Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Prescriber requirements are a form of utilization management (UM) in which health plans require that a certain type of physician (eg, a rheumatologist) prescribe a drug.

OBJECTIVE:

To examine how a set of US commercial health plans impose prescriber requirements in their specialty drug coverage decisions.

METHODS:

We identified specialty drug coverage decisions from the Tufts Medical Center Specialty Drug Evidence and Coverage (SPEC) Database. SPEC includes coverage information issued by 17 large US commercial health plans. We categorized prescriber requirements as the following: (1) the drug must be prescribed in consultation, supervision, or coordination with a specialist; (2) the drug must be prescribed by a specialist (eg, a neurologist); or (3) the drug must be prescribed by a specialist with particular expertise (eg, a neurologist with expertise in spinal muscular atrophy). First, we examined how often each plan imposed prescriber requirements. Second, we determined the degree of specialization that plans required prescribing physicians to have. Third, we used Pearson’s chi-square tests to examine the association between plans’ use of prescriber requirements and the following drug characteristics: cancer treatment, orphan indication, pediatric indication, drug approved in the last year, black box warning, and self-administered formulation.

RESULTS:

Overall, health plans imposed prescriber requirements in 22.0% (1,844/8,383) of their coverage decisions, although the frequency that they did so varied (range: 0.8%-86.0%). Of prescriber requirements, 79.1% (1,459/1,844) required that the drug be prescribed in consultation, supervision, or coordination with a specialist; 18.3% (338/1,844) required that the drug be prescribed by a specialist; and 2.6% (47/1,844) required that the drug be prescribed by a specialist with particular expertise. Plans were more likely to impose prescriber requirements for drugs with the following characteristics: indicated for a pediatric population, black box warning, self-administered, and noncancer treatments (all P < 0.001).

CONCLUSIONS:

Health plans varied in the frequency that they imposed prescriber requirements in their specialty drug coverage decisions and with respect to the degree of specialization they required prescribing physicians to have.

What is already known about this subject

Health plans impose utilization management (UM) tools to manage their enrollees’ access to prescription drugs.

While UM can reduce overprescribing and contain costs, there is a risk that inappropriately imposed UM will hinder patient access to much needed treatments.

What this study adds

This study examines use of prescriber requirements by US commercial health plans in their specialty drug coverage decisions.

The included US commercial health plans imposed prescriber requirements in roughly 20% of their specialty drug coverage decisions.

Health plans vary in the frequency that they impose prescriber requirements and with respect to the degree of specialization they require prescribing physicians to have.

Health plans impose utilization management (UM) tools to manage their enrollees’ access to prescription drugs. Plans impose UM with the intention of optimizing patient outcomes and reducing error, unnecessary drug use, and costs.1,2 However, there is a risk that inappropriately imposed UM will hinder patient access to much needed treatments.3,4 UM can take a variety of forms, including patient subgroup restrictions (requirements for patients to meet certain clinical criteria, eg, symptoms of particular severity or duration); step therapy protocols (requirements for patients to first fail alternative therapies); approval period/quantity limits; and site of care restrictions.5

In this study, we evaluated another UM tool: prescriber requirements. Health plans impose prescriber requirements to ensure that a physician with sufficient expertise prescribes a product. This requirement may be necessary for complex treatments, from which patients may not benefit, or even experience harm, if the drug is prescribed inappropriately. However, there is a danger that a plan’s overuse of prescriber requirements may create unnecessary patient access hurdles.

Various studies have evaluated health plans’ use of UM tools. Studies have found that physicians spend substantial time and resources fulfilling UM requirements.4,6 Studies have also found that, while UM tools such as prior authorization and step therapy protocols typically reduce drug utilization, in some cases they can adversely impact patient adherence to care and clinical outcomes.7 However, health plans’ use of prescriber requirements in their drug coverage policies is not well understood.

In this study, we examined how a set of US commercial health plans imposed prescriber requirements in their specialty drug coverage policies. First, we examined the frequency that plans imposed prescriber requirements. Second, we assessed the degree of specialization that plans required prescribing physicians to have. Third, we determined the frequency that plans imposed prescriber requirements for different drug categories, eg, orphan vs nonorphan drugs.

Methods

DATA SOURCE

The starting point for this research was the Tufts Medical Center Specialty Drug Evidence and Coverage (SPEC) Database, which includes publicly available coverage information issued by 17 large US health plans for their commercial lines of business. SPEC includes 11 regional and 6 national commercial health plans, which collectively represent roughly 150 million commercially covered lives, or roughly 60% of the commercial health insurance market. The included plans are listed in Supplementary Table 1 (71.4KB, pdf) (available in online article).

SPEC includes 311 specialty drugs. Because the US Food and Drug Administration may approve a drug for multiple indications, the database includes each drug indication separately. For example, because omalizumab is indicated for moderate to severe persistent asthma and for urticaria, it features twice in SPEC. SPEC includes 647 drug-indication pairs, corresponding to 8,383 coverage decisions that were in force as of December 2020. Detailed information on the SPEC Database can be found elsewhere.8,9

SPEC contains information on how plans cover specialty drugs, including information on plan-imposed prescriber requirements. For this study, we reviewed each prescriber requirement and categorized it as the following: (1) the drug must be prescribed in consultation, supervision, or coordination with a specialist; (2) the drug must be prescribed by a specialist (eg, a neurologist); or (3) the drug must be prescribed by a specialist with particular expertise (eg, a neurologist with an expertise in Duchenne muscular dystrophy).

ANALYSIS

We reported the relative frequency that health plans imposed prescriber requirements and other UM tools, including patient subgroup restrictions and step therapy protocols. We analyzed health plans’ use of prescriber requirements in 3 ways. First, we examined how often each plan imposed prescriber requirements. Second, we determined the degree of specialization that plans required prescribing physicians to have. Third, we used Pearson’s chi-square tests to examine the association between plans’ use of prescriber requirements and the following drug characteristics: cancer treatment, orphan indication, pediatric indication, drug approved in the last year, black box warning, and self-administered formulation. We performed analyses using Stata SE, version 16.1 (StataCorp).10 Because no patient data were used for this analysis, we obtained an institutional review board waiver for this study.

Results

Overall, health plans imposed prescriber requirements in 22.0% (1,844/8,383) of coverage decisions, which was less often than plans imposed step therapy protocols (29.3%; 2,453/8,383), but more often than plans imposed patient subgroup restrictions (15.8%; 1,327/8,383). In 12.8% (1,073/8,383) of decisions, plans imposed patient subgroup restrictions and/or step therapy protocols in the same decisions as they imposed prescriber requirements; in 9.2% (771/8,383) of decisions, plans did not impose patient subgroup restrictions or step therapy protocols in the same decisions as they imposed prescriber requirements.

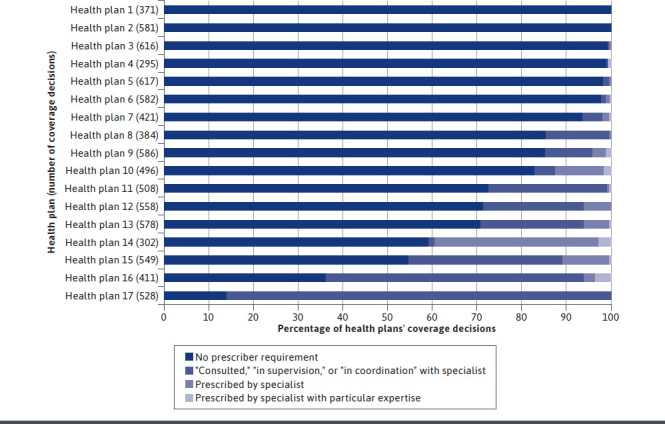

Fifteen of 17 health plans imposed prescriber requirements in a proportion of their coverage decisions, although the frequency that they did so varied widely (range: 0.8%-86.0%; Figure 1). Two plans imposed prescriber requirements in more than half of their coverage decisions; 7 plans did so in more than one-quarter of their coverage decisions. Two plans did not impose prescriber requirements in any of their coverage decisions. Of prescriber requirements, 79.1% (1,459/1,844) required that the drug be prescribed in consultation, supervision, or coordination with a specialist; 18.3% (338/1,844) required that the drug be prescribed by a specialist; and 2.6% (47/1,844) required that the drug be prescribed by a specialist with particular expertise (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Health Plan Use of Prescriber Requirements

The 5 indications for which plans most often imposed prescriber requirements were postpartum depression (84.6% of coverage decisions), spinal muscular atrophy (75.6%), thyroid eye disease (71.4%), treatment-resistant depression (66.7%), and hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis (65.6%; Supplementary Table 2 (71.4KB, pdf) , available in online article). Plans were more likely to impose prescriber requirements on drugs with the following characteristics: indicated for a pediatric population, black box warning, self-administered, and noncancer treatments (P < 0.001; Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Drug Indications and Attributes Tested for Association with Prescriber Requirements

| Prescriber requirement, % | No prescriber requirement | Any prescriber requirement | Total | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Consulted,” “in supervision,” or “in coordination” with specialist | Prescribed by specialist | Prescribed by specialist with particular expertise | ||||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||||

| Pediatric indication | Yes | 26.8 | 997 (73.2) | 271 (19.9) | 77 (5.7) | 17 (1.3) | 1,362 | < 0.001 |

| No | 21.1 | 5,542 (78.9) | 1,188 (16.9) | 261 (3.7) | 30 (0.4) | 7,021 | ||

| Recent approvala | Yes | 22.7 | 306 (77.3) | 75 (18.9) | 15 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 396 | 0.719 |

| No | 22.0 | 6,233 (78.0) | 1,384 (17.3) | 323 (4.0) | 47 (0.6) | 7,987 | ||

| Black box warning | Yes | 23.6 | 2,880 (76.4) | 687 (18.2) | 176 (4.7) | 27 (0.7) | 3,770 | < 0.001 |

| No | 20.7 | 3,659 (79.3) | 772 (16.7) | 162 (3.5) | 20 (0.4) | 4,613 | ||

| Self-administered | Yes | 26.2 | 2,333 (73.8) | 616 (19.5) | 195 (6.2) | 16 (0.5) | 3,160 | < 0.001 |

| No | 19.5 | 4,206 (80.5) | 843 (16.1) | 143 (2.7) | 31 (0.6) | 5,223 | ||

| Orphan indication | Yes | 22.6 | 2,894 (77.4) | 678 (18.1) | 134 (3.6) | 35 (0.9) | 3,741 | 0.201 |

| No | 21.5 | 3,645 (78.5) | 781 (16.8) | 204 (4.4) | 12 (0.3) | 4,642 | ||

| Cancer indication | Yes | 15.7 | 2,867 (84.3) | 497 (14.6) | 37 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | 3,401 | < 0.001 |

| No | 26.3 | 3,672 (73.8) | 962 (19.3) | 301 (6.0) | 47 (0.9) | 4,982 | ||

aWe considered a recent approval to be a drug approved by the FDA from January 1,2020, to December 31, 2020.

FDA = US Food and Drug Administration.

Discussion

Our findings indicate that the included US commercial health plans impose prescriber requirements in roughly 20% of their coverage decisions, although the frequency that they did so varied widely. Two plans did not impose any prescriber requirements, while 2 other plans did so in more than half of their decisions. When plans imposed prescriber requirements, they also imposed other restriction types in the majority of cases. We found that the plans differed with respect to the degree of specialization that they required prescribing physicians to have.

A requirement that a specialist physician prescribe a drug may be warranted in certain circumstances. We found that plans more often imposed prescriber requirements on drugs with black box safety warnings compared with drugs without black box warnings, and on drugs indicated for pediatric populations (for whom complex dosing regimens are often required), compared with drugs indicated for adult populations. We also found that plans more often imposed prescriber requirements on self-administered than on physician-administered products, which could be due to the need for patients to be sufficiently educated before self-administering a drug.

Different forms of severe depression (postpartum, treatment-resistant, and major depressive disorder) were among the diseases for which plans most often imposed prescriber requirements. This may indicate the use of prescriber requirements by plans to ensure that particular therapies are reserved for patients with sufficiently severe forms of disease. Various rare diseases (eg, spinal muscular atrophy, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) were also among the diseases for which plans most often imposed prescriber requirements. The use of prescriber requirements by health plans in these instances may be warranted because of the complexity of these diseases and their treatments.

Health plans less often imposed prescriber requirements on oncology products than on nononcology products. This may be due to patients automatically receiving cancer treatments from an oncologist, thus, negating the need for plan-imposed prescriber requirements.

A requirement that a nonspecialist physician (eg, a primary care physician) consult a specialist when prescribing particular drugs may be reasonable in certain circumstances and would reduce the need for patients to attend appointments with specialist physicians. We found that 11 of the 15 plans that imposed prescriber requirements most often required the prescriber to consult with a specialist; 3 plans most often required the prescriber to be a specialist; and 1 plan most often required the prescriber to be a specialist with particular expertise. This variation is important, since it indicates that some plans’ use of prescriber requirements presents a more substantial hurdle to patient access to care than others.

Health plans should weigh the benefits and risks of imposing prescriber requirements in their drug coverage policies. Prescriber requirements can be an effective tool when specialized training is required to evaluate and diagnose a patient and may even help reduce the need for other UM criteria, since the health plan could rely on the specialist physician to identify patients who would benefit from the treatment.11

In its recent report, “Cornerstones of ‘Fair’ Drug Coverage,” the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review notes that there is a risk that prescriber requirements lead to unnecessary treatment delays, particularly for patients located in areas underserved by specialty physicians, and negatively impact patient health outcomes.11 The report further notes that patients tend to face higher cost sharing when attending appointments with specialist physicians, which could prove to be a substantial financial burden if they require multiple visits.

However, the impact of plan-imposed prescriber requirements of patient access to care has not been examined empirically. Future research should fill this gap in the literature and evaluate the impact of prescriber requirements on patient access to care, drug utilization, cost sharing, and patient outcomes. Future research should also compare the impact of prescriber requirements with the impact of patient subgroup restrictions and step therapy protocols on patient access to care and on patient outcomes. Research that examines the factors associated with plans’ use of prescriber requirements (eg, annual drug cost) would be valuable.

LIMITATIONS

Our study has a number of limitations. First, we did not examine the impact of plan-imposed prescriber requirements on patient access to care or on drug utilization. Second, our findings may not generalize to other commercial or public payers that impose prescriber requirements in their coverage decisions. Third, our findings may not generalize to nonspecialty products. Fourth, we relied on plans’ publicly available specialty drug coverage policies for this research, so we were unable to account for plans’ internal prescriber policies that were not publicly disclosed.

Conclusions

US commercial health plans vary with respect to their use of prescriber requirements. Some plans rarely impose prescriber requirements, while others do so in the majority of their specialty drug coverage decisions. Plans also differ with respect to the degree of specialization that they require prescribing physicians to have.

REFERENCES

- 1.2018-2019 Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy Professional Practice Committee. Prior authorization and utilization management concepts in managed care pharmacy. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2019;25(6):641-44. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2019.19069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forrester C. Benefits of prior authorizations. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2020;26(7):820-22. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2020.26.7.820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nayak RK, Pearson SD. The ethics of ‘fail first’: guidelines and practical scenarios for step therapy coverage policies. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(10):1779-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colligan L, Sinsky C, Goeders L, Schmidt-Bowman M, Tutty M. Sources of physician satisfaction and dissatisfaction and review of administrative tasks in ambulatory practice: a qualitative analysis of physician and staff interviews. October 2016. Accessed October 27, 2021. https://www.ama-assn.org/media/13506/download

- 5.Patel BN, Audet PR. A review of approaches for the management of specialty pharmaceuticals in the United States. Pharmacoeconomics. 2014;32(11):1105-14. doi: 10.1007/s40273-014-0196-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlisle RP, Flint ND, Hopkins ZH, Eliason MJ, Duffin KC, Secrest AM. Administrative burden and costs of prior authorizations in a dermatology department. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(10):1074-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park Y, Raza S, George A, Agrawal R, Ko J. The effect of formulary restrictions on patient and payer outcomes: a systematic literature review. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(8):893-901. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2017.23.8.893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chambers JD, Kim DD, Pope EF, Graff JS, Wilkinson CL, Neumann PJ. Specialty drug coverage varies across commercial health plans in the US. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(7):1041-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Center for the Evaluation of Value and Risk in Health. The Specialty Drug Evidence and Coverage (SPEC) Database. Institute for Clinical Research and Health Policy Studies, Tufts Medical Center. 2020. Accessed September 16, 2020. https://spec.tuftsmedicalcenter.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 10.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. Software. 2019. Accessed October 18, 2021. https://stata.com

- 11.Pearson SD, Lowe M, Towse A, Segal CS, Henshall C. Cornerstones of “fair” drug coverage: appropriate cost-sharing and utilization management policies for pharmaceuticals. 2020. Updated September 28, 2020. Accessed April 14, 2021. https://icer.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Cornerstones-of-Fair-Drug-Coverage-_-September-28-2020.pdf [DOI] [PubMed]