Keywords: airway responsiveness, asthma, developmental programming, insulin, maternal obesity

Abstract

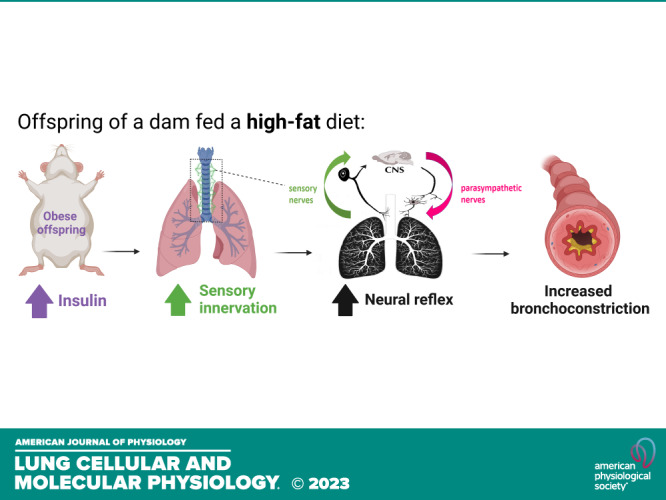

Children born to obese mothers are prone to develop asthma and airway hyperresponsiveness, but the mechanisms behind this are unclear. Here we developed a mouse model of maternal diet-induced obesity that recapitulates metabolic abnormalities seen in humans born to obese mothers. Offspring of dams fed a high-fat diet (HFD) showed increased adiposity, hyperinsulinemia, and insulin resistance at 16 wk of age despite being fed only a regular diet (RD). Bronchoconstriction induced by inhaled 5-hydroxytriptamine was also significantly increased in offspring of HFD-fed versus RD-fed dams. Increased bronchoconstriction was blocked by vagotomy, indicating this reflex was mediated by airway nerves. Three-dimensional (3-D) confocal imaging of tracheas collected from 16-wk-old offspring showed that both epithelial sensory innervation and substance P expression were increased in the offspring of HFD-fed dams compared with offspring of RD-fed dams. For the first time, we show that maternal high-fat diet increases airway sensory innervation in offspring, leading to reflex airway hyperresponsiveness.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Our study reveals a novel potential mechanism, by which maternal high-fat diet increases the risk and severity of asthma in offspring. We found that exposure to maternal high-fat diet in mice leads to hyperinnervation of airway sensory nerves and increased reflex bronchoconstriction in offspring fed a regular diet only. These findings have important clinical implications and provide new insights into the pathophysiology of asthma, highlighting the need for preventive strategies in this patient population.

INTRODUCTION

More than 650 million adults, accounting for ∼13% of the global adult population, are classified as obese (1). In developed countries, 3 in 10 women are obese during pregnancy (2). The impact of maternal obesity is not limited to one generation, as it can affect the overall health of subsequent generations (3). Studies have indicated that the offspring of overweight and obese mothers are at a higher risk of developing respiratory complications, including wheezing and asthma both in childhood and later in life (4–6). However, the mechanisms by which maternal obesity increases asthma risk in offspring remain unclear, making it difficult to develop effective preventive or treatment strategies.

Neural dysfunction plays a critical role in asthma pathogenesis. Sensory nerves are densely distributed in the airway’s epithelial layers, detecting stimuli and relaying information to the central nervous system (7), which triggers parasympathetic efferent nerves to induce reflex bronchoconstriction (8). Parasympathetic nerves regulate airway tone and induce bronchoconstriction by releasing acetylcholine, an agonist for muscarinic receptors, stimulating smooth muscle contraction and bronchoconstriction (9). This sensory and parasympathetic nerve-mediated reflex bronchoconstriction occurs in response to a variety of stimuli, including methacholine, histamine, cold air, exercise, and allergens. Increased nerve-mediated bronchoconstriction has been observed in all tested animal models of asthma, including antigen challenge (9), viral infection (10), exposure to ozone (11), and insulin (12). Importantly, this reflex is also increased in individuals with asthma (13, 14). A recent study using bronchoscopic biopsies demonstrated that patients with severe asthma had a significant increase in sensory innervation (15).

Obesity-induced insulin resistance and compensatory hyperinsulinemia can also increase asthma risk in humans, independent of other variables (16–18). Clinical data indicate that high insulin levels can decrease lung function (19, 20). Obesity during pregnancy predisposes offspring to insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia, as seen in humans and animals (21). Furthermore, we have previously shown that increase in circulating insulin potentiates airway nerve-mediated bronchoconstriction in animal models of diet-induced obesity (12, 22, 23). In this study, we used a mouse model of maternal high-fat diet-induced obesity that recapitulates metabolic abnormalities in offspring that are commonly seen in humans (24). We used this model to investigate whether maternal obesity caused hyperinsulinemia in offspring, thereby increasing airway nerve-mediated bronchoconstriction.

METHODS

Ethical Considerations

All studies were carried out in accordance with protocols (TR01_IP00000251 and TR02_IP00000432) approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Oregon Health & Science University.

Animals

Wild-type FVB/NJ mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory and housed in a pathogen-free facility on a 12-h light/dark cycle with ad libitum access to food and water. To model maternal obesity in mice, female mice were randomly assigned to experimental groups fed either a regular diet (RD, 14% kcal from fat, LabDiet) or a high-fat diet (HFD, 45% kcal from fat, Envigo) starting at 6 wk of age and continuing for 8 wk and throughout pregnancy and lactation. The composition of the diet has been reported before (24). After 8 wk of dietary intervention, female mice were bred with RD-fed males (Fig. 1A), and the breeding couples were fed according to the maternal diet. The female dams continued on their respective diets throughout pregnancy and lactation until the offspring were weaned at 3 wk of age and switched to a regular diet. Body fat was measured by nuclear magnetic resonance (EchoMRI, Houston, TX) as previously described (23). Offspring mice were fasted overnight (except for neonate P1 mice) before physiological measurement or tissue collection. Tracheal samples and fasting blood from the abdominal vein were collected at different time points as indicated. Blood glucose was measured using a glucometer (OneTouch Ultra2, LifeScan, Inc., Milpitas, CA). Plasma insulin was quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (mouse insulin ELISA, 10–1247-01, Mercodia, Winston-Salem, NC).

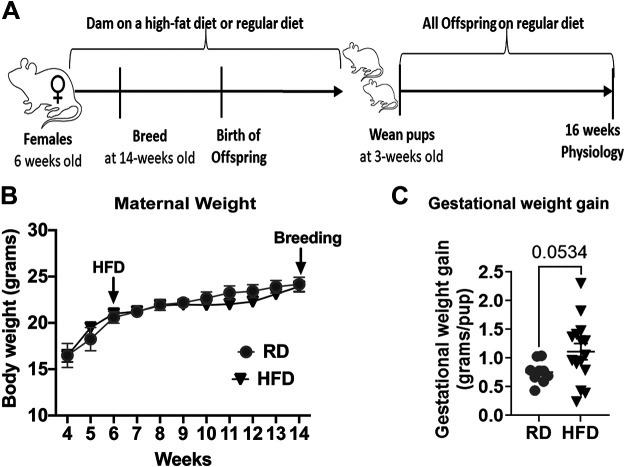

Figure 1.

Mouse model of maternal high-fat diet-induced obesity. Study design (A). Dams on a high-fat diet (HFD) did not gain significant weight before breeding (B) but had significantly higher gestational weight gain (C) compared with dams on a regular diet (RD). n = 7 for RD and n = 8 for HFD in B. n = 9 for RD and n = 15 for HFD in C. Data were analyzed by t test and are presented as means ± SE.

Measurement of Bronchoconstriction and Airway Resistance In Vivo

Mice were anesthetized using ketamine (100 mg/kg ip) and xylazine (10 mg/kg ip), tracheostomized, and ventilated (100% oxygen, 0.2 mL tidal volume, 120 breaths/min) with a positive end-expiratory pressure of 2 cmH2O. Mice were also paralyzed with succinylcholine (20 mg/kg im). Body temperature was monitored by a rectal thermometer and maintained between 36°C and 37°C by a heating pad and lamp. Heart rate was monitored by electrocardiogram. Inspiratory flow was measured via pneumotachograph (MLT1L, ADInstruments) and pressure was recorded with a differential pressure transducer (MLT0670, ADInstruments). Data were recorded using a PowerLab 4/SP analog-to-digital converter and analyzed with the LabChart Pro software (ADInstruments).

Airway resistance was measured as previously described (25). In brief, after two deep inspirations, an inspiratory pause for 225 ms at peak inspiration was given for six breaths in a row. For each breath, both peak pressure and end-inflation pressure (plateau pressure) were recorded, and resistance was calculated as the average (Ppeak − Pplateau)/inspiratory flow of these four breaths. Airway resistance was then measured before each aerosolized treatment, either aerosolized saline or 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT; 10 μL, 10–300 mM, Sigma Aldrich), via an in-line nebulizer, and 50 s after treatment. Treatment-induced bronchoconstriction was calculated as the difference between airway resistance after aerosolized challenge and that of right before the challenge, represented in cmH2O·mL−1·s−1. Two deep inhalations were administered between each treatment to ensure baseline recovery between doses. Neuronal contribution to bronchoconstriction was measured by comparing changes in airway resistance in response to inhaled increasing doses of 5-HT with and without vagotomy, as previously described (25).

Tissue Optical Clearing and Imaging and Quantification of Airway Nerves

The sensory innervation of airway epithelial and the expression of substance P in whole mounts tracheal of offspring were evaluated using a combination of techniques including immunostaining, tissue optical clearing, confocal microscopy, and digital three-dimensional (3-D) reconstruction of airway nerves, as was previously described (26, 27). Offspring mice, with the exception of P1, were perfused with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and their airways were excised and fixed in Zamboni fixative (Newcomer Supply) at 4°C overnight. Tracheas were blocked for 2 days with 4% normal goat serum, 1% Triton X-100, and 5% powdered milk, and then incubated with antibodies to pan-neuronal marker protein gene product 9.5 (PGP9.5, rabbit IgG, 1:200; AMSBIO) and substance P (rat IgG2A, 1:500; BD Pharmingen) overnight on a shaker at 4°C. After being washed, the tissues were incubated overnight in secondary antibodies (Alexa goat anti-rabbit 647, 1:1,000; Invitrogen and Alexa goat anti-rat 555, 1:1,000; Invitrogen) and counterstained using the nuclear stain 4′6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, dilactate; Molecular Probes). Tracheas were then optically cleared in n-methylacetamide/Histodenz (Ce3D) for 12 h (28) and mounted in Ce3D on slides in 120-μm deep imaging wells (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA).

Images were acquired using a ZEISS LSM900 confocal microscope and ×63/1.4 oil PlanApo DIC M27 objective with a 0.19-mm working distance. Samples were illuminated with 401, 553, and 653 nm light, and images were acquired as z-stacks. Two to three randomized images were taken for each mouse trachea using DAPI to locate the epithelium.

Quantification of Airway Epithelial Nerves and Neuronal Substance P Expression

Airway nerves were modeled in 3-D images using Imaris semiautomatic filament tracing software (Imaris 9.7, Oxford Instruments). A 3-D filament model was created around tracheal epithelial nerves to quantify nerve length and the number of branch points per image. Neuronal substance P expression was quantified by creating a surface around the substance P-positive voxels and using Imaris software to colocalize the volume of the voxels that were in contact with PGP9.5-positive nerve axon models. Total expression of substance P in three-dimensional images was measured in unit voxels. To normalize the substance P expression to the number of neurons, we calculated the ratio of substance P voxels to PGP9.5 voxels. Two to three images were quantified per mouse trachea and average values obtained from the two to three analyzed images were considered as the representative data for each individual animal. The experiment was conducted in a blinded manner with sample names concealed and replaced by numerical labels. Thus, the person responsible for capturing the images and processing the data remained unaware of the true identities of the samples. Identities were revealed only after completion to maintain objectivity and eliminate bias.

Statistical Analysis

The study used one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a Bonferroni post hoc test for body measurement data; unpaired Student’s t test for bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and blood cell count, for airway nerve length, and for branching points; and two-way repeated-measures ANOVA for airway resistance in response to inhaled nebulized methacholine and serotonin. P values less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant. The data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). The results are expressed as means ± SE.

RESULTS

Metabolic Dysfunction in the Offspring of a High-Fat Diet-Fed Mothers

Female mice that were fed a high-fat diet for 8 wk before pregnancy showed no significant changes in body weight (Fig. 1B), consistent with our previous reports (24), but had significantly greater visceral adiposity (data not shown) compared with females fed a regular diet. However, when the high-fat diet regimen was continued into pregnancy, it resulted in greater gestational weight gain (normalized to litter size) compared with a regular diet regimen (P < 0.1, Fig. 1C).

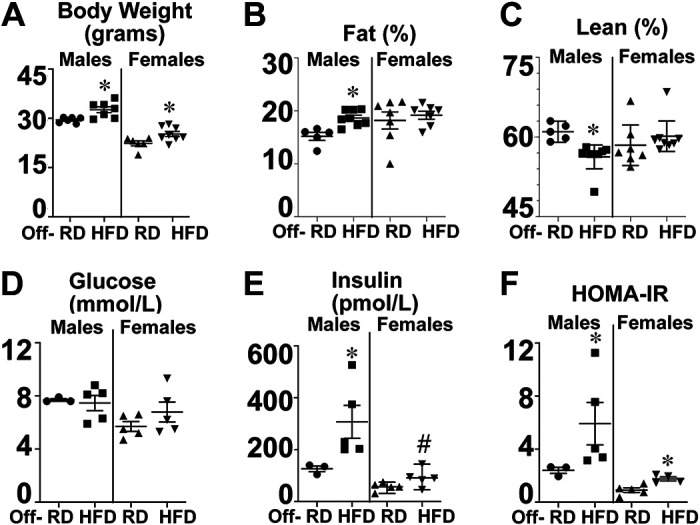

Despite being fed only a regular diet after weaning, 16-wk-old male offspring of high-fat diet-fed dams presented a significantly increased body weight (Fig. 2A, squares) and body fat percentage (Fig. 2B), and decreased lean mass (Fig. 2C) compared with offspring of dams on a regular diet (circles). Among female offspring, the body fat percentage was not affected by maternal diet (Fig. 2B), but the body weights (Fig. 2A) were increased in offspring of dams on a high-fat diet (downward triangles) versus dams on a regular diet (triangles). We have also observed hyperinsulinemia (Fig. 2E) and insulin resistance [assessed by homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) Fig. 2F], with no changes in fasting glucose (Fig. 2D) in both male and female offspring born from dams on a high-fat diet, similar to our previously published data from human babies born to obese mothers (29).

Figure 2.

Offspring of obese dams developed hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance at 16 wk of age. By 16 wk of age, male offspring of dams on a high-fat diet (■) had increased body weight (A), body fat percentage (B), and reduced lean mass (C) compared with offspring of dams on a regular diet (●). Female offspring of dams on a high-fat diet (▾) also had increased body weight at 16 wk (A), but neither body fat percentage (B) nor lean mass (C) compared with offspring of dams on a regular diet (▴). Fasting glucose (D) was not significantly different among groups, but fasting insulin (E) and homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance (HOMA-IR, F) were both significantly increased in offspring of dams on a HFD vs. RD. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA and are presented as means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. Off-RD; #P < 0.05 males vs. females within the same experimental group.

Overall, our findings recapitulate the epidemiological data showing that maternal high-fat diet before and during pregnancy and lactation leads to metabolic dysfunction in offspring, particularly in males, even when fed a regular diet after weaning.

Airway Nerve-Mediated Reflex Bronchoconstriction Is Increased in the Offspring of Obese Mother

We next measured the airway resistance in anesthetized, ventilated, and paralyzed mice at 16 wk of age. Responses to different concentrations of inhaled 5-hydroxytriptamine (5-HT, 10–300 mM, 10 µL) were recorded and compared before (Fig. 3A) and after vagotomy (Fig. 3B) or administration of the muscarinic receptor antagonist, atropine (3 mg/kg, iv), to measure the vagal reflex contribution to bronchoconstriction.

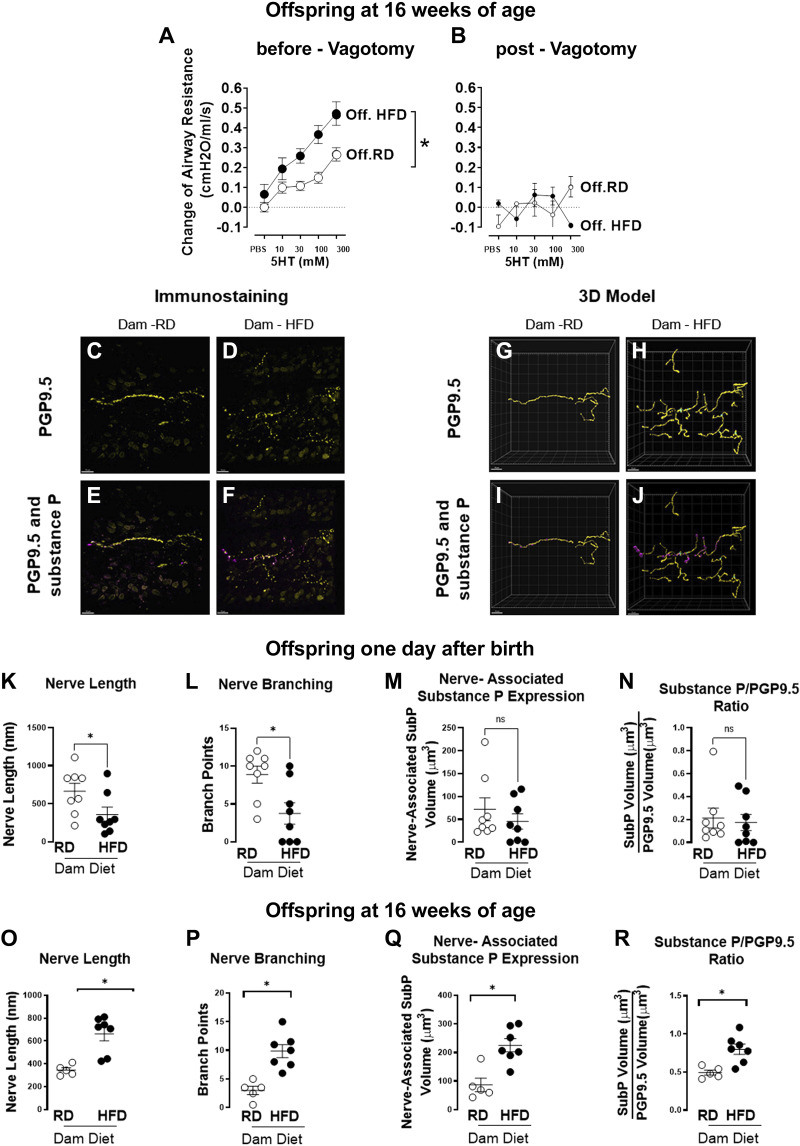

Figure 3.

Offspring of dams on a high-fat diet (HFD) had increased reflex bronchoconstriction, airway epithelial innervation, and neuronal substance P expression at 16 wk of age. Inhaled 5-HT induced stronger bronchoconstriction and significantly increased airway resistance in 16-wk-old offspring of dams on a high-fat diet (●) vs. offspring of dams on a regular diet (RD; ○) (A). The increased airway response was completely blocked by vagotomy (B), demonstrating that airway nerves were responsible for reflex bronchoconstriction. Whole tracheas from 1-day-old and from 16-wk-old offspring were stained with antibodies against pan-neuronal marker PGP9.5 (yellow) and neuropeptide substance P (magenta), optically cleared, and imaged with a laser-scanning confocal microscope. Representative maximum intensity projection images of z-stacks with PGP9.5 (C and D) and both PGP9.5 and colocalized substance P (E and F) stained epithelial nerves in offspring of regular chow (C and E) or high-fat diet (D and F) dams. Imaris software was used to create digital 3-D reconstructions of offspring of the regular diet-fed dams (G and I) and high-fat diet-fed dams (H and J). One-day-old offspring mice of high-fat diet-fed dams (●) had decreased nerve length (K) and nerve branching (L) compared with offspring of dams on a regular diet (○). However, nerve-associated substance P expression (M) and the ratio of substance P to PGP9.5 (N) were not significantly different between the two experimental groups. Sixteen-week-old offspring born to high-fat diet-fed dams (●) had increased nerve length (O), nerve branching (P), nerve-associated substance P expression (Q), and increased ratio of substance P to PGP9.5 (R) compared with offspring of dams on a regular diet (○). In A and B, each data point represents the mean ± SE using a two-way ANOVA, n = 9–13, *P < 0.05. In K–R, data are presented as means ± SE using a two-tailed Student’s t test, n = 5–8, *P < 0.05. 3-D, three-dimensional; 5-HT, 5-hydroxytryptamine; PGP9.5, protein gene product 9.5.

Before vagotomy (Fig. 3A), offspring of dams on a high-fat diet showed a significant increase in bronchoconstriction in response to inhaled 5-hydroxytriptamine in a dose-dependent manner, compared with offspring of dams on a regular diet. The bronchoconstriction induced by 5-hydroxytriptamine was completely blocked by either vagotomy (Fig. 3B) or atropine (3 mg/kg, ip; data not shown), indicating that airway nerve-mediated reflex bronchoconstriction was responsible for the observed effect. Notably, maternal diet did not change baseline airway resistance (Fig. 3A), but it potentiated airway nerve-mediated reflex bronchoconstriction. No significant differences were observed between male and female offspring in terms of airway resistance, and the data from both sexes were combined in Fig. 3.

Airway Epithelial Innervation and Neuronal Substance P Expression in Offspring of Obese Mothers

Airway epithelial sensory nerves were visualized by immunostaining with an antibody against the pan-neuronal marker PGP9.5 (Fig. 3, C and D), and three-dimensional modeling (Fig. 3, G and H). In the airway epithelium, both the length of sensory nerves (Fig. 3K) and the number of nerve branch points (Fig. 3L) were significantly decreased in 1-day-old offspring of dams on a high-fat diet versus offspring of dams on a regular diet. This decreased density of nerves indicates that intrauterine exposure to maternal high-fat diet suppresses the development of airway sensory nerves. However, by 16 wk of age, both length (Fig. 3O) and branching (Fig. 3P) were significantly increased in offspring of dams on a high-fat diet versus offspring of dams on a regular diet.

To investigate whether uterine exposure to a high-fat diet changed the expression of sensory substance P, a neuropeptide known to induce bronchoconstriction and associated with asthma severity, neuronal expression of substance P was identified by colocalizing the neurotransmitter substance P with the pan-neuronal marker PGP9.5 (Fig. 3, E and F). To normalize the substance P expression to the number of neurons, the ratio of substance P voxels to PGP9.5 voxels was calculated (Fig. 3, I and J). Immediately after birth, neither the total amount of measured neuronal substance P expression (Fig. 3M) nor the ratio of substance P to PGP9.5 (Fig. 3N) was significantly changed by maternal high-fat diet or regular diet. However, by 16 wk of age, neuronal substance P was significantly increased in offspring of dams on a high-fat diet versus regular diet (Fig. 3Q). Furthermore, the ratio of substance P to PGP9.5 was also significantly increased in offspring of dams on a high-fat diet versus offspring of dams on a regular diet (Fig. 3R).

DISCUSSION

Our study, which uses a mouse model of maternal high-fat diet-induced obesity, adds to the growing body of evidence showing that maternal high-fat diet exposure can increase the risk of asthma in offspring. Specifically, we found that maternal high-fat diet increases circulating insulin, airway epithelial sensory innervation, and reflex bronchoconstriction in offspring even when they were fed a regular diet only. Previous findings in adult animals have shown that hyperinsulinemia can increase airway nerve-mediated bronchoconstriction through increased sensory innervation and increased parasympathetic nerve activity (12, 22, 23, 30). Hyperinsulinemia promotes nerve growth, as insulin at physiological levels directly affects sensory neurons by promoting axon growth and regeneration (31). Furthermore, we confirmed that hyperinsulinemia induces airway epithelial sensory hyperinnervation through signaling pathways activated by insulin receptors on sensory nerves (30). In addition, hyperinsulinemia alters parasympathetic control of lung function by reducing M2 receptor expression, as observed in vas deferens and atrial cardiomyocytes (32, 33), thereby suppressing M2 receptor function on parasympathetic nerves (12, 34). Therefore, increased circulating insulin can affect both airway sensory nerves and parasympathetic nerves, ultimately leading to an increase in airway nerve-mediated reflex bronchoconstriction, which has also been shown as a key pathogenic mechanism of asthma in both human and animal models. Hence, our results, along with previous studies, suggest a potential mechanism by which maternal obesity may contribute to the development of asthma in offspring.

Our data confirm that hyperresponsiveness to 5-HT in offspring exposed to intrauterine obesity is mediated by a neural reflex, which may be increased by changes in both sensory nerves and parasympathetic nerves. Our data show that maternal high-fat diet exposure increased the density of sensory nerves at airway epithelium. These heightened sensory nerves are capable of detecting stimuli such as airway stretch or chemicals, thereby enabling them to transmit stronger signals to the central nervous system. Consequently, this leads to an increased activation of the parasympathetic nerves. Parasympathetic nerves control airway tone (35) and mediate bronchoconstriction through the release of acetylcholine (9, 36–39). Acetylcholine also activates prejunctional inhibitory M2 muscarinic receptors (1, 8, 15). Loss of function or expression of M2 receptors increases acetylcholine release and reflex bronchoconstriction. Furthermore, airway epithelial sensory innervation is markedly increased in patients with severe asthma with increased expression of substance P (15), a neuropeptide known to increase sensory nerve sensitivity in inflammatory and pain models (40, 41). Here we found that maternal high-fat diet exposure increased sensory nerves expressing substance P in the airway epithelium of offspring at 16 wk of age. The increased substance P can either directly bind to neurokinin-1 (NK1) receptors on airway smooth muscle (42) or indirectly potentiate nerve function through neurogenic inflammation (43), to contribute to an increase of neural reflex bronchoconstriction which was observed in the offspring of high-fat diet-fed dam.

The hyperinnervation of airway epithelial sensory nerves in offspring at 16 wk of age is unlikely due to changes during embryonic development, given that intrauterine exposure to maternal high-fat diet delayed airway sensory nerve development in 1-day-old offspring. Maternal obesity induced by high-fat diet can lead to several factors that interfere with the growth and development of nervous systems, resulting in reduced innervations. For instance, high-fat diet can increase oxidative stress in the body, including in the placenta and fetal tissues, which can damage nerve cells and interfere with their growth. Micronutrition in maternal diet also contributes to the growth, myelination, and overall health of nerves in the developing fetus. Studies have shown the significant roles of neurotrophic B vitamins, such as vitamin B1 (thiamine), vitamin B6 (pyridoxine), and vitamin B12, in neuronal metabolism and neuronal excitability (44). In addition, vitamin E has been found to interact with lipid peroxidation and prevents defects during neural differentiation (45). Although our study observed differences in micronutrient levels between the high-fat diet (HFD) and the control diet, it is important to note that our study has limitations, and therefore, the impact of micronutrition on nerve development cannot be definitively ruled out or confirmed. Further research beyond the scope of this study is needed to investigate and verify this relationship. Moreover, maternal obesity can cause chronic inflammation and hormonal changes, further affecting nervous system development. Epigenetic changes may also negatively impact innervation. To investigate these mechanisms, further studies are needed in the future. Nonetheless, this study provides valuable insights into the potential impact of maternal nutrition on fetal and neonatal peripheral neural system development, highlighting the need for continued research in this area.

Our findings reveal that maternal high-fat diet exposure increases circulating insulin levels in adult offspring, which could underlie the increased risk of asthma (16, 46). Two human cross-sectional studies show a positive correlation between high insulin levels and asthma severity (47), and decreased lung function (19, 20). Animal studies have also demonstrated that increased insulin levels can reduce the expression (32, 33) and function of the M2 muscarinic receptor on parasympathetic nerves (12), thereby potentiating nerve-mediated bronchoconstriction. Reducing circulating insulin levels by suppressing insulin release with streptozotocin (12, 22, 23) or treating with antidiabetic drugs (22, 23) has been shown to prevent nerve-mediated hyperresponsiveness in obese animals. Replacing insulin in streptozotocin-treated rats restores nerve-mediated hyperresponsiveness (12, 48). In addition, insulin has neurotrophic effects (49) that can cause hyperinnervation of airway epithelial sensory nerves and enhanced expression of neural substance P in this study (Fig. 3, C–N), leading to increased reflex bronchoconstriction (Fig. 2, A and B). Selectively depleting insulin receptors on airway sensory nerves has been shown to prevent hyperinsulinemia-induced sensory hyperinnervation and reflex hyperresponsiveness in hyperinsulinemic animals (30). Therefore, the development of hyperinsulinemia in the offspring of obese dams (Fig. 2) may represent a mechanism by which maternal obesity contributes to the development of asthma in offspring.

Obesity is one of the most pressing public health challenges of the 21st century. Shockingly, the prevalence of prepregnancy obesity in the United States rose to 29% in 2019 (2). Of particular concern is that the effects of maternal obesity do not simply target one generation; the increased nutrient abundance experienced by the fetus of an overnourished mother is the basis of the intergenerational cycle of obesity, which is linked to a wide range of negative health outcomes in offspring, including an increased risk of asthma. Our data suggest that control of maternal diet and maternal prepregnancy and gestational weight gain may prevent asthma in offspring. In addition, as sensory nerve density increases postbirth, there may be a window of opportunity to limit sensory nerve development in offspring and limit their risk of developing asthma. Overall, our findings highlight the need for continued efforts to address the issue of maternal obesity and its impact on offspring health.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

GRANTS

Financial support for this work was provided by the National Institutes of Health—National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Grants HL163087 (to Z.N.), HL164474 (to Z.N.), and HL131525 (to A.D.F.); National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Grant AI152498 (to D.B.J.); NHLBI Grants HL144008 (to D.B.J.) and F30HL154526 (to G.N.C.); and National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant HD099367 (to A.M.).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.B.J., A.D.F., A.M., and Z.N. conceived and designed research; G.N.C., Y.J.A., K.R.W., and Z.N. performed experiments; G.N.C., K.R.W., A.M., and Z.N. analyzed data; G.N.C., A.M., and Z.N. interpreted results of experiments; G.N.C., A.M., and Z.N. prepared figures; A.M. and Z.N. drafted manuscript; D.B.J., A.D.F., A.M., and Z.N. edited and revised manuscript; G.N.C., Y.J.A., K.R.W., D.B.J., A.D.F., A.M., and Z.N. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the technical assistance provided by Elysse Phillips, Matthew Bucher, and Jessica Maung in conducting experiments and collecting data; Dr. Daniel Marks and Dr. Xinxia Zhu for support in measuring animals’ body composition; and Dr. Stefanie Kaech Petrie and Dr. Brian Jenkins for technical assistance in imaging and modeling. Their invaluable contributions were essential for the successful completion of this study. Graphical abstract image created with BioRender.com and published with permission.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight [2021 Jun 9].

- 2. Driscoll AK, Gregory ECW. Increases in prepregnancy obesity: United States, 2016-2019. NCHS Data Brief (392): 1–8, 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Reichetzeder C. Overweight and obesity in pregnancy: their impact on epigenetics. Eur J Clin Nutr 75: 1710–1722, 2021. doi: 10.1038/s41430-021-00905-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Forno E, Young OM, Kumar R, Simhan H, Celedón JC. Maternal obesity in pregnancy, gestational weight gain, and risk of childhood asthma. Pediatrics 134: e535–e546, 2014. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rizzo GS, Sen S. Maternal obesity and immune dysregulation in mother and infant: A review of the evidence. Paediatr Respir Rev 16: 251–257, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rosenquist NA, Richards M, Ferber JR, Li DK, Ryu SY, Burkin H, Strickland MJ, Darrow LA. Prepregnancy body mass index and risk of childhood asthma. Allergy 78: 1234–1244, 2023. doi: 10.1111/all.15598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rastogi D. Epigenetics of asthma-the field continues to evolve. Ann Transl Med 10: 1190, 2022. doi: 10.21037/atm-22-5022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Drake MG, Lebold KM, Roth-Carter QR, Pincus AB, Blum ED, Proskocil BJ, Jacoby DB, Fryer AD, Nie Z. Eosinophil and airway nerve interactions in asthma. J Leukoc Biol 104: 61–67, 2018. doi: 10.1002/JLB.3MR1117-426R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fryer AD, Maclagan J. Muscarinic inhibitory receptors in pulmonary parasympathetic nerves in the guinea-pig. Br J Pharmacol 83: 973–978, 1984. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1984.tb16539.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nie Z, Scott GD, Weis PD, Itakura A, Fryer AD, Jacoby DB. Role of TNF-α in virus-induced airway hyperresponsiveness and neuronal M2 muscarinic receptor dysfunction. Br J Pharmacol 164: 444–452, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01393.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yost BL, Gleich GJ, Fryer AD. Ozone-induced hyperresponsiveness and blockade of M2 muscarinic receptors by eosinophil major basic protein. J Appl Physiol (1985) 87: 1272–1278, 1999. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.4.1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nie Z, Jacoby DB, Fryer AD. Hyperinsulinemia potentiates airway responsiveness to parasympathetic nerve stimulation in obese rats. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 51: 251–261, 2014. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0452OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Crimi N, Palermo F, Oliveri R, Polosa R, Settinieri I, Mistretta A. Protective effects of inhaled ipratropium bromide on bronchoconstriction induced by adenosine and methacholine in asthma. Eur Respir J 5: 560–565, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Makker HK, Holgate ST. The contribution of neurogenic reflexes to hypertonic saline-induced bronchoconstriction in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 92: 82–88, 1993. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(93)90041-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Drake MG, Scott GD, Blum ED, Lebold KM, Nie Z, Lee JJ, Fryer AD, Costello RW, Jacoby DB. Eosinophils increase airway sensory nerve density in mice and in human asthma. Sci Transl Med 10: eaar8477, 2018. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aar8477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cardet JC, Ash S, Kusa T, Camargo CA Jr, Israel E. Insulin resistance modifies the association between obesity and current asthma in adults. Eur Respir J 48: 403–410, 2016. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00246-2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Carr TF, Stern DA, Morgan W, Guerra S, Martinez FD. Elevated childhood insulin-related asthma is a risk factor for reduced lung function. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 207: 790–792, 2023. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202209-1654LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Peters MC, Schiebler ML, Cardet JC, Johansson MW, Sorkness R, DeBoer MD, Bleecker ER, Meyers DA, Castro M, Sumino K, Erzurum SC, Tattersall MC, Zein JG, Hastie AT, Moore W, Levy BD, Israel E, Phillips BR, Mauger DT, Wenzel SE, Fajt ML, Koliwad SK, Denlinger LC, Woodruff PG, Jarjour NN, Fahy JV; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Severe Asthma Research Program-3. The impact of insulin resistance on loss of lung function and response to treatment in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 206: 1096–1106, 2022. [Erratum in Am J Respir Crit Care Med 207: 636, 2023]. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202112-2745OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kim KM, Kim SS, Lee SH, Song WJ, Chang YS, Min KU, Cho SH. Association of insulin resistance with bronchial hyperreactivity. Asia Pac Allergy 4: 99–105, 2014. doi: 10.5415/apallergy.2014.4.2.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mudaliar S, Henry RR. Inhaled insulin in patients with asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Diabetes Technol Ther 9, Suppl l: S83–S92, 2007. doi: 10.1089/dia.2007.0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mingrone G, Manco M, Mora ME, Guidone C, Iaconelli A, Gniuli D, Leccesi L, Chiellini C, Ghirlanda G. Influence of maternal obesity on insulin sensitivity and secretion in offspring. Diabetes Care 31: 1872–1876, 2008. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Calco GN, Proskocil BJ, Jacoby DB, Fryer AD, Nie Z. Metformin prevents airway hyperreactivity in rats with dietary obesity. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 321: L1105–L1118, 2021. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00202.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Proskocil BJ, Fryer AD, Jacoby DB, Nie Z. Pioglitazone prevents obesity-related airway hyperreactivity and neuronal M2 receptor dysfunction. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 321: L236–L247, 2021. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00567.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Montaniel KRC, Bucher M, Phillips EA, Li C, Sullivan EL, Kievit P, Rugonyi S, Nathanielsz PW, Maloyan A. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibition delays developmental programming of obesity and metabolic disease in male offspring of obese mothers. J Dev Orig Health Dis 13: 727–740, 2022. doi: 10.1017/S2040174422000010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nie Z, Maung JN, Jacoby DB, Fryer AD. Lung eosinophils increase vagus nerve-mediated airway reflex bronchoconstriction in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 318: L242–L251, 2020. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00040.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Scott GD, Blum ED, Fryer AD, Jacoby DB. Tissue optical clearing, three-dimensional imaging, and computer morphometry in whole mouse lungs and human airways. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 51: 43–55, 2014. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0284OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Scott GD, Fryer AD, Jacoby DB. Quantifying nerve architecture in murine and human airways using three-dimensional computational mapping. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 48: 10–16, 2013. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0290MA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Li W, Germain RN, Gerner MY. Multiplex, quantitative cellular analysis in large tissue volumes with clearing-enhanced 3D microscopy (Ce3D). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114: E7321–E7330, 2017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1708981114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bucher M, Montaniel KRC, Myatt L, Weintraub S, Tavori H, Maloyan A. Dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and impairment of placental metabolism in the offspring of obese mothers. J Dev Orig Health Dis 12: 738–747, 2021. doi: 10.1017/S2040174420001026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Calco GN, Maung JN, Jacoby DB, Fryer AD, Nie Z. Insulin increases sensory nerve density and reflex bronchoconstriction in obese mice. JCI Insight 7: e161898, 2022. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.161898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Recio-Pinto E, Rechler MM, Ishii DN. Effects of insulin, insulin-like growth factor-II, and nerve growth factor on neurite formation and survival in cultured sympathetic and sensory neurons. J Neurosci 6: 1211–1219, 1986. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-05-01211.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kamai T, Fukumoto Y, Gousse A, Yoshida M, Davenport TA, Weiss RM, Latifpour J. Diabetes-induced alterations in the properties of muscarinic cholinergic receptors in rat vas deferens. J Urol 152: 1017–1021, 1994. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)32646-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pathak A, Smih F, Galinier M, Verwaerde P, Rouet P, Philip-Couderc P, Montastruc JL, Senard JM. Insulin downregulates M(2)-muscarinic receptors in adult rat atrial cardiomyocytes: a link between obesity and cardiovascular complications. Int J Obes (Lond) 29: 176–182, 2005. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Belmonte KE, Jacoby DB, Fryer AD. Increased function of inhibitory neuronal M2 muscarinic receptors in diabetic rat lungs. Br J Pharmacol 121: 1287–1294, 1997. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Canning BJ. Reflex regulation of airway smooth muscle tone. J Appl Physiol (1985) 101: 971–985, 2006. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00313.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hahn HL, Graf PD, Nadel JA. Effect of vagal tone on airway diameters and on lung volume in anesthetized dogs. J Appl Physiol 41: 581–589, 1976. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1976.41.4.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jacoby DB, Fryer AD. Abnormalities in neural control of smooth muscle in virus-infected airways. Trends Pharmacol Sci 11: 393–395, 1990. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(90)90141-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kistemaker LEM, Prakash YS. Airway innervation and plasticity in asthma. Physiology (Bethesda) 34: 283–298, 2019. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00050.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Undem BJ, Carr MJ. The role of nerves in asthma. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2: 159–165, 2002. doi: 10.1007/s11882-002-0011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Abbadie C, Trafton J, Liu H, Mantyh PW, Basbaum AI. Inflammation increases the distribution of dorsal horn neurons that internalize the neurokinin-1 receptor in response to noxious and non-noxious stimulation. J Neurosci 17: 8049–8060, 1997. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-20-08049.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sahbaie P, Shi X, Guo TZ, Qiao Y, Yeomans DC, Kingery WS, Clark DJ. Role of substance P signaling in enhanced nociceptive sensitization and local cytokine production after incision. Pain 145: 341–349, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Maghni K, Michoud MC, Alles M, Rubin A, Govindaraju V, Meloche C, Martin JG. Airway smooth muscle cells express functional neurokinin-1 receptors and the nerve-derived preprotachykinin-a gene: regulation by passive sensitization. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 28: 103–110, 2003. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.4635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Joos GF, Germonpré PR, Pauwels RA. Role of tachykinins in asthma. Allergy 55: 321–337, 2000. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2000.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Calderón-Ospina CA, Nava-Mesa MO. B Vitamins in the nervous system: Current knowledge of the biochemical modes of action and synergies of thiamine, pyridoxine, and cobalamin. CNS Neurosci Ther 26: 5–13, 2020. doi: 10.1111/cns.13207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Traber MG. Vitamin E: necessary nutrient for neural development and cognitive function. Proc Nutr Soc 80: 319–326, 2021. doi: 10.1017/S0029665121000914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Leiria LO, Martins MA, Saad MJ. Obesity and asthma: beyond T(H)2 inflammation. Metabolism 64: 172–181, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Morishita R, Franco Mdo C, Suano-Souza FI, Solé D, Puccini RF, Strufaldi MW. Body mass index, adipokines and insulin resistance in asthmatic children and adolescents. J Asthma 53: 478–484, 2016. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2015.1113544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Belmonte KE, Fryer AD, Costello RW. Role of insulin in antigen-induced airway eosinophilia and neuronal M2 muscarinic receptor dysfunction. J Appl Physiol (1985) 85: 1708–1718, 1998. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.5.1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Heni M, Hennige AM, Peter A, Siegel-Axel D, Ordelheide AM, Krebs N, Machicao F, Fritsche A, Häring HU, Staiger H. Insulin promotes glycogen storage and cell proliferation in primary human astrocytes. PLoS One 6: e21594, 2011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.