Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Nonadherence and nonpersistence to antidepressants in major depressive disorder (MDD) are common and associated with poor clinical and functional outcomes and increased health care resource utilization (HCRU) and costs. However, contemporary real-world evidence on the economic effect of antidepressant nonadherence and nonpersistence is limited.

OBJECTIVE:

To assess the effect of nonadherence and nonpersistence to antidepressants on HCRU and costs in adult patients with MDD enrolled in U.S. commercial and Medicare supplemental insurance plans.

METHODS:

This was a retrospective new-user cohort study using administrative claims data from the IBM MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplemental databases from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2018. We identified adult patients with MDD aged ≥ 18 years who initiated antidepressant therapy for a new MDD episode between January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2017. Twelve-month total all-cause HCRU and costs (2019 U.S. dollars) were characterized for patients who were adherent/nonadherent and persistent/nonpersistent to antidepressants at 6 months. Adherence was defined as having proportion of days covered (PDC) ≥ 80%, and persistence was defined as having continuous antidepressant therapy without a ≥ 30-day gap. Multivariable negative binomial regression and 2-part models adjusted for baseline characteristics were used to estimate incidence rate ratios (IRRs) for HCRU and incremental costs of nonadherence and nonpersistence, respectively.

RESULTS:

A total of 224,645 patients with MDD (commercial: n = 209,422; Medicare supplemental: n = 15,223) met all study inclusion criteria. Approximately half of patients were nonadherent (commercial: 48%; Medicare supplemental: 50%) or nonpersistent (commercial: 49%; Medicare supplemental: 52%) to antidepressants at 6 months. After controlling for baseline characteristics, nonadherent patients experienced significantly more inpatient hospitalizations (commercial, adjusted IRR [95% CI]: 1.34 [1.29 to 1.39]; Medicare supplemental: 1.19 [1.12 to 1.28]) and emergency room (ER) visits (commercial, adjusted IRR [95% CI]: 1.43 [1.40 to 1.45]; Medicare supplemental: 1.28 [1.21 to 1.36]) compared with adherent patients. Similar results were observed in nonpersistent patients. Adjusted mean differences revealed that nonadherent and nonpersistent patients accumulated significantly higher medical costs (commercial: $568 [95% CI: $354 to $764] and $491 [$284 to $703]; Medicare supplemental: $1,621 [$314 to $2,774] and $1,764 [$451 to $2,925]), inpatient costs (commercial: $650 [$490 to $801] and $564 [$417 to $716]; Medicare supplemental: $1,546 [$705 to $2,308] and $1,567 [$778 to $2,331]), and ER costs (commercial: $130 [$115 to $143] and $129 [$115 to $142]; Medicare supplemental: $82 [$23 to $150] and $80 [$18 to $150]), and incurred significantly lower pharmacy costs (commercial: −$561 [−$601 to −$521] and −$576 [−$616 to −$540]; Medicare supplemental: −$510 [−$747 to −$227] and −$596 [−$830 to −$325]) compared with adherent and persistent patients, respectively.

CONCLUSIONS:

This study found more hospitalizations and ER use and higher total medical costs among patients who were nonadherent and nonpersistent to antidepressants at 6 months. Strategies that promote better adherence and persistence may lower HCRU and medical costs in patients with MDD.

What is already known about this subject

Adherence and persistence to antidepressant therapy for major depressive disorder (MDD) are poor, with only 35%-55% of patients remaining adherent or persistent to antidepressant therapy at 6 months.

Antidepressant nonadherence and nonpersistence are associated with increased health care resource utilization (HCRU), costs, and risk of relapse and recurrence.

Contemporary real-world evidence on the effect of nonadherence and nonpersistence to antidepressants on HCRU and costs in patients with MDD is limited.

What this study adds

This study provides a comprehensive update on the contemporary economic effect of antidepressant nonadherence and nonpersistence in a broad U.S. adult MDD population enrolled in commercial and Medicare supplemental plans.

Our findings underscore the need for new strategies that promote better adherence and persistence to reduce health care burden among patients with MDD.

Major depressive disorder (MDD) affects more than 17 million Americans in the United States and is a leading cause of disability worldwide.1,2 MDD is associated with substantial clinical and economic burden; in 2010, MDD was estimated to account for $210 billion in the United States, with total costs split approximately equally between direct medical costs and indirect workplace costs (i.e., absenteeism and presenteeism costs).3

American Psychiatric Association guidelines recommend a minimum of 6-12 weeks of initial treatment with antidepressants or other treatment modalities to induce remission of symptoms (i.e., acute phase), which is followed by 4-9 months of continuous treatment to prevent relapse (i.e., continuation phase) and maintenance treatment that may be required indefinitely to prevent recurrence for patients with 3 or more major depressive episodes, chronic depression, or risk factors for recurrence.4 The National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) continues to endorse various Antidepressant Medication Management (AMM) Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measures for effective acute and continuation phase treatment with antidepressants to improve the quality of depression care.5 Although clinical guidelines emphasize the importance of adherence and persistence to antidepressants, adherence and persistence to antidepressants are suboptimal, with only 35%-55% of patients remaining adherent or persistent to antidepressant therapy at 6 months.6-10 Commonly cited reasons for nonadherence or nonpersistence to antidepressants include lack of efficacy,11 intolerability,11 regimen complexity,12 out-ofpocket costs,12,13 and patient beliefs about antidepressant medications.14,15

Both antidepressant nonadherence and nonpersistence are significant barriers to depression treatment effectiveness and subsequent remission,4 and failure to achieve adequate response or remission with antidepressant therapy is associated with poorer clinical and functional outcomes,16,17 increased health care resource utilization (HCRU) and costs,16-20 and work productivity loss.16-18 Previous research has demonstrated that antidepressant nonadherence is associated with increased risk of relapse and recurrence,21-23 more hospitalizations and emergency room (ER) visits,7,8,24 and higher health care costs.8,9,25,26 In addition, antidepressant nonpersistence, which has been assessed in previous studies as discontinuation in the first 30-180 days of antidepressant therapy, is independently associated with increased risk of relapse and recurrence10 and higher all-cause and psychiatric HCRU and costs in patients with MDD.7,9,27-29

Nevertheless, contemporary literature on the effect of antidepressant nonadherence and nonpersistence on HCRU and costs in a broad MDD population is limited. Newer antidepressants have been introduced over the past decade (i.e., vilazodone, vortioxetine, levomilnacipran), and much of the existing literature on the association between antidepressant nonadherence8,25,26 or nonpersistence25,28,29 and HCRU and costs has been published before 2010.8,25,26,28,29

Due to the high prevalence of MDD and burden associated with poor treatment outcomes in MDD, understanding the economic effect of antidepressant nonadherence and nonpersistence is of continued interest to health systems and managed care organizations. Additionally, there are inconsistent definitions and thresholds of antidepressant adherence and persistence used in the existing literature,30,31 and studies using standardized objective measures of adherence and persistence are needed.30 Furthermore, much of the previous literature has focused on privately insured commercial populations,7,8,25-29 and MDD is prevalent in other insured populations, including the Medicare population where MDD affects approximately 15% of beneficiaries aged 65 years and older.32 Therefore, the objective of this study was to provide a contemporary update on the effect of antidepressant nonadherence and nonpersistence on HCRU and costs in adult patients with MDD enrolled in commercial and Medicare supplemental insurance plans.

Methods

STUDY DESIGN AND DATA SOURCE

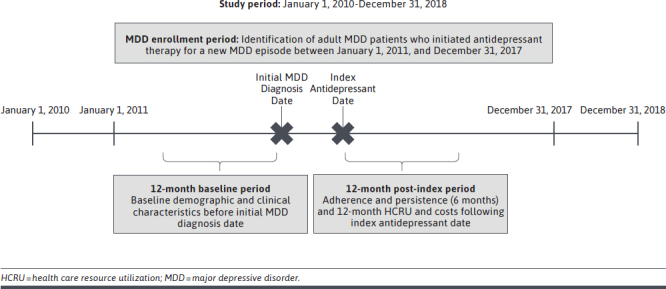

This was a retrospective new-user cohort study using administrative claims data from the IBM MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplemental databases from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2018 (Figure 1). The IBM MarketScan Commercial database consists of employer and health plan medical and pharmacy claims data for more than 40 million commercial plan members annually.33 Enrollees include employees, their spouses, and their dependents who are covered by employer-sponsored private health insurance.33 A variety of fee-for-service, fully capitated, and partially capitated health plans are represented in the IBM MarketScan Commercial database, including point-of-service, exclusive provider organizations, preferred provider organization plans, indemnity plans, health maintenance organizations, consumer-driven health plans, and high-deductible health plans.33 The IBM MarketScan Medicare Supplemental database contains data on the Medicare-covered portion of payment (i.e., coordination of benefits amount) and employer- and out-of-pocket patient expenses for health care services provided in inpatient and outpatient settings for U.S. Medicare beneficiaries.33 Medical claims are linked to outpatient prescription drug claims and person-level enrollment information.33

FIGURE 1.

Study Design

This study did not meet the definition of human subjects research and therefore did not require University of Washington Institutional Review Board approval, as the IBM MarketScan databases are deidentified and compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996.

STUDY POPULATION

Inclusion Criteria.

The study population consisted of adult patients with MDD who were identified between January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2017, and initiated an antidepressant for the treatment of a new MDD episode. Patients with MDD were defined as having either of the following: ≥ 1 inpatient medical claim with a primary International Classification of Diseases, Ninth/Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM/ICD-10-CM) diagnosis code for MDD or ≥ 1 inpatient or outpatient medical claim with a secondary ICD-9-CM or ICD-10-CM diagnosis code for MDD, followed by a second confirmatory inpatient or outpatient claim with an ICD-9-CM or ICD-10-CM diagnosis code for MDD in any position within 6 months after the initial medical claim (Supplementary Table 1, available in online article). The date of the first qualifying MDD diagnosis between January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2017, was defined as the initial MDD diagnosis date. Antidepressants for MDD included selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, and other antidepressants (Supplementary Table 2, available in online article). To ensure antidepressant claims were for the treatment of MDD, the index antidepressant date was defined as the date of the first antidepressant pharmacy claim within 60 days after a qualifying MDD diagnosis.6 Patients were required to be aged ≥ 18 years at index antidepressant date and have continuous enrollment in medical and pharmacy benefits for 12 months before the initial MDD diagnosis date (baseline period) and 12 months after the index antidepressant date (post-index period).

Exclusion Criteria.

To avoid potential bias from other neuropsychiatric conditions, patients were excluded if they had diagnoses for bipolar/manic disorder, mood disorders other than MDD, Alzheimer disease, Parkinson disease, or dementia during the study period. Additionally, patients with diagnoses of schizophrenic disorder, psychosis-related disorders, drug-induced depression, or depressive-type psychosis in the 12-month baseline period before the initial MDD diagnosis date were excluded. Patients were also excluded if they had evidence of pregnancy, childbirth, or breastfeeding at any time during the study period, as these conditions may affect antidepressant adherence and persistence. To ensure antidepressants were prescribed for a new MDD episode, additional exclusions included any MDD claims or claims for antidepressants or combination antidepressant/antipsychotic agents (i.e., amitriptyline/perphenazine, fluoxetine/olanzapine) in the 12-month baseline period and evidence of combination antidepressant therapy or augmentation therapy on or within 30 days after the index antidepressant date. Combination antidepressant therapy was defined as 1 of the following: initiating ≥2 different antidepressants on the index antidepressant date, initiating an additional antidepressant with a different active ingredient within 30 days after the index antidepressant date34 that overlaps with the index antidepressant for ≥ 30 days during the first 60 days of the index date (overlap did not need to be consecutive), or having more than 3 antidepressants within the first 30 days after the index date.34 Augmentation therapy was defined as having any claims for an antipsychotic, mood stabilizer, or combination antidepressant/antipsychotic agent on or within 30 days after the index antidepressant date (Supplementary Table 3, available in online article).34

STUDY MEASURES AND OUTCOMES

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics.

Baseline patient demographic and clinical characteristics were assessed during the 12-month baseline period before the initial MDD diagnosis date. Baseline demographic characteristics included age, sex, plan type, geographic region, and all-cause health care costs during the 12-month baseline period. Baseline clinical characteristics included the Quan-Charlson Comorbidity Index (Quan-CCI)35,36 and the following selected comorbidities of interest: anxiety, alcohol-use disorder, substance-use disorder, sleep disorders, coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure, chronic pulmonary disease, and diabetes.

Antidepressant Adherence and Persistence.

Adherence to antidepressants was estimated from pharmacy claims data using the proportion of days covered (PDC) calculation,37,38 which reflects the proportion of days covered by medication fills during a measurement period. PDC represents a more conservative measure of adherence than the formerly widely used medication possession rate, which tends to overestimate adherence and has been suggested as a preferred measure of adherence by the Pharmacy Quality Alliance and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.38-40 Adherent patients were defined as having PDC ≥ 80%. Persistence was defined as continuous therapy without the presence of a ≥ 30-day gap in therapy.6,7,41 Adherence and persistence were assessed at 6 months following the index antidepressant date,7,9,24,25,42 a time frame that consists of both the acute and continuation phases of MDD treatment. Adherence and persistence were calculated for antidepressant therapy overall; in other words, any antidepressant for MDD was used toward the calculation of adherence and persistence.

All-Cause Health Care Resource Utilization and Costs.

All-cause (regardless of diagnosis code) HCRU and costs were assessed over the 12-month post-index period following the index antidepressant date. HCRU and costs were reported by setting of care (inpatient, ER, outpatient, pharmacy). Outpatient visits were further categorized as physician office visits and other outpatient visits (i.e., outpatient visits excluding physician office and ER visits). HCRU was reported as counts and percentages of patients with ≥ 1 visit and mean visits or pharmacy claims per patient per year (PPPY). Costs were categorized as medical (sum of inpatient, ER, and outpatient costs); pharmacy; and total health care costs (sum of medical and pharmacy costs) and reported as mean costs PPPY. All costs were adjusted to 2019 U.S. dollars using the Bureau of Labor Statistics medical care component of the Consumer Price Index43 and reflected all payments made to providers by insurers (i.e., plan and coordination of benefits) and patients (i.e., copay, co-insurance, deductible). Patients with evidence of capitated claims or negative total costs in any cost subcategory were excluded from cost analyses.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Descriptive statistics were used to describe demographic and clinical characteristics during the 12-month baseline period and to calculate unadjusted 12-month post-index all-cause HCRU and costs. Unadjusted differences in HCRU and costs between nonadherent/adherent and nonpersistent/persistent patients were assessed using chi-square tests for categorical variables and unpaired t-tests with unequal variances for continuous variables. Additionally, multivariable negative binomial models were used to calculate adjusted incidence rate ratios (IRRs) to assess the association between nonadherence or nonpersistence to antidepressants and 12-month post-index HCRU. Adjusted incremental mean differences in health care costs associated with nonadherence and nonpersistence were assessed using multivariable 2-part models (logistic regression to determine the probability of having non-zero costs, followed by generalized linear models using a log-link function and gamma distribution). A nonparametric bootstrapping procedure with 500 iterations was used to estimate 95% CIs for the mean incremental cost differences, which were obtained using the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles of the bootstrapped distribution. Multivariable HCRU and cost models were adjusted for the following variables: age, sex, geographic region, plan type, index year, Quan-CCI, index antidepressant class, and 12-month baseline total all-cause health care costs.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). P values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS

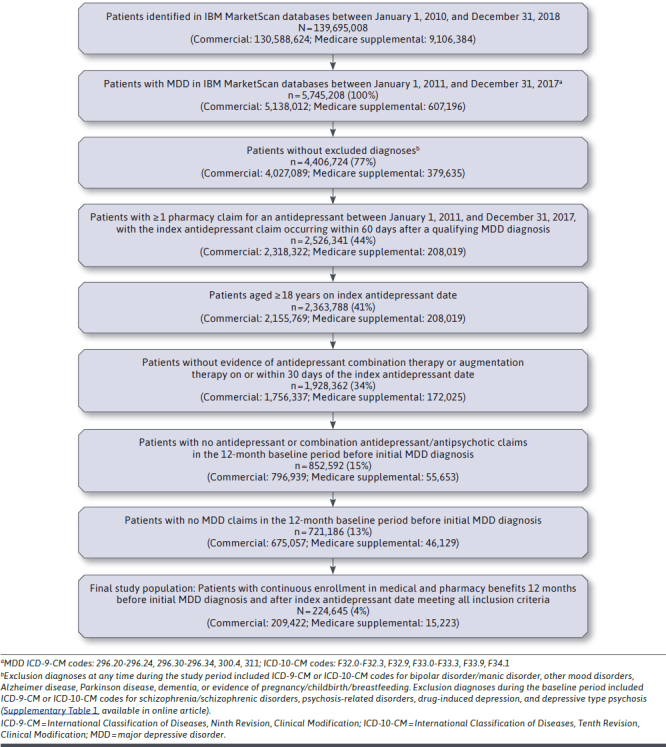

A total of 5,745,208 adult patients with MDD were identified in IBM MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplemental databases between January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2017 (Figure 2). Of these, 224,645 adult patients with MDD (commercial: n = 209,422; Medicare supplemental: n = 15,223) met all study inclusion criteria. The mean (SD) ages for the commercial and Medicare supplemental populations were 40 (14) and 75 (8) years, and the majority of patients were female (commercial: 61%; Medicare supplemental: 62%; Table 1). Most patients were enrolled in preferred provider organization plans in the commercial population (59%), whereas most patients were enrolled in comprehensive plans in the Medicare supplemental population (44%). Compared with adherent and persistent patients, nonadherent and nonpersistent patients had a higher prevalence of anxiety, alcohol-use disorder, substance-use disorder, and chronic pulmonary disease (Table 1). In both populations, the most commonly prescribed index antidepressants were selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (commercial: 73%; Medicare supplemental: 74%), followed by other antidepressant classes (commercial: 16%; Medicare supplemental: 15%). At 6 months, 48% and 49% of patients in the commercial population and 50% and 52% of patients in the Medicare supplemental population were nonadherent and nonpersistent to antidepressants, respectively.

FIGURE 2.

Study Identification Flowchart

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Characteristic | Commercial | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Patients (N = 209,422) | Adherent (n = 108,777) | Nonadherent (n = 100,645) | Persistent (n = 105,919) | Nonpersistent (n = 103,503) | ||

| Age, mean [SD], years | 40.1 [13.5] | 41.0 [13.4] | 39.1 [13.6]a | 41.1 [13.3] | 39.1 [13.6]a | |

| Female, n (%) | 127,987 (61.1) | 67,670 (62.2) | 60,317 (59.9)a | 66,170 (62.5) | 61,817 (59.7)a | |

| Plan type, n (%)d | ||||||

| Comprehensive | 5,810 (2.8) | 2,925 (2.7) | 2,885 (2.9) | 2,825 (2.7) | 2,985 (2.9) | |

| EPO | 1,813 (0.9) | 920 (0.9) | 893 (0.9) | 896 (0.9) | 917 (0.9) | |

| HMO | 27,611 (13.2) | 13,956 (12.8) | 13,655 (13.6) | 13,588 (12.8) | 14,023 (13.6) | |

| POS | 14,524 (6.9) | 7,279 (6.7) | 7,245 (7.2) | 7,057 (6.7) | 7,467 (7.2) | |

| PPO | 123,545 (59.0) | 64,293 (59.1) | 59,252 (58.9) | 62,665 (59.2) | 60,880 (58.8) | |

| POS with capitation | 1,225 (0.6) | 583 (0.5) | 642 (0.6) | 566 (0.5) | 659 (0.6) | |

| CDHP | 20,685 (9.9) | 10,921 (10.0) | 9,764 (9.7) | 10,649 (10.1) | 10,036 (9.7) | |

| HDHP | 11,763 (5.6) | 6,599 (6.1) | 5,164 (5.1) | 6,403 (6.1) | 5,360 (5.2) | |

| Unknown | 2,446 (1.2) | 1,301 (1.2) | 1,145 (1.1) | 1,270 (1.2) | 1,176 (1.1) | |

| Quan-CCI, mean [SD] | 0.29 [0.88] | 0.29 [0.88] | 0.29 [0.89] | 0.29 [0.87] | 0.29 [0.90] | |

| Quan-CCI, n (%)d | ||||||

| 0 | 175,366 (83.7) | 91,166 (83.8) | 84,200 (83.7) | 88,714 (83.8) | 86,652 (83.7) | |

| 1 | 20,569 (9.8) | 10,528 (9.7) | 10,041 (10.0) | 10,271 (9.7) | 10,298 (10.0) | |

| 2 | 8,698 (4.2) | 4,673 (4.3) | 4,025 (4.0) | 4,565 (4.3) | 4,133 (4.0) | |

| 3+ | 4,789 (2.3) | 2,410 (2.2) | 2,379 (2.4) | 2,369 (2.2) | 2,420 (2.3) | |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||||

| Anxiety | 38,125 (18.2) | 18,685 (17.2) | 19,440 (19.3)a | 18,262 (17.2) | 19,863 (19.2)a | |

| Alcohol disorder | 5,081 (2.4) | 2,091 (1.9) | 2,990 (3.0)a | 2,010 (1.9) | 3,071 (3.0)a | |

| Substance use disorder | 15,067 (7.2) | 6,338 (5.8) | 8,729 (8.7)a | 6,174 (5.8) | 8,893 (8.6)a | |

| Sleep disorders | 16,081 (7.7) | 8,461 (7.8) | 7,620 (7.6) | 8,255 (7.8) | 7,826 (7.6)c | |

| Coronary heart disease | 5,353 (2.6) | 2,790 (2.6) | 2,563 (2.6) | 2,771 (2.6) | 2,582 (2.5) | |

| Congestive heart failure | 1,896 (0.9) | 998 (0.9) | 898 (0.9) | 994 (0.9) | 902 (0.9) | |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 19,496 (9.3) | 9,914 (9.1) | 9,582 (9.5)b | 9,664 (9.1) | 9,832 (9.5)b | |

| Diabetes | 14,750 (7.0) | 7,610 (7.0) | 7,140 (7.1) | 7,455 (7.0) | 7,295 (7.1) | |

| Geographic region, n (%)d | ||||||

| Northeast | 30,834 (14.7) | 16,756 (15.4) | 14,078 (14.0) | 16,334 (15.4) | 14,500 (14.0) | |

| North Central | 52,427 (25.0) | 27,966 (25.7) | 24,461 (24.3) | 27,219 (25.7) | 25,208 (24.4) | |

| South | 80,995 (38.7) | 40,699 (37.4) | 40,296 (40.0) | 39,564 (37.4) | 41,431 (40.0) | |

| West | 43,269 (20.7) | 22,458 (20.7) | 20,811 (20.7) | 21,913 (20.7) | 21,356 (20.6) | |

| Unknown/N/A | 1,897 (0.9) | 898 (0.8) | 999 (1.0) | 889 (0.8) | 1,008 (1.0) | |

| Index antidepressant, n (%)d | ||||||

| SSRI | 153,244 (73.2) | 80,389 (73.9) | 72,855 (72.4) | 78,167 (73.8) | 75,077 (72.5) | |

| SNRI | 19,707 (9.4) | 10,718 (9.9) | 8,989 (8.9) | 10,581 (10.0) | 9,126 (8.8) | |

| TCA | 2,062 (1.0) | 615 (0.6) | 1,447 (1.4) | 620 (0.6) | 1,442 (1.4) | |

| MAOI | 17 (< 0.1) | 7 (< 0.1) | 10 (< 0.1) | 7 (< 0.1) | 10 (< 0.1) | |

| Othere | 34,392 (16.4) | 17,048 (15.7) | 17,344 (17.2) | 16,544 (15.6) | 17,848 (17.2) | |

| 12-month baseline all-cause health care costs, mean, 2019 USDf | ||||||

| Included patients, n (%) | 171,648 (82.0) | 89,467 (82.2) | 82,181 (81.7) | 87,095 (82.2) | 84,553 (81.7) | |

| Total health care [SD] | 9,205 [31,030] | 9,238 [30,246] | 9,169 [31,862] | 9,217 [30,153] | 9,194 [31,908] | |

| Total patient out-of-pocket [SD] | 1,199 [1,785] | 1,202 [1,723] | 1,196 [1,850] | 1,202 [1,724] | 1,196 [1,846] | |

| Medicare Supplemental | ||||||

| Characteristic | All Patients (N = 15,223) | Adherent (n = 7,648) | Nonadherent (n = 7,575) | Persistent (n = 7,333) | Nonpersistent (n = 7,890) | |

| Age, mean [SD], years | 74.6 [7.6] | 74.4 [7.4] | 74.8 [7.7]a | 74.4 [7.4] | 74.8 [7.7]a | |

| Female, n (%) | 9,476 (62.3) | 4,692 (61.4) | 4,784 (63.2)c | 4,477 (61.1) | 4,999 (63.4)b | |

| Plan type, n (%)d | ||||||

| Comprehensive | 6,739 (44.3) | 3,396 (44.4) | 3,343 (44.1) | 3,241 (44.2) | 3,498 (44.3) | |

| EPO | 13 (0.1) | 9 (0.1) | 4 (0.1) | 8 (0.1) | 5 (0.1) | |

| HMO | 2,006 (13.2) | 1,047 (13.7) | 959 (12.7) | 1,012 (13.8) | 994 (12.6) | |

| POS | 523 (3.4) | 277 (3.6) | 246 (3.3) | 277 (3.8) | 246 (3.1) | |

| PPO | 5,560 (36.5) | 2,715 (35.5) | 2,845 (37.6) | 2,598 (35.4) | 2,962 (37.5) | |

| POS with capitation | 190 (1.3) | 93 (1.2) | 97 (1.3) | 93 (1.3) | 97 (1.2) | |

| CDHP | 44 (0.3) | 26 (0.3) | 18 (0.2) | 22 (0.3) | 22 (0.3) | |

| HDHP | 17 (0.1) | 9 (0.1) | 8 (0.1) | 7 (0.1) | 10 (0.1) | |

| Unknown | 131 (0.9) | 76 (1.0) | 55 (0.7) | 75 (1.0) | 56 (0.7) | |

| Quan-CCI, mean [SD] | 1.31 [1.90] | 1.30 [1.90] | 1.31 [1.90] | 1.31 [1.90] | 1.31 [1.90] | |

| Quan-CCI, n (%)d | ||||||

| 0 | 7,314 (48.1) | 3,738 (48.9) | 3,576 (47.2) | 3,570 (48.7) | 3,744 (47.5) | |

| 1 | 2,854 (18.8) | 1,356 (17.7) | 1,498 (19.8) | 1,319 (18.0) | 1,535 (19.5) | |

| 2 | 2,288 (15.0) | 1,147 (15.0) | 1,141 (15.1) | 1,074 (14.7) | 1,214 (15.4) | |

| 3+ | 2,767 (18.2) | 1,407 (18.4) | 1,360 (18.0) | 1,370 (18.7) | 1,397 (17.7) | |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||||

| Anxiety | 2,690 (17.7) | 1,227 (16.0) | 1,463 (19.3)a | 1,185 (16.2) | 1,505 (19.1)a | |

| Alcohol disorder | 307 (2.0) | 127 (1.7) | 180 (2.4)b | 123 (1.7) | 184 (2.3)b | |

| Substance use disorder | 1,020 (6.7) | 452 (5.9) | 568 (7.5)a | 439 (6.0) | 581 (7.4)a | |

| Sleep disorders | 1,883 (12.4) | 926 (12.1) | 957 (12.6) | 899 (12.3) | 984 (12.5) | |

| Coronary heart disease | 3,816 (25.1) | 1,882 (24.6) | 1,934 (25.5) | 1,801 (24.6) | 2,015 (25.5) | |

| Congestive heart failure | 1,792 (11.8) | 907 (11.9) | 885 (11.7) | 888 (12.1) | 904 (11.5) | |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 3,697 (24.3) | 1,766 (23.1) | 1,931 (25.5)a | 1,717 (23.4) | 1,980 (25.1)c | |

| Diabetes | 3,893 (25.6) | 1,987 (26.0) | 1,906 (25.2) | 1,925 (26.3) | 1,968 (24.9) | |

| Geographic region, n (%)d | ||||||

| Northeast | 2,768 (18.2) | 1,487 (19.4) | 1,281 (16.9) | 1,425 (19.4) | 1,343 (17.0) | |

| North Central | 5,463 (35.9) | 2,565 (33.5) | 2,898 (38.3) | 2,479 (33.8) | 2,984 (37.8) | |

| South | 4,205 (27.6) | 2,148 (28.1) | 2,057 (27.2) | 2,061 (28.1) | 2,144 (27.2) | |

| West | 2,752 (18.1) | 1,433 (18.7) | 1,319 (17.4) | 1,354 (18.5) | 1,398 (17.7) | |

| Unknown/N/A | 35 (0.2) | 15 (0.2) | 20 (0.3) | 14 (0.2) | 21 (0.3) | |

| Index antidepressant, n (%)d | ||||||

| SSRI | 11,299 (74.2) | 5,867 (76.7) | 5,432 (71.7) | 5,635 (76.8) | 5,664 (71.8) | |

| SNRI | 1,448 (9.5) | 694 (9.1) | 754 (10.0) | 673 (9.2) | 775 (9.8) | |

| TCA | 194 (1.3) | 72 (0.9) | 122 (1.6) | 66 (0.9) | 128 (1.6) | |

| MAOI | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Othere | 2,282 (15.0) | 1,015 (13.3) | 1,267 (16.7) | 959 (13.1) | 1,323 (16.8) | |

| 12-month baseline all-cause health care costs, mean, 2019 USDf | ||||||

| Included patients, n (%) | 12,894 (84.7) | 6,428 (84.0) | 6,466 (85.4) | 6,151 (83.9) | 6,743 (85.5) | |

| Total health care [SD] | 28,153 [60,947] | 28,653 [62,055] | 27,655 [59,826] | 28,925 [61,875] | 27,448 [60,084] | |

| Total patient out-of-pocket [SD] | 1,273 [1,174] | 1,289 [1,275] | 1,258 [1,064] | 1,294 [1,271] | 1,254 [1,078] | |

Note: P values were calculated using chi-square tests for categorical values and t-tests for continuous values.

aP < 0.001 for comparison of nonadherent versus adherent patients or nonpersistent versus persistent patients.

bP < 0.01 for comparison of nonadherent versus adherent patients or nonpersistent versus persistent patients.

cP < 0.05 for comparison of nonadherent versus adherent patients or nonpersistent versus persistent patients.

dP < 0.05 for overall distribution of nonadherent versus adherent patients or nonpersistent versus persistent patients across all categories.

eOther antidepressants include bupropion, mirtazapine, nefazodone, and trazodone.

fCosts were adjusted to 2019 USD. Patients with any evidence of capitated claims or negative costs in any cost subcategory were excluded from cost analyses. Patient out-of-pocket costs represent sum of deductibles, copays, and coinsurance.

CDHP = consumer-driven health plan; EPO = exclusive provider organization; FFS = fee-for-service; HDHP = high-deductible health plan; HMO = health maintenance organization; MAOI = monoamine oxidase inhibitor; MDD = major depressive disorder; N/A = not applicable; POS = point of service; PPO = preferred provider organization; Quan-CCI = Quan-Charlson Comorbidity Index; SNRI = selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; TCA = tricyclic antidepressant; USD = U.S. dollars.

ALL-CAUSE HEALTH CARE RESOURCE UTILIZATION

A significantly greater proportion of nonadherent and nonpersistent patients had all-cause inpatient hospitalizations (commercial: 8% vs. 6% for both comparisons; all P < 0.001; Medicare supplemental: 24% vs. 21% for both comparisons; all P < 0.001) and ER visits (commercial: 24% vs. 19% for both comparisons; all P < 0.001; Medicare supplemental: 36% vs. 30% and 35% vs. 30%, respectively; all P < 0.001) compared with adherent and persistent patients, respectively. After adjustment for age, sex, plan type, geographic region, index year, Quan-CCI, index antidepressant class, and baseline 12-month total all-cause health care costs, nonadherent and nonpersistent patients in both the commercial and Medicare supplemental populations had significantly more hospitalizations (commercial, adjusted IRR [95% CI]: 1.34 [1.29 to 1.39] and 1.32 [1.27 to 1.36]; Medicare supplemental: 1.19 [1.12 to 1.28] and 1.18 [1.10 to 1.26]) and ER visits (commercial, adjusted IRR [95% CI]: 1.43 [1.40 to 1.45] and 1.41 [1.38 to 1.44]; Medicare supplemental: 1.28 [1.21 to 1.36] and 1.28 [1.21 to 1.36]) compared with adherent and persistent patients (Table 2). Nonadherent and nonpersistent patients had significantly fewer pharmacy claims compared with adherent and persistent patients (commercial, adjusted IRR [95% CI]: 0.67 [0.67 to 0.67] and 0.66 [0.66 to 0.66]; Medicare supplemental: 0.83 [0.81 to 0.84] and 0.81 [0.79 to 0.82]). In the commercial population, nonadherent and nonpersistent patients had fewer physician office visits, whereas mean physician office visits were not significantly different between nonadherent/adherent and nonpersistent/persistent patients in the Medicare supplemental population (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

12-Month All-Cause Health Care Resource Utilization

| Commercial Population | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adherent (n = 108,777) | Nonadherent (n = 100,645) | Incidence Rate Ratio (95% CI) | Persistent (n = 105,919) | Nonpersistent (n = 103,503) | Incidence Rate Ratio (95% CI) | |

| Unadjusted HCRU, mean [SD] | ||||||

| Inpatient hospitalizations | 0.08 [0.39] | 0.11 [0.50]a | 1.36 (1.31 to 1.41) | 0.08 [0.40] | 0.11 [0.48]a | 1.33 (1.28 to 1.38) |

| Emergency room | 0.29 [0.83] | 0.42 [1.20]a | 1.45 (1.42 to 1.48) | 0.29 [0.84] | 0.42 [1.19]a | 1.44 (1.41 to 1.47) |

| Outpatient (all) | 19.39 [18.48] | 17.22 [17.95]a | 0.89 (0.88 to 0.89) | 19.46 [18.58] | 17.21 [17.85]a | 0.88 (0.88 to 0.89) |

| Physician office | 14.45 [13.52] | 12.21 [12.18]a | 0.85 (0.84 to 0.85) | 14.51 [13.56] | 12.22 [12.17]a | 0.84 (0.84 to 0.85) |

| Other | 4.94 [9.98] | 5.01 [10.73] | 1.01 (1.00 to 1.03) | 4.96 [10.10] | 4.99 [10.59] | 1.01 (1.00 to 1.02) |

| Pharmacy | 27.22 [19.60] | 18.30 [17.15]a | 0.67 (0.67 to 0.68) | 27.57 [19.64] | 18.19 [17.05]a | 0.66 (0.66 to 0.66) |

| Adjusted HCRU, meanc | ||||||

| Inpatient hospitalizations | 0.07 | 0.10a | 1.34 (1.29 to 1.39) | 0.07 | 0.10a | 1.32 (1.27 to 1.36) |

| Emergency room | 0.28 | 0.40a | 1.43 (1.40 to 1.45) | 0.28 | 0.40a | 1.41 (1.38 to 1.44) |

| Outpatient (all) | 19.21 | 17.14a | 0.89 (0.89 to 0.90) | 19.27 | 17.13a | 0.89 (0.88 to 0.90) |

| Physician office | 14.51 | 12.35a | 0.85 (0.85 to 0.86) | 14.55 | 12.36a | 0.85 (0.84 to 0.86) |

| Other | 4.51 | 4.65a | 1.03 (1.02 to 1.04) | 4.52 | 4.64a | 1.03 (1.01 to 1.04) |

| Pharmacy | 25.73 | 17.24a | 0.67 (0.67 to 0.67) | 26.03 | 17.15a | 0.66 (0.66 to 0.66) |

| Medicare Supplemental Population | ||||||

| Adherent (n=7,648) | Nonadherent (n = 7,575) | Incidence Rate Ratio (95% CI) | Persistent (n = 7,333) | Nonpersistent (n = 7,890) | Incidence Rate Ratio (95% CI) | |

| Unadjusted HCRU, mean [SD] | ||||||

| Inpatient hospitalizations | 0.28 [0.63] | 0.34 [0.78]a | 1.21 (1.13 to 1.29) | 0.29 [0.64] | 0.34 [0.77]a | 1.17 (1.09 to 1.26) |

| Emergency room | 0.53 [1.10] | 0.68 [1.37]a | 1.29 (1.21 to 1.37) | 0.53 [1.09] | 0.68 [1.36]a | 1.28 (1.21 to 1.36) |

| Outpatient (all) | 30.61 [27.31] | 31.40 [28.00] | 1.03 (1.00 to 1.05) | 30.87 [27.63] | 31.13 [27.68] | 1.01 (0.98 to 1.03) |

| Physician office | 17.29 [15.03] | 16.86 [14.04] | 0.97 (0.95 to 1.00) | 17.34 [15.09] | 16.83 [14.03]b | 0.97 (0.95 to 1.00) |

| Other | 13.31 [21.48] | 14.55 [22.61]a | 1.09 (1.05 to 1.14) | 13.53 [21.88] | 14.30 [22.21]b | 1.06 (1.02 to 1.10) |

| Pharmacy | 43.30 [27.27] | 35.86 [24.84]a | 0.83 (0.81 to 0.84) | 43.95 [27.52] | 35.55 [24.53]a | 0.81 (0.79 to 0.82) |

| Adjusted HCRU, meanc | ||||||

| Inpatient hospitalizations | 0.26 | 0.31a | 1.19 (1.12 to 1.28) | 0.26 | 0.31a | 1.18 (1.10 to 1.26) |

| Emergency room | 0.51 | 0.65a | 1.28 (1.21 to 1.36) | 0.50 | 0.65a | 1.28 (1.21 to 1.36) |

| Outpatient (all) | 30.13 | 30.82c | 1.02 (1.00 to 1.05) | 30.33 | 30.61 | 1.01 (0.99 to 1.03) |

| Physician office | 17.09 | 16.92 | 0.99 (0.97 to 1.02) | 17.16 | 16.86 | 0.98 (0.96 to 1.01) |

| Other | 12.02 | 13.12a | 1.09 (1.05 to 1.13) | 12.12 | 12.98a | 1.07 (1.03 to 1.11) |

| Pharmacy | 43.46 | 35.87a | 0.83 (0.81 to 0.84) | 44.05 | 35.60a | 0.81 (0.79 to 0.82) |

Note: P values for unadjusted HCRU comparisons were calculated using chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for means of continuous values. Adjusted mean HCRU estimates and IRRs were calculated using multivariable negative binomial regression adjusted for age, sex, plan type, geographic region, index year, Quan-CCI, index antidepressant class, and baseline 12-month total all-cause health care costs. IRRs reflect comparison of nonadherent versus adherent patients and nonpersistent versus persistent patients.

aP < 0.001 for comparison of nonadherent versus adherent patients or nonpersistent versus persistent patients.

bP < 0.05 for comparison of nonadherent versus adherent patients or nonpersistent versus persistent patients.

c17 patients in the commercial population (<0.0001%) and 3 patients in the Medicare population (<0.001%) with negative baseline costs were excluded from multivariable negative binomial models due to convergence issues.

HCRU = health care resource utilization; IRR = incidence rate ratio; PPPY = per patient per year; Quan-CCI = Quan Charlson Comorbidity Index.

ALL-CAUSE HEALTH CARE COSTS

Nonadherent and nonpersistent patients in the commercial and Medicare supplemental populations incurred significantly higher adjusted mean medical, inpatient, and ER costs and significantly lower adjusted mean pharmacy costs (Table 3). Nonadherence to antidepressants in the commercial/Medicare supplemental populations were associated with $568 (95% CI: $354 to $764)/$1,621 ($314 to $2,774) higher medical costs; $650 ($490 to $801)/$1,546 ($705 to $2,308) higher inpatient costs; $130 ($115 to $143)/$82 ($23 to $150) higher ER costs; and $561 (−$601 to −$521)/$510 (−$747 to −$227) lower pharmacy costs (Table 3). Similarly, incremental mean (95% CI) medical, inpatient, ER, and pharmacy costs associated with nonpersistence in the commercial/Medicare supplemental populations were $491 ($284 to $703)/$1,764 ($451 to $2,925), $564 ($417 to $716)/$1,567 ($778 to $2,331), $129 ($115 to $142)/$80 ($18 to $150), and −$576 (−$617 to −$540)/−$596 (−$830 to −$325), respectively. Adjusted outpatient and total health care costs were not significantly different between nonadherent/adherent and nonpersistent/persistent patients in both the commercial and Medicare supplemental populations (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

12-Month All-Cause Health Care Costs Following Index Antidepressant

| Commercial Population | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adherent (n = 89,468) | Nonadherent (n = 82,145) | Incremental Difference (95% CI) | Persistent (n = 87,096) | Nonpersistent (n = 84,517) | Incremental Difference (95% CI) | |

| Unadjusted health care costs, mean [SD], 2019 USD | ||||||

| Total | 10,875 [28,306] | 11,058 [36,362] | 183 (−127 to 493) | 10,938 [28,551] | 10,988 [35,961] | 50 (−258 to 358) |

| Medical | 8,466 [25,853] | 9,264 [34,414]a | 798 (508 to 1,088) | 8,511 [26,029] | 9,196 [34,067]a | 685 (397 to 972) |

| Inpatient | 1,868 [15,120] | 2,566 [23,067]a | 699 (512 to 885) | 1,907 [15,337] | 2,506 [22,734]a | 599 (415 to 783) |

| Emergency room | 332 [1,311] | 470 [1,784]a | 138 (123 to 153) | 329 [1,302] | 469 [1,779]a | 139 (125 to 154) |

| Outpatient (all) | 6,267 [17,005] | 6,228 [19,864] | −39 (−214 to 137) | 6,274 [16,959] | 6,221 [19,830] | −54 (−228 to 121) |

| Physician office | 2,406 [4,975] | 2,098 [4,624]a | −309 (−354 to −263) | 2,411 [4,942] | 2,102 [4,670]a | −309 (−355 to −264) |

| Other | 3,860 [15,306] | 4,130 [18,526]b | 270 (109 to 432) | 3,864 [15,321] | 4,119 [18,431]b | 256 (95 to 416) |

| Pharmacy | 2,408 [8,295] | 1,794 [8,617]a | −615 (−695 to −534) | 2,427 [8,310] | 1,792 [8,593]a | −635 (−715 to −555) |

| Adjusted health care costs, mean, 2019 USD | ||||||

| Total | 9,026 | 9,030 | 4 (−204 to 216) | 9,072 | 8,982 | −89 (−303 to 144) |

| Medical | 7,059 | 7,627 | 568 (354 to 764) | 7,089 | 7,580 | 491 (284 to 703) |

| Inpatient | 1,633 | 2,283 | 650 (490 to 801) | 1,666 | 2,230 | 564 (417 to 716) |

| Emergency room | 310 | 440 | 130 (115 to 143) | 309 | 438 | 129 (115 to 142) |

| Outpatient (all) | 5,415 | 5,389 | −26 (−130 to 79) | 5,429 | 5,376 | −52 (−161 to 57) |

| Physician office | 2,347 | 2,090 | −257 (−289 to −220) | 2,355 | 2,090 | −265 (−295 to −225) |

| Other | 3,356 | 3,642 | 286 (183 to 387) | 3,362 | 3,629 | 267 (166 to 374) |

| Pharmacy | 1,930 | 1,370 | −561 (−601 to −521) | 1,947 | 1,371 | −576 (−617 to −540) |

| Medicare Supplemental Population | ||||||

| Adherent (n = 6,430) | Nonadherent (n = 6,466) | Incremental Difference (95% CI) | Persistent (n=6,153) | Nonpersistent (n = 6,743) | Incremental Difference (95% CI) | |

| Unadjusted health care costs, mean [SD], 2019 USD | ||||||

| Total | 26,242 [62,525] | 26,867 [62,200] | 625 (−1,528 to 2,778) | 26,133 [61,547] | 26,940 [63,096] | 807 (−1,346 to 2,959) |

| Medical | 21,538 [60,632] | 22,745 [60,465] | 1,207 (−884 to 3,297) | 21,372 [59,602] | 22,848 [61,396] | 1,476 (−614 to 3,565) |

| Inpatient | 6,531 [26,473] | 7,913 [30,041]b | 1,383 (405 to 2,360) | 6,625 [29,071] | 7,770 [27,619]c | 1,146 (165 to 2,127) |

| Emergency room | 612 [3,164] | 665 [3,165] | 53 (−56 to 162) | 616 [3,208] | 659 [3,124] | 43 (−66 to 153) |

| Outpatient (all) | 14,396 [46,664] | 14,167 [44,025] | −229 (−1,795 to 1,337) | 14,131 [43,389] | 14,418 [47,087] | 287 (−1,275 to 1,848) |

| Physician office | 4,071 [9,455] | 3,642 [7,717]b | −429 (−727 to −131) | 4,092 [9,552] | 3,639 [7,688]b | −453 (−754 to −152) |

| Other | 10,325 [44,036] | 10,525 [42,447] | 200 (−1,293 to 1,693) | 10,039 [40,524] | 10,778 [45,587] | 740 (−747 to 2,226) |

| Pharmacy | 4,703 [9,873] | 4,121 [9,825]a | −58 (−922 to −242) | 4,761 [9,752] | 4,092 [9,933]a | −669 (−1,009 to −329) |

| Adjusted health care costs, mean, 2019 USD | ||||||

| Total | 23,304 | 24,309 | 1,005 (−414 to 2,237) | 23,226 | 24,320 | 1,094 (−305 to 2,327) |

| Medical | 18,625 | 20,246 | 1,621 (314 to 2,774) | 18,494 | 20,258 | 1,764 (451 to 2,925) |

| Inpatient | 6,361 | 7,907 | 1,546 (705 to 2,308) | 6,309 | 7,876 | 1,567 (778 to 2,331) |

| Emergency room | 471 | 553 | 82 (23 to 150) | 470 | 550 | 80 (18 to 150) |

| Outpatient (all) | 12,177 | 12,300 | 123 (−709 to 930) | 12,084 | 12,370 | 286 (−476 to 1,009) |

| Physician office | 3,824 | 3,720 | −104 (−311 to 109) | 3,841 | 3,710 | −131 (−335 to 71) |

| Other | 8,783 | 8,983 | 200 (−568 to 973) | 8,654 | 9,078 | 424 (−370 to 1,161) |

| Pharmacy | 4,494 | 3,985 | −510 (−747 to −227) | 4,546 | 3,951 | −596 (−830 to −325) |

Note: Costs were adjusted to 2019 USD. Patients with any evidence of capitated claims or negative total costs in any cost subcategory were excluded from cost analyses. Unadjusted cost differences were determined using 2-sample t-tests with unequal variances, and adjusted incremental cost differences were calculated using multivariable 2-part models (logistic regression followed by generalized linear models with log-link and gamma distribution) adjusted for age, sex, plan type, geographic region, index year, Quan-CCI, index antidepressant class, and baseline 12-month total all-cause health care costs. Significance of adjusted incremental cost differences based on 95% CIs obtained via nonparametric bootstrapping procedure (N = 500).

aP < 0.001 for comparison of nonadherent versus adherent patients or nonpersistent versus persistent patients.

bP < 0.01 for comparison of nonadherent versus adherent patients or nonpersistent versus persistent patients.

cP< 0.05 for comparison of nonadherent versus adherent patients or nonpersistent versus persistent patients.

Quan-CCI = Charlson Comorbidity Index; USD = U.S. dollar.

Discussion

This large retrospective U.S. administrative claims database study assessed the effect of nonadherence and nonpersistence to antidepressants on 12-month all-cause HCRU and costs among adult patients with MDD who initiated antidepressant therapy for a new MDD episode. Consistent with previous studies, adherence and persistence to antidepressants at 6 months were poor among both commercially insured patients and Medicare beneficiaries with Medicare supplemental insurance, with only approximately 50% of patients remaining adherent or persistent to antidepressants at 6 months.

Our findings support and extend previous work on the association between nonadherence and nonpersistence to antidepressants and all-cause HCRU and costs in patients with MDD. Similar to previous studies, our study found greater all-cause inpatient hospitalizations and ER use among nonadherent and nonpersistent patients compared with adherent and persistent patients, respectively.7,8,27 Also consistent with previous research,8,9,25,26,28 nonadherence and nonpersistence were associated with significantly higher adjusted medical costs in both the commercial and Medicare supplemental populations, which were largely driven by approximately 20%-40% higher inpatient hospitalization and ER costs among nonadherent and nonpersistent patients. Given the association between nonremission and poor depression treatment outcomes, the higher medical costs and rates of hospitalizations and ER visits among antidepressant nonadherent and nonpersistent patients may, in part, reflect higher rates of nonremission among these patients.

Of note, Medicare supplemental patients who were nonadherent and nonpersistent to antidepressants incurred the highest HCRU and health care costs. Compared with younger patients, older adults with depression are more likely to experience higher comorbidity burden,44 which was similarly reflected in our study; Medicare supplemental patients with MDD in our study had a markedly higher prevalence of comorbid coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure, chronic pulmonary disease, and diabetes. There is also evidence that older patients with MDD have a poorer depression prognosis compared with younger patients with MDD.44 These factors may therefore contribute to higher health care spending compared with younger, healthier patients with depression.

Total health care costs were not significantly different between nonadherent/adherent and nonpersistent/persistent patients in this study, as medical cost savings due to reductions in HCRU among adherent and persistent patients may not sufficiently offset the higher pharmacy costs due to improved antidepressant adherence and persistence in the short term. It is plausible that the potential benefits of improved antidepressant adherence and persistence may not be fully realized in the short term, as various real-world observational studies have found a significantly lower risk of relapse or recurrence (e.g., evidence of mental health-related ER visit, psychiatric hospitalization, suicide attempt, evidence of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), or re-initiation of MDD pharmacotherapy after a gap of 6 months) over follow-up periods of up to 2 years among patients who were adherent to antidepressants during the first 6 months of treatment compared with those who were nonadherent to antidepressants.21-23 Furthermore, adherence and persistence to antidepressant therapy for MDD are associated with better medication adherence and improved clinical outcomes for comorbid conditions, including diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cardiovascular disease.9,24,26,45 Similarly, the effect of improved antidepressant adherence and persistence on other comorbid conditions may be associated with longer-term cost savings.

Overall, the high rates of antidepressant nonadherence and nonpersistence in our study, which were associated with greater all-cause hospitalizations and ER use, suggest inadequate depression treatment for a large proportion of patients with MDD and, therefore, highlight a continued need for effective strategies to improve antidepressant adherence and persistence, which may improve outcomes and reduce the health care burden associated with MDD. Interventions to improve antidepressant adherence and persistence may have important implications for health systems and managed care organizations, given the potential cost savings attributable to improved depression treatment outcomes,16,17,19 as well as continued efforts to incentivize quality depression care in health care organizations.46-48 Such efforts are evidenced by the continued adoption of NCQA HEDIS AMM measures for effective acute and continuation phase antidepressant treatment in provider pay-for-performance initiatives and merit-based incentive programs,46 as well as the emergence of the NCQA HEDIS Depression Remission or Response outcomes measures, which evaluate the percentage of health plan members achieving treatment response and remission,49 in various value-based payment arrangements.47,50 Previous research has highlighted the clinical and economic benefits of interventions aimed at improving the quality of depression care in diverse practice settings, including collaborative care programs51-55 and psychosocial interventions,56,57 which have been found to improve antidepressant adherence and longer-term depression outcomes.53,54 In the context of continued industry efforts to improve the quality of depression care, these findings therefore underscore the contemporary importance of strategies that promote better antidepressant adherence and persistence to improve depression care, and various measures, such as pay-for-performance initiatives, expansion of mental health benefits, and coverage of disease management and collaborative care programs, have been suggested as effective strategies to improve antidepressant adherence/persistence and depression treatment.13,48,55,58,59

LIMITATIONS

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, the calculation of adherence and persistence to antidepressants was based on pharmacy claims data, which do not confirm whether patients consumed their medication. The PDC and persistence calculations used in this study also did not account for the effect of hospitalization on adherence and persistence estimates.60

Second, as with other retrospective claims database studies, this study is subject to limitations inherent to administrative claims databases, including data coding errors, omissions, and misclassification.

Third, this study did not consider indirect costs such as absenteeism or presenteeism costs, which have been found to be substantial in MDD and estimated to account for up to 50% of the economic burden of MDD in the United States.3 Burton et al. (2007) found that employees who were nonadherent to acute and continuation phase antidepressant therapy were 39%-46% more likely to have short-term disability claims compared with adherent employees.61 Therefore, the costs associated with nonadherence and nonpersistence to antidepressants are likely underestimated in this study.

Fourth, although various baseline characteristics were adjusted for in multivariable analyses, additional factors that may contribute to adherence, persistence, HCRU, and health care costs in MDD, such as depression severity,13,62 prescriber specialty,63,64 specific treatment patterns (e.g., combination antidepressant therapy, augmentation therapy, switching, dose escalation),28,29,34,65-67 or other clinical characteristics, were not assessed or adequately captured and, therefore, could not be controlled for. For example, patients who require treatment switches, dose escalation, combination antidepressant therapy, or augmentation therapy may represent more complex, difficult-to-treat patients, regardless of adherence or persistence.

Finally, the study population was limited to adult patients with MDD who initiated antidepressant therapy for a new MDD episode and were enrolled in commercial and Medicare supplemental insurance plans. Therefore, these findings may not be generalizable to patients with MDD who have different characteristics from our study population, including patients with treatment-resistant depression, patients with insurance coverage outside of commercial or Medicare supplemental insurance plans, and uninsured individuals.

Despite these limitations, there are several strengths of this study. First, this study provides a comprehensive update to the existing literature on the economic effect of antidepressant nonadherence and nonpersistence in MDD; to our knowledge, this study is the largest real-world observational study to assess the association between antidepressant nonadherence and nonpersistence and HCRU and costs in adult MDD patients to date, with more than 200,000 adult patients with MDD included in this study. Our patient population was representative of patients with MDD from diverse geographic regions across the United States and enrolled in various insurance plans (i.e., commercial and Medicare supplemental insurance plans) and plan types (i.e., capitated and noncapitated plans). Additionally, our study includes newer antidepressants that have been introduced since 2010, so this study serves to provide a contemporary update on the current landscape of MDD medication adherence and persistence and their effect on HCRU and costs in patients with MDD.

Conclusions

The results of our study suggest that greater hospitalization and ER use and total medical costs are incurred among patients who are nonadherent and nonpersistent to antidepressant therapy compared with those who are adherent and persistent, which was observed in both the commercial and Medicare supplemental populations. Higher medical costs were largely driven by significantly higher inpatient hospitalization and ER costs among nonadherent and nonpersistent patients. Although clinical guidelines emphasize the importance of adherence and persistence to achieve remission and prevent depressive relapse and recurrence, adherence and persistence to existing MDD treatments remain suboptimal. The low rates of antidepressant adherence and persistence observed in this study reflect a continued unmet need for effective strategies that promote better adherence and persistence, which may increase the likelihood of achieving long-term recovery from depression and reduce the health care burden associated with MDD.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Institute of Mental Health. Major depression. February 2019. Accessed January 6, 2021. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/major-depression.shtml [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Depression. January 30, 2020. Accessed January 6, 2021. http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenberg PE, Fournier A-A, Sisitsky T, Pike CT, Kessler RC. The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2005 and 2010). J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(2):155-62. doi:10.4088/JCP.14m09298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychiatric Association. Practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder, 3rd edition. October 2010. Accessed January 6, 2021. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/mdd.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Committee for Quality Assurance. Antidepressant medication management (AMM). 2020. Accessed January 6, 2021. https://www.ncqa.org/hedis/measures/antidepressant-medication-management/ [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keyloun KR, Hansen RN, Hepp Z, Gillard P, Thase ME, Devine EB. Adherence and persistence across antidepressant therapeutic classes: a retrospective claims analysis among insured U.S. patients with major depressive disorder (MDD). CNS Drugs. 2017;31(5):421-32. doi:10.1007/s40263-017-0417-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu X, Tepper PG, Able SL. Adherence and persistence with duloxetine and hospital utilization in patients with major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;26(3):173-80. doi:10.1097/YIC.0b013e328343ba1e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.White TJ, Vanderplas A, Ory C, Dezii CM, Chang E. Economic impact of patient adherence with antidepressant therapy within a managed care organization. Dis Manag Heal Outcomes. 2003;11(12):817-22. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vega C, Becker RV, Mucha L, Lorenz BH, Eaddy MT, Ogbonnaya AO. Impact of adherence to antidepressants on healthcare outcomes and costs among patients with type 2 diabetes and comorbid major depressive disorder. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33(10):1879-89. doi:10.1080/03007995.2017.1347092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yau W-Y, Chan M-C, Wing Y-K, et al. Noncontinuous use of antidepressant in adults with major depressive disorders - a retrospective cohort study. Brain Behav. 2014;4(3):390-97. doi:10.1002/brb3.224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fortney JC, Pyne JM, Edlund MJ, et al. Reasons for antidepressant nonadherence among veterans treated in primary care clinics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(6):827-34. doi:10.4088/JCP.09m05528blu [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ho SC, Jacob SA, Tangiisuran B. Barriers and facilitators of adherence to antidepressants among outpatients with major depressive disorder: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0179290. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0179290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaspar FW, Zaidel CS, Dewa CS. Rates and determinants of use of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy by patients with major depressive disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70(4):262-70. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201800275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown C, Battista DR, Bruehlman R, Sereika SS, Thase ME, Dunbar-Jacob J. Beliefs about antidepressant medications in primary care patients: relationship to self-reported adherence. Med Care. 2005;43(12):1203-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aikens JE, Nease DEJ, Klinkman MS. Explaining patients’ beliefs about the necessity and harmfulness of antidepressants. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(1):23-29. doi:10.1370/afm.759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sobocki P, Ekman M, Agren H, Runeson B, Jönsson B. The mission is remission: health economic consequences of achieving full remission with antidepressant treatment for depression. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60(7):791-98. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.00997.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mauskopf JA, Simon GE, Kalsekar A, Nimsch C, Dunayevich E, Cameron A. Nonresponse, partial response, and failure to achieve remission: humanistic and cost burden in major depressive disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(1):83-97. doi:10.1002/da.20505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knoth RL, Bolge SC, Kim E, Tran Q-V. Effect of inadequate response to treatment in patients with depression. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(8):e188-96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dennehy EB, Robinson RL, Stephenson JJ, et al. Impact of non-remission of depression on costs and resource utilization: From the COmorbidities and symptoms of DEpression (CODE) study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2015;31(6):1165-77. doi:10.1185/03007995.2015.1029893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Byford S, Barrett B, Despiégel N, Wade A. Impact of treatment success on health service use and cost in depression: longitudinal database analysis. Pharmacoeconomics. 2011;29(2):157-70. doi:10.2165/11537360-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sood N, Treglia M, Obenchain RL, Dulisse B, Melfi CA, Croghan TW. Determinants of antidepressant treatment outcome. Am J Manag Care. 2000;6(12):1327-36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Melfi CA, Chawla AJ, Croghan TW, Hanna MP, Kennedy S, Sredl K. The effects of adherence to antidepressant treatment guidelines on relapse and recurrence of depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(12):1128-32. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.55.12.1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim K-H, Lee S-M, Paik J-W, Kim N-S. The effects of continuous antidepressant treatment during the first 6 months on relapse or recurrence of depression. J Affect Disord. 2011;132(1-2):121-29. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2011.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooper DC, Trivedi RB, Nelson KM, et al. Antidepressant adherence and risk of coronary artery disease hospitalizations in older and younger adults with depression. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(7):1238-45. doi:10.1111/jgs.12849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cantrell CR, Eaddy MT, Shah MB, Regan TS, Sokol MC. Methods for evaluating patient adherence to antidepressant therapy: a real-world comparison of adherence and economic outcomes. Med Care. 2006;44(4):300-03. doi:10.1097/01. mlr.0000204287.82701.9b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katon W, Cantrell CR, Sokol MC, Chiao E, Gdovin JM. Impact of antidepressant drug adherence on comorbid medication use and resource utilization. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(21):2497-503. doi:10.1001/archinte.165.21.2497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cui Z, Faries DE, Gelwicks S, Novick D, Liu X. Early discontinuation and suboptimal dosing of duloxetine treatment in patients with major depressive disorder: analysis from a U.S. third-party payer perspective. J Med Econ. 2012;15(1):134-44. doi:10.3111/13696998.2011.632043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eaddy MT, Druss BG, Sarnes MW, Regan TS, Frankum LE. Relationship of total health care charges to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor utilization patterns including the length of antidepressant therapy–results from a managed care administrative claims database. J Manag Care Pharm. 2005;11(2):145-50. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2005.11.2.145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thompson D, Buesching D, Gregor KJ, Oster G. Patterns of antidepressant use and their relation to costs of care. Am J Manag Care. 1996;2(9):1239-46. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ho SC, Chong HY, Chaiyakunapruk N, Tangiisuran B, Jacob SA. Clinical and economic impact of nonadherence to antidepressants in major depressive disorder: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2016;193:1-10. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chong WW, Aslani P, Chen TF. Effectiveness of interventions to improve antidepressant medication adherence: a systematic review. Int J Clin Pract. 2011;65(9):954-75. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2011.02746.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Chronic conditions. January 15, 2021. Accessed January 6, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Chronic-Conditions/CC_Main [Google Scholar]

- 33.IBM Watson Health. IBM MarketScan research databases for life sciences researchers. Accessed January 6, 2021. https://www.ibm.com/products/marketscan-research-databases [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gauthier G, Guerin A, Zhdanava M, et al. Treatment patterns, healthcare resource utilization, and costs following first-line antidepressant treatment in major depressive disorder: a retrospective U.S. claims database analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):222. doi:10.1186/s12888-017-1385-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(6):676-82. doi:10.1093/aje/kwq433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choudhry NK, Shrank WH, Levin RL, et al. Measuring concurrent adherence to multiple related medications. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15(7):457-64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pharmacy Quality Alliance. Adherence: PQA adherence measures. 2018. Accessed January 6, 2021. https://www.pqaalliance.org/adherence-measures [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martin BC, Wiley-Exley EK, Richards S, Domino ME, Carey TS, Sleath BL. Contrasting measures of adherence with simple drug use, medication switching, and therapeutic duplication. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(1):36-44. doi:10.1345/aph.1K671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Calculating proportion of days covered (PDC) for antihypertensive and antidiabetic medications: an evaluation guide for grantees. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Andrade SE, Kahler KH, Frech F, Chan KA. Methods for evaluation of medication adherence and persistence using automated databases. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15(8):565-67. doi:10.1002/pds.1230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu C-H, Farley JF, Gaynes BN. The association between antidepressant dosage titration and medication adherence among patients with depression. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29(6):506-14. doi:10.1002/da.21952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index (CPI) databases. Accessed January 18, 2021. https://www.bls.gov/cpi/data.htm [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mitchell AJ, Subramaniam H. Prognosis of depression in old age compared to middle age: a systematic review of comparative studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(9):1588-601. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Albrecht JS, Khokhar B, Huang T-Y, et al. Adherence and healthcare utilization among older adults with COPD and depression. Respir Med. 2017;129:53-58. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2017.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Explore measures and activities. Accessed January 6, 2021. https://qpp.cms.gov/mips/explore-measures?tab=qualityMeasures&py=2020#measures [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shields A. Depression HEDIS metrics that matter and how they impact practice steering toward success : achieving value in whole person care. October 27, 2017. Accessed January 6, 2021. https://depts.washington.edu/fammed/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/11-Depression-HEDIS-Metrics-that-Matter.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bao Y, McGuire TG, Chan Y-F, et al. Value-based payment in implementing evidence-based care: the Mental Health Integration Program in Washington state. Am J Manag Care. 2017;23(1):48-53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.National Committee for Quality Assurance. Depression remission or response for adolescents and adults (DRR). 2020. Accessed January 6, 2021. https://www.ncqa.org/hedis/measures/depression-remission-or-response-for-adolescents-and-adults/ [Google Scholar]

- 50.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Services. Medicare Shared Savings Program quality measure benchmarks for the 2020/2021 performance years. 2020-2021. Accessed January 6, 2021. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/20202021-quality-benchmarks.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 51.Simon GE, Katon WJ, VonKorff M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a collaborative care program for primary care patients with persistent depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(10):1638-44. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Katon WJ, Seelig M. Population-based care of depression: team care approaches to improving outcomes. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50(4):459-67. doi:10.1097/JOM.0b013e318168efb7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(21):2314-21. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.21.2314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thota AB, Sipe TA, Byard GJ, et al. Collaborative care to improve the management of depressive disorders: a community guide systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(5):525-38. doi:10.1016/j. amepre.2012.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Unutzer J, Katon WJ, Fan M-Y, et al. Long-term cost effects of collaborative care for late-life depression. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(2):95-100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sirey JA, Bruce ML, Kales HC. Improving antidepressant adherence and depression outcomes in primary care: the treatment initiation and participation (TIP) program. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(6):554-62. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181cdeb7d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sirey JA, Banerjee S, Marino P, et al. Adherence to depression treatment in primary care: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(11):1129-35. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Little A, Hansen RA, Gartlehner G, Gray C. Impact of the STAR*D trial from the perspective of the payer. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(11):1463-65. doi:10.1176/ps.2009.60.11.1463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Unützer J, Chan Y-F, Hafer E, et al. Quality improvement with pay-for-performance incentives in integrated behavioral health care. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(6):e41-45. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dong YH, Choudhry NK, Krumme A, et al. Impact of hospitalization on medication adherence estimation in claims data. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2017;42(3):318-28. doi:10.1111/jcpt.12517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Burton WN, Chen C-Y, Conti DJ, Schultz AB, Edington DW. The association of antidepressant medication adherence with employee disability absences. Am J Manag Care. 2007;13(2):105-12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Birnbaum HG, Kessler RC, Kelley D, Ben-Hamadi R, Joish VN, Greenberg PE. Employer burden of mild, moderate, and severe major depressive disorder: mental health services utilization and costs, and work performance. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27(1):78-89. doi:10.1002/da.20580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stein MB, Cantrell CR, Sokol MC, Eaddy MT, Shah MB. Antidepressant adherence and medical resource use among managed care patients with anxiety disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(5):673-80. doi:10.1176/ps.2006.57.5.673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Robinson RL, Long SR, Chang S, et al. Higher costs and therapeutic factors associated with adherence to NCQA HEDIS antidepressant medication management measures: analysis of administrative claims. J Manag Care Pharm. 2006;12(1):43-54. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2006.12.1.43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Broder MS, Greene M, Yan T, Chang E, Hartry A, Yermilov I. Medication adherence, health care utilization, and costs in patients with major depressive disorder initiating adjunctive atypical antipsychotic treatment. Clin Ther. 2019;41(2):221-32. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2018.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schultz J, Joish V. Costs associated with changes in antidepressant treatment in a managed care population with major depressive disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(12):1604-11. doi:10.1176/ps.2009.60.12.1604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Khandker RK, Kruzikas DT, McLaughlin TP. Pharmacy and medical costs associated with switching between venlafaxine and SSRI antidepressant therapy for the treatment of major depressive disorder. J Manag Care Pharm. 2008;14(5):426-41. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2008.14.5.426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fiest KM, Jette N, Quan H, et al. Systematic review and assessment of validated case definitions for depression in administrative data. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:289. doi:10.1186/s12888-014-0289-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Olfson M, Amos TB, Benson C, McRae J, Marcus SC. Prospective service use and health care costs of medicaid beneficiaries with treatment-resistant depression. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2018;24(3):226-36. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2018.24.3.226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]