Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The efficacy of intravenous (IV) vedolizumab vs subcutaneous (SC) adalimumab for the treatment of moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis (UC) was assessed in the VARSITY clinical trial, which demonstrated for the first time in a head-to-head clinical trial setting the superiority of IV vedolizumab with respect to clinical remission and endoscopic improvement. Both therapies offer better clinical outcomes compared with immunomodulators and corticosteroids but are often more expensive than other pharmacologic treatment options. Thus, payers and decision makers face the task of leveraging finite resources for optimal health benefits, which can be aided by the use of cost-effectiveness models.

OBJECTIVE:

To assess the cost-effectiveness of IV vedolizumab vs SC adalimumab from a US payer perspective using head-to-head data from the VARSITY trial.

METHODS:

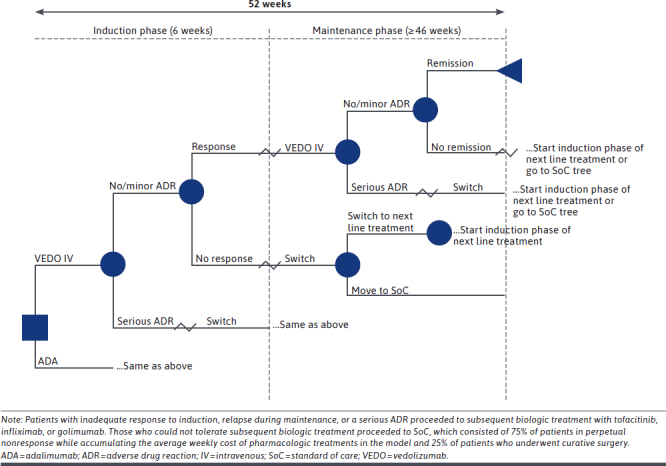

A cohort decision tree was developed to estimate the costs and clinical outcomes associated with IV vedolizumab vs SC adalimumab to treat adults with moderately to severely active UC. Simulated cohorts began the model at treatment induction and continued to maintenance treatment with vedolizumab or adalimumab unless experiencing nonresponse or serious adverse drug reaction (ADR), in which case those patients transitioned to second-line treatment with tofacitinib, infliximab, or golimumab, where they could achieve response and/or remission or not. Those who still did not achieve response or remission or who had a serious ADR transitioned to a state of nonresponse for the remainder of the model or received surgery. The process was modeled for patients who were treatment naive and treatment experienced at baseline separately. Efficacy and safety inputs for vedolizumab and adalimumab were taken from the VARSITY trial, and corresponding inputs for other biologics were derived from a network meta-analysis. All clinical inputs were extrapolated over 2 years. Direct medical costs (expressed in 2019 US dollars) included those related to drug acquisition and administration, ADRs, routine monitoring, and additional treatment procedures. Outcomes were not discounted given the short time horizon. Univariate sensitivity and scenario analysis were applied to evaluate the robustness of the model to underlying parameter and structural uncertainty.

RESULTS:

Initial treatment with vedolizumab was associated with a higher remission rate at 2 years (73.5% vs 71.5%) and higher persistence (22.0% vs 14.4%) compared with adalimumab. Total direct medical costs were lower for the vedolizumab cohort ($100,022 vs $151,133), primarily driven by the lower annual drug acquisition cost of vedolizumab ($85,953 vs $137,492). When endoscopic improvement was used as the outcome measure, IV vedolizumab was also associated with higher endoscopic remission and lower overall costs.

CONCLUSIONS:

With better clinical outcomes and lower direct medical costs over a 2-year model horizon, vedolizumab IV was the dominant treatment strategy vs adalimumab SC in adults with moderately to severely active UC. Outcomes were driven primarily by the probability of major ADRs and induction response.

What is already known about this subject

Biologic treatments for ulcerative colitis (UC) are associated with high drug costs but confer better clinical outcomes compared with immunomodulator therapy.

Vedolizumab was associated with better clinical outcomes for patients with moderately to severely active UC vs adalimumab in the VARSITY head-to-head trial.

The cost-effectiveness of vedolizumab vs adalimumab in UC has been demonstrated in the United Kingdom, Japan, and China, but no such analysis has recently been conducted in the United States.

What this study adds

Vedolizumab was associated with better clinical outcomes and lower direct medical costs over a 2-year horizon compared with adalimumab for the treatment of moderately to severely active UC.

The economic benefits of vedolizumab were driven primarily by lower drug costs for patients initiated on vedolizumab therapy.

This is the first study from a US payer perspective to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of vedolizumab vs adalimumab in UC based on head-to-head data from the VARSITY trial.

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a form of inflammatory bowel disease characterized by chronic relapsing-remitting inflammation of the colon.1 The prevalence of UC in the United States is 286 cases per 100,000 in the general population.2 In 2016, the lifetime US direct medical cost for patients with UC was estimated to be $377 billion.3 Other US-based estimates have found that the annual direct and indirect costs associated with UC are between $8.1 billion and $14.9 billion.4

The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) and American College of Gastroenterology have recommended immunomodulators and biologic therapies for long-term management of moderately to severely active UC. This includes antitumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α therapies (eg, infliximab and adalimumab), anti-integrin therapy (vedolizumab), anti-interleukin-12/23 therapy (ustekinumab), and Janus kinase inhibitor therapy (tofacitinib).1,5 Biologic UC treatments traditionally have high drug acquisition costs yet provide comparatively better clinical outcomes compared with immunomodulators.6,7 Therefore, to guide resource allocation toward cost-effective UC treatments, payers and other stakeholders must weigh the costs and clinical benefits of the available advanced treatment options.7-10 Vedolizumab has been found to be more cost-effective compared with immunosuppressive therapy in patients with moderately to severely active UC in the United States, United Kingdom, Japan, and China for anti-TNF-naive and anti-TNF-experienced patients.11-15

Cost-effectiveness analysis is useful for guiding optimal allocation of finite resources,9,10 and it can be more flexible than other analyses because it allows for varying clinical and economic inputs to investigate alternative scenarios and assess the effect of uncertainty on modeled outcomes. However, many cost-effectiveness analyses are limited by a lack of head-to-head clinical trial evidence for the treatment strategies being assessed.

This analysis assessed the cost-effectiveness of intravenous (IV) vedolizumab vs subcutaneous (SC) adalimumab from a commercial payer perspective in the United States and integrated the comparative efficacy inputs from the phase 3 VARSITY trial, the first head-to-head trial comparing 2 biologic therapies (vedolizumab IV and adalimumab SC) in adults with moderately to severely active UC.16

Methods

POPULATION

The modeled patient population consisted of adult patients with moderately to severely active UC (Mayo score 6-12 and endoscopic subscore ≥ 2) who had inadequate response, loss of response, or intolerance to 1 or more corticosteroid, immunosuppressive, and/or anti-TNF agent. Because previous treatment with an anti-TNF therapy can affect subsequent clinical outcomes, the model evaluated clinical outcomes separately for anti-TNF-experienced and anti-TNF-naive subgroups and then aggregated them for the overall population results. Base-case percentages of anti-TNF-naive and anti-TNF-experienced patients were 79% and 21%, respectively, consistent with the percentages in the VARSITY trial. The relative distribution of these subgroups was based on the distribution reported in the VARSITY clinical trial.17 Alternative scenarios assessed outcomes for anti-TNF-naive and anti-TNF-experienced populations independently.

MODEL DESIGN

A 2-year cohort decision tree model (adapted from a similar previous analysis18) was developed to compare vedolizumab IV and adalimumab SC. The model estimated direct medical costs (eg, drug costs, downstream treatment costs, standard of care treatment costs, routine monitoring costs, drug administration costs, and costs associated with adverse drug reactions [ADRs]) over the 52-week trial period and extrapolated the clinical outcomes for an additional 52 weeks (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Drug Acquisition Costsa

| Treatment | Cost per week, 2019 USD | |

|---|---|---|

| Main comparators | ||

| Vedolizumab IV (induction)b | $3,234 | |

| Vedolizumab IV (maintenance)b | $809 | |

| Adalimumab SC (induction)c | $2,587 | |

| Adalimumab SC (maintenance)c | $1,293 | |

| Downstream treatments | ||

| Tofacitinib | $1,034 | |

| Infliximab | $1,167 | |

| Golimumab | $1,499 | |

| Standard of care | ||

| Oral steroids | $25 | |

| Intensive IV steroids | $86 | |

| Immunosuppressive agents: IV cyclosporine | $2,366 | |

| Health care resource utilizationd | Unit frequency | Unit cost, 2019 USD |

| Routine monitoringe | ||

| Outpatient visit for new patient | 1 | $300.09 |

| Outpatient visit for established patient | 13 | $195.71 |

| Endoscopy | 1 | $1,287.17 |

| Lab test: complete blood count | 4 | $10.66 |

| Lab test: liver function test | 4 | $11.21 |

| Lab test: lipid panel | 4 | $17.86 |

| Lab test: antidrug antibody | 4 | $38.16 |

| Drug administration | ||

| Dispensing fee | Per month | $5.42 |

| Vedolizumab IV drug administration | Per infusion | $186.40 |

| ADR | ||

| Major ADR | 1 | $21,896 |

| Minor ADR | 1 | $1,329 |

| Curative surgery (colectomy, average of DRG 329, 330, 331) | 1 | $18,196 |

aResource utilization and costs for drug acquisition, drug administration, inpatient and outpatient visits, and ADR management were derived from publicly available reference sources: the Micromedex database for drug cost information and product labels for dosing and administration information.19 Given the differences in dosing and administration frequency, we applied drug costs on a weekly basis as determined by the annual cost per course divided by 52 weeks.

bVedolizumab 300 mg IV on day 1 and weeks 2 and 6 (induction) and every 8 weeks thereafter (maintenance).

cAdalimumab 160 mg SC on day 1, adalimumab 80 mg SC at week 2, adalimumab 40 mg SC at weeks 4 and 6 (induction), then adalimumab 40 mg SC every 2 weeks thereafter (maintenance).

dCosts of ADRs and other direct medical costs were based on CPT and DRG codes.

eAll patients received initial or subsequent treatment for the entire model horizon; thus, costs of routine monitoring are equal for both treatment arms.

ADR = adverse drug reaction; CPT = Current Procedural Terminology; DRG = diagnosis-related group; IV = intravenous; SC = subcutaneous; USD = US dollars.

Patients started induction treatment on vedolizumab IV or adalimumab SC and proceeded to maintenance therapy on the same drug if they achieved a response or remission during induction and did not have an ADR. Patients who did not achieve response and/or remission or who experienced an ADR during induction switched to induction with another therapy (tofacitinib, infliximab, or golimumab) or to treatment with chronic immunosuppressants if the other advanced therapies were contraindicated. Patients could achieve response and remission on these downstream therapies. In this model, patients who continued to not respond or achieve remission either remained in a state of nonresponse or underwent curative surgery.

Costs and clinical outcomes were not discounted because of the short time horizon of the model. Each branch of the decision-tree model was weighted by event probabilities and the direct costs associated with each treatment or outcome (Figure 1). The analysis was conducted from a US commercial payer perspective. Costs are expressed in 2019 US dollars. Where required, costs were inflated to the year 2019 using the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index for all urban consumers. The model was developed in Microsoft Excel.

FIGURE 1.

Decision-Tree Model

INTERVENTIONS

The vedolizumab IV cohort received induction therapy of 300 mg at weeks 0, 2, and 6. Those who responded to vedolizumab IV induction began maintenance therapy of 300 mg every 8 weeks. The adalimumab SC cohort received induction therapy of 160 mg on day 1 and 80 mg on day 15. Those who responded to adalimumab SC began maintenance therapy of 40 mg every 2 weeks. Patients could continue maintenance therapy for the remainder of the model. Treatments given after the initial therapy failed were dosed according to the approved label for each respective product. Wholesale acquisition costs (WACs) were collected from IBM Micromedex RED BOOK.19

KEY MODEL ASSUMPTIONS

Patients with inadequate response to induction therapy were switched to a second-line treatment option (tofacitinib, infliximab, or golimumab) until lack of treatment response or until a serious ADR occurred. Patients who did not achieve response or remission on second-line treatment proceeded to a state of perpetual nonresponse for the remainder of the model, while accruing the average weekly cost of pharmacotherapies in the model, except for some patients (25% in the base case) who underwent curative surgery.

MODEL INPUTS

Efficacy data were derived from a recent network metaanalysis (Table 2).17 Response to induction therapy was defined as a decrease from baseline in total Mayo score of 3 or more points and at least 30%, with an accompanying decrease in the rectal bleeding subscore of 1 or more or absolute rectal bleeding subscore 1 or less. Remission following maintenance therapy was defined as a total Mayo score of 2 or less, with no subscore greater than 1 and a rectal bleeding subscore of 0. Endoscopic improvement was defined as a Mayo endoscopic subscore of 1 or less.

TABLE 2.

Treatment Effectiveness Inputs

| Treatment groups | Induction response at 6 weeks | Remission at 52 weeks | ADRs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Anti-TNF naive | Anti-TNF experienced | Overall | Anti-TNF naive | Anti-TNF experienced | Major | Minor | |

| Initial, % | ||||||||

| Vedolizumab IVa | 56.9 | 60.3 | 35.4 | 44.6 | 45.9 | 44.5 | 1.4 | 39.2 |

| Adalimumab SCb | 47.1 | 51.7 | 21.1 | 33.3 | 35.1 | 30.5 | 1.6 | 44.9 |

| Downstream, % | ||||||||

| Tofacitinib | 59.3 | 54.0 | 64.4 | 54.8 | 59.7 | 31.2 | 0.8 | 56.8 |

| Infliximab | 69.5 | 71.5 | 64.4 | 34.8 | 39.5 | 31.2 | 3.1 | 43.7 |

| Golimumab | 55.6 | 58.1 | 64.4 | 33.4 | 37.7 | 31.2 | 3.3 | 54.3 |

| Oral steroids | NA | NA | NA | 65.0 | 65.0 | 65.0 | NA | NA |

aVedolizumab 300 mg IV on day 1 and weeks 2 and 6 (induction) and every 8 weeks thereafter (maintenance).

bAdalimumab 160 mg SC on day 1, adalimumab 80 mg SC at week 2, adalimumab 40 mg SC at weeks 4 and 6 (induction), then adalimumab 40 mg SC every 2 weeks thereafter (maintenance).

ADR = adverse drug reaction; IV = intravenous; NA = not applicable; SC = subcutaneous; TNF = tumor necrosis factor.

The health care resource utilization (HCRU) components examined included outpatient visits, inpatient stays, emergency department visits, endoscopy, laboratory tests, drug administration by infusion, and treatment for ADRs and were estimated using data from a targeted literature search (Table 1). ADRs were defined broadly according to definitions used in previously published economic models in UC.18,20 A major ADR was defined as a serious infection requiring a visit to the emergency department or hospital admission for inpatient care. Upper respiratory tract infection was chosen to represent minor ADRs, consistent with previously published economic models.18,20

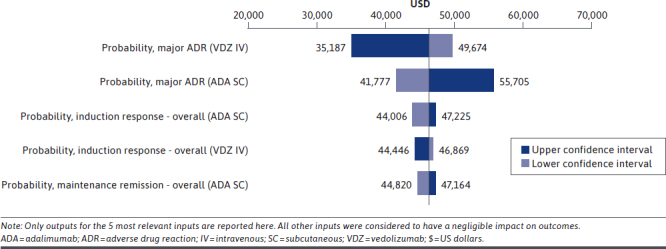

SENSITIVITY ANALYSIS

The model included 1-way univariate sensitivity analyses in which relevant inputs of the model were varied, one at a time, from the mean to low and to high values. The outcomes of the sensitivity analyses at 2 years were compared with the base model, and inputs were ranked by their relative impact according to the magnitude of the difference in the incremental net monetary benefit. The magnitude of each impact was defined as the absolute value of the difference in incremental net monetary benefit when using the low value vs the high value. Herein, we report the 5 most influential inputs.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Efficacy data were derived from a network meta-analysis of published clinical trials.17 All trials received approval by the Institutional Review Board, and all patients in these trials provided written informed consent. No additional consent or approval was considered necessary for the present study.

Results

OVERALL STUDY POPULATION

A similar percentage of patients who initially started with vedolizumab IV and adalimumab SC achieved remission at 2 years (73.5% vs 71.5%, respectively). Of these, a higher percentage of patients who initially started on vedolizumab remained in remission on vedolizumab rather than with downstream treatments at the end of year 2 (22.0%) compared with 14.4% of patients who initiated on adalimumab.

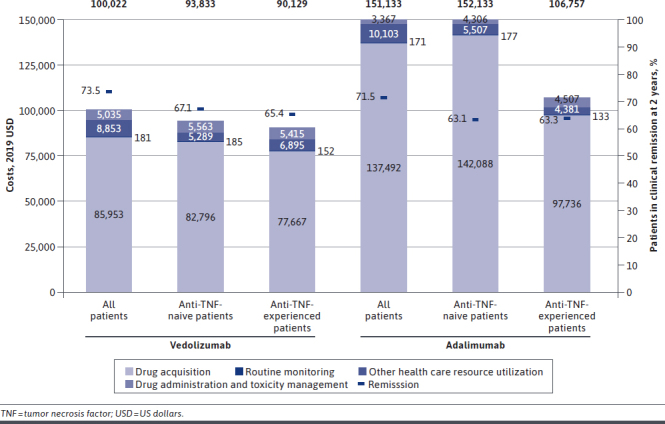

Total direct medical costs over 2 years in the vedolizumab arm were $100,022 per patient compared with $151,133 in the adalimumab arm (Figure 2). The difference was driven by the lower drug acquisition cost of vedolizumab ($85,953 vs $137,492 for adalimumab). Drug administration costs were higher with vedolizumab than with adalimumab ($5,035 vs $3,367), reflecting the IV vs SC mode of administration.

FIGURE 2.

Costs Per Patient Over 2 Years

Administration costs for the adalimumab cohort were primarily from downstream IV-infused treatments. Routine monitoring costs were similar ($181 for both cohorts). Direct costs associated with other HCRU were lower with vedolizumab than with adalimumab ($7,917 vs $8,690) because of the higher failure rates of adalimumab. Vedolizumab was also associated with greater endoscopic improvement than adalimumab (10.83% vs 5.77%, respectively).

ANTI-TNF-NAIVE PATIENTS

A similar percentage of anti-TNF-naive patients initially treated with vedolizumab or adalimumab achieved remission at 2 years (67.1% vs 63.1%, respectively; Figure 2). However, total costs over 2 years in the vedolizumab arm were estimated to be $93,833 per patient compared with $152,078 per patient in the adalimumab arm. The difference was driven primarily by the lower drug acquisition cost of vedolizumab ($82,796 vs $142,088 for adalimumab).

ANTI-TNF-EXPERIENCED PATIENTS

A similar percentage of anti-TNF-experienced patients initially treated with vedolizumab or adalimumab achieved remission at 2 years (65.4% vs 63.3%), but total costs over 2 years per patient in the vedolizumab arm were estimated to be $90,129 compared with $106,757 in the adalimumab arm (Figure 2).

SENSITIVITY ANALYSIS

Results of the 1-way univariate sensitivity analysis of the base case at 2 years indicated that the most influential variables were the probability of major ADRs during the induction phase associated with vedolizumab IV or adalimumab SC (Figure 3). The next most influential variables were probabilities of induction response overall with adalimumab and with vedolizumab IV and of maintenance remission overall with adalimumab SC.

FIGURE 3.

One-Way Univariate Sensitivity Analysis Outcomes After 2 Years Expressed as Difference in Total Costs

Discussion

This cohort decision-tree model incorporated data from a head-to-head study of vedolizumab and adalimumab in patients with UC and thus may provide more reliable outputs than models using indirect comparisons. The model demonstrated that vedolizumab IV dominates adalimumab SC by providing greater clinical efficacy, as well as lower overall costs in adults with moderately to severely active UC. Costs were lower with vedolizumab IV for both anti-TNF-naive and anti-TNF-experienced patients. The difference between treatment groups was driven by drug costs, offsetting the higher administration costs associated with IV vs SC delivery. Treatment decisions should be centered on the patient’s goals and made within a cross-functional health care team. When multiple treatment options are appropriate, choosing the most cost-effective treatment can help address rising health care costs in the United States.

According to this model, the difference in the proportions of patients who achieved remission while remaining on their initial treatments over a 2-year period was consistent with the 8.8% difference observed in the head-to-head VARSITY trial over 52 weeks.16 Difficulties in comparing cross-trial remission rates between vedolizumab and adalimumab have been highlighted previously,16 but the network meta-analysis evidence used herein to account for the impact of subsequent therapies on patients who did not initially achieve remission with vedolizumab or adalimumab is consistent with the head-to-head clinical trial data.

We evaluated the model by comparing it to the results of other similar publicly available research. Pharmacoeconomic outcomes were consistent with other studies investigating the cost-effectiveness of vedolizumab vs adalimumab.12-15,21 An earlier US study indicated that cost per endoscopic improvement event was approximately 5% lower with vedolizumab than with adalimumab, with drug cost being the main cost driver over a 1-year time horizon.12 Here, vedolizumab was associated with greater endoscopic improvement and lower overall costs, which is consistent with a lower cost per endoscopic improvement.

In Japan, vedolizumab was associated with higher drug-related costs over the lifetime of an anti-TNF-naive patient than was adalimumab (incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of ¥4,821,940), but vedolizumab was cost-effective due to the greater amount of time spent on treatment, in response and remission, and because fewer surgeries were required compared with adalimumab.13 Likewise, vedolizumab was cost-effective in the United Kingdom vs adalimumab (£22,735 per quality-adjusted life-year [QALY] gained), having been associated with more QALYs and longer time spent in response and remission states.12,14,21 Jansen et al reported that costs per patient in sustained remission in anti-TNF-naive and anti-TNF-experienced patients were £95,833 and £116,100, respectively, for vedolizumab and £148,087 and £217,457 for adalimumab.14 Vedolizumab also was dominant over the anti-TNFs infliximab and golimumab in these UK analyses.2,14,21 Similar outcomes were also seen in anti-TNF-naive and anti-TNF-experienced patients.11

In contrast, a Spanish cost-effectiveness study by Trigo-Vicente et al reported that over a 10-year period adalimumab was cost-effective compared with vedolizumab and other anti-TNFs.22 These results were due to a relative cost per vedolizumab dose that was approximately 7 times higher than that of adalimumab,22 whereas in the our US analysis, weekly costs were closer for induction treatment with these 2 drugs and less expensive for maintenance treatment with vedolizumab.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

The inclusion of clinical inputs from the VARSITY head-to-head trial is an important strength of this research. The VARSITY trial allowed for stronger clinical and safety comparisons. Adaptation from the Milev model is a strength of this research because it allows for further validation of previous conceptual models with the inclusion of stronger comparative research.18 The use of published drug prices may be considered a strength due to transparency and consistency of reporting across. Individual payers may consider how their specific rebates/discounts affect the conclusions.

Data on loss of efficacy and discontinuation over time are incomplete; however, it is not expected that differences between treatments would have been sufficiently large to substantially affect these results. Likewise, costs relating to minor ADRs were limited to upper respiratory tract infections as a representative minor ADR. While common, and used as a representative minor ADR in other pharmacoeconomic models of UC,18,20 upper respiratory tract infections (and their associated cost) are not necessarily representative of all minor ADRs associated with vedolizumab or adalimumab SC treatment. However, the safety profile of treatments is dependent on their mechanism of action, making comparisons of safety outcomes beyond common ADRs difficult.

Only the costs for branded products that were compared in the head-to-head VARSITY study were used in our analysis instead of the full constellation of treatments used in patients with UC, for which there are currently no head-to-head comparisons. Likewise, subsequent treatments were restricted to those selected by Milev et al to facilitate a contemporary comparison of this updated model, which incorporated new data.18 Outcomes from the randomized controlled trial used as inputs in this analysis may also not be fully reflective of the costs incurred and outcomes observed in a real-world setting.

Using only branded biologics for costs may limit the generalizability, given that biosimilars are commonly used. Furthermore, WACs used to estimate drug acquisition costs do not reflect the real-world discounts and rebates that result in a net price of the medications so are not reflected in the cost-effectiveness results. WAC is a transparent and publicly available price, which avoids having to make an assumption about a single discount rate that is applied broadly. This transparency and consistency will allow any reader to modify the outcomes reported here based on their own private discounts. Discounts or rebates that significantly lower the cost of adalimumab in comparison with vedolizumab could result in vedolizumab no longer being dominant.

It should also be noted that the AGA guidelines make a conditional recommendation with a low level of evidence to use ustekinumab or tofacitinib instead of adalimumab or vedolizumab, for inducing remission in patients with UC previously treated with infliximab, particularly in those with primary nonresponse.5

Conclusions

This US-based, commercial payercentric economic model demonstrated that vedolizumab treatment was associated with greater clinical efficacy and lower total costs over a 2-year period in adults with moderately to severely active UC in comparison with adalimumab. Thus, initiating treatment with vedolizumab rather than with adalimumab may provide a clinical benefit to patients, while also providing cost savings for health care organizations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Medical writing assistance was provided by Blair Hesp, PhD, CMPP, and Jennie G. Jacobson, PhD, CMPP, from Syneos Health Medical Communications, LLC, and supported by Takeda Pharmaceuticals U.S.A., Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rubin DT, Ananthakrishnan AN, Siegel CA, Sauer BG, Long MD. ACG clinical guideline: Ulcerative colitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(3):384-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ng SC, Shi HY, Hamidi N, et al. . Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet. 2017;390(10114):2769-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lichtenstein GR, Shahabi A, Seabury SA, et al. . Lifetime economic burden of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis by age at diagnosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(4):889-97.e810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Du L, Ha C. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 2020;49(4):643-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feuerstein JD, Isaacs KL, Schneider Y, et al. ; AGA Insitute Clinical Guidelines Committee. AGA clinical practice guidelines on the management of moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(5):1450-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pillai N, Dusheiko M, Burnand B, Pittet V. A systematic review of cost-effectiveness studies comparing conventional, biological and surgical interventions for inflammatory bowel disease. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0185500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park KT, Ehrlich OG, Allen JI, et al. . The cost of inflammatory bowel disease: an initiative from the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26(1):1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rubin DT, Mody R, Davis KL, Wang CC. Real-world assessment of therapy changes, suboptimal treatment and associated costs in patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39(10):1143-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill SR. Cost-effectiveness analysis for clinicians. BMC Med. 2012;10:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanders GD, Maciejewski ML, Basu A. Overview of cost-effectiveness analysis. JAMA. 2019;321(14):1400-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson MR, Azzabi Zouraq I, Chevrou-Severac H, Selby R, Kerrigan MC. Cost-effectiveness of vedolizumab compared with conventional therapy for ulcerative colitis patients in the UK. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2017;9:641-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu B, Wang Z, Zhang Q. Cost-effectiveness of different strategies for the treatment of moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24(11):2291-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hernandez L, Kuwabara H, Shah A, et al. . Cost-effectiveness analysis of vedolizumab compared with other biologics in anti-TNF-naïve patients with moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis in Japan. Pharmacoeconomics. 2020;38(1):69-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jansen J, Mody R, Ursan I, Lorenzi M, Patel H, Alberton M. Cost per clinical outcomes with biologics for the treatment of moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2015;9(Suppl 1): S239-S240. Abstract P322. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yokomizo L, Limketkai B, Park KT. Cost-effectiveness of adalimumab, infliximab or vedolizumab as first-line biological therapy in moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2016;3(1):e000093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sands BE, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Loftus EV, Jr, et al. . Vedolizumab versus adalimumab for moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(13):1215-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jairath V, Chan K, Lasch K, et al. . P038 Comparing the efficacy and safety of subcutaneous vedolizumab versus adalimumab for the treatment of ulcerative colitis: a network meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:S10. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milev S, DiBonaventura MD, Quon P, et al. . An economic evaluation of tofacitinib for the treatment of moderately-to-severely active ulcerative colitis: modeling the cost of treatment strategies in the United States. J Med Econ. 2019;22(9):859-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.IBM Watson Health. IBM Micromedex RED BOOK. Database. Accessed November 11, 2020. https://www.ibm.com/watson/health/provider-client-training/micromedex-red-book/

- 20.Buckland A, Bodger K. The cost-utility of high dose oral mesalazine for moderately active ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28(11-12):1287-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson MR, Bergman A, Chevrou-Severac H, Selby R, Smyth M, Kerrigan MC. Cost-effectiveness of vedolizumab compared with infliximab, adalimumab, and golimumab in patients with ulcerative colitis in the United Kingdom. Eur J Health Econ. 2018;19(2):229-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trigo-Vicente C, Gimeno-Ballester V, Montoiro-Allué R, López-Del Val A. Cost-effectiveness analysis of infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab and vedolizumab for moderate to severe ulcerative colitis in Spain. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2018;18(3):321-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]