Abstract

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to wide-ranging disruption of head–neck cancer (HNC) service provision in the UK. Early reports suggest delays in referral, diagnosis and initiation of treatment for new cancer cases compared with before the pandemic.

Methods

The HNC service was studied retrospectively for the time-periods between 1 January 2020 to 31 October 2020 (hereafter ‘post-COVID’) and 1 January 2019 to 31 October 2019 (hereafter ‘pre-COVID’). We analysed: (1) the number of cases treated at our centre, (2) stage of disease at presentation and (3) treatment delivery times.

Results

In the post-COVID period, the total number of HNC cases treated decreased (48 vs 56 pre-COVID). There was increase in advanced stage at presentation (58% vs 42% pre-COVID) and a significant increase in the need for airway stabilisation (13 vs 5 pre-COVID; p=0.03). Average time from referral to treatment was significantly prolonged (72.5 days vs 49.23 days pre-COVID; p=0.03). Two-week wait referrals were seen in HNC clinics at median time of 11.9 days, compared with 7.1 days during the pre-COVID period (p=0.07). However, there was no delay in the initiation of first treatment after the decision to treat (29.2 days vs 24.7 days pre-COVID; p=0.58).

Conclusion

The results of this study call for early referral at the primary care level and rapid radiopathological confirmation at the tertiary level to prevent delays in diagnosis of new HNC cases.

Keywords: Head and neck neoplasms, COVID-19, Time-to-treatment, Early detection of cancer, Referral and consultation

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to wide-ranging disruption of head–neck cancer (HNC) service provision in the UK. This was brought on by a multitude of changes, in both primary and tertiary care settings. Hospitals witnessed a temporary halt in elective procedures, lack of intensive care beds, staff absences due to illness/self-isolation and partial adoption of teleclinics by specialist services.1 In the community, there was cessation of face-to-face consultations by general practitioners (GPs), and patients were sheltered from routine healthcare owing to self-isolation and due to concerns for their safety in attending hospital.2 The presumed higher risk of COVID-19 transmission among head–neck clinicians, due to higher viral loads in the upper aerodigestive tract and regular use of aerosol-generative procedures, curtailed full head and neck examination in low-risk patients.

These factors have had a cumulative effect, with significant delays in presentation to specialist clinics, oncological diagnosis and initiation of definitive treatment. Early reports suggest delays in referral, diagnosis and initiation of treatment for new cancer cases compared with before the pandemic. However, there is limited evidence for such reports, with many of them being clinician-reported questionnaires.3 We aimed to objectively assess impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the HNC referral pathway in North East London.

Methods

This study was conducted in the department of ear, nose and throat and head–neck surgery at the Royal London Hospital, London. This is a tertiary referral centre for HNC in North East London. The aims of this study were to assess the effect of the current COVID-19 pandemic on our HNC service, specifically on the following:

-

•

the number of head–neck cases treated at our centre;

-

•

the stage of disease at presentation;

-

•

treatment delivery times.

We defined two periods:

-

•

post-COVID (1 January 2020 to 31 October 2020); and

-

•

pre-COVID (1 January 2019 to 31 October 2019).

Inclusion criteria were as follows:

-

•

newly diagnosed primary cancers involving oropharynx, salivary glands, larynx, hypopharynx and carcinoma of unknown primary;

-

•

date of referral to the head–neck service after 1 January in each period;

-

•

received at least surgical/oncological treatment or both at our centre.

Data collection involved retrospective review of multidisciplinary team (MDT) discussion outcomes and electronic hospital records for demographic data, details of referral (from GP, accident and emergency department [A&E] or other trusts) and relevant dates, such as date of initial referral, date of first clinic encounter, date of decision to treat (DDT) and date of first treatment (DFT) from referral. Tumour (T) stage (according to the 8th AJCC TNM staging) and need for an airway stabilisation procedure were used independently as proxies for stage of presentation. T3 and T4 tumours were grouped as advanced stage, whereas T1 and T2 tumours were classified as non-advanced stage. Tracheostomy or microlaryngoscopic laser debulking done before definitive treatment to secure the airway were considered as airway stabilisation procedures. Treatment delivery times were measured in accordance with the guidelines set out by the NHS Constitution (2016). NHS England defines maximum waiting times of 14 days for specialist review after urgent cancer referral, 31 days from receiving diagnosis to first definitive treatment and 62 days for beginning first definitive treatment following urgent referral.4

Cases in which the MDT decision was for best supportive care were excluded from our analysis of treatment delivery times. Carcinoma of unknown primary cases were excluded from analysis for stage at presentation. Data analysis was done using RStudio v.1.3.1093 (© 2009–2020 RStudio, PBC). Welch’s t test was utilised for numerical variables and the chi-squared test was utilised for categorical variables. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Number of head and neck cancer cases

Pre-COVID

A total of 56 cases received first definitive treatment at our centre in the pre-COVID period. These cases were referred to our service via other trusts (47%), GPs (42%) or presented directly to A&E (11%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1 .

New head–neck cancer cases treated at our centre in the pre-COVID and post-COVID periods and their route of referral

Post-COVID

A total of 48 cases received first definitive treatment at our service in the post-COVID period. These cases were referred to our service predominantly by GPs (60%), followed by other trusts (33%); three cases presented directly to A&E (6%).

Stage of presentation

Pre-COVID

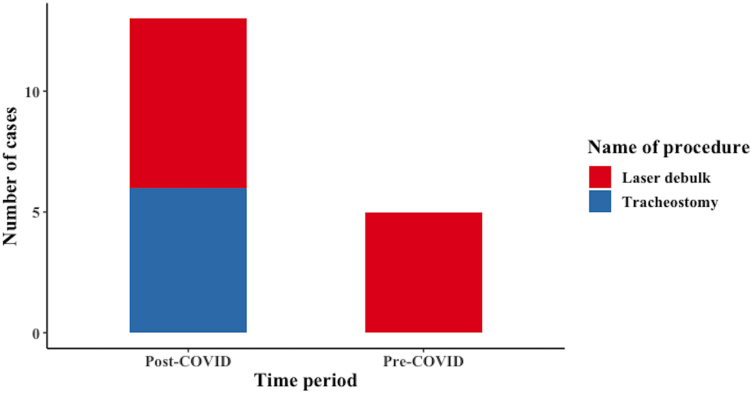

Twenty-nine cases (58%) were non-advanced stage in this period, with 21 cases (42%) advanced stage (excluding 6 cases of unknown primary). Among the 56 presenting cases, 5 patients needed airway stabilisation in the form of laser debulk (Figure 2).

Figure 2 .

Airway stabilisation procedures required before definitive treatment in the pre-COVID and post-COVID periods

Post-COVID

Nineteen cases (43%) belonged to non-advanced stage, whereas 25 cases (57%) had advanced stage (excluding 4 cases of unknown primary). Among the 48 patients, 13 patients needed airway stabilisation (seven laser debulk and six tracheostomy). The increase in airway stabilisation procedures, compared with the pre-COVID period, was statistically significant (p=0.032).

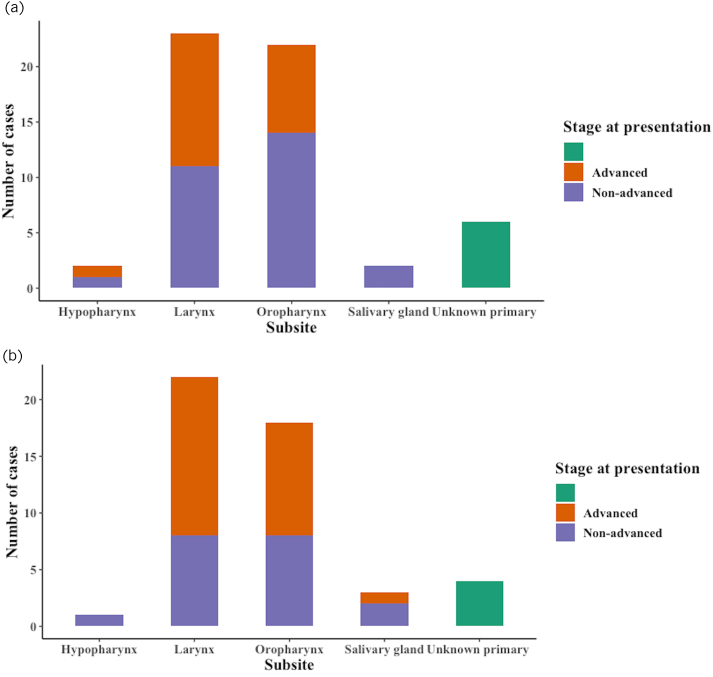

By tumour subsite

The percentage of advanced stage cancers in each tumour subsite was assessed for both periods (Figure 3). There was an increase in the proportion of advanced tumours in the oropharynx, larynx and salivary glands (p=0.35). There were no advanced hypopharynx cases in 2020, whereas 50% of cases were advanced pre-COVID.

Figure 3 .

(a) New head–neck cancer cases in the pre-COVID (a) and post-COVID (b) periods by subsite and T stage at presentation.

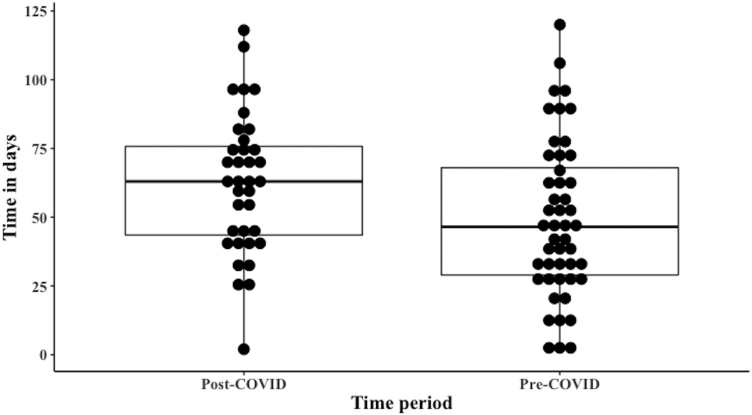

Treatment delivery times

Pre-COVID

The two-week wait (2ww) referral took 7.1 days (median) for the first clinic encounter (interquartile range [IQR]=6.0). The median time taken from DDT to DFT was 24.7 days (IQR=20.0). Among the 56 cases, 26.6% defaulted the 31-day maximum wait time. The median referral to treatment time was 49.23 days (IQR=39.0). The 61-day maximum wait time was defaulted in 28.8% cases (Figure 4).

Figure 4 .

Modified boxplot depicting the distribution of time taken for the first clinic encounter since referral during the pre-COVID and post-COVID periods. For pre-COVID, median value was 7.1 days and interquartile range was 6.0. For post-COVID, median value was 11.9 days and interquartile range was 6.0.

Post-COVID

The 2ww referrals took 11.9 days (median) for the first face-to-face/virtual clinic encounter (IQR=6.0). This delay, compared with pre-COVID, was not statistically significant (p=0.068). The median time taken from DDT to DFT was 29.2 days (IQR=15.0; p=0.58). Among the 48 cases, 28.2% defaulted the 31-day maximum wait time. The median referral to treatment time was 72.5 days (IQR=37.5) (Figure 5).

Figure 5 .

Modified boxplot depicting the distribution of time taken for the first treatment since decision to treat during the pre-COVID and post-COVID periods. For pre-COVID, median value was 24.7 days and interquartile range was 20.0. For post-COVID, median value was 29.2 days and interquartile range was 15.0.

Compared with pre-COVID, this was statistically significant (p=0.027). The 61-day maximum wait time was defaulted in 55.5% cases (Figure 6).

Figure 6 .

Modified boxplot depicting the distribution of time taken for the first treatment since referral during the pre-COVID and post-COVID periods. For pre-COVID, median value was 49.23 days and interquartile range was 39.0. For post-COVID, median value was 72.5 days and interquartile range was 37.5.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has presented a challenge of an unprecedented magnitude that neither the world nor our health services were prepared for. During the 1918 influenza pandemic, there were three separate waves, with the second in autumn 1918 being responsible for most deaths.5 Therefore, we may not have seen the worst effects of this both with the immediate and long-term effects of the pandemic lingering for the next decade.6 Substantial increases in cancer deaths are to be expected as a result of diagnostic delays due to the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK, as reported by Maringe et al.7

As our study has shown, there were significant delays in initial presentation as well as delays in confirmation of the diagnosis. There was a decrease8 in new cancer referrals to our centre during the COVID-19 period. Overall across NHS England, urgent HNC referrals fell by 23% between March and August 2020 compared with 2019.2 These findings have been reported across other specialties in the UK, with the lowest number of referrals around April–May 2020.8 We noticed a change in the trend of cancer referrals to our centre, which was previously mainly via other trusts, with GPs referring 60% of patients via the 2ww pathway. This is possibly due to patients being reviewed remotely by GPs, without clinical examination, resulting in a lower threshold for early referral. This practice led to an incidental increase in benign disease being diagnosed at 2ww clinic during the pandemic in the study by Taylor et al.9

It is likely that we were seeing more advanced cancers as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Data from Macmillan Cancer Support report that, over the pandemic, more than 3% of patients living with cancer in the UK did not access GP or other healthcare despite worsening of symptoms owing to a fear of coronavirus infection or because they did not want to add pressure to the NHS.2 In 2020, over half of the newly diagnosed HNC cases at our centre were either T3 or T4 stage. This is a dramatic increase in advanced cancers, compared with 42% in 2019. Park et al reported a significant increase in stage III/IV non-small cell lung cancer during the pandemic.10 This argument is further ratified by a statistically significant increase in the need for airway stabilisation procedures in the COVID pandemic among HNC cases. The need for preoperative tracheostomy in laryngectomy patients is a significant adverse prognostic indicator.11,12 Batra et al reported an increase in preoperative tracheostomies for HNC during the pandemic.13

We found that there was no significant delay in the initiation of first treatment after the decision to treat (usually at the MDT meeting). Similarly, Gathani et al reported average high consistent delivery of first treatment within 31 days for breast cancer in the first 6 month of the pandemic.8 On analysis, the predominant delay in our cancer provision was in establishing the diagnosis. According to NHS Diagnostic Waiting Times and Activity Data, the proportion of patients waiting for 6 weeks or more from referral for a key diagnostic test at the end of a month rose from 2.8% in February 2020 to 38.1% in August 2020, peaking in May 2020 at 58.5%.14 Compared with August 2019, the proportion of patients waiting 6 weeks or more for imaging studies (magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography non-obstetric ultrasound) increased by 25.1%–25.7% in August 2020. Fluctuations in the availability of theatres and need to prioritise advanced over early cancer also contributed to the delay in confirmation of histology and the final decision to treat.

This calls for early referral at the primary care level and rapid radiopathological confirmation at the tertiary level. We recommend a low threshold for ultrasound imaging of neck lumps at primary care (preferably at the time of 2ww referral), use of minimally invasive techniques, such as fine-needle aspiration cytology of neck nodes, to confirm diagnosis and early referral to head–neck MDT to initiate treatment and conversation regarding its modalities. Routine or follow-up appointments at the specialist HNC clinic could be done remotely, with face-to-face reviews only for suspicious findings.15 Use of risk stratification tools may help reduce the waiting periods for specialist clinics as well as for imaging studies.16 We followed the North East London Covid-19 Protocol for diagnostics in 2ww HNC pathway, helping to focus resources at moderate/high-risk patients.17 It is essential to ensure rapid and effective management of HNC while reducing risk of COVID-19 transmission to patient and clinician.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought about a major overhaul in the HNC referral pathway. We studied the impact of the pandemic on the referral and treatment pathways for new HNC in North East London. The absolute number of new cancer diagnoses fell by a small margin. Most of the referrals were from primary care, and fewer from other trusts or A&E. The tumour stage at presentation was advanced in the majority of cases, with 13/48 cases requiring airway stabilisation procedure before definitive treatment, which was a statistically significant increase. Treatment delivery times were prolonged, with statistically significant delays in time taken from date of referral to first treatment. However, time taken from diagnosis to first treatment was not significantly prolonged. These parameters need to be studied on a larger scale to assess the full impact of the pandemic on HNC patients and ensure that the long-term effects are minimised.

Author contributions

Mr A Zubair takes responsibility for the integrity of the content of the paper.

References

- 1.Lee AKF, Cho RHW, Lau EHLet al. Mitigation of head and neck cancer service disruption during COVID-19 in Hong Kong through telehealth and multiinstitutional collaboration. Head Neck 2020 Jul; 42: 1454–1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Forgotten “C”? The impact of COVID-19 on cancer care. Macmillan Cancer Support.

- 3.Chazan G, Franchini F, Alexander Met al. Impact of COVID-19 on cancer service delivery: results from an international survey of oncology clinicians. ESMO Open 2020; 5: e001090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Cancer Waiting Times Monitoring Dataset Guidance – Version 11.0. NHS England. Publications Ref No: B0065. https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2020/09/national-cancer-waiting-times-monitoring-dataset-guidance-v11-sep2020.pdf (cited July 2023).

- 5.1918 Pandemic Influenza: Three Waves | Pandemic Influenza (Flu) | CDC. 2018.

- 6.Han AY, Miller JE, Long JL, St John MA. Time for a paradigm shift in head and neck cancer management during the COVID-19 pandemic. Otolaryngol Neck Surg 2020; 163: 447–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maringe C, Spicer J, Morris Met al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer deaths due to delays in diagnosis in England, UK: a national, population-based, modelling study. Lancet Oncol 2020; 21: 1023–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gathani T, Clayton G, MacInnes E, Horgan K. The COVID-19 pandemic and impact on breast cancer diagnoses: what happened in England in the first half of 2020. Br J Cancer 2021; 124: 710–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor R, Omakobia E, Sood S, Glore RJ. The impact of coronavirus disease 2019 on head and neck cancer services: a UK tertiary centre study. J Laryngol Otol 2020; 134: 684–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park JY, Lee YJ, Kim Tet al. Collateral effects of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on lung cancer diagnosis in Korea. BMC Cancer 2020; 20: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basheeth N, O'Leary G, Khan H, Sheahan P. Oncologic outcomes of total laryngectomy: impact of margins and preoperative tracheostomy. Head Neck 2015; 37: 862–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang J, Zhu X, Zeng Wet al. Which risk factors are associated with stomal recurrence after total laryngectomy for laryngeal cancer? A meta-analysis of the last 30 years. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 2020; 86: 502–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Batra TK, Tilak MR, Pai Eet al. Increased tracheostomy rates in head and neck cancer surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2021; 50: 989–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monthly Diagnostic Waiting Times and Activity Report. NHS England. https://www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/wpcontent/uploads/sites/2/2020/10/DWTA-Report-August-2020_o1lg9.pdf (cited July 2023).

- 15.Mehanna H, Hardman JC, Shenson JAet al. Recommendations for head and neck surgical oncology practice in a setting of acute severe resource constraint during the COVID-19 pandemic: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol 2020; 21: e350–e359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tikka T, Kavanagh K, Lowit Aet al. Head and neck cancer risk calculator (HaNC-RC)-V.2 – Adjustments and addition of symptoms and social history factors. Clin Otolaryngol 2020; 45: 380–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warner E, Scholfield DW, Adams Aet al. North East London coronavirus disease 2019 protocol for diagnostics in two-week wait head and neck cancer patients. J Laryngol Otol 2020; 134: 680–683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]