Abstract

Phosphorus (Pi) deficiency is a major factor of limiting plant growth. Using Phosphate-solubilizing microorganism (PSM) in synergy with plant root system which supply soluble Pi to plants is an environmentally friendly and efficient way to utilize Pi. Trichoderma viride (T. viride) is a biocontrol agent which able to solubilize soil nutrients, but little is known about its Pi solubilizing properties. The study used T. viride to inoculate Melilotus officinalis (M. officinalis) under different Pi levels and in order to investigate the effect on Pi absorption and growth of seedlings. The results found that T. viride could not only solubilizate insoluble inorganic Pi but also mineralize insoluble organic Pi. In addition, the ability of mineralization to insoluble organic Pi is more stronger. Under different Pi levels, inoculation of T. viride showed that promoted the growth of aboveground parts of seedlings and regulated the morphology of roots, thus increasing the dry weight of seedlings. The effect of T. viride on seedling growth was also reflected the increasing of chlorophyll fluorescence parameters and photosynthetic pigment content. Moreover, compared to the uninoculated treatments, inoculation of T. viride also enhanced Pi content in seedlings. Thus, the T. viride was a beneficial fungus for synergistic the plant Pi uptake and growth.

Subject terms: Biotechnology, Plant sciences

Introduction

Pi is an essential plant macronutrient required for growth and development1, which plays many key roles in plant life such as synthesis of nucleotides, composition of membranes, photosynthesis, respiration, carbohydrate transport, etc2. The main form of Pi used by plants is ortho-phosphate, but it is very easy to form insoluble compounds with Fe3+, Al3+, Ca2+ and Mg2+ in terrestrial ecosystems, so its low availability often limits the growth of plants3. Pi limitation is the main productivity limiting factor in agricultural4,5 and grassland ecosystems6. Although the Pi deficiency in plants can be alleviated by applying soluble Pi fertilizer to plants, but the utilization rate of fertilizer is greatly reduced due to chemical fixation of Pi and agricultural runoff7. However, overuse of phosphate rock fertilizers can lead to eutrophication of water body and ultimately to environmental degradation. Some studies have shown that phosphate rock is a non-renewable resource, and phosphate reserves will be exhausted in 50–100 years8,9. Therefore, how plants use insoluble Pi in the soil is a hot issue at present.

Using PSMs as Pi biofertilizer has been reported to be an economical and environmentally friendly way to dissolve insoluble Pi in soils10. Phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms (PSMs) include phosphate-solubilizing bacteria (PSB) and phosphate-solubilizing fungi (PSF), normally PSF has higher phosphate-solubilizing activity11. In soil, PSB or PSF convert the insoluble Pi into soluble Pi for plant absorption and utilization by secreting organic acids and phosphatase12. PSMs have been shown to secrete phosphatases to hydrolyze organophosphorus in soil13. For example, the Bacillus subtilis strain KPS-11 could produce extracellular phytase to mineralize insoluble organophosphorus, which significantly promoted the absorption of insoluble organophosphorus in potatoes14. PSM is involved in solubilizing the insoluble inorganic Pi by producing organic acid e.g., gluconic, 2-ketogluconic acid, malic, lactic, acetic, citric, and succinic acid15–17. Some PSMs have two mechanisms at the same time, including Pi solubilization and Pi mineralization, but some PSMs have only one of them. For instance, Gomez-Ramirez et al.18 found that the Bacillus spp. strain IBUN-02724 had two mechanisms of Pi solubilization/mineralization at the same time, which not only was able to solubilize insoluble inorganic Pi from Ca3(PO4)2 and AlPO4, but also mineralize insoluble organic Pi from phytate.

PSMs are the main engine to promote the circulation of Pi between soil and plants12,19. In addition to its own Pi solubilizing characteristics, PSM can also regulate soil Pi uptake by plant roots through different mechanisms20. The interaction between PSM and plant can trigger the responsive mechanisms to control soil Pi flow to roots by regulating root exudation and root structure21. Moreover, PSM can affect the uptake and transport of soil Pi by plants through regulating the expression of plant Pi transporter protein genes22. Besides providing Pi for plant uptake, PSM promotes plant growth by producing beneficial metabolites23,24. In exchange, plants need to provide PSM with photosynthates for their growth25. However, a recent study by Clausing and Polle showed that some PSMs compete with plant roots for Pi in low Pi soils26. Moreover, Tian et al27 found that the addition of Pi fertilizer could inhibit the growth of some PSMs, such as Bacillales and Pseudomonadales. Thus, the application of PSM in agricultural production still needs a large number of experiments to screen and verify which is able to ensure the effect of increasing production.

Fungi of the genus Trichoderma belong to the phylum Ascomycota, subdivision Pezizomycotina, class Sordariomycetes, order Hypocreales and family Hipocreaceae28. Trichoderma spp. are common rhizosphere fungus which have been regarded as beneficial fungi due to the function of promoting the growth of plants and pathogen suppression ability29. Therefore, Trichoderma spp. are often used as biocontrol agents and biofertilizers to improve crop yields30. Trichoderma spp. have the function of promoting plant growth mainly because of the ability to dissolve nutrients from the soil, changing the root structure, secreting indoleacetic acid, cytokinin, gibberellin, gibberellins, and zeatin31,32. Recently, Zhang et al.33 observed that Trichoderma species could increase the activity of antioxidant enzyme in plants such as peroxidase, superoxide dismutase, and catalase, however, decrease the content of the hydrogen peroxide and the superoxide radical, which enhanced disease resistance of plants. Rudresh et al.34 reported that different species of Trichoderma were able to dissolve tricalcium phosphate (TCP) in vitro and in vivo, including Trichoderma viride, Trichoderma virens and Trichoderma harzianum. However, there have been few studies to conduct on the solubilization of insoluble Pi in soil by T. viride and the effect of interaction with plants on growth. In particular, studies on the promotion of insoluble organic Pi uptake to plants by T. viride are rarely reported. Therefore, it is necessary to clarify that T. viride has the property of solubilizing/mineralizing insoluble Pi. Here, we used T. viride to inoculate M. officinalis under insoluble Pi conditions. In the present study, we tried to answer the questions of whether T. viride dissolves/mineralizes insoluble Pi to supply M. officinalis with soluble Pi and the effect of T. viride on the physiological properties of M. officinalis.

Materials and methods

Cultivation of T. viride

The tested strain was T. viride, deposited in China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center (CGMCC; No.40034). The T. viride was placed on potato dextrose agar (PDA) culture medium and incubated at 28 °C in the dark for 7 d. The T. viride spores were flushed by sterile water which contained 0.01% Tween-80. The spore concentration was adjusted to 1 × 108 cfu·mL−1 with a haemocytometer.

Cultivation of seedlings

The seeds of M. officinalis were acquired from the Institute of Grassland Science of Northeast normal University, China. The seeds were soaked in 75% ethanol for 3 min, and followed by 2% NaOCl for 10 min with agitation. Then, sterilized seeds were germinated in plastic square pots (20 cm length × 15 cm width × 12 cm high) containing sterilized vermiculite as a substrate. Each pot contains 18 seedlings was poured 300 mL of 1/2 strength Hoagland nutrient solution every 3 days. The 1/2 strength Hoagland nutrient solution consisting of 2.5 mM KNO3, 2.5 mM Ca(NO3)2, 1.0 mM MgSO4·7H2O, 500 μM KH2PO4, 22.5 µM H3BO3, 5 µM MnCl2·4H2O, 0.4 µM ZnSO4·7H2O, 0.15 µM CuSO4·5H2O, 0.2 µM Na2MoO4·2H2O and 10 µM Fe-EDTA. The pH of the nutrient solution was 6.0. The 500 mL water was poured into the each pot every 5 days. Seedlings were grown for 30 days at 26 °C/22 °C in day/night temperature with a 16-h photoperiod, an irradiance of 480 µmol m−2 s−1, and relative humidity 65–70%. The growth conditions during the experimental period were the same as that in different Pi stess treatment experiment.

Experimental design

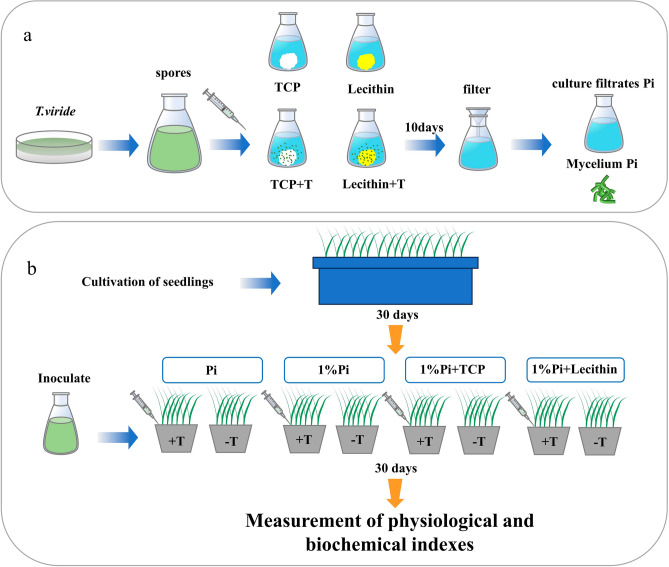

The experiment was conducted using a two factor random block design with two factors, including different Pi forms and T. viride. The experiment designed eight treatments and each treatment had six replicates (Fig. 1b). The 1/2 strength Hoagland nutrient solution was used in this study containing two levels of Pi concentration, 500 μM KH2PO4 (Pi) and 5 μM KH2PO4 (1%Pi). The nutrient solution containing 5 μM KH2PO4 was prepared by substituting KCl for KH2PO4 so that the concentration of K in the nutrient solution was 0.5 mM for all treatments. Tricalcium phosphate (TCP) and egg yolk lecithin (Lecithin) was selected to be used as insoluble Pi. The applied treatments were Pi: irrigating seedlings with 1/2 strength Hoagland nutrient solution containing 500 μM KH2PO4; Pi + T: irrigating seedlings with 1/2 strength Hoagland nutrient solution containing 500 μM KH2PO4 and each seedling was inoculated with 5 mL of T. viride spores fluid; 1%Pi: irrigating seedlings with 1/2 strength Hoagland nutrient solution containing 5 μM KH2PO4; 1%Pi + T: irrigating seedlings with 1/2 strength Hoagland nutrient solution containing 5 μM KH2PO4 and each seedling was inoculated with 5 mL of T. viride spores fluid; 1%Pi + TCP: each pot containing TCP, and irrigating seedlings with 1/2 strength Hoagland nutrient solution containing 5 μM KH2PO4; 1%Pi + TCP + T: Each pot containing TCP, and irrigating seedlings with 1/2 strength Hoagland nutrient solution containing 5 μM KH2PO4, and each seedling was inoculated with 5 mL of T. viride spores fluid; 1%Pi + Lecithin: Each pot containing Lecithin, and irrigating seedlings with 1/2 strength Hoagland nutrient solution containing 5 μM KH2PO4; 1%Pi + Lecithin + T: each pot containing Lecithin, and irrigating seedlings with 1/2 strength Hoagland nutrient solution containing 5 μM KH2PO4, and each seedling was inoculated with 5 mL of T. viride spores fluid. The Pi element applied in the treatment of Pi was 68 mg. The total amount of Pi in insoluble Pi treatments were the same as that in the treatment of Pi. Every 30-day-old seedlings were transplanted into plastic pots (15 cm diameter × 12 cm high) for the different treatments which were poured 100 mL of 1/2 strength Hoagland nutrient solution evry 3 days to culture the plants for 30 days. Then, the plants were harvested for using in the physiological and biochemical assays.

Figure 1.

Experimental design flow chart.

Determination of the ability to release insoluble Pi of T. viride and acidity in culture filtrates

Four treatments were set up with NBRIP (National Botanical Research Institute’s Phosphate) as liquid medium. TCP and Lecithin were selected as insoluble Pi sources. The treatment with only added insoluble Pi was the control group, and with added insoluble Pi and T. viride was the experimental group (Fig. 1a). For this assay, the T. viride spores were inoculated into 100 mL of NBRIP liquid medium in 250 mL conical flasks and pH was adjusted to 7.0. The concentration of inoculated spores was 1 × 108 cfu·mL−1 and the proportion of inoculated spores was 2%. All treatments were incubated at 28 °C in the dark for 10 days. Then, the supernatants was tested for available Pi and mycelium was tested for total Pi using molybdenum blue method36. Culture filtrates was collected after centrifugation of 10-day-old and measured the pH value.

Determination of growth indices

The plant height and leaf area was measured using a precision ruler. The formula for calculating leaf area was: leaf area (cm2) = leaf length × leaf width × 0.7537. Stem diameter was measured using a vernier caliper. Shoots and roots were harvested from each pot and then the roots were washed by water to remove the vermiculite. The fresh shoots and roots were dried at 105 °C for 30 min and after that the temperature was reduced to 70 °C for 10 h. Using a balance with an accuracy of 1/10,000 to measure the dry weight of shoots and roots. The fresh washed roots were scanned using a desktop scanner (EPSON Perfection V 700 Photo; Epson, America, Inc., USA). The resulting image was processed using WinRHIZO image analysis system (Win RHIZO 2012 b; Regent, Canada) to determine the morphological characteristics of the roots.

Measurement of chlorophyll (Chla) fluorescence parameters

The Chla parameters of different treatments were monitored using a MAXI-Imaging PAM M-Series (Heinz Walz GmbH, Effeltrich, Germany). All treatments were kept in a dark adaptation period of 20 min before measurements. The chlorophyll fluorescence parameters were analyzed, such as Maximum efficiency of PSII photochemistry (Fv/Fm), effective PSII quantum yield (ΦPSII or Y(II)), non-photochemical quenching (NPQ), photochemical quenching (qP)35. In order to determine the incidence of the irradiance level on the PSII fluorescence emissions, rapid light curves (RLCs) composed of 16 steps, with durations at each photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) level of 20 s, were performed (0, 1, 20, 55, 110, 185, 280, 335, 395, 460, 530, 610, 700, 800, 925, 1075, 1250 µmol photons m−2 s−1). Draw a line chart of the fluorescence parameters varying with light intensity, such as Y(II), qP, NPQ, electron transport rate (ETR).

Determination of chlorophyll and carotenoid content

The top fresh leaves were cut off from each sample, and weighed to 0.5 g for extracting Chlorophyll (Chl). The leaves were immersed into 95% (v/v) ethanol until complete bleaching. The concentration was determined by measuring extract absorbances at 470 nm, 649 nm, and 665 nm in a spectrophotometer (Hitachi U-3000; Hitachi, Ltd., Chiyoda, Tokyo, Japan). The Chl a, Chl b, and carotenoid (Car) was calculated using the following formulas38:

Determination of total Pi content in tissues

The shoots and roots of the samples were separated and separately dried at 105 °C for 30 min. Then the samples were dried at 65 ◦C for 10 h. The total Pi content of the shoots and roots was measured by the molybdenum blue method36.

Data analysis and statistics

All data from the vitro studies of T. viride and pot experiments from six replicates were analyzed statistically by analysis of variance (ANOVA). We quantified the effects of different Pi treatments on the dry weight and Pi content with or without T. viride inoculation using the two-way ANOVA. Comparison of means were made by Student–Newman–Keuls test(S–N–K) (p < 0.05). All statistical analyses were performed with the SPSS statistical software 26.0, and figures were drawn with OriginPro 2021.

Statement

Our research is in line with local and national guidelines.

Results

The ability to release insoluble Pi of T. viride and acidity in culture filtrates

The T. viride showed Pi solubilization activity in NBRIP medium along with a subsequent decrease in pH (Table 1). The content of soluble Pi in the culture filtrates treated with TCP and T. viride was 394.75% higher than that treated with TCP. While, the content of soluble Pi in the culture filtrates treated with Lecithin and T. viride was 29.95% higher than that treated with Lecithin. The mycelium Pi in the treatment of TCP with T. viride was 14.90 mg·L−1 and which in the treatment of Lecithin was 48.94 mg·L−1. The pH value in the treatment of TCP with T. viride decreased 29.29% than that without T. viride. Similarly, the pH value in the treatment of Lecithin with T. viride decreased 41.26% than that without T. viride.

Table 1.

Pi content of culture filtrates and mycelium and pH value of medium under diferent treatments.

| Treatment | culture filtrates Pi (mg·L-1) |

Mycelium Pi (mg·kg-1) |

Ph |

|---|---|---|---|

| TCP | 0.24 ± 0.16c | 0.00 ± 0.00c | 6.93 ± 0.01a |

| TCP + T | 94.98 ± 3.10a | 14.90 ± 0.12b | 4.90 ± 0.06b |

| Lecithin | 1.87 ± 0.14c | 0.00 ± 0.00c | 4.46 ± 0.03c |

| Lecithin + T | 57.88 ± 0.25b | 48.94 ± 0.11a | 2.62 ± 0.14d |

Values are the means ± S.E. (n = 6) based on analyses by one-way ANOVAs followed by S–N–K test. Different letters indicate significant difference (P < 0.05).

TCP tricalcium phosphate, Lecithin egg yolk lecithin, T T. viride.

Growth indices

Pi content and T. viride was very important for seedling growth. The growth indices of the treatments with T. viride were higher than those without T. viride (Table 2). The plant height in the 1%Pi + Lecithin + T treatment was 2.42% higher than the 1% Pi + TCP + T treatment. However, plant height of the 1%Pi treatment was the lowest among other treatments. Plant height in the 1%Pi + T treatment was on par with the 1%Pi treatment and the Pi + T treatment was pretty much the same as the Pi treatment. The stem diameter of the 1%Pi + Lecithin + T treatment was similar to the 1% Pi + TCP + T treatment, but were 10.14% and 22.76% higher than which treatments without T. viride, respectively. There was no significant difference between the Pi treatment and the Pi + T treatment in leaf area. The leaf area in the 1%Pi + Lecithin + T treatment was 5.67% higer than the 1% Pi + TCP + T treatment. The shoot dry weight of the Pi + T treatment was the highest than the other treatments. The shoot dry weight of the 1%Pi + Lecithin + T treatment was similar to the 1% Pi + TCP + T treatment, but were 54.02% and 34.30% higher than which treatments without T. viride, respectively. The root dry weight in the Pi treatment and the Pi + T treatment were similar and higher than the other treatments. The root dry weight of the 1% Pi + Lecithin + T was 19.23% higher than the 1%Pi + TCP + T treatment. There was a significant positive correlation between parameters of aboveground growth and total Pi content (Fig. 5).

Table 2.

Plant height and stem diameter and leaf area and shoot/root dry weight under different treatments.

| Treatment | Plant height (cm) | Stem diameter (mm) | Leaf area (cm2) | Shoot dry weight (g) | Root dry weight (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pi | 21.97 ± 2.69a | 1.55 ± 0.04a | 3.82 ± 0.07a | 0.422 ± 0.005b | 0.389 ± 0.004a |

| Pi + T | 22.13 ± 1.98a | 1.59 ± 0.03a | 3.91 ± 0.07a | 0.494 ± 0.006a | 0.382 ± 0.002a |

| 1%Pi | 17.83 ± 1.08c | 1.09 ± 0.08d | 1.46 ± 0.36e | 0.195 ± 0.002f | 0.128 ± 0.004g |

| 1%Pi + T | 17.92 ± 2.10c | 1.19 ± 0.09c | 1.99 ± 0.28d | 0.230 ± 0.020e | 0.139 ± 0.002f |

| 1%Pi + TCP | 18.87 ± 0.52bc | 1.23 ± 0.10c | 2.42 ± 0.26c | 0.242 ± 0.003de | 0.171 ± 0.003e |

| 1%Pi + TCP + T | 21.07 ± 0.99ab | 1.51 ± 0.01a | 3.35 ± 0.16b | 0.325 ± 0.003c | 0.208 ± 0.003c |

| 1%Pi + lecithin | 18.48 ± 3.01bc | 1.38 ± 0.09b | 2.56 ± 0.55c | 0.261 ± 0.004d | 0.189 ± 0.002d |

| 1%Pi + lecithin + T | 21.58 ± 0.70a | 1.52 ± 0.04a | 3.54 ± 0.28ab | 0.402 ± 0.005c | 0.248 ± 0.014b |

Values are the means ± S.E. (n = 6) based on analyses by one-way ANOVAs followed by S–N–K test. Different letters indicate significant difference (P < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Correlation analysis of physiological and biochemical indexes.

The root morphological parameters of inoculated T. viride were higher than those of uninoculated treatments (Table 3). The root morphological parameters of the 1%Pi + Lecithin + T treatment were higher than the 1%Pi + Lecithin treatment. The root morphological parameters of the 1%Pi + TCP + T treatment were higher than the 1%Pi + TCP treatment. The root morphological parameters of the Pi + T treatment were higher than the Pi treatment, and as well as the 1%Pi + T treatment which were higher than the 1%Pi treatment. There was a significant positive correlation between parameters of root morphology and total Pi content (Fig. 5).

Table 3.

Root morphological change under diferent Pi treatments.

| Treatments | Root length (cm) | Root volume (cm3) | Root surface area (cm2) | Root diameter (mm) | Number of root tips | Number of crossings | Number of forks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pi | 454.53 ± 19.46a | 2.38 ± 0.34ab | 15.48 ± 0.80ab | 0.52 ± 0.07ab | 1642.50 ± 304.75b | 1629.00 ± 223.92b | 5375.00 ± 376.11a |

| Pi + T | 469.75 ± 13.59a | 2.74 ± 0.55a | 16.03 ± 0.57a | 0.55 ± 0.06a | 1854.33 ± 145.67a | 2119.67 ± 418.25a | 5048.67 ± 551.52ab |

| 1% Pi | 308.83 ± 44.88c | 1.02 ± 0.19d | 11.40 ± 1.25d | 0.36 ± 0.02c | 677.33 ± 122.52e | 804.50 ± 85.74d | 3681.50 ± 622.36d |

| 1% Pi + T | 333.63 ± 32.72c | 1.44 ± 0.32c | 12.73 ± 0.82c | 0.39 ± 0.02c | 836.50 ± 95.70de | 820.83 ± 89.88d | 3781.17 ± 462.17cd |

| 1% Pi + TCP | 321.21 ± 43.18c | 1.92 ± 0.49b | 12.98 ± 0.65c | 0.39 ± 0.03c | 852.50 ± 80.48de | 874.50 ± 70.40d | 4369.17 ± 470.95bc |

| 1% Pi + TCP + T | 385.45 ± 12.41b | 2.13 ± 0.20b | 14.54 ± 0.51b | 0.48 ± 0.03b | 1288.83 ± 164.05c | 1346.33 ± 79.14c | 4665.67 ± 435.93ab |

| 1% Pi + lecithin | 336.22 ± 14.90c | 2.09 ± 0.13b | 13.23 ± 1.13c | 0.41 ± 0.03c | 974.00 ± 168.05d | 959.17 ± 75.49d | 4433.83 ± 480.50bc |

| 1%Pi + lecithin + T | 470.25 ± 13.39a | 2.28 ± 0.30ab | 15.81 ± 0.63a | 0.48 ± 0.03b | 1613.17 ± 179.99b | 1452.67 ± 50.03bc | 4983.17 ± 446.05ab |

Values are the means ± S.E. (n = 6) based on analyses by one-way ANOVAs followed by S–N-K test. Different letters indicate significant difference (P < 0.05).

Parameters of Chlorophyll a fluorescence

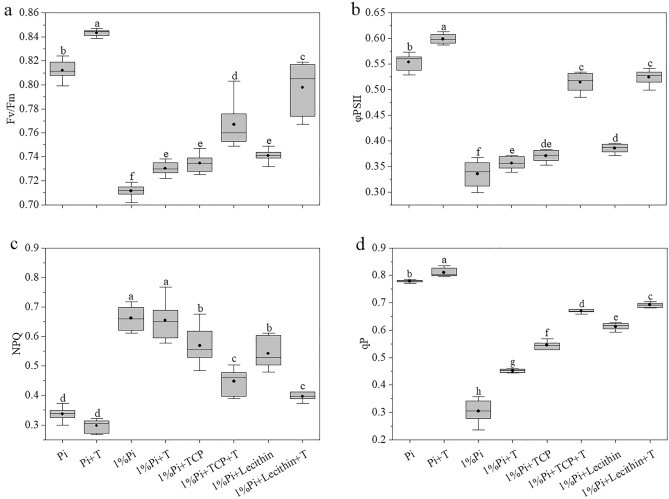

Compared to the non-inoculated treatment, the T. viride inoculation increased Fv/Fm, ϕPSII and qP, but decreased NPQ (Fig. 2). The results showed that the highest Fv/Fm was the Pi + T treatment, and the lowest was the 1%Pi treatment (Fig. 2a). In insoluble-Pi treatments which inoculated T. viride, Fv/Fm of the 1%Pi + Lecithin + T treatment was higher than the 1%Pi + TCP + T treatment. In low Pi treatments, Fv/Fm of the 1%Pi + T treatment was higher than the 1%Pi treatment. The results showed that the highest ϕPSII was the Pi + T treatment, and the lowest was the 1%Pi treatment (Fig. 2b). In insoluble-Pi treatments which inoculated T. viride, there was no significant difference of ϕPSII between the 1%Pi + Lecithin + T treatment and the 1%Pi + TCP + T treatment. In low Pi treatments, ϕPSII of the 1%Pi + T treatment was higher than the 1%Pi treatment. The results showed that the highest qP was the Pi + T treatment, and the lowest was the 1%Pi treatment (Fig. 2c). In insoluble Pi treatments which inoculated T. viride, qP of the 1%Pi + Lecithin + T treatment was higher than the 1%Pi + TCP + T treatment. In low Pi treatments, qP of the 1%Pi + T treatment was higher than the 1%Pi treatment. From the resaults, we found that the highest NPQ were the 1%Pi treatment and the 1%Pi + T treatment, the lowest were the Pi treatment and the Pi + T treatment (Fig. 2d). In insoluble-Pi treatments which inoculated T. viride, NPQ of the 1%Pi + Lecithin + T treatment was lower than the 1%Pi + Lecithin treatment and the 1%Pi + TCP + T treatment was lower than the 1%Pi + TCP treatment. However, there was no significant difference of NPQ between the 1%Pi + Lecithin + T treatment and the 1%Pi + TCP + T treatment and the same as the 1%Pi + Lecithin treatment and the 1%Pi + TCP treatment. In low Pi treatments, there was no significant difference of NPQ between the 1%Pi treatment and the 1%Pi + T treatment. There was a significant positive correlation between parameters of chlorophyll a fluorescence and shoot total Pi content (Fig. 5).

Figure 2.

Comparisons of chlorophyll fluorescence parameters: (a) maximum quantum yield of PSII (Fv/Fm), (b) effective quantum yield of PSII (ϕPSII), (c) nonphotochemical quenching (NPQ), (d) coefficient of photochemical quenching(qP). Values are the means ± S.E. (n = 6) based on analyses by one-way ANOVAs followed by S–N–K test. Different letters indicate significant difference (P < 0.05).

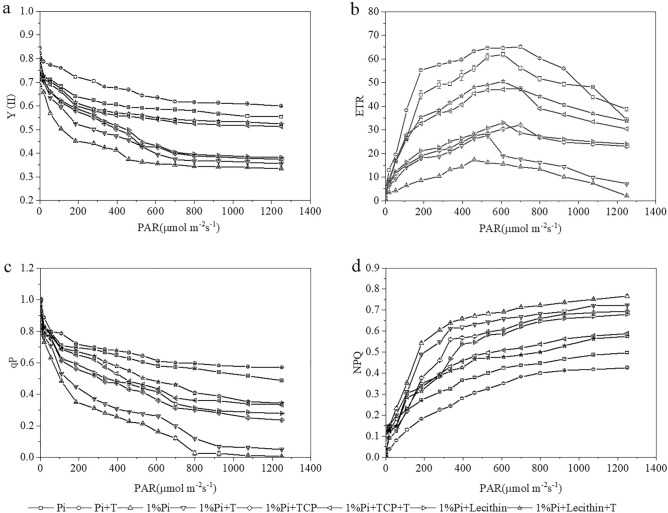

We also analyzed the light-response curves of the Y (II), ETR, qP, and NPQ of PSII under the condition of the T. viride inoculation or non-inoculation in deffrent Pi supply (Fig. 3). Y(II) reduction of the inoculated T. viride treatment was more slowly than uninoculated T. viride treatment under light intensity (PAR < 500 µmol·m−2·s−1) (Fig. 3a). When light intensities > 500 µmol·m−2·s−1, the production of light quantum production was inhibited. ETR increasing of the inoculated T. viride treatment was more faster than uninoculated T. viride treatment under a certain range of light intensity (PAR < 500 µmol·m−2·s−1), subsequently reached plateaued (Fig. 3b). qP of the T. viride inoculation treatment decreased slowly compared with the T. viride uninoculation treatment under light intensity (PAR < 500 µmol·m−2·s−1) (Fig. 3c). NPQ of the T. viride uninoculation treatment rose sharply relative to the T. viride inoculation treatment under light intensity (PAR < 500 µmol·m−2·s−1) (Fig. 3d). Excess excitation energy was dissipated as heat energy under the condition of low Pi and insoluble Pi. Therefore, inoculation with T. viride alleviated PSII impairment to some extent.

Figure 3.

Chlorophyll fluorescence parameters as a function of PAR: (a) plots of Y (II) vs. PAR, (b) photosynthetic electron transfer rates (ETR) vs. PAR, (c) qP vs. PAR, (d) NPQ vs. PAR. Values are the means ± S.E. (n = 6) based on analyses by one-way ANOVAs followed by S–N–K test. Different letters indicate significant difference (P < 0.05).

The content of chlorophyll, carotenoid and Chl a/Chl b ratio

The content of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b and carotenoid content in the treatment with T. viride was significantly higher than that for the treatment without T. viride. There were no significant differences in Chl a/Chl b ratios among all treatments (Table 4). The chlorophyll a content, chlorophyll b content, carotenoid content and Chl a/Chl b ratio in Pi + T was the highest than other treatments. In the Pi + T treatment, the chlorophyll a content was 14.69% higher than the Pi, but there was no significant difference in chlorophyll b content, carotenoid content, Chl a/Chl b ratio between the Pi + T treatment and the Pi treatment. The chlorophyll a content of the 1%Pi + Lecithin + T treatment was 41.35% higher than the 1%Pi + Lecithin treatment and the chlorophyll b content of the 1%Pi + Lecithin + T treatment was 11.94% higher than the 1%Pi + Lecithin treatment. However, there was no significant difference in carotenoid content, Chl a/Chl b ratio between the 1%Pi + Lecithin + T treatment and the 1%Pi + Lecithin treatment. The chlorophyll a content of the 1%Pi + TCP + T treatment was 27.62% higher than the 1%Pi + TCP treatment and the chlorophyll b content of the 1%Pi + TCP + T treatment was 13.85% higher than the 1%Pi + TCP treatment. However, there was no significant difference in carotenoid content, Chl a/Chl b ratio between the 1%Pi + Lecithin + T treatment and the 1%Pi + Lecithin treatment. There was no significant difference in Photosynthetic pigment parameters between the 1%Pi + T treatment and the 1%Pi treatment. photosynthetic pigment was positively correlated with aboveground growth Indices, chlorophyll a fluorescence except NPQ, and the correlation between Chl a/Chl b ratio and other parameters was not obvious (Fig. 5).

Table 4.

Chlorophyll content and carotenoid content and the Chl a/Chl b ratios.

| Treatment | Chlorophyll a content (mg·g−1 FW) | Chlorophyll b content (mg·g−1 FW) | Carotenoid content (mg·g−1 FW) | Chl a/Chl b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pi | 1.77 ± 0.04b | 1.03 ± 0.03a | 0.33 ± 0.07a | 1.73 ± 0.06a |

| Pi + T | 2.03 ± 0.02a | 1.07 ± 0.06a | 0.36 ± 0.05a | 1.93 ± 0.10a |

| 1%Pi | 0.91 ± 0.11d | 0.51 ± 0.02d | 0.11 ± 0.01b | 1.83 ± 0.26a |

| 1%Pi + T | 0.96 ± 0.06d | 0.52 ± 0.01d | 0.12 ± 0.01b | 1.88 ± 0.15a |

| 1%Pi + TCP | 1.05 ± 0.11d | 0.65 ± 0.02cd | 0.16 ± 0.01b | 1.63 ± 0.19a |

| 1%Pi + TCP + T | 1.34 ± 0.06c | 0.74 ± 0.04bc | 0.21 ± 0.01b | 1.83 ± 0.05a |

| 1%Pi + lecithin | 1.04 ± 0.04d | 0.67 ± 0.04cd | 0.17 ± 0.01b | 1.61 ± 0.18a |

| 1%Pi + lecithin + T | 1.47 ± 0.06c | 0.75 ± 0.03b | 0.22 ± 0.02b | 2.10 ± 0.57a |

Values are the means ± S.E. (n = 6) based on analyses by one-way ANOVAs followed by S–N–K test. Different letters indicate significant difference (P < 0.05).

The content of Pi in shoot and root

Compared to the non-inoculated treatment, the T. viride inoculation increased the content of Pi in shoot and root. But there was no difference between the Pi treatment and the the Pi + T treatment, and which was no difference between the 1%Pi treatment and the the 1%Pi + T treatment (Fig. 4). On the other hand, plants grown with T. viride under insoluble Pi conditions were more easier to shift Pi from below-ground to above-ground tissues than the teatments without T. viride. In the 1%Pi + TCP + T treatment, the shoot Pi content was 65.46% higher than the root Pi content. In the 1%Pi + Lecithin + T treatment, the shoot Pi content was 114.43% higher than the root Pi content. The shoot Pi content was positively correlated with parameters of aboveground growth, root morphology, photosynthetic pigment, parameters of chlorophyll a fluorescence except NPQ (Fig. 5). The root Pi content was positively correlated with root dry weight, root morphology, but negatively correlated with NPQ (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

Shoot and Root Pi content. Values are the means ± S.E. (n = 6) based on analyses by one-way ANOVAs followed by S–N–K test. Different letters indicate significant difference (P < 0.05).

Discussion

In recent years, there has been an growing interest in PSM. The use of PSM is an effective way to dissolve insoluble Pi in the soil and thus supply it to plants for uptake. At the same time, it had a beneficial effect on the growth and development of plants. In agricultural production, the application of PSM to the soil could reduce the use of chemical fertilizer and gradually replace the dominant position of chemical fertilizer39,40. Therefore, the present study evaluated the role of T. viride in Pi solubilization and in promoting the growth of M. officinalis.

The results showed that the T. viride could dissolve TCP and lecithin and reduce the pH value in the culture medium (Table 1). This might be because the PSM can dissolve insoluble Pi by releasing protons and producing organic acids to reduce the surrounding pH41,42. However, dissolving Pi is not a simple phenomenon, and each kind of PSM can use a variety of mechanisms to dissolve insoluble Pi. Therefore, it is necessary to further study the Pi solubilization mechanism of T. viride.

Inoculation of PSM has been reported to not only dissolve insoluble Pi in soil, but also promote plant growth 43. Our results showed that the growth indices of M. officinalis inoculated with T. viride were higher than the treatments without T. viride when insoluble Pi was used as Pi source (Table 2). The choices of Pi source and the addition of T. viride had a very strong effect on the dry weight of M. officinalis. This finding is consistent with previous work by Abdenaceur et al., who found that Trichoderma spp. secrete plant growth-promoting hormones, such as IAA 44. Root is an important organ for plants to absorb nutrients, which can sense the changes of nutrient concentration in soil, thus influencing changes in the root morphology of plants45. A study revealed that mung bean inoculated with PSB (Pseudomonas spp.) could increase root length and dry weight46. Our study also confirmed that the root morphological parameters of the treatment inoculated with T. viride were better than those without inoculation (Table 3). However, due to the presence of T. viride, M. officinalis changes its resource allocation strategy and is able to allocate more resources to above-ground growth and facilitate Pi uptake by the plant, allowing plants to have lower investment into below-ground biomass, and higher benefit for above-ground biomass (Table 3 and Fig. 4). Chlorophyll fluorescence parameters can characterize photosynthetic ability and energy conversion efficiency47. A study reported that under salt stress, inoculation of AMF or PSF increased the nutrient absorption of beach plums, and improved the parameters of chlorophyll fluorescence, such as Fv/Fm, qP and ϕPSII values, but NPQ values remained unchanged or decreased compared with the control48. Our results showed that the values of Fv/Fm, qP and ϕPSII of M. officinalis inoculated with T. viride under insoluble Pi stress were higher than those of the treatments without T. viride, while the values of NPQ were lower than the treatments without T. viride (Fig. 2). Moreover, the Y (II) and qP light-response curves of M. officinalis inoculated with T. viride decreased slowly compared with that without inoculation (Fig. 3). The ETR light-response curves of M. officinalis inoculated with T. viride increased faster than that without inoculation. The NPQ light-response curves of M. officinalis inoculated with T. viride rise more slowly than that without inoculation. Our study suggested that M. officinalis inoculated with T. viride could increase the efficiency of excitation energy capture by leaf chloroplasts and increase the photochemical capacity of PSII. The content of plant photosynthetic pigment shows the degree of plant stress and can be used as an indicator to evaluate the physiological status of plants49. Liu et al.50 found that the chlorophyll content of alfalfa inoculated with PSB was higher than that without inoculation. Similar to this study, the treatment inoculated with T. viride had higher Chlorophyll content and Carotenoid content and the Chl a/Chl b ratios than the uninoculated treatment (Table 4).

Qi et al.51 found that AMF were able to promote Solidago canadensis absorb more Pi in insoluble Pi conditions. A study reported that when phosphate rock was used as Pi source, Trichoderma spp. could dissolve phosphate rock and enhance the Pi content of chickpea shoots and roots, such as T. viride, T. virens, T. virens34. Our results also proved this point, the content of Pi in shoots and roots of M. officinalis inoculated with T. viride was higher than that wuthout inoculation (Fig. 4). T. viride and Pi source are the main factors, which affecting the Pi uptake and biomass of M. officinalis. Moreover, when insoluble Pi was used as Pi source, the Pi content of M. officinalis inoculated with T. viride was more distributed to the stem and supplied to the aboveground part of the plant. However, the M. officinalis without T. viride had more Pi content in the root under the condition of insoluble Pi. This may be due to the fact that the root system is the main organ for plants to absorb nutrients and plants do not need to expend more resources to invest in root growth under the condition of sufficient Pi.

Conclusions

This study provides new evidence that T. viride can dissolve insoluble inorganic phosphorus and insoluble organic Pi. In addition to providing soluble phosphorus, T. viride also promotes plant growth of M. officinalis by improving root morphology and regulating plant photosynthesis. This research lays a foundation for recommending T. viride as a biological fertilizer and reduces environmental pollution caused by chemical fertilizer.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank Xiaowei Wei, Rong Xiong, Jiawei Dong for their help during laboratory analyses. We would like to acknowledge the editor and reviewers for their helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for Science and Technology Development Plan Project of Jilin Province (20210202017NC).

Author contributions

M.S., H.X., X.Z. and C.M. designed the study. M.S.and X.W. conducted the study. M.S. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Data availability

The relevant experimental data are made available in Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.22297105.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Xiaofu Zhou, Email: zhouxiaofu@jlnu.edu.cn.

Chunsheng Mu, Email: mucs821@nenu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Song L, Liu D. Ethylene and plant responses to phosphate deficiency. Front. Plant Sci. 2015;6:796. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Puga MI, et al. Novel signals in the regulation of Pi starvation responses in plants: Facts and promises. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2017;39:40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2017.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Timofeeva A, Galyamova M, Sedykh S. Prospects for using phosphate-solubilizing microorganisms as natural fertilizers in agriculture. Plants. 2022;11:2119. doi: 10.3390/plants11162119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alewell C, et al. Global phosphorus shortage will be aggravated by soil erosion. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:4546. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18326-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun R, et al. Changes in phosphorus mobilization and community assembly of bacterial and fungal communities in rice rhizosphere under phosphate deficiency. Front. Microbiol. 2022;13:953340. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.953340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Augustine DJ, McNaughton SJ, Frank DA. Feedbacks between soil nutrients and large herbivores in a managed savanna ecosystem. Ecol. Appl. 2003;13:1325–1337. doi: 10.1890/02-5283. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abel S, Ticconi CA, Delatorre CA. Phosphate sensing in higher plants. Physiol. Plant. 2002;115:1–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2002.1150101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sattari SZ, Bouwman AF, Giller KE, van Ittersum MK. Residual soil phosphorus as the missing piece in the global phosphorus crisis puzzle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:6348–6353. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113675109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu J, Li M, Whelan M. Phosphorus activators contribute to legacy phosphorus availability in agricultural soils: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2018;612:522–537. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.08.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alori ET, Glick BR, Babalola OO. Microbial phosphorus solubilization and its potential for use in sustainable agriculture. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:971. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma SB, Sayyed RZ, Trivedi MH, Gobi TA. Phosphate solubilizing microbes: Sustainable approach for managing phosphorus deficiency in agricultural soils. Springerplus. 2013;2:587. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-2-587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bargaz A, et al. Benefits of phosphate solubilizing bacteria on belowground crop performance for improved crop acquisition of phosphorus. Microbiol. Res. 2021;252:126842. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2021.126842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bi QF, et al. The microbial cycling of phosphorus on long-term fertilized soil: Insights from phosphate oxygen isotope ratios. Chem. Geol. 2018;483:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2018.02.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanif K, et al. Isolation and characterization of a β-propeller gene containing phosphobacterium Bacillus subtilis strain KPS-11 for growth promotion of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Front. Microbiol. 2015;6:583. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodríguez H, Fraga R, Gonzalez T, Bashan Y. Genetics of phosphate solubilization and its potential applications for improving plant growth-promoting bacteria. Plant Soil. 2006;287:15–21. doi: 10.1007/s11104-006-9056-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bianco C, Defez R. Improvement of phosphate solubilization and Medicago plant yield by an indole-3-acetic acid-overproducing strain of Sinorhizobium meliloti. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010;76:4626–4632. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02756-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shahid M, Hameed S, Imran A, Ali S, van Elsas JD. Root colonization and growth promotion of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) by phosphate solubilizing Enterobacter sp. Fs-11. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012;28:2749–2758. doi: 10.1007/s11274-012-1086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gomez-Ramirez LF, Uribe-Velez D. Phosphorus solubilizing and mineralizing Bacillus spp. contribute to rice growth promotion using soil amended with rice straw. Curr. Microbiol. 2021;78:932–943. doi: 10.1007/s00284-021-02354-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang L, Feng G, Declerck S. Signal beyond nutrient, fructose, exuded by an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus triggers phytate mineralization by a phosphate solubilizing bacterium. ISME J. 2018;12:2339–2351. doi: 10.1038/s41396-018-0171-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Emami S, et al. Effect of rhizospheric and endophytic bacteria with multiple plant growth promoting traits on wheat growth. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019;26:19804–19813. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-05284-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yahya M, et al. Differential root exudation and architecture for improved growth of wheat mediated by phosphate solubilizing bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2021;12:744094. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.744094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Srivastava S, Srivastava S. Prescience of endogenous regulation in Arabidopsis thaliana by Pseudomonas putida MTCC 5279 under phosphate starved salinity stress condition. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:5855. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-62725-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hakim S, et al. Rhizosphere engineering with plant growth-promoting microorganisms for agriculture and ecological sustainability. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021;5:617157. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2021.617157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumawat KC, et al. Dual microbial inoculation, a game changer?—Bacterial biostimulants with multifunctional growth promoting traits to mitigate salinity stress in spring mungbean. Front. Microbiol. 2021;11:600576. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.600576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berruti A, Lumini E, Balestrini R, Bianciotto V. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi as natural biofertilizers: Let’s benefit from past successes. Front. Microbiol. 2016;6:1559. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clausing S, Polle A. Mycorrhizal phosphorus efficiencies and microbial competition drive root P uptake. Front. For. Glob. Change. 2020;3:54. doi: 10.3389/ffgc.2020.00054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tian J, et al. Phosphorus fertilization affects soybean rhizosphere phosphorus dynamics and the bacterial community in karst soils. Plant Soil. 2022;475:137–152. doi: 10.1007/s11104-020-04662-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waghunde RR, Shelake RM, Sabalpara AN. Trichoderma: A significant fungus for agriculture and environment. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2016;11:1952–1965. doi: 10.5897/AJAR2015.10584. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harman GE, Howell CR, Viterbo A, Chet I, Lorito M. Trichoderma species—Opportunistic, avirulent plant symbionts. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004;2:43–56. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herrera-Parra E, Cristóbal-Alejo J, Ramos-Zapata JA. Trichoderma strains as growth promoters in Capsicum annuum and as biocontrol agents in Meloidogyne incognita. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 2017;77:318–324. doi: 10.4067/S0718-58392017000400318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He C, Wang W, Hou J. Plant performance of enhancing licorice with dual inoculating dark septate endophytes and Trichoderma viride mediated via effects on root development. BMC Plant Biol. 2020;20:325. doi: 10.1186/s12870-020-02535-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gravel V, Antoun H, Tweddell RJ. Growth stimulation and fruit yield improvement of greenhouse tomato plants by inoculation with Pseudomonas putida or Trichoderma atroviride: Possible role of indole acetic acid (IAA) Soil Biol. Biochem. 2007;39:1968–1977. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2007.02.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang F, et al. Biocontrol potential of Trichoderma harzianum isolate T-aloe against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in soybean. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016;100:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2015.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rudresh DL, Shivaprakash MK, Prasad RD. Tricalcium phosphate solubilizing abilities of Trichoderma spp. in relation to P uptake and growth and yield parameters of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) Can. J. Microbiol. 2005;51:217–222. doi: 10.1139/w04-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suárez JC, et al. Chlorophyll fluorescence imaging as a tool for evaluating disease resistance of common bean lines in the western Amazon region of Colombia. Plants. 2022;11:1371. doi: 10.3390/plants11101371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murphy J, Riley JP. A modified single solution method for the determination of phosphate in natural waters. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1962;27:31–36. doi: 10.1016/S0003-2670(00)88444-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fang H, Niu M, Wang X, Zhang Q. Effects of reduced chemical application by mechanical–chemical synergistic weeding on maize growth and yield in East China. Front. Plant Sci. 2022;13:1024249. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.1024249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wellburn, A. R. & Lichtenthaler, H. Formulae and program to determine total carotenoids and chlorophylls A and B of leaf extracts in different solvents. in Advances in Photosynthesis Research (ed. Sybesma, C.). 9–12 (Springer, 1984).

- 39.Cardoso AF, et al. Bacillus cereus improves performance of Brazilian green dwarf coconut palms seedlings with reduced chemical fertilization. Front. Plant Sci. 2021;12:649487. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.649487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Batool S, Iqbal A. Phosphate solubilizing rhizobacteria as alternative of chemical fertilizer for growth and yield of Triticum aestivum (Var. Galaxy 2013) Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2019;26:1400–1410. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2018.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Etesami H, Jeong BR, Glick BR. Contribution of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, phosphate-solubilizing bacteria, and silicon to P uptake by plant. Front. Plant Sci. 2021;12:699618. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.699618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chouyia FE, et al. P-solubilizing Streptomyces roseocinereus MS1B15 with multiple plant growth-promoting traits enhance barley development and regulate rhizosphere microbial population. Front. Plant Sci. 2020;11:1137. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.01137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xiao C, et al. Isolation of phosphate-solubilizing fungi from phosphate mines and their effect on wheat seedling growth. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2009;159:330–342. doi: 10.1007/s12010-009-8590-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abdenaceur R, et al. Effective biofertilizer Trichoderma spp. isolates with enzymatic activity and metabolites enhancing plant growth. Int. Microbiol. 2022;25:817–829. doi: 10.1007/s10123-022-00263-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grover M, et al. PGPR mediated alterations in root traits: Way toward sustainable crop production. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021;4:618230. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2020.618230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bilal S, et al. Comparative effect of inoculation of phosphorus-solubilizing bacteria and phosphorus as sustainable fertilizer on yield and quality of mung bean (Vigna radiata L.) Plants. 2021;10:2079. doi: 10.3390/plants10102079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sheng M, et al. Influence of arbuscular mycorrhizae on photosynthesis and water status of maize plants under salt stress. Mycorrhiza. 2008;18:287–296. doi: 10.1007/s00572-008-0180-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zai XM, Fan JJ, Hao ZP, Liu XM, Zhang WX. Effect of co-inoculation with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and phosphate solubilizing fungi on nutrient uptake and photosynthesis of beach palm under salt stress environment. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:5761. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-84284-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zarco-Tejada PJ, Miller JR, Mohammed GH, Noland TL, Sampson PH. Vegetation stress detection through chlorophyll a + b estimation and fluorescence effects on hyperspectral imagery. J. Environ. Qual. 2002;31:1433–1441. doi: 10.2134/jeq2002.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu J, et al. Response of alfalfa growth to arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and phosphate-solubilizing bacteria under different phosphorus application levels. AMB Exp. 2020;10:200. doi: 10.1186/s13568-020-01137-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qi S, et al. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi contribute to phosphorous uptake and allocation strategies of Solidago canadensis in a phosphorous-deficient environment. Front. Plant Sci. 2022;13:831654. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.831654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The relevant experimental data are made available in Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.22297105.