Abstract

BACKGROUND:

New guidelines for the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) suggest that morbidity and mortality could be reduced if antiretroviral therapy (ART) was initiated immediately after diagnosis, regardless of CD4 cell count.

OBJECTIVE:

To assess real-world time to ART initiation and describe medical, pharmacy, and total health care costs in the 6-, 12-, 24-, and 36-month periods after HIV diagnosis based on time to ART initiation among Medicaid-covered patients.

METHODS:

Multistate Medicaid data (January 2012-March 2017) was used to identify adults with HIV-1 initiating ART ≤ 360 days of initial HIV-1 diagnosis. People living with HIV (PLWH) were sorted into mutually exclusive cohorts based on time from diagnosis to ART initiation (≤ 14 days, > 14 to ≤ 60 days, > 60 to ≤ 180 days, and > 180 to ≤ 360 days). ART regimen had to include a protease inhibitor, an integrase strand transfer inhibitor, or a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, with ≥ 2 nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Medical, pharmacy, and total health care costs in the 6, 12, 24, and 36 months following HIV diagnosis were stratified by timeliness of ART initiation.

RESULTS:

Of 974 patients, 347 (35.6%) initiated ART > 360 days after diagnosis and were excluded. Among the remaining 627 eligible patients, mean age was 39.9 years, 42.7% were female, and 53.9% were black. Among them, 128 (20.4%) were treated ≤ 14 days, 228 (36.4%) between > 14 and ≤ 60 days, 163 (26.0%) between > 60 and ≤ 180 days, and 108 (17.2%) between > 180 and ≤ 360 days. Among patients treated ≤ 180 days, 4.6% had ≥ 1 opportunistic infection in the 6-month period before ART initiation; this proportion reached 5.6% for patients treated >180 and ≤ 360 days. Over the 6-, 12-, 24-, and 36-month periods after diagnosis, per-patient-per-month (PPPM) medical costs were lower for patients who initiated ART ≤ 14 days than for those who initiated > 180 and ≤ 360 days after diagnosis (6 months: $1,611 [≤ 14 days] vs. $3,008 [> 180 and ≤ 360 days]; 12 months: $1,188 vs. $2,110; 24 months: $754 vs. $1,368; 36 months: $651 vs. $1,196). Over the same periods, medical costs generally accounted for > 50% of total health care costs for patients who initiated ART between > 60 and ≤ 180 days and > 180 and ≤ 360 days and for 30%-40% of total health care costs for patients treated ≤ 14 days and between > 14 and ≤ 60 days. Total PPPM health care costs increased with delay of ART initiation in the 36-month period after diagnosis ($2,058 [treated ≤ 14 days] vs. $2,310 [treated between > 180 and ≤ 360 days]).

CONCLUSIONS:

In this study from 2012 to 2017 of Medicaid PLWH treated with ART, 20.4% initiated ART ≤14 days of HIV diagnosis. Patients with delayed ART initiation accumulated more total health care costs in the 36-month period after HIV diagnosis than those initiated within 14 days, highlighting the long-term benefit of rapid ART initiation. An important opportunity remains to engage PLWH in care more rapidly.

What is already known about this subject

With the success of highly active antiretroviral therapy (ART) in decreasing mortality and morbidity, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is now a manageable chronic condition.

Guidelines for the treatment of HIV were updated following results from 2 landmark clinical trials suggesting that morbidity and mortality could be further reduced if ART was initiated early after diagnosis.

When ART should be started before HIV drug resistance results are available (e.g., for a patient with acute HIV or when rapid initiation is warranted), the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services guidelines recommend using regimens that include pharmacologically boosted darunavir (with tenofovir alafenamide and emtricitabine) or dolutegravir (with tenofovir alafenamide and emtricitabine).

What this study adds

In this observational study of a more vulnerable Medicaid population from 2012 to 2017, rapid initiation of ART was relatively infrequent: 20.4% of ART-treated, Medicaid-covered patients initiated ART within 14 days of HIV-1 diagnosis.

Patients with delayed ART initiation accumulated more medical costs than those with rapid initiation in the 6, 12, 24, and 36 months following initial HIV diagnosis.

Patients accumulated more total health care costs in the 36 months after diagnosis, highlighting the potential long-term economic benefits of rapid ART initiation.

In the United States, the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation estimates that 55 million individuals had Medicaid health care coverage in 2013. Among Medicaid enrollees, 284,500 were living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV),1 making Medicaid the insurance provider for 25% of all individuals living with HIV in the United States. In 2013, people living with HIV (PLWH) covered by Medicaid received annual insurance payments of $23,500 U.S. dollars (USD),1 representing approximately 7 times the average annual insurance payment per Medicaid adult beneficiary.2 Because rapid antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation has been shown to reduce HIV-associated morbidity and mortality,3 implementation of this strategy could contribute to reducing Medicaid spending on HIV and improve overall patient health.

Although HIV cannot be cured, appropriate use of ART can prevent HIV replication and disease progression and make it a manageable chronic condition.4,5 However, factors such as poor ART adherence and acquired ART resistance may lead to virologic failure.6-9 Patients on ART who do not achieve or maintain virologic suppression may develop ART resistance requiring a change to second-line ART and limiting future ART options.10

Before 2012, most HIV treatment guidelines suggested that ART should be initiated only when CD4 counts were below a certain threshold, ranging from 200 to 850 cells/μL.11,12 In 2015, the Strategic Timing of AntiRetroviral Treatment (START) and TEMPRANO trials showed that early ART initiation leads to reductions in morbidity and mortality.11,13 HIV treatment guidelines were updated to recommend ART initiation following HIV diagnosis for all patients who are willing to start ART, regardless of CD4 count.14,15 Subsequent studies, 2 of which were conducted in the United States,16,17 investigated the potential benefits of initiating ART on the same day as HIV testing or shortly after.16-24 These invariably found rapid ART to be associated with improved clinical outcomes, improved retention in care, or both.16-23

Despite this evidence, current practice guidelines in the United States only recommend rapid initiation in certain clinical scenarios, and only specific ART regimens are recommended for this purpose.14 The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) recommends that pharmacologically boosted darunavir with tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) and emtricitabine or dolutegravir with TAF and emtricitabine be used when ART must be started before HIV drug resistance results are available (e.g., for a patient with acute HIV or when rapid ART initiation is warranted).14 Despite changes in treatment recommendations, only 50% of HIV-positive patients in the U.S. who are linked to care are on an ART.25

Reducing barriers to rapid initiation, such as time waiting for test results and counseling,22 could eventually make rapid initiation the standard of care for PLWH. This could potentially reduce Medicaid spending related to HIV. Therefore, this study sought to assess real-world time to ART initiation among Medicaid-covered patients and to describe medical, pharmacy, and total health care costs during the 6-, 12-, 24-, and 36-month periods after HIV diagnosis based on time to ART initiation.

Methods

Data Sources

Medicaid databases from 6 states (Iowa [1998 Q1-2017 Q1], Kansas [2001 Q1-2017 Q1], Missouri [1997 Q1-2017 Q1], Mississippi [2006 Q1-2017 Q1], New Jersey [1997 Q1-2014 Q1], and Wisconsin [2004 Q1-2013 Q4]) were available for use in this study. Medicaid databases contain information on medical claims (e.g., type of service; service unit; date; International Classification of Diseases, Ninth/Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM/ICD-10-CM]; Current Procedural Terminology codes; physician specialty; and type of provider); prescription drug claims (e.g., days supplied, service date, and National Drug Codes); and eligibility (e.g., age, gender, enrollment start/end dates, and date/year of death). Additionally, because Medicaid covers 25% of all individuals with HIV in the United States, describing the relationship between time to ART initiation and Medicaid costs is of particular interest and could help identify ways of reducing total health care costs for HIV patients. All data collected were deidentified in compliance with the patient confidentiality requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.26 As this was a retrospective analysis of existing claims data and no patient-identifiable information was included in the claims dataset available for the analysis, institutional review board approval was not required.

Study Design

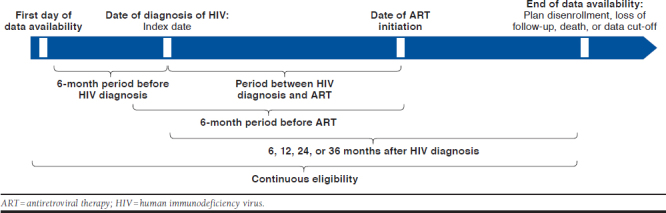

A retrospective longitudinal study design was used to analyze PLWH between January 2012 and March 2017 (Appendix, available in online article). The index date was defined as the date of the first HIV-1 diagnosis (ICD-9-CM: 042, V08, and 795.71; ICD-10-CM: B20, R75, and Z21) during the study period. Time to ART regimen initiation was evaluated ≤ 360 days post-index. An ART regimen was defined as having a claim for a protease inhibitor (PI), an integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI), or a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), with ≥ 2 different nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) ≤ 14 days of each other, to include patients on multiple-tablet regimens (MTR).27,28 Clinical characteristics were evaluated during the 6-month period before ART initiation to identify their relationship with time to ART initiation. Among patients with ≥ 36 months of continuous insurance eligibility after HIV diagnosis, medical, pharmacy, and total health care costs were evaluated during fixed time periods after HIV diagnosis (i.e., post-index at 6, 12, 24, and 36 months) to evaluate trends over time.

Patient Selection

Inclusion Criteria.

To be included in the study, patients had to initiate an antiretroviral in 2012 or later as part of an ART regimen, and the first antiretroviral had to be initiated in the first 360 days following the first HIV diagnosis. In addition, included patients had to be aged ≥ 18 years old, have ≥ 6 months of continuous insurance eligibility pre-index to ensure that the very first HIV diagnosis is captured (i.e., the complete period of Medicaid eligibility was used to identify the first observed HIV diagnosis and a minimum of 6 months of eligibility before that first diagnosis was required), and have no claim for an antiretroviral (other than pre-exposure prophylaxis) at any time before the first HIV diagnosis. Of note, eligible patients with hepatitis B, a virus that can be treated using antiretrovirals also used to treat HIV, were not excluded. Patients were excluded if their first ART regimen following the first HIV diagnosis was nonstandard (i.e., not a PI-, INSTI-, or NNRTI-based regimen).

Exclusion Criteria.

Patients diagnosed with HIV-2 (ICD-9-CM: 079.53; ICD-10-CM: B97.35) at any time and patients whose first HIV diagnosis was recorded during an inpatient stay that lasted ≥ 10 days were excluded. The latter criterion was added to account for services received in an inpatient setting that may have been unrecorded. As such, patients may have initiated an ART regimen during a long stay, but that information could be missing from the data.

Cohort Definition.

Eligible patients were classified into mutually exclusive cohorts based on time of ART initiation after HIV diagnosis (treated ≤ 14 days, > 14 to ≤ 60 days, > 60 to ≤ 180 days, and > 180 to ≤ 360 days). To be included in each post-index period analysis, patients were required to have ≥ 36 months of continuous Medicaid coverage post-index.

Outcome Measures and Statistical Analysis

Time to ART initiation was evaluated with descriptive statistics of the proportions of patients on ART at each time point. Demographic characteristics were assessed at the time of the first HIV diagnosis and included age, gender, race, state, region, type of insurance eligibility (i.e., capitated or fee-for-service coverage, and Medicaid/Medicare dual coverage), and location where patients received their first HIV diagnosis. Clinical characteristics were assessed during the 6-month pre-ART initiation period and included diagnosis of opportunistic infections, most commonly ordered laboratory tests and procedures, and presence of mental and behavioral disorders affecting ≥ 10% of patients (i.e., anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, and substance-related and addictive disorders). This period was chosen to assess the relationship between clinical characteristics and timeliness of ART initiation and to have similar observation periods for all cohorts. The type of ART regimen initiated (i.e, PI-, INSTI-, or NNRTI-based; single-tablet regimen [STR] or MTR) was assessed at the time of ART initiation.

All-cause accumulated and per-patient-per-month (PPPM) medical, pharmacy, and total health care costs were evaluated during the 6-, 12-, 24- and 36-month periods after HIV diagnosis among patients with ≥ 36 months of continuous insurance eligibility after HIV diagnosis. Total health care costs included amounts paid by Medicaid for pharmacy and medical services; the latter included emergency room visits, inpatient stays, outpatient visits, and other services (including, but not limited to, mental health institute admissions, long-term care admissions, and home care). All costs were inflated to 2017 USD using the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index.29

Descriptive statistics were used to report demographics, clinical characteristics, as well as medical, pharmacy, and total health care costs. Means, standard deviations (SDs), medians, and interquartile ranges (IQRs) were reported for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages were reported for categorical variables. For demographic and clinical characteristics, statistical significance between cohorts was assessed using the chi-square test for categorical variables or the t-test for continuous variables. A 5% threshold was used to establish statistical significance.

Results

Timeliness of ART Initiation and Type of ART Regimen Initiated

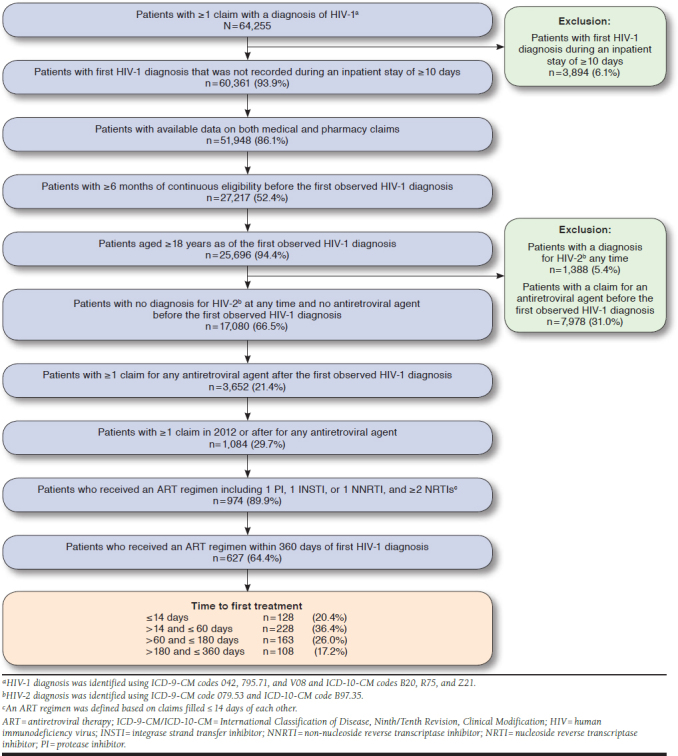

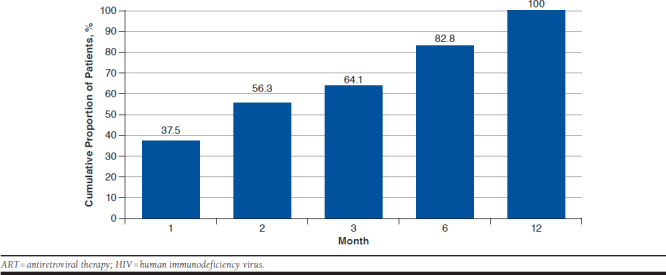

A total of 64,255 patients had ≥ 1 claim with an HIV diagnosis (Figure 1). Of 17,080 adult patients with an HIV diagnosis meeting all inclusion/exclusion criteria unrelated to treatment after diagnosis, 3,652 (21.4%) had ≥ 1 claim for any antiretroviral agent after HIV diagnosis, and 627 (2.4%) were included in the analysis based on the remaining inclusion/exclusion criteria shown in Figure 1. Of note, 347 of 974 patients (35.6%) initiated an ART > 360 days after their first HIV diagnosis and were excluded from the study. Among the remaining 627 patients treated ≤ 360 days, at 1, 3, and 6 months after HIV diagnosis, 37.5%, 64.1%, and 82.8% of included patients had initiated an ART regimen, respectively (Figure 2). A total of 128 (20.4%) were treated ≤ 14 days of diagnosis, 228 (36.4%) between > 14 and ≤ 60 days, 163 (26.0%) between > 60 and ≤ 180 days, and 108 (17.2%) between > 180 and ≤ 360 days. The average time to ART initiation was 88.8 days (SD = 94.8; median = 46.0; IQR = 19.0-140.0).

FIGURE 1.

Identification of the Study Population

FIGURE 2.

Cumulative Proportion of Patients Initiated on ART Since First HIV Diagnosis

Among these 627 patients, 24.1%, 34.1%, and 41.8% were initiated on a PI-, INSTI-, or NNRTI-based regimen, respectively (Table 1). There were no statistically significant differences between cohorts in the proportion of patients who initiated each regimen. Darunavir (9.6%) and atazanavir (8.8%) were the most commonly used PIs. Elvitegravir (16.9%) and dolutegravir (10.2%) were the most commonly used INSTIs, followed by raltegravir (7.0%). Efavirenz (26.5%) and rilpivirine (13.6%) were the most commonly used NNRTIs. Overall, ≥ 50% of patients were initiated on an STR, with the highest proportion (63.3%) observed in patients treated ≤ 14 days.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Timeliness of Receipt of ART | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All N = 627 | ≤ 14 Days n = 128 | > 14 and ≤ 60 Days n = 228 | > 60 and ≤ 180 Days n = 163 | > 180 and ≤ 360 Days n = 108 | |

| Time to treatment (days), mean ± SD | 88.8 ± 94.8 | 5.3 ± 5.2 | 32.8 ± 12.5a | 115.5 ± 36.0a | 265.8 ± 49.8a |

| Age at HIV diagnosis (years), mean ± SD | 39.9 ± 12.3 | 40.5 ± 11.6 | 38.9 ± 12.9 | 40.7 ± 12.4 | 39.7 ± 11.5 |

| Female, % | 42.7 | 44.5 | 42.5 | 41.7 | 42.6 |

| Race, % | |||||

| White | 25.4 | 25.8 | 27.6 | 17.8 | 31.5 |

| Black | 53.9 | 54.7 | 50.9 | 63.2 | 45.4 |

| Otherb | 20.7 | 19.5 | 21.5 | 19.0 | 23.1 |

| State, % | |||||

| Iowa | 16.1 | 10.9 | 20.2a | 13.5 | 17.6 |

| Kansas | 1.8 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 3.7 | 0.9 |

| Mississippi | 25.0 | 29.7 | 23.2 | 20.9 | 29.6 |

| Missouri | 27.0 | 30.5 | 26.8 | 28.2 | 21.3 |

| New Jersey | 20.9 | 17.2 | 17.5 | 27.6a | 22.2 |

| Wisconsin | 9.3 | 10.9 | 11.0 | 6.1 | 8.3 |

| Region characteristics, % | |||||

| Urban | 53.9 | 44.5 | 53.5 | 57.1a | 61.1a |

| Suburban | 30.8 | 39.1 | 28.5a | 30.7 | 25.9a |

| Rural | 15.3 | 16.4 | 18.0 | 12.3 | 13.0 |

| Insurance eligibility, % | |||||

| Capitated/fee-for-service coverage | |||||

| Capitated only | 26.5 | 25.0 | 25.9 | 26.4 | 29.6 |

| Fee-for-service only | 44.7 | 46.9 | 43.4 | 41.7 | 49.1 |

| Combination of capitated and fee-for-service | 28.9 | 28.1 | 30.7 | 31.9 | 21.3 |

| Dual Medicaid/Medicare coverage | 17.1 | 17.2 | 16.7 | 18.4 | 15.7 |

| Patients who initiated a single tablet regimen, % | 58.5 | 63.3 | 57.5 | 57.7 | 56.5 |

| Patients who initiated a multiple tablet regimen, % | 41.5 | 36.7 | 42.5 | 42.3 | 43.5 |

| ART regimen received at the index date, % | |||||

| PI-based regimen | 24.1 | 21.1 | 24.1 | 25.8 | 25.0 |

| Darunavir-based regimen | 9.6 | 6.3 | 10.1 | 11.0 | 10.2 |

| Atazanavir-based regimen | 8.8 | 7.0 | 8.8 | 9.8 | 9.3 |

| Lopinavir-based regimen | 4.9 | 7.0 | 4.4 | 4.3 | 4.6 |

| Other PI-based regimenc | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.9 |

| INSTI-based regimen | 34.1 | 30.5 | 36.0 | 32.5 | 37.0 |

| Elvitegravir-based regimen | 16.9 | 15.6 | 17.1 | 16.6 | 18.5 |

| Dolutegravir-based regimen | 10.2 | 7.8 | 12.3 | 9.2 | 10.2 |

| Raltegravir-based regimen | 7.0 | 7.0 | 6.6 | 6.7 | 8.3 |

| ART regimen received at the index date, % | |||||

| NNRTI-based regimen | 41.8 | 48.4 | 39.9 | 41.7 | 38.0 |

| Efavirenz-based regimen | 26.5 | 32.8 | 25.0 | 25.8 | 23.1 |

| Rilpivirine-based regimen | 13.6 | 14.8 | 12.7 | 13.5 | 13.9 |

| Other NNRTI-based regimend | 1.8 | 0.8 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 0.9 |

| Patients with ≥ 1 diagnosis of an opportunistic infectione in the 6-month period before ART, % | 4.8 | 4.7 | 4.8 | 4.3 | 5.6 |

| Location of first HIV diagnosis, % | |||||

| Emergency room | 3.0 | 2.3 | 3.5 | 3.1 | 2.8 |

| Inpatientf | 11.2 | 7.0 | 13.2 | 11.0 | 12.0 |

| Pathology and laboratory procedures and services received in the 6-month period before ART, % | |||||

| Infectious agent detection by nucleic acid | 57.1 | 43.8 | 64.9a | 69.9a | 37.0 |

| Complete blood count | 50.6 | 42.2 | 56.6a | 54.0a | 42.6 |

| Comprehensive metabolic panel | 49.4 | 36.7 | 57.0a | 58.3a | 35.2 |

| T cells: absolute CD4 and CD8 count | 42.1 | 34.4 | 46.9a | 52.8a | 25.0 |

| Syphilis test, nontreponemal antibody | 37.5 | 28.1 | 44.7a | 50.9a | 13.0a |

| Lipid panel | 31.4 | 25.0 | 37.7a | 36.2a | 18.5 |

| Hepatitis B surface antibody | 26.0 | 20.3 | 38.2a | 24.5 | 9.3a |

| Hepatitis C antibody | 27.0 | 20.3 | 38.6a | 28.2 | 8.3a |

| Infectious agent antigen detection by immunoassay technique | 23.1 | 18.0 | 34.2a | 22.7 | 6.5a |

| Urinalysis | 22.6 | 14.1 | 26.3a | 27.6a | 17.6 |

aStatistically significant difference at the 5% level versus the ≤ 14 days cohort.

bIncludes Hispanic patients and patients for whom race was unknown.

cIncludes fosamprenavir- and nelfinavir-based regimens.

dIncludes etravirine- and nevirapine-based regimens.

eThe opportunistic infections considered were pneumocystis pneumonia, toxoplasma gondii encephalitis, mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, disseminated mycobacterium avium complex disease, histoplasma capsulatum infection, coccidiodomycosis, cryptococcosis, and cytomegalovirus disease.

fThe first HIV diagnosis was recorded during an inpatient stay that lasted ≤10 days because patients whose first observed HIV diagnosis was recorded during an inpatient stay that lasted > 10 days were excluded.

ART = antiretroviral therapy; CD = cluster of differentiation; HIV=human immunodeficiency virus; INSTI = integrase strand transfer inhibitors; NNRTI = non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors; PI=protease inhibitor; SD = standard deviation.

Demographic Characteristics at the First HIV Diagnosis

Age, gender, race, and insurance eligibility were similar across all cohorts; no statistically significant differences were found between patients treated ≤ 14 days of diagnosis and other cohorts (Table 1). Mean age was 39.9 (SD = 12.3) years, and 42.7% of eligible patients were female. The proportion of patients residing in urban areas was 44.5%, 53.5%, 57.1%, and 61.1% for patients treated ≤ 14 days, > 14 and ≤ 60 days, > 60 and ≤ 180 days, and > 180 and ≤ 360 days, respectively, with statistically significant differences found between patients treated ≤ 14 days and those treated between > 60 and ≤ 180 days and > 180 and ≤ 360 days.

Clinical Characteristics During the 6-Month Pre-ART Period

During the 6-month period before ART initiation, 4.6% and 5.6% of patients treated ≤ 180 days and between > 180 and ≤ 360 days had ≥ 1 diagnosis of opportunistic infection within that time period, respectively (Table 1). During the same period, 43.8% of patients treated ≤ 14 days had a procedure to detect an infection (such as HIV or viral hepatitis) by RNA or DNA sequencing; 64.9%, 69.9%, and 37.0% of patients treated between > 14 and ≤ 60, > 60 and ≤ 180, and > 180 and ≤ 360 days had such procedure, respectively. Proportions of similar magnitude were observed for other tests and procedures, such as comprehensive metabolic panels, syphilis tests, and CD4 and CD8 T-cell counts.

The proportion of patients with anxiety disorders was generally higher with delay of ART initiation (4.7%, 9.6%, 14.7%, and 13.0% for patients treated ≤ 14 days, > 14 and ≤ 60 days, > 60 and ≤ 180 days, and > 180 and ≤ 360 days, respectively), with statistically significant differences found between those treated ≤ 14 days and those treated between > 60 and < 180 days and > 180 and ≤ 360 days. The proportion of patients with depressive disorders was similar across all cohorts: 12.5%, 16.7%, 17.2%, and 17.6% for patients treated ≤ 14 days, > 14 and ≤ 60 days, > 60 and ≤ 180 days, and > 180 and ≤ 360 days, respectively. The proportion of patients with substance-related and addictive disorders was generally higher with delay of ART initiation (11.7%, 15.8%, 25.2%, and 19.4% for patients treated ≤ 14 days, > 14 and ≤ 60 days, > 60 and ≤ 180 days, and > 180 and ≤ 360, respectively), with statistically significant differences found between patients treated ≤ 14 days and between > 60 and ≤ 180 days only.

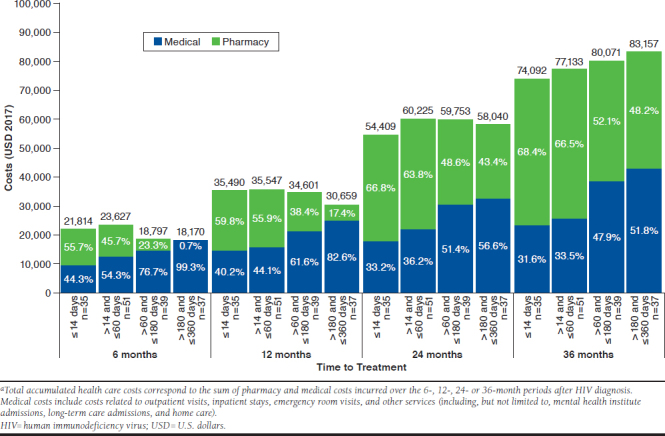

Accumulated Medical Costs After HIV Diagnosis

During the 6- and 12-month periods after HIV diagnosis, accumulated medical costs were generally higher with delay of ART initiation. In the 6-month period, medical costs were $9,665, $12,818, $14,422, and $18,048 for patients treated ≤ 14 days, > 14 and ≤ 60 days, > 60 and ≤ 180 days, and > 180 and ≤ 360 days, respectively. In the 12-month period, medical costs ranged from $14,256 for patients treated ≤ 14 days to $25,317 for those treated between > 180 and ≤ 360 days.

Increasing the observation period to 24 or 36 months after HIV diagnosis yielded similar results. Medical costs ranged from $18,086 to $32,841 for patients treated ≤ 14 days and between > 180 and ≤ 360 days, respectively, in the 24-month period. During the 36-month period, the same costs ranged from $23,447 to $43,067 for the first and last cohorts, respectively.

Lower medical costs for patients who initiated treatment ≤ 14 days and between > 14 and ≤ 60 days were driven by generally lower combined costs for inpatient stays, emergency room visits, and other services (6-month period: $8,191 [≤ 14 days], $10,822 [> 14 and ≤ 60 days], $12,427 [> 60 and ≤ 180 days], and $15,062 [> 180 and ≤ 360 days]; 36-month period: $16,982 [≤ 14 days], $16,059 [> 14 and ≤ 60 days], $25,410 [> 60 and ≤ 180 days], and $26,556 [> 180 and ≤ 360 days]).

Accumulated Total Health Care Costs After HIV Diagnosis

During the first 6-month period after HIV diagnosis, total health care costs were lower with increasing delay of ART initiation (Figure 3). Similar patterns were found over the 12- and 24-month periods after HIV diagnosis. Increasing the observation period to 36 months post-HIV diagnosis resulted in smaller total health care costs for patients who initiated treatment earlier. The higher costs for earlier initiators were mostly driven by higher pharmacy costs. However, these were offset by reduced medical costs over the 36-month period after HIV diagnosis.

FIGURE 3.

Total Accumulated Health Care Costs in the 6, 12, 24, and 36 Months After HIV Diagnosisa

In the 12-, 24-, and 36-month periods, medical costs accounted for approximately 35% of total health care costs for patients initiating an ART ≤ 14 days of diagnosis, and for 36% to 83% of total health care costs for those who initiated between > 14 and ≤ 360 days.

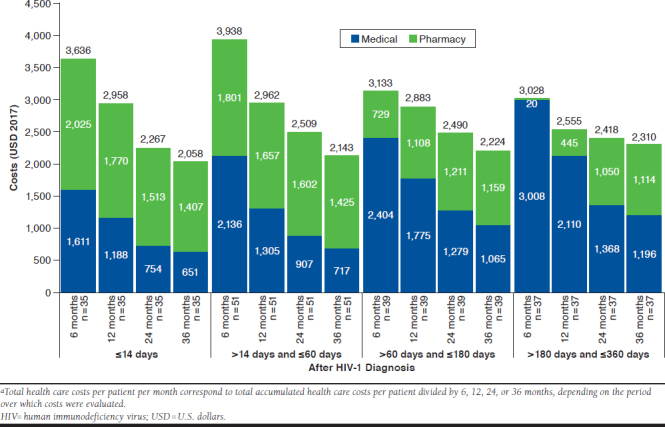

Monthly Total Health Care Costs After HIV Diagnosis

Patients initiated on an ART ≤ 14 days and between > 14 and ≤ 60 days of their first HIV diagnosis experienced greater reductions in PPPM total health care costs over time than those who initiated later (Figure 4). For patients who received ART ≤ 14 days, total health care costs PPPM fell from $3,636 over the 6-month period to $2,058 over the 36-month period. Similar results were found for patients who initiated ART between > 14 and ≤ 60 days of diagnosis. For the cohort who initiated treatment between > 60 and ≤ 180 days of HIV diagnosis, total health care costs PPPM decreased more modestly over all time periods. Patients who initiated ART between > 180 and ≤ 360 days experienced the least pronounced cost reductions (i.e., $3,028 in the 6-month period vs. $2,310 in the 36-month period).

FIGURE 4.

Total Health Care Costs Per Patient Per Month in the 6, 12, 24, and 36 Months After HIV Diagnosisa

Patients who initiated ART ≤ 14 days and between > 14 and ≤ 60 days of diagnosis experienced reductions in both PPPM medical and PPPM pharmacy costs from 6 to 36 months after HIV diagnosis. Patients who initiated ART between > 60 and ≤ 180 and > 180 and ≤ 360 days experienced increases in pharmacy costs from 6 to 36 months after diagnosis.

In the 6- and 12-month periods, total health care costs PPPM were smaller for the 2 cohorts who initiated treatment later, because of delays in ART initiation resulting in reduced pharmacy-related costs. In the 24- and 36-month periods, patients who initiated treatment ≤ 14 days of diagnosis had lower PPPM total health care costs than those who initiated between > 14 and ≤ 360 days. This result was driven by lower PPPM medical costs that offset higher pharmacy costs over longer time periods. Lower medical costs for the ≤ 14 days cohort compared with other groups were driven by lower combined costs for inpatient stays, emergency room visits, and other services.

Discussion

This study showed that, among Medicaid-covered adult PLWH prescribed ART within 1 year of their HIV diagnosis, 20.4% of patients initiated an ART regimen ≤ 14 days. A significant proportion of patients delayed treatment beyond 6 months, and even more patients delayed treatment beyond 1 year and were excluded from this analysis.

In cases where ART must be started before HIV drug resistance results are available (e.g., for a patient with acute HIV or when rapid initiation of ART is warranted),14 DHHS guidelines recommend initiating boosted darunavir with TAF/emtricitabine or dolutegravir with TAF/emtricitabine. However, most patients included in the present study were initiated on other regimens. More specifically, 48.4% of rapid initiators used NNRTI-based regimens even though this class of agent is more susceptible to drug resistance. However, it cannot be excluded that some patients may have received an NNRTI-based regimen after negative resistance test results were obtained for this drug class. The high proportion of nonconformity to optimal ARTs can be partially explained by the fact that our study period (2012-2017) preceded the publication of new guidance to initiate ART at any given CD4 cell count, though other factors, such as patients’ willingness to pay and the addition/removal of guideline-recommended regimens over time,14 may also play a role. Thus, patients could have received their first ART at a time when the experimental evidence on early ART initiation, such as the results of the START and TEMPRANO trials,12,14 and therapeutic guidance to rapidly initiate patients were more limited.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first real-world evaluation of the relationship between rapid initiation and medical, pharmacy, and total health care costs. Studies that have analyzed the relationship between time to ART initiation and health care resource utilization found mixed results. The START clinical trial, which assigned patients with CD4 + levels > 500 cells/μL to either immediate or deferred ART initiation (i.e., until CD4 + levels fell ≤ 350 cells/μL or patients had clinical events requiring ART), found that over an average follow-up period of 3 years, unscheduled hospitalizations were similar in both groups.11 A study of PLWH in France and the United Kingdom found that among patients who initiated ART ≤ 6 months after diagnosis, those who initiated ART ≥ 30 days after diagnosis had shorter hospital stays (estimated over a 6-month period).30 Conversely, the current study showed that over the 6-, 12-, 24-, and 36-month periods following diagnosis, medical costs were lower for rapid initiators. Furthermore, total health care costs were lower for rapid initiators (treated ≤ 14 days) in the 24- and 36-month periods. This is explained by initially higher pharmacy costs that were offset by lower medical costs over longer time periods for rapid initiators.

Prior evidence suggests that higher CD4 cell count, drug use, and psychological distress are associated with delayed ART initiation or poor adherence.14,31-33 Results from our study show that patients with delayed ART had higher levels of anxiety and substance-related and addictive disorders than those who initiated treatment ≤ 14 days. Although DHHS and other treatment guidelines advocate for treatment of all individuals regardless of CD4 + cell count, they also acknowledge the importance of adherence to ART as a lifelong treatment. Our findings represent an opportunity to educate health care providers that mental illness, substance use, and some psychosocial challenges are not reasons to withhold ART. However, it is recommended to delay ART initiation until the patient demonstrates willingness to initiate ART.14 Because treatment nonadherence is more likely in patients with mental health issues and may be associated with drug-resistance mutations,34-37 clinicians should recognize potential interventions that can improve adherence and prevent drug resistance from occurring. DHHS guidelines recommend avoiding efavirenz- and rilpivirine-based regimens for patients with psychiatric illnesses because they can exacerbate symptoms and lead to increased neuropsychological adverse events.14 Prior studies have found that patients initiated on STRs were 80% more adherent than those initiated on MTRs,38 suggesting that the availability of an STR regimen might help guide the choice of ART regimen when rapid initiation is warranted. Additionally, patients with historically poor adherence or patients who are likely to be less engaged in care may be more at risk to develop resistance and should be treated with a boosted PI, dolutegravir and TAF/emtricitabine, or bictegravir, because these agents have a higher genetic barrier to resistance (although data on bictegravir’s efficacy in this population is not yet available).14

Limitations

This study has some limitations to consider. As with all claims data sources, Medicaid data may contain inaccuracies or omissions in diagnoses, billing, and other variables, although this is not expected to differ between cohorts. The Medicaid data used in this study came from 6 states and may not be generalizable to the overall Medicaid population, other states, non-Medicaid patients, or noninsured patients. Furthermore, Medicaid PLWH may be different and could receive different types of ART compared with non-Medicaid PLWH. In addition, antiretroviral claims were assumed to indicate their use. However, patients might not have adhered to the ART regimen as prescribed. Although patients were excluded if they had an antiretroviral claim other than pre-exposure prophylaxis before the first HIV diagnosis, some patients may have received an antiretroviral from another source, such as the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program,39 which is not recorded in Medicaid data. Of note, 347 of 974 (35.6%) patients were excluded from the study because they initiated an ART regimen > 360 days after the first HIV diagnosis; therefore, the proportion of patients on rapid ART initiation (i.e., treated ≤ 14 days) has been overestimated.

Although DHHS guidelines recommend performing several laboratory tests before ART initiation (e.g., screening for hepatitis B and hepatitis C, CD4 + cell count, and urinalysis),14 patients were not required to have received tests to be included in this study. Cost analyses were performed over 6, 12, 24, and 36 months following the first HIV diagnosis using an intent-to-treat approach. In the present study, many patients received ART before the DHHS recommendation to initiate ART immediately in all PLWH regardless of CD4 cell counts. Because of this, the contemporary proportion of patients with rapid initiation may be higher than that reported here. Moreover, cost results should be interpreted as reflecting the payer’s perspective. Amounts paid by other insurers, such as Medicare for patients with dual Medicare/Medicaid eligibility, were not captured using Medicaid data.

Finally, given the descriptive nature of the study, no adjustments were made for changes in ART regimen in the study or for differences in characteristics before and after ART initiation within each cohort. Additionally, no adjustments were made for differences in characteristics across cohorts.

Conclusions

This study showed that among ART-treated adult patients diagnosed with HIV and insured by Medicaid, approximately two thirds were prescribed ART within 1 year of diagnosis; among them, only 1 in 5 initiated ART rapidly (≤ 14 days). Therefore, a clinical and economic opportunity remains to treat and initiate patients on ART more rapidly. Accumulated medical costs were considerably lower for patients who initiated ART rapidly versus those who delayed ART. This was observed as early as 6 months after diagnosis and continued up to 36 months after diagnosis. The lower total accumulated health care costs (medical and pharmacy) for rapid initiators in the 24- and 36-month periods after HIV diagnosis highlight the long-term benefits of rapid ART initiation. Finally, the decrease in medical costs may suggest an important clinical benefit of rapid initiation.

APPENDIX. Study Design Scheme

REFERENCES

- 1.Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation . Medicaid enrollment and spending on HIV/AIDS. Available at: https://www.kff.org/hivaids/state-indicator/enrollment-spending-on-hiv/. Accessed October 22, 2019.

- 2.Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation . Medicaid spending per enrollee (full or partial benefit). Available at: https://www.kff.org/medicaid/state-indicator/medicaid-spending-per-enrollee/. Accessed October 22, 2019.

- 3.Fischl MA, Richman DD, Grieco MH, et al. The efficacy of azidothymidine (AZT) in the treatment of patients with AIDS and AIDS-related complex: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. N Engl J Med. 1987;317(4):185-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization . HIV/AIDS: antiretroviral therapy. Available at: http://www.who.int/hiv/topics/treatment/art/en/. July 2013. Accessed October 22, 2019.

- 5.Deeks SG, Lewin SR, Havlir DV.. The end of AIDS: HIV infection as a chronic disease. Lancet. 2013;382(9903):1525-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luber AD. Genetic barriers to resistance and impact on clinical response. Med Gen Med. 2005;7(3):69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedland GH, Williams A.. Attaining higher goals in HIV treatment: the central importance of adherence. AIDS. 1999;13(Suppl 1):S61-72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carrieri MP, Chesney MA, Spire B, et al. Failure to maintain adherence to HAART in a cohort of French HIV-positive injecting drug users. Int J Behav Med. 2003;10(1):1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Drug resistance. January 28, 2019. Available at: https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/understanding-hiv-aids/fact-sheets/21/56/drug-resistance. Accessed October 22, 2019.

- 10.Art-Linc of IeDEA Study Group, Keiser O, Tweya H, et al. Switching to second-line antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited settings: comparison of programmes with and without viral load monitoring. AIDS. 2009;23(14):1867-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Insight Start Study Group . Initiation of antiretroviral therapy in early asymptomatic HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(9):795-807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Cock KM, El-Sadr WM.. When to start ART in Africa—an urgent research priority. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(10):886-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.TEMPRANO ANRS 12136 Study Group, Danel C, Moh R, et al. A trial of early antiretrovirals and isoniazid preventive therapy in Africa. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(9):808-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents living with HIV. July 10, 2019. Available at: https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/html/1/adult-and-adolescent-arv/0. Accessed October 22, 2019.

- 15.World Health Organization . Guidelines for managing advanced HIV disease and rapid initiation of antiretroviral therapy. 2017. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/255884/9789241550062-eng.pdf; jsessionid=0C534026F94C6F891A3839E76BB806AB?sequence=1. Accessed October 22, 2019. [PubMed]

- 16.Hoenigl M, Chaillon A, Moore DJ, et al. Rapid HIV viral load suppression in those initiating antiretroviral therapy at first visit after HIV diagnosis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:32947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pilcher CD, Ospina-Norvell C, Dasgupta A, et al. The effect of same-day observed initiation of antiretroviral therapy on HIV viral load and treatment outcomes in a U.S. public health setting. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;74(1):44-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amanyire G, Semitala FC, Namusobya J, et al. Effects of a multicomponent intervention to streamline initiation of antiretroviral therapy in Africa: a stepped-wedge cluster-randomised trial. Lancet HIV. 2016;3(11):e539-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ford N, Migone C, Calmy A, et al. Benefits and risks of rapid initiation of antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2018;32(1):17-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koenig SP, Dorvil N, Devieux JG, et al. Same-day HIV testing with initiation of antiretroviral therapy versus standard care for persons living with HIV: a randomized unblinded trial. PLoS Med. 2017;14(7):e1002357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Labhardt ND, Ringera I, Lejone TI, et al. Effect of offering same-day ART vs usual health facility referral during home-based HIV testing on linkage to care and viral suppression among adults with HIV in Lesotho: the CASCADE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319(11):1103-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosen S, Maskew M, Fox MP, et al. Initiating antiretroviral therapy for HIV at a patient’s first clinic visit: the RapIT randomized controlled trial. PLoS Med. 2016;13(5):e1002015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Girometti N, Nwokolo N, McOwan A, Whitlock G.. Outcomes of acutely HIV-1-infected individuals following rapid antiretroviral therapy initiation. Antivir Ther. 2017;22(1):77-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huhn G, Crofoot G, Gathe J Jr, et al. Darunavir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide (D/C/F/TAF) in a test-and-treat model of care for HIV-1 infection: interim analysis of the DIAMOND study. Paper presented at: 22nd International AIDS Conference; July 23-27, 2018; Amsterdam, Netherlands. Available at: http://www.natap.org/2018/IAC/IAC_27.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . HIV in the United States: the stages of care. July 2012. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/research_mmp_stagesofcare.pdf. Accessed October 22, 2019.

- 26.Atchinson BK, Fox DM.. From the field: the politics of the Health Insurance Portability And Accountability Act. Health Affairs. 1997;16(3):146-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosenblatt L, Buikema AR, Seare J, et al. Economic outcomes of firstline regimen switching among stable patients with HIV. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(7):725-34. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2017.16403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tandon N, Mao J, Shprecher A, et al. Compliance with clinical guidelines and adherence to antiretroviral therapy among patients living with HIV. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(1):63-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.U.S. Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics . Consumer Price Index. 2019. Available at: https://www.bls.gov/cpi/tables/supplemental-files/home.htm. Accessed October 22, 2019.

- 30.Deconinck L, Yazdanpanah Y, Gilson R, et al. Time to initiation of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients diagnosed with an opportunistic disease: a cohort study. HIV Medicine. 2015;16(4):219-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nash D, Tymejczyk O, Gadisa T, et al. Factors associated with initiation of antiretroviral therapy in the advanced stages of HIV infection in six Ethiopian HIV clinics, 2012 to 2013. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(1):20637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hsu LC, Truong H-HM, Vittinghoff E, Zhi Q, Scheer S, Schwarcz S.. Trends in early initiation of antiretroviral therapy and characteristics of persons with HIV initiating therapy in San Francisco, 2007-2011. J Infect Dis. 2014;209(9):1310-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Novak R, Hart R, Chmiel J, Brooks J, Buchacz K.. Disparities in initiation of combination antiretroviral treatment and in virologic suppression among patients in the HIV outpatient study, 2000-2013. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;70(1):23-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Langebeek N, Gisolf EH, Reiss P, et al. Predictors and correlates of adherence to combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) for chronic HIV infection: a meta-analysis. BMC Medicine. 2014;12(1):142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harrigan PR, Hogg RS, Dong WWY, et al. Predictors of HIV drug-resistance mutations in a large antiretroviral-naive cohort initiating triple antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Diss. 2005;191(3):339-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Masikini P, Mpondo BCT.. HIV drug resistance mutations following poor adherence in HIV-infected patient: a case report. Clin Case Rep. 2015;3(6):353-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meresse M, March L, Kouanfack C, et al. Patterns of adherence to antiretroviral therapy and HIV drug resistance over time in the Stratall ANRS 12110/ESTHER trial in Cameroon. HIV Medicine. 2014;15(8):478-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clay PG, Nag S, Graham CM, Narayanan S.. Meta-analysis of studies comparing single and multi-tablet fixed dose combination HIV treatment regimens. Medicine. 2015;94(42):e1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Health Resources & Services Administration . About the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program. February 2019. Available at: https://hab.hrsa.gov/about-ryan-white-hivaids-program/about-ryan-white-hivaids-program. Accessed October 22, 2019.