data collection were performed independently by two reviewers per article (G.R. and L.J.). Conflicts were resolved by a third reviewer (K.A. or M.W.) for the final inclusion decision. Thereafter, all data was cross-checked. Continuous variables were imported as mean with standard deviation, categorical variables were imported as number of events and total. For missing or inconclusive data, the authors were contacted for clarification or additional data.

Risk of bias and certainty of evidence assessment

For the quality assessment of randomized controlled trials, the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool was used21. Two independent reviewers (G.R. and L.J.) judged the risk of bias using this tool. Conflicts were resolved with a third independent reviewer (M.W.). No automated tools were used.

Grading of the quality of evidence was performed using the Cochrane adapted GRADE approach by two reviewers (G.R. and M.W.), which places outcomes in one of four levels of certainty of evidence; high, moderate, low and very low23.

Calculation and statistical methods

Studies comparing an IAP of lower than 10 versus 10 mmHg or higher were included (Table 1). Data from studies with more than one group in one of these study arms were combined in Review Manager (version 5.3, The Cochrane Collaboration) as instructed by the Cochrane handbook21. For example, an included study with three groups randomized in IAP of 8, 12, or 16 mmHg. The data of the last two groups were combined for use in the 10 mmHg and higher study arm of this meta-analysis. Missing data were calculated according to Cochrane guidelines where possible.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| IAP (mmHg) | Number of patients | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| References | Low | Standard | Deep NMB | Total number of patients | Low | Standard | Type of procedure | Poor qualitya |

| Aditianingsih et al. 24 | 8 | 12 | No | 44 | 22 | 22 | LDN | |

| Akkoc et al. 25 | 10/12/14 | Unknown | 76 | 24/25/27 | UL | Yes | ||

| Albers et al. 26 | 8 | 12 | Yesb | 178 | 89 | 89 | LC | |

| Ali et al. 27 | 10/>10 | Unknown | 160 | 80/80 | LChol | Yes | ||

| Anwaar et al. 28 | 7–10 | 12–16 | Unknown | 100 | 50 | 50 | LChol | Yes |

| Aydin et al. 29 | 8 | 12 | Unknown | 60 | 30 | 30 | LChol | |

| Barczynski et al. 30 | 7 | 12 | Unknown | 148 | 74 | 74 | LChol | |

| Barrio et al. 31 | 8 | 12 | Yesc | 90 | 60 | 30 | LChol | |

| Basgul et al. 32 | 10/14–15 | Unknown | 22 | 11 | 11 | LChol | Yes | |

| Bhattacharjee et al. 33 | 9–10 | 14 | Unknown | 80 | 40 | 40 | LChol | |

| Bogani et al. 34 | 8 | 12 | Unknown | 42 | 20 | 22 | LH | |

| Budhiraja et al. 35 | 7 | 12 | Unknown | 100 | 50 | 50 | LChol | Yes |

| Cai et al. 36 | 10/12/15 | Unknown | 66 | 22/22/22 | LC | |||

| Celarier et al. 37 | 7 | 12 | Yesd | 127 | 62 | 65 | LC | |

| Celik et al. 38 | 8 | 12/14 | Unknown | 60 | 20 | 20/20 | LChol | |

| Chang et al. 39 | 6–8/9–11 | 12–14 | Unknown | 150 | 50/50 | 50 | LChol | |

| Chok et al. 40 | 7 | 12 | Unknown | 40 | 20 | 20 | LChol | |

| de’Angelis et al. 41 | 8 | 12 | Unknown | 161 | 35 | 126 | LChol | Yes |

| Dexter et al. 42 | 7 | 15 | Unknown | 20 | 10 | 10 | LChol | Yes |

| Diaz-Cambronero et al. 43 | 8 | 12 | Yesb | 166 | 85 | 81 | LC | |

| Doğan et al. 44 | 7 | 10/13 | Unknown | 90 | 30 | 30/30 | LChol | |

| Donmez et al. 45 | 10/14 | Unknown | 50 | 25/25 | LChol | |||

| Ekici et al. 46 | 7 | 15 | Unknown | 52 | 20 | 32 | LChol | |

| Eryilmaz et al. 47 | 10/14 | Unknown | 43 | 20/23 | LChol | |||

| Esmat et al. 48 | 10/14 | Unknown | 71 | 34/37 | LChol | Yes | ||

| Gin et al. 49 | 8 | 12 | No | 100 | 51 | 49 | LChol | |

| Goel et al. 50 | 7–10 | 12–14 | Unknown | 60 | 30 | 30 | LChol | Yes |

| Gupta et al. 51 | 8 | 14 | Unknown | 101 | 50 | 51 | LChol | |

| Hasukić et al. 52 | 7 | 14 | Unknown | 50 | 25 | 25 | LChol | |

| Ibraheim et al. 53 | 6–8 | 12–14 | No | 20 | 10 | 10 | LChol | Yes |

| Joshipura et al. 54 | 8 | 12 | Unknown | 26 | 14 | 12 | LChol | |

| Kandil et al. 55 | 8 | 10/12/14 | Unknown | 100 | 25 | 25/25/25 | LChol | Yes |

| Kanwer et al. 56 | 7–10 | 12–14 | Unknown | 60 | 30 | 30 | LChol | Yes |

| Karagulle et al. 57 | 8 | 12/15 | No | 45 | 15 | 15/15 | LChol | Yes |

| Kendir et al. 58 | 10/14 | Unknown | 40 | 20/20 | LChol | Yes | ||

| Khan et al. 59 | 8 | 14 | Unknown | 214 | 107 | 107 | LChol | |

| Kim et al. 60 | 8 | 13 | No | 46 | 23 | 23 | GL | |

| Kim et al. 61 | 8 | 12 | Yesb | 74 | 37 | 37 | GL | |

| Koc et al. 62 | 10/15 | Unknown | 50 | 25/25 | LChol | |||

| Ko-Iam et al. 63 | 7 | 14 | Unknown | 120 | 60 | 60 | LChol | |

| Kundu et al. 64 | 8 | 10/12/15 | Unknown | 360 | 62 | 102/123/73 | GL | |

| Luo et al. 65 | 10/15 | Unknown | 102 | 51/51 | RL | Yes | ||

| Madsen et al. 66 | 8 | 12 | Yese | 28 | 14 | 14 | GL | |

| Madsen et al. 67 | 8 | 12 | Yesb | 99 | 49 | 50 | LH | |

| Madsen et al. 68 | 8 | 12 | Yesb | 110 | 55 | 55 | LH | |

| Marton Filho et al. 69 | 6–8 | 10–12 | Yesd | 64 | 31 | 33 | LChol | |

| Matsuzaki et al. 70 | 8 | 12 | Unknown | 68 | 32 | 36 | LH | Yes |

| Matsuzaki et al. 71 | 8 | 12 | No | 82 | 41 | 41 | LH | |

| Mohammadzade et al. 72 | 7–10 | 12–14 | Unknown | 60 | 30 | 30 | LChol | Yes |

| Moro et al. 73 | 10/14 | Yesd | 80 | 40/40 | LChol | |||

| Murtaza et al. 74 | 8 | 12 | Unknown | 80 | 40 | 40 | LChol | Yes |

| Nasajiyan et al. 75 | 7–9 | 14–15 | Unknown | 50 | 25 | 25 | LChol | |

| Nematihonar et al. 76 | 6–8 | 12–14 | Unknown | 202 | 101 | 101 | LChol | Yes |

| Neogi et al. 77 | 7 | 14 | Unknown | 80 | 32 | 48 | LChol | |

| Nuna et al. 78 | 8–10 | 12–14 | Unknown | 50 | 25 | 25 | LChol | Yes |

| O et al. 79 | 7/9 | 12 | No | 54 | 20/21 | 13 | LChol | Yes |

| Özdemir-van Brunschot et al. 80 | 6 | 12 | Yesd | 63 | 33 | 30 | LDN | |

| Perrakis et al. 81 | 8 | 15 | Unknown | 40 | 20 | 20 | LChol | |

| Pulle et al. 82 | 8–10 | 13–15 | Unknown | 194 | 94 | 100 | LChol | |

| Radosa et al. 83 | 8 | 15 | Unknown | 178 | 91 | 87 | LH | |

| Rehman et al. 84 | 7 | 14 | Unknown | 60 | 30 | 30 | LChol | Yes |

| Rohloff et al. 85 | 8 | 12 | Unknown | 201 | 96 | 105 | RALP | |

| Rosenberg et al. 86 | 8 | 12 | Yesf | 127 | 60 | 67 | LChol | |

| Sandhu et al. 87 | 7 | 14 | Unknown | 140 | 70 | 70 | LChol | Yes |

| Sandoval-Jiménez et al. 88 | 7 | 12–15 | Unknown | 68 | 34 | 34 | LChol | |

| Sarli et al. 89 | 9 | 13 | Unknown | 90 | 46 | 44 | LChol | |

| Sattar et al. 90 | <12/12–16 | Unknown | 180 | 90 | 90 | LChol | Yes | |

| Schietroma et al. 91 | 6–8 | 12–14 | Unknown | 68 | 33 | 35 | LNF | Yes |

| Schietroma et al. 92 | 6–8 | 12–14 | Unknown | 51 | 25 | 26 | LA | |

| Sefr et al. 93 | 10/14 | Unknown | 32 | 10/22 | LChol | |||

| Sharma et al. 94 | 8 | 14 | Unknown | 50 | 25 | 25 | LChol | |

| Shoar et al. 95 | 8 | 12 | Unknown | 50 | 25 | 25 | LChol | |

| Singla et al. 96 | 7–8 | 12–14 | No | 100 | 50 | 50 | LChol | |

| Song et al. 97 | 10/11–12/13–14/15–16 | Unknown | 118 | 35/31 /28/24 | GL | Yes | ||

| Sood et al. 98 | 8–10 | 15 | Yesd | 9 | 5 | 4 | LA | |

| Sroussi et al. 99 | 7 | 15 | Unknown | 60 | 30 | 30 | GL | |

| Topal et al. 100 | 10/13/16 | Unknown | 60 | 20/20/20 | LChol | |||

| Topçu et al. 101 | 8 | 12/15 | Unknown | 150 | 54 | 48/48 | GL | |

| Torres et al. 102 | 6–8 | 12–14 | Unknown | 40 | 20 | 20 | LChol | Yes |

| Vijayaraghavan et al. 103 | 8 | 12 | No | 43 | 22 | 21 | LChol | |

| Wallace et al. 104 | 7.5 | 15 | Unknown | 40 | 20 | 20 | LChol | |

| Warlé et al. 105 | 7–9 | 12–16 | No | 20 | 10 | 10 | LDN | |

| Xiao et al. 106 | 7–9 | 11–13 | Unknown | 96 | 48 | 48 | LChol | Yes |

| Yasir et al. 107 | 8 | 14 | Unknown | 100 | 50 | 50 | LChol | Yes |

| Zaman et al. 108 | 7–8 | 12–14 | Unknown | 50 | 25 | 25 | LChol | Yes |

GL, gynecological laparoscopy; IAP, intra-abdominal pressure; LA, laparoscopic adrenalectomy; LC, laparoscopic colorectal surgery; LChol, laparoscopic cholecystectomy; LDN, laparoscopic donor nephrectomy; LH, (mini-) laparoscopic hysterectomy; LNF, laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication; NMB, neuromuscular block; RALP, robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy; RL, retroperitoneal laparoscopic surgery; UL, urinary tract laparoscopy.

Assessed according to the Cochrane risk of bias Tool; three or more bias items scored ‘unclear bias’ or ‘high risk’.

Deep NMB with low IAP and moderate NMB with standard IAP.

Deep and moderate NMB in low group.

Deep NMB in both groups.

Deep NMB and no NMB in both groups.

Deep and moderate in both groups.

Meta-analysis was performed for all outcomes where sufficient data were available. We reported risk ratio (RR) and mean difference (MD) for dichotomous and continuous outcomes, respectively. The presence and extent of heterogeneity was measured by χ2 and I 2 calculated by Review Manager. Given the expected heterogeneity between the studies, a random-effects model was used for all analyses.

Sensitivity analyses were performed for (1) exclusion of all poor quality studies (a study was classified as ‘poor quality’ when three or more risk of bias items scored ‘unclear bias’ or ‘high risk bias’), (2) exclusion of laparoscopic cholecystectomy to assess the effects for longer and/or more complex procedures, (3) only studies where deep NMB was used to facilitate the use of low IAP, and (4) with an IAP of 10 mmHg categorized as low pressure instead of standard pressure, as the precise definition of low pneumoperitoneum pressure is lacking.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

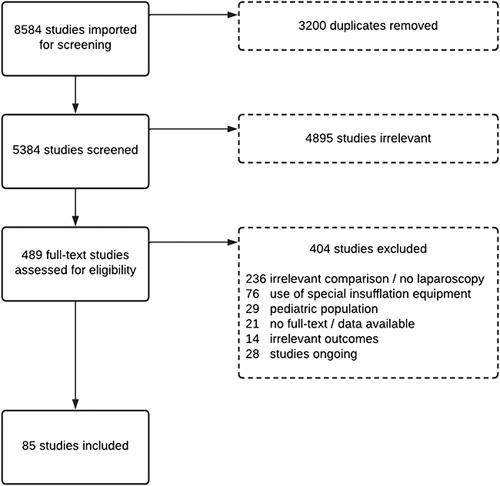

Database’s search is depicted in the PRISMA flowchart (Fig. 1). A total of 8584 references were found and imported in Covidence and 3200 duplicates were removed. After review and screening 489 studies where selected for full text review. Finally, 85 studies were included in the analysis. Study characteristics of the included studies24–108 are presented in Table 1. There are thirty poor quality studies according to the risk of bias assessment25–28,32,35,41,42,48,50,53,55–58,65,70,72,74,76,78,79,84,87,90,91,97,102,106–108.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

Main outcomes

Despite careful evaluation there were only available data for perioperative complications, resource use and short-term recovery after surgery. The main outcomes were postoperative complications (in hospital and within 30 days after surgery), postoperative pain (up to 72 h postoperative), PONV, and length of hospital stay. There was no available data for three domains: mortality/survival, longer term recovery after surgery, and overall success/failure of surgery.

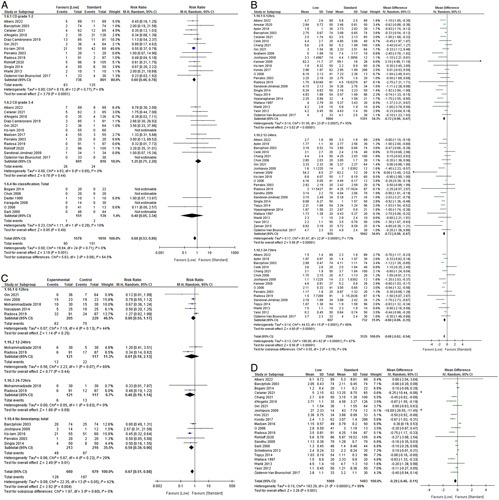

Table 2A presents the summary of findings for the StEP-COMPAC core outcomes, starting with the main outcomes of this review. At low IAP (<10 mmHg), patients developed significantly less minor postoperative complications (RR=0.60, 95% CI: 0.46–0.78, P=0.001). This significant difference was not present for grade 3 and 4 complications, which are considered major complications according to the StEP-COMPAC criteria. Postoperative pain was significantly lower at low IAP (MD=−0.68, 95% CI: −0.82 to 0.54, P<0.00001). PONV were significantly lower for low IAP over all time points combined (RR=0.67, 95% CI: 0.51–0.88, P 0.004). Length of hospital stay (in days) was significantly shorter with low IAP (MD=−0.29, 95% CI: −0.46 to −0.11; P<0.001). The forest plots of postoperative complications, length of hospital stay, postoperative pain, and PONV are presented in Figure 2. For the remaining StEP-COMPAC core outcomes, insufficient data were available for meta-analysis.

Table 2.

Summary of findings table

| Patients | Individuals undergoing laparoscopic surgery | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Low intra-abdominal pressure (<10 mmHg) | ||||||

| Comparison | Standard intra-abdominal pressure (≥10 mmHg) | ||||||

| Outcome | Number of participants (studies) | Relative effects (95% CI) | P | I 2 (%) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| 2A: Main outcomes20 | |||||||

| Mortality/survival | |||||||

| Overall mortality | No data | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Long-term survival | No data | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Perioperative complications | |||||||

| (Major) Postoperative complications | |||||||

| CD grade 1–2 | 1597 (13) | RR=0.60 (0.46–0.78) | 0.0001 | 0 | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High |

||

| CD grade 3–4 | 1507 (12) | RR=1.25 (0.71–2.20) | 0.44 | 0 | |||

| No classification | 290 (6) | RR=0.40 (0.05–3.34) | 0.40 | 10 | |||

| Total | 3394 (21) | RR=0.68 (0.53–0.86) | 0.001 | 0 | |||

| Complications with permanent disability | No data | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Resource use | |||||||

| Hospital stay | 2562 (22) | MD=−0.29 (−0.46 to −0.11) | 0.001 | 89 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate Due to inconsistency |

Substantial heterogeneity | |

| Hospital readmission | No data | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Short-term recovery after surgery | |||||||

| Postoperative Pain (NRS) | |||||||

| 0–12 h | 2355 (24) | MD=−0.72 (−0.96 to −0.47) | <0.00001 | 55 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate Due to inconsistency |

Substantial heterogeneity | |

| 12–24 h | 1977 (23) | MD=−0.72 (−0.98 to −0.47) | <0.00001 | 73 | |||

| 24–72 h | 1389 (16) | MD=−0.60 (−0.86 to −0.35) | <0.00001 | 66 | |||

| Total | 5721 (27) | MD=−0.68 (−0.82 to −0.54) | <0.00001 | 67 | |||

| PONV (yes/no) | |||||||

| 0–12 h | 434 (5) | RR=0.80 (0.55–1.17) | 0.25 | 44 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate Due to inconsistency |

Moderate heterogeneity | |

| 12–24 h | 238 (2) | RR=0.61 (0.18–2.13) | 0.44 | 69 | |||

| 24–72 h | 238 (2) | RR=0.46 (0.19–1.14) | 0.09 | 0 | |||

| No timestamp | 429 (5) | RR=0.59 (0.39–0.90) | 0.01 | 29 | |||

| Total | 1339 (10) | RR=0.67 (0.51–0.88) | 0.004 | 42 | |||

| Psychological wellbeing | No data | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Discharge destination | No data | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Longer term recovery after surgery | |||||||

| Overall health-related quality of life | No data | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Overall success/failure of surgery | |||||||

| Patient satisfaction | No data | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| 2B: Safety outcomes surgical procedural feasibility and success | |||||||

| Intraoperative complications | 1661 (16) | RR=1.15 (0.77–1.73) | 0.50 | 0 | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High |

||

| Quality of the surgical fielda | 896 (10) | MD=−0.63 (−1.14 to −0.13) | 0.01 | 97 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate Due to inconsistency |

Considerable heterogeneity | |

| Conversion | |||||||

| To laparotomy | 1718 (20) | RR=1.36 (0.55–3.33) | 0.50 | 0 | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High |

||

| To higher pressure | 1411 (16) | RR=4.71 (2.88–7.69) | <0.00001 | 0 | |||

| Duration of surgery (min) | 5047 (55) | MD=1.75 (0.15–3.64) | 0.07 | 89 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate Due to inconsistency |

Substantial heterogeneity | |

| Blood loss (ml) | 861 (8) | MD=16.30 (−9.40 to 41.99) | 0.21 | 92 | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate Due to inconsistency |

Considerable heterogeneity | |

CD, Clavien–Dindo; MD, mean difference; NA, not available; NRS, Numerical Rating Scale; PONV, postoperative nausea and vomiting; RR, risk ratio.

Scored on the Leiden Surgical Rating Scale: 5=excellent, 4=good, 3=improvement is welcome, 2=bad, 1=very.

Figure 2.

Forest plots of main outcomes20. (A) Postoperative complications by Clavien–Dindo grade. (B) Postoperative pain. (C) Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV). (D) Length of hospital stay.

For the secondary safety outcomes (reported in Table 2B), there was a statistically significant difference for low IAP regarding quality of the surgical field (better for standard pressure). Intraoperative complications, conversion to laparotomy, operation time and blood loss showed no statistically significant differences. The summary of findings table of all other outcomes are presented in the Supplementary (Supplementary Table 3, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A270), including the forest plots (Supplementary Fig. 1, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A270).

The funnel plots of all outcomes are presented in the Supplementary Figure 2 (Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A270) and do not indicate publication bias for the main and secondary outcomes. Heterogeneity between studies was present as displayed in Table 2. Postoperative complications had a low I 2, PONV showed a moderate heterogeneity on average by mostly staying below the margin of 60%. Postoperative pain scores and hospital stay had substantial heterogeneity with I 2 above 60%.

Sensitivity analyses did not indicate a significant influence of poor quality studies or studies investigating laparoscopic cholecystectomy (Supplementary Table 2, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A270). Differences in favor of low IAP defined as less than 10 mmHg or lower were no longer significant for all four main outcomes when 10 mmHg was categorized as low pressure. The number of studies explicitly reporting the use of deep NMB to facilitate low pressure was too small to perform meaningful sensitivity analyses.

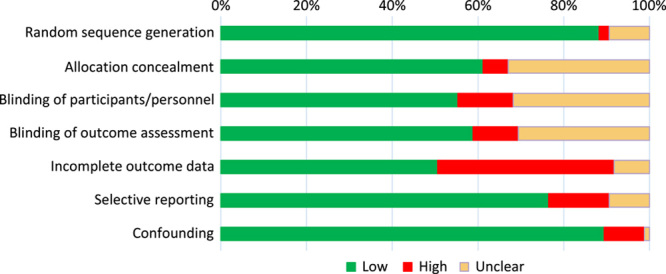

Risk of bias and certainty of evidence

The risk of bias assessment presented the highest risk of bias in incomplete outcome data, although with the high risk and unclear categories taken together, this occurred in less than 50% of all studies (Fig. 3). Publication bias was limited based on the funnel plots (Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A270). The risk of bias per study is presented in detail in Table 1 of the Supplementary (Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/JS9/A270).

Figure 3.

Risk of bias summary: judgement of each risk of bias criterion across all included studies.

Table 2 shows the certainty of evidence per outcome, including reasons for downgrading. This was mostly based on heterogeneity between studies, which is reflected by the diversity of surgery types included in this meta-analysis. Because of a limited number of studies, almost all biochemical outcomes were considered imprecise.

Discussion

The main results of this meta-analysis show that the use of low IAP significantly reduces the incidence of mild to moderate postoperative complications (Clavien–Dindo grade 1–2); reduces 24–72 h postoperative pain scores; reduces PONV scores; and reduces the mean length of hospital stay. The overall certainty of evidence according to the GRADE approach was moderate to high. Sensitivity analyses indicated that the mean differences were similar in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy as compared with other laparoscopic procedures. This indicates that the benefits of lower IAP during laparoscopic surgery are not procedure-bound.

Over the last years, a relatively large number of randomized clinical trials had studied the influence of low IAP during laparoscopic surgeries. Our quality assessment revealed that a vast majority of these trials (55/85) displayed a low risk of bias. Our findings are in line with a previous meta-analysis from our group including 33 randomized controlled trials mainly studying patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy16. In this previous study we demonstrated that the use of low IAP reduced pain scores 24–48 h after surgery as compared with standard IAP. Up until the meta-analysis of Gurusamy and colleagues on low versus standard IAP in laparoscopic cholecystectomy patients in 2014, there was a lack of evidence and no meaningful conclusions could be drawn regarding efficacy outcomes due to high risk of bias of the studies available. Because the number of studies published on low versus standard pressure laparoscopy with low risk of bias increased steadily, a reliable meta-analysis could be performed for postoperative pain intensity and shoulder pain incidence as efficacy outcome measures in 201516. The number of studies further increased after 2015, and the reporting of other clinically relevant outcomes improved which allowed for an update of our previous meta-analysis. There were no studies reporting on mortality, and longer term recovery after surgery. Nevertheless, sufficient data were available with regard to four important outcome measures in perioperative medicine, as defined by the StEP-COMPAC consensus group (i.e. postoperative complications, postoperative pain, PONV and length of hospital stay). In the hierarchy of outcome measures, mortality, and severe postoperative complications are considered more important for guideline decision-makers than minor postoperative complications, postoperative pain, and PONV. Nevertheless, an intervention which improves short-term recovery only, may still be important to adopt when considered safe.

In summary, the current meta-analysis provides high certainty of evidence indicating that the use of low pressure does not increase the incidence of intraoperative complications, while reducing the incidence of Clavien–Dindo grade 1–2 postoperative complications among other benefits in clinical and patient-centered outcomes. In our view, this strongly supports the safety of using low IAP. The use of deep NMB could in theory facilitate the use of lower IAP during laparoscopic surgery, by increasing workspace and reducing muscle contractions. A meta-analysis by Bruintjes et al. 109 confirmed that deep NMB improved surgical conditions rated by surgeons during laparoscopic surgery as compared with moderate NMB. The number of studies reporting on deep NMB to facilitate low pneumoperitoneum pressure was too small to allow for a meaningful subgroup analysis regarding relevant efficacy endpoints. Therefore, further studies are warranted to establish the optimal depth of muscle relaxation for low pressure during laparoscopy. Next to adequate muscle relaxation, prestretching of the abdominal wall musculature with a short period of standard IAP (12–15 mmHg) during trocar introduction, could also contribute to increased working space during subsequent low IAP26,43. Although, poorly described in a vast majority of studies included in this meta-analysis, several studies used standard insufflation pressures during trocar insertion to create some prestretching of the abdominal wall. It seems unlikely that a short period of prestretching with standard IAP compromises the clinical benefits of low IAP, but further studies are required to confirm this.

This meta-analysis provides high certainty evidence for the safety of low IAP during laparoscopy as reflected by a similar incidence of intraoperative complications. The use of low pressure (regardless of NMB) did modestly reduce the quality of the surgical field with 0.6 points on a five-point scale. But the clinical benefits of low IAP are reflected by a significant, but modest reduction in postoperative pain, PONV, and length of hospital stay. These modest benefits combined with a reduced incidence of postoperative complications (mild to moderate, Clavien–Dindo grade 1–2 complications) justify a moderate to strong recommendation in favor of using low IAP (<10 mmHg) during laparoscopic surgery. It is important to stress that surgeons should increase the IAP when surgical conditions are inadequate according to their judgement. Although, a higher IAP does not always improve the surgical conditions probably due to patient bound factors. Deep NMB could enhance surgical conditions and should be considered when using low IAP109.

Sensitivity analyses in which patients allocated to an insufflation pressure of 10 mmHg were added to the low pressure group, failed to demonstrate a significant beneficial impact of low IAP regarding the main outcomes. In our view, this finding supports the main hypothesis in a vast majority of the existing studies in which clinical benefits were expected by using a pressure of less than 10 mmHg or lower, instead of 10 mmHg or lower. Therefore, laparoscopic surgeons aiming for better recovery of their patients with a lower risk of mild complications should use an insufflation pressure below 10 mmHg, but – to ensure safety – low IAP should only be used when the quality of the surgical field is adequate according to their judgement.

The main strength of this meta-analysis is its solid approach and methods in line with the handbook of the Cochrane collaboration. The high number of studies available allowed us to perform meaningful analyses for a wide range of outcome measures. Although moderate to substantial heterogeneity was present for most of the outcomes, the certainty of evidence for these outcomes was moderate to high. Ideally, subgroup analyses would have been performed for each type of laparoscopic procedure, since the ease to work with low IAP could differ between surgery taking place high abdominal or in small pelvis. But – except for laparoscopic cholecystectomy – the available number of studies was too small. Nevertheless, according to Pascal’s law carbon dioxide pressure in the abdominal cavity equally expands in all directions, and therefore it is reasonable to assume that the physiological impact of a pneumoperitoneum does not differ significantly between different types of procedures. Despite this, low IAP may be more difficult to use in certain types of procedures depending on the complexity of the procedure, positioning, and patient-related factors (i.e. obesity, previous surgery). Also, the use of low IAP might, at least in theory, be easier in robot-assisted procedures with greater ranges of motion and more precision in narrow working spaces.

In our view it may not be safe to use low IAP for blind trocar introduction, through the umbilical incision, after insufflation with a Verres needle. Also, during trocar introduction under camera vision it may be better to use standard insufflation pressures, to minimize the risk of trocar injuries, but also to induce a certain degree of prestretching of the abdominal wall muscles. Some reports demonstrate that prestretching facilitates the use of low IAP after trocar introduction110,111. Therefore, our recommendation to use low IAP does not refer to the initial trocar introduction phase. To guarantee optimal safety, and to create some prestretching of the abdominal wall, an insufflation pressure of 12–15 mmHg during trocar introduction would, at least in theory, be ideal. Once the initial trocars have been introduced, the IAP can be reduced below 10 mmHg. However, if surgical conditions remain poor according to the surgeon’s judgement after optimization of positioning and neuromuscular blockade, it is not safe to continue with low IAP.

Limitations of this study are mainly related to the relatively high number of poor quality studies, and the high incidence of poorly reported outcome measures. Nevertheless, due to the high number of studies available we could perform a sensitivity analysis in which poor quality studies were excluded. The results regarding the main outcomes were not influenced by the presence of poor quality studies. Finally, a relatively high number of comparisons were carried out in this meta-analysis without correction for multiplicity. However, this approach is in line with the Cochrane handbook which explicitly does not recommend adjustments for multiple comparisons.

In conclusion, regarding the core outcomes in perioperative medicine, the use of low IAP leads to a lower incidence of mild postoperative complications, lower pain scores and PONV, and a slightly reduced length of hospital stay. Also, the use of low IAP in a wide range of laparoscopic procedures is associated with a slightly reduced quality of the surgical field, however high certainty evidence does not indicate an increased risk of intraoperative complications or conversion to laparotomy.

Therefore, our data support a moderate to strong recommendation (1a level of evidence) in favor of the use of low IAP during laparoscopic surgery. It is important to note that surgeons should be aware that IAP should be increased when the quality of the surgical field is inadequate to ensure safety.

Ethical approval

NA.

Sources of funding

There was no financial or nonfinancial support used or related to the process or writing of this manuscript.

Author contribution

G.T.J.A.R.-B., E.v.H., and M.C.W. were involved in the study design. G.T.J.A.R.-B., K.I.A., E.v.H., and L.M.C.J. collected data. Interpretation of the data was done by G.T.J.A.R.-B., L.M.C.J., and M.C.W. with substantial input of O.D.-C., G.M., C.R., G.-J.S., and C.K. In the writing process, G.T.J.A.R.-B., M.C.W. were essential. Substantial input in the writing process and revisions were done by all authors.

Conflicts of interest disclosure

M.C.W. and O.D.-C. received grants from Merck Sharp & Dohme for investigator-initiated studies. The remaining authors declare that they have no financial conflict of interest with regard to the content of this report.

Research registration unique identifying number (UIN)

Name of the registry: Prospero.

Unique Identifying number or registration ID: CRD42020167327.

Hyperlink to your specific registration (must be publicly accessible and will be checked): https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=167327.

Guarantors

Michiel C. Warlé and Gabby T.J.A. Reijnders-Boerboom.

Data availability statement

All extracted data can be made available upon reasonable request by contacting the corresponding author. Data collection forms and analytic code were based on the PRISMA guidelines and can also be shared upon reasonable request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website, www.journal-surgery.net.

Published online 10 April 2023

Contributor Information

Gabby T.J.A. Reijnders-Boerboom, Email: gabby.reijnders-boerboom@radboudumc.nl.

Kim I. Albers, Email: kim.albers@radboudumc.nl.

Lotte M.C. Jacobs, Email: lotte.jacobs@radboudumc.nl.

Esmee van Helden, Email: Esmee.vanhelden@radboudumc.nl.

Camiel Rosman, Email: Camiel.rosman@radboudumc.nl.

Oscar Díaz-Cambronero, Email: oscardiazcambronero@gmail.com.

Guido Mazzinari, Email: gmazzinari@gmail.com.

Gert-Jan Scheffer, Email: gertjan.scheffer@radboudumc.nl.

Christiaan Keijzer, Email: christiaan.keijzer@radboudumc.nl.

Michiel C. Warlé, Email: michiel.warle@radboudumc.nl.

References

- 1. Neudecker J, Sauerland S, Neugebauer E, et al. The European Association for Endoscopic Surgery clinical practice guideline on the pneumoperitoneum for laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc 2002;16:1121–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Scott MJ, Baldini G, Fearon KC, et al. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) for gastrointestinal surgery, part 1: pathophysiological considerations. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2015;59:1212–1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Feldheiser A, Aziz O, Baldini G, et al. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) for gastrointestinal surgery, part 2: consensus statement for anaesthesia practice. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2016;60:289–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gustafsson UO, Scott MJ, Hubner M, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in elective colorectal surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS(®)) Society Recommendations: 2018. World J Surg 2019;43:659–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nelson G, Bakkum-Gamez J, Kalogera E, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in gynecologic/oncology: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society recommendations-2019 update. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2019;29:651–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thorell A, MacCormick AD, Awad S, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in bariatric surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society Recommendations. World J Surg 2016;40:2065–2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mortensen K, Nilsson M, Slim K, et al. Consensus guidelines for enhanced recovery after gastrectomy: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society recommendations. Br J Surg 2014;101:1209–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Melloul E, Hübner M, Scott M, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care for liver surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society Recommendations. World J Surg 2016;40:2425–2440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Low DE, Allum W, De Manzoni G, et al. Guidelines for perioperative care in esophagectomy: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS(®)) Society Recommendations. World J Surg 2019;43:299–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Melloul E, Lassen K, Roulin D, et al. Guidelines for Perioperative Care for Pancreatoduodenectomy: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Recommendations 2019. World J Surg 2020;44:2056–2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hypólito OHM, Azevedo JLMC, de Lima Alvarenga FMS, et al. Creation of pneumoperitoneum: noninvasive monitoring of clinical effects of elevated intraperitoneal pressure for the insertion of the first trocar. Surg Endosc 2010;24:1663–1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Solass W, Horvath P, Struller F, et al. Functional vascular anatomy of the peritoneum in health and disease. Pleura Peritoneum 2016;1:145–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kirkpatrick AW, Roberts DJ, De Waele J, et al. Intra-abdominal hypertension and the abdominal compartment syndrome: updated consensus definitions and clinical practice guidelines from the World Society of the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. Intensive Care Med 2013;39:1190–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Junghans T, Böhm B, Gründel K, et al. Does pneumoperitoneum with different gases, body positions, and intraperitoneal pressures influence renal and hepatic blood flow? Surgery 1997;121:206–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sodha S, Nazarian S, Adshead JM, et al. Effect of pneumoperitoneum on renal function and physiology in patients undergoing robotic renal surgery. Curr Urol 2016;9:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Özdemir-van Brunschot DM, van Laarhoven KC, Scheffer GJ, et al. What is the evidence for the use of low-pressure pneumoperitoneum? A systematic review. Surg Endosc 2016;30:2049–2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Raval AD, Deshpande S, Koufopoulou M, et al. The impact of intra-abdominal pressure on perioperative outcomes in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Surg Endosc 2020;34:2878–2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. van Boekel RLM, Warlé MC, Nielen RGC, et al. Relationship between postoperative pain and overall 30-day complications in a broad surgical population: an observational study. Ann Surg 2019;269:856–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Albers KI, van Helden EV, Dahan A, et al. Early postoperative pain after laparoscopic donor nephrectomy predicts 30-day postoperative infectious complications: a pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pain 2020;161:1565–1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Boney O, Moonesinghe SR, Myles PS, et al. Core Outcome Measures for Perioperative and Anaesthetic Care (COMPAC): a modified Delphi process to develop a core outcome set for trials in perioperative care and anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth 2022;128:174–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Higgins JP, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. John Wiley & Sons; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, et al. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014;14:135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schünemann HJ, Higgins JP, Vist GE, et al. Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. Completing ‘Summary of findings’ tables and grading the certainty of the evidence. Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. 2019:375–402. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Aditianingsih D, Mochtar CA, Lydia A, et al. Effects of low versus standard pressure pneumoperitoneum on renal syndecan-1 shedding and VEGF receptor-2 expression in living-donor nephrectomy: a randomized controlled study. BMC Anesthesiol 2020;20:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Akkoc A, Topaktas R, Aydin C, et al. Which intraperitoneal insufflation pressure should be used for less postoperative pain in transperitoneal laparoscopic urologic surgeries? Int Braz J Urol 2017;43:518–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Albers KI, Polat F, Helder L, et al. Quality of recovery and innate immune homeostasis in patients undergoing low-pressure versus standard-pressure pneumoperitoneum during laparoscopic colorectal surgery (RECOVER): a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 2022;276:e664–e673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ali IS, Shah MF, Faraz A, et al. Effect of intra-abdominal pressure on post-laparoscopic cholecystectomy shoulder tip pain: a randomized control trial. J Pak Med Assoc 2016;66(suppl 3):S45–S49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Anwaar MH, Anwer MF, Asif M, et al. Comparison of frequency of shoulder tip pain in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy with low and standard pressure pneumoperitonium. Pak J Med Health Sci 2019;14:814–815. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Aydin OU, Soylu L. Impact of low-pressure pneumoperitoneum and local anesthetic combination on postoperative pain in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Eur Res J 2018;4:326–332. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Barczyński M, Herman RM. A prospective randomized trial on comparison of low-pressure (LP) and standard-pressure (SP) pneumoperitoneum for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc 2003;17:533–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Barrio J, Errando CL, García-Ramón J, et al. Influence of depth of neuromuscular blockade on surgical conditions during low-pressure pneumoperitoneum laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a randomized blinded study. J Clin Anesth 2017;42:26–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Basgul E, Bahadir B, Celiker V, et al. Effects of low and high intra-abdominal pressure on immune response in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Saudi Med J 2004;25:1888–1891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bhattacharjee HK, Jalaludeen A, Bansal V, et al. Impact of standard-pressure and low-pressure pneumoperitoneum on shoulder pain following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a randomised controlled trial. Surg Endosc 2017;31:1287–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bogani G, Uccella S, Cromi A, et al. Low vs standard pneumoperitoneum pressure during laparoscopic hysterectomy: prospective randomized trial. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2014;21:466–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Budhiraja S, Kumar S, Jain NP. Study of low pressure pneumoperitoneum in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. HPB 2011;13:225.21418127 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cai Z, Malbrain ML, Sun J, et al. Does elevated intra-abdominal pressure during laparoscopic colorectal surgery cause acute gastrointestinal injury? Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne 2015;10:161–169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Celarier S, Monziols S, Célérier B, et al. Low-pressure versus standard pressure laparoscopic colorectal surgery (PAROS trial): a phase III randomized controlled trial. Br J Surg 2021;108:998–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Celik AS, Frat N, Celebi F, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy and postoperative pain: is it affected by intra-abdominal pressure? Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2010;20:220–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chang W, Yoo T, Cho WT, et al. Comparing postoperative pain in various pressure pneumoperitoneum of laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a double-blind randomized controlled study. Ann Surg Treat Res 2021;100:276–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chok KS, Yuen WK, Lau H, et al. Prospective randomized trial on low-pressure versus standard-pressure pneumoperitoneum in outpatient laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2006;16:383–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. de’Angelis N, Abdalla S, Carra MC, et al. Low-impact laparoscopic cholecystectomy is associated with decreased postoperative morbidity in patients with sickle cell disease. Surg Endosc 2018;32:2300–2311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dexter SP, Vucevic M, Gibson J, et al. Hemodynamic consequences of high- and low-pressure capnoperitoneum during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc 1999;13:376–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Diaz-Cambronero O, Mazzinari G, Errando CL, et al. An individualised versus a conventional pneumoperitoneum pressure strategy during colorectal laparoscopic surgery: rationale and study protocol for a multicentre randomised clinical study. Trials 2019;20:190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Doğan U, Habibi M, Bülbüller N, et al. Effects of different intraabdominal pressure levels on oxidative stress markers in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Turk J Surg 2018;34:212–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Donmez T, Uzman S, Yildirim D, et al. Is there any effect of pneumoperitoneum pressure on coagulation and fibrinolysis during laparoscopic cholecystectomy? PeerJ 2016;4:e2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ekici Y, Bozbas H, Karakayali F, et al. Effect of different intra-abdominal pressure levels on QT dispersion in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc 2009;23:2543–2549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Eryilmaz HB, Memiş D, Sezer A, et al. The effects of different insufflation pressures on liver functions assessed with LiMON on patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. ScientificWorldJournal 2012;2012:172575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Esmat ME, Elsebae MM, Nasr MM, et al. Combined low pressure pneumoperitoneum and intraperitoneal infusion of normal saline for reducing shoulder tip pain following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. World J Surg 2006;30:1969–1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gin E, Lowen D, Tacey M, et al. Reduced laparoscopic intra-abdominal pressure during laparoscopic cholecystectomy and its effect on post-operative pain: a double-blinded randomised control trial. J Gastrointest Surg 2021;25:2806–2813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Goel A, Gupta S, Bhagat TS, et al. Comparative analysis of hemodynamic changes and shoulder tip pain under standard pressure versus low-pressure pneumoperitoneum in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Euroasian J Hepatogastroenterol 2019;9:5–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gupta R, Kaman L, Dahiya D, et al. Effects of varying intraperitoneal pressure on liver function tests during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2013;23:339–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hasukić S. Postoperative changes in liver function tests: randomized comparison of low- and high-pressure laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc 2005;19:1451–1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ibraheim OA, Samarkandi AH, Alshehry H, et al. Lactate and acid base changes during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Middle East J Anaesthesiol 2006;18:757–768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Joshipura VP, Haribhakti SP, Patel NR, et al. A prospective randomized, controlled study comparing low pressure versus high pressure pneumoperitoneum during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2009;19:234–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kandil TS, El Hefnawy E. Shoulder pain following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: factors affecting the incidence and severity. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2010;20:677–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kanwer DB, Kaman L, Nedounsejiane M, et al. Comparative study of low pressure versus standard pressure pneumoperitoneum in laparoscopic cholecystectomy – a randomised controlled trial. Trop Gastroenterol 2009;30:171–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Karagulle E, Turk E, Dogan R, et al. The effects of different abdominal pressures on pulmonary function test results in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2008;18:329–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kendir V. Evaluation of intraperitoneal CO2 insufflation, given in different pressures, on hemodynamic parameters by USCOM (Non-Invasive Ultrasonographic Cardiac Output Monitor) in laparoscopic cholecystectomy operations. Med J Bakirkoy 2018;14:176–182. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Khan F, Manzoor A, Jamal S. Low pressure pneumoperitonium laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a comparison of intra-operative hemodynamic stability and physiological changes with standard pressure pneumoperitonium laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Rawal Med J 2015;40:299–302. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kim DK, Cheong I, Lee GY, et al. Low pressure (8 mmHg) pneumoperitoneum does not reduce the incidence and severity of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) following gynecologic laparoscopy. Korean J Anesthesiol 2006;50:S36–S42. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kim JE, Min SK, Ha E, et al. Effects of deep neuromuscular block with low-pressure pneumoperitoneum on respiratory mechanics and biotrauma in a steep Trendelenburg position. Sci Rep 2021;11:1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Koc M, Ertan T, Tez M, et al. Randomized, prospective comparison of postoperative pain in low- versus high-pressure pneumoperitoneum. ANZ J Surg 2005;75:693–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ko-Iam W, Paiboonworachat S, Pongchairerks P, et al. Combination of etoricoxib and low-pressure pneumoperitoneum versus standard treatment for the management of pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc 2016;30:4800–4808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kundu S, Weiss C, Hertel H, et al. Association between intraabdominal pressure during gynaecologic laparoscopy and postoperative pain. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2017;295:1191–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Luo H-L, Cui M-J, Li Y-L. Influence of different pneumoperitoneum pressures on pulmonary shunt and pulmonary compliance in patients undergoing retroperitoneal laparoscopic surgery. World Chin J Digestol 2018;26:276–281. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Madsen MV, Gätke MR, Springborg HH, et al. Optimising abdominal space with deep neuromuscular blockade in gynaecologic laparoscopy – a randomised, blinded crossover study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2015;59:441–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Madsen MV, Istre O, Staehr-Rye AK, et al. Postoperative shoulder pain after laparoscopic hysterectomy with deep neuromuscular blockade and low-pressure pneumoperitoneum: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2016;33:341–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Madsen MV, Istre O, Springborg HH, et al. Deep neuromuscular blockade and low insufflation pressure during laparoscopic hysterectomy. Dan Med J 2017;64:A5364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Marton Filho MA, Alves RL, Nascimento PDJ, et al. Effects of pneumoperitoneum on kidney injury biomarkers: a randomized clinical trial. PLoS ONE 2021;16:e0247088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Matsuzaki S, Jardon K, Maleysson E, et al. Impact of intraperitoneal pressure of a CO2 pneumoperitoneum on the surgical peritoneal environment. Hum Reprod 2012;27:1613–1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Matsuzaki S, Vernis L, Bonnin M, et al. Effects of low intraperitoneal pressure and a warmed, humidified carbon dioxide gas in laparoscopic surgery: a randomized clinical trial. Sci Rep 2017;7:11287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Mohammadzade AR, Esmaili F. Comparing hemodynamic symptoms and the level of abdominal pain in high- versus low-pressure carbon dioxide in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Indian J Surg 2018;80:30–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Moro ET, Pinto PCC, Neto A, et al. Quality of recovery in patients under low- or standard-pressure pneumoperitoneum. A randomised controlled trial. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2021;65:1240–1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Murtaza R, Gaur M, Shishodia A. Comparative study of low pressure pneumoperitoneum versus standard pressure pneumoperitoneum in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Indian J Public Health Res Dev 2020;11:1091–1094. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Nasajiyan N, Javaherfourosh F, Ghomeishi A, et al. Comparison of low and standard pressure gas injection at abdominal cavity on postoperative nausea and vomiting in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Pak J Med Sci 2014;30:1083–1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Nematihonar B, Malekpour N, Hashemian M, et al. Effects of low pressure of laparoscopic cholecystectomy on arterial pressure of carbon dioxide and mean blood pressure. Int J Med Toxicol Forensic Med 2018;8:95–100. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Neogi P, Kumar P, Kumar S. Low-pressure pneumoperitoneum in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2020;30:30–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Nuna N, Singh S, Kumar A, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy at low pressure vs standard pressure pneumoperitoneum: a comparative study. J Cardiovasc Dis Res 2021;12:967–974. [Google Scholar]

- 79. JT O, Park DE, Chae KM. Postoperative pain differences between different insufflation pressures on laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Korean Surg Soc 2006;70:307–311. [Google Scholar]

- 80. Özdemir-van Brunschot DMD, Scheffer GJ, van der Jagt M, et al. Quality of recovery after low-pressure laparoscopic donor nephrectomy facilitated by deep neuromuscular blockade: a randomized controlled study. World J Surg 2017;41:2950–2958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Perrakis E, Vezakis A, Velimezis G, et al. Randomized comparison between different insufflation pressures for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2003;13:245–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Pulle MV, Dey A, Mittal T, et al. Insufflation pressure and its effect on shoulder tip pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy – a single-blinded, randomised study on 200 patients. Curr Med Res Pract 2019;9:98–101. [Google Scholar]

- 83. Radosa JC, Radosa MP, Schweitzer PA, et al. Impact of different intraoperative CO(2) pressure levels (8 and 15 mmHg) during laparoscopic hysterectomy performed due to benign uterine pathologies on postoperative pain and arterial pCO(2): a prospective randomised controlled clinical trial. BJOG 2019;126:1276–1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Rehman PM, Ahmad F, Anis SB. Comparison of low pressure versus high pressure laparoscopic cholecystectomy; a randomized controlled trial. Pak J Med Sci 2018;12:1516–1518. [Google Scholar]

- 85. Rohloff M, Peifer G, Shakuri-Rad J, et al. The impact of low pressure pneumoperitoneum in robotic assisted radical prostatectomy: a prospective, randomized, double blinded trial. World J Urol 2020;39:2469–2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Rosenberg J, Herring WJ, Blobner M, et al. Deep neuromuscular blockade improves laparoscopic surgical conditions: a randomized, controlled study. Adv Ther 2017;34:925–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Sandhu T, Yamada S, Ariyakachon V, et al. Low-pressure pneumoperitoneum versus standard pneumoperitoneum in laparoscopic cholecystectomy, a prospective randomized clinical trial. Surg Endosc 2009;23:1044–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Sandoval-Jiménez CH, Méndez-Sashida GJ, Cruz-Márquez-Rico LM, et al. Postoperative pain in patients undergoing elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy with low versus standard-pressure pneumoperitoneum. A randomized clinical trial. Rev Gastroenterol Mex 2009;74:314–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Sarli L, Costi R, Sansebastiano G, et al. Prospective randomized trial of low-pressure pneumoperitoneum for reduction of shoulder-tip pain following laparoscopy. Br J Surg 2000;87:1161–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Sattar Z, Ullah MK, Ahmad MS, et al. Outcome comparison in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy using low pressure and standard pressure pneumoperitoneum. Pak J Med Health Sci 2015;9:76–79. [Google Scholar]

- 91. Schietroma M, Carlei F, Cecilia EM, et al. A prospective randomized study of systemic inflammation and immune response after laparoscopic nissen fundoplication performed with standard and low-pressure pneumoperitoneum. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2013;23:189–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Schietroma M, Pessia B, Stifini D, et al. Effects of low and standard intra-abdominal pressure on systemic inflammation and immune response in laparoscopic adrenalectomy: a prospective randomised study. J Minim Access Surg 2016;12:109–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Sefr R, Puszkailer K, Jagos F. Randomized trial of different intraabdominal pressures and acid-base balance alterations during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc 2003;17:947–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Sharma A, Dahiya D, Kaman L, et al. Effect of various pneumoperitoneum pressures on femoral vein hemodynamics during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Updates Surg 2016;68:163–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Shoar S, Naderan M, Ebrahimpour H, et al. A prospective double-blinded randomized controlled trial comparing systemic stress response in Laparoascopic cholecystectomy between low-pressure and standard-pressure pneumoperitoneum. Int J Surg 2016;28:28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Singla S, Mittal G, Raghav, et al. Pain management after laparoscopic cholecystectomy-a randomized prospective trial of low pressure and standard pressure pneumoperitoneum. J Clin Diagn Res 2014;8:92–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Song G, Jiang Y, Liu Q, et al. CO2 pneumoperitoneum pressure: an important factor influenced ovarian function after laparoscopy. Ann Palliat Med 2021;10:9326–9327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Sood J, Jayaraman L, Kumra VP, et al. Laparoscopic approach to pheochromocytoma: is a lower intraabdominal pressure helpful? Anesth Analg 2006;102:637–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Sroussi J, Elies A, Rigouzzo A, et al. Low pressure gynecological laparoscopy (7 mmHg) with AirSeal(®) System versus a standard insufflation (15 mmHg): a pilot study in 60 patients. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod 2017;46:155–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Topal A, Celik JB, Tekin A, et al. The effects of 3 different intra-abdominal pressures on the thromboelastographic profile during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2011;21:434–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Topçu HO, Cavkaytar S, Kokanali K, et al. A prospective randomized trial of postoperative pain following different insufflation pressures during gynecologic laparoscopy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2014;182:81–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Torres K, Torres A, Staśkiewicz GJ, et al. A comparative study of angiogenic and cytokine responses after laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed with standard- and low-pressure pneumoperitoneum. Surg Endosc 2009;23:2117–2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Vijayaraghavan N, Sistla SC, Kundra P, et al. Comparison of standard-pressure and low-pressure pneumoperitoneum in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a double blinded randomized controlled study. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2014;24:127–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Wallace DH, Serpell MG, Baxter JN, et al. Randomized trial of different insufflation pressures for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg 1997;84:455–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Warlé MC, Berkers AW, Langenhuijsen JF, et al. Low-pressure pneumoperitoneum during laparoscopic donor nephrectomy to optimize live donors’ comfort. Clin Transplant 2013;27:E478–E483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Xiao Q-H, Yang L, Chen R-P, et al. Effect of pneumoperitoneum pressure on hemodynamic parameters in patients undergoing laparoscopic gallbladder excision. World Chin J Digestol 2013;21:2451–2455. [Google Scholar]

- 107. Yasir M, Mehta KS, Banday VH, et al. Evaluation of post operative shoulder tip pain in low pressure versus standard pressure pneumoperitoneum during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surgeon 2012;10:71–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Zaman M, Chowdhary K, Goyal P. Prospective randomized trial of low pressure pneumoperitoneum for reduction of shoulder tip pain following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a comparative study. World J Laparosc Surg 2015;8:13–15. [Google Scholar]

- 109. Bruintjes MH, van Helden EV, Braat AE, et al. Deep neuromuscular block to optimize surgical space conditions during laparoscopic surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Anaesth 2017;118:834–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Vlot J, Wijnen R, Stolker RJ, et al. Optimizing working space in laparoscopy: CT measurement of the effect of pre-stretching of the abdominal wall in a porcine model. Surg Endosc 2014;28:841–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Diaz-Cambronero O, Flor Lorente B, Mazzinari G, et al. A multifaceted individualized pneumoperitoneum strategy for laparoscopic colorectal surgery: a multicenter observational feasibility study. Surg Endosc 2019;33:252–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All extracted data can be made available upon reasonable request by contacting the corresponding author. Data collection forms and analytic code were based on the PRISMA guidelines and can also be shared upon reasonable request.