Abstract

Video Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES

Former premature infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) are at risk for hypoxemia during air travel, but it is unclear until what age. We aimed to determine pass rates for high altitude simulation testing (HAST) by age in children with BPD and identify risks for failure.

METHODS

Retrospective, observational analysis of HAST in children with BPD at Boston Children’s Hospital, using interval censoring to estimate the time-to-event curve of first pass. Curves were stratified by neonatal risk factors. Pass was considered lowest Spo2 ≥ 90%, or ≥94% for subjects with ongoing pulmonary hypertension (PH).

RESULTS

Ninety four HAST studies were analyzed from 63 BPD subjects; 59 studies (63%) were passed. At 3 months corrected gestational age (CGA), 50% of subjects had passed; at 6 months CGA, 67% has passed; at 12 and 18 months CGA, 72% had passed; and at 24 months CGA, 85% had passed. Neonatal factors associated with delayed time-to-pass included postnatal corticosteroid use, respiratory support at NICU discharge, and tracheostomy. BPD infants who did not require respiratory support at 36 weeks were likely to pass (91%) at 6 months CGA. At 24 months, children least likely to pass included those with a history of PH (63%) and those discharged from the NICU with oxygen or respiratory support (71%).

CONCLUSIONS

Children with BPD on respiratory support at 36 weeks should be considered for preflight hypoxemia challenges through at least 24 months CGA, and longer if they had PH or went home from NICU on respiratory support.

What’s Known on This Subject:

Preterm children are at risk for hypoxemia during air travel, with greater risk among those with bronchopulmonary dysplasia; however, it is not known until what age these children should undergo preflight screening.

What This Study Adds:

Children with bronchopulmonary dysplasia on respiratory support at 36 weeks risked development of hypoxemia during preflight challenges until 24 months corrected age. Children with a history of pulmonary hypertension or discharged on respiratory support remained at risk at 24 months.

Preterm infants are at increased risk of hypoxemia during air travel, with greater risk seen in those with bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD).1,2 Commercial air travel occurs at 9000 to 13 000 m, with cabins pressurized to 1530 to 2440 m (5000–8000 ft).2–4 At 8000 ft, the reduced oxygen tension is approximately 108 mmHg, compared with 148 mmHg at sea level, which is the equivalent of breathing approximately Fio2 of 15% at sea level.3 Although there is a small decrease in oxygen saturation in healthy individuals during air travel, this can be pathologic for those with lung disease.5,6 Former preterm infants with BPD have increased susceptibility because of altitude hypoxemia caused by periodic breathing, apneic pauses, lower residual volumes, higher airway resistance, ventilation-perfusion mismatch, and right-to-left shunting (which can be exacerbated in a hypoxic environment).3,7 High altitude simulation testing (HAST) can identify infants at highest risk for in-flight hypoxemia and who may require supplemental oxygen for safe air travel.3

By 3 months corrected gestational age (CGA), preterm infants without lung disease are unlikely to develop hypoxemia during HAST.8 However, multiple studies have shown preterm infants with BPD are likely to fail HAST beyond their estimated date of delivery (EDD). British Thoracic Society (BTS) guidelines suggest that infants under 1 year of age with a history of neonatal chronic lung disease should have HAST performed, though other studies suggest some children with a history of BPD may fail beyond this age.2,3,9,10 It is not clear how long children with BPD require HAST, and if additional risk factors from the neonatal course may help distinguish those at highest risk for development of hypoxemia.

The aim of this study is to conduct a longitudinal survival analysis on a large sample of HAST results from a cohort of children with BPD, including some children with multiple HASTs at different points in time, to identify the likelihood of developing hypoxemia during HAST over time and to identify neonatal risk factors for developing hypoxemia. We hypothesize that children with more severe neonatal courses, including those with longer durations of respiratory support, greater support need at 36 weeks, and pulmonary hypertension (PH) will be at greater risk of developing hypoxemia during HAST through 2 years of age.

Methods

Subjects

We selected BPD subjects who completed a HAST from the Preterm Lung Patient Registry at Boston Children’s Hospital (BCH).11 This registry includes former preterm infants followed in pulmonology at BCH for postprematurity respiratory disease and is approved by the institutional review board. This study included former preterm infants born ≤ 34 weeks gestational age (GA) followed between 2008 and 2019 (May 31, 2020 dataset). Children with congenital cardiac disease, pulmonary diagnoses other than BPD, or congenital and genetic anomalies that contribute to their respiratory disease were excluded. Informed consent was obtained for each participant enrolled after 2008; an additional 2 subjects were enrolled under a waiver of consent for retrospective review.

Demographics and NICU history were collected after enrollment from questionnaires and NICU discharge summaries. We defined BPD by National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) criteria as having used at least 28 days of oxygen after birth with severity assessed based on respiratory support at 36 weeks postmenstrual age for infants < 32 weeks and at 56 days or discharge for infants 32 to 34 weeks.12 Respiratory support at 36 weeks and at discharge was defined as nasal cannula oxygen, positive pressure, or mechanical ventilation. Presence of PH was defined as any echocardiogram at postmenstrual age (PMA) ≥ 36 weeks interpreted by a cardiologist to suggest elevated right ventricular pressure. If no echocardiogram was performed after 36 weeks PMA because it was not indicated for screening, it was assumed PH was not present. Presence of PH before HAST was determined by the last echocardiogram performed at BCH before HAST.

High Altitude Simulation Testing

Subjects underwent HAST as clinically indicated for preflight testing as ordered by a pulmonary provider. Baseline Spo2 was collected in ambient air, or for subjects on supplemental o2 at baseline, on their baseline level of support. HAST was performed via administration of 15% o2 blended with 85% nitrogen at 15 L per min via a face mask up to 15 minutes as previously described.3,13 Spo2 was continuously measured by pulse oximetry (Masimo Rad 7, Irvine, CA). Lowest and ending Spo2 was recorded. To standardize outcomes for this study, a subject was considered to pass HAST if lowest and ending Spo2 ≥ 90%, unless the patient had PH on most recent echocardiography, in which case a cutoff of Spo2 ≥ 94% was used.

We chose to include children on supplemental oxygen at baseline, as children can still develop hypoxemia during HAST on their baseline oxygen flow, and eliminating these subjects might introduce bias into the sample.

Statistical Analysis

We conducted an interval-censored time-to event analysis to determine time until HAST pass using a model design based on survival analysis methadology.14 This method allows for estimation of time until an event, in this case passing HAST, when the exact time of the event falls within an unknown interval of time; in this case, the exact time a subject physiologically passes HAST is unknown (as tests are only performed as clinically indicated) but can be estimated between the last HAST fail and the first HAST pass. The left bound of the interval in this case is the last time a subject failed HAST, or for a subject that never failed HAST by our records, assumed at EDD. The right bound on the interval in this case is the first time a subject passed HAST, or for a subject that never passed HAST by our records, infinity. For events that occur during the interval, it is assumed in nonparametric analysis that each time point on the interval has equal probability of the event occurring.

An overall time-to-event analysis was then constructed for time until HAST pass. Univariate analyses were conducted to create time-to-event “survival” curves stratified by neonatal risk factors. Differences in curves were computed by log-rank testing; curves were used to derive likelihood of event (HAST pass or fail) at predefined time intervals (6 months, 12 months, 18 months, 24 months) using Turnbull estimation.15 We also conducted multivariable analyses for each neonatal risk factor using Cox proportional hazards, though these did not use interval censoring as described above. These analyses were adjusted for GA ≤ 28 weeks, birth weight ≤ 750 g, and sex; outcomes after 36 weeks were also adjusted for severe BPD. All analyses were performed using R v4.2.2 (2022-10-31); survival analyses were performed using the following R packages: survival (v. 3.4), interval (v. 1.1-0.8), and icenReg (v. 2.0.15).16–18

Sensitivity Analyses

To compare the above results with time-to-event curves created using the more familiar Kaplan-Meier estimates, we performed 2 sensitivity analyses with the following assumptions, which allow for a single defined time-point of the event HAST pass: (1) pass assumption: assume that the last time point at which a subject fails HAST is the age of the last failed HAST (EDD for subjects who never fail) and at any time point afterward the subject would pass HAST; and (2) fail assumption: assume that the first time point at which a subject passes HAST is the age of the first passed HAST (or infinity for subjects who never pass), and at any time point before the subject would have failed HAST.

Results

There were 63 subjects included in the analysis (Table 1). There was a slight predominance of males and Caucasians. Overall, subjects represent a group of former premature infants with substantial respiratory disease, being on average extremely premature (median GA 26 6/7 weeks) with extremely low birth weight (median 735 g) and the majority with severe BPD (60%). A notable number had history of PH at ≥ 36 weeks PMA (37%).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Demographics

| Subject Characteristics | N = 64 subjects |

|---|---|

| Birth year | 2006–2019 |

| Male, N (%) | 35 (56) |

| Race, N (%) | |

| Caucasian | 22 (35) |

| African American | 13 (21) |

| Asian | 14 (22) |

| Other or unknown | 14 (22) |

| Hispanic, N (%) | 8/56 (14) |

| Birth weight (g), median (range) | 735 (400–1460) |

| BW ≤ 750g, N (%) | 33 (52) |

| GA (weeks), median (range) | 26 6/7 (23 1/7–32 4/7) |

| GA ≤ 28 wk, N (%) | 46 (73) |

| NICU ventilator days, median (IQR) | 15 (2–44) |

| Ventilator days > 14 d, N (%) | 31/56 (55) |

| NICU CPAP days, median (IQR) | 42 (30–60.5) |

| CPAP days > 30 d | 40/53 (75) |

| Gastrostomy tube, N (%) | 18/59 (30) |

| Tracheostomy, N (%) | 4/60 (7) |

| Any postnatal corticosteroids, N (%) | 31/54 (57) |

| Any respiratory support at 36 wk, N (%) | 49 (78) |

| Discharged on respiratory support (o2 or PPV) | 32/61 (52) |

| BPD, N (%) | |

| Mild | 14 (22) |

| Moderate | 11 (17) |

| Severe | 38 (60) |

| Pulmonary hypertension ≥ 36 wk CGA | 24 (38) |

| High altitude simulation testing | |

| Studies per patient, mean (range) | 1.5 (1–5) |

| CGA at first study, median (range, IQR) | 12 (2–90, 7–30) |

| Ever passed HAST, N (%) | 50 (79)a |

| Passed first HAST, N (%) | 40 (63) |

| CGA (months) at first pass, median (range, IQR) | 12.5 (3–103, 6–33) |

| CGA (months) at last fail, median (range, IQR) | 15 (2–124, 7–26) |

GA, gestational age; PPV, positive pressure ventilation.

Seven subjects passed multiple studies.

There were 94 HAST studies included in the analysis; 20 (32%) subjects had more than 1 HAST included (Table 2). Studies occurred at median age of 14 months CGA (range 2–124); first study occurred at median age of 12 months CGA (range 2–90). There were 5 (5%) studies for which the subject had PH on the last echocardiogram before the study. During challenge at Fio2 15%, the median change in oxygen saturation was a decrease of −8% (interquartile range [IQR] −6 to −10%) from baseline. Using the prespecified cutoffs of Spo2 < 90% for subjects without active PH and Spo2 < 94% for subjects with PH, 35 (37%) of studies developed hypoxemia during HAST.

TABLE 2.

High Altitude Simulation Testing Results

| Study Characteristic and Result | N = 96 studies |

|---|---|

| Age at study (months), median (range, IQR) | 17 (4–127, 10–37) |

| CGA at study (months), median (range, IQR) | 14 (2–124, 7–35) |

| Pulmonary hypertension on echocardiogram before study, N (%) | 5 (5) |

| On supplemental o2 at baseline at time of study, N (%) | 3 (3) |

| Baseline Spo2 ≥ 96%, N (%) | 90 (96) |

| Decrease in Spo2 during study from baseline to lowest, median (IQR) | 8 (6–10) |

| Lowest Spo2 < 90%, N (%) | 33 (35) |

| Pass HASTa, N (%) | 59 (63) |

By prespecified criteria: lowest Spo2 < 90%, or <94% if pulmonary hypertension seen on last echocardiography before study.

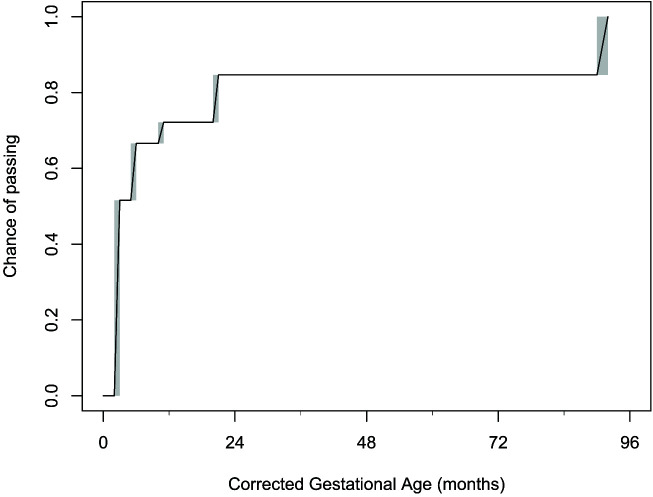

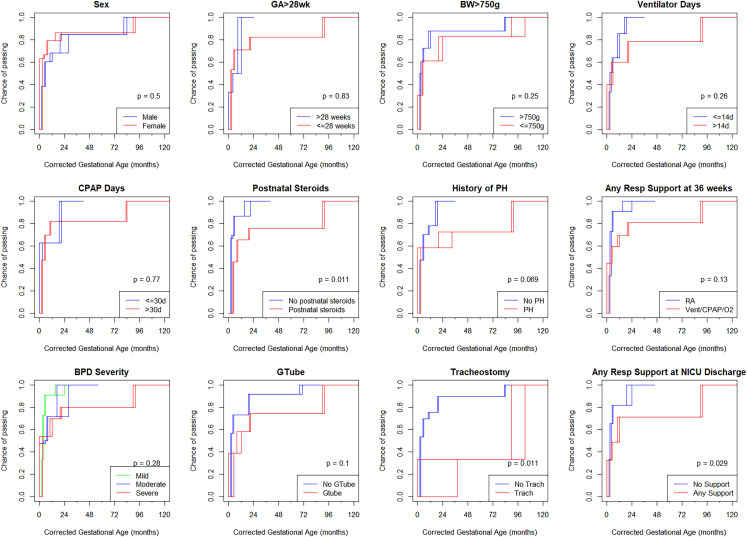

Time-to-pass HAST analysis using interval censored data are shown in Fig 1. On the cumulative distribution function curve, the probability of passing HAST at 3 months CGA was 50%, at 6 months CGA was 67%, at 12 months CGA was 72%, at 18 months CGA was 72%, and at 24 months CGA was 85%. Univariate analysis by neonatal risk factors is shown in Fig 2. By log-rank test, time-to-pass was significantly different for history of tracheostomy, postnatal corticosteroid use, and respiratory support at NICU discharge (Fig 2).

FIGURE 1.

Time-to-pass high altitude simulation testing presented as an interval censored analysis with shaded boxes representing intervals where the exact time of pass is unknown but falls somewhere on that interval. Diagonal lines within the shaded areas represent the Turnball estimations. Median survival line (50% pass) was at 3 months CGA.

FIGURE 2.

Time-to-pass high altitude simulation testing by neonatal risk factors presented as an interval censored analyses; rectangular boxes in each survival curve represent intervals where the exact time of test pass is unknown but falls somewhere on the interval. P values determined by log-rank testing. BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia (severity by 2001 NHLBI definition); BW, birth weight; GA, gestational age; Gtube, gastrostomy tube; PHTN, ulmonary hypertension.

In multivariable analysis with Cox proportional hazards, ventilation > 14 days, postnatal corticosteroids, respiratory support at 36 weeks PMA, and severe BPD (after controlling for GA, BW, and sex) had hazard ratios that suggested significantly lower proportional odds of passing HAST at any time point. PH after 36 weeks (after controlling for GA, BW, sex, and severe BPD) also had a hazard ratio suggesting lower proportional odds of passing HAST (Supplemental Tables 4A and 4B).

The time-to-pass HAST curves were used to calculate the probability of passing HAST at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months CGA based on neonatal risk factors (Table 3). Infants who were no longer on respiratory support at 36 weeks PMA had a high likelihood (>90%) of passing HAST at each time point. At 18 months, infants who had not required postnatal corticosteroids also had a high likelihood of passing HAST, and at 24 months, each of the following aspects from neonatal history were associated with >90% probability of passing HAST: ≤30 days of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) support, no gastrostomy tube, no tracheostomy, no postnatal corticosteroids, no respiratory support at 36 weeks PMA, not discharged on respiratory support, mild to moderate BPD, and no PH. Conversely, at 24 months, infants with PH (63%) or who had been discharged on respiratory support (71%) were least likely to have passed HAST. Results beyond 24 months remained similar based on an additional 32 studies done at this age.

TABLE 3.

Probability of Passing High Altitude Simulation Testing by Risk Factors

| Risk Factors | 6 mo | 12 mo | 18 mo | 24 mo |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex = male | 0.6 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.76 |

| Sex = female | 0.67 | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.86 |

| GA > 28 wk | 0.5 | 1a | 1a | 1a |

| GA ≤ 28 wk | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.83 |

| BW > 750 g | 0.73 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.88 |

| BW ≤ 750 g | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.83 |

| Ventilated days ≤ 14 d | 0.64 | 0.86 | 0.93a | 1a |

| Ventilated days > 14 d | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.79 |

| CPAP days ≤ 30 d | 0.62 | 0.62 | 0.62 | 1a |

| CPAP days > 30 d | 0.7 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.82 |

| No postnatal corticosteroids | 0.87 | 0.87 | 0.93a | 1a |

| Postnatal corticosteroids | 0.46 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.76 |

| No respiratory support at 36 wk | 0.91a | 0.91a | 0.94a | 1a |

| Respiratory support at 36 wk | 0.6 | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.81 |

| Mild BPD | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.82 | 1a |

| Moderate BPD | 0.5 | 0.71 | 0.74 | 0.9a |

| Severe BPD | 0.53 | 0.68 | 0.68 | 0.78 |

| No PH after 36 wk PMA | 0.7 | 0.78 | 0.89 | 1a |

| PH after 36 wk PMA | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.63 |

| No Gtube | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.73 | 0.92a |

| Gtube | 0.39 | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.74 |

| No tracheostomy | 0.7 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.9a |

| Tracheostomy | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.21 |

| Discharged without respiratory support (o2 or PPV) | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 1a |

| Discharged with respiratory support (o2 or PPV) | 0.49 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.71 |

Probabilities calculated from survival curves using interval analysis and Turnball estimation. BW, birth weight; GA, gestational age; PPV, positive pressure ventilation.

Represent probability of pass ≥ 90%.

When only including the 50 children who ever passed HAST in the analysis, at 9 months CGA there was 90% probability of passing. Among the 2 children with tracheostomy who ever passed HAST, the ages at first pass were 103 and 38 months (mean 70.5 months); among the 18 children with a history of PH at any point after 36 weeks PMA and who ever passed HAST, the median age to pass was 42 months, and the probability of passing HAST did not reach 90% until 8 years.

Sensitivity analyses using the pass or fail assumptions resulted in leftward or rightward shifted survival curves (time-to-HAST pass), respectively, using Kaplan-Meier estimates (Supplemental Figs 3 and 5); using the pass assumption (an infant passes HAST immediately after the last failed HAST, or at 0 months if never failed) probability of passing HAST was >50% at 0 months CGA; using the fail assumption (an infant passes HAST only at the first documented pass, and fails up until that point), the probability of passing HAST was 50% at 13 months CGA. In univariate analyses using log-rank testing, similar neonatal risk factors were identified using the pass assumption; however, using the fail assumption, more neonatal factors were able to discriminate between the likelihood of passing or failing HAST compared with the main analysis (Supplemental Figs 4 and 6).

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate a high frequency of developing hypoxemia during HAST in a cohort of children with bronchopulmonary dysplasia, with increased likelihood of failure among those with more neonatal risk factors. In time-to-pass HAST analyses using interval censoring to account for uncertainty in the exact time a child passes HAST, 50% of infants had passed HAST by 3 months CGA, 67% by 6 months CGA, and 72% at 12 months CGA. Infants who did not require respiratory support at 36 weeks’ PMA (mild BPD) were likely to pass HAST (91%) at 6 months CGA. In those with moderate BPD, HAST pass rates did not get above 90% until 24 months of age, and in those with severe BPD, HAST pass rates were 78% at 24 months of age. Additionally, we identified multiple neonatal risk factors associated with a longer time-to-pass, including postnatal corticosteroid use, respiratory support at NICU discharge, and tracheostomy tube placement.

Our study confirms that young children with postprematurity respiratory disease (such as BPD) have a high frequency of hypoxemia during HAST well after NICU discharge.2,10 Previous studies demonstrated that there is limited use for HAST up until the estimated date of delivery, and that preterm infants without BPD are likely to pass HAST after 40 weeks PMA.2,8,19 Fewer studies have evaluated children with BPD, particularly after early infancy, though the limited data has suggested high rates of failure well beyond NICU discharge.10 At least 1 study suggests that prolonged supplemental oxygen exposure is a risk factor for later failure.20 Ongoing hypoxemia during HAST may also indicate increased susceptibility to hypoxemia under stress for a prolonged time after NICU discharge in these children.21–23

In our study we found low HAST pass rates in subjects with BPD under 24 months CGA in the overall cohort. Children with mild BPD, who had not been on respiratory support at 36 weeks PMA and did not have other neonatal risk factors, had a high pass rate as soon as 6 months CGA (91%). Additionally, infants who had not received postnatal corticosteroids had a 93% chance of passing HAST at 18 months. At 24 months, infants with any of the following characteristics had a high likelihood (>90%) of passing HAST: CPAP duration ≤ 30 days, no gastrostomy tube, no tracheostomy, no postnatal corticosteroids, no respiratory support at 36 weeks PMA, no respiratory support at NICU discharge, mild-moderate BPD, no PH. Of these characteristics, a history of tracheostomy and history of PH were the most discriminatory at 24 months CGA; in other words, the greatest difference in pass rates was between infants with and without the characteristic. PH has previously been identified as a risk factor for in-flight hypoxemia in adults.24

Based on our current study, we propose that children who remain on respiratory support at 36 weeks should undergo HAST until at least 24 months CGA. BPD patients who have more severe disease based on neonatal risk factors, including a history of PH or discharge from the NICU on respiratory support may require preflight testing after 24 months. This would need to be validated by a prospective, longitudinal study before adapted into clinical use. Additionally, our analysis does not account for post-NICU disease severity, such as ongoing respiratory symptoms or frequent respiratory exacerbations, flight duration, or flights traveling with lower cabin pressures.

The current study, similar to prior investigations, is observational, with HAST occurring as clinically indicated. This leaves results subject to informative censoring bias, where families of patients with more severe disease may elect to wait longer to use commercial air travel. In the current study we assessed time-to-pass HAST using an interval censoring analysis to account for uncertainty in the exact time a child passes HAST. If traditional “survival analyses” by Kaplan-Meier methods are used, it will bias these individuals to appearing as if it had taken longer to pass HAST. By using time-to-event survival analyses with interval censoring, along with a cohort of participants for whom many have multiple studies, this study addresses that methodologic concern by computing time-to-event curves knowing that the actual time that hypoxemia during HAST resolves may have occurred anytime between last HAST fail and first HAST pass.14

Limitations include recruitment bias as the entire cohort is selected from children with postprematurity respiratory disease and families considering commercial air travel, which may cause selection bias both with regards to disease severity (parents judging their children as well enough to fly) as well as socioeconomic factors (families who can afford commercial air travel). This cohort followed in pulmonary clinic, in particular, has been noted to have higher rates of severe BPD and have more substantial respiratory illness severity than general preterm population cohorts.25 Other studies have suggested that HAST may be an unreliable indicator for hypoxemia during airplane travel in young infants, particularly before their EDD; however this remains the gold standard per BTS guidelines.3,19,26 Finally, we chose Spo2 90% as a cutoff for pass for children without current PH, and 94% for those with ongoing PH, which is the standard of care at Boston Children’s Hospital. This cutoff has been debated, with some suggesting that Spo2 85% may be more appropriate than 90%.9 Our approach is consistent with BTS guidelines that state that for infants with Spo2 85% to 90% on HAST, “the doctor should err on the side of caution,” which the authors feel is applicable for a cohort with significant baseline lung disease who are at risk for development of PH and other complications of hypoxemia.20,27,28

Conclusions

Children with postprematurity respiratory disease have high rates of hypoxemia during HAST, particularly under 24 months CGA; children who were not on respiratory support at 36 weeks PMA are less likely to develop hypoxemia during HAST, whereas factors associated with premature lung disease severity, including those with a history PH, who received postnatal corticosteroids, or were discharged from the NICU on respiratory support, were most likely to develop hypoxemia during HAST through 2 years of age. This has implications for consideration of fitness to fly and ongoing hypoxemia in stress conditions in children born prematurely.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Priya Desai for her contributions to HAST data extraction and database entry, Henry Feldman PhD for statistical guidance early in study design, and Lawrence Rhein MD for developing the BPD registry and implementing the HAST protocol.

Glossary

- BPD

bronchopulmonary dysplasia

- CGA

corrected gestational age

- EDD

estimated date of delivery

- HAST

high altitude simulation testing

- PH

pulmonary hypertension

- PMA

post-menstrual age

Footnotes

Dr Levin conceptualized and designed the study, collected data, performed the initial analysis, and drafted the initial manuscript; Dr Sheils conceptualized the study and collected data; Dr Hayden conceptualized the study, designed the data collection instruments, and provided supervision and guidance for data analysis; and all authors reviewed and revised the manuscript, approved the final manuscript as submitted, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FUNDING: This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (K23 HL136851 [LP Hayden]) and the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NLM T15LM007092 [Nils Gehlenborg]).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- 1. Pryhuber GS, Maitre NL, Ballard RA, et al. ; Prematurity and Respiratory Outcomes Program Investigators . Prematurity and respiratory outcomes program (PROP): study protocol of a prospective multicenter study of respiratory outcomes of preterm infants in the United States. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vetter-Laracy S, Osona B, Peña-Zarza JA, Gil JA, Figuerola J. Hypoxia challenge testing in neonates for fitness to fly. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):e20152915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ahmedzai S, Balfour-Lynn IM, Bewick T, et al. ; British Thoracic Society Standards of Care Committee . Managing passengers with stable respiratory disease planning air travel: British Thoracic Society recommendations. Thorax. 2011;66(Suppl 1):i1–i30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nicholson TT, Sznajder JI. Fitness to fly in patients with lung disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(10):1614–1622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lee AP, Yamamoto LG, Relles NL. Commercial airline travel decreases oxygen saturation in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2002;18(2):78–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Parkins KJ, Poets CF, O’Brien LM, Stebbens VA, Southall DP. Effect of exposure to 15% oxygen on breathing patterns and oxygen saturation in infants: interventional study. BMJ. 1998;316(7135):887–891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Samuels MP. The effects of flight and altitude. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89(5):448–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bossley CJ, Cramer D, Mason B, et al. Fitness to fly testing in term and ex-preterm babies without bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2012;97(3):F199–F203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Martin AC, Verheggen M, Stick SM, et al. Definition of cutoff values for the hypoxia test used for preflight testing in young children with neonatal chronic lung disease. Chest. 2008;133(4):914–919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Udomittipong K, Stick SM, Verheggen M, Oostryck J, Sly PD, Hall GL. Pre-flight testing of preterm infants with neonatal lung disease: a retrospective review. Thorax. 2006;61(4):343–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Levin JC, Sheils CA, Gaffin JM, Hersh CP, Rhein LM, Hayden LP. Lung function trajectories in children with post-prematurity respiratory disease: identifying risk factors for abnormal growth. Respir Res. 2021;22(1):143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jobe AH, Bancalari E. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163(7):1723–1729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hall GL, Verheggen M, Stick SM. Assessing fitness to fly in young infants and children. Thorax. 2007;62(3):278–279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rodrigues AS, Calsavara VF, Silva FIB, Alves FA, Vivas APM. Use of interval-censored survival data as an alternative to Kaplan-Meier survival curves: studies of oral lesion occurrence in liver transplants and cancer recurrence. Applied Cancer Research. 2018;38(1):16 [Google Scholar]

- 15. Turnbull BW. Nonparametric estimation of a survivorship function with doubly censored data. J Am Stat Assoc. 1974;69(345):169–173 [Google Scholar]

- 16. Therneau TM, Lumley T, Atkinson E, Crowson C. Survival analysis. Available at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survival. Accessed June 17, 2020

- 17. Fay MP, Shaw PA. Exact and asymptotic weighted Logrank tests for interval censored data: the interval R package. J Stat Softw. 2010;36(2):i02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Anderson-Bergman C. icenReg: regression models for interval censored data in R. J Stat Softw. 2017;81(12):1–23 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Resnick SM, Hall GL, Simmer KN, Stick SM, Sharp MJ. The hypoxia challenge test does not accurately predict hypoxia in flight in ex-preterm neonates. Chest. 2008;133(5):1161–1166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Martin RJ, Di Fiore JM, Walsh MC. Hypoxic episodes in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Clin Perinatol. 2015;42(4):825–838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yeh J, McGrath-Morrow SA, Collaco JM. Oxygen weaning after hospital discharge in children with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2016;51(11):1206–1211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moyer-Mileur LJ, Nielson DW, Pfeffer KD, Witte MK, Chapman DL. Eliminating sleep-associated hypoxemia improves growth in infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatrics. 1996;98(4 Pt 1):779–783 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sekar KC, Duke JC. Sleep apnea and hypoxemia in recently weaned premature infants with and without bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatr Pulmonol. 1991;10(2):112–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Roubinian N, Elliott CG, Barnett CF, et al. Effects of commercial air travel on patients with pulmonary hypertension air travel and pulmonary hypertension. Chest. 2012;142(4):885–892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Annesi CA, Levin JC, Litt JS, Sheils CA, Hayden LP. Long-term respiratory and developmental outcomes in children with bronchopulmonary dysplasia and history of tracheostomy. J Perinatol. 2021;41(11):2645–2650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Josephs LK, Coker RK, Thomas M; BTS Air Travel Working Group; British Thoracic Society . Managing patients with stable respiratory disease planning air travel: a primary care summary of the British Thoracic Society recommendations. Prim Care Respir J. 2013;22(2):234–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Abman SH, Wolfe RR, Accurso FJ, Koops BL, Bowman CM, Wiggins JW Jr. Pulmonary vascular response to oxygen in infants with severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatrics. 1985;75(1):80–84 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tay-Uyboco JS, Kwiatkowski K, Cates DB, Kavanagh L, Rigatto H. Hypoxic airway constriction in infants of very low birth weight recovering from moderate to severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Pediatr. 1989;115(3):456–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.