Abstract

One large focus of personality psychology is to understand the biopsychosocial factors responsible for adult personality development and well-being change. However, little is known about how macro-level contextual factors, such as rurality-urbanicity, are related to personality development and well-being change. The present study uses data from two large longitudinal studies of U.S. Americans (MIDUS, HRS) to examine whether there are rural-urban differences in levels and changes in the Big Five personality traits and well-being (i.e., psychological well-being, life satisfaction) in adulthood. Multilevel models showed that Americans who lived in more rural areas tended to have lower levels of openness, conscientiousness, and psychological well-being, and higher levels of neuroticism. With the exception of psychological well-being (which replicated across MIDUS and HRS), rural-urban differences in personality traits were only evident in the HRS sample. The effect of neuroticism was fully robust to the inclusion of socio-demographic and social network covariates, but other effects were partially robust (i.e., conscientiousness, openness) or were not robust at all (i.e., psychological well-being). In both samples, there were no rural-urban differences in Big Five or well-being change. We discuss the implications of these findings for personality and rural health research.

Keywords: Rurality, Big Five, Psychological Well-being, Life Satisfaction, Longitudinal, HRS, MIDUS

Introduction

While there are normative trends in personality and well-being development, there are also substantial individual differences in levels and changes in personality traits and well-being across the adult lifespan (Atherton et al., 2020; Graham et al., 2020; Hudson et al., 2019). A significant amount of work in personality psychology over the last several decades has aimed to not only descriptively characterize personality and well-being development, but also to identify the biological, psychological, and social factors that account for why some people increase, decrease, or do not change much at all in their personality traits and well-being over the course of their adult lives. More recently, there has been an increasing interest in understanding how “macro” contexts, like the neighborhood, culture, or region, impact personality and well-being development (Atherton et al., 2021; Cheung, 2018; Ebert et al., 2021; Jokela et al., 2015; Oishi et al., 2009; Rentfrow & Jokela, 2016). However, compared to the expansive literature on spatial and regional differences in psychological characteristics (e.g., Rentfrow et al., 2008; Rentfrow & Jokela, 2016), less is known about the extent to which specific characteristics of where people live can explain individual differences in personality trait and well-being levels and change (but see Burger et al., 2020; Elleman et al., 2020). To fill these gaps, the present study uses two large longitudinal samples of U.S. Americans to understand how rurality-urbanicity is related to personality and well-being development across adulthood.

Although definitions of what is considered “rural” versus “urban” vary (e.g., Cromartie & Bucholtz, 2008; Ratcliffe et al., 2018), we consider rurality-urbanicity to have two primary features: 1) population count; and 2) whether the location is (or is not) adjacent to a metropolitan area (USDA Economic Research Service, 2019). As of 2021, approximately 46 million Americans (20% of the U.S. population) live in rural areas and experience significant health disparities compared to Americans who live in urban, metropolitan areas (Bureau, 2010; Dobis et al., 2021; Kusmin, 2016; Moy et al., 2017). Rural health disparities are thought to be due to a confluence of factors including lower income, lower educational attainment, and lower health literacy; increased likelihood of being underinsured or uninsured; reduced access to healthcare services and healthy food; increased exposure to air and water pollutants associated with agriculture and mining; and the lack of publicly funded support for structural infrastructure (e.g., broadband internet) in rural areas (Burger et al., 2020; Douthit et al., 2015; Lewis-Thames et al., 2022; Matthews et al., 2017; Strosnider et al., 2017). Because personality traits and well-being are consequential for the same health behaviors and outcomes that also systematically vary by rural-urban contexts (Friedman et al., 2010; Graham et al., 2017; Hakulinen et al., 2015; Jokela et al., 2018; Jokela et al., 2014; Kushlev et al., 2020; Lewis-Thames et al., 2020; Matthews et al., 2017; Okely & Gale, 2016; Soto, 2019; Sutin et al., 2016; Turiano et al., 2012), there is reason to suspect that the same ecological, social, and structural mechanisms that lead to rural health disparities may also be responsible for rural-urban differences in personality and well-being.

At a broad-level, there is compelling evidence that state- and region-level variations in psychological characteristics are robust and can be studied reliably both within and across countries (Diener et al., 2010; Diener et al., 2015; Ebert et al., 2021; McCrae & Terracciano, 2005, 2008; Rentfrow, 2010; Rentfrow et al., 2013; Rentfrow et al., 2009). Regional clustering by personality and well-being is fairly well-documented in the U.S. (Ebert et al., 2021; Elleman et al., 2018; 2020; Obschonka et al., 2019; Pesta et al., 2012; Plaut et al., 2002; Rentfrow et al., 2013), Great Britain (Jokela et al., 2015; Rentfrow et al., 2015), Russia (Allik et al., 2009), Germany (Obschonka et al., 2019), Switzerland (Götz et al., 2018), New Zealand (Greaves et al., 2015), Italian archipelagos (Campero Ciani et al., 2007), and China (Wei et al., 2017). Broader geographical regions, states, and zip codes can be characterized by numerous characteristics; and thus, at present it is not clear what aspects of these environments are related to personality and well-being. Recent research has begun to push this line of inquiry further by examining how specific characteristics of a region, such as walkability and topography, are related to differences in personality traits (Götz et al., 2020; Götz et al., 2020). Likewise, we aim to contribute to this literature by specifically examining the role of rurality-urbanicity for levels and changes in personality and well-being.

A fairly extensive body of work has examined rural-urban differences in various aspects of subjective well-being (i.e., life satisfaction, happiness, positive and negative affect), showing that people who live in rural contexts tend to have lower levels of subjective well-being and higher levels of loneliness than people who reside in urban contexts (Buecker et al., 2021; Burger et al., 2020; Hoogerbrugge & Burger, 2022; Wang & Wang, 2016). However, few studies have investigated rural-urban differences in personality or psychological well-being (e.g., autonomy, purpose in life, self-acceptance) levels. The most closely related studies have shown replicable associations between population density and regional-level (or individual-level) personality traits like Openness to Experience – more densely populated areas tend to be higher in Openness to Experience, for example (Ebert et al., 2021; Elleman et al., 2022; Rentfrow et al., 2015). Likewise, another study investigated how an accessibility-remoteness index (i.e., distance from, and accessibility to, social services) was related to personality traits in Australia, finding that people who lived in highly accessible areas tended to be higher in Openness and Extraversion (Murray et al., 2005). Further, to our knowledge, there is only one study that has examined Arya & Sangwan (2018) examined how psychological well-being dimensions differed among rural and urban adolescents in the Haryana state of India and found that urban adolescents tended to have higher levels of psychological well-being (across domains) than rural adolescents. Our current understanding of rural-urban differences in personality trait and psychological well-being levels is limited in scope.

We have even less of an understanding of rural-urban differences in personality traits and well-being change. There are generally two theoretical frameworks that may guide our understanding of personality and well-being change across adulthood. On the one hand, patterns of personality and well-being change across adulthood may be due to universal processes that are common across people such as biological or social role changes (e.g., Atherton et al., 2020; Bleidorn et al., 2013; Triandis & Suh, 2002). In this case, we might not expect rurality-urbanicity to impact personality and well-being change because all adults are likely experiencing similar biological or social role changes regardless of whether they are living in a rural or urban place. For example, physiological changes due to aging, or social role changes due to grandparenthood or widowhood, likely occur regardless of whether someone lives in a rural or urban location. On the other hand, to the extent that personality and well-being change are due to culturally-specific processes, we might expect rurality-urbanicity to play a role in how personality traits and well-being change across adulthood. For example, Triandis and Suh (2002) suggest that ecology shapes culture, and culture shapes personality. Among the many dimensions of culture, they note urbanicity as one such aspect of culture (or “complexity”), as population size is positively associated with social capital, technology, and other resources. Thus, rurality-urbanicity, as a broader cultural environment, may impact changes in personality and well-being. We recognize that universal versus culturally-specific explanations of adult development are not mutually exclusive and are likely not unidirectional in their relation to personality and well-being. However, these two overarching processes provide important guiding frameworks for understanding why rurality-urbanicity may or may not be related to personality and well-being development across adulthood, questions that have yet to be investigated empirically.

The present study set out to address two main research questions: 1) Are there rural-urban differences in levels of the Big Five personality traits, psychological well-being, or life satisfaction in middle and older adulthood?; 2) Are there rural-urban differences in Big Five, psychological well-being, or life satisfaction change across middle and older adulthood? The current study is well-suited to answer these research questions and fill prior gaps in the literature because it leverages data from two large longitudinal studies of American adults, whose primary residences were linked to geographic information about rurality-urbanicity and who have comprehensive assessments of multiple dimensions of personality (i.e., the Big Five) and well-being (i.e., psychological well-being and life satisfaction), spanning 12 to 20 years of adulthood. Based on prior work (e.g., Burger et al., 2020; Greaves et al., 2015; Rentfrow et al., 2013), we pre-registered predictions that: (a) openness will be higher in urban counties relative to rural counties, and (b) life satisfaction will be higher in rural counties relative to urban counties. We pre-registered no predictions for conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, neuroticism, psychological well-being, or for any of the longitudinal change analyses.

Method

Participants and Procedures

The present study used longitudinal data from two national probability samples: Midlife in the United States (Brim et al., 2004) and the Health and Retirement Study (Sonnega et al., 2014). Details regarding MIDUS and HRS participant recruitment, data collection, descriptive statistics of the samples, data dictionaries, and datasets are publicly available at https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/web/ICPSR/series/203 and https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/about, respectively. Pre-registrations, deviations from the pre-registrations, R code, and output can be found on the Open Science Framework (OSF) project page: https://osf.io/fmuvq/.1

The MIDUS sample consists of data from 7,108 Americans (52% female) who were recruited via random digit dialing and first assessed in 1995–96, with two follow-up assessments conducted in 2004–2006 (N = 4,963) and 2013–2014 (N = 3,294). At Time 1, participants ranged in age from 20 to 75 years (Median age = 45 years). The median education level was 6 years and the median household income was $55,000. The sample was 90% White, 5% Black/African-American, 1% American Indian or Alaskan Native, 1% Asian or Pacific Islander, 1% multiracial, and 2% identified as “other”. At Time 1, 3% of participants identified as Hispanic or Latino; 75% were employed; 14% were retired; and 71% were married or had a partner. Although the MIDUS study oversampled in some regions to improve representativeness, the sample underrepresents individuals with less than a high school degree, African Americans, and Latino Americans, and intentionally overrepresents older males to facilitate gender comparisons with age (Brim et al., 2004).

The HRS sample consists of data from approximately 20,000 Americans who were recruited via multi-stage area probability sampling and first assessed in 1992, with annual assessments conducted to the present (2022). The present study uses data starting in 2006 and 2008, which is when the personality variables were first assessed. All personality variables were assessed in two cohorts, who participated alternately every two years, resulting in two parallel 8-year longitudinal cohorts (i.e., Cohort 1 in 2006, 2010, 2014, and 2018; and Cohort 2 in 2008, 2012, 2016, and 2020). We combined data from these two cohorts to form a single sample with four assessment points at four-year intervals (N = 23,976; 58% female). In 2006 / 2008 (which we will refer to as “baseline”), participants ranged in age from 25 to 104 years (Median age = 68 years). The median education level was 12 years and the median household income was $39,400. 74% of participants were White, 18% were Black/African-American, 8% were another race. At baseline, 13% of participants identified as Hispanic or Latino; 33% of participants were employed; 47% were retired; and 67% were married or had a partner. The HRS sample is a representative sample of the U.S. population over age 50.

Measures

Rurality.

For both MIDUS and HRS, we used Beale Rural-Urban Continuum Codes (RUCC) to characterize the extent to which participants reside in urban or rural areas.2 RUCCs represent whether the address in a given county is considered urban, somewhat rural, or rural in relation to its population count and (non-)adjacency to a metro area. These characteristics are represented on a 0–9 scale in 1993 and a 1–9 scale in 2003 and 2013 (e.g., 0 or 1 = counties in metro areas of 1 million population or more; 9 = completely rural or less than 2,500 urban population, not adjacent to a metro area). For MIDUS participants, addresses were linked to time-varying RUCC data such that Wave 1 (1995–1996), Wave 2 (2004–2006), and Wave 3 (2013–2015) were harmonized with RUCC data in 1993, 2003, and 2013, respectively.3 For HRS participants, addresses at each calendar year were linked to both 2003 and 2013 RUCCs. Given that the present study uses data from 2006–2020, we pre-registered to use 2013 RUCCs, and to conduct sensitivity analyses using 2003 RUCCs. We recoded the 1–9 RUCC scale for MIDUS and HRS to be on a 3-point scale, where ‘0’ = RUCCs 1–3 (urban), ‘1’ = RUCCs 4–6 (somewhat rural), and ‘2’ = RUCCs 7–9 (rural).

Big Five Personality Traits.

For both MIDUS and HRS, participants self-reported on their Big Five personality traits using the Midlife Development Inventory Personality adjectives (Lachman & Weaver, 1997) at all timepoints (3 measurement occasions for MIDUS; 4 measurement occasions for HRS). There were 25 items and 26 items total for MIDUS and HRS, respectively, with five items for extraversion (e.g., outgoing, talkative), five items for agreeableness (e.g., caring, warm), four (MIDUS) or five (HRS) items for conscientiousness (e.g., hardworking, responsible), four items for neuroticism (e.g., moody, worrying), and seven items for openness (e.g., imaginative, broadminded). Participants responded to these items on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (a lot) to 4 (not at all). All items were reverse-scored (when appropriate) and averaged together to create Big Five domain composite scores, where higher values represent higher levels of the trait domains.

Psychological Well-Being.

For MIDUS, participants reported on their psychological well-being at the three measurement occasions using 18 items from Ryff’s Psychological Well-Being Scale (Ryff & Keyes, 1995). Generally, these 18 items capture eudaimonic components of well-being such as sense of purpose, environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relations with others, self-acceptance, and autonomy. Response options ranged from 1 (strongly agree) to 7 (strongly disagree). All items were reverse-scored (when appropriate) and averaged together to create a psychological well-being composite score, where higher values represent greater psychological well-being.

For HRS, participants reported on their psychological well-being at the four measurement occasions using a 7-item sense of purpose subscale (Ryff & Keyes, 1995). Therefore, for the HRS participants, we assessed a more narrow conceptualization of psychological well-being. Response options ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). All items were reverse-scored (when appropriate) and averaged together to create a sense of purpose / psychological well-being composite score, where higher values represent greater sense of purpose / psychological well-being.

Life Satisfaction.

For MIDUS, participants reported on their life satisfaction at the three measurement occasions using a single item (Prenda & Lachman, 2001): “How would you rate your life overall these days?”. The response scale ranged from 0 (worst possible) to 10 (best possible). For HRS, participants reported on their life satisfaction at the four measurement occasions using the 5-item Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al., 1985), which has been shown to be highly correlated with single-item measures of life satisfaction (Cheung & Lucas, 2014). The response scale ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).4 The five items were averaged together to create a life satisfaction composite score, where higher values represent greater life satisfaction.

Socio-Demographic and Social Network Covariates.

In both samples, we included several socio-demographic covariates including baseline age, sex, race, ethnicity, household income, education level, employment status, and retirement status. We also assessed two social network covariates: spouse/partner status and time-varying assessments of frequency of social contact.5 In MIDUS, frequency of social contact was measured at each of the three measurement occasions via two items that asked how often the participant was in contact with family members (including siblings, parents, and children) and friends. Response options ranged from 1 (several times a day) to 8 (never or hardly ever). In HRS, frequency of social contact was measured at each of the four measurement occasions via three items that asked how often the participant was in contact with family members (e.g., siblings, parents), their children, and their friends. Response options ranged from 1 (three or more times a week) to 6 (less than once a year or never). For both MIDUS and HRS, we reverse-coded the items and averaged them together into a composite score at each measurement occasion; higher values represent more frequent social contact.

Statistical Analyses

We used R (Version 4.0.4; R Core Team, 2021) and the R-packages ggpubr (Version 0.4.0; Kassambara, 2020), knitr (Version 1.38.1; Xie, 2015), lme4 (Version 1.1.28; Bates et al., 2015), lmerTest (Version 3.1.3; Kuznetsova et al., 2017), papaja (Version 0.1.0.9999; Aust & Barth, 2020), psych (Version 2.2.3; Revelle, 2021), rstatix (Version 0.7.0; Kassambara, 2021), tidyverse (Version 1.3.1; Wickham et al., 2019), and tinytex (Version 0.38.1; Xie, 2019). For the Big Five, psychological well-being, and frequency of social contact variables, we transformed the composites into percent-of-maximum-possible (POMP) scores (0–100), which is a way of standardizing scores to: a) maintain the meaning of scores for within-sample rank-ordering; and b) facilitate comparability across studies when scale anchors and/or number of response options differ (Cohen et al., 1999). Then, we z-scored all participants’ scores at each wave based on the baseline means and standard deviations of the POMP scores to maintain the longitudinal structure of the data and facilitate interpretation. Education level and income were z-scored, and age was centered at 65 years in both samples. To understand the effects of rurality on personality and well-being levels, we used a series of seven random-intercept multilevel models to examine how rurality predicts each Big Five trait and each well-being outcome in separate models. In a second series of models, we added socio-demographic covariates. In a third set of models, we included socio-demographic covariates as well as social network covariates. To understand the effects of rurality on personality and well-being change, we used a series of seven random-intercept, random slope growth curve models to examine how age, rurality, and the interaction between age and rurality (i.e., slopes-as-outcomes models) predict each Big Five trait and each well-being outcome in separate models. In a second series of models, we added socio-demographic covariates. In a third set of models, we included socio-demographic covariates as well as social network covariates. In all models, rurality was entered as a level 1 predictor and allowed to vary across timepoints (i.e., if individuals move counties). Because we have seven outcomes, we evaluated statistical significance at the corrected alpha level of .007 (alpha = .05/7). We report exact p-values, effect sizes, and 99.3% confidence intervals for all results. In MIDUS, the smallest possible sample size of 4,408 and the alpha level of .007 provided 80% statistical power to estimate standardized r effects of approximately .05 or larger. In HRS, the sample size of 15,317 and the alpha level of .007 provided 80% statistical power to estimate standardized r effects of approximately .02 or larger.

Results

As can be seen in Figure S1 (supplemental material) and consistent with national averages (Bureau, 2010; Kusmin, 2016), the vast majority of MIDUS and HRS participants live in urban, metropolitan areas (RUCCs 1–3), whereas fewer participants live in somewhat rural/surburban (RUCCs 4–6) or very rural (RUCCs 7–9) areas. Table 1 shows descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, alphas) for the Big Five personality traits, psychological well-being, and life satisfaction. Tables S1–S2 (supplemental material) contain correlation matrices among the main study variables at baseline for MIDUS and HRS, respectively. As has been shown before, correlations across measurement occasions for extraversion (rs = 0.69–0.73), agreeableness (rs = 0.62–0.66), conscientiousness (rs = 0.61–0.66), neuroticism (rs = 0.64–0.66), openness (rs = 0.68–0.71), psychological well-being (rs = 0.60–0.68), and life satisfaction (rs = 0.45–0.56) indicate moderate stability over time. The RUCC variables were highly correlated across measurement occasions (rs = 0.76–0.84 and 0.93–0.94 for MIDUS and HRS, respectively), suggesting that few participants are: a) moving, or b) moving to counties that vary considerably in rural-urban characteristics from their prior residence(s). To investigate the potential impact of attrition, we compared individuals who did and did not participate in the final follow-up assessment on study variables assessed at Time 1 (i.e., Big Five personality traits, psychological well-being, life satisfaction, socio-demographic and social network covariates). People who were women, younger, had higher education levels and incomes, were employed and not retired, had a spouse or partner, were more conscientious, less neurotic, and had higher levels of psychological well-being and life satisfaction at T1 were more likely to participate in the studies at the final assessment, though there were some slight differences in systematic attrition across MIDUS and HRS (see Tables S3–S4 for the full results).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Personality and Well-Being Variables in MIDUS and HRS

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Wave 4 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N | M | SD | Alpha | N | M | SD | Alpha | N | M | SD | Alpha | N | M | SD | Alpha |

| MIDUS | ||||||||||||||||

| E | 6,271 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.78 | 4,012 | −0.17 | 1.02 | 0.76 | 2,908 | −0.32 | 1.11 | 0.75 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| A | 6,271 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.81 | 4,011 | −0.09 | 1.03 | 0.80 | 2,909 | −0.30 | 1.18 | 0.77 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| C | 6,270 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.56 | 4,012 | 0.09 | 1.02 | 0.58 | 2,909 | −0.04 | 1.14 | 0.56 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| N | 6,265 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.75 | 4,009 | −0.25 | 0.95 | 0.74 | 2,907 | −0.26 | 0.94 | 0.72 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| O | 6,264 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.78 | 3,975 | −0.22 | 1.02 | 0.77 | 2,905 | −0.23 | 1.03 | 0.77 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| PWB | 6,287 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.80 | 4,026 | 0.01 | 1.02 | 0.83 | 2,916 | −0.06 | 1.03 | 0.82 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| LS | 6,236 | 0.00 | 1.00 | NA | 3,987 | 0.07 | 0.94 | NA | 2,834 | 0.09 | 0.98 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| HRS | ||||||||||||||||

| E | 14,537 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.74 | 15,422 | −0.04 | 1.03 | 0.75 | 13,688 | −0.03 | 1.04 | 0.75 | 10,231 | −0.05 | 1.05 | 0.75 |

| A | 14,552 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.78 | 15,415 | −0.04 | 1.05 | 0.78 | 13,677 | −0.06 | 1.07 | 0.79 | 10,230 | −0.08 | 1.08 | 0.79 |

| C | 14,515 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.66 | 15,404 | 0.03 | 1.02 | 0.67 | 13,662 | 0.01 | 1.03 | 0.66 | 10,217 | 0.03 | 1.04 | 0.67 |

| N | 14,482 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.71 | 15,357 | −0.05 | 1.00 | 0.71 | 13,624 | −0.12 | 1.00 | 0.71 | 10,185 | −0.14 | 0.99 | 0.71 |

| O | 14,445 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.79 | 15,342 | −0.02 | 1.02 | 0.79 | 13,621 | −0.03 | 1.05 | 0.80 | 10,182 | 0.00 | 1.04 | 0.80 |

| PWB | 14,435 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.74 | 15,319 | 0.04 | 1.02 | 0.77 | 13,644 | −0.01 | 1.01 | 0.76 | 10,147 | 0.03 | 1.00 | 0.76 |

| LS | 14,568 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.88 | 15,505 | −0.15 | 1.03 | 0.88 | 13,763 | −0.04 | 0.99 | 0.89 | 10,282 | 0.00 | 0.98 | 0.88 |

Note. E = Extraversion; A = Agreeableness; C = Conscientiousness; N = Neuroticism; O = Openness; PWB = Psychological Well-Being; LS = Life Satisfaction

As a preliminary step, we inspected the intraclass correlation coefficients of the Big Five personality traits, psychological well-being, and life satisfaction, which characterize the extent of between- vs. within-person variability in scores. Generally, half to two-thirds of the variation in the Big Five personality traits, well-being, and life satisfaction were due to between-person differences, whereas half to one-third of the variation in scores were due to within-person differences over time (see Figure S2 in the supplemental material), supporting the use of multilevel models to characterize levels and change in personality and well-being among older adults.

Is Rurality Associated with Levels of Personality Traits and Well-Being?

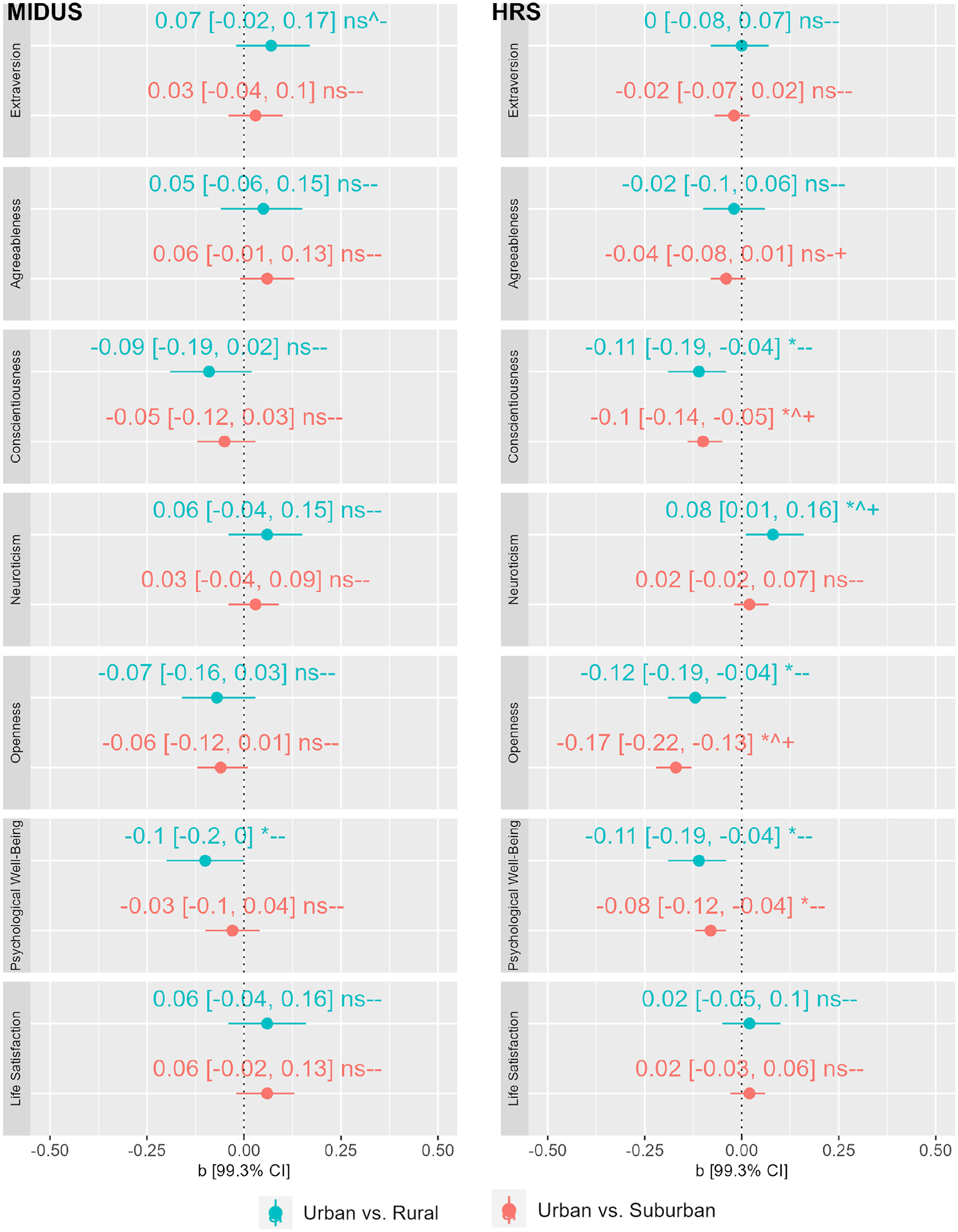

Figure 1 shows effect sizes and confidence intervals from the multilevel models of rural-urban differences in personality and well-being levels in MIDUS and HRS. For the full results, including sample sizes and r-square values, please see Tables S5–S18. In the HRS sample, compared to people who lived in urban contexts (RUCCs 1–3), people who lived in suburban (RUCCs 4–6) and the most rural (RUCCs 7–9) contexts tended to have lower levels of conscientiousness. Further, compared to people who lived in urban contexts (RUCCs 1–3), people who lived in suburban (RUCCs 4–6) and the most rural (RUCCs 7–9) contexts tended to have lower levels of openness. These rural-urban differences were robust to the inclusion of sociodemographic and social network covariates for those who lived in urban (RUCCs 1–3)vs. suburban contexts (RUCCs 4–6), but there were no differences between urban (RUCCs 1–3) and the most rural (RUCCs 7–9) contexts in conscientiousness or openness after including socio-demographic and social network covariates. Moreover, in HRS, there were rural-urban differences in levels of neuroticism, such that people who lived in the most rural contexts (RUCCs 7–9) tended to have higher levels of neuroticism compared to people who lived in urban contexts (RUCCs 1–3); and these rural-urban differences were robust to the inclusion of sociodemographic and social network covariates. In both MIDUS and HRS, we observed rural-urban differences in psychological well-being, such that individuals who lived in the most rural contexts (RUCCs 7–9) tended to have lower levels of psychological well-being than individuals who lived in the most urban contexts (RUCCs 1–3). However, these findings became non-significant with the inclusion of sociodemographic and social network covariates. There were no statistically significant rural-urban differences in levels of extraversion, agreeableness, or life satisfaction in MIDUS and HRS (all ps > .007).

Figure 1.

Forest plot of multilevel model effects of rurality-urbanicity on personality and well-being in MIDUS and HRS.

Note.

ns = non-significant in model without covariates

* = significant in model with no covariates

- = non-significant in models with sociodemographic and social network covariates

^ = significant in models with sociodemographic covariates

+ = significant in models with sociodemographic and social network covariates

Is Rurality Associated With Change in Personality Traits and Well-Being?

The interactions between rurality and age were non-significant for the Big Five, psychological well-being, and life satisfaction in both MIDUS and HRS (all ps > .007), suggesting there are no rural-urban differences in personality and well-being change across older adulthood in these samples. For the full results, including sample sizes and r-square values, please see tables S19–S32.

Sensitivity Analyses

For HRS, we repeated all analyses using rurality codes based on 2003 population data (rather than 2013 population data), and all reported effects remain the same in terms of magnitude and statistical significance.6

Discussion

The present study leveraged data from two large longitudinal studies of U.S. American adults, spanning multiple decades of adulthood, to understand the extent to which there are rural-urban differences in levels and changes in the Big Five personality traits and two domains of well-being. Generally, we found rural-urban differences in levels of conscientiousness, neuroticism, openness, and psychological well-being, with some nuances when sociodemographic and social network covariates were included. However, there were no rural-urban differences in changes in the Big Five personality traits, psychological well-being, or life satisfaction across adulthood. Below, we elaborate on these findings by contextualizing them within the broader literature and providing some theoretical and practical implications for future research and health policy.

In terms of rural-urban differences in levels of the Big Five, we observed several patterns for HRS (but not MIDUS) participants. First, compared to Americans who lived in more urban areas, Americans who lived in more rural areas tended to have lower levels of openness, consistent with our pre-registered hypothesis and prior empirical work (Ebert et al., 2021; Elleman et al., 2022; Greaves et al., 2015; Jokela et al., 2015; Rentfrow et al., 2015). Moreover, we did not have any hypotheses concerning conscientiousness and neuroticism, but we did find that people who lived in more rural areas tended to have lower levels of conscientiousness and higher levels of neuroticism, compared to people who lived in more urban areas. These associations between rurality and personality levels were largely robust to the inclusion of sociodemographic (i.e., age, sex, race, ethnicity, household income, education level, employment status, retirement status) and social network (i.e., partner status, frequency of social contact) covariates, suggesting that the effects of rurality on individual differences in openness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism cannot be solely explained by socio-demographic and social network factors that co-occur with rural residence. Instead, to the extent that there are partial mediating processes at play, it is possible that sociodemographic and social network indicators are pieces of the ecological, social, and structural mechanisms that lead to rural-urban differences in levels of openness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism. For example, Americans who live in rural areas tend to have less access to high-quality schools and fewer socioeconomic resources (e.g., Long et al., 2018), which is likely to be directly related to lower educational attainment, and previous research has shown that lower educational attainment is associated with lower levels of openness and conscientiousness (Sutin et al., 2017). Further, it is possible that people who are more open or conscientious prefer urban locations because of the cultural and achievement-oriented amenities that can be provided in such an environment (e.g., Götz et al., 2021; Sevincer et al., 2017). It will not only be important for future research to directly test possible mediating pathways that link rural-urban residences to personality differences, but with equity and social justice in mind, it will be critical for future research to identify the ways in which characteristics and experiences of rural communities can be leveraged to promote positive personality tendencies, health behaviors, outcomes, and longevity. For example, rural America is characterized by homogeneous population groups, sharing similar racial, ethnic, income, and educational backgrounds (Lichter et al., 2007), and areas of higher racial and ethnic concentrations also tend to survive and protect themselves through strong social cohesion as a strategy to preserve culture and create security. There may be ways to leverage social cohesion and cultural values to promote positive personality tendencies, health behaviors, and longevity among rural Americans.

In terms of rural-urban differences in levels of well-being, we observed that individuals who lived in more rural areas tended to have lower levels of psychological well-being, compared to individuals who lived in more urban areas. This was true for both MIDUS and HRS participants; however, these effects were not robust to the inclusion of socio-demographic and social network covariates. Moreover, there were no rural-urban differences in life satisfaction in either study, contrary to our hypotheses and large body of empirical work (e.g., Buecker et al., 2021; Burger et al., 2020; Hoogerbrugge & Burger, 2022; Wang & Wang, 2016). This pattern of results is intriguing because it suggests that rural and urban residents have similar levels of life satisfaction, and that rural-urban differences in psychological well-being may be explained by the co-occurrence of rurality with sociodemographic and social network factors. In other words, socio-demographic and social network factors may play a larger role for psychological well-being and life satisfaction than rurality-urbanicity itself. Consistent with this interpretation, mental illness prevalence tends to be similar across rural and urban areas, but access to mental health resources (which often co-occurs with fewer socioeconomic resources and lack of infrastructure) are notably limited for rural residents. Since 2010, there has been a surge in rural hospital closures that has also contributed to a reduction in the healthcare provider workforce, including mental health professionals. Almost 85% of all rural counties have a mental health professional shortage (Probst et al., 2019), despite rural residents desiring more psychological services (Richie et al., 2022). Future research should directly investigate the role of access to mental health care services, socioeconomic resources, and social networks to better understand whether these factors account for individual differences on psychological well-being and life satisfaction among rural and urban adults.

Interestingly, there were no rural-urban differences in changes in personality and well-being. That is, rural and urban Americans did not differ in their age-graded trajectories of personality and well-being. There are three possible explanations for these results. First, it is possible that the true effect is indeed null. In this case, while there are rural-urban differences in levels of some aspects of personality and well-being, rural and urban Americans tend to have homogeneous patterns of change. To the extent that personality and well-being changes are rooted in universal, developmental milestones common to all humans, as is suggested by biological and social role models of psychological development (e.g., Atherton et al., 2020), then the null effects of rurality-urbanicity on personality and well-being change may not be all that surprising. Relatedly, although the effects of rurality-urbanicity on personality and well-being change may be null, prior work has shown evidence for the opposite pathway: personality traits and well-being needs predict where people migrate to (see Ciani & Capiluppi, 2011; Glauber et al., 2022; Hoogerbrugge & Burger, 2022; Jokela et al., 2020; Yoshino & Oshio, 2022). This pattern of findings highlights an important delineation of socialization (rurality-urbanicity → personality/well-being) and selective migration effects (personality/well-being → living in rural or urban place) that are worth attending to when interpreting the complex and dynamic associations among macro-level contexts and personality traits and well-being (see Götz et al., 2021 for an example). The literature on selective migration has shown that rural-urban happiness differentials are partially explained by selective migration (Hoogerbrugge & Burger, 2022). Further, higher levels of Openness are related to heightened rural-to-urban migration in Japan (Yoshino & Oshio, 2022) and Australia (Jokela et al., 2020), and higher levels of Conscientiousness are related to rural-to-urban migration in Australia (Jokela et al., 2020). In sum, people want to live in places that “fit” with their personality tendencies and well-being needs (e.g., Bleidorn et al., 2016; Rentfrow et al., 2008; Rentfrow & Jokela, 2016); and therefore, they migrate (or do not migrate) to rural or urban locations as a result of those tendencies and needs (e.g., Ayhan et al., 2017; Jokela, 2020; McCann, 2015). Once individuals arrive in locations that fit their dispositional tendencies and well-being needs, it is possible there is less room for rurality-urbanicity to subsequently affect how personality and well-being changes after that. However, this is an open question for future research to examine.

Second, it is possible that the true effect of rurality-urbanicity on personality traits and well-being is null among middle and older adults, but is not null earlier in the lifespan. The MIDUS and HRS samples tend to primarily assess individuals in middle and older adulthood (median ages are 45 and 68, respectively); however, aligned with some popular ideas about lifespan development, environmental influences on psychological development may have the strongest effects earlier in the lifespan, before dissipating across the rest of the lifespan. This may be especially true in light of selective migration processes. There is more residential mobility among younger populations than older populations, with the vast majority of younger populations migrating to urban locations (Glauber, 2022; Rentfrow et al., 2008; Rentfrow & Jokela, 2016). Thus, it is possible that the effects of rurality-urbanicity on personality and well-being change happens earlier in the lifespan than we were able to capture in this study.

Third, it is possible that we spuriously observed null effects in MIDUS and HRS. Although this is less likely by using data from two large longitudinal studies, burgeoning coordinated data analyses (with upwards of 15 longitudinal studies) have shown that effect sizes can vary considerably across studies (e.g., Graham et al., 2017, 2020). Therefore, the present study may only capture a small range of possible effect sizes, which we would otherwise observe if we had included a larger number of studies, or more frequent measurement occasions, in this investigation. Another possible explanation for the null effects is that the amount of personality and well-being change for MIDUS and HRS participants is rather small. This lack of variability in personality and well-being change means that there is less variation for rurality-urbanicity to account for, which may have led us to estimate zero-to-small effect sizes. However, at present, it is not clear whether the lack of variation in personality and well-being change in these samples is substantively meaningful or a methodological artifact.

Limitations

The present study has several limitations that future research should consider when building upon this work. First, both the MIDUS and HRS samples overrepresent White Americans, 90% and 74% of the samples respectively, despite comprising approximately 60% of the U.S. population in 2020 (Jones et al., 2021). Although White Americans comprise 75% of rural areas (Cromartie, 2018), we potentially underestimated effect sizes by underrepresenting immigrant and racial minority experiences in the present study, given that rural health disparities disproportionately affect immigrant and racial and ethnic minority groups compared to White Americans, due to xenophobia, racism, segregation, and discrimination (e.g., James et al., 2017; Smith & Trevelyan, 2019). Second, there was notable systematic attrition, suggesting that effect sizes may be biased due to the sample becoming less representative in their personalities, well-being, and socio-demographic characteristics over time. Third, we do not know the extent to which the present results generalize to other countries. To the extent that other nations have rural disparities in terms of social, socioeconomic, and structural resources, we might expect the mechanisms linking rurality-urbanicity to personality traits and well-being to be similar. However, it is also likely that there are unique characteristics of rural populations in different countries around the world that would differentially impact levels and changes in personality and well-being. Fourth, the effect sizes of the statistically significant results are rather small (ranging from −.17 to .07); and thus, the real-world impact of these findings are potentially small too. However, some researchers have noted that small effect sizes in longitudinal studies may translate into larger and meaningful effects because they repeat and accumulate across years and decades (Funder & Ozer, 2019). Ultimately, the real-world impact and value of the present results will become evident with future replications, studies of generalizability, and conversations among researchers, policy-makers, and stakeholders about the value of these findings to rural and urban communities. Fifth, although the Big Five personality traits were measured in the same way across MIDUS and HRS, the psychological well-being operationalization (i.e., psychological well-being in MIDUS; sense of purpose in HRS) and life satisfaction measures (i.e., 5- vs. 1-item) differed across studies. These measurement differences may introduce some statistical noise that renders the results less directly comparable across studies. Sixth, the present research is limited by our classification of rural-urban areas. To date, there are over 15 classifications of rurality-urbanicity and each classification system has limitations for adequately defining rural regions (e.g., Cromartie & Bucholtz, 2008; Ratcliffe et al., 2018). Prior work has examined how different rural classification systems are related to health outcomes, like cancer risk (Hirko et al., 2022), but researchers have yet to examine the predictive validity of these different rurality measures for personality traits and well-being. Last, we did observe some discrepant Big Five personality findings between the MIDUS and HRS samples, with a notable swath of null effects for the MIDUS sample in particular. This is somewhat puzzling given that both MIDUS and HRS have large sample sizes, are relatively homogeneous in socio-demographic make-up, and administer the same measure of personality. Given the large sample sizes and relatively small effects, we caution readers against overinterpreting HRS results that were not replicated in MIDUS.

Taken together, the present study fills important gaps in the literature regarding our understanding of the effects of rurality-urbanicity on levels of, and changes in, personality and well-being across adulthood, while simultaneously raising more questions for future work to explore. The current investigation has important implications for both personality psychology and rural health. Our results suggest that one macro-level factor – the extent to which a person lives in a rural or urban area – has little impact on American adult personality and well-being development, contributing the bountiful literature by personality psychologists to identify biopsychosocial and structural factors that lead adults to increase, decrease, or not change much at all in their personalities and well-being as they get older. The present paper also has important implications for the rural health literature. Given the far-reaching consequences of rural health disparities for individuals, families, and communities, there is a pressing need to identify the psychological, social, and structural mechanisms responsible for disparities and the ways in which to intervene upon those mechanisms to improve the health of rural Americans. Leveraging information about individuals’ personality traits and well-being may be one way to understand rural-urban disparities in health outcomes and longevity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Aging including R01-AG018436 to Daniel K. Mroczek; K99-AG071838 to Emily C. Willroth; and P30-AG059988 to Marquita W. Lewis-Thames, as well as a grant from the National Cancer Institute awarded to Marquita W. Lewis-Thames (K01-CA262342). This work was also supported by funds from the Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute (UL1TR001422), the Respiratory Health Association of Metropolitan Chicago (RHA2020-01), and the Northwestern University Center for Community Health, all to Marquita W. Lewis-Thames. Publicly available data from the MIDUS study was used for this research. Since 1995 the MIDUS study has been funded by the following: John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Research Network; National Institute on Aging (P01-AG020166); National institute on Aging (U19-AG051426). The majority of the work was conducted while OEA was at Northwestern University, but her current affiliation is the University of Houston. The pre-registrations, R code, and Rmarkdown documents can be found on the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/fmuvq/. We have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

The authors made the following contributions. Olivia E. Atherton: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing; Emily C. Willroth: Conceptualization, Writing - Review & Editing; Eileen K. Graham: Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing; Jing Luo: Conceptualization, Writing - Review & Editing; Daniel K. Mroczek: Conceptualization, Writing - Review & Editing; Marquita W. Lewis-Thames: Conceptualization, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing.

To our knowledge, no prior work with the MIDUS and HRS data has examined rurality in conjunction with the personality and/or well-being variables.

These data are under restricted access for researchers. To obtain rurality data for MIDUS, please see: http://midus.wisc.edu/data/MIDUS_Geo-coding_README_20211021.pdf. To obtain rurality data for HRS, please see: https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/data-products/restricted-data.

Note that 2013 RUCC are not directly comparable with the codes prior to 2000 because of the new methodology used in developing the 2000 metropolitan areas. See the Documentation here: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes/documentation/. The 1993 codes are only different such that: 0 = central counties of metro areas of 1 million population or more; and 1 = fringe counties of metro areas of 1 million population or more. The remaining 2–9 categories are the same as what is indicated in 2003 and 2013. Thus, for 1993, we recoded ‘0’ as ‘1’ to be on a comparable scale to the 2003 and 2013 RUCCs, ranging from 1 to 9.

In HRS 2006, the response scale differed such that there were 6 labeled response options (instead of 7), and the midpoint (neither agree nor disagree) was missing. We recoded the 2006 scale to include an all-missing midpoint; this approach makes it so that the 2006 scale ranges from 1 to 7 (and the POMP scores reflect the same maximum possible), which is consistent with subsequent waves and maximizes comparability across measurement occasions for modeling life satisfaction change.

We chose these particular covariates because prior work has suggested that sociodemographic (i.e., sex, race, ethnicity, household income, education level, employment status, retirement status) and social network (i.e., spouse/partner status, frequency of social contact) factors are sometimes related to both our independent (rurality-urbanicity) and dependent (personality traits, psychological well-being, life satisfaction) variables; and thus, may confound observed associations between rurality and personality and well-being.

We also repeated all analyses while specifying rurality as a continuous variable rather than a categorical variable, and all of the results mirror the patterns of significant and non-significant findings we observed when examining rurality as a categorical variable (with three groups).

References

- Allik J, Realo A, Mõttus R, Pullmann H, Trifonova A, McCrae RR, … Survey P (2009). Personality traits of russians from the observer’s perspective. European Journal of Personality, 23(7), 567–588. [Google Scholar]

- Arya T, & Sangwan S (2018). A study on psychological well-being of rural and urban adolescents. International Journal of Education and Management Studies, 8(4), 419–423. [Google Scholar]

- Atherton OE, Donnellan MB, & Robins RW (2020). Development of personality across the life span.

- Atherton OE, Sutin AR, Terracciano A, & Robins RW (2021). Stability and change in the big five personality traits: Findings from a longitudinal study of mexican-origin adults. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aust F, & Barth M (2020). papaja: Create APA manuscripts with R Markdown. Retrieved from https://github.com/crsh/papaja

- Ayhan S, Gatskova K, & Lehmann H (2017). The impact of non-cognitive skills and risk preferences on rural-to-urban migration: Evidence from ukraine.

- Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, & Walker S (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. 10.18637/jss.v067.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bleidorn W, Klimstra TA, Denissen JJ, Rentfrow PJ, Potter J, & Gosling SD (2013). Personality maturation around the world: A cross-cultural examination of social-investment theory. Psychological Science, 24(12), 2530–2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleidorn W, Schönbrodt F, Gebauer JE, Rentfrow PJ, Potter J, & Gosling SD (2016). To live among like-minded others: Exploring the links between person-city personality fit and self-esteem. Psychological Science, 27(3), 419–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brim OG, Ryff CD, Kessler RC (2004). The MIDUS national survey: An overview. How Healthy Are We, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Buecker S, Ebert T, Götz FM, Entringer TM, & Luhmann M (2021). In a lonely place: Investigating regional differences in loneliness. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 12(2), 147–155. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau U (2010). Census urban and rural classification and urban area criteria. Library Catalog: Www. Census. Gov Section: Government. [Google Scholar]

- Burger MJ, Morrison PS, Hendriks M, & Hoogerbrugge MM (2020). Urban-rural happiness differentials across the world. World Happiness Report, 2020, 66–93. [Google Scholar]

- Camperio Ciani AS, Capiluppi C, Veronese A, & Sartori G (2007). The adaptive value of personality differences revealed by small island population dynamics. European Journal of Personality: Published for the European Association of Personality Psychology, 21(1), 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ciani AC, & Capiluppi C (2011). Gene flow by selective emigration as a possible cause for personality differences between small islands and mainland populations. European Journal of Personality, 25(1), 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung F (2018). Income redistribution predicts greater life satisfaction across individual, national, and cultural characteristics. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 115(5), 867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung F, & Lucas RE (2014). Assessing the validity of single-item life satisfaction measures: Results from three large samples. Quality of Life Research, 23(10), 2809–2818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen P, Cohen J, Aiken LS, & West SG (1999). The problem of units and the circumstance for POMP. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 34(3), 315–346. [Google Scholar]

- Cromartie J (2018). Rural america at a glance 2018 edition.

- Cromartie J, & Bucholtz S (2008). Defining the” rural” in rural America (No. 1490–2016-127511, pp. 28–35).

- Diener ED, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, & Griffin S (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener ED, Kahneman D, & Helliwell J (2010). International differences in well-being. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Diener ED, Oishi S, & Lucas RE (2015). National accounts of subjective well-being. American Psychologist, 70(3), 234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobis EA, Krumel TP, Cromartie J, Conley KL, Sanders A, & Ortiz R (2021). Rural america at a glance: 2021 edition.

- Douthit N, Kiv S, Dwolatzky T, & Biswas S (2015). Exposing some important barriers to health care access in the rural USA. Public Health, 129(6), 611–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert T, Gebauer JE, Brenner T, Bleidorn W, Gosling SD, Potter J, & Rentfrow PJ (2021). Are regional differences in psychological characteristics and their correlates robust? Applying spatial-analysis techniques to examine regional variation in personality. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1745691621998326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elleman LG, Condon DM, Russin SE, & Revelle W (2018). The personality of US states: Stability from 1999 to 2015. Journal of Research in Personality, 72, 64–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elleman LG, Condon DM, Holtzman NS, Allen VR, & Revelle W (2020). Smaller is better: Associations between personality and demographics are improved by examining narrower traits and regions. Collabra: Psychology, 6(1). [Google Scholar]

- Friedman HS, Kern ML, & Reynolds CA (2010). Personality and health, subjective well-being, and longevity. Journal of Personality, 78(1), 179–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glauber R (2022). Rural depopulation and the rural-urban gap in cognitive functioning among older adults. The Journal of Rural Health. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Götz FM, Ebert T, & Rentfrow PJ (2018). Regional cultures and the psychological geography of switzerland: Person–environment–fit in personality predicts subjective wellbeing. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Götz FM, Stieger S, Gosling SD, Potter J, & Rentfrow PJ (2020). Physical topography is associated with human personality. Nature Human Behaviour, 4(11), 1135–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Götz FM, Yoshino S, & Oshio A (2020). The association between walkability and personality: Evidence from a large socioecological study in Japan. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 69, 101438. [Google Scholar]

- Götz FM, Ebert T, Gosling SD, Obschonka M, Potter J, & Rentfrow PJ (2021). Local housing market dynamics predict rapid shifts in cultural openness: A 9-year study across 199 cities. American Psychologist, 76(6), 947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham EK, Rutsohn JP, Turiano NA, Bendayan R, Batterham PJ, Gerstorf D, … et al. (2017). Personality predicts mortality risk: An integrative data analysis of 15 international longitudinal studies. Journal of Research in Personality, 70, 174–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham EK, Weston SJ, Gerstorf D, Yoneda TB, Booth T, Beam CR, … et al. (2020). Trajectories of big five personality traits: A coordinated analysis of 16 longitudinal samples. European Journal of Personality, 34(3), 301–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greaves LM, Cowie LJ, Fraser G, Muriwai E, Huang Y, Milojev P, … et al. (2015). Regional differences and similarities in the personality of new zealanders. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 44(1). [Google Scholar]

- Hakulinen C, Elovainio M, Batty GD, Virtanen M, Kivimäki M, & Jokela M (2015). Personality and alcohol consumption: Pooled analysis of 72,949 adults from eight cohort studies. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 151, 110–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirko KA, Xu H, Rogers LQ, Martin MY, Roy S, Kelly KM, … & Ford S (2022). Cancer disparities in the context of rurality: risk factors and screening across various US rural classification codes. Cancer Causes & Control, 33(8), 1095–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogerbrugge M, & Burger M (2022). Selective migration and urban–rural differences in subjective well-being: Evidence from the United Kingdom. Urban Studies, 59(10), 2092–2109. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson NW, Lucas RE, & Donnellan MB (2019). The development of subjective well-being across the lifespan.

- James CV, Moonesinghe R, Wilson-Frederick SM, Hall JE, Penman-Aguilar A, & Bouye K (2017). Racial/ethnic health disparities among rural adults-united states, 2012–2015. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 66(23), 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jokela M (2020). Selective residential mobility and social influence in the emergence of neighborhood personality differences: Longitudinal data from australia. Journal of Research in Personality, 86, 103953. [Google Scholar]

- Jokela M, Airaksinen J, Kivimäki M, & Hakulinen C (2018). Is within–individual variation in personality traits associated with changes in health behaviours? Analysis of seven longitudinal cohort studies. European Journal of Personality, 32(6), 642–652. [Google Scholar]

- Jokela M, Bleidorn W, Lamb ME, Gosling SD, & Rentfrow PJ (2015). Geographically varying associations between personality and life satisfaction in the london metropolitan area. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(3), 725–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jokela M, Pulkki-Råback L, Elovainio M, & Kivimäki M (2014). Personality traits as risk factors for stroke and coronary heart disease mortality: Pooled analysis of three cohort studies. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 37(5), 881–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones N, Marks R, Ramirez R, & Rıós-Vargas M (2021). 2020 census illuminates racial and ethnic composition of the country. United States Census Bureau. Http://Census.Gov/Library/Store. Accessed, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Kassambara A (2020). Ggpubr: ‘ggplot2’ based publication ready plots. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggpubr

- Kassambara A (2021). Rstatix: Pipe-friendly framework for basic statistical tests. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rstatix

- Kushlev K, Drummond DM, & Diener E (2020). Subjective well-being and health behaviors in 2.5 million americans. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 12(1), 166–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusmin L (2016). Rural america at a glance. United states department of agriculture. Economic Research Service. [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova A, Brockhoff PB, & Christensen RHB (2017). lmerTest package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. Journal of Statistical Software, 82(13), 1–26. 10.18637/jss.v082.i13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman ME, & Weaver SL (1997). The midlife development inventory (MIDI) personality scales: Scale construction and scoring. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Thames MW, Fank P, Gates M, Robinson K, Delfino K, Paquin Z, … Molina Y (2022). Consequences of structural urbanism: Urban–rural differences in cancer patients’ use and perceived importance of supportive care services from a 2017–2018 midwestern survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(6), 3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Thames MW, Langston ME, Fuzzell L, Khan S, Moore JX, & Han Y (2020). Rural-urban differences e-cigarette ever use, the perception of harm, and e-cigarette information seeking behaviors among US adults in a nationally representative study. Preventive Medicine, 130, 105898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT, Parisi D, Grice SM, & Taquino MC (2007). National estimates of racial segregation in rural and small-town america. Demography, 44(3), 563–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long AS, Hanlon AL, & Pellegrin KL (2018). Socioeconomic variables explain rural disparities in US mortality rates: Implications for rural health research and policy. SSM-Population Health, 6, 72–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews KA, Croft JB, Liu Y, Lu H, Kanny D, Wheaton AG, … (2017). Health-related behaviors by urban-rural county classification-united states, 2013. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 66(5), 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann SJ (2015). Big five personality and residential mobility: A state-level analysis of the USA. The Journal of Social Psychology, 155(3), 274–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, & Terracciano A (2005). Universal features of personality traits from the observer’s perspective: Data from 50 cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(3), 547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, & Terracciano A (2008). The five-factor model and its correlates in individuals and cultures. Multilevel Analysis of Individuals and Cultures, 249–283. [Google Scholar]

- Moy E, Garcia MC, Bastian B, Rossen LM, Ingram DD, Faul M, … (2017). Leading causes of death in nonmetropolitan and metropolitan areas-united states, 1999–2014. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 66(1), 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray G, Judd F, Jackson H, Fraser C, Komiti A, Hodgins G, … & Robins G (2005). The five factor model and accessibility/remoteness: Novel evidence for person–environment interaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 39(4), 715–725. [Google Scholar]

- Obschonka M, Wyrwich M, Fritsch M, Gosling SD, Rentfrow PJ, & Potter J (2019). Von unterkühlten Norddeutschen, gemütlichen Süddeutschen und aufgeschlossenen Großstädtern: Regionale Persönlichkeitsunterschiede in Deutschland. Psychologische Rundschau, 70(3), 173–194. [Google Scholar]

- Oishi S, Diener E, Lucas RE, & Suh EM (2009). Cross-cultural variations in predictors of life satisfaction: Perspectives from needs and values. In Culture and well-being (pp. 109–127). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Okely JA, & Gale CR (2016). Well-being and chronic disease incidence: The english longitudinal study of ageing. Psychosomatic Medicine, 78(3), 335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesta BJ, Bertsch S, McDaniel MA, Mahoney CB, & Poznanski PJ (2012). Differential epidemiology: IQ, neuroticism, and chronic disease by the 50 US states. Intelligence, 40(2), 107–114. [Google Scholar]

- Plaut VC, Markus HR, & Lachman ME (2002). Place matters: Consensual features and regional variation in american well-being and self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(1), 160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prenda KM, & Lachman ME (2001). Planning for the future: A life management strategy for increasing control and life satisfaction in adulthood. Psychology and Aging, 16(2), 206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Probst J, Eberth JM, & Crouch E (2019). Structural urbanism contributes to poorer health outcomes for rural america. Health Affairs, 38(12), 1976–1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved from https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe M, Burd C, Holder K, & Fields A (2016). Defining rural at the US Census Bureau. American community survey and geography brief, 1(8), 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Rentfrow PJ (2010). Statewide differences in personality: Toward a psychological geography of the united states. American Psychologist, 65(6), 548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rentfrow PJ, Gosling SD, Jokela M, Stillwell DJ, Kosinski M, & Potter J (2013). Divided we stand: Three psychological regions of the united states and their political, economic, social, and health correlates. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105(6), 996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rentfrow PJ, Gosling SD, & Potter J (2008). A theory of the emergence, persistence, and expression of geographic variation in psychological characteristics. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(5), 339–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rentfrow PJ, & Jokela M (2016). Geographical psychology: The spatial organization of psychological phenomena. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 25(6), 393–398. [Google Scholar]

- Rentfrow PJ, Jokela M, & Lamb ME (2015). Regional personality differences in great britain. PloS One, 10(3), e0122245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rentfrow PJ, Mellander C, & Florida R (2009). Happy states of america: A state-level analysis of psychological, economic, and social well-being. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(6), 1073–1082. [Google Scholar]

- Revelle W (2021). Psych: Procedures for psychological, psychometric, and personality research. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych [Google Scholar]

- Richie FJ, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J, Kaniuka A, Wilsey CN, Mennicke A, Harris Y-J, … Cramer RJ (2022). Mental health services for all: Factors influencing desire for mental health services among underresourced adults during COVID-19. Psychological Services. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, & Keyes CLM (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AS, & Trevelyan E (2019). The older population in rural america: 2012–2016. US Department of Commerce, Economics; Statistics Administration, US. [Google Scholar]

- Sonnega A, Faul JD, Ofstedal MB, Langa KM, Phillips JW, & Weir DR (2014). Cohort profile: The health and retirement study (HRS). International Journal of Epidemiology, 43(2), 576–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto CJ (2019). How replicable are links between personality traits and consequential life outcomes? The life outcomes of personality replication project. Psychological Science, 30(5), 711–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strosnider H, Kennedy C, Monti M, & Yip F (2017). Rural and urban differences in air quality, 2008–2012, and community drinking water quality, 2010–2015-united states. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 66(13), 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutin AR, Luchetti M, Stephan Y, Robins RW, & Terracciano A (2017). Parental educational attainment and adult offspring personality: An intergenerational life span approach to the origin of adult personality traits. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 113(1), 144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutin AR, Stephan Y, Luchetti M, Artese A, Oshio A, & Terracciano A (2016). The five-factor model of personality and physical inactivity: A meta-analysis of 16 samples. Journal of Research in Personality, 63, 22–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC, & Suh EM (2002). Cultural influences on personality. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 133–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turiano NA, Pitzer L, Armour C, Karlamangla A, Ryff CD, & Mroczek DK (2012). Personality trait level and change as predictors of health outcomes: Findings from a national study of americans (MIDUS). Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67(1), 4–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USDA Economic Research Service. (2019). https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/rural-economy-population/rural-classifications/what-is-rural/

- Wang F, & Wang D (2016). Place, geographical context and subjective well-being: State of art and future directions. Mobility, sociability and well-being of urban living, 189–230. [Google Scholar]

- Wei W, Lu JG, Galinsky AD, Wu H, Gosling SD, Rentfrow PJ, … et al. (2017). Regional ambient temperature is associated with human personality. Nature Human Behaviour, 1(12), 890–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H, Averick M, Bryan J, Chang W, McGowan LD, François R, … Yutani H (2019). Welcome to the tidyverse. Journal of Open Source Software, 4(43), 1686. 10.21105/joss.01686 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y (2015). Dynamic documents with R and knitr (2nd ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: Chapman; Hall/CRC. Retrieved from https://yihui.org/knitr/ [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y (2019). TinyTeX: A lightweight, cross-platform, and easy-to-maintain LaTeX distribution based on TeX live. TUGboat, (1), 30–32. Retrieved from http://tug.org/TUGboat/Contents/contents40-1.html [Google Scholar]

- Yoshino S, & Oshio A (2022). Personality and migration in Japan: Examining the tendency of extroverted and open people to migrate to Tokyo. Journal of Research in Personality, 96, 104168. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.