Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Patients with hemophilia A are commonly treated with replacement recombinant factor VIII (rFVIII) products, which can be standard-acting or long-acting. Long-acting products have modifications, offering the potential for reduced dosing frequency while maintaining therapeutic benefit. Extended dosing intervals reduce patient burden and can improve quality of life and adherence.

OBJECTIVE:

To assess real-world data for the use of 6 commonly prescribed standard-acting and long-acting FVIII products in the United States: octocog alfa, BAY 14-2222, BAY 81-8973, rVIII-SingleChain, rFVIIIFc, and polyethylene glycol (PEG)-rFVIII. We summarized annualized bleeding rates (ABRs), dosing frequency, and factor consumption in patients treated with each product, with subgroup analyses for patients with severe disease.

METHODS:

De-identified patient data were collected from 11 hemophilia treatment centers in the United States. Patients treated with octocog alfa, BAY 14-2222, BAY 81-8973, rVIII-SingleChain, rFVIIIFc, or PEG-rFVIII prophylaxis for ≥ 8 weeks at the time of data collection were included in the analysis. Among the 6 treatment groups, matching was attempted for patient age and disease severity where possible.

RESULTS:

Data were obtained for 240 patients, of whom 191 patients had severe disease. Patients receiving long-acting FVIII products were dosed less frequently than those receiving standard-acting FVIII products. The proportion of patients dosed 2 times weekly or less was 65.0%, 70.0%, 72.5%, 25.0%, 40.0%, and 47.5% with rVIII-SingleChain, rFVIIIFc, PEG-rFVIII, octocog alfa, BAY 14-2222, and BAY 81-8973, respectively. Median ABRs ranged from 2.0 to 3.0 (mean 2.6 to 4.4) across the 6 products for all patients and were similar for patients with severe disease (median 2.0 to 3.0 and mean 2.5 to 4.8). The proportion of patients experiencing 0 bleeding episodes ranged from 7.5% to 25.0% for all patients and 12.0% to 28.6% for patients with severe disease. For all patients, median (mean) weekly FVIII product consumption was lowest for rVIII-SingleChain among the 6 products (P = 0.045); 91.9 (91.1) IU per kg per week for rVIII-SingleChain, 108.5 (103.6) for rFVIIIFc, 97.6 (111.0) for PEG-rFVIII, 114.0 (117.5) for octocog alfa, 102.5 (102.6) for BAY 14-2222, and 95.1 (100.7) for BAY 81-8973. Similar differences in weekly consumption among the 6 products were observed for patients with severe disease (P = 0.014).

CONCLUSIONS:

Real-world data demonstrate that long-acting products may be beneficial compared with standard-acting products because of reduced dosing frequency while maintaining effectiveness. The 6 products evaluated showed statistically comparable ABRs and percentage of patients with 0 bleeds for all patients including those with severe disease. rVIII-SingleChain demonstrated lowest mean consumption for all patients, as well as for patients with severe hemophilia A, which may lead to potential savings in health care costs.

What is already known about this subject

Different technologies have been used to modify factor VIII (FVIII) to develop treatment products that extend FVIII half-life, and several standard-acting and long-acting products are available to treat patients with hemophilia A in the United States.

Long-acting products facilitate longer treatment intervals with the potential for reducing patients’ burden.

What this study adds

This real-world analysis study compared 3 standard-acting and 3 long-acting FVIII products that are commonly prescribed in the United States for prophylaxis treatment of patients with hemophilia A.

These analyses demonstrate that long-acting products reduced dosing frequency compared with standard-acting products while maintaining effectiveness.

The long-acting FVIII product rVIII-SingleChain had the lowest mean factor consumption compared with the other 2 long-acting products rFVIIIFc and polyethylene glycol-rFVIII, and the standard-acting products octocog alfa, BAY 14-2222, and BAY 81-8973.

Hemophilia A is an X-linked bleeding disorder caused by a mutation in the gene that encodes coagulation factor VIII (FVIII).1 Patients with hemophilia A account for 80%-85% of the total hemophilia population, with the disorder occurring in approximately 1 in 10,000 births.2 A deficiency of functional FVIII can result in internal bleeding episodes that occur for no obvious reason, termed spontaneous bleeding events, and can cause damage to joints and muscles. The frequency and severity of spontaneous bleeds vary among patients depending on various factors, including clotting factor residual circulation levels, physical activity, and age.3

Replacement FVIII therapy aims to prevent and treat bleeding episodes and is administered either on-demand after experiencing an acute bleed or by scheduled prophylaxis. In the United States, FVIII prophylaxis is given to prevent bleeding and preserve musculoskeletal function and is the standard of care for patients with severe hemophilia (FVIII activity level < 1%), since it is effective in helping to maintain healthy joint function, particularly when initiated in childhood.4-7 However, current prophylactic regimens cannot eliminate the possibility of patients developing joint disease as a single bleed can cause irreversible damage.4,8 Furthermore, the relatively short half-life of FVIII (8-12 hours) in standard-acting products, which are pharmacokinetically similar to endogenous FVIII, necessitates frequent dose administrations. Standardized protocols (Malmö and Utrecht) suggest dosing with these 3 times weekly, placing a significant burden on the patient and caregiver, and poor adherence to these regimens can compromise treatment benefit.2,9

Long-acting products have improved pharmacokinetics that extend the half-life of FVIII and therefore extend dosing intervals. Different technologies have been employed to extend the half-life of currently available treatment products, including single-chain technology, Fc fusion, and polyethylene glycol (PEG) conjugation.10-12

Several recombinant FVIII (rFVIII) products are indicated for treatment of patients with hemophilia A in the United States,13 including the standard-acting products octocog alfa (Advate, Baxalta),14 BAY 14-2222 (Kogenate, Bayer),7 and BAY 81-8973 (Kovaltry, Bayer),4 and the long-acting products rVIII-SingleChain (AFSTYLA, CSL Behring),15,16 rFVIIIFc (Eloctate, Bioverativ),11,17 and PEG-rFVIII (Adynovate, Takeda).10,18

All FVIII products available are considered generally well tolerated and effective; therefore, when considering treatment with different FVIII products, other parameters should also be considered. For example, dosing frequency, factor consumption, and cost-effectiveness of the product.

An analysis from a real-world study evaluating prophylactic use of the long-acting FVIII products rVIII-SingleChain, rFVIIIFc, and PEG-rFVIII in the United States demonstrated that clinical effectiveness was comparable across products, and dosing frequency and factor consumption were lowest for rVIII-SingleChain compared with the other 2 products.19 As an extension to these findings, here we report real-world data for patients with hemophilia A receiving prophylaxis treatment with 3 commonly prescribed standard-acting FVIII products in the United States as well as these 3 long-acting products.

Methods

Data Collection

A retrospective chart review was conducted for patients with hemophilia A in the United States receiving prophylaxis treatment with 1 of 6 FVIII products (octocog alfa, BAY 14-2222, BAY 81-8973, rVIII-SingleChain, rFVIIIFc, and PEG-rFVIII). De-identified data were obtained for 40 patients treated with each product from a total of 11 hemophilia treatment centers across different states (representing 8 of the 10 regions specified in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention hemophilia treatment center directory) for patients with a minimum treatment duration of 8 weeks as of May 2018; data collection was carried out between May and July 2018.

Data collected were related to patient characteristics, including age, weight, sex, severity of hemophilia A, and treatment and clinical outcomes, such as duration on FVIII therapy, dose and dosing frequency of FVIII treatment, and number of bleeds reported over an average period of up to 12 months. Where possible, patient selection considered age and disease severity; physicians could be asked to prioritize charts of pediatric versus adult and/or severe versus nonsevere patients if they were able to, in order to obtain a sample of patients similar in age and severity to ensure that the different patient groups were comparable across products.

In accordance with the prescribing information for each product, patients ≥ 12 years of age were defined as adults/adolescents, and patients < 12 years were defined as pediatric patients.2 Patients with < 1% normal FVIII levels were defined as severe, patients with 1%-5% were defined as moderate, and patients with > 5%-40% were defined as mild.2 To allow comparisons of calculated factor consumption across treatment groups, standardized FVIII dosing (IU per kg per week [IU/kg/week]) was derived from the most recent prescription. Annualized bleeding rate (ABR) was calculated as the number of reported bleeding events (× 12), divided by the number of months in the reporting window; patients with an unknown number of bleeds were not included in this analysis.

Details for this study were submitted to an institutional review board (IntegReview), and the study was determined as exempt for requiring consent under category 4 “Secondary research for which consent is not required.”

Analysis

Data were analyzed and compared across groups for patients receiving the 3 standard-acting and 3 long-acting FVIII products. The primary outcome measures were dose and dosing frequency (taken from the most recent prescription of each product), ABR (calculated by annualizing the number of bleeds based on the duration within which the bleeds occurred), and calculated weekly factor consumption for prophylaxis (reported as IU of product per kg of bodyweight per week). Factor consumption was normalized by multiplying the dose per administration by the number of administrations per week and dividing by the patient’s weight.

Statistical Methods

Differences in the ABR across treatment groups were tested for statistical significance using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) models that included age, weight, severity, and consumption as covariates. Statistical significance of the differences among the products in consumption was tested with ANCOVA model that controlled for age, weight, and severity (severe or nonsevere). Similar tests were conducted for patients with severe disease, excluding the severity variable from the models.

Fisher’s exact test was used to assess if the differences in the percentage of patients with 0 bleeds among the products were statistically significant.

Results

Study Cohort

Data were analyzed for 240 patients treated with each of the standard-acting (octocog alfa [n = 40], BAY 14-2222 [n = 40], or BAY 81-8973 [n = 40]), or long-acting (rVIII-SingleChain [n = 40], rFVIIIFc [n = 40], or PEG-rFVIII [n = 40]) FVIII products. Data for the long-acting products have been published and are included in this analysis for completeness.19 Approximately 91% of patients were ≥ 12 years of age, with a mean age of 31.3 years (Table 1). Weight for patients on rVIII-SingleChain (mean 60.3 kg) was observed to be lower than for other products (range of means 71.9 kg to 82.3 kg). Across treatment groups, the proportion of patients with severe disease ranged from 62.5% (BAY 14-2222) to 87.5% (octocog alfa, rVIII-SingleChain, and PEG-rFVIII; Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Standard-Acting | Long-Acting | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Octocog alfa | BAY 14-2222 | BAY 81-8973 | rVIII-SingleChain | rFVIIIFc | PEG-rFVIII | |

| Number of patients | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 |

| Mean age ± SD, years | 28.2 ± 15.2 | 37.4 ± 14.0 | 31.9 ± 13.5 | 28.7 ± 16.1 | 30.8 ± 15.1 | 30.5 ± 11.3 |

| Age group, n (%) | ||||||

| Adults/adolescents (≥ 12 years) | 34 (85.0) | 40 (100.0) | 37 (92.5) | 35 (87.5) | 35 (87.5) | 38 (95.0) |

| Pediatrics (< 12 years) | 6 (15.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (7.5) | 5 (12.5) | 5 (12.5) | 2 (5.0) |

| Weight ± SD, kg | 71.9 ± 30.5 | 78.3 ± 14.6 | 74.2 ± 22.7 | 60.3 ± 18.0 | 72.3 ± 24.9 | 82.3 ± 28.8 |

| Severity, n (%) | ||||||

| Severe | 35 (87.5) | 25 (62.5) | 28 (70.0) | 35 (87.5) | 33 (82.5) | 35 (87.5) |

| Moderate/mild | 5 (12.5) | 15 (37.5) | 12 (30.0) | 5 (12.5) | 7 (17.5) | 5 (12.5) |

| Mean duration of observation (range), weeks | 52 (52-52) | 52 (52-52) | 52 (52-52) | 43 (16-97) | 52 (52-52) | 52 (52-52) |

PEG = polyethylene glycol; rFVIII = recombinant factor VIII; SD = standard deviation.

Dosing Regimens

Patients receiving long-acting products were dosed less frequently than those receiving standard-acting products (Figure 1). In total, approximately 70% versus 30% of patients were dosed 2 times weekly or less with long-acting products versus standard-acting products. A total of 65.0%, 70.0%, and 72.5% of patients were dosed 2 times weekly or less with rVIII-SingleChain, rFVIIIFc, and PEG-rFVIII, respectively; 25.0%, 40.0%, and 47.5% of patients were dosed 2 times weekly or less with octocog alfa, BAY 14-2222, and BAY 81-8973, respectively. Dosing regimens for patients with severe disease were similar to those observed for the entire cohort of patients, with 70% of patients dosed 2 times weekly or less with long-acting products (Supplementary Figure 1, available in online article).

FIGURE 1.

Frequency of Prophylaxis Dose Administration in All Patients

Bleeding Rates

For all patients, ABRs were comparable between all 6 treatment groups, with a median (mean ± standard deviation [SD]) of 2.0 (2.6 ± 2.8), 2.0 (2.6 ± 2.8), 3.0 (3.7 ± 4.4), 2.0 (2.8 ± 3.1), 3.0 (3.0 ± 2.5), and 3.0 (4.4 ± 4.7) for rVIII-SingleChain, rFVIIIFc, PEG-rFVIII, octocog alfa, BAY 14-2222, and BAY 81-8973, respectively (Table 2). Although no statistically significant difference was observed across the 6 treatment groups, the percentage of patients experiencing 0 bleeding episodes was numerically higher for patients receiving long-acting products (range: 17.5%-25.0%) than those receiving standard-acting products (7.5%-17.5%). Patients with severe hemophilia A had similar bleeding rates to the total population, with a median (mean) ABR ranging from 2.0 (2.5) to 3.0 (4.8), and the proportion of patients experiencing 0 bleeding episodes ranging from 20.0% to 28.6% with long-acting products and from 12.0% to 17.1% with standard-acting products (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Bleeding Rates in Patients Treated with 6 Commonly Used Products

| Standard-Acting | Long-Acting | P Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Octocog alfa | BAY 14-2222 | BAY 81-8973 | rVIII-SingleChain | rFVIIIFc | PEG-rFVIII | ||

| All patients, N | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | |

| ABR | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.8 (3.1) | 3.0 (2.5) | 4.4 (4.7) | 2.6 (2.8) | 2.6 (2.8) | 3.7 (4.4) | 0.165 |

| Median (min, max) | 2.0 (0.0, 18.0) | 3.0 (0.0, 12.0) | 3.0 (0.0, 24.0) | 2.0 (0.0, 12.0) | 2.0 (0.0, 12.0) | 3.0 (0.0, 24.0) | |

| Patients with 0 bleeds, n (%) | 7 (17.5) | 3 (7.5) | 4 (10.0) | 10 (25.0) | 9 (22.5) | 7 (17.5) | 0.231 |

| Patients with severe disease, n | 35 | 25 | 28 | 35 | 33 | 35 | |

| ABR | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.9 (3.3) | 3.4 (3.0) | 4.8 (5.0) | 2.5 (3.0) | 2.8 (3.0) | 3.9 (4.7) | 0.288 |

| Median (min, max) | 2.0 (0.0, 18.0) | 3.0 (0.0, 12.0) | 3.0 (0.0, 24.0) | 2.0 (0.0, 12.0) | 2.0 (0.0, 12.0) | 3.0 (0.0, 24.0) | |

| Patients with 0 bleeds, n (%) | 6 (17.1) | 3 (12.0) | 4 (14.3) | 10 (28.6) | 8 (24.2) | 7 (20.0) | 0.623 |

ABR = annualized bleeding rate; PEG = polyethylene glycol; rFVIII = recombinant factor VIII; SD = standard deviation.

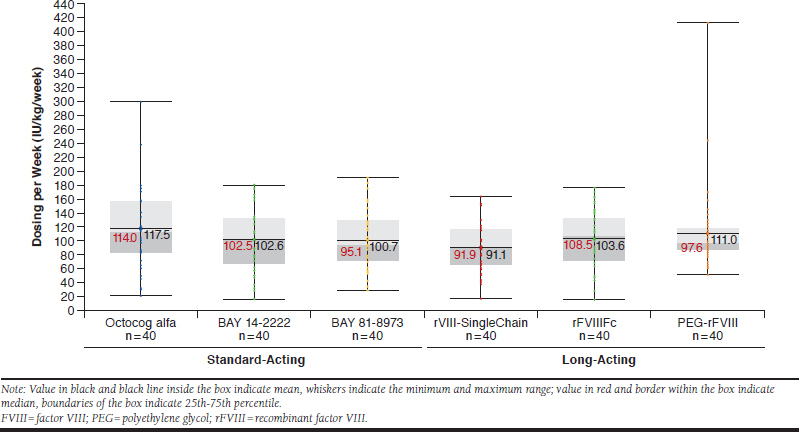

Consumption

Across all treatment groups, the median (mean ± SD) weekly FVIII consumption was lowest for rVIII-SingleChain at 91.9 (91.1 ± 32.8) IU/kg/week compared with the other 5 products and was highest for octocog alfa at 114.0 (117.5 ± 56.1) IU/kg/week (Figure 2). Median (mean ± SD) weekly consumption for all patients with the long-acting products was 91.9 (91.1 ± 32.8) IU/kg/week for rVIII-SingleChain, 108.5 (103.6 ± 41.2) IU/kg/week for rFVIIIFc, and 97.6 (111.0 ± 60.4) IU/kg/week for PEG-rFVIII, and with the standard-acting products was 114.0 (117.5 ± 56.1) IU/kg/week for octocog alfa, 102.5 (102.6 ± 44.6) IU/kg/week for BAY 14-2222, and 95.1 (100.7 ± 44.8) IU/kg/week for BAY 81-8973 (Figure 2). Statistical significance was found for the difference across the 6 treatment groups (P = 0.045).

FIGURE 2.

Weekly Factor Consumption in All Patients Using Standard-Acting or Long-Acting FVIII Products

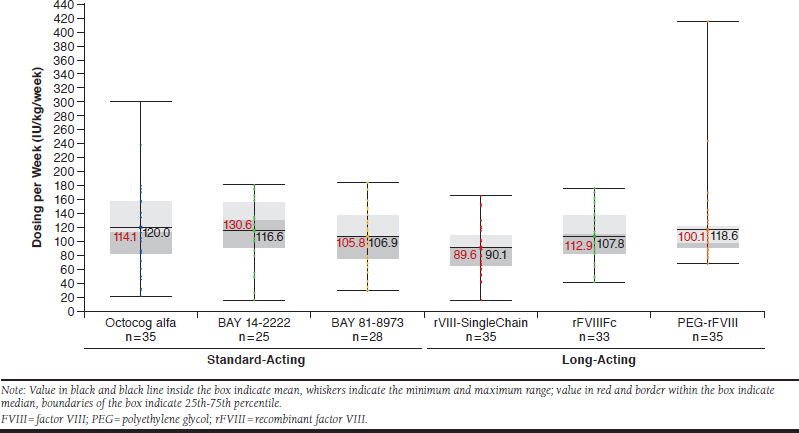

The patterns of differences among the 6 products in weekly FVIII consumption for all patients were similar to those for patients with severe disease. Median (mean ± SD) weekly consumption for patients with severe disease was 89.6 (90.1 ± 32.9) IU/kg/week for rVIII-SingleChain, 112.9 (107.8 ± 39.4) IU/kg/week for rFVIIIFc, 100.1 (118.6 ± 61.0) IU/kg/week for PEG-rFVIII, 114.1 (120.0 ± 59.1) IU/kg/week for octocog alfa, 130.6 (116.6 ± 47.5) IU/kg/week for BAY 14-2222, and 105.8 (106.9 ± 44.3) IU/kg/week for BAY 81-8973 (Figure 3). The difference between factor consumption across the 6 treatment groups was also statistically significant for patients with severe disease (P = 0.014).

FIGURE 3.

Weekly Factor Consumption in Patients with Severe Disease Using Standard-Acting or Long-Acting FVIII Products

Discussion

This analysis evaluates the real-world effectiveness and consumption of 6 commonly prescribed hemophilia A products in the United States. In general, patients receiving long-acting products were observed to experience numerically reduced dosing frequency with similar bleeding rates, compared with those receiving standard-acting products.

Patients receiving long-acting products were dosed less frequently than those receiving standard-acting products, with > 60% of patients receiving long-acting products dosed 2 times weekly or less. A significant difference in mean weekly FVIII consumption across the 6 treatment groups was shown in the ANCOVA model, which adjusted for potential differences in patient characteristics. Mean ABRs were not statistically different across the 6 products evaluated, which may be because of a number of factors, including sample size and the magnitude of difference and variability in the ABRs.

Long-acting products that extend FVIII half-life had reduced dosing frequency compared with standard-acting products while maintaining bleed control; hence, long-acting products have the potential to improve quality of life for patients with hemophilia A.6 Reduced patient burden because of reduced frequency of injections may increase treatment adherence, which can increase treatment effectiveness.9,20 Furthermore, since lower consumption was observed with long-acting products, their use can potentially reduce the overall cost of treatment, making them more attractive to payers than standard-acting products.

These data, evaluating the real-world use of commonly prescribed FVIII products in the United States, support data observed with the use of products in clinical studies and other real-world studies. For example, real-world studies in the United States and Italy have shown that the long-acting products rFVIIIFc and PEG-rFVIII, respectively, had reduced dosing frequency and lower consumption with comparable bleeding rates compared with standard-acting products.21-23 Data in this U.S. study are comparable to results of a real-world study in Germany comparing the 5 FVIII products, rVIII-SingleChain, rFVIIIFc, octocog alfa, BAY 81-8973, and moroctocog alfa, in which rVIII-SingleChain was shown to provide effective bleed protection with the lowest consumption among the products evaluated.24

Of the 6 products evaluated, mean weekly factor consumption was lowest for rVIII-SingleChain, and bleeding rates were comparable across all products. Bleeding rates and consumption data for rVIII-SingleChain observed in this real-world study corroborate those observed for rVIII-SingleChain in its pivotal phase 3 clinical study.16 Comparison of long-acting rFVIII products in the U.S. retrospective studies demonstrated that rVIII-SingleChain is observed with reduced mean factor consumption compared with rFVIIIFc and PEG-rFVIII, while showing comparable bleed rates.19 This is also the case for rVIII-SingleChain compared with the standard-acting products octocog alfa, BAY 14-2222, and BAY 81-8973. Among the 6 products evaluated, the lowest weekly factor consumption was observed for rVIII-SingleChain for all selected patients including those with severe hemophilia A. Based on the weekly consumption for all patients (Figure 2), the annual factor consumption (IU/kg/year) were calculated to be: 4750.2 (rVIII-SingleChain), 5402.0 (rFVIIIFc), and 5787.9 (PEG-rFVIII) for the long-acting products, and 6126.8 (octocog alfa), 5349.9 (BAY 14-2222) and 5256.0 (BAY 81-8973) for the standard-acting products. These results may have important economic implications to be considered when deciding the most appropriate FVIII replacement therapy for patients with hemophilia A.

Limitations

Limitations of this analysis include a relatively small sample size and short assessment period (about a year), with limited information on bleed type, location, duration, and severity. These data may not be representative of the entire patient population in the United States, since the potential for selection bias may exist, and we were not able to assess the effect of potentially differing patient management practices at the centers contributing data.

Potential differences in additional patient demographic, socioeconomic, and clinical characteristics (e.g., history of inhibitors, number of target joints, patient’s activity profile) may also affect the generalizability of these data to the overall population. However, many such variables may not be recorded in patient charts or may have inconsistency or data quality issues; therefore, including them in the analysis may not be feasible.

Measuring compliance is difficult, and consumption calculations are based on physician prescriptions, which may not be a true representation of factor consumption; however, given that the population is likely to include both overusers and underusers, we believe it is reasonable to assume that these data are representative of real-world FVIII consumption.

As the most recently approved product in the United States among the 6 products evaluated, it is noted that the mean duration of observation was shorter with rVIII-SingleChain than the other products (43 vs. 52 weeks, respectively); therefore, the proportion of patients with 0 bleeds may be lower than reported, and the proportion of patients with more frequent dosing may be higher had the duration of observation been the same.

Conclusions

This study evaluated real-world data on bleeding rates and usage of standard- and long-acting products commonly prescribed in the United States to treat patients with hemophilia A. The results of this study suggest that long-acting products may provide an advantage over standard-acting products, given the observation that long-acting products are associated with a reduction in dosing frequency while maintaining effectiveness. Results of this real-world study for rVIII-SingleChain support data from its clinical studies. rVIII-SingleChain was observed to be similar at reducing dosing frequency, comparable with the other 2 long-acting products, and had the lowest observed mean weekly consumption compared with the standard-acting products octocog alfa, BAY 14-2222, and BAY 81-8973, and the long-acting rFVIIIFc and PEG-rFVIII.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Medical writing support was provided by Amrita Shergill of Meridian HealthComms (Plumley, UK) and funded by CSL Behring.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mannucci PM, Tuddenham EG. The hemophilias--from royal genes to gene therapy. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(23):1773-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Srivastava A, Brewer AK, Mauser-Bunschoten EP, et al. Guidelines for the management of hemophilia. Haemophilia. 2013;19(1):e1-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peyvandi F, Menegatti M. Treatment of rare factor deficiencies in 2016. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2016;2016(1):663-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oldenburg J. Optimal treatment strategies for hemophilia: achievements and limitations of current prophylactic regimens. Blood. 2015;125(13): 2038-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Vulpen LFD, Holstein K, Martinoli C. Joint disease in haemophilia: pathophysiology, pain and imaging. Haemophilia. 2018;24 Suppl 6:44-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lambert T, Benson G, Dolan G, et al. Practical aspects of extended half-life products for the treatment of haemophilia. Ther Adv Hematol. 2018;9(9):295-308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Makris M. Prophylaxis in haemophilia should be life-long. Blood Transfus. 2012;10(2):165-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gringeri A, Ewenstein B, Reininger A. The burden of bleeding in haemophilia: is one bleed too many? Haemophilia. 2014;20(4):459-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thornburg CD, Duncan NA. Treatment adherence in hemophilia. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:1677-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Konkle BA, Stasyshyn O, Chowdary P, et al. Pegylated, full-length, recombinant factor VIII for prophylactic and on-demand treatment of severe hemophilia A. Blood. 2015;126(9):1078-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahlangu J, Powell JS, Ragni MV, et al. Phase 3 study of recombinant factor VIII Fc fusion protein in severe hemophilia A. Blood. 2014;123(3): 317-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidbauer S, Witzel R, Robbel L, et al. Physicochemical characterisation of rVIII-SingleChain, a novel recombinant single-chain factor VIII. Thromb Res. 2015;136(2):388-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lieuw K. Many factor VIII products available in the treatment of hemophilia A: an embarrassment of riches? J Blood Med. 2017;8:67-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Advate (antihemophilic factor [recombinant]) lyophilized powder for reconstitution for intravenous injection. Baxalta U.S. December 2018. Available at: https://www.shirecontent.com/PI/PDFs/ADVATE_USA_ENG.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwartz CE, Powell VE, Su J, Zhang J, Eldar-Lissai A. The impact of extended half-life versus conventional factor product on hemophilia caregiver burden. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(5):1335-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahlangu J, Kuliczkowski K, Karim FA, et al. Efficacy and safety of rVIII-SingleChain: results of a phase 1/3 multicenter clinical trial in severe hemophilia A. Blood. 2016;128(5):630-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poon MC, Lee A. Individualized prophylaxis for optimizing hemophilia care: can we apply this to both developed and developing nations? Thromb J. 2016;14(Suppl 1):32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rea C, Dunkerley A, Sorensen B, Rangarajan S. Pharmacokinetics, coagulation factor consumption and clinical efficacy in patients being switched from full-length FVIII treatment to B-domain-deleted r-FVIII and back to full-length FVIII. Haemophilia. 2009;15(6):1237-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simpson ML, Desai V, Maro GS, Yan S. Comparing factor use and bleed rates in U.S. hemophilia A patients receiving prophylaxis with 3 different long-acting recombinant factor VIII products. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2020;26(4):504-12. Available at: https://www.jmcp.org/doi/10.18553/jmcp.2020.19318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iorio A, Krishnan S, Huynh L, Karner P, Duh MS, Yermakov S. Indirect comparison of the efficacy of recombinant factor VIII Fc fusion protein and other factor VIII products for prophylaxis modeling the effect of compliance. Value Health. 2014;17(3):A230. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tagliaferri A, Matichecchia A, Rivolta GF, et al. Optimising prophylaxis outcomes and costs in haemophilia patients switching to recombinant FVIII-Fc: a single-centre real-world experience. Blood Transfus. 2019:1-11 [Epub ahead of print]. Available at: http://www.bloodtransfusion.it/articolosing.aspx?id=001036. Accessed July 15, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dunn AL, Ahuja SP, Mullins ES. Real-world experience with use of antihemophilic factor (recombinant), PEGylated for prophylaxis in severe haemophilia A. Haemophilia. 2018;24(3):e84-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khair K, Mazzucconi MG, Parra R, et al. Pattern of bleeding in a large prospective cohort of haemophilia A patients: a three-year follow-up of the AHEAD (Advate in HaEmophilia A outcome Database) study. Haemophilia. 2018;24(1):85-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olivieri M, Sommerer P, Maro G, Yan S. Assessing prophylactic use and clinical outcomes in hemophilia A patients treated with rVIII-SingleChain and other common rFVIII products in Germany. Eur J Haematol. 2019;104(4):310-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]